ABSTRACT

Presence of a steam pinnace at Lyness, Orkney Islands, was first documented in United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO) records by letter from a local scallop diver. Historic Environment Scotland (HES) tasked ORCA and Sula Diving Ltd to document this wreck during the Scapa Flow 2013 Marine Archaeology Survey. Side scan sonar and oral history provided initial clues to the identity. Reference to archival data and the Pinnace 199 renovation project (Portsmouth Historic Shipyard) enabled confirmation of its identity and understanding of how the vessel came to lie on the seabed off Rinnigal Pier. Photogrammetry revealed preservation status and during biological surveys two species of national conservation importance were recorded.

RESUMEN

La presencia de una pinaza a vapor en Lyness, Islas Orcadas, fue documentada por primera vez en los registros de la Oficina Hidrográfica del Reino Unido (UKHO) a través de una carta de un buzo de vieiras local. La oficina Ambiente Histórico de Escocia (HES) solicitó a ORCA y Sula Diving Ltd que documentaran este pecio durante el Estudio de Arqueología Marina de Scapa Flow de 2013. El sonar de barrido lateral y la historia oral proporcionaron las primeras pistas para identificarlo. La referencia a datos de archivo y al proyecto de renovación del Pinnace 199 (Astillero Histórico de Portsmouth) permitió confirmar su identidad y comprender cómo esta embarcación llegó a yacer en el lecho marino frente al muelle de Rinnigal. La fotogrametría reveló el estado de preservación y durante prospecciones biológicas se registraron dos especies de importancia nacional para la conservación.

摘要

英国海道测量局 (UKHO) 的记录是最早记载奥克尼群岛利内斯存在一艘蒸汽艇的信息。该记录是当地一名扇贝潜水员通过信件提供的。苏格兰历史环境局 (HES) 委托奥克尼考古研究中心和苏拉潜水有限公司在 2013 年斯卡帕湾海洋考古调查期间详细记录该沉船。侧扫声纳和口述历史提供了识别该船身份的初步线索。参考档案数据和舰载艇 199 改造项目(朴茨茅斯历史造船厂),确认了其身份并了解到该船如何沉没于林尼格尔码头附近的海床上。摄影测量揭示了沉船的保护状况,并且在生物调查中还记录下两个具有国家保护意义的物种。

摘要

英國海道測量局 (UKHO) 的記錄是最早記載奧克尼群島利內斯存在一艘蒸汽艇的信息。該記錄是當地一名扇貝潛水員通過信件提供的。蘇格蘭歷史環境局 (HES) 委托奧克尼考古研究中心和蘇拉潛水有限公司在 2013 年斯卡帕灣海洋考古調查期間詳細記錄該沉船。側掃聲納和口述歷史提供了識別該船身份的初步線索。參考檔案數據和艦載艇 199 改造項目(樸茨茅斯歷史造船廠),確認了其身份並了解到該船如何沉沒於林尼格爾碼頭附近的海床上。攝影測量揭示了沈船的保護狀況,並且在生物調查中還記錄下兩個具有國家保護意義的物種。

Background and Introduction

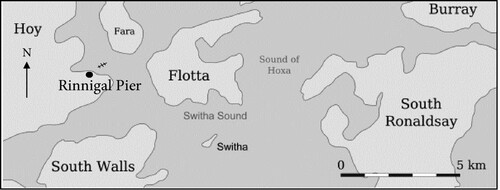

The first known documentation of a Royal Navy steam pinnace at Lyness, Orkney Islands, Scotland, is in the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO) record wreck card number 1119, made in 1982. In this record it is stated that details of the pinnace were provided to them by letter from Mr John Besant, a local scallop diver living in Lyness, Hoy (see map of the location in ). In the record entry John Besant wrote that it was a Royal Navy pinnace because there was a bell on the wreck, which had a Royal Navy crow’s foot inscription mark on it. It is important to note that pinnaces were significant vessels in their time, often used to ferry officials to and from larger vessels (Stapleton, Citation1980).

Figure 1. Map to indicate the location of the Rinnigal Pinnace, close to the Rinnigal Pier, Scapa Flow, Orkney Islands (Authors).

In 2013, Historic Environment Scotland commissioned ORCA and Sula Diving Ltd to survey a number of archaeological sites in Scapa Flow, including wreck card number 1119. The survey involved a combination of side scan sonar and diver surveys (Canmore ID, 102327, Citationn.d.). The results from the survey work are given in section 5.4, pg. 61 of the Scapa Flow 2013 Marine Archaeology Project survey report (Christie et al., Citation2013). The project aimed to establish or confirm the identification, extent of survival, character and condition of around 28 known but mostly poorly recorded First and Second World War wreck sites, eight salvage sites, several sites thought to be associated with Second World War Boom Defences, and a limited sample of geophysical features identified in previous studies (Scapa Flow Historic Wrecks, Citationn.d.).

Two key questions arose from the 2013 survey for HES: firstly, what was the identity of this steam pinnace, and secondly how did it come to be in its current position off the Rinnigal Pier as a wreck in Scapa Flow? As part of the investigation, the team documented the key features that remain of the wreck itself and were able to collect data about the presence of species and habitats of nature conservation significance living in close association with the wreckage and its immediate environment.

The approach to the study involved detailed archival investigation to further validate the UKHO report. A key artefact from the site was also investigated. Local diver, John Besant, who made the original report to UKHO was traced, and agreed to take part in an interview. A team of SCUBA divers undertook surveys of the wreck itself using photography and videography/photogrammetry methods to create a baseline of the wreck at this point in time. A standardized marine life survey method was applied to document the flora and fauna both on and in close proximity to the wreck. This information was used to explore and raise awareness of the role that the wreck now plays as a substrate for species and habitats of biodiversity significance.

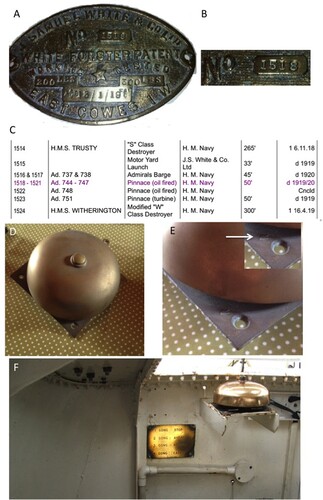

Artefact Investigation

In addition to the UKHO report, an anonymous donation of a photograph of a brass boilerplate (A) salvaged from the wreck in 1997–98 became available to the authors; here, the ship’s number can clearly be seen as 1518 (B). It also shows that the place of manufacture was at the J. Samuel White and Co Ltd shipyard at East Cowes in the Isle of Wight. It was possible to track down a copy of the yard list by making contact with the archive of the Isle of Wight Museum. The copy of the yard list (C) shows that four steam pinnaces were built by the yard and delivered to the Royal Navy; their numbers were 1518, 1519, 1520 and 1521, respectively (no archive number available). From the yard list it is possible to see that ship builders’ number 1518 corresponds to the ship named Steam Pinnace 744 (SP 744) and that it was delivered to H.M. Navy in 1919/20. It was a 50-foot-long vessel and was oil-fired. This provided the answer to the immediate question regarding the possible identity of the steam pinnace on the seabed off Lyness. This finding led to further questions regarding the history of how the pinnace came to be lying in its current position on the seabed off the Rinnigal Pier.

Figure 2. (A) Boilerplate from the wreck at Rinnigall pier. (B) Close up showing the number from the Boilerplate. (C) Yardlist. (D) Photograph of the bell (engine order gong). (E) Close up of the bell (engine order gong) indicating the crows foot (inset). (F) Engine Order Gong photographed in situ on the restored SP.199 at Portsmouth Historic Shipyard (photo credits: Frank Fowler).

Interviews

Prior to the interview with John Besant, some of the local dive boat skippers were informally interviewed in an attempt to gain more insight about the wreck. Enquiries resulted in conflicting anecdotal evidence of how the pinnace came to be there indicating that it had largely fallen from common memory.

The first diver to visit the site was John Besant, and an interview was arranged by Laken Hives and took place on 6 July 2017, at his house. John shared interesting information regarding the salvage of the vessel. During the interview in John’s kitchen, he sketched what the steam pinnace looked like when he first discovered it. He said that the wreck was ‘mostly intact and upside-down, you could see the wheel underneath’. The bow, however, appeared to be damaged, but he wasn’t too sure. John said that he had attempted to purchase the wreck, but within a few weeks other local salvage divers had stripped off a great deal. Over four dives on the wreck, he noticed the change and he also recovered a bell with a Royal Navy crows foot emblem on one corner. The fact that the bell was still in place when John dived on the wreck suggested that the pinnace had remained untouched before John discovered her on his scallop dives off Rinnigal Pier. John still had the bell in his possession, and kindly allowed it to be photographed (D,E). If the pinnace had been known prior to John’s discovery, it could easily have been recovered from that location and would have been clearly documented in the post-war salvage Metal Industries Days Afloat logs (D59/1), which despite careful searching, nothing of relevance was found relating to the wreck which would seem to corroborate John’s information about it being found first by him on one of his scallop dives.

Archival Investigation

The geographical position of the wrecked pinnace (indicated in ) provided a range of hypotheses to pursue. The wreck lies in shallow water, 14–16 m deep – well within the depth of Second World War salvage divers. It lies close to Lyness, suggesting that it could have been lost nearby on a mooring or as indicated by local skippers, hit by another vessel in fog in transit or stationary.

Aside from the interviews, four primary sources of documentation were used. These are listed below. The first two documents were accessed through Kevin Heath, local wreck historian (Sula Diving Ltd), at the start of the archival investigation. The remaining documents were accessed further on in the investigation from the National Archive at Kew:

H Bullen’s Diver log number 8 donated from a private collection belonging to Colin Bullen

Days Afloat logs from Metal Industries ref: D59/1 Metal Industries logs from July 1940-December 1943 (Documents held in the Kirkwall Archive)

Operations Record Books (ORB) logs from the Balloon Barrage base at Lyness which was moved to St Mary’s (Documents held in The National Archive at Kew)

3.1. AIR 27/2297 Squadron 950 1940–1942

3.2 AIR 27/2297 Squadron 950 1943–1944

3.3 AIR 27/2311 Squadron 960 1940–1944 (Documents held in The National Archive at Kew)

The fleet base at Scapa Flow 1937-1946 ADM 116/5790, a written history of the military and salvage activities occurring over the nine years, pre, during and post-Second World War (Documents held in The National Archive at Kew)

The proximity of the wreck to Rinnigal Pier (see ) presented another possible lead. Construction on the pier began in August 1940 by Arrol & Co. from fabricated steel and was completed in October 1941 (ADM 116/5790, 1954). The pier was used by the RAF to store hydrogen tanks shipped from Rosyth, Invergordon and Aberdeen naval units until the hydrogen plant at Rinnigal was fully operational, towards the end of the war in 1944 (ADM 116/5790, 1954). The hydrogen was used to fill barrage balloons at the RAF squadrons 950 and 960 bases in Lyness (ADM 116/5790, 1954). Squadron 950 was then transferred to St Mary’s (AIR 13/108 -P.112A C643798, 1942).

Upon reading and cross-referencing the logs for 8 July 1942 (AIR 13/108 -P.112A C643798, 1942), there were no mentions of pinnaces or picket boats made up to one month prior. For the time being, the trail went cold and so other possibilities were examined through the diver logs belonging to H. Bullen, especially Logbook number 8. These diver logs spanned 1941–43 and recorded salvage dives across Scapa Flow. From careful scrutiny of these logs, two clues appeared. An entry on 24 November 1941 read ‘H.M.S. Ramillies, recovering pinnace – 4 tides’ (Bullen, Citation1941–Citation1943, p. 11; suggesting a shallow wreck site due to four tides being dived in one day, complementing the possibility of SP 744). On 11 December 1941, the H.M.S Ramillies pinnace had a further three dives across three tides (Bullen, Citation1941–Citation1943, p. 14). Cross-referencing the above dates with the photographed Metal Industries Days Afloat logs (logbook ADM 53/114938; held in the Orkney Library Archive), provided a monthly summary of salvage activities and company records. Photograph P2090018, documenting the Divers Timesheet November 1941, confirmed that H. Bullen had worked for Metal Industries salvaging: ‘Ramillies picket boat’ on 24 and 25 November. The Ramillies pinnace was, therefore, considered a healthy lead, due to the numerous dives carried out and two documents complimenting salvage activities on a pinnace.

While examining the H. Bullen and Days Afloat logs, another lead became apparent in an entry, stating: ‘searching for B.D. pinnace 4 tides’, recorded on 25 January 1943 (Bullen, Citation1941–Citation1943, pp. 14–15; confirmed on P2090032 Days Afloat logs). On 27 January, H. Bullen recorded in his Logbook number 8 the ‘Slinging of B.D pinnace 4 tides’, suggesting that the wreck had been found, once again in shallow water and was in the process of being slung to be lifted. ‘B.D’ is short for ‘Boom Defence’, the base of which was H.M.S Pomona. Unfortunately, no logs could be acquired for H.M.S Pomona to see if the base had lost a pinnace at that time.

The dates of these pinnace searches and supposed recovery provided a lead to possible timelines. The Ramillies pinnace must have been lost before November 1941 or a month or two earlier in the year. Salvage was quick and resources in high demand. The Ramillies pinnace did not appear in the Bullen logs after the entry from 11 December 1941.

The Days Afloat logs recorded the presence of H.M.S Dunluce Castle as does ADM 116/5790, 1954; her appearance at Lyness was as a fleet mail and accommodation vessel. Returning to these logs and cross-referencing both the Boom Defence and Ramillies pinnace salvage log dates suggested that Dunluce Castle was present at Lyness and could have witnessed a sinking vessel. The logs for January and February 1943 would be required to investigate the lead further. These logs for both Ramillies and Dunluce Castle were located and then investigated at the National Archive at Kew.

During this time, the investigation also followed another line of enquiry as suggested by Bob Anderson. Steam Pinnace 199 is a fully restored, operational Steam Pinnace hosted at the National Museum of the Royal Navy (NMRN) in Portsmouth (SP199, Citationn.d.). It was built at the same J. Samuel Whites Yard Ltd as SP 744, but prior to the First World War, in 1911. After a brief email with Martin Marks of the Steam Pinnace 199 project, he forwarded the correspondence on to Frank Fowler, Chief Engineer of Steam Pinnace 199 and a naval historian. By supplying the photograph of the boilerplate and the information from the Isle of Wight Heritage Service, Frank Fowler was able to investigate further admiralty archives held at the Admiralty Library in Portsmouth. The photograph of the bell was also sent to Frank Fowler, who identified it as an ‘engine order gong’.

‘The bane of my life as an engineer on board the pinnace! It is fitted to the casing at the aft end of the engine room, just below the skylight, and operated by the Cox’n via a pull rod on the other side of the casing next to his steering wheel. Looking above the bell, you can just see the brass steering wheel’ (Frank Fowler, pers. com.). To the side of the bell would have been an inlaid brass plate with a list of instructions, as is also the case on SP 199. (F)

This evidence provided a vital breakthrough in the investigation and made redundant the need to follow the Ramillies and B.D. pinnace leads any further for this investigation. However, this did raise more questions. The date of the sinking, to be ‘lost in bad weather’ in July, seemed suspicious. To lose a vessel at Lyness in bad weather in mid-summer would be an achievement even by Orkney standards given that the geographic location of Lyness is sheltered on all sides of the compass by the coast of several islands in close proximity. There is a very limited wave fetch at this site, and it is no surprise that it is used as a safe harbour for this reason. A revisit to the ORB logs and the dates of the reported sinking for July examined all ‘calm’ or ‘slight’ weather reports with no aggressive summer storms or fronts. Had the pinnace sunk on the date written in the ledger, or was the fate of SP 744 just recorded at a later date?

To investigate further, a search into the background of its most recent parent ship was required. This was done through investigation of the information in the Naval Archive website Naval-History.net, a website documenting all significant movements of battleships and other naval history. The H.M.S Royal Sovereign entry provided exciting results: on 4 September 1939, H.M.S. Royal Sovereign departed Scapa Flow with H.M.S Royal Oak, escorted by two destroyers. At 17:09 on 6 September the group returned to Scapa Flow. Royal Sovereign then remained in Scapa Flow until 23 September when it departed for Portsmouth for a refit. By 23 September it arrived safely in Portsmouth, had a partial refit and headed west, where it frequently moved between Portsmouth, Virginia, Halifax, Bermuda and Durban. It did not return to Scapa Flow until October 1941. The log from September 1939 for H.M.S. Royal Sovereign (ADM 53/110312) can be found in the Royal Navy Archive where Lt Jen Smith, RN, kindly searched through the log for anything suggesting details of a pinnace being defective. The search found an entry for Saturday, 16 September 1939 stating: ‘1st picket boat towed to Lyness for disposal’ (HMS Royal Sovereign Log, Citation1915–Citation1949).

The dates from SP 744’s ledger suggest that it was lying on the seabed before the return of Royal Sovereign to Scapa Flow. This hinted that it was replaced by another pinnace and never returned on board its parent ship. Further evidence in the section ‘2.11.1939 Reported unserviceable’ after landing at Lyness to be sent to Devonport for refit suggests it was left behind at Lyness and sank sometime around 23 September 1939 and 23 July 1941.

SP 744’s resting place on the seabed lies very close to Rinnigal Pier; however, it would not have been tied up there. It is therefore possible that SP 744 was left on a mooring close by as with many of the base fleet ships and storage ships in Scapa Flow.

Side Scan Sonar Survey

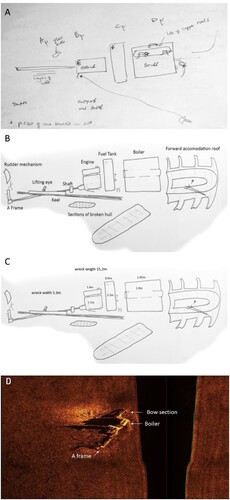

As part of the Scapa Flow Historic Wrecks 2013 survey (Scapa Flow, Citationn.d.), a side scan sonar survey of the wreck of the steam pinnace off Rinnigal Pier was conducted by the team at Sula Diving Ltd. The image generated from the side scan showed a 12 m-long contact standing approximately 2 m proud of the seabed. The remains were oriented south-southwest to north-northeast with the bow to the northeast. Features that can be recognized in the side scan include the boiler, the A frame to which the rudder would have been attached and also the bow (see D).

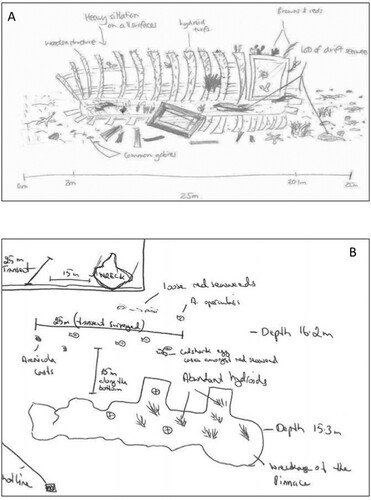

Figure 3. (A) Initial sketch map of the site showing datum points. (B) Site map showing key features of the wreck identified. (C) Site map with measurements of key features incorporated (Bob Anderson and Joanne Porter). (D) Side scan sonar image of the Rinnigal Steam pinnace provided by Sula Diving Ltd. This image indicates key features of the wreck such as the boiler, the A frame and the bow section. It also shows the biophysical context of the site; the substrate around the wreck comprises muddy sand (Kevin Heath).

In-situ Diving Surveys of the Wreck and Its Local Environment

On 9 May 2014, a team of eight divers from Heriot Watt University, Orkney Islands Council and Sula Diving Ltd surveyed the site. Two members of that dive team returned on 11 November 2014 together with a third diver, to conduct some additional photogrammetry image acquisition to try to improve on the imagery from a bow section which was complex and difficult to analyse in the rendering of the three-dimensional model.

At the time of survey, the pinnace lay on its port side in 14 m depth water (MLWS) just off the ruined Rinnigal Pier, with the bow pointing in a north-northeast direction. The Scapa Flow 2013 Marine Archaeology Project (Christie et al., Citation2013) lists the site as 58 49.71N 003 10.94W. In our survey, a revised position of the pinnace at 58 49.716N 003 10.927W was recorded; this position was taken from directly above the aft end of the propeller shaft.

Objectives of the diving surveys were to (1) record, measure and image the remaining structures left on the seabed, (2) record the flora and fauna directly supported by the pinnace remains and (3) record the flora and fauna of the seabed adjacent to the pinnace for comparison. On the first visit to the site, divers drew up a crude site sketch map (A). On the later visit key features of the wreck were measured directly to improve the accuracy of the measurements taken and to refine the information about the orientation of features at the site.

The points A, B, C, D were datum points marked using steel pins about 2 ft long that were hammered into the seabed. These datum points were positioned either side of the wreck location approximately 1 m away from the wreck itself and at intervals along the port and starboard sides. Measurements were taken between each of the datum points and to key features on the wreck to help allow for accurate diagrams of the features to be made with scale included. The points E, F, G, H were prominent points on the wreckage. With the aid of a composite photograph and tracing around the outline, a more refined map was produced showing the layout of the site and some key features (B). Measurements of the key features were made (C). On the left of C is the rudder stock. There is a strong possibility that the rudder and stock itself were a single piece of valuable non-ferrous metal such as brass. There are equivalent examples of brass rudders in Lyness Museum. This would have made it attractive to any salvage effort and the presumption is that this is why the rudder cannot be located on site. The ‘tube’ within which the stock would have been mounted remains and is marked in the figure.

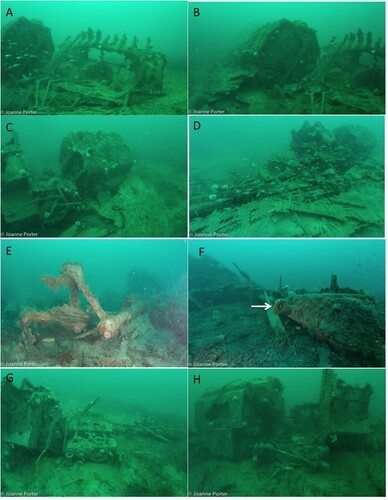

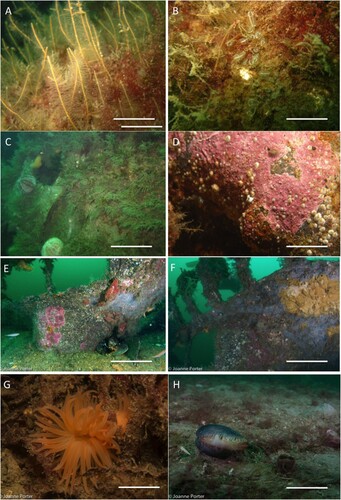

To augment the sketch maps a series of wide-angle images were taken to illustrate the wreck features looking from different points around the site (A–G). Wide-angle images were taken using a Nikon D7100 SLR camera with a Tokina 10–17 mm Fisheye lens housed inside a Seacam Silver Housing. Inon Z240 strobes were used to provide lighting. A combination of the sketch maps and the photographs allowed observations to made on the condition of the wreck and key features.

Figure 4. (A) View of the bow section with boiler in background, from off starboard side. B) Closer view of the boiler from starboard side. (C) View of the back of the boiler and the fallen away hull plates, taken from starboard side. (D) Closer view of the midships section showing remains of the double diagonal hull plates. (E) View of the propeller shaft, a frame and hub of the propeller (propeller was salvaged), taken from the stern. (F) View of the lifting eye, one of two used to bring the pinnace back on board the mother vessel when not being used, taken from the stern looking along the portside. (G) View of the midships area of portside showing the propeller shaft meeting the engine block (H) View from the portside of the area connecting between the engine, fuel tank; the boiler (now fallen over) is positioned towards the left of the image and has a large hole in the outer casing (Authors).

Just below the stock and not marked on the diagram (B) are the two rubbing strips, both brass, that would have provided protection where the transom stern met the hull. These items were obscured by weed and therefore not easy to pick out in photographs.

At the bow section of the wreck (A, B), remains are dominated by the distinctive struts that may have formed part of the roof of the forward accommodation. Moving around the wreck down the starboard side the boiler is a key feature, now fallen over to one side (C, D). Hull sections have fallen down to the seabed and now lie mainly on the north side of the wreck. The diagonal construction of the hull planking is evident; there are still a few frames visible. However, there is no obvious sight of the membrane that would have lined the inner space between the layers of hull planks.

The area of the bilges where the shaft passed through the hull was filled with concrete, which remains. The lifting eye and stern gland for the shaft are set into this concrete. The shaft still runs from the back of the engine through the stern gland to the supporting A frame which would have been mounted on the hull. The propeller has been removed and the steel shaft cut through just aft of the A frame (E, F). G illustrates the essence of the pinnace: the compact design with the close proximity of the boiler, fuel tank and engine block is still evident. The engine has fallen onto its port side and has broken the mounting bolts. It is formed from two enclosed sections. Firstly, the top smaller section is the part that would have housed the pistons and there is an obvious steam intake pipe that has broken at the flange. Secondly, the main engine housing the crank and con-rods is under the cylinder head. There are corroded holes in the block that allow sight of the internal crank and con-rods. Aft of the engine on the shaft is a conical shape that could possibly be the flywheel (it seems slightly too small for this function but there is nothing else evident that would fulfil the role). Halfway between the engine and the stern gland is a ‘box’ of unknown function. Interpretation is that it could either be a reduction gear or the reversing gear box. The keel runs the length of the wreck; remains of it are prominent and distinctive.

Photomosaic Techniques

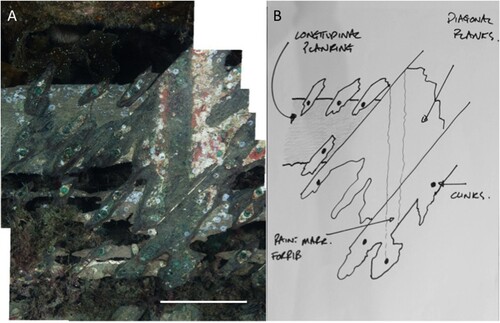

Trials were conducted using a 60 mm Micronikkor macro lens to record a series of overlapping photographs, which could then be stitched together into a mosaic using Adobe Photoshop software. This is a rectilinear lens meaning that there is no distortion to correct. However, the viewing angle is quite small at the best working distance and so a large number of images are required to ensure full coverage of the target area.

A composite of 12 photographs of a section of hull taken with a 60 mm lens is shown in A. This mosaic clearly demonstrates some characteristic features.

Figure 5. (A) A photomosaic of 12 stitched images to show the double diagonal planking construction of the hull (Scale Bar = 5 cm). (B) A sketch of the photomosaic image of a close-up section of the hull with annotations of the key features relating to the distinctive type of construction used (Bob Anderson).

The hull construction of the pinnace is unusual and distinctive. In order to understand the construction, a brief explanation is required. When the boat was built, a keel would have been laid down. From the keel, frame-like structures would have been attached to give the shape a rounded, hydrodynamic form and internal volume. A row of planks would have been run from bow to stern on the frames and attached running at approximately 45 degrees to the floor. This initial hull would then have been covered with two layers of calico. A further layer of planks would have been adhered to the calico using marine adhesive and running parallel to the ground. Nails known as clinks would have been passed through the planks and frames and then both ends hammered flat to form a rivet. This form of hull absorbs the impact of knocks and bumps well and provides a relatively lightweight but robust construction (Stapleton, 1980). In addition, the hull stays watertight despite the boat remaining out of the water for considerable periods of time including in hot weather, which would have caused planks to shrink and thus leak in other forms of construction. A downside of this type of construction is that when damaged, it is complicated both to find and to repair (Stapleton, 1980). The two layers of planking and the remains of the clinks (nails) are evident in the photomosaic (A) and also in the diagram (B). The old paint marks indicate that a frame would have been attached at this point but has subsequently been lost. These features are key indicators helping to target a specific identity for the wreck and correlate with the ship builder’s information. There was no evidence of the calico membrane.

None of the individual photos demonstrate these characteristics as clearly as the composite. At this scale of feature, a photo mosaic is clearly more beneficial than individual photos.

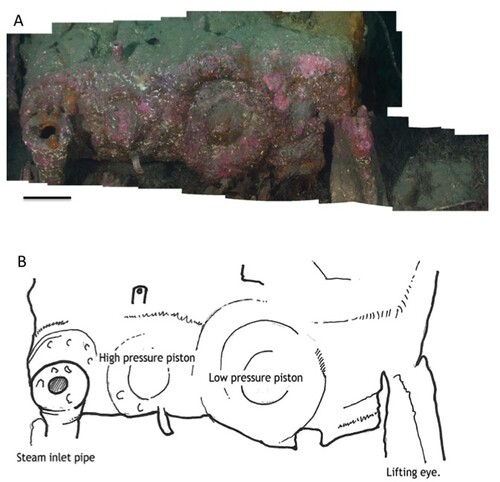

Engine Block Mosaic Example

A sequence of photos was taken of the engine block. A total of 47 images were aligned manually before automatic stitching within Adobe Photoshop (A). Key features that can be seen include the steam inlet pipe, the high-pressure piston, the low-pressure piston and a lifting eye as shown in the interpretive diagram (B).

Figure 6. (A) A photomosaic to illustrate the top of the cylinder block on the engine (Scale Bar = 8 cm). (B) In this diagram, key features of the engine block are identified to support interpretation of the photomosaic of the top of the engine block (Authors).

A shows a plan style diagram of a steam pinnace (Stapleton, 1980) which illustrates the key features of this type of vessel. In B a photograph of the restored Steam Pinnace 199 at Portsmouth illustrates an excellent example of what a working pinnace looks like.

Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of the Wreck Site Using Photogrammetry

As the project developed, new documentation techniques were rapidly becoming available to the dive team. An additional site visit by three members of the dive team on rebreather units allowed the window of bottom time to be increased. This in turn meant that more time could be spent trialling more complex techniques, making it possible to produce a three-dimensional reconstruction of the wreck site. The set up used for this was the same as for the wide-angle still images but with exchanging the use of the Inon Z240 Strobes for video lights and setting the camera in video mode. Additional lighting was supplied by a separate 26,000 lumen Orca Seawolf light. This was held by a second diver swimming along in formation with the main videographer. This technique involves the dive team having a clear plan of how they are going to film, excellent buoyancy skills, and clear coordination to keep the formation in place. The entire wreck was filmed by swimming over its length and breadth, with each swath overlapped by 50%. Video footage was then processed through Frameshots software to extract a still image every 0.5 s. These extracted images were uploaded into Agisoft software to generate the final photogrammetry model. This model was then uploaded for display onto the Sketchfab viewer website (https://skfb.ly/UE6S).

Natural Heritage Marine Life Surveys on and Adjacent to the Wreck

Two teams of divers focused on (i) surveys of the wreck itself and (ii) adjacent to the wreck using Marine Nature Conservation Review Phase 2 survey and Seasearch Surveyor level recording forms. Sketches were made of the key habitats and species. In order to achieve successful survey data collection, each of the two dive teams completed two dives.

Divers recorded species presence and abundance (using the SACFOR scale) 1 m either side of a 25 m-transect tape laid along the top of the wreck from bow to stern. From the in-situ records made by the divers, biotope codes were assigned where possible, following the Joint Nature Conservancy Council Marine Nature Conservation Review system. The biotope code and name allow the placing of a specific combination of habitat type and species into a nationally-recognized classification scheme (Connor et al., Citation2004).

The wreckage itself lies on a seabed comprising muddy sand and so good buoyancy skills were needed to keep disturbance of silt to a minimum during the diving operations. Rebecca Grieve and Hamish Mair conducted the survey of the wreck itself (A). There was heavy siltation in places in contrast with other areas which were cleaner where the tide swept over the top of the wreck. As a result, species with different environmental requirements were observed in these different niches. A dense turf comprising hydroid colonies, soft corals and red seaweeds coated the surface of the pinnace. Here dominant species were the tall hydroids Nemertesia ramosa and Halecium halecinum with patches of the soft coral, dead men’s fingers, Alcyonium digitatum (Wood, Citation2018). There were also abundant edible urchins, Echinus esculentus, acting as modifiers to the community through their grazing activity. This type of community is indicative of conditions where hard substrates are available in combination with a slight tidal flow, sufficient to supply food particles to the hydroids and to ensure that they do not get clogged with silt particles. The growth of red algae indicates that there is sufficient light penetration through the water column and clarity of water for algae to photosynthesize at this depth (14 m, MLWS).

Figure 8. (A) Underwater sketch of the marine life and habitats of the wreck following MNCR Phase 2 method by diver Rebecca Grieve (RG) (B) Sketch by Jenni Kakkonen (JK) illustrating the surveyed area adjacent to the wreck.

It was not possible to allocate a biotope (Connor et al., Citation2004) to this particular wreck’s associated assemblage as the biotope system has very few biotopes designated for wreck sites; none of the available ones matched with the characteristics observed. Key observations noted are that the wreck is in the infralittoral zone, it is in an area sheltered from wave exposure and it experiences a tidal stream <1 knot. The main substrates are metal and wood. The dominant species recorded included pink encrusting algae, hydroids Nemertesia ramosa and Halecium halecinum and red algae including Brongniartella byssoides. Seasquirts present included Ascidia mentula and Clavellina lepadiformis (A–D).

Figure 9. (A) Clumps of the branching hydroid Nemertesia ramosa on the upper surfaces of the wreck (RG) Scale Bar = 5 cm. (B) Clumps of the light bulb sea squirt Clavellina lepadiformis growing on the vertical surfaces of the wreck (RG) Scale Bar = 5 cm. (C) Upper surface of the wreck with abundant clumps of the Herringbone hydroid Halecium halecinum, and grazing edible sea urchins, Echinus esculentus. Occasional patches of Dead Men’s Fingers, Alcyonium digitatum were also present and are indicative of areas where current flows more strongly over the wreck surface. There is a dense understory of short red algal turf, indicating that light levels are sufficient for some seasonal algal growth (RG) Scale bar = 20 cm. (D) Encrusting pink algae growing over the surface of the wreck, with abundant barnacles and rare occurrence of the china limpet Tectura testudinalis (RG) Scale Bar = 8 cm. (E) A European lobster (Hommarus gammarus) using the remains of the roof aft accommodation as a home. Other fauna and flora encrusting the wreckage include the solitary ascidian Ascidia mentula, pink encrusting algae and the white fur-like polyps of the sessile life stage of the moon jellyfish Aurelia aurita. Scale Bar = 25 cm. (F) A large colony of the yellow encrusting sponge Myxilla incrustans, a plumose anemone Metridium senile, Deadman’s finger Alcyonium digitatum and encrusting pink algae present on another section of the remains of the roof of the aft accommodation. Scale bar = 25 cm. (G) A flame shell (Limaria hians) nestling in amongst a pile of the red seaweed Phyllophora crispa. Scale Bar = 3 cm. (H) The filter feeding bivalve mollusc Ocean Quahog (Arctica islandica) and the actively feeding siphon of Mya truncata, a burrowing bivalve mollusc, photographed in the area adjacent to the wreck of Steam Pinnace 744. Scale Bar = 6 cm (Joanne Porter).

Divers Bill Sanderson and Jenni Kakkonen conducted an MNCR Phase 2 survey (JNCC, Citation2021) adjacent to the pinnace. The position of the transect line was 15 m distant and parallel to the wreck on the east side, at a depth of 16.4 m (B). This survey revealed a substrate of muddy sand interspersed with patches of shell gravel, and an associated fauna of burrowing bivalves and Pomatoschistus sp. (Gobies). Abundant piles of red algae were found integrated into the surface of the seabed; this is highly unusual considering that the seabed was composed of muddy sand and usually the algae would be attached to a hard surface. Occasional pieces of coal were embedded in the sediment. One of the biotopes that could be allocated from the survey is ‘SS.SMp.KSwSS.Pcri’; the description is ‘Loose-lying mats of Phyllophora crispa on infralittoral muddy sediment’. Further biotopes include ‘Infralittoral sandy mud with unattached red algae, large burrowing bivalves and burrowing crustaceans with worm casts’. Biotopes were allocated using the diver in-situ survey notes supported by photographic evidence: lower infralittoral slightly sandy mud with scattered wreck debris and 40% unattached, mostly red algae that look seasonally ropey but probably living. Common large infaunal bivalves such as Mya truncata and notably Arctica islandica (Rare) (H). Common crustacean burrows (U-shaped) and scallops and occasional worm casts were observed. Closer observation of the piles of red seaweed on later dives revealed that some of these piles were in fact nests of the Flame shell (Limaria hians) (G). The biotope code for Flame shell nests is ‘SS.SMx.IMx.Lim’: ‘Limaria hians beds in tide-swept sublittoral muddy mixed sediment’. While the nests observed here do not conform exactly to the JNCC (Citation2021) description, there is reasonable overlap in the key features. This finding represents an important record of a species of national conservation importance. Arctica islandica (Ocean quahog) and Flame shells are both designated as Priority Marine Species for Scottish waters (Tyler-Walters et al., Citation2016).

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to find out the identity of the wreck lying on the seabed off the Rinnigal Pier, Lyness. Supporting objectives were to investigate available resources to piece together how it came to be there, to document its current condition and to understand its influence on the surrounding environment today. As a result of investigations in archives, analysis of relevant artefactual material and additional site surveys, the aim and objectives were largely met.

Establishment of the Identity of the SP 744

Regarding the identity of the wreck, several avenues were used in archival research, artefact exploration and diver interview to collate and synthesize relevant information. The interview with John Besant and his provision of a photo of the bell, combined with the information taken from the boilerplate and then from the associated yard list made it clear that we were looking at SP 744. Features observed and documented by divers regarding the engine order gong and the double diagonal construction of the planking are consistent with it being a Royal Navy steam pinnace boat.

Understanding of the Final Resting Place of SP 744

Understanding how SP 744 came to lie in its current position off Rinnigal Pier was difficult to ascertain. Eventually pieces of information revealed by disparate lines of investigation allowed the synthesis of details which enabled a breakthrough providing evidence to suggest that it had belonged to the vessel Royal Sovereign and was damaged during operations in Scapa Flow. As a consequence of the damage, it was brought to Lyness when Royal Sovereign went south for its refit in late September 1939. The trail of archival evidence then goes cold, and so the information from the recent SCUBA surveys on the current condition of the wreck seems to be the most reliable source of evidence. The observation and documentation of the remaining wreck structures in place and the layout of the site show clearly that some salvaging has taken place, for example there is no propeller or rudder. The characteristic features of the wreck, though, are largely where they would be expected, so the possibility of any kind of explosion can be ruled out. The structure at the bow area is much less intact than other parts of the wreck, possibly suggesting that there may have been some kind of collision leading to the sinking of the vessel at its mooring. The timing of the sinking of the wreck is placed, on current available evidence, to have occurred sometime between 1939 and 1941.

Documentation of the Physical Wreck Structure and Condition

The diving team involved a core of professional scientific divers trained to use the JNCC SACFOR methods as well as the citizen science nationally recognized Seasearch scheme (Seasearch, Citationn.d.). Photogrammetry was a new technique for the core team to learn and they largely worked out the relevant methods by trial and error. Lessons learnt in the photogrammetry technique included the importance of using flat, even lighting, slow recording speed and precise buoyancy when diving. The remains of the bow area consisted of a series of metal frames which looked superficially quite similar to each other. When analysing the images from the video footage, it was difficult to completely reconstruct the bow of the wreck, despite several attempts. This is an area which would merit further development work going forwards with this type of technology. A combination of macro and wide-angle photography, with mosaicing and photogrammetry, proved to work very well to comprehensively document the condition of key wreck features at different scales. The photogrammetry and the photomosaicing together allowed a comprehensive level of visual recording of the condition of the wreck, which could act as a baseline for further surveys of the wreck site in future, to support monitoring of its condition.

Natural Heritage and Influence of the Wreck on Its Surroundings

Since the wreck has lain on the seabed for more than 70 years, its structure and surfaces have been colonized by a diverse array of marine life, some of the more dominant forms including hydroid colonies and feather stars. Notably, on the seabed adjacent to the wreck, some species of national conservation importance were recorded. The structure of the decaying wreck itself is acting as a trap for loose red seaweed; this seaweed is now being used by Flame shells as raw building materials for their nests. In turn, these nest complexes provide refuge to numerous species and are therefore supporting the enhancement of biodiversity. In the adjacent muddy sand substrate, the siphons and very occasionally at the surface, an entire individual of the Ocean Quahog, Arctica islandica, have been observed (Scourse et al., Citation2006). The presence of numerous examples of this long-lived, slow-growing species suggests that the habitat has lain relatively undisturbed for some decades, as the wreck is acting as a reef, and prevents other activities such as trawling in that area of the seabed. The wreck itself is acting as an artificial reef, serving as an island-like habitat on the seafloor, in an area that is otherwise muddy sand. The presence of the hard surfaces provided by the wreck allows hard substrate epifauna to colonize. The information on the biodiversity of the wreck generated by this study provides baseline data to quantify how shipwrecks can enhance local biodiversity. This type of data is being generated in other areas where there are aggregations of shipwrecks: e.g. in Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary (Meyer-Kaiser et al., Citation2022), helping to build a growing body of data across the globe regarding the positive impacts of shipwrecks on biodiversity enhancement.

Conclusion

SP 744 represents a relatively intact example of a special type of vessel used for the specific purpose during the war years, of ferrying officials to and from larger vessels/warships. For those visiting Scapa Flow, it makes an interesting dive of a Royal Navy vessel that played its role in the day-to-day life of naval personnel. While there are several Royal Navy pinnaces in Scapa Flow, the others are on protected sites such as Royal Oak and Vanguard and are therefore inaccessible to recreational divers. SP 744 therefore represents an accessible example of such a vessel for the general diving community to visit.

As SP 744 is likely to have lain on the seabed since 1939 there has been ample opportunity for it to become well integrated with the natural surroundings. By acting as a trap for mats of seaweed, the wreck site has contributed to enhancement of the natural environment by making it possible for species of national conservation importance, known as Flame shells, to construct nests in the area where they perhaps would not otherwise be found (Marine Scotland, Citation2021a). It should be noted that the presence of these biogenic nest structures enables increased species biodiversity from organisms that live in association with the complexes of nest material.

SP 744 has also acted as an artificial reef on the seabed for more than 70 years, and as such represents an obstacle to trawling or dredging operations. Surveys of the flora and fauna immediately adjacent to the wreck revealed the presence of the blunt gaper (Mya truncata) (reported to live up to 28 years). The Priority Marine Species Ocean quahog (Arctica islandica) was also recorded (Marine Scotland, Citation2021b). Ocean quahogs grow very slowly and can take up to 50 years to reach market size in undisturbed areas. The oldest known example was nicknamed ‘Ming’; this was an Ocean quahog dredged up off the northern coast of Iceland in 2006. Growth ring analysis and subsequent Carbon-14 isotope analysis showed the animal to be 507 years old (Scourse et al., Citation2006); hence it would have been alive during the reign of the Ming dynasty. Given the size of Ocean quahog found in close proximity to SP 744, it is highly likely that these individuals were thriving there well before the wreck came to lie at this location, and the presence of the wreck has enabled their survival here.

The wreck of SP 744 now plays a very different but arguably important role on the seabed very much contrast to that for which it was originally designed, supporting naval defence activities. It is now contributing valuable ecosystem services to the surrounding environment by providing habitat for a range of marine life. The unique combination of cultural and natural heritage features revealed by this project are likely to be of interest to a wide audience.

Author Contributions

JP and BA conducted diving surveys, assembled text and edited the document. KH, LH and PR researched archives and assembled text. RP, CF, JM and WS conducted diving surveys.

Permission Statement

The fieldwork was conducted on site following consultation with the required statutory body Historic Environment Scotland (HES).

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to John Besant, Frank Fowler, Chris Page, Ltnt. Jen Smith, Rebecca Grieve and Jenni Kakkonen without whose valuable assistance the story of Steam Pinnace 744 could not have been told. Access to the National Archive at Kew can only be in person and so photographs of the required logs were kindly provided by Chris Page. Thanks to Richard Shucksmith and George Stoyle for initial support with photogrammetry. We are grateful to the Nautical Archaeology Society for grant funding (Grant Number HWU-15) which supported boat charter for the diving operations.

Disclosure Statement

This work was supported by the Nautical Archaeology Society, publisher of IJNA.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bullen, H. (1941–1943). Logbook number 8. (In the personal collection of Kevin J Heath, Sula Diving Ltd, Stromness, Orkney).

- Canmore ID 102327. (n.d.). Steam pinnace. Retrieved September 2023 from https://canmore.org.uk/site/102327/unknown-ore-bay-scapa-flow-orkney.

- Christie, A., Heath, K., & Littlewood, M. (2013). Scapa Flow 2013 marine archaeology survey: Final report. Kirkwall/Orkney, Scotland. Retrieved September 2023 from http://www.scapaflowwrecks.com/cms-assets/documents/158613-94536.450scapa-project-reportfinal.pdf.

- Connor, D. W., Allen, J. H., Golding, N., Howell, K. L., Lieberknecht, L. M., Northen, K. O., & Reker, J. B. (2004). The Marine Habitat classification for Britain and Ireland version 04.05. JNCC, Peterborough. http://www.jncc.gov.uk/MarineHabitatClassification.

- HMS Royal Sovereign Logbook. (1915–1949). ADM 53/110312, Royal Navy Archives, Portsmouth.

- JNCC. (2021). Marine Nature Conservation Review, Habitat Classification. Retrieved September 2023 from https://mhc.jncc.gov.uk/.

- Marine Scotland. (2021a). Flame shell beds. Retrieved September 2023 from https://marine.gov.scot/information/flame-shell-beds.

- Marine Scotland. (2021b). Ocean quahog. Retrieved September 2023 from https://marine.gov.scot/maps/953.

- Meyer-Kaiser, K. S., Mires, C. H., & Haskell, B. (2022). Invertebrate communities on shipwrecks in Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 685, 19–29. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13987

- Scapa Flow Historic Wrecks. (n.d.). Scapa Flow Historic Wrecks. Retrieved September 2023 from https://www.scapaflowwrecks.com.

- Scourse, J., Richardson, C., Forsythe, G., Harris, I., Heinemeier, J., Fraser, N., Briffa, K., & Jones, P. (2006). First cross-matched floating chronology from the marine fossil record: Data from growth lines of the long-lived bivalve mollusc Arctica islandica. The Holocene, 16(7), 967. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683606hl987rp

- Seasearch. (n.d.). Seasearch. Retrieved September 2023 from https://www.seasearch.org.uk/.

- SP199. (n.d.). Steam Pinnace 199. Retrieved September 2023 from https://www.nmrn.org.uk/news/steam-pinnace-199-shortlisted-prestigious-award.

- Stapleton, Lieutenant Commander N.B.J. (1980). Steam picket boats and other small steam craft of the royal navy. Terence Dalton Ltd. Lavenham.

- Steam Pinnaces Ledger, Volume 2. (n.d.). No. 700-786. Admiralty Library Archives, Plymouth.

- Tyler-Walters, H., James, B., & Carruthers, M. (2016). Descriptions of Scottish priority marine features (PMFs). Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 406. Scottish Natural Heritage.

- Wood, C. (2018). The divers guide to marine life of britain and Ireland (2nd ed.). Wild Nature Press.

- Agisoft software: https://www.agisoft.com/ (accessed 10/2015)

- Frameshots software: https://www.frame-shots.com/ (accessed 10/2015)

- Isle of Wight Museum Archive: www.iow.gov (accessed 10/2015)

- National Archives Kew: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ (accessed 10/2015)

- Orkney Library and Archive: https://orkneylibrary.org.uk/ (accessed 10/2015)