ABSTRACT

Pets provide companionship and social facilitation among excluded populations, including homeless people. However, having a pet may restrict access to services, including accommodation. The aims of this study were to assess pet provision among homelessness accommodation providers, and to assess reasons for pet provision or exclusion. An online survey consisting of multiple choice questions and free text boxes was distributed to a UK-wide sampling frame of homelessness service providers in July 2016. Of 523 contacts, 117 replied (response rate 22.4%). Of the respondents, 36.8% (43/117) provided services to pets. In contrast, 76.9% (90/117) reported having requests to accommodate pets. Common reasons for choosing to accept pets included perceived benefit to the owner (36/43, 83.7%) or animal (25/43, 58.1%). Most organizations which allowed pets (35/43, 81.4%) had a policy to ensure the animals’ welfare and restrict damage or nuisance. Of the 74 organizations which did not allow pets, health and safety of staff and other residents were the most common concerns. This study shows that demand for pet-friendly accommodation for homeless people far outstrips supply. In view of the important role that pets play for these vulnerable people, homelessness service providers should be encouraged and assisted to accommodate pets where feasible.

Homelessness in the UK is a serious social problem. The most visible group of homeless are the “rough sleepers” who live out of doors, especially those living on the streets of towns and cities (Shelter, Citation2018; UK_Government, Citation2018). It has been reported that around 5000 people sleep rough in the UK every night (Homeless_Link, Citation2018). This likely represents an under-estimate as rough sleepers may try to avoid street counts. This notwithstanding, the estimated trend is that rough sleeping has increased by 165% since 2010 (Homeless_Link, Citation2018). However, true homelessness figures are much higher when the number of people in hostels, squats and temporary accommodation are included. Recent UK statistics estimate that over 320,000 people in the UK, equivalent to 0.5% of the population, is estimated to be homeless. This figure includes 130,000 children (Reynolds, Citation2018; Shelter, Citation2019).

Pet ownership is thought to be common among homeless people. Although the actual prevalence in the UK is not known, studies around the world suggest that between 5% and 25% of homeless people own pets (Cronley et al., Citation2009; Kerman et al., Citation2019; Rhoades et al., Citation2015).

Pet ownership has been shown to have several benefits for homeless people, who are among the most socially isolated within our society (Sanders & Brown, Citation2015). Having a pet has been demonstrated to provide companionship and unconditional acceptance (Labrecque & Walsh, Citation2011; Rew, Citation2000; Rhoades et al., Citation2015). It is perhaps this acceptance, potentially in the absence of many other strong ties with people, which has led some researchers to observe that homeless pet owners share an unusually intense bond with their animal. This can result in many preferring to remain homeless rather than relinquish their pet (Singer et al., Citation1995; Taylor et al., Citation2004). Pets may fulfill other needs too, including personal safety, giving a sense of motivation and responsibility, and physical warmth (Donley & Wright, Citation2012; Labrecque & Walsh, Citation2011; Rew, Citation2000; Rhoades et al., Citation2015). For some individuals, pet ownership may be linked with reducing criminal activity, improving self-care and reducing drug and alcohol misuse (Bender et al., Citation2007; Irvine et al., Citation2012; Thompson et al., Citation2006).

On the other hand, pet ownership has potentially negative impacts. It has been identified as a barrier to accessing services such as food provision, walk-in centers, medical care and crucially, accommodation (Howe & Easterbrook, Citation2018; Kidd & Kidd, Citation1994; Taylor et al., Citation2004). Thus, pet ownership is interwoven in many of the issues which underlie and promote homelessness. For example, where people are forced to choose between giving up a pet and remaining homeless many will refuse to surrender their pets (Cronley et al., Citation2009; Rhoades et al., Citation2015). Thus, pet ownership can perpetuate homelessness by forming an additional obstacle to accessing housing and other sources of support.

Whilst a number of homelessness service providers choose to accommodate pets, the majority do not. The primary aim of this study was to estimate the prevalence of provision for pets among UK services providing accommodation for homeless people. A secondary aim was to explore the reasons why services chose whether or not to accommodate pets.

Materials and methods

A database of homeless accommodation service providers throughout England was assembled using information provided by the website Homeless Link (https://www.homeless.org.uk/). A customized questionnaire was designed using Google Forms. Multiple choice questions provided information about the organization’s activities, pet policies and reasons for pet policies. All had the option to select “other,” and free text boxes were provided to allow additional comment or where the respondent wished to add to the pre-defined choices available. The questionnaire was piloted by a homelessness accommodation provider and by a member of the outreach project development team at Dogs Trust. Suggested amendments were then incorporated. The final survey was launched via email in July 2016 and was open for eight weeks. Two email reminders were sent at 10–14 day intervals, with follow up telephone calls made to encourage non-responders to participate before the survey was closed.

Responses were downloaded into Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corporation) and descriptive statistics compiled. Where an “other” response was selected and free text responses were provided, these were cross-checked and, where appropriate, assigned to existing categories. Postcodes of responding organizations were converted into geodata and mapped using BatchGeo (https://batchgeo.com/). Categorical data were compared in SPSS version 24 (IBM Corporation) using Pearson’s chi-squared test with Yates’s correction. Significance was set at p = 0.05 throughout.

Results

The initial database compiled comprised 1288 listed service providers across the United Kingdom. When duplicates were removed, this resulted in 679 individual service providers being identified, 523 of which had valid contact details. Of these 523, 117 responded (response rate 22.4%).

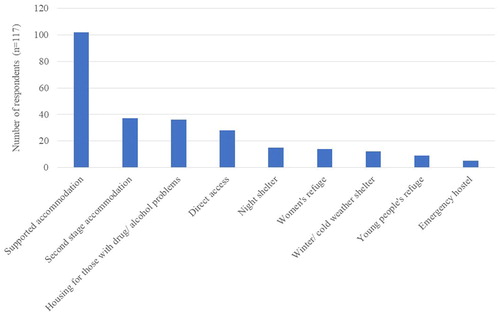

Most respondents provided more than one type of accommodation service, with a median of two and a maximum of seven reported (). Most (99/117, 84.6%) provided services additional to accommodation. These were varied and included support services, education, advice, food and clothing. The geographical spread of respondents can be seen in .

Of the respondents, 36.8% (43/117) provided services to pets, whilst the remaining 61.2% did not. In contrast, 76.9% (90/117) reported having requests to take in pets, whilst only 24 (20.5%) reported no requests, with three respondents unsure. Respondents were asked to estimate the proportion of service seekers presenting with a pet. Most reported under 10% of service seekers presenting with a pet. However, 18/117 organizations (15.3%) 10–25%, and one organization reported 25–50% of service seekers presenting with a pet. Organizations which allowed pets were significantly more likely to be approached for accommodation by homeless pet owners (p = 0.0006).

Of the 43 organizations accepting pets, the most common animals housed were mammals, including dogs (39/43, 90.7%), small prey species such as rabbits or rats (18/43, 41.9%) and cats (16/43, 37.2%). Other taxa housed were reptiles (13/43, 30.2%), fish (13/43, 30.2%), birds (7/43, 16.3%) and amphibia (6/43, 14%).

When asked why they chose to accept pets, most organizations responded that it benefitted the owner (36/43, 83.7%) or the animal (25/43, 58.1%). A number also stated that it benefitted other residents (10/43, 23.3%) or staff (2/43, 4.7%). A small number provided commentary on other aspects, such as the difficulty in helping the owners without helping their pets. Such comments included it can be traumatic enough for a young person finding themselves homeless without having to part with a loved pet and Often Rough Sleepers will not come in to our projects without their pets and we are unable to work with them while on the street. One respondent commented

We find the relationship between someone who has been rough sleeping and their pet (invariably a dog) a strong bond that should be encouraged. Also appropriate management of the pet can be advised on and help the pet become healthier as well as the individual we see.

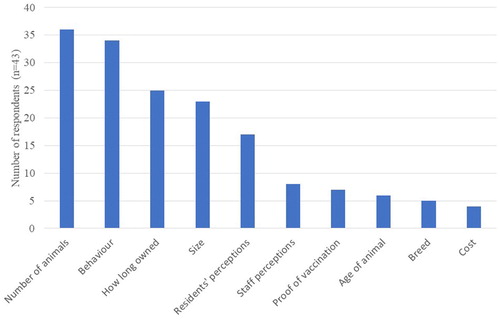

Respondents were asked to select factors which were of importance when considering whether to accommodate owners with their pets. The most common considerations included the number of animals owned (36/43, 83.7%), the behavior of the animals (34/43, 79.1%) and how long they had been in the owner’s possession (25/43, 58.1%) ().

Of the 43 organizations allowing pets, 35 (81.4%) reported specific policies for residents with pets. All of these stated that the pet was the sole responsibility of the owner. A variety of other stipulations were described, mainly concerning the animal’s wellbeing but also designed to limit any damage or nuisance ().

Table 1. Pet policies of the 35 organizations which reported having them.

Seventy-four organizations did not allow pets. A variety of reasons were given for this choice of policy, with health and safety of staff and other residents being the most common (). Other reasons included logistical constraints, such as running out of volunteers’ homes or restrictions set by landlords, the lack of pet-friendly “move-on” accommodation, concerns or experience of maltreatment, neglect or abandonment, or fear that if they set a precedent they would be “over-run.”

Table 2. Reasons for not allowing pets at 74 organizations.

Discussion

The prevalence of pet ownership among homeless people in the UK is unknown, but has been reported to vary widely around the world (Kerman et al., Citation2019). It is clear from the results of the current study that the demand to accommodate pets with their owners in homelessness provision far outstrips supply. Although 76.9% of the 117 participating organizations experienced demand for accommodation provison to include pets, only 38.6% provided such accommodation. This broadly agrees with existing data showing scant pet provision for homeless accommodation seekers in the UK (Howe & Easterbrook, Citation2018). The proportion of pet owners amongst homeless people seeking accommodation in those services was typically under 10%, but in some cases much higher.

In this study, the pet-friendly service providers were significantly more likely to receive requests to accommodate pets, suggesting an awareness of pet services among homeless people. This awareness may be facilitated by pet orientated outreach services such as the Hope Project (Dogs Trust) that signpost users to pet-friendly accommodation providers. It is possible that other, non-pet orientated service and outreach providers do not know where to direct owners. There is a lack of knowledge on how information is currently disseminated across both clients and service providers. Such knowledge could both enhance information transfer and, potentially, provide contacts for service providers who may wish to explore the potential for accommodating pet owners.

Respondents from accommodation providers serving owners commonly referred to perceived benefits to both the owners and the pets. Additionally, a number commented on potential benefits to other residents and staff. This reflects previous research showing that pets can act as social facilitators by encouraging conversation (Wells, Citation2004) including between homed and homeless persons. As Irvine (Citation2012) stated “Strangers will initiate a conversation with a person accompanied by a dog where they would not do so with a person alone.” Likewise, Labrecque and Walsh (Citation2011) interviewed homeless women living in Canadian shelters, not all pet owners. They found that 86% felt that shelters should allow companion animals (Labrecque & Walsh, Citation2011). This reinforces the suggestion that even if not pet owners themselves, people accessing homelessness services may appreciate the benefits of accommodating pets.

Benefits of owning pets in general, and dogs especially, to both physical and mental health have been widely documented, particularly amongst the lonely and socially excluded (Pikhartova et al., Citation2014 Siegel, Citation1990; Zasloff & Kidd, Citation1994). Given that homeless people are identified as some of the most socially excluded (Sanders & Brown, Citation2015) it is reasonable to hypothesize that keeping pets and owners together will offer benefits. Indeed, reduction of isolation and provision of companionship has been repeatedly identified as key self-reported benefits of pet ownership by homeless people (Donley & Wright, Citation2012; Howe & Easterbrook, Citation2018; Kidd & Kidd, Citation1994; Rew, Citation2000) (Donley & Wright, Citation2012; Howe & Easterbrook, Citation2018; Kidd & Kidd, Citation1994; Rew, Citation2000). One homeless focus group participant summed up the importance these animals can have, with the simple comment “I mean my dog is my home” (Thompson et al., Citation2006).

Most of the pet-positive service providers had a pet policy in place. All of the policies stated that the pet was the responsibility of the owner. Other provisions included safeguards for the welfare of the pet and measures to limit nuisance or damage to the accommodation. Both private and public accommodation providers need to have clear and appropriate pet policies if misunderstandings and mishaps are to be avoided (McBride, Citation2005).

The organizations which did not accept pets reported various reasons as to why they chose this approach. Health and safety and hygiene concerns were the most prominent, but most organizations reported several reasons. A small number cited previous problems with poor welfare of pets. Whilst limited data available suggests that overall homeless people’s pets are at least as healthy as the general population (Scanlon et al in review) (Williams & Hogg, Citation2015), clearly there will still be exceptional cases. It is also not clear what was meant by poor welfare in the comments from these respondents. For example, it may have related to concerns for distress the animals may display. Notably, separation-related issues can develop in dogs belonging to homeless people because these dogs may rarely or never have experienced being left alone whilst their owner was not in accommodation. However, these and other stress-related issues can be helped (see for example (Appleby & Pluijmakers, Citation2016)). Service providers should therefore be directed to appropriate veterinary and behavior modification that can help these pet owners and their pets, which may include charitable provision (McBride & Montgomery, Citation2018).

This study has highlighted the difficulties homeless pet owners face whilst trying to access accommodation. Both previous (Labreque & Walsh, Citation2011; Lem et al., Citation2016; Sanders & Brown, Citation2015; Singer et al., Citation1995; Thompson et al., Citation2006) and upcoming (Scanlon et al, in review) research emphasizes the importance of preserving the bond between homeless people and their pets as a way of supporting the health and wellbeing of these vulnerable people. Such positive benefits may have consequent benefits to society and society economics in terms of reduced costs from poor health and anti-social behavior (Scanlon et al., in review). Improving access to accommodation and appropriate behavioral support for the dog will also assist the transition of the individual owner into the workplace and thus into an independently supported lifestyle.

This suggests that policymakers should be encouraged to recognize pet ownership among homeless people as a one health issue. Further research into the logistics of how pet ownership among homeless people can be incorporated and utilized as an efficacious component of their support system and transition out of homelessness is to be welcomed.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. Whilst within the expected range for a survey of this kind, clearly the response rate limits the extent to which results may be generalized. Since the survey header described the topic as being around accommodating of pets with owners, it is possible that this could have generated response bias, with respondents with strong views or pertinent experiences around this issue, either positive or negative, being more likely to respond. Finally, although the pre-defined categories were developed and piloted with the assistance of homelessness service providers and a representative from a long-established outreach initiative, it is possible that they may have not fully captured the remit and services of all respondents. Follow-up interviews and focus groups of accommodation provider organizational decision makers, managers and staff were not performed due to the limited resources available for this project, but would be a desirable extension to this research area.

Conclusion

Among the homelessness accommodation providers responding to this survey, demand for accommodation for pets along with their owners far outstripped supply. Those respondents allowing pets largely managed this by a series of pro-active policies to ensure the pets’ welfare and minimize damage and nuisance. Benefits to the pet owner and, in some cases, other residents and staff were perceived as important reasons to allow pets, in addition to concerns for the welfare of the animal itself. Those services prohibiting pets had a variety of concerns, often centered around logistical issues such as health and safety and hygiene. The importance of keeping homeless people together with their pets is both emphasized in previous literature and reinforced in some of the observations by respondents in the present study. Provision of logistical support to these services may facilitate increased provision for homeless people and their pets to be accommodated together, to the benefit of both owner and pet and potentially to the wider society.

Ethics

This project was reviewed and approved by a panel at the University of Nottingham School of Veterinary Medicine and Science.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the practical assistance offered by Dogs Trust, in addition to grant support, in enabling this project

Disclosure statement

The authors confirm no conflict of interest arising from this work.

Data availability statement and deposition

Data are available at Mendeley Data, doi:10.17632/hh85zcykcn.1.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Louise Scanlon

Louise Scanlon graduated with a degree in Human Science from University College London. She is due to graduate from her veterinary degree in 2020. She completed this research as part of a summer studentship, undergraduate project and Masters in Research included and intercalated into her degree. She is interested in the human-animal bond and how this impacts the welfare of both pets and owners.

Anne McBride

Anne McBride is a Senior Lecturer and Senior Tutor within Psychology at the University of Southampton. Dr Anne McBride holds a B.Sc. (Hons) degree in Psychology awarded by University College London in 1978. She was awarded her Doctorate in animal behaviour (Aspects of Social and Parental Behaviour in the European Rabbit) from the same institution in 1986. In 1992 she obtained a Certificate in Conservation and Ecology from Birkbeck College, London. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. Dr McBride has been a practising animal behaviour therapist since 1987 and was the senior behaviour counsellor at the Animal Behaviour Clinic at the University of Southampton which ran from 1998-2009. She is an Animal Behaviour and Training Council (ABTC) registered Clinical Animal Behaviourist. Her area of interest is human-animal interactions and animal behaviour. Current research topics include human attitudes, perceptions and interactions with animals, the development of problem behaviour, issues relating to housing and pet ownership. She is Chair of the Programme Recognition Committee of the Animal Behaviour and Training Council (ABTC), a member of the European Working Group on Standards for Assistance Dog Training and Welfare; Patron of the Rabbit Welfare Association.

Jenny Stavisky

Jenny Stavisky is Clinical Assistant Professor in Shelter Medicine at the University of Nottingham School of Veterinary Medicine and Science. She was awarded a PGCHE from the University of Nottingham in 2017, a PhD in epidemiology and virology from the University of Liverpool in 2010, and her veterinary degree from the University of Edinburgh in 2002. She is a founding member of the Association of Charity Vets and co-editor of the BSAVA Manual of Shelter Medicine. She founded Vets in the Community which has been providing free veterinary care to homeless and vulnerably housed pet owners in the Nottingham area since 2012. Her research interests include welfare and infectious disease, particularly in shelter and charity contexts, free roaming dog control, rabies prevention and homelessness and pet ownership.

References

- Appleby, D., & Pluijmakers, J. (2016). The relationship between emotions and canine behaviour problems. In D. Appleby (Ed.), The APBC book of companion animal behaviour (3rd ed, pp. 122–143). UK: Souvenir Press.

- Bender, K., Thompson, S. J., Mcmanus, H., Lantry, J., & Flynn, P. M. (2007). Capacity for survival: Exploring strengths of homeless street youth. Child & Youth Care Forum, 36(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-006-9029-4

- Cronley, C., Strand, E. B., Patterson, D. A., & Gwaltney, S. (2009). Homeless people who are animal caretakers: A comparative study. Psychological Reports, 105(2), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.105.2.481-499

- Donley, A. M., & Wright, J. D. (2012). Safer outside: A qualitative exploration of homeless people’s resistance to homeless shelters. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice, 12(4), 288–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228932.2012.695645

- Homeless_Link. (2018). Rough sleeping – explore the data [Online]. Retrieved February 26, 2019, from http://www.homeless.org.uk/facts/homelessness-in-numbers/rough-sleeping/rough-sleeping-explore-data

- Howe, L., & Easterbrook, M. J. (2018). The perceived costs and benefits of pet ownership for homeless people in the UK: Practical costs, psychological benefits and vulnerability. Journal of Poverty, 22(6), 486–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2018.1460741

- Irvine, L. (2012). Animals as lifechangers and lifesavers: Pets in the redemption narratives of homeless people. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 42(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241612456550

- Irvine, L., Kahl, K. N., & Smith, J. M. (2012). Confrontations and donations: Encounters between homeless pet owners and the public. The Sociological Quarterly, 53(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01224.x

- Kerman, N., Gran-Ruaz, S., & Lem, M. (2019). Pet ownership and homelessness: A scoping review. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 28(2), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2019.1650325

- Kidd, A. H., & Kidd, R. M. (1994). Benefits and liabilities of pets for the homeless. Psychological Reports, 74(3), 715–722. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1994.74.3.715

- Labrecque, J., & Walsh, C. A. (2011). Homeless women’s voices on Incorporating companion animals into Shelter services. Anthrozoös, 24(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303711X12923300467447

- Lem, M., Coe, J. B., Haley, D. B., Stone, E., & O’grady, W. (2016). The protective association between pet ownership and depression among street-involved youth: A cross-sectional study. Anthrozoös, 29(1), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2015.1082772

- McBride, E. A. (2005). Housing: Issues, policies, solutions. In J. Dono & E. Ormerod (Eds.), Older people and pets: A comprehensive guide (pp. 100–123). Society for Companion Animal Studies.

- McBride, E. A., & Montgomery, D. J. (2018). Animal welfare: A contemporary understanding demands a contemporary approach to behavior and training. People and Animals: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 1(Article 4), 1–16. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/paij/vol1/iss1/4

- Pikhartova, J., Bowling, A., & Victor, C. (2014). Does owning a pet protect older people against loneliness? BMC Geriatrics, 14(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-14-106

- Rew, L. (2000). Friends and pets as companions: Strategies for coping with loneliness among homeless youth. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 13(3), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2000.tb00089.x

- Reynolds, L. (2018). Homelessness in Great Britain – the numbers behind the story. Shelter.

- Rhoades, H., Winetrobe, H., & Rice, E. (2015). Pet ownership among homeless youth: Associations with mental health, service utilization and housing status. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 46(2), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0463-5

- Sanders, B., & Brown, B. (2015). ‘I was all on my own’: Experiences of lonliness and isolation amongst homeless people. Crisis.

- Shelter. (2018). Homelessness in Great Britain – the numbers behind the story.

- Shelter. (2019). Shelter warns 131,000 children will be homeless this Christmas, the highest in over a decade [Online]. Retrieved December 11, 2019, from https://england.shelter.org.uk/media/press_releases/articles/shelter_warns_131,000_children_will_be_homeless_this_christmas,_the_highest_in_over_a_decade

- Siegel, J. M. (1990). Stressful life events and use of physician services among the elderly: The moderating role of pet ownership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1081–1086. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1081

- Singer, R. S., Hart, L. A., & Zasloff, R. L. (1995). Dilemmas associated with rehousing homeless people who have companion animals. Psychological Reports, 77(3), 851–857. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3.851

- Taylor, H., Williams, P., & Gray, D. (2004). Homelessness and dog ownership: An investigation into animal empathy, attachment, crime, drug use, health and public opinion. Anthrozoös, 17(4), 353–368. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279304785643230

- Thompson, S. J., Mcmanus, H., Lantry, J., Windsor, L., & Flynn, P. (2006). Insights from the street: Perceptions of services and providers by homeless young adults. Evaluation and Program Planning, 29(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2005.09.001

- UK_Government. (2018). Rough sleeping strategy. Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government.

- Wells, D. L. (2004). The facilitation of social interactions by domestic dogs. Anthrozoös, 17(4), 340–352. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279304785643203

- Williams, D., & Hogg, S. (2015). The health and welfare of dogs belonging to homeless people. Pet Behaviour Science, 1.

- Zasloff, R. L., & Kidd, A. H. (1994). Loneliness and pet ownership among single women. Psychological Reports, 75(2), 747–752. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1994.75.2.747