ABSTRACT

This observational longitudinal cohort study examines housing status, the prevalence of a comprehensive set of individual modifiable risk factors for homelessness, and changes in the prevalence of housing status and these risk factors among initially homeless people from Amsterdam over a period of 5.5 years. The four constitutional conditions of the Social Quality Approach (namely living conditions, interpersonal embeddedness, societal embeddedness and self-regulation), were used to cluster the risk factors included in this study. Data were collected with a quantitative questionnaire that was orally administered at two time points; at baseline (at shelter entry), and at follow-up (5.5 years after shelter entry). At baseline (n = 172), as expected, the participants were seriously disadvantaged regarding all four constitutional conditions of social quality. At the 5.5 year follow-up (n = 72), 69% of the participants were stably housed, and, although for all four constitutional conditions of social quality significant improvements were found, the prevalence of the majority of risk factors had not decreased after 5.5 years. Findings indicate that, even 5.5 years after shelter entry, Dutch initially homeless people still experienced high levels of social exclusion, which leaves them particularly vulnerable for recurrent homelessness. Implications for policy and practice are discussed.

Introduction

Homelessness is a serious and widespread public health problem, affecting the quality of daily life of increasing numbers of people in Europe (Fondation Abbé Pierre – FEANTSA, Citation2018; Fondation Abbé Pierre – FEANTSA, Citation2019). Homelessness can be narrowly defined as not having a roof over one’s head (Edgar et al., Citation2007), but this definition fails to take into account that homelessness is not a permanent state (De Vet, Citation2019). Many homeless persons transition repeatedly between living on the streets, residing in shelters or institutions such as a hospital or jail, being housed, and atypical living situations such as staying in a hotel, in a squatted building, or with family or friends (Orwin et al., Citation2005; Van der Laan, Citation2020).

Homelessness is often perceived as the result of a complex interaction between structural or societal factors and individual factors. Well-known structural risk factors for homelessness are, for example, the absence of low-cost housing and a lack of or insufficient income support (Fazel et al., Citation2014). Well-known individual risk factors are, for instance, a poor physical health (Nilsson et al., Citation2019), mental health issues (Grattan et al., Citation2022; Nilsson et al., Citation2019; Schreiter et al., Citation2021), and the absence of a social support system (Bramley & Fitzpatrick, Citation2018; Grattan et al., Citation2022). Besides governments investing in improving societies’ structural factors, insight into modifiable risk factors for homelessness and the extent to which their prevalence changes over time is also needed. Homeless services can use this knowledge to prevent people from recurrent homelessness. The Social Quality Approach (SQA; Van der Maesen & Walker, Citation2012; Wolf & Jonker, Citation2020) offers a deeper understanding of factors and processes associated with social exclusion; because, in essence, social quality is concerned with risk factors for societal participation. According to the SQA there are four conditions that constitute the quality of daily life: (1) living conditions; (2) interpersonal embeddedness; (3) societal embeddedness; and (4) self-regulation. Living conditions refer to the extent to which people acquire material and immaterial resources, thus enabling them to live a good life, such as being employed, having sufficient financial resources and having a safe place to live. Interpersonal embeddedness is the degree to which people experience meaningful, reciprocal positive relationships and develop a sense of connectedness with others (for example, with family and friends) based on shared values and identities. Societal embeddedness means the extent to which people are integrated (or able to participate) in their community or society and are able to access or make use of their basic rights (for instance the degree to which they can access professional care for physical or mental health problems). Finally, self-regulation is the degree to which people are in control of themselves and their lives and can alter their own internal states, processes and responses (thoughts, feelings and actions) in anticipation of future goals. Self-regulation is influenced, for example, by the degree to which people experience psychological distress or the extent to which they depend on drugs or alcohol to regulate their feelings and emotions. A more extensive elaboration of the SQA is described elsewhere (Wolf & Jonker, Citation2020).

Studies on individual modifiable risk factors for homelessness reveal risk factors in all four constitutional conditions for “a good life”. Regarding living conditions, a low educational level (Benjaminsen, Citation2016; Nilsson et al., Citation2019), unemployment (Czaderny, Citation2020; Doran et al., Citation2019; Nilsson et al., Citation2019), financial hardship such as having a low income (Georgiades, Citation2015; Tsai & Rosenheck, Citation2015), and living in poverty (Bramley & Fitzpatrick, Citation2018; Doran et al., Citation2019) were found to be risk factors for homelessness. Risk factors for homelessness relating to interpersonal embeddedness were found to be a frail social support system, such as relationship and family conflicts (Grattan et al., Citation2022; Mabhala et al., Citation2017; Piat et al., Citation2015), relationship breakups (Czaderny, Citation2020; Georgiades, Citation2015), social isolation (Tsai & Rosenheck, Citation2015), lacking social support networks (Bramley & Fitzpatrick, Citation2018), and even going back as far as a person’s youth, known as adverse childhood experiences (Czaderny, Citation2020; Nilsson et al., Citation2019; Schreiter et al., Citation2021). Where societal embeddedness is concerned; a previous imprisonment (Benjaminsen, Citation2016; Czaderny, Citation2020; Nilsson et al., Citation2019), being a veteran (Nilsson et al., Citation2019; Tsai & Rosenheck, Citation2015), and major life transitions such as release from rehab, an eviction, and a release from jail (Barile et al., Citation2018) were identified as risk factors for becoming homeless. Risk factors for homelessness relating to self-regulation were found to be physical health issues (Barile et al., Citation2018; Doran et al., Citation2019), mental health problems (Barile et al., Citation2018; Grattan et al., Citation2022; Nilsson et al., Citation2019; Schreiter et al., Citation2021) and substance abuse (Czaderny, Citation2020; Doran et al., Citation2019; Grattan et al., Citation2022; Nilsson et al., Citation2019). Studies specifically investigating risk factors for recurrent homelessness after the transition from homelessness to housing are scarce, but mostly reveal the same individual modifiable risk factors as for first-time homelessness (De Vet, Citation2019). Therefore, insight into the changes in the prevalence of these risk factors over time among homeless people seems essential for preventing recurrent homelessness.

Present study

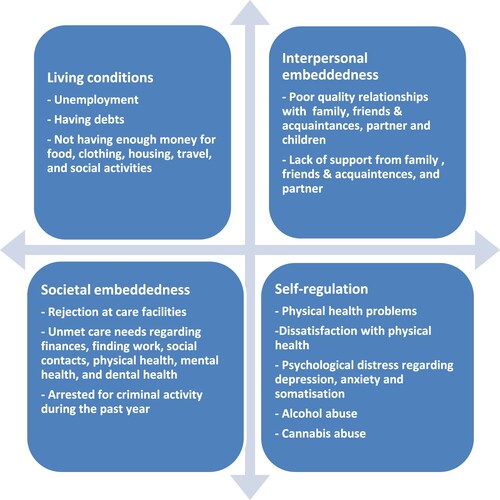

Although research over the last decades has accumulated considerable knowledge on risk factors for homelessness, we still know little about changes in the prevalence of these risk factors over time. Therefore, this present study longitudinally assesses the prevalence of a comprehensive set of individual modifiable risk factors for (recurrent) homelessness in the lives of initially homeless people over a 5.5 year period. Given that social service providers can only effectively address issues that are amenable to change over time, our study specifically focuses on individual modifiable risk factors. This exploratory study addresses the following research questions: (1) what is the prevalence of individual modifiable risk factors for homelessness among homeless people at admission to the social relief system in Amsterdam and 5.5 years later, also considering their housing status?; and (2) does the prevalence of these risk factors for homelessness change 5.5 years after shelter entry? The risk factors assessed in this study, grouped in the four conditions of the SQA, are shown in .

Figure 1. Study variables, grouped in the four constitutional conditions of the Social Quality Approach (Wolf & Jonker, Citation2020).

Findings of this study may raise awareness of the extent to which homeless people are at high risk of recurrent homelessness, and may provide important clues to service providers and policy makers as to what is needed to structurally enhance the four constitutional conditions for “a good life” in order to prevent recurrent homelessness.

Methods

Study design

This study is part of a longitudinal multi-site cohort study following 513 initially homeless people for a period of 2.5 years, starting from the moment they reported at a central access point for social relief in 2011 in one of the four major cities in the Netherlands (G4: Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam and Utrecht). Participants from one of these cities, Amsterdam, were followed up for a period of 5.5 years (Van den Dries et al., Citation2018). Data for this sample were collected by means of a quantitative questionnaire that was administered face-to-face at two time points: at baseline (T0) between January 2011 and December 2011, and at follow-up (T1) between July 2016 and June 2017. This study was exempt from formal review by the accredited Medical Review Ethics Committee – Arnhem-Nijmegen (file number 2010-321).

Participants

In the Netherlands it is obligatory for every homeless person to report at a central access point and to be accepted for an individual program plan, in order to get access to social relief facilities, such as a night shelters or residential shelters. The delivery of care and the supply of living accommodation after accepting an individual program plan is provided by local care agencies and is financed by the municipalities. The municipalities act as policy coordinators and case managers monitor the execution of the individual program plans. The individual program plans were generally aimed at achieving stable housing, steady income, meaningful daily activities, and contact with service providers. To be accepted for an individual program plan, participants had to meet the following criteria: being at least 18 years of age, having legal residence in the Netherlands, having resided in the region of application for at least 2 of the preceding 3 years, having abandoned the home situation, and being unable to hold one’s own in society. Participation in the current study was completely independent of the participants’ treatment plans, program engagement, or the care they received. There was no interaction between the research team and the care providers regarding the treatment or program plans for the participants, and participation in the study did not influence or alter the individual programs and treatments that participants received.

At baseline (T0) 172 participants from Amsterdam completed the face-to-face administered questionnaire. At follow-up (T1) all former 172 participants were contacted, of whom 72 participants (42%) took part in the interview and were included in the analyses. Reasons for attrition were: inability to contact the participant (n = 56), unwillingness to participate (n = 15), no show at the scheduled interview (n = 13), inability to participate due to private circumstances such as health problems (n = 5), death (n = 4) or emigration (n = 3). Two participants had moved to another G4 city within the first two years of the study and were therefore followed within another cohort. Additionally, two participants who completed the interview were excluded from the study because the researcher questioned the reliability of their answers.

To investigate selective loss to follow-up, we compared respondents on the final interview (n = 72) with non-respondents of the Amsterdam cohort (n = 100) on demographic variables as reported at the first measurement. See Table A1 in the appendix for a comprehensive comparison of the two groups. On most characteristics, no differences were found between participants who only completed the questionnaire at baseline compared to participants who completed the questionnaire at baseline and follow-up after 5,5 years. However, non-respondents were less likely to be employed or to have children.

Procedure

At the start of the study in January 2011 (T0), potential participants were approached, either at a central access point for social relief in Amsterdam by an employee of the access point, or at temporary accommodation where they stayed shortly after entering the social relief system, by the researchers or interviewers. Potential participants were informed about the study by means of leaflets, posters and face-to-face information provision. When a potential participant expressed interest in taking part in the study, the researchers contacted that person to explain the study aims, the interview procedure and the informed consent. When the participant then agreed to participate based on the terms explained to them, an interview appointment was scheduled. At follow-up (T1), participants were contacted by letter, telephone, e-mail, their social contacts, their (former) caregiver/institution and/or private messages via social media. At both measurements (mean duration of 1.5 h) participants gave written informed consent and received €15 for their participation.

Problems that may occur when using questionnaires designed for the general population among people with an intellectual disability were anticipated, e.g. acquiescence, not understanding the question, getting tired during the interview (Finlay & Lyons, Citation2001). Participants were for example told that they could take a break during the interview and that they were allowed to have missing answers.

Measures

Demographics

The following demographic characteristics were assessed at the follow-up measurement: age, gender, having a partner, having one or more children, and educational level. Education was categorized as “lowest” when the participant completed primary education at the most, as “low” when the participant completed prevocational education, lower technical education, assistant training or basic labor-oriented education, as “intermediate” when the participant completed secondary vocational education, senior general secondary education or pre-university education, and categorized as “high” when the participant completed higher professional education or university education.

Housing status

Stable housing was assessed at baseline and at follow-up, and the median duration of lifetime homelessness was assessed at baseline. Stable housing was defined as being at least 90 consecutive days independently housed or living in supportive housing at the 5.5 year follow-up interview. Supportive housing is a combination of independent housing and support services, in which the house is generally owned by a care organization.

Risk factors for (recurrent) homelessness

The risk factors for homelessness, grouped in the four conditions of the SQA, were collected at baseline and at follow-up after 5.5 years.

Living conditions

This condition was assessed with seven factors: unemployment, having debts, and not having enough money for: food, clothing, housing, travel, and social activities. All factors were assessed with questions from the Dutch abbreviated version of the Lehman Quality of Life Interview (QoLI; Wolf et al., Citation2002). The answer options were yes or no.

Unemployment was assessed with the question: “Are you working now or have you worked during the past year?”. Having debts, not including mortgages, was assessed with the question: “Do you currently have debts?”. Not having enough money was measured with five items: “During the past month, did you generally have enough money to cover (1) food, (2) clothing, (3) housing, (4) travel around the city for things like shopping, medical appointments, or visiting friends and relatives and (5) social activities like movies or eating in restaurants?”

Interpersonal embeddedness

This condition encompasses seven factors: quality of relationships with (a) family members, (b) friends and acquaintances, (c) partner, and (d) child(ren), and lack of support from (a) family members, (b) friends and acquaintances, and (c) partner.

The quality of relationships was assessed with questions from the QoLI (Wolf et al., Citation2002). The answer options ranged from terrible (1) to delighted (7), where a score below 4 was considered as poor quality relationships. The quality of relationships with family members was measured with two questions: “How do you feel about (1) the way you and your family act toward each other?, and (2) the way things are in general between you and your family?". A score was constructed by averaging responses. Cronbach's α of this sub-scale was 0.92 at baseline and 0.97 at follow-up. The quality of relationships with friends and acquaintances was assessed with one question: “How do you feel about the people you see socially?”. The quality of relationships with a partner and children were measured with one question each, consecutively: “How do you feel about the way things are in general between you and your partner?” and “How do you feel about the way things are in general between you and your child(ren)?”. Lack of support from family members was assessed with five items derived from scales developed for the Medical Outcome Study (MOS) Social Support (Sherbourne & Stewart, Citation1991). Participants were asked to indicate how often their family members are there for them to (1) have fun with, (2) offer you meals or a place to stay, (3) listen to you talking about yourself or your problems (4) offer you moral support by accompanying you with appointments and (5) show you that they care about you or love you? A score was constructed by averaging responses, which ranged from none of the time (1) to all of the time (5). A score of 3 or lower was considered as representing a lack of support. Cronbach's α of this sub-scale was 0.90 at baseline and 0.94 at follow-up. Lack of support from friends and acquaintances and lack of support from a partner were measured with the same items and cutoff point. Cronbach's α for these sub-scales were subsequently 0.88 at baseline and 0.94 at follow-up for friends and acquaintances and 0.76 at baseline and 0.79 at follow-up for partner.

Societal embeddedness

This condition includes eight factors: rejection at care facilities, being arrested or picked up for criminal activity during the past year, and unmet care needs regarding: finances, finding work, social contacts, physical health, mental health and dental health. Rejection at care facilities was assessed at the follow-up interview with the following question: “Have you ever been rejected at a care facility?”. Being arrested or picked-up for criminal activity during the past year was measured with one item: “Have you been arrested or picked-up for any crimes in the past year?”. Unmet needs were assessed per domain (e.g. finances, finding work, social contacts, physical health, mental health, and dental health) with the questions: “Do you want help with … ?” and “Do you receive help with … ?”. Participants who indicated they wanted but did not receive help were considered to have an unmet need.

Self-regulation

This condition was assessed with seven factors: physical health problems, dissatisfaction with physical health, psychological distress regarding: depression, anxiety and somatization, excessive alcohol use and excessive cannabis use. To measure physical health problems, the number of self-reported physical complaints over the last 30 days was assessed on 20 categories of complaints. This included 14 categories based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD; World Health Organisation, Citation1994), five categories of common complaints (visual problems, auditory problems, dental problems, foot problems, fractures) (Levy & O’Connell, Citation2004) and a final category “health-related complaints not previously mentioned”. Because the mean number of physical health problems within the total cohort of the larger observational longitudinal cohort study was around 3 (Van Straaten et al., Citation2017), a score of 4 and above was considered high physical complaints and a score below 4 was considered low physical complaints. Dissatisfaction with physical health was measured with one item from the QoLI: “How do you feel about your physical condition?”. Responses ranged from terrible (1) to delighted (7). A score below 4 was considered as dissatisfaction with physical health. Psychological distress was measured with three symptom scales (i.e. depression, anxiety and somatization) of the Dutch translation of the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI-18; De Beurs, Citation2011; Derogatis, Citation2001). Participants rated 18 items like “Nervousness or shakiness inside” and “Feelings of worthlessness” from 0 (never experience symptom) to 4 (very often experience symptom). Cronbach's α for the sub-scale depression was 0.84 at baseline and 0.78 at follow-up, for the sub-scale anxiety 0.90 at baseline and 0.78 at follow-up, and for the sub-scale somatization 0.83 both at baseline and at follow-up. Participants were divided into two groups based on norm scores for the Dutch population (De Beurs, Citation2011). Participants were categorized as having a high level if they scored in the upper 20th percentile on the sub-scales compared with a Dutch community sample (De Beurs, Citation2011). Excessive alcohol use was assessed with 2 items: How many days during the past 30 days did you drink (1) at least 1 unit of alcohol? and (2) at least 5 units of alcohol? From these two items a score was deduced indicating the minimum alcohol intake during the past 30 days. Note, because of this deduced calculation, the number of alcohol units consumed will most probably be an underestimation. Participant’s alcohol intake was considered as excessive at 60 units or more for women and 90 units or more for men, following the guidelines of the Dutch Trimbos Institute (Citation2018). Excessive cannabis use was measured with one item: “How many days did you use cannabis during the past 30 days?”. Participants who used cannabis for at least 20 days during the past month were considered to excessively use cannabis. No other substances were taken into account due to the low prevalence rates (<5%) per type of hard drugs in this population (Van Straaten et al., Citation2016). In total, 17.4% of people had been using some type of hard drugs (i.e. crack cocaine, ecstasy, cocaine, amphetamines, heroin, methadone, other opiates, hallucinogens, solvents, GHB, or other) during the last 30 days at T0.

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Missing values on items of a scale were substituted with the mean score of the other items on that scale for the participant when missing variables did not exceed 30% of the scale. If a scale consisted of five items or less, we used 20% as the cutoff point. Descriptive analyses were performed to describe the socio-demographic characteristics and the prevalence of the risk factors for homelessness at baseline and the follow-up after 5.5 years.

To analyze changes in the prevalence of risk factors for homelessness between the baseline measurement and the 5.5-year follow-up, a McNemar test was used.

Results

Demographics

At follow-up (T1, n = 72), participants’ age ranged from 18 to 71 years old (M = 43.6, SD = 13.1), most participants were male (79.2%), single (62.5%), had one or more children (60.3%), and 65.6% reported completing at most the equivalent of high school education (see ).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of all participants at T1 (n = 67–72).

Housing status

The median duration of lifetime homelessness was 32 months (ranging from 1.5 month to 324 months).

At baseline, none of the participants were stably housed. At 5.5 year follow-up, 50 participants (69.4%) were stably housed. The unstably housed participants (n = 22) were residing in an institution (20.8%, e.g. residential shelters), were marginally housed (4.2%; e.g. staying temporarily with friends, relatives or acquaintances), were homeless (4.2%; e.g. staying in a night shelter, transitional accommodation or sleeping rough) or staying in a psychiatric hospital (1.4%).

Risk factors for homelessness at shelter entry

shows the prevalence of risk factors for homelessness at shelter entry (T0) and 5.5 years later (T1), clustered in the four constitutional conditions of the SQA.

Table 2. Prevalence of risk factors for homelessness and changes in this prevalence between shelter entry (T0) and 5.5 years later (T1) among the initially homeless people.

Regarding living conditions, at T0, most participants were unemployed (75.0%), almost all participants had debts (91.7%) and between one third (33.8%) to two thirds (66.2%) of the participants did not have enough money for basic needs such as food and clothing.

Concerning interpersonal embeddedness, at T0, more than half of the participants experienced poor quality in their relationships with family members (52.2%), almost one fifth reported poor relationships with friends and acquaintances (18.2%) and more than one third experienced poor relationships with their child(ren) (35.7%). The majority of participants lacked support from family members (70.0%), over half lacked support from friends and acquaintances (51.4%), and a small group (12.9%) lacked support from their partner.

Regarding societal embeddedness, at T0, around one in ten participants reported an unmet care need regarding finances (11.3%) and social contacts (9.9%), almost one fifth reported an unmet care need regarding mental health (19.4%), a quarter of the participants reported an unmet care need regarding physical health (25.0%), and around one third reported an unmet care need regarding finding work (32.4%) and dental health (38.9%). More than half of the participants had been arrested or picked-up for criminal activity during the preceding year (52.8%).

Concerning self-regulation, at T0, over one third of the participants reported four or more physical health problems (35.2%), a quarter was dissatisfied with their physical health (25.0%), and between one third and a half of the participants experienced high levels of depression (45.8%), anxiety (37.5%) and somatization (45.8%). A small (9.7%), but probably underestimated group, was considered to be using alcohol excessively and over one third of the participants used cannabis excessively (38.0%).

Changes in prevalence of risk factors for homelessness

The prevalence of the majority of risk factors did not significantly change in all four constitutional conditions of social quality between shelter entry and 5.5 years later (see ). Regarding living conditions, this concerns unemployment (75.0% versus 76.4%, p = 1.0), not having enough money for basic needs such as food (33.8% versus 23.6%, p = .28), travel (43.1% versus 44.4%, p = 1.0), clothing (64.8% versus 61.1%, p = .84) and social activities (66.2% versus 52.8%, p = .14). With regard to interpersonal embeddedness, this applies to poor relationships with and lack of support from friends and acquaintances (18.2% versus 11.9%, p = .45 and 51.4% versus 40.3%, p = .17), poor relationships with children (35.7% versus 22.2%, p = .22) and lack of support from partner (12.9% versus 7.4%, p = 1.0). Regarding societal embeddedness, the prevalence of unmet care needs regarding finances (11.3% versus 9.7%, p = 1.0), finding work (32.4% versus 22.5%, p = .33), social contacts (9.9% versus 4.2%, p = .34) and mental health (19.4% versus 9.7%, p = .17) did not significantly decrease between T0 and T1. Concerning self-regulation, the prevalence of the following risk factors did not decrease significantly: symptoms of depression (45.8% versus 43.1%, p = .85), anxiety (37.5% versus 26.4%, p = .15) and somatization (45.8% versus 34.7%, p = .13), and excessive cannabis use (38.0% versus 34.4%, p = .8).

However, significant improvements did take place in all four constitutional conditions of social quality (see ). Regarding living conditions, there was a significant decrease in the number of people with debts (91.7% versus 57.7%, p = .00) and with insufficient money for housing (38.6% versus 15.3%, p = .01). Concerning interpersonal embeddedness there was a significant decrease in the number of people with poor quality relationships with and lack of support from family members (52.2% versus 24.6%, p = .00 and 70.0% versus 47.2%, p = .01). Regarding societal embeddedness, fewer people were arrested for criminal activity (52.8% versus 12.5%, p = .00) and fewer people reported an unmet care need regarding physical health (25.0% versus 12.5%, p = .05) and dental health (38.9% versus 16.7%, p = .00). Concerning self-regulation, fewer people reported four or more physical complaints (35.2% versus 30.6%, p = .05). Nevertheless, some of the risk factors that did decrease significantly over time, were still highly present among the participants 5.5 years after shelter entry. For example, after 5.5 years, 57.7% of the participants still had debts, 47.2% still reported a lack of support from family members, and 30.6% reported four or more physical health problems.

Discussion

This study examined the prevalence of risk factors for homelessness at shelter entry and changes in the prevalence of these risk factors among homeless people over a period of 5.5 years. The biographical characteristics of the study sample concurs with previous research in Dutch homeless populations, by demonstrating an overrepresentation of men, people with a low educational level and migrant background (Van Everdingen et al., Citation2023; Verheul et al., Citation2020). At baseline, none of the participants were stably housed and, as expected, were seriously disadvantaged regarding all four constitutional conditions of social quality. As described in the introduction, the variables included in this study were based on current knowledge on individual modifiable risk factors for homelessness. By demonstrating poor outcomes on those risk factors at baseline, the results of this study further validate the knowledge on individual modifiable risk factors for homelessness. These outcomes are also in line with previous research in Dutch homeless populations, demonstrating, for example, high needs regarding mental health, physical health, and paid work (Van Everdingen et al., Citation2023) and finding high percentages of people who reported, for example, having debts and health problems, and feeling lonely, sad and depressed (Verheul et al., Citation2020).

At the 5.5 year follow-up, most participants were stably housed, our findings demonstrate improvements across all measured domains of social quality, without evidence of any worsening conditions. We found a statistically significant decrease in the number of people with debts, insufficient money for housing, and a poor quality of relationships with and lack of support from family members. Significantly fewer people were arrested for criminal activity, fewer people reported four or more physical complaints and unmet care need with regard to physical and dental health. However, despite these improvements, the prevalence of the majority of risk factors did not significantly change after 5.5 years, such as unemployment, not having enough money for basic needs such as food and clothing, lack of support from friends and acquaintances, unmet care needs regarding finding work, and symptoms of depression, anxiety and somatization. In addition, some of the risk factors that did decrease significantly over time, were still frequently reported by the participants. For example, after 5.5 years, more than half of the participants still had debts, almost half still reported a lack of support from family members, and almost one third reported four or more physical health problems.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that longitudinally assessed the prevalence of individual, modifiable risk factors for homelessness. Figures on the general adult population in the Netherlands show that, even 5.5 years after shelter entry, the participants were substantially worse off regarding the quality of their daily lives. Compared to the general population, they were much more likely to, for instance, be unemployed (76% versus 33%; Statistics Netherlands, Citation2017), have insufficient money for food (24% versus 3%; Statistics Netherlands, Citation2017) and clothing (61% versus 16%; Statistics Netherlands, Citation2017), experience high levels of depression (43% versus 20%; De Beurs, Citation2011), and excessively use cannabis (34% versus 1%; Trimbos Instituut, Citation2016).

Implications for practice

Although significant improvements took place 5.5 years after shelter entry, the majority of the participants are still disadvantaged on all four constitutional conditions of social quality, and therefore remain relatively vulnerable for recurrent homelessness. Policy makers should be more aware of the persistent vulnerability regarding the living circumstances formerly homeless people find themselves in. They should, for example, enable service providers to support this group for as long as necessary to assure that formerly homeless people achieve and retain stable housing and ensure that they can fully participate in society. Although previous research has identified quite a few risk factors for recurrent homelessness, it remains very difficult to accurately predict who will become homeless again after being housed at an individual level (De Vet, Citation2019; Volk et al., Citation2016). Therefore, providing appropriate services to all individuals who make the transition from a homeless shelter to independent housing remains the most viable strategy.

Furthermore, the results of this study urge service providers and policy makers to structurally enhance the constitutional conditions for “a good life” in order to prevent recurrent homelessness. Findings indicate that more and specific attention should be paid to improving formerly homeless people’s socio-economic security, for example via sufficient income support, adequate debt relief programs, and support in finding a job. More awareness for the need to improve formerly homeless people’s poorer health seems to be essential, for example by ensuring proper access to appropriate mental health care and physical health care. Particular attention should also be paid to improve the quality of their social relations, for example through support programs to strengthen family ties.

Strengths and limitations

The present study has a number of strengths. First of all, to our knowledge, this is the first study that longitudinally assesses the prevalence of a comprehensive set of individual, modifiable risk factors for homelessness in the lives of homeless people. Also, the participants were followed for a relatively long period of time (5.5 years), which is a challenge within homeless populations, because of tracking difficulties such as frequent moves and changing contact details (Stefancic et al., Citation2004).

This study also has several limitations. First, despite the tracking strategies described in the method’s section, participant loss at follow-up was high (58%). Although no differences were found regarding various variables between participants who only completed the questionnaire at baseline compared to participants who completed both questionnaires, it is unknown whether and how the loss of participants may have biased our findings, as we lack information on the change variables of the non-respondents. There also might be unmeasured confounders that could differentiate those that completed the second interview versus those that did not. It is also unknown whether initial sample selection may have biased our results. Not all people may have seen the recruitment materials or gotten a face-to-face interaction and there may be differences between those who self-selected to participate versus those who did not. Furthermore, some results are likely to underestimate the prevalence of certain risk factors. For example, the use of the mean number of physical complaints from data regarding an already vulnerable group as a cutoff score, probably led to an under-representation of people with a high level of physical complaints. And, as already mentioned in the method’s section, the way the number of alcohol units consumed was measured, probably led to an underestimation of the prevalence of excessive alcohol use. Another limitation related to the design of the study concerns the effect of “regression to the mean”. The baseline interviews were conducted shortly after a period of literal homelessness. Therefore, it can be expected that, because of their stabilized housing situation, most participants would have improved on most outcome measures by the time of the follow-up interviews. Because stable housing is a critical starting point for overall social quality enhancement, we should be hesitant to attribute improvements in the four constitutional conditions of social quality to professional support or policies.

Another methodological issue concerns the external validity of the results. The criteria for entering the social relief system in the G4 in the Netherlands in 2011 were used as inclusion criteria for this study. Therefore, a substantial part of the homeless population is covered by this selection criterion. Subgroups not included in this study were undocumented homeless people and homeless people who do not make use of social relief facilities. The prevalence of risk factors may differ for those subgroups that were not allowed to enter the social relief system. Also, the study sample was primary male (79.2%), and thus does not equally represent the prevalence of risk factors for homelessness for women. Previous research found that women who were about to move from shelter to (independent) supported housing were disadvantaged regarding many factors of social quality, compared to men (De Vet et al., Citation2019). Based on this previous research, the results of the current study might, for example, underestimate the prevalence of risk factors for women. However, due to the small sample size we were unable to statistically test this.

Another limitation of our study is that we lacked information on the contents of the individual program plans the participants received during the 5.5 years in between the two measurements. Future longitudinal research should take into account the kind of support provided between T0 and T1. Future research should also consider stratifying participants by housing status to disentangle which aspects of social quality specifically contribute to stable housing or vice versa.

Last, it is worth mentioning that the data analyzed within this study were collected between 2011 and 2017. Statistics Netherlands (SN) estimates that the number of homeless people has significantly increased in the past decade (Statistics Netherlands, Citation2016, Citation2019) due to changes in social policy, the social relief system and the housing market and recent research indicates that these SN-figures are likely even an underestimation of the actual number of homeless people (Wewerinke et al., Citation2023). This indicates that the results of this study may even be more relevant in the present-day.

Conclusion

This study shows that, although broad improvements across all measured domains of social quality took place 5.5 years after shelter entry, the personal situation of Dutch people who were initially homeless lagged behind, especially compared to the general Dutch population. This shows that they are exposed to higher levels of social exclusion, leaving them particularly vulnerable for a new episode of homelessness. Flexible and accessible support aimed at long term housing stability and a good quality of daily life should be made available as long as necessary.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Jorien Van der Laan, Dike van de Mheen and Judith Wolf. Data analysis were performed by Sandra Schel. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Sandra Schel and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent

The authors have complied with the APA ethical principles in the treatment of the research participants, and all participants gave written informed consent.

Ethics approval

This study was exempt from formal review by an accredited Medical Review Ethics Committee region Arnhem-Nijmegen (file number 2010-321).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data sharing and data availability statement

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sandra H. H. Schel

Dr. Sandra Schel is a researcher at the research group Housing and Welfare at Utrecht University of Applied Sciences in The Netherlands. This research group focuses on homelessness, housing and support, Housing First and innovative housing concepts for people with support needs. In 2008 she obtained her master’s degree in Clinical Psychology and Industrial and Organizational Psychology from the Radboud University in Nijmegen. After her study, she started working as a psychologist at Overwaal, Centre for Anxiety Disorders and PTSD. From 2012 she worked as a researcher at Forensic Psychiatric Hospital the Pompefoundation. In 2024 she completed a PhD project at the Radboud university medical center in Nijmegen, The Netherlands on what is needed to structurally enhance the living conditions of people living in vulnerable conditions. She currently works as a researcher at the University of Applied Sciences Utrecht.

Linda van den Dries

Dr. Linda van den Dries is a senior researcher at Impuls – Netherlands Center for Social Care Research at the Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, at the Radboud university medical center in Nijmegen, The Netherlands. She obtained her master’s degree in child psychology from the Radboud University in Nijmegen and completed a PhD in child development at Leiden University.

Jorien Van der Laan

Dr. Jorien van der Laan obtained her bachelor’s degree in Social Psychology at Utrecht University (2007), a research master’s in Psychology and Health (2009), and a master’s degree (cum laude) in Social Policy and Social Interventions (2010). In 2020, she completed a PhD on a cohort study on homeless people in the four major cities in the Netherlands, entitled: “Giving voice to homeless people: Homeless people’s personal goals, care needs and quality of life in the Dutch social relief system”. From 2014 to 2021 Jorien also worked as a senior researcher at the lectorate Poverty Interventions of the Amsterdam School for Applied Research. There she was a project manager for research which aims to improve debt relief and poverty reduction programs. In addition, she taught and developed courses on themes related to poverty and poverty reduction at the Faculty for Applied Social Sciences and Law. She currently works as a developer at Community Social Work Utrecht.

Dike van de Mheen

Prof. Dr. Dike van de Mheen was born in 1963, finished high school in 1982 and studied Health Sciences until 1987. Here PhD thesis about “Socio-economic health differences during the life-course” was successfully defended in 1998. From 1987–1988 she worked as researcher with the Rotterdam Area Health Authority. This was followed by an appointment as researcher and assistant professor at the Erasmus University Rotterdam (Department of Public Health) from 1988 until 1999. During 1998 and 1999 she was senior adviser at the Rotterdam Area Health Authority. From 1999 until 2017 she was Director of Research and Education at the IVO Addiction Research Institute Rotterdam. She has extended experience in research (both quantitative and qualitative) on drug and alcohol related issues. Since April 2007 until September 2017 she was professor “Addiction Research” at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam. From 2012–2016 she was also professor “Care and prevention of risky behaviour and addiction” at Maastricht University. Starting 15 December 2016 she is Professor Transformations in Care and head of the Department Tranzo, Scientific Center for Care and Welbeing, School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Tilburg University.

Judith R.L.M. Wolf

Prof. Dr. Judith Wolf is Professor of Social Care and head of Impuls, the Netherlands Center for Social Care Research, at Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center. She is also director of the Academic Collaborative Center Impuls: Participation and Social Care. She has more than 30 years of experience in conducting both academic and applied research on people with complex, multiple problems in the margins of society as well as on the their care needs and the social and health care services needed by these people.

References

- Barile, J. P., Pruitt, A. S., & Parker, J. L. (2018). A latent class analysis of self-identified reasons for experiencing homelessness: Opportunities for prevention. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 28(2), 94–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2343

- Benjaminsen, L. (2016). Homelessness in a Scandinavian welfare state: The risk of shelter use in the Danish adult population. Urban Studies, 53(10), 2041–2063. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015587818

- Bramley, G., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2018). Homelessness in the UK: Who is most at risk? Housing Studies, 33(1), 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1344957

- Czaderny, K. (2020). Risk factors for homelessness: A structural equation approach. Journal of Community Psychology, 48(5), 1381–1394. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22332

- De Beurs, E. (2011). Brief symptom inventory/brief symptom inventory 18 Handleiding. PITS B.V.

- Derogatis, L. R. (2001). Brief symptom inventory (BSI)-18. Administration, scoring and procedures manual. NCS Pearson Inc.

- De Vet, R. (2019). Effectiveness of critical time intervention for homeless people: A randomized controlled trial to enhance continuity of care during the transition from shelter to community living [Doctoral dissertation]. Radboud University Nijmegen]. https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/213934/213934.pdf

- De Vet, R., Beijersbergen, M. D., Lako, D. A., van Hemert, A. M., Herman, D. B., & Wolf, J. R. (2019). Differences between homeless women and men before and after the transition from shelter to community living: A longitudinal analysis. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(5), 1193–1203. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12752

- Doran, K. M., Ran, Z., Castelblanco, D., Shelley, D., & Padgett, D. K. (2019). “It wasn't just one thing”: A qualitative study of newly homeless emergency department patients. Academic Emergency Medicine, 26(9), 982–993. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13677

- Edgar, B., Harrison, M., Watson, P., & Busch-Geertsema, V. (2007). Measurement of homelessness at European Union level. European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/employment_social/social_inclusion/docs/2007/study_homelessness_en.pdf

- Fazel, S., Geddes, J. R., & Kushel, M. (2014). The health of homeless people in high-income countries: Descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet (London, England), 384(9953), 1529–1540. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61132-6

- Finlay, W. M. L., & Lyons, E. (2001). Methodological issues in interviewing and using self-report questionnaires with people with mental retardation. Psychological Assessment, 13(3), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.13.3.319

- Fondation Abbé Pierre – FEANTSA. (2018). Third overview of housing exclusion in Europe 2018. https://www.feantsa.org/download/full-report-en1029873431323901915.pdf

- Fondation Abbé Pierre – FEANTSA. (2019). Fourth overview of housing exclusion in Europe 2019. https://www.feantsa.org/download/oheeu_2019_eng_web 512064608 n79 93915253.pdf

- Georgiades, S. (2015). The dire straits of homelessness: Dramatic echoes and creative propositions from the field. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 25(6), 630–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2015.1011254

- Grattan, R. E., Tryon, V. L., Lara, N., Gabrielian, S. E., Melnikow, J., & Niendam, T. A. (2022). Risk and resilience factors for youth homelessness in western countries: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 73(4), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000133

- Instituut, Trimbos. (2016). Nationale Drug Monitor: jaarbericht.

- Levy, B. D., & O’Connell, J. J. (2004). Health care for homeless persons. The New England Journal of Medicine, 350(23), 2329–2332. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp038222

- Mabhala, M. A., Yohannes, A., & Griffith, M. (2017). Social conditions of becoming homelessness: Qualitative analysis of life stories of homeless peoples. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0646-3

- Nilsson, S. F., Nordentoft, M., & Hjorthøj, C. (2019). Individual-level predictors for becoming homeless and exiting homelessness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Urban Health, 96(5), 741–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00377-x

- Orwin, R. G., Scott, C. K., & Arieira, C. (2005). Transitions through homelessness and factors that predict them: Three-year treatment outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 28(2 SUPPL.), S23–S39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.011

- Piat, M., Polvere, L., Kirst, M., Voronka, J., Zabkiewicz, D., Plante, M.-C., Isaak, C. A., Nolin, D., Nelson, G., & Goering, P. (2015). Pathways into homelessness: Understanding how both individual and structural factors contribute to and sustain homelessness in Canada. Urban Studies, 52(13), 2366–2382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014548138

- Schreiter, S., Speerforck, S., Schomerus, G., & Gutwinski, S. (2021). Homelessness: Care for the most vulnerable – a narrative review of risk factors, health needs, stigma, and intervention strategies. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 34(4), 400–404. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000715

- Sherbourne, C. D., & Stewart, A. L. (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science and Medicine, 32(6), 705–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B

- Statistics Netherlands [Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek]. (2016). Aantal daklozen in zes jaar met driekwart toegenomen [Number of homeless people increased by three quarters in six years]. Retrieved April 30, 2017, https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2016/09/aantal-daklozen-in-zes-jaarmet-driekwart-toegenomen

- Statistics Netherlands [Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek]. (2017). CBS Statistics, www.cbs.nl/statline

- Statistics Netherlands [Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek]. (2019). Aantal daklozen sinds 2009 meerdan verdubbeld [Number of homeless people more than doubled since 2009]. Retrieved March 20, 2020, https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2019/34/aantal-daklozen-sinds-2009-meer-danverdubbeld

- Stefancic, A., Schaefer-McDaniel, N. J., Davis, A. C., & Tsemberis, S. (2004). Maximizing follow-up of adults with histories of homelessness and psychiatric disabilities. Evaluation and Program Planning, 27(4), 433–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.07.006

- Trimbos Instituut. (2018). Factsheet riskant alcoholgebruik in Nederland.

- Tsai, J., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2015). Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiologic Reviews, 37(1), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxu004

- Van den Dries, L., Peters, Y., Al Shamma, S., & Wolf, J. (2018). Dakloze mensen in Amsterdam: veranderingen in 5,5 jaar na instroom in de opvang. Resultaten uit de vervolgmeting Coda-G4 in Amsterdam. Impuls Onderzoekscentrum maatschappelijke zorg, Radboudumc.

- Van der Laan, J. (2020). Giving voice to homeless people: Homeless people’s personal goals, care needs, and quality of life in the Dutch social relief system [Doctoral dissertation]. Radboud University. https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/220351/220351.pdf

- Van der Maesen, L. J. G., & Walker, A. (Eds.). (2012). Social quality: From theory to indicators. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230361096.

- Van Everdingen, C., Peerenboom, P. B., Van der Velden, K., & Delespaul, P. (2023). Vital needs of Dutch homeless service users: Responsiveness of local services in the light of health equity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 31-20(3), 2546. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032546

- Van Straaten, B., Rodenburg, G., Van der Laan, J., Boersma, S. N., Wolf, J. R. L. M., & Van de Mheen, D. (2016). Substance use among Dutch homeless people, a follow-up study: Prevalence, pattern and housing status. The European Journal of Public Health, 26(1), 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv142

- Van Straaten, B., Van der Laan, J., Rodenburg, G., Boersma, S. N., Wolf, J. R., & Van de Mheen, D. (2017). Dutch homeless people 2.5 years after shelter admission: What are predictors of housing stability and housing satisfaction? Health and Social Care in the Community, 25(2), 710–722. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12361

- Verheul, M., Laere, I. V., Muijsenbergh, D. M., & Genugtenc, W. V. (2020). Self-perceived health problems and unmet care needs of homeless people in The Netherlands: The need for pro-active integrated care. Journal of Social Intervention: Theory and Practice, 29(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.18352/jsi.610

- Volk, J. S., Aubry, T., Goering, P., Adair, C. E., Distasio, J., Jette, J., Nolin Danielle, Stergiopoulos Vicky, Streiner David L., & Tsemberis, S. (2016). Tenants with additional needs: When housing first does not solve homelessness. Journal of Mental Health, 25(2), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1101416

- Wewerinke, D., Schel, S., Kuijpers, M., De Vries, J., & Van Doorn, L. (2023). Iedereen telt mee. Resultaten eerste ETHOS telling dak- en thuisloosheid regio Noordoost Brabant. Hogeschool Utrecht.

- Wolf, J., Zwikker, M., Nicholas, S., Van Bakel, H., Reinking, D., & Van Leiden, I. (2002). Op achterstand. Een onderzoek naar mensen in de marge van Den Haag. Trimbos-Instituut.

- Wolf, R. L. M., & Jonker, I. E. (2020). Pathways to empowerment: The social quality approach as a foundation for person-centered interventions. The International Journal of Social Quality, 10(1), 29–56. https://doi.org/10.3167/IJSQ.2020.100103

- World Health Organisation. (1994). International classification of diseases (ICD). WHO.

Appendix

Table 1. Background characteristics at T0 of the respondents and non-respondents at T1.