ABSTRACT

In 2012, the Australian National Maritime Museum and Silentworld Foundation commenced a long-term research project to investigate historic shipwreck sites associated with shipping routes through and around the Great Barrier Reef that connected 19th-century Australia with the rest of the world. This systematic survey of the Great Barrier Reef and the Australian Coral Sea included December 2018 investigations at Boot Reef, which lies 80 km east of the entrance to Torres Strait. The survey resulted in discovery of a previously undocumented early 19th-century shipwreck site, the surviving material culture of which proved critical to narrowing the field of potential vessel candidates. However, it was not just what was present that helped solve the mystery of the site’s identity, as the investigation’s evidence-based approach was complemented by the notable absence of specific artefacts and naval architectural components.

RESUMEN

En 2012, el Museo Marítimo Nacional de Australia y la Fundación Silentworld iniciaron un proyecto de investigación a largo plazo para investigar los pecios históricos asociados a rutas de navegación a través y alrededor de la Gran Barrera de Coral que conectaban la Australia del siglo XIX con el resto del mundo. El estudio sistemático de la Gran Barrera de Coral y el Mar de Coral australiano incluyó investigaciones en diciembre del 2018 en Boot Reef, que se halla a 80 km al este de la entrada del estrecho de Torres. La investigación resultó en el descubrimiento de un sitio de naufragio de principios del siglo XIX, que no había sido documentado previamente, cuya cultura material sobreviviente demostró ser fundamental para reducir el campo de posibles candidatos de embarcaciones. Sin embargo, no fue únicamente lo que estaba presente lo que ayudó a resolver el misterio de la identidad del navío, sino el abordaje basado en evidencia complementado por la notable ausencia de artefactos específicos y componentes de la arquitectura naval.

摘要

2012年,澳大利亚国家海洋博物馆和无声世界基金会启动了一项长期研究,旨在调查与穿越大堡礁及其周围航运路线有关的历史沉船遗址,这些航运路线将19世纪的澳大利亚与世界其他地区衔接起来。这项对大堡礁和澳大利亚珊瑚海的系统调查包括2018年12月对位于托雷斯海峡入口以东80公里处布特礁的调查。此次调查发现了一个之前未曾记录的19世纪早期沉船遗址,其物质文化遗存证明对缩小潜在候选船只范围至关重要。然而,有助于揭示遗址身份之谜的不仅仅是其中的遗存,更因为采用基于证据方法的调查同时还发现了特定人工制品和海军建筑构件的缺失。

摘要

2012年,澳大利亞國家海洋博物館和無聲世界基金會啟動了一項長期研究,旨在調查與穿越大堡礁及其周圍航運路線有關的歷史沉船遺址,這些航運路線將19世紀的澳大利亞與世界其他地區銜接起來。這項對大堡礁和澳大利亞珊瑚海的系統調查包括2018年12月對位於托雷斯海峽入口以東80公里處布特礁的調查。此次調查發現了一個之前未曾記錄的19世紀早期沉船遺址,其物質文化遺存證明對縮小潛在候選船只範圍至關重要。然而,有助於揭示遺址身份之謎的不僅僅是其中的遺存,更因為采用基於證據方法的調查同時還發現了特定人工製品和海軍建築構件的缺失。

المُستخلص

بدأ المتحف البحري الوطني الأسترالي ومؤسسة العالم الصامت في عام ٢٠١٢ مشروعاً بحثياً طويل المدى للتحقيق في مواقع حُطام السفن التاريخية المرتبطة بطرق الشحن عبر الحاجز المرجاني العظيم وما حوله والذي كان يربط أستراليا ببقية العالم في القرن التاسع عشر. ولقد شمل هذا المسح المنهجي للحاجز المرجاني العظيم وبحر المرجان الأسترالي تحقيقات ديسمبر التي تمت في عام ٢٠١٨ في بوت ريف والتي تقع على بعد ٨٠ كم شرق مدخل مضيق توريس. أدى المسح إلى اكتشاف موقع لحُطام سفينة لم يتم توثيقه سابقاً ويعود تاريخه إلى أوائل القرن التاسع عشر، وقد أثبتت البقايا المادية الثقافية أهميتها في تضييق المجال في وجود سُفن مُحتملة. ومع ذلك، لم يكن ما كان موجوداً فقط هو الذي ساعد في حل لغز هوية الموقع، حيث تم استكمال نهج التحقيق القائم على الأدلة من خلال الغياب الملحوظ للقطع الأثرية المحددة والمكونات المعمارية البحرية .

الكلمات الدلالیة:

Introduction

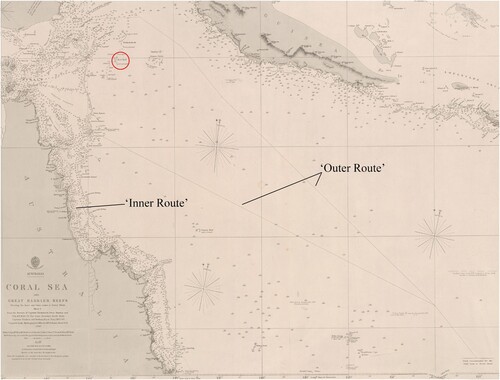

A major debate in 19th-century Australian colonial history has centred on the question of the best shipping route between Sydney, Southeast Asia, and India via the Torres Strait. Historically, two clear routes developed (). The first, known as the ‘Inner Route’, utilised the inshore passage on the western side of the Great Barrier Reef (Morgan, Citation2021). The other, known as the ‘Outer Route’, lay outside the extreme eastern edge of the Great Barrier Reef and transited through the Coral Sea. The two routes converged near Raine Island Entrance, where seafarers had the choice to switch from one route to the other, depending upon weather and other circumstances (Gibbs & McPhee, Citation2004).

Figure 1. Hydrographic chart entitled Australia, Coral Sea and Great Barrier Reefs shewing the inner and outer routes to Torres Strait from the surveys of Captains Blackwood, Owen Stanley, and Yule, R.N., 1842–50: The outer detached reefs from Captains Flinders and Denham, Royal Navy, 1802–60, showing the locations of the ‘Inner Route’ and ‘Outer Route’ used by 19th-century mariners to circumvent the Great Barrier Reef. Boot Reef is highlighted with a red circle (image: National Library of Australia and James Hunter).

In 2012, the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) and Silentworld Foundation (SWF) commenced a long-term research project to investigate these shipping routes through and around the Great Barrier Reef that connected 19th-century Australia with the rest of the world. In 2018, the ANMM and SWF located a previously unknown shipwreck at Boot Reef off Australia’s far northeast coast. Research narrowed its possible identity to one of a handful of shipwrecks from the 19th century – including a site first reported in 1891 containing a hoard of silver coins that came to be known as the ‘Jardine Treasure’. During the survey, the team discovered an anchor chain running in a west-to-east orientation across the reef, as well as a large anchor lying on the reef top, and a second, smaller anchor off the reef’s western edge precariously perched on a rock ledge in deep water. As work progressed, more artefacts and features were uncovered that suggested the wreck site was of early-19th century vintage.

The team noted a lack of specific artefacts and hull components typically observed on 19th-century wooden shipwrecks in Australian waters. This too aided in narrowing down prospective candidates for the wreck site. To deliberately misquote Carl Sagan: ‘Is the absence of [archaeological] evidence [on Boot Reef] evidence of something’s absence?’ or, put more simply, is what is not present at an archaeological site equally important as what is present? In the case of the Boot Reef shipwreck, it was not just what was present that helped solve the mystery of the site’s identity. Indeed, the project’s evidence-based approach was complemented by the notable absence of specific artefacts and architectural elements.

Lancashire Lass and the ‘Jardine Treasure’

As part of archival investigations into historic shipwrecks along the routes through the Torres Strait, the team came across mentions of a lost ‘Spanish shipwreck’, including information relating to its possible whereabouts, in the collection of Sydney’s Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (Powerhouse Museum). One object of particular interest is a Spanish silver dollar minted in Mexico City during the reign of Ferdinand VII (1808–33) and reportedly found at Boot Reef by ‘Capt. Rowe of “Lancashire Lass”’ (Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Citation2021; ).

Figure 2. Spanish coin dating to the reign of Ferdinand VII (1808–33) and reportedly found at Boot Reef in 1891 by Capt. Rowe of Lancashire Lass. It is a ‘Pillar Dollar’ produced at the Mexico Mint in 1817 (photo: Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences).

Additional secondary source material, including articles in the Cairns Post (‘Barrier Reef’, Citation1921), The Capricornian (‘Spanish relics’, Citation1924) and The Australian Museum Magazine (Whitley, Citation1926, pp. 353–354) stated the wreck had been found on Boot Reef, off Mer (also known as Murray Island). According to those sources, in March 1891 the crew of a bêche-de-mer (sea slug) fishing vessel, Lancashire Lass, located the remains of an early 19th-century vessel in 3 to 15 ft (1 to 5 m) of water on a remote coral reef in the northern approaches to Torres Strait (‘Northern mail’, 1891). Lancashire Lass was captained by Sam Rowe and owned by Francis (Frank) Lascelles Jardine, a pastoralist and plantation owner from Somerset, Queensland. The shipwreck site was reportedly discovered while the crew of Lancashire Lass – which, in some accounts, was pushed across the reef top into an enclosed lagoon during a tropical storm – attempted to cut a channel through the reef and extract their vessel (Lack, Citation1951, p. 19). Other newspapers report the divers discovered the site either while looking for the shipwreck of General Gordon or searching for bêche-de-mer (‘Northern mail’, Citation1891; ‘Treasure trove’, Citation1911).

Rowe and his crew recovered several items from the shipwreck, including an ‘old fashioned’ anchor, two cannons and several thousand Spanish silver coins minted between 1713 and the mid-1820s. Six boxes of specie (coins) were later exported from Mer on 22 May 1891 and sent to England via the steamer Tara (‘Northern mail’, Citation1891). The discovery of the shipwreck and its cargo created considerable interest in colonial newspapers such as The Daily Northern Argus (‘News by telegraph’, Citation1891), Mackay Mercury (‘Treasure trove’, Citation1891), Queensland Times (‘Thursday Island’, Citation1891), The Telegraph (‘Spanish ship’, Citation1891), and the Southern Queensland Bulletin (‘Telegram’, Citation1891) and resulted in the legend of the ‘Jardine Treasure’.

While willing to share some details, Jardine and Rowe were unsurprisingly reticent about revealing the actual location of the shipwreck. The only geographic information Jardine volunteered was that it was at ‘the very northern end’ or ‘the very outer edge’ of the Great Barrier Reef. The mystery of the wreck’s identity and its location was further compounded when Captain Rowe was later murdered by the crew of his lugger Wren in 1893 (‘Queensland news’, Citation1893; ‘Suspected murders’, Citation1893; ‘Two men missing’, Citation1893). Rowe may have discovered the wreck site of the English brig The Sun, which arrived in Hobart, Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) in February 1826 with tea, nankeens (clothes made from Nankeen/Nanjing cloth), cotton goods, sugar, and tobacco from China (‘Manifest of the brig Sun’, Citation1826; ‘No title’, Citation1826a). After departing Hobart with the remainder of its unsold cargo and 140 sheep, the vessel sailed to Sydney where its commanding officer, Captain William Gillett, secured a cargo of between $30,000 and $40,000 in silver coin to take to Calcutta, India via Singapore (‘Ship news’, Citation1826; ‘Shipping intelligence’, Citation1826).

In December 1826, reports came back to Sydney, via India, that The Sun had wrecked on a detached part of the Eastern Fields reef system on 28 May while steering for the entrance to Torres Strait (Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register, Citation1827, p. 179; ‘Latest Indian news’, Citation1827; ‘No title’, Citation1826a; ‘No title’, Citation1826b; ‘No title’, Citation1827a; ‘No title’, Citation1827b). Due to the considerable amount of specie aboard The Sun, several contemporary attempts were made to locate its wreck site on the Eastern Fields but proved unsuccessful (Bateson, Citation1974, p. 74). Although it is not possible to confirm that Rowe found The Sun, the type of coinage recovered, and its date range, seems to support the theory (‘Discovery of old Spanish wreck’, Citation1897).

2018 Boot Reef Survey

Utilising archival information related to the shipwreck discovered by Lancashire Lass’ crew, the ANMM-SWF team selected Boot Reef as a primary candidate for the site’s location. One specific aspect of the reef that supported its selection was the presence of two completely enclosed lagoons, which closely matched historical descriptions of the reef where the shipwreck was discovered. The project’s primary goal was to locate, survey and identify all historic shipwreck sites at Boot Reef. Included within this broader objective was a search to relocate and survey the remains of the shipwreck discovered by the crew of Lancashire Lass in 1891 (Hosty & Hunter, Citation2020; Hosty et al., Citation2019; Citation2021).

Following discussions with the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, the Australian Commonwealth Government’s delegated authority for the Underwater Cultural Heritage Act (2018) and Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999), permits were issued for the ANMM-SWF team to carry out a limited impact archaeological survey at Boot Reef. Boot Reef is considered part of the Sea Country of the Meriam people. There are nine Mer (Meriam) tribes: Komet, Zagareb, Mearam, Magaram, Geuram, Peibre, Meriam-Samsep, Piadram, and Dauer Meriam living on Mer, Erub and Ugar islands. These tribes were informed of the proposal to carry out archaeological investigations within their Sea Country through Parks Australia, and their approval was sought and received prior to the survey’s commencement.

Site Location and Environment

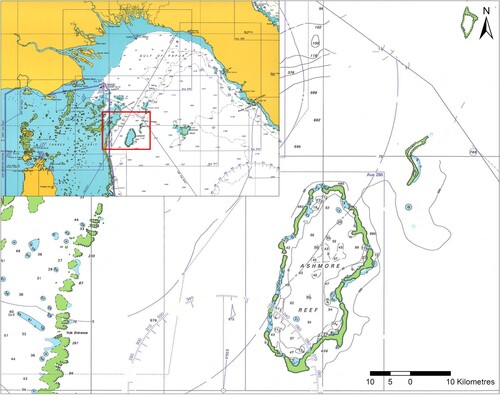

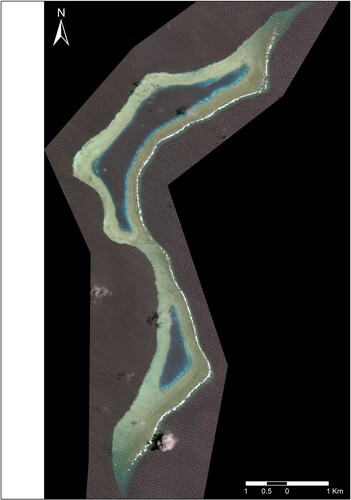

Boot Reef is located approximately 56 km (30.2 nm) east of Yule Entrance at the extreme northern end of the outer Great Barrier Reef (). It is approximately 950 km (513 nm) north of Cairns and approximately 265 km (143 nm) east of Thursday Island. It was given its European name by Lieutenant Matthew Flinders, who sailed past in 1803 on his way to England (Hosty, Citation2010, pp. 2–9). The reef is 15 km (8.1 nm) long from north to south, between 500 and 1500 m (0.3 and 0.8 nm) wide and has two central lagoons that are completely enclosed (). The southern-most lagoon is approximately 750 m (0.4 nm) long by 300 m (0.2 nm) wide and 30 m (98.4 ft) deep, while the northern lagoon is approximately 2.5 km (1.3 nm) long by 300 m (0.2 nm) wide and 37 m (121.4 ft) deep in places. During the 2018 expedition, the survey team noted the reef flat between the two lagoons is approximately 0.5–2.0 m (1.6–6.6 ft) deep at low water (Hosty et al., Citation2021, pp. 24–25).

Figure 3. Dipartite nautical chart, edited to highlight detail from Royal Australian Navy (RAN) Hydrographic Service Chart AUS 377 (2009), showing the locations of Boot and Ashmore Reefs (image: RAN Hydrographic Service).

Figure 4. Satellite image of Boot Reef, showing the unique boot-like shape after which it is named, as well as the two narrow lagoons and reef flat ‘isthmus’ that separates them (image: Geospatial Intelligence Pty Ltd./Digital Globe).

Boot Reef’s windward (east) and leeward (west) edges both feature abrupt drop-offs. This is more pronounced on the leeward side, and in most places the reef flat ends suddenly in a near-vertical wall that descends to approximately 220 m (721.8 ft), where it forms a small shelf before falling away to depths exceeding 800 m (2624.7 ft). The drop is slightly less pronounced on the reef’s windward side, where the reef flat transforms into a limited spur-and-groove formation before plunging into the abyss (Hosty et al., Citation2021, pp. 24–25).

According to historical sources, at least 15 vessels are known to have been lost during the 19th century at or near Boot Reef, as well as its near neighbours Ashmore Reef, Eastern Fields, and Portlock Reef (). Archival research related to vessel losses in the vicinity of Boot Reef has shed light on the character and nature of historic shipwrecks that may have occurred there. It also provided potential candidates for the wreck site discovered during the 2018 survey.

Table 1. Summary of all historic vessel losses reported to have occurred on or in the vicinity of Boot Reef. The two candidates for the Boot Reef shipwreck, Henry (1825) and The Sun (1826), are highlighted in green and yellow, respectively (DCCEEW, Citation2021).

Magnetometer Survey

All survey work was conducted from Silentworld, a 40-m (131-ft) liveaboard research vessel owned and operated by SWF. Upon arrival, the survey team commenced a comprehensive magnetic survey of the entire reef system with a Marine Magnetics Explorer caesium vapour omnidirectional marine magnetometer. This was informed by pre-fieldwork satellite imagery analysis and complemented by snorkel- and diver-based ground truthing, as well as aerial drone observation and recording. Positional information for areas of interest was plotted and visualised with ArcGIS (Hosty et al., Citation2021, pp. 47–52).

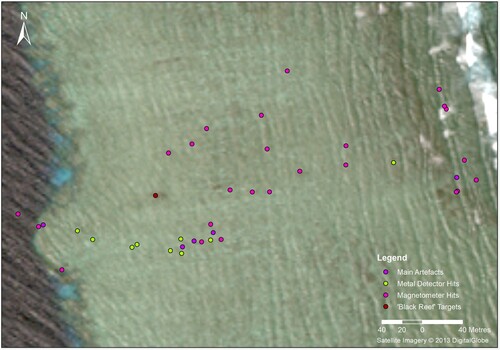

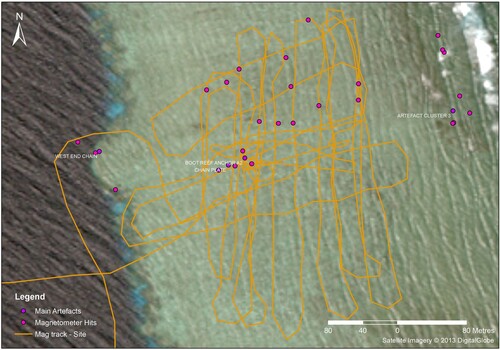

The south-eastern corner of the reef was surveyed first, as this is the most common location for historic shipwrecks within the Great Barrier Reef due to prevailing winds (Hosty et al., Citation2009, pp. 34–35, 40–56; Lucas, Citation2014, pp. 17–20). Subsequent searches focused on the northern and southern lagoons, as these areas most closely matched archival descriptions of the shipwreck’s location. No magnetic anomalies were encountered in either area; consequently, the survey moved to the reef flat between the two lagoons where a strong (110-nanotesla) multi-component magnetic anomaly of short duration was detected. A reciprocal transect was run from north to south and the magnetometer registered a strong dipole anomaly in roughly the same location. A third transect (south-to-north) detected yet another strong dipole, prompting the team to ground-truth the anomaly. Within a very short time, a run of iron anchor chain was identified within the area where the magnetic anomalies were detected ().

Figure 5. Close-order survey conducted east of the large magnetometer contact on the western edge of Boot Reef. The site’s main magnetic anomaly field is located northeast of Anchor A2 (image: Irini Malliaros and Digital Globe).

A close-order survey was subsequently conducted over the middle of the reef flat between the two lagoons. Dipole anomalies consistent with those encountered earlier in the day were detected, as well as several very large multi-component magnetic contacts. All anomalies were clustered within a relatively limited area spanning no more than 100 m (328 ft) north-to-south and approximately 300 m (984 ft) east-to-west. Several appeared to correlate to the length of chain discovered by the ground-truthing team, but other ferrous sources were also evident. The second definitive historic shipwreck feature identified during the survey, an old pattern long-shanked Admiralty Pattern anchor (discussed below), was found in deeper water near the southwest corner of the anomaly field.

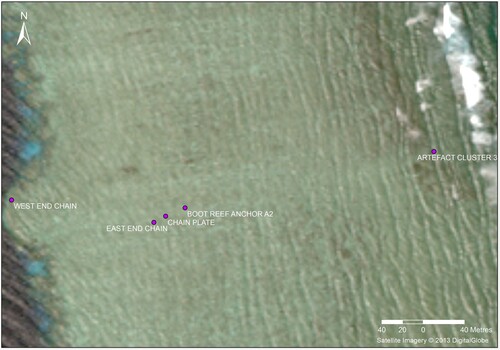

Geographic Information System Analysis

During a 2017 ANMM-SWF shipwreck survey at Kenn Reefs (also in the Australian Coral Sea Territory), dark discoloration noted in satellite imagery originated from shipwreck artefacts or features comprised of high concentrations of iron. In most cases, the area of discoloration spread out from the windward edge of the reef and increased in size as it extended north towards the lagoon on the leeward side (Hosty et al., Citation2018, pp. 66–70, 97–98; Hunter & Malliaros, Citation2017a). By contrast, large artefacts and/or features on the reef top at Boot Reef were not visible in satellite imagery, even after they were correlated with Global Positioning System (GPS) data. Coordinates for large artefacts and site features were acquired by buoying and plotting their positions with a hand-held GPS unit. None of the Boot Reef shipwreck’s primary reef top features exactly coincide with areas of discolouration visible on satellite imagery; however, one area is located approximately 45 m (148 ft) north of the anchor chain, and roughly the same distance from a cluster of magnetic targets to the east and south (see ). Curiously, no magnetic anomalies were recorded in its immediate vicinity.

The combined dataset of magnetic anomalies, metal detector contacts, and identifiable objects produce a fan-shaped distribution when plotted in Esri’s ArcMap GIS 10.8.1 (). The narrow point of the ‘fan’ begins on the western (leeward) edge of the reef flat between the two lagoons, with the westernmost anomaly in deeper water representative of the anchor located in deep water. Although contacts comprising the central part of the anomaly cluster were not examined, it is likely they represent a debris field of small artefacts like that comprising the scatter of material culture on the reef’s eastern edge (e.g., concreted iron ship’s fasteners, fittings, and hardware – see discussion below).

The Boot Reef Shipwreck

The archaeological survey of Boot Reef resulted in the discovery of historic shipwreck material. Due to the dynamic shallow-water reef environment in which the site is located, its visible artefacts and features are distributed across a large expanse of reef flat measuring approximately 500 m (1640 ft) in length (east-to-west) and 100 m (328 ft) wide (north-to-south). Longitudinal artefact scatters, where the long axis of a hull follows the direction of the prevailing northwesterly (summer) and southeasterly (winter) trade winds, are a common feature found on most northern Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea Territory reef shipwreck sites (Hosty et al., Citation2009, pp. 28–33; Hosty Citation2018, pp. 66–70, 97–98). The Comet wreck site (1829) on Ashmore Reef is a rare exception (Hosty, Citation2015, pp. 18–23). Most of the cultural material associated with the site comprises robust elements of ship’s hardware and fittings, including a run of anchor chain, Admiralty Pattern anchors, iron rudder components, copper hull sheathing, iron mast and rigging hardware, and iron and copper fasteners and fastener fragments. Small finds, such as glass bottle and deadlight fragments, and lead shot and sounding weights, were also observed.

Overall, the site’s visible components appear to be divided into three distinct clusters (). The first is located along the western edge of Boot Reef and includes the anchor chain, one anchor (located in deep water along the reef drop-off), and a scatter of small artefacts on the reef flat. The second artefact cluster includes the second anchor and additional small finds approximately midway across the reef flat. A final concentration of cultural material is located on the eastern side of the reef flat and includes scattered fasteners, ship’s hardware (such as rudder components and what appear to be iron chainplates), and the sounding weights.

Figure 7. Artefact Clusters One (anchor chain), Two (Anchor A2) and Three (eastern reef flat) comprising the shipwreck site at Boot Reef (image: Irini Malliaros and Digital Globe).

Artefact Cluster One (Western Reef Edge)

The most prominent feature within the cluster located on the reef’s western side is the anchor chain, which extends from the leeward edge in an approximate easterly direction across the reef flat for 138 m (450 ft). The majority of the chain’s visible surface is covered in a dense matrix of iron concretion, coral and adhering marine growth, while some sections are completely embedded within – and obscured by – the seabed. A small handful of chain links were covered in a thin enough layer of concretion that team members were able to identify general dimensions and other characteristics. Most chain links appear to be of standard common open link construction; however, some exhibit design traits consistent with stud-link chain. Approximately midway along its length, the size of the anchor chain’s links – the largest of which average 20 cm (8 in) long and 9 cm (3.5 in) wide – diminishes slightly to a length and width of 18 cm (7 in) and 8 cm (3 in), respectively.

At its extreme western (leeward) end, the anchor chain suddenly terminates in a broken link. Investigation of the reef wall beneath the broken chain link resulted in discovery of an Admiralty Pattern anchor (A1) perched precariously on a sand-covered ledge at a depth of 39 m (128 ft). The anchor is lying diagonally across the reef wall, with its arms oriented towards the surface, and shank pointing towards the depths (). Although largely buried in sand, enough of A1 was exposed to obtain general dimensions, including its overall visible length of 2.9 m (9.5 ft) and distance between bills of 2.2 m (7.2 ft). The anchor’s visible shank is 2.8 m (9.2 ft) long and has a maximum diameter of 15 cm (6 in) at the junction with the crown, while the length of its arms and palms averages 70 cm (2.3 ft) and 42 cm (1.4 ft), respectively. Each arm measures 12 cm (4.7 in) in diameter at its junction with the crown. One triangular palm is largely exposed above the sand and exhibits a maximum visible width of 18 cm (7.1 in). Part of a ring was visible at the end of the shank, but largely buried in sediment and consequently not recorded in detail.

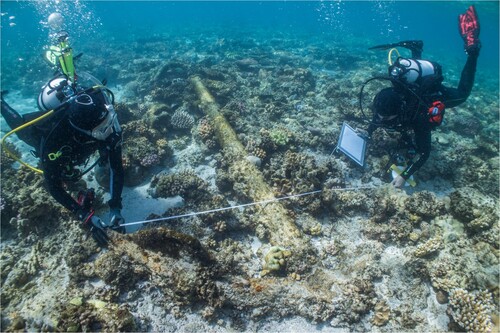

Artefact Cluster Two (Central Reef Flat)

A second Admiralty Pattern anchor (A2) was discovered on the reef flat approximately 200 m (656 ft) east of the broken end of the anchor chain. Like the example in deep water, this anchor exhibits features consistent with an old pattern long-shanked variant, including a large iron ring, triangular palms and straight arms that meet in a sharp, pointed crown (). The anchor is heavily concreted and partially obscured by a dense covering of hard coral and other marine growth, but its overall form is evident and many aspects of its design and construction – including one of the keys for its wooden stock (which is no longer present) – are visible.

Figure 9. Irini Malliaros (SWF) and James Hunter (ANMM) recording the anchor on the reef top (A2) (photo: Julia Sumerling).

A2 is larger than A1; it has an overall length of 3.8 m (12.5 ft), and the distance between its bills is 1.8 m (6 ft). The shank thickness at the crown is 20 cm (7.9 in) and narrows to 13 cm (5.1 in) at the point just beneath the shank head. The shank head itself is 15 cm (6 in) wide and features a 4-cm (1.6-in.) thick stock key midway along its length. A circular aperture that accommodates an iron ring penetrates the top of the shank head. The ring is cylindrical in profile, 7 cm (2.8 in) thick and has interior and exterior diameters of 44 cm (1.4 ft) and 60 cm (2.0 ft), respectively. Each of the anchor’s arms measures 1.2 m (3.9 ft) in length and is topped by a 3-cm (1.2-in.) thick triangular palm with a length of 52 cm (1.7 ft) and maximum width of 40 cm (1.3 ft). The bill at the end of each palm is prominent and extends 6 cm (2.4 in) beyond the apex of the palm’s triangular peak. Examination of the shank near the ring revealed it has been bent and twisted – an attribute that very likely resulted from tremendous forces exerted on the anchor during – and possibly after – the wrecking event.

A handful of small artefacts were observed in A2’s immediate vicinity, including a deck light fragment, green glass bottle shard, two heavily eroded copper bolts and a partial copper coak from a wooden sheave. The glass deck light fragment is heavily abraded from sand scour and being tumbled around the reef but appears to have once comprised part of a circular, dome-shaped variant known as an ‘Illuminator’. It was left in situ on the reef top. The two copper bolts were collected from the reef top for further analysis. The first bolt is 18 cm (7.1 in) long and has an eroded diameter of between 0.2 and 0.6 cm (0.1 and 0.2 in), while the second copper bolt is 10.5 cm (4.1 in) long and has an eroded diameter of 1.5 cm (0.6 in). Neither of the bolts have significant diagnostic features (head, point, tapering or rag cuts) and could not be positively identified.

The copper coak is a ‘three-lobed’ variant that was originally triangular in form with rounded edges and a circular fastener hole at each of its corners (). All three corners are missing, and only part of the original fastener holes within each remains. The preserved dimensions of the fastener holes average 1 cm (0.4 in) in diameter. A circular aperture occupies the centre of the coak, and measures 2.4 cm (0.9 in) in diameter. An axle would have passed through the coak and its associated sheave and connected both to the block within which they were installed. The coak’s preserved length and width are 4.8 cm (1.9 in). Around the central aperture, the coak’s internal thickness increases to 1.6 cm (0.6 in) and forms a raised edge that would have been used to secure it in its wooden sheave. The coak’s exterior face is flat, and the average thickness around its edges is 0.25 cm (0.1 in). No diagnostic features – such as a maker’s mark – are present on the coak’s preserved surfaces. The coak fragment was collected for further analysis.

Artefact Cluster Three (Eastern Reef Flat and Fore Reef)

The largest concentration of shipwreck material located at Boot Reef during the survey comprises a widely dispersed scatter of iron and copper ship’s fasteners and hardware lying atop the eastern edge of the reef flat and fore reef. The scatter is located 250 m (820.2 ft) east of A2 and is generally distributed in a linear pattern that is oriented northwest to southeast. It covers an area spanning 103 m (338 ft) long (northwest to southeast) by 20 m (65.6 ft) wide (northeast to southwest), and the main concentration of cultural material is 36 m (118.1 ft) long by 15 m (49.2 ft) wide. The seabed environment on this part of the reef primarily comprises a mix of bare rock substrate ‘pavement’ interspersed with coral rubble. To the east of the site, the bare rock substrate develops more coral formations as the water deepens towards the eastern drop-off. Spur-and-groove formations become apparent and several small, heavy artefacts, such as ship’s fastenings and copper sheathing and lead patches, were found in sand pockets formed in these grooves.

Lead Patches

Several fragments of lead were found in two different sand pockets at the bottom of groove formations to the east of the main site. A single irregularly shaped lead patch was recovered from this area. The patch is 9 cm (3.5 in) long, 6 cm (2.4 in) wide, and its thickness varies between 0.4 and 0.6 cm (0.15 and 0.24 in). Borelli (Citation2020, p. 3) observes that sheet lead in definable forms, such as lead strips or small patches known as ‘tingles’, were intended primarily for shipboard maintenance and repair. In the case of English ships, lead sheet was applied specifically to repair breached or damaged areas of the hull (Boteler, Citation1930, p. 23; Mainwaring, Citation1922, p. 177; Oppenheim, Citation1896, p. 103; Salisbury, Citation1961, pp. 86–87). Given their size and appearance, it is likely the lead fragments observed at Boot Reef are remnants of tingles.

Copper Sheathing

Several fragments of copper sheathing were found in the same sand pocket as the piece of lead patching referred to above. Two irregularly shaped examples were recovered from this area. The larger fragment is 11.5 cm (4.5 in) long, 8 cm (3.1 in) wide, and between 0.3 and 0.4 cm (0.12 and 0.16 in) thick, while the smaller example is 5 cm (2 in) long, 2.5 cm (1 in) wide, and exhibits a thickness that ranges between 0.2 and 0.3 cm (0.08 and 0.12 in).

Fasteners

Several large iron bolts were located within the scatter and average between 48 and 55 cm (1.6 and 1.8 ft) in length. A single 31-cm (1 ft) long copper bolt was also located in this area. All observed bolts are cylindrical in profile. The iron examples are heavily concreted and have an average shaft diameter of 7.6 cm (3 in), while the diameter of the copper bolt (which is devoid of marine growth and concretion) is 2.5 cm (1 in). The copper bolt’s shaft is bent at one end and appears to have been damaged by shearing force(s). None of the bolts observed in the scatter featured discernible heads or associated hardware such as a clench ring.

Several smaller ship’s fasteners were also observed among the scatter, all of which are of copper manufacture. Most are heavily abraded and have lost their identifying characteristics; however, a single hand-wrought nail or spike was found nestled in a reef crevice and was relatively well preserved (). It is 9 cm (3.5 in) long and features a square rose head measuring 1.5 cm (0.6 in) wide. The nail’s shank is roughly square in profile and measures 0.75 cm (0.3 in) in diameter just beneath the head before tapering to a relatively sharp, rounded point with a diameter of less than a millimetre.

Figure 11. Well preserved copper ship fastener with rose head found at the eastern extent of the Boot Reef shipwreck (photo: Julia Sumerling).

Two relatively well-preserved hand-wrought copper sheathing tacks were found in the bottom of a crevice on the outer edge of the fore reef and represent the southeastern (seaward) extremity of the wreck site. Both are 2.5 cm (1 in) long, square-shanked, and have a maximum shank width of 0.25 cm (0.1 in). The rose head of each is square-shaped and measures 0.5 cm (0.2 in) wide. Both tacks were discovered adjacent to the lead patching fragment, and a broken copper bolt. The bolt has a preserved length of 5 cm (2 in), and its shaft and head diameters are 1 cm (0.4 in) and 1.5 cm (0.6 in), respectively. Based on its relatively small size, the bolt may have been used to affix exterior hull planking to the vessel’s floor timbers.

Rudder Hardware

The largest elements of ship’s hardware observed on the reef’s eastern edge include three examples of iron mounting hardware for a rudder (e.g., gudgeons and/or pintles), as well as two long, flat iron objects that are probably chainplates. All rudder hardware components are heavily concreted and/or damaged; consequently, it was difficult to positively discern whether they are gudgeons or pintles. The largest and best-preserved example has a maximum preserved length of 1.27 m (4.2 ft). One of its arms is missing – and was presumably broken off during, or after, the wrecking event – but the surviving example has a width and thickness of 7.6 cm (3 in) and 2.5 cm (1 in).

Remnants of at least three fasteners are visible along the length of the arm and would have affixed the pintle/gudgeon to either the rudder or the vessel’s sternpost. All fasteners are incomplete and/or heavily concreted, but the most intact example is 10 cm (3.9 in) in diameter and 35.6 cm (1.2 ft) long. It is also bent, providing additional evidence that the pintle/gudgeon was violently torn away from vessel’s stern. Neither a pin nor circular aperture was noted at the proximal end of the pintle/gudgeon. This may be due to damage that occurred during the wrecking event; however, if the object is a pintle, it may be inverted on the seabed and its pin encapsulated and obscured by marine growth.

Rigging Elements and Mast Hardware

The two probable chainplates are located inshore from the rudder hardware, and near an iron boom ring and possible iron yardarm hoop. Both are manufactured from a single piece of flat iron bar measuring 140 cm (4.8 ft) long and 7.5 cm (3 in) wide for much of its length. One end of the bar terminates in what appears to be a circular ring, while the other tapers to a point measuring 1.5 cm (0.6 in) wide. The circular feature is heavily concreted on both examples, and details of their design and construction could not be definitively determined, but each has an external diameter of 10 cm (3.9 in), and possible internal diameter of 5 cm (2 in). In terms of overall appearance, these artefacts closely resemble the definition provided by Hedderwick (Citation1830, p. 326) for chainplates:

[They are] made of strong plate or bar-iron, of about 3 or 3 ¾-inch iron in breadth, and about 3 feet in length, from the upper part of the channel downwards; they are about 1 ½-inch thick and tapered to 5/8th of an inch thick at the lower end. Above the channel the breadth is worked to a round of about 2 inches in diameter, forming the hook, the point of which is turned inwards; it is also bent inwards close at the top of the channel, to stand with the inclination of the shrouds.

A concreted boom ring was located within the same general locale as the probable chainplates and may have been part of the same mast assembly. It consists of two iron hoops—one circular and one square—joined by a rectangular iron spacer. The boom ring’s overall length is 59 cm (1.9 ft), and the spacer between the hoops is 6 cm (2.4 in) wide. Its square aperture has an internal and external dimension of 12 cm (4.7 in) and 20 cm (7.9 in), respectively, while the circular opening measures 11 cm (4.3 in) internally and 18 cm (7.1 in) externally. In overall form, it is nearly identical to – but slightly larger than – a boom ring recovered from the Boca Chica Channel Wreck, a late-18th century Spanish or French colonial-built fishing or trading vessel located in the Florida Keys (U.S. Naval Historical Center, Citation2003, pp. 65–66). A similar example was also noted on the wreck site of the Nantucket whaling ship Two Brothers, which wrecked near French Frigate Shoals (Northwestern Hawaiian Islands) in 1823 (Raupp, Citation2015, pp. 175–176).

Boom rings were used in conjunction with a vessel’s main or lower yard to set studding sails. Used primarily to add extra canvas in light airs, studding sails were flown from a small wooden boom that inserted into the boom ring’s circular aperture. Its rectangular aperture was in turn installed over a corresponding key protruding from a ‘boom iron’ at the outer end of the yard. David Steel’s Elements and Practice of Naval Architecture (1794, Plate 5) notes boom irons with rectangular apertures were ‘mostly used in the merchant service’. Further, they appear to have been restricted to the main and lower yards and were not used in conjunction with mizzen or topsail yards. Similar boom rings appear in a cyclopaedia of naval architecture authored by Abraham Rees (Citation1819, p. 108, Plate VIII), and Robert Kipping’s, Citation1853 Rudimentary Treatise on Masting, Mast-Making, and Rigging of Ships. They were a common feature aboard vessels outfitted with studding sails during the late 18th and early-to-mid 19th centuries, and Kipping (Citation1853, p. 30) notes boom rings featuring a ‘square hole that fit the [iron] neck’ or key located on the end of the yardarm were commonly used ‘on … small ships’.

Another ring-shaped piece of iron hardware was discovered near the northwestern terminus of the scatter and may be a hoop or band for a yardarm. Its external diameter (with adhering concretion) is 35 cm (1.1 ft), and its internal diameter measures 19 cm (7.5 in). The band’s thickness and width are 3 cm (1.2 in) and 6 cm (2.4 in), respectively. Although largely encapsulated in concretion and marine growth, small sections of the artefact’s original iron surface were recently exposed and exhibited signs of flash rusting. Iron hoops were typically fitted over a yardarm as one of the final steps in its manufacture and were intended to reinforce the yardarm and prevent it from splitting (Crothers, Citation2014, p. 87; Rees, Citation1819, p. 108).

Small Finds

Only three small finds were observed within Artefact Cluster Three, and all are manufactured from lead. The first is a single round shot located near the possible yardarm hoop at the northern end of the scatter. It is spherical in shape and measures 1 cm (0.4 in) in diameter. Although mostly covered in marine growth and lead oxide concretion, a small section of the mould line was visible.

The other two small finds are sounding leads, one of which was found immediately adjacent to the large pintle/gudgeon, and the other lying exposed on the reef flat a short distance away. The example located next to the pintle/gudgeon is unusual in that it is square in profile and does not taper over the course of its length (). It measures 22 cm (8.7 in) long, and each of its sides is 4 cm (1.6 in) wide. It weighs 3.6 kg (7 lbs., 15 oz.). A circular aperture at the top of the sounding lead would have accommodated a lead line and measures 1 cm (0.4 in) in diameter. A dome-shaped indentation that would have held a ‘charge’ of beeswax or tallow to collect sediment samples and determine seabed composition is located at the sounding lead’s base and measures 2.5 cm (1 in) in diameter (Kemp, Citation1988, p. 471).

Figure 12. One of two coastal sounding leads found near the Boot Reef shipwreck’s rudder hardware. It is unusual in that it is roughly square in profile and doesn’t taper over the course of its length (photo: Kieran Hosty).

The other sounding lead has an overall length of 25 cm (9.8 in), measures 5 cm (2 in) in diameter at its base, and gradually tapers to 2 cm (0.8 in) just above the eye that would have accommodated the lead line (). It too weighs 3.6 kg (7 lbs., 15 oz.). The eye is roughly circular and measures 1.5 cm (0.6 in) in diameter. Remnants of what appear to be facets along its side suggest the lead was originally octagonal in cross-section. This is difficult to confirm, however, as most of its exterior surface has been heavily battered and abraded from exposure on the seabed. Both sounding leads were recovered for further analysis.

Figure 13. The other coastal sounding lead recovered from the Boot Reef shipwreck. It exhibits a more traditional tapered form and cylindrical or faceted cross-section (photo: Paul Hundley).

Sounding leads are a common feature of shipwreck sites, as they were considered an essential shipboard tool. Most vessels carried two primary forms of sounding lead: small ‘coastal’ or ‘hand’ leads for shallow inshore areas, and deep-water leads for waters up to 200 fathoms (366 m, or 1200 ft) (Kemp, Citation1988, p. 471). Hand leads were small enough to be thrown by the leadsman, typically weighed between 6 and 10 lbs. (2.7 and 4.5 kg) and were outfitted with a sounding line 20 fathoms (37 m, or 121 ft) in length. In terms of size and overall appearance, the Boot Reef leads resemble those recovered from shipwrecks that cover a vast cultural and temporal range (see Bingeman, Citation2015, p. 126; Hamilton, Citation1992, pp. 223–224; Keith et al., Citation1984, p. 56; Redknap & Besly, Citation1997, pp. 200–201; Sténuit, Citation1977, p. 111; West, Citation2005, pp. 71–74).

Discussion

Cultural material observed at the Boot Reef shipwreck site is indicative of a single wooden-hulled vessel constructed, outfitted, and operated during the first three decades of the 19th century. Of the 15 vessels known to have been lost on or in the vicinity of Boot Reef, four were built and subsequently lost between the years 1800 and 1830, and all were of British nationality. One was constructed in England, while the remainder were Canadian built but operating under British ownership. Cargo capacity listed for the four vessels in archival sources varies between 185 and 464 tons. Significantly, two – Fame (1817) and Comet (1829) – featured iron knees or beams in their construction.

By the late 18th century, advances in the disciplines of naval architecture and ship design allowed British shipbuilders, owners, insurers, and underwriters to devise a series of rules and regulations governing the construction of wooden ships. Minimum standards were developed for construction techniques and materials. These rules and regulations (such as the 1819, 1834, 1857 and 1864 editions of Lloyd’s Rules and Regulations with Registration Tables) and other contemporary references to ship construction and design were compared with archaeological material found on the seabed at Boot Reef to build a profile of the wrecked vessel and determine its identity (Pink & Whitewright, Citation2022, pp. 7–15).

Anchors

In terms of overall form, each anchor discovered at Boot Reef exhibits a thin shank that would have been fitted with a wooden stock (no longer present). This trait, coupled with the large iron ring and sharp crown formed by the confluence of both arms, is consistent with an ‘old pattern long-shanked’ variant of the Admiralty Pattern anchor. Developed in Great Britain, this style of anchor was in common use throughout the 18th century (Curryer, Citation1999, pp. 73–78; Upham, Citation1983, pp. 15–18). The British Royal Navy used old pattern long-shanked anchors until ca. 1840, when they were gradually replaced by an ‘improved’ design (known as the ‘new style Admiralty Pattern’ anchor) developed by Admiral William Parker. Merchant vessels also used old pattern long-shanked anchors well into the early 1800s, although newer styles such as Richard Pering’s ‘improved long shank anchor’ (1813) and Lieutenant Rodger’s ‘small-palmed anchor’ (1831) had largely superseded them by mid-century. These latter variants exhibit characteristics – such as an oval cross-section and slight curvature in the arms – that make them distinct from their old pattern long-shanked contemporaries (Curryer, Citation1999, pp. 73–78).

Pering’s original pattern anchor was more compact, lighter, and stronger than the old pattern long-shanked Admiralty anchor. In 1815, the design was tested by the Admiralty Board and ultimately approved for use in the Royal Navy (Pering, Citation1819). It remained the naval standard for British anchors until 1835, when it was replaced by Pering’s improved long shank design (Curryer, Citation1999, pp. 73–78). The improved anchor was more compact, lighter, and stronger than the old pattern long-shanked anchor and demonstrated better holding power than Pering’s original pattern. Following its adoption by the Royal Navy, Pering’s improved variant was briefly the preferred anchor for merchant vessels until replaced by Porter and Trotman style anchors in the early 1850s (Curryer, Citation1999, pp. 73–78).

Both anchors discovered at Boot Reef are later variations of the old pattern long-shanked design. In addition, each is outfitted with an anchor ring rather than one or more iron shackles, which were first patented by Royal Navy lieutenant Samuel Brown in 1808 (Traill, Citation1885, p. 4). These traits indicate the shipwreck at Boot Reef was most likely outfitted prior to 1830, with older hardware and a mixture of both hemp and iron anchor cables. Furthermore, each anchor’s respective size provides an indication of the tonnage of the vessel that would have used it. A comparison of A2’s total length (3.81 m, or 12.5 ft) with information contained in Steel (Citation1812, Folio LVII) reveals an exact match with the largest anchors used aboard merchant ships of 330 tons. The weight recorded for an anchor of this size (18 hundredweight, or cwt) compares favourably to data provided in Fincham (Citation1825, p. 376), which notes examples of 18 cwt outfitted ‘with a wood stock and hemp cable’ were suitable for a vessel of 360 tons.

Steel (Citation1812, Folio LVII) records a weight of 8 cwt for anchors measuring 9 ft, 6 in (2.95 m) in length – the exact length of A1. Further, the same treatise notes an anchor of this size typically comprised the largest anchor for a vessel between 130 and 170 tons. This correlates well to Fincham (Citation1825, p. 376), which advises that an 8-cwt anchor outfitted with a ‘wood stock and chain cable’ was best suited for a vessel of 160 tons burthen. However, given A1 and A2 are almost certainly from the same shipwreck, the greater likelihood is that A1 is one of the vessel’s smaller anchors.

Most late-18th and early-19th century merchant ships carried a minimum complement of five anchors: two bowers, one sheet, one stream and one kedge (Curryer, Citation1999, p. 51; Evans & Nutley, Citation1991, pp. 42–43). By the 19th century, the three largest anchors (best bower, small bower, and sheet) were typically around the same size and weight, while the kedge and stream anchors were smaller (Stanbury, Citation1994, p. 70). According to Steffy (Citation1994, p. 267), the stream anchor was the second smallest used aboard ship, often ‘about one-third the weight of the best bower’, and kept in the stern, where it could be ‘used to prevent a vessel from swinging in narrow waterways’.

The ratio between the best bower and stream anchor is reinforced by Steel (Citation1812, Folio LVII), who notes an early 19th-century British vessel between 300 and 350 tons would have been outfitted with three primary anchors of 20 cwt, and a stream anchor weighing 7 cwt. A1’s hypothesized weight (based on its overall length) is approximately one-third that of A2, which suggests it may have been the vessel’s stream anchor. A2, in turn, was likely either the sheet anchor, or one of the bowers. Given the sheet anchor was ‘the heaviest … of a large vessel, [and] shipped in a ready position to be used for any emergency’, it seems likely it would have been the first of the largest three anchors to be let go after the vessel struck the reef (Steffy, Citation1994, p. 266).

Stud-Link Chain

While two anchors were discovered in association with the shipwreck site at Boot Reef, only one iron anchor chain (or cable) was located. It is paid out over the reef top and, based on the broken link at its western terminus, is almost certainly associated with A1 – which is located on the reef wall directly beneath it at a depth of 39 m (128 ft). The lack of a second anchor chain suggests A2’s cable was constructed from natural fibre such as hemp or manila. Stud-link chain was first patented by Lieutenant Samuel Brown in 1808, and again in 1811 (Traill, Citation1885, p. 5). While ship owners were cautious about adopting new technologies, stud-link anchor cables were carried as a matter of course on most European vessels by the mid-to-late 1830s (Curryer, Citation1999, pp. 101–104).

Copper Sheathing

The two small fragments of sheathing are manufactured from copper, rather than an alloy of copper (such as Muntz metal). Although by no means conclusive, the presence of copper sheathing suggests an early-19th century date range for the Boot Reef shipwreck (De Rosa et al., Citation2014; O’Guinness Carlson et al., Citation2010). For over two thousand years, shipbuilders have tried to protect the wooden hulls of their ships from the ravages of timber eating organisms. These include ‘shipworm’ (Teredo sp.), which is a wood-boring bivalve mollusc, and ‘gribble’ (Limnoria sp.), a wood-boring isopod crustacean (Staniforth, Citation1985, pp. 21–22).

Royal Navy warships were first clad in copper sheathing in the 1760s, and by 1777 the first British merchant vessels followed suit. The next major development in hull sheathing occurred in 1832, when G.F. Muntz developed an alloy of copper and zinc known alternately as ‘Muntz metal’ or ‘patent yellow metal’. Muntz metal (comprising an alloy with a ratio of 60% copper and 40% zinc) proved ideal for covering ships’ hulls, and by the mid-1840s was the most common metal sheathing affixed to British and continental European vessels (McCarthy, Citation2005, pp. 101–107, 115–118; Staniforth, Citation1985, p. 24; Viduka & Ness, Citation2004, pp. 160–163).

Iron Rudder Fittings

The largest elements of ship’s hardware observed on the reef’s eastern edge include three examples of iron mounting hardware for a rudder. The largest and best-preserved example has a maximum preserved length of 1.3 m (4.3 ft). One of its arms is missing – and was presumably broken off during, or after, the wrecking event – but the surviving example has a width and thickness of 7.6 cm (3 in) and 2.5 cm (1 in).

Based on information contained within ‘Rules for Classification’ included in the 1834 edition of Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping (Citation1834, pp. 12–13), the dimensions of the best-preserved gudgeon/pintle compares favourably with that of a sailing vessel between 450 and 500 tons. This includes the overall length (1.3 m, or 4.3 ft), number of clinched through-bolts (three), and their diameter (10 cm, or 3.9 in), which corresponds to that of a vessel equal to 500 tons. The use of iron in the manufacture of the Boot Reef shipwreck’s rudder hardware is highly unusual for a vessel built in Great Britain during the mid-to-late 19th century. Copper and copper-alloys were more commonly used to manufacture gudgeons and pintles during this period. Iron rudder hardware is generally more indicative of a vessel constructed during the late-18th or early-19th centuries, prior to the widespread introduction of copper sheathing and the problems caused by differential corrosion of iron fastenings (Harris, Citation1966, pp. 552–554; Hedderwick, Citation1830, pp. 160–161; McCarthy, Citation2005, pp. 109–114). Iron pintles and gudgeons were also a common feature of wooden-hulled vessels built in North American shipyards (such as those in eastern Canada) during the 19th century (Marcil, Citation1995, pp. 234–238; Stammers, Citation2001, pp. 116–119).

Ship Fasteners

All three artefact scatters at Boot Reef contain copper and iron ship fastenings. These range in size from small rose-headed sheathing tacks to heavily eroded bolts and dumps used to secure large structural timbers to one another. The site also features copper nails used to affix hull and deck planking, as well as several large iron bolts. The iron bolts were located within the scatter on the eastern side of Boot Reef and averaged between 48 cm (1.6 ft) and 55 cm (1.8 ft) in length. A single 31-cm (1-ft) long copper bolt was also located in this area. All observed bolts are cylindrical in profile. The iron examples are heavily concreted and have an average shaft diameter of 7.6 cm (3 in). The diameter of the copper bolt (which is devoid of marine growth and concretion) is 2.5 cm (1 in), which falls between the bolt diameters listed in Lloyd’s Register’s ‘Rules for Classification’ for vessels of 150 tons (7/8 in) and 500 tons (1 1/8 in) (1834, p. 18). Given the ‘Rules for Classification’ state ‘the scantlings and dimensions of all intermediate vessels to be proportionately regulated’ it can be inferred that the 2.5 cm (1 in) bolts indicate a vessel in the vicinity of 300 tons (Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, Citation1834, p. 14).

Beginning in the 1750s, both the French and British navies commenced experimenting with copper and its alloys as a suitable material for ship fastenings (Bingeman, Citation2000, pp. 218–224; Harris, Citation1966, pp. 552–554; McAllister, Citation2012; McCarthy, Citation2005, pp. 104–115; Philpin et al., Citation2021, p. 75, 84–85). Although more expensive and more difficult to manufacture than fasteners forged from iron, copper and copper-alloy fastenings offered a significant advantage over iron in terms of corrosion resistance (McCarthy, Citation2005, pp. 104–115). This was especially true for fasteners used below the waterline, in association with copper sheathing and/or used to secure naturally acidic timbers such as white oak (Quercus sp.). By the mid-1770s, myriad patents for copper and copper-alloy ship fastenings existed, including Keir’s Metal (100 parts copper, 75 parts zinc and 10 parts iron). The Royal Navy rejected Keir’s Metal in 1781 due to manufacturing difficulties and ongoing corrosion problems; however, by 1782 a new alloy, developed by Thomas Williams and William Forbes, was becoming widely accepted among British shipbuilders and ship owners (McCarthy, Citation2005, pp. 104–105). The new patent used an alloy manufactured from copper and zinc that was mechanically strengthened by being drawn through grooved rollers during the foundry process (Staniforth, Citation1985, pp. 25–26).

While the British and French navies, and in some cases the British East India Company, could afford to use copper fastenings and sheathing on their ships, British, American, and European merchant fleets could not (Bingeman & Dunlop, Citation2023, p. 214). Consequently, adoption of the new material was slow, and many ship owners opted to only use copper fastenings below the waterline – and only when their vessels were sheathed in copper. Even some British naval vessels, such as HMB Endeavour, were not clad in copper. Endeavour’s iron fasteners were retained, and more traditional – and less expensive – sacrificial timber planking was used to protect the hull beneath the waterline (Marquardt, Citation1995, pp. 12–13; McCarthy, Citation2005, pp. 101–114; Staniforth, Citation1985, pp. 25–26).

Use of copper sheathing and fasteners remained limited for the remainder of the 18th century, and it was not until the early 1800s that they became commonplace on British-built vessels. Although not conclusive, the presence of a mix of both copper and iron hull fastenings at the Boot Reef shipwreck site suggests the vessel was built during a transitional phase in shipbuilding wherein iron fasteners and fittings were gradually superseded by those manufactured from copper and its alloys. This phase commenced around 1800 and continued until the 1820s, when first pure copper, and subsequently copper-alloys, became the predominant metals utilized in wooden ship construction (McCarthy, Citation2005, pp. 101–122).

Other Ship Fittings

The deck light fragment is heavily abraded from sand scour and being tumbled around the reef but appears to have once comprised part of a glass ‘Illuminator’. Originally circular in form with a thick, dome-shaped cross section that tapered towards its edges, this form of deck light would have been mounted in a deck or vertical structure (such as the side of the hull) to allow light into the vessel’s internal spaces. The earliest appearance of the ‘Illuminator’ form of deck light is in 1807, when it was patented by Londoner Apsley Pellat (Pellat, Citation1807, pp. 321–323; Quinn, Citation1997, p. 142). By 1812, the term ‘Illuminator’ was replaced by ‘Patent-light’ or, more commonly, ‘Bull’s-eye light’ (Quinn, Citation1997, p. 142). Bull’s-eye lights remained in common use throughout the remainder of the first half of the 19th century, but were gradually superseded by prismatic deck lights, kerosene lanterns and other forms of interior lighting from the 1840s onwards (Quinn, Citation1997, pp. 145–146).

Copper coaks, like the example found at Boot Reef, were inset into the wooden surfaces of sheaves to act as a bushing and support the pin (axle) that passed through the block assembly. In Australia, the earliest known examples of copper coaks are those recovered from the wreck of the Dutch ship Zeewijk, which wrecked in the Houtman Abrolhos in 1727 (Western Australian Museum, Citation2019). However, the Zeewijk coak’s form, due to its Dutch origin and earlier date, is fundamentally different from the fragment recovered from Boot Reef, which more closely resembles examples recovered from British shipwreck sites dating to the late-18th and early-19th centuries (Bingeman, Citation2015, p. 99; Campbell & Gesner, Citation2000, pp. 63–65; Erskine, Citation2004). In terms of both size and form, the Boot Reef coak is nearly identical to examples recovered from two early-19th century British shipwrecks located in the waters of the Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea: HMCS Mermaid (1829) and the convict ship Royal Charlotte (1825) (Hosty et al., Citation2009, p. 75).

The Absence of Iron Naval Architectural Elements

Given relatively rapid advances in naval architecture in the 19th century, iron structural components (such as knees) became a common feature of vessels built in Great Britain and continental Europe. Not surprisingly, ferrous elements of ship architecture are frequently found in association with 19th-century shipwrecks on the Great Barrier Reef and in the Australian Coral Sea Territory (Hosty, Citation2013, Citation2015; Hunter & Malliaros, Citation2017b). It is extremely unusual then, that no iron knees or other forms of ferrous ship architecture (other than rudder fittings) are present on the shipwreck site at Boot Reef.

Although first suggested by Sir Anthony Deane in the 1670s for use in the first-rate ship Royal James, iron knees do not appear to have been introduced to European shipbuilding until the late-18th century. William Falconer first recorded their use as an innovation developed by the French Navy in 1780 (Stammers, Citation2001; Philpin et al., Citation2021). Gabriel Snodgrass, the chief surveyor of vessels used by the British East India Company (EIC) between 1757 and 1794, appears to have been the first known advocate for the use of iron knees in British and colonial Indian shipbuilding (Stammers, Citation2001) He was instrumental in the EIC’s decision to use iron knees, stanchions, breasthooks and crutches in Company vessels from 1810 onwards. The result of Snodgrass’ initiative was that EIC vessels built in India were being fitted with iron knees several years before ships of the Royal Navy. The effort to install iron architectural elements in British warships was overseen by the Royal Navy’s Chief Surveyor, Sir Robert Seppings (Packard, Citation1978). Despite their early use in EIC vessels, it was not until the early 1830s that the use of iron knees, riders, stanchions, and other supporting structure became common practice in British merchant shipbuilding (Stammers, Citation2001; Philpin et al., Citation2021).

In 19th-century North America, where shipbuilders had access to vast supplies of local timber, the use of iron components such as knees, crutches and breasthooks was kept to a minimum. Stammers (Citation2001, pp. 115–116) along with Crothers (Citation1997, pp. 230–238) and Philpin et al. (Citation2021, p. 84) observe that few North American ships were fitted with iron knees during the early-to-mid 19th century. Ships built in Great Britain’s Canadian colonies were no different to those built elsewhere in North America, but they were often later modified or adapted upon completion and sale to buyers in the British Isles to meet insurance requirements (Marcil, Citation1995, pp. 234–238). New Brunswick was particularly known for producing all-timber vessels that were later sold to British ship owners and re-registered in England. In many cases, these vessels were retrofitted with iron knees and other ferrous architecture (Marcil, Citation1995, pp. 234–238; Stammers, Citation2001, pp. 115–121).

Lloyd’s of London surveyors were not stationed permanently in the Canadian Maritimes until the 1850s; however, the firm’s classification standard greatly influenced how ships were built in the colonies – particularly if owners wanted to sell their vessels to European buyers. Lloyd’s actively discouraged the use of softwoods such as pine and spruce – which were frequently used in ships constructed in Canadian shipyards – and downgraded the insurance rating for vessels built from these timbers (Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, Citation1810, pp. 13–15). The downgrade resulted in higher insurance premiums, higher maintenance costs to pass survey, possible loss of more lucrative and valuable cargoes, and lower resale value (Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, Citation1876, pp. 100–124; Marcil, Citation1987, pp. 222–234).

To get around this problem, Canadian shipbuilders began using iron knees at shipyards in New Brunswick and Quebec from 1811 onwards (Marcil, Citation1987, p. 322, 1995; Stammers, Citation2001, p. 116). The iron elements were manufactured in Great Britain and imported to New Brunswick. By the mid-1830s, Lloyd’s amended its Rules and Regulations for colonial vessels to stipulate they must ‘be secured in their bilges by the application of iron riders’ to receive an ‘A’ rating (Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, Citation1837, p. 17). Further, additional bolts were to be used in each vessel’s construction, and all ships ‘secured by iron-hanging knees to the hold beams’ (Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, Citation1837, p. 17). The result was that iron knees became a standard feature of New Brunswick-built vessels, most of which were retrofitted in England prior to sale (Marcil, Citation1987, pp. 267–285; Stammers, Citation2001, p. 117). By the 1830s, iron knees in Canadian-built ships were being supplemented by diagonal iron bracing to further strengthen their hulls (Sager & Panting, Citation1990).

The presence of iron knees on a shipwreck site normally indicates a build date from the 1820s onwards, although historical evidence reveals that some Indian- and Canadian-built vessels were fitted with iron knees as early as 1810 (Goodwin, Citation1998, pp. 30–33; Marcil, Citation1987, p. 322; Stammers, Citation2001, pp. 115–116). Generally, however, the absence of iron knees or other ferrous architectural elements on the Boot Reef shipwreck strongly suggests it predates the 1830s. Further, given the British and Canadian origins of the four vessels known to have wrecked in the vicinity of Boot Reef during this period, an argument can be made that it could be a North American-built vessel that was either registered to an American owner, or a British owner that had not yet retrofitted it according to Lloyd’s regulations.

A Candidate Emerges

Archaeological investigation of the shipwreck discovered at Boot Reef in 2018 strongly suggests its remains are those of a wooden-hulled merchant sailing vessel between 200- and 400-tons burthen. Aspects of its construction, including copper sheathing, a mix of iron and copper fasteners, and the presence of a glass ‘Illuminator’ or ‘Bull’s-eye’ light, indicate it was likely built after 1800, but prior to 1830. The vessel’s proposed date range and size is reinforced by two old pattern long-shanked Admiralty anchors, the presence of only one iron anchor chain fitted with a relatively small number of stud-links, and the iron boom ring. Furthermore, the presence of iron rudder fittings and absence of iron knees and other ferrous internal bracing, suggests the vessel was most likely built in North America during the first two decades of the 19th century. Due to the relative dearth of small finds associated with the site, archaeological evidence of the vessel’s nationality or cultural affiliation could not be definitively established; however, the presence of the Admiralty-pattern anchors and three-lobed copper pulley coak lend credence to a British identity. This is reinforced by accounts of early 19th-century ship losses on the Great Barrier Reef and in the Coral Sea, which indicate all known wrecked vessels were exclusively owned and/or operated by British or colonial Australian concerns (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water [hereafter DCCEEW], Citation2021).

Spatial analysis of the three main artefact scatters, as well as distribution of the two anchors and run of chain, indicates the vessel was sailing on an easterly or northeasterly track when it struck the western edge of Boot Reef. The crew appears to have deployed the smaller anchor (A1) first and fitted it with the iron cable. This was likely the stream anchor, and was ideally positioned on the vessel’s stern, where it could have been quickly deployed in a possible attempt to prevent the vessel going further onto the reef, as well as used in subsequent efforts to kedge it off. It is likely the stern extended over the edge of the reef at the time the anchor was let go, and this would account for its precarious position on the reef wall. The vessel then appears to have surged bow first across the reef flat, causing the attached chain to pay out. Ultimately, the chain broke and the second anchor (A2) – probably the sheet fitted with a hemp or manila cable – was deployed. At this point, the bow may have swung around to face back towards the west, which could account for A2’s shank pointing in that direction. It was also here that the hull began to break up, as evidenced by the tight cluster of artefacts located around A2, as well as more widely dispersed material northeast of the anchor.

The vessel continued to surge in an easterly direction, which placed strain on A2’s cable. This caused the anchor ring to pivot towards the leeward (eastern) side of the reef and may also have deformed the anchor’s shank. Near the eastern edge of the reef the vessel came to rest and continued to break up in the surf. Ship fasteners, deck lights, copper sheathing, chain plates and mast hardware were all deposited on the reef top as the timber hull started to work apart. The presence of multiple rudder fittings suggests catastrophic damage occurred to the vessel’s stern, either because the rudder became unshipped, the vessel’s sternpost partially or completely broke away from the hull, or both. While certainly damaged, the vessel appears to have remained largely intact, given the complete absence of ballast and additional anchors. The fact no other anchors were found on the reef top or fore reef seems to suggest they either weren’t used or were possibly salvaged later. However, the most likely scenario is they remained aboard the surviving – but fatally damaged – hull, which drifted or broke free shortly after the wrecking event and plunged into the depths off the reef’s eastern side.

The dispersal of material culture from west to east, rather than from southeast to north-west, also suggests the wrecking event occurred during the northern Australian wet season, which runs from November to mid-April. During this period, winds in the Torres Strait blow predominantly from the west. By contrast, Boot Reef is under the influence of strong southeasterly trade winds between late-April and October (Lucas, Citation2014, pp. 17–20; National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, Citation2017, p. 153).

According to the Commonwealth Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water’s Australasian Underwater Cultural Heritage Database (AUCHD), at least 15 recorded shipwrecks are known to have occurred within the vicinity of the Ashmore, Boot, Portlock, and Eastern Fields reef systems in the northern Great Barrier Reef (see ). Based on a review of existing archaeological and historical data, the shipwreck at Boot Reef appears to be represented by two candidates. Both feature notable correlations between the archaeological and archival records, including construction attributes, proposed vessel size, site formation features and loss date relative to historic weather patterns.

Of the entire list, the English-built brig The Sun and Canadian-built ship Henry (highlighted respectively in yellow and green in ) exhibit size and construction attributes that most closely match the shipwreck at Boot Reef. However, The Sun, at only 185 tons, is too small to have carried both anchors associated with the shipwreck, nor was it large enough to have been outfitted with the rudder hardware. Further, The Sun’s reported loss in late May falls within the period when southeasterly trade winds predominate at Boot Reef, which contradicts the west-to-east distribution of shipwreck material across the reef flat.

Based on available archaeological and historical data, the likeliest candidate for the Boot Reef shipwreck is Henry. The Quebec-built vessel entered service in 1819, was fitted with spruce knees instead of iron internal bracing and was never retrofitted with iron knees or bracing when re-registered in England (Society for the Registry of Shipping, Citation1819, Citation1820, Citation1821, Citation1822, Citation1823, Citation1824, Citation1825). At 386 tons, its size most closely approximates that for a vessel outfitted with the anchors, chain and rudder fittings observed on the wreck site. Henry was contracted to transport convicts to Australia in 1823 and again in 1825. The first voyage resulted in the delivery of 160 male convicts to Sydney, New South Wales, while the second transported 79 female convicts, 10 convict children, 25 free women and 23 free children to Hobart in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) (Bateson, Citation1974, pp. 344–345). After delivering additional passengers and two female convicts to Sydney in February 1825, Henry departed with passengers and a general cargo and was lost in 1825 on an unnamed reef in the vicinity of Torres Strait while sailing northbound to Batavia (Jakarta, Indonesia) (‘No title’, 17 October Citation1825, p. 2). The loss occurred in April, when Boot Reef is primarily subject to westerly winds, and this correlates well with the shipwreck’s proposed site formation scenario.

The AUCHD records a total of 175 Canadian-built vessels wrecked in Australian waters since 1788. Of these, Fame, Henry, Governor Ready (1829), Parmelia (1829) and Comet are the oldest known examples (DCCEEW, Citation2021). As a representative example of an early 19th-century Canadian-built sailing vessel, Henry is significant in terms of innovative maritime technology. Specifically, it demonstrates a blending of Canadian (exclusive timber construction with iron fastenings and rudder fittings) and British (copper fastenings and sheathing) shipbuilding techniques. Henry was involved in the well-established and essential triangle trade between England, the Australian colonies, and India that existed during the early 19th century. This trade network engaged vessels for the transport of convicts to Australia on the outbound voyage, while the return trip to England (via India) included carriage of returning soldiers, passengers, and general cargo.

Conclusion

One of the aims of the ANMM-SWF expedition to Boot Reef was to relocate an early 19th-century shipwreck that was the source of several historic silver coins in the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences in Sydney. Speculation existed these coins originated from the wreck of The Sun, which was lost at either Boot Reef, Ashmore Reef, or Portlock Reef in 1826. The survey ultimately resulted in the discovery of an early 19th-century shipwreck, but archaeological analysis of its surviving artefacts and features strongly suggests its identity is that of the Canadian-built ship Henry, which wrecked on an unspecified reef in the vicinity of Torres Strait in April 1825.

The wreck site of Henry, a former convict transport, is one of only four such vessels located and archaeologically investigated in Australian waters. The others include Royal Charlotte (1841), George III (1835), and Rodney (1858) (DCCEEW, Citation2021; Hosty, Citation2012; Hosty et al., Citation2018). The wreck sites of other convict ships such as Three Bees (1814), Hive (1835) and Neva (1835) have not yet been located (DCCEEW, Citation2021). Henry’s loss is an excellent example of the hazards faced by early 19th-century mariners when operating in poorly charted Australian waters. Shipwrecks of this kind were often used as examples during ongoing discussions by Australian colonial authorities about the need for better charting and navigational lighting along the Great Barrier Reef’s Inner and Outer Routes.

Archaeological and historical research derived from the 2018 survey also strongly argues against the Boot Reef shipwreck’s identity as that of the wrecked vessel encountered by the crew of Lancashire Lass in 1891. This is based on several factors, including the site’s location on Boot Reef, its artefact assemblage, and surviving archaeological features. The mystery wreck discovered by Captain Rowe and his crew remains unidentified and is yet to be relocated.

Author Contributions

Kieran Hosty conceived and developed the project design, collected data, conducted analysis, and composed the article. James W. Hunter, III, conceived and developed the project design, collected data, conducted analysis, composed the article, and generated graphics for figures. Irini Malliaros conceived and developed the project design, collected data, conducted analysis, composed the article, and generated graphics for figures.

Permission Statement

Specific authorisations were obtained from the Australian National Maritime Museum, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and Commonwealth Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (now Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water) to use archaeological data featured in the enclosed article.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the 2018 Boot Reef survey was graciously provided by Jacqui and John Mullen of the Silentworld Foundation. Paul Hundley’s and Pete Illidge’s archaeological expertise, Julia Sumerling’s professional photographic and videographic work, and Andrew White’s diving experience were invaluable to the success of the project. Special thanks go to Captain Michael Gooding and the crew of MY Silentworld, as well as former ANMM staff who supported our ongoing program of collaborative field research: Kevin Sumption, Director; Michael Harvey, Assistant Director – Public Engagement and Research; and Dr Nigel Erskine, Head of Research. Finally, thanks are due to DCCEEW’s Historic Shipwrecks Program, Parks Australia’s Marine Protected Areas Branch, and Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority Environmental Assessment and Protection staff for their assistance in obtaining project permits.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Paul Hundley.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anderson, R. C. (1994). The rigging of ships in the days of the spritsail topmast, 1600-1720. Dover Publications.

- Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register. (1827). Shipping intelligence: Miscellaneous notices. Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies, 23, 179.

- Atauz, A. D., Bryant, W. R., Jones, T., & Phaneuf, B. (2006). Mica shipwreck project: Deepwater archaeological investigation of a 19th century shipwreck in the Gulf of Mexico. Texas A&M University, Department of Oceanography.

- Barrier Reef treasure trove. (1921, March 18). Cairns Post, p. 4. National Library of Australia.

- Bateson, C. (1974). The convict ships, 1787–1868. A.H. & A.W. Reed.

- Bingeman, J. M. (2015). The first HMS Invincible: Her excavations. Bingeman Publications.

- Bingeman, J. M., Bethell, J. P., Goodwin, P., & Mack, A. T. (2000). Copper and other sheathing in the Royal Navy. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 29(2), 218–229. doi:10.1006/ijna.2000.0315

- Bingeman, J. M., & Dunlop, J. (2023). Bronze fastenings used on an 18th century ship built for the East India Company. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 52(1), 214–221. doi.org/10.1080/10572414.2022.2159188

- Borelli, J. (2020). An initial assessment of lead artefacts used for hull repair and maintenance on North Carolina shipwreck 31CR314, Queen Anne’s Revenge (1718). International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 49, 357–370. doi: 10.1111/1095-9270.12418.

- Boteler, N. (1930). Boteler’s dialogues (W.G. Perrin, Ed.). Navy Records Society.

- Bruseth, J. E., Borgens, A. A., Jones, B. M., & Ray, E. D. (2017). La Belle: The archaeology of a seventeenth-century vessel of New World colonization. Texas A&M University Press.

- Campbell, J., & Gesner, P. (2000). Illustrated catalogue of artefacts from the HMS Pandora wrecksite excavations, 1977–1995. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, 2, 53–159.

- Church, R. A., & Warren, D. J. (2008). Viosca Knoll wreck: Discovery and investigation of an early nineteenth-century wooden sailing vessel in 2,000 feet of water. C&C Technologies.

- Crothers, W. L. (1997). The American built clipper ships 1850–1856: Characteristics, construction, and details. International Marine.

- Crothers, W. L. (2014). The masting of American merchant sail in the 1850s: An illustrated study. McFarland & Company, Ltd.

- Curryer, B. N. (1999). Anchors: An illustrated history. Chatham Publishing.

- De Rosa, H., Ciarlo, N., Pichipil, M., & Castelli, A. (2014). 19th century wooden ship sheathing. A case of study: The materials of Puerto Pirámides 1, Península Valdés. Procedia Materials Science, 9, 177–186.