?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We investigate the relationship between homeownership and life as well as housing satisfaction. Following several studies, we confirm the positive relationship between housing satisfaction and homeownership using panel data from Germany. Contrary to most of the literature, we find no positive significant effects of a home purchase on life satisfaction in the long-term. Analyzing short-term effects in an event-study design, we show that both life and housing satisfaction anticipate the acquisition and adapt shortly after. Debt-free buyers, however, do not experience anticipation or adaptation effects at all. Comparing outright homebuyers to debt-financing owners, we show that having a real estate loan affects homeowners’ life satisfaction negatively. The larger the mortgage burden relative to the household income and the last rent paid, the larger is the negative effect on life satisfaction. We conclude that the mortgage burden of a home purchase can offset the positive effect of homeownership.

Introduction

Many positive qualities are attributed to owning a self-occupied home. Homeownership affects households’ wealth and social capital but also the urban environment and land use (Dietz & Haurin, Citation2003; DiPasquale & Glaeser, Citation1999; Engelhardt et al., Citation2010; Rossi & Weber, Citation1996). On top of that, homeownership has effects on individual behavior like fertility, children’s educational and productive outcomes, and subjective well-being (SWB) (Boehm & Schlottmann, Citation1999; Green & White, Citation1997; Mulder & Billari, Citation2010; Rohe & Stegman, Citation1994). SWB is a meaningful measure to evaluate policy interventions and has become a popular concept in housing research (Clapham et al., Citation2018; Kahneman & Krueger, Citation2006).

Homeownership has been found to be positively correlated with SWB in many studies. Most early studies, however, fail to estimate a causal effect of homeownership on SWB or other outcomes. This is due to the endogenous choice of housing tenure which is conditional on many observable and unobservable factors. In response to Green and White (Citation1997), Aaronson (Citation2000) shows that most of the beneficiary effect of homeowning is driven by partly unobservable family characteristics.

In more recent literature, Diaz-Serrano (Citation2009) estimates a causal impact of homeownership on housing satisfaction with the self-occupied dwelling (Diaz-Serrano, Citation2009) by looking only at households having bought the dwelling in which it already resided as a renter. This effect might be due to a different perception of the housing amenities when the home is owned, not rented (Stotz, Citation2019). Moreover, owning a home may lead to higher self-esteem, a pride of ownership, a feeling of security, and a self-perception of having successfully entered the “next level” in the life cycle (Rohe & Stegman, Citation1994). These factors may explain why ownership has a positive effect on SWB. Recent literature, however, has shown that SWB anticipates certain life cycle events such as marriage, unemployment, or home purchase and adapts to a lower level shortly after events (Clark et al., Citation2008; Clark & Diaz-Serrano, Citation2023; Clark & Georgellis, Citation2013; Qari, Citation2014).

In the present article, we make use of a long longitudinal dataset with which we can observe changes in the tenure status such that we can estimate the effect of becoming a homeowner in a sample with only owners-to-be. Homeowners and renters differ in almost all present variables and probably also in many unobservable such as personal values, family background or wealth. To minimize a potential omitted variable bias, we restrict our sample to individuals who experience the transition from renting to owning a home (). Hence, we estimate the effect of becoming a homeowner.

Table 1. Summary table.

Finally, (debt-financed) homeownership could be a heavy financial burden which in turn may affect SWB negatively (van Praag et al., Citation2003). As housing prices increase in almost every industrialized country, the financing amount and hence the financial burden increases. In addition to the monthly annuities for the real estate loans, the financial obligations include maintenance and repair costs and costs for outdoor amenities. Thus, the decision to purchase a home is associated with high and rising financial obligations which could counteract the positive influence of homeownership on SWB (Smith et al., Citation2017; Tharp et al., Citation2020).

These two opposing effects raise the question of whether the commonly diagnosed positive relationship still holds considering indebted and outright homebuyers in an event-study design. Using data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) from 1984 to 2018, the present article examines (i) the relationship between owning a home and life as well as housing satisfaction, (ii) the effect of a debt-financed home purchase on both mentioned satisfaction domains, and (iii) finally the temporal effects of both, (i) and (ii), in an event-study design.

Our contribution is threefold: First, unlike existing research, we explicitly take the financial burden of a mortgage into account while simultaneously analyzing the temporal effects. Second, aiming for statistical power, we analyze the relationships between homeownership, mortgage and SWB using one of the longest available panel datasets. Third, targeting a within comparison of home-buying individuals (and not a between tenure status comparison), we exclude individuals that do not change their tenure status during the observational period from our analysis. We think that we can hereby rule out a potential omitted variable bias that adheres to most existing studies. Nevertheless, we do not claim a causal inference throughout the analysis (for a discussion on the endogeneity of the choice of housing tenure see Data and Empirical Strategy section).

We find no significant long-term effect of being a homeowner on life satisfaction but do find a strong positive effect on housing satisfaction. Considering the temporal effects of the home purchase, we find significantly lower but increasing levels of life satisfaction before the purchase that culminate in the highest life satisfaction level in the year of the purchase. After the purchase, life satisfaction adapts again to a lower level and ends up more than six years after the purchase at approximately the same level as it had been more than 5 years before the tenure change. Regarding housing satisfaction, we estimate anticipation effects which anticipate the lowest level of housing satisfaction in the year before the purchase. After the purchase, housing satisfaction increases by more than 10 percentage points and adapts to a certain, lower level. Even more than six years after the transition to an owner, the satisfaction level is still significantly above the level of five or more years before.

Further, we provide evidence that the financing method, either credit-financed or outright, moderates the effects on SWB. Buying a home with a mortgage decreases life satisfaction compared to outright buyers. Similarly, we estimate negative effects on life satisfaction with increasing debt-to-income payments. This effect seems to be driven by mortgage repayments, specifically by the difference between the loan repayment burden and the last rent burden, and not by maintenance costs.

Outright buyers do not experience any changes in life satisfaction due to the tenure change nor any anticipation or adaptation effects. Regarding housing satisfaction, outright buyers do not anticipate the home purchase but experience a significant increase in the years following the purchase. Hence, we conclude that debt-free buyers do not adapt their housing satisfaction and consistently gain from being a homeowner. Debt-financed buyers anticipate and adapt their housing satisfaction and experience a higher increase in housing satisfaction than outright buyers in the long-term. We conclude that the positive effects of owning a self-occupied home are outweighed by the financial burden.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. We derive rationales from a literature review on the relationship between homeownership and financial burden with life and housing satisfaction, respectively. In the third section, we describe the data and elaborate on our empirical strategy to test our hypotheses. We then discuss our results before we draw our conclusions in the end.

Literature Review

Homeownership and Life Satisfaction

Life and housing satisfaction are both results of a cognitive evaluation process comparing the best/worst possible situation of living/housing with the current one (Diener, Citation1984; van Praag et al., Citation2003). Usually, respondents are asked to indicate their satisfactions on a Likert scale (see Data & Empirical Strategy Section).

Early empirical literature finds mostly small positive significant effects of homeownership on life satisfaction (Rohe & Basolo, Citation1997; Rohe & Stegman, Citation1994; Rossi & Weber, Citation1996). Contrarily, using more recent econometric methods, Bucchianeri (Citation2009) does not find any significant effect of homeowning either on life satisfaction or emotional well-being. Although the sample is of high quality and the author includes many covariates, the analysis still lacks a temporal aspect and has a relatively small sample size.

Zumbro (Citation2014) and Seiler Zimmermann and Wanzenried (Citation2019), use longer panel datasets from Germany and Switzerland, respectively, and find significant positive effects of homeownership on life satisfaction. Ruprah (Citation2010) finds evidence for a positive effect in most Latin American countries, while Latif (Citation2021), in contrast, estimates a negative effect of homeownership on life satisfaction of individuals with low income. Using the cross-country dataset of SHARE which surveys adults over 50 years in several European countries, Herbers and Mulder (Citation2017) show for the year 2012 that older tenants have a significantly lower SWB than same-age homeowners.

Using data from the Chinese Household Finance Survey from 2011, Zhang and Zhang (Citation2019) show that the positive relationship between owning a home and SWB is mostly driven by an increase in wealth.

While most of the studies find positive effects, the quality of the studies in terms of the observational period of the data or the methodological strategy leaves room for further investigations. One main reason why the findings are fuzzy could lie in the fact of different attitudes on being a renter or an owner in different countries. The cultural embeddedness of homeownership seems to be a large factor in how life satisfaction is influenced by tenure status (Fong et al., Citation2021; Kemeny, Citation2001). In countries with a well-developed rental sector and tenant protections, renting seems to be as opportune as owning a home (Voigtländer, Citation2009). Compared to renting societies, homeownership in homeowning-societies seems to have a larger effect on life (Elsinga & Hoekstra, Citation2005).

Apart from the geographically spread cultural embeddedness of homeownership, we see at least three other reasons why homeownership might not substantially impact life satisfaction:

According to the livability theory (Veenhoven, Citation2010; Veenhoven & Ehrhardt, Citation1995), an individual’s life satisfaction depends on their need for gratification which again depends on external living conditions (and their inner abilities to use them). If an individual perceives homeownership as a basic need, he or she should expect a high gain in life satisfaction. The actual increase in well-being might be small as the change from being a renter to an owner might be influenced by the law of diminishing returns. While the basic needs are satisfied, the additional utility of owning a home might be small. The perceived discrepancies between the actual utility gains and the expected ones influence subjective well-being negatively (Michalos, Citation1985, Citation2008). One reason for this could be that individuals overestimate the future emotional gains of the “achievement” of homeownership – that is, they overweight the benefits from extrinsic or materialistic goods (such as homeownership) (Odermatt & Stutzer, Citation2022; Reid, Citation2013; Ronald, Citation2008). By investigating tenants who buy their dwellings, Diaz-Serrano (Citation2009) provides evidence for the relevance of unfulfilled expectations regarding homeownership.

The second reason why subjective well-being might not be affected by homeownership comes from the Social Comparison Theory. Diener et al. (Citation1993) find that the SWB gains from a higher income do not depend on the absolute height of the income but rather on the relative income of the observed region. Having bought a home led to a perceived step upward in social status. The Social Comparison Theory states that individuals assess their SWB according to their peer group. Homeownership can thus initially mean socioeconomic or (perceived) sociometric advancement, as one either gains a material advantage within one’s social group (“local-ladder effect”) or catches up with existing wealth within the group (all others already have homeownership) (Anderson et al., Citation2012). However, this is a zero-sum game: If a homeowner is the first to be a homeowner among their peers, it causes negative externalities. On the other hand, if all the peers are already homeowners, obtaining homeownership is simply catching up with others. In line with this, Clark (Citation2003) and Powdthavee (Citation2005) show that negative events such as becoming unemployed, or a victim of a crime do affect one’s well-being less when peers experience the same. New homeowners compare themselves to other homeowners and not to other renters anymore. As these two groups are different in many aspects (see ), homeowners have on average a higher socioeconomic status. Hence, new homeowners might not experience large gains in SWB.

The third and – at least in the intersection between the real estate and SWB literature – most prevalent theory is the baseline hypothesis which states that the SWB anticipates important events in life, e.g., unemployment, marriage, divorce, or the birth of a child. Similarly, the SWB adapts after the event back to the baseline level (Clark et al., Citation2008; Clark & Georgellis, Citation2013; Lucas, Citation2007; Qari, Citation2014).

Homeownership and Housing Satisfaction

Considering housing satisfaction, the theoretical and empirical evidence is unambiguous. Being a homeowner leads to significant gains in housing satisfaction in at least two ways. First, a home purchase is usually associated with high attention towards the new home in the following periods after the purchase. This positive attention effect decreases over time (Kahneman & Thaler, Citation2006). Stotz (Citation2019) empirically shows that the positive effect for owners decreases in the long run but remains positive compared to renters. In a recent study, Clark and Diaz-Serrano (Citation2023) find that the gain in housing satisfaction is three times larger for renters who buy and move to a new home compared to renters who buy the dwelling in which they already live. This finding might foster the evidence for the attention hypothesis.

Secondly, homeownership itself is a housing satisfaction driver. After all, Clark and Diaz-Serrano (Citation2023) and Stotz (Citation2019) find a significant effect of tenure status on housing satisfaction. Diaz-Serrano (Citation2009) concludes that the housing satisfaction of renters who become homeowners increases regardless of the housing context and whether they geographically move or not. Elsinga and Hoekstra (Citation2005) examine the European Community Household Panel and find in almost all considered European countries a significant positive relationship between ownership and housing satisfaction. These findings support Saunders (Citation1990), who argues that there is a preference in human nature for a defined area of one’s own. Thus, this second effect can simply be referred to as the “ownership effect.”

Financial Burden and SWB

Tharp et al. (Citation2020) find a positive relationship between homeownership and satisfaction with the financial situation. On an 11-point Likert scale, they estimate a significant increase of 0.41 points due to the tenure change. At the same time, having a mortgage negatively affects financial satisfaction (-0.18 points). As financial satisfaction is an important explanatory domain of life satisfaction (van Praag et al., Citation2003), the conclusion that having a mortgage might negatively impact life satisfaction seems evident. A mortgage seems to be a financial stressor that negatively affects financial and life satisfaction (Smith et al., Citation2017). On the other hand, a mortgage is usually a necessity to buy a home. Therefore, having a mortgage enables the individual to experience a positive increase in housing satisfaction which in turn positively affects life satisfaction (Diener et al., Citation2017).

Examining data from the Health and Retirement Study from the USA, Loibl et al. (Citation2022) find support for both views. Investigating individuals aged 62 and older, they show that unsecured financial debts lead to more financial stress. Contrarily, mortgage debt does not affect financial stress even though it restricts financial opportunities. Herbers and Mulder (Citation2017) provide evidence for a strong negative association between elderly mortgage holders and their life satisfaction. Hence, we assume that the negative effect of a mortgage overweights the potential positive effects of housing satisfaction on life satisfaction. Accordingly, individuals who can buy their home outright should experience a larger gain in life satisfaction than debt-financing buyers. For both types, we should see anticipation and adaptation effects.

Contrarily, debt-financing buyers should experience the same effect as outright buyers since there is no reason why the financing type has a direct impact on housing satisfaction.

The more individuals spend on their homes, the higher their aspiration and commitment to the home which could lead to higher housing satisfaction. At the same time, the financial burden is higher which should negatively affect life satisfaction. According to the mentioned studies, we suppose that the mortgage of an owner-occupied home is a burden on SWB such that we focus on this potential negative factor in the following empirical analysis.

Data and Empirical Strategy

Data Description

We use the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) (Goebel et al., Citation2019) which is an annual survey that is representative of the German population. Conducted since 1984, each year on average approximately 12.000 households with 25.000 individuals are surveyed. The SOEP contains among others a wide range of (socio-)demographic, economic, and psychological variables. For our sample, we use all 35 waves from 1984 to 2018. Before 1990, the survey was conducted only in West Germany. The first wave of surveys in East German states started in the year of the reunification in 1990.

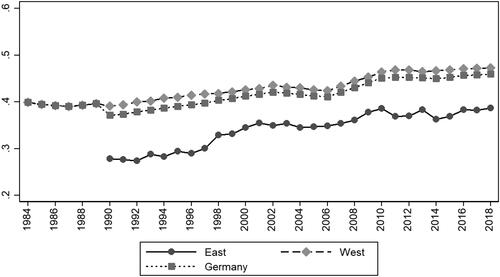

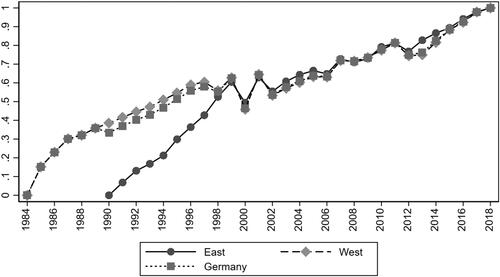

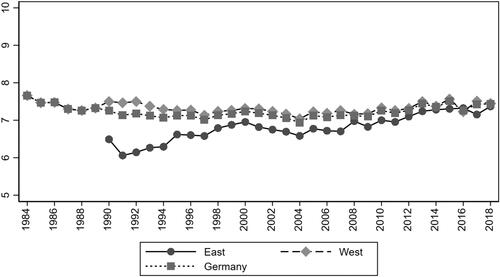

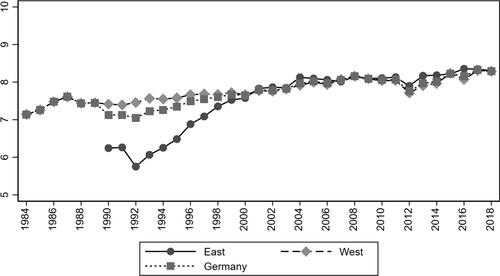

Germany has a well-developed residential rental market with strong tenant protections. Renting seems to be as good as owning such that we assume that our estimated effects of homeownership on SWB are smaller in Germany compared to most other industrialized countries. Traditionally, the mortgage market is conservative with long-term fixed interest rates and a restrictive lending policy (Tsatsaronis & Zhu, Citation2004; Voigtländer, Citation2009). Accordingly, indebted homeowners are not as exposed to the volatility of the financial markets as in countries with mostly variable mortgage rates. Hence, owners with a mortgage should not experience a lot of stress due to macroeconomic shocks such as the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). This should apply even more strongly to outright owner-occupiers. Indeed, the German housing market was not affected much by the GFC (van der Heijden et al., Citation2011; Voigtländer, Citation2014; Wijburg & Aalbers, Citation2017). This stability of the German housing market is also reflected in the homeownership rate which has been inconsiderably fluctuating between 40 and 50 per cent. Similarly, the time series of life and housing satisfactions are relatively constant over time, although the mean satisfaction in East German states started at lower levels and caught up to some degree to the West German level ().

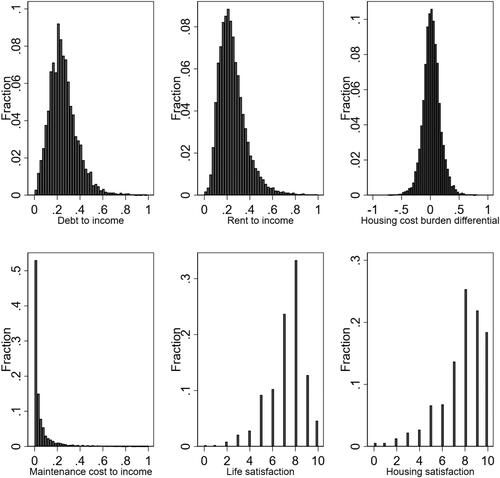

Our variables of main interest life satisfaction and housing satisfaction are obtained using the following questions: “In conclusion, we would like to ask you about your satisfaction with your life in general. How satisfied are you with your life, all things considered?,” given possible answers ranging from 0 (“completely dissatisfied”) to 10 (“completely satisfied”). This measure is commonly used and found to be a good proxy for SWB. Housing satisfaction was surveyed by the question “How satisfied are you with your dwelling?” with the same answer possibilities as above. The distributions of the two variables are depicted in .

We assume that households’ heads and their partners experience the most (dis-)utility of becoming a homeowner or a debtor. The responsibilities associated with homeownership, e.g., maintaining the house or serving the credit, are mostly borne by them. For that reason, we exclude not only children but all other household members who are not the heads of the households and their partners. We end up with a total sample size of 91,491 observations consisting of 7,056 individuals of which we can observe a transition from being a renter to a first-time owner.Footnote1 If a household purchases a home and goes back to renting after some years, we consider it only until this second change in tenure status. If a household breaks up, we still consider the individual that remains in the owned home and we still count the years of owning (if there is no transition back to renting). The individual that leaves the household, creates a new household (if (s)he responded to the survey again). However, we do not consider this individual again as there could be distortions, e.g., a habituation effect towards the purchase (Clark & Diaz-Serrano, Citation2023).

The summary table () shows the mean of the considered variables for both owners (i.e., individuals after the purchase) and renters (i.e., individuals before the purchase). The table clearly states that renters and owners are inherently different. Owners are significantly more satisfied with their homes than renters. Owners are to a lesser extent full-time employed or unemployed, and more often employed part-time, and retired. Following, owners are significantly older and have a higher probability of being married (83 per cent). The housing characteristics differ as well: Homeowners have a higher probability of having access to a garden, a balcony or terrace, and a basement. Owning households occupy on average 127 square meters of residential space while renters only have 86 square meters. In general, the western parts of Germany have a higher ownership rate than the eastern parts.

Empirical Strategy

To test our hypotheses, we rely on two estimation approaches. First, we estimate the status effect of being a homeowner with or without a mortgage. Second, we incorporate indicator variables into the model which indicate the timing of the home purchase and up to 6 years before and after the event. For both models, we use an OLS estimator with both individual and time-fixed effects. Therefore, our static estimation model has the following form:

(1)

(1)

is a categorical variable that indicates whether individual

lives in an owner-occupied dwelling with or without a mortgage, or whether it is rented.

is a matrix containing individual and household characteristics of

in

while

depicts a matrix of dwelling-related characteristics in which

lives in period

and

capture time and individual invariant unobservable characteristics effects, respectively.

is the idiosyncratic error term. The dependent variable

is the regarding satisfaction variable, either life or housing satisfaction.

Additionally, we run the following model:

(2)

(2)

where is the monthly loan repayment divided by the household’s net income. The debt-to-income ratio (DTI) is an indicator of how heavy the financial burden of a household is.

As the treatment is heterogeneous, i.e., the home purchase varies over time, we include variables that indicate periods before and after the event to examine potential effects that vary depending on the time before and after the event. With this approach, we follow e.g., Qari (Citation2014), Stotz (Citation2019), and Clark and Diaz-Serrano (Citation2023) that our event-study analysis is based on the following specification:

(3)

(3)

Our main independent variables are variables that indicate a change from being a tenant to a homeowner. Furthermore, we observe the time each individual remains in this new tenure status and the time until this specific event. We end up with indicator variables that show the specific amount of years the individual has been a tenant observing a later change in tenure. In period the individual stated that the event – becoming a homeowner – happened for the first time, i.e., the purchase of the housing happened within the last year. In the next period,

if the individual is still a homeowner (now for at least one year but less than two years). We code every indicator variable of

like this, six periods before and after the event. Following Clark and Diaz-Serrano (Citation2023), we consider only the first change in tenure status when there are multiple ones to exclude potential habituation effects of individuals who change between being owner and tenant multiple times.

To capture observable confounders, we include the following variables as covariates into our models: age, family and employment status, number of children, experienced years in school, yearly household income, variables that indicate whether a person in need of care lives in the household, the home has a garden, a balcony, or a basement, the size of the home, the space perception, and whether the home is in West or East Germany. For the sake of brevity, we always refer to a property loan for an owner-occupied home when just writing a loan or mortgage.

Results

We structure our results as follows. First, we examine the static effect while comparing outright owners, indebted owners, and renters before turning to the temporal analysis. Then, we investigate the association between a mortgage and the two satisfaction domains, both statically and dynamically. We plot the coefficients of the event analysis and their confidence intervals and provide the regression result tables in the appendix.

Examining the status of being a renter and being an indebted homeowner compared to outright owners, we estimate Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) . The results are displayed in . We find an insignificant negative effect of renting on life satisfaction compared to outright owners. Housing satisfaction, in contrast, seems to be significantly affected by tenure choice. Assuming linearity among the Likert scale this translates to an approximately 8 percentage point gain in housing satisfaction associated with the ownership. Being a homeowner seems to increase housing satisfaction, while life satisfaction seems to be not affected.

Table 2. Tenants vs. (indebted) homeowners.

Turning to the financial side, shows that owners paying off a property loan experience a significant reduction in life satisfaction compared to owners who buy outright. Housing satisfaction seems to be unaffected. These results provide evidence that a real estate loan harms life satisfaction and has no effect on housing satisfaction.

To test dynamic effects, we proceed with estimating the effects of the event of becoming a homeowner with Equationequation (3)(3)

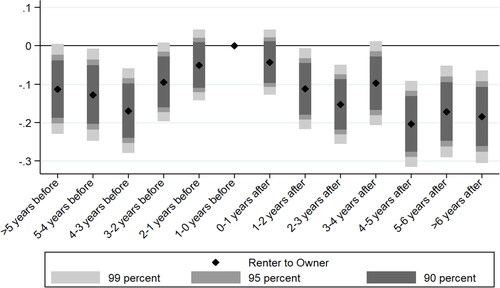

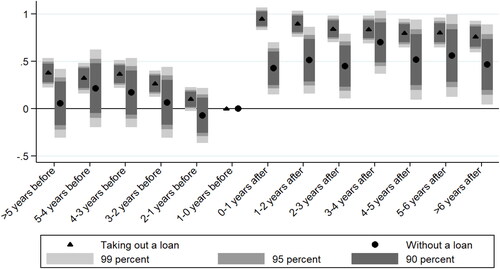

(3) . illustrates how life satisfaction reacts to the transition from being a tenant to an owner up to more than 5 years before and up to six and more years after the change. The diamond markers depict the coefficients while the confidence intervals in the common ranges are depicted by the shaded bars around the coefficient. The y-axis gives the effect size in life satisfaction points on the 11-point Likert scale. We estimate highly significant estimates in most periods. We choose the year of the home purchase as our reference year which is the year in which the individual has indicated for the last time that she lives in a rented dwelling, i.e., the transition from being a renter to becoming a homeowner will happen within a year. The reference year is the year in which life satisfaction is the highest.

Figure 1. The effects of a transition from being a tenant to a homeowner on life satisfaction.

Note: The figure depicts the estimates from a home purchase on life satisfaction with indicators of the year relative to the event. The regression includes both, individual and year-fixed effects and controls for housing and socioeconomic characteristics. The standard errors are clustered at an individual level.

More than five years before the transition, life satisfaction is 1.13 percentage points below the level in the years of the purchase. The lowest level of life satisfaction is reached 4–3 years before the purchase (1.69 percentage points). From that period on, the satisfaction level increases in time until it gets insignificantly different from the year of the event. After the years in which the renter becomes an owner, life satisfaction drops to 1.12 percentage points below 1–2 years after. Afterwards, life satisfaction seems to decrease further and stabilizes around 1.85 percentage points below the reference level. Hence, we estimate lower life satisfaction levels in the long-term after the event of becoming a homeowner than more than five years before the homeownership.

In general, we see anticipation effects starting 3 years before the purchase and adaptation effects up to 5 years afterwards. Hence, the results support the baseline hypothesis. The slightly lower level after 4 or more years compared to more than 5 years before, hints that the transition from being a renter to an owner may even negatively affect life satisfaction in the long-term. Before turning to possible explanations for this finding, we first investigate the baseline hypothesis regarding housing satisfaction.

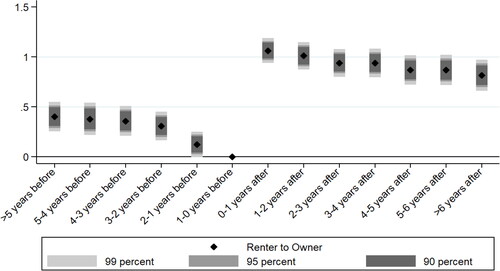

depicts the coefficients and their confidence intervals of Equationequation (3)(3)

(3) with housing satisfaction as the dependent variable. In the reference period, 1–0 years before the transition, the level of housing satisfaction is the lowest. Before becoming a homeowner, we see strong adverse anticipation effects of the event on housing satisfaction. Five or more years before, housing satisfaction lies 4.01 percentage points above the reference year. This level decreases the closer the transition comes. The ownership leads to a heavy increase in height of 10.63 percentage points in housing satisfaction one year later. Afterwards, housing satisfaction decreases again and levels off around 8 percentage points six and more years after becoming a homeowner.

Figure 2. The effects of a transition from being a tenant to a homeowner on housing satisfaction.

Note: The figure depicts the estimates from a home purchase on housing satisfaction with indicators of the year relative to the event. The regression includes both, individual and year-fixed effects and controls for housing and socioeconomic characteristics. The standard errors are clustered at an individual level.

Regarding housing satisfaction, we do not find evidence to fully support the baseline hypothesis although we do find anticipation and adaptation effects which at most converge to a certain baseline level. The difference of approximately 4 percentage points between more than five years before and more than six years after the purchase may be too large to support the baseline hypothesis. Hence, we find clear anticipation and adaptation effects but no clear evidence for a full adaptation back to the baseline level.

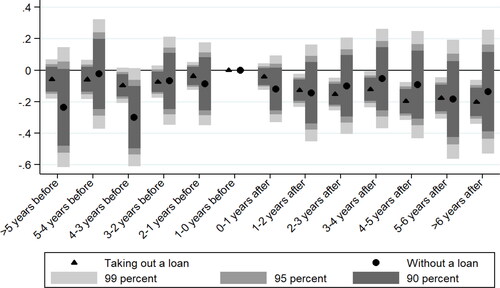

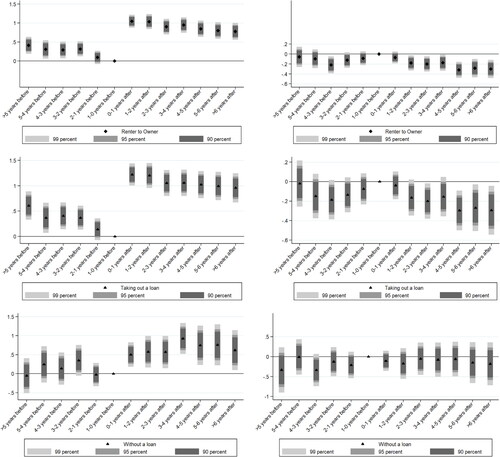

Considering the temporal effects of a mortgage-financed home purchase, we again estimate Equationequation (3)(3)

(3) for both satisfactions as dependent variables and the independent variables of an outright and a debt-financed purchase, respectively. The triangle marks the estimates for the time indicators of taking out a loan while the circle depicts the estimates for the time indicators of buying a home outright ().

Figure 3. The effects of an outright and a debt-financed home purchase on life satisfaction.

Note: The figure depicts the estimates from debt and non-debt-financed home purchases on life satisfaction with indicators of the year relative to the event. The regression includes both, individual and year-fixed effects and controls for housing and socioeconomic characteristics. The standard errors are clustered at an individual level.

Except for the period between three and four years before the tenure change, the estimated effects before the transition are not significantly different from zero for an outright buyer. Moreover, they do not adapt after the event. Similarly, debt-financed buyers do not anticipate the transition. The estimated effects before the transition are with – the exception of the two periods between four and two years before the purchase – insignificantly different from zero. Contrary to outright buyers, debt-financed buyers experience a decrease in life satisfaction after the purchase. Every estimate except for the first after the purchase is significantly below zero. The estimates converge in the long-term towards a level around 2 percentage points below the reference year. Debt-financing buyers seem to be even worse off after the purchase than before. The tenure change of outright buyers does not affect life satisfaction at all. A debt-financed home purchase decreases life satisfaction more than an outright purchase.

depicts the estimates of the effect on housing satisfaction of a debt-financed (triangle markers) and an outright (circle markers) purchase. As in the case of life satisfaction, outright buyers are not affected by the transition beforehand. After the event, they experience a significant increase in housing satisfaction which sustains around 5 percentage points even after six and more years. Hence, we do not estimate anticipation nor adaptation effects and cannot support the baseline hypothesis for outright buyers. Differently, debt-financed buyers’ housing satisfaction anticipates the transition to being a homeowner in advance and negatively adjusts to the lowest point in the year before the purchase. Within the year of the purchase, housing satisfaction increases by 9.47 percentage points which is almost double the increase for outright buyers. In the following periods, the effect decreases to still a 7.59 percentage points increase compared to the year of the purchase. Debt-financing buyers experience anticipation and adaptation effects regarding housing satisfaction. Compared to outright buyers, they experience a larger gain in housing satisfaction even though they seem to converge in the long-run.

Figure 4. The effects of an outright and a debt-financed home purchase on housing satisfaction.

Note: The figure depicts the estimates from debt and non-debt-financed home purchases on housing satisfaction with indicators of the year relative to the event. The regression includes both, individual and year-fixed effects and controls for housing and socioeconomic characteristics. The standard errors are clustered at an individual level.

To examine the effect of a higher financial burden on SWB, we estimate Equationequation (2)(2)

(2) . While life satisfaction decreases by 0.00409 points for every percentage point increase in DTI, housing satisfaction insignificantly gains (). DTI is calculated by dividing the mortgage repayments (including interest payments) by the net household income. The question in the SOEP is the following: “What are your monthly payments including interest on this or these loan(s) or mortgage(s)?” We calculate the net rent burden by subtracting utilities, possible levies and other consumption-based costs from the total rent. We do so to have a comparable measure to the mortgage repayments.

Table 3. Debt-to-income ratio.

Finally, the difference between the DTI and the paid rent prior to ownership acquisition (i. e. the additional financial burden due to the home purchase) could moderate the association between the DTI and SWB. We calculate this delta by subtracting the net rent burden (without utilities and other allocation or consumption costs) from the DTI. We subtract the rent burden of the last year a household rented from the DTI of each year after the purchase.

Our findings, indeed, reveal a negative correlation between life satisfaction and the difference in DTI in every subsequent period post-acquisition and the final rent-to-income ratio prior to acquisition (). The more expensive the mortgage repayment of the new house (compared to the last rented dwelling’s rent) is, the lower is the new homeowner’s life satisfaction.

Robustness Tests

So far, two models have been dominant in the happiness literature, the linear regression model with (two-way) fixed effects and the ordinal logit model without fixed effects. Both have been used to check each other’s plausibility and have led to similar results (Zumbro, Citation2014). Only a few authors have dealt with fixed effects ordered logit models like Ferrer-I-Carbonell and Frijters (Citation2004) or Frijters et al. (Citation2004). While most of the mentioned authors concluded that the results of linear and logistic models are similar for the common 5 to 11 points Likert scale, Schröder and Yitzhaki (Citation2017) argue against using cardinal estimation methods for ordinal data. Baetschmann et al. (Citation2015) show that the widely used fixed effects ordered logit estimators are inconsistent. Baetschmann et al. (Citation2020) suggest an alternative, consistent estimator. To check whether the results are still valid interpreting the Likert scale ordinally, we make use of their so-called BUC estimator. The regression results are depicted in in the appendix and do not show substantial differences to the estimates of our preferred linear two-way fixed effects model.

A recent critique on event studies using two-way fixed effects as we do comes from Sun and Abraham (Citation2021), Callaway and Sant’Anna (Citation2021), Goodman-Bacon (Citation2021), and Baker et al. (Citation2021) who among others show that the standard two-way fixed effects approach leads to biased results in setups where the absorbing treatment (here the transition from a renter to an owner) appears in varying periods. As the treatment (home purchase) varies over time depending on the decision of each individual, this critique might also apply to our estimation strategy. Sun and Abraham (Citation2021) propose an alternative estimator which leads to unbiased lags and leads coefficients. Applying Sun’s (Citation2021) estimation approach does not lead to largely changing results ( in the appendix).

Another potential shortcoming of our study is that we do not control for other events that occur in the same life cycle e.g., marriage or birth of the first child. As these events should not influence housing satisfaction, the analysis of housing satisfaction seems not to be affected by the exclusion of these events. For life satisfaction e.g., Clark et al. (Citation2008) and Clark and Georgellis (Citation2013) show that marriage and the birth of the first child only have a short-term effect on life satisfaction. Controlling for the number of children should take care of a children-effect. Nevertheless, a time-varying number of children during the observational period can confound the relationship. Hence, we omit households that grow as a consequence of an additional child in the household. The estimates of the model based on this restricted sample do not differ substantially from the unrestricted sample and can be found in . From that, we cannot deduct that an additional (newborn) child does not affect life or housing satisfaction, but we can deduct that this life event does not considerably affect anticipation and adaptation effects of ownership on life and housing satisfaction.

As characterized in Data and Empirical Strategy section, Germany has the second smallest share of homeowners among OECD countries while states of former East Germany on average have an even lower one. The former political system might have led to a different attitude towards homeownership which could moderate the association between ownership and SWB. To test a heterogenous perception of homeownership in East and West German states, we run the models with an interaction between the tenure variable and the location dummy and find only insignificant and small effects (). This leads us to the conclusion that homeownership is not perceived differently. Contrarily, we estimate significant differences in the effect of DTI on life satisfaction. Homeowners in former East German states indicate lower life satisfaction with an increasing DTI compared to owners in West German states. We can only speculate about the reasons for this.

Additionally, we look at possible heterogenous effects over time, especially the GFC might have structurally changed attitudes towards homeownership. In Data and Empirical Strategy section, we describe that the German housing market was barely affected by the GFC. Accordingly, we estimate only few small differences between the two periods ().

Considering the nested structure of the data, i.e., the surveyed individuals are clustered in households, we check the robustness of our results first by clustering the standard errors at the household level. Second, we restrict our sample by randomly keeping only one individual per household. Hence, every household consists of only one randomly chosen adult. Running both analyses, we get similar results to our preferred specifications. The coefficients are even larger and more significant with household-level clustered standard errors and only slightly less significant in the sample with only one randomly chosen adult household member ().

Furthermore, we estimate that the effect of maintenance costs on life satisfaction is insignificantly small (tested through three different specifications: maintenance costs, maintenance costs per square meter, and maintenance costs per income) (). Thus, we deduce that it is the obligation of mortgage repayments (relative to the final rent burden prior to ownership), rather than the supplementary burden of maintenance costs, that negatively affects life satisfaction.

Conclusion

Having examined the home purchase with an event-study, we show significant anticipation and adaptation effects before and after the tenure change. Contrarily to life satisfaction, housing satisfaction does not fully adapt back to its past lower level and sustains its higher level in the long-term. The long-term effect on life satisfaction is small and insignificant.

Comparing the effects of outright buyers to debt-financing buyers, we conclude that the type of financing matters. We show that financial burden in the form of a mortgage negatively affects life satisfaction in the long-term which might come from a strong adaptation effect after the purchase. Outright buyers do not experience significant anticipation or adaptation effects. A possible explanation for the small and insignificant anticipation effect of outright buyers could be that the preparation process of the acquisition is a different one. Households that are going to take out a loan, need to save in advance for the down payment and hence anticipate the acquisition years before. Outright buyers, in contrast, do not necessarily have to prepare such that we do not estimate anticipation effects. Regarding housing satisfaction, we provide evidence that the short-term gains are higher for debt-financing than for outright buyers. This could be due to a sudden increase in the perception of living standards. They do not just swap financial capital for housing capital. Instead, they experience a sudden enhancement in (housing) consumption due to the availability of the loan. Due to the strong adaptation effect of housing satisfaction of debt-financing buyers, the long-term effect on housing satisfaction is not significantly different from the effect of an outright buyer. This could hint at an overestimated satisfaction gain that normalizes after some periods (Odermatt & Stutzer, Citation2019, Citation2022).

On the other hand, the larger the DTI, the higher the housing (insignificant) and the lower the life satisfaction (significant). The financial burden enables the purchase in the first place and hence the following short and long-term increase in housing satisfaction. We estimate no significant differences in housing satisfaction between homeowners who purchase with or without a mortgage. Supposing housing satisfaction influences life satisfaction positively (Diener et al., Citation2017), life satisfaction should also increase persistently. Since we do not find a significant positive effect on life satisfaction directly, it fosters the impression that loan payments for a home are a heavy financial burden that dampens life satisfaction to an extent that the positive effect via the gains in housing satisfaction is neutralized. This effect seems to be driven by mortgage repayments and not maintenance costs which could lead to speculate about the reasons: Do homeowners perceive the repayment of debt differently than the investment in their equity due to a different saliency of the payments?

Thus, the financial part of homeownership seems to have a large effect on SWB. Although homeownership is associated with higher (perceived) financial security in the long run (Garten et al., Citation2024), our results show that the psychological implications of the homeownership-induced financial burdens can be high, especially in the first years after the purchase (Plagnol, Citation2011). Hereby, we provide supporting evidence for Tharp et al. (Citation2020) who estimate a lower satisfaction with the financial situation of homeowners with a real estate loan. Life satisfaction, which returns to its original pre-acquisition level within 5 years after acquiring homeownership, seems to be affected by the difficult financial situation of the new homeowners. The positive aspects of homeownership (higher self-esteem or a nicer and more homogeneous neighborhood) may be offset by the negative implications of the unfamiliar financial strains. In a recent study by Park and Kim (Citation2022), the authors provide evidence for a manifestation of the financial burden or housing affordability stress in very different ways: Certain households may be less affected because they cannot go on holiday or go to a restaurant because of the high housing expenses. Others, however, have difficulties covering more existential expenses like the regular costs for food or clothing and run into difficulties in saving liquid funds for times of financial need. Future studies should focus on the different financial burdens of households and their impact on SWB.

Furthermore, additional investigations of these relationships might be beneficial to get a deeper understanding of how homeownership affects other domain satisfactions like financial, neighborhood, or living standard satisfaction. Concerning the adaptation effects of debt-financing buyers that are not visible for outright buyers, analyzing whether disappointments of potentially exaggerated predictions about the gain in happiness are different between the financing types, may be a promising field of research.

From a methodological point of view, it becomes visible that previous studies which find a significant positive relationship between SWB and homeownership, e.g. (Rohe & Basolo, Citation1997; Rossi & Weber, Citation1996; Ruprah, Citation2010; Seiler Zimmermann & Wanzenried, Citation2019; Zhang & Zhang, Citation2019), did not use a within approach by e.g., including individual and time fixed effects. Being interested in the effect of a home purchase, future studies should focus only on those individuals who have experienced a tenure change.

Disclosure statement

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Notes

1 It is important to note that this sample is not representative for the German population but it consists of (future or past) home buyers in the SOEP. This is also why the share of homeowners in this sample is not comparable to the conventional homeownership rate measured by the statistical office. All individuals in our sample become owners at some point of the observational period.

References

- Aaronson, D. (2000). A note on the benefits of homeownership. Journal of Urban Economics, 47(3), 356–369. https://doi.org/10.1006/juec.1999.2144

- Anderson, C., Kraus, M. W., Galinsky, A. D., & Keltner, D. (2012). The local-ladder effect: Social status and subjective well-being. Psychological Science, 23, 764–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611434537

- Baetschmann, G., Ballantyne, A., Staub, K. E., & Winkelmann, R. (2020). Feologit: A new command for fitting fixed-effects ordered logit models. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 20, 253–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X20930984

- Baetschmann, G., Staub, K. E., & Winkelmann, R. (2015). Consistent estimation of the fixed effects ordered logit model. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society,) 178, 685–703. https://doi.org/10.1111/rssa.12090

- Baker, A., Larcker, D. F., & Wang, C. C. Y. (2021). How much should we trust staggered difference-in-differences estimates? European corporate governance institute - finance working paper. 736/2021.

- Boehm, T. P., & Schlottmann, A. M. (1999). Does home ownership by parents have an economic impact on their children? Journal of Housing Economics, 8(3), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1006/jhec.1999.0248

- Bucchianeri, G. (2009). The American dream or the American delusion? The private and external benefits of homeownership for women. The Wharton School of Business Working Paper.

- Callaway, B., & Sant’Anna, P. H. (2021). Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. Journal of Econometrics, 225, 200–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.12.001

- Clapham, D., Foye, C., & Christian, J. (2018). The concept of subjective well-being in housing research. Housing, Theory and Society, 35, 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2017.1348391

- Clark, A. E. (2003). Unemployment as a social norm: Psychological evidence from panel data. Journal of Labour Economics, 21, 323–351. https://doi.org/10.1086/345560

- Clark, A. E., & Georgellis, Y. (2013). Back to baseline in britain: Adaptation in the British household panel survey. Economica, 80, 496–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12007

- Clark, A. E., Diener, E., Georgellis, Y., & Lucas, R. E. (2008). Lags and leads in life satisfaction: A test of the baseline hypothesis. Economic Journal, 118, 222–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02150.x

- Clark, A., & Diaz-Serrano, L. (2023). Do individuals adapt to all types of housing transitions? Review of Economics of the Household, 21, 645–672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09613-x

- Diaz-Serrano, L. (2009). Disentangling the housing satisfaction puzzle: Does homeownership really matter? Journal of Economic Psychology, 30, 745–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2009.06.006

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

- Diener, E., Heintzelman, S. J., Kushlev, K., Tay, L., Wirtz, D., Lutes, L. D., & Oishi, S. (2017). Findings all psychologists should know from the new science on subjective well-being. Canadian Psychology, 58, 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000063

- Diener, E., Sandvik, E., Seidlitz, L., & Diener, M. (1993). The relationship between income and subjective well-being: Relative or absolute? Social Indicators Research, 28, 195–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01079018

- Dietz, R. D., & Haurin, D. R. (2003). The social and private micro-level consequences of homeownership. Journal of Urban Economics, 54, 401–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0094-1190(03)00080-9

- DiPasquale, D., & Glaeser, E. L. (1999). Incentives and social capital: Are homeowners better citizens? Journal of Urban Economics, 45, 354–384. https://doi.org/10.1006/juec.1998.2098

- Elsinga, M., & Hoekstra, J. (2005). Homeownership and housing satisfaction. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 20, 401–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-005-9023-4

- Engelhardt, G. V., Eriksen, M. D., Gale, W. G., & Mills, G. B. (2010). What are the social benefits of homeownership? Experimental evidence for low-income households. Journal of Urban Economics, 67, 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2009.09.010

- Ferrer-I-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114, 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00235.x

- Fong, E., Yuan, Y., & Gan, Y. (2021). Homeownership and happiness in urban China. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 36, 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-020-09728-6

- Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Shields, M. A. (2004). Money does matter! Evidence from increasing real income and life satisfaction in East Germany following reunification. American Economic Review, 94, 730–740. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828041464551

- Garten, C., Myck, M., & Oczkowska, M. (2024). Homeownership and the perception of material security in old age. Applied Economics, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2024.2364109

- Goebel, J., Grabka, M. M., Liebig, S., Kroh, M., Richter, D., Schröder, C., & Schupp, J. (2019). the German socio-economic panel (SOEP). Jahrbücher Für Nationalökonomie Und Statistik, 239, 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbnst-2018-0022

- Goodman-Bacon, A. (2021). Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. Journal of Econometrics, 225, 254–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2021.03.014

- Green, R. K., & White, M. J. (1997). Measuring the benefits of homeowning: Effects on children. Journal of Urban Economics, 41(3), 441–461. https://doi.org/10.1006/juec.1996.2010

- Herbers, D. J., & Mulder, C. H. (2017). Housing and subjective well-being of older adults in Europe. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 32, 533–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-016-9526-1

- Kahneman, D., & Krueger, A. B. (2006). Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20, 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533006776526030

- Kahneman, D., & Thaler, R. H. (2006). Anomalies: Utility maximization and experienced utility. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20, 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533006776526076

- Kemeny, J. (2001). Comparative housing and welfare: Theorising the relationship. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 16, 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011526416064

- Latif, E. (2021). Homeownership and happiness: Evidence from Canada. Economics Bulletin, 21, 1–17.

- Loibl, C., Moulton, S., Haurin, D., & Edmunds, C. (2022). The role of consumer and mortgage debt for financial stress. Aging & Mental Health, 26, 116–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1843000

- Lucas, R. E. (2007). Adaptation and the set-point model of subjective well-being: Does happiness change after major life events? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 75–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00479.x

- Michalos, A. C. (1985). Multiple discrepancies theory (MDT). Social Indicators Research, 16, 347–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00333288

- Michalos, A. C. (2008). Education, happiness and wellbeing. Social Indicators Research, 87, 347–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9144-0

- Mulder, C. H., & Billari, F. C. (2010). Homeownership regimes and low fertility. Housing Studies, 25, 527–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673031003711469

- Odermatt, R., & Stutzer, A. (2019). (Mis-)predicted subjective well-being following life events. Journal of the European Economic Association, 17(1), 245–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvy005

- Odermatt, R., & Stutzer, A. (2022). Does the dream of home ownership rest upon biased beliefs? A test based on predicted and realized life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(8), 3731–3763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00571-w

- Park, G.-R., & Kim, J. (2022). Trajectories of life satisfaction before and after homeownership: The role of housing affordability stress. Journal of Happiness Studies, 24, 397–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00601-7

- Plagnol, A. C. (2011). Financial satisfaction over the life course: The influence of assets and liabilities. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32, 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2010.10.006

- Powdthavee, N. (2005). Unhappiness and crime: Evidence from South Africa. Economica, 72, 531–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-0427.2005.00429.x

- Qari, S. (2014). Marriage, adaptation and happiness: Are there long-lasting gains to marriage? Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 50, 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2014.01.003

- Reid, C. (2013). To buy or not to buy? Understanding tenure preferences and the decision-making processes of lower-income households. Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University Working Papers.

- Rohe, W. M., & Basolo, V. (1997). Long-term effects of homeownership on the self-perceptions and social interaction of low-income persons. Environment and Behavior, 29, 793–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916597296004

- Rohe, W. M., & Stegman, M. A. (1994). The impact of home ownership on the social and political involvement of low-income people. Urban Affairs Quarterly, 30, 152–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/004208169403000108

- Ronald, R. (2008). The ideology of home ownership: Homeowner societies and the role of housing. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rossi, P. H., & Weber, E. (1996). The social benefits of homeownership: Empirical evidence from national surveys. Housing Policy Debate, 7, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.1996.9521212

- Ruprah, I. J. (2010). Does owning your home make you happier? Impact evidence from latin America. IDB Publications Working papers, OVE/WP-02/10.

- Saunders, P. (1990). A nation of home owners. Routledge.

- Schröder, C., & Yitzhaki, S. (2017). Revisiting the evidence for cardinal treatment of ordinal variables. European Economic Review, 92, 337–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2016.12.011

- Seiler Zimmermann, Y., & Wanzenried, G. (2019). Are homeowners happier than tenants? Empirical evidence for Switzerland. In G. Brulé, , & C. Suter, (Eds.) Wealth(s) and Subjective Well-Being. Springer International Publishing. pp. 305–321.

- Smith, S. J., Cigdem, M., Ong, R., & Wood, G. (2017). Wellbeing at the edges of ownership. Environment and Planning A: Economcy and Space, 49, 1080–1098. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16688471

- Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). (2020). Data for years 1984-2018. SOEP-Core v35, https://doi.org/10.5684/soep.core.v35

- Stotz, O. (2019). The perception of homeownership utility: Short-term and long-term effects. Journal of Housing Economics, 44, 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2018.11.003

- Sun, L. (2021). EVENTSTUDYINTERACT: Stata module to implement the interaction weighted estimator for an event study. https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:boc:bocode:s458978.

- Sun, L., & Abraham, S. (2021). Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. Journal of Econometrics, 225, 175–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.09.006

- Tharp, D.T., Seay, M., Stueve, C., Anderson, S., 2020. Financial satisfaction and homeownership. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 41, 255–280.

- Tsatsaronis, K., & Zhu, H. (2004). What drives housing price dynamics: Cross-country evidence. BIS Quarterly Review, March. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1968425.

- van der Heijden, H., Dol, K., & Oxley, M. (2011). Western European housing systems and the impact of the international financial crisis. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 26, 295–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-011-9230-0

- van Praag, B. M., Frijters, P., & Ferrer-I-Carbonell, A. (2003). The anatomy of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 51, 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(02)00140-3

- Veenhoven, R. (2010). Life is getting better: Societal evolution and fit with human nature. Social Indicators Research, 97, 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9556-0

- Veenhoven, R., & Ehrhardt, J. (1995). The cross-national pattern of happiness: Test of predictions implied in three theories of happiness. Social Indicators Research, 34, 33–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01078967

- Voigtländer, M. (2009). Why is the german homeownership rate so low? Housing Studies, 24, 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030902875011

- Voigtländer, M. (2014). The stability of the German housing market. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 29(4), 583–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-013-9366-1

- Wijburg, G., & Aalbers, M. B. (2017). The alternative financialization of the German housing market. Housing Studies, 32(7), 968–989. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1291917

- Zhang, C., & Zhang, F. (2019). Effects of housing wealth on subjective well-being in urban China. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 34, 965–985. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-019-09651-5

- Zumbro, T. (2014). The relationship between homeownership and life satisfaction in Germany. Housing Studies, 29, 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.773583

Appendices

Appendix A

Table A1. The effects of a transition from being a tenant to a homeowner on life and housing satisfaction.

Table A2. The effects of a debt-financed home purchase on life and housing satisfaction.

Table A3. The effects of an outright home purchase on life and housing satisfaction.

Table A4. The effects of a transition from being a tenant to a homeowner on life and housing satisfaction – BUC and Sun’s estimators.

Table A5. The effects of a debt-financed home purchase on life and housing satisfaction - BUC and Sun’s estimators.

Table A6. The effects of an outright home purchase on life and housing satisfaction – BUC and Sun’s estimators.

Table A7. The effects of maintenance costs on life and housing satisfaction.

Table A8. The effects of maintenance costs on life and housing satisfaction.

Appendix B

Figure B1. Renter to owner transitions excluding households that grow as a consequence of a child’s birth.

Note: The figures depict the estimates from debt and non-debt-financed home purchases on housing (left column) and life (right column) satisfaction with indicators of the year relative to the event. We omit households that experience expansion due to a child’s birth in the considered period. The regression includes both, individual and year-fixed effects and controls for housing and socioeconomic characteristics. The standard errors are clustered at an individual level.

Table B1. Different perceptions in East and West German states.

Table B2. Subsample with only one randomly chosen individual per household.

Table B3. Regression results with standard errors clustered at the household level.

Table B4. Testing pre- and post-GFC effects.

Appendix C

Figure C1. Homeownership rate in Germany from 1984 to 2018 (unrestricted sample, representative of the German population).

Note: Share of households who own their home per year. Own calculations based on SOEP (Citation2020).

Figure C2. Homeownership rate of sample with only transitioning households (1984 to 2018).

Note: Share of households who own their home per year. Because our final sample consists only of households that become homeowners at a point during our sample period without considering households that change back to renting, all these households are owners in the final year of the sample. In 2000, the number of respondents almost doubled due to an extension of the sample which could lead to the visible jump in that year. By definition, we can only identify becoming homeowners if we have at least two observations of the same household. Own calculations based on SOEP (Citation2020).

Figure C3. Life satisfaction in our sample from 1984 to 2018.

Note: Average life satisfaction per year of individuals who rent and become homeowners at some point during the observational period. Own calculations based on SOEP (Citation2020).

Figure C4. Housing satisfaction in our sample from 1984 to 2018.

Note: Average housing satisfaction per year of individuals who rent and become homeowners at some point during the observational period. Own calculations based on SOEP (Citation2020).

Figure C5. Distributions of the housing cost variables and life and housing satisfaction in our sample.

Note: The DTI is calculated by dividing the mortgage repayments by the net household income. The rent burden is the ratio between rent (without utilities) and the net household income. The difference between these two measures is the housing cost burden differential. Own calculations based on SOEP (Citation2020).