Abstract

How to shelter people who are experiencing homelessness is a pressing social problem. A substantive literature critiques the congregate shelter model that is often coupled with paternalistic service delivery, bringing the relationship of service delivery and the built environment into focus. The COVID-19 pandemic forced a fast overhaul of the delivery of crisis accommodation, and saw homeless shelters replaced with commercial hotels. We conducted a 12-month ethnography in a hotel for people experiencing homelessness located in South-East Queensland, Australia. We critically analyze the implications of operating a homelessness shelter in a hotel for service delivery and residents’ experiences of living in this repurposed built environment. Our findings highlight how homeless support practices were both enabled and constrained by the built environment. We identify a tension between residents’ appreciation of single occupancy rooms as fostering dignity and privacy, and their continued experience of hotel accommodation as (yet) another shelter. We discuss policy implications of using hotels as crisis accommodation within the context of a housing crisis.

Introduction

Congregate-style hostels or “shelters,” and historically alms and workhouses, have for centuries temporarily accommodated people experiencing homelessness (Tomkins, Citation2004). While there are variations in structure and operation, congregate shelters have a common set of characteristics, including shared facilities, dormitory-style sleeping arrangements, staff supervision, limited private space, and conditionality (Pable et al., Citation2022). Shelters are also characterized by time-limited provision, and this ranges from single-night stays to several months at a time. The short timeframes are premised on the idea that homelessness is a crisis, and that those accommodated require short-term support (Pable et al., Citation2022; Parsell, Citation2023). Despite their prevalence, scholars have repeatedly demonstrated the negative impact of the congregate shelter model on residents’ privacy, dignity, and safety (Busch-Geertsema & Sahlin, Citation2007; McMordie, Citation2021; Pable et al., Citation2022).

In many countries, stay-at-home orders and social distancing measures enforced to address the COVID-19 pandemic created challenges for the congregate shelter model (Colburn et al., Citation2022; Parsell et al., Citation2023; Robinson et al., Citation2022). By virtue of sharing sleep, bathroom, and toilet facilities, people residing in congregate shelters were constrained in their ability to comply with mandatory isolation, nor could they effectively protect themselves from the virus (Parsell et al., Citation2023). Many congregate shelters shut down—some never reopened. In their place, commercial hotels were used to temporarily shelter people experiencing homelessness. Many jurisdictions used hotels that were empty or underutilized due to limited tourism from closure of state and national borders, which motivated hotel owners to repurpose their hotels for the use of people experiencing homelessness (Parsell et al., Citation2023). Although not unprecedented (Sullivan & Burke, Citation2014), the use of hotels as a response to homelessness was significantly expanded during COVID-19 in Australia (Parsell et al., Citation2023), the United States (Colburn et al., Citation2022; Padgett et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2022), Canada (Government of Canada, Citation2020), and the United Kingdom (Lewer et al., Citation2020).

An emerging body of literature demonstrates that residents accommodated in hotels experienced improved privacy compared to congregate shelters or unsheltered homelessness, as hotels afforded them dignity and rest (Alexander et al., Citation2023; Fleming et al., Citation2022; Padgett et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2022). Hotels likewise reduced the risk of COVID-19 transmission and enabled better self-management of chronic conditions (Alexander et al., Citation2023). These benefits are primarily attributed to the built environment, especially the privacy allowed by single-occupancy, quality rooms, and access to ensuite bathroom facilities. Taking the promising evidence on the beneficial potential of the built environment associated with hotels to accommodate people who are homeless as a point of departure, we bring the implications for service delivery into focus.

We aim to contribute knowledge on the possibilities for and constraints of innovative service delivery associated with repurposing commercial hotels as crisis accommodation beyond the COVID-19 public health response. To achieve this, we examine a service delivery model implemented in an Australian capital city that explicitly sought to leverage the benefits of single room occupancy and non-congregate facilities within the hotel environment to transform service delivery and advance individuals’ housing outcomes. In doing so, we address the following research questions: (a) how is homelessness service delivery enacted within the built environment of a hotel compared to known limitations of congregate shelters and (b) how do service providers and residents experience practicing and living in this new form of homelessness accommodation? We contextualize our findings within the housing crisis currently unfolding in Australia (Pawson et al., Citation2022) and internationally (Airgood-Obrycki et al., Citation2023; Delclós & Vidal, Citation2021), marked by rising rents, low social housing stock, and a growing number of people experiencing homelessness. Drawing on ethnographic data, we reflect on the potential role that hotels can play in housing policy and practice aimed at ending homelessness within the contemporary housing landscape marked by increasing unaffordability.

Crisis Accommodation, Built Environment, and Homelessness Service Delivery

Challenges Built Into Congregate Crisis Accommodation

Congregate shelters have historically been one of the primary models used to accommodate people experiencing homelessness. The intention is to provide shelter for a short period of time rather than a long-term housing solution. However, the congregate-style shelter model has received sustained critique, not least due to the limitations inherent in the built environment of shelters and the implications for service delivery.

While providing shelter can improve health outcomes compared to unsheltered homelessness (Roncarati et al., Citation2018), the congregate model has been widely criticized for its negative impact on individual agency, autonomy, well-being, and safety (Hoolachan, Citation2022; Watts & Blenkinsopp, Citation2022). Residents in congregate-style shelters often share amenities such as showers or kitchens (Pable et al., Citation2022), and often sleep among many others in dormitories, sometimes with only partitions to provide a sense of privacy or to stop other people from entering one’s personal space (Busch-Geertsema, Citation2019; Busch-Geertsema & Sahlin, Citation2007).

The absence of privacy in congregate shelters, and the ensuing lack of dignity, puts strain on residents’ sense of self and mental well-being. For example, the poor built environment of some congregate-style shelters, including issues such as pest infestations and worn-down, outdated living spaces, affect feelings of self-worth (Moffa et al., Citation2019). Large numbers of residents present in open spaces together can create a sense of “chaotic” living, further having a detrimental impact on well-being (Kerman et al., Citation2019). Living alongside many people in shared quarters can also exacerbate mental ill-health or even retraumatize residents who feel like they are not living in a safe place (Robinson et al., Citation2022).

Shared spatial arrangements limit people’s sense of safety and control over their sleeping or living area (Busch-Geertsema & Sahlin, Citation2007; Watts & Blenkinsopp, Citation2022). People residing in congregate shelters report having their possessions stolen and/or conflict with other residents that is exacerbated by forced proximity (Wusinich et al., Citation2019). Indeed, research documents that many people experiencing homelessness will elect not to stay at congregate shelters because of the risk of violence (Donley & Wright, Citation2012; McMordie, Citation2021; Parsell, Citation2023; Wusinich et al., Citation2019). The experience of violence or the threat of violence in congregate shelters impacts on residents’ mental health, including feeling constantly on edge and hypervigilant to potential attacks (McMordie, Citation2021).

Built Environment and Homelessness Service Delivery

As well as the threats to dignity, mental health, and safety, the built environment of congregate shelters has implications for service delivery. Stuart’s (Citation2016) study from Los Angeles found that mega-shelters worked to change people to address what was assumed to cause their homelessness. The shelters worked in concert with police, whereby people experiencing unsheltered homelessness had the “choice” of either a criminal justice response or paternalist care in shelters that sought to alter their behaviors (Stuart, Citation2016). Although shelters are primarily driven by pragmatism, aiming to support as many people as possible, the paternalism that emerges from managing large numbers of individuals in shared spaces also provides opportunities to influence and modify their behavior. This phenomenon is exemplified in Stuart’s (Citation2016) study. Indeed, the physical design of congregate shelters featuring open spaces that allow for surveillance is often coupled with rules aimed at producing compliance and/or behavioral change (Busch-Geertsema & Sahlin, Citation2007; Parsell et al., Citation2018). For example, traditional shelter models commonly deploy paternalistic rules, such as enforcing a curfew at night to control undesirable behavior. Yet curfews significantly restrict residents’ autonomy over how they use their time, including limiting job prospects (Robinson et al., Citation2022). Some congregate models also lock residents out of their rooms during the day, forcing residents to spend most of their day in open spaces of the shelters or on the streets (Busch-Geertsema & Sahlin, Citation2007; McMordie, Citation2021; Pable et al., Citation2022). Lockouts allow staff to check rooms for prohibited items, infestations, and other hygiene concerns; in other words, lockouts are a means to monitor residents’ compliance with shelter rules. Furthermore, residents have limited opportunities to decide when they would like to engage with staff due to the open spaces they must traverse or participate in—whether that involves socializing, eating, or sleeping. The open layout of the built environment grants workers greater control over how these spaces are utilized, the types of engagement and case management that can occur, and the timing of such interactions. Additionally, staff can closely monitor residents’ behavior and interactions, which can be documented in case notes (Lyon-Callo, Citation2008). For instance, in dormitories where doors cannot be locked or are absent altogether, staff can easily observe people while they sleep for safety and monitoring purposes. This heightened visibility provides staff with more insight into residents’ behaviors, preferences, and living arrangements, enabling them to tailor individual support or, conversely, use evidence of non-compliance. Notably, these dynamics differ in spaces that afford residents more privacy, allowing greater autonomy in disclosing personal information about their behavior and experiences. Non-compliance can incur penalties, including exit from the facility (Lyon-Callo, Citation2008).

From Shelters to Hotels: Opportunities for Change

The use of commercial hotels during the pandemic has provided important evidence challenging the return to and unrevised continuation of the congregate-style shelter model and its underlying paternalistic logic. Residents who had moved into a hotel from either congregate or unsheltered settings during COVID-19 reported having a newfound space to relax, without the stress of finding a place to sleep or sharing rooms with strangers (Robinson et al., Citation2022). Similarly, having a room to lock provided a sense of safety and security of possessions (Padgett et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2022). Such security and stability meant residents’ stress levels decreased, while the quality of the rooms restored a sense of dignity (Padgett et al., Citation2022). For residents accommodated in hotels who were previously used to being locked out during the day, sleeping rough or seeking shelter that was reallocated from day to day, the guarantee of a bed in a hotel created stability to pursue other goals, such as employment (Robinson et al., Citation2022). Importantly, many residents felt ontologically secure enough to pause and plan for the future, giving them a sense of autonomy and hope (Colburn et al., Citation2022; Padgett et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2022).

Although most research initially praised hotels as an alternative to traditional congregate shelters, recent studies have revealed some drawbacks. For example, Savino et al. (Citation2024) found that hotel living can limit individual agency, and on-site security can have both positive and negative effects. This emerging body of literature thus foregrounds the significant benefits of hotel-style crisis accommodation models for enabling resident dignity, safety, and autonomy. However, less is currently known about how the vastly different built environment of hotels compared to congregate shelters presents opportunities and challenges for service delivery practices. We therefore expand on these existing studies to bring the built environment–service delivery nexus into greater focus, exploring perceptions, practices, and experiences of attempting to change service delivery within a hotel that was repurposed to accommodate people who are unhoused. We call this hotel the “Homeless Hotel.”

Conceptual Framework

The Homeless Hotel under study was primarily conceived of as a site for experimentation and innovation given that the evidence base for how to deliver services while repurposing commercial hotels, as crisis accommodation is only in its emergence. As such, we approach the Homeless Hotel, in Rhodes and Lancaster’s terms (2019), as an evidence-making intervention. Developed in the context of health, evidence-making interventions are local knowledge-making practices focusing on how evidence, intervention, and context coincide to drive or constrain practice innovation.

In terms of evidence, the Homeless Hotel draws on social work approaches that focus on the strengths, rather than the deficits, of individuals. Strength-based approaches acknowledge that people are best placed to identify their own needs, develop reasonable and valued goals to strive for, and utilize the supports they need to progress toward their goals (Brun & Rapp, Citation2001). In the case of the Homeless Hotel, this implies a shift away from paternalistic models in which shelter residents are subject to strict surveillance and behavior management policies toward a resident-led approach to how services are delivered.

Situating the Homeless Hotel’s service delivery conceptually within a strength-based approach to social work cannot assume a linear progression from evidence toward implementation into a given context; the relationship between evidence, context, and intervention is necessarily dynamic (Rhodes & Lancaster, Citation2019). The context for any intervention matters insofar as it shapes what kind of practices are considered worth doing and how these practices can be done. There are two key factors for consideration of context that inform our analysis: (a) the built environment of the Homeless Hotel and (b) the local housing market. Throughout this paper we trace how the spatial configuration of the Homeless Hotel enables or limits possibilities for a resident-led approach to service delivery. We discuss the Australian housing context marked by unaffordability and low vacancies in affordable housing as a contextual factor that creates tensions within the resident-led approach and discuss how this tension has the potential to undermine the innovative nature of the Homeless Hotel intervention.

Materials and Methods

Research Context and Setting

As part of the public health response to COVID-19, an Australian state government closed three congregate shelters and made a commercial hotel located in its capital city available to temporarily accommodate up to 64 unhoused residents at any one time. At the time of this research, the hotel was leased in its entirety by the state government and used exclusively for people experiencing homelessness. Operated by a not-for-profit organization, the Homeless Hotel represents an experimental approach to tackling homelessness with the primary goal of facilitating sustainable access to housing and improving people’s life outcomes.

The Homeless Hotel Model

The Homeless Hotel distinguishes itself from other crisis accommodation facilities by offering private, single-occupancy rooms of a four-star hotel standard. Each room has a self-contained bathroom and toilet. The hotel rooms do not have kitchens or independent cooking facilities. Residents are provided with one meal per day as part of their stay, along with weekly laundering of bedding. Residents have access to communal washing machines, microwaves, and sandwich presses. Additionally, there is an onsite coffee shop offering coffee, snacks, and pre-made meals that residents can purchase. Residents pay 25% of their income as rent. Most residents receive federal government unemployment benefits, which at the time of research were significantly below the income poverty line (Stambe & Marston, Citation2022).

Health and social care organizations provide services on site, including primary and mental health care, drug and alcohol support, and disability employment services. State housing authority staff members visit the Homeless Hotel weekly to assess housing needs and facilitate access to social housing and so-called “housing diversionary products.” The not-for-profit organization that runs the Homeless Hotel deploys one service provider to every 10 residents; this is similar to the ratio the organization achieved in the congregate shelter they operated pre-pandemic. Although the ratio is the same, the Homeless Hotel practice model differs significantly, as we demonstrate below.

Resident conduct is governed by rooming agreements outlining expectations, such as adherence to the harm minimization approach to alcohol and substance use, participation in case management for housing outcomes, compliance with room inspections, and building safety rules. There is no curfew, and security is on site 24/7. Interactions between residents in their rooms is discouraged, and residents are not permitted to receive external visitors, with the exception of external support services. Breaches of the rooming agreement are addressed through a system of warnings, with repeated breaches leading to a “focus period” requiring engagement with service providers and completion of set tasks, such as cleaning the room or putting in an application with the statutory housing provider. Failure to comply with the agreement or posing a danger to staff or other residents can result in residents being required to leave the Homeless Hotel.

The Homeless Hotel Residents

Within its 64 single rooms, the Homeless Hotel has accommodated 276 individuals on 294 occasions between May 1 2021 and June 9 2022. Among these residents, 73% stayed at the Homeless Hotel once, while 26% returned for multiple stays. The pathways leading to the Homeless Hotel varied: 92% were referred by other homelessness agencies or through internal transfers from the congregate shelter operated by the same organization. In contrast, a smaller proportion self-referred (3%), were referred by other agencies (3%), or arrived from domestic and family violence refuges, correctional facilities, or hospitals (2%).

Of the 276 accommodated individuals, 73% were male, and 27% were female (note that non-binary gender identification was not captured in the data). Twenty-eight percent identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, while 72% were non-Indigenous. The high proportion of Indigenous people reflects their over-representation in Australia’s homelessness population (Pawson et al., Citation2022). Reflecting Australian norms for adult homeless accommodation, residents must be aged 25 or over to stay at the Homeless Hotel. According to administrative data, 18% of residents were aged 25 to 34; 34% were aged 35 to 44; 35% were aged 45 to 54; and 13% were aged 55 and above.

Upon arrival at the Homeless Hotel, 72% were experiencing homelessness according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (Citation2012) definition, which includes inadequate and insecure accommodation in addition to unsheltered homelessness. For many residents, enduring homelessness and housing instability was a reality: 49% had no permanent address for up to a month before entering the Homeless Hotel, and 16% had been without a permanent address for an extended period. The Homeless Hotel, therefore, was designed to support people with long-term experience of homelessness and unstable housing.

Study Design, Recruitment, and Sample

We conducted a 12-month focused ethnography (Knoblauch, Citation2005), from November 2021 to November 2022, combining observations of service delivery and interviews with service providers and residents at the Homeless Hotel. In doing so, we aimed to explore the relationships between the built environment and the model and practices of service delivery. Ethnographic methods were employed to understand—through in-depth interviews—the new model of homelessness service provision as an ideal, and—through overt participant observations—the dynamic practices and experiences of the model in situ.

We conducted interviews with current or former residents (n = 20) and service providers (n = 16). We sought to recruit any service provider working at the Homeless Hotel, regardless of their specific role. Of the service providers interviewed, only one was new to working with people experiencing homelessness; the rest had been working in this space prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nine of the service providers identified as female. Out of the 20 residents that were interviewed, the majority moved into the Homeless Hotel from an unsheltered situation, two came from hospital, and two came from prison after serving their full sentence. Nine of the residents had lived in a shelter previously. The shortest length of stay at interview was approximately 1 month, and the longest was 12 months. Six of the residents identified as female. One resident identified as trans and another as gender diverse. Four of the residents identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. Two of the residents were non-Australian citizens (Italian, and New Zealander). Their ages ranged from 25 to 63 years.

After ethical approval (see Human Research Ethics Committee ID 2021/HE001763), all participants, including service providers and residents, were approached for recruitment on site during fieldwork. To ensure consent was informed and voluntarily given, we proactively reassured residents that they were free not to participate in the research, and that non-participation would have no bearing on their service use. Indeed, service providers had no knowledge of whether residents participated in the study or not. Service providers were also reassured that their decision to participate would not affect the relationship with their employer. Resident participants received a $40 voucher in recognition of their contribution to the study.

The first author conducted participant observations approximately one day per week for 12 months, for a total of approximately 252 hours. The fieldwork was fluid, with the first author conducting observations, writing notes, interviewing, and shadowing service providers whenever possible and where consent was provided. Therefore, there could be a 10-minute observation, followed by an interview, followed by two hours of shadowing, followed by general chats with residents while they had a cigarette, and so forth. The first author’s deep presence in the hotel enabled them to gain access and build relationships as a researcher with both service providers and residents. The first author would take quiet times in the hotel as an opportunity to write fieldnotes, or would write them as soon as possible once fieldwork was completed for the day. Fieldnotes contained descriptions of observations and verbatim quotes as much as possible.

Observations usually occurred during work hours between 08:00 and 17:00, but at times extended well into the evening. Interviews and observations were conducted concurrently and iteratively, as each data source informed the other. We developed and refined the interview schedule based on insights emerging from observations, and we continually honed our observation focus based on learnings from in-depth interviews. For example, the built environment of the hotel, what it meant for resident dignity, and what it meant for practice innovation featured prominently in early interviews and observations. As the research progressed, we paid particular attention to the spatial configuration of the hotel, and the implications for resident experience and service provider practices.

All in-depth interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts and fieldnotes were thematically analyzed. We followed Padgett’s (Citation2017) approach to inductive thematic analysis. Moreover, Padgett’s work on rigor in qualitative research was important for methodological triangulation. We used the data from participant observations and in-depth interviews not to derive a singular and objective truth about the Homeless Hotel, but rather to gain a comprehensive understanding accounting for tensions between ideal and situated practices. In addition to drawing on triangulation to enhance rigor, interviewing diverse participants enabled us to examine practice and experience from multiple angles. In the results below, we distinguish between data presented from residents and from service providers. To add nuance, we have provided gender and length of stay at the time of interview for residents. All names provided are pseudonyms.

Results

Our research employed ethnography to examine how homelessness service delivery operates within the built environment of a hotel, focusing on the experiences of both staff and residents. We compared this approach to the known limitations of congregate shelters. Our findings reveal a significant contrast: unlike the oft-crowded conditions in congregate models, the single-room occupancy and the quality of the hotel surroundings contribute to a more restful and dignified experience for residents. The built environment plays a crucial role in the renewed service delivery efforts of the organization. However, despite intentional efforts to reshape services to a resident-led approach and the benefits of using hotels to accommodate those who have been unsheltered, the broader context of the housing market introduces complexities. Our findings reveal opportunities and tensions within the capacity of innovative hotel models to adequately meet the housing needs of people who are homeless.

Finding Rest and Dignity

The self-contained rooms are a significant feature that demonstrates a shift away from the paternalistic model of congregate shelters toward assuming people experiencing homelessness deserve autonomy and control over their environment. As in previous research (see Colburn et al., Citation2022; Padgett et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2022), service providers and residents alike identified improved facilities, especially removing the need to share bathrooms, as significant enablers of dignity, respect, and privacy. As one service provider remarked:

Eight times out of 10, when I bring them to their room, there’s a tear. Yeah, they get quite teary. Because it is showing respect in a nice room. And they come in, it’s beautifully made up and there’s a little toiletry pack there. They weren’t expecting something like that. (Sophia, Female, Service provider)

Similar to the participants in Robinson et al.’s (Citation2022) study, the residents in our study described being able to “relax and recuperate” in comparison not just to what a congregate model was like, but also to the exhaustion stemming from sleeping rough. With rest came the ability to regroup and strategize. Just as in Padgett et al. (Citation2022)’s results where residents viewed hotels as a “platform for stability” (p. 251), our residents explained that the relaxed rules at the Homeless Hotel provided them with a greater sense of autonomy and agency, empowering them to drive their lives in their preferred direction:

… if I was still on the streets, I would have taken the first opportunity …. And then, whatever happens from there, happens from there. At least here, you can actually a little bit pick and choose-y, like what you want, which is good. Because usually when you’re desperate, you make desperate decisions. (Steve, Male, Resident for 2 months)

Here, single rooms are a significant resource enabling privacy and respite from other residents:

People who aren’t very good at cleaning the toilet bowl after themselves, something as simple as that that may, if someone’s relapsed and they’re coming down, and something like that can be such a trigger for them. But if they’ve got their own toilet, they don’t have to worry about it. (Tracey, Female, Service provider)

Working from, I think, a perspective of giving them a safe environment [for using drugs] and putting boundaries up and having your boundaries and stuff with the workers and whatnot, and what is allowed and acceptable, it gives them a thing to take a look at themselves a bit more and identify what it is that they really want, need, how they want their life to be. (Stacey, Female, Service provider)

Despite the harm minimization approach taken by the service providers, during the research, we heard from a resident about another resident who had overdosed and passed away while living at the Homeless Hotel:

He’s whacked off his head on Lyrica [pregabalin] … And then the next day that’s when I found him dead in his room. And I just woke up that morning and I knew he was dead. And I said to security, “I just need to check on him.” And that’s when I found him. (Joseph, Male, Former resident for 8 months)

During fieldwork, we witnessed mixed reactions from residents to the harm minimization practices at the Homeless Hotel. For some, the harm minimization approach was experienced as a welcome relief from congregate models in which even personal drug use on the premises could result in an immediate exit from the shelter. As one resident remembered:

It was me first or second week of actually living [at the Homeless Hotel], they did a room inspection … there was actually an uncapped syringe on me floor … they’re like, “there’s an uncapped syringe on your floor. … Get it and put it in the box.” I thought, “Fuck, I’m going to be kicked out for that.” And yeah, they never. So, eight months later I’m still in here. (Tiran, Male, Resident for 8 months)

As alluded to in these quotes, navigating the tensions emerging from affordances of single room occupancy requires attention to the relationship of built environment and situated service delivery. Service providers at the management level of the Homeless Hotel recognized this:

Sometimes the property describes the model, or prescribes it rather. (Oscar, Male, Service provider)

The language we’re using now is all about, this is your safe space, this is home, this is what you make it. (Derreck, Male, Service provider)

Crafting a Resident-Led Service Delivery in a Different Built Environment

Beyond spatial innovation, the Homeless Hotel also calls for and represents an opportunity for experimentation with service delivery practice. Single room occupancy speaks to a broader set of assumptions tied to the rationale for moving away from congregate shelter models toward accommodation that is fit for delivering targeted support services that recognize the autonomy of residents.

When the Homeless Hotel first opened, the service providers struggled with the change in the built environment, and what this meant for their service delivery practice. For example, the service providers initially were stationed in the hotel foyer in such a way that residents had to walk past them to enter or leave the building. Although the service providers themselves wanted greater separation between them and the residents, management expressed a desire for service providers to be out from behind the desks and moving around the foyer talking to residents. The tacit assumption here was that service providers should be able to see and approach the residents; the associated assumption is that residents must be amenable to being watched and approached on the service providers’ terms as they go about their day. Recognizing these inherent paternalistic assumptions that align with the congregate model of large, shared spaces, and not with autonomous living, management eventually removed the service providers’ desks from the foyer. The space where they were previously stationed was repurposed as a communal resident space, although this space, like other communal spaces, was rarely used by residents. Indeed, our observations saw most residents keeping to themselves, supporting Bush-Geertsema and Sahlin’s (Citation2007) observations that forcing a community on a group of people who happen to live in the same building is both idealistic and unrealistic.

Over time, the service delivery model of the Homeless Hotel thus shifted as it adapted from the traditional surveillance-based approach characteristic of congregate shelter models to one that was premised on working with the built environment and mirroring what happens in the community (Busch-Geertsema & Sahlin, Citation2007; Hoolachan, Citation2022; Lyon-Callo, Citation2008). A service provider described the experimental model:

COVID gave us the opportunity to do something that needed to be done for a long time … hostel-style living has been outdated … it’s all just an experiment at the moment but on an operational level, and practically with the way that we work with the residents, we’re given a different opportunity to really look at the environments that they’ve come from, in hostel-style living, to having something that’s a lot more individual and a little bit more dignified to start their journey. (Elise, Female, Service provider)

You’re working alongside that person. One of my managers told me, she gave this analogy, you are driving in the car with your resident and you’re sitting next to them. You’re the GPS [global positioning system], you’re helping them, but they’re telling you where they want to go. (Tracey, Female, Service provider)

You’ve got to release some of your previous controls … people now have their own room, have their own bathroom … let go of that [model], that has dictated to be a controlled environment out of need and a parent–child relationship … you don’t necessarily have to have a staff member there in that space …. It means you need to engage in a different way. (Oscar, Male, Service provider)

Indeed, residents compared their experiences in congregate shelters and the Homeless Hotel. Specifically, many residents who had lived in congregate shelters previously spoke appreciatively of the relaxed rules at the Homeless Hotel and the experimental service delivery model more broadly. Some acknowledged the “resident-led” approach inscribed into their interactions with service providers at the Homeless Hotel:

[Service provider] said, “Have you seen any treatment for your gambling?” [I] said, “No, I just haven’t gambled.” She goes, “Oh, okay. Is it something you would want to do?” Yeah, so the conversation happened like that. It wasn’t forced, it was more as we’re talking now, “Hang on, I haven’t thought about that. Maybe I do need a bit of help,” which is good. At least you can realize that for yourself. (Peter, Male, Resident for 2 months)

In “God’s waiting room”

Supporting residents to access housing emerged as the clear and shared objective of all service providers. As this service provider expressed: “So, if we really distil this down to its most basic element, everything is about housing. Everything is about [the Homeless Hotel] being a transitionary facility in which the client achieves a housing outcome. That’s basically it” (Derreck, Male, Service provider).

While the ambition to secure housing for residents was clear, achieving this outcome proved challenging. Service providers consistently identified limited affordable housing supply as the primary obstacle:

Our biggest issue is finding people a place to live. (Darryn, Male, Service provider)

So even though they’re here, can’t afford anywhere else, they still have that requirement by [the government department of] Housing to try and find somewhere, which, as good as it is, it’s pointless because they can’t afford it … where do we put the people when there’s not enough houses? (Gloria, Female, Service Provider)

The use of the phrase “God’s waiting room” by this service provider is revealing in two ways. First, it reflects the dire housing situation, where acquiring housing feels almost like a matter of divine intervention. Second, it implies a challenging and often frustrating environment where people’s resilience and faith are constantly tested. These themes resonated throughout our research, where participants narrated the specific difficulties of operating a resident-led and housing-focused service within a systemic housing crisis.

To elaborate on these difficulties, service providers identified two central challenges in supporting residents during their wait for affordable housing. First, contractual obligations determined by the funding agreement stipulate a case management approach “for the duration of need” (Elise, Female, Service provider). However, the scope and nature of support was ill-defined where a resident’s primary need was simply affordable housing:

We have people here that are ready to go, but there’s just not the appropriate accommodation within the price bracket that they can afford … they’re here as part of a duration of need, but you could also put that to, “Well yeah, there’s nothing for me that I need.” (Elise, Female, Service provider)

I’ve got a couple of guys that are good to go, and they’ve been good to go for a while now. I had one guy that I sent him an appointment card and he didn’t show up and I says, “Where were you?” And he goes, “What’s the point of coming to these things anyway? I’ve got my housing application in, I’m looking for work, I’ve got my ID. What more left is there to discuss?” (Tracey, Female, Service provider)

The longer that the residents are here, the harder it gets. They start disengaging. They don’t see anything happening, so why would they want to keep talking to us? (Stacey, Female, Service provider)

Although residents’ rooming agreements at the Homeless Hotel were for the “duration of need,” service providers often indicated that 3 months’ stay was an expectation. Service providers did advise residents, however, that this period was not set in stone but would vary according to individual circumstances. The service providers emphasized that they would not exit someone simply because they have exceeded the 3-month period.

While many of the residents appreciated the quality of accommodation at the Homeless Hotel, and the ability to stay for their duration of need, it did not replace their desire for a home. Residents were all too aware of the housing crisis and the implications it had for their housing aspirations. Many of them spoke about the additional support they received with cleaning rooms, applications, referrals to other services, help with travel cards and having someone listen to them, yet the importance of finding a house took center stage:

Resident: But yeah, otherwise it’s good. But I don’t put enough into it, maybe, to get more out of it …

Interviewer: Do you reckon you need to show up more and meet your support worker? …

Resident: No. No, well, not really. It just feels like nothing gets done for me. I get stuff done, but it’s only now I’m getting stuff sent. But it’s still decision-making to do and, really, what I need is a house. (Lisa, Female, Resident for 9 months)

The daily grind, contractual realities, and limited housing as an exit pathway challenged the capacity of the Homeless Hotel to deliver a resident-led model of service provision. For some service providers, this triggered a behavioral approach that paternalistically sought to change residents. When residents remain in the hotel for long periods of time because of a lack of affordable housing to exit into, their behaviors are scrutinized. Moreover, the ideals that promote autonomy and capacity are no longer the focus.

Service provider: I gave him – I didn’t even ask anyone. I just went, “Nah, not putting up with that.” He’s taking up a bed for someone else. He doesn’t want to come down and participate.

Interviewer: So when you say “participate,” what were you wanting?

Service provider: Come down, have a case meeting with me, tell me what’s going on, how can I help you. (Julia, Female, Service provider)

The service provider elaborated the approach:

I sort of have a bit of a, not a rule with them, but I don’t know what you would call it. I give them three strikes before they upset me. And I’m annoyed, really. I’m not upset, but I’m annoyed you’ve wasted my time three times in a row. So, he knows that I’ll be snappy … “I’m not going to see you today because you’ve let me down and you’ve wasted my time repeatedly.” So, he’s been down every day, engaging, engaging with [other caseworker] as well. (Julia, Female, Service provider)

Discussion

This article has examined the built environment’s role in homelessness service delivery, offering nuanced insights into the affordances of two distinct accommodation models: congregate shelters and a hotel. Our analysis of recent experiences with the delivery of services at the Homeless Hotel reveals novel challenges emerging in this built environment. Findings raise fundamental concerns about how the problem of homelessness is approached. Specifically, we identify a tension between the important appreciation among residents of single occupancy rooms as enabling dignity and privacy, and their continued experience of hotel accommodation as (yet) another shelter. We make sense of this tension within the Australian sociopolitical and policy context marked by the absence of enough affordable housing, which reverts service delivery from the resident-led pursuit of housing outcomes to a focus on identifying and addressing resident deficits.

Our study found similar benefits of the built environment of hotel accommodation to those shown in previous studies of single-occupancy rooms in hotels during the pandemic as affording people spaces in which to live with dignity (Alexander et al., Citation2023; Colburn et al., Citation2022; Padgett et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2022). The accounts of residents in our study resonate with international studies that highlight the importance of single room occupancy in a hotel for enabling rest and recuperation, which creates the conditions for people to plan for their next steps and future (Colburn et al., Citation2022; Padgett et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2022). The shift from shared amenities to individual, self-contained rooms offers a sense of worth, respect, and privacy that is often absent in traditional congregate shelter settings (Kerman et al., Citation2019; Padgett et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2022). This shift in living conditions recognizes the inherent value of individuals and restores their dignity.

This present study extends beyond the focus on benefits associated with single-occupancy rooms, by adding to knowledge of the dynamic interplay between the built environment and service delivery. Using hotels as temporary shelters brings about a distinct set of complexities that we delved into. We recognize that the hotel under study was part of an initiative to establish faciliatory service delivery in a deliberate move away from the paternalistic approaches that are often coupled with congregate shelters (Busch-Geertsema, Citation2019; Lyon-Callo, Citation2008; Pable et al., Citation2022). The service delivery model intentionally allowed scope for experimentation and sought to leverage the built environment to reduce resident surveillance and behavior control, in turn promoting individual autonomy.

Our findings revealed how the Homeless Hotel service providers both embraced and grappled with the experimentation demanded by the spatial setup of the crisis accommodation. Resident-led approaches to housing support align well with the reduced opportunities to surveil and manage individual behaviors at the Homeless Hotel. Beyond benefits for a person’s privacy, rest, and dignity (Alexander et al., Citation2023; Fleming et al., Citation2022; Padgett et al., Citation2022; Robinson et al., Citation2022), single room occupancy also increased residents’ capacity to autonomously engage with services they deemed beneficial. Notwithstanding the diversity of supports on offer on site (e.g., drug and alcohol support, health care, and so on), across service providers and residents, there was agreement that the key aim that guided practices and goal setting was the transition into stable housing.

The key outcome of exiting the Homeless Hotel and entering housing, articulated by both residents and service providers, was constrained by a paucity of affordable and appropriate housing stock. This presented a formidable challenge to the pursuit of a resident-led service delivery model. Funded by the Department of Housing to produce housing outcomes, the Homeless Hotel faced pressure to adapt the service model. What can the intervention do, if housing outcomes are limited by the context of the contemporary housing market? Where the support work oriented toward housing was increasingly experienced as meaningless, service providers refocused their efforts on ‘engaging’ residents in self-work toward self-identified goals and housing readiness.

We argue that this has two effects. First, it creates scope within service delivery to continue practices, where otherwise passivity and waiting presented undesirable alternatives (see, e.g., Schweizer (Citation2008) on waiting as a historically devalued practice in Western societies). This is evident in the frustrations service providers expressed in labelling the Homeless Hotel “God’s waiting room.” Second, it shifts responsibility for (not) achieving housing outcomes back to residents. We do not presume that this was done strategically by the service providers, to avoid being blamed for falling short of outcome metrics or funding requirements. We posit that this is an inevitable adaptation of the service delivery model within the logics set by the context within which it is embedded.

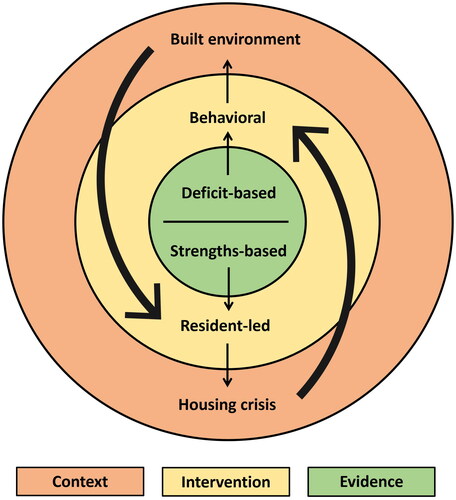

Based on the empirical analysis, we conceptualize the Homeless Hotel by integrating social work’s strength-based approach, the built environment (i.e., the Homeless Hotel as a space), and the social policy context (i.e., the Homeless Hotel as a housing intervention) (see ).

Figure 1. Our conceptualisation of the Homelss Hotel integrating practice, place, people and policy.

While the provision of single rooms embedded in a resident-led service delivery model was met with positive feedback from residents, the lack of affordable housing to exit into ultimately undermined the achievement of the Homeless Hotel’s primary objective: sustainable housing. As has been shown elsewhere, the drive to get people into housing, especially within a Housing First model which is demonstrated to be the ideal way forward in the homelessness sector in Australia and internationally, is severely constrained by policy and insufficient affordable housing stock, and instead can engender new forms of conditionality (Clarke et al., Citation2020). Although the Homeless Hotel did not strictly enforce a 3-month limit on stays, the rooming agreement that residents were required to sign stipulated that the duration of stay was 3 months. This agreed timeframe had two related consequences. First, it pressured service providers to churn residents through, contrary to the resident-led philosophy. Second, it meant that residents were unable to fully settle, conscious that their duration of stay was monitored and expected to be short term.

The positive aspects of single rooms and the autonomy-directed model are undeniable. However, their effectiveness at achieving positive housing outcomes is significantly compromised by the absence of accessible and affordable housing options for residents to transition into. This creates a paradoxical situation where service providers, aiming to empower residents, are forced to resort to restrictive measures due to the lack of alternative solutions. The focus shifts from addressing the systemic issue of housing shortage to managing individual residents within a constrained system. This not only undermines the intended purpose of the Homeless Hotel but also creates a sense of helplessness for service providers and residents alike. It is crucial to recognize that these challenges are not intrinsic to the model itself, but rather symptomatic of a larger systemic issue: the lack of affordable housing and the consequences this has for the lives people can live, their health, and society at large (Morris et al., Citation2023; Plage et al., Citation2023). While our findings support the use of single room occupancy, including within hotels as other research has also suggested (Colburn et al., Citation2022), our research also shows that single rooms cannot create innovative practice conditions that will lead to improved housing outcomes in the absence of housing market innovations. In other words, without effective housing policy to ensure enough affordable and public housing, hotels functions like a shelter by any other name.

While our examination is limited to a single hotel in Australia and therefore not generalizable, the subsequent government purchase of hotels to accommodate people experiencing homelessness, along with the model’s success in other jurisdictions (Robinson et al., Citation2022), suggests hotels could be a viable alternative to traditional congregate shelters. Further research into how these models continue to develop is warranted, including possible unintended consequences of single rooms, such as residents experiencing loneliness or isolation. This detailed study of a single hotel provided an opportunity to explore the daily practices of supporting this population in a hotel, potentially informing future policy development. Making sense of the Homeless Hotel as an evidence-making intervention, we contribute to the emergent evidence base on the repurposing of commercial hotels as crisis accommodation. Our findings need to be contextualized against the background of the housing market of an Australian capital city; however, housing affordability and rising homelessness are issues experienced in many countries, including in North America and Europe. While it is beyond the scope of our ethnographic study to derive hypotheses to be tested, we see valuable opportunities for larger studies using administrative and/or population datasets to produce generalizable insights on the impact of the hotel/resident-led model.

Conclusion

Our findings have implications for policy and the recent impetus on building “fit for purpose” shelters (see Cid et al., Citation2019; Pable et al., Citation2022) and taking the built environment and service delivery space seriously. Resonating with other critiques of aesthetic approaches to building shelters (Busch-Geertsema, Citation2019), we maintain that the built environment–service delivery nexus is fundamental to revolutionizing crisis accommodation, yet always within the understanding that a shelter/hotel is not a “real home.” Scholarship invested in better housing outcomes and improving the experiences of people supported through housing services must pay equal attention to the spaces in which such supports take place, how they are implemented, and the dynamics between built environment and service delivery. The built environment of the Homeless Hotel is a pivotal factor in restoring dignity, fostering autonomy, and facilitating resident-led service delivery. In Australia, governments have purchased hotels and student accommodation facilities to accommodate people experiencing homelessness; this mirrors similar approaches adopted in the United States (Colburn et al., Citation2022). The benefits of single rooms and resident-led practices notwithstanding, the capacity of this new model to meaningfully address a person’s housing needs is contingent upon addressing the underlying issue of housing affordability. Stating that more affordable housing is the primary issue that needs attention is hardly novel. However, our research contributes to the literature that shows the benefits of using hotels for short-term crisis accommodation, but the reality of the housing market turns these crisis accommodation facilities into, potentially, longer term accommodation because the “duration of need” is contingent on the broader housing market. Without addressing the limited housing available for people to access, the novelty of the hotel model is diluted, and our research instead found that service providers reverted to conditional approaches predicated on trying to change the behavior of residents.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial and in-kind contributions of the St Vincent de Paul Society.

Disclosure Statement

The research on which this article is based was conducted as part of a commissioned study on the supportive housing program in question. Data collection and an independent report were funded in part by the not-for-profit organization delivering the program. No additional form of support was provided from these organizations, and the lines of inquiry pursued in our analyses here were undertaken independently of the original study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rose-Marie Stambe

Rose-Marie Stambe’s area of expertise lies in ethnography, particularly with marginalized communities facing social and economic exclusion. Rose’s research investigates how policies, institutions, and wider systems shape the lives of marginalized individuals, informing strategies for greater social justice.

Stefanie Plage

Stefanie Plage’s expertise is in qualitative research methods, including longitudinal and visual methods. Her research interests span the sociology of emotions, disadvantage, and health and illness. Currently, her research seeks to understand and improve the interactions of families experiencing social disadvantage with the social and health care systems.

Cameron Parsell

Cameron Parsell’s work examines multiple forms of exclusion and social harms. His research focuses on the nature and experience of poverty, homelessness, and domestic and family violence. He is interested in understanding what societies do to respond to these problems, and what societies ought to do differently to address them.

Ella Kuskoff

Ella Kuskoff’s research focuses on social and policy responses to inequality and disadvantage, and how these responses might be changed to more effectively address social issues. Her particular areas of interest include domestic violence, gender, and homelessness.

Edwina Wagland

Edwina Wagland is the State Manager of Alcohol & Other Drugs, Domestic Violence, and Support Services at St Vincent de Paul Queensland.

References

- Airgood-Obrycki, W., Hermann, A., & Wedeen, S. (2023). “The rent eats first”: Rental housing unaffordability in the United States. Housing Policy Debate, 33(6), 1272–1292. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2021.2020866

- Alexander, K., Nordeck, C. D., Rosecrans, A., Harris, R., Collins, A., & Gryczynski, J. (2023). The effect of a non-congregate, integrated care shelter on health: A qualitative study. Public Health Nursing, 40(4), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.13197

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012). Information paper—A statistical definition of homelessness. Retrieved March 27, 2024, from https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Latestproducts/4922.0Main%20Features22012

- Brun, C., & Rapp, R. (2001). Strengths-based case management: Individuals’ perspectives on strengths and the case manager relationship. Social Work, 46(3), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/46.3.278

- Busch-Geertsema, V. (2019). A shelter is a shelter is a shelter response to “Zero flat. The design of a new type of apartment for chronically homeless people”. European Journal of Homelessness, 13(2), 93–94.

- Busch-Geertsema, V., & Sahlin, I. (2007). The role of hostels and temporary accommodation. European Journal of Homelessness, 1(1), 67–93.

- Cid, D., Pla, F., & Serrats, E. (2019). Zero flat: The design of a new type of apartment for chronically homeless people. European Journal of Homelessness, 13(2), 75–92.

- Clarke, A., Parsell, C., & Vorsina, M. (2020). The role of housing policy in perpetuating conditional forms of homelessness support in the era of housing first: Evidence from Australia. Housing Studies, 35(5), 954–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1642452

- Colburn, G., Fyall, R., McHugh, C., Moraras, P., Ewing, V., Thompson, S., Dean, T., & Argodale, A. (2022). The impact of hotels as non-congregate emergency shelters: An analysis of investments in hotels as emergency shelter in King County, WA during the COVID-19 pandemic. Housing Policy Debate, 32(6), 853–875. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2022.2075027

- Delclós, C., & Vidal, L. (2021). Beyond renovation: Addressing Europe’s long housing crisis in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. European Urban and Regional Studies, 28(4), 333–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764211043424

- Donley, A. M., & Wright, J. D. (2012). Safer outside: A qualitative exploration of homeless people’s resistance to homeless shelters. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice, 12(4), 288–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228932.2012.695645

- Fleming, M. D., Evans, J. L., Graham-Squire, D., Cawley, C., Kanzaria, H. K., Kushel, M. B., & Raven, M. C. (2022). Association of shelter-in-place hotels with health services use among people experiencing homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 5(7), e2223891. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.23891

- Fopp, R. (2009). Metaphors in homelessness discourse and research: Exploring “pathways”, “careers” and “safety nets”. Housing, Theory and Society, 26(4), 271–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090802476564

- Government of Canada. (2020). Reaching home: Canada’s homelessness strategy—COVID-19. Retrieved December 10, 2023, from https://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/homelessness-sans-abri/index-eng.html

- Hoolachan, J. (2022). Making home? Permitted and prohibited place-making in youth homeless accommodation. Housing Studies, 37(2), 212–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1836329

- Johnsen, S., & Teixeira, L. (2010). Staircases, elevators and cycles of change: ‘Housing First’ and other housing models for homeless people with complex support needs. Crisis.

- Kerman, N., Gran-Ruaz, S., Lawrence, M., & Sylvestre, J. (2019). Perceptions of service use among currently and formerly homeless adults with mental health problems. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(5), 777–783. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00382-z

- Knoblauch, H. (2005). Focused ethnography. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-6.3.20

- Lewer, D., Braithwaite, I., Bullock, M., Eyre, M. T., White, P. J., Aldridge, R. W., Story, A., & Hayward, A. C. (2020). COVID-19 among people experiencing homelessness in England: A modelling study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8(12), 1181–1191. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30396-9

- Lyon-Callo, V. (2008). Inequality, poverty, and neoliberal governance: Activist ethnography in the homeless sheltering industry. University of Toronto Press.

- McMordie, L. (2021). Avoidance strategies: Stress, appraisal and coping in hostel accommodation. Housing Studies, 36(3), 380–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1769036

- Moffa, M., Cronk, R., Fejfar, D., Dancausse, S., Padilla, L. A., & Bartram, J. (2019). A systematic scoping review of environmental health conditions and hygiene behaviors in homeless shelters. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 222(3), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.12.004

- Morris, A., Robinson, C., & Idle, J. (2023). Dire consequences: Waiting for social housing in three Australian states. Housing Studies, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2023.2266401

- Pable, J., Mclane, Y., & Trujillo, L. (2022). Homelessness and the built environment: Designing for unhoused persons. Routledge.

- Padgett, D. (2017). Qualitative methods in social work research. Sage.

- Padgett, D. K., Bond, L., & Wusinich, C. (2022). From the streets to a hotel: A qualitative study of the experiences of homeless persons in the pandemic era. Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness, 32(2), 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2021.2021362

- Parsell, C. (2023). A critical introduction to homelessness. Polity Press.

- Parsell, C., & Clarke, A. (2019). Agency in advanced liberal services: Grounding sociological knowledge in homeless people’s accounts. The British Journal of Sociology, 70(1), 356–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12346

- Parsell, C., Clarke, A., & Kuskoff, E. (2023). Understanding responses to homelessness during COVID-19: An examination of Australia. Housing Studies, 38(1), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1829564

- Parsell, C., Stambe, R., & Baxter, J. (2018). Rejecting wraparound support: An ethnographic study of social service provision. The British Journal of Social Work, 48(2), 302–320. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcx045

- Pawson, H., Clarke, A., Parsell, C., & Hartley, C. (2022). Australian homelessness monitor 2022. Launch Housing.

- Plage, S., Baker, K., Parsell, C., Stambe, R.-M., Kuskoff, E., & Mansuri, A. (2023). Staying safe, feeling welcome, being seen: How spatio-temporal configurations affect relations of care at an inclusive health and wellness centre. Health Expectations, 26(6), 2620–2629. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13858

- Rhodes, T., & Lancaster, K. (2019). Evidence-making interventions in health: A conceptual framing. Social Science & Medicine, 238, 112488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112488

- Robinson, L., Schlesinger, P., & Keene, D. E. (2022). “You have a place to rest your head in peace”: Use of hotels for adults experiencing homelessness using the COVID-19 pandemic. Housing Policy Debate, 32(6), 837–852. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2022.2113816

- Roncarati, J. S., Baggett, T. P., O’Connell, J. J., Hwang, S. W., Cook, E. F., Krieger, N., & Sorensen, G. (2018). Mortality among unsheltered homeless adults in Boston, Massachusetts 2000-2009. JAMA Internal Medicine, 178(9), 1242–1248. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2924

- Savino, R., Prince, J. D., Simon, L., Herman, D., Susser, E., & Padgett, D. (2024). From homelessness to hotel living during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2024.2308494

- Schweizer, H. (2008). On waiting. Routledge.

- Stambe, R. & Marston, G. (2022). Checking activation at the door: Rethinking the welfare-work nexus in light of Australia’s Covid-19 response. Social Policy and Society 22(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1474746421000944

- Stambe, R., Plage, S., Kuskoff, E., & Parsell, C. (2024). “There’s not much I can do about it”: Violence and control in marginal(ising) spaces. Journal of Social Distress & Homelessness, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2024.2308495

- Stuart, F. (2016). Down, out, and under arrest: Policing and everyday life on skid row. The University of Chicago Press.

- Sullivan, B. J., & Burke, J. (2014). Single room occupancy housing in New York City: The origins and dimensions of a crisis. CUNY Law Review, 113, 113–143.

- Tomkins, A. (2004). Almshouse versus workhouse: Residential welfare in 18th-century Oxford. Family & Community History, 7(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1179/fch.2004.7.1.006

- Wallace, B., Barber, K., & Pauly, B. (2018). Sheltering risks: Implementation of harm reduction in homeless shelters during an overdose emergency. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 53, 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.12.011

- Watts, B., & Blenkinsopp, J. (2022). Valuing control over one’s immediate living environment: How homelessness responses corrode capabilities. Housing, Theory and Society, 39(1), 98–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2020.1867236

- Wusinich, C., Bond, L., Nathanson, A., & Padgett, D. K. (2019). “If you’re gonna help me, help me”: Barriers to housing among unsheltered homeless adults. Evaluation and Program Planning, 76, 101673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2019.101673