Abstract

Homelessness prevention efforts face an overarching challenge: how to target limited resources far enough downstream to capture those at greatest risk of homelessness, but far enough upstream to stabilize households before they experience a cascade of negative outcomes. How did the COVID-19 emergency rental assistance programs launched in hundreds of localities across the United States respond to this challenge? This paper draws on two waves of a national survey of emergency rental assistance program administrators, as well as in-depth interviews with 15 administrators, to answer this question. Results show that although the vast majority of program administrators considered homelessness prevention to be a key program goal, their programs tended to target rental assistance far upstream of tenants at immediate risk.

One of the central challenges associated with homelessness prevention is the difficulty of targeting resources to those who are most at risk of experiencing homelessness. Ideally, housing programs would provide support to prevent at-risk households from ever experiencing the trauma of homelessness. Yet housing officials have no way of knowing for sure which households, absent assistance, would become homeless and which would not. Indeed, research suggests that most families served by homelessness prevention programs would not have become homeless in the next few years in the absence of assistance (Rolston et al., Citation2013). This finding does not negate the value of prevention programs for stabilizing families, but it does raise the question of what counts as homelessness prevention, and how local officials can potentially target those most at risk. Downstream interventions—those that take place in housing court or, at the most extreme, once a household is already experiencing homelessness—allow for more precise targeting but may come too late to prevent the negative consequences of housing instability and force households into dire situations in order to access help.

With unprecedented levels of funding from Congress, hundreds of state and local governments across the United States launched emergency rental assistance programs in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. According to our national survey of administrators of over 200 emergency rental assistance programs launched in 2020, 86% of those programs listed preventing homelessness as a goal. These programs thus offer a unique opportunity to study the challenges of targeting short-term rental assistance to prevent homelessness, although of course the patterns we find may not necessarily generalize beyond the particular COVID-19 context.

This paper uses results from the initial 2020 survey, as well as from a second, smaller survey of Treasury Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) programs newly launched in 2021, to describe how and the extent to which program goals, outreach, eligibility criteria, documentation requirements, and subsidy structure align with homelessness prevention. In addition, we draw on in-depth interviews with administrators of 15 programs, representing a broad cross section of rent relief programs, to add nuance to the survey findings. Findings are organized according to five key research questions: first, do rental assistance programs aim to prevent homelessness, and if so, does that aim shape program design? Second, regardless of the stated goal, do rental assistance programs focus more on upstream or downstream outreach? Third, to what extent do programs define and target assistance to vulnerable households through eligibility criteria? Fourth, do programs include documentation requirements that may discourage the most vulnerable from applying? And finally, are subsidy amounts and structure likely to limit or expand access to those most vulnerable to homelessness?

In brief, we find that the vast majority of program administrators considered homelessness prevention a key goal, but their programs tended to target assistance far upstream of the households at most immediate risk. For example, many programs deployed only or primarily upstream outreach strategies such as traditional media campaigns. Survey and interview results also suggest eligibility requirements among 2020 programs were not calibrated to target those at immediate risk of homelessness. In fact, some programs may have excluded populations at high risk by imposing eligibility requirements that were stricter than federal guidelines mandated. Furthermore, the decision by nearly all programs to provide payments directly to landlords likely led to the exclusion of households in tenuous housing situations.

Although these are limited, we identified some links between program design and homelessness prevention. For example, some survey respondents conducted downstream outreach in housing court, and interviews suggest that administrators saw a close link between evictions and the risk of homelessness. Additionally, a majority of programs took advantage of increasingly flexible federal guidance to reduce documentation requirements in ways that facilitated increased participation by the most vulnerable.

More fundamentally, results suggest many administrators viewed housing instability as a process, or a downward cascade. By helping people become current on their rent, administrators were reducing the likelihood that tenants would have to move, which in turn would reduce the likelihood that they would have to double up, and ultimately reduce the chance that they would experience homelessness. In this way, emergency rental assistance programs likely lead to small reductions in risk for a large number of households, as opposed to more targeted approaches that greatly reduce risk for a smaller number of households on the precipice of homelessness.

What Is Homelessness Prevention?

The trauma of homelessness, together with the extremely high cost of emergency services for people experiencing homelessness, underscore the potential benefits of intervening upstream to prevent people from falling into literal homelessness, or the condition of lacking a “fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence” (HEARTH Act, Citation2009). Fowler et al. (Citation2019) divide prevention services into three categories, in part distinguished by how far upstream services are provided. The first category is “universal assistance,” which would include universal housing vouchers or right-to-housing legislation, and arguably structural efforts to reduce poverty and remove regulatory barriers to constructing new housing. The second is “selective prevention,” which targets subgroups deemed to be vulnerable to homelessness, such as veterans and youth aging out of foster care. The third category is “indicated prevention,” which aims to serve those at imminent risk of losing their homes, such as those facing evictions.Footnote1 This last category covers most of what the field considers to be homelessness prevention policies and programs, although to be clear, most people experiencing eviction do not become homeless. Of course, there is an interaction among these forms of prevention. Societies adopting universal assistance would have less need for more targeted prevention efforts.

Our focus in this paper is on emergency rental assistance, which would fall into “indicated prevention” services. But the nature of outreach shapes how directly programs target those who would otherwise become homeless. Upstream outreach methods, such as advertising in traditional media, are likely to reach a broad audience and therefore may spread awareness of available rental assistance to at-risk tenants early enough to stave off further destabilizing experiences. But these methods also reach many tenants who may qualify for assistance but would not have become homeless in its absence. Outreach that more narrowly targets vulnerable households, for instance via community-based organizations already serving high-risk communities, could increase the chance of reaching those truly on the verge of homelessness. Furthest downstream on the prevention scale is housing court-based outreach, which is very likely to reach the most vulnerable households (tenants about to lose their homes), but which also comes too late for the many who choose to self-evict rather than appear in court.

The existing literature shows that homelessness prevention interventions can be effective. New York City began to roll out its Homebase prevention program in 2004. Goodman et al. (Citation2016) used the variation in timing of launch across neighborhoods to study impacts. They found that Homebase significantly reduced entries in shelter (although it had no effect on exits). Rolston et al. (Citation2013) report the results of a randomized control trial in which some individual applicants received services and others did not. They found that families assigned to receive services were significantly less likely to enter shelters than control group families. Similarly, Evans et al. (Citation2016) exploit the random availability of funds available through the Homelessness Prevention Call Center in Chicago, Illinois, and find that access to financial assistance reduced the number of days spent in shelter over a 6-month period by 2.6 days, down from a baseline of 3.1 days.

A key challenge for such assistance is correctly identifying those most at risk. This is partly because people at risk of homelessness are likely to hold private information that service agencies cannot obtain, but would be useful in predicting whether they will become homeless (O’Flaherty et al., Citation2018). Known risk factors for homelessness include veteran status, severe mental illness, chronic substance abuse, HIV positivity, and being a survivor of domestic violence. African Americans, Native Americans, and Pacific Islanders also have significantly higher risk ratios than other groups (Evans et al., Citation2021). By far the most important predictors, however, are previous homelessness and current housing status—especially doubling up, and residing in the poorest quality housing (Haupert, Citation2021; O’Flaherty, Citation2010).

Risk factors notwithstanding, individual episodes of homelessness remain extremely difficult to predict, and even evictions themselves do not always lead to homelessness. O’Flaherty (Citation2010) emphasizes that homeless spells should be seen as bad luck, or like fires that cannot be predicted. Most people who are evicted do not experience homelessness (Collinson et al., Citation2022). And research shows that prevention services often go to people who would not have become homeless absent intervention, at least not in the short or medium term (Evans et al., Citation2016; O’Flaherty, Citation2019; Rolston et al., Citation2013). Evans et al. (Citation2016) find that in Chicago, only 2% of families who request and are denied financial assistance to prevent homelessness actually enter a shelter within 6 months; most of these families had been served an eviction notice. In New York City, where shelter use is far more common than in Chicago, given the right to shelter, Rolston et al. (Citation2013) report that 13% of control group families who request but do not receive Homebase services enter shelter within 3 years. Still, Collinson et al. (Citation2022) show that evictions increase the risk of homelessness. Moreover, evictions may lead to more tenuous housing situations, like informal tenancies or doubling up. We know that a much larger share of families enter homelessness after living in someone else’s house than after living in their own rental or ownership housing (Gubits et al., Citation2015; Shinn and Khadduri, Citation2020). Thus, eviction may lead to homelessness over a longer period of time.

Unfortunately, the more precisely programs target those at imminent risk, the later that assistance will reach people, in some cases after they have already experienced some trauma and costs, such as receiving an eviction notice that will mar their record and hinder their ability to find housing and potentially even employment. There is also a risk of moral hazard for property owners that negatively impacts tenants; if programs require that households receive an eviction notice to qualify for emergency rental assistance, then landlords will be incentivized to file for eviction as soon as problems arise.

These studies raise questions about the extent to which emergency rental assistance can be targeted effectively enough to prevent spells of imminent homelessness. The massive scale and breadth of assistance provided through COVID relief programs suggests that most people receiving assistance would likely not become homeless absent assistance. This is not to say that the rental assistance was valueless for addressing drivers of homelessness. It may have helped to reduce housing cost burdens, alleviate stress, reduce residential instability, prevent doubling up, and shore up the finances of many small landlords. And during a global pandemic, keeping people in their homes may slow the speed of transmission by keeping people from having to double up with friends and family (Emeruwa et al., Citation2020; Kuehn, Citation2020; Leifheit et al., Citation2021). Yet, as noted below, many programs stated an explicit aim to prevent homelessness, and this paper discusses what administrators meant by that goal and how they attempted to achieve it.

Policy Context

The sources of, and restrictions on, funds for COVID-19 emergency rental assistance play an important role in jurisdictions’ decisions about program design, and thus the potential of these programs to prevent homelessness. In 2020, many state and local governments opted to establish emergency rental assistance programs, relying heavily on various funds within the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to administer the programs. The optional nature of the funds for emergency rental assistance created an uneven patchwork of programs with varying requirements depending on the specific funding stream used. In December of 2020, Congress enacted the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 and provided $25 billion exclusively for emergency rental assistance for low-income households, thereby establishing the U.S. Department of the Treasury ERA Program. Congress provided an additional $21.55 billion for ERA programs in March of 2021. Unlike the previous patchwork of local and state emergency rental assistance programs, the Treasury ERA program provides more uniform coverage of low-income renters across the nation through states, local jurisdictions with populations over 200,000, U.S. territories, tribal governments and tribally designated housing entities, and the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands. Uniform guidance also undergirds the administration of the program across many communities. This section describes (a) the funding streams, and associated restrictions, within the CARES Act and (b) the Treasury ERA program.

The CARES Act, enacted in March 2020, provided three main funding streams that state and local governments could use for emergency housing programming during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Act included $150 billion for the Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF), administered by the U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury); $5 billion for the Community Development Block Grant CARES Act Program (CDBG-CV), administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD); and $4 billion for the Emergency Solution Grant CARES Act program (ESG-CV), also administered by HUD.

CRF ($150 billion): CRF could be employed for a broad range of uses related to the COVID-19 pandemic, including to mitigate COVID-19 effects for people experiencing homelessness or to provide economic support related to COVID-19. In supplemental guidance, Treasury clarified that the funds could be used to provide a “consumer grant program to prevent eviction and assist in preventing homelessness” (Coronavirus Relief Fund, Citation2021). The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 extended the deadline for using CRF funds from December 30, 2020, to December 30, 2021, but most programs nevertheless concluded coverage at the end of 2020.

CDBG-CV ($5 billion): CDBG-CV could be used to fund “activities to prevent, prepare for, and respond to the coronavirus” (Notice of Program Rules, Citation2020) and included several waivers to allow grantees to flexibly and expeditiously serve their communities. Although CDBG entitlement can traditionally be used to provide for rental or utility assistance for up to 3 months, HUD’s Office of Community and Planning issued a waiver in August 2020 to allow for up to 6 months of rental or utility assistance. CDBG-CV grantees have up to 3 years to spend at least 80% of their CDBG-CV funds and, if 80% is spent, an additional 3 years to spend the remainder, as articulated in their HUD-approved grant agreements. At least 70% of CDBG-CV must benefit households with incomes less than 80% of the area median income (AMI).

ESG-CV ($4 billion): ESG-CV could similarly be used to fund activities to “to prevent, prepare for, and respond to coronavirus, among individuals and families who are homeless or receiving homeless assistance.” ESG-CV could be used to pay for street outreach, rapid rehousing, homelessness prevention, shelter operations, and administration.

State and local governments were not required to use CARES Act funds toward emergency rental assistance. Yet as of April 2021, the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) had identified 391 emergency rental assistance programs primarily funded by CARES Act, accounting for at least $2.9 billion invested exclusively in emergency rental assistance and an additional $1.2 billion invested in housing assistance more broadly, including both emergency rental assistance and mortgage assistance.

The Treasury ERA Program includes a total of $46.55 billion specifically for emergency rental assistance for low-income households ($25 billion from the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 and $21.55 billion from the American Rescue Plan Act). Although ERA funds from the two laws have similar regulations and requirements, there are a few notable differences in eligibility criteria, maximum length of assistance, and other rules and regulations. Thus, this paper will use “ERA1” to refer to ERA funds provided through the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 and “ERA2” to refer to ERA funds provided through the American Rescue Plan Act.

ERA funds can be used to provide financial assistance for rent and utility arrears, future rent and utility costs, and other housing-related expenses, such as relocation assistance and hotel stays for households that have already been displaced. ERA funds can also be used to provide housing stability services, such as case management, legal services, and housing counseling. Eligible households can receive a maximum of 18 months of assistance using ERA1 and ERA2 combined.

Households are eligible for ERA funds if the household (a) is low-income,Footnote2 (b) can demonstrate a risk of experiencing homelessness or housing instability, and (c) qualified for unemployment benefits; or, specifically for ERA1, experienced reduction in household income, incurred significant costs, or experienced other financial hardship due, directly or indirectly, to the pandemic; or, specifically for ERA2, experienced a reduction in household income, incurred significant costs, or experienced other financial hardship during or due, directly or indirectly, to the pandemic.

Data and Methods

This paper relies on two sets of surveys with emergency rental assistance program administrators, the first conducted in the late summer and fall of 2020 with programs relying primarily on CARES Act funding, and the second in April 2021, with programs using Treasury ERA1 funds. It also incorporates interviews with the administrators of 15 local (i.e., nonstate) programs representing a broad cross section of jurisdictions, from rural to urban and small to large, that were conducted in January 2021.

Survey Data

Our survey samples were selected using the NLIHC’s COVID-19 Rental Assistance Database, a comprehensive database of emergency rental assistance programs created or expanded in response to COVID-19. The 2020 survey has a substantially larger sample size than the 2021 survey (N = 220 versus N = 64).Footnote3 Nevertheless, both survey samples included a broad cross-section of jurisdiction types that are well distributed across the country. The Appendix provides more detailed information about survey administration.

The 2020 survey sample of 220 programs includes primarily programs serving a single city (41%) or county (33%). Regional programs represented 14% of responses whereas statewide programs represented another 13% of responses. NLIHC was tracking 418 emergency rental assistance programs as of early October 2020; over half (55%) were city programs, whereas 29% were administered by counties, 15% by states, and 0.4% by regions. The 2020 survey sample was slightly skewed toward regional programs that were local administrators of statewide programs. NLIHC generally tracked programs at the level of the largest unit of government, even if they primarily relied on local administrators to carry the programs out.

Of the 2021 survey respondents, about half (53%) were local programs serving a city, county, region, or territory. Just under a third (28%) were statewide programs and 19% came from local administrators for state-level programs. The survey sample is somewhat skewed toward statewide programs. Among the 340 programs captured in the NLIHC Database by mid-May, close to half (48%) were county programs, whereas 23% were administered by tribal governments, 15% by cities, and only 14% by states.

Interviews

In January 2021 we conducted interviews with one or more administrators from 15 programs that had participated in the 2020 survey. Our goal in selecting these case study programs was to capture a broad spectrum of program sizes, geographical locations, and characteristics. We selected two programs serving rural jurisdictions, four programs serving either a small city or a medium-sized county in a metropolitan area (ranging in population from 80,000 to 100,000); three programs serving large counties (ranging from 600,000 to 2.2 million residents); and six programs serving large cities (ranging from 190,000 to 2.7 million residents). One final selection criterion was to have both new programs (10) and programs that modified or expanded a program that predated the pandemic (five).

We conducted hour-long interviews with each case study program’s administrators. In some cases, we supplemented these with 30-minute follow-up interviews to ensure completion of the full interview protocol. The protocol included questions related to participant eligibility, documentation requirements, outreach, intake, monitoring, and program infrastructure and capacity. We also asked administrators to share lessons learned and asked for advice they might offer to other programs.

Key Findings

Both our surveys and interviews captured elements of emergency rental assistance program design and administration that shed light on the extent to which program goals, features, and implementation align with homelessness prevention. In this section we provide findings related to our five research questions: do rental assistance programs consider homelessness prevention a goal, and if so, does that intention shape program design?; do rental assistance programs focus more on upstream or downstream outreach?; do programs define and target assistance to vulnerable households?; do programs include documentation requirements that may discourage those most vulnerable to homelessness from applying?; and, are subsidy amounts and structure designed to serve the most vulnerable?

Program Goals

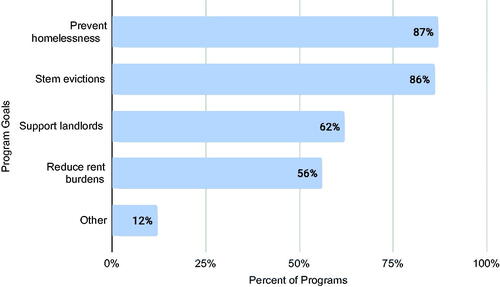

Both the 2020 and 2021 surveys asked respondents to identify the goals of their emergency rental assistance programs, either by selecting from a list of possible goals or by writing in a response. The vast majority (86%, N = 164) of respondents to the 2020 survey selected “prevent homelessness” as a goal (see ).

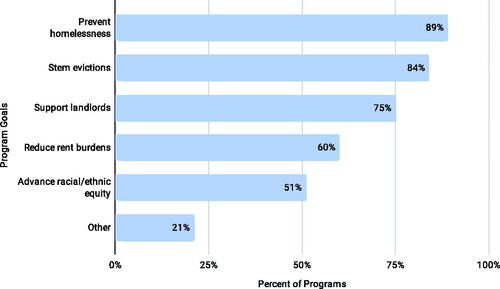

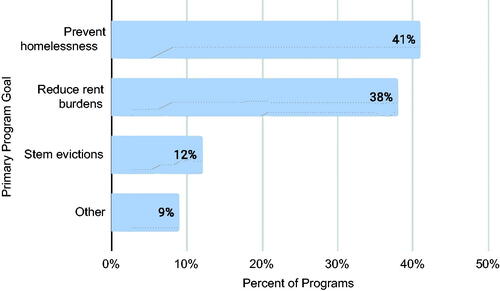

A similar majority (89%, N = 63) of respondents selected homelessness prevention as one of their program’s goals in 2021 (see ). In a separate question, the 2021 survey also asked respondents to identify the program’s primary goal. The most commonly selected goal was homelessness prevention, with 41% of administrators listing it as their program’s primary goal (see ).

In both surveys, preventing homelessness and stemming evictions were consistently the two most commonly selected goals. Many program administrators may have viewed these goals as inseparable; of the respondents who selected either goal in 2020, 80% selected both; in 2021, the share rose to 82%. Although evictions rarely result immediately in homelessness, research indicates they heighten the risk of homelessness (Collinson et al., Citation2022). Surveys in cities across the country have found that a significant share of individuals experiencing homelessness cite eviction as a primary cause of their homelessness (National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, Citation2018).

Identifying homelessness prevention as a program goal, or even as the program's primary goal, was not a strong or consistent predictor of program characteristics, however. For instance, programs that reported preventing homelessness as their primary goal in the 2021 survey were no more likely than other programs to offer direct-to-tenant assistance (t(55) = −0.15, p = .88) or to allow self-attestation of income (t(49) = −0.06, p = .95) or tenancy (t(49) = 1.53, p = .13). Neither was there any statistically significant difference in the maximum months of subsidy offered (t(49) = 0.06, p = .95) or in documentation requirements such as social security numbers for tenants or business licenses for landlords. Indeed, 2021 programs with the primary goal of preventing homelessness were slightly less likely to report conducting targeted outreach in eviction court (t(50) = 2.16, p = .04). In short, the goal of homelessness prevention did not appear to set programs apart in terms of subsidy flexibility, documentation, or outreach.

Interview responses provided further evidence of the importance of homelessness prevention—especially through the prevention of evictions as a direct or indirect cause of homelessness—as a key program goal. One administrator noted that the driving force behind developing their program was “the thought that a lot of our residents were going to face eviction after the moratorium if somebody didn’t get involved to try to help.” Another interviewee highlighted how the goal to prevent homelessness and evictions shaped their distribution of funds, noting, “whenever we made a pledge or provided assistance, it was to prevent eviction or homelessness, or prevent a cut-off in utility services.”

Some interviewees who identified homelessness prevention as a program goal contrasted ERA funding with preexisting homelessness-related programs in their jurisdictions that operated further downstream. For example, one administrator compared their rental assistance program with a preexisting homelessness prevention program in their jurisdiction that they described as “a very, very prescribed program. It is heavy case management. It is true housing stability, where some form of rental assistance is available to tenants if that is the one thing that they need to stabilize, but that is after case management is administered.” Another respondent explained that their rental assistance program was not designed to address the needs of those who were already homeless. These needs were already addressed by a homelessness-related nonprofit that provided “a lot of assistance,” and the individuals the nonprofit was assisting “weren’t housed folks before the pandemic started” so they were, by extension, not eligible for rental assistance. This response does not necessarily indicate the program was unconcerned with homelessness. Rather, administrators appeared to view these funds as a more upstream approach to addressing homelessness by targeting funds to households that were currently housed, not those already unhoused.

Outreach: Upstream Versus Downstream

Programs varied in how—and where—they conducted outreach. A large majority of respondents to both the 2020 and 2021 surveys used platforms such as social media (88% and 94%, respectively), radio (32% and 73%), and newspaper advertisements (60% and 73%) to engage people in the program. Many (over 70% of both samples) also reported partnering with nonprofit organizations to conduct outreach, which may suggest more targeted efforts. The 2021 survey further explored targeted outreach via a series of questions about whether and how programs were intended to reach “underserved groups” such as high-poverty neighborhoods, racial and ethnic minorities, or immigrant communities. Over 90% (N = 52) of respondents indicated that their programs aimed to reach underserved groups; of these, 74% (N = 46) said they contracted with trusted community organizations to conduct outreach. Somewhat smaller shares used targeted media such as Spanish language newspapers (67%), hosted in-person events in underserved communities (35%), or conducted door-knocking campaigns (20%). These forms of outreach reflect the reality that the risk of housing insecurity and homelessness, as well as access to housing assistance, varies by race and ethnicity (Henry et al., Citation2018; Reina & Aiken, Citation2021). Yet these outreach methods target households well upstream of public systems like homeless shelters and courts, ideally averting households’ need to engage with those systems.

Just over a quarter (27%, N = 163) of 2020 survey respondents indicated that they did or would use outreach in housing court as an outreach method, reflecting more downstream targeting. Interestingly, 2021 survey respondents embraced court-based outreach at a much higher rate of 63% (N = 52). Survey respondents used write-in responses to describe sending program information to all landlords and tenants with cases on the eviction court docket and enrolling defendants in rental assistance as part of in-court mediation. This may reflect a larger shift toward integrating rental assistance programs with eviction diversion and homelessness prevention efforts, as well as a need to respond to reopening courts and the potential expiration of temporary tenant protections and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) eviction moratorium.

Interview responses provide a more detailed view of programs’ strategies for reaching those most at risk of homelessness. Of these strategies, the most widely cited was partnerships with local nonprofits and preexisting public agencies with deep community ties. One respondent noted, “We contracted with eight community-based organizations, and they…helped us reach out to the community and hardest to reach populations,” adding that with additional preparation time, “we would probably expand the outreach even more. Just to make sure that all underserved communities really were aware of the program and had time to access the application system.” Programs pointed to a desire to overcome outreach barriers and underdeveloped relationships with immigrant communities as reasons for partnering with nonprofits. One respondent described, for example, a reliance on a nonprofit partner “to take referrals from…our Muslim center, our Salama center, our immigrant and refugee center, just making sure that we were reaching those populations that would not have heard about it on our radio stations, would not have naturally reached out.” Another administrator described leveraging other community-oriented government departments for outreach purposes, explaining, “We also trained our coordinated entry staff and our homeless system to know about the program and to point people in that direction.” This respondent also noted that rather than conducting outreach at homeless shelters, they would leverage their local social service providers to “try to catch people before they got there.”

Several administrators whose jurisdictions operated rental relief programs before the onset of the pandemic noted that their normal outreach sites were not accessible due to the need to maintain social distancing precautions. For example, one respondent noted, “We had some agencies that went to food banks and signed people up at food banks. But it was challenging given COVID, to be honest, to do outreach in the ways that we traditionally would do outreach.” This respondent went on to explain, “In the past, we could have people coming into the facility who are trying to utilize the pantry and maybe mentioned during their intake that they were having trouble with paying their rent and could do a quick handoff to one of our case managers to talk to them about our rental program. And that pretty much was eliminated entirely when we shifted to a drive-up model for the pantry.” By contrast, one program did explicitly conduct outreach at homeless shelters. As this program’s administrator explained, “We did target the organization that runs the homeless shelter, and they were very helpful in getting quite a few applicants to sign up, and they were also very helpful in getting their applicants to complete the process.”

Housing courts also provided opportunities for outreach, with judges sometimes proactively coordinating with rental assistance programs. One administrator saw housing court as an opportunity for triage when their program was faced with an early wave of applicants, noting that “a lot of what we did early on with that timing is we reached out through the court. We reached out through attorneys.” Another respondent described their relationship to their state’s supreme court with enthusiasm, relaying how

the judicial system reached out to us and said, “We would like to partner with you to do a court diversion program.” And so, the chief justice…issued a supreme court order whereby literally I as the director…could screen the tenant and see if they qualified for assistance and if they did, then, we could help get their rent paid.

Other programs employed nonprofit organizations to manage housing court flows. For example, an administrator explained that the circuit court judge in charge of eviction proceedings “would give a list of evictions that were upcoming on the docket” to the program’s nonprofit partner, and the partner “would reach out to those tenants and landlords that were listed on the docket and screen them for COVID-related hardships.” Similarly, another respondent described the judge–program outreach partnership as “critical,” explaining that “judges that oversaw those proceedings reached out to us…. So, that's like, right where the rubber meets the road.”

One program used creative language in their award letters to owners to leverage a local eviction moratorium while still distributing funds further upstream than to housing court attendees. As the administrator explained, although the moratorium was in place, they

added a sentence at the end of the award letter that said, “We believe that the tenant qualifies for the eviction moratorium based on the fact that they participate in this program. So, we don’t think that you can evict them.” […] So that if they did try to evict the tenant could take that to the magistrate and say, “I don’t think I should be here.”

Eligibility Criteria

Beyond targeting their outreach, some emergency rental assistance programs set eligibility criteria narrower than those demanded by federal funding stipulations or developed systems to prioritize certain applicants for assistance. However, narrower criteria do not necessarily enhance a program’s ability to prevent homelessness. Among those surveyed in 2020, for example, 19% of programs required that a tenant be a legal U.S. resident to be eligible for assistance (N = 134) and 22% required tenants to have been current on rent prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. These criteria, especially the requirement for no pre-COVID arrears, may have actually excluded households most vulnerable to homelessness.

Survey results suggest that by 2021, many emergency rental assistance programs had relaxed their eligibility criteria. Very few programs required legal residency (11%, N = 54) or excluded tenants behind on rent prior to the pandemic (4%). Only 29% of programs restricted eligibility in any way beyond the criteria set by federal ERA funding legislation. This cannot be attributed to the change in survey sample. A sizable majority (70%) of 2021 program administrators surveyed whose programs had undergone multiple iterations since the onset of COVID-19 reported having adjusted their criteria since the previous iteration.

Treasury guidance for 2021 ERA programs also stipulated that eligible households “demonstrate a risk of experiencing homelessness or housing instability.” As a result, nearly all programs surveyed in 2021 (93%, N = 54) included “risk of homelessness or housing instability” as an eligibility criterion, although what they accepted as proof of this risk varied. Research shows that, among households applying for prevention services, shelter history is a strong predictor of reentry (Greer et al., Citation2016; Shinn et al., Citation2013). Yet only about a quarter (26%, N = 50) of ERA programs accepted previous experiences of homelessness as proof of a household’s risk of homelessness or housing instability. Past due rent or an eviction notice were much more popular forms of proof (accepted by 96% and 88% of programs, respectively), likely due to their explicit inclusion as possible indicators of homelessness or housing instability in the statute. About a third (34%) accepted severe housing cost burden as proof of risk.

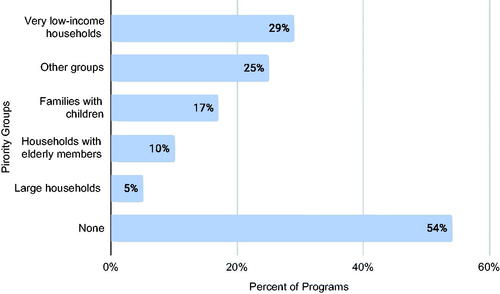

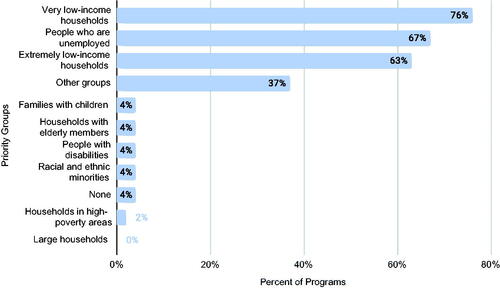

Both 2020 and 2021 survey respondents were asked whether their program prioritized specific groups for receipt of rental assistance. One third (29%, N = 106) of 2020 survey respondents prioritized very low-income tenants for assistance (see ), whereas over three quarters (76%, N = 51) of 2021 survey respondents did. The shift toward prioritizing very low-income households is not surprising; it was required by the statute allocating ERA1 funds. Prioritization of subgroups at immediate risk of homelessness remained rare. Only a handful of 2021 respondents specifically prioritized households threatened with eviction, those currently experiencing homelessness or who had experienced homelessness in the past, or households with large rent arrears (see ). Prioritization occurred primarily by moving priority households to the front of the line for assistance (47%, N = 49) or weighting them more heavily in a lottery (27%). The prioritization method itself has important implications for homelessness prevention. Conducting a lottery rather than processing applications on a first-come, first-served basis can reduce the disadvantages to those with limited technology access and language barriers (Ellen et al., Citation2021).

Interview responses reflected that many 2020 programs—which were in operation before the 2021 Treasury guidance stipulating that participating households must be at risk of homelessness or housing instability—adopted wider targeting to avoid the risk of excluding any households in need. One administrator expressed this mindset in noting, “during the pandemic, we're just really trying to make things as simple as possible […] just be as understanding as possible that everybody is kind of in this situation, it's not targeting one group.” This respondent went on to elaborate that they viewed lower-wage workers as more protected than others in some ways, explaining,

it's interesting that a lot of the lower paid jobs are also the jobs that have been protected such as, like the maintenance stuff, the grocery work, the kind of the lower tier paying jobs have actually been protected in this whole situation…So, I think just in terms of our eligibility, we've just really tried to not add too much.

Another administrator described how their program maintained loose eligibility requirements throughout its evolution. Initially, this program utilized local funding “that gave us really no guidance as to how we were going to set it up or what client eligibility would be. It was almost no strings attached from private donors.” The administrator continued, “We didn't want it to be challenging because we were in a pandemic, people were hurting.” After the program began administering CARES Act funds, the administrator explained that they sought to maintain broad eligibility thresholds, noting, “income eligibility guidelines were still loose. But they did have to prove…that they lost their income and lost their wages or applied for unemployment.”

Other administrators, however, saw narrower eligibility requirements as a means to target the most vulnerable. As one respondent explained, “I think the low-income umbrella sort of helps with the underserved or most vulnerable population. And then, I think the program allowed you to go to 80% AMI and we served 60% to make sure that the hardest hit people were really focused on.” Similarly, another interviewee noted, “when we first launched the program, we wanted to make sure that the priority was for people who were very low income— that being 60% or below of area median income.”

Application and Documentation Requirements

Even if a rental assistance program is intended to prevent homelessness, and effectively targets the most vulnerable households through outreach and eligibility criteria, requirements to submit formal documents may still be a barrier for vulnerable households. Households with volatile or cash earnings may be unable to share a pay stub proving their current income, much less their income a year prior. Similarly, proof of tenancy can be difficult to provide for those living in informal housing situations, and particularly for those already experiencing housing instability (Aiken et al., Citation2021). Research suggests that as households move residences and become increasingly at risk of homelessness, heads of households are less likely to be primary leaseholders (Smith et al., Citation2005). Rental assistance programs are permitted to mitigate these barriers by allowing self-attestation (i.e., a signed statement in lieu of documentary evidence).

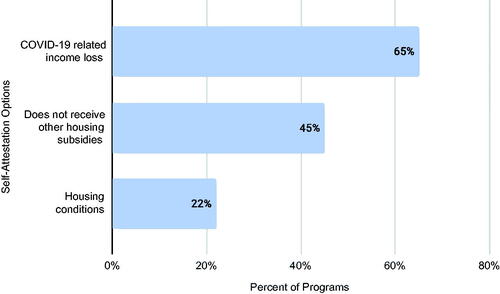

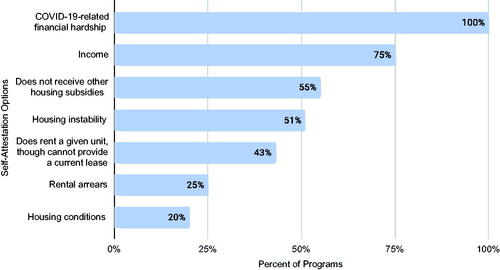

The majority of 2020 survey respondents (65%, N = 129) allowed applicants to self-attest COVID-19-related income losses (see ). By 2021, all respondents (N = 51) allowed for self-attestation of COVID-19 income losses or hardships. Two thirds also allowed for self-attestation of current income, although possibly only in cases of zero income (see ). But only a minority of programs (43%) allowed for self-attestation of tenancy in the absence of a current lease. This means that the majority of programs effectively excluded households that double up or have informal tenancies, which are known to be at greater risk of homelessness.

The evolution in rental assistance programs’ documentation flexibility is no doubt related to changes in federal guidance. For instance, initial guidance issued by the Treasury Department for ERA programs on January 19, 2021 instructed program administrators to verify household income. Subsequent guidance on February 22, 2021 rescinded this and encouraged self-attestation of income, housing instability, and COVID-19-related hardships provided that certain safeguards are met.

Interviewees consistently expressed a belief that reducing documentation requirements was an important strategy for ensuring the most vulnerable applicants were served. According to one interviewee,

for these programs that need to respond quickly to the vulnerable populations, you need to make sure that once you’re asking for it, it's actually really necessary and required…because sometimes it feels like we're asking for things that we really don’t need.

This respondent elaborated,

the biggest factor is getting the tenants…to complete all the documentation requirements, which really don’t seem that daunting, but when – in aggregate, when you combine everything, and ask them to provide it all, depending on … where they are in life, sometimes that’s just difficult.

Similarly, another administrator advised that other programs “don't convert their program to an overly administrative burden for the families. […] this is an emergency state and under COVID, they're not going to have access to gain documents that you might require for a traditional rental assistance program.”

Administrators also described the specific ways in which they reduced documentation requirements for applicants, sometimes with homelessness prevention explicitly in mind. For example, one respondent noted,

We made sure that they [the Mayor’s Office] were not going to require a social security number to be produced because we had a significant amount of individuals that could not produce that, and that we did not need on the streets.

Counter to the majority of programs, some respondents explained that they had prioritized administrative efficiency over flexibility. In these instances, administrators expressed struggling with the possibility that more stringent documentation requirements might prevent the most vulnerable households from accessing funds. For example, one administrator explained that the program’s initial use of a low-barrier screening application resulted in high nonresponse rates from applicants when program staff tried to follow up. In response, the program pivoted to requiring more documentation up front. On one hand, this strategy “was very successful in the sense [that] we were able to churn through applications and process them much, much faster.” However, the administrator also noted that the up-front documentation requirements yielded just a fraction of the previous system’s applicants, further explaining, “that gave us pause about who are we missing and who has dropped off because we've sort of heightened the requirements to enter the system.”

Several programs noted that online applications were barriers in themselves and offered flexibility to applicants by allowing both online and paper-based applications. One administrator advocated for this method, explaining,

our goal is to do everything online. But we know, a significant portion of the population can't do that. So, you have to put support in place to help the people that [aren’t] able to do it. Or else you're going to miss a whole chunk of people that really need the money.

Another said,

I think one of the pieces of feedback that we've gotten and really tried to learn from, from community-based groups, is that oftentimes, the application itself is the biggest barrier to access for tenants, particularly those that are in incredibly vulnerable situations. So being as flexible as possible and adaptive as possible in terms of the different ways that folks can complete an application.

One interviewee recalled an exchange with an applicant, related to the struggles of online applications, as follows: “‘I don’t have my bank statements.’ Oh, well, can you put them out online? ‘I don’t have access to a computer.’ Great, then go to the bank. ‘I can't afford to get a copy.’” These exchanges illustrate that even tools meant to ease access for applications can sometimes be prohibitive for the most vulnerable. A final interviewee illustrated this dynamic succinctly in reflecting that some applicants

had to come in, and we had to create them an actual email account just so we could get them signed up to get them help. So, the reality is that when something like this hits and things go virtual and you lose contact with people, there is a sector of society that's going to be marginalized.

Subsidy Structure and Amount

Another potential barrier to vulnerable households is the subsidy recipient. If programs required payment to go to the landlord on behalf of an eligible tenant, they created two distinct challenges. One challenge relates to process; requiring tenants to engage their landlords in the application process increases its complexity, particularly for tenants who do not know their landlord well. The second challenge relates to consent; by giving landlords the power to reject payments, emergency rental assistance programs may exclude tenants with adversarial relationships with their landlords, or whose landlords are reluctant to engage with government programs (e.g., because their units are not up to code or are not currently taxed). Unfortunately, these are symptoms of unstable housing situations, placing households at greater risk of homelessness.

Allowing payments to flow directly to the tenant lowers this barrier. In 2020, only a very small share (9%, N = 220) of programs surveyed allowed payments to tenants, but at least some of these made the payment directly to tenants from the get-go, without ever asking tenants to provide landlord contact information. In 2021, a larger share (65%, N = 64) of respondents reported allowing payments to tenants, but only in the event of landlord nonresponse or noncooperation, as required by the ERA1 funding statute.

Interestingly, one respondent cited their program’s goal of preventing homelessness as a reason to distribute funds directly to landlords, rather than to tenants who, the administrator feared, might spend the funds on nonhousing expenses. They noted, “if the intention is, I want their rent to be paid so that they don't become homeless or go through the eviction process, I think we have to safeguard it. I think we have to be more intentional.” This response highlights a longstanding skepticism about providing assistance directly to tenants, which gives all agency and authority to owners and is not founded in any empirical evidence. Many programs attempted to balance the tenant–landlord power imbalance by placing eviction restrictions on property owners who received rental assistance on behalf of eligible tenants (78% in 2020, N = 152, and 76% in 2021, N = 49). In theory, these restrictions should have reduced the risk of eviction for the duration of the rent relief benefit in those places. However, interviews showed that programs struggled to track, let alone enforce, compliance. Thus, it is unclear whether any such restrictions actually lower the odds of eviction.

The amount of the subsidy also has important implications for homelessness prevention. In 2020, surveyed rental assistance programs provided subsidy amounts ranging between $500 and $5,160 (N = 89), with a median of $1,200 per household per month and an average of $1,716 per household per month (N = 82). The majority of programs offered assistance for 3 months or less (N = 103). For many households this benefit did not cover the totality of their rent arrears, much less the full cost of future rent (Reina, Aiken, & Goldstein, Citation2021). Participating landlords could therefore receive rental assistance payments on behalf of households still in arrears, and still at risk of eviction due to nonpayment. Many households that applied for rental assistance managed this risk by taking on other forms of debt to repay their rent arrears, but this nonrent debt was not reimbursable by ERA programs and could also threaten households’ finances and housing stability (Reina & Goldstein, Citation2021). By 2021, most programs covered at least 3 months of forward rent (94%, N = 52) and more than 6 months of arrears (96%, N = 58) and tailored the amount of the assistance to tenant need (98%, N = 58), likely reducing the risk of eviction and homelessness for participating households.

Conclusion

Based on nationwide survey responses and interviews with a subset of respondents, we find that emergency rental assistance administrators did intend for their programs to prevent homelessness, but this goal often did not translate into outreach methods, eligibility criteria, documentation requirements, and subsidy structure that would target funds to those at most immediate risk of homelessness. Instead, program designs typically favored upstream targeting and maximizing the number of low-income households receiving funding. Many programs also required documents that would be difficult for vulnerable households to gather, and some did not allow direct-to-tenant payments, which may have discouraged tenants who have a weak or adversarial relationship with their landlord, or whose landlords are wary of participating in government programs, from applying. Given vulnerable households’ struggles to produce application documentation, and the fact that programs allowing self-attestation of tenancy were more successful in distributing their allocations than those that never adopted self-attestation (Aiken et al. Citation2021), programs seeking to use rental assistance to prevent homelessness should consider easing their documentation requirements related to tenancy. Program designers should also be mindful of the extra administrative burden that can result from requiring the most vulnerable households to apply electronically; as our interviews showed, the increased efficiency of online application systems does not extend to all applicants, and the most vulnerable households sometimes lack internet access or the ability to provide documentation in digital format. Programs should plan for these challenges accordingly, ensuring staff or nonprofit partners have the capacity to assist vulnerable applicants in tasks such as setting up digital accounts and receiving email correspondence.

All of this speaks to the difficulty of designing programs to reach those at greatest risk of homelessness—those who have experienced previous spells of homelessness, survivors of domestic violence, veterans, those with mental illness, those with very low incomes, and those facing eviction or living in otherwise tenuous housing situations—while still getting money out the door quickly during an emergency and minimizing waste, fraud, and abuse. But it does not reflect on the ability of rental assistance to further other important goals, such as preventing low-income families from sacrificing necessities to pay for housing, or keeping renters stably housed amid a global pandemic.

It is also possible that, by adopting broad-based strategies at a scale adequate to serve all households with need, emergency rental assistance programs could constitute an effective homelessness prevention tool. Interviews suggested that program administrators often viewed homelessness as the final step in a series of destabilizing events and saw rental assistance as an upstream tool that could interrupt this process before downstream tools, such as eviction diversion and case management, become necessary. Importantly, this paper cannot present evidence on the degree to which emergency rental assistance programs are actually succeeding in preventing or reducing homelessness. Much more research is needed to evaluate the impact of receiving rental assistance on individual households, and the relationship between rental assistance program design and homelessness rates on a community level. Future work should also evaluate how the experience of emergency rental assistance, which temporarily expanded the nation’s housing safety net to an unprecedented degree, can inform longer-term efforts to address a broad set of housing needs beyond homelessness prevention.

Disclosure Statement

Vincent J. Reina’s contributions to this article occurred prior to his position as the Senior Policy Advisor for Housing and Urban Policy in the White House Domestic Policy Council and reflects his personal views only.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Claudia Aiken

Claudia Aiken, MCP, is Director of the Housing Initiative at Penn at the University of Pennsylvania.

Ingrid Gould Ellen

Ingrid Gould Ellen, PhD, is the Paulette Goddard Professor of Urban Policy and Planning at New York University Wagner and Faculty Director of the NYU Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy.

Isabel Harner

Isabel Harner, MCP, is a recent graduate of the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of Pennsylvania.

Tyler Haupert

Tyler Haupert, PhD, is Assistant Professor Faculty Fellow of Urban Studies at New York University Shanghai.

Vincent Reina

Vincent Reina, PhD, is Associate Professor in the Department of City and Regional Panning at the University of Pennsylvania and Faculty Director of the Housing Initiative at Penn.

Rebecca Yae

Rebecca Yae, MURP, is a Senior Research Analyst for the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Notes

1 Similarly, Ellen and O’Flaherty (Citation2010) divide policies into (a) broad-based policies that reduce the price of housing; (b) traditional housing subsidies for low-income households; and (c) policies that aim more directly at the population at highest risk.

2 For ERA1, a household is considered low income when it is at or below 80% of AMI. For ERA2, a low-income family is defined by the United States Housing Act of 1937 (families with a household income below 80% AMI, as determined by the HUD Secretary with adjustments for smaller and larger families, except that the Secretary may establish income ceilings higher or lower than 80% of AMI).

3 Only 17 programs captured in 2020 were resurveyed in 2021, and in five cases the program administrator had changed.

References

- Aiken, C., Reina, V., Verbrugge, J., Aurand, A., Yae, R., Ellen, I. G., Haupert, T. (2021). Learning from emergency rental assistance programs: Lessons from Fifteen Case Studies. Housing Initiative at Penn, National Low Income Housing Coalition, and NYU Furman Center. https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/ERA-Programs-Case-Study.pdf

- Collinson, R. A., Humphries, J. E., Madar, N., Tannenbaum, D., Reed, D., & van Dijk, W. (2022). Eviction and poverty in American Cities: Evidence from Chicago and New York. Working Paper.

- Coronavirus Relief Fund for States. (2021, January 15). Tribal Governments, and certain eligible governments; Department of Treasury CRF Program Guidance, 86 FR 4182.

- Ellen, I. G., & Brendan, O. (2010). Introduction. In eds. I. G. Ellen & B. O’Flaherty, How to House the Homeless. Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN 978-0-87154-454-4.

- Ellen, I. G., Muscato, B. M., Aiken, C., Reina, V., Aurand, A., Yae, R. (2021). Advancing racial equity in emergency rental assistance programs. NYU Furman Center, Housing Initiative at Penn, and National Low Income Housing Coalition. https://furmancenter.org/files/Advancing_Racial_Equity_in_Emergency_Rental_Assistance_Programs_-_Final.pdf

- Emeruwa, U. N., Ona, S., Shaman, J. L., Turitz, A., Wright, J. D., Gyamfi-Bannerman, C., & Melamed, A. (2020). Associations between built environment, neighborhood socioeconomic status, and SARS-CoV-2 infection among pregnant women in New York City. JAMA, 324(4), 390–392. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.11370

- Evans, W. N., Phillips, D. C., & Ruffini, K. (2021). Policies to reduce and prevent homelessness: What we know and gaps in the research. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 40(3), 914–963. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22283

- Evans, W. N., Sullivan, J. X., & Wallskog, M. (2016). The impact of homelessness prevention programs on homelessness. Science, 353(6300), 694–699. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aag0833

- Fowler, P. J., Hovmand, P. S., Marcal, K. E., & Das, S. (2019). Solving homelessness from a complex systems perspective: Insights for prevention responses. Annual Review of Public Health, 40, 465–486. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013553

- Goodman, S., Messeri, P., & O'Flaherty, B. (2016). Homelessness prevention in New York City: On average, it works. Journal of Housing Economics, 31, 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2015.12.001

- Greer, A. L., Shinn, M., Kwon, J., & Zuiderveen, S. (2016). Targeting services to individuals most likely to enter shelter: Evaluating the efficiency of homelessness prevention. Social Service Review, 90(1), 130–155. https://doi.org/10.1086/686466

- Gubits, D., Shinn, M., Bell, S., Wood, M., Dastrup, S. R., Solari, C., Brown, S., Brown, S., Dunton, L., Lin, W., McInnis, D., Rodriguez, J., Savidge, G., & Spellman, B. (2015). Family options study: Short-term impacts of housing and services interventions for homeless families. Abt Associates for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

- Haupert, T. (2021). Do housing and neighborhood characteristics impact an individual’s risk of homelessness? Evidence from New York City. Housing Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.1982874

- HEARTH Act, 42 U.S.C. § 11302 (2009). https://www.hud.gov/sites/documents/HAAA_HEARTH.PDF

- Henry, M., Bishop, K., de Sousa, T., Shivji, A., Watt, R. (2018). The 2017 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress Part 2: Estimates of Homelessness in the United States. Retrieved from: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2018-AHAR-Part-2.pdf

- Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing Act of 2009. (2009). 42 U.S.C. §11302

- Kuehn, B. M. (2020). Homeless shelters face high COVID-19 risks. JAMA, 323(22), 2240 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.8854

- Leifheit, K. M., Linton, S. L., Raifman, J., Schwartz, G. L., Benfer, E. A., Zimmerman, F. J., & Pollack, C. E. (2021). Expiring eviction moratoriums and COVID-19 incidence and mortality. American Journal of Epidemiology, 190(12), 2503–2510. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab196

- National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty. (2018). Protect tenants, prevent homelessness. https://homelesslaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/ProtectTenants2018.pdf

- National Low Income Housing Coalition. (2020–2021). COVID-19 rental assistance database [Data set]. Retrieved from: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1hLfybfo9NydIptQu5wghUpKXecimh3gaoqT7LU1JGc8/edit#gid=79194074.

- Notice of Program Rules, Waivers, and Alternative Requirements Under the CARES Act for Community Development Block Grant Program Coronavirus Response Grants. (2020). Fiscal Year 2019 and 2020 Community Development Block Grants, and for Other Formula Programs, 85 FR 51457 (August 20).

- O’Flaherty, B. (2010). Homelessness as bad luck: Implications for research and policy. In I. G. Ellen & B. O’Flaherty (eds.), How to house the homeless. Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN 978-0-87154-454-4.

- O’Flaherty, B. (2019). Homelessness research: A guide for economists (and friends). Journal of Housing Economics, 44, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2019.01.003

- O’Flaherty, B., Scutella, R., & Tseng, Y. P. (2018). Using private information to predict homelessness entries: Evidence and prospects. Housing Policy Debate, 28 (3), 368–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2017.1367318

- Reina, V., & Aiken, C. (2021). Fair housing: Asian and Latino/a experiences, perceptions, and strategies. The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 7(2), 201–223. https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2021.7.2.10

- Reina, V., Aiken, C., Goldstein, S. (2021). The need for rental assistance in Los Angeles City and County. Research Brief, Housing Initiative at Penn. https://www.housinginitiative.org/uploads/1/3/2/9/132946414/hip_la_tenant_brief_final.pdf

- Reina, V., Goldstein, S. (2021). An Early Analysis of the California COVID-19 Rental Relief Program. Research Brief, Housing Initiative at Penn. https://www.housinginitiative.org/uploads/1/3/2/9/132946414/hip_carr_7.9_final.pdf

- Rolston, H., Geyer, J., Locke, G. (2013). Evaluation of the Homebase Community Prevention Program: Final Report. Abt Associates Inc. https://www.abtassociates.com/insights/publications/report/evaluation-of-the-homebase-community-prevention-program-final-report

- Shinn, M., & Khadduri, J. (2020). In the Midst of plenty: Homelessness and what to do about it (p. 134). Wiley Blackwell.

- Shinn, M., Greer, A. L., Bainbridge, J., Kwon, J., & Zuiderveen, S. (2013). Efficient targeting of homelessness prevention services for families. American Journal of Public Health, 103(S2), S324–S330. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301468

- Smith, N., Flores, Z. D., Lin, J., Markovic, J. (2005). Understanding family homelessness in New York City. Vera Institute of Justice. https://www.vera.org/publications/understanding-family-homelessness-in-new-york-city-an-in-depth-study-of-families-experiences-before-and-after-shelter

Appendix

Survey Sample Size and Distribution

The survey sample was selected using the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s (NLIHC) COVID-19 Rental Assistance Database (National Low Income Housing Coalition Citation2020--2021), a comprehensive database of emergency rental assistance programs created or expanded in response to COVID-19 and some of their key features. NLIHC populates the database with public information shared on each program’s website, supplemented in some cases by communication with program administrators themselves, and updates it on an ongoing basis.

Online surveys were sent to the administrators of all programs in the NLIHC’s database for which email address information was available. NLIHC collects program administrators’ email addresses from program webpages and online agency directories. When contact information could not be determined in this way, NLIHC reached out to state partners directly. In some cases, state agencies were asked to share the survey with their local program administrators on the researchers’ behalf.

The first survey, launched in August 2020, collected responses during the months of August, September, and October. At the time of the survey’s launch, the NLIHC database included 322 rental assistance programs created or expanded in response to COVID-19. Because the survey was further distributed to local program administrators through some state partners, it was ultimately circulated to over 425 program administrators and received 220 responses, representing a response rate of approximately 48%. Most of the programs surveyed in this initial round (about 80%) relied, at least in part, on funding from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, enacted in March 2020. These survey data represent the earliest iterations of emergency rental assistance programs.

We conducted a second survey of emergency rental assistance programs from April 1 through April 30, 2021. This survey was distributed to a subset of 140 programs in the NLIHC database which were funded by the Treasury Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) Program and were determined to have launched by April 8. A total of 64 programs completed the survey, representing a response rate of approximately 46%. This second survey sample is composed of “early implementers” who were able to launch a program or a new iteration of an existing program within 2 months of the U.S. Treasury publishing initial guidance for the use of ERA funds.

Survey Questionnaire

The full 2020 survey, which was hosted in Qualtrics, included 111 questions related to program design, documentation, and eligibility. We administered an abbreviated version of the survey to localities implementing a program that had been designed at the state level, and which therefore would vary only with respect to certain aspects of program implementation from locality to locality. The 2021 survey, with a total of 85 questions, included many of the same questions but removed questions related to only the second phase of the program and short-answer questions on program challenges. The 2021 survey also expanded some answer choices and added questions related to quantifying program changes over time as well as those related to equity and outreach approaches.