Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic created an environment wherein stress and isolation could increase alcohol consumption. The effects of alcohol consumption on Covid-19 susceptibility and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on alcohol use, related harms and services were explored.

Search terms were inputted to Medline and Embase databases, with relevant published papers written in English chosen.

Alcohol ingestion both increased and decreased throughout the population globally, however, the overall trend was an increase. Risk factors for this included female sex, young age, family conflicts, unemployment, mental health disorders, substance misuse and lack of support. Alcohol misuse was found to be an aggravator of domestic violence and worsening mental health. It exacerbated the risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 and worsened the Covid-19 infection severity, with >10 drinks/week increasing the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) risk similarly to established risk factors. This was attributed to the immunosuppressive and disinhibition effects of alcohol. Therefore, healthcare professionals should provide support to vulnerable groups, encouraging stress reduction, healthy habits, limiting alcohol consumption (<5 drinks/week) and promoting coping techniques. Self-help tools that monitor individual alcohol intake and psychosocial interventions in a primary care setting can also be employed. Finally, governing bodies should inform the public of the risks of alcohol ingestion during the Covid-19 pandemic.

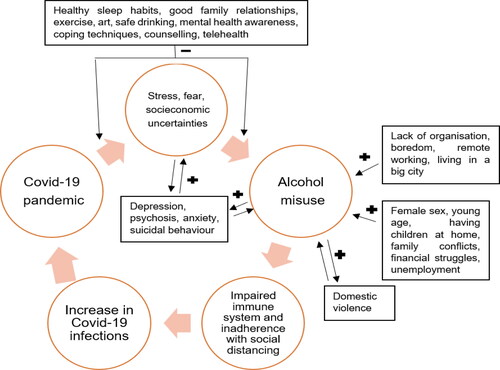

Thus, the Covid-19 pandemic could create a cycle whereby alcohol misuse could become a risk factor for Covid-19 infection and the Covid-19 pandemic could become a risk factor for alcohol misuse. Healthcare professionals should counsel people on alcohol misuse risk and protective factors.

Keywords:

Introduction

On the 11/03/2020 the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the virus Sars-CoV-2 to be responsible for the novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic.Citation1 This pandemic fundamentally changed behaviors both on an individual and societal level, profoundly affecting physical health, mental health and social norms. In such a context, mental health and substance misuse disorders can rise. Notably, substances, such as alcohol, and opioids, can predispose individuals to a Covid-19 infection, as they are immunosuppressive and can negatively affect lung function. Furthermore, substance misuse can coincide with factors that make social distancing impractical, such as residing in overcrowded spaces, lack of permanent accommodation and disinhibition, increasing the likelihood of contracting SARS-CoV-2.Citation2,Citation3

Alcohol specifically is a psychoactive substance that can be dangerous both out-with and within the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, with three million deaths globally attributable to its consumption annually.Citation4 It is commonly ingested, with approximately 2.4 billion people consuming it globally; 1.5 billion male and 0.9 billion female drinkers.Citation5 Alcohol is correlated with communicable and noncommunicable conditions, as it negatively affects the immune system. In higher doses it has been associated with hepatic damage, gastric and pancreatic inflammation and neurodegenerative conditions, such as dementia.Citation3 It can also exacerbate violence, risk-taking behaviors, mental health issues and traumas, both for the drinker, such as alcohol poisoning and the people around them, such as intimate partner violence.Citation4

SARS-CoV-2 is a virus of the Coronavirdae family, which infects the lower respiratory tract. The virus is round with a 31 kb RNA enclosed by a glycoprotein envelope with spike proteins protruding from its surface. A mutation (N501) in the gene that encodes the spike protein, increases viral affinity to human Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptors. SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE-2, fuses with the host cell membrane and enters the cell. It induces a primary and then a secondary cytokine storm, corresponding to the activation of the innate adaptive immune system, respectively. Covid-19 resembles a viral pneumonia and can progress through three sequential phases. A dry cough, fever and myalgia are common phase one symptoms. Then, phase two features a worsening of symptoms, as the adaptive immune system, particularly IgG production, reduces viral replication, whilst concomitantly damaging the alveoli. Phase one and two last approximately two weeks, after which the majority of the population recovers. One third of the population however can progress to phase three, involving severe lung inflammation, acute lung injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and even death.Citation1

Thus, at the start of the pandemic, WHO called upon governments to consider the risks alcohol imposes to the health of the population and restrict its access during lockdown.Citation4 Significantly, the Covid-19 pandemic could create an environment whereby alcohol consumption increased, exacerbating both the risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 and the severity of the Covid-19 infection. This could worsen the pandemic trajectory, propelling people to drink more, creating a vicious cycle.

The primary aims of this review were to establish the impact of alcohol on Covid-19 susceptibility, ascertain changes in alcohol consumption trends globally and assess the correlation between alcohol and associated harms, including domestic violence and mental health. The secondary aims of this review were to determine the impact of the pandemic on alcohol related services and explore options to address problematic drinking during the pandemic.

Methods

This literature review was undertaken from the 2nd of January 2021 until the 20th of March 2021, using a combination of the following search terms: “alcohol,” “alcohol consumption,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “Covid-19,” “immune system,” “domestic violence,” “addiction,” “mental health,” and “telehealth” on the EMBASE and MEDLINE/PubMed databases. Papers were also identified via the reference lists of examined papers. Published papers from 01 January 2019 to 20 March 2021 and papers written in English only were reviewed and chosen according to content relevance. This review complies with the SANRA guidelines.Citation6

Results

Alcohol use and covid-19 susceptibility

Mucociliary clearance, fundamental in maintaining healthy lungs, is impaired by alcohol consumption. Alcohol damages the epithelial lining of the airways and attenuates the response of airway cilia to external stimuli,Citation7 increasing infection susceptibility in a dose and exposure dependent manner.Citation7,Citation8 Additionally, alcohol induces oxidative stress, both by increasing NADPH oxidase, an oxidative stress aggravator, and depleting glutathione, an oxidative stress alleviator. This dysregulates macrophages and damages the antigen presenting process. Alcohol is also associated with reduced granulocyte monocyte colony-stimulating factor production, required for the differentiation of circulating monocytes to active alveolar macrophages. This in turn impairs the macrophages’ ability to release neutrophil chemoattractants, limiting neutrophil recruitment.Citation7

Prolonged alcohol exposure can impair not only the innate but also the adaptive immune system. People diagnosed with alcohol use disorder (AUD) suffer from lymphopenia, modifications in T-cell compartments, reduced mitogen-stimulation response and thus cell division, a compromised type IV hypersensitivity response and diminished interferon-gamma production.Citation7

People who misuse alcohol are more susceptible to viral infections, such as respiratory syncytial virusCitation7 and severe influenza infection.Citation9 Additionally, people with AUD are more likely to develop ARDS, with alcohol misuse independently increasing their risk by 2–4 times.Citation7 Alcohol is also a recognized pneumonia risk factor as it decreases oropharyngeal tone, increasing the likelihood of aspiration. Moderate and heavy alcohol drinkers were 83% more likely to acquire pneumonia, in a dose-dependent manner,Citation10 with alcohol-associated-liver disease (ALD) patients being even more susceptible to pneumonia due to reduced hepatic clearance and splenic function.Citation9 Furthermore, chronic alcohol consumption is associated with higher levels of ACE-2. Even moderate alcohol consumption can elevate ACE-2 for 4 weeks post consumption.Citation5, Citation11 This might be significant as Covid-19 utilizes ACE-2 to enter host cells.

Furthermore, a Danish multi-center cohort clinical trial that recruited 171 Covid-19 positive hospitalized adult patients (not in ICU), explored the alcohol - Covid-19 induced ARDS association. Confounding variables such as age and smoking-status were accounted for. ARDS was reported in 44 (25.7%) participants and severe ARDS in 22 (12.9%). This was significantly associated with higher alcohol consumption, a median of 7 drinks/week for patients that developed ARDS compared to a median of 3 drinks/week for patients that were ARDS-free. Furthermore, alcohol (>10 drinks, 12 g of ethanol/drink per week) was found to increase the risk of ARDS similarly to established risk factors, such as diabetes and immunosuppression.Citation12

The effect of covid-19 on alcohol consumption

During the Covid-19 lockdown numerous factors worked synergistically to increase alcohol consumption, such as lack of distractions provided by non-alcohol-related activities, for example sports,Citation13 with alcohol becoming a coping strategy or a form of entertainment for some.Citation14 Aligned with this, US alcohol sales increased by 55% in the last week of March 2020 compared to the previous year, with a 300% increase in alcohol sales reported by an alcohol E-commerce platform. However, the increase of alcohol consumption at home may have been counterbalanced with the lack of on-premise drinking.Citation13

Anxiety and panic regarding SARS-CoV-2 generated a hazardous myth, whereby consumption of high-strength alcohol can kill the virus. Needless to say not only that is not the case,Citation4 but also alcohol increases the risk of infection, both by impairing the immune system and by causing disinhibition and reduced social distancing.

Two theories have been developed regarding alcohol consumption and Covid-1915:

The interplay between economic difficulties, social isolation and personal anxieties increased alcohol consumption.

The reduced physical availability of alcohol and increased financial burden (loss of employment or additional new alcohol taxes) reduced alcohol use.

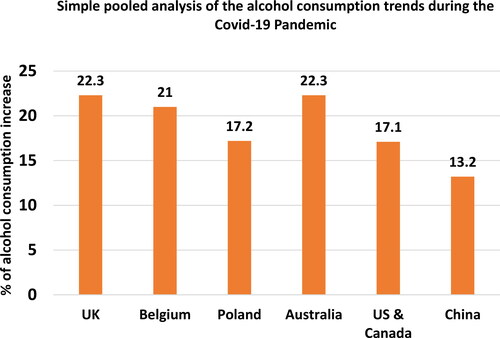

Studies that investigated the effect of Covid-19 on alcohol consumption are summarized in referring to studies undertaken in Europe, USA/Canada and International/other, respectively, with a simple pooled analysis of consumption trends shown in (Appendix 1). Both aforementioned theories were observed with trends of increasing and decreasing alcohol consumption reported. Nonetheless, the predominant trend was a rise in alcohol consumption in approximately 20% of the population. Risk factors for this were excess worry, stress, loneliness, poor mental health, lack of organization, boredom, remote working, female sex, young age, living in a big city and having children at home.

Figure 1. Simple pooled analysis of alcohol consumption globally for studies that reported an increase in consumption (N of people increasing consumption per location/N of people in the studies per location = % increase). Studies excluded: One US studyCitation17 reported a decrease in alcohol use but those individuals who continued drinking were consuming larger quantities. One international studyCitation20 identified an overall reduction in binge drinking. Studies included: UK,Citation26,Citation27 Belgium,Citation24 Poland,Citation23, Citation25 Australia,Citation22 US & Canada,Citation15,Citation16, Citation18,Citation19 China.Citation21

Table 1. Summaries of studies on the effect of Covid-19 on alcohol consumption in the US and Canada.

Table 2. Summaries of studies on the effect of Covid-19 on alcohol consumption in China, Australia and internationally.

Table 3. Summaries of studies on the effect of Covid-19 on alcohol consumption in European countries.

Specifically, most US/Canadian studies reported an increase in alcohol consumption during lockdown,Citation15,Citation16,Citation18,Citation19 by approximately 20%,Citation15,Citation16,Citation18 with two studiesCitation15,Citation16 highlighting that younger people were more prone to hazardous drinking. However, the one studyCitation17 that reported a decrease in both alcohol consumption and binge drinking also reported that the individuals who continued drinking alcohol were consuming larger quantities ().

A Chinese studyCitation21 showed an overall increase in alcohol consumption, including relapses for people who were abstinent before lockdown. Similarly, an Australian studyCitation22 reported that 1 in 5 study participants increased their alcohol consumption, contrasting with the findings of an international studyCitation20 that identified an overall reduction in binge drinking ().

European studies (), highlighted an increase in alcohol consumption in 15%-30% of the surveyed participants.Citation23–27 One Polish studyCitation25 reported a rise in alcohol consumption in 18% of the participants, however 40% of participants reported a decrease, so the overall trend for this study was a reduction in alcohol consumption.

Special considerations; AUD and ALD

The Covid-19 pandemic created a challenging environment for people with AUD, who were unable to connect with support networks, increasing their risk of relapse.Citation13 This was exacerbated by an increase in relapse risk factors, such as depression, fear, anxiety and isolation.Citation28 An Austrian retrospective study recruited 127 people with AUD who were either abstinent from alcohol (n = 37), relapsed (n = 41) or still consuming alcohol (n = 49). Alcohol consumption was quantified using the Alcohol use disorders identification test for consumption (AUDIT-C), with relapsed and alcohol consuming groups consuming hazardous quantities of alcohol (AUDIT-C 11 and 10, respectively). Additionally, 10 participants (7.9%) were at risk of developing Covid-19 related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).Citation28

Furthermore, liver disease is one of the comorbidities increasing vulnerability to Covid-199. Covid-19 contributes to liver decompensation and failure by causing acute liver injury via the induced cytokine storm, direct viral injury, hypoxia and subsequent ischemia. With the incidence of ALD, a consequence of chronic heavy alcohol consumption, increasing,Citation13 it is prudent to monitor Covid-19 positive ALD patients closely for deteriorating liver function. Notably, no original studies to date have been published on this topic, highlighting a current gap in knowledge and an area for future work.

Covid-19, alcohol bans and withdrawal

Globally, during the Covid-19 pandemic, governments implemented numerous alcohol regulations. Canada, New Zealand, the US, the UK and Australia announced outlets for selling alcohol for off-premise consumption as essential services.Citation15, Citation29 Other countries, such as India, South Africa and Thailand, altogether banned alcohol in an attempt to promote self-isolation, compliance with social distancing and limit domestic violence.Citation30,Citation31 This was by no means a panacea; it was associated with alcohol withdrawal, suicidesCitation30 and the perils associated with illegal alcohol procurement, including adulterated or surrogated alcoholic drinks (e.g. poisonous fungus, methanol toxicity).Citation32

Specifically, a study in India recruited 96 male patients with a mean age of 43 years old, hospitalized with severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS), after the alcohol ban was implemented. All patients were heavy alcohol drinkers (mean = 18 Units/day) and 73 of the 96 patients were living below the poverty line. 77 of these patients presented with delirium tremens (DT), 16 with withdrawal seizures and 12 with withdrawal hallucinations. A statistically significant doubling of patients with AWS was demonstrated, from 4 cases/day before the alcohol ban to 8 cases/day after the ban.Citation33

Covid-19, alcohol at home and domestic violence

Reports indicate an increase in domestic violence during the Covid-19 pandemic,Citation34,Citation35 with a rise in calls to child support lines and requirement for police attendance at domestic violence episodes reported.Citation36 Alcohol can increase the risk of the drinker becoming a perpetrator and increase the severity of the misuse,Citation37–39 as perpetrators are violent and abusive regardless of alcohol consumption,Citation40 but without alcohol, abuse might take the form of intimidation, coercion or control.Citation41 Furthermore, there is a higher probability for an individual to be a victim of abuse if one or both of the relationship partners consumes alcohol.Citation41 Victims might also drink before or after the abuse, as a coping or anticipatory strategy, respectively.Citation41 Additionally, the perpetrator can use alcohol as a form of control, if the victim is addicted to it.Citation41 High alcohol consumption at home can also impact children’s perception of alcohol. It can “normalise” hazardous levels of alcohol consumption and promote connotations where alcohol becomes an essential coping strategy.Citation29,Citation42 Thus, alcohol consumption at home can harm both the drinker and household members.

Covid-19 and mental health

Substance misuse, including alcohol, has been related, both during the Covid-19 pandemic and in general, with extreme worry, personal socioeconomic uncertainties, xenophobic attitudes, PTSD symptoms and compulsive checking.Citation15 It is commonly believed that alcohol reduces stress, when in fact, it is a risk factor for this, whilst also exacerbating preexisting mental health disorders.Citation43 This association is most prominent in people with depression, psychosis or anxiety, with some using alcohol to self-medicate.Citation44

Alcohol misuse has also been associated with suicidal behaviour.Citation45 Aggravating factors for alcohol misuse have surfaced during the Covid-19 lockdown, such as family conflicts, financial struggles, and unemployment. The rise in alcohol intake in turn increases feelings of impulsivity, hopelessness, loneliness and aggressiveness, all of which are risk factors for suicide.Citation46

A Chinese online survey that recruited 1074 people identified that 32.1% of the participants reported lower mental well-being, 29% anxiety and 37.1% depression associated with isolation during lockdown. Furthermore, dangerous levels of alcohol consumption were reported in 29.1% and damaging levels in 9.5% of the participants, with alcohol addiction reported in 1.6%. People aged 21-30 years old were more vulnerable to worse mental health and hazardous drinking. Interestingly, there was a small increase in people suffering with alcohol addiction compared to the substantial increase in dangerous and damaging drinking.Citation47 However, behaviors like addiction take time to develop and the complete picture of alcohol addiction due to Covid-19 might not have emerged yet.

Similarly to alcohol, Covid-19 has also been recognized as a creator and aggravator of mental health problems, with two syndromes established; the Covid Stress Syndrome and the Covid Disregard Syndrome. Specifically, Covid Stress syndrome symptoms include Covid-19 associated PTSD and having concerns about touching Covid-19 contaminated objects, about the socioeconomic implications of Covid-19 and about foreigners spreading Covid-19. In contrast, Covid Disregard syndrome symptoms include indifference for social distancing and confidence that Covid-19 is not a threat.Citation15 Due to the association of mental health disorders with alcohol misuse,Citation44, Citation46 these Covid-19 induced syndromes could contribute to a rise in alcohol consumption.

Alcohol services

During the Covid-19 pandemic many outpatient clinics were canceled or patients were unable to attend, due to difficulties in transport or fear of being in a hospital.Citation13 This has been challenging, as a substantial fraction of substance misuse therapies involve group-based therapy and peer support groups. These services adapted to the new restrictions, for example by reducing the number of participants per group and halting provision of therapeutic leaves. To avoid discharging patients with minimal support, additional group-based therapies in an outpatient context were implemented. However, outpatient face-to-face consultations transitioned into telephone consultations, which did not provide an equal level of support.Citation48

Some centers, however, used the Covid-19 pandemic as an opportunity to review practices, with one center updating their thiamin administration protocols to minimize patient transport between hospitals. Additionally, to reduce patient- nursing staff encounters, patients became more autonomous with handling their medication.Citation48 In Kerala, India, where an alcohol ban was imposed, a more controversial approach was adopted in revising alcohol services, whereby doctors prescribed alcohol to people with alcohol addiction, to reduce the number of associated suicides.Citation31

Addressing problematic drinking and patient counseling

There is an established association between stress and alcohol consumption.Citation49 Strategies to promote healthy living and reduce stress in an attempt to reduce alcohol use can be promoted, such as healthy sleep habits, limiting alcohol consumption (<5 drinks/week), improving family relationships and encouraging exercise and art.Citation19 Services can be provided to vulnerable groups at risk of alcohol misuse, including self-help tools that monitor individual alcohol intake, regular mental health screening toolsCitation46 and counseling in a primary care setting.Citation50 Specifically, dialectic behavioral therapy (DBT), a psychosocial intervention that is based on the combined principles of behavioral and cognitive restructuring and acceptance strategies, may improve alcohol-related outcomes, namely promote abstinence and reduce alcohol consumption. When DBT was delivered online, outcomes remained favourable.Citation51 Likewise, cognitive behavioral therapy, a psychosocial intervention that aims to alter negative thinking and behaviors, improve emotional control and encourage use of coping techniques, may reduce alcohol consumption in adolescents.Citation51 Brief interventions that have been shown to reduce alcohol consumption can also be employed.Citation50 These are based on providing: (1) feedback on the patient’s alcohol intake and quantifying safe alcohol limits, (2) information on alcohol related harms, (3) information on the advantages of decreasing alcohol intake, (4) tailored advice, (5) coping strategies and (6) a personalized alcohol reduction plan.Citation50 Furthermore, at a local and national level, governing bodies should monitor alcohol consumption and inform the public of the additional risks of alcohol consumption during the Covid-19 pandemic.Citation46

Telehealth can be employed to provide counseling, support and reassurance.Citation49,Citation52,Citation53 Moreover, digital interventions have been successful in the context of problematic drinking and have been shown to reduce alcohol consumption by 3 UK standard drink units (23 g) per week, whilst having no difference in effectiveness compared to face-to-face interventions.Citation54 In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, they enable healthcare providers to safely stay in contact with patients, allowing for unrestricted diagnosis, treatment and follow-ups via interviewing. It might also be a more accessible option for a subgroup of patients, who would not feel comfortable to attend substance misuse clinics, due to fear of being stigmatised.Citation46,Citation55 Frequent telehealth appointments might be needed for high-risk patients and proactive follow-up appointments for previously stable and abstinent patients.Citation13 When face-to-face appointments are necessary, screening questionnaires can be used prior, to assess whether a patient has Covid-19 symptoms.Citation48

Crucially, older adults and people with limited access to the internet must not be marginalized and ignored. Unfamiliarity with technology should not be allowed to contribute to healthcare inequalities. These considerations apply to practitioners too, who should be trained adequately to provide an equivalent standard of care as face-to-face consultations. Finally, organizations should be willing to invest in technology that will make telehealth feasible, whilst protecting patient confidentiality. Treatment options and relevant protocols should be adapted to allow for standardization of service provision via tele-health to allow care to be provided with equity, regardless of age and socioeconomic status.Citation56

Discussion

This review has several limitations. Firstly, most studies that comprised the primary analysis of this narrative review were online surveys, limiting the sample pool to participants with internet access and necessary literacy skills, introducing potential selection bias. Additionally, a limited number of databases were searched and a restricted number of eligible studies available, due to the novel nature of the topic. Furthermore, the term “domestic violence” was utilized as a search term rather than the thread “intimate partner violence” OR “domestic violence,” possibly omitting relevant studies. A further limitation of this study was the absence of confounding factor analysis, due to the lack of reporting in the primary literature.

Overall, alcohol negatively impacts mental and physical health, regardless of the Covid-19 pandemic. The pandemic itself has also affected the physical and mental well-being of people throughout the globe. However, the synergistic effect of the two has had by far the worst effect. Alcohol misuse exacerbates both the risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 and the Covid-19 infection severity, with >10 drinks/week found to increase the risk of ARDS similarly to established risk factors. This is likely due to the immunosuppressive and disinhibition effects of alcohol. Furthermore, the Covid-19 pandemic has brought to light risk factors associated with increased alcohol consumption, namely stress, boredom, female sex, young age, having children at home, family conflicts, unemployment, preexisting mental health disorders and substance misuse. Importantly, both an increase and decrease of alcohol consumption was observed globally, with a variety of trends reported ().

Thus, the Covid-19 pandemic could create a vicious cycle (Appendix 2, ) for people who increased their alcohol use, whereby alcohol misuse could become a risk factor for Covid-19 infection and the Covid-19 pandemic could become a risk factor for alcohol misuse. Therefore, now it is more important than ever for healthcare professionals in a community setting to reach out to patients and provide tailored support focused on stress reduction, healthy habits and coping techniques to counterbalance the alcohol misuse associated risk factors.

Figure 2. Interplay of the Covid-19 pandemic, alcohol misuse and Covid-19 infections, with alcohol misuse aggravating and alleviating factors presented. The Covid-19 pandemic created an environment wherein stress, fear and isolation could lead to alcohol misuse. Protective factors for this include healthy sleep habits, limiting alcohol consumption, good family relationships, exercising, art and counseling. Alcohol misuse, which could be aggravated by mental health disorders, domestic violence, and personal life circumstances, could increase Covid-19 susceptibility by impairing the immune system and promoting nonadherence with social distancing. This might contribute to a rise in Covid-19 cases and thus the spread of the pandemic.

Acknowledgments

The author submitted a version of the manuscript after completion to a competition by The Medical Council on Alcohol (MCA) and received a cash prize for the work.

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. The author declares that no funds, grants, or other support was received during the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Upadhyay J, Tiwari N, Ansari MN. Role of inflammatory markers in corona virus disease (COVID-19) patients: a review. Exp Biol Med (Maywood)). 2020;245(15):1368–75.

- Baillargeon J, Plychronopoulou E, Kuo YF, Raji M. The impact of substance use disorder on COVID-19 outcomes. Psychiatric Service. 2020;72(5):578–581.

- Wei Y, Shah R. Substance use disorder in the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of vulnerabilities and complications. Pharmaceuticals. 2020;13(7):155. doi:10.3390/ph13070155.

- WHO. Alcohol does not protect against COVID-19; access should be restricted during lockdown. 2020. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/alcohol-use/news/news/2020/04/alcohol-does-not-protect-against-covid-19-access-should-be-restricted-during-lockdown. Last accessed: 20/03/21

- Testino G. Are Patients with alcohol use disorders at increased risk for Covid-19 Infection? Alcohol Alcohol. 2020;55(4):344–6.

- Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S. SANRA—a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2019;4(5):5.

- Simet SM, Sisson JH. Alcohol’s effects on lung health and immunity. Alcohol Res. 2015;37(2):199–208.

- Sisson JH. Alcohol and airways function in health and disease. Alcohol. 2007;41(5):293–307. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.06.003.

- Testino G, Pellicano R. Alcohol consumption in the COVID-19 era. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2020;66(2):90–2.

- Simou E, Britton J, Leonardi-Bee J. Alcohol and the risk of pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8):e022344. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022344.

- Okuno F, Arai M, Ishii H, Shigeta Y, Ebihara Y, Takagi S, Tsuchiya M. Mild but prolonged elevation of serum angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) activity in alcoholics. Alcohol. 1986;3(6):357–9.

- Lassen MCH, Skaarup KG, Sengeløv M, Iversen K, Ulrik CS, Jensen JUS, et al. Alcohol consumption and the risk of acute respiratory distress Syndrome in COVID-19. Annals American Thoracic Soc. 2020;18(6).

- Da BL, Im GY, Schiano TD. Coronavirus disease 2019 hangover: a rising tide of alcohol use disorder and alcohol‐associated liver disease. Hepatology. 2020;72(3):1102–8.

- Gonçalves PD, Moura HF, do Amaral RA, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Malbergier A. Alcohol Use and COVID-19: can we predict the impact of the pandemic on alcohol use based on the previous crises in the 21st century? A brief review. Front Psychiatr. 2020;11:581113. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.581113.

- Taylor S, Paluszek MM, Rachor GS, McKay D, Asmundson GJG. Substance use and abuse, COVID-19-related distress, and disregard for social distancing: a network analysis. Addict Behav . 2021;114:106754. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106754.

- Nanos. Boredom and stress drives increased alcohol consumption during COVID-19: NANOS poll summary report. 2020. Available at: https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2020-06/CCSA-NANOS-Increased-Alcohol-Consumption-During-COVID-19-Report-2020-en_0.pdf. Last accessed: 2021 Mar 20.

- Boschuetz N, Cheng S, Mei L, Loy VM. Changes in alcohol use patterns in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. Wisconsin Medical J. 2020;119(3):171–6.

- Killgore WDS, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, Lucas DA, Dailey NS. Alcohol dependence during COVID-19 lockdowns. Psychiatr Res. 2021;296:113676.

- Robillard R, Saad M, Edwards J, Solomonova E, Pennestri M-H, Daros A, Veissière SPL, Quilty L, Dion K, Nixon A, et al. Social, financial and psychological stress during an emerging pandemic: observations from a population survey in the acute phase of COVID-19. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e043805. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043805.

- Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, Bouaziz B, Bentlage E, How D, Ahmed M, On Behalf of the ECLB-COVID19 Consortium, et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1583. doi:10.3390/nu12061583.

- Sun Y, Li Y, Bao Y, Meng S, Sun Y, Schumann G, Kosten T, Strang J, Lu L, Shi J, et al. Brief report: increased addictive internet and substance use behavior during the COVID‐19 pandemic in China. Am J Addict. 2020;29(4):268–70.

- Stanton R, To QG, Khalesi S, Williams SL, Alley SJ, Thwaite TL, Fenning AS, Vandelanotte C. Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in australian adults. IJERPH. 2020;17(11):4065. doi:10.3390/ijerph17114065.

- Sidor A, Rzymski P. Dietary choices and habits during COVID-19 lockdown: experience from Poland. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1657. doi:10.3390/nu12061657.

- Vanderbruggen N, Matthys F, Van Laere S, Zeeuws D, Santermans L, Van den Ameele S, Crunelle CL. Self-reported alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use during COVID-19 lockdown measures: results from a web-based survey. Eur Addict Res. 2020;26(6):309–15. doi:10.1159/000510822.

- Szajnoga D, Klimek-Tulwin M, Piekut A. COVID-19 lockdown leads to changes in alcohol consumption patterns: results from the polish national survey. J Addict Dis. 2021;39(2):215–225.

- Jacob L, Smith L, Armstrong NC, Yakkundi A, Barnett Y, Butler L, McDermott DT, Koyanagi A, Shin JI, Meyer J, et al. Alcohol use and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown: a cross-sectional study in a sample of UK adults. Drug Alcohol Depend . 2021;219:108488. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108488.

- Robinson E, Gillespie S, Jones A. Weight-related lifestyle behaviours and the COVID-19 crisis: an online survey study of UK adults during social lockdown . Obes Sci Pract. 2020;6(6):735–40. doi:10.1002/osp4.442.

- Yazdi K, Fuchs-Leitner I, Rosenleitner J, Gerstgrasser NW. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with alcohol use disorder and associated risk factors for relapse. Front Psychiatr. 2020;11:620612.

- Reynolds J, Wilkinson C. Accessibility of ‘essential’ alcohol in the time of COVID‐19: casting light on the blind spots of licensing? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39(4):305–8.

- Nadkarni A, Kapoor A, Pathare S. COVID-19 and forced alcohol abstinence in India: the dilemmas around ethics and rights. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2020;71:101579. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2020.101579.

- Varma RP. Alcohol withdrawal management during the Covid-19 lockdown in Kerala. Indian J Med Ethics. 2020; V(2):105–6.

- Balhara YPS, Singh S, Narang P. Effect of lockdown following COVID‐19 pandemic on alcohol use and help‐seeking behavior: observations and insights from a sample of alcohol use disorder patients under treatment from a tertiary care center. Psychiat Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(8):440–1.

- Narasimha VL, Shukla L, Mukherjee D, Menon J, Huddar S, Panda UK, Mahadevan J, Kandasamy A, Chand PK, Benegal V, et al. Complicated alcohol withdrawal: an unintended consequence of COVID-19 lockdown. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2020;55(4):350–3. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agaa042.

- Bright CF, Burton C, Kosky M. Considerations of the impacts of COVID-19 on domestic violence in the United States. Soc Sci Humanit Open. 2020;2(1):100069. doi:10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100069.

- Roesch E, Amin A, Gupta J, García-Moreno C. Violence against women during covid-19 pandemic restrictions. BMJ. 2020;369:m1712. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1712.

- Green P. Risks to children and young people during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;369:m1669. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1669.

- Parrott DJ, Giancola PR. A further examination of the relation between trait anger and alcohol-related aggression: the role of anger control. Alcoholism Clin Experi Res. 2004;28(6):855–64. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000128226.92708.21.

- Leonard KE, Quigley BM. Thirty years of research show alcohol to be a cause of intimate partner violence: future research needs to identify who to treat and how to treat them. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017;36(1):7–9.

- Wilson IM, Graham K, Laslett A-M, Taft A. Relationship trajectories of women experiencing alcohol-related intimate partner violence: a grounded-theory analysis of women’s voices. Soc Sci Med. 2020;264(113307):113307.

- Laslett A-M, Jiang H, Room R. Alcohol’s involvement in an array of harms to intimate partners. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017;36(1):72–9. doi:10.1111/dar.12435.

- Fox S, Galvani S. Briefing: alcohol and domestic abuse in the context of Covid-19 restrictions. 2020. Available at: https://www.mmu.ac.uk/media/mmuacuk/content/documents/rcass/Briefing-on-alcohol-and-domestic-abuse-in-context-of-Covid-19-1st-April-2020.pdf. Last accessed: 20/03/21

- Rehm J, Kilian C, Ferreira‐Borges C, Jernigan D, Monteiro M, Parry CDH, Sanchez ZM, Manthey J. Alcohol use in times of the COVID 19: implications for monitoring and policy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39(4):301–4. doi:10.1111/dar.13074.

- WHO. Alcohol and COVID-19: what you need to know. 2020. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/437608/Alcohol-and-COVID-19-what-you-need-to-know.pdf [accessed 2021 Mar 03].

- Puddephatt J, Jones A, Gage SH, Fear NT, Field M, McManus S, et al. Associations of alcohol use, mental health and socioeconomic status in England: findings from a representative population survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;219:108463.

- Kaplan MS, Huguet N, McFarland BH, Caetano R, Conner KR, Giesbrecht N, Nolte KB. Use of alcohol before suicide in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(8):588–92.e2.

- Wasserman D, Iosue M, Wuestefeld A, Carli V. Adaptation of evidence‐based suicide prevention strategies during and after the COVID‐19 pandemic. World Psychiatr. 2020;19(3):294–306. doi:10.1002/wps.20801.

- Ahmed MZ, Ahmed O, Aibao Z, Hanbin S, Siyu L, Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102092. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092.

- Columb D, Hussain R, O’Gara C. Addiction psychiatry and COVID-19: impact on patients and service provision. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37(3):164–8. doi:10.1017/ipm.2020.47.

- Anthenelli R, Grandison L. Effects of stress on alcohol consumption. Alcohol Res. 2012;34(4):381–2.

- Kaner EF, Beyer FR, Muirhead C, Campbell F, Pienaar ED, Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Saunders JB, Burnand B, Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2(2):CD004148.

- Hurzeler T, Giannopoulos V, Uribe G, Louie E, Haber P, Morley KC. Psychosocial interventions for reducing suicidal behaviour and alcohol consumption in patients with alcohol problems: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Alcohol Alcohol. 2021;56(1):17–27.

- Rehm J, Anderson P, Manthey J, Shield KD, Struzzo P, Wojnar M, Gual A. Alcohol use disorders in primary health care: what do we know and where do we go? Alcohol Alcohol. 2016;51(4):422–7.

- Melamed OC, Hauck TS, Buckley L, Selby P, Mulsant BH. COVID-19 and persons with substance use disorders: inequities and mitigation strategies. Subst Abus. 2020;41(3):286–91.

- Kaner EF, Beyer FR, Garnett C, Crane D, Brown J, Muirhead C, Redmore J, O’Donnell A, Newham JJ, de Vocht F, et al, Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group. Personalised digital interventions for reducing hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in community-dwelling populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9(9):CD011479. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011479.pub2.

- Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Link B, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin D. Stigma and treatment for alcohol disorders in the United States. American JEpidemiol. 2010;172(12):1364–72. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq304.

- Rosen D. Increasing participation in a substance misuse programs: lessons learned for implementing telehealth solutions during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American J Geriatric Psychiatr. 2021;29(1):24–6. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2020.10.004.