Abstract

This editorial paper introduces the relevance of trust in educational settings. It discusses interdisciplinary approaches to trust, reflects upon the relationships between trust and education and how trust has so far been studied in educational research. In addition, a comprehensive model of trust is introduced as a framework for the individual papers of this special issue that altogether, through different disciplinary and methodological lenses, investigate trust in various realms of education in five European countries.

Why a Special Issue on “Trust in Educational Settings”?

In this special issue, authors from several European countries analyze trust in different educational settings. Trust is a subject that concerns everyone and that has become an object of public debate as well as scientific research. Democratic values and social cohesion are reported to be at stake in countries across Europe and within some European countries (European Commission, Citation2017). Trust is considered a key factor for developing and maintaining social cohesion (Delhey et al., Citation2018; Lancee, Citation2017). Education is seen as pivotal for the development of generalized trust, (Rothstein & Uslaner, Citation2005, p. 47) and for the reproduction of democratic values (Honneth, Citation2012). With regard to its societal functions and preconditions, trust is thus closely interconnected with education. At the same time, social relations in education are, for instance, coming under pressure because of increases in social inequality or ethnic diversity, as well as the generally high importance of education as a means of maintaining or advancing the social status. However, trust can help to build positive relationships that benefit those involved in educational contexts.

As a particular quality of such relations, trust requires closer inspection with regard to its preconditions, implications and consequences, especially because it is a multi-layered construct tackled within many disciplines. This introductory paper seeks to outline the many approaches to trust. It explains how trust has been referred to in education through a historic-systematic lens. To acknowledge the complexity of trust, the paper points out the many notions of and approaches to trust, and discusses how they are referred to in educational research. Furthermore, a comprehensive model of trust in education will be introduced that explains the interconnections of trust within and among educational settings (Niedlich et al., Citation2021). This model will serve as a framework in which the papers of this special issue will be placed. Finally, the papers contributed by colleagues from Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, and Germany will be introduced.

Trust in Education—A Brief Historic-Systematic Overview

Trust has played a role in education for a long time and in many different ways, but the way trust is framed has changed considerably over time (Bormann, Citation2014; Frevert, Citation2013). In the 19th century, a shift away from transcendental principles took place. Human beings were understood to be equipped with special abilities, but also to be in need of education. Following this, social trust began to play a greater role in both society and education. Over the course of the twentieth century, perspectives on trust and reasons for trust became more objective and de-emotionalized (Frevert, Citation2013). More specifically and with regard to education (Bormann, Citation2014), several stages of transformation during this period can be recognized. Whereas in earlier times interpersonal trust was implicitly treated as a fundamental source for legitimizing pedagogical authority for the purpose of enhancing individual growth, over time a more distanced view of trust in institutionalized educational settings emerged, with the focus shifting to the role-based character of the interaction between students and educators.

This last stage of the development was driven by the emergence of increasingly complex societies marked by multiple dependencies on experts, societal and political institutions (Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, Citation2001; Giddens, Citation1995). This development is discussed critically in terms of an erosion of certainties, increasing frustration, fears, and a growing distance between people and institutions, political disenchantment as well as a general decline in social cohesion (Eder & Katsanidou, Citation2014). The intensified multidisciplinary debate about the role of trust in these developments also spilled over into educational science. Particularly after the realistic and empirical turn in educational science (Roth, Citation1963) and the systematic consideration of the prerequisites and consequences of institutionally embedded education, a general shift toward a politicization of research knowledge in terms of evidence-based decision-making took place (Weiss, Citation1979). The last two decades of the twentieth century saw a rise of accountability in general and in education in particular (Ball, Citation2010). This led to a more depersonalized view of trust and a shift in trust toward instruments for monitoring and controlling educational achievement and institutional performance (Ball, Citation2010, p. 114ff.; Bormann & John, Citation2014).

In today's research, perspectives on trust in educational settings are remarkably diverse. They include a focus on different formal and informal educational realms, from elementary education to higher education and educational governance as well as different academic disciplines, ranging from educational research (including both empirical research and, rarely, the philosophy and theory of education (D’Olimpio, Citation2018) via social or educational psychology to sociology and further neighboring disciplines (Allan & Persson, Citation2020; Borgonovi & Burns, Citation2015; Sawinski, Citation2014; Schoon et al., Citation2010; for more information: Niedlich et al., Citation2021). The contributors in this special issue represent a good portion of this diversity.

Trust and Why It Matters in Education

The following section will—as far as space permits—provide an overview on different notions of and approaches to trust. It is worth mentioning that this discussion is based on findings across several neighboring academic disciplines. They reveal a wealth of terms and concepts that, for the most part, education research has yet to make use of.

What Is Trust?

In this paper, trust is understood as the willingness of an individual or a group to be vulnerable to another party—whether it is another person or an institution—whose behavior is not entirely controllable or predictable. Trust relies on generalizations drawn from past experiences which lead to the belief that the partner in the interaction will not do harm and the belief that tacit mutual expectations will be respected in accordance with shared norms and values.Footnote1

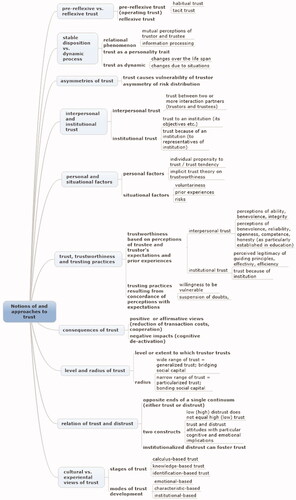

provides an overview of the different notions of and approaches to trust which are described in more detail in the following. The concepts found in the interdisciplinary literature address different aspects of trust between which relationships can be established, even if these are often not explicitly mentioned. The order in which these aspects are presented is not arbitrary, but it is also not mandatory.

Pre-Reflexive Vs. Reflexive Trust

In general, people are not aware they are trusting someone or something—in other words people trust tacitly. If they begin to reflect upon their trust, this often leads to a shift into reflexive trust insofar as it may create doubt whether the trust previously granted was justified (Endreß, Citation2010; Gambetta, Citation2000, p. 234). With regard to its working modus, Endreß (Citation2010) distinguishes pre-reflexive and reflexive trust. The tacit form of pre-reflexive trust underlies everyday actions (also “operating trust,” Endreß, Citation2010, p. 97; Endreß, Citation2014). “Habitual trust” as another form of pre-reflexive trust is a result of repeated social actions turning into routines (Endreß, Citation2010, p. 100). In contrast, reflexive trust relates more closely to cognition-based trust, which occurs from the assessment of dangers and the calculation of risks that are entered into trust actions (Endreß, Citation2010, p. 94). Similarly, McAllister (Citation1995) distinguishes between cognition-based trust, which is based on beliefs about reliability, predictability and dependability, and affect-based trust, which relies on the mutual care and concern of the partners in the interaction (McAllister, Citation1995, p. 25) and on the quality of the relationship that has developed (van Knippenberg, Citation2018).

Stable Disposition Vs. Dynamic Process

On the one hand, trust has been defined as a personality trait learned in early childhood that results in a relatively stable disposition (Rotter, Citation1980; Rousseau et al., Citation1998). On the other hand, trust has been conceptualized as a process (Möllering, Citation2013). Following the latter perspective, trust is considered as dynamic in that it is based on the experiences made in life (Abdelzadeh & Lundberg, Citation2017; Flanagan & Stout, Citation2010; Glanville & Paxton, Citation2007) and on the features of the specific situation and the partners in the interaction (Schweer & Thies, Citation2008).

Asymmetries of Trust

Although often referred to in an affirmative manner, trust is not necessarily associated with harmonious relations or the absence of hazards. In general, individuals who trust make themselves vulnerable (Misztal, Citation2011) because they cannot control the behavior of the individual or institution that is trusted. By choosing to trust they accept the risk that the subject of their trust may violate their expectation of being treated fairly and reasonably. That is to say that trust relationships are considered to be reciprocal, but the threat associated with broken trust is asymmetrically distributed between the partners in the interaction: the person who trusts takes the risk that his/her trust will be abused by its subject. In addition, “(un)reciprocated trust,” as Pillutla et al. (Citation2003, p. 448) put it, “can seriously damage a relationship and its prospects.”

Interpersonal and Institutional Trust

Many of the aspects explained here apply to both interpersonal and institutional trust. Interpersonal trust is a characteristic of a relationship between two or more individuals in which mutual expectations and assessments of perceived characteristics are processed. Zucker (Citation1986) speaks of characteristic-based trust, which relies on the perception and evaluation of the characteristics of a partner in the interaction. When it comes to institutional trust, it is necessary to distinguish two sub-types of trust: Trust toward institutions relies on the perceived effectiveness andefficiency of the institutional order to accomplish the guiding principles of an institution (Lepsius, Citation2017). According to Zucker, such trust depends on the features of an institution which ensure that their representatives can be trusted (Zucker, Citation1986, p. 53). Trust because of institutions refers to trust people have against “the background of institutional safeguards influencing their decision making and actions” (Bachmann, Citation2018, p. 219; Zucker, Citation1986, p. 61). The latter is similar to what Kramer labels role-based or rule-based trust, i.e. depersonalized modes of trust relying on the tacitly processed information about the institutional role of the subject of the trust and the shared rules of appropriate action (Kramer, Citation1999, p. 578).

Personal and Situational Factors

Put simply, the repeated mutual positive experiences an individual has with partners in an interaction—be it individuals or institutions—are a precondition of trust. More specifically, in line with the differential theory of trust (Bormann & Thies, Citation2019; Schweer, Citation1997; Schweer & Thies, Citation2008), the preconditions of trust include personal and situational factors. One personal factor is the trusting party's propensity to trust (also called “individual trust tendency”), which denotes the conviction and willingness to trust others established over the life span (Alarcon et al., Citation2017; Frazier et al., Citation2013; Schweer, Citation1997). Another personal factor is the implicit theory of trust, in other words the trusting party’s expectations concerning the trustworthiness of the other party. These personal factors not only interact with each other but also with the conditions of the situation in which the interaction takes place. Situational factors that are critical to the development of trust include, for instance, voluntariness (e.g., do the partners in the interaction have any choice at all but to trust?), prior experiences (e.g., have the partners in the interaction already had experience of each other or are they familiar with comparable situations?) and perceived risks (what is at stake for the trusting party?; Schweer, Citation1997).

Trust, Trustworthiness, and Trusting Practices

Trust analytically differs from trustworthiness and both differ from trusting practices. Trust, as explained, arises from the complex interplay of beliefs, expectations, experiences and situational aspects. The willingness to subject oneself to another’s actions relies on the perception of the trustworthiness of the subject of the trust. Perceived trustworthiness can lead to trusting practices on the part of the trusting party, i.e. behavior that is based on trust (Alarcon et al., Citation2017, p. 1; Colquitt et al., Citation2007, p. 909; Bormann & Thies, Citation2019). Trust theory has identified different facets of trust that are crucial for perceived trustworthiness: “ability,” “benevolence,” and “integrity” (Mayer et al., Citation1995; Schoorman et al., Citation2007).

Consequences of Trust

The majority of references to trust that can be found in the literature tend to be affirmative, emphasizing advantages of trust such as the reduction of transaction costs or increased and eased cooperation (Bouckaert & Van de Walle, Citation2003; Gambetta, Citation2000). However, some scholars point out negative consequences of trust that lie in what might be called a tendency to cognitive de-activation. For example, Bromme and Kienhues distinguish “plausibility heuristics” and “trust heuristics,” with the latter resulting in a tendency to suspend elaboration, i.e. the attempt to control or to find out more about the intentions or actions of the other party (Bromme & Kienhues, Citation2014).

The Level of Trust, Generalized and Particularized Trust

Recent research has emphasized the need to distinguish the level of trust from the radius of trust (Delhey et al., Citation2011; van Hoorn, Citation2014). Whereas the level of trust displays low or high trust (see also vi), the radius of trust describes the “width of the circle of people among whom a certain trust level exists, which can be broad or narrow” and “determines with whom individuals are willing to cooperate” (van Hoorn, Citation2014, p. 1256). A narrow radius of trust is associated with trust in in-groups and labeled “particularized trust.” Accordingly, trust that includes members of out-groups is associated with a wide radius of trust and is associated with generalized trust (Rothstein & Uslaner, Citation2005, p. 45; van Hoorn, Citation2014). Whereas trust to in-groups rests on “bonding social capital,” out-group trust involves “bridging social capital” that fosters interactions with a wide range of people. It is therefore of particular importance for social cohesion (Christoforou & Davis, Citation2014).

The Relation of Trust and Distrust

In general people believe there can be either trust or distrust in a specific party. However, social relationships are marked by multiplexity and inconsistency (Lewicki et al., Citation1998, pp. 442, 443). They include a range of different, even contradictory characteristics that can cause both trust and distrust at the same time: for example, we can trust another individual as being competent and reliable, but not benevolent. Instead of considering trust and distrust as opposite ends of the same continuum (as, e.g., Rotter, Citation1980 did), trust and distrust have been conceptualized as separate dimensions that can occur simultaneously because they refer to different aspects of a social relationship (Lewicki et al., Citation1998, p. 440). In the same way, Van de Walle and Six (Citation2014) suggest that the opposite of trust is not just the “absence of distrust” (and vice versa; Van de Walle & Six, Citation2014, p. 162). Instead they consider trust and distrust as being connected with different emotions, with trust based on calm and security and distrust based on fear and worry (Van de Walle & Six, Citation2014, p. 168). Even trusting relationships can be accompanied by suspicion, for example when individuals come to interact with each other in unfamiliar situations. Distrust is not necessarily a flaw, because it can cause reflection and protect the trusting party from disappointment (Lepsius, Citation2017, p. 81). Distrust is thus mainly based on cognition (Kramer, Citation1999, p. 587) but also impacts affections. In a similar vein, trust is said to develop on the basis of cognition before affect-based trust can be developed (Lewicki & Bunker, Citation1996). Accordingly trust and distrust differ in terms of the focus of the cognition and the quality of affects (for a critical review of this conceptualisation: Legood et al., Citation2022).

Cultural Vs. Experiential Perspective

As already indicated with regard to the dynamics of trust, time is crucial for establishing trust because it relies on repeated interactions which lead to beliefs and expectations underlying trusting behavior. Previous experiences thus have an effect on the present and at the same time set the course for the development of a relationship in the future (Korsgaard et al., Citation2018; Luhmann, Citation2000). When it comes to the stability or dynamic nature of trust, two perspectives can be distinguished. One is the “cultural perspective of trust,” which holds that trust is a relatively stable disposition learned in early years and maintained later on in life. The “experiential perspective of trust” suggests that trust is dynamic as it develops across a life span and in different situations. Empirical studies provide support for both views (Abdelzadeh & Lundberg, Citation2017, p. 208; Lewicki et al., Citation2006).

In differentiating the cognitive efforts related to trust, Lewicki and Bunker (Citation1996) have established a three-stage model of trust development. According to the model, reaching one level is a prerequisite for moving on to the next level, with each having its own dynamics. Accordingly, in situations where little is known about the partner in the interaction, the development of trust is initially based on calculation, as the partners in the interaction ponder whether the risk of trusting is worth taking. Secondly, knowledge-based trust by contrast relies on experience and routines, i.e. informed perceptions. Thirdly, identification-based trust develops from mutual appreciation of intentions and desires (Lewicki & Bunker, Citation1996, p. 119–124).

Views of Relationships Between Trust and Education

The previous section explained the wide spectrum of approaches to trust, as they have been elaborated in various neighboring disciplines. Next we consider the extent to which these approaches also play a role in research into trust into education.

First of all, as in neighboring disciplines education research conceives of trust as a relational phenomenon that evolves dynamically. It is based on mutual perceptions that are subject to information processing and social categorization resulting in perceived trustworthiness, which can serve as a basis of trusting practices (Alarcon et al., Citation2017; Schweer et al., Citation2013, p. 93; Bormann & Thies, Citation2019). Rather than referring to the seminal works of Mayer et al. (Citation1995), education research often refers to five facets of trust: benevolence, reliability, openness, competence and honesty (Hoy & Tschannen-Moran, Citation1999; Janssen et al., Citation2012; Shayo et al., Citation2021; Bormann et al., Citation2019; see also Bormann et al., Citationin this special issue).

In education, trust is often—more or less explicitly—treated as a psychological disposition and a social attitude that is reflexively accessible to individuals. However, the interaction of both personal and situational characteristics in the development of trust is also discussed in education research. One example is the “differential theory of trust” (Schweer, Citation1997), which also highlights the pre-reflexive mode of trust regarding the concept of the “implicit theory of trust” as one of the personal factors relevant for the development of trust. Although the development of trust is conceptually reflected, the concrete stages of the development of trust are hardly ever a topic for empirical studies, which is also reflected in the lack of longitudinal or comparative trust studies that examine how and under what conditions trust develops.

Nonetheless, situational characteristics are discussed extensively in both theoretical and empirical research into trust in education. With regard to educational settings, Schäfer (Citation1980) highlights the asymmetry of trust in terms of the unevenly distributed effects of damaged trust. For instance, the loss of a teacher’s trust in a student may marginally affect the teacher but simultaneously cause motivational problems on the part of the student and result in lower educational achievements (Schulte-Pelkum et al., Citation2014; Schweer & Bertow, Citation2006). Apart from situational characteristics, educational research examines broader societal context conditions and the way these factors shape the effect of education on trust (Frederiksen et al., Citation2016), as well as personal characteristics such as gender, age, education, socio-economic status, etc. (Borgonovi & Burns, Citation2015).

Concerning the trust relationships that can develop between those who trust and the trusted in role-based educational settings, Schäfer (Citation1980) conceives trust between teachers and students as institutional trust (in terms of “trust because of an institution”) rather than interpersonal trust. This is an important thought, however, because in educational research there is generally no mention of what form of institutional trust is being investigated—“trust because of an institution” or “trust toward an institution.” Yet this distinction could lead to insights into the interplay of institutional and interpersonal trust in the highly complex context of education. In this field, as in other complex areas of society, trust cannot be placed blindly—there is too much at stake for both the individual who irreversibly invests parts of his or her life in education and society as a whole that invests in and relies on educated citizens. Because the outcomes of education cannot be anticipated, mechanisms are required to deal with uncertainties that, for example, result from limited knowledge about education outcomes. Monitoring instruments are often introduced for this purpose, which are intended to help reduce ignorance and thus institutionalize distrust through self-observation and, therefore, signal trustworthiness (Lepsius, Citation2017, p. 81; Luhmann, Citation2000). Such instruments, for example, include forms of fixed monitoring of the performance of individuals or even institutions in the educational system, such as student achievement studies or school inspections that lead to accountability in education (Ehren et al., Citation2020). In general, the perceived trustworthiness of institutions relies on the perceived legitimacy of their guiding principles as well as on the institutional order responsible for acting effectively and efficiently (Lepsius, Citation2017, p. 82).

Braithwaite assumes that institutionalized distrust “makes it easier to trust others interpersonally” (Braithwaite, Citation1998, p. 369). Particularly in the case of education O’Neill holds that “systems of accountability are seen as replacing trust by supporting trustworthy performance, thereby making it less important to judge where trust should be placed or refused” (Codd, Citation1999; Moos & Paulsen, Citation2014; O’Neill, Citation2013, p. 9).

Like other research, educational research mostly highlights positive impacts of trust. For example, trust is found to increase or improve cooperation (Kikas et al., Citation2011; Thies, Citation2014), foster reform and change (Bryk & Schneider, Citation2002), prevent teacher burnout (Van Maele & Van Houtte, Citation2015), or promote student engagement and success (Thies et al., Citation2021). However, while relationships on different levels are thus analyzed, the radius of trust approach so far appears widely neglected in educational research. This is surprising in that such a perspective may yield interesting insights into studies on the quality of networks, which has emerged as an important field of research in education.

Trust matters in many different ways in education, and so does education for the development of trust. Trust is also known to act upon relationships relevant in education. In line with the variety of relationships between education and trust, several research approaches can be identified.

Firstly, education is a pivotal precondition for the individual development of trust for several reasons. Education contributes to the development of insights, values and knowledge. It promotes the development of various cognitive skills that help to successfully interact with others and to enter different occupations in line with educational attainment. What is more, educational institutions are core instances of socialization (Borgonovi & Burns, Citation2015). Each individual institution has a role in building trust toward educational institutions as well as to institutions in general, as learners transfer their general experiences of, for example, fair treatment, distributional and interactional justice to other people and institutions (Abdelzadeh et al., Citation2015; Hoy & Tarter, Citation2004; Lundberg & Abdelzadeh, Citation2019). The benefits of trust derived in educational settings therefore go beyond the individual level and are crucial for society.

Secondly, trust is an essential foundation of education, learning and achievement in that it fosters cooperation. This refers to the many different interactions among the various people involved in formal education, e.g., students, teachers, parents, principals, inspectors. Trusting relationships have been shown to positively affect educational involvement and attainment (Borgonovi & Burns, Citation2015; Neuenschwander, Citation2020; Rosenblatt & Peled, Citation2002; Strier & Katz, Citation2016). Moreover, mutual trust perceptions among teachers and their students contribute to enhanced interaction quality (Thies, Citation2005). In addition, trust is considered a core resource for educational reforms (Bryk & Schneider, Citation2002). Making an effort to build and maintain trust in educational settings therefore appears to be worthwhile in many respects.

Thirdly, in some cases together with further variables trust can foster learning outcomes (Goddard et al., Citation2009; Li et al., Citation2017) or prevent teacher burn-out (Van Maele & Van Houtte, Citation2015) by promoting positive relations in education. Trust is also seen to interact with the implementation of accountability and monitoring practices that are assumed to touch upon teachers’ professional commitment (Ehren et al., Citation2020; Lillejord, Citation2020; Ozga, Citation2013; Paulsen & Høyer, Citation2016; Sahlberg, Citation2010).

As comparative studies show, factors external to educational interaction influence the development and consequences of trust in education. Such exogenous factors include macro-social factors such as, for example, societal structure, political culture, educational governance (see Niedlich, Citationin this special issue). Trust toward education can also be affected by exogenous factors. Although educational services are reported to achieve positive views in general (Van de Walle, Citation2017, p. 120), scholars also posit that negative media reports about education can affect public opinion regarding the effectiveness and efficiency of educational institutions and can thus also impact trust in education (Kramer, Citation1999, p. 590; Pizmony-Levy & Bjorklund, Citation2018).

The Comprehensive Model of Trust in Education, Related Research Questions and European Perspectives

So far we have explained different notions of and approaches to trust and described how they are relevant in education. We have moreover referred to several topics of research into trust in educational settings. We have argued that the different approaches to trust in educational research are often not clearly specified, nor are the connections between different approaches addressed. Research often tackles details of complex educational processes in order to conduct rigorous and precise studies. However, following Lumineau and Schilke (Citation2018), we posit “that trust is inherently a multi-level phenomenon and, thus, that our understanding of trust development should embrace the reciprocal relationships between micro and macro perspectives” (Lumineau & Schilke, Citation2018, p. 239). That is to say, the preconditions and consequences of trust need to be thought of in a wider context and their analysis should incorporate findings from a broad range of disciplines.

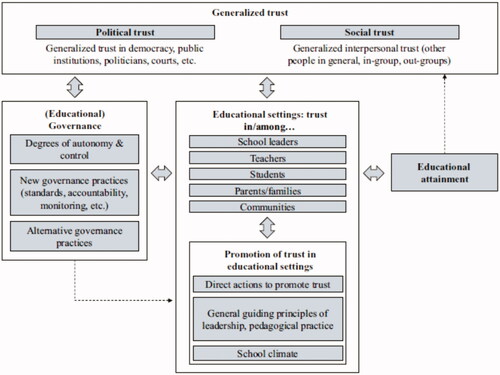

Against this background, in a prior study the authors conducted a systematic review of interdisciplinary research that resulted in a “comprehensive model of trust in education” (Niedlich et al., Citation2021). As shows, this model is composed of four elements: “trust in/among educational settings,” “educational attainment,” “generalized trust” and “educational governance.” As far as we can see, most (educational) research addresses “trust in or among educational settings” and ways of promoting trust in the relationships among different stakeholders in education. Some research also refers to “educational attainment” as both a result and a precondition for social trust. “Educational governance” is only scarcely considered as influencing trust in or among educational settings, e.g., through the way in which accountability is put into practice. Research on how educational governance is influenced by “social trust” does not yet seem to exist, although one might assume that generalized trust in educational institutions and practitioners affects beliefs concerning the impact that governance decisions might have on educational settings and their ability to promote desired outcomes.

Figure 2. Comprehensive Model of Trust in Education (Niedlich et a., Citation2021).

Many of the complex interactions between educational settings, educational attainment, trust and governance have not yet been investigated thoroughly. Against this background, one advantage of this model is that it allows for understanding of the findings from research on specific aspects of trust in educational settings in a wider context, thus contributing to a better understanding of how preconditions and consequences of trust in educational settings are interconnected across different levels and realms of an education system. To guide future research, the following six interconnections and related questions can be deduced from the model.

Trust in/among educational settings and the promotion of trust. How do different interactions among stakeholders as well as their experiences with and expectations toward each other affect the trust they develop? How is the development of trust related to the characteristics of the situation?

Trust in/among educational settings and educational attainment. How do educational practices affect the quality of interpersonal trust and accordingly educational attainment?

Educational attainment and generalized trust. How do contextual conditions of educational institutions mediate the association between education and social trust? How does generalized trust shaped by education evolve over time and what are the potential critical junctures in its development?

Generalized trust and educational governance. How does generalized trust impact on preferences for different styles of educational governance: for instance, does a lower societal level of generalized trust lead to a preference for more control-oriented forms of educational governance?

Generalized trust and trust in/among educational settings. How does generalized trust interact with trust toward educational organizations? To what extent are there spillover effects from generalized trust to trust in educational institutions and governance styles?

Educational governance and trust in/among educational settings. In what respect does the choice of educational governance instruments impact on the trust of authoritative bodies toward educational practitioners?

Whereas some of these interconnections are well-established, research that sheds light on interconnections between educational achievement, the development of trust and modes of educational governance is fairly scarce. However, the papers compiled in this special issue particularly focus on these nexuses.

Intention and Overview of the Special Issue “Trust in Educational Settings. European Perspectives”

The special issue “Trust in Educational Settings. European Perspectives” intends to tackle the matter of trust in education by acknowledging its complexity. To this end, each single paper offers an in-depth insight into how different facets and functions of trust are scrutinized with regard to the development of, the influences on or the consequences of trust in the context of education. Together the papers provide original research on trust in different educational settings, including formal and informal education ranging from primary education to higher education across different European countries and by employing sound theoretical frameworks and empirical approaches. The individual sections of this special issue are situated in different formal and informal educational settings and examine the interactions among various actors. Together they reinforce the need to include the issue of trust in different fields of educational research such as home-school interaction, the promotion of motivation for educational attainment and the reduction of social inequality in education, as well as measures and means in educational governance and leadership.

As a whole, this special issue aims to

enhance the understanding of trust and trust processes in educational organizations and across different levels of European educational systems. From the broad range of topics, papers refer to the interplay of generalized trust and instruments of educational governance, the promotion of trust within educational organizations and the interconnection between the use of educational governance instruments and trust in educational organizations, as perceived by different stakeholders.

provide evidence relevant to research, practice, and policy by examining the specific implications of trust in different educational settings.

identify and strengthen new avenues in the cross-national research on trust within multi-level educational systems and inform a coherent research program on educational trust by means of rigorous research with reference to both its own empirical studies and theoretical approaches.

To do so, the contributions in this special issue are arranged in the following groups.

Part I: Introduction and Conceptual Framework on Studying Trust in Education in Different Countries

After this introductory paper, Sebastian Niedlich examines the role of national context and its use for causal explanation and case selection. Drawing on studies on welfare and educational regimes he identifies relevant system-level characteristics, derives analytical dimensions as a framework for cross-national comparison and explores how these dimensions can be linked to trust.

Referring to and comparing contrasting cases is a common approach in the social sciences. It allows for highlighting details of a specific phenomenon and provides more comprehensive information in terms of knowledge about general similarities and differences than a single case could offer. However, instead of applying a comparative research approach in a narrow sense, the following individual papers will address trust issues in a number of specific formal and informal fields of education that are each examined in one of five countries from across Europe. As context conditions are decisive for the development of trust and education, each country study provides insights into legal frameworks before focusing on trust issues in a specific educational field. Each paper also explains how the study is situated in the broader context of the comprehensive model of trust in education. Findings from the papers will be synthesized in a final paper to draw informed assumptions about the meaning of the country-specific context conditions of trust in education, as well as about the foundations of the comprehensive model of trust in education.

Part II: Trust in/among Educational Settings and the Promotion of Trust

In their vignette study involving parents in Germany, Inka Bormann, Dagmar Killus, Sebastian Niedlich and Iris Würbel analyze the relevance that different interactions between parents and schools have on parental trust in schools. They show that different types of situations activate the five facets of trust to different extents.

The paper by Marja-Kristiina Lerkkanen and Eija Pakarinen focuses on the role that parental trust in teachers plays in the motivation of students in Finland. The results of their statistical analysis show that parental trust in teachers predicts the child’s interest in mathematics and that in contrast the child’s interest predicts parental trust in teachers.

Mieke Van Houtte analyzes the interconnections among the student composition of schools, faculty trust and students’ controlled motivation. Based on complex statistical models with representative data from the Flemish region in Belgium, the study shows that students’ trust in teachers accompanies their level of motivation and that the effects of the school’s composition are ameliorated by faculty trust.

Part III: Educational Governance and Trust in/among Educational Settings

Anne Görlich’s research deals with the lack of trust among marginalized young people in Denmark who are not in education, employment or training (NEET). Based on qualitative interviews and ethnographic observations, the analysis addresses educational trust, self-trust and trustworthiness in the interaction of educators and young NEETs over time, and discusses how educational trust can be rebuilt.

The role of trust in the implementation of inclusion at schools in the Czech Republic is the topic of Milan Pol’s and Bohumira Lazarova’s paper. Qualitative data from several stakeholders in schools are analyzed to understand the role of the school context in the faculty’s development of trust in inclusive education. A particular focus is placed on how principals can support trust and cooperation in the process of change.

Based on a literature review, the paper by Jussi Välimaa is concerned with the nature of generalized trust and its consequences for trust toward educational institutions in Finland. Through a socio-historical lens the author discusses how generalized trust in a country’s public can be traced back to historically developed traditions and to what extent it can affect relationships in education.

Synthesis

The special issue is rounded off by a synthesis paper. It explores and discusses how the individual papers with their focus on specific national contexts help to substantiate the comprehensive model of trust in the multi-level educational system described in this introductory article. In addition, further areas for systematic research on trust within educational settings are discussed.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Inka Bormann

Inka Bormann is a professor of education at the Freie Universität Berlin and head of the division of General Education. Her research interests include social relationships, especially trust in different educational settings, educational governance and change in educational organizations.

Sebastian Niedlich

Sebastian Niedlich holds a university degree (diploma) in political science and a doctorate in sociology. He is a research associate in the Division of General Education at Freie Universität Berlin. His research areas include educational governance, trust in education, area-based education partnerships, school development, and evaluation theory and practice.

Iris Würbel

Iris Würbel is a research associate in the Division of General Education at the Freie Universität Berlin. She conducts research on the quality and role of social relationships, including trust, particularly in children’s coping with crises.

Notes

1 Basically, this broad definition refers to both interpersonal and institutional trust. However, in the case of institutional trust there is a distinction to be noted between trust towards individuals representing institutions and trust toward institutions (see below).

References

- Abdelzadeh, A., & Lundberg, E. (2017). Solid or flexible? Social trust from early adolescence to young adulthood. Scandinavian Political Studies, 40(2), 207–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12080

- Abdelzadeh, A., Zetterberg, P., & Ekman, J. (2015). Procedural fairness and political trust among young people: Evidence from a panel study on Swedish high school students. Acta Politica, 50(3), 253–278. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2014.22

- Alarcon, G. M., Lyons, J. B., Christensen, J. C., Klosterman, S. L., Bowers, M. A., Ryan, T. J., Jessup, S. A., & Wynne, K. T. (2017). The effect of propensity to trust and perceptions of trustworthiness on trust behaviors in dyads. Behavior Research Methods, 50(5), 1906–1920. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0959-6.

- Allan, J., & Persson, E. (2020). Social capital and trust for inclusion in school and society. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 15(2), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197918801001

- Bachmann, R. (2018). Institutions and trust. In R. Searle, A.-M. Nienaber, & S. B. Sitkin (Eds.), The Routledge companion to trust (pp. 218–228). Routledge.

- Ball, S. J. (2010). New voices, new knowledges and the new politics of education research: The gathering of a perfect storm? European Educational Research Journal, 9(2), 124–137. https://doi.org/10.2304/eerj.2010.9.2.124

- Beck, U., & Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2001). Individualization: Institutionalized individualism and its social and political consequences. Sage.

- Borgonovi, F., & Burns, T. (2015). The educational roots of trust. OECD Education Working Papers No. 119.

- Bormann, I. (2014). Transformationen der Thematisierung von Vertrauen in Bildung. In S. Bartmann, M. Fabel-Lamla, N. Pfaff & N. Welter (Eds.), Vertrauen in der erziehungswissenschaftlichen Forschung (pp. 101–123). Budrich.

- Bormann, I., & John, R. (2014). Trust in the education system – thoughts on a fragile bridge into the future. European Journal for Futures Research, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40309-013-0035-0

- Bormann, I., Killus, D., Niedlich, S., & Würbel, I. (2022, in this special issue). Home-school interaction: A vignette study of parents’ views on situations relevant to trust. European Education.

- Bormann, I., Niedlich, S., & Staats, M. (2019). Entwicklung und Validierung eines Instruments zur Erfassung der Vertrauensrelevanz ausgewählter Interaktionen zwischen Elternhaus und Schule. Zeitschrift Für Bildungsforschung, 9(2), 177–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s35834-019-00235-5

- Bormann, I., & Thies, B. (2019). Trust and trusting practices during transition to higher education: Introducing a framework of habitual trust. Educational Research, 61(2), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2019.1596036

- Bouckaert, G., & Van de Walle, S. (2003). Quality of public service delivery and trust in government. In A. Salminen (Ed.), Governing networks: EGPA yearbook (pp. 299–318). IOS Press.

- Braithwaite, V. (1998). Institutionalizing distrust, enculturating trust. In V. Braithwaite & M. Levi (Eds.), Trust and governance: Russell Sage foundation series on trust (pp. 343–375). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Bromme, R., & Kienhues, D. (2014). Wissenschaftsverständnis und Wissenschaftskommunikation. In T. Seidel & A. Krapp (Eds.), Pädagogische Psychologie (pp. 55–81). Beltz.

- Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for school reform. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Christoforou, A., & Davis, J. H. (Eds.). (2014). Social capital and economics: Social values, power, and identity. Routledge.

- Codd, J. (1999). Educational reform, accountability and the culture of distrust. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 34(1), 45–53.

- Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & LePine, J. A. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 909–927. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.909

- D’Olimpio, L. (2018). Trust as a virtue in education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 50(2), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2016.1194737

- Delhey, J., Boehnke, K., Dragolov, G., Ignácz, Z. S., Larsen, M., Lorenz, J., & Koch, M. (2018). Social cohesion and its correlates: A comparison of western and Asian societies. Comparative Sociology, 17(3–4), 426–455. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691330-12341468

- Delhey, J., Newton, K., & Welzel, C. (2011). How general is trust in “most people”? Solving the radius of trust problem. American Sociological Review, 76(5), 786–807. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411420817

- Eder, C. & Katsanidou, A. (2014). When citizens lose faith. Political trust and political participation. In C. Eder, I. C. Mochmann, & M. Quandt (Eds.), Political trust and disenchantment with politics. International perspectives (pp. 83–108). Brill.

- Ehren, M., Paterson, A., & Baxter, J. (2020). Accountability and trust: Two sides of the same coin? Journal of Educational Change, 21(1), 183–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-019-09352-4

- Endreß, M. (2014). Structures of belonging, types of social capital, and modes of trust. In D. Thomä, C. Henning, & C. Schmid (Ed.). Social capital, social identities (pp. 55–74). De Gruyter.

- Endreß, M. (2010). Vertrauen - soziologische Perspektiven. In M. Maring (Ed.), Vertrauen - zwischen sozialem Kitt und der Senkung von Transaktionskosten (pp. 91–113). KIT Scientific Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1524/9783486593471.1

- European Commission. (Ed.). (2017). Trust at risk: Implications for EU policies and institutions. Publications Office.

- Flanagan, C. A., & Stout, M. (2010). Developmental patterns of social trust between early and late adolescence: Age and school climate effects. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(3), 748–773. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00658.x

- Frazier, M. L., Johnson, P. D., & Fainshmidt, S. (2013). Development and validation of a propensity to trust scale. Journal of Trust Research, 3(2), 76–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2013.820026

- Frederiksen, M., Larsen, C. A., & Lolle, H. L. (2016). Education and trust. Acta Sociologica, 59(4), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699316658936

- Frevert, U. (2013). Vertrauensfragen. Eine Obsession der Moderne. C.H. Beck.

- Gambetta, D. (Ed.). (2000). Trust: making and breaking cooperative relations (Electronic ed.). University of Oxford.

- Giddens, A. (1995). Concequences of modernity. Blackwell Publishers.

- Glanville, J. L., & Paxton, P. (2007). How do we learn to trust? A confirmatory tetrad analysis of the sources of generalized trust. Social Psychology Quarterly, 70(3), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250707000303

- Goddard, R. D., Salloum, S. J., & Berebitsky, D. (2009). Trust as a mediator of the relationships between poverty, racial composition, and academic achievement. Educational Administration Quarterly, 45(2), 292–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08330503

- Honneth, A. (2012). Erziehung und demokratische Öffentlichkeit. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 15(3), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-012-0285-9

- Hoy, W. K., & Tarter, C. J. (2004). Organizational justice in schools: No justice without trust. International Journal of Educational Management, 18(4), 250–259. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540410538831

- Hoy, W. K., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (1999). Five faces of trust: An empirical confirmation in urban elementary schools. Journal of School Leadership, 9(3), 184–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268469900900301

- Janssen, M., Bakker, J. T., Bosman, A. M., Rosenberg, K., & Leseman, P. P. (2012). Differential trust between parents and teachers of children from low-income and immigrant backgrounds. Educational Studies, 38(4), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2011.643103

- Kikas, E., Poikonen, P. L., Kontoniemi, M., Lyyra, A. L., Lerkkanen, M. K., & Niilo, A. (2011). Mutual trust between kindergarten teachers and mothers and its associations with family characteristics in Estonia and Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 55(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.539852

- Korsgaard, M. A., Kautz, J., Bliese, P., Samson, K., & Kostyszyn, P. (2018). Conceptualising time as a level of analysis: New directions in the analysis of trust dynamics. Journal of Trust Research, 8(2), 142–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2018.1516557

- Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations.: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 569–598. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.569

- Lancee, B. (2017). Diversity, trust and social cohesion. In European Commission (Ed.), Trust at risk: Implications for EU policies and institutions (pp. 167–176). Publications Office.

- Legood, A., van der Werff, L., Lee, A., den Hartog, D., & van Knippenberg, D., (2022). A critical review of the conceptualisation, operationalisation, and empirical literature on cognition-based and affect-based trust (preprint). Journal of Management Studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12811

- Lepsius, M. R. (2017). Trust in institutions. In M. R. Lepsius & C. Wendt (Eds.), Max Weber and institutional theory (pp. 79–87). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44708-7_7

- Lewicki, R. J., & Bunker, B. B. (1996). Developing and maintaining trust in work relationships. In R. Kramer & T. Tyler (Eds.). Trust in organizations. Frontiers of theory and research (pp. 114–139). SAGE.

- Lewicki, R. J., McAllister, D. J., & Bies, R. J. (1998). Trust and distrust: New relationships and realities. The Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 438–458. https://doi.org/10.2307/259288

- Lewicki, R. J., Tomlinson, E. C., & Gillespie, N. (2006). Models of interpersonal trust development: Theoretical approaches, empirical evidence, and future directions. Journal of Management, 32(6), 991–1022. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306294405

- Li, L., Hallinger, P., Kennedy, K. J., & Walker, A. (2017). Mediating effects of trust, communication, and collaboration on teacher professional learning in Hong Kong primary schools. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 20(6), 697–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2016.1139188

- Lillejord, S. (2020). From “unintelligent” to intelligent accountability. Journal of Educational Change, 21(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-020-09379-y

- Luhmann, N. (2000). Confidence, trust: Problems and alternatives. In D. Gambetta (Ed.), Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations (Electronic ed., pp. 94–107). University of Oxford.

- Lumineau, F., & Schilke, O. (2018). Trust development across levels of analysis: An embedded-agency perspective. Journal of Trust Research, 8(2), 238–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2018.1531766

- Lundberg, E., & Abdelzadeh, A. (2019). The role of school climate in explaining changes in social trust over time. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(5), 712–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2018.1434824

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792

- McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24–59.

- Misztal, B. A. (2011). Trust: Acceptance of, precaution against and cause of vulnerability. Comparative Sociology, 10(3), 358–379. https://doi.org/10.1163/156913311X578190

- Möllering, G. (2013). Process view of trusting and crises. In R. Bachmann & A. Zaheer (Eds.), Handbook of advances in trust research (pp. 285–305). Edward Elgar.

- Moos, L., & Paulsen, J. M. (2014). School boards in the governance process. Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05494-0

- Neuenschwander, M. P. (2020). Information and trust in parent-teacher cooperation – Connections with educational inequality. Central European Journal of Educational Research, 2(3), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.37441/CEJER/2020/2/3/8526

- Niedlich, S. (2022, in this special issue). Cross-national analysis of education and trust – context, comparability and causal mechanisms. European Education.

- Niedlich, S., Kallfaß, A., Pohle, S., & Bormann, I. (2021). A comprehensive view of trust in education: Conclusions from a systematic literature review. Review of Education, 9(1), 124–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3239

- O’Neill, O. (2013). Intelligent accountability in education. Oxford Review of Education, 39(1), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2013.764761

- Ozga, J. (2013). Accountability as a policy technology: Accounting for education performance in Europe. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 79(2), 292–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852313477763

- Paulsen, J. M., & Høyer, H. C. (2016). External control and professional trust in Norwegian school governing: Synthesis from a Nordic research project. Nordic Studies in Education, 35(2), 86–102. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-5949-2016-02-02

- Pillutla, M. M., Malhotra, D., & Keith Murnighan, J. (2003). Attributions of trust and the calculus of reciprocity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39(5), 448–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1031(03)00015-5

- Pizmony-Levy, O., & Bjorklund, P. Jr. (2018). International assessments of student achievement and public confidence in education: Evidence from a cross-national study. Oxford Review of Education, 44(2), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2017.1389714

- Rosenblatt, Z., & Peled, D. (2002). School ethical climate and parental involvement. Journal of Educational Administration, 40(4), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230210433427

- Roth, H. (1963). Die realistische Wendung in der Pädagogischen Forschung. Die Deutsche Schule, 55(3), 109–119.

- Rothstein, B., & Uslaner, E. M. (2005). All for all: Equality, corruption, and social trust. World Politics, 58(1), 41–72. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2006.0022

- Rotter, J. B. (1980). Interpersonal trust, trustworthiness, and gullibility. American Psychologist, 35(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.35.1.1

- Rousseau, D., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393–404. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.926617

- Sahlberg, P. (2010). Rethinking accountability in a knowledge society. Journal of Educational Change, 11(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-008-9098-2

- Sawinski, Z. (2014). Social trust in education in European countries, 2002–2010. Edukacja, 130(5), 19–39.

- Schäfer, A. (1980). Vertrauen. Eine Bestimmung am Beispiel des Lehrer-Schüler-Verhältnisses. Pädagogische Rundschau, 34, 723–743.

- Schoon, I., Cheng, H., Gale, C. R., Batty, G. D., & Deary, I. J. (2010). Social status, cognitive ability, and educational attainment as predictors of liberal social attitudes and political trust. Intelligence, 38(1), 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2009.09.005

- Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (2007). An integrative model of organizational trust: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 344–354. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.24348410

- Schulte-Pelkum, J., Schweer, M. K. W., & Pollak, B. (2014). Dyadic trust relations between teachers and students – An empirical study about conditions and effects of perceived trustworthiness in the classroom from a differential perspective. Schulpädagogik Heute, 5(9), 1–14.

- Schweer, M. K. W. (1997). Eine differentielle Theorie interpersonellen Vertrauens. Überlegungen zur Vertrauensbeziehung zwischen Lehrenden und Lernenden. Psychologie in Erziehung Und Unterricht, 44, 2–12.

- Schweer, M. K. W., & Bertow, A. (2006). Vertrauen und Schulleistung. In M. K. Schweer (Ed.), Bildung und Vertrauen (pp. 73–89). Peter Lang.

- Schweer, M. K. W., & Thies, B. (2008). Vertrauen. In A.-E. Auhagen (Ed.), Positive Psychologie (2nd ed., pp. 125–138). Beltz.

- Schweer, M. K. W., Petermann, E., & Egger, C. (2013). Zur Bedeutung multidimensionaler sozialer Kategorisierungsprozesse für die Vertrauensentwicklung – Ein bislang weitgehend vernachlässigtes Forschungsfeld. Gruppendynamik Und Organisationsberatung, 44(1), 67–81, 93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11612-012-0202-y

- Shayo, H. J., Rao, C., & Kakupa, P. (2021). Conceptualization and Measurement of Trust in Home-School Contexts: A Scoping Review. Frontiers in Psychology. Educational Psychology, 12:742917. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.742917

- Strier, M., & Katz, H. (2016). Trust and parents involvement in schools of choice. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 44(3), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214558569

- Thies, B. (2005). Dyadisches Vertrauen zwischen Lehrern und Schülern. Psychologie in Erziehung Und Unterricht, 52(2), 85–99.

- Thies, B. (2014). Beziehungsgestaltung in der Schulklasse.: Steigerung der Interaktionsqualität durch Vertrauen und Classroom Management. In D. Raufelder (Ed.), Beziehungen in Schule und Unterricht. 1. Theoretische Grundlagen und praktische Gestaltungen pädagogischer Beziehungen (Vol. 23, pp. 188–209). Prolog-Verl.

- Thies, B., Heise, E., & Bormann, I. (2021). Social Exclusion, Subjective Academic Success, Well-being, and the Meaning of Trust. Zeitschrift Für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie, 53(1-2), 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1026/0049-8637/a000236

- Van de Walle, S. (2017). Trust in public administration and public services. In European Commission (Ed.), Trust at risk: Implications for EU policies and institutions (pp. 118–128). Publications Office.

- Van de Walle, S., & Six, F. (2014). Trust and distrust as distinct concepts: Why studying distrust in institutions is important. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 16(2), 158–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2013.785146

- van Hoorn, A. (2014). Trust radius versus trust level. American Sociological Review, 79(6), 1256–1259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414555398

- van Knippenberg, D. (2018). Reconsidering affect-based trust. In R. Searle, A.-M. Nienaber & S. B. Sitkin (Eds.), The Routledge companion to trust (pp. 3–14). Routledge.

- Van Maele, D., & Van Houtte, M. (2015). Trust in school: A pathway to inhibit teacher burnout? Journal of Educational Administration, 53(1), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-02-2014-0018

- Weiss, C. H. (1979). The many meanings of research utilization. Public Administration Review, 39(5), 426–431. https://doi.org/10.2307/3109916

- Zucker, L. G. (1986). Production of trust: Instututional sources of economic structure. Research in Organizational Behavior, 8, 53–111.