ABSTRACT

This article creates a crowdsourced database for Tarjimly, a humanitarian translation app, based on recent technical communication and translingual research. The humanitarian translation app is a unique technological site that recruits volunteer translators to interpret for migrants and refugees. Tarjimly’s privacy policy prevents translators from building their translingual repertoire across the platform. This database allows translators to crowdsource their colloquial interpretations so that others may learn about regional, cultural, and dialectal translations from Tarjimly’s humanitarian audiences.

This article demonstrates how researchers and practitioners can make humanitarian interventions with translingualism and tactical technical communication. Scholars interested in solving humanitarian problems must do so through indirect means. My demonstration attempts a humanitarian intervention using methods from translingualism and tactical technical communication. The genre for this study is the humanitarian translation app, an emerging technology that encapsulates nonprofit work, app development, and humanitarian translation into a single platform, free to use for interpreters and users. Spearheaded by Tarjimly, the first (and at the time of writing) only widely available app, the humanitarian translation app is a unique technological site that recruits volunteer translators to interpret for migrants, refugees, and asylees. As of Fall 2023, Tarjimly has over 56,000 translators that serve 420,000 beneficiaries that speak 174 languages according to their website. The exigence of Tarjimly is that machine and AI translation can often overlook or misrepresent cultural, historical, and regional contexts in its translation (refer to Tarjimly., Citationn.d.org). In essence, two things set Tarjimly apart from other translation services and establishes a trait for the emerging genre of the humanitarian translation app: 1) The instantaneous matching of an interpreter and a person in need and 2) The human-to-human translation that occurs instantly in conversation. I will explore these two factors through the lenses of translingual practice and tactical technical communication.

Tarjimly is a good place to study translingual practice and tactical technical communication. Translingual practice and translanguaging is an orientation that views all available emergent resources during translation as valid for use by the speakers. Tarjimly requires volunteer humanitarian translators to interpret for users from hundreds of countries who speak dozens of native languages, requiring the translators to work with emergent resources and negotiate under dire circumstances (Tarjimly, Citationn.d.). At once, Tarjimly’s translators and usersFootnote1 work with each other, smart devices, training protocols, learned repertoires of languages and gestures, poster boards, flyers, and other resources in an assemblage of entanglements that involve language, materials, and people all working together (Pennycook, Citation2020). The challenge of capturing such an assemblage is that Tarjimly is a location with vulnerable populations under desperate situations. It is not possible to directly study the humanitarian audiences of Tarjimly in ways we have studied other audiences before. And although translingual practice and translanguaging have had recent calls and responses for more direct studies (Canagarajah & Gao, Citation2019; De Los Ríos et al., Citation2021; Gevers, Citation2018; Gilyard, Citation2016; Pennycook, Citation2020),Footnote2 I argue that a compromise must be made if we are to apply our knowledge of translingual practice and tactical technical communication at Tarjimly. We must rethink how to indirectly study and intervene at humanitarian sites like Tarjimly to respect the vulnerability of humanitarian audiences while also providing solutions to apparent problems. A solution offered here is a database in which translators crowdsource to build their repertoire across the app.

The results of machine and AI translation are well documented in and beyond TPC. There are two general occurrences (I pause to say problems) that can occur when using software like Google translate. The first is the most documented in that these AIs do not account for culture, context, and situation all too well. The machine can produce unintended bias on the lines of race, gender, and sexuality, and the translation results can be inappropriate (Prates et al., Citation2020). The second is that these machines can give a number of translation choices that can leave users overwhelmed. Gonzales (Citation2018) in Sites of Translation mentions that these choices can actually enrich multilingual interaction as users negotiate with the software and people to arrive at enriched translation moments. However, Tarjimly recognizes that these occurrences can hinder the distribution of aid to people in dire need during humanitarian circumstances. In other words, by recruiting volunteers, Tarjimly hopes that people can do the legwork of choosing the appropriate translations so that users (migrants, refugees, and asylees) can spend more time receiving resources. The solution is to get the best of both worlds: humanitarian audiences that use Tarjimly can have the convenience of an app that essentially instantly translates but through the labor of volunteer interpreters.

However, this merger of technology and human labor has issues that translingual studies and technical communication can address. The humanitarian translation app is a new area for both translingual studies (which has been mostly focused on classroom situations) and tactical technical communication (which has been mostly focused on nonhumanitarian communication). One problem is Tarjimly’s privacy policy. Every conversation is erased upon completion, and translators are instructed not to share any details that can disclose sensitive information. This policy exists to protect the Personally Identifiable Information (PII) of the userbase, which can include sensitive medical and legal information. Tarjimly erases all records of the translation and prevents translators from learning from their translations and the translations of other translators. I argue that such a policy does not allow translators to learn from translation moments (Gonzales, Citation2018) nor does it allow translators to build a translingual repertoire across the platform (Canagarajah, Citation2013, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). An alternative would allow translators to learn from translations across the platform, crowdsourcing the tactical technical communication of translators so that others can be better equipped in certain translation moments while also protecting PII.

Translingualism and tactical technical communication are good areas of study to investigate Tarjimly. The genre of the humanitarian translation app lends itself to these areas of study because of the reliance on volunteer translators (translingualism) and the need for translators to use the apps interface to facilitate successful translation (tactical technical communication). On the translingual side, volunteers are negotiating with migrants, refugees, and asylees to arrive at the most effective translations, often using whatever emergent resources are available. On the tactical technical communication side, volunteers are learning the best translation approaches during their interpretations; however, because of Tarjimly’s deletion of conversations and lack of infrastructure for Translator’s to share knowledge, there is no way for volunteers to build their tactics across the platforms. My argument here is that Tarjimly should offer more emergent resources to their translators and that those resources should be crowdsourced from their translators.

I created a proof of concept for Tarjimly, an added feature that both respects user privacy and builds translator repertoire across the platform. The feature is a database where translators can anonymously donate their knowledge of regional, cultural, religious, and colloquial dialects to Tarjimly; other translators can then, in real time, use the database to aid in their translations if they come across unknown words or phrases. Such an intervention follows the most recent research in trans- and multilingual studies by the likes of Suresh Canagarajah and Laura Gonzales where it is understood that effective translation depends on how translators and users use emergent resources to convey meaning and negotiate in translingual practice. However, unlike previous studies, this study will not investigate how interlocutors deploy translingual practice in real time. Instead, because of humanitarian problems to be described, this article provides a proof of concept that in practice could facilitate translingual practice. This proposed feature will be an emergent resource not only for the translators but also for the users who inform the translators’ approach to the task. Such a technology added to Tarjimly can enhance translators’ learning on how to interpret on humanitarian translation apps, develop translation skills at a more efficient rate, raise awareness of global and regional translation contexts, and allow technical communicators to further translation studies on such a new, uniquely humanitarian, technology.

The crowdsource database achieves two things. The first is further committing Tarjimly to the merger of technology and human labor. Tarjimly’s method of erasing conversations upon the completion of translation somewhat contradicts the point of peer translation. Users who depend on machine translation do not have opportunities to share their experiences with others within the interface of the software (Google translate, for example). Tarjimly displays similar limitations in that volunteers cannot share with others about their experiences. My crowdsourced database allows Tarjimly volunteers to donate their knowledge on translation in a feature directly available on the Tarjimly interface. Other volunteers can then search that database for resources in their translation in real time. Secondly, and perhaps most important to the field, is that the database works within the humanitarian limitations of Tarjimly. The feature respects the policies and guidelines of the platform while also giving another resource to both volunteers and users without interruption to the humanitarian mission – a mission that will be further explored in the article. Overall, what this database offers to both academic and humanitarian spaces is an indirect method that can give immediate resources to those in need.

This article first reviews the literature on humanitarian issues of direct study, translingual practice, and tactical technical communication. Then, I describe Tarjimly, including anecdotes of my personal experience as a volunteer translator and providing an explanation of the problems one may encounter when using the platform. Finally, I showcase proof of concept, the crowdsourced database that allows volunteer translators to use more of their translator repertoire to improve the efficiency and accuracy of the translations across the app.

The humanitarian, translingual practice, and TPC

Humanitarian sites, no matter if brick-and-mortar or digital, are locations of intense intercultural communication where people in dire circumstances seek the aid of a mostly volunteer labor force. They are hubs of connection, interaction, and assistance where displaced individuals from diverse cultural, linguistic, and geographical backgrounds converge. These centers are places of refuge, meeting urgent needs such as food, clothing, and shelter, while also facilitating travel arrangements, legal assistance, and more. Inherent in their operations is the constant challenge of bridging language barriers and cultural differences to communicate effectively with the migrants they serve. Volunteers at these sites often rely on a variety of tools and resources to help them communicate, from language documents and translation apps to gestures and physical cues. The versatility and adaptability of the volunteers is paramount in these settings, as they must navigate various languages and customs to ensure each migrant is properly assisted. This navigation necessitates a learning process that often evolves in real time, with volunteers adapting their approach as new situations and challenges emerge.

Numerous factors make humanitarian sites difficult to study. Research on humanitarian logistics is the most abundant studies on the humanitarian (Paciarotti et al., Citation2021; Shao et al., Citation2020; CitationTomasini & Van Wassenhove, Citation2009a, Citation2009b). Supply chains and logistics are more accessible and require less effort in ethical data collection than if humanitarian studies were to research humanitarian audiences themselves. Even calls for more focus on localizing humanitarian aid do so through arguments of allocating humanitarian budgets to supporting localization efforts (Roepstorff, Citation2020) and not necessarily through arguments of how to do such localization at the volunteer level. Humanitarian audiences and volunteers tend not to stay at humanitarian sites. Migrants, refugees, and asylees only remain at a site long enough to receive aid and then they are off to another location; volunteers work laboriously for no pay and often encounter emotionally taxing situations.

The ephemerality of humanitarian sites makes it difficult to directly study them. Audiences at these sites are composed of migrants, refugees, and asylees – demographics that are highly vulnerable, and protected by the humanitarian sites, to direct observation. For example, I tried to directly observe the quality of translation between translator and migrant on Tarjimly (more about the app and its interface in an upcoming section). I wanted to study how translators and migrants rely upon translingual practice and how they create tactical technical communication. However, my IRB proposal was rejected and Tarjimly shared serious concerns about my presenting as both a volunteer and a researcher. One concern was informed consent. Humanitarian audiences are under dire circumstances, and it can be unethical to take resources away from the mission of an operation like Tarjimly (to provide humanitarian translation in real time). And this concern, along with others, are reflected in the small amount of humanitarian scholarship in our and in adjacent fields. Getto and Flanagan (Citation2022), for example, recognize how difficult it is for nonprofits to anticipate audience needs because of the lack of direct participation of many marginalized populations in situations where technical communicators expect feedback. Other authors tend to agree that this problem of direct participation is exacerbated in humanitarian contexts due to the likely life-or-death circumstances that humanitarian audiences face (Baniya, Citation2022; Mays et al., Citation2013; Tomasini & Van Wassenhove, Citation2009b; Walton et al., Citation2016). It can be unethical, and, in fact, impractical, to try to directly observe a humanitarian audience at a humanitarian site. Translinguists and technical communicators can contribute to humanitarianism, but contributions will have to be made in ways besides direct observation methods.

Translingual practice and TPC: approaches and methods

TPC and translingual scholars have used indirect observation methods outside humanitarian sites. Indirect observation can have a number of definitions, but in humanitarian circumstances I find that indirect methods are those that work around the direct participation of subjects in dire need. Both fields have done work with vulnerable populations outside humanitarian circumstances. For example, in a study that uses methods from both TPC and multi- and translingualism, Gonzales et al. (Citation2022) interview Indigenous language speakers in three countries for their help on redesigning technical documentation about COVID-19. This study, although intended to help marginalized communities harmed by exclusionary translation practices, chooses not to directly study how community members are harmed by the current translation practices (a method called “damaged-based research,” from which the authors cite Tuck, Citation2009, p. 36). Instead, following values in decolonial methods such as participatory localization (G. Agboka, Citation2013), Gonzales et al. choose to collect technical documents and then interview community members about their thoughts of the translation process – a methodology that moves beyond the direct intrusion of the harmed community. In inclusion of community members in the evaluation of translation respects the importance of localization and bottom-up decision making in translating materials (G. Agboka, Citation2013; Gonzales, Citation2021; Gonzales & Zantjer, Citation2015; Jones, Citation2016) while also moving us away from damage-based research.

Both the fields of translingualism and technical and professional communication (TPC) have certain direct methods of observational study when it comes to their scholarship. In translingualism, translingual practice is generally defined as the availability and usefulness of emergent resources, broadly encompassing, to language speakers negotiating with one another to find a working translation. Translingual resources can be, but are not limited to, sights, smells, awkward pauses, gestures, eye contact, and more – all working together with the language speakers until a mutual understanding is reached (Horner et al., Citation2011; Jordan, Citation2015). Many scholars observe sites such as the workplace and the classroom to study how language speakers use emergent linguistic and environmental resources to negotiate with one another on the meaning of translation (Canagarajah, Citation2013, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; De Los Ríos et al., Citation2021; Gonzales, Citation2015; Jordan, Citation2015; Pennycook, Citation2020; Sun & Ge, Citation2021). Translingual scholars have been known to use fictional anecdotes to illustrate translingual practice in a controlled environment (refer to Siva’s Market in Suresh Canagarajah’s (Citation2013) Chapter 3 of Translingual Practice,), an exercise that will prove helpful in my illustrating the humanitarian. In TPC, scholars tend to directly observe the interactions between interlocutors of technology such as experts and audiences, communicators and users, or whatever combination is involved in communication. The observations typically are in the form of surveys, focus groups, questionnaires, and other genres of information collection in which audiences and users can give feedback on their experiences with a technology.

Many translingualists observe the translingual practice of language speakers in relation to the interaction between people, environment, and emergent resources. Most translingualists would agree on “the perspective [that] language speakers can communicate more effectively if they have access to their full range of multilingual repertoires (Pacheco et al., Citation2019); that is, the best environment to promote communication allows language speakers to use whatever is available to communicate with one another. That drawing of multilingual repertoires is translingual practice, or “the bundles of activity that involve mobilizing and meshing divergent semiotic resources – including uses of the body, texts, shared understandings of context, and linguistic resources” (Pacheco et al., Citation2019, p. 76). What translingual scholars can directly observe are how language speakers use emergent resources, resources that are not premeditated, fixed, nor static, to negotiate with one another.

A current trend in translingualism is more fully investigating how environments are resources in translingual practice. Pennycook (Citation2020), for example, expands upon many ideas from the likes of Blommaert (Citation2013) and Canagarajah (Citation2013) that emphasize the semiotic complexity of the environment – people, gestures, spoken language, time of day, soundscapes, smellscapes, and everything in between – when we consider the translingual practice of speakers and their “translingual entanglements” (p. 223). Pennycook’s use of entanglement advances how resources (the English language in his case) are not neutral operatives for use by language speakers but rather how these resources are entangled in the “assemblages of linguistic resources, identifications, artefacts and places [and I would add people]” (232).This observation of translingual practice needs to consider how the entanglements of the full range of multilingual repertoires are themselves entangled in other assemblages and that those entanglements are not dropped when used to negotiate meaning, no matter if that resource is a shared understanding of English, or another language, or other emergent resources.

Technical communication scholarship often observes the problems and solutions that arise from a userbase engaging with technology. One interesting area of study is tactical technical communication, the observations of how grassroots solutions are crowdsourced by users for technological problems where either expert interaction is either unavailable, unaffordable, out of touch, or otherwise absent to a large part of a userbase (Kimball, Citation2006, Citation2017). In the traditional sense, technical communicators are professionally trained workers who help accommodate users to the language and use of technology (Kimball, Citation2017). However, tactical technical communication recognizes how communities crowdsource the accommodation of language and the use of technology outside the purview of experts. Calls to social justice (Acharya, Citation2019; Colton & Holmes, Citation2018; Jones, Citation2016; Veeramoothoo, Citation2020; Walwema et al., Citation2022), inclusive user practices such as localization (Acharya, Citation2019; Acharya & Dorpenyo, Citation2023; G. Agboka, Citation2013; Gonzales, Citation2018), the responsible engagement of decolonial perspectives (G. Y. Agboka, Citation2014, Citation2021; Itchuaqiyaq & Matheson, Citation2021a, Citation2021b), and recognizing crowdsourced tactical communication (Alexander & Edenfield, Citation2021; Colton et al., Citation2017; Das & Tham, Citation2022; Kimball, Citation2006; Sarat-St Peter, Citation2017) all challenge technical communicators to accommodate for the most marginalized of audiences through that audiences’ own understanding of problems and solutions.

The study of tactical technical communication has evolved to reach social justice ends and hopefully one day to humanitarian ends. Many scholars noted that Kimball’s (Citation2006) distinction of strategies and tactics from de CerteauFootnote3 was not necessarily engaged with social justice (although it was certainly not excluded) (Colton et al., Citation2017; Ding, Citation2009; Sarat-St Peter, Citation2017). However, the inherent power dynamics in considering tactics and strategies allowed for the field to engage in social justice in the study of tactical technical communication. Take, for example, Das and Tham (Citation2022) and their description of how a Reddit community (r/WallStreetBets) tactically communicated within a forum to teach each other how to short squeeze GameStop or buy mass amounts of their stock against the prediction of investors hoping that the stock will fall. The authors found that the users of r/WallStreetBets were working class individuals in nonfinance professions crowdsourcing with one another on the ins and outs of buying stocks in part protest, and other parts in meme or troll stock investing, to nonetheless engage in a “social uptake” of a typically inaccessible technology in buying and trading stocks (p. 25). This example shows how a lay audience tactically organized piece by piece to go against the larger strategies of those with power.

A good example of the approaches of the two fields is Higgins and Furukawa (Citation2020) where the authors create a training protocol to help workers at a call center in Dominica better communicate with a native Hawaiian population that speaks Pidgin through a localization informed by such speakers. The authors promoted the translingual practice of the workers to recognize, reflect, and negotiate the Pidgin used by the callers. Take for instance the “contextualization cues” the authors developed to help the Dominican workers negotiate with a frustrated Pidgin speaker (62). Under the category, “Lexical items indexing interpersonal distance,” the contextualization cues teach the workers to recognize how phrases such as “you guys,” “how come,” and “buggah” (marked by a style shift to heavier Pidgin) indicate that the caller is growing frustrated by the misunderstandings between them (p. 62). The authors recommended that the workers practice an empathy aligned with Pidgin by supplementing their English with select Pidgin words used by the caller (the worker might pick up “buggah,” for example). The workers are encouraged to be reflexive and use the emergent contextualization cues to show empathy and understanding to the caller, even if the worker does not fully understand the use of the cue in the moment.

The training program relied upon the tactical technical communication between the workers and callers to make informed decisions on the protocol. Higgins and Furukawa (Citation2020) developed their protocol through extensive localization efforts of native Pidgin speakers from the targeted community. Consultations with Da Pidgin Group established a dialogue between Pidgin speakers and the authors so that the protocol could not only have localized translations but also be regularly updated. For example, members from Da Pidgin Group informed the protocol of how to respond to certain contextualization cues, demonstrated how to practice a localized empathy specified to their Pidgin community, and recommended certain words or phrases to try in conversations (pp. 623–625). Such efforts are tactical technical communication because the authors and Da Pidgin Group crowdsourced the resources that the workers would need while establishing dialogs among all involved parties on the best practices.

Higgins and Furukawa (Citation2020) is a good example of how translingual practice and tactical technical communication can be observed in a case study. However, some characteristics of the study could make it difficult to translate the methodology to a humanitarian site. The Dominican workers train through the authors’ program, practice their learned localizations of language and customs, and then provide real-time feedback by taking calls from native Hawaiian Pidgin speakers, informing the authors of the adjustments they must make to their training modules. We see here that the authors rely upon the direct participation of the involved audiences of their training program.Footnote4 The authors can observe the worker’s use of emergent resources, including the negotiation of the resources learned through the training, while also making technological improvements based on the tactical communication done by the native Pidgin speakers and the Dominican workers.

If one were to observe the translingual practice and tactical technical communication at a humanitarian site, the study would have to consider the indirect participation of a population such as undocumented migrants. For the most part, these humanitarian audiences, audiences in dire need of humanitarian assistance, are too vulnerable and ephemeral to participate in the ways of the audiences we have come across so far. Humanitarian audiences only stay in one location long enough to receive assistance (Tomasini & Van Wassenhove, Citation2009a, Citation2009b; Walton et al., Citation2016). And even in situations like disaster response, where a humanitarian audience can remain in one location for a longer period, there are issues of informed consent, ethics of care, and the overall mission of humanitarianismFootnote5 that make it questionable to have a humanitarian audience directly participate in an observational study (Aguilar, Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Baniya, Citation2022; Mays et al., Citation2013). These circumstances cause a problem. Clearly, technical communicators and translingualists have the expertise to make meaningful changes at humanitarian sites; however, we need a different approach that allows for the indirect participation of humanitarian audiences to inform, and localize, our approaches. This problem is addressed in creating a feature for Tarjimly.

Understanding Tarjimly

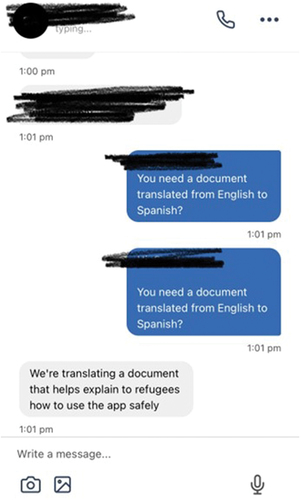

Tarjimly has policies in place that are meant to protect the privacy of both translator and user but can limit the translingual practice and tactical technical communication of Tarjimly’s translators and humanitarian audiences. After a push notification notifying appropriate translators, the two parties – the translator and migrant or the translator and migrant with a social worker – are then put into an instant messenger where the conversation can begin through text messaging, photo messaging, or internet voice call (). The translation occurs in real time, with a range of resources sanctioned and not sanctioned by Tarjimly. For example, sanctioned resources are the options to send photos and use voice calls to negotiate the meaning of a translation. Unsanctioned resources can be the Google Translate used by a translator or perhaps a cheat sheet created by a translator to give contextualization cues for a certain demographic (Higgins & Furukawa, Citation2020). In any case, Tarjimly expects certain methods of use for the application, and it is in their policy that delineates what is or isn’t sanctioned or expected. Every translatorFootnote6 must go through compliance training that instructs on the policies of use (AppendixInsert link to Supplemental File: Appendix). For the most part, the interface protocol prevents PII and PHI by limiting each translator to one conversation at a time and deleting each conversation upon completion of the translation request.

Although the policies in place do protect the privacy of the parties in translation, there can be revisions to the interface that allow translators and migrants access to their full range of multilingual repertoire. The anonymity between translators (there is no sanctioned communication between those who volunteer at Tarjimly) and the deleting of conversations after a translation is complete limits how translators can build a repertoire within their own practice as well as across the platform. Both translingualists and tactical technical communicators would agree that allowing the bottom-up facilitation of communication, be it through translingual practice or crowdsourcing information, improves the quality of that communication (Alexander & Edenfield, Citation2021; Canagarajah, Citation2018b; Das & Tham, Citation2022; Kimball, Citation2017; Pacheco et al., Citation2019; Sun & Ge, Citation2021). In fact, one of the leading books in studying translation from a trans-, multilingual, and technical communication lens, Sites of Translation, argues for the recognition of “translation moments,” or the time taken by speakers to negotiate the resources for best translation (Gonzales, Citation2018, p. 12). It is clear that the best environments for translation occur in spaces, digital or otherwise, that allow speakers to take home what they have learned and share it. Tarjimly can simultaneously protect the privacy of their users while allowing for the building of translator repertoire across the platform by sanctioning the sharing of what translators have learned.

Proof of concept and method

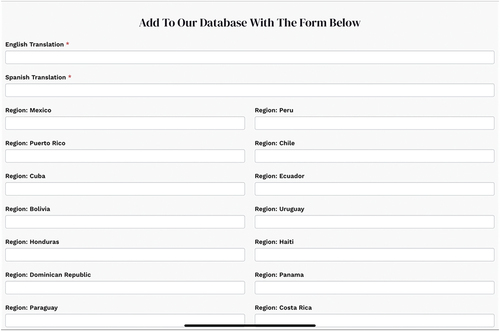

With the help of a colleague,Footnote7 I created a proof of concept for a feature Tarjimly can add to its interface to improve the learning from translingual practice and tactical technical communication across the platform. I told a colleague of my experience with Tarjimly and idea to create a database for the platform. I explained my ideas of incorporating regional translations so that translators can donate and receive resources on translating for certain demographics in accordance with research in translingual and TPC studies. He created a customizable template on a website domain, shared the URL, and we worked on some designs until we arrived at what is shown in . We prioritized a simple design with clear input and output instructions, so that Tarjimly can understand the proof of concept and consider integrating it into their interface. Overall, the database is a work in progress that showcases the main purpose of an incorporated crowdsourced database in Tarjimly’s interface.

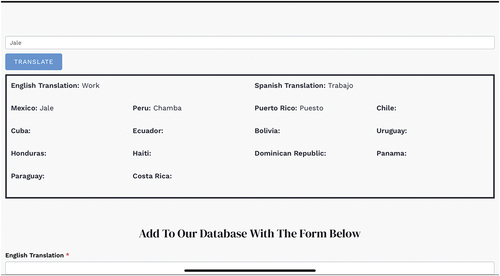

The feature is a database in which translators can donate their expertise and experiences of interpreting for translation according to region, culture, dialect, time, and other factors that can add nuance that otherwise is only learned through experience. Keep in mind that the translators are minimally vetted according to their translation ability; Tarjimly simply asks someone if they can translate for certain languages and circumstances. There is no real examination or follow-up on if the translator can perform their translations as claimed.Footnote8 This lack of vetting means Tarjimly has quite the range of translation experience among translators. So, for example, if a translator has learned traditional Spanish and comes across slang from a Mexican migrant who claims they are in the United States looking for “chamba” (slang for trabajo or work), then there is a good chance that that translator might not know the Spanish word nor its English translation. The translator could go to Google Translate, but Tarjimly advises their translators that such machine or AI translations are inferior to human-to-human translation because we are better equipped for nuance and cultural distinctions. My added feature () conceptualizes the best of both worlds: the instant finding of an unknown translation crowdsourced from human-to-human interaction from other translators.

The concept of my feature can promote translingual practice and tactical technical communication for translators across the platform, hopefully improving the quality and efficiency of translations for migrants. The feature gives translators an emergent resource in that, in real time, the database can be called upon, edited, and shared among the thousands of translators on Tarjimly. Translators can categorize their translations in accordance with language, culture, region, and other ways that I may have overlooked as the database evolves to accommodate migrants and social workers. The feature also allows migrants to indirectly participate in adding to the database as translators learn from each conversation and then share their knowledge with others.

Tarjimly can integrate prompts that encourage translators to donate to the database upon the completion and before the deletion of conversations. Currently, both translators and users are prompted to provide feedback on the effectiveness of the translation. The prompt, albeit simple, asks the translator to give a thumbs-up or down and asks what the conversation was about (if the matters are with regard to medical, legal, or educational services, for example). Users are prompted with a similar thumbs-up or down, and then the conversation is deleted upon the feedback from the two parties. I imagine that Tarjimly can prompt translators with a system to review the helpfulness of the database (if used) and if they wish to donate a translation to the database before exiting the conversation. Then, the conversations can be deleted per usual except the key translation information can remain in the database for use by other translators across the platform.

Let me illustrate how this feature might look in practice. David, a Tarjimly translator, accepts a push notification to translate a legal advisor for Juan, a Mexican migrant seeking asylum. David asks in Spanish how Juan will spend his first six months if granted asylum in the US to which he replied, “Voy a buscar jale.” Jale. David’s never come across this word before, so he turns to the Tarjimly database of localized translation. He inputs Mexico and searches “jale,” but to no avail. He looks up the word on Google translate, all the while talking to Juan to negotiate what jale could mean in this context, and he finds a few translations on Google. David and Juan toss the word back and forth, using emphasis on certain key words in the sentence, inflecting certain syllables from their mouths, and David finds himself gesturing on this nonvideo call until they both understand each other. Jale means trabajo, which means work. He is going to look for work in the US. After the conversation, David donates this knowledge to the database. Now, others can search for the jale and have a better, more efficient, understanding of how this word is used thanks to David and the countless other translators who will no doubt come across this word.

There are limitations of the crowdsourced database that depend upon Tarjimly’s policies. For one, the minimal vetting of translators can create problems with the quality and quantity of donated translations. There will likely be many translations that are as good as the translators who choose to contribute to the database – for better or for worse. This current iteration of the proof of concept does not have a solution for vetting the quality of translations outside perhaps a rating system that translators can give to filter the best translations to the top of search results. Or perhaps priority can be given to translations from translators who have completed Tarjimly’s optional training protocols. However, without a fundamental change to the platform’s vetting of translators, the database will be dependent on how translators use the feature.

The context in which translators can give to their translations on the database is not limited to region or country. This proof of concept only mentions country, but realistically other nuances of demographic (such as religion, dialect, age and generation, region, and others) will emerge as contextualization cues in the nature of ever-changing humanitarian contexts. This proof cannot predict how these cues will emerge and evolve across Tarjimly. But giving the translators the agency to add, remove, and change these categories allows for the facilitation of translingual practice and tactical technical communication.

Discussion and conclusion

Be it brick-and-mortar or digital, humanitarian sites have much in common in that the best environment for communication allows speakers to use their full range of multilingual repertoire. I have witnessed and participated in the translingual practice and tactical technical communication that happens at humanitarian sites during my consultations and volunteering. Humanitarians are a revolving door of labor and people; there is always either someone new who needs to learn the ins and outs or a new humanitarian audience in which the nuances need to be learned. There is much pointing, gesturing, eye contact, learned words and phrases, shared understandings and misunderstandings, laughing, crying, and other forms of communication that occurs at every humanitarian site. Tarjimly is no different. This article hopefully extends our conversations on the problems with peer-to-peer translations in humanitarian circumstances; as previously stated, the humanitarian translation app is an emerging technology that needs a critical eye from our fields. We are equipped to recognize the problems that can arise from using technology to facilitate translingual practice and tactical technical communication albeit outside humanitarian circumstances. The proof of concept I propose is not the solution, but it is a start for both translinguists and tactical technical communicators to consider how to improve communication at the intersections of technology, humanitarianism, social justice, and user-advocacy.

I plan to collect data on the crowdsourced database with a local humanitarian organization before I present the proof of concept to Tarjimly. The testing will occur in a low-fidelity prototype that will operate on one server, one website, and for one humanitarian organization. The plan is to teach volunteers how the website works and encourage them to donate their translation knowledge to the database. For example, I would encourage volunteers to note their different approaches to translating depending on the demographic of the community in need. Do they need to use certain words? Certain inflections? Gestures? Do some community members respond better to certain translations? These questions, and others that will be formulated during the planning phase, facilitate the community knowledge of humanitarians to the crowdsourced database, preserving the translingual repertoire. It is important to note that these questions come from an investment in promoting translingual practice and are not currently reflected in Tarjimly’s training and protocols. It may be the case that Tarjimly becomes more receptive to the methods and methodologies from translingualism, but any speculation is beyond the scope of this article. The design of the study is still in progress, but the idea is to allow the organization to use the website for a set amount of time, periodically review the database, and then interview the volunteers on their experiences. Such a study will continue the conversations on incorporating indirect observational methods, so that our expertise in translingualism and tactical technical communication can improve the humanitarian translation app.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Health Policy Research Scholars, a program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. I also thank Angel Reyes for his help in my designing the proof of concept.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gabriel Lorenzo Aguilar

Gabriel Lorenzo Aguilar is a PhD candidate at Penn State University studying humanitarian technical communication. He has accepted a position as an Assistant Professor of Technical Writing and Professional Design at the University of Texas at Arlington to begin in Fall 2024.

Notes

1. Humanitarian audiences are often comprised of migrants, refugees, and asylees.

2. In 2016, Keith Gilyard critiqued the then current approach of translingual scholars. One such critique was that translingualists need to better “document students’ efforts” (p. 5). Some believe that translingualists did document students translingual efforts in research prior to this 2016 essay in College English. Nonetheless, translingualists did heed the critique and have published student-oriented scholarship in recent years.

3. Generally, the idea is that strategies come from higher powers in institutions (experts for example) and tactics are from those with less power to make systemic changes in their lives (e.g., de Certeau, Citation1984).

4. Other pertinent examples are G. Agboka’s (Citation2013) participatory localization of sexuopharmaceuticals for a Ghanian population and Gonzales’s (Citation2018) study of multilingual use of technology and translation.

5. A good definition of the humanitarian mission is providing resources to save lives and alleviate suffering with neutrality from political and economic objectives that can interrupt the distribution of aid to people in dire need (Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship, Citation2003).

6. During the time of writing, Tarjimly introduced different tiers of service. When I created the proof of concept, Tarjimly had two tiers: the base tier and a premium version. Both had the same features, but the premium version allowed organizations to onboard their own teams of translators and create their own hotline. Those translators still had to follow Tarjimly’s protocols. However, in late 2023, Tarjimly created three tiers: essential, premium, and platinum. Platinum functions as the old premium model. Both essential and premium have the same features, however, at the cost of $25 a month, a migrant or social worker can increase their chances of finding a translator for rare languages, filter translators by gender and experience, enable three-way calling (a feature removed from the previous version of base Tarjimly), and can opt not to record conversations at all (Tarjimly, while deleting conversations for the translator and user upon completion, still keeps the data of the conversations on their servers for some time). I anticipate that my proof of concept will be available for the essential tier, free of charge.

7. The fellow at the Health Policy Research Scholars program, Angel Reyes, helped me design the proof of concept in terms of layout.

8. There are optional training modules that can help translators be better prepared for standard interpretation practices. For example, Tarjimly can quiz a translator over questions such as “should you give your political opinion?”

References

- Acharya, K. R. (2019). Usability for social justice: Exploring the implementation of localization usability in global north technology in the context of a global south’s country. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 49(1), 6–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281617735842

- Acharya, K. R., & Dorpenyo, I. K. (2023). Translation for social justice and inclusivity in technical and professional communication: An integrative literature review. Technical Communication & Social Justice, 1(1), 41–63.

- Agboka, G. (2013). Participatory localization: A social justice approach to navigating unenfranchised/disenfranchised cultural sites. Technical Communication Quarterly, 22(1), 28–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2013.730966

- Agboka, G. Y. (2014). Decolonial methodologies: Social justice perspectives in intercultural technical communication research. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 44(3), 297–327. https://doi.org/10.2190/TW.44.3.e

- Agboka, G. Y. (2021). “Subjects” in and of research: Decolonizing oppressive rhetorical practices in technical communication research. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 51(2), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281620901484

- Aguilar, G. L. (2022a). Framing undocumented migrants as tactical technical communicators: The tactical in humanitarian technical communication. In 2022 IEEE International Professional Communication Conference (ProComm), 246–250. Limerick, Ireland. https://doi.org/10.1109/ProComm53155.2022.00051

- Aguilar, G. L. (2022b). World-traveling to redesign a map for migrant women: Humanitarian technical communication in praxis. Technical Communication, 69(3), 56–72. https://doi.org/10.55177/tc485629

- Alexander, J. J., & Edenfield, A. C. (2021). Health and wellness as resistance: Tactical folk medicine. Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(3), 241–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2021.1930181

- Baniya, S. (2022). How can technical communicators help in disaster response? Technical Communication, 69(2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.55177/tc658475

- Blommaert, J. (2013). Ethnography, superdiversity, and linguistic landscapes: Chronicles of complexity. Multilingual Matters.

- Canagarajah, S. (2013). Translingual practice: Global englishes and cosmopolitan relations. Routledge.

- Canagarajah, S. (2018a). Materializing ‘competence’: Perspectives from international STEM scholars. The Modern Language Journal, 102(2), 268–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12464

- Canagarajah, S. (2018b). Translingual practice as spatial repertoires: Expanding the paradigm beyond structuralist orientations. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx041

- Canagarajah, S., & Gao, X. (2019). Taking translingual scholarship farther. English Teaching & Learning, 43(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-019-00023-4

- Colton, J. S., & Holmes, S. (2018). A social justice theory of active equality for technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 48(1), 4–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616647803

- Colton, J. S., Holmes, S., & Walwema, J. (2017). From NoobGuides to #OpKKK: Ethics of anonymous’ tactical technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 26(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2016.1257743

- Das, M., & Tham, J. (2022). Tactical organizing: What can the r/wallstreetbets and GameStop frenzy teach us about technical communication in a networked age? Technical Communication, 69(2), 36–57. https://doi.org/10.55177/tc321987

- de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. University of California Press.

- De Los Ríos, C. V., Seltzer, K., & Molina, A. (2021). ‘Juntos somos fuertes’: Writing participatory corridos of solidarity through a critical translingual approach. Applied Linguistics, 42(6), 1070–1082. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amab026

- Ding, H. (2009). Rhetorics of alternative media in an emerging epidemic: SARS, censorship, and extra-institutional risk communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 18(4), 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572250903149548

- Getto, G., & Flanagan, S. (2022). Helping content strategy: What technical communicators can do for non-profits. Technical Communication, 69(1), 54–72. https://doi.org/10.55177/tc227091

- Gevers, J. (2018). Translingualism revisited: Language difference and hybridity in L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 40(May), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2018.04.003

- Gilyard, K. (2016). The rhetoric of translingualism. College English, 78(3), 284–289. https://doi.org/10.58680/ce201627660

- Gonzales, L. (2015). Multimodality, Translingualism, and Rhetoric Genre Studies Steven Parks, Brain Bailie. Best of the Journals in Rhetoric and Composition 2015-2016, 85–118.

- Gonzales, L. (2018). Sites of translation: What multilinguals can teach us about digital writing and rhetoric. In Sites of translation. University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv65sx95

- Gonzales, L. (2021). (Re) framing multilingual technical communication with indigenous language interpreters and translators. Technical Communication Quarterly, 31(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2021.1906453

- Gonzales, L., Lewy, R., Cuevas, E. H., & Ajiataz, V. L. G. (2022). (Re)Designing technical documentation about COVID-19 with and for indigenous communities in Gainesville, Florida, Oaxaca de Juárez, Mexico, and Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 65(1), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2022.3140568

- Gonzales, L., & Zantjer, R. (2015). Translation as a user-localization. Technical Communication, 62(4), 271–284.

- Good Humanitarian Donorship. (2003). Principles and Good Practice of Humanitarian Donorship. https://www.ghdinitiative.org/ghd/gns/principles-good-practice-of-ghd/principles-good-practice-ghd.html

- Higgins, C., & Furukawa, G. K. (2020). Localizing the transnational call center industry: Training creole speakers in Dominica to serve Pidgin speakers in Hawaiʻi. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 24(5), 613–633. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12437

- Horner, B., Lu, M. Z., Royster, J. J., & Trimbur, J. (2011). Opinion: Language difference in writing: Toward a translingual approach. College English, 73(3), 303–321. https://doi.org/10.58680/ce201113403

- Itchuaqiyaq, C. U., & Matheson, B. (2021a). Decolonial dinners: Ethical considerations of “decolonial” metaphors in TPC. Technical Communication Quarterly, 30(3), 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2021.1930180

- Itchuaqiyaq, C. U., & Matheson, B. (2021b). Decolonizing decoloniality: Considering the (mis)use of decolonial frameworks in TPC scholarship. Communication Design Quarterly Review, 9(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1145/3437000.3437002

- Jones, N. N. (2016). The technical communicator as advocate: Integrating a social justice approach in technical communication. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 46(3), 342–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281616639472

- Jordan, J. (2015). Material translingual ecologies. College English, 77(4), 364–382. https://doi.org/10.58680/ce201526923

- Kimball, M. A. (2006). Cars, culture, and tactical technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 15(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427625tcq1501_6

- Kimball, M. A. (2017). Tactical technical communication. Technical Communication Quarterly, 26(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2017.1259428

- Mays, R. E., Walton, R., & Savino, B. (2013). Emerging trends toward holistic disaster preparedness. In ISCRAM 2013 Conference Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, 764–769. Baden-Baden, Germany.

- Pacheco, M. B., Daniel, S. M., Pray, L. C., & Jimenez, R. T. (2019). Translingual practice, strategic participation, and meaning-making. Journal of Literacy Research, 51(1), 75–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X18820642

- Paciarotti, C., Piotrowicz, W. D., & Fenton, G. (2021). Humanitarian logistics and supply chain standards. Literature review and view from practice. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 11(3), 550–573. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHLSCM-11-2020-0101

- Pennycook, A. (2020). Translingual entanglements of English. World Englishes, 39(2), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12456

- Prates, M. O. R., Avelar, P. H., & Lamb, L. C. (2020). Assessing gender bias in machine translation: A case study with google translate. Neural Computing & Applications, 32(10), 6363–6381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-019-04144-6

- Roepstorff, K. (2020). A call for critical reflection on the localisation agenda in humanitarian action. Third World Quarterly, 41(2), 284–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2019.1644160

- Sarat-St. Peter, H. (2017). “Make a bomb in the kitchen of your mom”: Jihadist tactical technical communication and the everyday practice of cooking. Technical Communication Quarterly, 26(1), 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2016.1275862

- Shao, J., Wang, X., Liang, C., & Holguín-Veras, J. (2020). Research progress on deprivation costs in humanitarian logistics. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 42, 101343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101343

- Sun, Y., & Ge, L. (2021). Enactment of a translingual approach to writing. TESOL Quarterly, 55(2), 398–426. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.609

- Tarjimly. (n.d.). Tarjimly. https://www.tarjimly.org/

- Tomasini, R. M., & Van Wassenhove, L. N. (2009a). From preparedness to partnerships: Case study research on humanitarian logistics. International Transactions in Operational Research, 16(5), 549–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3995.2009.00697.x

- Tomasini, R. M., & Van Wassenhove, L. N. (2009b). Humanitarian logistics. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending damage: A letter to communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15

- Veeramoothoo, S. (2020). Social justice and the portrayal of migrants in international organization for migration’s world migration reports. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 52(1), 57–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047281620953377

- Walton, R., Mays, R. E., & Haselkorn, M. (2016). Enacting humanitarian culture: How technical communication facilitates successful humanitarian work. Technical Communication, 63(2), 85–100.

- Walwema, J., Colton, J. S., & Holmes, S. (2022). Introduction to special issue on 21st-century ethics in technical communication: Ethics and the social justice movement in technical and professional communication. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 36(3), 105065192210876. https://doi.org/10.1177/10506519221087694

Appendix

Tarjimly Policies Regarding Privacy as of August 2023

Maintain confidentiality and privacy at all times.

For safety, don’t translate outside of the Tarjimly app.

Focus on Interpreting and not Advocacy.

HIPPA compliance

Don’t disclose PII

Use physical and technical safeguards such as phone passwords.

Implement reasonable security measures to protect PII on devices.