?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines whether election results affect the annual number of social housing contracts in Australia, focusing on the doctrines of public entrepreneurialism and public interventionism associated with political parties. Using panel data analysis of voting rates at electorate level in Queensland State, the study finds that an increase of one standard deviation in the Australian Labor Party’s (ALP) voting rate, compared to the Liberal-National Coalition, corresponds to an increase of 1.07 contracts from the mean value of 21.47. This equates to approximately a 5% increase in the number of social housing contracts managed by Queensland State. The analysis further reveals that the ALP’s voting rate has a disproportionately positive impact on the supply of social housing for indigenous communities. These findings underscore in influencing the provision of social housing and offer insightful implications for policymakers and researchers, suggesting that electoral preferences can serve as a barometer for public demand for social welfare initiatives.

Introduction

The supply of social housing is a critical issue in supporting low-income earners with housing needs. According to the OECD’s 2020 report, social housing is an essential component of both historical and future housing policies, especially in light of the escalating housing costs, sluggish income growth, and decreasing public investment in housing in across many countries. The purpose of this paper is to examine whether the supply of social housing is impacted by the election of the Labor Party vis-à-vis The Coalition in Queensland State in Australia where the political landscape is primarily divided between these two major parties.

There are two major doctrines that inform the approach to affordable housing policy and the supply of social housing: public entrepreneurialism and public interventionism. In public entrepreneurialism, governments encourage private sector agents to provide affordable housing solutions through public-private partnerships, inclusionary zoning laws, and other public value capturing instruments (Goetz, Citation2013; Mukhija et al., Citation2010). Kadi & Ronald (Citation2014, p. 274) argue that states or cities originally conforming to the ‘liberal market city’ are more likely to adopt public entrepreneurialism in providing ‘ad hoc measures to alleviate the most severe housing problems.’

In many advanced countries, such as the U.S. and those in the Europe, the housing sector has largely been shaped by market logic under the control of private investment (Preece et al., Citation2020; Waldron, Citation2019). Neoliberal policy is often considered a solution to housing problems, but it can also limit the ability of governments to maintain affordable living (Wijburg, Citation2021). For examples, in California (in Mukhija et al., Citation2010) where the state regulates developers with mandatory programs for affordable housing, also in Miami (see Wijburg, Citation2021) where negotiations between state and private property developers are at the heart, including tax incentives and other allowances in exchange for social services. Public entrepreneurship approach is said to be able to stimulate policy change and more productive for affordable housing as this approach possesses the intrinsic features of evidence-based policy (Lucas, Citation2018), i.e., innovation, scientific evidence, and alertness of opportunities, which emphasize function and applicability to public sector rather than occupation.

In contrast, states which adopt public interventionism exercise their regulatory and financial capacities to actively intervene in housing systems; through altering land use planning or reorganizing pre-existing welfare arrangements (Wetzstein, Citation2021). States or cities traditionally conforming to the ‘social-democratic city’ are more likely to adopt public interventionist strategy (Pittini et al., Citation2017; Schwartz & Seabrooke, Citation2009). This strategy is said to be more effective at increasing housing affordability when the housing market is centralized, or when the government has considerable control over land and rental sector (Harloe, Citation1995; Pittini et al., Citation2017).

Governments which adopted the public interventionist strategy to address housing problem include Amsterdam City where its policy revolved around landlord levy (Kadi & Ronald, Citation2014) and restrictive land use planning and active land bank policies (Gemeente Amsterdam 2018 cited in Wijburg, Citation2021), as well as the UK government’s Help to Buy scheme (see Berry, Citation2022), and welfare and tenancy reforms such as bedroom tax, Benefit Cap and Universal Credit, and Rent Reduction (see Preece et al., Citation2020).

Wijburg (Citation2021) contends that whether adopting public entrepreneurialism or public interventionism, state, or city governments’ capacity to maintain affordable housing governance has been lessened by the neoliberalism, where affordable housing access and production are increasingly shaped by market logics (Preece et al., Citation2020; Waldron, Citation2019), internalizing the features of the global market economy (Ward et al., Citation2019).

The Australian Labor Party (ALP) visa-vis The Coalition (a comprised of The Liberal Party and The National Party) has advocated for a proactive role for government in addressing social and economic challenges, including the supply of social housing. This approach is consistent with the principles of public interventionism, whereby the government takes a more active role in constructing and managing social housing projects directly or leveraging its regulatory power to mandate private developers to include affordable housing units in their projects. The Australian Labour Party (Citation2011, p. 162) believes that “Australia needs a strong and vibrant social housing sector to improve housing affordability for low- and moderate-income earners.” The party vis-à-vis The Coalition has advocated for a range of policies to address housing affordability, including increasing funding for social housing construction and maintenance. Many of the ALP’s policies share similarities with the Democratic party in the U.S and the Labor Party in New Zealand, which are characterized by social liberalism and can either be economically right or left (White & Nandedkar, Citation2021). The key doctrines of left-wing political parties generally prioritize equality, social justice, and collective action over individualism and free-market capitalism. Consequently, social welfare programs and public ownership and control, among others, are emphasized.

Social housing is typically defined as rental accommodation that is provided as residential at sub-market prices with the support of the government. Because social housing is characterized by sub-market prices, a purely free-market capitalist approach is insufficient to address the issue of housing policy. This is why left-wing political parties tend to be more supportive of government-initiated programs to supply social housing. Social housing may be referred to by various terms such as social or subsidized housing in countries like Australia, Canada, Germany and the United Kingdom, the public housing in Australia, United States, or general housing in Denmark, among others (OECD, Citation2020).

Against the backdrop of different doctrines surrounding social housing and the nature of social housing, which are often shaped by elected politicians, an intriguing question arises: does the outcome of election have an impact on the supply of social housing? The relationship between elections and the formation of a political party is a symbiotic one, with elections providing the platform for parties to put forward their policies and ideas, and parties shaping the political discourse and landscape. Elections are a critical component of a political party’s ability to emphasize their political policies and ideas related to housing, as they provide a platform for parties to engage with voters, present their policies and proposals, and seek support for their ideas.

Existing studies on social housing, however, is about understanding the extent and nature of social housing supply (Scanlon et al., Citation2014; Hegedüs et al., Citation2014), residualization of public housing and its impact (Hoekstra, Citation2017; Morris, Citation2015; Musterd, Citation2014), stigma for social housing residents (Jacobs et al., Citation2011), systemic barriers to social mobility for social renters (Fitzpatrick & Watts, Citation2017; Wiesel & Pawson, Citation2016); impact of social housing regulations on households and communities (Gregoir & Maury, Citation2018; Kattenberg & Hassink, Citation2017; Walker, Citation1999; Watts & Fitzpatrick, Citation2018), evaluating the cost-effectiveness of social housing provision (Chaloner et al., Citation2019), financing social housing (Lawson et al., Citation2018; Marquardt & Glaser, Citation2020; Williams & Whitehead, Citation2015), and governance of housing affordability (Berry, Citation2022; Kadi & Ronald, Citation2014; Wetzstein, Citation2021; Wijburg, Citation2021). In Australia, existing studies investigated the challenges and possibilities of local governments to impact housing affordability within their jurisdictions (Beer et al., Citation2007; Gurran et al., Citation2008; Paris et al., Citation2020).

Specifically, this paper examines whether the supply of social housing is impacted by the election of the Labor Party vis-à-vis The Coalition in Queensland State. The Australian political landscape is primarily divided between these two major parties, with The Coalition comprising of The Liberal Party and The National Party. Queensland is located along the North-East of Australia, its population has been growing particularly along the South-East QLD covering the belt between Brisbane (capital city) and Gold Coast, which leads to an increasing gap between dwelling demand and supply. Among Australia’s eight states and territories, QLD is the second largest state in terms of the number of indigenous people, hosting 28.7 percent of Australian Indigenous People.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016 Census of Population and Housing, approximately 186,482 Aboriginal, and Torres Strait Islanders reside in QLD State (equivalent to 4 percent of the QLD population), these communities are among the most socially vulnerable people. The Census data also indicates that a standardized household of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have around half of non-indigenous people’s economic resources.

Australian Elections

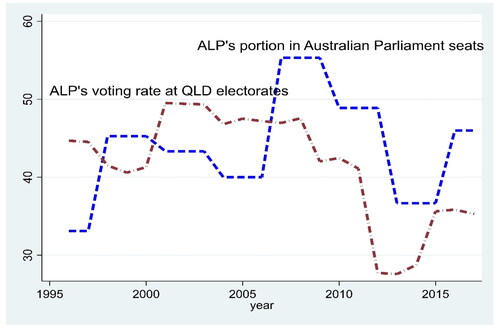

Both the ALP and the Coalition (the Liberal plus the National) have been dominant in Australian politics. Elections for the QLD State government, which are held in electorate regions, and the Australian Federal (Commonwealth) government, which is Australia nation-wide, take place once in three years, although there have been exceptional cases in the past where elections occurred in two years. During our sample period, there were eight times of elections for the QLD State government (1998, 2001, 2004, 2006, 2009, 2012, 2015 and 2017) and eight times for the Federal government (1996, 1998, 2001, 2004, 2007, 2010, 2013 and 2016). Out of the eight election years, three-year elections (1998, 2001 and 2004) were concurrent for both State and Federal governments. The number of seats in House of the Representatives for QLD State government and that for the Australian Federal government were 89 and 150 respectively with some marginal changes (see ).

Table 1. Number of seats in house of the representatives in QLD state and federal elections.

In the QLD State, the ALP and the Coalition have dominated the seats in the House of Representatives though other minor parties such as Katter’s Australian, Greens, One Nation and Independent won several seats in a particular year. Approximately 86 percent of our sample period, the ALP governed QLD State as an elected party compared to 14 percent by the Coalition party.

show that the trends in QLD State electorates and the Australian Parliament did not display consistent alignment over the duration of our sample timeframe. In contrast to the QLD State, the ALP was the elected party for the Australian Parliament (i.e., House of the Representatives for Federal government) during 27 percent of our sample period while the Coalition governed the Australian government during 73 percent of the period.

Figure 1. Portion of ALP in electorate election voting, QLD state seat, and Australian parliament. Source: prepared by authors.

Social Housing in QLD State

reports that the sum of the total number of contracts made by electorates for social housing in QLD in a particular year during our sample period was 33,413 and the sum of the number of electorates provided at least one contract in a particular year over the sample period was 1,556. The electorate-year mean value indicates that on average 21.47 number of contracts was made in an electorate for a particular year. Total number of contracts in QLD has been an increasing trend with some ups and downs over the sample period. Total number of contracts for social housing was 951 in 1996, 2597 in 2016 and 2054 in 2017. The drop of contract number in 2017 by 21 percent from the previous year was extraordinary compared to the historical trend.

Table 2. Number of social housing contracts in QLD.

Out of 88 electorates, where one electorate was dropped from the 2008 classification, most electorates provided the contract at least one until the mid-2000s. However, since then, a greater number of electorates have not supplied the contracts at all in a particular year. The total contract numbers nevertheless have shown an increasing trend because of the increase in average number of contracts in electorates where any number of contracts were made. The smaller number of electorates in more recent years, however, provided relatively a greater number of contracts than the earlier years. This trend, which is also confirmed by the increasing range and standard deviation over the time, implies the existence of heterogeneity in supply contracts among electorates and it justifies the using of panel overdispersion model for the estimation.

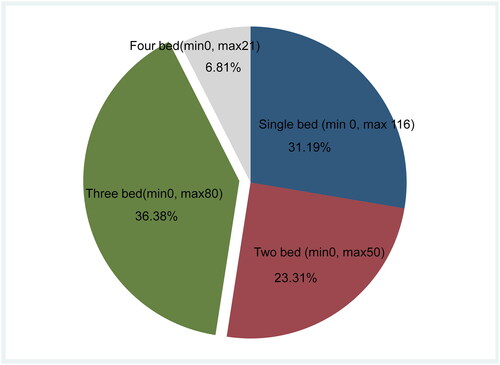

Out of the average number of contracts 21.47, the Pie chart below () shows that the portion of three bedrooms in total number of contracts was the largest with 36.38%, followed by single bed (31.19%), two bed (23.31%) and four bedrooms (6.81%). We excluded some exceptionally large dwellings with rooms numbers are five or six or seven. Over the time, contracts for single bed were most frequently observed.

Figure 2. The portion of different size of social houses in the number of contracts. Source: prepared by authors.

Over the period of time, all the different sizes of social housing showed similar patters with the total number of contracts for social housing. All of them in Graph 2 have increasing trends with some fluctuations. It also shows that the numbers of contracts for all size of social housing but four bed rooms were relatively stable until 2010 when they experienced a sharp increase. These increasing trends continued until 2016 but declined sharply in 2017.

Methodology

Source of Data and Statistics

Our database is panel data for 89 electorates in QLD over 1980-2017 period with some missing variables (refer to Appendix 1 for the list). Information about the number of total social housing contracts, assigned contracts to the vulnerable people and different sizes of the houses are not publicly published, and were obtained directly from the QLD State Government. Data on elections are hand collated using both Web-information from Wikipedia and QLD State Government (https://www.ecq.qld.gov.au/elections/election-results). Economic growth, inflation and population data are from QLD Government Website (https://www.qgso.qld.gov.au/statistics/theme/economy/economic-activity/national-accounts). The rest of the data at electorate levels such as unemployment, residence’s birthplace and level of education are from the Census of Population and Housing by the Australian Bureau of Statistics collated every five-year (https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/detailed-methodology-information/concepts-sources-methods/labour-statistics-concepts-sources-and-methods/2021/methods-four-pillars-labour-statistics/household-surveys/census-population-and-housing). As such, we filled the missing years using extrapolation from predicted values obtained by regression. The Census data provides detailed information at electorate levels. However, the consistent classification of electorate regions in QLD is available from 1996 which is the beginning year in our dataset.

Results

Baseline Estimation

Given that out response variable is the count data of contracts over multiple years for various electorates, we employ estimations through panel overdispersion models, also known as the panel negative binomial model (Hilbe, Citation2007). This model is adept at analyzing count data within a panel structure. It differs from models assuming a Poisson distribution, as the negative binomial distribution allows for overdispersion – where the variance exceeds the mean – providing flexibility when dealing with count data that shows extra variability. A key advantage of the panel negative binomial model is its capacity to accommodate heterogeneous dispersion among panels (Hilbe, Citation2007), which helps prevent inflated confidence intervals for estimated coefficients, thereby enhancing the reliability of our results.

In a random-effects overdispersion model, the dispersion is assumed to be varied randomly among panels to generate the joint probability of the count (i.e., the response variable) for a particular panel. In the fixed effects overdispersion model, the joint probability of the count for each panel is calculated conditionally upon the sums of the (observed over the years) count for the panel. presents the ALP’s voting rate and a vector of control variables. presents the baseline estimation result for patterns of elections associated with the number of social housing contracts.

Table 3. Summary statistics.

Table 4. Baseline estimation of social housing contract, RE-and FE- over-dispersion estimator.

Result in reports that ALP’s voting obtained at electorates (ALP-votingElectorate) is positively associated with the number of social housing contracts. In measurement, the effectiveness of these ALP’s voting rate and the portion are assumed to be continued until the following election. As such, our measurement of election results addresses possible lags due to construction time in supplying social housing. For control variables, we include unemployment rate, population growth at electorate level, economic growth and CPI-based inflation at QLD State level, a binary variable for the Global Financial Crisis, and a time index variable. Estimated coefficients of all these control variables are as expected though the statistical significance of GFC is somewhat sensitive to model specifications.

For the Poisson model, the marginal (i.e. partial) effect of ALP-votingElectorate measured by the slope is and this means that the marginal effects (i.e. the slopes) change with the point of evaluation

in addition to the parameter

Average marginal effect, compared to marginal effect at mean or marginal effect at a representative value, measures the averaged marginal (partial) effect on the contract number when the value of predictor (i.e., ALP’s portion in QLD seat) changes by a small margin while other covariates are set as they were observed. The calculated average marginal effects based on the random-effects model indicates that the contract number increases by between 0.33 per cent (Model 3) and 0.44 per cent (Model 2). These numbers are very similar to the estimated coefficients in our case because the magnitude of most of the estimated coefficients in absolute term are relatively small in our estimation results.

A simple averaged impact of ALP’s voting rate obtained from electorate election on the contract number across the four models in is 0.39 per cent (which is equivalent to 0.1 contracts from its mean value of 21.5). The Summary Statistics () report that ALP’s portion in QLD seat has a mean of 41.8 per cent with a standard deviation of 12.7 per cent. This means that a one-standard-deviation change in ALP-votingElectorate, which is quite possible in an election, will fluctuate the number of social housing contracts by approximately 5 per cent (=12.7*0.39%). This fluctuation is equivalent to 1.07 contracts more or less from the mean value of 21.5 contracts, depending on whether the ALP’s portion in QLD State seats increase or decrease by one standard deviation.

Results in also report that ALP’s portion in Australian House of the Representatives (ALP-in-Parliament) is negatively associated with the contract number. The estimated coefficients suggest that a one per cent point increase in ALP’s portion in the Australian Parliament seats decreases the contract numbers by between 0.78-1 percent. The table also indicates that the year when the ALP was re-elected as the winner (ALP-re-elected) is negatively associated with the number of social housing contracts.

Augmented Model

We augmented the baseline model firstly by including an interaction variable between the ALP’s voting rate at electorates and the party became consecutively from elections the winning party at QLD State government (ALPvotingElectorate*ALPre-elected). This interaction variable provides information about the partial effect of the ALP’s voting rate at electorate on the contract number as a function of ALP-re-elected and vice versa.

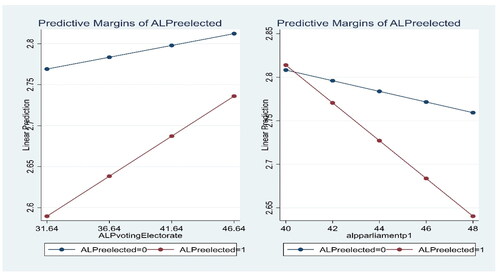

In below, Models 1 and 3 report the estimated coefficients of the interaction variable by using the RE and FE estimator respectively. The sign of the estimated coefficient of this interaction variable suggests that the positive effect of ALPvotingElectorate differs depending on whether the party was re-elected or not in a given year. The estimated coefficient of this interaction variable is positive, indicating that the positive impact of ALPvotingElectorate on the ALP's re-election is greater than when the ALP failed to be re-elected in a particular year. This is depicted by the upward sloping line on the left side of . This finding suggests that a continuation of the ALP party’s winning streak is beneficial in increasing the number of social housing contracts, in addition to winning the election in a particular year at the State level. It means that the number of social housing contracts increases with momentum, possibly due to the election results that support the party’s expansion of social housing supply when the ALP consecutively forms the governing party.

Figure 3. Changing marginal effects of the ALP’s portion in QLD state seat (Left) and the ALP’s portion in Australian parliament (Right). Source: prepared by authors.

Table 5. Estimation results with interaction variables, RE- and FE- over-dispersion estimator.

Using the estimated coefficient of the interaction between ALP’s portions in the Australian Parliament seat and Model 2 in , the right chart of shows that marginal (partial) negative effect of the ALP’s portion in the Parliament seat is less pronounced when ALP was re-elected for the QLD government than the reference years.

We continued this exercise for the number of social housings assigned to people with disabilities (Models 1-3 in ) and indigenous people (Models 4-6 in ). The results show that the election variables for indigenous people are more important determinants of the social housing assigned to people than for those with disabilities, in terms of the magnitude of the estimated coefficients (ALP-votingElectorate) and their statistical significances. The ALP’s portions in the Australian Parliament seat for those with disabilities were not statistically significant at a conventional level (Models 2-3) and were only significant by a margin (Model 1). The moderation effect by ALP-re-elected was also more pronounced in the case of the indigenous than people with disabilities. ALP’s voting rate at the electorate region (ALP-votingelectorate) is relatively more positively and consistently associated with the number of contracts for Indigenous people than for people with disabilities. Compared to the results of baseline model in above, the result of (Model 4-6) shows that the impact of elections at the electorate levels in Queensland State on the supply of social housing for Indigenous people (and the augmented effect through the ALP’s re-election) is more prominent in terms of magnitudes of the estimated coefficients and statistical significances.

Table 6. Results of RE panel overdispersion estimator for people with disabilities (Models 1-3) and indigenous people (Model 4-6).

In estimation of the socially vulnerable people on , we used the same model specification as for the baseline model. This is useful for comparison purposes. However, one may concern about confounding effects in the estimation of the coefficients since we omitted total number of disability and the indigenous people as control variables due to the absence of consistent availability of the data at electorate level.

To address this concern, we examined whether more indigenous people impact positively on the contract number by materializing the information about regions where the indigenous people reside intensively (). The 2016 Census data indicates around 38% of the indigenous people in QLD reside in Brisbane, followed by Townsville-Mackay (14.2%), Cairns-Atherton (13.1%), Rockhampton (12.1%) and Toowoomba-Roma (9.7%). To examine whether the regions where indigenous people reside intensively impacts positively on the social housing contracts allocated to the indigenous, we coded 24 electorates to reflect Brisbane, 3 electorates to Cairns-Atherton, 2 electorates to Rockhampton and 4 electorates to Toowoomba-Roma.

Table 7. RE overdispersion estimates of the impact of indigenous-intensive regions on social housing contracts assigned to indigenous people.

Results on indicate the estimated coefficients of Townsville-MacKay and Cairns-Atherton areas are positive and statistically significant at conventional level. The estimated coefficient of Rockhampton was significant at the 10 percent level. The estimated coefficient of Brisbane was not statistically significant due possibly to the offsetting effects among the included electorates. Brisbane is the largest local government in QLD covering 24 electorates and thus the estimation could be confounded (refer to Appendix 2).

To examine whether there are any different patterns of the association of the elections with the number of social housing contract, we re-run the model with the same model specifications for different sizes of the house. The size of the house ranged from single-bed to four bedrooms house after excluding five-seven bedrooms as outliers. In an unreported table, we found a positive association of ALP-votingElectorate with the contract number, this result is consistent with the baseline result in above, but it was observed only for relatively smaller size of social housings. Larger social housings (3 or 4 bedrooms) also have positive signs, but the statistical significance was not consistently observed. The negative impact of ALP-in-Parliament and ALP-re-elected was the same as the baseline result in , but this was statistically significant only for houses up to three bedrooms and not for four bedrooms. The moderation effects of ALP-votingElectorate by ALP-re-elected was observed across all the different sizes, which is consistent with the baseline result. The moderation effects of ALP-in-Parliament by ALP-re-elected was observed up to three bedrooms.

The Variance Inflation Factor test indicated that all the included variables’ VIF values were less than ten and all the election variables’ VIF ranged between one and two, suggesting multicollinearity is not a concern in our estimation. All the included covariates’ VIFs are less than 8 and the election variables ranged between 1.28 and 1.45.

Further, in unreported tables, we conducted several robustness checks. We investigated whether the estimation results are affected by the choice of outliers. Results of the estimation after dropping the year 2017 when the contract number dropped irregularly, however, confirm the same signs, indicating that the statistical significance of our main finding outlined above is robust. The result (excluding year 2017) shows a slightly smaller magnitude of the estimated coefficient in absolute terms; however, the estimated coefficients of the interaction variables became greater in absolute terms. We also used average values using data from the two closest years of Census to fill in the missing data during the Census intervals. The results are similar to our finding using the projected values from the regressions. Our panel estimation control for clustering. Further, we re-ran the model using the bootstrap method, which is equivalent to the sandwich estimator for cluster-robust standard errors (i.e., default is assumption of independence; a cluster bootstrap assumes independent between clusters but no such assumption for within a cluster), where we set 100 for the replication number and the results are consistent with the presented tables. Using the same set of covariates as in our baseline estimation for the modelling of excess zeros, we also ran the zero-inflated Poisson model and found the increased number of electorates with no contract number in recent years was not a major concern.

A remaining concern is that endogeneity issue related to the ALP’s voting rate in electorate regions. An increase in the number of social housing contracts in an electorate region may increase the ALP’s voting rate in the region. Considering that educational attainment and gender may influence party preference (Bartel, Citation2008; Huddy & Terkildsen, Citation1993; Verba et al., Citation1997), we have selected the proportion of male and female university graduates as instrumental variables. It is worth noting that Australian political parties hold varying views on immigration policy. Therefore, we have also incorporated the proportion of non-Australian births as excluded instruments. We re-ran the model using Poisson model with an instrument variable (an exponential conditional mean model). We indirectly restricted the effect of the time index by using the projections of ALP’s voting rate to ensure estimation convergence. For robustness checks, we employed both the Control Function and the GMM estimators with different combinations of excluded instruments. It was ensured that all control function estimations were based on the optimal two-step GMM. The results indicate that our main finding, as outlined above, is robust against potential endogeneity issues (results are available upon request).

Discussion and Conclusion

Our paper identified that Queensland Labor government exhibits a leftist social-liberal party with public interventionism as their approach to address housing affordability. Historically Queensland Labor’s socialism has been at work since 1915 through to 1957 when the party was in office. To counter the well-entrenched capitalism in the state, QLD Labor aggressively established State-Owned Enterprises to make the capitalist society become benign (Thornton, Citation1986), while at the same time actively sought to promote home ownership through programs such like the Workers’ Dwellings and Workers’ Homes schemes by offering fixed interest and low start loans to public housing tenants (Hollander, Citation1995). In the 2000s, the State Housing Amendment Bill provided the Queensland Housing Commission with the authority to offer various loan arrangements to assist tenants who applied to buy housing commission property (Queensland Parliamentary Library, Citation2000). The more recent housing affordability program is the Housing Investment Fund (HIF) initiated by the Queensland Labor government to provides subsidies and one-off capital grants to encourage developers, tenancy managers, retirement funds, and other stakeholders to partner to develop, finance and operate additional social and affordable housing supply in Queensland, especially those vulnerable groups such as the homeless, people escaping domestic violence, First Nations people, and people with disability (Queensland Government, Citation2023).

Since the 1980s and 1990s, the public housing sector in many countries began to experience major shift from a social welfare-oriented regime into a neo-liberal regime, yet in some countries public intervention continued, rather than diminished. In the UK since 1980, the “Right to Buy” program, which increased the level of occupier ownership from 54% in 1979 to 67% in 1990 (Queensland Parliamentary Library, Citation2000). In more recent years, London Living Rent has been introduced to provide some 116,000 new affordable homes (Greater London Authority, Citation2016). Berlin offered low home-ownership rates and conservative lending standards (Marquardt & Glaser, Citation2020; Schneider & Wagner, Citation2016). The Amsterdam government intervened through land use designations, tenure requirements for new housing production, and buying back programs of former public housing estates (Wijburg, Citation2021). These governments adopted policies to stimulate the owner-occupier sector (Musterd, Citation2014); while part of the public housing stock was also shifted into private market for rentals (Kamerbrief Woonvisie, 2011, as cited in Musterd, Citation2014; Priemus, Citation2004). Studies have found that public housing system in the UK and Amsterdam has faced increasing problems of residualization and social spatial segregation (Hoeskstra, Citation2017; Murie, Citation1998; Musterd et al., Citation2016; van Ham & Manley, Citation2012) due to unregulated stock in the private rental market, and public housing tenants whose income had risen substantially but did not vacant the dwelling (Musterd, Citation2014).

Given the increasing spread of housing financialization and commodification, literature also pointed out that public interventionism has potential to erode access to social housing for those perceived as a financial risk. As studied by Preece et al. (Citation2020), the increasing use of affordability assessments in the UK has led to increasing conditionality and limiting access to social housing. Similarly, accessibility to housing in Amsterdam has been significantly limited. Following the market-based housing reforms in the 1990s and the reconstitution of social housing as a safety net promoted by the EU since 2008, a larger share of units in Amsterdam have been under direct market influence (Kadi & Ronald, Citation2014). Private sector housing production requires land use restriction to be relaxed, hence the City is forced to re-negotiate its affordability requirements to meet the needs of housing supply (Wijburg, Citation2021). The governments in the UK, Amsterdam, and Berlin face diminishing legitimacy not only in supplying new housing but also in reserving public housing for those in need, indicating the ineffectiveness of public interventionism as housing policy is increasingly market oriented.

In contrast, Vienna is argued to have a more successful housing system in Europe than Berlin, Amsterdam, and the UK. The Vienna’s government creates an effective institution to attract participation of social and private actors, involving three elements: public housing provided by the municipality, housing provided by limited-profit housing associations (LPHAs) and various private providers receiving public subsidies (Marquardt & Glaser, Citation2020). All elements are bound to common interest to secure the provision of affordable housing. The effectiveness of public interventionism in Vienna is due to the government’s commitment to de-commodify the public housing sector while proactively involving private stakeholders through subsidies. Indeed, the private sector increases commitment to affordable housing when it recognizes its relevance to their self-interest (Sassen, Citation2014). This government commitment and proactive approach can be compared to Queensland case in this paper, where the government provides real incentives to attract stakeholders to achieve social policy goals as shared rights and responsibilities.

Our research indicates a correlation between the Australian Labour Party’s (ALP) increased voting rate over the Liberal-National Coalition and a rise in social housing contracts. This trend is particularly evident when the ALP achieves consecutive election victories. An analysis of the data from reveals that the average impact of the ALP’s voting rate from electorate elections on the number of contracts is 0.39%. This translates to an average change of 0.1 contracts from the mean value of 21.47. The statistical table reports that the ALP’s share in the Queensland (QLD) seat averages 41.81%, with a standard deviation of 12.71%. Consequently, a one-standard-deviation shift in the ALP’s electorate voting rate—a plausible scenario during elections—could result in a 5% fluctuation in the number of social housing contracts. This equates to an increase or decrease of approximately 1.07 contracts from the mean, contingent on whether the ALP’s share in QLD State seats rises or falls by one standard deviation.

Our paper argues that Queensland outperforms other Australian states in public housing provision for two primary reasons: firstly, nearly 50 per cent of local governments in Queensland are directly involved in housing provision, actively participating in the design and development of policies and strategies (LGAQ, Citation2014, p. 3). Unlike other states, Queensland local governments are not only acknowledging housing affordability issues but are also actively engaged in policy development and implementation. This engagement is supported by financial assistance and training from federal and state governments, empowering local stakeholders to address community needs effectively (LGAQ, Citation2014, p.8). In contrast, local governments in NSW and Victoria recognize the affordability problems but often refrain from action, citing the absence of housing targets and the perception that housing is a federal or state responsibility (Morris et al., Citation2020). This reluctance underscores the significance of Queensland’s approach, where local governments act as providers or major shareholders in social housing, thereby directly influencing the supply and quality of affordable housing.

Secondly, the governance of Queensland’s public housing sector reflects a leftist social-liberal perspective, prioritizing the affordability for vulnerable groups. The state’s interventionist approach, which includes constructing and managing social housing projects and incentivizing stakeholder partnerships, is a testament to its commitment to increasing affordable housing supply despite resource constraints (Brown, Citation2007). Our longitudinal analysis of election results from 1980 to 2017 further supports the claim that political ideology plays a critical role in public housing governance. The increase in Australian Labour Party’s voting rate over the Liberal-National Coalition correlates with a rise in social housing contracts, particularly when the ALP secures consecutive election victories. In Australia, social housing is primary managed by state governments rather than the federal government. In Queensland State, the Department of Communities, Housing and Digital Economy is responsible for constructing, allocating public and community housing to eligible individuals and families. The Australian Labor Party being the dominant governing party in office and in the majority of electorate regions during the sample period has effectively increased social housing supply while allocation of housing was in favor of the socially vulnerable people. Over time, the number of social housing contracts has increased from a total of 951 contracts in 1996, to 2,597 contracts in 2016. A sharp increase in demand occurred from 2010 to 2016 for all sizes except 4-bedroom dwellings. The average number of social housing contracts per electorate region is 21.47 annually, mainly focusing on single bed to 4-bedroom houses, excluding 5–7-bedroom houses. From this average (21.47), 11.42 contracts were allocation to people with disability, and 3.5 to indigenous people (aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders). 69.5 per cent of the total social housing contracts were assigned to socially vulnerable group (53.18 per cent people with disability, and 16.33 per cent Indigenous people).

Reviewing the approach by the Australian Coalition, which has been dominating the Australian electoral successes between 1996 and 2017, the government seems to fall short of its promise regarding social housing. During the Howard era of leadership (1996 – 2007), neglect of the social housing sector saw social housing stocks dropped from 6.1 per cent (1995-96) of overall housing stock to 4.7 per cent (2005-2006) (Morris, Citation2021). More recently, the NSW Coalition government sold over AUD3.5billion social housing assets during it decade of rule (2013-2022), and only supplied 10 per cent of promised new stock (McGowan, Citation2022). The total increase tallied to 7,515 dwellings (approx. 1,100 annually). Moreover, despite wide-sector urging of the ruling Coalition ‘to use the construction of social housing to counter the Covid-19 induced recession, the government refused to countenance the suggestion’ by claiming social housing is a state responsibility (Morris, Citation2021). In contrast, the ALP is reported to increase social housing stock during its leadership tenure (2007-2013) by 30,000 dwellings (Morris, Citation2021).

Election results matter in housing governance because elected politicians determine the housing policy at local level, and the economic view and political ideology of the elected politicians will shape the planning, development, and implementation of policy. Political parties represented by economically left-wing with social-liberal ideology tend to frame housing crisis as affordability rather than supply issue (White & Nandedkar, Citation2021). The Queensland ALP (Australian Labor Party) has tended to approach public housing issue from this lens, viewing housing crisis as social problem rather than government sole responsibility, as a result, different policy solutions are required, including involvement of local government, councils, and private agents as partners for resources and viable solutions. On the contrary, land supply rationality is a dominant frame of housing problem adopted by Social Conservatism that often is economically right view (White & Nandedkar, Citation2021). The Australian Coalition holds similar view, where public housing supply is determined by supply of land and the solution is freeing-up more land and reducing red-tape to improve efficiency for market mechanism.

Our findings contribute to the understanding of public housing governance, emphasizing the influence of a government’s economic perspective and political ideology on affordable housing policy. To enhance the effectiveness of the public housing system amidst evolving economic dynamics, our research suggests that incorporating local government involvement alongside a spectrum of political perspectives can enhance outcomes within public housing. Our paper suggests a reevaluation of government roles and responsibilities across tiers, highlighting the importance of political will and innovation in the public sector to prioritize housing policies that emphasize use value alongside economic considerations. Addressing market commodification within the public housing sector necessitates both proactive action and a strong commitment from the government.

Our study has practical and theoretical shortcomings. Firstly, it does not address several important factors that also impact housing policy effectiveness, such as housing quality, location, accessibility, and the social and economic desegregation of neighborhoods. These factors are essential considerations that warrant further investigation and analysis in future studies to provide a more comprehensive understanding of effective housing policies.

Furthermore, there is a lack of ideological uniformity within the Labor Party which limits the generalizability of our study’s conclusion. As noted in the paper (p. 21), Victoria, arguably the most Labor-friendly state in Australia by various measures, does not place a high priority on affordable housing provision due to perceiving this responsibility as primarily federal rather than state. This highlights the contextual complexities that may affect the applicability of our findings across different political landscapes within Australia.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the valuable comments from an anonymous reviewer and the editor, Kimberly Goodwin, during the revision process. The usual disclaimer applies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Australian Labour Party. (2011). National platform. Authorized by George Wright.

- Bartel, L. M. (2008). Unequal democracy: The political economy of the new gilded age. Princeton University Press.

- Beer, A., Kearins, B., & Pieters, H. (2007). Housing affordability and planning in Australia. Housing Studies, 22(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030601024572

- Berry, C. (2022). The substitute state? Neoliberal state interventionism across industrial, housing and private policy in the UK. Competition & Change, 26(2), 242–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529421990845

- Brown, A. J. (2007). Federalism, regionalism and reshaping Australian governance. In A. J. Brown & J. Bellamy (Eds.), Federalism and regionalism in Australia: New approaches, new institutions? (pp. 11–32). ANU Press.

- Chaloner, J., Colquhoun, G., Pragnell, M. (2019). Increasing investment in social housing: Analysis of public sector expenditure on housing in England and social housebuilding scenarios, London: Capital Economics. https://assets.ctfassets.net/6sxvmndnpn0s/4MyjTqJ7WcqcwJIcOa5ybB/025ce96b7a5fe550f6bac5d59b58a6bb/Capital_Economics_Confidential_-_Final_report_-_25_October_2018.pdf

- Fitzpatrick, S., & Watts, B. (2017). Competing visions: Security of tenure and the welfarisation of English social housing. Housing Studies, 32(8), 1021–1038. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1291916

- Foundation Jean-Jaurès. (2019). History of Australian labour party. YouTube video, 23, 12. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5dMq7VlGozg

- Goetz, E. G. (2013). The audacity of HOPE VI: Discourse and the dismantling of public housing. Cities, 35, 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.07.008

- Greater London Authority. (2016). Homes for Londoners: Affordable homes programme 2016-21 funding guidance. City Hall, Greater London Authority.

- Gregoir, S., & Maury, T. (2018). The negative and persistent impact of social housing on employment. Annals of Economics and Statistics, 130, 133–166. https://doi.org/10.15609/annaeconstat2009.130.0133

- Gurran, N., Ruming, K., Randolph, B., & Quintal, D. (2008). Planning, government charges, and the costs of land and housing. Australian Housing and Urban Research Positioning Paper Series, (109), 1–93.

- Harloe, M. (1995). The people’s home? Social rented housing in Europe and America. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hegedüs, J., Lux, M., Sunega, P., & Teller, N. (2014). Social housing in post-socialist countries. In K. Scanlon, C. Whitehead, M. Fernández Arrigoitia (Eds.), Social housing in Europe (pp. 239–253). Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118412367.ch14

- Hilbe, J. M. (2007). Negative binomial regression. Cambridge University Press.

- Hoekstra, J. (2017). Reregulation and residualization in dutch social housing: A critical evaluation of new policies. Critical Housing Analysis, 4(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2017.4.1.322

- Hollander, R. (1995). Every man’s right’: Queensland labor and home ownership 1915–1957. Queensland Review, 2(2), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/S132181660000088X

- Huddy, L., & Terkildsen, N. (1993). Gender stereotypes and the perception of male and female candidates. American Journal of Political Science, 37(1), 119–147. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111526

- Jacobs, K., Arthurson, K., Cica, N., Greenwood, A., Hastings, A. (2011). The stigmatisation of social housing: Findings from a panel investigation, AHURI Final Report No. 166. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/166

- Kadi, J., & Ronald, R. (2014). Market-based housing reforms and the ‘right to the city’: the variegated experiences of New York, Amsterdam and Tokyo. International Journal of Housing Policy, 14(3), 268–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2014.928098

- Kattenberg, M., & Hassink, W. (2017). Who moves out of social housing? The effect of rent control on housing tenure choice. De Economist, 165, 43–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-016-9286-z

- Lawson, J., Pawson, H., Troy, L., Nouwelant, R., Hamilton, C. (2018). Social housing as infrastructure: An investment pathway, AHURI Final Report No. 306 (Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited). https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/306

- Local Government Association of Queensland (LGAQ). (2014). Senate standing committee on economics – inquiry into affordable housing. Local Government Association of Queensland. Submission 196 (31 March 2014).

- Lucas, D. S. (2018). Evidence-based policy as public entrepreneurship. Public Management Review, 20(11), 1602–1622. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1412115

- Marquardt, S., & Glaser, D. (2020). How much state and how much market? Comparing social housing in Berlin and Vienna. German Politics, 32(2), 361–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2020.1771696

- McGowan, M. (2022). More than $3bn of social housing sold by NSW government since Coalition took power, The Guardian, April 16. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/apr/16/more-than-3bn-of-social-housing-sold-by-nsw-government-since-coalition-took-power

- Morris, A. (2015). The residualisation of public housing and its impact on older tenants in inner-city Sydney, Australia. Journal of Sociology, 51(2), 154–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783313500856

- Morris, A. (2021). Isn’t it time the federal government stepped up on social housing and its implications, The Fifth Estate, September 28. https://thefifthestate.com.au/columns/spinifex/isnt-it-time-the-federal-government-stepped-up-on-social-housing-and-its-implications/

- Morris, A., Beer, A., Martin, J., Horne, S., Davis, C., Budge, T., & Paris, C. (2020). Australian local governments and affordable housing: Challenges and possibilities. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 31(1), 14–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304619880135

- Mukhija, V., Regus, L., Slovin, S., & Das, A. (2010). Can inclusionary zoning be an effective and efficient housing policy? Evidence from Los Angeles and Orange Counties. Journal of Urban Affairs, 32(2), 229–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2010.00495.x

- Murie, A. (1998). Segregation, exclusion and housing in the divided city. In S. Musterd & W. Ostendorf (Eds.), Urban segregation and the welfare state: Inequality and exclusion in Western cities (pp. 110–125). Routledge.

- Musterd, S. (2014). Public Housing for Whom? Experiences in an Era of Mature Neo-Liberalism: The Netherlands and Amsterdam. Housing Studies, 29(4), 467–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.873393

- Musterd, S., van Gent, W., & van Ham, M. (2016). Changing welfare context and income segregation in Amsterdam and its metropolitan area. In T. Tammaru, S. Marcińczak, & S. Musterd (Eds.), Socio-economic segregation in European capital cities: East meets West (pp. 55–79). Routledge.

- OECD. (2020). Social housing: A key part of past and future housing policy, employment, labour and social affair policy briefs. Paris: OECD. http://oe.cd/social-housing-2020

- Paris, C., Beer, A., Martin, J., Morris, A., Budge, T., & Horne, S. (2020). International perspectives on local government and housing: The Australian case in context. Urban Policy and Research, 38(2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2020.1753690

- Pittini, A., Koessl, G., Dijol, J., Lakatos, E., Ghekiere, L. (2017). The state of housing in the EU 2017. Brussels: Housing Europe. https://www.housingeurope.eu/file/614/download

- Preece, J., Hickman, P., & Pattison, B. (2020). The affordability of “affordable” housing in England: Conditionality and exclusion in a context of welfare reform. Housing Studies, 35(4), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1653448

- Priemus, H. (2004). Dutch housing allowances: Social housing at risk. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28(3), 706–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00545.x

- Queensland Government. (2023). Housing investment fund. Department of communities, housing and digital economy. https://www.chde.qld.gov.au/about/initiatives/housing-investment/housing-investment-fund

- Queensland Parliamentary Library. (2000). Public housing in Queensland: State housing amendment bill 2000, Research Brief 1/100. Queensland Parliament House.

- Sassen, S. (2014). Expulsions: Brutality and complexity in the global economy. Harvard University Press.

- Scanlon, K., Fernández Arrigoitia, M., & Whitehead, C. (Eds.). (2014). Social housing in Europe . Wiley-Blackwell.

- Schneider, M., Wagner, K. (2016). Housing markets in Austria, Germany and Switzerland. In The Narodowy Bank Polski Workshop: Recent Trends in the Real Estate Market and Its Analysis - 2015 Edition. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2841641

- Schwartz, H. & Seabrooke, L. (eds.) (2009). The politics of housing booms and busts. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Thornton, H. J. (1986). Socialism at work? Queensland labor in office, 1915-1957. Doctoral dissertation 1986.

- van Ham, M., & Manley, D. (2012). Neighbourhood effects research at a crossroads. Ten challenges for future research. Environment and Planning A, 44(12), 2787–2793. https://doi.org/10.1068/a45439

- Verba, S., Burns, N., & Schlozman, K. L. (1997). Knowing and caring about politics: Gender and political engagement. The Journal of Politics, 59(4), 1051–1072. https://doi.org/10.2307/2998592

- Waldron, R. (2019). Financialization, urban governance and the planning system: Utilizing 'development viability’ as a policy narrative for the liberalization of Ireland’s post-crash planning system. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43(4), 685–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12789

- Walker, R. M. (1999). The housing problems of employees: Housing markets, policy issues and responses in England. Netherlands Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 14(2), 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02496819

- Ward, C., Van Loon, J., & Wijburg, G. (2019). Neoliberal europeanisation, variegated financialisation: Common but divergent economic trajectories in the Netherlands, United Kingdom and Germany. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 110(2), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12342

- Watts, B., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2018). Fixed term tenancies: Revealing divergent views on the purpose of social housing. Heriot-Watt University.

- Wetzstein, S. (2021). Assessing post-GFC housing affordability interventions: A qualitative exploration across five international cities. International Journal of Housing Policy, 21(1), 70–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2019.1662639

- White, I., & Nandedkar, G. (2021). The housing crisis as an ideological artefact: Analysing how political discourse defines, diagnoses, and responds. Housing Studies, 36(2), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1697801

- Wiesel, I., & Pawson, H. (2016). Why do tenants leave social housing? Exploring residential and social mobility at the lowest rungs of Australia’s socioeconomic ladder. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 50(4), 397–417. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2015.tb00357.x

- Wijburg, G. (2021). The governance of affordable housing in post-crisis Amsterdam and Miami. Geoforum, 119, 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.12.013

- Williams, P., & Whitehead, C. (2015). Financing affordable social housing in the UK; building on success? Housing Finance International, 14–19. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/63399/

Appendices

Appendix 1. List of electorates in Queensland

Appendix 2. Lists of Local Government Areas (LGA) covering multiple electorates