Abstract

Introduction. More than a decade ago, concerns were raised that menthol in cigarettes might enhance addiction to smoking. This article provides a comprehensive review of published studies examining cigarette dependence among menthol and nonmenthol smokers. The purpose of the review is to evaluate the scientific evidence to determine if menthol increases cigarette dependence. Materials and Methods. The published literature was searched in 2019 for studies that provide evidence on cigarette dependence among menthol compared to nonmenthol smokers. Included in this review are published studies that compare menthol and nonmenthol smokers based on widely accepted and validated measures of dependence, or other established predictors of dependence (age of smoking initiation [first cigarette]/age of progression [regular/daily smoking]) and indicators of dependence (smoking frequency, cigarettes smoked per day, time to first cigarette after waking, night waking to smoke, smoking duration). Results and Conclusion. Based on a review of the available studies, including those with adjusted results and large representative samples, reliable and consistent empirical evidence supports a conclusion that menthol smokers are not more dependent than nonmenthol smokers and thus menthol in cigarettes does not increase dependence.

Introduction

More than a decade ago, concerns were raised that menthol in cigarettes might enhance addiction to smoking.Citation1 The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA) in 2009 explicitly directed the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to refer “the issue of the impact of the use of menthol in cigarettes on the public health” to the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC), for its consideration.Citation2 TPSAC submitted its report on March 23, 2011.Citation3 and the FDA subsequently produced its own preliminary scientific evaluation of the possible public health impact of menthol in cigarettes in July of 2013.Citation4,Citation5 Both the TPSAC and FDA reports relied on selected data from a limited number of studies to arrive at a determination that menthol is associated with increased dependence. Neither report has been updated to accurately and completely reflect the current state of the science.

An assessment of the available scientific evidence through 2013 was conducted and published in this journal to address the question of whether menthol in cigarettes increases dependence.Citation6 The current review is timely, as there continues to be misperceptions in the scientific and regulatory communities about the role of menthol in cigarette dependence, and dozens of new studies have been published. This comprehensive review incorporates findings from the previous reviewCitation6 and new publications in the assessment of the scientific evidence.Citation7 The publications included are those with validated measures of dependence, predictors of dependence, and established indicators of dependence that are widely accepted in the scientific community.

Measures of cigarette dependence, predictors & indicators

There are numerous widely accepted and validated measures of nicotine/cigarette dependence that have been described and reviewed by the World Health Organization (WHO) International Agency for Research on Cancer,Citation8 the U.S. Surgeon General’s Report,Citation9 and the National Cancer Institute’s Monograph 20.Citation10 These measures include the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire (FTQ),Citation11,Citation12 Fagerström Test for Nicotine/Cigarette Dependence (FTND/FTCD),Citation13,Citation14 Cigarette Dependence Scale (CDS-12 and CDS-5),Citation15–17 Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI),Citation18 Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale,Citation19,Citation20 Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (HONC),Citation21 Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM-68 and WISDM-Brief),Citation22,Citation23 Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV),Citation24 and the WHO International Classification of Diseases (ICD).Citation25 A discussion of the psychometric properties of each measure is beyond the scope of this review. Summaries of reliability, structure, validity, and heritability of these measures are available elsewhere.Citation8

Predictors of dependence (age of first cigarette/age of progression to regular/daily smoking) and indicators of dependence (smoking frequency, time to first cigarette after waking [TTFC], night waking to smoke, cigarettes smoked per day [CPD], and smoking duration) were described previously,Citation6 and the rationale for their inclusion as predictors and indicators (i.e., significant associations with progression to regular smoking, continued smoking, greater smoking intensity, and difficulty quitting) remains the same.Citation10,Citation26 Briefly, early onset of smoking is associated with greater likelihood of developing cigarette dependence.Citation10 Indicators of dependence include single-item measures that are among the “associated features” of tobacco use disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5).Citation26

Materials and methods

Identifying menthol dependence-related literature

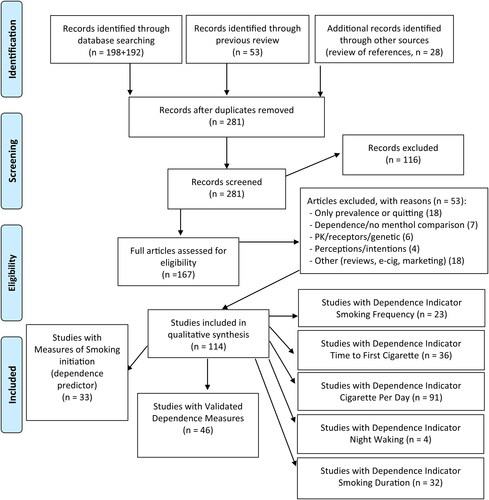

The published literature was searched in 2019 for studies that provide evidence on cigarette dependence among menthol compared to nonmenthol smokers that were published in January 2014 through November 2019. Specific dates and terms included in this PubMed search are as follows: ((“menthol”[MeSH Terms] OR “menthol”[All Fields]) AND (“tobacco products”[MeSH Terms] OR (“tobacco”[All Fields] AND “products”[All Fields]) OR “tobacco products”[All Fields] OR “cigarettes”[All Fields])) AND (“2014/01/01”[PDAT]: “2019/11/30”[PDAT]). Inclusion criteria specified that the studies were available in English and reported a validated dependence measure, predictor, or indicator of dependence in menthol and nonmenthol smokers. The search was repeated with “smoking” replacing “tobacco.” Publications cited in the previous review, as identified by previous search criteria,Citation6 are also included in the current review. The new searches described above returned 390 publications. After removing duplicates and those that were not relevant based on title/abstract review, and inclusion of previously identified studies, 167 publications were reviewed and 114 are included in this narrative review. The identified publications included those with menthol and nonmenthol smoker comparisons and validated dependence measures (n = 46), predictors (age of smoking initiation/age of progression, n = 33), or indicator of dependence (smoking frequency, n = 23; time to first cigarette, n = 36; night waking, n = 4; cigarettes per day, n = 91; and smoking duration, n = 32) (Refer to . Flow Diagram). The review attempts to be inclusive of all published studies, and all results provided within those studies (means, percentages, odds ratios) for the validated measures, predictors, and indicators of dependence described above among menthol and nonmenthol smokers.

In the current review, evidence from all previous and newly identified publications is included. Due to the large number of studies, results are presented by measure (validated measures, predictors, and indicators of dependence). For validated dependence measures the specific measures reported, sample size, adjusted odds ratio (AOR), means, percentages, and p-values are reported in and . Studies which included validated measures of dependence are summarized in greater detail in the results as these are most directly relevant to the research question. Some studies include multiple measures and multiple analyses and are cross-referenced in the appropriate summaries. Findings include those related to prevalence, severity and duration, as reported by authors of individual studies.

Table 1. Validated and widely accepted measures of cigarette dependence in menthol and nonmenthol smokers - results from adjusted analyses.

Table 2. Validated measures of cigarette dependence in menthol and nonmenthol smokers - unadjusted results - mean values and percentages.

Results

Validated and widely accepted dependence measures

A total of 17 published studies, which compare menthol and nonmenthol smokers based on a validated measure of cigarette dependence,Citation27–Citation43 were included in the 2014 review.Citation6 In that review, studies consistently showed that menthol smokers scored the same or lower on cigarette dependence measures as nonmenthol smokers.Citation6 For the current review, findings from an additional 29 publications,Citation6,Citation44–Citation71 are summarized. Studies that examine dependence using a validated measure (FTND, FTQ, HSI, HONC, NDSS, WISDM) and that provide results based on adjusted analyses that control for potentially confounding variables are presented in , while those with unadjusted comparisons are presented in .

In the previous and current reviews combined, 12 studies report adjusted results. The remaining studies and comparisons include unadjusted results. Newly identified studies are described below, and all results are included in (adjusted) and (unadjusted). Results from large and more representative population samplings have findings that are more generalizable.

Summary of new menthol studies indicating no greater dependence

Adjusted results

Curtin and colleaguesCitation44 reported findings based on analysis of data from three nationally representative U.S. government surveys (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, NHANES; Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey, TUS-CPS; and National Survey on Drug Use and Health, NSDUH). These analyses controlled for current age category, gender, and race/ethnicity. Based on HSI category distributions across three smoking frequencies (smoked ≥ 1 day, ‘past-month smokers’; smoked ≥10 days, ‘regular smokers’; smoked daily, ‘daily smokers’), adult menthol smokers were either no more dependent (NHANES), or possibly less dependent (TUS-CPS) than nonmenthol smokers. Among adolescent smokers (NHANES, TUS-CPS), estimates indicated no differences in HSI category distributions based on menthol status.Citation44 In the analysis of NSDUH data, HSI category distributions were approximated (i.e., survey CPD categories of 6 to 15 and 16 to 25 were used to approximate the HSI CPD category of 11-20). These estimates indicated no statistically increased odds of reporting a high versus low HSI score, when comparing menthol to nonmenthol smokers.Citation44 Among 10,760 adult smokers from eight European countries, menthol smokers had significantly reduced adjusted odds for HSI score ≥4 compared to smokers of nonmenthol (unflavored) cigarettes in three separate models.Citation67

Kasza and colleaguesCitation49 examined HSI scores among menthol versus nonmenthol smokers overall, by race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, Black, Hispanic), and by switching status over eight survey waves based on a representative sample of 5,932 U.S. adult smokers in the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey (ITC-4). Controlling for age, gender, education, income, quit intention, time, and instrument change, there were no statistically significant increased or decreased odds of menthol use in the HSI 2-3 (with the exception of Hispanics, described below) or in the HSI 4-6 categories overall, or by race/ethnicity (i.e., 95% confidence intervals (CI) for all other odds ratios included 1.0).Citation49 This study also examined dependence among those who switched between menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes and found that those who switched from menthol to nonmenthol had reduced odds of higher scores, and nonmenthol to menthol switchers likewise had a reduced OR for the highest HSI scores.Citation49

In an original analysis published within the previous review,Citation6 the relationship between menthol status and FTND scores among 3,341 U.S. adult smokers in the Total Exposure Study (TES) was examined. In the analysis adjusted for age, race, gender, education, and tar yield category, menthol did not increase the odds of higher FTND (regardless of score categorization - the five FTND categories; low/medium versus high; or low, medium, high). The interaction term for menthol by race on FTND scores was not significant. Tested separately, there was also no effect of menthol status on HSI score. These authors found no statistically significant increased odds of menthol use in any of the FTND categories in any of the analyses (p-values >0.05, all 95% CIs included 1.0).Citation6

Three additional new studies include results from adjusted analyses with smaller and less representative samples of smokers. Young-Wolff and colleagues examined correlates of menthol smoking among 1,042 smokers with serious mental illness, recruited from seven acute inpatient psychiatric units in the San Francisco Bay area. In this population, dependence was not significant in the bivariate model and the authors found no increased odds of menthol use by FTND score (AOR 1.02, 0.97-1.08).Citation50 Three nicotine dependence scales were examined in a multiethnic community sample of 186 young adult daily smokers (ages 18-35 years) in Hawaii, and no statistically significant difference in FTND, NDSS, or WISDM-Brief scores for menthol compared to nonmenthol smokers were reported in the adjusted (body mass index [BMI], gender, education, race/ethnicity, marital status, quit attempts, employment, alcohol, and marijuana use) analyses.Citation46 The authors also examined for interactions of menthol with gender and race/ethnicity for each nicotine dependence scale, and did not find any significant interactions. Finally, in a stratified inpatient sample of 136 adult smokers, Ahijevych and colleagues reported that after adjusting for age, gender, race, education, and cotinine, there was no significant difference between menthol and nonmenthol smokers in measures of dependence (FTND, data not shown).Citation62

As noted above, includes a complete listing of all publications that included a validated and widely accepted measure of dependence in menthol and nonmenthol smokers, and that adjusted for potentially confounding variables.

Unadjusted results

Findings from studies with unadjusted analyses are consistent with results from the adjusted analyses and are cross-referenced, as applicable, below. These results, as detailed in , include no difference in HSI based on data from NHANES and TUS-CPS, among both adult and youth smokers;Citation44 lower mean HSI score for menthol compared to smokers of unflavored cigarettes among 10,760 adult smokers from eight European countries;Citation67 no statistically significant difference in mean FTND scores among menthol versus nonmenthol smokers in the TES;Citation6 no statistically significant difference in FTND score among smokers with serious mental illness;Citation50 no statistically significant difference between menthol and nonmenthol smokers for NDSS or FTND mean scores in the multi-ethnic sample of young adults in Hawaii described above;Citation46 and no difference in FTND scores among a stratified inpatient sample of menthol and nonmenthol smokers.Citation62

The remaining available studies report on dependence measures in a variety of samples. These results include no statistically significant difference by menthol status in FTND score among both Hispanic and non-Hispanic women;Citation52 no difference in FTND by menthol status among non-treatment seeking heavy smokers;Citation45 and no difference in FTND mean scores,Citation56,Citation59 or in FTND mean scores or categoriesCitation47 in smaller lab-based studies. No significant correlation between menthol status and FTND score was found among 420 African American adult smokers.Citation80

Other studies have reported no difference in mean FTND scores among menthol and nonmenthol smokers in a lab-based assessment of reduced nicotine cigarettes,Citation64 no significant difference by menthol status for FTCD (FTND) scores in two comparisons of menthol and nonmenthol smokers who participated in a clinical study in Japan,Citation66 no difference in mean FTND scores by menthol status in two low-income, racially/ethnically diverse cohorts of pregnant smokers,Citation68 and no difference in mean FTND scores among 81 young adult smokers with serious mental illness.Citation61 Among 341 participants in a clinical study, statistically significantly lower mean baseline FTND scores were reported for menthol as compared to nonmenthol smokers.Citation57 These authors also reported no statistically significant difference in mean HONC scores or in a new dependence measure, the Penn State Cigarette Dependence Index.Citation57

Studies have found no statistically significant difference by menthol status in HSI scores among smokers with both faster and slower nicotine metabolism;Citation48 similar percentages of menthol and nonmenthol smokers in each HSI category among participants in a cross-over study;Citation51 no difference in the percent menthol smokers in each HSI category among 169 participants in lab-based assessment of reduced nicotine cigarettes;Citation60 and no difference in HSI scores among 115 African American smokers in a cessation study.Citation65 Three additional small studies also found no significant difference in FTQ scores.Citation69–71

Discordant findings

A few analyses have reported findings that are discordant with the results noted above in some subgroups of menthol smokers. The Curtin et al.Citation44 analysis of NSDUH data suggested slight statistically increased adjusted odds of reporting a moderate versus low approximated HSI score among menthol past-month smokers and those who smoked at least 10 days in past month, but not among daily smokers. Kasza and colleaguesCitation49 reported that Hispanic smokers with HSI scores of 2-3 had an increased odds (AOR 1.81, 95% CI 1.25, 2.61) of menthol use compared to those with an HSI score of 0-1, but as noted above, no other statistically differences were found overall or by race/ethnicity. Two recent publications developed from a lab-based population of smokers the authors describe as “DSM-V dependent” reported that “DSM-V dependent” menthol smokers have higher FTND scores compared to “DSM-V dependent” nonmenthol smokers (5.4 versus 4.6, p < 0.05).Citation53,Citation58

In one of their unadjusted analyses, Fagan et al. reported higher mean scores on the WISDM-Brief among menthol smokers (45.8 vs 40.2, p = 0.01). However, no differences were reported for the unadjusted NDSS and FTND scores or any of the three measures in the adjusted results, as noted previously.Citation46 Finally, a larger cessation study (n = 1,439 smokers) reported an unadjusted 0.2 point higher mean FTND score for menthol smokers (p = 0.03); however, menthol smokers (both African American and White smokers) and nonmenthol smokers (White smokers only) in this sample differed on many characteristics including gender, education level, marital status, employment status, and by other smoking characteristics.Citation55

includes a complete listing of all publications that include unadjusted results for a validated measure of dependence in menthol and nonmenthol smokers. Additional details regarding the unadjusted analyses, including sample size and statistical significance (if reported), are provided in .

Predictors of dependence - age of smoking initiation and age of progression

Previously, there were 16 publications that consistently reported that menthol smokers have the same or later mean age of first use and the same or later mean age of regular smoking compared to nonmenthol smokers.Citation28,Citation30,Citation31,Citation34,Citation39,Citation72–82 Seventeen additional publicationsCitation45,Citation46,Citation51,Citation52,Citation55,Citation59,Citation61,Citation63,Citation64,Citation83–90 with information on age of smoking initiation [first cigarette] or age of progression [regular/daily smoking] were identified and are included here. All newly identified studies provide evidence of no difference or later age of smoking initiation/age of progression among menthol versus nonmenthol smokers. The evidence supporting that menthol smokers do not initiate smoking or progress to regular smoking at earlier ages include numerous publications based on nationally representative surveys and other large studies with both adjusted analysesCitation72,Citation74,Citation76,Citation77,Citation79,Citation83 and unadjusted analyses.Citation72,Citation73,Citation82,Citation84–88,Citation90

Only two analyses reported findings that are discordant and include statistically significant younger age of smoking initiation/age of progression with menthol cigarettes. In both instances the sample sizes were large, and the differences were small (≤ 0.3 years). One suggested a small but statistically significant younger mean age of first regular smoking only among adolescents in TUS-CPS (14.90 years versus 15.06 years).Citation83 In the other example, among current smokers ages 45-80, a small statistically significant younger mean age of first cigarette (16.7 vs. 17.0 years) was reported among those who ever smoked menthol in the unadjusted analysis, but age of first cigarette was not a predictor of ever menthol use when adjusted for covariates.Citation88

Indicators of dependence (i.e., smoking frequency, time to first cigarette, night waking to smoke, cigarettes per day, and smoking duration)

Smoking frequency

Eight publications included information on smoking frequency in the 2014 review, and all reported menthol smokers were statistically significantly less likely to be daily smokers compared to nonmenthol smokers or that there was no difference in smoking frequency.Citation35,Citation36,Citation73,Citation74,Citation78,Citation79,Citation91,Citation92 For the current review, 15 publications were identified as including information on smoking frequency.Citation46,Citation67,Citation83,Citation86,Citation89,Citation93–102 Nearly all of the new studies provide evidence of either no difference or less frequent smoking among menthol smokers. Studies supporting that menthol smokers are not more likely than nonmenthol smokers to be daily smokers or to smoke more frequently include multiple publications with adjusted analyses of large and representative survey dataCitation35,Citation67,Citation74,Citation79,Citation83,Citation92,Citation97 and unadjusted analyses from other representative and large studies.Citation36,Citation73,Citation87,Citation89,Citation91,Citation93,Citation96

Two publications include discordant findings. Based on 19,889 participants in the 2013-2014 NSDUH, a higher percentage of menthol smokers were reported to be daily smokers compared to nonmenthol smokers, however it appears daily and non-daily smoking may have been mislabeled, because no other analyses of NSDUH or other nationally representative surveys would support that the majority of smokers in the U.S. were non-daily smokers.Citation100 A recently published analysis of PATH data reported a lower percentage of non-daily smoking among menthol smokers (based on last cigarette smoked or usual brand) compared to nonmenthol smokers, but smokers who used menthol flavor capsules were significantly more likely to be non-daily smokers.Citation86

Time to first cigarette (TTFC)

The 2014 review included 17 publicationsCitation28,Citation32,Citation34,Citation37,Citation38,Citation43,Citation73,Citation76,Citation78,Citation79,Citation81,Citation93,Citation103–107 with a menthol comparison and dozens of analyses, with most of the studies and analyses that examined TTFC reporting no statistically significant difference between menthol and nonmenthol smokers.Citation28,Citation34,Citation37,Citation43,Citation78,Citation79,Citation81,Citation93,Citation104,Citation106,Citation107 Some studies reported mixed findings (both no difference and shorter/longer) within the same study).Citation73,Citation105 This review includes results from 19 publications with original data and a recent meta-analysis.Citation6,Citation36,Citation44,Citation46,Citation49,Citation50,Citation51,Citation62,Citation67,Citation75,Citation84,Citation86,Citation98,Citation102,Citation108–112

Many of the newly identified analyses report no difference in TTFC among menthol and nonmenthol smokers overall and in a number of subgroups.Citation36,Citation46,Citation49,Citation50,Citation62,Citation86,Citation98,Citation102,Citation108–Citation110 Studies supporting that menthol smokers have the same or later TTFC as nonmenthol smokers include numerous publications from large or representative studies with adjusted results6,Citation36,Citation44,Citation49,Citation67,Citation79,Citation107,Citation109,Citation110 and unadjusted results from other large or representative surveys.Citation73,Citation87,Citation89,Citation91,Citation93,Citation96

Some publications have reported discordant TTFC results (i.e., no difference and longer or shorter TTFC). For example, a recent meta-analysis of studies reported odds of smoking within the first 5 minutes of waking were slightly elevated for menthol smokers (fixed-effect OR 1.10; random-effects OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.04-1.21) based on 13 included estimates, while odds of smoking within the first 30 minutes were not statistically significant (fixed-effect OR 1.01; random-effects OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.96-1.16) based on 17 estimates included in the meta-analysis.Citation111 Another publication reports shorter TTFC among adult menthol smokers in NSDUH, statistically significantly longer TTFC among adult and adolescent menthol smokers in the TUS-CPS and among adolescent menthol smokers in NHANES, and no difference in TTFC among adults in NHANES.Citation44 Other analyses of TUS-CPS suggest no difference in weighted percentages of menthol and nonmenthol smokers reporting TTFC ≤ 5 minutes and TTFC 31-60 minutes, and a greater percent of menthol smokers in the 6-30 minutes and > 60 minutes categories.Citation84 In the Total Exposure Study, there was no difference in the odds of menthol smoking for TTFC ≤ 30 minutes, TTFC ≤ 5 minutes, and in the TTFC 6-30 minutes category, and menthol smokers had increased odds of longer TTFC (> 60 minutes).Citation6 Among smokers from eight European countries, menthol smokers were less likely to smoke in the first 5 minutes and first 30 minutes of waking, and were more likely to have longer TTFC (>60 minutes).Citation67 Studies suggesting shorter TTFC include a small cross-over study with partial TTFC results,Citation51 and two unadjusted analysis of percentages of menthol and nonmenthol smokers in TTFC categories.Citation75,Citation112

Night waking to smoke

Only two publications that include night waking to smoke information were identified in the 2014 review,Citation75,Citation113 and both found a higher percentage of menthol compared to nonmenthol smokers reported they sometimes wake at night to smoke. Two additional publications were identified for the current review,Citation84,Citation109 both of which analyze data from the TUS-CPS. In one analysis, 11.6% of nonmenthol and 13.8% of menthol smokers reported sometimes waking at night to smoke.Citation84 The other study found that menthol smokers in a larger subsample had statistically significant increased odds of sometimes waking at night to smoke, whereas no statistically significantly difference was found for the smaller subsample.Citation109

Cigarettes per day (CPD)

In the 2014 review,Citation6 31 publications with more than four dozen separate analyses provided information on CPD among menthol and nonmenthol smokers.Citation30,Citation32,Citation34,Citation37–39,Citation42,Citation43,Citation72,Citation73,Citation75–82,Citation90,Citation104,Citation114,–124 In that review, more than two dozen analyses found no statistically significant difference in CPD for menthol versus nonmenthol smokers, including various subgroup analyses and in the overall sample. More than two dozen other published analyses found fewer CPD for menthol versus nonmenthol smokers. For the current review, 60 relevant publications with comparisons were identified.Citation6,Citation28,Citation29,Citation44–46,Citation49–57,Citation59,Citation61–71,Citation84–86,Citation89,Citation93–102,Citation105,Citation107–110,Citation125–138

The vast majority of these publications (>95%) report that menthol smokers smoke the same or fewer cigarettes per day compared to nonmenthol smokers. Studies reporting no difference in CPD or fewer CPD for menthol compared to nonmenthol smokers include several publications with adjusted analyses of large or representative samples of smokersCitation6,Citation44,Citation49,Citation72,Citation76,Citation77,Citation79,Citation97,Citation98,Citation105,Citation107,Citation109,Citation110,Citation116,Citation117,Citation120 and unadjusted analyses of large or representative surveys.Citation84,Citation86,Citation92,Citation96Citation100,Citation108,Citation125

Discordant findings within studies include an analysis of PATH data on 1,838 youth who had ever smoked, where authors reported statistically significantly fewer CPD among past 30 day smokers with a menthol usual brand, and also reported a smaller percentage of menthol smokers in lower CPD categories when analysis included any menthol use.Citation85 Higher CPD was reported among White menthol smokers compared to White nonmenthol smokers in one unadjusted analysis of data from the TES, but no difference by menthol status for other groups (race, gender, tar category) or overall.Citation127 Greater CPD was reported among Black menthol smokers compared to nonmenthol smokers, but not White smokers in a small lab-based study.Citation71 In one cessation study there was no significant difference in mean CPD, but a significant difference in CPD categories was observed.Citation65 Two studies report greater CPD among menthol as compared to nonmenthol smokers. These studies included an analysis of underage smokers in the Southern United StatesCitation118 and among adolescent smokers in Canada.Citation134

Smoking duration/pack years

There were 12 publications in the 2014 review, reporting no difference in smoking duration,Citation42,Citation43,Citation81 or shorter smoking duration among menthol versus nonmenthol smokers,Citation34,Citation73,Citation114,Citation115,Citation119,Citation121,Citation123,Citation139 or both shorter and no difference.Citation40 Twenty additional relevant publications were identified.Citation27,Citation28,Citation30,Citation45,Citation47,Citation55,Citation56,Citation62,Citation65,Citation69–71,Citation88,Citation94,Citation116,Citation130,Citation131,Citation132,Citation136,Citation138

With one exception, all new studies support either no difference or shorter smoking duration among menthol compared to nonmenthol smokers. Studies supporting that menthol smokers have the same or shorter smoking duration include three publications with adjusted analysesCitation27,Citation81,Citation88 and unadjusted results from numerous nationally representative surveys and other large studies.Citation73,Citation114,Citation115,Citation116,Citation119,Citation121,Citation123,Citation131,Citation132,Citation139

Significantly longer smoking duration was reported among 60 menthol smokers compared with 67 nonmenthol smokers in one small exposure study, however menthol smokers were significantly older than nonmenthol smokers in this analysis.Citation28

Discussion

The weight of the scientific evidence, including studies that are based on large or representative samples with both unadjusted and adjusted results, demonstrates that menthol smokers compared to nonmenthol smokers are not more dependent based on validated and widely accepted measures of cigarette dependence, predictors, or indicators.

Nearly all of more than 45 available publications with a validated measure of dependence, particularly those with adjusted analyses and large or representative samples, and including more than 70 comparisons, support that menthol smokers have the same (no statistically significant difference) or lower dependence than nonmenthol smokers. Schauer and colleagues also reported on “dependence” among menthol and nonmenthol smokers by marijuana use status based on 2005-2014 NSDUH data. These dependence results are based on a modified version of the NDSS and one question from the FTND, and provide further support that menthol smokers are not more dependent than nonmenthol smokers.Citation100 The few analyses that are discordant with the results noted above are generally from small differences in unadjusted results or in only some subgroups of menthol smokers.

Now more than 30 publications, including those with adjusted analyses and large or representative samples, have consistently reported that menthol smokers have the same or later mean age of first use and the same or later mean age of regular smoking. Two analyses reported an earlier age of smoking initiation or age of progression (both ≤ 0.3 years) among menthol compared to nonmenthol smokers; the statistical significance of this small difference is likely attributable to the large sample sizes. Both publications also report no difference or later age of smoking initiation/age of progression in their adjusted analyses.

Among more than 20 publications with data on smoking frequency, only two publications suggest menthol smokers are more likely to be daily smokers. One appears to have daily and non-daily smoking mislabeled in the tableCitation100 and the other found no difference for another group of menthol smokers.Citation86

TTFC among menthol and nonmenthol smokers has now been reported in more than 35 publications, with dozens of analyses, and one meta-analysis. While some researchers have focused on the TTFC ≤5 minutes comparisons, the TTFC >60 minutes comparison is an equally important predictor of cessation outcomes.Citation140 Of the dozens of analyses available, and in particular those with adjusted analyses and large or representative samples, most report no difference. Both longer and shorter TTFC among menthol compared to nonmenthol smokers are also reported.

Four publications include a measure of sometimes waking at night to smoke. Night waking to smoke is a less commonly used indicator of dependence; hence, there are few reports, with inconsistent results.

This review includes more than 90 publications with multiple analyses of CPD. Nearly all, including those with adjusted analyses and large or representative samples, suggest no difference or fewer CPD among menthol versus nonmenthol smokers. Only a few analyses in this review have suggested a higher cigarette consumption among specific subgroups of menthol smokers.

Of the more than 30 publications with smoking duration or pack years, only one small study reported longer duration, but this was consistent with an age effect rather than a menthol effect.Citation28

A strength of this review is its comprehensive assessment of validated measures, predictors and indicators of dependence in menthol and nonmenthol smokers. A limitation of this review is that no formal assessment of study quality was conducted. Beyond the extensive body of literature included in this review, there may be other publications that include dependence measures or indicators as part of the description of sample characteristics that were not identified in the literature searches conducted. Another limitation to any comprehensive scientific review, including this review, is that it can only include what is published. There are also analyses that have been presented to the FDA and TPSAC, but results were not included in subsequent publications. This review also excluded studies where menthol and nonmenthol results were reported in separate publications, and studies that rely on infrequently used or modified (i.e., not validated) measures. Whereas most of the available studies were not specifically designed to address the impact of menthol on cigarette dependence, and individual studies may be limited in their generalizability, the weight of available scientific evidence is substantial.

In evaluating discordant findings, there are several important factors that merit consideration. First, studies that do not adjust for sociodemographic differences between groups may find significant differences that are unrelated to menthol (e.g., age and smoking duration). It is also important to note that very large studies may find statistically significant differences that are not meaningful (e.g., a 0.2 difference on a 10-point dependence scale). Some findings may be due to the disproportionate focus on a single timepoint (≤5 min) on a TTFC scale versus the complete information (all timepoints, including >60 minutes). With the large number of analyses to date, some inconsistent results may simply be due to chance.

Conclusions

The extensive body of scientific evidence evaluated in this review reveals that the weight of the evidence does not support that menthol in cigarettes increases dependence, regardless of the established measure tested, the population studied, the size of the sample, or the level of control for potentially confounding variables. The most direct evidence of any impact of menthol in cigarettes is from widely accepted and validated measures, which shows that menthol smokers are not any more dependent on cigarettes than nonmenthol smokers. Additionally, menthol smokers have the same or later age of first cigarette smoked and the same or later age of progression to regular smoking when compared with nonmenthol smokers. Menthol smokers are less or equally likely to smoke daily, generally have similar TTFC, smoke fewer or the same CPD, and have shorter or the same duration of smoking as compared to nonmenthol smokers. Reliable and consistent empirical evidence supports a conclusion that menthol smokers are not more dependent than nonmenthol smokers and thus menthol in cigarettes does not increase dependence.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge our colleagues Paul Ayres, Johnni Bibbins, John Caraway, Tiffany Parms, and Elaine Round for critical review and comments on early drafts of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

All authors are current employees of RAI Services Company.

References

- Henningfield JE, Benowitz NL, Ahijevych K, Garrett BE, Connolly GN, Wayne GF. Does menthol enhance the addictiveness of cigarettes? An agenda for research. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003; 5:9–11. doi:10.1080/1462220031000070543.

- Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA). Section 907 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act - Tobacco Product Standards. http://www.fda.gov/tobaccoproducts/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/ucm263053.htm (accessed March 27, 2019).

- Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. Menthol cigarettes and public health: review of the scientific evidence and recommendations. https://wayback.archiveit.org/7993/20170405201731/ https://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM269697.pdf (accessed March 27,2019).

- Food and Drug Administration. Preliminary scientific evaluation of the possible public health effects of menthol versus nonmenthol cigarettes. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/ucm361598.pdf (accessed March 27, 2019).

- Food and Drug Administration. Reference addendum: preliminary scientific evaluation of the possible public health effects of menthol versus nonmenthol cigarettes. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/ProductsIngredientsComponents/UCM449273.pdf (accessed March 27, 2019).

- Frost-Pineda K, Muhammad-Kah R, Rimmer L, Liang Q. Predictors, indicators, and validated measures of dependence in menthol smokers. J Addict Dis. 2014;33(2):94–113. doi:10.1080/10550887.2014.909696.

- Committee on the Development of the Third Edition of the Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence, Committee on Science TLC, Policy and Global Affairs (PGA), Federal Judicial Center, National Research Council. Reference manual on scientific evidence. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Methods for evaluating cancer control policies. Vol. 12. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2008. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. How tobacco smoke causes disease: the biology and behavioral basis for smoking - attributable disease: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2010.

- National Cancer Institute. Phenotypes and endophenotypes: foundations for genetic studies of nicotine use and dependence. In: Swan GE, Baker TB, Chassin L, Conti DV, Lerman C, Perkins KA, editors. Tobacco Control Monograph No. 20. NIH Publication No. 09-6366. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2009. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Fagerström KO. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav. 1978;3:235–241. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2.

- Fagerström KO, Schneider NG. Measuring nicotine dependence: a review of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. J Behav Med. 1989;12:159–182. doi:10.1007/BF00846549.

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x.

- Fagerström KO. Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerström test for cigarette dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:75–78.

- Etter JF, Le Houezec J, Perneger TV. A self-administered questionnaire to measure dependence on cigarettes: the cigarette dependence scale. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:359–370. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300030.

- Etter JF, Le Houezec J, Huguelet P, Etter M. Testing the Cigarette Dependence Scale in 4 samples of daily smokers: psychiatric clinics, smoking cessation clinics, a smoking cessation website and in the general population. Addict Behav. 2009;34:446–450. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.12.002.

- Okuyemi KS, Pulvers KM, Cox LS, Thomas JL, Kaur H, Mayo MS, Nazir N, Etter JF, Ahluwalia JS. Nicotine dependence among African American light smokers: A comparison of three scales. Addict Behav. 2007;32:1989–2002. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.002.

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br J Addict. 1989;84:791–800. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x.

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ, Hickcox M. The nicotine dependence syndrome scale: a multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:327–348. doi:10.1080/1462220042000202481.

- Shiffman S, Sayette MA. Validation of the nicotine dependence syndrome scale (NDSS): a criterion-group design contrasting chippers and regular smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:45–52. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.009.

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Rigotti NA, Ockene JK, McNeill AD, Coleman M, Wood C. Trait anxiety and nicotine dependence in adolescents: a report from the DANDY study. Addict Behav. 2004;29:911–919. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.021.

- Piper ME, Piasecki TM, Federman EB, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB. A multiple motives approach to tobacco dependence: the Wisconsin inventory of smoking dependence motives (WISDM-68) J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:139–154. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.139.

- Smith SS, Piper ME, Bolt DM, Fiore MC, Wetter DW, Cinciripini PM, Baker TB. Development of the brief Wisconsin inventory of smoking dependence motives. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(5):489–499. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntq032.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems - 10th revision. Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Hooper MW, Zhao W, Byrne MM, Davila E, Caban-Martinez A, Dietz NA, Parker DF, Huang Y, Messiah A, Lee DJ. Menthol cigarette smoking and health, Florida 2007 BRFSS. Am J Health Behav. 2011;31(1):3–14. doi:10.5993/AJHB.35.3.3.

- Benowitz NL, Dains KM, Dempsey D, Havel C, Wilson M, Jacob P., 3rd. Urine menthol as a biomarker of mentholated cigarette smoking. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:3013–3019. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0706.

- Brody AL, Mukhin AG, La Charite J, Ta K, Farahi J, Sugar CA, Mamoun MS, Vellios E, Archie M, Kozman M, Phuong J, Arlorio F, Mandelkern MA. Up-regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in menthol cigarette smokers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:957–966. doi:10.1017/S1461145712001022.

- Okuyemi KS, Faseru B, Sanderson Cox L, Bronars CA, Ahluwalia JS. Relationship between menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation among African American light smokers. Addiction. 2007;102:1979–1986. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02010.x.

- Allen B, Jr., Unger JB. Sociocultural correlates of menthol cigarette smoking among adult African Americans in Los Angeles. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:447–451. doi:10.1080/14622200701239647.

- Collins CC, Moolchan ET. Shorter time to first cigarette of the day in menthol adolescent cigarette smokers. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1460–1464. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.10.001.

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, Ockene JK, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, Coleman M, Wood C. Recollections and repercussions of the first inhaled cigarette. Addict Behav. 2004;29:261–272. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.002.

- Faseru B, Choi WS, Krebill R, Mayo MS, Nollen NL, Okuyemi KS, Ahluwalia JS, Cox LS. Factors associated with smoking menthol cigarettes among treatment-seeking African American light smokers. Addict Behav. 2011;36:1321–1344. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.015.

- Li J, Paynter J, Arroll B. A cross-sectional study of menthol cigarette preference by 14- to 15-year-old smokers in New Zealand. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:857–863. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr299.

- Marsh L, McGee R, Gray A. A refreshing poison: one-quarter of young New Zealand smokers choose menthol. Aust New Zealand J Public Health. 2012;36:495–496. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00926.x.

- Muscat JE, Chen G, Knipe A, Stellman SD, Lazarus P, Richie JP Jr. Effects of menthol on tobacco smoke exposure, nicotine dependence, and NNAL glucuronidation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(1):35–41. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0744.

- Okuyemi KS, Ahluwalia JS, Ebersole-Robinson M, Catley D, Mayo MS, Resnicow K. Does menthol attenuate the effect of bupropion among African American smokers? Addiction. 2003;98:1387–1393. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00443.x.

- Okuyemi KS, Ebersole-Robinson M, Nazir N, Ahluwalia JS. African-American menthol and nonmenthol smokers: differences in smoking and cessation experiences. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96:1208–1211.

- Reitzel LR, Etzel CJ, Cao Y, Okuyemi KS, Ahluwalia JS. Associations of menthol use with motivation and confidence to quit smoking. Am J Health Behav. 2013a;37:629–634. doi:10.5993/AJHB.37.5.6.

- Reitzel LR, Li Y, Stewart DW, Cao Y, Wetter DW, Waters AJ, Vidrine JI. Race moderates the effect of menthol cigarette use on short-term smoking abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013b;15:883–889. doi:10.1093/ntr/nts335.

- Winhusen TM, Adinoff B, Lewis DF, Brigham GS, Gardin JG 2nd, Sonne SC, Theobald J, Ghitza U. A tale of two stimulants: mentholated cigarettes may play a role in cocaine, but not methamphetamine, dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:845–851. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.09.002.

- Rojewski AM, Toll BA, O’Malley SS. Menthol cigarette use predicts treatment outcomes of weight-concerned smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:115–119. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntt137.

- Curtin GM, Sulsky SI, Van Landingham C, Marano KM, Graves MJ, Ogden MW, Swauger JE. Primary measures of dependence among menthol compared to non-menthol cigarette smokers in the United States. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;69(3):451–466. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.05.011.

- DeVito EE, Valentine GW, Herman AI, Jensen KP, Sofuoglu M. Effect of menthol-preferring status on response to intravenous nicotine. Tob Reg Sci. 2016;2(4):317–328. doi:10.18001/TRS.2.4.4.

- Fagan P, Pohkrel P, Herzog T, Pagano I, Vallone D, Trinidad DR, Sakuma KL, Sterling K, Fryer CS, Moolchan E. Comparisons of three nicotine dependence scales in a multiethnic sample of young adult menthol and non-menthol smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;149:203–211. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.005.

- Hsu PC, Lan RS, Brasky TM, Marian C, Cheema AK, Ressom HW, Loffredo CA, Pickworth WB, Shields PG. Menthol smokers: metabolomic profiling and smoking behavior. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(1):51–60. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0124.

- Jao NC, Veluz-Wilkins AK, Smith MJ, Carroll AJ, Blazekovic S, Leone FT, Tyndale RF, Schnoll RA, Hitsman B. Does menthol cigarette use moderate the effect of nicotine metabolism on short-term smoking cessation? Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;25(3):216–222. doi:10.1037/pha0000124.

- Kasza KA, Hyland AJ, Bansal-Travers M, Vogl LM, Chen J, Evans SE, Fong GT, Cummings KM, O’Connor RJ. Switching between menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes: findings from the U.S. cohort of the international tobacco control four country survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(9):1255–1265. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu098.

- Young-Wolff KC, Hickman NJ 3rd, Kim R, Gali K, Prochaska JJ. Correlates and prevalence of menthol cigarette use among adults with serious mental illness. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(3):285–291. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu141.

- Watson CV, Richter P, de Castro BR, Sosnoff C, Potts J, Clark P, McCraw J, Yan X, Chambers D, Watson C. Smoking behavior and exposure: results of a menthol cigarette crossover study. Am J Health Behav. 2017;41(3):309–319. doi:10.5993/AJHB.41.3.10.

- Oncken C, Feinn R, Covault J, Duffy V, Dornelas E, Kranzler HR, Sankey HZ. Genetic vulnerability to menthol cigarette preference in women. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(12):1416–1420. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv042.

- Perkins KA, Kunkle N, Karelitz JL. Threshold dose for behavioral discrimination of cigarette nicotine content in menthol vs. non-menthol smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2017;234(8):1255–1265. doi:10.1007/s00213-017-4563-3.

- Round EK, Chen P, Taylor AK, Schmidt E. Biomarkers of tobacco exposure decrease after smokers switch to an e-cigarette or nicotine gum. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(9):1239–1247. . doi:10.1093/ntr/nty140.

- Smith SS, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Smoking cessation in smokers who smoke menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes. Addiction. 2014;109(12):2107–2117. doi:10.1111/add.12661.

- Zuo Y, Mukhin AG, Garg S, Nazih R, Behm FM, Garg PK, Rose JE. Sex-specific effects of cigarette mentholation on brain nicotine accumulation and smoking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(4):884–892. doi:10.1038/npp.2014.263.

- Veldheer S, Midya V, Lester C, Liao J, Yingst J, Hrabovsky S, Allen SI, Krebs NM, Reinhart L, Evins AE, Horn K, Richie J, Muscat J, Foulds, J. Acceptability of SPECTRUM research cigarettes among participants in trials of reduced nicotine content cigarettes. Tob Reg Sci. 2018;4(1):573–585. doi:10.18001/TRS.4.1.4.

- Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Kunkle N. Evaluation of menthol per se on acute perceptions and behavioral choice of cigarettes differing in nicotine content. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(3):324–331. doi:10.1177/0269881117742660.

- Valentine GW, DeVito EE, Jatlow PI, Gueorguieva R, Sofuoglu M. Acute effects of inhaled menthol on the rewarding effects of intravenous nicotine in smokers. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(9):986–994. doi:10.1177/0269881118773972.

- Higgins ST, Bergeria CL, Davis DR, Streck JM, Villanti AC, Hughes JR, Sigmon SC, Tidey JW, Heil SH, Gaalema DE, Stitzer ML, Priest JS, Skelly JM, Reed DD, Bunn JY, Tromblee MA, Arger CA, Miller ME. Response to reduced nicotine content cigarettes among smokers differing in tobacco dependence severity. Prev Med. 2018;117:15–23. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.04.010.

- Brunette MF, Ferron JC, Geiger P, Villanti AC. Menthol cigarette use in young adult smokers with severe mental illnesses. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(5):691–694. doi:10.1093/ntr/nty064.

- Ahijevych K, Szalacha L, Tan A. Effects of menthol flavor cigarettes or total urinary menthol on biomarkers of nicotine and carcinogenic exposure and behavioral measures. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019; 21(9):1189–1197. doi:10.1093/ntr/nty170.

- Liautaud MM, Leventhal AM, Pang RD. Happiness as a buffer of the association between dependence and acute tobacco abstinence effects in African American smokers. Nic Tobacco Res. 2018;20(10):1215–1222. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntx216.

- Davis DR, Miller ME, Streck JM, Bergeria CL, Sigmon SC, Tidey JW, Heil SH, Gaalema DE, Villanti AC, Stitzer ML, Priest JS, Bunn JY, Skelly JM, Diaz V, Arger CA, Higgins ST. Response to reduced nicotine content in vulnerable populations: effect of menthol status. Tob Regul Sci.2019;5(2):135–142. doi:10.18001/TRS.5.2.5.

- Kosiba JD, Hughes MT, LaRowe LR, Zvolensky MJ, Norton PJ, Smits JAJ, Buckner JD, Ditre JW. Menthol cigarette use and pain reporting among African American adults seeking treatment for smoking cessation. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;27(3):276–282. doi:10.1037/pha0000254.

- Gale N, McEwan M, Eldridge AC, Fearon IM, Sherwood N, Bowen E, McDermott S, Holmes E, Hedge A, Hossack S, Wakenshaw L, Glew J, Camacho OM, Errington G, McAughey J,Murphy J, Liu C, Proctor CJ. Changes in Biomarkers of Exposure on Switching From a Conventional Cigarette to Tobacco Heating Products: A Randomized, Controlled Study in Healthy Japanese Subjects. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(9):1220–1227. doi:10.1093/ntr/nty104.

- Herbeć A, Zatoński M, Zatoński WA, Janik-Koncewicz K, Mons U, Fong GT, Quah ACK, Driezen P, Demjén T, Tountas Y, Trofor AC, Fernández E, McNeill A, Willemsen M, Vardavas CI, Przewoźniak K; EUREST-PLUS consortium. Dependence, plans to quit, quitting self-efficacy and past cessation behaviours among menthol and other flavoured cigarette users in Europe: The EUREST-PLUS ITC Europe Surveys. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2018;16:A19. doi:. doi:10.18332/tid/111356.

- Stroud LR, Vergara-Lopez C, McCallum M, Gaffey AE, Corey A, Niaura R. High rates of menthol cigarette use among pregnant smokers: Preliminary findings and call for future research. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019 Aug 12. pii: ntz142. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntz142.[Epub ahead of print].

- Benowitz NL, Herrera B, Jacob P 3rd. Mentholated cigarette smoking inhibits nicotine metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310(3):1208–1215. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.066902.

- Miller GE, Jarvik ME, Caskey NH, Segerstrom SC, Rosenblatt MR, McCarthy WJ. Cigarette mentholation increases smokers’ exhaled carbon monoxide levels. Exp Clin Psychopharm. 1994;2(2):154–160. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.2.2.154.

- Jarvik ME, Tashkin DP, Caskey NH, McCarthy WJ, Rosenblatt MR. Mentholated cigarettes decrease puff volume of smoke and increase carbon monoxide absorption. Physiol Behav. 1994;56(3):563–570. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(94)90302-6.

- Cubbin C, Soobader MJ, LeClere FB. The intersection of gender and race/ethnicity in smoking behaviors among menthol and non-menthol smokers in the United States. Addiction. 2010;105(Suppl 1):32–8. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03191.x.

- Fagan P, Moolchan ET, Hart A Jr, Rose A, Lawrence D, Shavers VL, Gibson JT. Nicotine dependence and quitting behaviors among menthol and non-menthol smokers with similar consumptive patterns. Addiction. 2010;105(Suppl 1):55–74. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03190.x.

- Fernander A, Rayens MK, Zhang M, Adkins S. Are age of smoking initiation and purchasing patterns associated with menthol smoking? Addiction. 2010;105(Suppl 1):39–45. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03188.x.

- Gandhi KK, Foulds J, Steinberg MB, Lu SE, Williams JM. Lower quit rates among African American and Latino menthol cigarette smokers at a tobacco treatment clinic. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(3):360–367. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01969.x.

- Hyland A, Garten S, Giovino GA, Cummings KM. Mentholated cigarettes and smoking cessation: findings from COMMIT. Tob Control. 2002;11:135–139. doi:10.1136/tc.11.2.135.

- Hymowitz N, Corle D, Royce J, Hartwell T, Corbett K, Orlandi M, Piland N. Smokers’ baseline characteristics in the COMMIT trial. Prev Med. 1995;24(5):503–508. doi:10.1006/pmed.1995.1080.

- Jones MR, Apelberg BJ, Tellez-Plaza M, Samet JM, Navas-Acien A. Menthol cigarettes, race/ethnicity, and biomarkers of tobacco use in U.S. adults: the 1999-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013a;22:224–232. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0912.

- Lawrence D, Rose A, Fagan P, Moolchan ET, Gibson JT, Backinger CL. National patterns and correlates of mentholated cigarette use in the United States. Addiction. 2010;105(Suppl 1):13–31. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03203.x.

- Pletcher MJ, Hulley BJ, Houston T, Kiefe CI, Benowitz N, Sidney S. Menthol cigarettes, smoking cessation, atherosclerosis, and pulmonary function: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1915–1922. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.17.1915.

- Rosenbloom J, Rees VW, Reid K, Wong J, Kinnunen T. A cross-sectional study on tobacco use and dependence among women: does menthol matter? Tob Induc Dis. 2012;10:19. doi:10.1186/1617-9625-10-19.

- Stahre M, Okuyemi KS, Joseph AM, Fu SS. Racial/ethnic differences in menthol cigarette smoking, population quit ratios and utilization of evidence-based tobacco cessation treatments. Addiction. 2010;105(Suppl 1):75–83. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03200.x.

- Curtin GM, Sulsky SI, Van Landingham C, Marano KM, Graves MJ, Ogden MW, Swauger JE. Measures of initiation and progression to increased smoking among current menthol compared to non-menthol cigarette smokers based on data from four U.S. government surveys. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;70(2):446–456. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.08.001.

- Sulsky SI, Fuller WG, Van Landingham C, Ogden MW, Swauger JE, Curtin GM. Evaluating the association between menthol cigarette use and the likelihood of being a former versus current smoker. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;70(1):231-241. Erratum in: Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015 Oct;73(1):114–115. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.06.012.

- Cohn AM, Rose SW, D’Silva J, Villanti AC. Menthol smoking patterns and smoking perceptions among youth: findings from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(4):e107–e116. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.027.

- Emond JA, Soneji S, Brunette MF, Sargent JD. Flavour capsule cigarette use among US adult cigarette smokers. Tob Control. 2018;27(6):650–655. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054198.

- Rath JM, Villanti AC, Williams VF, Richardson A, Pearson JL, Vallone DM. Patterns of longitudinal transitions in menthol use among US young adult smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):839–846. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu247.

- Park SJ, Foreman MG, Demeo DL, Bhatt SP, Hansel NN, Wise RA, Soler X, Bowler RP. Menthol cigarette smoking in the COPDGene cohort: relationship with COPD, comorbidities and CT metrics. Respirology. 2015;20(1):108–114. doi:10.1111/resp.12421.

- Fagan P, Pokhrel P, Herzog TA, Pagano IS, Franke AA, Clanton MS, Alexander LA, Trinidad DR, Sakuma KL, Johnson CA, Moolchan ET. Nicotine metabolism in young adult daily menthol and nonmenthol smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(4):437–446. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv109.

- Jain RB. Trends in serum cotinine concentrations among daily cigarette smokers: data from NHANES 1999-2010. Sci Total Environ. 2014;472:72–77. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.11.002.

- Alexander LA, Crawford T, Mendiondo MS. Occupational status, work-site cessation programs and policies and menthol smoking on quitting behaviors of US smokers. Addiction. 2010;105(Suppl 1):95–104. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03227.x.

- Giovino GA, Villanti AC, Mowery PD, Sevilimedu V, Niaura RS, Vallone DM, Abrams DB. Differential trends in cigarette smoking in the USA: Is menthol slowing progress? Tob Control. 2015;24(1):28–37. Epub 2013 Aug 30. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051159.

- D’Silva J, Boyle RG, Lien R, Rode P, Okuyemi KS. Cessation outcomes among treatmentseeking menthol and nonmenthol smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(5 Suppl 3):S242–S248. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.033.

- Hersey JC, Ng SW, Nonnemaker JM, Mowery P, Thomas KY, Vilsaint MC, Allen JA, Haviland ML. Are menthol cigarettes a starter product for youth? Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(3):403–413. doi:10.1080/14622200600670389.

- Kong G, Singh N, Camenga D, Cavallo D, Krishnan-Sarin S. Menthol cigarette and marijuana use among adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(12):2094–2099. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntt102.

- Reyes-Guzman CM, Pfeiffer RM, Lubin J, Freedman ND, Cleary SD, Levine PH, Caporaso NE. Determinants of light and intermittent smoking in the United States: results from three pooled national health surveys. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(2):228–239. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0028.

- Scheuermann TS, Nollen NL, Cox LS, Reitzel LR, Berg CJ, Guo H, Resnicow K, Ahluwalia JS. Smoking dependence across the levels of cigarette smoking in a multiethnic sample. Addict Behav. 2015;43:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.017.

- Gubner NR, Williams DD, Pagano A, Campbell BK, Guydish J. Menthol cigarette smoking among individuals in treatment for substance use disorders. Addict Behav. 2018;80:135–141. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.015.

- Resnicow K, Zhou Y, Scheuermann TS, Nollen NL, Ahluwalia JS. Unplanned quitting in a triethnic sample of U.S. smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(6):759–765. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntt272.

- Schauer GL, Peters EN, Rosenberry Z, Kim H. Trends in and characteristics of marijuana and menthol cigarette use among current cigarette smokers, 2005-2014. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(3):362–369.

- Nguyen MA, Reitzel LR, Kendzor DE, Businelle MS. Perceived cessation treatment effectiveness, medication preferences, and barriers to quitting among light and moderate/heavy homeless smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;153:341–345. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.039.

- Cohn AM, Ganz O, Dennhardt AA, Murphy JG, Ehlke S, Cha S, Graham AL. Menthol cigarette smoking is associated with greater subjective reward, satisfaction, and “throat hit”, but not greater behavioral economic demand. Addict Behav. 2020;101:106108. Epub 2019(a) Aug 21. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106108.

- Ahijevych K, Parsley LA. Smoke constituent exposure and stage of change in black and white women cigarette smokers. Addict Behav. 1999; 24:115–20. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00031-8.

- Fu SS, Okuyemi KS, Partin MR, et al. Menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation during an aided quit attempt. Nicotine Tob Res 2008;10:457–62. doi:10.1080/14622200801901914.

- Ahijevych K, Ford J. The relationships between menthol cigarette preference and state tobacco control policies on smoking behaviors of young adult smokers in the 2006-07 Tobacco Use Supplements to the Current Population Surveys (TUS CPS). Addiction. 2010;105(Suppl 1):46–54. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03201.x.

- Muscat JE, Liu HP, Stellman SD, Richie JP Jr. Menthol smoking in relation to time to first cigarette and cotinine: results from a community-based study. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2012; 63:166–170. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2012.03.012.

- Hickman NJ 3rd, Delucchi KL, Prochaska JJ. Menthol use among smokers with psychological distress: findings from the 2008 and 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Tob Control. 2014;23:7–13. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050479.

- Reitzel LR, Nguyen N, Cao Y, Vidrine JI, Daza P, Mullen PD, Velasquez MM, Li Y, Cinciripini PM, Cofta-Woerpel L, Wetter DW. Race/ethnicity moderates the effect of prepartum menthol cigarette use on postpartum smoking abstinence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(12):1305–1310. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr095.

- Soulakova JN, Danczak RR. Impact of menthol smoking on nicotine dependence for diverse racial/ethnic groups of daily smokers. Healthcare (Basel). 2017;5(1). pii: E2. doi:10.3390/healthcare5010002.

- Cohn AM, Rose SW, D’Silva J, Villanti AC. Menthol smoking patterns and smoking perceptions among youth: findings from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(4):e107–e116. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.027.

- Sanders E, Weitkunat R, Dempsey R. Menthol cigarettes, time to first cigarette and smoking cessation. Beitrage zur Tabakforschung International. 2017; 27(5): 1–32. doi:10.1515/cttr-2017-0003.

- Holmes LM, Lea Watkins S, Lisha NE, Ling PM. Does experienced discrimination explain patterns of menthol use among young adults? Evidence from the 2014 San Francisco Bay Area Young Adult Health Survey. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54(7):1106–1114. doi:10.1080/10826084.2018.1560468.

- Bover MT, Foulds J, Steinberg MB, Richardson D, Marcella SW. Waking at night to smoke as a marker for tobacco dependence: patient characteristics and relationship to treatment outcome. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:182–190. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01653.x.

- Sidney S, Tekawa IS, Friedman GD, Sadler MC, Tashkin DP. Mentholated cigarette use and lung cancer. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:727–732. doi:10.1001/archinte.1995.00430070081010.

- Brooks DR, Palmer JR, Strom BL, Rosenberg L. Menthol cigarettes and risk of lung cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:609–616. doi:10.1093/aje/kwg182.

- Muscat JE, Richie JP Jr, Stellman SD. Mentholated cigarettes and smoking habits in whites and blacks. Tob Control. 2002;11(4):368–371. doi:10.1136/tc.11.4.368.

- Mustonen TK, Spencer SM, Hoskinson RA, Sachs DP, Garvey AJ. The influence of gender, race, and menthol content on tobacco exposure measures. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7:581–590. doi:10.1080/14622200500185199.

- Muilenburg JL, Legge JS., Jr African American adolescents and menthol cigarettes: smoking behavior among secondary school students. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:570–575. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.017.

- Murray RP, Connett JE, Skeans MA, Tashkin DP. Menthol cigarettes and health risks in Lung Health Study data. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:101–107. doi:10.1080/14622200601078418.

- Mendiondo MS, Alexander LA, Crawford T. Health profile differences for menthol and nonmenthol smokers: findings from the National Health Interview Survey. Addiction. 2010;105(Suppl 1):124–140. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03202.x.

- Blot WJ, Cohen SS, Aldrich M, McLaughlin JK, Hargreaves MK, Signorello LB. Lung cancer risk among smokers of menthol cigarettes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:810–816. doi:10.1093/jnci/djr102.

- Rostron B. Lung cancer mortality risk for U.S. menthol cigarette smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:1140–1144. doi:10.1093/ntr/nts014.

- Jones MR, Apelberg BJ, Samet JM, Navas-Acien A. Smoking, menthol cigarettes, and peripheral artery disease in U.S. adults. Nicotine Tob Res 2013b;15:1183–1189. doi:10.1093/ntr/nts253.

- Rostron B. NNAL exposure by race and menthol cigarette use among U.S. smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:950–956. doi:10.1093/ntr/nts223.

- Ahijevych KL, Wewers ME. Patterns of cigarette consumption and cotinine levels among African American women smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150(5 Pt 1):1229–1233. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.150.5.7952545.

- Giovino GA, Sidney S, Gfroerer JC, O’Malley PM, Allen JA, Richter PA, Cummings KM. Epidemiology of menthol cigarette use. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6 Suppl 1:S67–S81. doi:10.1080/14622203710001649696.

- Wang J, Roethig HJ, Appleton S, Werley M, Muhammad-Kah R, Mendes P. The effect of menthol containing cigarettes on adult smokers’ exposure to nicotine and carbon monoxide. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2010;57(1):24–30. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2009.12.003.

- Benowitz NL, Dains KM, Dempsey D, Wilson M, Jacob P. Racial differences in the relationship between number of cigarettes smoked and nicotine and carcinogen exposure. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(9):772–783. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr072.

- O’Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, Carter LP, Cummings KM. What would menthol smokers do if menthol in cigarettes were banned? Behavioral intentions and simulated demand. Addiction. 2012;107(7):1330–1338. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03822.x.

- Sarkar M, Wang J, Liang Q. Metabolism of nicotine and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-l-(3-pyridyl)-lbutanone (NNK) in menthol and non-menthol cigarette smokers. Drug Metab Lett. 2012;6:198–206. doi:10.2174/1872312811206030007.

- Gan WQ, Estus S, Smith JH. Association between overall and mentholated cigarette smoking with headache in a nationally representative sample. Headache. 2016;56(3):511–518. doi:10.1111/head.12778.

- Munro HM, Tarone RE, Wang TJ, Blot WJ. Menthol and nonmenthol cigarette smoking: allcause deaths, cardiovascular disease deaths, and other causes of death among Blacks and whites. Circulation. 2016;133(19):1861–1866.

- Thihalolipavan S, Jung M, Jasek J, Chamany S. Menthol smokers in large-scale nicotine replacement therapy program. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):e3–4. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302168.

- Azagba S, Minaker LM, Sharaf MF, Hammond D, Manske S. Smoking intensity and intent to continue smoking among menthol and non-menthol adolescent smokers in Canada. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25(9):1093–1099. doi:10.1007/s10552-014-0410-6.

- Shiffman S, Scholl S. Increases in Cigarette Consumption and Decreases in Smoking Intensity When Nondaily Smokers Are Provided With Free Cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(10):1237–1242. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntx221.

- Fetterman JL, Weisbrod RM, Feng B, Bastin R, Tuttle ST, Holbrook M, Baker G, Robertson RM, Conklin DJ, Bhatnagar A, Hamburg NM. Flavorings in Tobacco Products Induce Endothelial Cell Dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38(7):1607–1615.ATVBAHA.118.311156 doi:10.1161/.

- Zatoński M, Herbeć A, Zatoński W, Przewoźniak K, Janik-Koncewicz K, Mons U, Fong GT, Demjén T, Tountas Y, Trofor AC, Fernández E, McNeil A, Willemsen M, Hummel K, Quah ACK, Kyriakos CN, Vardavas CI; EUREST-PLUS consortium. Characterising smokers of menthol and flavoured cigarettes, their attitudes towards tobacco regulation, and the anticipated impact of the Tobacco Products Directive on their smoking and quitting behaviours: The EUREST-PLUS ITC Europe Surveys. Tob Induc Dis. 2018;16:A4. doi:10.18332/tid/96294.8

- Kozlovich S, Chen G, Watson CJW, Blot WJ, Lazarus P. Role of l- and d-Menthol in the Glucuronidation and Detoxification of the Major Lung Carcinogen, NNAL.Drug Metab Dispos. 2019;47(12):1388–1396. doi:10.1124/dmd.119.088351.

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Kim SY, Colby S, Conti D, Giovino GA, Hatsukami D, Hyland A, Krishnan-Sarin S, Niaura R, Perkins KA, Toll BA. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(Suppl 4):S555–S570.

- Jones MR, Tellez-Plaza M, Navas-Acien A. Smoking, menthol cigarettes and all-cause, cancer and cardiovascular mortality: evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013; 8:e77941