ABSTRACT

Purpose

Transformative marketing (TM) has reached considerable attention of both academic and practitioner communities. Being defined as the “confluence of a firm’s marketing activities, concepts, metrics, strategies, and programs that are in response to marketplace changes and future trends” (Kumar 2018, 2), TM aims at fostering beneficial customer-solutions and providing competitive advantages for firms and their stakeholders. However, five notable research gaps persist within TM to date: First, inadequate consideration of B2B contexts despite being a uniquely disruptive market constellation. Second, a lack of empirical TM studies hindering substantial insights on generalization. Third, scarcity of contextual foundations such as the prototypical, yet highly transformative application context of mobility ecosystems. Fourth, absence of a holistic view capturing TM instruments, strategies, and success metrics. Fifth, unexamined aspects of the Resource-Based View (RBV) in TM enabling further insights into firm’s transformation readiness. A distinctive feature of this research is its deliberate focus on B2B mobility firms, a domain characterized by high levels of disruption yet surprisingly neglected in TM literature. By delving into this overlooked sector, we aim to address critical knowledge gaps and unravel the intricate dynamics of disruptive B2B mobility ecosystems. For this purpose, we firstly delineate the morphology of disruptive B2B mobility ecosystems, shedding light on their structure and components. Secondly, we aim to develop a robust frame for assessing the “transformation readiness” of B2B mobility companies, crucial for navigating disruptive landscapes effectively. Thirdly, we endeavor to identify and scrutinize the TM instruments deployed within B2B mobility, with a view to constructing a comprehensive typology of TM strategies tailored to this context. Finally, we aspire to establish metrics for measuring the success of TM initiatives within B2B mobility companies, providing valuable insights for practitioners and scholars alike.

Methodology/Approach

This work presents a comprehensive qualitative study involving 30 in-depth expert interviews conducted between July-September 2023 in Europe and the U.S. Capturing the perspectives of multiple firm types active in B2B mobility, as suppliers, technology firms or mobility service providers (MSPs), the study takes a deep look into the TM phenomena of this turbulent environment. In addition to 14 managers with leadership experience in marketing, strategy and sales, our study incorporates 11 distinguished professionals from management boards encompassing CEOs, CFOs or CDOs. Further, we engage 5 leaders specialized in innovation and digitalization. The findings are derived through a thematic analysis employing both structural and open coding techniques (Saldana, 2013, Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

Findings

Our study involves six major findings related to the questions defined. First, suppliers in B2B mobility have not yet transformed from a value-based toward an ecosystem-based acting and lack a customer-centric perspective (RQ1). Second, a company’s readiness for transformation is notably influenced by its commitment to design a market-oriented and integrated organization, its adoption of a transformative culture and its success to acquire software-oriented human capital (RQ2). Third, the transformative marketing (TM) instruments applied in B2B mobility markets relate to six thematic categories and are dominantly characterized by strategic levers – a facet, which has so far received limited theoretical and conceptual attention (RQ3). Fourth, there are four foundational TM strategies evident, namely dependent, progressive, reactive, and evasive approaches, distinguishable through their intensity and proactivity (RQ3). Fifth, the selection of TM success indicators remains largely independent from organizational types and management levels, with a primary focus on financial and profitability metrics (RQ4). And sixth, explaining the success measurement of TM in B2B mobility companies requires the consideration of a firm’s foundational TM strategy (RQ4).

Research Implications

Our research advances the theoretical understanding of B2B TM, lays the foundation for further generalizing research and theory-building and enhances the current B2B TM perception toward a more strategic perspective. Additionally, we seek to contribute to a greater consideration of B2B marketing in contexts of turbulent environments. We emphasize that the integration of TM with the Business Ecosystem (BES) and the Resource-Based View (RBV) increases further explanatory power of transformational phenomena. In terms of the BES, we show that the perception of a turbulent environment varies depending on company type and has a major influence on a firm’s transformation. In relation to the RBV, our results demonstrate that within the B2B TM context, a stronger focus should be placed on identifying supportive and hindering transformation resources. Thus we propose describing the gap between existing (positive and hindering) and required resources as the “transformative resource gap (TRG)” and suggest, that this construct has the potential to enhance the RBV perspective on TM.

Practical Implications

The study presented offers the practitioner community to more thoroughly examine B2B firms’ TM phenomena. Connecting TM with concepts of the BES and the Resource-Based View (RBV) enables a deeper understanding of strengths and risks related to organization’s market-related activities. Further, we underline threats resulting from a missing market- and customer-centric perspective and recommend validating market assumptions near customers to reduce misjudgments. Additionally, our findings assist in managing the proactivity and intensity of TM, suggesting ways for reaching a progressive TM strategy. Ultimately, we encourage companies to select success metrics in line with their chosen strategy.

Originality/Value/Contribution

Our research stands at the forefront of advancing the theoretical landscape of B2B TM by integrating two pivotal frameworks: the Business Ecosystem (BES) and the Resource-Based View (RBV). This integration is not merely incidental but strategically chosen to amplify our understanding of transformational phenomena within B2B contexts. By leveraging the RBV, we delve deep into the internal resources, capabilities, and competencies of B2B mobility BES, unraveling their unique strategic characteristics and sources of competitive advantage.

Introduction

Transformative marketing (TM) has caught the attention of both academic and practitioner communities. Since its seminal consideration by Kumar in 2018, numerous researchers helped to advance its conceptualization. Being defined as the “confluence of a firm’s marketing activities, concepts, metrics, strategies, and programs that are in response to marketplace changes and future trends” (Kumar Citation2018, 2), TM aims at fostering beneficial customer-solutions and providing competitive advantages for firms and their stakeholders. Important contributions have been made to introduce TM as a new marketing paradigm (Kumar Citation2018). This included seminally addressing core variables in the context of TM actives, including important triggers, forces, as well as outcome variables (Kumar Citation2018). Further, scholars delineated the concept from similar or sub-approaches as transformative social marketing (Lefebvre and French Citation2012), transformative green marketing (Polonsky Citation2011), transformative advertising (Gurrieri, Tuncay Zayer, and Coleman Citation2022), and transformative branding (Spry et al. Citation2021). On the example of the COVID-19 crisis and related lockdowns, TM is also conceptually studied in conjunction with the Marketing Mix and B2B contexts (Lim Citation2023).

While these contributions provide an important foundation, further exploration of TM phenomena is needed for several reasons. First, TM to date does not reflect the unique importance of the B2B sector. The scarcity seems especially surprising when considering the high financial power of this context. An inclusion of B2B firms would also be highly relevant as they are particularly subject to dynamic change due to their unique value-chain embeddedness and multistep value creation. Here, we reference their “forward-backward integration” in the supply chain describing complex forces resulting from up- and downstream delivery structures (Strobel, Kuhn, and Meyer-Waarden Citation2023). The bullwhip effect (Scarpin et al. Citation2022), oligopolistic markets with dependencies (Lilien Citation2016), and complicated supply streams (Lilien and Grewal Citation2012) are just a few B2B phenomena that result from this position’s fragility. The lack of B2B in TM can be further underlined by a search in the Scopus database (considering title, abstract and keywords) using the term “transformative marketing” along with “B2B” or “business-to-business,” resulting in one single result (Lim Citation2023). Second, we address the necessity for empirical studies in the TM field. Previous contributions primarily focused on conceptual research, while empirical contributions remain scarce. This also offers various empirical research avenues for B2B TM (Lim Citation2023; Strobel and Meyer-Waarden Citation2023). Third, a distinctive feature of this research is its deliberate focus on B2B mobility ecosystems, a prototypical example for a disruptive environment which is characterized by high levels of disruption yet surprisingly neglected in TM literature. By delving into this overlooked sector, we aim to address critical knowledge gaps and unravel the intricate dynamics of disruptive B2B mobility ecosystems. The Business Ecosystem (BES) concept in general describes the embedding of firms in their market context (Moore Citation1993). We argue that the conceptual linkage allows to analyze TM phenomena systematically considering their transformational environment. The mobility BES as an application context is of highest relevance as dynamic variabilities range from new players, key trends like e-mobility and autonomous driving to new software or service business models. Further, is has been understudied in TM so far (Strobel and Meyer-Waarden Citation2023). Rather, studies deal with IT and Electronics (Elia et al. Citation2020; Li, Voorneveld, and de Koster Citation2022), Fast-moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) (e.g., Aime, Berger-Remy, and Laporte Citation2022; Kennedy and McColl Citation2012) or Finance (Elia et al. Citation2020; Li, Voorneveld, and de Koster Citation2022). Fourth, publications address single instruments of TM such as personalization (Kumar Citation2018), the use of non-human agents (Aime, Berger-Remy, and Laporte Citation2022), internet-based sales channel strategies (Varadarajan and Yadav Citation2009), customer engagement (Petersen et al. Citation2022) or similar. However, unexamined, analogous to Kumar’s definition, is the confluence in terms of a complex chain of effects impacting the overall success of TM. This also includes the decision about meaningful success indicators. Fifth, research shows that the Resource-Based View (RBV) (Barney Citation1991; Wernerfelt Citation1984) plays a key role in transformational activities (e.g., Erevelles, Fukawa, and Swayne Citation2016; Homburg and Wielgos Citation2022). However, most TM manuscripts following the RBV focus on enabling transformational resources. The combined consideration of resources that enable and those that hinder TM remains unexamined (Strobel and Meyer-Waarden Citation2023). Thus we propose describing the gap between existing (positive and hindering) resources and required resources as the “transformative resource gap (TRG).” We suggest that this construct has the potential to enhance the RBV perspective on TM. In essence, the integration of the RBV into our research not only enhances the theoretical robustness of our study but also empowers us to uncover deeper insights into the mechanisms driving transformational phenomena within B2B mobility BES. By elucidating the interplay between internal resources, external environments, and transformational strategies, our research contributes to advancing scholarly understanding and practical applications in the realm of B2B TM.

In sum, based on the gaps described this paper qualitatively studies B2B TM in disruptive BES from the RBV-lens on the example of the mobility sector. With its contribution, our research stands at the forefront of advancing the theoretical landscape of B2B TM by integrating two pivotal frameworks: the BES (Moore Citation1993) and the RBV (Barney Citation1991; Wernerfelt Citation1984). This integration is not merely incidental but strategically chosen to amplify our understanding of transformational phenomena within B2B contexts. Further, as B2B-organizations are highly impacted by dynamic transformations within their BES, the purpose of this work is to identify and support the development of B2B-specific TM strategies and success metrics in response to dynamic BES transformation. This will be achieved by answering the following research questions, which aim to provide a holistic understanding of TM activities in B2B mobility:

RQ1:

What characterizes the morphology of disruptive B2B mobility ecosystems?

RQ2:

How can we assess the”transformation readiness” of B2B mobility companies?

RQ3:

Which TM instruments are applied in B2B mobility, and can a typology of comprehensive TM strategies be derived from this?

RQ4:

How do we measure the success of TM in B2B mobility companies?

This article is structured as follows. First, we describe our methodological approach. Subsequently, we present our findings related to the four predefined research questions and offer a synthesis of the results. We then proceed with highlighting the manuscript’s theoretical and managerial contributions. Further, we discuss our outcomes and suggest potential future research angles. Finally, we provide a summary.

Materials and method

The data collection was conducted using a qualitative research methodology through in-depth interviews. A qualitative process was pursued as it allows for a deep comprehension of previously under-studied phenomena (Myers Citation2013). On one hand, this involves the specific explanation of TM activities on the example of the B2B mobility BES. On the other hand, it encompasses predicting TM success through suitable indicators. We consider these exploratory elements as essential for further theory building and quantification in TM research and as a prerequisite for its rigorous application. The interviews were conducted in a partially standardized manner. An interview guide was derived based on the research questions. It focused on (1) the disrupting BES as the context of TM activities, (2) firms’ enabling and hindering resources, which we refer to as the transformation readiness, as a prerequisite for designing a TM approach, (3) organizations’ instrumental TM strategies, and (4) relevant TM success metrics. The study sample comprised n = 30 in-depth expert interviews conducted between July-September 2023 in Europe and the U.S. Along with a limit of 2 interviews per company, the total number of included organizations equaled 28. A total of 41 people were approached, which corresponds to a response rate of 73%. Based on a rate of 33–53% on average for face-to-face interviews (Schröder Citation2016), the number achieved can be classified as remarkably high. This could possibly be attributed to the following aspects: First, subjects were approached via personal and professional networks. The project was explained using a one-pager and the anonymity of all test persons was assured. Second, we provided a comprehensive summary of the interview results as an incentive for study participation. Experts were approached via a purposive sampling method meaning that specific participants were selected nonrandomly based on pre-defined characteristics (Hibberts, Burke Johnson, and Hudson Citation2012). One criterium was the topic of company types reflecting the whole B2B mobility BES (= the population). Typical B2B mobility value chains comprise Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEM) and their suppliers. Depending on their position, the suppliers are referred to as direct Tier 1 suppliers or, in the case of upstream delivery, Tier 2 and beyond (Steward et al. Citation2019). Thus, our sample includes 4 experts from Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) acting in B2B structures (e.g., within commercial vehicle segments), 11 from upstream (Tier 1 and Tier 2) mobility suppliers, as well as 3 from mobility service providers. We also included 6 managers from tech firms active in mobility, as they are significantly disrupting the automotive market toward connected and software-defined vehicles. Furthermore, we employed 6 people from consultancy, mobility (research) agencies, startup acceleration firms and similar. We targeted experts with management experience in marketing, strategy, innovation, sales, and similar who were presumed to have high expertise in the research area. For instance, 14 interviews included marketing/strategy/sales managers, 11 members of management boards (CEOs, CFOs, CDOs), as well as 5 innovation/digitalization managers.

An experience threshold of 2 years in a relevant position was set as inclusion criterium. As we targeted highly experienced managers, the average total job experience equaled 22.7 years (min. 5, max 31 years). To reflect the population, we aimed for a roughly equal distribution of firm sizes resulting in 11 experts from startups/SMEs (<1,000 employees), 9 from majors (1,000–5,000 employees) and 10 from corporates (>5,000 employees). This also roughly applies for the experts’ management scopesFootnote1 (9 from lower, 8 from middle and 13 from upper management). outlines the sample characteristics described. Further, a consensed overview on our sample can be retrieved from the Appendix.

Table 1. Interviewee details (in time-chronological order).

For determining the interview number and the closure of the acquisition process, we followed the principle of data saturation. Decisions on saturation may be based on whether (1) the opportunity to collect new information decreases during data collection (Fusch and Ness Citation2015), (2) no new categories emerge during coding (Fusch and Ness Citation2015; Guest, Bunce, and Johnson Citation2006), or (3) there is enough data to replicate the study (Fusch and Ness Citation2015; O’Reilly and Parker Citation2012). While the third element holds limitations due to the large population and the qualitative nature of our study, the first two criteria helped us set a sample size of 30. The triangulation of methods (interviews, questionnaire, and secondary data), iterative data analysis, and the investigation of the phenomena from different angles further supported the reach of saturation (Fusch and Ness Citation2015). Here, the inclusion of further company types with TM expertise, as research agencies, consulting firms or learning institutes, may have been a potential lever of data saturation. In sum, engaging a meaningful number of subjects by addressing data saturation can be critical for ensuring content validity (Bowen Citation2008; Fusch and Ness Citation2015).

During data analysis, a transcription of the audio files (22 hours) was carried out first. The average duration per interview was 45 minutes (min 28., max 1 h 20 min.). Then, all audio files were prepared AI-based using HappyScribe, manually corrected and finalized. We conducted a thematic analysis of all resulting transcripts using the F4analysis software (version 3.4.1). Within this process, we first employed structural coding as it is specifically suitable for semi-structured interviews with multiple participants and in case of pre-defined research questions (Saldana Citation2013). Based on the four major research questions, we thus coded four overall categories: BES, transformation readiness (resources), TM instruments, and success metrics. Second, we inductively defined sub-dimensions using open coding (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). This procedure offers the advantage of high orientation to the text material to reflect the experts’ statements. We thus consider the technique as suitable for this exploratory research project. In addition, to avoid common method bias (MacKenzie and Podsakoff Citation2012), we analyzed descriptive company data using a short questionnaire that the experts answered after their interview. Further, we gathered secondary data from companies’ annual reports.

Results

RQ1: what characterizes the morphology of disruptive B2B mobility ecosystems?

In deriving a morphology of disruptive B2B mobility ecosystems, we have assigned a total of 339 interview excerpts to this main category. In particular, the thematic analysis reveals six characterization criteria shaping B2B BES in the mobility environment: (1) configuration (91 excerpts/27%), (2) technology (87 excerpts/26%), (3) customer dimension (62 excerpts/18%), (4) patterns of value creation (30 excerpts/9%), (5) dynamism and adaptation (27 excerpts/8%) and (6) co-evolution/co-opetition (6 excerpts/2%). The remaining excerpts, which could not be directly linked to one category, were categorized as “others” (36 excerpts/11%). A detailed overview of all analyses is included in the Appendix.

First, the aspect of configuration emerges as the most important sub-category of the disruptive B2B mobility BES. Interviewees emphasize critical elements as player structures and BES roles. In BES theory, those elements have already been discussed in various research articles (Cha Citation2020; Cobben et al. Citation2022; Jacobides, Cennamo, and Gawer Citation2018). Transferring the phenomena to mobility BESs, driven by technical changes, tech firms like Microsoft, Apple, or Amazon Web Services (AWS), formerly focusing on end-customer (B2C) business, enter the market. On the one hand, these disruptors bring a profound level of digital expertise and a keen understanding of customer requirements stemming from their B2C experience. On the other hand, their substantial financial strength is becoming a notable concern to conventional automotive companies. Illustratively, tech giant Apple achieved a turnover of 394 billion US dollars in 2022 surpassing the cumulative result of the world’s five largest automotive suppliers namely Bosch, Denso, Continental, ZF and Magna. This factor could prove to be a decisive competitive advantage in financing future mobility innovations. Simultaneously, the Asian region has substantial influence, particularly around electromobility solutions reflecting an orchestrating role in the BES. Finally, start-ups with innovative, often AI- and platform-based business models gain prominence. A marketing manager from an OEM underlines this shift, stating, “you suddenly have new competitors on board that you didn’t know at all before” (interviewee 3, paragraph 8). Second, the technology of the B2B mobility BES underlies profound disruption. Technical disruptions and their impact on entrepreneurial activity, including in the context of marketing, have already been researched in the literature (Huang and Rust Citation2021; Rust Citation2020). Within our interviews and the application context of B2B mobility BESs, key technologies, as electromobility, autonomous driving and the integration of artificial intelligence in vehicles are mentioned as triggers for substantial changes. These are accompanied by legislative shifts, the decoupling of hardware-software systems and a reduction in technical complexity. In essence, the technological disruption of B2B mobility is characterized by the transition from a product-driven to a software-driven approach. Third, disruption is evident in the customer dimension comprising changes in buying behavior as the rise of shared over individual mobility modes. Other behavioral shifts relate to expectations of intuitive software-operability, customer-centered user experience and over-the-air adaptability of functions. The element of market and customer orientation has already found favor in the marketing literature (Fader Citation2012; Kohli and Jaworski Citation1990; Narver and Slater Citation1990), the concept of customer centricity has even been discussed in connection with the BES (Scaringella and Radziwon Citation2018). Fourth, patterns of value creation, as generally highlighted in BES literature before (Eisenhardt and Galunic Citation2000), transform in B2B mobility. This concerns the change in profit structures, moving from hardware- to software-based value creation over the entire software product lifecycle. Further, changes in relevant business models and the emergence of new models as software as a service (SaaS) occur. Value creation processes are switching from a clear supply-chain toward an open value-creation network with a heightened focus on intercorporate partnerships. Fifth, BES dynamism and adaptation (Möller, Nenonen, and Storbacka Citation2020; Moore Citation1993) is a critical cluster and for instance highlights the general acceleration of the mobility BES: “The speed has simply increased” (interviewee 15, paragraph 72). Dynamic adaptation processes, often corresponding to orchestrating organizations assuming different BES roles, are explained. Sixth, the analysis underlines the category of co-evolution/co-opetition. Coopetition is characterized as the intricate interplay between the competition and collaboration among individual actors of an ecosystem (Moore Citation1993). Throughout the interviews, experts described this phenomenon as necessary to remain successful amidst volatile conditions and to generate benefits for the customers. An OEM representative notes: “I would much rather have a piece of the pie and have the customer be successful than try to be greedy and do things that are beyond my core capabilities and the customer isn’t successful. So we have a huge amount of coopetition” (interviewee 14, paragraph 80).

An examination of the findings by company type ()Footnote2 unveils significant variations in the perception of the disruptive B2B mobility BES across firm types. In particular, the ratio of technology orientation versus customer orientation (Fader Citation2012; Kohli and Jaworski Citation1990; Narver and Slater Citation1990) comes to light: OEMs, tech firms and mobility service providers (MPS) present a nearly balanced relationship, while suppliers exhibit an imbalanced perspective with a significant focus on technology and a diminished customer orientation. This imbalance may be rooted in historical technical lock-in effects. Previously, automotive markets were shaped by clear contractual value chains. In line with the transformation toward a complex BES involving coopetition phenomena, customer orientation may replace internal technology-centric perspectives as a critical success factor.

Further, reveals two distinct clusters of BES perceptions: First, B2B OEMs and suppliers represent similar profiles. Both are considered as traditional actors of the mobility market and face the challenge of conducting a successful transformation. Our analysis, however, suggests, that while OEMs have incorporated the customer perspective (21% of excerpts), suppliers still lack a customer perspective (9% of excerpts). Yet, including a customer-based perspective is considered a pivotal step in transforming toward a BES structure (Scaringella and Radziwon Citation2018). Second, technology firms and mobility service providers (MSPs), perceived as relatively new to the market, show comparable charts. Thus, our findings on RQ1 suggest the following conclusion:

Suppliers have not yet transformed from a value-based towards an ecosystem-based acting and lack a customer-centric perspective.

RQ2: how can we assess the “transformation readiness” of B2B mobility firms?

Organizational transformation readiness (syn. organizational change readiness (Lehman, Greener, and Simpson Citation2002) is linked to the anticipation, strategic planning and derivation of corporate visions and cultures in the context of corporate change (Thanitbenjasith, Areesophonpichet, and Boonprasert Citation2020; Trahant and Burke Citation1996). It is often used in connection with the topic of dynamic/strategic change capabilities (Schriber and Löwstedt Citation2020). We employ the concept of “transformation readiness” to reflect the overall assessment of an organization’s initial situation for change. In that respect, we suggest to not only employ enabling change capabilities but also hindering resources to explain a firm’s preparedness for change. Furthermore, the interviews show that the intensity of BES disruption has an impact on resource requirements and thus on transformation readiness. As an enhancement of the theoretical RBV perspective and to enable deeper insights into transformation readiness, we propose the adoption of a “transformative resource gap (TRG)” calculated as the difference between resource requirements resulting from the BES and the firm’s situation in terms of enabling and hindering resources.

In exploring the transformation readiness of B2B mobility firms, we have attributed 339 interview excerpts to this category. The thematic analysis reveals six subcategories being decisive for a B2B firm’s readiness to transform: (1) organization and processes (98 excerpts/41%), (2) corporate culture (83 excerpts/34%), (3) knowledge and human capital (68 excerpts/28%), (4) legacy (46 excerpts/19%), (5) equipment and infrastructure (17 excerpts/7%) and (6) financial resources (16 excerpts/7%). The remaining excerpts, which could not be linked to one category, were categorized as “others” (11 excerpts/5%). According to the RBV (Barney Citation1991; Wernerfelt Citation1984), we argue that these categories could help to shed light on the initial situation of companies in relation to their transformational activities.

First, the primary thematic cluster of excerpts revolves around organization and processes. Experts, for instance, emphasize the necessity to form small, heterogeneous, and autarchic teams. The need to consider the organizational elements in relation to increasing software focus is also addressed in the literature (Hoda, Noble, and Marshall Citation2013). The experts mention that independence from core business functions and related silo structures is essential, especially when establishing software units (e.g., interviewees 1, 4 and 11). The significance of functionally integrating software/services (horizontal perspective) and hardware (vertical perspective) is also highlighted. Second, the analysis points to corporate culture influencing transformation readiness. Enabling elements in terms of the TRG relate to variables including resilience, purpose, motivation, and culture that embraces failure. On the contrary, hindering elements comprise missing openness to transform, considerable risk aversion, or the lack of management attention as major factors. While the aspect of corporate culture (e.g. Schein Citation1985) has been researched for a long time, it is particularly crucial in the digital environment. An innovation manager states: “You have to give them [the employees] the opportunity to try things and experiment very quickly. Many large companies can’t do that. In other words, you need to be able to try things out with as little cost and therefore as little collateral damage as possible, so that if you realize that you have taken the wrong path, you can correct it quickly. That is very important overall in this digital environment” (interviewee 1, paragraph 36). Third, the presence of knowledge and human capital emerges as a factor of transformation readiness. Interviewees refer to capabilities in electromobility and software-defined vehicles. The transformation of resources is also characterized by a shift from traditional hardware engineers to an increased demand for software engineers. The importance of this element is also confirmed in comparison with the academic literature, where the topic of knowledge generation around software development is addressed (Samer and Lee Citation2000). Fourth, the analysis points to the legacy of a firm as major influence on transformation readiness. Enabling legacy elements mostly are prevalent in technology firms and relate to capabilities of agile software development, rapid development cycles, the decoupling of hard- and software, as well as a streamlined, customer-centric end-to-end processes. Here, too, the previously described importance of customer orientation comes to light (Fader Citation2012; Kohli and Jaworski Citation1990; Narver and Slater Citation1990). Hindering legacy-based elements are mostly found in established mobility firms and comprise a hardware-centric approach in line with vertical silo structures, traditional engineering capabilities and hardware infrastructure. Fifth, equipment and infrastructure influence transformation readiness. The shift toward software products raises the risk of empty production plants while, on the other hand, AI-based infrastructure is necessary to facilitate change. Sixth, financial resources are mentioned in 16 excerpts illustrating a necessary factor to enable innovation: “Implementing innovations, electrification, that costs a lot of money in our sector” (interviewee 2, paragraph 18). However, compared to other categories, the topic plays a subordinate role in the interviews. Thus, for the category of transformation readiness, our analysis suggests the following intermediate hypothesis:

A company’s readiness for transformation is notably influenced by its commitment to design a market-oriented and integrated organization, its adoption of a transformative culture and its success to acquire software-oriented human capital.

The impact of the RBV on TM and the specific contribution of the TRG phenomenon can be further illuminated. In the past, B2B mobility organizations predominantly had hierarchical and siloed structures. The corporate culture was risk-averse, and the emphasis was on hardware product development, with human capital primarily focused on traditional engineering. These resources and capabilities may impede the transition toward service- and software-oriented mobility. The disparity between the existing and necessary resources of mobility firms, known as TRG as an indicator for transformation readiness, thus affects the attainment of transformation goals, influencing TM success metrics.

We also analyze this category by company type (see no. 4). It stands out that OEMs are most concerned with their culture (59% of their excerpts compared to 34% on average for all company types) while MSPs and other firm types significantly analyze their organization and processes. Further, it is worth to look at the transformation readiness by management level, displayed in . The topic of organization and processes as well as corporate culture seems especially important for lower management levels while middle and upper levels rather tend to focus on knowledge, and legacy.

RQ3: which TM instruments are applied in B2B mobility, and can a typology of comprehensive TM strategies be derived from this?

In the following, we first analyze the identified TM instruments before discussing the results’ implications for the existence of a typology of comprehensive TM strategies. In terms of the instrumental configuration of TM in B2B mobility firms, we identify 510 relevant text passages within the transcripts. The passages deal with the following topics in relation to TM instruments applied: (1) strategic marketing instruments (185 excerpts/36%), (2) product-related instruments (116 excerpts/23%), (3) relationship-related instruments (53 excerpts/10%), (4) distribution-related instruments (50 excerpts/10%), (5) price-related instruments (47 excerpts/9%), (6) communication instruments (41 excerpts/8%). A further 18 excerpts (4%) fall into the “others” category.

First, strategic marketing instruments are the essential perspective of the TM approaches of B2B mobility BES. With 185 excerpts, these make up 36% of the text passages in this category. This underscores the necessity to expand research on B2B TM as previous work has focused on TM as part of the marketing mix and thus follows a more operational instead of strategic perception of the concept (see Lim Citation2023). Within our findings, the category predominantly addresses the following instruments: The analysis of the global market environment. The experts mention the importance of an anticipation of global developments with regard to digitalization, globalization, sustainability issues or political developments. The assessment of the relevant market, including its players, also plays a role. The target group of mobility and its changes are analyzed and segmented, because – according to the experts – a one size fits all approach is no longer appropriate. In addition, the topic of marketing organization and people as well as detailed marketing strategies and goals are explained. It is important that marketing strategy hardware and software are decoupled from each other and that specific marketing competencies are created in the digital environment. In addition, we assign market exit strategies from the automotive sector to the category of strategic marketing instruments. Overall, the explanations appear similar to literature in the field of strategic marketing, which also highlights the analysis of the global and specific market environment and the derivation of central marketing objectives (e.g. Homburg, Krohmer, and Kuester Citation2013). Second, product-related instruments are a substantial perspective. In addition to traditional elements of product policy, product-related instruments also include (software) innovation and branding. With 37% of their mentions, MSPs in particular deal with this category. One of the reasons given for this is that modern players have internalized a risk mind-set and manage innovation processes with the knowledge that only a small percentage of the solutions developed will be successful. However, if these are high-margin enough to cover other projects, this risk should be taken. In addition, it is recommended that portfolio management should be geared toward the life cycle of the respective solutions and that sufficient application programming interfaces (APIs) of digitalized products should be provided. Third, the aspect of relationship-related instruments targets the interaction with distinct types of stakeholders: public institutions and policy, direct and end-customers, competition, and partners. Although the academic world has long been dealing with the concept of strategic partnerships (Mohr and Spekman Citation1994), the B2B mobility experts interviewed consider them as a crucial element to strive in the disruptive and digitalizing B2B mobility environment. An innovation manager of an OEM notes: “I really feel that 20 or 30 years ago, (…) big companies, they could do everything at home. They could rely on internal tools, internal resources, an internal way of thinking, because they were the critical mass. But today, I really feel that questions and the issues are so complex that you can’t solve or find the great idea alone” (interviewee 26, paragraph 146). The aim of partnerships in BES is to acquire expertise (usually in the field of digital services and software), increase market power. In comparison with mergers and acquisitions (M&A), partnerships are also a good option due to their generally lower financial outlay. In conjunction with RQ2, resources such as an organizational structure with interfaces to external stakeholders and an open corporate culture could be levers for successful partnerships. Fourth, distribution-related instruments play a role in 50 excerpts. OEMs and MSPs have the highest attention in this category and describe their efforts to reduce complexity of multi-channel distribution through strengthening direct digital sales. Further, the setup of a B2B sales funnel management is recommended. Lastly, the topic of end-customer integration and skillsets related to consultative and value-based selling for software-based solutions are emphasized. Fifth, price-related levers focus on the willingness to pay of both direct (B2B) and end customers (B2B2C). Interviewees emphasize that novel issues are emerging, particularly with the topic of software and service as well as the trend toward sustainability, as the complexity of quantifiability is increasing. The focus of the category is on the development of scalable, software-based business models with recurring revenue streams. Similarly, researching the influence of software and services on the design of pricing strategies is also attracting attention in the academic world (Zhang Citation2020). Within our sample, all types of companies are concentrating on the development and pricing of so-called Anything as a Service (XaaS) models such as Software as a Service (SaaS) or Platform as a Service (PaaS). Designing a successful, scalable model is described as follows: “When can I really scale a business model successfully? Whenever I have a) the best talent and b) the power and ownership over the entire vertical value chain” (interviewee 10, paragraph 80). Sixth, communication instruments as part of B2B firms TM approach deal with the credible communication of an organization’s transformation toward both internal and external stakeholders. In the case of traditional players, the development of a common internal language within the organization and the external presentation to customers are particularly important. Technical companies, pursue a deeper look at the end customer needs underlining their need for higher customer-centricity (Fader Citation2012; Kohli and Jaworski Citation1990; Narver and Slater Citation1990). As one marketing manager emphasizes: “That’s why marketing communication is so crucial. And I have always been driven by the question of how we can use psychological aspects to support people, perhaps to achieve faster adaptation of technology? (…) Why do we perhaps also develop technology without first considering people’s needs? What problem does [our product] actually solve?” (interviewee 10, paragraph 40). In sum, our initial findings on TM instruments in B2B mobility suggest a first intermediate conclusion:

The transformative marketing (TM) instruments applied in B2B mobility BES relate to six thematic categories and are dominantly characterized by strategic levers – a facet, that has so far received limited theoretical and conceptual attention.

The findings are also underlined by an analysis of the results by company type, depicted in , and by management level, illustrated in attachment 5. It becomes clear that although there are several differences, the strongest leverage on average across firm types and hierarchy levels is clearly around strategic instruments.

As a second step in answering RQ3, we discuss the possibility of deriving a typology of comprehensive strategies from the results presented. As shows, the analyzed firm types similarly employ TM instruments from the six subject areas described, namely strategy, product, relationship, distribution, price, and communication. However, the interviews indicate that these instruments are used with varying degrees of proactivity and intensity as part of an overall approach. First, TM proactivity is based on the finding that some experts consider TM as an active management process (high proactivity) while others refer to instruments being applied based on the action of other BES players (low proactivity). The identified phenomenon of TM proactivity is closely related to the general theoretical framework of “strategic proactivity” (Aragon-Correa Citation1998; Sharma, Aragón-Correa, and Rueda-Manzanares Citation2007). Strategic proactivity is defined as “a firm’s tendency to initiate changes in its various strategic policies rather than to react to events” (Aragon-Correa Citation1998). Similarly, we suggest a definition of TM proactivity as “a firm’s tendency to initiate changes in its TM approach rather than to react to external events”. The phenomenon can be illustrated with the interview data from a CEO describing his TM approach as follows: “What do we have to do? Of course we follow our customers.” (Interviewee 24, paragraph 36). Further, a sales manager emphasizes that the instruments introduced highly depend on the OEM customer and at the same time admits: “We tend to see that the big former customers, Toyota and Honda, have somewhat overslept the topic of electrics and electromobility and purely electric vehicles.” (Interviewee 2, paragraph 26). This quote also illustrates the potential risks resulting from a lack of independent use of TM instruments resulting in a non-proactive TM strategy and lack of own BES intelligence. Similar to the concept of strategic proactivity, continuous outside-in and market intelligence is therefore also important for TM proactivity to ensure long-term leadership (Sharma, Aragón-Correa, and Rueda-Manzanares Citation2007).

Second, TM intensity is based on the finding, that while all company types are concentrating on instruments from the same overall categories, the number and integration of instruments applied varies. The identified phenomenon of TM intensity is closely related to the construct of “marketing intensity” (Markovitch, Huang, and Ye Citation2020; Palomino-Tamayo, Timana, and Cerviño Citation2020;Natalie Citation2010). Marketing intensity is defined as “The effort made by the company in marketing (…)” (Palomino-Tamayo, Timana, and Cerviño Citation2020). The effort is quantified by metrics as total marketing cost divided by total assets (Palomino-Tamayo, Timana, and Cerviño Citation2020) respectively SG&A (selling, general, and administrative) expenditures minus R&D cost divided by total assets (Natalie Citation2010). Building on this previous work and our findings, we suggest defining TM intensity as “the effort made by the company in transformative marketing “. However, TM effort according to our study refers to the scope of TM activities employed, regardless of their financial nature: On the one hand, we identify nine firms applying instruments from a total of three categories, such as strategic, price-related and relationship instruments (e.g., interviewee 9, 15). On the other hand, we find six organizations engaging four instrument categories (e.g., interviewee 7, 17) and nine organizations employing five instrumental sets (e.g., interviewee 8, 24). Further, our research reveals that six organizations adopt measures from six different instrumental groups (e.g., interviewee 1, 5). We argue that these differences can be interpreted as higher respectively lower intensities of a firm’s TM strategy. A high intensity would therefore correspond to a high degree of utilization in the context of a coherent and integrated TM application, while a low intensity would involve the use of fewer instrument categories. Based on variations in TM proactivity and intensity, we suggest four major TM strategies, namely dependent, progressive, reactive, and evasive approaches. We illustrate the suggested framework in and describe the particularities of each strategy in the following.

Reactive B2B TM is characterized by low TM proactivity and low intensity. Within the dataset of our study, expert number 9’s organization demonstrates a reactive strategy. This is visible, among other things, by the fact that activities are derived from the actions of the upstream OEM customer. We thus identify a low proactivity. Additionally, there is little use of TM activities and only instruments from the three areas of strategy, product (innovation) and relationship are adopted. Further, the contact person notes that there is no integrated, confluent TM strategy: “This means that the business models must subsequently match the architecture and technology strategy. In my opinion, this is still decoupled. Of course there is portfolio management and market and business models somewhere, but they are not coordinated.” (Interviewee 9, paragraph 44). Strategic implications for this cluster therefore include the holistic derivation of an integrated approach and the reduction of dependency on other BES players. Further, achieving greater independence, for example by entering partnerships for more market power or diversifying the product range could enable a higher proactivity. An end-customer-centric view in the sense of a B2B2C approach could also help to verify market premises more fundamentally and without distortion due to dependence on the direct organizational customer.

Evasive B2B TM is a strategic approach that involves the highly proactive but less intensive use of TM activities. The company of interviewee 29, a mobility supplier, provides an example of this foundational approach. The SME is proactively developing its market field strategy and positioning itself in a product niche of mobility solutions. In addition, it actively influences the perception of the end customer and therefore hopes to achieve a pull effect along the value chain: “We enable the end customer to know what is technologically possible. And that they then write their specs [specifications] to the primes [the original manufacturers] accordingly and we then see the products requested from us” (interviewee 29, paragraph 56). This phenomenon indicates a high degree of independence and proactivity. However, the scope of the TM instruments used in this organization is limited. Only few TM instruments from the categories of strategy, distribution and others are mentioned and it can be critically questioned whether the full opportunity of a comprehensive, confluent TM approach has been exhausted. Implications may point to constantly monitoring unique niche spaces selected within the BES, establishing sustainable differentiation possibilities, or strengthening the own market position through partnerships.

Dependent B2B TM approaches involves the highly intensive but less proactive use of TM activities and refer to a comprehensive and thorough utilization of TM. However, it is marked by a significant reliance on the approach adopted by other BES players. An example of a dependent strategy within our dataset can be found in interview 8. The expert, a marketing manager at a mobility supplier, emphasizes, that the firm mainly follows the direct OEM customers activities: “That’s a bit where we’re also looking at the moment, how is the market going or how global are our customers actually positioning themselves?” (Interviewee 8, paragraph 78). In the logic presented, this therefore relates to low proactivity. At the same time, however, the manager addresses a comprehensive program of TM instruments from five instrumental areas suggesting a high intensity. Detailed instruments include the analysis of customer price elasticity, sophisticated pricing models considering service components and benefit-based pricing. In summary, the advantage of this strategy is therefore, among other things, the supposedly lower cost of own ecosystem intelligence due to high reliance. However, there is a corresponding risk if the downstream organizations are not successful. Thus, strategic implications relate to increasing proactivity, which, analogously to the reactive strategy, could lie in the formation of partnerships or higher end customer focus.

Progressive B2B TM involves the highly intensive and proactive use of TM activities and signifies the extensive and comprehensive utilization of BES-derived marketing activities designed to proactively adapt to dynamic disruptions. An example of such a strategy can be identified in interview 5. The tech firm’s key elements include consequent customer-proximity and -interaction, e.g., through engagement activities ensuring a seamless customer experience. As the interviewed member of the organization’s management board emphasizes: “The first big priority we always see is customer centricity, i.e. playing the customer orientation end to end (…). And this goes hand in hand with a change in the business model (…)” (Interviewee 5, paragraph 66). Further, the expert describes how the company’s own activities are largely geared toward the needs of the changing BES. Additionally, he emphasizes that the formation of partnerships is essential for a high level of market control and thus high independency. Further, the activities are not filtered through the lens of an intervening company, leading to a high proactivity. Secondly, the interviewee uses TM instruments from all six distinct categories revealing a high intensity. Detailed measures here refer to the establishment of a marketing organization derived from market and customer needs as a strategic instrument. He also describes the need for software- and service-centricity. Further, the interviewee emphasizes product-related measures through active portfolio management and consequent divestment. In sum, the firm combines all six instrumental dimensions presented before in a holistic strategy. In summarizing our findings on RQ3, our second conclusion regarding comprehensive TM approaches in B2B mobility BESs is as follows:

There are four foundational TM strategies evident, namely dependent, progressive, reactive, and evasive approaches, distinguishable through their intensity and proactivity.

RQ4: how do we measure the success of TM in B2B mobility companies?

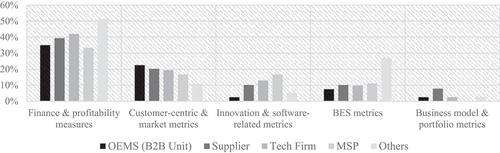

In researching success measures focusing of TM in B2B mobility BES, we assess 237 excerpts within our thematic analysis. In sum, we identify five thematic categories in relation to success metrics about B2B firms’ TM approaches: Metrics related to (1) finance and profitability (85 excerpts/39%), (2) customer and market (45 excerpts/18%), (3) innovation and software (25 excerpts/12%), (4) the BES (26 excerpts/12%) and finally (5) business model and portfolio (10 excerpts/5%). A further 44 excerpts (14%) fall into the “others” category.

First, financial and profitability metrics are the predominant indicator of a TM’s success in B2B mobility BES. This applies relatively evenly across all company types, as an analysis of the metrics by organizational cluster, see , shows. The detailed key figures focus on liquidity, turnover (relative/absolute), EBIT or return on investment (ROI). The second most important topic area identified by our analysis is the area of customer-centric, distribution and sales figures. Such metrics have become increasingly important in the academic discourse in recent years and are also considered in the context of their influence on traditional financial KPIs as firm performance (Ramani and Kumar Citation2008; Zahay and Griffin Citation2010). Within the category of customer-centric, distribution and sales figures, some firms adhere to classical KPI such as customer satisfaction. However, others focus on a more sophisticated steering landscape. This includes, customer-centered KPIs as customer loyalty, engagement, and feedback. Further, as part of their B2C2B approach, firms try to maximize end-customer experience to influence their buying behavior. Hence, the end-customer may exhibit an upstream pull-effect and thus lead to advantages for the B2B-firm. Additionally, firms are increasingly adopting the B2B sales funnel (Paschen, Wilson, and Ferreira Citation2020) and employ metrics as click rates, conversion rates, leads, and similar. This development could be attributed to the shift toward end-to-end software and service, driven by the market entrance of former B2C technology companies. Third, innovation and software metrics in our study refer to a consideration of the number of software patents, the failure rate of software products, or the amount of over-the-air updates per timeframe. This is in line with academic contributions assessing the influence of modern technology and digital transformation on the management landscape (Verhoef et al. Citation2021). The 2021 article also addresses the change in business metrics against the backdrop of new business models and the increasing focus on ecosystems (Verhoef et al. Citation2021), which we have assigned to categories four and five in our study. Fourth, metrics related to BES are mainly concerned with the number of partnerships concluded or M&As completed. In addition, companies measure the number of benchmarks performed. Fifth, the business model and portfolio indicators area relates primarily to the following key figures: Share of service business models or the share of scalable business models. An interesting finding also emerges in the “others” category where it is emphasized that measurement in scenarios is essential in the age of dynamic corporate environments: “If you move in the new, somewhat fuzzy you have to be much more consistent in control loops, more short-cycle in assessing the development of your business, (…). You can’t go back to the ABC planning calendar, which applies to everyone. You may have to manage these businesses in a completely different way” (Interviewee 30, paragraph 27).

Based on our findings, we draw the following interim conclusion:

The selection of TM success indicators remains largely independent from organizational types and management levels, with a primary focus on financial and profitability metrics.

Hence, the other metric categories identified may serve as upstream indicators exerting influence on finance and profitability as the main dependent variable. The design of these steering categories encompasses both traditional and disruptive KPIs, as explained using the example of the customer-centric, distribution and sales figures. We thus suggest that differences in TM success measurement of B2B mobility firms may arise depending on their upstream foundational TM strategy. Organizations adopting reactive and evasive strategies heavily rely on finance-related measures with a low consideration of customer-centricity, distribution, innovation, and software KPIs major levers (e.g., interview 2, 21 and 20). The trend toward integrating AI and software into hardware products as part of an evasive strategy has so far hardly been considered in steering landscapes. Companies therefore might be at risk of drawing incorrect conclusions using mainly traditional KPIs. Players following dependent strategies tend to combine traditional with modern metrics (e.g., interview 9). In doing so, financial KPI are measured in line with brand measures and end-customer-related metrics are increasingly being considered as part of a B2B2C approach. These refer for example to brand awareness or customer satisfaction measurement. Our research further reveals a shift toward relative and dynamic KPIs over absolute and static indicators. Growth metrics, especially related to software innovation, are employed to forecast TM performance.

B2B mobility companies with progressive TM approaches go one step further and consistently put customer-centricity and software-focus at the center acknowledging their direct influence on subsequent financial and profitability measures. Further, they consistently adopt dynamic, scenario-based planning. For players employing progressive approaches, in line with the growing emphasis on customer-centric value creation, former B2C KPIs gain importance. Also, innovation and software-related metrics go one step further and measure the connectivity of software to internal and external interfaces (APIs), the real-time and over-the-air personalizability and adaptability of software solutions. Experts emphasize this as being in line with achieving TM success related to customer experience metrics. Additionally, firms incorporate dynamic and scenario-based metrics to account for the disruptive nature of the mobility BESs. Finally, experts refer to business-model-driven TM metrics. This means to select business models (e.g., Software as a Service, Platform as a Service) instead of functional products as a premise for success measurement. In any case, the selection of metrics must be conducted carefully in line with the TM strategy, products, and business models. As the experts interviewed highlight: “What do we measure meaningfully? And above all, are we ready to throw away KPIs that we have had for many years? (…) You have to be careful, especially with the wrong measurability.” (Interviewee 10). Based on our findings, we suggest a second conclusion on the success measurement of TM in B2B mobility companies:

Explaining the success measurement of TM in B2B mobility companies requires the consideration of a firm’s foundational TM strategy.

In particular, the findings reveal that all strategies focus on financial and profitability KPIs and involve indicators from further four areas. However, within these categories, firms pursuing progressive approaches prioritize transformative upstream indicators in contrast to organizations following evasive, reactive, or dependent strategies emphasizing more classical indicators. The findings of this study could thus contribute to a better explanation of the success of TM phenomena.

Synthesis: findings RQ1-RQ4

Synthesizing the findings from RQ1-RQ4, we present an illustrative depiction of the category structure in . The model conveys the four primary categories defined through structural coding along with 23 sub-categories identified through open coding logic. Additionally, the approach provides an exemplary overview of detailed sub-topics associated with each category. To enhance construct validity (Gibbert, Ruigrok and Wicki Citation2008), the researchers shared the overview with three interviewees. The informants expressed substantial agreement with the proposed framework and provided minor suggestions, which were subsequently incorporated.

Theoretical and managerial contributions

Our research offers several theoretical contributions. Most importantly, the findings lay an exploratory foundation for further generalizing research and theory-building around the topic of B2B TM. The Scopus search outlined in the introduction illustrates the limited number of current B2B TM studies. Hence, our aim is to contribute to greater consideration of B2B marketing and its response to current transformational phenomena. Moreover, our research demonstrates that TM phenomena cannot be adequately understood in isolation. Instead, a comprehensive analysis, incorporating theories of the market environment such as the BES (Moore Citation1993) and the company’s resource perspective within the framework of the RBV (Barney Citation1991; Wernerfelt Citation1984), is imperative. Thus, our research is at the forefront of advancing the theoretical landscape of B2B TM by combining two important frameworks and enhancing our understanding of transformational phenomena in B2B contexts. In particular, the combination serves as a cornerstone of our theoretical contribution. By leveraging the RBV, we delve deep into the internal resources, capabilities, and competencies of B2B mobility firms, unraveling their unique strategic advantages and sources of competitive advantage. This nuanced understanding allows us to elucidate how these internal factors interact with and shape the broader BES, thereby offering profound insights into the dynamics of transformation. The RBV’s emphasis on the strategic significance of firm-specific resources and capabilities enriches our analysis by providing a lens through which we can discern how B2B mobility companies harness their internal assets to adapt, innovate, and thrive amidst disruptive forces. Moreover, by integrating the RBV with TM and the BES, our research extends beyond mere descriptive analysis to offer a comprehensive explanatory framework for understanding the intricacies of transformational processes. In essence, the integration of the RBV into our research not only enhances the theoretical robustness of our study but also empowers us to uncover deeper insights into the mechanisms driving transformational phenomena within B2B mobility ecosystems. By elucidating the interplay between internal resources, external environments, and transformational strategies, our research significantly contributes to advancing scholarly understanding and practical applications in the realm of B2B TM. In terms of the BES, we show that the perception of a turbulent environment varies depending on the type of company and has a major influence on a firm’s transformation. In relation to the RBV, our results demonstrate that within the B2B TM context, a stronger focus should be placed on identifying supportive and hindering transformation resources. Therefore, we suggest labeling the difference between current resources (both beneficial and obstructive) and necessary resources as the “transformative resource gap (TRG).” By introducing this concept, we believe that the RBV can be strengthened by encompassing multiple dimensions. We believe that integrating this perspective into TM will result in a more comprehensive theoretical understanding of transformational phenomena and – as implied by the RBV – the explanation of strategic competitive advantages. Next, in terms of theoretical contributions, our study emphasizes that a conceptualization of TM grounded in the marketing mix (Lim Citation2023) provides a solid foundation. However, the strategic and relationship marketing elements within the context of B2B TM need further refinement in the conceptualization of TM. Lastly, to the best of our knowledge, we have introduced a novel TM typology based on our findings, which should facilitate further exploration of the TM topic within the research community. As an additional theoretical contribution, we have also demonstrated that the explanation of TM success and the selection of appropriate metrics are related to the chosen foundational TM strategy.

Along with the aspects described, we also offer several managerial contributions. First, we provide a detailed understanding of the disruptive BES as the context of TM. This offers the possibility to foster companies’ BES intelligence including an end-customer centric perspective. Within that respect, it is recommended that companies validate the basic market assumptions close to the customer to reduce the corresponding risks of misjudgments. Further, our research sets the course for a targeted identification, understanding, and adaptation of enabling and hindering resources in transformational processes. Using a so-called “transformative resource gap (TRG),” could help to explain the initial situation of a company and thus more thoroughly examine the success of TM in practice. Next, our study offers new impulses on how TM instruments from six overall categories can be employed by firms within a holistic approach. Our research highlights that the confluence, identified by Kumar (Citation2018) as a core characteristic of TM in his seminal definition, is not consistently applied in corporate practice. Rather, a considerable number of firms in our study implement corresponding measures within the framework of individual instruments rather than adopting an integrated approach. Our insights can help companies to consciously deal with the proactivity and intensity achieved and the analyze associated risks in their marketing approaches. The selected matrix may also offer a helpful starting point for pursuing a progressive strategy. This also raises questions about the extent to which a company assesses the quality of its TM processes using appropriate indicators. In general, the introduction of dynamic, scenario-based, and multi-level measurement models is recommended, as our results indicate that, irrespective of company types, they are best suited for turbulent environments.

Discussion and future research directions

Our study is subject to various constraints. First, limitations are attributable to the qualitative approach. While expert interviews lead to in-depth insights, rigor might be more difficult to demonstrate. While adhering to the principle of data saturation, a sample size of 30 may still not be fully representative of the entire population. The same holds true for the criteria-based, purposive sampling method. Like all nonrandom techniques, it poses potential threats to generalization (Hibberts, Burke Johnson, and Hudson Citation2012). Further, despite the inclusion of a questionnaire and secondary data, the focus on qualitative data as a major source might carry a risk of common method bias (MacKenzie and Podsakoff Citation2012). Second, related to the question of representativeness, we exclusively focus on the level of highly experienced managers. Yet, the involvement of the operational levels of the companies could also provide further valuable impetus. Third, the study is subject to a sectoral and geographical focus. Given our recognition of B2B mobility as a notably transformative environment, we chose it as the application context. However, TM in other highly disruptive BESs such as retail, and in both B2C and B2B contexts, may differ from our findings. The same applies to the geographical scope; while our focus is on Europe and the U.S., the results may not be directly transferable to other regions, such as Asia. Fourth, the theoretical underpinning of this work is centered around the Resource-Based View (RBV). This lens was chosen because the approach has been used in previous studies on dynamic BESs as well as TM, making it suitable as an overarching frame for this work. Yet, the RBV primarily focuses on the internal aspects of an organization to analyze competitive sustainable advantage through (in)tangible, non-substitutable and non-imitable resources. Thus, it is crucial to ensure the consideration of external factors and further test the influence of other theories on B2B TM.

To reduce the barriers described, this work could be followed up by further examinations whereof we consider four angles to be particularly important. First, to enhance the qualitative results within a second study on operational levels. In that respect, a subsequent comparison with the findings of this study could lead to interesting additional insights. For instance, our results already showed that the aspect of customer orientation varies significantly between lower, middle, and upper management levels. It is therefore possible that operational levels also exhibit particularities in relation to the phenomena studied. Second, the findings of this work lay a foundation for further generalizing research. We, therefore, recommend developing a conceptual model and quantitatively verifying it through a large-scale questionnaire study. Studies could examine the impact of independent variables (e.g., different BES morphologies) on dependent variables (e.g., transformation success). Further, as there might be differences by region, function, company size or management levels, group analyses may aid to generate further insights on moderating and mediating levers. Third, to verify the findings gathered within this study in further geographical contexts to account for cultural differences. This could, for instance, be enabled through a cross-national research setup and a consideration of the Asian mobility market as an important player in B2B mobility. Fourth, the exploration of B2B TM phenomena using the example of other turbulent market environments, such as retail. Comparing the results of several disruptive BESs could lead to more reliability in drawing conclusions about the theory of TM and thus lead to higher rigor in the field. Sixth, this manuscript has contributed to linking TM with the concepts of BES and RBV to increase explanatory power of related studies. As a future research angle, the identified phenomena, including market environment perception (BES) and supportive and hindering resources (RBV) and their relevance for TM should be further validated through qualitative and quantitative studies. Additionally, there is potential for in-depth research on other theories in the context of TM in dynamic B2B BES. This includes exploring marketing and service theories, such as Engagement Marketing Theory (Kumar Citation2018), as well as theories of national culture, like Hofstede (Citation2001), and related concepts such as risk aversion, short- versus long-term orientation, and other factors that can contribute to a better understanding of TM phenomena.

Summary

The objective of this work was to enhance the field of B2B TM through a comprehensive empirical investigation of the prototypical yet highly transformative case of mobility ecosystems. By integrating the concepts of the RBV and BESs, we sought to enhance the theoretical foundation of TM and provide new theoretical and practical contributions. Using the RBV, we offer a comprehensive explanatory framework for understanding the intricacies of transformational processes and show how the internal resources, capabilities, and competencies of B2B mobility BES unravel their unique sources of competitive advantage. This understanding provides profound insights into the dynamics of disruptive TM. For this purpose, we conducted in-depth, partly standardized qualitative expert interviews with 30 managers from 28 mobility companies. The angle of B2B mobility ecosystems as an application context was chosen, as it is subject to uniquely intense transformational processes. Our study unveils the following major findings related to the four research questions defined. Related to RQ1, aimed at investigating the evidence of a morphology of disruptive B2B mobility BES, we propose four major characterization patterns. We observe that suppliers have not yet shifted from a value-based approach to an ecosystem-based approach and lack a customer-centric perspective (Fader Citation2012; Kohli and Jaworski Citation1990; Narver and Slater Citation1990). Concerning RQ2, which aimed to investigate the “transformation readiness” of B2B mobility firms based on the RBV (Barney Citation1991; Wernerfelt Citation1984) as a prerequisite for examining their TM approach, we find that a mobility company’s readiness for transformation is significantly influenced by its commitment to designing a market-oriented and integrated organization, its adoption of a transformative culture, and its success in acquiring software-oriented human capital.

Related to RQ3, we share new insights on TM instruments applied in B2B mobility and discuss the existence of a typology of comprehensive TM strategies. Our findings suggest that the instruments applied in B2B mobility BES relate to six thematic categories and are dominantly characterized by strategic levers as a previously underexamined factor. Further, we propose four foundational TM strategies evident, namely dependent, progressive, reactive, and evasive approaches, distinguishable through their intensity and proactivity. While investigating RQ4, which addresses the success measurement of TM in B2B mobility companies, we discover that the selection of indicators within our study remains mostly independent of organizational types and management levels, with a primary emphasis on financial and profitability metrics. Instead, our study reveals that explaining the success of TM in B2B mobility companies requires considering a firm’s foundational TM strategy. In sum, with our findings, we hope to offer a meaningful contribution to the field’s theoretical and practical development.

Research ethics/informed consent

This research adheres to the ethical principles of the Comité d’Éthique de la Recherche (CER), Université de Toulouse, France. Informed written consent by the experts has been obtained prior to the commencement of the interviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Anonymized data will be made available on request.

Notes

1. The management levels are defined by the management span: lower management (1–10 employees), middle management (11–50 employees) and upper management (>50 employees).

2. For this purpose, the shares of subtopics were calculated for each company type. Example: For tech firms, there is a total number of 82 excerpts with a focus on BES morphology among which the proportion with a focus on “configuration” comprises 20% (16 excerpts). For reasons of visual clarity, the category “others” was not included in the figure.

References

- Aime, I., F. Berger-Remy, and M. E. Laporte. 2022. The brand, the persona and the algorithm: How datafication is reconfiguring marketing work. Journal of Business Research 145:814–27. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.03.047.

- Aragon-Correa, J. A. 1998. Strategic proactivity and firm approach to the natural environment. Academy of Management Journal 41 (5):556–67. doi:10.2307/256942.

- Barney, J. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17 (1):99–120. doi:10.1177/014920639101700108.

- Bowen, G. A. 2008. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qualitative Research 8 (1):137–52. doi:10.1177/1468794107085301.

- Cha, H. 2020. A paradigm shift in the global strategy of MNEs towards business ecosystems: A research agenda for new theory development. Journal of International Management 26 (3):100755. doi:10.1016/j.intman.2020.100755.

- Cobben, D., W. Ooms, N. Roijakkers, and A. Radziwon. 2022. Ecosystem types: A systematic review on boundaries and goals. Journal of Business Research 142:138–64. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.12.046.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., and D. C. Galunic. 2000. Coevolving: At last, a way to make synergies work. Harvard Business Review 78 (1):91–101.

- Elia, G., G. Polimeno, G. Solazzo, and G. Passiante. 2020. A multi-dimension framework for value creation through big data. Industrial Marketing Management 90:508–22. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.08.004.

- Erevelles, S., N. Fukawa, and L. Swayne. 2016. Big data consumer analytics and the transformation of marketing. Journal of Business Research 69 (2):897–904. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.07.001.

- Fader, P. 2012. Customer centricity: Focus on the right customers for strategic advantage. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Wharton Digital Press.

- Fusch, P. I., and L. R. Ness. 2015. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report 20 (9):1408–16. doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2281.

- Gibbert, M., W. Ruigrok, and B. Wicki. 2008. What passes as a rigorous case study?. Strategic Management Journal 29 (13):1465–74. doi:10.1002/smj.722.

- Guest, G., A. Bunce, and L. Johnson. 2006. How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18 (1):59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903.

- Gurrieri, L., L. Tuncay Zayer, and C. A. Coleman. 2022. Transformative advertising research: Reimagining the future of advertising. Journal of Advertising 51 (5):539–56. doi:10.1080/00913367.2022.2098545.