Abstract

This article reports and discusses the results of a study that investigated photographic images of children in five online terrorist magazines to understand the roles of children in these groups. The analysis encompasses issues of Inspire, Dabiq, Jihad Recollections (JR), Azan, and Gaidi Mtanni (GM) from 2009 to 2016. The total number of images was ninety-four. A news value framework was applied that systematically investigated what values the images held that resulted in them being “newsworthy” enough to be published. This article discusses the key findings, which were that Dabiq distinguished different roles for boys and girls, portrayed fierce and prestigious boy child perpetrators, and children flourishing under the caliphate; Inspire and Azan focused on portraying children as victims of Western-backed warfare; GM portrayed children supporting the cause peacefully; and JR contained no re-occurring findings.

There is a vast and growing scholarly literature focused on terrorist organizations’ online magazines.1 Most analyses are solely concerned with the magazines’ textual content2 and only very few with the images contained in the magazines, whether via combined analysis of text and images3 or focused solely on the images.4 Research into images of children in these publications is particularly scarce. This article aims to fill this gap in the literature by investigating images of children across five online terrorist magazine publications.

Several researchers have highlighted the potential that these understudied images may contain. First, Lemieux et al. noted in their textual analysis of Inspire that terrorist magazine images need to be researched in further detail with a systematic methodology.5 Second, Droogan and Peattie, who also undertook a textual analysis of Inspire, wrote that the images are potentially as equally powerful as the text and as such, further research is required.6 Finally, Benotman and Malik identified that similar work is required for online magazines as that which they had already undertaken on social media sites: how children are portrayed, the messages that these portrayals convey, and their target audience(s).7

Psychological studies have revealed that images can be very influential. For example, Stenberg found that people tend to have a better memory for images than text, which is known as the picture superiority effect.8 Wanta and Roark found that the recall of newspaper articles increased for articles that included images, especially images that elicited emotion.9 Similarly, Zillman, Knobloch, and Yu found that participants chose to read articles that featured victimization images instead of articles that featured no image or an innocuous image and that text in the articles with the accompanying victimization images was remembered better than text in the other articles.10 Overall, a wide range of studies have shown that images tend to produce both “powerful” and “lasting emotional” responses.11 These psychological studies emphasize the potential impact and influence of images in terrorist propaganda.

Further to this, Rhodes12 makes an interesting point: “Nowhere is childhood more clearly constructed or adult perceptions more visible than in photographs of children.”

Photographs of children are generally taken by adults and reveal the construction that adults believe to be appropriate for “typical” children and childhood.13 Typical images of childhood in the West show that children are taken care of by their guardians (e.g., being clean and well dressed),14 which matches with the Western perception of childhood. Therefore, we hypothesize that the images in the five terrorist organizations’ magazines will reflect the perceptions and thinking of each specific terrorist organization, regarding children, in a similar manner.

This article develops an important but not yet systematically studied area in terrorism studies. It focuses on two representations that previous research has just begun to grapple with for the purpose of furthering understanding of the role that children play within these terrorist groups generally and their propaganda specifically: (1) children as perpetrators of violence, which we term “child perpetrators,” and (2) children as victims of Western-backed warfare, which we term “child victims.” Previous studies have only researched these representations in one magazine: Dabiq, and social media research has primarily focused on Islamic State (IS)’s depiction of children. This article broadens the scope of analysis by studying five magazines across four terrorist organizations: Dabiq (IS), Inspire (Al Qaeda), Azan (Taliban), Gaidi Mtanni (GM) (al-Shabaab), and Jihad Recollections (JR) (Al Qaeda). This article also analyzes the different gender portrayals in these images and changes in image type across time. Although all five magazines contain photographs of children, Dabiq and Inspire have the highest number, and more prominent, developed trends than the other three publications.

Literature review

The extant literature on child images in online terrorist propaganda is primarily focused on social media content. Bloom, Horgan, and Winter15 and Benotman and Malik16 both created databases of child images from IS online propaganda as circulated on social media sites. Bloom et al. collected eighty-nine images of child “martyrs” from Twitter and Telegram between January 2015 and January 2016 and compared this with a control database of 114 images of adult “martyrs.” They found that not only did the number of child images increase on a monthly basis over the time period studied, but that the child images bore remarkable similarities to the adult images, concluding that child “martyrs” appeared to be treated the same as adult “martyrs.” Additionally, they noted that IS’s use of children is normalized by representing them as simply “heroes” instead of “young heroes.” Bloom et al. argued that this ultimately comes down to a psychological warfare technique to emphasize strength and create fear among IS’s enemies. Benotman and Malik, on the other hand, collected 254 images from sites such as Twitter, archive.org, and justpaste.it between August 2015 and February 2016. They proposed that five main themes emerged: participation in violence, normalization to violence, state building, utopia, and foreign policy grievances. Benotman and Malik noted that the majority of the propaganda included children as the perpetrators of violence or children witnessing and becoming normalized to violence, with the next most prominent theme being state building. Again, they argued that these techniques aim to instill fear in their enemies and legitimize IS’s state-building project.

Christien17 is the only researcher (at time of writing) to have analyzed child images in a jihadist online magazine. Christien studied the representation of youth in IS’s Dabiq by analyzing the text and images contained in the first eight issues (from 2014 to 2015). Christien analyzed whether Giroux and Males’s theory of the myth of childhood innocence appeared in Dabiq and found that “childhood innocence” was the most dominant representation of children and youth; found in almost half of the data set. Other prominent themes found were references to children as weak and victims of the West; as material commodities, with girls described as slaves; and as perpetrators of violence. Christien theorized that children are portrayed in these ways, first, to elicit anger and frustration within IS’s target audience, and second, to portray their social and institutional rules and legitimize their long-term goal of building a powerful state. Christien noted that the representation of children as perpetrators of violence began to increase in issues 7 and 8 of Dabiq and suggested that research into whether this continued and increased was an area for future study.

According to Rhodes,18 as adults, we tend to view children as the next generation of adults, and invest in them accordingly our hopes for the future. Although historically not always the case in Western nations, we have now reached a point in which we generally perceive children to be (and hope for them to be) carefree innocents spared of adult responsibilities, worries, and stresses,19 with an overwhelming view that children require protection.20 Faulkner21 argues that there are few issues in Western society that provoke outrage in the same manner as that of the threat to childhood innocence, including but not limited to: abuse, neglect, violence, and sexualization. This view is in stark contrast with the current view and use of children by terrorist organizations.

Current literature has revealed that children are being used by terrorist organizations, particularly IS, like never before.22 In the past, the use of children as perpetrators of violence in war and terrorism has only been seen in cases of desperation23 and organizations have been shy in advertising this.24 However, IS in particular understand the importance of planning ahead in order to achieve their ambition of building a state that will last.25 The recruitment, indoctrination, and training of the next generation are how they plan to sustain their state.26 Terrorists understand that children are more impressionable27 and indoctrinating individuals into their worldview from a young age minimizes the chances of their fighters becoming converted to any other way of life, thus creating a stronger generation of fighters.28 Advertising child perpetrators in their propaganda conveys that their violence has become a family affair29 and consequently achieves a shock factor that guarantees their consistent appearance in Western media. This consequently results in counterterrorism strategies becoming trickier for the West and sends the message that they are prepared to fight for as long as it takes.30 On the other hand, their images of children as innocent victims of Western-backed warfare aim to fulfill a different agenda. As mentioned in Christien’s study, the main aims of these images are to generate anger and frustration in viewers.31 They hope that the feelings of anger and frustration generated lead to further action by their supporters, and persuade people to join as new recruits. Additionally, they may be aiming to use these images as proof of their claims that the West is “evil,” and to condone the attacks that their organization undertakes in the West.

The literature search into children in terrorist organizations highlighted that the roles that children play in terrorist organizations are gendered, although one limitation to this literature is that there is a disproportionately narrow focus on IS. Nevertheless, the general consensus appears to be that boys are given military training, which includes but is not limited to learning how to use weapons, martial arts, and studying the Quran.32 After this training is complete, boys are expected to fight alongside their adult counterparts on the battlefield.33 Boys are even expected to undertake executions as this will desensitize them to violence and eradicate remorse from a young age, allowing them to become brutal adult fighters.34 Other noted tasks that boys are given are suicide missions, manning checkpoints, and undertaking security patrols.35 Girls on the other hand, play a very different role and are often referred to as the “flowers and pearls of the Caliphate.”36 IS in particular keep girls as concubines for their fighters, which reportedly consists of girls being subjected to rape and forced marriage, from as young as eight years old.37 Furthermore, girls must be veiled at all times and remain in their houses.38

Terrorist organizations are increasing their use of children in their online propaganda in more ways than one. Several researchers have put forward theories of why this could be. Singer theorizes that these organizations are playing on Western views of childhood innocence, and mentions a quote from the Taliban, “Children are innocent, so they are the best tools against dark forces.”39 Anderson40 and Pinheiro41 argue that terrorists understand that first, children are less likely to arouse suspicion, and second, due to Western perceptions of children, the West will find it difficult to know how to respond to these images. This may be the case; however, it is clear that further analysis needs to be undertaken to develop more sophisticated understandings of these images.

Method

The first online magazines in this dataset were published in 2009 and the last in 2016. The issues included are shown in . A database was created to collect all ninety-four child images published in this time. The researchers searched through each magazine issue to identify the images and extracted them into a database. The only criteria during this process were that each image must include one or more children. This research used the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child’s definition of a child,42 which is an individual under 18 years old.43

Table 1. Magazine issues included in study.

There were two stages to coding the resultant dataset. The first determined whether the child perpetrator and child victim themes found in the first eight issues of Dabiq by Christien could be confirmed, and second, were also present in the other four magazines. Within the child victim theme we further coded the images as either vulnerable child or dead/injured child. We defined a child as vulnerable when they appeared to be scared or sad. Dead and injured children were coded together as both depicted events where violence had occurred. We noticed another theme within the magazines—that of happy children. This refers to images in which children were depicted at play, happy, and in good care of the organizations. We termed this category “Fulfilled children.”44 During this coding stage, we became aware that the child’s gender was an important factor (, and ). However, there were some images where both genders were present in an image and we refer to these images as “Mixed.” Finally, we noted that children were either presented solely or as a group ( and ). Therefore, the entire dataset was coded at this stage according to the following categories: child perpetrators; child victims; fulfilled children; males; females; mixed; solo; and group.

In the second coding stage, we applied Bednarek and Caple’s45 news value framework to all the images. This systematically investigates what values the images hold that result in them being classed as more “newsworthy” than others.46 The analysis of news values in this framework includes the “qualities” and “elements” that make the image newsworthy enough to be included in the publication.47

News values have previously been studied from cognitive perspectives48 and are defined by Richardson49 as "the (imagined) preferences of the expected audience." Bednarek and Caple's50 news value framework, in contrast, is primarily discursive; that is, it considers the linguistic and visual means via which news values are realized in media (news) texts. This discourse analysis takes two considerations into account regarding how images construct news values.51 First, the contextualization of the participants in the image: where they are photographed and who with, and how much or little is shown in the image.52 Second, technical considerations, for example, shutter speed, focal length, aperture, and angle. Furthermore, there is no one-to-one relationship between devices and the news values; they can construct more than one news value.53

The news values that Bednarek and Caple examine are prominence, negativity, superlativeness, novelty, impact, personalization, and aesthetics.54 Bednarek and Caple define prominence as the "high status of individuals, organizations or nations" in the event photographed. Therefore in this study, prominence was coded using indicators of high status among the children in the images, such as receiving training/education. Negativity is defined as “the negative aspects of an event" and, therefore, in this study was coded through indicators of negative occurrences experienced by the children in the images; being vulnerable, injured, or killed. This news value overlaps with our first-stage coding, specifically the labels “vulnerable” and “dead/injured.” Superlativeness is defined as “the maximized or intensified aspects of an event," and was thus coded when the activities were portrayed as large, extreme or intense such as large groupings of children. Novelty is defined as the "unexpected aspects of an event," which was coded as anything that was thought to be unusual or surprising in the child images. Impact is the “effects or consequences of an event,” which was coded as the aftermath of acts committed on or by children. Personalization is defined as "the personal or human interest aspects of an event," which was coded through the display of children’s emotions in the images. Aesthetics is defined as "the ways in which images are balanced through their compositional configurations," and was coded whenever there was noticeable photography techniques used in the images of children. It is important to note that multiple coding of these values were used; for example, superlativeness and personalization would be the display of extreme emotions. This makes it possible to have totals in the analysis that equal greater than 100 percent. displays Bendarek and Caple’s definitions of news values and their adapted realization in the present study.

Table 2. Gender composition of children in images.

Table 3. Gender composition of child perpetrators images.

Table 4. Gender compositions in fulfilled children images.

Table 5. Group and solo depictions of children within images.

Bednarek and Caple’s news value framework was chosen, first, because the magazines are used in part to disseminate news of the respective jihad groups, their designs being quite similar to Western newspapers/magazines. Second, the framework aims to reveal the specific values that the terrorist organization qua the photographer aims to convey to the target audience (i.e., followers and potential recruits), and how these values are interpreted by this audience, and consequently, how the audience is influenced by these values.55 This should allow us to gain deeper insight into how terrorists are trying to influence their Western readers and potentially allow us to attempt to create effective counter-images.

The final analysis (see section “Trends Across Time”) that was undertaken post-stage 1 and 2 coding was to identify and calculate changes and/or continuity in use of the observed themes over time and was only carried out for Dabiq and Inspire because the three other magazines did not have enough images or developed enough themes to do so.

Results

First stage of coding: Content analysis of child images

Gender

Overall there are a far higher number of images containing male children than female children in the dataset. Inspire and Dabiq in particular feature a large amount of images of males with Dabiq containing a 1:5 ratio of girls to boys.

Group photos and solo photos

Overall there is a near even split between images of children portrayed alone and images of children grouped together or with others. Inspire contains a larger proportion of images depicting children alone than grouped together while Dabiq contains a near 50/50 split.

Child perpetrators

In all magazines bar Dabiq, child perpetrators are a rarity (17/19). Both Inspire and GM contain one apiece while Azan and JR have none. They are uniformly male across the magazines. There is a theme of solo child perpetrators to be depicted gun in hand, in proximity to a murdered enemy while groups of child perpetrators are not shown violently; they are either stood to attention or praying.

Fulfilled children

This category amounts for twenty of the ninety-four-image dataset (21.5 percent). It is found most often in Dabiq where IS attempts to promote the good life awaiting children within the caliphate, where children are held smiling in the arms of the fathers and girls live the lives of idyllic innocents.

Child victims

The largest category of images found in the dataset concerns child victims, specifically, child victims of Western violence or aggression.

Overall, Inspire has the highest number of these images as shown in ; of the twenty-four images of children present within the magazine 87.5 percent concern the portrayal of children as victims of Western, or Western-backed, violence. Within Inspire, children were more likely to be portrayed as vulnerable (12/24) rather than dead (9/24); there were more images of children stood among the rubble of buildings than under it.

While the victims depicted are predominantly male (34/50), Dabiq and Inspire do not shy away from showing dead girls with four images of dead girls between them. However Inspire depicts girls as vulnerable (2/21) whereas Dabiq does not, opting instead to depict them solely as fulfilled children. Two images are classified as “Unknown” in terms of gender due to the bloody nature of the image obscuring the gender of the child from the viewer.

Diachronic analysis: “Trends across time”

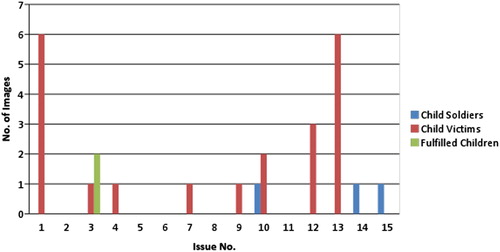

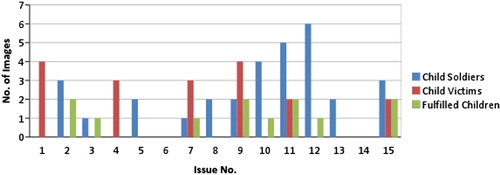

As we coded the images we noticed how depictions of children have changed over time in Inspire and Dabiq. shows the changes that have occurred in Inspire over the course of their publications and shows the same for Dabiq.

Figure 1. Number of images that contain child perpetrators, victims, and fulfilled children in Inspire.

Figure 2. Number of images that contain child perpetrators, victims, and fulfilled children in Dabiq.

Inspire starts off by featuring six images of dead or injured children in Issue 1 and the trend remains fairly consistent. It decreases slightly in issues 2–8 but in issues 10, 12, and 13 they return to three to five images of dead or injured children per issue. There are very few images of fulfilled children or child perpetrators overall. There is one image of a child perpetrator and in the other two the theme of using children to humanize adults return. One in particular features a smiling Osama bin Laden holding a smiling child. Despite having twenty-four images of children, Inspire has not been consistent with depicting children; it has five issues with no children at all. The two highest counts of these images can be seen in two issues in particular; issue 1 and issue 13 and they are predominantly negative. The articles these images feature in often concern “the sins of the West.” They include an interview with Abu Basir, an article called “The West should ban the Niqab covering its Real Face” and “Letter to the American People.”

Interestingly Dabiq depictions have changed over its existence. While initially they kept in line with the practices of Inspire they have gradually phased out negative depictions of children for depictions showcasing child perpetrators and fulfilled children. After issue 9 there are only four negative images spread over six issues, compared to eleven images of child perpetrators and six fulfilled child images. Child perpetrators and fulfilled daughters dominate images post issue 10. Three of the negative depictions concern the treatment of children in the West, namely a child being raised by two mothers, and the treatment of Syrian refugees. Also in contrast with Inspire, Dabiq contains at least one image of a child in thirteen of its fifteen issues. There is a predominant theme emerging for personalization; 83.7 percent of images seek to personalize the child to the viewer.

Second stage of coding: News values in child images

The second stage of coding involved the application of Bednarek and Caple’s news value framework to all the images. shows the frequency of use (in raw and percentage figures) of each news value in the dataset. No uses of the “Novelty” news value were observed in the dataset. Therefore, the news value has not been included in .

Table 9. All news values across all magazines.

Table 10. Prominence in child perpetrator imagery.

Table 11. Personalization in “child perpetrators” imagery.

Table 12. Prominence in fulfilled children imagery.

In terms of key patterns (), Prominence (42/94), Negativity (51/94), and Personalization (81/94) are the most frequently observed news values. The majority of imagery containing the Prominence news value is found in Dabiq (29/42), whereas the majority of imagery containing the Negativity news value is split between Dabiq (17/51) and Inspire (21/51). The Personalization news value is found regularly in Inspire (18/24), Dabiq (41/49), Gaidi Mtanni (6/10), and Azan (5/7), but largely absent in Jihadi Recollections (1/4). The Impact news value is highly present within Inspire (20/24) and Azan (7/7) but relatively scarce in Dabiq (20/49) and Gaidi Mtanni (3/10).

The following section reports the results of applying the news values framework to the subcategories found in the first stage of coding; specifically to the child perpetrator, fulfilled children, and child victims categories.

Child perpetrator

Images of child perpetrators are mainly found in Dabiq, and are depicted using three news values: prominence, personalization and aesthetics.

As shown in , all the images of child perpetrators use the prominence news value to highlight the high status given to child perpetrators and emphasize the importance of the military arm of Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and Al-Shabaab. Dabiq display prominence in how each and every child perpetrator is dressed immaculately in military uniform, whereas, the single instance of child perpetrators in Inspire and Gaidi Mtanni are dressed in nonmilitary plain clothes. Half of child perpetrator images contained weapons emphasizing the high status and important responsibility that child perpetrators bear. This, along with the use of personalization and aesthetics, underpins depictions of child perpetrators within the dataset.

shows the majority (16/19) of the imagery of child perpetrators in the dataset makes use of the personalization news value by drawing attention to the faces of the perpetrators. A common theme throughout is their portrayal as stone-faced, emotionless killers or as uniformed zealots deep in prayer. Only in one instance is the child perpetrator depicted masked.

Eleven of the nineteen child perpetrator images make use of the aesthetics news value. The primary technique used in Dabiq is the aesthetic use of focus (9/49). The backgrounds of images containing child perpetrators are kept out of focus in order to draw the eye toward the faces of the perpetrator(s) in the foreground. In this way the use of focus is complementary to the use of the personalization news value. The use of bright colors (3/19) is mainly in the background too, child perpetrators are posed against white backdrops or, in one case, blue skies.

Fulfilled imagery of children

The prominence news value is () in a majority of the images of fulfilled children (16/20). Prominence is found most often in Dabiq where IS attempts to promote the good life awaiting children within the caliphate (10/20). Across the magazines prominence is utilized in depictions of children being educated (5/20) by the organization, being held in the arms of their presumed fathers (5/20), and in the case of GM in mass protests (3/20).

Personalization is heavily used in depicting fulfilled children as shown in . Dabiq utilizes it in every one of its twelve images. The focus of these images is drawn to the smiling faces of young children in the arms of their parents, at play, and the inquisitive faces of young boys being taught in school. Jihadi fighters are humanized by the presence of smiling children in their arms in Dabiq but this also occurs in an instance in Inspire where Osama bin Laden is pictured holding a young girl with both parties smiling.

Similar to their use of the aesthetics news value when depicting child perpetrators, Dabiq makes use of soft focus (4/12) on the background in order to draw the viewer’s eye to the face of the child in question; however, this technique is also used to personalize the adults that often accompany these children as smiling father figures. Similarly again to child perpetrators, there is a use of bright colors in backgrounds but unlike child perpetrators there are also instances of children dressed in bright clothing.

Child victims

The largest category of images found in the dataset concerns child victims, specifically, child victims of Western violence or aggression. A variety of news values are employed here namely negativity (50/50), personalization (36/50), impact (49/50), superlativeness (28/50), and aesthetics (30/50).

The Negativity news value is found in every Child Victim image and is thus identical to the Child Victims table coded in the first stage of coding.

Despite having over twice the number of child images of Inspire, only 34 percent of Dabiq’s images contained these images of children. Dead or injured children in Dabiq are, like in Inspire, often portrayed alone. This makes up the largest portion of images that use the negativity news value. Also, Dabiq were more likely than Inspire to show gory blood-filled images of child victims. Less than half of the small number of images in GM contained these images, all of Azan’s images and half of JR.

The negativity news value is supported through use of other news values, mainly those of impact (), personalization (), superlativeness (), and aesthetics ().

Table 15. Personalization in “child victim” imagery.

Table 16. Superlativeness in “child victim” imagery.

Table 17. Aesthetics in “child victim” imagery.

Table 18. Gender and negativity in child victim imagery.

It is not a coincidence that, barring one image in Inspire, (for the presence of negativity news values) lines up exactly with . The photographs of child victims are shot in the context of the impact of Western-backed warfare. In Dabiq dead and injured children are portrayed in bloody rags. In Inspire vulnerable children sit in bombed ruins and cities and dead children are mourned by their friends and families.

Personalization is a dominant news value in all the magazines when depicting child victims. In particular it is used often in Inspire, Dabiq, and GM. Inspire personalizes vulnerable, injured, and dead children by either placing them alone at the center of the frame or by having other figures within the frame looking at them. It is used in the images to engender an emotional response from the viewer. The emotions that Inspire focuses on are sadness, anger, and pain.

Superlativeness is defined as the maximized or intensified aspects of an event. When applied to the child victims' dataset there are several incidences of superlativeness. In Inspire and Azan there is a tendency to group injured and dead children together in order to intensify the negative aspects of the event. Likewise the emotions of vulnerable children and mourning parents are generally intensified; vulnerable children cry while mourning parents wail or appear to be shouting furiously.

Aesthetics are present in Azan, Inspire, and Dabiq while being absent from GM and JR. In terms of aesthetic effects there are several key trends. Inspire makes use of filters and graphics primarily (11/24). These graphics tend to be overlaid text written in either English or Arabic. Aesthetic use of focus is the primary technique in Dabiq (14/49) and is often used to draw the reader’s eye to the face of the pictured child. Due to the low density of images overall in Azan the use of aesthetics is localized in one article that deals with the death of children at the hands of the West. Each image contains either a group of dead children or a dead child held in the hands of a grieving adult; each image is darkened by a filter. Within the used framework high camera angles are said to be used to denote negativity while high angles are said to promote prominence. Low angles are largely absent from the dataset and high angles are used just as much in negative images as in prominent. The majority of images in Dabiq (71.4 percent) are shot from a straight angle. This goes against the expected use of low and high camera angles to denote prominence and negativity. High camera angles appear in twelve images while low camera angles appear in the remaining two. Likewise, in Inspire, AQAP are not making use of high and low camera angles as much as was expected. The majority of images are shot in a straight on angle (75 percent) while 25 percent are shot using a high angle.

Discussion

This study collected the ninety-four images that contained a child or children in the five magazines between 2009 and 2016. The first coding stage identified whether the child perpetrator and child victim themes found in Christien’s Dabiq study were present in the other magazines. This stage further identified the fulfilled children category, that gender was an important theme, and whether or not the children were presented solely or as a group. The second coding stage applied Bednarek and Caple’s news value framework to the images. The final stage applied a diachronic analysis in order to identify the changes and/or continuity in use of the observed themes over the course of the issues for Dabiq and Inspire. This section will integrate and discuss the results of all three stages: content analysis, diachronic analysis, and the news value analysis.

It can be seen from the analysis that first, overall there are a considerably higher number of images containing boys than girls throughout the five publications. It could be argued that this makes sense given that the literature identified that men play primary roles in the organizations and women play more supportive secondary roles.56 Second, children are shown almost equally on their own as they are in groups across the magazines. This is likely because each representation can further emphasize the organization’s message, for example, when attempting to display strength they can photograph large groups, or when attempting to display vulnerability, they can photograph a lone child. Finally, both Dabiq and Inspire contain a significantly larger number of child images than Azan, GM, and JR. This is either simply due to the fact that these publications have a larger number of issues, or because these two organizations see a greater benefit in utilizing children in their propaganda than Azan, GM, and JR. Finally, the analysis revealed the three main roles that children play in these publications: child perpetrators, fulfilled children, and child victims, all of which are affected by gender in some form.

Child perpetrators

Dabiq was the only publication that included a compelling number of child perpetrators, which confirms the literature that states that IS are using children in ways unlike ever before.57 They displayed child perpetrators through utilizing the prominent, personalization, and aesthetic news values. The child perpetrators were always male and shown as possessing high status in the group through prominence; this is indicated by wearing an immaculate military uniform, carrying weapons, and standing in proximity to murdered enemies. Additionally, prominence is also shown through undertaking other important activities such as praying. The show of high status is likely to entice readers who perhaps wish to gain that status and a sense of belonging for themselves and/or their children. In contrast, children who were not committed IS child perpetrators were displayed as being poor and hungry which signifies low status with the threatening purpose that this is the destined unpleasant and unvalued life for children who do not join them.

The personalization and aesthetic news value were used simultaneously; the aesthetic use of focus was used to draw attention to the faces of child perpetrators and personalization was used to display emotions, or rather, the lack of emotion. The child perpetrators in the images can be described as being stone-faced and emotionless, which is likely intended as a psychological warfare technique to display the brutality they have managed to instill and the children's abilities to kill. Further, as mentioned in the literature, these images could be used to prove that IS are training their strongest fighters yet and want to show their enemies that they have the ability to fight for a very long time.

An interesting observation was that only one image contained a masked child perpetrator. Although we did not compare child images with adult images, our anecdotal observation was that adults are often masked in images in these publications. Therefore, we theorize that children are not masked because they are relying on the contrast of fierceness and brutality with youthful faces to achieve their psychological warfare technique.

It is possible that the other publications did not want to portray children in this way for a variety of reasons. One example may be that they believe exploiting children will portray them negatively and thus reduce support from followers. This is possible in GM, which included images of children protesting peacefully. Conversely, Inspire, JR, and Azan focused on using children as victims, suggesting that they are more concerned with creating guilt and anger at the West than psychological warfare and training their next generation.

Fulfilled children and gender

Fulfilled children are what we have termed images that depict children at play, children that are happy, and children that are well-taken care of by the organization. Again, this is found mostly in Dabiq and uses the prominence, personalization, and aesthetic news values. Unlike child perpetrators, this trend found that the images included both boys and girls; however, there were differences between the genders. Children are displayed using the prominence news value to highlight that children are highly valued and the caliphate is an ideal place for children to flourish. Both genders are shown as being clean and well-dressed; however, boys are shown as receiving an education and training for an important role, such as fighting on the battlefield. Girls on the other hand, are shown as being held and protected by strong-looking adult males (most likely their fathers). Mothers are completely absent from the child images in these publications which is unlike images of the typical nuclear family often depicted in the West. We theorize that girls are portrayed in the arms of their fathers to convince their supporters that life is safer for them in the organization than in the West and that they will be respected and well-protected in the Caliphate.

Personalization and aesthetics are used again simultaneously; however, in this category, focus is used to draw attention to the smiley, happy faces of children playing, receiving an education, and being held in the arms of their fathers. This also occurs in regard to the fathers holding the girls, which is thought to humanize IS members as kind and loving individuals. These images also make use of bright colors both in terms of background and clothes. This use of color is thought to highlight the fulfilled emotions displayed in these images and emphasize that the Caliphate is a pleasant place to live.

Overall, we conclude that portraying girls as behaved, well-dressed, smiling, and protected, paints a picture that females in the organization are “idyllic innocents.” In opposition, Dabiq includes an image of a Western girl, holding a protest sign declaring that she has two mothers. In contrast, this image displays that they believe that girls raised in the West engage in rebellious forbidden behavior.

Child victims

Child victims are the largest category of images in the dataset and include images of children as victims of Western violence and aggression. This trend contained males and females but did not make any distinctions between them. The news values included are negativity, personalization, impact, superlativeness, and aesthetics.

Inspire has the largest number of child victim images; however, Dabiq does contain a small number also, and all of Azan's small dataset contains negativity. Negativity is used in these images through showing children as vulnerable, injured, and dead. Negativity was used simultaneously with impact and superlativeness to emphasize the gore, sizes of groups, and reactions of victims and mourning parents, particularly in Dabiq, to achieve maximum impact. Dabiq only has two images of dead female children and zero vulnerable female children, which confirm the earlier theory that they wish to portray their territory as a safe place for females. Azan mostly displayed images of dead or injured children, whereas Inspire showed more vulnerable images that were less gory. This may have been intentional as they might believe that gory images of dead children would be too much for their readers to handle and subsequently push them away from looking at these images. Inspire was also more likely to display lone children than groups, which is thought to highlight the vulnerable nature of the child victims.

Personalization and aesthetics are used again simultaneously; however, this time they are used in Inspire, Dabiq, and GM by placing the child victims at the center of the frame or by having other figures within the frame draw attention to them by looking at them. Again, there is a focus on the faces of the children. The purpose of this is likely to be that this is the body part that is most likely to instill a sense of shame, anger, frustration and guilt in readers because this is the part of the body that elicits emotions. The main emotions displayed in these images were sadness, anger, and pain. Additionally, Azan used aesthetics to darken their child victim images to emphasis the negativity and sadness of these images. We therefore support Christien's theory that these images are intended to create anger and frustration in their Western followers.58

Trends across time

Trends across time were only analyzed for Dabiq and Inspire because the other three publications did not have enough images or developed themes to do so. Inspire’s technique of portraying children as victims of the West remains throughout all of their issues despite five of the issues not containing any images of children. In contrast, Dabiq changes from mainly child victim images containing negative and personalization values to child perpetrator and fulfilled child images from around issue 8 onward, containing mainly negative and prominence values. Dabiq also contains at least one child image in thirteen out of its fifteen issues. This change in Dabiq indicates that IS saw a need for change to ensure their longevity and ensure their goal of achieving a state, and chose to do so by using their next generation of fighters and wives/mothers. However, it is important to note that these trends may have been affected by the content for child victim images in Inspire being more opportunistic than the child perpetrator content in Dabiq because they appear to rely on their child victim images from attacks undertaken by their enemies.

Conclusion and recommendations for further research

The aim of this article was to analyze the images of children across five online terrorist magazines in order to better understand the roles and representations of children in these organizations. Dabiq contained the most images and its main finding was a change in focus from child victims of Western-backed warfare to their use of fierce, prestigious child perpetrators, and a focus on how children can flourish under the caliphate. Dabiq was also the only publication to exploit both genders in their images, using images of girls to help portray the Caliphate as a pleasant place to live. They most likely chose these images and strategies to fulfill their aim of longevity and state-building. Inspire also had a large number of images; however, the main trend was focused on images of child victims that aimed to evoke anger, shame, frustration, and guilt in their readers for the Western-backed warfare in the Middle East. Despite having a very small number of images, Azan also focused on portraying children as victims and used aesthetics to emphasize sadness. Although GM had a very small number of images, they tended to show the children in their organization supporting their cause in a more peaceful manner than the other organizations. JR contained a very small number of images and did not appear to comprise any re-occurring trends.

The most obvious consideration is continued analysis of these publications as new issues are published. Additionally, it would be useful to continue the research in the IS's more recent publication Rumiyah and Jabhat al Nusra’s Al Risalah. While Dabiq is focused on promoting the IS caliphate through shows of strength, Rumiyah has thus far been focused on inspiring lone actors to attack in the West. It would be interesting to see if the editors of Rumiyah utilize images of children in the same way as Dabiq or if they subscribe to Inspire’s methods. It would also be valuable to compare this dataset with other datasets such as images of adult perpetrators and adult victims in the magazines in order to investigate potential differences.

There is also the possibility of applying this news value framework to other propagandistic material produced by these violent jihadist groups. The magazine style publications covered in this study form only part of the volume of material ISIS, Al Qaeda, Al-Shabaab, and other groups produce. This framework could equally be applied to datasets of jihadist images and videos. It would be interesting to observe if the trends observed in these magazines are replicated in widely shared images and videos. The role of children has become highly newsworthy in Western news media with events such as the Manchester Bombing and the U.S. January failed raid in Yemen dominating the media landscape; an analysis of how these events are covered by jihadist groups across media platforms would be conducive to further understanding the role of children in these conflicts.

Notes

Table 6. Group and solo depictions of child perpetrators within images.

Table 7. News values and realization in present study.

Table 8. Gender composition of dead or injured and vulnerable children images.

Table 13. Personalization in “fulfilled children.”

Table 14. Impact in “child victims” imagery.

Notes

1 Brandon Colas, “What Does Dabiq Do? ISIS Hermeneutics and Organizational Fractures within Dabiq Magazine,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 40, no. 3 (2016), 173–190; Haroro Ingram, “An Analysis of Islamic State’s Dabiq Magazine,” Australian Journal of Political Science 51, no. 3 (2016), 458–477; Julian Droogan and Shane Peattie, “Reading Jihad: Mapping the Shifting Themes of Inspire Magazine,” Terrorism and Political Violence 30, no. 4 (2016), 684–717; Anthony Lemieux, Jarret Brachman, Jason Levitt, and Jay Wood, “Inspire Magazine: A Critical Analysis of Its Significance and Potential Impact through the Lens of the Information, Motivation, and Behavioral Skills Model,” Terrorism and Political Violence 26, no. 2 (2014), 354–371; Susan Sivek, “Packaging Inspiration: Al Qaeda’s Digital Magazine Inspire in the Self-Radicalization Process,” International Journal of Communications 7 (2013), 584–606; Haroro Ingram, “An Analysis of the Taliban in Khurasan’s Azan (Issues 1–5),” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 38 (2015), 560–579.

2 Droogan and Peattie, “Reading Jihad”; Christoph Gunther, “Presenting the Glossy Look of Warfare in Cyberspace—The Islamic State’s Magazine Dabiq,” 9, no. 1 (2015); Haroro Ingram, “Analysis of Islamic State’s Dabiq Magazine,” Australian Journal of Political Science 51, no. 3 (2016), 458–477; Haroro Ingram, “An Analysis of Inspire and Dabiq: Lessons from AQAP and Islamic State’s Propaganda War,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 40, no. 5 (2016), 357–375; Haroro Ingram, “An Analysis of the Taliban in Khurasan’s Azan (Issues 1-5), Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 39, no. 7 (2015), 560–579; Anthony F. Lemieux, Jarret M. Brachman, Jason Levitt, and Jay Wood, “Inspire Magazine: A Critical Analysis of its Significant and Potential Impact Through the Lens of the Information, Motivation, and Behaviour Skills Model,” Terrorism and Political Violence 26, no. 2 (2014), 354–371; Celine M. I. Novernario, “Differentiating Al Qaeda and the Islamic State Through Strategies Publicized in the Jihadist Magazines,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 39, no. 11 (2016), 953–967.

3 Kyle J. Greene, “ISIS: Trends in Terrorist Media and Propaganda,” International Studies Capstone Research Papers, 3 (2015), 1–57; Maura Conway, Jodie Parker, and Seán Looney, “Online Jihadi Instructional Content: The Role of Magazines, in ed. Maura Conway, Lee Jarvis, Orla Lehane, Stuart Macdonald, and Lella Nouri, Terrorists’ Use of the Internet: Assessment and Response (Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2017), 182–193.

4 Carol K. Winkler, Kareem El Damanhoury, Aaron Dicker, and Anthony F. Lemieux, “The Medium is Terrorism: Transformation of the About to Die Trope in Dabiq,”Terrorism and Political Violence (2016), 1–20.

5 Anthony Lemieux, Jarret Brachman, Jason Levitt, and Jay Wood, “Inspire Magazine: A Critical Analysis of Its Significance and Potential Impact through the Lens of the Information, Motivation, and Behavioral Skills Model,” Terrorism and Political Violence 26, no. 2 (2014), 354–371.

6 Julian Droogan and Shane Peattie, “Reading Jihad: Mapping the Shifting Themes of Inspire Magazine,” Terrorism and Political Violence 30, no. 4 (2016), 684–717; Brandon Colas, “What Does Dabiq Do? ISIS Hermeneutics and Organizational Fractures within Dabiq Magazine,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 40, no. 3 (2016), 173–190.

7 Noman Benotman and Nikita Malik, “The Children of Islamic State,” The Quilliam Foundation (2016), 1-100.

8 George Stenberg, “Conceptual and Perceptual Factors in the Picture Superiority Effect,” European Journal of Cognitive Psychology 18, no. 6 (2006), 813–847.

9 Wayne Wanta and Virginia Roark, “Cognitive and Affective Responses to Newspaper Photographs,” Paper presented to the Visual Communication Division at the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication annual conference, Kansas City, MO (1993).

10 Dolf Zillmann, Silvia Knobloch, and Hong-sik Yu, “Effects of Photographs on the Selective Reading of News Reports,” Media Psychology 3, no. 4 (2001), 301–324.

11 Nicole Smith Dahmen and Daniel Morrison, “Place, Space, Time: Media Gatekeeping and Iconic Imagery in the Digital and Social Media Age,” Digital Journalism 4, no. 5 (2016), 658–678; Vicki Goldberg, The Power of Photography: How Photographs Changed our Lives, (New York: Abbeville Press, 1991); David Perlmutter, Visions of War: Picturing Warfare from the Stone Age to the Cyber Age (New York: St. Martin’s Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1999); Barbie Zelizer, About to Die: How News Images Move the Public (Oxford University Press, 2010).

12 Maxine Rhodes, “Approaching the History of Childhood: Frameworks for Local Research,” Family & Community History 3, no. 2 (2000), 121–134, at 125.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Mia Bloom, John Horgan, and Charlie Winter, “Depictions of Children of Youth in the Islamic State’s Martyrdom Propaganda 2015–2016,” CTC Sentinel 9, no. 2 (2016), 29–32.

16 Noman Benotman and Nikita Malik, “The Children of Islamic State,” The Quilliam Foundation (2016), 1–100.

17 Agathe Christien, “The Representation of Youth in the Islamic State's Propaganda Magazine Dabiq,” Journal of Terrorism Research 7, no. 3 (2016), 1–8.

18 Maxine Rhodes, “Approaching the History of Childhood: Frameworks for Local Research,” Family & Community History 3, no. 2 (2000), 121–134.

19 Ibid.

20 Virginia Morrow, “Understanding Children and Childhood,” Centre for Children and Young People Background Briefing Series, no. 1. (2nd ed.). Lismore: Centre for Children and Young People, Southern Cross University (2011).

21 Joanne Faulkner, The Importance of Being Innocent: Why We Worry about Children (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

22 Francesca Capone, “‘Worse’ than Child Soldiers? A Critical Analysis of Foreign Children in the Ranks of ISIL,” International Criminal Law Review 17 (2017), 161–185.

23 Peter Singer, Children at War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

24 Kara Anderson, “‘Cubs of the Caliphate’: The Systematic Recruitment, Training, and Use of Children in the Islamic State,” International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (2016), 1–46; Capone, “‘Worse’ than Child Soldiers?”

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Cole Pinheiro, “The Role of Child Soldiers in a Multigenerational Movement,” CTC Sentinel 8, no. 2 (2015), 11–13.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 Christien, “The Representation of Youth in the Islamic State's Propaganda Magazine Dabiq.”

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Priyanka Motaparthy, “‘Maybe We Live and Maybe We Die’: Recruitment and Use of Children by Armed Groups in Syria,” Human Rights Watch (2014).

35 Pinheiro, “The Role of Child Soldiers in a Multigenerational Movement,” 11–13.

36 Noman Benotman and Nikita Malik, “The Children of Islamic State,” The Quilliam Foundation (2016), 1–100.

37 Cathy Otten, “Yazidis Tell How Fearful Isis Kept Them on Move," The Independent, 10 April 2015, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/yazidis-tell-how-fearful-isis-kept-them-on-move-10169024.html (accessed January 2017)

38 Charlie Winter, “Women of the Islamic State: A Manifesto on Women by the Al-Khansaa Brigade,” Quilliam Report (2015), 1–41.

39 Peter Singer, Children at War (University of California Press, 2006).

40 Anderson, “Cubs of the Caliphate.’”

41 Cole Pinheiro, “The Role of Child Soldiers in a Multigenerational Movement,” CTC Sentinel 8, no. 2 (2015), 11–13.

42 As none of the images came with age information, the researchers made the decision to only include children whom we were confident visually looked younger than 18 years old; however, we cannot be completely certain that no mistakes were made.

43 United Nations Humans Rights Office of the High Commissioner (1990) Convention on the Rights of the Child, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx (accessed January 2018).

44 The term “fulfilled” has come from Macdonald and Lorenzo-Dus who used “fulfilled” as a category in their jihadist image study: Stuart Macdonald and Nuria Lorenzo-Dus, “Visual Jihad: Constructing the ‘Good Muslim’ in Online Jihadist Magazines,” Under Consideration (2018).

45 Monika Bednarek and Helen Caple, “‘Value Added’: Language, Image and News Values,” Discourse, Context & Media 1, no. 2 (2012), 103–113.

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid.

48 Ibid.

49 John Richardson, Analysing Newspapers: An Approach from Critical Discourse Analysis (Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 94.

50 Bednarek and Caple, “‘Value Added.’”

51 Ibid.

52 Ibid.

53 Ibid.

54 Ibid., 104

55 Ibid.

56 Christien, “The Representation of Youth in the Islamic State's Propaganda Magazine Dabiq”; Priyanka Motaparthy, “Maybe We Live and Maybe We Die’: Recruitment and Use of Children by Armed Groups in Syria,” Human Rights Watch (2014); Pinheiro, “The Role of Child Soldiers in a Multigenerational Movement,” 11–13; Noman Benotman and Nikita Malik, “The Children of Islamic State,” The Quilliam Foundation (2016), pp. 1-100; Cathy Otten, “Yazidis Tell How Fearful Isis Kept Them on Move," The Independent, 10 April 2015, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/yazidis-tell-how-fearful-isis-kept-them-on-move-10169024.html (accessed January 2017); Charlie Winter, “Women of the Islamic State: A Manifesto on Women by the Al-Khansaa Brigade,” Quilliam Report (2015), 1–41.

57 Francesca Capone, “‘Worse’ than Child Soldiers? A Critical Analysis of Foreign Children in the Ranks of ISIL,” International Criminal Law Review 17 (2017), 161–185.

58 Christien, “The Representation of Youth in the Islamic State's Propaganda Magazine Dabiq.”.