There is a prophet within us, forever whispering that behind the seen lies the immeasurable unseen.

–Frederick DouglassFootnote1

Introduction

David Chadwick was “an international pioneer in identifying, treating and preventing child abuse and a recognized expert in the field who started a movement”Footnote2 which included a call to end child abuse. Led by Dr. Chadwick, San Diego’s Children’s Hospital and Health Center - San Diego (CHHC) created the National Call to Action: A Movement to End Child Abuse and Neglect (NCTA).Footnote3 This initiative organized a coalition of more than 30 national organizations, and 3,000 child abuse professionals, community leaders, and survivors of child abuse with the goal of significantly reducing child abuse in the United States. This would be accomplished, in part, by identifying political champions, the use of science to evaluate practice and policy, and the reallocation of resources to proven prevention initiatives.Footnote4

Dr. Chadwick and the NCTA boldly asserted we could end child abuse within a century but to do so would:

[R]equire keepers of a plan who will devote many decades of their lives to the effort. The keepers will keep the message alive. It will take sweat and tears. These keepers must recruit successors with similar dedication. Who, among you, are the keepers? Who will be willing to step forward and work tirelessly to keep the message alive?Footnote5

Others agreed with Chadwick’s lofty vision. For instance, Anne Cohn Donnelly saw the potential of Chadwick’s call to action but warned it would mean a commitment exceeding a lifetime. According to Donnelly, ending child abuse will require “adopting a far longer view than we have historically held, such as planning out our efforts over decades, not years, and likewise measuring our success over decades, not years. This new approach will require flexibility and a great deal of patience. But in my own view, it is possible.”Footnote6 When Donnelly writes it is “possible” to end child abuse she concedes this may not literally be achievable “but rather that we do have it within us to bring about very significant reductions in child maltreatment over the long haul.”Footnote7

Using Dr. Chadwick’s “National Call to Action” as a foundation, Victor Vieth (hereinafter identified as the first author) wrote a scholarly paper called “Unto the Third Generation: A Call to End Child Abuse in the United States within 120 Years.” The article drew on nearly 20 (now 37) years of experience collaborating with a wide range of professionals dedicated to fighting child maltreatment, including social workers, law enforcement officers, prosecutors, pediatricians, nurses, mental health professionals, clergy, and others. The article was originally written in 2005Footnote8 and a revised and expanded version was published a year later.Footnote9 The National Child Protection Training Center mailed the revised article to thousands of child protection professionals throughout the United StatesFootnote10 and the first author presented the plan in keynote addresses at national and state conferences over a period of several years.Footnote11

As reflected in the title, Unto the Third Generation proposed a plan of action that would unfold over the course of a century. Specifically, the plan involved a series of concrete steps to accomplish over a period of three generations—with each generation consisting of 40-year periods. The paper set forth reforms to be accomplished in the first 40-year generation and then said succeeding generations would have to develop their own 40-year plans to build on these successes.

At the time of its publication, David Chadwick himself recognized the potential of Unto the Third Generation, writing for “the first time in history, we are presented with a blueprint for accomplishing the goal of ending child abuse and are given an estimate of the time required.”Footnote12 Chadwick not only called the proposed reforms “very substantial” but said they “will dwarf present efforts, and require a societal commitment greater than the war on cancer and comparable in cost to the exploration of space.”Footnote13

It has been nearly 20 years since the publication of Unto the Third Generation—approximately half-way through the first of three 40-year plans. In this paper, we review the recommendations of Unto the Third Generation, detail the significant reforms the article inspired, and also discuss where the article fell short and needs revision. Most importantly, this article discusses whether or not Unto the Third Generation has contributed to a reduction of child abuse in the United States or has at least set a foundation which can achieve the ultimate goal.

The five barriers identified in Unto the Third Generation

Unto the Third Generation detailed five barriers to reducing child abuse.

First, the article noted that “many children suspected of being abused are not reported into the system” and cited a number of studies supporting this conclusion.Footnote14 Approximately five years after the publication of Unto the Third Generation, the failure of even well-educated and powerful professionals to report clear evidence of child sexual abuse was made clear in the scandal at Penn State University.Footnote15 As summarized by one national media source:

(T)he 23-page grand jury report is littered with instances in which university officials and other authorities failed to act, effectively allowing the list of victims to grow.Footnote16

A core reason that even well-educated mandated reporters fail to report clear evidence of maltreatment is poor education—something which may have played a role in the Penn State scandal. In a survey of 1,400 mandated professionals from 54 counties in Pennsylvania, 14% said they had never received mandated reporter training.Footnote17 Another 24% said they had not received mandated reporter training in the past five years.Footnote18 The professionals that had received training on their obligations as mandated reporters, may not have received quality training. Approximately 80% of the respondents to the survey said their training was not approved for continuing education units or they were uncertain.Footnote19

Second, Unto the Third Generation noted that most cases of child abuse are never investigated and cited national data that CPS investigation extends to “only slightly more than one-fourth of the children who were seriously harmed or injured by abuse or neglect.”Footnote20 As one example, cases of child torture are among the most egregious forms of abuse and yet research finds they are often screened out or are poorly investigated.Footnote21

Third, Unto the Third Generation found that “even when cases are investigated, the investigators and other front-line responders are often inadequately trained and inexperienced.”Footnote22 The article cited a number of studies documenting the failure of colleges, universities and graduate programs to adequately prepare social workers, criminal justice professionals, prosecutors (and all lawyers), as well as medical and mental health professionals to recognize and respond to child abuse.Footnote23 In the nearly two decades after the publication of Unto the Third Generation, the research on inadequate undergraduate and graduate training continued to grow.Footnote24 As will be noted below, the reference to poor training of professionals responding to child abuse became the catalyst for perhaps the most transformational reform spurred by the article—the dramatic improvement of undergraduate and graduate training for future child protection professionals.

Fourth, Unto the Third Generation noted that even when an investigation results in significant evidence of abuse and civil or criminal justice professionals are able to intervene, “the child is typically older and it is more difficult to address the physical, emotional and other hardships caused by the abuse.”Footnote25 A large body of researchFootnote26 makes clear the critical importance of preventing childhood trauma and, where it cannot be prevented, addressing the impact as soon as possible.Footnote27

Finally, Unto the Third Generation found that because “the child protection community lacks a unified voice in communicating the needs of maltreated children, these victims receive an inadequate share of our country’s financial resources.”Footnote28 As a result, we invest far too little in the prevention of child abuse and are often relegated to addressing the suffering of children on the back end of the crisis.

The plan of action proposed in Unto the Third Generation

To address the failure of mandated reporters to report even clear cases of maltreatment, Unto the Third Generation said that “every university must teach students entering mandated reporting professions the necessary skills to competently perform this task” and that this education must be followed up with annual, ongoing education.Footnote29

Next, Unto the Third Generation asserted that everyone called on to respond to an allegation of abuse must be “competent” to do so. This article again called on universities as well as graduate programs to dramatically improve undergraduate and graduate training of future child protection professionals. It outlined a three-course model which would be experiential and would have social work, criminal justice, nursing, psychology and other students from diverse disciplines in the same classes together.Footnote30 The article also proposed graduate courses on child maltreatment at medical schools, law schools, seminaries, dental schools, and veterinary schools. It even included journalism schools in the hope that journalists could better educate the public about child maltreatment.Footnote31

The article did not ignore the educational need of professionals in the field. Unto the Third Generation urged that the nation shift from forensic interview training offered by only a handful of national course offerings—which made the education inaccessible to most child protection professionals—to state-run courses that met national standards.Footnote32 The article also noted that “not every child will respond well to a forensic or investigative interview” and it was critical to develop extended evaluation models and alternative methods of assessing an allegation of abuse.Footnote33

Unto the Third Generation emphasized experiential trainings. Specifically, the article proposed that universities develop mock houses and other facilities that could be used both for experiential training in undergraduate and graduate courses and for instruction of multidisciplinary teams in the field.Footnote34

Unto the Third Generation did not propose a specific set of prevention initiatives but instead proposed a process by which prevention efforts could take root in every community in the country. Again emphasizing the role of higher education, the article urged universities to “equip future social workers, police officers and other child protection professionals to be community leaders who proactively seek to prevent child abuse.”Footnote35 The article proposed experiential exercises in which future child protection professionals identified risk factors for abuse in a given community and then developed concrete steps to address these risk factors.Footnote36 “In teaching students the art of prevention,” the article contended, “a sea of front line professionals will be able not only to initiate new reforms but to complement existing and promising practices such as home-based services aimed at preventing abuse in at-risk families.”Footnote37 In order for prevention to be effective, Unto the Third Generation noted the diversity of the nation and the numerous factors contributing to maltreatment. Accordingly, the article emphasized that “prevention efforts must be locally run and tailored to local needs.”Footnote38

As child protection professionals became community leaders in preventing maltreatment, Unto the Third Generation concluded it was critical to enlist the support of faith leaders.Footnote39 The article said that child protection professionals may have to address the religious beliefs of a family on such issues as the use of corporal punishment.Footnote40 Beyond this, Unto the Third Generation asserted that the faith community “can play an important role in protecting children” and in providing a “moral backbone” to the movement to end child abuse—just as it had for the civil rights movement.Footnote41

Unto the Third Generation contended that the culture of the United States permitted a high rate of child maltreatment. We had created a society where mandated reporters were poorly skilled to recognize and report abuse, where universities saw little need to graduate child protection professionals who are competent to perform their work, where prevention was an afterthought and seldom an emphasis of child protection professionals, and where public policy makers never had a platform on responding to child maltreatment because no voter insisted on them engaging with this issue. In changing this culture, Unto the Third Generation argued, we would reach a “tipping point” of reform in which child abuse would naturally begin to decline. In continuing with this approach for three generations, child abuse could be reduced to very small levels.Footnote42

The Impact of Unto the Third Generation on the Field of Child Protection

In 2017, Hinds and Giardino referred to Unto the Third Generation as one of the “most highly recognizable” child abuse prevention plans published in the past quarter of a century.Footnote43 A discussion of the plan also began to appear in academic textbooksFootnote44 and other scholarly works.Footnote45 More important than its recognition, though, is the actual impact Unto the Third Generation had on the child protection system and the lives of children in harm’s way. Discussed below is the national and international impact of Unto the Third Generation.

From Finding Words to ChildFirst: the shift from national to state forensic interview training

In the late 1990’s there were a handful of forensic interview training programs. Although these programs were of a high quality, they could not be accessed by most frontline child protection professionals. To address this need, the National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse (NCPCA) and CornerHouse developed a forensic interview training program called Finding Words and offered to pay the expenses of those who could not otherwise afford the travel.Footnote46

The first time Finding Words was offered, more than 400 professionals applied for a course that teaches a maximum of forty students. As a result, NCPCA applied for and received a grant from the United States Department of Health and Human Services to assist states in developing a locally administered and locally taught version of the program.Footnote47 As a result of this initiative. Finding Words became a “very influential” forensic interview training model that is “among the most widely trained interview structures in the United States.”Footnote48

Although Finding Words was already in place before the publication of Unto the Third Generation, the article spurred greater attention to the benefit of forensic interviewing courses taught at the state level. Of the 21 states which eventually adopted the model, 12 of them came into the program after the publication of the article.

The program is now called ChildFirst and, in alphabetical order, the states adopting the model are: Alaska, Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia.Footnote49 Even states that did not adopt ChildFirst were influenced to implement state forensic interview training programs—thus resulting in a significant shift from national to state level training. In the context of Unto the Third Generation, this shift was important because it meant many more professionals could access forensic interview training. Given the critical role of the forensic interview in responding to child abuse, more children would be protected from abuse and more offenders would experience justice. ChildFirst also became a leading model in the nations of Colombia and Japan—where it also influenced the development of a Children’s Advocacy Center.Footnote50 As of this writing, there is also an emerging ChildFirst program in Nigeria, further solidifying the international impact of the initiative.

Of course, ChildFirst is not the nation’s only forensic interview training program and there are several models approved by the National Children’s Alliance for working as a forensic interviewer in an accredited Children’s Advocacy Center. In 2015, representatives of ChildFirst and other leading models authored a publication showing widespread agreement among the nation’s leading courses as to best practices for forensic interviewing.Footnote51

In addition to expanding the access of frontline professionals to forensic interview training, ChildFirst impacted the field in at least three other ways: polyvictimization screening, the use of media in forensic interviews, and the recognition of forensic interviewers as expert witnesses in courts of law on a wide range of topics.

Polyvictimization Screening

In 2013, CornerHouse developed a new forensic interview protocol and, in turn, Zero Abuse Project worked with the ChildFirst states to develop and implement its own protocol. The new ChildFirst protocol incorporates features that are common to all major models but added a polyvictimization screen for all forms of abuse irrespective of the presenting allegation.Footnote52 This important reform is based on the recognition that most children who are abused in one way are often abused in multiple waysFootnote53 and that polyvictims often experience heightened trauma.Footnote54 Accordingly, it is necessary to have a more holistic approach to the forensic interview.

In addition to getting a more complete picture of the trauma a child has experienced, polyvictimization screening may be able to identify and protect more children than previous forensic interviewing models. This is because most children delay disclosing sexual abuse,Footnote55 with boys delaying as much as 20 years before even a partial disclosure.Footnote56 Given this dynamic, it is possible a child may deny sexual abuse during a forensic interview as a result of fear or threats, but may nonetheless disclose physical abuse, neglect, emotional abuse or witnessing interpersonal violence simply because they have never been threatened not to share these family secrets. For instance, we know from some studies that even when physical abuse is not the primary reason for the interview, children will often disclose when asked.Footnote57 If this is true, the government may nonetheless be able to take protective actions even without a disclosure of the sexual abuse. With services, the child may eventually also feel comfortable disclosing other forms of trauma.

Case law and the development of forensic interviewers as expert witnesses

Since its inception, ChildFirst/Finding Words has included a module on testifying in court and qualifying the forensic interviewer as an expert witness on both interviewing and various dynamics present in many cases of child abuse. The course was originally under the auspices of the National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse, and then the National Child Protection Training Center. Given this strong connection with child abuse prosecutors and child protection attorneys, it is not surprising that there has been a marked growth in courts accepting forensic interviewers as experts on a wide variety of subjects—with many of the appellate cases coming from states utilizing the ChildFirst model—including Connecticut, Kansas, Georgia, Minnesota, Mississippi, Ohio, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia.Footnote58

ChildFirst trainers have also been proactive in drafting law review articles and other scholarly articles that have been cited in trial and appellate briefs.Footnote59 These articles may also have influenced the acceptance of forensic interviewers as expert witnesses, and helped limit the scope of testimony permissible by defense experts, who seldom have worked in the field of interviewing but nonetheless often critique the forensic interview.

The influence of ChildFirst on the continued use of media in forensic interviews

There is widespread consensus among all the major forensic interviewing training programs as to what constitutes best practices in the field.Footnote60 All the courses recognize some value in using media, specifically anatomical diagrams and dolls.Footnote61 However, ChildFirst has been proactive in pointing out that most research supports the usage of anatomical dolls as a demonstration aid after a disclosure,Footnote62 and that the research on anatomical diagrams, though limited and flawed, nonetheless finds utility in these tools.Footnote63 Given this position, and the widespread usage of the ChildFirst model, it is not surprising that more than 90% of frontline interviewers continue to believe that diagrams are permissible for use in a forensic interview, and 69% believe it is permissible to use anatomical dolls in the forensic interview.Footnote64

ChildFirst and Child Sexual Abuse Materials

Although ChildFirst has been more supportive than some models of utilizing diagrams and dolls during a forensic interview, ChildFirst has also been more cautious than other models in showing a child images of themself that may have been collected during the investigation.Footnote65 ChildFirst has published guidelines stating the interviewers must take into account the readiness of a child to view images of abuse and the potential impact of viewing these images on the child’s formation of memories and ability to retrieve memories accurately.Footnote66

Child Advocacy Studies (CAST): the impact of Unto the Third Generation on undergraduate and graduate education of future MDT members

Although a significant body of literature documents the poor undergraduate and graduate training of future child protection professionals,Footnote67 academic institutions were slow to respond to the need for reform prior to the development of Child Advocacy Studies or CAST. CAST is a national program promoting specialized courses and certificate or minor programs on child maltreatment in scores of undergraduate and graduate schools across the country. The first CAST program was developed at Montclair State University in New Jersey in the 1990s, but the development of CAST as a national program dates from 2003, when the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention funded Winona State University in Minnesota to develop a national model curriculum on child maltreatment for undergraduate institutions.Footnote68 The CAST curriculum is based on an outline of three courses described in Unto the Third Generation.Footnote69

The three courses were then fleshed out by reviewing 563 peer reviewed articles to determine core concepts all mandated reporters or child protection professionals need to know.Footnote70 Using Unto the Third Generation and oral presentations based on it, the team at NCPTC (which included some of the authors) marketed CAST to colleges and universities across the country. Schools offering the three-course model provided students with a certificate in CAST and other universities expanded the curriculum to an 18 or 21 credit certificate. As of this writing, CAST has been implemented in 97 institutions of higher education in 28 states.Footnote71 Mississippi leads the nation in implementing this reform with 18 CAST programs and another 10 schools trained and working towards CAST implementation in that state alone.Footnote72 CAST programs were also developed at the national level with medical schools, law schools and seminaries implementing the reform.Footnote73

Several peer reviewed studies on CAST have been conducted with all of the research showing positive results. A survey of CAST graduates found that 80% of CAST graduates were working in a field related to the minor and that 100% of the graduates strongly agreed or agreed the program better prepared them to respond to child maltreatment.Footnote74 In a comparison study of the skills of CAST students with child protection workers already in the field, researchers found that CAST students were on par with the skills of seasoned workers in basic skills and exceeded the skills of these workers in responding to more complex child abuse scenarios.Footnote75

Children’s Advocacy Centers of Mississippi™ commissioned the most robust research on the CAST undergraduate programs which was conducted by the Children and Family Research Center at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and studied a number of CAST programs in Mississippi. At the conclusion of a two-year study in which they surveyed students at the beginning and end of CAST courses and comparison courses, the researchers concluded:

CAST students scored higher than non-CAST students in similar disciplines on a range of outcomes measuring knowledge and judgment in responding to child maltreatment.

CAST students who are pursuing CAST certificates or minors had substantially better knowledge and judgment than other CAST students.

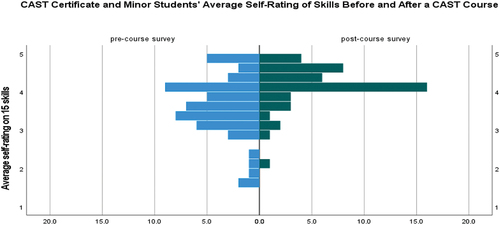

These advantages were present even at the beginning of the semester, so some of the CAST effect might be to attract and support students who already have more knowledge related to child maltreatment than their peers. CAST Certificate and Minor students showed the greatest improvement during their CAST courses. As the graphic below illustrates, CAST Certificate and Minor students’ average ratings of their child protection skills improved from the beginning to the end of their CAST course (using a measure in which they rated the truth of 15 affirmative statements about their skills, for example, “I know how to identify possible instances of child maltreatment”). The CAST certificate and minor students also demonstrated significantly better judgment at the end of the semester in recognizing child maltreatment, in response to two vignettes presenting them with hypothetical case facts.Footnote76

There have also been several studies on CAST graduate programs. CAST medical students are significantly better prepared to recognize signs of child maltreatment, to report suspected maltreatment, and to recommend or secure services than were students in a comparison group.Footnote77 CAST medical students are more likely to report suspicions of child maltreatment and to be accurate in identifying abuse than are medical students who did not receive CAST education.Footnote78 CAST medical students who received education on medical and mental health risks of corporal punishment had a significant decline in approval of hitting children as a means of discipline and this change in attitude was maintained at the end of the academic year.Footnote79 This is a significant finding because parents are more likely to seek and follow the advice of pediatricians on child discipline than any other professional.Footnote80

CAST and the growth of experiential education and problem-based learning

CAST places a heavy emphasis on experiential and problem-based learning where students practice their skills, often in mock houses, medical exam rooms, courtrooms, forensic interview rooms, or other facilities ideal for simulation training.Footnote81 These facilities have also been used for training of multi-disciplinary teams already in the field.Footnote82 CAST students participating in simulations have reported their “knowledge of core trauma concepts increased markedly, and their self-appraisal of their trauma-informed skills increased substantially.”Footnote83

Faith and Child Protection collaborations

In a review of 34 peer-reviewed studies involving more than 19,000 victims of child abuse, scholars noted that most of these studies found that child abuse impacted the faith of these victims, often by damaging the victim’s view of and relationship with God.Footnote84 This is particularly acute if the victim is abused by a member of the clergy.Footnote85 At the same time, spirituality can be a significant source of resilience for maltreated children and adult survivors.Footnote86

As noted by two scholars:

The research around religious and spiritual coping shows strong and convincing relationships between psychological adjustment and physical health following trauma. Spirituality provides a belief system and sense of divine connectedness that helps give meaning to the traumatic experience and has been shown over and over to aid in the recovery process.Footnote87

The team developing CAST nationally emphasized the importance of education of clergy, and used Unto the Third Generation to promote the creation of seminary courses. These training courses aim to foster effective working relationships between faith and child protection communities, and stimulate publication of secular and theological articles on child abuse,Footnote88 and the creation of chaplaincy programs in Children’s Advocacy Centers.Footnote89 In 2023, the United States Department of Justice, Office of Victims of Crime, awarded Zero Abuse Project a three year grant to expand access to spiritual care for child abuse victims and to research the efficacy of CAC chaplain initiatives.Footnote90

The impact of Unto the Third Generation on Prevention

As noted earlier, Unto the Third Generation didn’t offer a specific list of prevention proposals so much as a framework in which prevention initiatives could unfold.Footnote91 There is now peer-reviewed research showing the effectiveness of this approach. A study on the impact of CAST at a medical school found the program “increased significantly” the preparedness of students to “recommend or secure” prevention or other needed services for at risk children and concluded CAST could have a “profound impact on reducing child maltreatment.Footnote92

The first author expanded on Unto the Third Generation to publish proposed guidelines for working with parents who believe God requires physical discipline.Footnote93 These guidelines inspired two studies finding that a culturally humble approach to the subject can change attitudes about physical discipline among theologically conservative Protestants.Footnote94 This is important because theologically conservative Protestants are much more likely to support and use corporal punishment than other religious groups,Footnote95 and because corporal punishment is a significant contributing factor to child physical abuse.Footnote96 Although more research is needed, it is logical to assume a change in attitudes about hitting children may result in fewer children being struck and a corresponding decline in physical abuse.

Unto the Third Generation also influenced prevention policies. In 2007, the Centers for Disease Control published a guide for “Preventing Child Sexual Abuse Within Youth-serving Organizations.”Footnote97 The National Child Protection Training Center (now Zero Abuse Project), the organization which guided Unto the Third Generation reforms, disagreed with this narrow approach of focusing solely on sexual abuse within these organizations. Zero Abuse Project called on youth serving organizations not only to prevent sexual abuse within their institutions, but also to implement policies for preventing or otherwise addressing sexual abuse in the home as well as addressing physical abuse, emotional abuse, neglect and other forms of maltreatment.Footnote98 This influenced prevention policy reforms in the United States Olympics,Footnote99 the Boy Scouts of America,Footnote100 and in faith communities.Footnote101

Catalyst for a National Plan to End all Forms of Violence

Unto the Third Generation also influenced the National Plan to End Interpersonal Violence Across the Lifespan—a national plan endorsed by a “nonpartisan group of individuals, organizations, agencies, coalitions, and groups that embrace a national, multidisciplinary, and multicultural commitment to the prevention of all forms of interpersonal violence.”Footnote102 The plan issues 22 specific recommendations, including developing a competent workforce, strengthening the healthcare and mental healthcare responses to violence, strengthening justice system responses, connecting research to practice, and improving public awareness and policy.Footnote103 Many of these recommendations were rooted in Unto the Third Generation but updated and expanded to address all forms of violence across the lifespan.

Needed additions to the plan to end child abuse

Added knowledge and experience since the publication of Unto the Third Generation indicates several necessary additions to the plan to end child abuse.

Racial disparities

Although Unto the Third Generation emphasized cultural sensitivity and diversity, the article did not specifically address racial disproportionalityFootnote104 and disparityFootnote105 in our responses to child maltreatment. Going forward, every member of the multi-disciplinary team must be proactive in making sure our civil and criminal justice responses to maltreatment are truly just for all families and children. There is some evidence CAST may be one tool in reducing racial and other disparities in the child protection system. Research found that students in CAST certificate and minor programs improved more than comparison students in recognizing the difference between poverty and neglect and being sensitive to different parenting approaches of diverse communities and cultures.Footnote106

LGBTQIA2S+

Unto the Third Generation affirms that a culturally informed approach to child abuse victims and their families is established best practice. Dynamics around sexual orientation, gender identity and expression (SOGIE) can affect many aspects of a victim’s abuse experience, disclosure process and desired support. Youth who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual and/or two spirit (LGBTQIA2S+), and have been abused, live at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities. As a result, they often experience compounded stress and negative effects on their health and wellbeing.Footnote107 Additionally, LGBTQIA2S+ youth experience increased rates of harassment, rejection, bias, discrimination, and lack of support, in addition to the traditionally acknowledged or statutorily recognized forms of abuse and maltreatment.Footnote108

Emotional abuse/maltreatment: LGBTQIA2S+ children and youth can experience many forms of identity-related emotional maltreatment which include identity denial, family rejection and abandonment, negative and disparaging comments, tactical isolation, intentional use of deadnames or incorrect pronouns and the threat of being outed.Footnote109 Transgender and non-binary youth are eight times more likely to attempt suicide than their cisgender counterparts.Footnote110

Physical abuse/maltreatment: LGBTQIA2S+ children and youth may experience physical violence as a reaction to their SOGIE The physical harm can range from the withholding of medicine or medical care to murder.

Sexual abuse/maltreatment: LGBTQIA2S+ children and youth can be subjected to “corrective” sexual assault or abuse in an attempt to “turn” the youth heterosexual and/or cisgender and/or “punish” the youth for their SOGIE. Eleven percent of LGBT youth report that they have been sexually attacked or raped because of their actual or assumed LGBT identity.Footnote111

Neglect: LGBTQIA2S+ children and youth face homelessness, out-of-home placement, and parental abandonment at disproportionately higher rates. More than half of LGBTQIA2S+ runaways reported running away due to fear or mistreatment related to their LGBTQIA2S+ identity.Footnote112

Hate Crimes: LGBTQIA2S+ people can be the targets of violent crime simply because of their status or perceived status as an LGBTQIA2S+ person. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, 16.8% of hate crimes resulted from sexual orientation bias, 2.8% were motivated by gender-identity bias, and approximately 1% were motivated by gender bias.Footnote113

Male Victims

Although Unto the Third Generation created a framework to address the sexual abuse of boys, the article did not specifically address the unique dynamics of the victimization of males. A study of 487 adult male survivors of child sexual abuse found that, on average these victims delayed a partial disclosure for 21 years and delayed a full disclosure of the abuse for an average of 28.23 years.Footnote114 We also know the factors that result in these significant delays: concerns about masculinity, mistrust of others, fear of being labeled “gay” or other concerns about sexual orientation/identity, and unique factors when a boy is abused by a member of the clergy.Footnote115 It is critical that, going forward, all professionals become acquainted with these unique dynamics and take them into account when working with male victims of maltreatment.Footnote116

Technology

Since the publication of Unto the Third Generation, the role of technology in society has grown exponentially. This has led to a correspondingly exponential increase in the use of technology to perpetrate child abuse, but also provided child abuse prosecutors and investigators with significant additional sources of corroborating evidence. Digital evidence now plays a role in almost every criminal case, including child abuse cases.Footnote117 The U.S. Supreme Court has described mobile devices as “almost a ‘feature of human anatomy,’” and this phenomenon is not limited to adults.Footnote118 Given the central role that technology in general (and smart phones in particular) play in the lives of both children and offenders, it is now critical for all child protection professionals to understand and leverage modern technology in the context of both child abuse preventionFootnote119 and response.

In an investigative context, phones can establish locations and proximity of witnesses via cell site location information or various applications that track and store location data, such as Google Dashboard. WiFi routers also have the ability to place suspects “at a scene, at a particular time.”Footnote120 Mobile devices are often a source of incriminating or insightful communications, videos, and photos. The use of livestreaming applications in the context of sexual exploitation accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote121 Use of social media is also common, including by young children.Footnote122 Investigators should be alert for the child’s online gaming activities and whether evidence of grooming may be present on these platforms.Footnote123

Importantly, digital evidence is increasingly stored remotely on servers across state lines and around the globe, so it is critical for investigators to send an immediate letter of preservation to relevant internet service providers to avoid destruction of evidence through remote wiping or routine data deletion processes of the provider.Footnote124 Investigators should use subpoenas to develop probable cause. For example, if a detective sends a subpoena to Google with a suspect’s Gmail address, it should result in a subpoena return listing all related Google products, some of which (Google Photos, Google Drive, Google Dashboard, etc.) may be useful to articulate probable cause.Footnote125 When in doubt, investigators and prosecutors should use search warrants to acquire content-based information.Footnote126

Child protection professionals must consider integration of promising new technologiesFootnote127 into efforts in both prevention and detection of child exploitation, including widespread distribution of child sexual abuse material. Unto the Third Generation’s insight that the child protection community lacks a unified voice applies as well in the context of technology, with devastating consequences. This is tragically illustrated by Apple’s decision to abandon a child sexual abuse material scanning mechanism that likely would have detected almost 1,500 reports a day, a decision made possible by the relative strength, unity, and resources of privacy advocates compared to the child protection community.Footnote128

Although Unto the Third Generation did not focus on technology, its principles and blueprint directly inspired and informed the creation and delivery of multiple courses equipping prosecutors to utilize digital evidence in child exploitation and other felony cases. These include three of the four most prolific national courses, such as the STARK (Stopping Technology-Facilitated Abuse of Rural Kids) Prosecutor Symposium. Unto the Third Generation also inspired innovative publicationsFootnote129 and software developmentFootnote130 to equip child abuse investigators and prosecutors on the frontlines of technology-facilitated child abuse.

Corporal punishment and the Risk of Physical Abuse

In July 2016, the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children (APSAC) adopted a position statement that “opposes hitting children for discipline or other purposes.”Footnote131 This position is supported by a large body of research finding that corporal punishment in the home elevates the risks for poor child outcomes including depression, anxiety, use of drugs and alcohol, psychiatric disorders, aggression, antisocial behavior, and poorer parental child relationships.Footnote132

Although there are fewer studies on the effect of school corporal punishment, students who have “experienced corporal punishment are more likely to have poorer peer relationships, more difficulty concentrating, lower academic achievement, and more somatic complaints and resentment of authority, and are more likely to avoid and drop out of school.”Footnote133

Although Unto the Third Generation did reference corporal punishment and, as noted earlier, contributed to a number of initiatives to address physical discipline on the basis of religion, the paper did not directly address the contribution of corporal punishment to substantiated cases of physical abuse. It is now increasingly clear that we cannot achieve a significant reduction of child physical abuse unless we are prepared to draw a line in the sand and say a child should not be physically struck by teachers, parents or other caregivers.

Preventing Sexual Abuse by Identifying and Working with Adolescents with Problematic Sexual Thoughts

It is during adolescence that individuals typically become aware of a sexual attraction to prepubescent children,Footnote134 although this is often “a slow process of awareness, starting with early indications that the objects of their attractions were different from their peers.”Footnote135 A sexual attraction to children is often not a temporary phase but a lifelong thought pattern.Footnote136 If this is true, and we could create an environment where these young persons could speak about their concerning thoughts, it might be possible to manage these thoughts and stop them from becoming actions—and thereby prevent a great many cases of child sexual abuse.

SAMSHA Standards for Trauma-informed care

SAMSHA has developed standards for trauma-informed care.Footnote137 This should now be the base by which every mandated reporter, every child protection professional, every clergy,Footnote138 and every professional who in any way works with children must measure their effectiveness. SAMSHA’s six principles of trauma informed care are: safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; historical, cultural, and gender considerations. From these six principles, SAMSHA offers the following definition of a trauma-informed institution:

A program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; recognizes signs and symptoms in clients, families, staff, and others involved with systems; responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization.Footnote139

Unto the Third Generation And the decline in child maltreatment

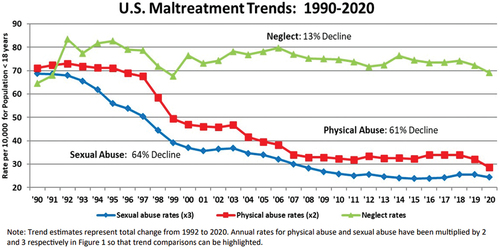

A number of data sets show a decline in child abuse and neglect over the past 30 years, with the steepest declines beginning to manifest itself in the mid-1990s. Here is a graph compiled by David Finkelhor, Kei Sata and Lisa Jones of the Crimes Against Children Research Center:Footnote140

Although there is currently no consensus on why child abuse, particularly sexual and physical abuse, has declined significantly, some scholars note the “period when sexual and physical abuse started the dramatic downward trend was marked by sustained economic improvement, increases in the numbers of law enforcment and child protection personnel, more aggressive prosecution and incarceration policies, growing public awareness about the problems, and the dissemination of new treatment options for family and mental health problems, including new psychiatric medication.”Footnote141

Although not all child protection professionals believe the decline in abuse is real, more than half of child protection administrators from 43 states “mentioned the effectiveness of prevention programs, increased prosecution, and public awareness campaigns, implying that a portion of the deline may result from a real decline in occurrence.”Footnote142

If “increased prosecution” played a role in the decline of child abuse, the training programs contemplated in Unto the Third Generation, nearly all of which involved improving the investigation and prosecution of these cases would have had an impact nationally. Unto the Third Generation strrongly emphasized the need for an improved criminal justice responseFootnote143 and specifically noted the potential role of prosecution in preventing abuse, by removing repeat offenders from the community and also deterring others from committing these crime altogether.Footnote144

If community awareness and prevention initiatives played a role, then the work of policy development and engagement with faith communities and the instruction on prevention that is part of Child Advocacy Studies would have played a role on this front as well. Most importantly, the work of improving the education of all mandated reporters and child protection professionals who regularly intersect with the lives of maltreated children would also have had an impact and this conclusion is supported by research.Footnote145 If the research from Cross and others on CAST is accurate, then the undergraduate and graduate reforms which were at the heart of Unto the Third Generation is graduating future child protection professionals who are better equipped to recognize and respond to abuse, to prevent abuse, and to be culturally humble.

Conclusion

In proposing a three-generation plan of action, Unto the Third Generation worried that our “quick-fix, fast-food nation” may “never dedicate itself to a long-term battle against child abuse, a battle that may extend to the next century.”Footnote146 In order to contemplate the ultimate victory, Unto the Third Generation recounted the battle at Gettysburg and the charge of 262 Minnesotans into a field of 1,600 advancing confederates in the hope of buying a few minutes of time and enabling the union to gain reinforcements. Believing in the cause they were about to give their lives for, and believing in those who would come after them, the Minnesotans made the ultimate sacrifice.

Since its publication, Unto the Third Generation has inspired frontline child protection professionals around the country, even the world, to take concrete actions, not only to better the lives of children today, but also to lay the foundation for ending child abuse, or at least contributing to its decline.

In response to a university lecture on Unto the Third Generation, a college student asked the first author if she was in the first or second generation of the plan. Vieth explained that, given her age, she would see much of the plan put into place. But, he continued, she would also have to be one of many who educates the next generation to build on these successes, and to develop their own forty-year plan. The student responded enthusiastically, calling herself one of the “keepers of the plan.”

Equally important, Unto the Third Generation has influenced not only individual child protection professionals but also systems. Perhaps the best example of this is the Children’s Advocacy Centers of Mississippi™ which has not only implemented a state forensic interview training program but has advanced CAST at a level greater than any other state.

If the enthusiasm of child protection professionals and child protection systems hold steady for a lifetime, then the best is yet to come. As stated in the original paper, “If we act now and for the rest of our lives as a testament to the invisible attributes of faith, hope and love, a later generation may one day see with their eyes what our hearts tell us is our nation’s destiny.”

Child abuse will end.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass, Prophet of Freedom (2018).

2 David Chadwick (physician), Wikipedia available online at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Chadwick_(physician).

3 See The National Call To Action: A Movement to End Child Abuse and Neglect https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/holton.pdf; Sadler, B. L., Chadwick, D. L., & Hensler, D. J. The Summary Chapter-The National Call to Action: Moving Ahead, 23 CHILD ABUSE & NEGLECT, 1011, 1018 (199)

4 Tanya S. Hinda & Angelo P. Giardino, Child Physical Abuse: Current Evidence, Clinical Practice, and Policy Directions 114, 116 (2017).This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

5 David L. Chadwick, The Message, in Convening a National Call to Action: Working Toward the Elimination of Child Maltreatment, 23 Child Abuse & Neglect 987, 993 (1999).

6 Anne Cohn Donnelly, The Practice, in Convening a National Call to Action: Working Toward the Elimination of Child Maltreatment, 23 Child Abuse & Neglect 987, 993 (1999).

7 Id.

8 The paper was written in 2005 but its publication date is 2006. Victor Vieth, Unto the Third Generation: A Call to End Child Abuse in the United States within 120 years, 12 Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 5 (2006).

9 Victor Vieth, Unto the Third Generation: A Call to End Child Abuse in the United States within 120 years (Revised and Expanded), 28(1) Hamline Journal of Public Law & Policy 1 (2006)

10 Jon M. Garon, For the Benefit of the Infant: An Introduction to the Symposium to End Child Abuse, 28(1) Hamline Journal of Public Law & Policy i, vi (2006) (noting the issue in which Unto the Third Generation was published “set a Hamline record” for the “size of its initial publication.”)

11 The plan was also presented as part of a symposium in St. Paul Minnesota which led to the article’s publication as well as the publication of other articles to advance the cause of protecting children from abuse. Jon M. Garon, For the Benefit of the Infant: An Introduction to the Symposium to End Child Abuse, 28(1) Hamline Journal of Public Law & Policy i-vi (2006)

12 David L. Chadwick, Ending Child Abuse, 12 Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 159 (2006).

13 Id.

14 Vieth, note 9 at 9-11.

15 Victor I. Vieth, Mark D. Everson, Robert Geffner, Anna Salter, Cordelia Anderson, Alan B. Kirk, Millicent J. Carvalho-Grevious, Lisa B. Johnson, G. Anne Bogat, Harold A. Johnson, Betsy Goulet, Debra J. Baird, Jennifer S. Parker, Judith A. Ramaley, Rebecca Peneitz, Jason P. Kutulakis, Basyle J. Tchividjian, John D. Schuetze, Pearl Berman, Maureen McHugh, Barbara Stein-Stover, Susan D. Samuel, Esther L. Devall, Anthony D’Urso, Helen Cahalane, Michele Knox, Jacquelyn W. White, Lessons from Penn State: A Call to Implement a New Pattern of Training for Mandated Reporters and Child Protection Professionals, 3(3) CenterPiece 1-9 (2012).

16 Victim 1, Usa Today at 1A, 2A, November 11, 2011.

17 Mandated Reporter Survey Report, The Protect our Children Committee 1 (2011).

18 Id.

19 Id. at 2. Although Unto the Third Generation is rooted in the belief that mandated reporting is a good thing which protects many children from ongoing abuse or death, this belief is not universally shared. There is an ongoing debate about mandated reporting and whether or not any, much less all human beings have a moral obligation to report suspected abuse. See e.g. Rebecca Brashler, et al, Time to Make a Call? The Ethics of Mandatory Reporting, 8(1) PM&R 69-74 (2016); Ben Matthews & Donald C. Bross, Mandated Reporting is Still a Policy with Reason: Empirical evidence and Philosophical Grounds, Child Abuse & Neglect 511-516 (2008).

20 Vieth, note 9 at 12 citing Andrea J. Sedlak & Diane D. Broadhurst, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Third National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect 7-16 (1996).

21 Barbara L. Knox, et al, Child Torture as a Form of Discipline, 7 Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 37 (2014).

22 Vieth, note 9 at 13.

23 Victh, note 9 at 13-16.

24 Kelly M. Champion, Kimberly Shipman, Barbara L. Bonner, Lisa Hensley, and Allison C. Howe, Child Maltreatment Training in Doctoral Programs in Clinical, Counseling, and School Psychology: Where Do We Go From Here?, 8 Child Maltreatment 211, 215 (August 2003); M. Anne Woodtli & Eileen T. Breslin, Violence-Related Content in the Nursing Curriculum: A Follow-Up National Survey, 41 Journal of Nursing Education 340 (2002); Elaine J. Alpert, Robert D. Sege, & Ylisabyth S. Bradshaw, Interpersonal Violence and the Education of Physicians, 72 Academic Medicine s41-S50 (1997). JR Hill, Teaching about Family Violence: A proposed Model Curriculum., 17(2) Teaching and Learning in Medicine 169-178 (2005); Michele Knox, Heather Pelletier, & Victor Vieth, Educating Medical Students About Adolescent Maltreatment, International Journal of Adolescent Medicine (2014); Michele S. Knox, Victor Vieth and Heather Pelletier, Effects of Medical Student Training in Child Advocacy and Child Abuse Prevention and Intervention, Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice & Policy (2014).

25 Vieth, note 9 at 16.

26 David L. Corwin and Victor Vieth, Resources to Advance ACEs Knowledge and Paradigm Shift. 10 Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma 299–300 (2017).

27 Melissa A. Polusny & Victoria M. Follette. Long-term correlates of child sexual abuse: Theory and review of the empirical literature. 4, APPLIED AND PREVENTIVE PSYCHOLOGY, 143-166. Rosana E. Norman, Munkhtsetseg Byambaa, Rumna De, Alexander Butchart, James Scott & Theo Vos, The Long-Term Health Consequences of Child Physical Abuse, Emotional Abuse, and Neglect: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. 9, PLOS MEDICINE, e1001349 (2012). Vincent Felitti & Robert F. Anda, The Relationship of Adverse Childhood Experiences to Adult Medical Disease, Psychiatric Disorders and Sexual Behavior: Implications for Healthcare, in Ruthe A. Lanius, eric Vermeten & Clare Pain (EDS) The Impact of Early Life Trauma on Health and Disease: The Hidden Epidemic 77 (Cambridge Medicine 2010).

28 Vieth note 9 at 17.

29 Vieth note 9 at 19-20.

30 Vieth, note 9 at 33-37

31 Vieth, note 9 at 37-41.

32 Vieth, note 9 at 21-29

33 Vieth, note 9 at 29-31.

34 Vieth, note 9 at 33-34.

35 Vieth, note 9 at 45.

36 Vieth, note 9 at 45.

37 Vieth, note 9 at 46.

38 Vieth, note 9 at 53-57.

39 Vieth, note 9 at 48-53.

40 Vieth, note 9 at 48-49

41 Vieth, note 9 at 50, See generally, Jon Meacham, His Truth is Marching On: John Lewis and the Power of Hope (2020). See also, Lewis V. Baldwin, The Voice of Conscience: The Church in the Mind of Martin Luther King, Jr, (2010)(“By skillfully combining biblical piety and theological liberalism with social analysis and nonviolence activism, King stimulated the thinking and penetrated the lives of millions exposing their mediocrities and energizing them with a new and more vital sense of what Dietrich Bonhoeffer termed ‘the cost of discipleship.’ This is why the civil rights leader’s name is routinely included among Christianity’s most celebrated saints and sages.”)

42 Vieth, note 9 at 61-74.

43 Tanya S. Hinda & Angelo P. Giardino, Child Physical Abuse: Current Evidence, Clinical Practice, and Policy Directions 114, 117 (2017).

44 Monica L. McCoy & Stefanie M. Keen, Child Abuse & Neglect Second Edition 53-54 (2014).

45 Morgan Dynes, Michele Knox, Kimberly Hunter, Yazhini Srivathsal & Isabella Caldwell Impact of education about physical punishment of children on the attitudes of future physicians, 49(2) Children’s Health Care, 218-231 (2020); Thomas L. Haffmeister, Castles Made of Sand? Rediscovering Child Abuse & Society’s Response, 36 Ohio Northern University Law Review 819, 824 (2010); Eric S. Janus and Emily A. Polachek. A crooked picture: Re-framing the problem of child sexual abuse, 36 Wm. Mitchell L. Rev. 142 (2009); Theodore P. Cross and Yu-Ling Chiu, Mississippi’s experience implementing a statewide Child Advocacy Studies Training (CAST) initiative, 18 Journal of Family Trauma, Child Custody & Child Development 299-318 (2021); Jack C. Westman, Barriers to Change and Hope for the Future in Jack C. Westman, Dealing with Child Abuse and Neglect as Public Health Problems 177-187 (2019).

46 Rita Farrell and Victor Vieth, ChildFirst® forensic interview training program, 32(2) APSAC Advisor 56-63 (2020).

47 Robin Delany-Shabazz, Victor Vieth. The National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2001.

48 Kathleeen Coulborn Faller, Forty Years of Forensic Interviewing of Children Suspected of Sexual Abuse, 1974-2014: Historical Benchmarks, 4 Social Sciences 34, 49 (2015).

49 Farrell and Vieth, note 46 at 57.

50 Farrell and Vieth, note 46 at 57 (2020).

51 Chris Newlin, Linda Cordisco Steele, Anda Chamberlin, Jennifer Anderson, Julie Kenniston, Amy Russell, Heather Stewart, and Viola Vaughan-Eden, Child Forensic Interviewing: Best Practices, Ojjdp Juvenile Justice Bulletin (September 2015).

52 Farrell & Vieth, note 46, at 58

53 Heather A. Turner, David Finkelhor, and Richard Ormrod, Poly-Victimization in a National Sample of Children and Youth, 38(3) American Journal of Preventive Medicine 323 (2010), David Finkelhor, Richard K. Omrod, Heather A. Turner, Poly-victimization: A Neglected Component in Child Victimization, 31 Journal of Child Abuse & Neglect 7 (2007).

54 Id.

55 Chris Newlin, Linda Cordisco Steele, Andra Chamberlin, Jennifer Anderson, Julie Kenniston, Amy Russell, Heather Steward, Viola Vaughan Eden, Child Forensic Interviewing: Best Practices, Ojjdp Juvenile Justice Bulletin 5 (September 2015).

56 Victor I. Vieth, Rita Farrell, Rachel Johnson, Tomiko Mackey, Caitie Dahl, Kathleen Nolan, Robert J. Peters, & Tyler Counsil, Where the Boys Are: Investigating and Prosecuting Cases of Child Sexual Abuse When the Victim is Male, Zero Abuse Project (2020).

57 Katherine McGuire & Kamala London, A retrospective approach to examining child abuse disclosure, Child Abuse & Neglect (2019), PMID: 31734635; https://10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104263

58 Victor I. Vieth, The Forensic Interviewer at Trial: Guidelines for the Admission and Scope of Expert Testimony Concerning a Forensic Interview in a Case of Child Abuse (Revised and Expanded), 47 Mitchell Hamline Law Review 865-881 (2021).

59 See e.g. Victor I. Vieth, The Forensic Interviewer at Trial: Guidelines for the Admission and Scope of Expert Testimony Concerning a Forensic Interview in a Case of Child Abuse (Revised and Expanded), 47 Mitchell Hamline Law Review 865-881 (2021); Victor I. Vieth, Anatomical Diagrams and Dolls: Guidelines for Their Usage in Forensic Interviews and Courts of Law, 48(1) Mitchell Hamline Law Review 83 (2022); Rita Farrell and Victor Vieth, ChildFirst® Forensic Interview Training Programs, 32(2) Apsac Advisor 56, 59 (2020); Chris Newlin, Linda Cordisco Steele, Anda Chamberlin, Jennifer Anderson, Julie Kenniston, Amy Russell, Heather Stewart, and Viola Vaughan-Eden, Child Forensic Interviewing: Best Practices, Ojjdp Juvenile Justice Bulletin 8 (September 2015); Amy Russell, Best Practices in Child Forensic Interviews: Interview Instructions and Truth-Lie Discussions, 28 Hamline Journal of Public Law & Policy 99 (2006).

60 Chris Newlin, Linda Cordisco Steele, Anda Chamberlin, Jennifer Anderson, Julie Kenniston, Amy Russell, Heather, Stewart, and Viola Vaughan-Eden, Child Forensic Interviewing: Best Practices, Ojjdp Juvenile Justice Bulletin (September 2015).

61 Vieth, note 58 at 88-94.

62 Kathleen Coulborn Faller, Interviewing Children about Sexual Abuse: Controversies and Best Practice 115 (OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 2007); Kathleen Coulborn Faller, Anatomical Dolls: Their Use in Assessment of Children Who May Have been Sexually Abused, 14(3) Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 1, 9 (2005).

63 Victor Vieth, Anatomical Diagrams and Dolls: Guidelines for the Their Usage in Forensic Interviews and Courts of Law 48 Mitchell Hamline Law Review 83 (2022).

64 Allison Foster, Licensed Clinical Psychologist, Metropolitan Children’s Advocacy Center, Presentation at Zero Abuse Project 2020 Summit: Contemporary Use of Human Figure Drawings and Dolls: Where Do We Go from Here? (Feb. 26-28 2020).

65 See Martha Finnegan, Investigative Interviews of Adolescent Victims. Washington, D.C.: Federal Bureau of Investigation, Office for Victim Assistance (2005); National Children’s Advocacy Center, Position paper on the introduction of evidence in forensic interviews of children (2013).

66 Pete Singer & Rita Farrell, The Use of Images During Forensic Interviews of Children who Have Been Sexually Abused, Zero Abuse Project (2023). See also Netanel Germara, Noa Cohen, and Carmit Katz, “I do not remember … You are reminding me now!”: Children’s difficult experiences during forensic interviews about online sexual solicitation, 134 Child Abuse & Neglect 105913 (2022).

67 Victor I. Vieth, Betsy Goulet, Michele Knox, Jennifer Parker, Lisa B. Johnson, Child Advocacy Studies (CAST): A National Movement to Improve the Undergraduate and Graduate Training of Child Protection Professionals, 45(4) Mitchell Hamline L. Rev. 1129, 1132-1137 (2019).

68 Id.

69 Vieth, note 9 at 33-36.

70 Victor I. Vieth, Betsy Goulet, Michele Knox, Jennifer Parker, Lisa B. Johnson, Karla Steckler Tye, Theodore P. Cross Child Advocacy Studies (CAST): A National Movement to Improve the Undergraduate and Graduate Training of Child Protection Professionals, 45(4) Mitchell Hamline L. Rev. 1129, 1140 (2019).

71 See CAST portion of Zero Abuse Project website for complete listing of CAST courses: https://www.zeroabuseproject.org/for-professionals/child-advocacy-studies/

72 Theodore P. Cross & Yu-Ling Chiu Mississippi’s experience implementing a statewide Child Advocacy Studies Training (CAST) Initiative, 18(4) Journal of Family trauma, Child Custody & Child Development 299, 318 (2021)

73 Vieth, note 67, at 1142-1146.

74 Aurea K. Osgood, Lessons Learned from Student Surveys in a Child Advocacy Studies (CAST) Program, 10 Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 261-265 (2017).

75 Jennifer Parker, Lynn McMillan, Stacy Olson, Susan Ruppel, Victor Vieth, Responding to Basic and Complex Cases of Child Abuse: A Comparison Study of Recent and Current Child Advocacy Studies (CAST) Students with DSS Workers in the Field, 13 Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 357-364 (2020).

76 Theodore P. Cross & Yu-Ling Chiu, Final Report: Program Evaluation of Mississippi’s CAST Initiative. Urbana, IL: Children and Family Research Center, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (2021).

77 Michele Knox, Heather Pelletier, Victor Vieth, Educating Medical Students about Adolescent Maltreatment, 25(3) International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health 301-308 (2013).

78 Heather L. Pelletier and Michele Knox, Incorporating Child Maltreatment Training into Medical School Curricula, 10(3) Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 267-274 (2017).

79 Morgan Dynes, Michele Knox, Kimberly Hunter, Yazhini Srivathsal & Isabella Caldwell (2020) Impact of education about physical punishment of children on the attitudes of future physicians, Children’s Health Care, 49:2, 218-231, https://10.1080/02739615.2019.1678472

80 Catherine A. Taylor, William Moeller, Lauren Hamvas, and Janet Rice, Parents’ Professional Sources of Advice Regarding Child Discipline and their Use of Corporal Punishment, 52(2) Clinical Pediatrics 147-155 (2012).

81 Vieth, note 67 at 1151-1154, 1157-1159.

82 Id.

83 Theodore P. Cross and Yu-Ling Chiu, Final Report: Program Evaluation of Mississippi’s CAST Initiative, August 2021, p. ii.

84 Donald F. Walker, et al, Changes in Personal Religion/Spirituality During and After Childhood Abuse: A Review and Synthesis, 1 Psychology & Trauma: Theory, Practice & Policy 130 (2009); See also, Amy Russell, The Spiritual Impact of Child Abuse & Exploitation: What the Research Tells Us, 45 Currents in Theology & Mission 14 (2018); Victor I. Vieth, Wounded Souls: The Need for Child Protection Professionals and Faith Leaders to Recognize and Respond to the Spiritual Impact of Child Abuse, 45(4) Mitchell Hamline Law Review 1213-1234 (2019).

85 Noemi Pereda, Lorena Contreras Taibo, Anna Segura and Francisco Maffioletti, An Exploratory Study on Mental Health, Social Problems and Spiritual Damage in Victims of Child Sexual Abuse by Catholic Clergy and Other Perpetrators, 31(4) Journal of Child Sexual abuse 393-411 (2022).

86 Thema Bryant-Davis, Monica U. Ellis, Elizabeth Burke-Maynard, Nathan Moon, Pamela A. Counts, and Gera Anderson, Religiosity, Spirituality, and Trauma Recovery in the Lives of Children and Adolescents, 43 Professional Psychology: Research and Review 306 (2012); Katie G. Reinhert, Jacquelyn C. Campbell, Karen Beneen-Roche, Jerry W. Less, and Sarah Szanton, The Role of Religious Involvement in the Relationship Between Early Trauma and Health Outcomes Among Adult Survivors, 9 Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 231 (2016); Jungmeen Kim, The Protective Effects of Religiosity on Maladjustment Among Maltreated and Nonmaltreated Children, 32 Child Abuse & neglect 711 (2008); Terry Lynn Gall, Spirituality and Coping with Life Stress Among Adult Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse, 30 Child Abuse & Neglect 829 (2006); Thema Bryant Davis & Eunice C. Wong, Faith to Move Mountains: Religious Coping, Spirituality, and Interpersonal Trauma Recovery, American Psychologist 675 (November 2013).

87 Casey Gwinn & Chan Hellman, Hope Rising 180 (2019).

88 See generally, Victor Vieth & Pete Singer, Wounded Souls: The Need for Child Protection Professionals and Faith Leaders to Recognize and Respond to the Spiritual Impact of Child Abuse, 45(4) Mitchell Hamline Law Review 1213 (2019).

89 Victor I. Vieth, Mark D. Everson, Viola Vaughan-Eden, Suzanna Tiapula, Shauna Galloway-Williams, Carrie Nettles, Keeping Faith: The Potential Role of a Chaplain to Address the Spiritual Needs of Maltreated Children and Advise Child Abuse Multi-Discplinary Teams, 14(2) Liberty University Law Review 351 (2020).

91 Notes 35 to 41 and accompanying text.

92 Michele S. Knox, Heather Pelletier, & Victor Vieth, Effects of Medical Student Training in Child Advocacy and Child Abuse Prevention and Intervention, 6(2) Psychological Trauma: theory, Research, Practice & Policy 129, 132 (2014).

93 Victor I. Vieth, From Sticks to Flowers: Guidelines for Child Protection Professionals Working with Parents Using Scripture to Justify Corporal Punishment, 40 William Mitchell Law Review 907 (2014); Victor I. Vieth, Working with Molly: A Culturally Sensitive Approach to Parents Using Corporal Punishment Because of Their Religious Beliefs, 31(1) APSAC Advisor 52-58 (2019).

94 Robin Perrin, et al, Changing Attitudes about Spanking Using Alternative Biblical Interpretations, 41 International Journal of Behavioral Development 514-22 (2017); Cindy Miller-Perrin and Robin Perrin, Changing Attitudes about Spanking Among Conservative Christians Using Interventions that Focus on Empirical Research Evidence and Progressive Biblical Interpretations, 71 Child Abuse & Neglect 69-79 (2017).

95 John. P. Hoffman, Christopher G. Ellison, & John P. Bartkowski, Conservative Protestantism and Attitudes Toward Corporal Punishment, 186-2014, 63 Soc. Science Research 81 (2017); Victor I. Vieth, From Sticks to Flowers: Guidelines for Child Protection Professionals Working with Parents Using Scripture to Justify Corporal Punishment, 40 Wm. Mitchell L. Rev. 907, 916-930 (2014).

96 Gershoff, E.T., 2002. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological bulletin, 128(4), p.539.

97 Saul J. Audage, Preventing Child Sexual Abuse Within Youth-serving Organizations: Getting Started on Policies and Procedures (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2007).

98 Gundersen National Child Protection Training Center, When the Athlete is a Child: an assessment of USA Swimming’s Safe Sport Program, January 27, 2014.

99 Id.

100 See Boy scouts of America, How to Protect your Children from Child Abuse: A Parent’s Guide. This guide offered “special thanks” to the National Child Protection Training Center (now Zero Abuse Project) for “invaluable assistance” in developing a guide that sought to prevent all forms of abuse and not simply sexual abuse within the organization.

101 Basyle Tchividjian & Shira M. Berkovits, The Child Safeguarding Policy Guide for Churches and Ministries (2017).

102 Victor I. Vieth & Pearl S. Berman, A National Plan to Interpersonal Violence Across the Lifespan, in Robert Geffner, Jacquelyn W. White, L. Kevin Hamberger, Alan Rosenbaum, Viola Vaughan-Eden, & Victor I. Vieth, EDs, Handbook of Interpersonal Violence Across the Lifespan 250 (2022).

103 Id, 249-273.

104 Disproportionality is the overrepresentation or underrepresentation of a racial or ethnic group compared with its percentage in the total population. Child Welfare Practice to Address Racial Disproportionality and Disparity, Children’s Bureau, United States Department of Health & Human Services 2 (2021).

105 Disparity is the unequal outcomes of one racial or ethnic group compared with outcomes for another racial or ethnic group. Child Welfare Practice to Address Racial Disproportionality and Disparity, Children’s Bureau, United States Department of Health & Human Services 2 (2021).

106 Theodore P. Cross & Yu-Ling Chiu, Final Report: Program Evaluation of Mississippi’s CAST Initiative. Children and Family Research Center, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (2021).

107 Miranda, Liam, et al. “2018 LGBTQ Youth Report.” Human Rights Campaign, 2018, http://www.hrc.org/resources/2018-lgbtq-youth-report.

108 Rachel Johnson et al, LGBTQIA2S+ Children and Families in the Forensic Interview and Multidisciplinary Response to Child Abuse.” Zero Abuse Project (2024). In press. A special thank you to Caitie Dahl, Forensic Interview Specialist at Zero Abuse Project, for contributing research and writing instrumental to the LGBTQIA2S+ section of Unto the Third Generation Revisited and co-authoring the cited article.

109 Michaela Rogers, Transphobic ‘Honour’-Based Abuse: A Conceptual Tool, 51 Sociology, 225–240 (2017).

110 Redefining Residential: Ensuring Competent Residential Interventions for Youth with Diverse Gender and Sexual Identities and Expressions https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0886571X.2016.1205316

111 Liam Miranda, et al. 2018 LGBTQ Youth Report, Human Rights Campaign (2018), http://www.hrc.org/resources/2018-lgbtq-youth-report.

112 Jonah DeChants, et al. Homelessness and Housing Instability Amongst LGBTQ Youth, The Trevor Project (2021), http://www.thetrevorproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Trevor-Project-Homelessness-Report.pdf.

113 “2019 Hate Crime Statistics.” Federal Bureau of Investigation, Federal Bureau of Investigation, 29 Oct. 2019, ucr.fbi.gov/hate-crime/2019/topic-pages/incidents-and-offenses.

114 Scott D. Easton, Disclosure of Child Sexual Abuse Among Male Survivors, 41 Clinical Social Work Journal 344-355 (2013).

115 Id.

116 Victor I. Vieth, Rita Farrell, Rachel Johnson, Tomiko Mackey, Caitie Dahl, Kathleen Nolan, Robert J. Peters, and Tyler Counsil, Where the Boys Are: Investigating and Prosecuting Cases of Child Sexual Abuse When the Victim is a Male, Zero Abuse Project (2022), available online at: https://www.zeroabuseproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/WhereTheBoysAre_508.pdf (last visited January 6, 2023.

117 Robert J. Peters et al., Not an Ocean Away, Only a Moment Away: A Prosecutor’s Primer for Obtaining Remotely Stored Data, 47 MITCHELL HAMLINE LAW REVIEW 1073 (2021).

118 Carpenter v. United States, 138 S. Ct. 2206, 2218 (2018) (quoting Riley v. California, 573 U.S. 373, 385 (2014)); Brooke Auxier et al., “Children’s engagement with digital devices, screen time,” Pew Research Center, July 28, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/07/28/childrens-engagement-with-digital-devices-screen-time, last accessed January 15, 2023.

119 “Much of life is now lived online. With the increase in child exploitation and other online harms, middle and high school students need the tools to navigate high-risk situations, in-person or online.” SHIELD Task Force, https://www.shieldwv.com (last accessed January 15, 2023).

120 Dan Blackman & Patryk Szewczyk, The Challenges of Seizing and Searching the Content of Wi-Fi Devices for the Modern Investigator (2015), Australian Digital Forensics Conference, https://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1146&context=adf (last accessed January 15, 2023).

121 Michael Sullivan, Child Sex Abuse Livestreams Increase During Coronavirus Lockdowns, NPR, April 8, 2020, https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/08/828827926/child-sex-abuse-livestreams-increase-during-coronavirus-lockdowns (last accessed January 15, 2023).

122 “For children 7-9 years, 32% of parents report use of social media apps, 50% educational apps only, and 18% no apps.” National Poll on Children’s Health, Sharing Too Soon? Children and Social Media Apps, October 18, 2021, 39(4), University of Michigan Health, https://mottpoll.org/reports/sharing-too-soon-children-and-social-media-apps (last accessed January 25, 2023).

123 Nellie Bowles & Michael Keller, Video Games and Online Chats are “Hunting Grounds” for Sexual Predators, NEW YORK TIMES, Dec. 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/12/07/us/video-games-child-sex-abuse.html (last accessed January 15, 2023).

124 Robert J. Peters et al., Not an Ocean Away, Only a Moment Away: A Prosecutor’s Primer for Obtaining Remotely Stored Data, 47 MITCHELL HAMLINE LAW REVIEW 1073 (2021).

125 Id. at 1107.

126 Id. at 1107-08.

127 Jacqueline G. Schafer, Harnessing AI Innovation for Struggling Families, 2 Journal of Law, Technology & Policy 411 (2020).

128 Glen Pounder, What Does Apple’s Decision to Pause Mean for Children at Risk of Sexual Abuse, Child Rescue Coalition, Sept. 2021, https://childrescuecoalition.org/educations/what-does-apples-decision-to-pause-mean-for-children-at-risk-of-sexual-abuse/ (last accessed January 15, 2023); Richard Lawler, Apple drops controversial plans for child sexual abuse imagery scanning, The Verge, Dec. 2022, https://www.theverge.com/2022/12/7/23498588/apple-csam-icloud-photos-scanning-encryption (last accessed January 15, 2023).

129 E.g. Robert J. Peters et al., Then It Is Forfeit: Forfeiture by Wrongdoing and Criminal Asset Forfeiture in Cases of Child Exploitation and Human Trafficking, forthcoming (2023); Robert J. Peters et al., Exigency and Encrypted Cloud Accounts, Part 1: 8 Introductory Considerations for Prosecutors, Zero Abuse Project (2022); Robert J. Peters et al., Exigency and Encrypted Cloud Accounts, Part 2: 7 Advanced Strategies for Prosecutors, Zero Abuse Project (2022); Joseph Remy et al., Judge, Jury … Service Provider? 6 Strategies for Prosecutors Confronting Objections from Internet Service Providers, Zero Abuse Project (2021); Robert J. Peters et al., Not an Ocean Away, Only a Moment Away: A Prosecutor’s Primer for Obtaining Remotely Stored Data, 47 Mitchell Hamline Law Review 1073 (2021).

130 E.g. Zero Abuse Project’s NOVA (Nexus for Open-Source Virtual Assistance) open-source intelligence tool for child exploitation investigators. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Strengthening ICAC Investigative Tools and Technologies Project, Nov. 2021, https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/funding/awards/15pjdp-21-gk-03271-mecp (last accessed January 15, 2023).

131 APSAC Position Statement on Corporal Punishment of Children, adopted July 16, 2016.

132 Joan E. Durrant, Corporal Punishment: From Ancient History to Global Progress, in Robert Geffner, et al, Handbook of Interpersonal Violence & Abuse Across the Lifespan 343, 354-357 (2022)

133 Id. at 356.

134 Ryan T. Shields, et al, Help Wanted: Lessons on Prevention form Young Adults with Sexual Interest in Prepubescent Children, 105 Child Abuse & Neglect (2020)

135 Id.

136 Allyn Walker, A Long, Dark Shadow 7 (2021); Klaus M. Beier, Ulmut C. Oezdemir, Eliza Schlinizig, Anna Groll, Elena Hupp, Tobias Hellenschmidt, “Just dreaming of them”: The Berlin Project for Primary Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse by Juveniles (PPJ), Child Abuse & Neglect 1, 2 (2016) (“It can be assumed that sexual preference manifests during adolescence and remains stable through the lifespan.”)

137 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014.

138 Pete Singer, Toward a More Trauma-Informed Church: Equipping Faith Communities to Prevent and Respond to Abuse 51 Currents in Mission & Theology 62-76 (2024).

139 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS publication number (SMA). Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. Emphasis in the original.