Abstract

Displacement research emphasizes the importance of housing market processes and their consequences for tenants. In recent years, a lively discussion in housing studies has emerged around policy mechanisms to promote permanently decommodified housing and nonprofit landlord types. This article picks up on the two strands of research and links them to our own empirical material from two studies on the city of Berlin that respond to two questions: (a) What role do the different landlord types play in processes of displacement? and (b) To what extent are the management strategies of nonprofit landlords equipped to dampen displacement processes? Our results, which are based on quantitative and qualitative analyses, show that public housing companies, cooperatives, and novel shared homeownership models pose a significantly lower risk of displacement. Although these landlord types do not prevent displacement entirely, their property management strategies, their self-understanding, and their networks make it possible to identify housing policy levers to minimize displacement.

Given the shortage of affordable housing in many cities around the world, displacement in urban housing markets has become a topical field of urban research. Although most studies focus on the social and spatial consequences of displacement in the context of gentrification, some address the causes and analyze what prompts tenants to give up their flats. The role of various landlord types in the context of displacement processes, however, has so far gained scant attention.Footnote1 Of course, when gentrification and displacement are seen as the outcome of rent or value gaps, landlords also play a role—but they are usually dealt with in a somewhat general way as the exploiters of land value. Thus, there is comparatively little scholarly account of how certain ownership-specific management strategies of residential real estate impact on displacement processes. This lack of knowledge is particularly unfortunate with respect to nonprofit landlords as their (assumed) potential to relieve existing pressures on the housing market plays an important role in current housing policy debate. Against this backdrop, Clark (Citation2014) notes a gap in the transformational knowledge relevant to reducing displacement.

A growing number of cities have set up initiatives and municipal subsidy programs to support the various types of nonprofit housing. Munich, Germany, for instance, intends to boost cooperative real estate construction and is gearing its local land policy toward this goal with its Socially Responsible Land Use concept (SoBoN). Likewise, municipal support programs and civil society intermediaries have been created in Barcelona, Spain, within the last decade and yielded several new housing cooperatives (Martí-Costa & Ferreri, Citation2021). Given such an engaged promotion of “common welfare-oriented” real estate development in various cities, it appears desirable to explore whether such programs can actually help to prevent displacement.

With this article, we contribute to closing the gaps we outlined by addressing the following questions: (a) What role do the different owner types play in processes of displacement? and (b) To what extent are the management and exploitation strategies of nonprofit landlord types (public housing companies, tenant cooperatives, and novel shared homeownership models) equipped to dampen displacement processes? We will do so by taking Berlin as an example and drawing on our own empirical material from two research projects. We see Berlin as an excellent case study for our purpose because, on the one hand, it displays all the basic features of a fairly tight capitalist housing market that allows providers of private housing to resort to specific management strategies to close existing rent gaps. On the other hand, quite a few initiatives and organizations have evolved in Berlin recently that strive for socially responsible housing provision beyond the market. First, we will look at what is already known about the ability of nonprofit landlords to tame displacement dynamics, which will require us to relate the two somewhat separate strands of research on displacement and on nonprofit landlords to each other (1). We then introduce our case study, the Berlin housing market (2). After a methods section (3) we present our findings on the role of various landlord types in displacement (4). From there, we establish the degree to which Berlin’s public housing companies, cooperatives, and novel shared homeownership models avoid displacement and discuss the underlying reasons (5). Finally, we summarize our findings, derive some housing policy considerations for Berlin and beyond, and reflect on the scope and limits of our observations (6).

The Objects of Research: Displacement in the Context of Profit- and Nonprofit-Oriented Landlord Types

Tenant displacement is often associated with gentrification (Hirsh et al., Citation2020, p. 394) or even considered constitutive and the essential problem of gentrification (Davidson & Lees, Citation2005, p. 1187; Slater, Citation2006, p. 748). In the literature on gentrification, however, displacement is understood as a variety of phenomena (Beran & Nuissl, Citation2023, p. 2; Elliott-Cooper et al., Citation2020, p. 493). Marcuse made a significant contribution to sharpening the concept in 1985 (pp. 204–208). He distinguished direct tenant displacement through physical (e.g., turning off the heating by the property management) or economic (e.g., rent increases) measures from the indirect form of exclusionary displacement which occurs, for example, when a household with the same socioeconomic status as a household moving out cannot afford that now-vacant flat because it is renting for a higher price. Marcuse also discusses displacement pressure, which occurs when people move because they no longer feel comfortable in a changing neighborhood. Other authors expand the concept of displacement pressure by applying it to tenants who do not move but abstain from using public space (e.g., parks) where they no longer feel comfortable (e.g., Valli, Citation2015), in particular because "norms, behaviours and values" have changed due to the influx of other population groups (Hyra, Citation2015, p. 1754). Yet other authors’ definitions of displacement emphasize the involuntary nature of the decision to move (e.g., Kearns & Mason, Citation2013; Watt, Citation2018, p. 71) or its extension in time (displacement as a process rather than a snapshot; e.g., Elliot-Cooper et al., Citation2020, pp. 501–502; Sakizlioğlu, Citation2014, pp. 16–17). In this paper, we focus on direct forms of displacement that are associated with people moving out of rented housing. We look at displacement from the individual perspective of tenants and use a decision-theoretical approach from migration research to operationalize the phenomenon, which can depict the complexity of relocation decisions. According to this, people may experience pressure due to external changes such as an increase in rent, to which they might react by moving. These external factors can thus be seen as displacement factors (see the Data and Methods section). On this basis, we define displacement, following Grier and Grier (Citation1980, p. 256), as moving out of a rented dwelling due to adverse changes in tenancy arrangements that (a) affect the tenancy of the moving household; (b) cannot be controlled or avoided by the person(s) moving (i.e., they can even occur if all the obligations prescribed in the tenancy agreement are fulfilled); and (c) have significantly contributed to the decision to move. This approach is commonly used in research (e.g., Atkinson, Citation2000; Freeman & Braconi, Citation2004; Newman & Wyly, Citation2006).

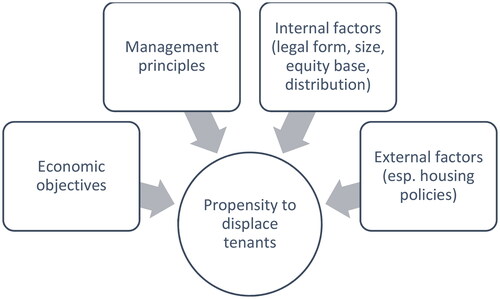

Tenant displacement is closely related to the economic objectives of landlords and the management strategies of landlords (i.e., how they organize their real estate property), as well as to further internal (e.g., size, equity base of the company, professionalization) and external (e.g., housing policies, interpretative frames) factors (see ). Holm (Citation2023, pp. 95–96) points out three major management strategies that are particularly true for profit-oriented landlords (e.g., housing companies, institutional investors or private landlords): (1) the predominantly long-term interest on assets through rental income; (2) maximizing short-term profit from land-related incomes by the varying use of profitability strategies such as modernization measures, rent increases, cost savings on tight housing markets (disinvestment, building administration), or buy-and-sell strategies (as described by Christophers Citation2022); and (3) profit through increasing real estate values by use of varying strategies and time horizons (see also Üblacker, Citation2023). Clearly, management strategies cannot operate independent of existing political framework conditions. Housing policies such as regulation tools, in particular, can reduce displacement risks.

In current debates on definancialization of housing and housing commoning as a way out of tenant displacement (Wijburg, Citation2021), nonprofit landlord types such as public housing companies, cooperatives, and novel shared homeownership models are taking a prominent role (Bates, Citation2022; Ferreri & Vidal, Citation2022). Shaw (Citation2005), for instance, points to the relevance of these kinds of landlords when it comes to taming housing market dynamics in Australia. For European cities, Kadi (Citation2022) and Schipper & Latocha (Citation2018) highlight the need to decommodify the real estate sector by shoring up public housing corporations and rent control. There is a broad variety of nonprofit landlords that differ in their role in the housing market and thus with respect to displacement. Based on the categorization of landlords according to the legal structure of real estate ownership in our empirical analysis, we distinguish three types of nonprofit landlords:

Public housing companies that manage housing stock that is (completely or partially) owned by municipalities, regions, and/or the federal state. The state can intervene in the corporate strategies of these “hybrid organizations” (Mullins et al., Citation2018, p. 585), which are tasked with bringing diverse public and entrepreneurial logics and interests together. The role of these companies in the housing market is largely dependent on the respective political composition of the government and may range between the provision of social housing via (subsidized) rent regulations and stock expansion (cf. Bernt & Holm, Citation2023), on the one hand, and profit-making under austerity conditions with management strategies such as upgrading and privatization (Baeten et al., Citation2017; Uffer, Citation2011), on the other.

Housing cooperatives are primarily based on shared ownership and limited equity, and are funded by membership fees, rents and one-time refundable deposits. This landlord type is assumed to raise rents moderately. In the following we will focus on two types of tenant cooperatives as the prevailing form of housing cooperativesFootnote2 in German-speaking countries with a long cooperative tradition: First, mature cooperatives with large housing stocks of several thousand units partly dating back to the end of the nineteenth century, workers’ movements, or post-Second World War foundations (cf. Barenstein et al., Citation2022; Metzger, Citation2021) and, second, a young cooperative scene established in the 1980s in Germany and more recently in countries such as Spain (Cabré & Andrés, Citation2018). Although the first tend to focus on maintaining the stock and existing members, the innovative (but solitary) character of new cooperative formations is frequently stated, for example in terms of diversity, participation, mutual aid, and expansion (Czischke, Citation2018).

Novel shared homeownership models that, similar to cooperatives, dispose of shared ownership structures. However, in order to guarantee specific principles such as self-governance, decommodification of land and real estate, solidarity and access for broader communities, new (legal) organizational forms have been invented over the last few decades in addition to existing cooperatives. The novel shared homeownership models include common good-oriented land foundations that buy and grant land to housing projects (with varying organizational structures) under a ground lease, which is reinvested in further projects. They also include housing syndicates—in Germany mainly represented by the Mietshäuser Syndikat—which consist of a solidary amalgamation of self-managed housing projects. Solidarity contributions and the solidary knowledge transfer to new initiatives allow for continuous although moderate expansion of housing syndicates. Both models are ensured against the sell-off of real estate and/or land by the organizational separation into formally independent legal entities of, on the one hand, the housing associations themselves and, on the other hand, a higher-level organization (e.g., a land foundation or umbrella organization such as the Mietshäuser Syndikat; Hölzl, Citation2022; Horlitz, Citation2021).Footnote3

The ability of nonprofit landlords to provide affordable housing and tame displacement processes in view of soaring housing markets is—and always has been—dependent on government support (e.g., in Switzerland, Austria, and the Netherlands), notably through land transfer (sale at a reduced price or allocation via leasehold; Balmer & Gerber, Citation2018; Blau et al., Citation2019; Ferreri & Vidal, Citation2022).

The Berlin Housing Market and Ownership Structures

Berlin has a population of around 3.7 million, living in some 1.998 million housing units. Because no more than 0.31 million Berlin households live in their own house or flat, approximately 84% of all housing units (1.679 million) is rental stock (IBB, Citation2022, pp. 36–37). Hence, the Berlin housing market is still predominantly a rental market, a salient difference from cities like London or Madrid (Cosh & Cleeson, Citation2020, p. 27; Statista, Citation2020). The vast majority of flats (87%) are located in multistorey dwellings (IBB, Citation2022, p. 36). Today, the Berlin rental housing market is undoubtedly tight. This is due to the growing demand for housing, but also to developments on the supply side of the housing market (Holm, Citation2020, pp. 43–45). The number of inhabitants has grown by 11% in the last 15 years. What is more, the decline of household sizes has led to a greater number of households. New housing construction is progressing at a more moderate pace and is not keeping up with the soaring demand for housing.

Against this background, the Berlin government has made a new commitment to guarantee an adequate housing supply. The Housing Provision Act of 2016 created new opportunities to regulate the housing market, abolished profit distribution from public housing companies to the state of Berlin, and put tenant participation on the political agenda. Correspondingly, the six existing public housing companies in Berlin, which sold about half of their former housing stock to private investors, in particular private equity funds, during the 1990s and 2000sFootnote4 (Kitzmann, Citation2017; Uffer, Citation2011) have been enlarging their portfolio since 2012 via new construction and acquisition. Besides, Berlin also follows the international trend of setting up new community-based housing cooperatives and novel shared homeownership models. The vast majority of new flats, however, are still being sold (as freehold flats; cf. BBSR, Citation2016) or rented out in the top segment of the rental market. A considerable number of existing rental flats are also being converted into freehold flats every year in Berlin. In 2021, 28,768 had undergone this conversion, i.e., approximately 1.7% of the entire rental housing stock. For the last decade, this figure has been stable and is even substantially higher in inner-city districts (up to 2%/year; IBB, Citation2022, pp. 38–39).

The developments outlined above have led to a significant rise in prices for rental housing. Whereas the average net asking rent for flats on offer in Berlin was €6.00/m2 in 2010, this figure had risen to 10.70 €/m2 by mid-2018, an increase of almost 80% (IBB, Citation2020, p. 64). Net rents in Berlin also increased—from €4.83/m2 to €6.72/m2 on average in the period from 2008 to 2016, and thus by about 4%/year, although rent increases for existing tenancy agreements are only permitted within legally prescribed limits in Germany (IBB, Citation2020, p. 70). By comparison, the nation-wide annual increase in existing rents only amounted to between 1.1% and 1.5% from 2010 to 2015 (BBSR, Citation2016, p. 95).

Recent trends in the Berlin real estate and housing markets are reflected in the contemporary ownership structure of the Berlin housing sector (): The lion’s share (more than 70%) of Berlin’s total rental housing lies in the hands of market actors who are profit-oriented one way or another. Although some 30% of rental housing belongs to private companies, approximately 41% is in the hands of private landlords. It is estimated that around one third of the landlord type private companies are actually housing companies and two thirds are companies whose core competence is financial transactions (e.g., private equity funds) rather than housing. Also, around half the flats owned by “private landlords” are in the hands of individuals with a significant stock of houses (>50) and thus act very much like companies on the housing market (cf. Hochstenbach, Citation2022 for the Netherlands), whereas the other half is in the hands of small-scale landlords who may treat their houses in very different ways, but as a group should also be regarded as profit-oriented owners (cf. Trautvetter, Citation2020). Berlin’s nonprofit-oriented housing sector is predominantly organized in six public housing companies (e.g., DEGEWO or Stadt und Land) owned by the state of Berlin (17% of all rental housing). Another 11% of all rental housing belongs to more than 100 housing cooperatives. Whereas 10 of the older and more traditional cooperatives own at least 5,000 flats each (e.g., Charlottenburger Baugenossenschaft eG, WGLi Wohnungsgenossenschaft Lichtenberg eG, etc.), the younger, smaller cooperatives (e.g., Bremer Höhe) are in possession of almost 5,000 flats altogether (Urban Coop Berlin, Citation2018) and thus play only a minor role in the housing market in quantitative terms. The same holds for novel shared ownership models: At the time of collection of the data, 21 of the 174 house projects of the Mietshäuser Syndikat in Germany are located in Berlin; the Edith Maryon Foundation owns 138 real estate projects in Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, and France, 20 of which are located in Berlin, along with another 47 leasehold projects belonging to the same foundation (Stiftung Edith Maryon, Citation2020); the trias Foundation owns 47 leasehold projects, 14 of which are in Berlin (Stiftung trias, Citation2020). Furthermore, approximately 20,000 flats belong to noncommercial organizations (such as churches), and about 100 others belong to individual housing associations. Because it is impossible to determine the unequivocal goals of the latter (potentially) nonprofit-oriented owners, we will not cover them in what follows.

Table 1. Ownership structure of the rental housing stock in Berlin (2011).

Data and Methods

The city of Berlin serves as a case study in this paper to analyze the extent to which nonprofit landlords can help to prevent displacement. The insights into the Berlin housing market and the role of nonprofit landlords therein presented in the following sections rest on the quantitative and qualitative research of the authors.

In a first step, we conducted a standardized survey to find out whether movers within Berlin were displaced. As our study area we chose the two inner-city districts of Mitte and Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, due to their particularly tight housing market and high share of rented housing. As the basic population we chose tenants who had moved out of their flat in the study area and moved to flats in other parts of Berlin between September 2013 and August 2015. (Hence, our survey covers only tenants who moved and does not allow for conclusions about residents who did not move, although they, too, may have experienced displacement triggers). Out of this basic population of 107,525 movers, we randomly selected 10,000 adults from the Berlin population register and sent them a questionnaire by post; 1,170 questionnaires could not be delivered, presumably because the current address in the register was incorrect. The postal survey was organized along the lines of the Tailored Design Method (Dillman et al., Citation2014) to reduce dropouts due to nonresponse. We contacted the selected individuals three times. The questionnaire could be completed in hard copy or online and was available in English, German, and Turkish.

We retrieved 2,466 questionnaires, 2,082 of which were analyzed (incomplete questionnaires and those from persons not belonging to the basic population were excluded), and thus achieved a utilization rate of 23.8% (of the 8,759 questionnaires delivered), which is within the range of comparable studies (Dillman et al., Citation2014). We estimated the bias using characteristics of the sample we know from the population register. The survey is representative in terms of age and current place of residence of the respondents. Males and persons with a nationality other than German are underrepresented. For other sociodemographic characteristics, we cannot reliably indicate biases. We assume, however, that people with low incomes and low levels of education are somewhat underrepresented, as these population groups participate less often in surveys.

In analyzing the survey data we identified displaced respondents on the basis of their reasons for moving. Respondents who mentioned at least one of the following tenancy-related displacement triggers as a primary reason for moving were classified as displaced: (a) structural upgrading (modernization and energy rehabilitation), (b) disturbances to living due to construction noise, scaffolding and/or flat inspections, (c) sale of houses or flats, (d) rent increases, (e) terminations (not due to tenant misconduct), (f) pressure from the landlord, and (g) structural decay. These triggers applied to 313 respondents who were thus classified as displaced. Hence, we calculated a displacement rate of about 15%, which—if extrapolated to the basic population of 107,525 movers—is tantamount to a total of some 16,000 displaced tenants in our study area in the course of two years (2015–2016), or about 8,000 tenants per year. This means that approximately 1.3% of the total residential population of the study area is being displaced every year.

Although we conceptualized and measured displacement at the level of (moving) individuals in our survey, it is also possible to conceptualize it at the housing unit level. This allows us to compare expected and real displacement figures for different landlord types and to check whether certain owner types displace tenants more frequently than the average. Consequently, we also applied this approach to our results.

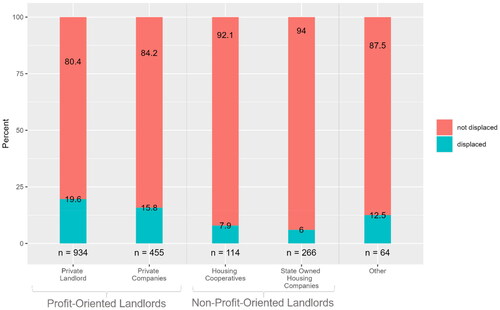

Prior to moving, the landlord of almost half of all respondents was a private landlord, whereas that of almost a quarter of all respondents was a private company (see ). By contrast, the proportion of people who had rented their flat from a nonprofit-oriented landlord was only around 20%. These figures deviate from the Berlin average, where more tenants rent from nonprofit-oriented landlords (). This reflects the inner-city location of our study area, where the share of large housing estates is below average and the share of old tenement buildings, which are largely owned by individuals, is above average.

Table 2. Distribution of landlord types in the study area.

In a second step, we brought in a qualitative study of 33 problem-centered interviews with various stakeholder groups in 2018 and 2019, which we conducted using the snowball principle: politics and administration (11 interviews), public housing companies and interest groups (2), housing cooperatives (6), land foundations and the Mietshäuser Syndikat (6), grassroots initiatives (3), financial institutions and consulting intermediaries (3), and experts (2). The entire interview corpus was used to understand and classify the strategies and mutual interaction of nonprofit landlords in the context of housing politics in Berlin. Ten of these interviews, primarily with representatives from the three nonprofit landlord types, were used to substantiate the second research question ().Footnote5 We analyzed the transcribed interviews by means of a set of basic analytical categories that we deem relevant to the research questions (see ). Using a thematic coding method (Froschauer & Lueger, Citation2003), we refined these categories and complemented them with additional subcategories that we derived inductively in the course of coding the interview material.

Table 3. Interview sample.

This allowed us to identify and structure the management strategies of nonprofit landlords and classify these strategies and underlying economic rationales by means of interviewee assessments. The qualitative interviews were accompanied by a document analysis of the Berlin housing policy and the role of nonprofit landlords on housing markets (for the years 2012–2021). Based on this material, we subsequently drew conclusions on the extent to which these landlord types are in a position to contribute to the prevention of displacement, but also on their limits in this regard.

Displacement and Landlord Types

Based on a comparison between respondents classified as displaced and those classified as not displaced, our survey among moving households in Berlin reveals that landlord types differ when it comes to the likelihood of their tenants to be displaced (). The highest displacement rate of almost 20% was recorded for tenants who lived in flats belonging to private landlords. The second most displaced tenants are those who lived in flats owned by private housing companies. Their displacement rate is 15.8%, i.e., slightly above average. Tenants who lived in housing belonging to housing cooperatives or state-owned housing companies were displaced to a much lesser degree.

Figure 2. Displacement rate by landlord type (based on moving households).

Source: Authors’ own survey, N = 1,833. Since not all respondents were able to indicate the ownership type of their rental property before they moved, N is significantly lower than the overall response of 2,082 questionnaires.

If we assess displacement at the housing unit level (by extrapolating the absolute number of displacements by landlord type per year, applying the displacement rate of landlord types given in to the housing stock of each landlord type given in ), we arrive at similar conclusions (see ): Indeed, the landlord type “private companies” overperforms with a displacement rate of 1.7% per annum in relation to all tenants of the respective neighborhoods, and the two big nonprofit landlord types (state-owned housing companies and housing cooperatives) underperform (with displacement rates of 0.5% and 0.7% in relation to all tenants of the respective neighborhoods of 0.5% and 0.7%). However, this calculation includes quite a few assumptions and estimations (reliability of small-scale micro-census data on housing; constant population in the study area for the survey period [2013–2015]; and constant share of landlord types of the entire housing stock between 2013 and 2018).

Table 4. Displacement rate by landlord type (based on absolute number of housing units).

To further analyze the management strategies of rental landlord types, we looked at the displacement triggers that respondents experienced before moving ().Footnote6 Rent increase is the most common displacement factor for all landlord types. Although slightly more than a quarter of the respondents who lived in flats belonging to a state-owned housing company or cooperative experienced a rent increase, the figure was about a third for former tenants of private landlords and private companies. Insufficient maintenance in buildings or flats was evident to considerably varying degrees among the different landlord types: Approximately one in five former tenants of private individuals or companies reported they had been affected, compared to about 6% of former tenants of other landlord types. A similar, albeit less pronounced, tendency was observed for other displacement triggers: First, sale of houses and/or flats and, second, disruptions to living due to construction noise and/or flat inspections. Most respondents who state they had been pressured to move out via one of these triggers lived in housing owned by private individuals or companies. Comparatively few respondents were affected by termination of their lease; the vast majority of these were given notice to leave by private landlords, because German tenancy law only permits this landlord type to terminate a lease due to intended owner occupation. The sole displacement trigger that tenants of all landlord types experienced in more or less equal measure was structural upgrading, i.e., modernization and energy rehabilitation.Footnote7

Table 5. Displacement triggers experienced by all respondents, by landlord type (multiple responses per respondent possible).

Different displacement triggers not only occur with varying frequency among different landlord types; a comparison of our findings on displaced and nondisplaced movers reveals that they vary even more in terms of effect, depending on what kind of landlord executes these triggers. Whereas rent increases, for instance, occur frequently among all types of landlords, only 3.8% of all respondents in our sample who had rented their previous flat from a nonprofit landlord (compared to 7% of those who had rented from a profit-oriented landlord) actually mentioned rent increase as a reason for moving, presumably because this landlord type tends to raise rents more moderately. A similar picture emerges when it comes to structural upgrading: on average, structural upgrading leads less frequently to displacement among nonprofit landlords. Unlike profit-oriented landlords, state-owned housing companies and cooperatives seem more likely to carry out energy rehabilitation and modernization in a socially acceptable manner (Mjörnell et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, tenants of for-profit owners complain disproportionately often about a maintenance backlog (see ). This structural decay was a reason to move for almost 6% of these tenants, whereas the same was true for only three former tenants (<1%) former tenants of nonprofit landlords in our sample. There are various motives for poor or no maintenance of residential properties (cf. Christophers, Citation2022): (a) to maximize returns by minimizing costs; (b) to deliberately displace tenants in order to refurbish the property in question before selling or rerenting it at a high return; (c) unintended property neglect due to lack of financial resources or internal disputes among joint heirs. The fact that respondents who had rented their flat from a privately owned housing company or a private individual reported with above-average frequency the sale of their flat (see ) adds to this picture, because it probably reflects the “nature” of real estate as a commodity in this ownership group.

All in all, the findings of our survey show that nonprofit landlords are much less likely to displace their tenants than for-profit landlords and indicate that this is due to different property management strategies (cf. Hochstenbach, Citation2022). They also show, however, that housing cooperatives and public housing companies also raise rents from time to time and cannot escape being part of the housing market and its rationale. It is therefore worth taking a closer look at the strategies that underlie their performance in (tight) housing markets.

No Risk of Displacement With Nonprofit Landlord Types?

In the following we discuss why nonprofit landlord types are less inclined to displace their tenants. We do so by highlighting their management strategies and underlying principles as well as internal and external conditions (see ) in three categories that are key in both current housing policy and the international debate on reducing displacement and on strengthening housing commoning (cf. Kadi, Citation2022; Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016; Schipper & Latocha, Citation2018; Shaw, Citation2005; Stavrides, Citation2014; Vollmer & Kadi, Citation2018): (a) safeguarding affordability or moderate rent levels over the long term on the basis of different methods of decommodification; (b) ensuring a supply of affordable housing via ongoing construction and/or buyout and refurbishment of existing real estate; (c) enabling tenants to take part in shaping relevant management strategies in the pursuit of guaranteeing long-term affordability (a) and access (b), such as rent development, conditions for new housing construction, buyouts, sales/privatizations, and demolitions (tenant participation). provides an overview of the “performance” of different types of nonprofit landlords in all three categories and will be discussed in more detail in the following sections. Finally, substantiates this performance and summarizes our findings on the objectives and management strategies of nonprofit landlords that determine the risk for their tenants to be displaced.

Table 6. Classification of displacement avoidance in nonprofit landlord types.

Table 7. Objectives and management strategies of nonprofit landlord types.

State-Owned Housing Companies

The recent realignment of Berlin’s housing policy by the Housing Provision Act of 2016 has significantly reduced the risk of direct displacement for tenants of publicly owned housing companies. Rent increases by public housing companies are much lower today than in the 2000sFootnote8 (Gerhardt, Citation2020), amounting to a maximum of 1.39% per year since 2016 (the predefined maximum is 2%). Accordingly, in 2019 the average net rent for tenants of this landlord type (€6.22/m2) was slightly below market levels, and the price for rental flats on offer (€7.13/m2) was even 30% below market levels (Busse et al., Citation2020, pp. 11–13). In line with this, a recent study shows that stock-related expenditure of state-owned housing companies clearly focuses on maintenance rather than modernization measures (74% vs. 26%; Bernt & Holm, Citation2023). These companies, however, also use existing exemption regulations to raise below-average rent levels more sharply, leading critics to fear the "creeping" introduction of a lower rent limit of €6/m2 (Vollmer & Kadi, Citation2018, p. 254). This observation explains why the state-owned housing companies apparently are not fully able to prevent displacement either as our quantitative findings indicated (see ).

Public housing companies have recently expanded their housing stocks. Since the historical low of 258,000 public housing units in 2009 (Schneider, Citation2020), state-owned housing companies have built approximately 18,000 new flats and purchased another 52,000 flats.Footnote9 However, this increase falls far short of meeting the housing demand in medium and lower price segments. Moreover, the 25% share of publicly owned flats with rent and tenant control agreements fails sorely to live up to the 50% quota set out in the cooperation agreement between public housing companies and the state of Berlin (Busse et al., Citation2020, p. 51).

Although the recent Berlin housing act has introduced novel participation formats for tenants of public housing companies, they have hardly been used so far (Holm & Kuhnert, Citation2021). The newly created tenant councils, for instance, are not yet in a position to have a say in management strategies, let alone strategic corporate planning (Rohde, Citation2021). This also implies that so far no participatory rights have been established to prevent the renewed privatization of public housing (nor have any other measures been adopted to this end). Thus, municipalization alone is not enough when it comes to safeguarding housing decommodification in the long run (Metzger & Schipper, Citation2017, p. 184).

In terms of the underlying economic rationale, our analysis suggests that in their everyday management practice state-owned housing companies in Berlin continue to be guided by profitability criteria (cf. Vollmer & Kadi, Citation2018) and show a certain unwillingness and missing habit to align management goals and routines with public welfare (see also Holm, Citation2020). Accordingly, a public housing company representative stated:

The [cooperation agreement] means for us, of course, that we raise our rents less than would be legally possible. […] There is a gap opening up and this cannot go well forever. […] After all, we have to do business like any other company. […] This is not a […] ministry or something." (Interview 5: 8; 50)

Mature and Young Housing Cooperatives

Cooperatives are committed to their members and generally operate without the explicit intention of making a profit. Accordingly, the period between 2012 and 2018 saw only a moderate increase (2.53%/year) in the average rent of the housing stock of Berlin’s 20 largest housing cooperatives (Trautvetter, Citation2020, p. 34). In 2019, the average rent across Berlin’s cooperative housing stock was €5.70/m2 (BBU, Citation2021, p. 23), with new leases commanding an average of €7.23/m2 (IBB, Citation2020, p. 67). Nonetheless, housing cooperatives have partially exhausted the legal options for rent increases in the recent past—despite stable prices and low interest rates (Sethmann, Citation2017; Trautvetter, Citation2020, p. 34), which (similar to public housing) bears a certain displacement risk (see ). In addition, there are repeated cases of long-established cooperatives opting for demolition and new construction rather than maintenance of low-cost housing through repairs (Bratfisch, Citation2015; see also Metzger, Citation2021, pp. 203–205).

Cooperatives in Berlin are currently building no more than 660 new flats each year. What is more, expansion strategies of cooperatives—as far as they are pursued—are oriented to their members’ interests, as explained by a representative of a large traditional cooperative:

“The cooperative has been striving to expand its stock for many years. According to our charter, the purpose of the cooperative is to promote its members primarily by providing good, safe and socially responsible housing at appropriate prices.” (31: 5)

Member participation is much more vital in young cooperatives. In traditional cooperatives, economic decisions (e.g., on new construction, demolition, modernization, board salaries) are not usually legitimized democratically (Die Genossenschafter*innen, 2021, p. 52; Metzger, Citation2021). That said, management strategies in Berlin’s traditional cooperatives are meeting with increased resistance: “Cooperative from below” speaks out against the restriction of members’ rights; "Not in our name” opposed the rejection of the (meanwhile disestablished) Berlin rent cap by cooperative boards; “The Cooperative Members,” a recently established initiative, criticizes, for example, uncooperative boards and uncritical supervisory boards (Die Genossenschafter*innen 2021, pp. 54–56).

As in state-owned housing companies, we observe a yield-oriented and member committed rationale underlying the everyday management strategies of many mature cooperatives in Berlin, a phenomenon that is reflected in their membership in the Berlin-Brandenburg Association of Housing Companies (BBU). This key business association of large profit- and nonprofit-oriented landlords is likewise criticized for influencing the policy of its members. In addition, the prevailing solidarity principle basically equates to the principle of member obligation. This is illustrated by the low commitment to expand the housing stock and the opposition of many mature housing cooperatives in Berlin to recent policy initiatives such as the tying of new (subsidized) construction to rent control, as this quotation from a cooperative representative underlines:

Now […] the Senate is obliging me to offer so and so many flats for €6.50. In return, of course, I get a loan at a low interest rate, but the interest advantage is so small that I generate deficits with these flats, which everyone else who lives there has to compensate. […] This contradicts the cooperative’s solidarity principle that actually everyone pays the same on average. (Interview 2: 55)

Many young cooperatives are characterized by the ideal of the self-determined, democratic collective and a notion of solidarity that extends beyond their members. The latent dissent between traditional and young cooperatives has been anchored institutionally by the founding of the Alliance of Young Cooperatives as a "counter-movement to the commercial orientation of the BBU" (Die Genossenschafter*innen, 2021, p. 51), which 35 cooperatives have joined since 2017. Their management strategies are designed accordingly: cost rents, diverse rental models for the inclusion of disadvantaged social groups, and openness to new approaches to housing policy regulations (even at the expense of autonomy with regard to the management of existing housing). The outcome is a wide range of novel cooperative positions in Berlin today: cooperatives that limit their members’ opportunity for codetermination and thus realize quotas for special needs groups, cooperatives that specialize in uneconomical property purchases to enable housing communities threatened by displacement to remain, and umbrella cooperatives that grant individual house projects a high degree of self-management.

Novel Shared Ownership Models

In the case of novel shared ownership models, specific legal constructs rule out direct displacement. The Mietshäuser Syndikat and land trusts guarantee the permanent decommodification of land and real estate by means of a divided ownership structure (house project and superordinate organization) that allows the individual organizations to veto property sell-offs. In other words, there is effectively no rent increase involved in this type of ownership. The ground rent of the land foundations under study is decoupled from speculative land price development and thus does not bear any displacement risk (see ). Thus, it rarely exceeds 4% of the land price, as the following quotation illustrates: “Does the project contain nonprofit elements? Do they have to renovate or build first, and maybe need to be relieved by a low ground rent at the beginning?” (Interview: 8: 40). Where possible, low-interest direct loans from private individuals are used to finance housing projects. The average rent of Berlin syndicate projects is €6.32/m2. Due to cost development dynamics for land, real estate and construction over the last 20 years, average rent levels differ significantly between older properties and new construction projects.

It is not surprising that in quantitative terms growth in novel shared ownership models is almost negligible, although the Mietshäuser Syndikat, trias Foundation, and Edith Maryon Foundation each launch around 10 new projects annually (Stiftung trias, Citation2020). In the sense of urban commoning, the models share a consensus to grow that strongly depends on the self-initiative of potential future tenants. However, the following quotation indicates that expansion is not regarded as a management principle inherent to the respective institutions (in this case, the Mietshäuser Syndikat), but rather is linked to the general vision of expanding urban commons: “It doesn’t even have to be our organization [that establishes new projects of shared housing projects]. If it would simply be copied, it would also be a kind of growth” (Interview 11: 74). A general lack of public support is certainly a major reason for the fact that novel shared ownership models are growing only very modestly. It is even more difficult for these organizations to participate in the formats for land allocation and the recent housing subsidies introduced in Berlin, such as tendering procedures that allocate land depending on the quality of the project concerned rather than the highest bidder. In contrast, tendering procedures in other German and European cities are designed more simply (Granath Hansson, Citation2019, p. 107). As a result, households with a high level of education are the primary beneficiaries of novel shared homeownership models.

Participation in the syndicate model differs greatly from that of public housing companies or housing cooperatives. And although trusts are generally considered a strictly hierarchical form of organization (BBSR, Citation2019, p. 55), this also holds true for the land trusts under scrutiny, because management of their individual housing projects lies exclusively with the residents.

Even more than most younger cooperatives, syndicate and land trust projects see themselves as urban commons (Rost, Citation2014). In many cases they define themselves as a response to the risk of displacement. This is primarily evident where precautions are taken to permanently prevent property resales (i.e., speculation) and to carry out new projects, as the following quotation of a land foundation representative illustrates:

It is very important to us […] that we prevent this [resales]. And that in the long term, the work, the commitment and also the sacrifice that flowed into the houses, remains in the nonprofit sector. And in a legally secure way. (Interview 6: 21).

Conclusion

Taking Berlin as an example, this article discussed the role of different landlord types with regard to displacement on the housing market and the possible contribution of nonprofit property owners and their real estate management and exploitation strategies for displacement prevention. Our analyses show that the risk of being displaced unsurprisingly depends on the type of landlord involved. Private landlords and private housing companies are those most likely to displace their renters. Rent increases, modernization, and nonmaintenance of residential property are key components of their housing management strategies and trigger displacement processes. Other characteristic, although less pronounced, strategies employed by profit-oriented landlords in contrast to nonprofits are, for example, the sale of houses or flats, construction noise and inspections, all of which lead to living disturbances. In addition, tenants who rented their flat from a private landlord were far more likely to incur a contract termination than renters of all other landlord types.

Rent increases and structural upgrading are also strategies applied by state-owned housing companies and cooperatives, but as a rule they are far less pronounced than those of the private real estate sector (see also Bernt & Holm, Citation2023). With reference to state-owned housing companies, this is due to the contractually agreed rent development rates below federal levels and a certain quota of flats with rent and tenant control, whereas all cooperative-like housing structures, despite their numerous variations, are obliged to act in the interests of their members. Mietshäuser Syndikat residents are even “landlords and tenants at the same time” (Interview 10: 4) and thus are best equipped to prevent displacement. In addition, younger shared homeownership models go a step further in this regard: they are dedicated to the idea of solidarity and housing commoning in the broader sense. Hence, the three discussed types of nonprofit owners can certainly be said to have a displacement-reducing function. Nevertheless, their potential in this respect has limits when it comes to their property management and development strategies, because they, too, (have to) respond to the social needs of their tenants but also to market mechanisms (cf. Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016). And the focus of Berlin’s housing policy on state-owned housing companies indicates a latent ignorance of shared ownership models in general, and the conditions of young cooperatives in particular.

Based on our findings, we propose to address the following housing policy issues for Berlin and other cities and regions that have comparable economic (advanced Western capitalism) and legal-administrative (cooperative welfarism) framework conditions. Given that rent increases, frequently in combination with modernization measures, are a prime displacement trigger for profit-oriented landlords, the discussion on the various forms of rent restriction tools (e.g., rent cap, restriction on scope for rent increase, limitation of ability to charge tenants for modernization of their flat) should—for the sake of market economy principles that rarely apply to the housing market anyway—be intensified rather than tamed (Krätke & Borst, Citation2000). Furthermore, the stated relevance of terminations by private landlords as a displacement trigger emphasizes the need to reinforce mechanisms to impede this practice. In this context, we see two issues in particular that call for further quantitative analysis: First, research should also address nonmoving persons in order to detect the extent to which they experience displacement triggers and/or suffer from a lock-in in their current house. Second, due to the highly diverse character of private landlords in terms of organization, number and quality of housing stock, motives, and management strategies, we see—at least in Germany—an urgent need to focus future studies on this landlord type.

Second, to further tame displacement processes, nonprofit landlords should be promoted more courageously—not only those longest in existence, but also younger cooperatives and novel shared homeownership types that bear the highest potential in terms of innovative housing management strategies. In contrast to the ownership-based real estate markets of many other European cities, Berlin has a comparatively large potential to expand nonprofit housing models due to its considerable share of state-owned housing and land, and the abundance of housing cooperatives (Granath Hansson, Citation2019, p. 116). To this end, existing housing subsidy programs should be opened up to cooperatives and other community-owned forms of home ownership and made accessible to broader sectors of society (cf. Hansen & Langergaard, Citation2017). Resolute political support for solidarity-based housing models could also prompt large established cooperatives to rediscover the original, solidarity-based cooperative idea. In Germany, reintroduction of the Non-profit Housing Act (Wohnungsgemeinnützigkeitsgesetz), which was abolished in 1989, would provide an additional impulse in this direction.

Third, it seems necessary for state-owned housing companies to strengthen political (and tenant) control to safeguard the goals of decommodification and long-term housing affordability, solidarity, and participation, regardless of political change. To achieve this, a number of approaches and measures are being discussed in Berlin and elsewhere, including constitutional provisions on housing, changes to the legal form of state-owned housing companies via transformation into public corporations (Holm & Kuhnert, Citation2021), and a deepening of tenant/member participation in public housing and cooperatives (cf. Vollmer, Citation2018). In line with this, member pressure in mature cooperatives and the inspiration of experimental cooperatives could strengthen displacement-reducing management strategies. To allow for more detailed assumptions on public housing companies and mature cooperatives, whose management strategies vary substantially, more (comparative) systematic research would be useful.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Corinna Hölzl

Corinna Hölzl is a postdoctoral researcher at the Geography Department of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Her research focuses on civil society activities, housing, urban commons, and multilevel governance. Since 2017 she has been studying the translocal mobilization of housing commons in the context of financialization processes as part of the research project "Housing as global urban commons. Strategies and networks for the translocal mobilization of nonprofit housing models” funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). Before, she worked at Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in Leipzig, and the Leibniz Institute for Research on Society and Space (IRS).

Henning Nuissl

Henning Nuissl is a professor of applied geography and town planning at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Before he joined HU in 2009, he worked with several other universities and research organizations, including the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in Leipzig, Technische Universität Berlin, Potsdam University, European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder), and the Leibniz Institute for Research on Society and Space (IRS). He studied spatial planning, sociology, geography, political science, and history in Hamburg and Heidelberg, and obtained his PhD in Cottbus. His major research interests include “sociospatial” patterns and processes in urban areas, land use change, suburbanization, and urban sprawl, as well as local and regional governance. He also enjoys reflecting on what he is doing and for whom this could be helpful (i.e., on the strengths and pitfalls of applied and/or transdisciplinary research).

Fabian Beran

Fabian Beran is a research associate at the Lab for Applied Geography and Town Planning at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. His research focuses on gentrification processes, displacement, and urban development.

Tim Kormeyer

Tim Kormeyer recently graduated from Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, where he received a master’s degree in urban geographies. He is particularly interested in gentrification and housing policy.

Notes

1 With the term “landlords” we refer to both women and men.

2 Contrary to tenant cooperatives, members of ownership cooperatives have the right to sell their flats under certain conditions (cf. Sørvoll & Bengtsson, Citation2018).

3 In addition, community land trusts (CLTs), which are currently experiencing strong international expansion, could be considered here. CLTs can be understood as nonprofit democratic community-led organizations that hold land and both develop and manage affordable homes for a place-based community (Ehlenz, Citation2018). However, CLTs are only about to emerge in Berlin. And for the sake of conceptual clarity, we do not include individual cohousing projects with varying legal/organizational status here because it is not possible to make a clear distinction between nonprofit and other forms of cohousing projects. Neither do we include organizations such as churches and charities as a fourth type of nonprofit landlord in our analysis, because their performance—at least in the German housing market—is frequently similar to that of private landlords.

4 After German reunification, Berlin had a public housing stock of 482,000 flats in the early 1990s. By 2009, the stock had decreased to 258,000 units.

5 We use quotations from the interviews to highlight key findings or arguments. Interviews are cited with reference to the consecutive interview numbering we used to organize our empirical corpus.

6 Respondents classified as displaced experienced displacement triggers significantly more often than those classified as not displaced (who also experienced numerous displacement triggers, but did not specify them as a reason for moving). Our sample is not large enough, however, to differentiate the occurrence of displacement triggers solely on the basis of the displaced respondent subsample, because the number of displaced movers from cooperatives and public housing companies is simply too small to make valid statements about displacement patterns for these landlord types. We therefore decided to use the entire sample (including nondisplaced respondents’ experience with displacement triggers) to analyze the occurrence of displacement triggers with different landlord types.

7 Those displaced often experienced multiple displacement triggers simultaneously. Further analysis reveals that rent increases correlate with building upgrades, housing disruption, and landlord pressure to move out. For a more detailed analysis of displacement triggers, see Beran and Nuissl (Citation2023).

8 Back then, spatially selective property management strategies were also common, increasing displacement pressure on existing tenants in inner-city locations (Uffer, Citation2011, pp. 147–149).

9 Many of these real estate purchases were made possible by exerting the communal right of first refusal. This strategy ceased to exist at the end of 2021 due to the resistance of powerful housing market players.

10 Numerous cooperatives reject ground leases, for example, because banks in Germany have so far refused to grant loans based on borrowed land (Granath Hansson, Citation2019, pp. 108–109) and ground lease contracts are generally associated with high interest rates and short terms.

References

- Amt für Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg. (2019). Statistischer Bericht. F I 2—4j/18. Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus im Land Berlin 2018. Potsdam.

- Atkinson, R. (2000). Measuring gentrification and displacement in Greater London. Urban Studies, 37(1), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098002339

- Baeten, G., Westin, S., Pull, E., & Molina, I. (2017). Pressure and violence: Housing renovation and displacement in Sweden. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(3), 631–651. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16676271

- Balmer, I., & Gerber, J.-D. (2018). Why are housing cooperatives successful? Insights from Swiss affordable housing policy. Housing Studies, 33(3), 361–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1344958

- Barenstein, J. D., Koch, P., Sanjines, D., Assandri, C., Matonte, C., Osorio, D., & Sarachu, G. (2022). Struggles for the decommodification of housing: The politics of housing cooperatives in Uruguay and Switzerland. Housing Studies, 37(6), 955–974. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.1966392

- Bates, L. K. (2022). Housing for people, not for profit: Models of community-led housing. Planning Theory & Practice, 23(2), 267–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2022.2057784

- BBSR. (2016). Wohnungs- und Immobilienmärkte in Deutschland 2016 (Vol. 12). Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR).

- BBSR (Ed.). (2019). Gemeinwohlorientierte Wohnungspolitik—Stiftungen und weitere gemeinwohlorientierte Akteure. Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR). https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/veroeffentlichungen/sonderveroeffentlichungen/2019/gemeinwohlorientierte-wohnungspolitik-dl.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2

- BBU. (2021). Jahresstatistik der Mitgliedsunternehmen des BBU 2020. BBU Verband Berlin-Brandenburgischer Wohnungsunternehmen e.V. https://bbu.de/system/files/publi-cations/jahresstatistik_bbu_2020_0.pdf

- Beran, F., & Nuissl, H. (2023). Assessing displacement in a tight housing market: Findings from Berlin. City, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2023.2180829

- Bernet, T. (2020). Ausstieg aus dem Spekulationskarussell. Wege zu einer gemeinwohlorientierten Wohnungswirtschaft. INDES, 9(2), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.13109/inde.2020.9.2.87

- Bernt, M., & Holm, A. (2023). Socializing housing cuts the rent. A brief study outlining the positive impacts of socializing Berlin’s housing stock. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. https://www.rosalux.de/fileadmin/rls_uploads/pdfs/Studien/Onl-Studie_2-23_Vergesellschaftung_engl.pdf

- Blau, E., Heindl, G., & Platzer, M. (2019). Architektur und Politik—Lernen vom Roten Wien—Debatte. In W. M. Schwarz, G. Spitaler, E. Wikidal, & Wien Museum (Eds.), Das rote Wien, 1919-1934 (pp. 158–165). Birkhäuser Verlag.

- Bratfisch, R. (2015). Genossenschaften. Idee auf Abwegen. MieterMagazin, 5. https://www.berliner-mieterverein.de/magazin/online/mm0515/051526.htm

- Busse, B., Diesenreiter, C., Kuhnert, J., & Vollmer, M. (2020). Bericht zur Kooperationsvereinbarung 2019. https://www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/wohnen/wohnraumversorgung/download/WVB-Bericht-KoopV2019.pdf

- Cabré, E., & Andrés, A. (2018). La Borda: A case study on the implementation of cooperative housing in Catalonia. International Journal of Housing Policy, 18(3), 412–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2017.1331591

- Christophers, B. (2022). Mind the rent gap: Blackstone, housing investment and the reordering of urban rent surfaces. Urban Studies, 59(4), 698–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211026466

- Clark, E. (2014). Good urban governance: Making rent gap theory not true. Geografiska Annaler: Series B Human Geography, 96(4), 392–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/geob.12060

- Cosh, G., & Cleeson, J. (2020). Housing in London 2020—The evidence base for the London Housing Strategy (122). Greater London Authority. https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/housing_in_london_2020.pdf

- Crome, B. (2007). Entwicklung und Situation der Wohnungsgenossenschaften in Deutschland. Informationen Zur Raumentwicklung, 4, 211–221.

- Czischke, D. (2018). Collaborative housing and housing providers: Towards an analytical framework of multi-stakeholder collaboration in housing co-production. International Journal of Housing Policy, 18(1), 55–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2017.1331593

- Davidson, M., & Lees, L. (2005). New-build ‘gentrification’ and London’s riverside renaissance. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 37(7), 1165–1190. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3739

- Die Genossenschafter*innen. (2021). Selbstverwaltet und solidarisch wohnen. https://www.rosalux.de/fileadmin/images/Dossiers/Wohnen/Selbstverwaltet-und-solidarisch-wohnen-web.pdf

- Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-survey-mode surveys: The tailored design method. Wiley & Sons.

- Ehlenz, M. M. (2018). Making home more affordable: Community land trusts adopting cooperative ownership models to expand affordable housing. Journal of Community Practice, 26(3), 283–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2018.1477082

- Elliott-Cooper, A., Hubbard, P., & Lees, L. ( 2020). Moving beyond marcuse: Gentrification, displacement and the violence of un-homing. Progress in Human Geography, 44(3), 492–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519830511

- Ferreri, M., & Vidal, L. (2022). Public-cooperative policy mechanisms for housing commons. International Journal of Housing Policy, 22(2), 149–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.1877888

- Freeman, L., & Braconi, F. (2004). Gentrification and displacement: New York City in the 1990s. Journal of the American Planning Association, 70(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360408976337

- Froschauer, U., & Lueger, M. (2003). Das qualitative Interview. UTB.

- GdW, B. deutscher W. I. e. V. (2014). Anbieterstruktur auf dem deutschen Wohnungsmarkt nach Zensus 2011. N.P.

- Gerhardt, S. (2020). Was geht? Berliner öffentliche Wohnungsunternehmen und die Neubaufrage. https://planwirtschaft.works/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/200302_LWU_Neubau_Berlin.pdf

- Granath Hansson, A. (2019). City strategies for affordable housing: The approaches of Berlin, Hamburg, Stockholm, and Gothenburg. International Journal of Housing Policy, 19(1), 95–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2017.1278581

- Grier, G., & Grier, G. (1980). Urban displacement: A reconnaissance. In S. B. Laska & D. Spain (Eds.), Back to the city: Issues in neighborhood renovation (pp. 252–268). Pergamon Press.

- Hansen, A. V., & Langergaard, L. L. (2017). Democracy and non-profit housing. The tensions of residents’ involvement in the Danish non-profit sector. Housing Studies, 32(8), 1085–1104. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1301398

- Hirsh, H., Eizenberg, E., & Jabareen, Y. (2020). A new conceptual framework for understanding displacement: Bridging the gaps in displacement literature between the Global South and the Global North. Journal of Planning Literature, 35(4), 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412220921514

- Hochstenbach, C. (2022). Landlord elites on the Dutch housing market: Private landlordism, class, and social inequality. Economic Geography, 98(4), 327–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2022.2030703

- Holm, A. (2020). 2. Berlin: Mehr Licht als Schatten. Wohnungspolitikunter Rot-Rot-Grün. In D. Rink & B. Egner (Eds.), Lokale Wohnungspolitik (pp. 43–64). Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG.

- Holm, A. (2023). Wohnen, Eigentum und Ungleichheit. In J. Degan, B. Emunds, L. Johrendt, T. Meireis, & C. Wustmans (Eds.), Die Wohnungsfrage—Eine Gerechtigkeitsfrage. (pp. 91–118). Metropolis-Verlag.

- Holm, A., & Kuhnert, J. (2021). Die nächsten Schritte zur sozialen Ausrichtung und Stärkung der landeseigenen Wohnungsunternehmen. Ein Diskussionsvorschlag.

- Hölzl, C. (2022). Translocal mobilization of housing commons. The example of the German Mietshäuser Syndikat. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 4, 759332. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2022.759332

- Horlitz, S. (2021). Strategien der Dekommodifzierung. In A. Holm & C. Laimer (Eds.), Gemeinschaftliches Wohnen und selbstorganisiertes Bauen (pp. 111–122). TU Wien Academic Press.

- Hyra, D. (2015). The back-to-the-city movement: Neighbourhood redevelopment and processes of politcial and cultural displacement. Urban Studies, 52(10), 1753–1773. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014539403

- IBB. (2020). IBB Wohnungsmarktbericht 2019. Investitionsbank Berlin. https://www.ibb.de/media/dokumente/publikationen/berliner-wohnungsmarkt/wohnungsbarometer/ibb_wohnungsmarktbarometer_2020.pdf

- IBB. (2022). IBB Wohnungsmarktbericht 2021. Investitionsbank Berlin. https://www.ibb.de/media/dokumente/publikationen/berliner-wohnungsmarkt/wohnungsmarktbericht/ibb-wohnungsmarktbericht-2022.pdf

- Kadi, J. (2022). Gentrifizierung und Verdrängung: Aktuelle theoretische, methodische und politische Herausforderungen (J. Glatter & M. Mießner (Eds.), pp. 237–254). transcript Verlag.

- Kearns, A., & Mason, P. (2013). Defining and measuring displacement: Is relocation from restructured neighbourhoods always unwelcome and disruptive? Housing Studies, 28(2), 177–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.767885

- Kitzmann, R. (2017). Private versus state-owned housing in Berlin: Changing provision of low-income households. Cities, 61, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.10.017

- Krätke, S., & Borst, R. (2000). Berlin: Metropole zwischen Boom und Krise. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-09364-0

- Madden, D., & Marcuse, P. (2016). In defense of housing. Verso.

- Marcuse, P. (1985). Gentrification, abandonment, and displacement. Connections, causes and policy responses in New York City. Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law, 28(1), 195–240.

- Martí-Costa, M., & Ferreri, M. (2021). Una política de vivienda municipal innovadora: El programa de apoyo a las cooperativas de cesión de uso en Barcelona. In Navarro Yáñez C. J. (Ed.), Los nuevos retos de las políticas urbanas: Innovación, gobernanza, servicios municipales y políticas sectoriales (pp. 87–102). Tirant.

- Metzger, J. (2021). Genossenschaften und die Wohnungsfrage. Westfälisches Dampfboot.

- Metzger, J., & Schipper, S. (2017). Postneoliberale Strategien für bezahlbaren Wohnraum?. In B. Schönig, J. Kadi, & S. Schipper (Eds.), Wohnraum für alle?! (pp. 178–212). transcript-Verlag.

- Mjörnell, K., Femenías, P., & Annadotter, K. (2019). Renovation strategies for multi-residential buildings from the record years in Sweden—Profit-driven or socioeconomically responsible? Sustainability, 11(24), 6988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246988

- Mullins, D., Milligan, V., & Nieboer, N. (2018). State directed hybridity?—The relationship between non-profit housing organizations and the state in three national contexts. Housing Studies, 33(4), 565–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1373747

- Newman, K., & Wyly, E. (2006). The right to stay put, revisited: Gentrification and resistance to displacement in New York city. Urban Studies, 43(1), 23–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500388710

- Rohde, M. (2021). Versuch einer erweiterten Mitsprache: Die Mieterräte als Element der Mieterpartizipation in den landeseigenen Wohnungsbaugesellschaften Berlins [Master thesis]. Humboldt-University of Berlin.

- Rost, S. (2014). Das Mietshäuser Syndikat. In S. Helfrich & Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung (Eds.), Commons: Für eine neue Politik jenseits von Markt und Staat (pp. 285–287). transcript Verlag.

- Sakizlioğlu, B. (2014). A comparative look at residents displacement experiences: The cases of Amsterdam and Istanbul [PhD dissertation]. Utrecht University.

- Schipper, S., & Latocha, T. (2018). Wie lässt sich Verdrängung verhindern? Die Rent-Gap-Theorie der Gentrifizierung und ihre Gültigkeitsbedingungen am Beispiel des Frankfurter Gallus. Sub\urban zeitschrift für kritische stadtforschung, 6(1), 51–76. https://doi.org/10.36900/suburban.v6i1.337

- Schneider, M. (2020). Ein Blick in die Bilanzen. Die Wohnungsbaugesellschaften in der Ära Wowereit und Müller. MieterEcho, 412, 8–9.

- Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt. (2014). Stadtentwicklungsplan Wohnen 2025. Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt.

- Sethmann, J. (2017). Selbsthilfe, Solidarität und Sicherheit—Wohnen in Genossenschaften. MieterMagazin, 11, 14–18.

- Shaw, K. (2005). Local limits to gentrifi cation: Implications for a new urban policy. In R. Atkinson & G. Bridge (Eds.), Gentrification in a global context: The new urban colonialism (pp. 168–184). Routledge.

- Slater, T. (2006). The eviction of critical perspectives from gentrification research. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 30(4), 737–757. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00689.x

- Sørvoll, J., & Bengtsson, B. (2018). The Pyrrhic victory of civil society housing? Co-operative housing in Sweden and Norway. International Journal of Housing Policy, 18(1), 124–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2016.1162078

- Statista. (2020). Tenure composition of Spanish housing in Community of Madrid in 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1185210/housing-tenure-in-spain-by-type-madrid/#statisticContainer

- Stavrides, S. (2014). Emerging common spaces as a challenge to the city of crisis. City, 18(4-5), 546–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2014.939476

- Stiftung Edith Maryon. (2020). Tätigkeitsbericht 2020. https://maryon.ch/v2/wp-content/uploads/SEM_JB_2020_web.pdf

- Stiftung trias. (2020). Tätigkeitsbericht 2020. https://www.stiftung-trias.de/fileadmin/media/downloads/2020_trias_taetigkeitsbericht.pdf

- Trautvetter, C. (2020). Wem gehört die Stadt? Analyse der Eigentümergruppen und ihrer Geschäftspraktiken auf dem Berliner Immobilienmarkt. https://www.wemgehoertdiestadt.de/documents/Studie_Wem_gehoert_die_Stadt_de.pdf

- Üblacker, J. (2023). Von der Vision zur Rendite? Fiktionale Erwartungen, wohnungswirtschaftliche Handlungsstrategien und Gentrification. In U. Altrock, R. Kunze, D. Kurth, H. Schmidt, & G. Schmitt (Eds.), Stadterneuerung und Spekulation (pp. 43–69). Springer.

- Uffer, S. (2011). The uneven development of Berlin’s housing provision [PhD thesis]. London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Urban Coop Berlin. (2018). Junge Genossenschaften in Berlin wollen bauen. https://www.urbancoopberlin.de/junge-genossenschaften-in-berlin-wollen-bauen/

- Valli, C. (2015). A sense of displacement: Long-time residents‘ feelings of displacement in gentrifying Bushwick, New York. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(6), 1191–1208. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12340

- Vollmer, L. (2018). Strategien gegen Gentrifizierung. Schmetterling Verlag.

- Vollmer, L., & Kadi, J. (2018). Wohnungspolitik in der Krise des Neoliberalismus in Berlin und Wien. PROKLA. Zeitschrift für kritische Sozialwissenschaft, 48(191), 247–264. https://doi.org/10.32387/prokla.v48i191.83

- Watt, P. (2018). 'This pain of moving, moving, moving’: Evictions, displacement and logics of expulsion in London. L'Année sociologique, 68 (1), 67–100. https://doi.org/10.3917/anso.181.0067

- Wijburg, G. 2021). The de-financialization of housing: Towards a research agenda. Housing Studies, 36(8), 1276–1293. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1762847