ABSTRACT

Family members are a key source of services and supports for people with disabilities across the life course, helping people to remain living at home and in the community. As part of an effort to generate a strategic plan for research on family caregiver experiences and supports, this issue includes four literature reviews on the current state of research, each specific to a life course stage. This introduction presents a framework that combines life course and ecological perspectives to organize the existing literature of family caregiver support and to identify gaps in existing research, as well as opportunities for future investigations.

In the United States, family members are a primary, and frequently unpaid, source of support for people with disabilities, assisting with tasks that promote community living and integration across the life course. In childhood, youth with mental illness and/or disabilities, including those with intellectual, developmental, and physical impairments, have unique social and health care needs. Parents play major roles as caregivers, advocates, and system navigators. As their children grow through adolescence and into adulthood, parents continue to advocate, and also share that activity with children who grow into the self-advocate role. In adulthood, families also provide a broad range of assistance, helping individuals to lead meaningful lives in the community, including educational attainment and employment, and to avoid unnecessary and undesired institutionalization. As individuals with disabilities age, and adults who are nondisabled acquire impairments in mid- and late life, family dynamics change as spouses and partners renegotiate relationship boundaries within the caregiver role, aging parents transition responsibilities to sibling caregivers, and adult children begin to provide care for parents with age-related impairments, including Alzheimer’s disease.

We are in the process of developing a national strategic research plan for family support as part of the Family Support Research and Training Center. Our research into the current state of family support allowed us to create a special issue that provides a snapshot of existing knowledge about family support across four life course stages: infancy and early childhood, adolescence and young adulthood, midlife, and later life. Informed by an ecological systems framework (Sallis & Owen, Citation2002), these reviews devote attention to the individual and family in community and national policy contexts. Further, within each life course stage, the focus on family caregiving provides a platform to compare and contrast caregiving needs and experiences across groups of people with varied impairments or disabilities. Collectively, the literature reviews that make up this issue summarize and evaluate the literature on the care, support, and services provided by family members; the positive and negative impacts experienced by family caregivers; the supports they used and need, including public programs and interventions; and the societal impacts of family caregiving.

This special issue stands as testament to the impressive array of existing family support literature summarizing the findings of more than 250 individual articles. Through their reviews, the authors outline opportunities for producing research that engages new, or expands existing, questions about family caregiving in the United States. In this introduction, we offer context for the structure and scope of the literature reviews that follow. First, we highlight the demographic, social, and economic significance of family caregiving in the United States. Next, we provide a rationale for this special issue and the larger effort to generate a national strategic research plan. We conclude by using the ecological systems framework to highlight the state of current caregiving knowledge and the gaps to be addressed in future research as described by the articles in this issue.

Family caregivers: An important source of support for community living

In the United States, nearly 12 million individuals with disabilities need long-term services and supports (LTSS) to sustain their lives at home and in the community, split almost evenly between those younger than age 65 (44%) and those older than age 65 (56%; Kaye, Harrington, & LaPlante, Citation2010). As the population ages, the need for LTSS is projected to more than double to 26 million by 2050. Currently, almost 92% of older adults who receive LTSS at home receive some amount of family support, with 66% receiving all of their support from family members. With respect to adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDDs), nearly three fourths (72%) live at home with a family caregiver (Braddock et al., Citation2013).

Given the increasing need for community living assistance and the role of family members in providing these forms of care, services, and supports, it is perhaps not surprising that there are nearly 43.5 million informal family caregivers in the United States, 60% of whom are women (National Alliance for Caregiving, Citation2015). Economically, the equivalent labor costs for currently unpaid family caregivers for adults age 18 and older have been estimated at $470 billion in 2013 (Reinhard, Feinberg, Choula, & Houser, Citation2015). Notably, this amount is more than triple the total amount spent on LTSS by Medicaid ($134.1 billion), the largest payer of these services in the United States (O’Shaughnessey, Citation2014).

In light of the demographic frequency and economic value of family caregiving, research needs to address the experiences and scope of work provided by family members, the impact of this work on caregivers, and the meaning of this work for society at large. These efforts will help to identify the support needs of caregiving families, influence program development and resource allocation, and shape social, health, and family policy.

Family caregiver research: Planning for the future

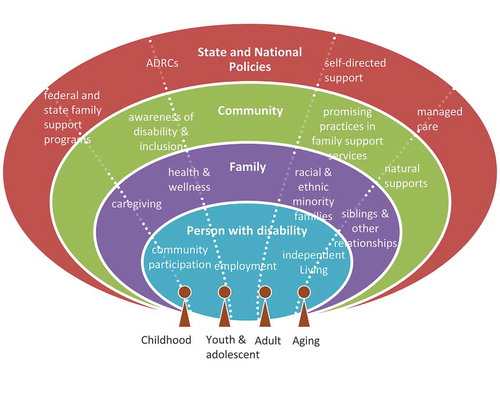

This special issue contributes to the development of the strategic research plan by providing baseline information about what research exists on the topic of family support of persons with disabilities. We use a conceptual framework that incorporates ecological and life course theories (see ). Ecological theory posits that there are multiple levels of influence on individuals and their outcomes and focuses on the interaction between the person and his/her environment (Sallis & Owen, Citation2002). Building on the work of Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) who conceptualized microsystem, mesosystem, and exosystem levels that interact with each other; we propose an ecological model that includes the following levels: person with disability, family, community, and state and national policies. Although all of the levels influence the experiences of the persons with disability and their families, this model allows for conceptualizing any of the levels as targets for change. In other words, change activities may target individuals with disabilities and families through caregiver and family interventions; they may target community level programs, events, and organizations to better serve people with disabilities and their families; or they may target state and national policies for change to address the needs individuals with disabilities and their families in cost-effective ways.

The life course perspective allows us to explore the experience of individuals and families as they relate to their developmental processes or stages with a recognition of development as continuous and dynamic (Elder & Giele, Citation2009; Heller & Parker-Harris, Citation2012). A distinction between life-course and life-span approaches is that the latter often focuses on the “typical life course” whereas the former recognizes that there is great variation and multiple pathways across individuals and families (Elder & Giele, Citation2009). Therefore, a life-course perspective allows for diversity in terms of individuals aging with disabilities as well as individuals aging into disability, in other words acquiring disabilities in later life. An important concept within life course theory is that of transitions (Heller & Parker-Harris, Citation2012). Transitions are important in the lives of people with disabilities and their families as each transition period often means a transition from one service or educational system to another in addition to transitions to different stages in the life course.

Family caregiving across the life course: Applying the eco-systems framework

Across the four articles included in this review, the eco-systems framework allows for an understanding of the current state of knowledge at different levels of analysis and intervention. Given the qualitatively different experiences of family caregivers at distinct life course stages, existing research and identified research gaps can be discussed as they relate to the personal, familial, community, and programmatic/policy contexts. Despite the uniqueness associated with caregiving experiences within life course stages, shared themes relevant across the life course emerge and an eco-systems framework can address these as well. In this section, we employ this perspective to highlight how these nested levels offer vistas through which to envision future research, addressing gaps in knowledge within each life course stage and building bridges to focus on family caregiving topics relevant across caregiver age categories.

Personal level: Individuals with disabilities, individual caregivers

Within each life course stage, researchers have documented the types of care, services, and support that family members provide while highlighting the breadth of these activities. The type of support provided to family members with disabilities varies widely across age groups, as well as across disability or impairment type. For example, from birth through early childhood family caregiving uniquely includes a focus on play for parent and sibling caregivers (Guralnick, Connor, & Johnson, Citation2009; Kresak, Gallagher, & Rhodes, Citation2009). By contrast, family members caring for adults and older adults are tasked with managing medications (Erickson & LeRoy, Citation2015; Hodgson, Gitlin, Winter, & Hauck, Citation2014). However, at the individual caregiver level, we need to better understand the amount of time and financial resources family members invest in providing these tasks, data with implications for understanding caregiving across multiple levels of analysis (e.g., family training interventions, state/national policies regarding paying family members, etc.) and cumulatively across the life course.

We also need to understand more about how family provision of care, supports, and services can influence outcomes for individuals with disabilities, such as community participation, employment, health and wellness, and independent living. Results from the Cash and Counseling Demonstration & Evaluation project highlight the greater level of both comfort and access experienced by care recipients when able to hire family members for intimate care or tasks completed outside of the home (San Antonio et al., Citation2010). Some interventions engage family members and adults with disabilities who are receiving care and demonstrate improvements in decision making, empowerment, or perceived social support (Heller & Caldwell, Citation2006; Perlick et al., Citation2013). Additionally, psychoeducational interventions for families caring for adults with schizophrenia have demonstrated positive health outcomes not only for caregivers, but for care recipients as well, including reductions in relapse and hospitalizations (Dixon et al., Citation2010; Kopelowicz, Zarate, Smith, Mintz, & Liberman, Citation2003). However, the majority of current research on family caregiving focuses exclusively on those providing the care and neglects care recipients, in contrast with larger policy shifts toward person-centered planning and self-determination (Medicaid Program, Citation2014).

In addition, we need gain more understanding in how individuals with disabilities view their families and the support they provide. For example, there is often a tension between the views of people with disabilities and their parents (particularly adolescents and adults with disabilities) in which the former may want to push for more independence and autonomous decision making and the latter may be somewhat overprotective (Carey, Citation2009). These tensions are likely to be amplified when adults are coresiding with their parents, which may negatively affect the adult with disabilities and their family caregivers (Devine, Wasserman, Gershenson, Holmbeck, & Essner, Citation2010), although there is some research that highlights families of adolescents with disabilities experience closer relationships and less family conflict (Hartley, Barker, Seltzer, Greenberg, & Floyd, Citation2011; Jandazek, DeLucia, Holmbeck, Zebrack, & Friedman, Citation2009). These issues may vary across racial and ethnic groups in which interdependence is a prized value versus independence (Ben-Moshe & Magaña, Citation2014).

Family

At the family level, researchers must pay attention to the experiences and needs of racial and ethnic minority families. Only about one-third of the studies included in the review were based on samples that included sizeable populations of people of color. Some of these focused specifically on one racial or ethnic group (e.g., Kao, Romero-Bosch, Plante, & Lobato, Citation2012; Kim & Knight, Citation2008; Ramírez García, Hernández, & Dorian, Citation2009; Shapiro, Monzó, Rueda, Gomez, & Blacher, Citation2004), whereas a smaller subset compared two or more minority racial groups (e.g., Magaña & Smith, Citation2006, Citation2008). However, nearly one in five articles had samples that were greater than 90% White, with this research accounting for a greater percentage of studies in the research on adolescence, middle adulthood, and old age than early childhood.

As evident in the literature, these families are frequently underserved and lack access to culturally competent supports across the life course (e.g., Al Khateeb, Al Hadidi, & Al Khatib, Citation2014; Magaña & Smith, Citation2008; Scharlach, Giunta, Chow, & Lehning, Citation2008). Additionally, more research needs to include the impact of cultural beliefs on the practices of family caregiving in cross-cultural and culture-specific research at different life-course stages (see, e.g., Fingerman, VanderDrift, Dotterer, Birditt, & Zarit, Citation2011; Sage & Jegatheesan, Citation2010; Sander et al., Citation2007). For example, a combination of sociocultural and economic factors may make families a more common source of care in recovery from traumatic brain injury (TBI) for African Americans and Latinos than Whites (Gary, Arango-Lasprilla, & Stevens, Citation2009). Similarly, these factors may make it more likely for older adults from certain ethnic groups to live with family members providing care (Scharlach et al., Citation2006; Thai, Barnhart, Cagle, & Smith, Citation2015).

We also need to improve our understanding of the needs of other diverse families, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) families that face many barriers in accessing the formal service system and other challenges. The majority of research across the life course neglects to acknowledge the existence of LGBT people as family members, as either caregivers or recipients of care, an oversight that ignores the economic challenges and need for assistance among LGBT older adults (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Kim, Barkan, Muraco, & Hoy-Ellis, Citation2013). The voices of trans, disability activists writing about how disability social policy affects their plans for family formation are also left out (Davis, Citation2015; Evans, Citation2015). Given the increase in LGBT parents over the last 2 decades, future research on family caregiving needs to provide space for identification of sexual and gender identity (see Mayer, Bradford, Makadon, Stall, Goldhammer, & Landers, Citation2008).

Family relationships and dynamics are also critical to understanding the context of family support and intervention approaches. For example, siblings play important roles in the lives of many individuals with disabilities across the life span and frequently assume greater family caregiving roles when aging parents pass away or are no longer able to provide supports (Arnold, Heller, & Kramer, Citation2012; Heller & Arnold, Citation2010; Heller & Kramer, Citation2009). Recent research has addressed expectations for future caregiving for siblings of adults with IDDs, highlighting the relationship between anticipated caregiving and current parental caregiving and sibling closeness (Burke, Taylor, Urbano, & Hodapp, Citation2012). However, in general, the perspectives and needs of siblings have been often overlooked and siblings have rarely been included in interventions.

Moreover, supports are often bidirectional and operate at multiple levels within families. Although individuals with disabilities receive supports from family caregivers, they also provide a great deal of support to family caregivers and other family members. For example, younger individuals with disabilities may be receiving supports from and providing supports to aging parents that have acquired disabilities. Spouses with disabilities may be providing supports to each other. Many caregivers in so-called sandwich generation are simultaneously supporting children, sometimes with disabilities, and aging parents with disabilities. As family caregivers approach midlife or early old age, some parents of adults with disabilities who have established patterns of caregiving experience “compound caregiving” in which they acquire new (and often multiple) people to care for in the form of ailing spouses or older adults (Ghosh, Greenberg, & Seltzer, Citation2012; Perkins, Citation2010).

Community

At the community level, we need to better understand the delivery of formal services and supports by the aging and disability networks and broader community-based support systems. Although formal services are often structured at the state level, they ultimately are implemented at the local level. Community-based organizations play a large role in influencing the availability and quality of support available.

The Administration on Community Living (ACL) has been a resource in identifying, assessing, and promoting evidence-based interventions. These interventions need to be implemented on a larger scale by community-based organizations (Heller & Caldwell, Citation2006).

Research across the life course and across family caregivers of different populations of people with disabilities indicate that peer-led programs result in significant positive changes in terms of action and caregiving well-being (Acri et al., Citation2015; Dykens, Fisher, Taylor, Lambert, & Miodrag, Citation2014; Heller & Caldwell, Citation2006; Marquez & Ramírez García, Citation2013; Narr & Kemmery, Citation2015). However, research also highlights the limitations of these programs in terms of cultural relevance or responsiveness to the unique experiences of ethnic minorities in the social service system (Barrio & Dixon, Citation2012; Smith et al., Citation2014). Promising practices need to be identified, assessed, and further developed.

Beyond formal aging and disability services, local communities and businesses also influence supports. For example, businesses have begun to better understand the business case for implementing workplace policies, such as workplace flexibility, leave, and supports to employees who are also informal caregivers for family members with disabilities (Feinberg, Citation2013). Furthermore, faith-based organizations have also assisted at the community level in meeting unmet needs for family support services for parents of young children with autism spectrum disorder, in particular, religion and spirituality has been positively associated with well-being (Ekas, Whitman, & Shivers, Citation2009). Greater levels of spiritual involvement have been reported for African American and Latino parents of children with disabilities, and research has documented how Latino and Asian American parents have reframed their children’s disability within religious terms (Jegatheesan, Miller, & Fowler, Citation2010; Lobar, Citation2014; Manning, Wainwright, & Bennett, Citation2011; Taylor et al., Citation2005). Future research needs to explore the role of these community-level organizations and the mechanisms through which they provide support to family members assisting people with disabilities across the life course.

State and national policies

At the state and national levels, a patchwork of various family support programs exists with eligibility often tied to age, disability category, or other status. The Administration on Community Living (ACL) operates the National Family Caregiver Support Program, Lifespan Respite Program, and family support activities provided through the Projects of National Significance in the Developmental Disabilities Act. These services are available to family members who provide care, support, and services across the life course. In addition, Aging and Disability Resource Centers (ADRCs) can play important roles in supporting adults and older adults with disabilities. The evolving framework for ADRCs strengthens the inclusion of individuals with disabilities and usage of person-centered planning. Research on the utilization of these services must account for sociocultural and economic barriers to access and the unmet need for family support services (i.e., where demand outstrips supply or available resources).

A wide range of programs outside of ACL also support family caregivers who are assisting people with disabilities across the life course. In early childhood and the school years, families may access informational, counseling, and other family support services initially through the Individualized Family Support Plans via Early Intervention Services (EIS) and later, through Individualized Education Programs (IEP). Family to Family Information Centers operated by Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and the Maternal Child Health Bureau (MCHB) provide peer support and information to families of children with special health care needs. The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) provides critical workplace protections and opportunities for leave for caregivers. However, research shows these supports might be more challenging for some families to access due to information barriers and difficult processes of requesting access and that higher earning families are more likely to use these services than low-income families (Chung et al., Citation2013; Kerr, Citation2016).

For caregivers of adults and older adults with disabilities, the Veterans Administration operates extensive, model caregiver support programs that provide information, evidence-based interventions, and financial assistance (e.g., Bass et al., Citation2012; Lutz, Chumbler, Lyles, Hoffman, & Kobb, Citation2009; Perlick et al., Citation2013). Throughout the life course, Medicaid influences family caregiving experiences through its role as the primary funding stream for LTSS. In childhood, parents of children with disabilities may act as coordinators of services and evaluators of quality, as one study of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder found (Timberlake, Leutz, Warfield, & Chiri, Citation2014). In adulthood, Medicaid offers an opportunity for greater autonomy and self-direction, for all program recipients, including people with mental illness, people with IDDs, and older adults, populations previously thought unable or uninterested in decision making (San Antonio et al., Citation2010; Shen et al., Citation2008).

Employing a life-course perspective allows for a cross-age focus on programmatic transitions for families providing care, services, and supports for people who are disabled. For example, the experiences of the transitions from early intervention to schools (Marshall, Tanner, Kozyr, & Kirby, Citation2014) can be understood in comparison to the transition from schools to employment and community living programs (Timmons, Whitney-Thomas, McIntyre, Butterworth, & Allen, Citation2004) and as part of a cumulative trajectory of systems change/transitions for family units, individuals with disabilities, and disabled people, themselves. Future research should attend to these transitions within life course stages and look at the utility of comparing across these transitions, in terms of acquired skills, emotional experiences, and feelings of trust toward individual and family assistance programs.

The current state of the family caregiving literature

The articles in this special issue further describe the literature across the life course and identify gaps in the research. Meghan M. Burke, Kimberly A. Patton, and Julie Lounds Taylor detail the research on adolescents with a focus on transition issues in their practice and conceptual article “Family Support: A Review of the Literature on Families of Adolescents with Disabilities.” In the research article “Characterizing the Systems of Support for Families of Children with Disabilities: A Review of the Literature,” Sandra B. Vanegas and Randa Abdelrahim describe the existing literature on children with disabilities and highlight the needs for future research. The research article “The Family Caregiving Context among Adults with Disabilities: A Review of the Research on Developmental Disabilities, Serious Mental Illness, and Traumatic Brain Injury” by Concepcion Barrio, Mercedes Hernandez, and Lizbeth Gaona highlights research on family members who support adults with disabilities. Lastly, in their research article “Family Support in Late Life: A Review of the Literature on Aging, Disability, and Family Caregiving,” Brian R. Grossman and Catherine E. Webb discuss issues for aging caregivers of persons with disabilities. Each of the articles uses the life-course and ecological perspective and brings in family support issues across disabilities. Although each identifies gaps in the literature, most of the reviews focus on developmental disabilities, mental illness, traumatic brain injury, and disabilities related to aging, primarily because these are the more widely studied areas of caregiving research. A large gap in the literature is on family support children and adults with physical impairments, which is an area that needs clearly future research attention. To conclude, these articles on family support across the life course will contribute greatly to the development of a strategic plan for research on family support across the life course and will be useful to students and scholars who wish conduct future research on family support.

Funding

Work on this article was supported by the Family Support Research and Training Center at the University of Illinois at Chicago (Magaña PI, NIDILRR 90RT50320-01-00).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acri, M., Frank, S., Olin, S. S., Burton, G., Ball, J. L., Weaver, J., & Hoagwood, K. E. (2015). Examining the feasibility and acceptability of a screening and outreach model developed for a peer workforce. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 341–350. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9841-z

- Al Khateeb, J. M., Al Hadidi, M. S., & Al Khatib, A. J. (2014). Addressing the unique needs of Arab American children with disabilities. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 2432–2440. doi:10.1007/s10826-014-0046-x

- Arnold, C. K., Heller, T., & Kramer, J. (2012). Support needs of siblings of people with developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50(5), 373–382. doi:10.1352/1934-9556-50.5.373

- Barrio, C., & Dixon, L. (2012). Clinician interactions with patients and families. In J. A. Liberman & R. M. Murray (Eds.), Comprehensive care of schizophrenia: A textbook of clinical management (pp. 342–356). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Bass, D. M., Judge, K. S., Snow, A. L., Wilson, N. L., Looman, W. J., McCarthy, C., … Kunik, M. E. (2012). Negative caregiving effects among caregivers of veterans with dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(3), 239–247. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31824108ca

- Ben-Moshe, L., & Magaña, S. (2014). An introduction to race, gender, and disability: Intersectionality, disability studies, and families of color. Women, Gender, and Families of Color, 2(2), 105–114. doi:10.5406/womgenfamcol.2.2.0105

- Braddock, D., Hemp, R., Rizzolo, M. C., Tanis, E. S., Haffer, L., Lulinski, A., & Wu, J. (2013). The state of the states in developmental disabilities 2013: The great recession and its aftermath (Preliminary ed.). Boulder, CO: University of Colorado, Department of Psychiatry and Coleman Institute, and University of Illinois at Chicago, Department of Disability and Human Development.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by design and nature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Burke, M. M., Taylor, J. L., Urbano, R. C., & Hodapp, R. M. (2012). Predictors of future care-giving by adult siblings of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117, 33–47. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-117.1.33

- Carey, A. (2009). On the margins of citizenship: Intellectual disability and civil rights in twentieth-century America. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Chung, P. J., Garfield, C. F., Elliott, M. N., Vestal, K. D., Klein, D. J., & Schuster, M. A. (2013). Access to leave benefits for primary caregivers of children with special health care needs: A double bind. Academic Pediatrics, 13, 222–228. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2013.01.001

- Davis, J. G. (2015). Op-ed: Why no matter what, I still can’t marry my girlfriend. Advocate. Retrieved from http://www.advocate.com/commentary/2015/06/29/op-ed-why-no-matter-what-i-still-cant-marry-my-girlfriend

- Devine, K. A., Wasserman, R. M., Gershenson, L. S., Holmbeck, G. N., & Essner, B. S. (2010). Mother-adolescent agreement regarding decision-making autonomy: A longitudinal comparison of families of adolescents with and without spina bifida. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36, 277–288. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsq093

- Dixon, L. B., Dickerson, F., Bellack, A. S., Bennett, M., Dickinson, D., Goldberg, R. W., … Kreyenbuhl, J. (2010). The 2009 Schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36, 48–70. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp115

- Dykens, E. M., Fisher, M. H., Taylor, J. L., Lambert, W., & Miodrag, N. (2014). Reducing distress in mothers of children with autism and other disabilities: A randomized trial. Pediatrics, 134, 454–463. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3164

- Ekas, N. V., Whitman, T. L., & Shivers, C. (2009). Religiosity, spirituality, and socioemotional functioning in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(5), 706–719. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0673-4

- Elder, G. H., & Giele, J. Z. (Eds.). (2009). The craft of life course research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Erickson, S. R., & LeRoy, B. (2015). Health literacy and medication administration performance by caregivers of adults with developmental disabilities. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association, 55(2), 169–177. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2015.14101

- Evans, D. L. (2015). Disabled people penalized for getting married. Audacity Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.audacitymagazine.com/disabled-people-penalized-for-getting-married/

- Feinberg, L. (2013) Keeping up with the times: Supporting family caregivers with workplace leave policies (Insight on the Issues 82). Retrieved from AARP Public Policy Institute website http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/ltc/2013/fmla-insight-keeping-up-with-time-AARP-ppi-ltc.pdf

- Fingerman, K. L., VanderDrift, L. E., Dotterer, A. M., Birditt, K. S., & Zarit, S. H. (2011). Support to aging parents and grown children in black and white families. The Gerontologist, 51(4), 441–452. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq114

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Kim, H.-J., Barkan, S. E., Muraco, A., & Hoy-Ellis, C. P. (2013). Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1802–1809. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110

- Gary, K. W., Arango-Lasprilla, J. C., & Stevens, L. F. (2009). Do racial/ethnic differences exist in post-injury outcomes after TBI? A comprehensive review of the literature. Brain Injury, 23(10), 775–789. doi:10.1080/02699050903200563

- Ghosh, S., Greenberg, J. S., & Seltzer, M. M. (2012). Adaptation to a spouse’s disability by parents of adult children with mental illness or developmental disability. Psychiatric Services, 63(11), 1118–1124. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201200014

- Guralnick, M. J., Connor, R. T., & Johnson, L. C. (2009). Home-based peer social networks of young children with Down syndrome: A developmental perspective. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 114, 340–355. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-114.5.340

- Hartley, S. L., Barker, E. T., Seltzer, M. M., Greenberg, J. S., & Floyd, F. J. (2011). Marital satisfaction and parenting experiences of mothers and fathers of adolescents and adults with autism. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 116, 81–95. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-116.1.81

- Heller, T., & Arnold, C. K. (2010). Siblings of adults with developmental disabilities: Psychosocial outcomes, relationships, and future planning. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 7(1), 16–25. doi:10.1111/ppi.2010.7.issue-1

- Heller, T., & Caldwell, J. (2006). Supporting aging caregivers and adult with developmental disabilities in future planning. Mental Retardation, 44(3), 189–202. doi:10.1352/0047-6765(2006)44[189:SACAAW]2.0.CO;2

- Heller, T., & Kramer, J. (2009). Involvement of adult siblings of persons with developmental disabilities in future planning. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 47(3), 208–219. doi:10.1352/1934-9556-47.3.208

- Heller, T., & Parker-Harris, S. (2012). Disability through the life course. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Hodgson, N., Gitlin, L. N., Winter, L., & Hauck, W. W. (2014). Caregiver’s perceptions of the relationship of pain to behavioral and psychiatric symptoms in older community residing adults with dementia. Clinical Journal of Pain, 30(5), 421–427.

- Jandazek, B., DeLucia, C., Holmbeck, G. N., Zebrack, K., & Friedman, D. (2009). Trajectories of family processes across the adolescent transition in youth with spina bifida. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 726–738. doi:10.1037/a0016116

- Jegatheesan, B., Miller, P. J., & Fowler, S. A. (2010). Autism from a religious perspective: A study of parental beliefs in South Asian Muslim immigrant families. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 25, 98–109. doi:10.1177/1088357610361344

- Kao, B., Romero-Bosch, L., Plante, W., & Lobato, D. (2012). The experiences of Latino siblings of children with developmental disabilities. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38, 545–552.

- Kaye, H. S., Harrington, C., & LaPlante, M. (2010). Long-term care: Who gets it, who provides it, who pays, and how much? Health Affairs, 29(1), 11–21.

- Kerr, S. P. (2016). Parental leave legislation and women’s work: A story of unequal opportunities. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 35, 117–144. doi:10.1002/pam.21875

- Kim, J.-H., & Knight, B. G. (2008). Effects of caregiver status, coping styles, and social support on the physical health of Korean American caregivers. The Gerontologist, 48(3), 287–299. doi:10.1093/geront/48.3.287

- Kopelowicz, A., Zarate, R., Smith, V. G., Mintz, J., & Liberman, R. P. (2003). Disease management in Latinos with schizophrenia: A family-assisted, skills training approach. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 29, 211–228. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006999

- Kresak, K. E., Gallagher, P. A., & Rhodes, C. (2009). Siblings of infants and toddlers with disabilities in early intervention. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 29, 143–154. doi:10.1177/0271121409337949

- Lobar, S. L. (2014). Family adjustment across cultural groups in autistic spectrum disorders. Advances in Nursing Science, 37, 174–186. doi:10.1097/ANS.0000000000000026

- Lutz, B. J., Chumbler, N. R., Lyles, T., Hoffman, N., & Kobb, R. (2009). Testing a home telehealth programme for US veterans recovering from stroke and their family caregivers. Disability and Rehabilitation, 31(5), 402–409. doi:10.1080/09638280802069558

- Magaña, S., & Smith, M. J. (2006). Health outcomes of midlife and aging of Latina and Black American mothers of children with developmental disabilities. Mental Retardation, 44, 224–234. doi:10.1352/0047-6765(2006)44[224:HOOMAO]2.0.CO;2

- Magaña, S., & Smith, M. J. (2008). Health behaviors, service utilization, and access to care among older mothers of color who have children with developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 46(4), 267–280. doi:10.1352/1934-9556(2008)46[267:HBSUAA]2.0.CO;2

- Manning, M. M., Wainwright, L., & Bennett, J. (2011). The double ABCX model of adaptation in racially diverse families with a school-aged child with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 320–331. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1056-1

- Marquez, J. A., & Ramírez García, J. I. (2013). Family caregivers’ narratives of mental health treatment usage processes by their Latino adult relatives with serious and persistent mental illness. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(3), 398–408. doi:10.1037/a0032868

- Marshall, J., Tanner, J. P., Kozyr, Y. A., & Kirby, R. S. (2014). Services and supports for young children with Down syndrome: Parent and provider perspectives. Child: Care, Health, and Development, 41, 365–373.

- Mayer, K. H., Bradford, J. B., Makadon, H. J., Stall, R., Goldhammer, H., & Landers, S. (2008). Sexual and gender minority health: What we know and what needs to be done. American Journal of Public Health, 98(6), 989–995. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.127811

- Medicaid Program. (2014). State plan home and community-based services, 5- year period for waivers, provider payment reassignment, and home and community-based setting requirements for Community First Choice and Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) Waivers, 42 C.F.R. Parts 430, 431, 435, 436, 440, 441 and 447.

- Narr, R. F., & Kemmery, M. (2015). The nature of parent support provided by parent mentors for families with Deaf/hard-of-hearing children: Voices from the start. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 20, 67–74. doi:10.1093/deafed/enu029

- National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) & AARP Public Policy Institute. (2015). Caregiving in the U.S. 2015. Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/caregiving-in-the-united-states-2015-report-revised.pdf

- O’Shaughnessey, C. V. (2014) The basics: National spending for Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) 2012. Retrieved from National Health Policy Forum Website https://www.nhpf.org/library/the-basics/Basics_LTSS_03-27-14.pdf

- Perkins, E. A. (2010). The compound caregiver: A case study of multiple caregiving roles. Clinical Gerontologist, 33(3), 248–254. doi:10.1080/07317111003773619

- Perlick, D. A., Straits-Troster, K., Strauss, J. L., Norell, D., Tupler, L. A., Levine, B., … Dyck, D. G. (2013). Implementation of multifamily group treatment for veterans with traumatic brain injury. Psychiatric Services, 64(6), 534–540. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.001622012

- Ramírez García, J., Hernández, B., & Dorian, M. (2009). Mexican American caregivers’ coping efficacy: Associations with caregivers’ distress and positivity to their relatives with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44, 162–170. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0420-3

- Reinhard, S., Feinberg, L. F., Choula, R., & Houser, A. (2015) Valuing the invaluable: 2015 update (Insight on the Issues 104). Retrieved from AARP Public Policy Institute website http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/valuing-the-invaluable-2015-update-new.pdf

- Sage, K. D., & Jegatheesan, B. (2010). Perceptions of siblings with autism and relationships with them: European American and Asian American siblings draw and tell. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 35, 92–103. doi:10.3109/13668251003712788

- Sallis, J. F., & Owen, N. (2002). Ecological models of health behavior. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & F. M. Lewis (Eds.), Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice (3rd ed., pp. 462–484). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- San Antonio, P., Simon-Rusinowitz, L., Loughlin, D., Eckert, J. K., Mahoney, K. J., & Ruben, K. A. (2010). Lessons from the Arkansas Cash and Counseling Program: How the experiences of diverse older consumers and their caregivers address family policy concerns. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 22(1), 1–17. doi:10.1080/08959420903385544

- Sander, A. M., Davis, L. C., Struchen, M. A., Atchison, T., Sherer, M., Malec, J. F., & Nakase-Richardson, R. (2007). Relationship of race/ethnicity to caregivers’ coping, appraisals, and distress after traumatic brain injury. Neurorehabilitation, 22, 9–17.

- Scharlach, A. E., Giunta, N., Chow, J.-C.-C., & Lehning, A. (2008). Racial and ethnic variations in caregiver service use. Journal of Aging and Health, 20(3), 326–346. doi:10.1177/0898264308315426

- Scharlach, A. E., Kellam, R., Ong, N., Baskin, A., Goldstein, C., & Fox, P. J. (2006). Cultural attitudes and caregiver service use: Lessons from focus groups with racially and ethnically diverse family caregivers. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 47(1/2), 133–156. doi:10.1300/J083v47n01_09

- Shapiro, J., Monzó, L. D., Rueda, R., Gomez, J. A., & Blacher, J. (2004). Alienated advocacy: Perspectives of Latina mothers of young adults with developmental disabilities on service systems. Mental Retardation, 42, 37–54. doi:10.1352/0047-6765(2004)42<37:AAPOLM>2.0.CO;2

- Shen, C., Smyer, M. A., Mahoney, K. J., Loughlin, D. M., Simon-Rusinowitz, L., & Mahoney, E. K. (2008). Does mental illness affect consumer direction of community-based care? Lessons from the Arkansas Cash and Counseling Program. The Gerontologist, 48(1), 93–104. doi:10.1093/geront/48.1.93

- Smith, M. E., Lindsey, M. A., Williams, C. D., Medoff, D. R., Lucksted, A., Fang, L. J., … Dixon, L. B. (2014). Race-related differences in the experiences of family members of persons with mental illness participating in the NAMI Family to Family education program. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54, 316–327. doi:10.1007/s10464-014-9674-y

- Taylor, N. E., Wall, S. M., Liebow, H., Sabatino, C. A., Timberlake, E. M., & Farber, M. Z. (2005). Mother and soldier: Raising a child with a disability in a low-income military family. Exceptional Children, 72, 83–99. doi:10.1177/001440290507200105

- Thai, J. N., Barnhart, C. E., Cagle, J., & Smith, A. K. (2015). “It just consumes your life”: Quality of life for informal caregivers of diverse older adults with late-life disability. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 1–7. doi:10.1177/1049909115583044

- Timberlake, M. T., Leutz, W. N., Warfield, M. E., & Chiri, G. (2014). “In the driver’s seat”: Parent perceptions of choice in a participant-directed Medicaid waiver program for young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 903–914. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1942-4

- Timmons, J. C., Whitney-Thomas, J., McIntyre, J. P., Butterworth, J., & Allen, D. (2004). Managing service delivery systems and the role of parents during their children’s transitions. Journal of Rehabilitation, 70, 19–26.