What conflict-theoretical lenses can we apply to the study of transnational jihad? The topic of trans-national jihadism can be examined from at least two angles. On one side we have radicalization research that has focused on networks, trans-national mobilization and individual processes to embracing violent jihad across battlefields.Footnote1 On the other side we have the more nascent approaches within Peace and Conflict research that have approached jihadist wars as a potentially “exceptional” type of civil warFootnote2: one which is harder to solve with conventional conflict resolution mechanisms, one which is harder to contain, one which has a particular religious dimension to it with otherworldly rewards, which make the conflicts extraordinary diehard. While on the individual level, different radicalization models have been developed in an attempt to understand personal and interpersonal dynamics leading to choices to travel abroad,Footnote3 the same is not true when it comes to understanding jihadism as a particular form of conflict.Footnote4 With this special issue, the intension is to push further the thinking on jihadist conflicts as a form of conflict, hence broadening the scope of the literature that deals with jihadi actors as part of a civil war.Footnote5

Recent conflicts in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen and the Sahel where jihadi actors have been involved, and the subsequent debates on the consequences of international and regional intervention/non-intervention have displayed a rare degree of conflict complexity. The conflict constellations in all the above places have been characterized by conflicts taking place simultaneously at multiple levels, with local, regional, global actors who have had a stake in the conflicts. The manifestation of the Arab Spring in Syria that started with protests against an authoritarian regime in 2011, but quickly turned into a stage for regional rivalry, sparked a myriad of different non-state actors, a full-blown civil war, and international military interference is an example of this sort of complexity. Not only did it become a conflict arena that had the potential to turn into “a third world war” as many observers then warned, but the reality on the ground also challenged neat conflict resolution thinking, and questions about who to arm/not to arm divided the international community. Due to the involvement of jihadist actors—some local, other foreigners—and eventually with the establishment of ISIL and the territorial caliphate, the conflict became further complicated. Yet, this was not only due to multiple actor-types on the ground, but assumingly also due to non-material aspects driving the conflict, such as ideology, religion, emotions, and trans-national communication.

These conflict traits are not necessarily a reflection of a novel development. Some of them resemble the situation during the Cold-War kind, where a string of conflicts became bundled together in an ideological macro-narrative. What is perhaps more interesting about such developments is that they remind us of the scarcity in frameworks that can help us understand the characteristics of macro-level conflict constellations. Perhaps this is also one of the main reasons why contemporary peace research has concluded that a remarkable lesson from the jihadist conflicts of today is that conflict-resolution appear to be more complicated, and conflicts harder to manage when jihadi actors are involved. In order to advance from this conclusion, a fruitful way forward seem to be detangling the different processes of transnationalization (what exactly happens when conflicts escalate to a non-manageable point), and with it, the different dimensions and layers that enable the processes to take place.Footnote6 The rationale for this would be to have a multidimensional approach to conflict-resolution thinking, that initially would require debundling.

In the introductory pages below, I hightlight what the study of jihadist cases can bring to our understanding of transnationalization. The special issue consist of in-depth empirical studies of transnational jihadist movements in Yemen, Mali, Syria, Afghanistan and Pakistan, but also quantitative studies of trends and patterns in South Asia and globally. Inspired by the empirical contribtutions and the broader literature on transnationalization, the introduction at hand also proposes a model to examine macro-level conflicts, implying not only globalization processes or conflict-extension (a widening of the battlefield), but a proliferation of conflicts along different dimensions. Hopefully this model can be useful for future analyses of empirical cases, but also as a depiction of how transnational jihadism can be thought of as a bundled conflict-constellation.

Rethinking Transnationalization: Globalization, Conflict Extension and Macro-Securitization

The cases of jihadist conflicts elaborated in this special issue can contribute to the wider literature on jihadism, but also our conceptual understanding of transnationalization.Footnote7 There are two main trends in the broader literature dealing with transnationalization dynamics. The first trend—mainly derived from sociological literature—approaches transnationalization as an expression of globalization.Footnote8 Based on the observation that a novel aspect of jihadist conflicts seems to be the speed by which the transnationalization of conflicts can happen, this perspective is of course relevant. However, the transnationalization of conflicts is not only a globalization phenomenon based on revolutions in the means of global mass-communication, migration or increased global interaction. In another sense they are also about anti-globalization: Liberal democracies have been acting more autonomously in defense and security-related questions, putting their countries “first”, breaking with old ideological pacts, and not least with the globalization theories of liberal peace.Footnote9 Hence, somehow paradoxically, transnationalization can reflect anti-globalization policies and sentiments.

Thinking about transnationalization as globalization can be a sociological way of explaining speed, increased communication, connectedness, and “easier” emotional mobilization across borders. Stephen Pinker put forward an interesting theory that several historical shifts in society have contributed to a decline in violence over time.Footnote10 The immediate periods of peace after World War II and the Cold War were for example accompanied by decreases in both interstate and intrastate wars. This indicated a negative relationship between globalization and conflict. The idea behind his theory was that historical shifts encompassed in globalization created incentives that increased the opportunity cost of conflict: suddenly states could have more to lose in terms of political allies, social gains and trade benefits.Footnote11 Much has been written on how globalization generates or accentuates conflict, while little has been written on how conflict and globalization interact to produce both peaceful and violent results.Footnote12 This is because the main argument is drawn from the “liberal” premise that globalization, through integration and economic interdependence dampens the likelihood of conflicts.Footnote13

A fruitful alternative to approaching conflict potential as a direct effect of globalization, is to view both globalization and transnationalization—not as sociological processes that have in-built or embedded causalities—but as ideologies. As described by Manfred B. Steger,Footnote14 it makes sense to differentiate between different ideologies of globalization, and rather than haven reached the “end of ideology”, we find ourselves in the throes of an intensifying ideological struggle over the meaning and direction of globalization. Steger argues that the three clashing political belief systems of our time are market globalism, justice globalism, and religious globalism, and shows how these “globalisms” have developed and how their competing ideas articulate and legitimize particular political agendas.Footnote15 Jihadist conflicts can also be seen as an expression of this battle of ideas and the powerful surge of antiglobalist populism—an ideological contender that stands in tension to pluralist values of liberal democracy and challenge the universalist claims of that form of globalization ideology.

The second trend—that is particularly derived from the peace and conflict research literature—approaches transnationalization as conflict extension. In the broader PCR literature, transnationalization is conceptualized as the involvement of external actors in domestic conflicts (conflict extension theories); as an effect of a disjuncture between the state-system and multi-ethnic communities (particularly the literature on the internationalization of ethnic conflicts has this approach embodied in the interaction theories), or as an instrumental tool for leaders who aim at creating internal coherence by entering into disputes with other states (conflict transformation theories).Footnote16 These theories are limited by their focus on external intervention in civil wars, by their descriptive more than explanatory contribution, or by their focus on the instrumental gain of power holders, when conflicts are transformed from the national to the international. Literature on conflict diffusion has also dealt with diffusion as a spill-over mechanism, using the term to describe the spread of instability from one geographic area to another. Though diffusion implies a dynamics between the area of the initial conflict and another area to which the conflict spread (through actors, ideologies, and permissive conditions), the main idea is that there is an “original” conflict that expands or escalates.Footnote17

While the new PCR literature on jihadist conflicts has taken over the prevailing understandings from conflict extension theories, the theory of (macro)securitization formulated by the Copenhagen School of Security StudiesFootnote18 can add some value to the conceptual thinking around transnationalization processes. Macro-securitization, a term coined by Barry Buzan and Ole Waever, departs from the idea that sometimes international security can be structured by one dominant conflict, as happened during the Cold War.Footnote19 Jihadist conflicts can be understood through this lens, as it contains an overarching narrative in which the West and Islam represent opposing sets of values and ideas of governance.Footnote20 During the Cold War, local/national conflicts (e.g. in Central America Mozambique or Angola) became enlarged and complicated by becoming hot-spots and framed within the overarching construction of the grand struggle between East and West. As described by Buzan and Waever, macrosecuritizations generate constellations, because they structure and organize relations and identities around the most powerful call of a given time. When two macrosecuritizations are mutually opposed, each construing as the ultimate threat what the other defends, they generate one integrated constellation. This way, the Cold War became a constellation containing two momentous macrosecuritizations and a huge network of identities and policies interlinked around these. Macro-securitization hence points at the alignment of a local, conflict narrative with global or regional resonance, which is possible as the reference object is not territorially bound.Footnote21

The securitizations of jihadist are driven by complicated transnational dynamics that ultimately are difficult to relate to a single securitizing move, a single securitizing actor or an “original conflict”. While securitization theory and the way it is applied has typically focused on mid-level securitizations (the level of the state/nation), Buzan and Waever argues that when larger framings are in play (presented as secular or “universal” religious ideologies, or as civilizational-scale identities), this “purely egotistical model cannot capture the possibilities for large numbers of individual securitizations to become bound together into durable sets.”Footnote22 According to the theory, successful macro-securitization depends not just on (who holds) power, but more on the existence of shared fundamental values/principles, shared threat perceptions, and “on the construction of higher-level referent objects capable of appealing to, and mobilizing, the identity politics of a range of actors within the system.”Footnote23 Hence, an analysis of the processes of macro-securitization requires the combination of looking into the mobilization of an audience on a micro-analytical scale, which the radicalization literature has typically done,Footnote24 and the meta-level narratives and speech acts that transform an issue from being a local-level concern to becoming a global/trans-national concern, attracting new/broader audiences.

Thinking of transnationalization as macro-securitization can simultaneously open up for a new way of thinking conflict containment, which is more about delinking the local conflicts from ideological macro-level conflict structures, and less about thinking of resolution within a civil war context, in which conflict-resolution mechanisms, such as granting autonomy to rebel groups/power sharing,Footnote25 or negotiating the conditions for peace on a national level are the center of attention.Footnote26 Whereas the meaning of resolution can vary according to different conflict theories,Footnote27 resolution can hence also be an effect of containment-efforts. This is based on the idea that escalation of conflicts is a self-referential displacement that can be minimized—an idea developed by Johan Galtung,Footnote28 who approached conflicts as a dynamic phenomenon, instead of highlighting the limited value of searching for the root causes of a conflict.Footnote29 Additionally, the concept of a “constellation” serves to avoid a picture of isolated securitizations that are unrelated to conflict processes at other levels.

One could organize the different litteratures and persepctives presented above according to different analytical interests and questions. First why does transnationalization happen? Sociologically this can be approached by looking at “enablers” and particularly the globalization literature might provide some answers such as globalized social media, technological revolutions, migration, evolutions in communication and connectivity pace. The focus is hence on components that can explain the structural conditions for transnationalization processes.

A second question—one that is arguably dominant within the literature on jihadism—is what happens, when a conflict has become transnational? This sort of literature is often descriptive, focusing on network and alliance formation or migration. If PCR was to answer this question, the most natural measurement would be to look at escalation-indicators such as the level of violence (number of attacks or number of casualties), stakeholders/involved parties, and the extension of the battlefield.

A third question, that can be derived particularly from the literature on macrosecuritization is, what characterizes the transnationalization process itself? This is not detached from the more explanatory question of why transnationalization happens, but analytically it looks into the “hows” of the processes. Understanding the potential for macrosecuritization of a conflict one must move along several axes that lead to a higher or lower level of transnationalization, hence taking into consideration that there can be different degrees of transnationalization. The more layers, and the more non-material enablers, the more complicated the conflict gets, and containment efforts therefore need to think in terms of simplification i.e. removing layers (for example by reducing involved actors/actor-types) and containing enablers (both material and non-material). The three questions (a) why does transnationalization occur, (b) what characterize the transnationalization processes, and (c) what happens once a conflict is transnationalized could in principle be placed on a timeline, marking different phases of conflict, but at the same time they also represent differences in analytical interest. The contributions in this special issue speak to all the three sorts of questions, as I describe below.

What Characterizes Transnational Jihad?

If we look at existing ways of understanding transnational jihadism, then it is distinguished by its ability to attract foreign fighters—either from neighboring countries or from other regions.Footnote30 As the contributions in this issue show it also implies organizational collaboration between local jihadi movements and the leadership organizations of AQ or IS, which means that transnational jihadi movements often operate in other countries than their place of origin. Collaboration can either mean that local movements reach out to IS or AQ (as shown by some of the contributions), or that IS/AQ strategically provides training, logistics, leadership, and funding to local movements.Footnote31 When we speak about transnational jihadi conflicts it additionally implies a situation that attracts external military intervention from other states or non-state actors in support of, or against, at least one of the warring parties. Finally, a characteristic of trans-national jihadist conflict is often that the demands or conflict-claims made by jihadists transcend national borders, which implies that they ideologically represent a challenge to the westphalian thinking on the state-system. This is however not always the case since foreign fighters can join different battlefields without believing in the necessity of establishing a transnational caliphate.

In his contribution to this special issue, Dino Krause zooms in on the aspect of transnationalization that has to do with the integration processes between local movements and transnational jihadist organizations. Examining the level of violence attached to trans-national groups as a measure of transnationalization, Krause sets off from the premise that South Asia is a non-case when it comes to “successful transnationalization”. The relatively low levels of violence—despite what one might expect from the regional characteristics—are primarily attributed to two explanations: the constricted need that local movements have had for external material support, and the opportunities for existing Islamist parties to voice their ambitions through democratic channels. Overall, turning these findings on their head, one could draw out that local needs for external support networks, and an oppressive approach to Islamist parties and movements ought to be factored in as potential drivers of transnationalization processes.

In her contribution, Maria-Louise Clausen zooms in on transnationalization as being mainly a rational “franchising decision” taken not from the leadership organization, but equally from the local affiliate organization. Inspired by the language and literature on proxy war, her underlying understanding of transnationalization is that it reflects the degree of dependence that the client (the local affiliates of AQ) has on the patron (the central leadership movements). Clausen too point at the availability of internal/external sources of support, as one factor that can explain inter-organizational dynamics within trans-national jihadist organizations or the “franchising decisions” in the Yemeni context. Clausen also allude to the significance of how different agenda’s—international, regional, domestic—play out in the local context for understanding transnationalization—a point that has to do with the potential for alignment of the different agenda’s and/or the strategic use of certain agendas to boost local legitimacy.

In their contribution, Isak Svensson and Desirée Nilsson explore which local grievances and fault lines (sectarian, inter-religious or ethnic) are often mobilized upon. With their conclusions they explain transnationalization as a process where preexisting identity cleavages are reproduced through the mobilization by trans-national jihadi groups. Despite the jihadist’s claims that they transcend ethnic differences, their quantitative study demonstrates that on a global scale, they most commonly mobilize on ethnic grounds, be it to “defend” the Fulanis, Bengali Muslims, Kanuris, Uyghurs, Basogas, Somalis, Kurds, Palestinian Arabs, Tuaregs, White Moors, Mwani, Chuvashes, Chechens, or Southern Shafi’is. Hence, in an overall perspective, societal cleavages—ethnic, and to a lesser degree sectarian—increase the transnationalization potential of conflicts, where jihadis are involved as part.

In their contribution, Jerome Drevon & Patrick Haenni dive into the case of Syria, and describe why Jabhat an-Nusra “de-transationalized” and became the more locally oriented HTS. They base their analysis on four dimensions of transnationalization, namely the oath of allegiance, the ideological traits, the modus operandi, and the interconnectedness and show how transnationalism became particularly costly for the movement leading it to “localization”. With HTS’s promoting the establishment of unified structures of governance in Northwest Syria, the contradictions between the interests of the local Syrian jihad and AQ had become increasingly stark. Like Clausen, the authors stress the strategic interest and rationality from the perspective of the local affiliate.

Signe Marie Cold-Ravnkilde and Boubacar Ba investigate the significance of ideology in order to explain expanding jihadist groups in the Sahel. From this perspective, transnationalization is an effect of increased competition, as they show how different jihadist groups in Mali compete to mobilize new followers, representing competing models of jihadist governance. Intra-jihadist contestation between the groups in Mali is hence represented as both “a cause and an effect” of expanding jihadist groups in the Sahel. Once there is ideological rivalry among different jihadi groups, the conditions for expansion, and transnationalization seem to be increasingly nourished.

Amira Jadoon zooms in on operational behavior as one aspect of transnationalization. The focus on how the alliance with a global jihadist movement effect the military operations of local militant groups on the ground is examined through a study of the alliance between the Islamic State’s official affiliate in Afghanistan and Pakistan—Islamic State Khorasan (ISK)—and two jihadist groups in Pakistan: Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) and Jamaat-ul-Ahrar (JuA). Specifically, the study examines changes in respective group’s target selection, tactics, and geographical expansion before and after the alliance with ISK. Opposite the transformation observed by Jerome Drevon & Patrick Haenni, this contribution describes the movement that can happen from the local to the trans-national and how exactly it affects behavior.

Thinking in Layers and Dimensions

The brief review above and the insights from the contributions to this special issue, leads to a conflict analysis framework to examine macro-level conflicts like jihadist conflicts. What I define as macro-level conflicts are conflict constellations, that have the ability to mobilize both local conflicts and cleavages within a country and international (state) or transnational (non-state) actors and align them according to a particular—common—worldview.Footnote32 It does not represent a scale above the international,Footnote33 but rather “bundled conflicts” where common conflict variables applied in PCR such as the conflict claims of the involved parties, scarcity and grievance are hard to delineate neatly. They are also different from what PCR and war studies might categorize as large-scale conflicts often measured in terms of high numbers of fatalities or a high level of violence, which do not capture the ideological dynamics (its reach) or the conflict complexity that this text is alluding to.

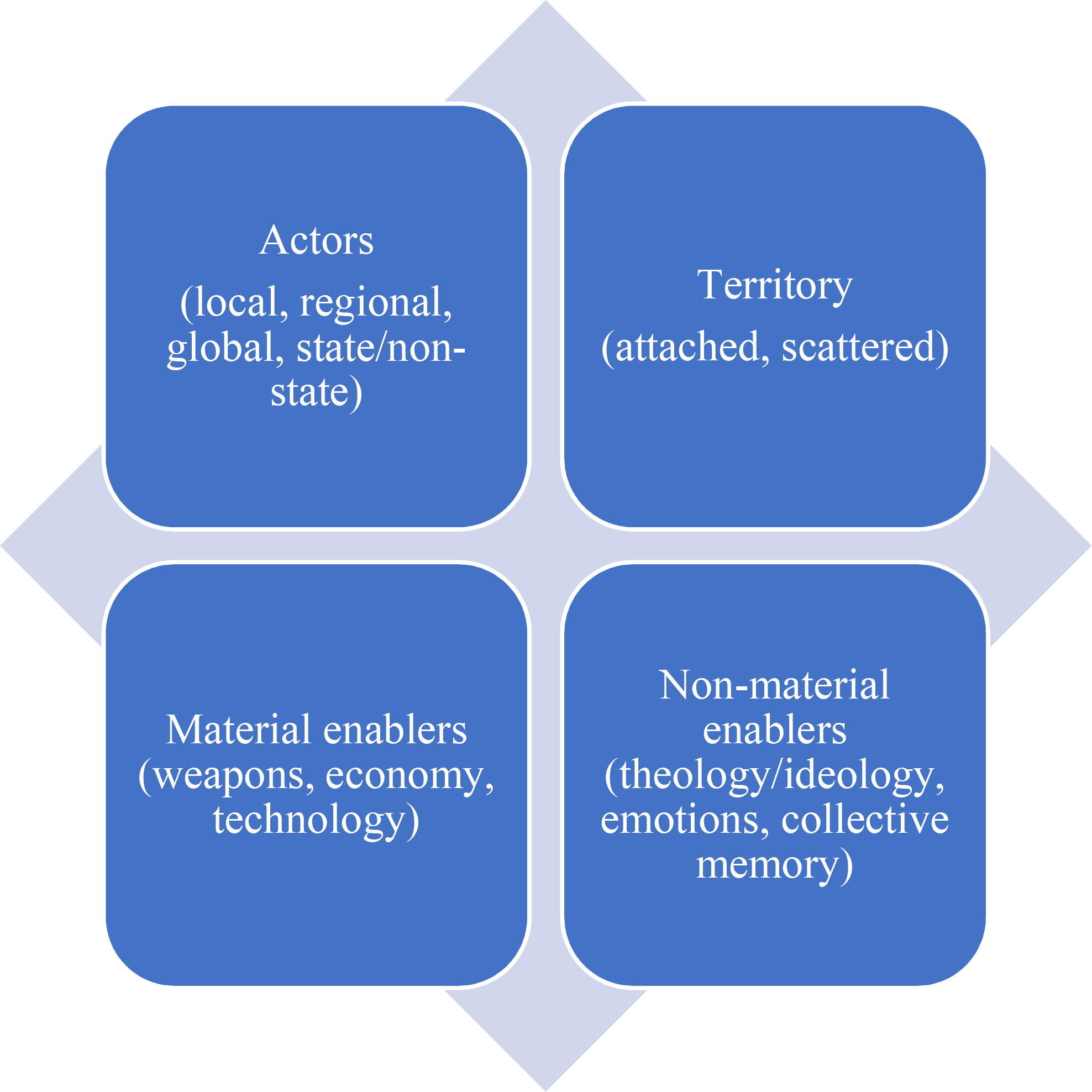

The model below depicts four fields that can also be thought of as four axes along which potential escalation and transnationalization can take place. The first axis represents conflict layers i.e. how many/who are the actors involved. These can be disentangled by examining the conflict constellation of local, regional, and global actors as several of the contributions to this issue do. However, as already argued, transnationalization is not only an extension of the number of the involved actors and an expansion of the conflict territory, but potentially also a multiplication of the conflict into a budding conflict/web of conflict. Hence if you have many different types of actors involved, it would also mean more accounts of what the conflict is about, and hence one should consider the “multiple shifting accounts of what the conflict is about are part of the texture of action itself, not something that stands behind it and guides it like a puppeteer pulling the strings”.Footnote34 Seen in this light escalation becomes “a process of increased ‘conflictness’.”Footnote35

The second axis relates to the territory or countries involved. In the cases of jihadist conflicts explored in this special issue, we have seen the spill-over of conflict dynamics to neighboring countries in e.g. the Sahel, in Afghanistan/Pakistan, Syria/Iraq, but also transnationalization processes that are more scattered in the sense that the movements “pop up” in different—territorially unrelated—regions or countries. Al-Qaeda for example popped up in Maghreb, on the Arab peninsula, in Sahel in the wake of 2001. The same dynamics occurred in relation to the Islamic State movement after 2014, where it popped up in different regions as self-declared provinces. One could argue that a movement operating across two neighboring countries represents a lower degree of transnationalization, than a movement operating in territory that is scattered since it indicates that the movement has resonance beyond the local or regional dynamics at a given place.

The third and fourth axes can be understood as enablers. These are also described in several of the contributions, but also in the broader literature on transnationalization as globalization. On one side the material ones such as weapons, technology (including mass-media), economy/money flows, where there are several indications in the cases presented in this issue that local groups can be boosted with weapons, propaganda channels, or money flows coming from the central leadership movements of the IS or AQ. On the other side, since transnationalization is also conditioned by the resonance of the conflict imagery represented by the movements, non-material enablers such as theology, ideology, emotions, collective memory are also important focal areas. The more enablers, the higher probability for transnationalization, escalation and macro-securitization. One example is the resonance of IS propaganda in Syria and Iraq—two countries that contain central sites that can be found in apocalyptic narratives and were the centers of producing theories about the nature of the caliphate for approximately 500 years.Footnote36

Analytical Model for Examining Bundled Conflict-Constellations like Transnational Jihadism

The analytical model above is not particular for transnational jihadist conflicts, but can potentially be utilized to understand the escalatory dynamics in other cases of macro-securitization and in cases where the utility of traditional conflict resolution mechanisms seems to be limited. The approach here represents a shift away from looking at underlying causes or some preexisting features as the explanation for jihadist conflicts, instead grasping its dynamics, or the interplay between the different dimensions of transnationalization. Statistical variables that explain frequencies, can be seen part of these dynamics, but violence does not remain a sole measure for intensity, as is often the case in conflict analysis. Furthermore, this represent a move away from conceptualizing transnationalization as a rational and intentional process,Footnote37 even though both the material and non-material enablers can be used by strategic actors for mobilization purposes as some of the contributions in this issue lay out. Finally, the model can provide inspiration to containments thinking in the face of conflicts where the dynamics of macro-securitization are at play. The guiding principles for containment efforts in these sorts of constellations seem to suggest that simplification is a way toward containment: reducing the actor-types involved (and thereby also the number of conflicts involved), reducing territorial conflict-extension, and developing strategies to reduce the influx and impact of both material and non-material enablers. The last-mentioned calls for more peace and conflict research on the transformation of non-statistical factors such as theology, ideology, emotions, and collective memory.Footnote38

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the European Research Council for funding the research project “Transnational Jihad—Explaining Patterns of Escalation and Containment” of which this publication is an output. I also want to thank the two anonymous reviewers of this issue, and their very helpful and constructive reviews. Finally I am grateful to the assistance from Telli Betül Karacan, and to Maja Lorenzen in helping to give the issue a final shape.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See e.g. Stephen Tankel, Kim Cragin, Thomas Hegghammer, and Aaron Zelin, "Book Review Roundtable: Foreign Fighters in the Armies of Jihad," Texas National Security Review (August 2, 2021), https://tnsr.org/roundtable/book-review-roundtable-foreign-fighters-in-the-armies-of-jihad/.

2 Desirée Nilsson and Isak Svensson, “The Intractability of Islamist Insurgencies: Islamist Rebels and the Recurrence of Civil War,” International Studies Quarterly 65, no. 3 (September 2021): 620–32, https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqab064.

3 Georgia Holmer, Countering Violent Extremism: A Peacebuilding Perspective, Special Report 336 (United States Institute of Peace, 2013).

4 For the Peace and Conflict Research (PCR) literature on jihadist conflicts, where the starting point of analysis is thinking about jihadist conflict within a civil war framework, see Isak Svensson and Daniel Finnbogason, "How Jihadist States End: Tracing the End Dynamics of Revolutionary Islamist States." Risk, Roots and Responses: Nordic Conference on Research on Violent Extremism (2017); Isak Svensson, Ending Holy Wars: Religion and Conflict Resolution in Civil Wars (Australia: University of Queensland Press, 2013).

5 Stathis N. Kalyvas, "Jihadi Rebels in Civil War," Daedalus 147, no. 1 (2018): 36–47; Tanisha M. Fazal, "Religionist Rebels & the Sovereignty of the Divine," Daedalus 147, no. 1 (2018): 25–35; Elizabeth R. Nugent, "Islamist Radicalization and Civil War," APSA MENA Politics Newsletter 3, no. 1 (2020): 42–43. https://pomeps.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/1-APSA-MENA-Politics-Newsletter-Spring-2020-FINAL.pdf; Morten Valbjørn and Jeroen Gunning, "Islamist Identity Politics in Conflict Settings," APSA MENA Politics Newsletter 3, no. 1 (2020): 44–47. https://pomeps.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/1-APSA-MENA-Politics-Newsletter-Spring-2020-FINAL.pdf; Nicholas Lotito, "Islamism in Civil War," APSA MENA Politics Newsletter 3, no. 1 (2020): 39–42. https://pomeps.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/1-APSA-MENA-Politics-Newsletter-Spring-2020-FINAL.pdf; Mohammed M. Hafez, "Fratricidal Rebels: Ideological Extremity and Warring Factionalism in Civil Wars," Terrorism and Political Violence 32, no. 3 (2020): 604–29; Marc Lynch, "Is There an Islamist Advantage at War?," APSA MENA Politics Newsletter 2, no. 1 (2019): 18–21. https://apsamena.org/2019/04/16/is-there-an-islamist-advantage-at-war; Barbara F. Walter, "The Extremist’s Advantage in Civil Wars," International Security 42, no. 2 (2017): 7–39; Christopher Phillips and Morten Valbjørn, "’What is in a Name?’: The Role of (Different) Identities in the Multiple Proxy Wars in Syria," Small Wars & Insurgencies, 29, no. 3 (2018): 414–33.

6 Some scholars have recently disentangled different dimensions of transnationalization. As pointed out by Emy Matesan (forthcoming 2022) and Dino Krause (forthcoming 2022) it can be helpful for containment-thinking to disaggregate the different dimensions of transnationalization, since not all movements score high on all the different measures for transnational jihadi conflicts.

7 Existing literature on jihad and globalization or transnationalism includes e.g. James Piscatori and Amin Saikal, Islam beyond Borders: The Umma in World Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019); Susanne Hoeber Rudolph and James Piscatori, Transnational Religion and Fading States (Boulder: Westview Press, 1996); Peter Mandaville, Transnational Muslim Politics - Reimagining the Umma (London: Routledge, 2001); Oliver Roy, Den Globaliserede Islam (Copenhagen: Vandkunsten, 2004); Giulia Cimini and Beatriz Tomé-Alonso, "Rethinking Islamist Politics in North Africa: A Multi-Level Analysis of Domestic, Regional and International Dynamics," Contemporary Politics (2021): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2020.1870257.

8 E.g. Roland Robertson, Globalization - Social Theory and Global Culture (London: Sage, 1992).

9 The security political behavior of the US and France in the War on Terror (e.g. the “autonomous” US withdrawal from Afghanistan and French alliance building in Sahel) are good examples of how globalization can be interlinked with anti-global policies.

10 Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: The Decline of Violence in History and Its Causes (UK: Penguin, 2011). Similar aspects were elaborated in Goldstein, Winning the War on War: The Decline of Armed Conflict Worldwide and in Mueller, Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War. See also Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man, which can also be read as an argument for the decline of violence as an effect of globalization.

11 Carolyn Chisadza and Manoel Bittencourt, “Globalisation and Conflict: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa,” International Development Policy | Revue internationale de politique de développement 10, no. 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.4000/poldev.2706.

12 Alan Tidwell and Charles Lerche, “Globalization and Conflict Resolution,” International Journal of Peace Studies 9, no. 1 (2004): 47–59.

13 For instance, liberal approaches are of the view that economic interdependence promotes peace whilst structuralist argue that international conflicts are as a result of globalization. The premise of liberal linkages between trade and conflict reduction is thus not new as many have in the past, argued that the primary goal for trade is to bring about peace between trading partners. Bonginkosi Mamba, André B. Jordaan, and Matthew Clance, “Globalisation and Conflicts: A Theoretical Approach,” University of Pretoria, Department of Economics (2015): 1–26.

14 Manfred B. Steger, “Ideologies of Globalization: Market Globalism, Justice Globalism, Religious Globalisms,” in Globalization: A Very Short Introduction, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013). The chapter investigates the ideologies underlying globalization, which endow it with values and meanings. Market globalism advocates promise a consumerist, neoliberal, free-market world. This ideology is held by many powerful individuals, who claim it transmits democracy and benefits everyone. However, it also reinforces inequality, and can be politically motivated. Justice globalism envisages a global civil society with fairer relationships and environmental safeguards. They disagree with market globalists who view neoliberalism as the only way. Religious globalisms strive for a global religious community with superiority over secular structures. Manfred B. Steger, Globalisms - Facing the Populist Challenge (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2019).

15 Steger focuses especially on the ways this battle of ideas has been extended through the unexpectedly powerful surge of anti-globalist populism, an ideological contender that stands in tension to pluralist values of liberal democracy.

16 David Carment, Patrick James, and Zeynep Taydas, “The Internationalization of Ethnic Conflict: State, Society, and Synthesis,” International Studies Review 11, no. 1 (2009): 63–86.

17 Michael E. Brown, ed., The International Dimensions of Internal Conflict (London: MIT Press, 1996); Roslyn Simowitz, “Evaluating Conflict Research on the Diffusion of War,” Journal of Peace Research 35, no. 2 (1998): 211–30; Benjamin A. Most and Harvey Starr, “Diffusion, Reinforcement, Geopolitics, and the Spread of War,” The American Political Science Review 74, no. 4 (1980): 932–46; David A. Lake and Donald Rothchild, eds., The International Spread of Ethnic Conflict: Fear, Diffusion, and Escalation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998).

18 Barry Buzan, Ole Waever, and Jaap de Wilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998).

19 Barry Buzan and Ole Waever, “Macrosecuritization and Security Constellations: Reconsidering Scale in Securitization Theory,” Review of International Studies 35, no. 2 (2009): 253–76.

20 As argued by Buzan and Waever: “The relevance of such higher-level securitisations is not just historical. After September 11th, 2001 (9/11) the Bush (and Blair) administrations tried to do something similar with the so-called ‘Global War on Terror’ (GWoT). The contemporary discourse about climate change increasingly also takes this higher-level form, and examples from earlier ages include the Crusades (mobilizing in the name of a ‘universal’ religion), and the 18th and 19th century mobilization of monarchies against the threat of republicanism.” Ibid., 254.

21 One should note that macro-securitization processes do not necessarily imply globalization, but can also be regional in scope. See e.g. Morten Valbjørn and André Bank, "The New Arab Cold War: Rediscovering the Arab Dimension of Middle East Regional Politics," Review of International Studies 38, no. 1 (2012): 3–24.

22 Ibid., 256.

23 Ibid., 268.

24 Peter Neumann, “The Trouble with Radicalization,” International Affairs 89, no. 4 (2013): 873–93.

25 Caroline Hartzell and Matthew Hoddie, “Institutionalizing Peace: Power Sharing and Post‐Civil War Conflict Management,” American Journal of Political Science 47, no. 2 (2003): 318–32.

26 Stephen J. Stedman, “Spoiler Problems in Peace Processes,” International security 22, no. 22 (1997): 5–53; Jacob Bercovitch, J. Theodore Anagnoson, and Donnette L. Wille, “Some Conceptual Issues and Empirical Trends in the Study of Successful Mediation in International Relations,” Journal of Peace Research 28, no. 1 (1991): 7–17; Desirée Nilsson, “Partial Peace: Rebel Groups Inside and Outside of Civil War Settlements,” Journal of Peace Research 45, no. 4 (2008): 479–95.

27 Peter Wallensteen, Understanding Conflict Resolution: War, Peace and the Global System (London: SAGE Publications, 2007).

28 Johan Galtung, “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research,” Journal of Peace Research 6, no. 3 (1969): 167–91.

29 Ole Waever and Mona Kanwal Sheikh, “Global Conflict and Security,” in The Encyclopedia of Global Studies, ed. Mark Juergensmeyer and Helmut Anheier (Sage Publications, 2012), 645–53.

30 Thomas Hegghammer, “The Rise of Muslim Foreign Fighters. Islam and the Globalization of Jihad,” International Security 35, no. 3 (2011): 53–94; Lia Brynjar “Jihadism in the Arab World after 2011: Explaining its Expansion,” Middle East Policy 23, no. 4 (2016): 74–91.

31 Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Expanding Jihad – How Islamic State and Al-Qaeda find New Battlefields (Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies, 2017).

32 See earlier work on worldview analysis developed by Juergenmeyer and Sheikh (2013). Worldview analysis represents an insider-oriented attempt to understand the reality of a particular worldview: its social, ethical, political, and spiritual aspects; and how they come together into a coherent whole.

33 International conflicts focus on involvement of more than one country. Macro-level does not imply “global’ i.e. that it is everywhere, or the level above international, but includes multiple-level of actors, spread across more than one region.

34 Citation from Randall Collins, Violence: A Micro-Sociological Theory (Princeton University Press, 2008) referred to in Ole Waever and Isabel Bramsen, “Introduction: Revitalizing Conflict Studies, in Resolving International Conflict: Dynamics of Escalation, Continuation and Transformation, ed. Isabel Bramsen, Poul Poder, and Ole Waever (Routledge, 2019): 20. “The question of who generates constellations is different. Like regional security complexes, constellations are generated by the interdependent securitizations of a variety of entities, but do not require that the actors recognize this larger structure.” Barry Buzan and Ole Waever, “Macrosecuritization and Security Constellations: Reconsidering Scale in Securitization Theory,” Review of International Studies 35, no. 2 (2009): 268.

35 Ole Waever and Isabel Bramsen, “Introduction: Revitalizing Conflict Studies, in Resolving International Conflict: Dynamics of Escalation, Continuation and Transformation, ed. Isabel Bramsen, Poul Poder, and Ole Waever (Routledge, 2019): 20.

36 Antony Black, The History of Islamic Political Thought: From the Prophet to the Present, 2nd ed. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011); Hugh Kennedy, Caliphate: The History of an Idea (Pelican, Basic Books, 2016); Mona Kanwal Sheikh, “Baya, hijra and the khilafat: Globalizing Ideas of Jihadist Theology” (forthcoming).

37 Dean Pruitt, Jeffrey Rubin, and Sung Hee Kimt, Social Conflict: Escalation, Stale-mate, and Settlement, 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003).

38 Anthropologists have stressed the role played by social norms in shaping the emotion categories of different societies. These accounts raise questions about the extent to which an emotional repertoire is malleable; if we see that emotions transform with the learning of social norms and ethical standards, then a fruitful area for conflict studies could be to look for ways to transform the emotional climate that enables/disables securitization to occur and conflicts to “transnationalize.” Emma Hutchinson and Roland Bleiker, “Theorizing Emotion in World Politics,” International Theory 6, no. 3 (2014): 491–514.