Abstract

Concept review on right-wing extremism (RWE) holds that authoritarianism, nationalism and anti-democracy are the values that most strongly correlate. Evidence suggests these views are prevalent among military veterans. In this paper we test the hypothesis that individuals that are subjected to martialization are more likely to hold RWE values than other individuals. Using the General Social Survey, which permits the operationalization of authoritarianism, nationalism and anti-democracy into 12 dependent variables, we find that individuals with high levels of exposure to martialization show higher probability of preferring a more extreme stance for every single dependent variable modeled for every year included in the analysis. The result suggests that counter-extremism policy must not ignore the overwhelming impact of military experience where “hearts and minds” are shaped.

Currently, there is much interest in right-wing extremism (RWE), particularly its direct relationship with violent and terrorist outcomes.Footnote1 Incidence of RWE and Right-Wing Extremist Violence (RWV) has been on the rise across much of the Anglosphere inclusive of the Asia Pacific Region (APAC) in the past two decades.Footnote2 Australia’s long RWE history dates back to the 1920s when the out-group that needed to be defeated were Communists. It has adapted with successive waves against Chinese, Jews, homosexuals, nonwhite immigrants and Muslims.Footnote3 Recently, the 2019 terrorist attack in Christchurch by Australian Brenton Tarrant, now a landmark in RWE and RWV within APAC,Footnote4 has shifted counter-terrorism focus to “well-established and persistent” RWE and groups historically formed in consort with the “global RWE community.” Footnote5

There is ample evidence that the link between military experience both prior to and subsequent to radicalization requires ongoing study.Footnote6 In Canada and Germany elite military units have been disbanded over findings that some members espouse RWE views.Footnote7 In the United States, veterans and active-duty military personnel have been found to participate in RWE and RWVFootnote8 and some RWE groups have even been created by people with a military background.Footnote9 In particular, the connection between martialization, defined as nation framing through soldier indoctrinationFootnote10 and RWE, composed of authoritarianism, nationalism and anti-democratic sentimentFootnote11 has been problematized,Footnote12 with the existing literature tantalizingly concerning this link,Footnote13 but yet to produce clear evidence of how military experience inclusive of nation framing (martialization) is directly associated with pro RWE values.

This paper has two goals. First, it seeks to understand if martialization is a contributor to RWE beyond the existing and already established relationship between individual members of the military and RWE groups. It depends on Carter,Footnote14 who comprehensively synthesizes the research of competing RWE definitions and reconceptualises it into three necessary and sufficient core values: authoritarianism, nationalism and anti-democratic sentiment. These are then observed in social attitudes measures by the General Social Survey (GSS) and applied to military experience. We depend on the argument that there is a universality to dimensions of social attitude across the Anglo-American experience so that the GSS data will predict a distinction between martialized and non-martialized cohorts that will be found where political values and military experience is broadly aligned. Our findings indicate that increases in martialization predict increases in authoritarianism, nationalism and anti-democratic sentiment and that therefore martialization appears to be a strong contributor to the emergence of RWE. The implication is that public policy aimed to curb RWE and RWE violence may be deficient where mitigation efforts do not directly or indirectly take account of and counter this adverse effect of martialization.

Right-Wing Extremism

RWE has been investigated in terms of its core features,Footnote15 narrative forms,Footnote16 supportive environment and constituent dimensions in interaction.Footnote17 There is a myriad of competing definitions both within and outside of academia that emphasizes the equivocal nature of the concept. However, the many interrelated or interdependent properties comprising RWE may be refined down.

CarterFootnote18 provides a parsimonious reconceptualization derived deductively from a comprehensive canvasing of the academic literature. As she observes from her synopsis of the research, there is remarkable agreement among analysts regarding what defines RWE.Footnote19 In other words, while end-results may defer, the basic elements that constitute the basis of most definitions are remarkably similar. According to her minimal conceptualization, RWE is an ideology that includes “authoritarianism, anti-democracy and exclusionary and/or holistic nationalism.”Footnote20

Drawing on this minimal definition and consistent with its dimensions or values, we tease out expected social measures and then review their connection with martialization and the logical pathway from each to RWE.

Authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is widely understood as a characteristic of RWE.Footnote21 As a dimension of strong state, authoritarianism needs further clarification, as it would appear to split the right wing from the current extreme right wing. For most RWEs, there is a strong value placed on law and order campaigns that seek a strict or firm “zero tolerance” enforcement of order and crime on the street and the harsh penalization of offenders.Footnote22

In much current RWE, there is a socio-cultural authoritarianism that embraces an anti-elite populism or anti-establishment critique or rhetoric. There is on certain issues a split from support for the state.Footnote23 For instance, where the state seeks to use coercion against libertarian populist values, RWEs will see the state as “an enemy of the people.”

There is a strong connection between the ideological support for a strong state, defined as supporting law and order and militarismFootnote24 and the dimensions of martialization. This is also understood by how right-wing parties view the civil state, particularly the judiciary, mainstream media or press, the NGO sector and welfare and civic infrastructure. Right-wing extremism is a “distinct party family”Footnote25 that involves policies on this common ideological agenda.

Specifically, then, RWEs will wish to see governments doing more to address perceived crime rates (with more police and capital punishment), support rural issues (through link with right-wing populism,Footnote26 support the military and armaments and defence and relaxed carry laws, and do less to provide resources and services to ameliorate urban infrastructure and poverty, particularly from the federal government.

Nationalism

Nationalism, racism and xenophobia are intertwined in that nationalism is conceived by RWE in terms of ethnocentrism and the “conversion, expulsion or worse of the ‘other’.”Footnote27 It is connected to ethnonationalism or Orientalism and an aversion to ethnopluralism or multiculturalism and, in the extreme, to the biological or genetic superiorities of a Western, Anglo or European ethno-body politic and post-colonial standpoint.Footnote28 As noted by Minkenberg, it is a “radicalis[ation] of inclusionary and exclusionary criteria of belonging,” “a romantic and populist ultra-nationalism hostile to liberal, pluralistic democracy.” Footnote29 RWEs seek in-group inclusions and out-group exclusions based on whiteness, which is inclusive of heterophobia or intolerance of those who do not share similar norms, as well as on the fear of ethnic, religious and cultural others.

Evidence that people embrace nationalist or ultranationalist views will be found in their opinions regarding visible minorities and religious freedoms and views of gender and sexual orientation.

Anti-Democracy

Further interconnections are found in the last factor, anti-democracy (inclusive of counter-egalitarianism). Right-wing political ideology is pithily defined by BobbioFootnote30 as counter-egalitarian, or as the seeking to preserve social inequality as inevitable, natural and desirable. Since the 1980s in many western countries disparity between the very top and other quintiles of income earners is on the riseFootnote31 and economic and social mobility has stagnated.Footnote32 Paradoxically, the rightward shift from the center of mainstream politics in many of the same countries follows the discursive attribution of economic and social opportunity in this process of distributive disenfranchisement.Footnote33

It has been proposed that belief in inequality aligns with the cultural indicators of disaffection to push divergence from inclusive politics (frustrated chances produce an explanatory narrative of values and means adaptationsFootnote34). As summarized by Carter, all right-wing parties “reject or oppose some or all of the values of democracy (pluralism, equality, civil and political freedoms), and some also object to the procedures and institutions of the democratic state.”Footnote35

It is the justification of worldview or ideology to opportunity within in-group or out-group identification and association that is key to understanding the outset of right-wing extremism (RWE). Much work on political extremism has centered on the relation between populism, ignorance, tribalism (or nationalism), including racialized and sexualized identityFootnote36 and violence.Footnote37 HanFootnote38 found that the rise of radical right-wing parties (RRPs) “makes right-wing MPs adopt more restrictive positions regarding multiculturalism.”Footnote39

RWE opinion can therefore be ascertained with respect to a person’s views on social inequality and in their support for the institutions of liberal democracy, including the judiciary, the free press, and government, inclusive of their capacity or right to instill equal rights.

Martialization and RWE Values

Martialization is defined as soldier training and military enculturation.Footnote40 The framing of the nation and its patriots is produced through indoctrinization in soldier training.Footnote41 Becoming a soldier is a formative experience that involves the inculcation of skills, values or ideological dispositions, including adopting the political attitudes of role models.Footnote42 Martialization supports longstanding relations, networks and attitudes cemented in common, and sometimes traumatic, experience.Footnote43 Military training and combat experience work on preexisting attitudes so that pre-service attitudes will be a predicator of post-service attitudes.Footnote44 Given institutional and occupational drivers, it is an unsurprising hypothesis that military training and experience is associated with developments of personality traits, including persistent and robust measures of lowered levels of agreeableness, which is also associated with interpersonal conflict and aggression, traits associated with effective or beneficial military service but contrary to civic institutional values.Footnote45 Recruits in the military’s elite and regular services are socialized into forming or maintaining political attitudes consistent with occupational, institutional and cultural and political contexts.Footnote46

The nature of the association between military experience and political attitudes, choices or preferences has been subjected to longstandingFootnote47 and ongoing research.Footnote48 Each of the values (authoritarianism, nationalism and anti-democratic) connected to RWE have been examined.

While military service is only a weak predictor of support for military intervention, veterans have been found to be more in favor of a stronger military taking up a relatively greater budget portion.Footnote49

Authoritarianism

Research from the 1970s found little or no difference in political values and not that it instills an authoritarian political orientation.Footnote50 Jenning and MarkusFootnote51 found effects that they were “not statistically large” and that were mostly “vanquished” with controls. Indeed, they found in a comparison of veterans and non-veterans that political cynicism or distrust of government was higher in non-veterans. As they note, if there were strong results, this would be “cause for concern.” However, SchreiberFootnote52 found veterans to “place a high value on order and to be upset about young people breaking the law when protesting…. Veterans of the World War II era were significantly more likely than nonveterans to approve of the government forbidding demonstrations” and also “to say that they would be upset if young people broke the law while protesting. On the other hand, veterans were more tolerant of communists and atheists.”Footnote53

These studies measured a cohort that included many who had been conscripted into service, whereas the more recent veteran cohorts are largely measuring a self-selected or all-volunteer service. Recent studies of all-volunteer veterans indicate that non-elite veterans support a more conservative domestic policy and are more hawkish on foreign policy.Footnote54

Nationalism

At the level of group interactions, there is also research that links military experience with some expressions of nationalism and particularly ethno- or ultranationalism. On one hand, the recruit experience and military service is a melting pot that brings various ethnicities and religiosities into propinquity.Footnote55 Intensive training and combat experience together with close working and living arrangements may produce shared immediate strains and goals, increase familiarity and sameness across out-groups and predict a lessening of bias or prejudice against out-group ethnicities.Footnote56 Accordingly, the all-volunteer pool of recruits will be indoctrinated to point hostilities away from its own strong ethnic and religious subgroups.

On the other hand, the military and militarism places the group within civil society in a somewhat oppositional institutional power relation.Footnote57 Recruits and veterans seek to identity safe havens between the simplified differences between liberal and conservative values. The longstanding dominance of social conservative values also arises in the conflict resolution setting of transactional militarism.

Veteran experience is associated with a greater appetite for economic nationalism or protectionism or stronger tariffs.Footnote58 A 2019 survey of military personnel by the Military Times found that 22 percent “had seen signs of white nationalism or racist ideology within the armed forces.”Footnote59 A U.S. survey of 17,080 soldiers found that 3.5 percent had been recruit contacted “and that 7.1 percent said they knew another soldier who they believed to be part of an extremist organization.”Footnote60

Anti-Democratic

Veteran opinion has been found to be relatively authoritarian and nationalist, but the relation between veteran opinion and anti-democratic values may be somewhat complicated. Past research has found that veterans are less likely to favor more spending on foreign aid or to express internationalist opinions supporting the U.S. being active in world affairs and belonging to the U.N.Footnote61 Elites who have experienced deployment express an opposite opinion, favoring the use of these foreign policy instruments.Footnote62 Support for the hypothesis that martialization inclusive of “elite-transformation” will have significant socializing impact is far from universal.Footnote63 Recent research has found recruits and veterans are more likely to want to use force to “prevent genocide” and “protect allies.”Footnote64 Prior military service (but not combat experience) has been positively correlated with the initiation of “militarized disputes.”Footnote65 Based on the Survey of American Veterans data, Chatagnier and Klingler found that military veterans are more economically and socially conservative than when they entered the service, although not more hawkish on foreign policy and not more ideologically libertarian.Footnote66 This suggests that whereas both groups should continue to be expected to express lower relative support for equalization measures or strategies that these institutions are often actively involved in, current research has not consistently supported this dimension of the anti-democratic association.

Distrust of the judiciary, media and federal governments is an indication of the anti-establishment populism that has been documented among military veterans and is an associated characteristic of RWE.Footnote67 Two recent studies have indicated mixed findings. One found that combat exposure, particularly to severe combat trauma, is associated with reduced political efficacy or civic engagement and trust.Footnote68 Another study found no difference between veterans and non-veterans with regard to scores in support of legal legitimacy.Footnote69

Conceptualizing the Associations

Broad, multi-level understanding of all necessary and sufficient factors leading to RWE violence is essential for deterrence efficacy in anti-extremism policy.Footnote70 Of interest, given the prima facie relation between political values of nationalism and authoritarianism and the militant disposition, or martialization, is the significant sub-group of right-wing extremists comprised of military veterans.Footnote71 As has been well-established, military indoctrination and thick experience with military values (martialization) is a form of long-standing within-group conditioning intended to maximize soldier compliance with leadership objectives.Footnote72 As is also well-known, the values that are most connected to militarism include authoritarianism, nationalism and anti-democracy (and anti-egalitarian) values.Footnote73 RWE overlaps with militarism in principal socio-political correlates including cultural conservatism, nostalgic nationalism, religiosity and xenophobic patriotism.Footnote74

In the broadest sense, if the characteristics of RWE are hypothesized to be similar to but independent of martialization, an argument supporting the causal relation needs a logical form as well as supporting evidence. If authoritarianism, nationalism and anti-democratic values are elements of both concepts, the relative intensity, duration and currency of martializationFootnote75 should be expected to impact on the expression of RWE indicators among veterans. This may be considered in terms of the elements and processes of radicalization.Footnote76

First, there is a cognitive framing that is more or less accomplished in recruitment to military association. Necessary to martialization is the cultivation of in-group loyalty in a cognitive bias that settles the ethnic and national distinction across the enemy/friend binary. Group identification and loyalty is distinguished through norms and values across membership trials. A worldview or cognitive frame is fostered or set in intensive group involvement, particularly under duress. Martialization sets up strong group biases and consequences for deviation from rule compliance.Footnote77

Second, the content norms of martialization and the standpoint of review of civil–military relations are logically responsive to wider trends in the social and political culture, particularly how enemies of the state or the people are framed in popular media. The values of patriotism, nationalism and religiosity are already associated with military and conservative political opinion.Footnote78 Changes in cultural phenomenology or economic and political environment will be reflected in rising and declining factors or strains of RWE.Footnote79 Routine exposures to some ethnic diversity during combat training and combat in light of indoctrination objectives and practices may shift or pull reviews of targets and identities on the friend/enemy binary. As has been recently demonstrated experimentally, where discussion takes place in a context of preexistent predilection deliberation over political and moral issues is not an antidote and may shift opinion in a process of “ideological amplification” to more extremist views.Footnote80 For instance, there have been shifts from the targeting of Jewish and Asian people toward a greater concentration of anti-establishment and anti-intellectual orientation in new right groups.Footnote81 With RWE, an emergent crisis of legitimacy between an challenger group and government authority is expressed in the “dehumanization of anyone associated with the regime.”Footnote82

With respect to intensity and duration, martialization will be a worldview conditioner that may not support each RWE factor equally. In martialization, de-humanisation of the enemy combatant or noncombatant “permits” the use of overwhelming and sometimes indiscriminate deadly violence. It has been found that exposure to combat and participating in atrocities including harming civilians will increase misconduct stress.Footnote83 Exposure to unruly transactive combat where neither the ideological other nor the mortal threat combatant is the target produces both a framing and “community crisis.”Footnote84 In the event, actors can “disengage morally and commit atrocities without remorse.”Footnote85 The network of associations of military veterans produce a context in which moral attributions are more or less socio-functional; following immoral command instructions is the least contextually dysfunctional alternative, but this must be reconciled to the shifting sands of civil–military relations (as above), where popular opinion judges military conduct norms.Footnote86 Military and RWE violence both draw from a “process of delegitimization”Footnote87 and positively associate in-group superiority and endorsement of right-wing motivated violence. Veterans can be recruited to RWE by exploiting this association.Footnote88

Lastly, it is well-understood that right-wing nationalist populism references the betrayal of working and middle-class workers and citizens by cosmopolitan elites.Footnote89 Populist extremism is a reaction to the perceived betrayal of group interests by cultural authorities or political leaders. It is also well-understood that veterans’ moral injuryFootnote90 tends to reference betrayal by commanders in the field and from political elites. To close the circle, strategic elective belligerence in a war of aggression is expected to produce a proliferation of betrayal grievance.Footnote91 Radicalization will encompass multiple complex causal factors and pathways. It is known that necessary conditions include a worldview reset which encompasses militarism in in-group solidarity, elite betrayal and victim solidarity.Footnote92 A reset is required in response to moral injury after ontological expectations of soldiering are violated by world-real experience. The reset leads to the adoption of collective action frames that are efficient in maintaining key dimensions of the militant disposition.Footnote93

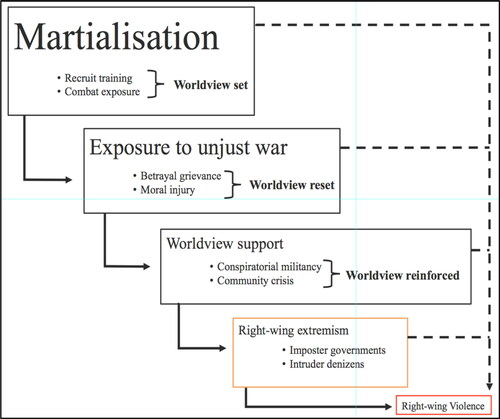

Incidence of RWE can be understood as requiring both conditioning and direction. Research by Jensen et al.Footnote94 found pathways across individual level psychological, social identity, group-based recruitment theory, social movement theory and cost benefit models and conclude that “only two conditions – shifts in individual cognitive frames and community crises – are necessary conditions for violent outcomes.”Footnote95 Conditioning is provided by community crisis and cognitive framing or dynamic context of intensive group level enculturation. Direction is given through the specific value preferencing. It is reasonable that martialization inclusive of training and military experience entails community crisis and a process of cognitive (re)framing. A logical pathway to RWE may be hypothesized in terms of martial socialization under dynamic stresses of differing intensity or currency in contextual pressures . Martialization gives direction to shared experience, first, in the initial clarification of in-group and out-group values and identities, and second, in the review of the civilian institutional arrangements in light of moral injury betrayal. Veterans differentially experience cognitive frame reset and community crisis.

Research Design, Data, Variables and Methods

The overarching hypothesis of this study is that individuals that are subjected to martialization are more likely to engage in RWE than other individuals. Our goal is to establish a relationship between martialization and attitudes that are compatible with RWE. We also want to understand how this process plays out in Australia. Unfortunately, however, there currently is no data collected in Australia about social attitudes and history of military service of individual respondents. Luckily, the General Social Survey (GSS), collected by the NORC at the University of Chicago has been systematically collecting this data using American subjects since 1972. Throughout its history, Australia has adopted its military practices and political institutions from Anglo-American precedents, and is ideologically attachedFootnote96 and strategically linked with United States in ANZUS,Footnote97 through which it has “been conditioned by its self-perception as the Anglo-American outpost of the South.”Footnote98 Especially since the joint U.S.-Australia declaration in 1996 known as the “Sydney Statement,” the close military relationship between Australia and the United States takes form of a large number of joint exercises, regular joint training, operational and tactical cooperation and interoperability, and even exchange postings for its military personnel.Footnote99 Consequently, to test RWE’s dependence on martialization we rely on data from the GSS. While this choice prevents us from discussing Australian attitudinal traits toward RWE, we believe that the relationships we are able to describe are generalizable and applicable to the Australian case as well as throughout the Anglosphere and, more broadly, Western countries.

The GSS has been tracking data on social attitudes since 1972. We collect all relevant survey responses between 1972 and 2018 into a single dataset that we use for all data analyses. Within the GSS, we choose the questions that best speak to each one of the three defining properties of RWE identified by Carter,Footnote100 that is, authoritarianism, nationalism and anti-democracy. More in detail, we operationalize each one of these three defining properties by identifying specific attitudinal questions within the GSS that fall clearly within each domain. To gauge at authoritarian sentiment, we focus on four distinct attitudinal dimensions: (1) attitude toward law and order, (2) attitude toward the military, (3) attitude toward capital punishment and (4) attitude toward gun permits. When it comes to nationalist sentiment, we identify three distinct attitudinal dimensions: (1) attitude toward foreign aid, (2) attitude toward programs targeting the improvement of the conditions of black individuals and (3) attitude toward the government providing special treatment to black individuals. We also identify five distinct attitudinal dimensions related to anti-democracy: (1) attitude toward the welfare state, (2) attitude toward income inequality, (3) confidence in the federal government, (4) confidence in the press and (5) attitude toward healthcare. shows the specific questions utilized under each domain and summarizes the way we coded each set of answers. While we do not want to claim in any way that these questions exhaustively operationalize Carter’s three domains, we do believe that a collective look at the questions we selected can provide very good insight on how an individual is positioned within all three domains.

Table 1. GSS questions, variables and coding.

We use the variables described in to compute 12 dependent variables that relate to each of the three domains devised by Carter that we then use to estimate 12 different regression models. The dependent variables Law & Order, Military, Capital Punishment and Gun Permits allow us to understand authoritarian sentiment, the dependent variables Foreign Aid, Conditions of Blacks and Special Treatment of Blacks give us insight on nationalist sentiment, and the dependent variables Welfare, Inequality, Confidence in Federal Government, Confidence in Press and Healthcare allow us to look at anti-democratic sentiment. As it is clear in , Capital Punishment and Gun Laws are dichotomous variables, while all other variables are ordinal.

The GSS also includes a question on veteran status and years of military service that we use to construct our main independent variable of interest, Degree of Martialization. This is an ordinal variable coded 0 for respondents who have never served in the military, 1 for respondents who have served in the military for less than 2 years, 2 for individuals with between 1 and 4 years of military service, and 3 for individuals with more than 4 years of military service. As the name of the variable suggests, it measures how much an individual has been exposed to a process of martialization.

We also use a number of other questions included in the GSS survey to compute several control variables that we utilize throughout our analysis. Age is a continuous variable containing the age of the respondent, Female is a dichotomous variable coded 0 for male respondents and 1 otherwise, and White is a dichotomous variable code 0 for nonwhite respondents and 1 for white respondents. Education Level and Income Group are ordinal variables capturing respectively the highest year of schooling completed by the respondent and the respondent’s income category. In conclusion, Level of Religious Engagement is an ordinal variable capturing how often the respondent attends a religious service. We also compute year-specific variables coded 1 for all observations belonging to a specific year and 0 otherwise.

We run 12 different regression models using each one of our 12 dependent variables and including in the right side of the equation our main independent variable of interest Degree of Martialization, as well as all of our other covariates. All models are ordered logistic regressions, except for the models using Capital Punishment and Gun Laws as dependent variables, that are run as logistic regressions. We then transform the regression coefficients into predicted probabilitiesFootnote101 for each year included in the analysis, assuming a white male respondent with income and religious engagement levels set to the respective median values and all other covariates set to their mean.

Results and Analysis

We run 12 different regression models. The first four models (Model 1 - Law & Order, Model 2 – Military, Model 3 – Capital Punishment and Model 4 – Gun Permits) fall within Carter’s authoritarian domain. We also run three models within the nationalist domain (Model 5 – Foreign Aid, Model 6 – Conditions of Blacks and Model 7 – Special Treatment of Blacks). Finally, we run five additional models within the anti-democracy domain (Model 8 – Welfare, Model 9 – Inequality, Model 10 – Confidence in Federal Government, Model 11 – Confidence in the Press and Model 12 – Healthcare). All results are gathered in .

Table 2. Results of regression models.

While we are not trying to argue here that the 12 dependent variables we use to run the 12 models gathered in fully explain each one of Carter’s three dimensions and we recognize that our operationalization presents gaps and due to unavailability of data is therefore only partial, we do think that the 12 models we are able to run give us a fairly good idea, albeit partial and incomplete, of the overall role that martialization plays within the three domains. In order to better interpret the results of the regression models, shows the increase in probability that an individual takes the most extreme stance possible on the various issues modeled, comparing the probability associated with someone with no military service—that is, someone not exposed to martialization—to the probability associated with someone with over 4 years of military service. Individuals with high levels of exposure to martialization show higher probability of preferring a more extreme stance for every single dependent variable modeled for every year included in the analysis. To illustrate, shows for instance that in 2010 an individual with over 4 years of exposure to martialization was 10% more likely than someone with no military service at all to think that blacks should not receive any favorable treatment from government.

Table 3. Maximum increase in predicted probability of displaying views compatible with authoritarian, nationalist, and anti-democracy sentiment due to degree of martialisation.

The Authoritarian Domain

We ran four distinct models within the authoritarian domain. The results are gathered in . All four models show that higher levels of martialization are associated with a higher likelihood of individuals expressing extreme positions in all four dependent variables. In other words, the more time an individual spends serving in the military the more likely he/she is to think that government expenditure to halt the rising crime rate and on the military, armaments and defence is too low (Model 1 - Law & Order and Model 2 - Military). The results also show that the longer an individual serves in the military, the more likely he/she is to be in favor of capital punishment and to oppose legislation restricting the ability to purchase firearms (Model 3 – Capital Punishment and Model 4 – Gun Permits).

The probability transformation of the results of Models 1, 2, 3 and 4 confirm that martialization has a significant impact on how an individual views these four issues in the authoritarian domain. For instance, keeping everything else constant, a white male in 1984 with high level of martialization—that is, with more than 4 years of military service—is 4% more likely to think that expenditure in law and order is too low, 10% more likely to think that expenditure on the military is too low, 6% more likely to support the death penalty and 7% more likely to oppose gun permits than a white male with no military service.

Overall, the results appear to support the hypothesis that one of the outcomes of martialization is an individual more open toward positions that are generally believed to be associated with authoritarian sentiment. This is true when it comes to support for law and order and militarization, as Models 1, 2 and 4 show, and also when it comes to supporting the harsh penalization of offenders, as Model 3 shows.

The Nationalist Domain

also gathers the results of three models that relate to the nationalist domain. Model 5 (Foreign Aid) shows that the higher the degree of martialization, the more likely it is that an individual believes that the current expenditure on foreign aid is too high. Model 6 (Conditions of Blacks) and Model 7 (Special Treatment of Blacks) deal instead with a racial issue. Both models predict that higher levels of martialization result in individuals who think that the government is doing too much to try to improve the conditions of blacks (Model 6) and that the government should not allow any kind of special treatment benefiting black individuals (Model 7).

shows the probability transformations based on the results of Models 5, 6 and 7. According to the results, in comparison with someone with no military service, a white male in 2018 with high level of martialization was 10% more likely to think that the government was spending too much on foreign aid, 3% more likely to think that it was doing too much to improve the conditions of blacks, and 9% more likely to think that the government should not provide any special treatment to blacks.

Our results seem to support the hypothesis that martialization increases nationalist sentiment as a process of in-group inclusion and out-group exclusion based on whiteness.

The Anti-Democratic Domain

We ran 5 different models within the anti-democratic domain. also gathers the results of these models. Once again, martialization emerges as a significant predictor of all the dependent variables we use to assess anti-democratic sentiment. The results show that the more time an individual spends serving in the military the more likely he/she is to think that the government spends too much in welfare (Model 8 – Welfare), that the government should not address income inequalities (Model 9 – Inequality) and that the government should not take care of the sick (Model 12 – Healthcare). In addition, the results also show that the longer an individual is exposed to martialization, the less confidence he/she has toward the federal government (Model 10 – Confidence in Federal Government) and toward the press (Model 11 – Confidence in the Press).

show the probability transformations based on the results of the models. According to these results, a white male in 1994 who was exposed to martialization for over 4 years was 5% more likely to think that the government was spending too much on welfare, 6% more likely to think that the government should not address income inequalities and 4% more likely to believe that the government should not take care of the sick than someone with no military service. Similarly, he was also 5% more likely to distrust the federal government and 3% more likely to distrust the press than someone with no exposure to martialization.

Table 4. Causal relationship → The more exposed to martialisation:

Overall, the models run within the anti-democratic domain give a good idea of how martialized individuals end-up viewing some very important democratic values and display anti-egalitarian sentiment.

Implications, Limitations and Further Study

The broad agreement across the three characteristics of RWE found in these results suggests the need for continued mitigation efforts that extend across the multiple levels of engagement (individual, group and institution or societal). Exposure to militarism and martial values is found in among military veterans, but martialization is not limited to veterans, so it may be expected that martialization is also found to be at play in engagement with cultural products including gaming and social media.Footnote102 The interaction of militarism with civil society values over time is also of great relevance, as the nation-state, through its political leadership, identifies military objectives and the constituent character of enemy forces.Footnote103 As we report here, it may be that military enculturation has been successful in deterring veterans from stronger anti-Muslim, anti-atheist, anti-homosexual and anti-communist sentiment. Whilst we were keen to divide the time frame according to “epochs” of confrontation, namely Cold War (1945–1989), interregnum (1990–2001), war on terrorism (2001–2018) on the obvious hypothesis that veterans will project the nationalist vilifications by political leaders (communists, gays, atheists, Muslims), the continuity of veterans across these divisions made this impossible with this data.

It is observed in much current research that group interaction dynamics play a large role in radicalization. This research may be understood as supporting that finding in that martialization is somewhat synonymous with group interaction dynamics. It is also being well-established that self-selection by persons vulnerable to extremist views into alternative right-wing media chat and web-based groupsFootnote104 is connected to developing more insular and insulated opinion.Footnote105 The interaction of military veterans, and particularly veterans who experience moral injury or betrayal (or after-martialization sentiment), with RWE groups is an obvious indicator of exceptional or acute proneness to RWV and terrorism.

With regard to limitations, most of the data is drawn after the end of conscription, but conscripted soldier opinion and voluntary soldier opinion is not distinguished in the collection. Although this is an important characteristic of martialization, we were unable to differentiate on this. In addition, the survey is from U.S. citizens. The extent of comparative differences at play comparatively needs to be studied. However, given that the U.S. leads decision-making on war-fighting across Nato and aligned countries (ANZUS), leads a large number of training activities and exercises, and even hosts a myriad of Australian military personnel in exchange posts, it is reasonable to suggest that the phenomenon will be replicated in Australia.

Conclusion

We began this research cognizant that the answer to the problem of the antecedents of RWE ought to account for both values conditioning and direction. Following Jensen et al.Footnote106 and Smith et al.,Footnote107 necessary conditioning includes a cognitive frame within the dynamic group in community crisis.Footnote108 Our positive findings suggest martialization captures the processes expected to be in play and therefore that policy on mitigation will be missing the mark where martialization is not considered or is considered only out of context of the setting up of group objects and objectives.

This merges into the consideration of values direction. The present research has taken up the question from the hypothesis that the consonance between martialization and RWE sentiments ought to be evident in the broadest surveys of opinion on political and social values and that if proven, ought to inform policy choices regarding prevention of RWV. The results support the hypothesis. In order to effectively mitigate right-wing extremist violence, it is necessary to profile multiple or longer radicalization pathways. Where governmental policy is indifferent to accumulated structural causes (that is, causation prediction that pays attention to the social, economic, and political situatedness of the individual), it is unlikely to produce complete results.

There may be a wicked problem here. Governments and non-government organizations, including the Institute of Strategic Dialogue (ISD), the International Center for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT), the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) and the Center for Prevention of Radicalization Leading to Violence (CPRLV), have developed resources and counter and deradicalization strategies.Footnote109 However, much of the research on right-wing extremist violence reviews the outcomes of conditioning in the behavioral, network or relationship antecedents and concentrates on diversion, disruption, social cohesion,Footnote110 plural policing and education or livelihood initiatives.Footnote111 If extremism is political advocacy by unconventional means and mitigation focuses on values that are also the unofficial constructs of militarism, there is a contradiction of purpose that produces the conditions of betrayal and moral injury. The effect is also a de-politicization of the societal or policy choices or context propensities of disaffected military personnel.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Michael A. Jensen, Anita Atwell Seate, and Patrick A, James, “Radicalization to Violence: A Pathway Approach to Studying Extremism,” Terrorism and Political Violence 32, no. 5 (2020): 1067–90; Daniel Koehler, “Right-Wing Extremism and Terrorism in Europe,” Prism 6, no. 2 (2016): 84–105.

2 There is evidence of the rise of RWE is generally supported for the United States, Canada and Australia (Seth J. Jones, “The Rise of Far-Right Extremism in the United States” (Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 7, 2018), 1–9, https://www.csis.org/analysis/rise-far-right-extremism-united-states; Priya Chacko and Kanishka Jayasuriya, “Asia’s Conservative Moment: Understanding the Rise of the Right,” Journal of Contemporary Asia 48, no. 4 (2018): 529–40; David C. Hofmann, Brynn Trofimuk, Shayna Perry, and Caitlin Hyslop-Margison, “An Exploration of Right-Wing Extremist Incidents in Atlantic Canada,” Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict (2021): 1–23), but there is mixed opinion concerning Europe as a whole (Seth G. Jones, Catrina Doxsee, and Nicholas Harrington, The Right-wing Terrorism Threat in Europe (Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), March 24, 2020),1; Syed Shehzad Ali, “Far-Right Extremism in Europe,” Journal of European Studies (JES) 37, no. 1 (2021): 119–39; Jacob Aasland Ravndal, “Right-wing Terrorism and Violence in Western Europe: Introducing the RTV Dataset,” Perspectives on Terrorism 10, no. 3 (2016): 2–15).

3 Kristy Campion, “A ‘Lunatic Fringe’? The Persistence of Right Wing Extremism in Australia,” Perspectives on Terrorism 13, no. 2 (2019): 2–20.

4 Jade Hutchinson, “Far-Right Terrorism,” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 11, no. 6 (2019): 19–28.

5 In 2019, former ASIO boss Duncan Lewis said right-wing extremism had increased in Australia (“Outgoing ASIO Boss Duncan Lewis Says Right-wing Extremism Has Increased in Australia,” SBS News, October 17, 2019, https://www.sbs.com.au/news/asio-warns-right-wing-extremists-increasingly-cohesive-and-organised). In September 2020, ASIO Deputy-Director Heather Cook said threats from right wing violence accounted for 30 - 40% of ASIOs priority counter-terrorism caseload (Maani Truu, “Threats from Far-Right Extremists Have Skyrocketed in Australia,” SBS News, September 22, 2020, https://www.sbs.com.au/news/threats-from-far-right-extremists-have-skyrocketed-in-australia-with-asio-comparing-tactics-to-is). See also Campion, “A “Lunatic Fringe”? The Persistence of Right Wing Extremism in Australia.”

6 Daniel Koehler, A Threat from Within?: Exploring the Link between the Extreme Right and the Military (International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 2019).

7 Ibid.

8 A. C. Thompson, Ali Winston, Jake Hanrahan, “Ranks of Notorious Hate Group Include Active-Duty Military,” PBS Frontline, May 3, 2018; Christopher Mathias, “Exposed: Military Investigating 4 More Servicemen For Ties To White Nationalist Group,” The Huffington Post, April 27, 2019.

9 Koehler, A Threat from Within?: Exploring the Link between the Extreme Right and the Military.

10 Richard Evans, “Hazing in the Adf: A Culture of Denial?,” Australian Army Journal 10, no. 3 (2013): 113.

11 Elisabeth Carter, “Right-Wing Extremism/Radicalism: Reconstructing the Concept,” Journal of Political Ideologies 23, no. 2 (2018): 157–82.

12 Kevin D. Haggerty and Sandra M. Bucerius, “Radicalization as Martialization: Towards a Better Appreciation for the Progression to Violence,” Terrorism and Political Violence 32, no. 4 (2020): 768–88.

13 Ibid.

14 Carter, “Right-Wing Extremism/Radicalism: Reconstructing the Concept.”

15 Jensen, Atwell Seate, and James, “Radicalization to Violence: A Pathway Approach to Studying Extremism”; Carter, “Right-Wing Extremism/Radicalism: Reconstructing the Concept.”

16 Geoff Dean, Peter Bell, and Zarina Vakhitova, “Right-Wing Extremism in Australia: The Rise of the New Radical Right,” Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism 11, no. 2 (2016): 121–42.

17 Jensen, Atwell Seate, and James, “Radicalization to Violence: A Pathway Approach to Studying Extremism”; M. Kent Jenning and Gregory B. Markus, “The Effect of Military Service on Political Attitudes: A Panel Study,” The American Political Science Review 71, no. 1 (1977): 131–47.

18 Carter, “Right-Wing Extremism/Radicalism: Reconstructing the Concept.”

19 Much RWE research and almost all policy is restricted to a view focused at the level of individual or group level behavioural factors (e.g. Randy Borum, “Radicalization into Violent Extremism: a Review of Social Science Theories,” Journal of Strategic Security 4, no. 4 (2011): 7–36; James Khalil, “The Three Pathways (3P) Model of Violent Extremism,” The RUSI Journal 162, no. 4 (2017): 40–48), but knowledge of incidence of extremist violence requires capture of meso- and macro-level variables (Gary LaFree, Michael A. Jensen, Patrick A. James, and Aaron Safer‐Lichtenstein, “Correlates of Violent Political Extremism in the United States,” Criminology 56, no. 2 (2018): 233–68). Research must also heed the dynamic context in which individual behaviour adaptations are responsive to the intensity, duration and currency of societal shifts (Jenning and Markus, “The effect of military service on political attitudes: A panel study”; Ronald R. Krebs, “A school for the nation? How military service does not build nations, and how it might,” International Security 28, no. 4 (2004): 85–124; Laura G. E. Smith, Leda Blackwood, and Emma F. Thomas, “The Need to Refocus on the Group as the Site of Radicalization,” Perspectives on Psychological Science 15, no. 2 (2019): 327–52). With regard to pathway research, it is found that RWE flows into violent outcomes (terrorism) when individual cognitive frames shift in concert with community crises (Jensen, Atwell Seate, and James, “Radicalization to Violence: A Pathway Approach to Studying Extremism”).

20 Carter, “Right-Wing Extremism/Radicalism: Reconstructing the Concept.”

21 Cas Mudde, “Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe Redux,” Political Studies Review 7, no. 3 (2009): 330–37; Carter, “Right-Wing Extremism/Radicalism: Reconstructing the Concept.”

22 Koehler, A Threat from Within?: Exploring the Link between the Extreme Right and the Military.

23 Manuela Caiani and Donatella Della Porta, “The Elitist Populism of the Extreme Right: A Frame Analysis of Extreme Right-Wing Discourses in Italy and Germany,” Acta Politica 46, no. 2 (2011): 180–202.

24 Mudde, “Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe Redux.”

25 Carter, “Right-Wing Extremism/Radicalism: Reconstructing the Concept.”

26 Natalia Mamonova and Jaume Franquesa, “Populism, Neoliberalism and Agrarian Movements in Europe. Understanding Rural Support for Right-Wing Politics and Looking for Progressive Solutions,” Sociologia Ruralis 60, no. 4 (2020): 710–31; Chip Berlet and Spencer Sunshine, “Rural Rage: The Roots of Right-Wing Populism in the United States,” The Journal of Peasant Studies 46, no. 3 (2019): 480–513.

27 Roger Eatwell, “The Nature of the Right, 2: The Right as a Variety of ‘Styles of Thought’,” The Nature of the Right: American and European Politics and Political Thought Since (1989): 62–76.

28 Michael Minkenberg, “The European Radical Right and Xenophobia in West and East: Trends, Patterns and Challenges,” Right-wing Extremism in Europe: Country Analyses, Counter-strategies and Labor-market Oriented Exit Strategies (2013): 9–33.

29 Ibid., 11.

30 Norberto Bobbio, The Age of Rights, trans. A. Cameron (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1996).

31 Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, “Inequality in the Long Run,” Science 344, no. 6186 (2014): 838–43.

32 Herman G. Van de Werfhorst and Wiemer Salverda, “Consequences of Economic Inequality: Introduction to a Special Issue,” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 30, no. 4 (2012): 377–87.

33 Joseph E. Stiglitz, The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future (WW Norton & Company, 2012).

34 Dean, Bell, and Vakhitova, “Right-Wing Extremism in Australia: The Rise of the New Radical Right”; Caiani and Della Porta, “The Elitist Populism of the Extreme Right: A Frame Analysis of Extreme Right-Wing Discourses in Italy and Germany.”

35 Carter, “Right-Wing Extremism/Radicalism: Reconstructing the Concept.”

36 Philip M. Fernbach, Todd Rogers, Craig R. Fox, and Steven A. Sloman, “Political Extremism Is Supported by an Illusion of Understanding,” Psychological Science 24, no. 6 (2013): 939–46; Albert Breton, Gianluigi Galeotti, Pierre Salmon, and Ronald Wintrobe, Political Extremism and Rationality (Cambridge University Press, 2002); Alain Van Hiel and Ivan Mervielde, “The Measurement of Cognitive Complexity and Its Relationship with Political Extremism,” Political Psychology 24, no. 4 (2003): 781–801; Neil Ferguson and James W. McAuley, “Dedicated to the Cause: Identity Development and Violent Extremism,” European Psychologist, 26 no, 1 (2021): 6–14.

37 Arie W. Kruglanski, Michele J. Gelfand, Jocelyn J. Bélanger, Anna Sheveland, Malkanthi Hetiarachchi, and Rohan Gunaratna, “The Psychology of Radicalization and Deradicalization: How Significance Quest Impacts Violent Extremism,” Political Psychology 35 (2014): 69–93.

38 Kyung Joon Han, “The Impact of Radical Right-Wing Parties on the Positions of Mainstream Parties Regarding Multiculturalism,” West European Politics 38, no. 3 (2015): 557–76.

39 As has been demonstrated experimentally, where political discussion takes place in a context of pre-existent predilection, deliberation over political and moral issues may exacerbate the centrifugal movement in an “ideological amplification” (Schkade, Sunstein, and Hastie, “When Deliberation Produces Extremism,” 228). Abou-Chadi and Krause found that radical right party platforms have migrated into the policy positions of mainstream parties “independent of public opinion as a potential confounder.” (Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Werner Krause. "The causal effect of radical right success on mainstream parties’ policy positions: A regression discontinuity approach." British Journal of Political Science 50, no. 3 (2020): 829–847, at p. 829). It has been seen recently that centrist politics is relatively less popular than radical right and some radical left politics in places including eastern Europe, the UK, the US, Australia and Canada, among other countries.

40 Evans, “Hazing in the Adf: A Culture of Denial?,” 113.

41 Haggerty and Bucerius, “Radicalization as Martialization: Towards a Better Appreciation for the Progression to Violence.”

42 Jason K. Dempsey, Our Army: Soldiers, Politics, and American Civil–Military Relations (Princeton University Press, 2009).

43 Cynthia H. Enloe, Ethnic Soldiers: State Security in Divided Societies (University of Georgia Press, 1980).

44 Jenning and Markus, “The Effect of Military Service on Political Attitudes: A Panel Study.”

45 Susan T. Jackson, Jutta M. Joachim, Nick Robinson, and Andrea Schneiker, “Assessing Meaning Construction on Social Media: A Case of Normalizing Militarism,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (2017), https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep19138.pdf.

46 Krebs, “A School for the Nation? How Military Service Does Not Build Nations, and How It Might.”

47 Edward M. Schreiber, “Enduring Effects of Military Service? Opinion Differences between US Veterans and Nonveterans,” Social Forces 57, no. 3 (1979): 824–39; Jenning and Markus, “The Effect of Military Service on Political Attitudes: A Panel Study.”

48 Tyson Chatagnier and Jonathan Klingler, “Would You Like to Know More? Selection, Socialization, and the Political Attitudes of Military Veterans,” SSRN (November 28, 2016), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2876839; Kaye Usry, “The Political Consequences of Combat: Post-Traumatic Stress and Political Alienation among Vietnam Veterans,” Political Psychology 40, no. 5 (2019): 1001–18; Benjamin G. Bishin and Matthew B. Incantalupo, “From Bullets to Ballots? The Role of Veterans in Contemporary Elections,” (University of California, Riverside, 2008); David Flores, “Politicization Beyond Politics: Narratives and Mechanisms of Iraq War Veterans’ Activism,” Armed Forces & Society 43, no. 1 (2017): 164–82.

49 Chatagnier and Klingler, “Would You Like to Know More? Selection, Socialization, and the Political Attitudes of Military Veterans.”

50 Donald T. Campbell and Thelma H. McCormack, “Military Experience and Attitudes toward Authority,” American Journal of Sociology 62, no. 5 (1957): 482–90; Klaus Roghmann and Wolfgang Sodeur, “The Impact of Military Service on Authoritarian Attitudes: Evidence from West Germany,” American Journal of Sociology 78, no. 2 (1972): 418–33.

51 Jenning and Markus, “The Effect of Military Service on Political Attitudes: A Panel Study.”

52 Schreiber, “Enduring Effects of Military Service? Opinion Differences between US Veterans and Nonveterans.”

53 Ibid., 833

54 Jonathan D. Klingler and J. Tyson Chatagnier, “Are You Doing Your Part? Veterans’ Political Attitudes and Heinlein’s Conception of Citizenship,” Armed Forces & Society 40, no. 4 (2014): 673–95; Bishin and Incantalupo, “From Bullets to Ballots? The Role of Veterans in Contemporary Elections.”

55 Krebs, “A School for the Nation? How Military Service Does Not Build Nations, and How It Might.”

56 George C. Homans, The Human Group (Routledge, 2013).

57 Morris Janowitz, The Professional Soldier: A Social and Political Portrait (Simon and Schuster, 2017).

58 Chatagnier and Klingler, “Would You Like to Know More? Selection, Socialization, and the Political Attitudes of Military Veterans.”

59 Koehler, A Threat from Within?: Exploring the Link between the Extreme Right and the Military.

60 David Sterman, “The Greater Danger: Military-Trained Right-Wing Extremists,” The Atlantic, April 24, 2013, https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/04/the-greater-danger-military-trained-right-wing-extremists/275277/.

61 Schreiber, “Enduring Effects of Military Service? Opinion Differences between US Veterans and Nonveterans.”

62 Chatagnier and Klingler, “Would You Like to Know More? Selection, Socialization, and the Political Attitudes of Military Veterans”; Peter D. Feaver and Christopher Gelpi, Choosing Your Battles: American Civil-Military Relations and the Use of Force (Princeton University Press, 2005); Christopher Gelpi and Peter D. Feaver, “Speak Softly and Carry a Big Stick? Veterans in the Political Elite and the American Use of Force,” American Political Science Review 96, no. 4 (2002): 779–93.

63 Krebs, “A School for the Nation? How Military Service Does Not Build Nations, and How It Might.”

64 Chatagnier and Klingler, “Would You Like to Know More? Selection, Socialization, and the Political Attitudes of Military Veterans.”

65 Michael C. Horowitz and Allan C. Stam, “How Prior Military Experience Influences the Future Militarized Behavior of Leaders,” International Organization 68, no. 3 (2014): 527–59.

66 Chatagnier and Klingler, “Would You Like to Know More? Selection, Socialization, and the Political Attitudes of Military Veterans.”

67 Carter, “Right-Wing Extremism/Radicalism: Reconstructing the Concept.”

68 Usry, “The Political Consequences of Combat: Post-Traumatic Stress and Political Alienation among Vietnam Veterans.”

69 John M. Gallagher and Jose B.Ashford, “Perceptions of Legal Legitimacy among University Students with and without Military Service,” Journal of Veterans Studies 4, no. 2 (2019): 137–52.

70 LaFree, Jensen, James, and Safer-Lichtenstein, “Correlates of Violent Political Extremism in the United States”; Jensen, Atwell Seate, and James, “Radicalization to Violence: A Pathway Approach to Studying Extremism”; Eric B. Elbogen, Sara Fuller, Sally C. Johnson, Stephanie Brooks, Patricia Kinneer, Patrick S. Calhoun, and Jean C. Beckham, “Improving Risk Assessment of Violence among Military Veterans: An Evidence-Based Approach for Clinical Decision-Making,” Clinical Psychology Review 30, no. 6 (2010): 595–607.

71 Koehler, “Right-Wing Extremism and Terrorism in Europe”; Daryl Johnson, Right Wing Resurgence: How a Domestic Terrorist Threat Is Being Ignored (Rowman & Littlefield, 2012).

72 Haggerty and Bucerius, “Radicalization as Martialization: Towards a Better Appreciation for the Progression to Violence.”

73 Mudde, “Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe Redux”; Carter, “Right-Wing Extremism/Radicalism: Reconstructing the Concept.”

74 Daniel F. McCleary and Robert L. Williams, “Sociopolitical and Personality Correlates of Militarism in Democratic Societies,” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 15, no. 2 (2009): 161–87.

75 Jenning and Marcus took into account the “duration, intensity, recency, affective orientation, and salience of the serviceman’s institutional experience” (Jenning and Marcus, “The effect of military service on political attitudes: A panel study,” 146) to measure “the degree to which the military experience impinges on individual political attitudes and evaluation.” In addition, the differential experience of military training and deployment on affect and soldier salience is also postulated as important (Ibid., 134).

76 Jensen, Atwell Seate, and James, “Radicalization to Violence: A Pathway Approach to Studying Extremism.”

77 Ibid.

78 McCleary and Williams, “Sociopolitical and Personality Correlates of Militarism in Democratic Societies”; Chatagnier and Klingler, “Would You Like to Know More? Selection, Socialization, and the Political Attitudes of Military Veterans.”

79 Steve James, “The Policing of Right-Wing Violence in Australia,” Police Practice and Research 6, no. 2 (2005): 103–19.

80 David Schkade, Cass R. Sunstein, and Reid Hastie, “When Deliberation Produces Extremism,” Critical Review 22, nos. 2–3 (2010): 227–52.

81 Dean, Bell, and Vakhitova, “Right-Wing Extremism in Australia: The Rise of the New Radical Right.”

82 Ehud Sprinzak, “The Process of Delegitimation: Towards a Linkage Theory of Political Terrorism,” Terrorism and Political Violence 3, no. 1 (1991): 50–68.

83 Sheila Frankfurt and Patricia Frazier, “A Review of Research on Moral Injury in Combat Veterans,” Military Psychology 28, no. 5 (2016): 318–30.

84 Jensen, Atwell Seate, and James, “Radicalization to Violence: A Pathway Approach to Studying Extremism.”

85 Ehud Sprinzak, “Right-Wing Terrorism in a Comparative Perspective: The Case of Split Delegitimization,” Terrorism and Political Violence 7, no. 1 (1995): 17–43.

86 Tage Shakti Rai and Alan Page Fiske, “Moral Psychology Is Relationship Regulation: Moral Motives for Unity, Hierarchy, Equality, and Proportionality,” Psychological Review 118, no. 1 (2011): 57.

87 Sprinzak, “The Process of Delegitimation: Towards a Linkage Theory of Political Terrorism.”

88 Koehler, A Threat from Within?: Exploring the Link between the Extreme Right and the Military.

89 Nitzan Shoshan, The Management of Hate: Nation, Affect, and the Governance of Right-Wing Extremism in Germany (Princeton University Press, 2016).

90 Moral injury is an expression of a grievance following a betrayal. The concept connects behaviorial consequences from “grossly disturbing violent wartime experiences such as killing civilians or failing to prevent atrocities” (Frankfurt and Frazier, “A Review of Research on Moral Injury in Combat Veterans,” 319). It is defined as a perceived betrayal by military or political leaders or leadership of sovereign solidarities (James A. Piazza, “The Determinants of Domestic Right-wing Terrorism in the USA: Economic Grievance, Societal Change and Political Resentment,” Conflict Management and Peace Science 34, no 1 (2017): 52–80). Betrayal grievance encompasses the perceived injustice and sets up the object of hostility; this connects extremism and moral injury literatures (Piazza, “The Determinants of Domestic Right-wing Terrorism in the USA). It is expressed through the prism of veteran experience in the cognitive dissonance originating in the belief superiors or government authorities have betrayed the soldier sacrifice (Brett T. Litz, Nathan Stein, Eileen Delaney, Leslie Lebowitz, William P. Nash, Caroline Silva, and Shira Maguen, “Moral Injury and Moral Repair in War Veterans: A Preliminary Model and Intervention Strategy,” Clinical Psychology Review 29, no. 8 (2009): 695–706).

91 Where the decision to initiate a war of aggression “is not only an international crime; it is the supreme international crime differing only from other war crimes in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil of the whole” (International Avalon Project for Germany 1946).

92 Jensen, Atwell Seate, and James, “Radicalization to Violence: A Pathway Approach to Studying Extremism.”

93 Please note that our subsequent analysis supports the correlation between martialisation and right wing extremism and that the intervening steps (exposure to unjust war and consequent worldview reset and reinforcement) are extrapolated from: Jensen, Atwell Seate, and James, “Radicalization to Violence: A Pathway Approach to Studying Extremism.”

94 Ibid.

95 Krebs (“A school for the nation?”) argues that the military is not proven to be an effective inculcator of durable values given the high contextuality of identity (contrary to Jenning and Markus (“The effect of military service on political attitudes: A panel study”); but in line with Lawrence and Kane (George H. Lawrence and Thomas D. Kane, “Military Service and Racial Attitudes of White Veterans,” Armed Forces & Society 22 no. 2 (1995): 235–55). Jensen, Atwell Seate, and James (“Radicalization to Violence”) develop 71 causal mechanisms that were categorized under 10 conceptual constructs and found that 85% of the cases were fully explained in root conditions incorporating “community crisis”, “psychological vulnerability” and “psychological rewards” (Ibid., 14). They concluded that “[s]ocial identity perspectives show how biasing dynamics convince individuals that their personal deficits are largely the result of their membership in a community that has been collectively victimized or threatened. As individuals and groups become more insular, mechanisms of cognitive bias, such as groupthink, in-group/out-group bias, and diffusion of responsibility, set in, convincing individuals that the alleviation of community grievances and the amelioration of threats to community survival will only occur through violent action.”

96 Jeffrey L. Bleich, The Future of US and Australian Collaboration: How We Remain the Lucky Alliance (Melbourne: Sir Robert Menzies Lecture Trust, 2012).

97 Andrew Shearer, Uncharted Waters: The US Alliance and Australia’s New Era of Strategic Uncertainty (Lowy Institute for International Policy Sydney, 2011).

98 Rose, “The Future of the ANZUS Alliance” (Young Australians in International Affairs, February 5, 2018), https://www.youngausint.org.au/post/2018/02/05/the-future-of-the-anzus-alliance.

99 Shearer, Uncharted Waters, 12.

100 Carter, “Right-Wing Extremism/Radicalism: Reconstructing the Concept.”

101 Gary King, Michael Tomz, and Jason Wittenberg, “Making the Most of Statistical Analyses: Improving Interpretation and Presentation,” American Journal of Political Science (2000): 347–61.

102 Robinson, Nick, “Militarism and Opposition in the Living Room: The Case of Military Videogames,” Critical Studies on Security 4, no. 3 (2016): 255–75; Luther Elliott, Andrew Golub, Matthew Price, and Alexander Bennett, “More Than Just a Game? Combat-Themed Gaming among Recent Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder,” Games for Health Journal 4, no. 4 (2015): 271–77; Jackson, Joachim, Robinson, and Schneiker, “Assessing Meaning Construction on Social Media: A Case of Normalizing Militarism.”

103 Victoria M. Basham, “Liberal Militarism as Insecurity, Desire and Ambivalence: Gender, Race and the Everyday Geopolitics of War,” Security Dialogue 49, no. 1–2 (2018): 32–43.

104 Dean, Bell, and Vakhitova, “Right-Wing Extremism in Australia: The Rise of the New Radical Right.”

105 Cass R. Sunstein, “Is Social Media Good or Bad for Democracy?,” SUR International Journal on Human Rights 15, no. 27 (2018): 83–89.

106 Jensen, Atwell Seate, and James, “Radicalization to Violence: A Pathway Approach to Studying Extremism.”

107 Smith, Blackwood, and Thomas, “The Need to Refocus on the Group as the Site of Radicalization.”

108 Jensen, Atwell Seate, and James, “Radicalization to Violence: A Pathway Approach to Studying Extremism.”

109 Ryan Scrivens and Barbara Perry, “Resisting the Right: Countering Right-Wing Extremism in Canada,” Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 59, no. 4 (2017): 534–58.

110 Dean, Bell, and Vakhitova, “Right-Wing Extremism in Australia: The Rise of the New Radical Right.”

111 Khalil, “The Three Pathways (3P) Model of Violent Extremism.”