?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Does social cohesion explain variation in violence within divided cities? In line with insights drawn from the ethnic politics, criminology and urban geography literature we suggest that explaining variation in intergroup violence is not possible by relying on motivational elements alone, and attention to social cohesion is required as well. While cohesion can facilitate collective action that aids violent mobilization, it can also strengthen social order that contributes to the group’s capability to control and prevent unrest. We test these relationships using an application of a latent variable model to an integration of survey results, crime data and expert-coded data in order to measure cohesion in East Jerusalem neighborhoods. We then analyze its impact on riots using three original geolocated datasets recording violence in the neighborhoods between the years 2013 and 2015. Our results reveal that even with controls for economic and political determinants of violence, as well as for spatial clustering and temporal explanations, neighborhood-level social cohesion is a robust explanatory variable that negatively correlates with riots.

I asked one of the students: Why are you so angry? He replied: There everything is white, and here everything is black. (Baha Nabata, Shuafat Refugee Camp)Footnote1

Like many other cities, Jerusalem hosts diverse ethnic, religious and social groups,Footnote2 and neighborhoods serve as one important sociogeographical framework in which groups organize to achieve common interests.Footnote3 Thus, the analysis of intergroup violence in urban settings, and specifically in the case of Jerusalem, requires close attention to neighborhood characteristics. With this in mind, we ask why certain neighborhoods within ethnically divided cities exhibit higher rates of riots. We have many theories of violence, but only a few explain internal variation in violence within cities. We propose a new perspective that emphasizes social cohesion, in order to explain variation in the spatial manifestation of riots.

The stark segregation and inequality dividing Jews and Palestinians in Jerusalem lends much support for the “black and white” perspective articulated above by Baha Nabata’s student from Shuafat refugee camp, located in northeast Jerusalem. Being a Palestinian in one of the world’s most contested urban spaces almost automatically renders individuals and groups to a reality of “second-class residency” and oppression. Thus, a Palestinian is likely to be stopped for security checks regardless of their political orientation, and constraints on urban development and education impact both impoverished and affluent communities. Given this reality, in which disadvantage and oppression are almost “held constant” for most Palestinians vis-à-vis their broader urban environment, one may expect contention and violence to be distributed uniformly across the city’s Palestinian segments. Nonetheless, not all neighborhoods endure similar rates of violence. Thus, hereinafter we argue that social cohesion is a key factor explaining violence variation in ethnically divided cities.

Previous work has pointed out the importance of ethnic relations,Footnote4 as well as economic disparitiesFootnote5 in the outbreak of riots. Nonetheless, considering these factors in the case of Jerusalem portrays a puzzling picture by which neighborhoods enduring similar challenges often exhibit diverging rates of violence. In order to address this puzzle, we go beyond the analysis of well-established economic and political motivations, considering the regulating role of social cohesion within neighborhoods. We offer that social cohesion in neighborhoods enables the enforcement of order within communities and ethnic groups, and we expect such within-group order to influence intergroup violence and riots more specifically. This expectation is rooted in previous work linking group norms, which stand at the base of social cohesion and intergroup violence.Footnote6 We predict that a cohesive group will police its members effectively in order to prevent violence that can spiral out of control. In what follows we examine whether social cohesion curbs or promotes riots within ethnically homogenous neighborhoods of an ethnically divided city, and whether the influence of economic or ethnic tensions on the outbreak of violence vary in line with neighborhoods’ social cohesion.

Many recent studies on contentious politics in Jerusalem are situated in political geography. These include studies that explained riots from a purely spatial perspective with a space syntax network analysis.Footnote7 They were complemented by new work, which focused on explaining violence as the product of the geographic differences in economic disadvantage, ethnic friction or an integration of both of these.Footnote8 Recent work complemented these studies, increasingly emphasizing the role of civil society and social structure with a focus on communal institutions and feelings of belonging.Footnote9 We build on these using a quantitative and spatial analysis of riots in East Jerusalem. Similar to these studies, we consider and evaluate the role of economic and ethnic motivation for violence, as well as spatial interdependence, but our main focus is on the moderating role of social cohesion. This is based on literature from criminology and sociology and the latter studies on the social fabric of East Jerusalem neighborhoods. Our measurement of cohesion uses unique neighborhood-level proxies that capture essential components like fragmentation, interpersonal trust, social order, feelings of belonging and local institutions. The latter two were investigated by the studies we mentioned above but were not conceptualized as part of an underlying construct like social cohesion or quantitatively evaluated as related to the spatial dispersion of violence.

Our approach also rests on previous work in the social sciences that emphasized the importance of social cohesion to collective behavior and intergroup relations and treated it as a multidimensional concept that relates to the strength of group ties and encompasses the level of intragroup trust, dense social relations, strong civic participation, open inclusion to the group and mutual social support in it.Footnote10 Particularly, we adopt Chan, Ho-Pong and Chan’sFootnote11 approach that defined social cohesion as “a state of affairs concerning both the vertical and the horizontal interactions among members of society as characterized by a set of attitudes and norms that includes trust, a sense of belonging and the willingness to participate and help, as well as their behavioral manifestations.” We translate this definition to a multidimensional, latent variable that we use to measure cohesion in the neighborhoods of East Jerusalem. During our data collection, we made sure to translate every facet to an appropriate matching operational variable that captures one of these behavioral manifestations, so we can identify the underlying social cohesion.

We analyze daily variation of Palestinian riots in East Jerusalem, focusing on the period between January 2013 and December 2015, and find that neighborhood social cohesion plays a key role in constraining local riots. The results hold even when controlling for alternative explanations relating to the economic and political determinants of violence, as well as for spatial clustering and temporal explanations. The results also remain the same after the exclusion of the facets of social cohesion that are endogenous to violence, such as crime and negative migration. The article is divided into seven sections. The introduction, “Violence in Ethnically Divided Cities,” develops several key theoretical arguments and discusses the main hypotheses. Next, we provide a brief historical outline of Jerusalem, situating it within our theoretical framework. “Data and Methodology” introduces the main dataset a geolocated dataset based on police records from East Jerusalem alongside a description of our main measurements. In “Analysis” we report the main analyses, followed by “Robustness Check” in which we test the robustness of our results using two alternative original datasets of intergroup violence in Jerusalem and varied models. The conclusion addresses key findings alongside additional avenues for future work regarding urban intergroup violence.

Violence in Ethnically Divided Cities

Intergroup violence has had a significant impact on the fabric of life in ethnically, religiously and culturally fragmented cities, including: Belfast,Footnote12 Karachi,Footnote13 Nairobi,Footnote14 BagdadFootnote15 and Jerusalem.Footnote16 Yet many studies of ethnic conflict and civil war do not decipher between urban and rural violence, which often differ in their intensity, implementation and motivation.Footnote17 Similarly, social cohesion in urban and rural communities was found to be substantially distinct.Footnote18 Additionally, whereas previous cross-national studies of violence exploit variation in economic inequality,Footnote19 political representationFootnote20 and ethnic friction,Footnote21 doing so in urban contexts may not be suitable if variation is more subtle. Thus, one may wonder to what extent existing theoretical perspectives regarding the outbreak of violence in ethnic conflicts suffice to explain the determinants of urban violence.

In light of the qualitative difference between rural and urban violence, we propose a new framework that builds on common conventions from the ethnic politics literature dovetailed with insights from the study of urban crime and delinquency. We argue that despite the intuitive importance of broad economic and political motivations existing in all neighborhoods of ethnically divided cities such as Jerusalem, communal norms and incentives often play an important regulatory role in the emergence of violence.Footnote22 Hence, hereinafter we argue that understanding urban violence requires awareness of social cohesion, which is associated with communal norms that in turn constitute significant variation in the motivation and ability of neighborhood residents to instigate or participate in violent events because of its effect on opposition to conflictual politics.Footnote23 In the remainder of this section, we discuss a series of hypotheses that together offer a more nuanced outlook on the antecedents of violence in ethnically divided cities.

Social Cohesion and Violence

Empirical emphases on the political and economic determinants of riots highlight neighborhood characteristics that may ignite intergroup violence, but they do not necessarily offer a glance into social processes by which communities gain the ability to regulate collective behavior and promote or curb the spread of violence. Although reasoning and motivations for intergroup violence are abundant within ethnically divided cities, not all neighborhoods display similar rates of violence. Therefore, attention must be directed not only to neighborhood motivations (i.e. residents’ collective motivations), but also to social cohesion, which may explain why neighborhoods enduring similar difficulties display diverging rates of riots. Although economic difficulty and ethnic tensions are indeed powerful predictors of riots, we would like to stress the theoretical importance of social cohesion as an explanation for violence that influences it independently of explanation rooted in greed and grievance.

Cohesion is a bundle of interrelated social phenomenon, like communal norms, informal institutions and daily social relations. We adopt the influential framework suggested by Chan, Ho-Pong and ChanFootnote24 for operationalizing social cohesion. They emphasized the need to use proxies for cohesion such as interpersonal trust, the vibrancy of civil society, the shared sense of belonging and identity, absence of internal cleavages and adherence to social leadership. This proposal for operationalization is similar to the highly influential conceptualization by Kearns and ForrestFootnote25 of neighborhood-level social cohesion, which referred to five dimensions: civic culture, social order and control, social solidarity, social capital and place attachment. But we are particularly interested in the role of social order in cohesion. Criminologists have long indicated that the ability of communities to acknowledge common values and sustain social control has a momentous effect on local crime rates. Control often requires residents’ active participation in eradicating deviant subcultures and intervening in cases that could escalate and result in turmoil or violence.Footnote26 In the criminology literature, it is offered that such control can be maintained in many ways, some of which include sustaining a presence of authoritative figures in public spaces, or facilitating neighborhood patrols aimed to prevent petty crimes such as robberies.

Although maintenance of social order may be an active effort of individuals, neighborhood regulatory capabilities are often sustained by informal institutions, which in a differing context have been defined by Helmke and LevitskyFootnote27 as “socially shared rules, usually unwritten, that are created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels.” Preserving control through active practices or informal institutions generates what is considered in the criminological literature to be socially organized neighborhoods, whereas failing to do so will result in socially disorganized neighborhoods.Footnote28 Violence can also be shaped by the proximate concept of social discipline, but this will require an inherently coercive process, while social cohesion includes use of social capital to achieve voluntary cooperation from group members. Thus, in most cases, informal leadership lacks strong coercive capabilities, particularly on a level that will deter group members that are not deterred by the far stronger coercive capabilities of the state. Group leaders can alternatively use the existing social order and their social capital, the essential components of social cohesion, to shape the violence behavior of members. Social cohesion offers a noncoercive but sustainable intragroup mechanism for the regulation of violence that is an alternative to social discipline.

In light of the above, we differentiate between socially cohesive and incohesive neighborhoods. Whereas the former neighborhoods manage to prevent within-group crime and disorder through active social engagement and informal communal institutions, the latter neighborhoods fail to do so in light of their limited communal engagement. However, the impact of cohesion goes well beyond within-neighborhood crime (i.e., robberies, gang violence and petty crimes), and we propose to consider social cohesion as a key determinant of intergroup violence, and more specifically riots in ethnically divided cities.

In a seminal contribution regarding intergroup conflict and cooperation, Fearon and LaitinFootnote29 theorize and provide qualitative evidence for the ways in which groups, communities or neighborhoods can control members and impede interethnic clashes for a better public or group good. Since in states of conflict, group informal institutions often provide considerable services either instead of or alongside the state, compliance with group “agendas” is beneficial, if not compulsory for individuals.Footnote30 The group is likely to reject violence due to the danger of governmental or out-group retaliation. The threat of violence spiraling out of control and causing significant disruption will lead the group to enforce restraint, and it can do so more effectively in a socially ordered neighborhood, in which the in-group leadership will have more authority and tools of control. The group’s informal and formal leaders strive to protect their status, which necessitates a working relationship with the government. By using their power in the socially organized neighborhood they can avoid both group-wide and personal sanctions that might follow in response to intergroup violence. In a neighborhood that lacks cohesion, it will be harder to restrain ethnic hatred and prevent escalation by extremists in favor of group-wide interests. Such in-group policing is an essential part of the social cohesion that characterizes cohesive neighborhoods. Thus, it follows that:

H1: Socially cohesive neighborhoods will experience less riots.

Nonetheless, neighborhood social cohesion may influence intergroup violence and riots in an opposite manner. Influential actors or powerful informal institutions may alternatively promote communal behavior intended to contravene with public order,Footnote31 especially in divided cities where contention with other groups or dissatisfaction from institutions may be pronounced. Following this notion, social cohesion should be thought of in broader contexts, as its impact on violence may differ according to a group’s relations with its neighbors, municipality representatives and the general public. Thus, we consider a competing proposition regarding the regulating role of social cohesion in the emergence of intergroup violence, proposing that cohesive neighborhoods will provide better “facilities” for potential perpetrators to contravene with public order sustained by countergroup members. This is especially true in the case of riots, which are a particularly collective task that is heavily reliant on group dynamics and interpersonal participation and coordination. Cohesiveness may therefore actually strengthen violent mobilization by supporting the group’s ability to organize effectively. Accordingly, we propose that neighborhood social cohesion will be linked with higher rates of intergroup violence, and more specifically riots. The seminal contribution by GurrFootnote32 has also promoted this view, arguing out of a cross-national comparison that cohesion is needed for violent mobilization. Thus:

H2: Socially organized neighborhoods will experience more riots.

Alternative Explanations

Ethnic Friction

As GurrFootnote33 argued, collective violent protest is influenced deeply by the group’s identity. Multiple analyses of ethnic conflicts have emphasized the major impact of ethnic exclusion on the emergence of intergroup violence.Footnote34 Although such theoretical frameworks were often developed in a cross-national context, exclusion from power, and relations with countergroup members are important in urban settings, since cities encompass opportunities for intergroup contact and exclusion due to their limited geographical space as well as condensed political and social frameworks. The increased ethnic interaction will lead to friction and existential fear that is likely to cause conflict that could be pronounced in rioting.Footnote35 Thus, in ethnically divided cities, friction often exacerbates animosity between groups.

Even if ethnic grievances and motivations are salient among most residents of ethnically divided cities, the residential proximity between groups, and the geographically condensed nature of urban spaces calls for an examination of the role that ethnic frictions plays in the outbreak of urban intergroup violence. More specifically, attention should be allocated to the diverging magnitude and frequency of interethnic interactions within different neighborhoods of ethnically divided cities, as such variation, even if it is rather subtle, may account for the spatial dispersion of intergroup violence.

H3: Ethnic friction will lead neighborhoods to experience more riots.

Economic Disadvantage

It is well established that economic growth and inequalities affect the propensity of individuals and groups to immerse themselves in, or express support for, violent action. Poverty and perceived inequality highly influence the opportunity costs, incentives and motivations of participating in, or supporting, any form of violence, ranging from organized insurgency to sporadic rioting.Footnote36 In a similar manner to ethnic friction, economic disadvantage in divided societies is often salient between groups; however, its variation within groups may be more subtle. Nonetheless, it is important to consider the potential influence of economic factors, as impoverished populations may be more likely to perpetrate violence and riots.

H4: Economic disadvantage will lead neighborhoods to experience more riots.

If so, ethnic friction and economic inequality within neighborhoods may induce motivations for intergroup violence. However, given our emphasis on social cohesion, we argue that cohesion should be examined as a filter, channeling diverging ethnic and economic catalysts into diverse manifestations of action and inaction. It follows that neighborhood social cohesion should impact not only violent outcomes as proposed above, but also the manner by which local motivations relate to violent outcomes. Therefore, we offer that:

H5a: Social cohesion moderates the relations between economic motivations and violence.

H5b: Social cohesion moderates the relations between ethnic motivations and violence.

Spatial and Temporal Dependence

Recent advances have analyzed the diffusion and contagion of violence across geographical locations, demonstrating its spread across countries as a factor of displacement, similar cultural and political attributes, sufficient infrastructure and lack of states’ capacities to contain it.Footnote37 This evidence accentuates the need to consider space in the analysis of urban violence, as countries, cities and neighborhoods may very well be affected, not only by endogenous social capacities and motivations, but also by exogenous occurrences. Thus, in dense urban environments where information flows quickly, a riot in one neighborhood may instigate confrontations in adjacent locations.

However, dependence should be thought of not only in terms of space, but also in terms of time, as violent events at timet−1 often induce the probability of future violence within specific locations. Additionally, previous riots can enhance animosity and aspirations for revenge, fueling an ongoing cycle of violence.Footnote38 Therefore, it is important to consider neighborhoods’ immediate histories, and their impact on local propensities for riots.

H6a: Riots that occur in a neighborhood will raise the likelihood of repeated rioting in proximate neighborhoods.

H6b: Riots that occur in a neighborhood will raise the likelihood of repeated rioting in the following days.

Jerusalem: A Divided City

Why East Jerusalem?

To examine the hypotheses above, we turn to an empirical analysis of violence in East Jerusalem between 2013 and 2015. As a focal point in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, Jerusalem is a city in which divides between Israelis and Palestinians are potent and contested. Unlike most Palestinians residing under Israeli rule, the majority of East Jerusalemites do not hold Israeli citizenship, and their Palestinian affinity and identity is quite dominant. Thus, the case of Jerusalem provides a fertile ground for inquiries accentuating both local–communal as well as ethnic and economic factors separating two groups in conflict.Footnote39

Since its occupation in 1967, East Jerusalem has gradually transformed from an array of local villages to an overpopulated and derelict cluster of neighborhoods. This cluster, attached to Jerusalem by Israeli national law, differs completely from its western counterpart. The stark difference between East and West “Jerusalems” is manifested in many spheres, including urban planning, education, infrastructure, transportation, commerce and employment. While annexing East Jerusalem was framed by the Israeli government as an unprecedented historical act uniting the long-divided city, the practical outcome is best described as a case of “separate and unequal.”Footnote40

Poverty is a common phenomenon across all East Jerusalem neighborhoods, and 77 percent of Palestinian families are considered poor by Israeli standards. On the whole, economic standings in East Jerusalem are categorically lower than West Jerusalem. This is evident, for example, in the main occupations of Palestinian residents of the city, which include commerce, construction, services and education. The vast economic differences between East and West Jerusalem have led many Palestinians to commute to the western part of the city in search of economic opportunities.Footnote41

East Jerusalemites’ legal status of residency rather than citizenship granted following the 1967 occupation of the city is accompanied by a unique set of rights and obligations. Thus, individuals and groups benefit from Israeli social security, healthcare, and municipal voting rights.Footnote42 Yet voting is one dimension in which the uniform Palestinian contention toward Israeli institutions is expressed, as across all neighborhoods, turnout has consistently been close to 0 percent ever since suffrage was granted.Footnote43

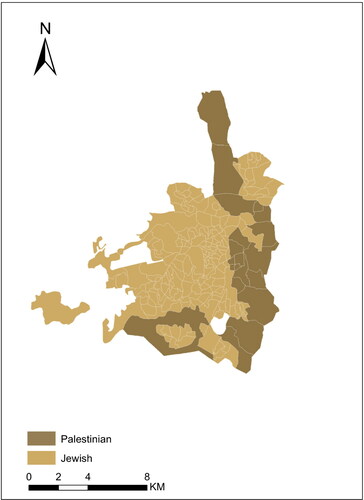

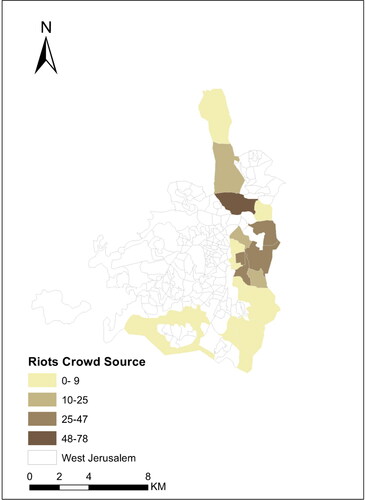

Jerusalem’s ethnic divisions and inequalities are so stark that some consider it as comprising of practically two different cities. This is most evident in the extreme residential segregation depicted in . The significant intergroup separation anchored in residential patterns, social affiliations and political alignments alongside the prevalent and significant economic and institutional interdependence of Palestinians and Israeli Jews characterizes Jerusalem as a divided yet intertwined city.Footnote44 These sociogeographical attributes of Jerusalem call for some scrutiny in our analysis, as the structural differences and unbalanced power relations between Palestinians and Israeli Jews require us to limit ourselves to the analysis of one faction at a time. That is because, for example, Israeli violence is typically implemented by police officers and framed as a preventive form of action, while Palestinian violence is often unorganized and framed as a form of resistance. Therefore, below we emphasize riots occurring in East Jerusalem, which are perceived by some residents of the city as a form of resistance and by others as violent attempts to disrupt Israeli order.

Why Riots?

Riots have been the most common form of Palestinian violence and resistance manifested in Jerusalem during recent years. Given the extreme repression led by Israeli security forces, East Jerusalemites’ motivations and abilities to coordinate and implement more organized lethal violence has been hindered. Even in the Second Intifada (“uprising” in Arabic), Palestinian Jerusalemites were mainly involved in the logistic side of coordination, rather than implementation of high-intensity violence.Footnote45 Thus, riots are, and have always been, one main form of violence that is common in Jerusalem and implemented by local residents. We use the concept “riots” because it is commonly used in the literature and in day-to-day usage. By riots we refer to unarmed collective violence by civilians, as defined by Kadivar and Ketchley.Footnote46 They define it as

episodes of social interaction that immediately inflict physical damage on persons and/or objects (‘damage’ includes forcible seizure of persons or objects over restraint or resistance) without the use of firearms or explosives, involve at least two unarmed civilian perpetrators of damage, and result at least in part from coordination among unarmed civilians who perform the damaging acts.

This category is distinct from nonviolent resistance on the one hand, and armed insurgency on the other; and it is used as a synonym to riots, with specific examples referring to the use of stone throwing and Molotov cocktails. By the use of the term riots we do not pass any moral judgment on the civilians that participated in them, since our interest in this article is purely empirical and as Kadivar and KetchleyFootnote47 showed, unarmed collective violence is frequently used by democratic movements. During the coding process, we carefully processed the police reports and only included two-sided events, in which Palestinian residents were attacking Jewish property, civilians or police forces. This coding process and definition meant we only looked at riots that are intergroup, collective acts of violence but also still included many events, since riots are very commonly used in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

Data and Methodology

Data

To test the hypotheses above, we use a geolocated data set of Palestinian riots, based on Israeli police records from the years 2013 to 2015. While police records provide an ingrained typology of almost 200 types of events spanning from murder and sexual assaults to extortion and scalping, we concentrate on stone and Molotov cocktail throwing, which are central to riots in Jerusalem. Additionally, we utilize police records in order to construct our main independent variable, as discussed in “Social Cohesion.” Further explanations regarding the use of police data are provided in section A.1 of our online appendix.

Dependent Variable Riots

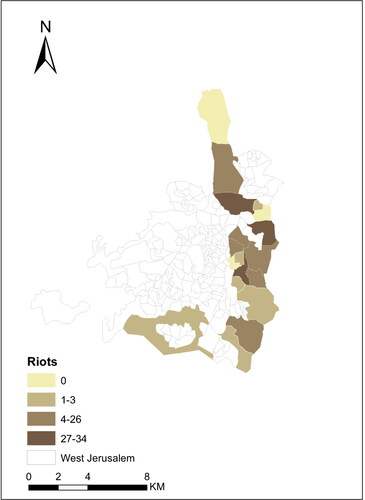

We consider reports of stone and Molotov cocktail throwing as indicators of riots. Since our raw police data detail disaggregated information regarding numerous suspects and victims of such occurrences, we aggregate all suspect and victim files of what we consider to be a unique event, according to the file numbers and riot locations, defining this aggregate as one riot. By so doing, we obtain a conservative measure of events that is adapted to appease concerns regarding overreporting. Additionally, we only consider reports that are mutually exclusive from other criminal offenses, in order to make sure that our measures capture ethnically charged violence, rather than local delinquents’ behavior. The data are completely anonymized (any identifying information was excluded by the police following a freedom of information request), and we then further aggregated them to the neighborhood level. Thus, it is impossible to reveal any damaging private information from the data. While policing is inherently coercive, the data are collected anyway as part of regular policing actions and not just for the purpose of this study. The collection of the data themselves did not involve further coercion, but rather was mostly based on observation based on officer’s field reports and victim complaints, not any further investigation. Only after it was collected by the police independently did we access and analyze it; therefore, we used preexisting data and no further coercion was used for the sake of this study. Because these data are our most reliable and fine- grained way to study riots, a highly important phenomenon, we believe it is justified to use the data despite any ethical issues with the policing itself. Our data include 193 riots, which are depicted according to their spatial dispersion in . further informs that the maximum number of riots during any given day in Jerusalem is three, while the daily mean of events is rather low (M = .009 and SD = .101). Silwan, which has experienced thirty-four riots between 2013 and 2015, is the most eventful neighborhood according to police records, whereas the adjacent quarters of Jerusalem’s old city as well as Anata and Kfar Aqab are the most eventless locations in Jerusalem (zero events).

Table 1. Summary statistics of the main variables.

Independent Variables

Social Cohesion

Social cohesion is a difficult variable to operationalize because of its multidimensionality, broad scope and latent nature. We rely on the large body of literature that focused on measurement of cohesiveness in order to construct a latent variable to capture our main independent variable.Footnote48 This variable is constructed with multiple different proxies that we created from different data sources. As we will show, these proxies were successfully used by researchers in the past. They also collectively fit the measurement framework offered by Chan, Ho-Pong and Chan,Footnote49 Botterman, Hooghe and Reeskens,Footnote50 and Kearns and ForrestFootnote51 by measuring the different facets of cohesion that they suggested are important, including social participation and voluntarism, general trust, crime and order, sense of belonging and social fractionalization. The variables that represent these dimensions are, accordingly, the amount of local organizations, surveyed interpersonal trust, police crime data, negative migration volumes and the weighted number of traditional family groups (hamulot) in the neighborhood. We used confirmatory factor analysis of these indicators, after they were standardized and weighted per population, based on principal axis factoring in order to validate and construct the combined latent variable, appearing in the results section. We detail below these proxies and the theoretical constructs they represent, and they are summarized in . Every single variable described below is just a proxy that captures a facet of social cohesion; we aim to capture the shared latent variable between these, which is most likely social cohesion, using the factor analysis.

Table 2. Summary statistics of proxies for cohesion.

Local Organizations

The vibrancy of the civil society, social participation and voluntarism form a key facet of social cohesion.Footnote52 We measure this facet using expert coded data on the number of local organizations extracted from a report on the civil society of the neighborhoods in our sample obtained from the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research (JIPR). These organizations are operated locally by the neighborhood’s residents and are only run in each neighborhood. In the literature on social cohesion, such voluntary organizations have been consistently associated with social cohesion, and particularly the ability of the group to guide social norms.Footnote53 Societal organizations can moderate social norms in order to prevent riots, but they can also foster collective actions. Recent studies have found that their existence increases urban unrest.Footnote54 The general mean of local organizations is 5.47 with an SD of 2.637, as depicted in . The neighborhood with the most local organization is Silwan, with eleven organizations, and Bet Hanina is close with ten organizations. The neighborhoods with the lowest number of organizations are Bet Zafafa, Sur Bahar and Ras al-’Amud with three organizations.

Interpersonal Trust

Interpersonal trust has been described as the “constitutional element” and an “integral part” of social cohesion.Footnote55 Chan, Ho-Pong and ChanFootnote56 have argued that survey data about trust in fellow citizens should be used to measure this facet. We concur and use original data from a survey administered on a representative sample of residents of every East Jerusalem neighborhood. The respondents were asked if they agree that people in the neighborhood can be trusted. Their answer formed a scale of the social capital in the neighborhood. Sur Bahar and New Anata have the highest share of residents that trust others with 71.4 percent and 70 percent, respectively. Wadi Al-Joz and Sheih Jarrah have the lowest share of interpersonal trust with 15 percent. The general mean of the weighted scale of interpersonal trust is 2.05 with an SD of 0.6, as depicted in . Higher levels of intergroup trust are a key indicator of high social cohesion, and particularly the social capital element of it; neighborhood leadership can use this social capital to restrain demographics that would like to riot.

Kawachi, Kennedy, and WilkinsonFootnote57 argue that crime could be thought of not only as an outcome of social capacities, but rather as an indicator of social organization. In a study linking crime and social organization, they conclude that “…crime is the mirror of the quality of social relationships among citizens.” Put differently, it is proposed that crime can be used to assess social organization, or in our case cohesion, and that the presence of crime within specific locations may eventually lead to declining social capital and social organization. Building on Kawachi, Kennedy, and Wilkinson,Footnote58 and other criminological advances that have linked low crime rates with social cohesion,Footnote59 we calculate yearly rates of within-neighborhood crime, as a proxy for neighborhood social cohesion. Thus, we consider neighborhoods that experience delinquent behavior such as robbery, pickpocketing, car theft and drug dealing to be incohesive. We argue that this measure is highly indicative of social cohesion, as it is likely to assume that cohesion within Palestinian neighborhoods will not only result in fewer incidents of crime, but more importantly lead community members to resolve many disputes independently without involving Israeli authorities. Additionally, while survey data can reveal partial dimensions of social cohesion, crime rates provide a broader perspective regarding neighborhood cohesion. Hence, there are numerous reasons to utilize crime rates as indicators of social cohesion. According to police records, the neighborhoods with the least crime in Jerusalem are Um Tuba and Anata, which experienced twoFootnote60 and sevenFootnote61 criminal events, respectively. In contrary, the Muslim Quarter and Beit Hanina appear to be the most incohesive neighborhoods, experiencing 180Footnote62 and 168Footnote63 yearly criminal events, respectively. The general mean of yearly criminal events is 65.8 with an SD of 45.8, as depicted in . It is possible that this variable in particular is endogenous to the level of riots, and so we also considered a model that does not include it, with identical results.

Negative Migration

An essential dimension of social cohesion is the sense of belonging to the community.Footnote64 In a seminal study on urban social cohesion, Kearns and ForrestFootnote65 have argued that it includes a common identification with a specific geographic unit that encompasses socialization into the loci and the absence of social exclusion, often directing the behavior and attitudes of the residents. This dimension has been described as the hardest to operationalize.Footnote66 We attempt to nevertheless integrate this dimension to our latent variable by using data on the level of negative migration from the neighborhood. We argue that in a cohesive community there will be fewer residents leaving it because their identification with it will block them. The sense of belonging, together with social inclusion, can be powerful enough to lower the level of negative migration, despite challenges like economic hardship, because the residents will not accept life in other places or at least prefer to stay in the community to which they belong. We measure negative migration using data from the yearly statistical reports of the JIPR for 2013 through 2015. The lowest level of negative migration was in Sur Bahar in 2013, when 0.9 percent of the population left. The highest level was in Shu’afat in 2014, when 32.8 percent of the population left. The general mean of yearly negative migration share is 0.04773 with an SD of 0.0476, as depicted in . It is possible that this variable in particular is endogenous to the level of riots, and so we also considered a model that does not include it, with identical results.

Hamulot

An additional new and original proxy for social cohesion is the indicator developed by Arnon, McAlexander, and RubinFootnote67 in a recent study. They measure historical cohesion in Palestinian villages by focusing on the hamula, the primary social group that organized political and social activity among the Palestinian and other societies. These are extended groups connected by family ties, and inflation in their amount signals fractionalization and cleavages within the group. These will pose a significant challenge for social cohesion and, consequently, for collective action, as Arnon, McAlexander, and RubinFootnote68 showed. We measure the amount of hamulas by extracting it from the neighborhood report series of the JIPR. The highest amount of hamulas is in Wadi Al-Joz with thirty-six, and the lowest is in the Shu’afat refugee camp and Abu Thor with none recorded. The general mean of the amount of hamulas is 9.307 with an SD of 0.809, as depicted in . Strong social structure and the absence of intragroup cleavages means that the group will be able to coordinate and act collectively better, and that the group’s leadership has more sway on group members using these structures. This thus means that violence will be regulated more effectively.

Economic Disadvantage

In order to capture economic disadvantage within East Jerusalem neighborhoods, we utilize the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS) data regarding municipal city tax–paying patterns. As Jerusalem municipality provides economically disadvantaged residents with differentiated discounts for city taxes, we use neighborhood discount rates to assess variation in local socioeconomic standing. As depicted in , average neighborhood tax discounts range between 20 and 40 percent, with a mean of 30.6 percent and an SD of 5.2 percent. Apart from the old city quarters, Beit Zafafa is the wealthiest neighborhood, receiving only 20 percent tax discounts, as opposed to Issawiya and At-Tur, which have received as much as 42 percent and 39 percent tax discounts.

This measurement is suitable for a number of reasons. First, Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem utilize taxes to secure their residential status and prevent potential residency denouncement initiatives by Israeli authorities. This explains the relatively surprising residential tax collection average rate in East Jerusalem (77.5 percent) as many Palestinians have strong incentives to pay their taxes in order to secure legal status. Additionally, tax discounts are based on yearly self-reported household income, which is examined by Jerusalem municipality, providing a reliable measure of average neighborhood-level socioeconomic standings. Thus, we incorporate average yearly discount percentages for all neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, and, as presented in , higher discount rates indicate higher economic disadvantage.

Ethnic Friction

Despite the stark residential segregation between Jews and Palestinians in Jerusalem, and although neighborhoods are extremely homogenous, embedded settlements established by religious Jews have begun to diversify local residential patterns. These settlements usually comprise several apartments, which are occupied by ideologically motivated religious Jews, who are secured by private security forces as well as police units. This local phenomenon has begun to ignite much friction between local communities, settlers and police forces.Footnote69 However, since not all neighborhoods have been targeted by such initiatives of embedded settlements, we control for potential ethnic friction with a binary variable denoting whether an embedded settlement exists within specific neighborhoods.Footnote70 Sheikh Jarrah and At-Turare are two of the eight neighborhoods in which large, embedded settlements have been established and developed, whereas neighborhoods such as Shuafat and Beit-Hanina along another ten neighborhoods in East Jerusalem have yet to be penetrated by settlers.

Spatiotemporal Explanations

By utilizing a spatial autoregressive model (SAR) described in the subsequent section and including previous day riots within neighborhoods in our model, we assess explanations based on spatiotemporal factors that may explain part of the variation in riots across East Jerusalem neighborhoods. Last, in order to measure the ongoing impact of unique violent events, we consider two seminal events in Jerusalem during the period under analysis: the murder of Mohammed Abu-Khdeir on 2 July 2014, and major upheavals on al-Haram ash-Sˇarif during October 2015. Although quite different, both events have ignited much tension and intergroup dissent in Jerusalem.Footnote71 Thus, an additional temporal variable (Major Events) was constructed in which every day following the murder of Mohammed Abu-Khdeir was given a value of 1 (438 days), and values of 2 were given to all days following the upheavals in al-Haram ash-Sˇarif (110 days).Footnote72

Control Variables

In addition to the measures described above, we control for neighborhood population size available from public ICBS data.Footnote73 Controlling for population size is important, as maintaining neighborhood-level cohesion is likely to depend on personal connections and reputational motivations, which are more difficult to maintain as neighborhood population size increases. Moreover, in large neighborhoods, individuals may see little risk in joining riots because disappearing into a large crowd is a relatively easy task. Last, the larger a neighborhood’s population, the deeper its pool of potential perpetrators becomes. Therefore, controlling for neighborhood population size is crucial when examining low-intensity violence.Footnote74 The smallest neighborhoods in East Jerusalem are the Armenian quarter and Bab-a-Zahara, in which reside 2,260 and 2,300 residents, respectively, while in Beit-Hanina, the largest neighborhood in East Jerusalem, 38,810 residents reside. More broadly, the average neighborhood size in East Jerusalem, as depicted in is 15,765.5 with an SD of 9479.7.

Analysis

Factor Analysis and Construction of the Latent Variable

The different proxies that assemble our index of social cohesion are diverse, come from different sources and measure different dimensions of social cohesion. This is likely to cause them to hold unique variation and weaken the correlation between them, even if they have a shared correlation that originates from the effect of the shared underlying latent cohesion. Yet the factor loadings are relatively large and are comparable to previous factor analysis of social cohesion proxies.Footnote75 The factor’s eigenvalue is 1.16, larger than 1 as demanded by Kaiser’s rule. The factor loading’s direction suits our expectation, indicating the latent variable for cohesion’s negative correlation with crime, negative migration and hamulas, and a positive correlation with local organizations and interpersonal trust. A summary of the results of the analysis appear in .

Table 3. Factor analysis on social cohesion indicators.

Model Specifications

The data are structured so the outcome variable, riots, is a panel variable that changes every day. This fits the dispersion of the riots over single days and allows us to capture their fluid nature, which changes and is shaped on a day-to-day basis. The variable for cohesion varies on a yearly basis. We first use an ordinary least squares (OLS) model with day and neighborhood random-effects and clustering of the errors by the neighborhood level. This fits our data, since the variables are clustered in the neighborhood level, and are meant to appease concerns of the error terms not being independently distributed. We then continue to our main model, which acknowledges the importance of spatial dependence in the analysis of violence. For this purpose we utilized a SAR model.Footnote76 As East Jerusalem neighborhoods are adjacent to each other and relatively clustered, and as information flows relatively fast via traditional and modern communications outlets, accounting for spatial dependence seems necessary in order to get a precise view of the dynamics of violence in East Jerusalem, and the way attributes of specific neighborhoods and their impacts on neighborhood intergroup violence influence the city as a whole. Thus, we implement a random effects SAR model. This model accounts for daily citywide spatial lags of our dependent variables, weighted by a spatial contiguity matrix. Our model (see EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) ) is specified such that Yit is a count of riots occurring in neighborhood i during day t. ρWyit is a spatially weighted count of events surrounding neighborhood i in day t. βXit represents the model’s independent and control variables, while μit represents the model’s random effects. Last, εit represents the models error terms.

(1)

(1)

Main Results

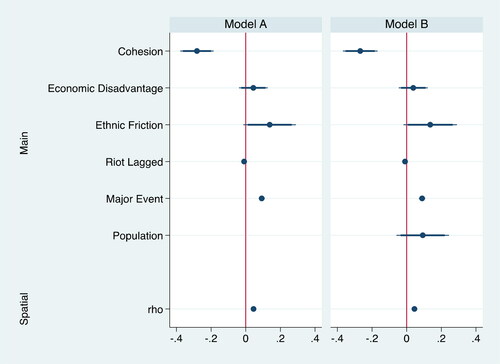

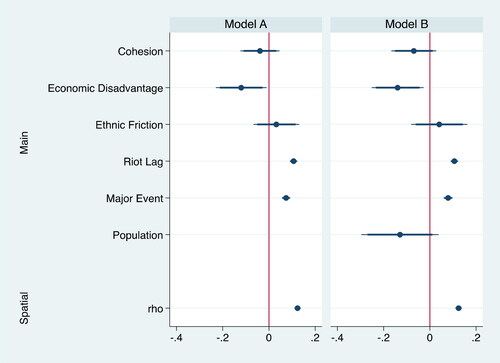

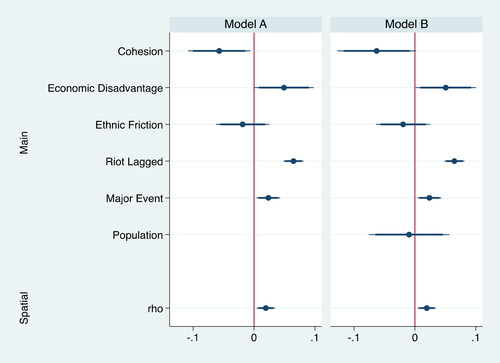

presents our main analysis of daily riots occurring in East Jerusalem between January 2013 and December 2015. On the right panel, model A presents the coefficients of the main SAR model, which accounts for four main theoretical explanations of urban violence, including spatial and temporal dependence. In model B of , we add the control variable for population, which we expect may impact our main results. presents the results of the random-effects OLS regression with the clustered standard errors.

Figure 3. Spatial autoregressive model (police data). In all models, thick lines denote significance levels of p < .05 and the thin extensions denote significance levels of p < .1.

Table 4. Random effects with clustered errors model (police data).

As evident in , cohesion, measured by a neighborhood-level set of proxies, is negatively correlated with riots (p < .05) even after controlling for multiple alternative explanations. That is, neighborhoods that received higher scores on the factor analysis for social cohesion are less likely to experience riots. As presented in , the correlation is robust also in the main SAR model, but when the control variable for population is added to the SAR model, the results were robust at a significant level of p < .1 (p = .056).Footnote77

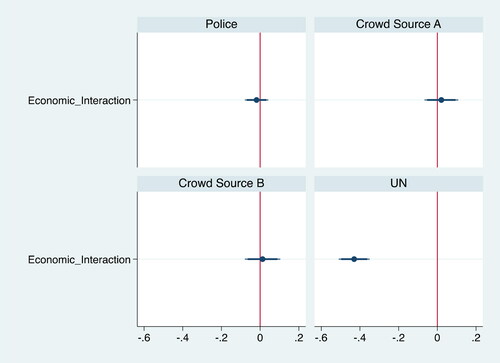

In addition, our main model lends support to the convention that economic disadvantage is associated with riots but we do not find significant influence of ethnic frictions. Thus, neighborhoods receiving higher tax discounts in light of their low self-reported income are more prone to riots. Additionally, our models offer that major events and the occurrence of riots in adjacent neighborhoods have a positive and statistically significant (p < .05) impact on neighborhood-level riots. Last, as evident in , the interaction of our cohesion and economic variable is not significantly correlated with neighborhood-level riots when controlling for alternative explanations.Footnote78 The model also lends support to the spatial autocorrelation of riots, but the lagged temporal variable does not have a significant effect in any of the models. The results thus lend support to H1, H4 and H6a but not to H2, H3, H5 and H6b.

Despite the consistent results of our model, and the robust relation between cohesion and riots, it is important to note several limitations. First, it may be that ethnic friction or economic disadvantage are endogenous to our indicators of social cohesion. In other words, perhaps economic standings impact neighborhood cohesion. To appease such concerns we regressed our latent variable for social cohesion on our ethnic and economic variables. The null results of such models are presented in section C.1 of our online appendix. This model might slightly relax concerns that ethnic friction and economic disadvantage are what stand in the base of the correlation observed in our main model above.

Second, it is possible that some of the proxies in the social cohesion indicator are related to riots in ways other than cohesion or are endogenous to riots. This concern is particularly severe with two variables: crime rates and negative migration. In order to appease such concerns, we constructed a latent variable that does not include these two components, but only the remaining three proxies. The results are consistent and significant when this alternative index is then used to measure social cohesion.

Also, the results above may be driven by reporting biases inherent to police data. In other words, perhaps Israeli police are on average more present in specific neighborhoods due to settler presence, security threats or daily local disorder. In such a case, our measures of riots may reflect police presence rather than the occurrence of actual events. As our data are compiled from police statistics regarding victims and (or) perpetrators rather than specific events, riots in which the police do not manage (or try) to arrest Palestinians will not be included in the records, raising further concerns regarding underreporting. However, as overreporting may also be a problem in light of the unbalanced power relations between police forces and Palestinians, we cannot rule out possibilities of exaggerated arrests and accusations by police officers. In light of such concerns, we now test our main model on two alternative data sources of riots in East Jerusalem during the same time period. These two alternative sources are gathered as part of two fundamentally different initiatives. Consistent results of the model will further enhance confidence in the evidence presented above.

Robustness Check

United Nations Data

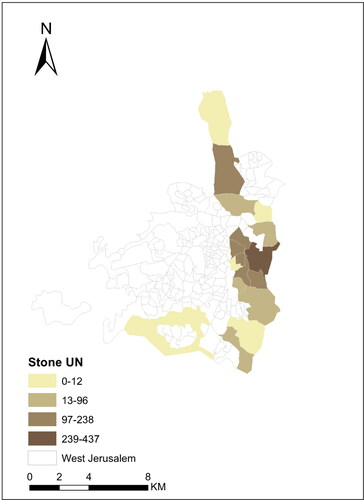

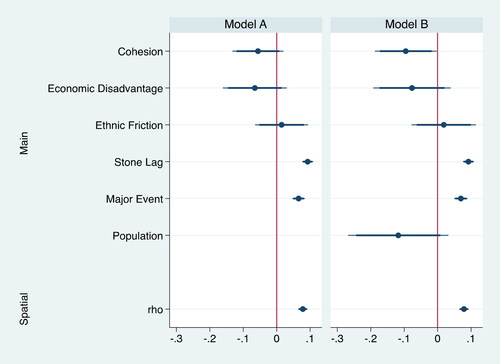

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in the occupied Palestinian territories has collected granular geolocated data regarding intergroup violence occurring in the West Bank and East Jerusalem in recent years. We use these data, emphasizing reports regarding stone throwing, as an alternative measurement of riots in East Jerusalem. As depicted in , the UN data include a significantly larger number of violent events (1,780 in total), yet the results presented in are still consistent with our main analyses. Thus, model A in points to the association (p < .05) between cohesion, economic disadvantage and riots. When adding our control variables, this relation is tempered, yet cohesion remains negatively correlated and statistically significant at a confidence level of p < .000.

Although this alternative source appeases many of the concerns described above regarding reporting biases imminent to police data, it is not free of limitations. Compiling this information source, OCHA relies on public information and media reports, which are further investigated, categorized and compiled into a granular database. Although this promises precise and reliable reports, it is likely that events that do not make it to the news will not appear in this source of information.

Crowd-Sourced Data

In order to overcome the potential bias described above, we proceed to test our model on yet another measurement of riots. This measurement is based on a crowd-sourced, Internet-based (Jewish) platform from which we achieved data that were manually coded into a granular geolocated database of all Palestinian violence occurring in Jerusalem between January 2013 and December 2015. For our purposes, we confine to two alternative measures: riots and stone throwing. Riots is a broader category that includes all stone-throwing events as well as other collective action against Israeli public order. Whereas our first, more inclusive, measure of riots includes 333 events, the second measure of stone throwing includes 255 events. The spatial distribution of riotsFootnote79 is presented in .

Our main variable of interest, social cohesion, performs consistently when measuring crowd-sourced daily counts of riots (see ) and stone throwing (see ). Like all measures discussed above, the dependent variables derived from a Jewish Internet-based crowd-sourced platform may suffer from reporting biases. Thus, localized riots that do not harm Jewish Israelis may not appear in the data. This may raise concerns regarding underreporting. Alternatively, this measure may include exaggerated or false reports that are likely to lead to overreporting. Nonetheless, by triangulating three different data sources, and by showing the consistent impact of social cohesion on daily riot rates, we provide evidence for the importance of neighborhood-level social cohesion in the outbreak of riots.

To be clear, this empirical framework does not enable us to argue that a lack of social cohesion causes riots. However, the evidence above offers that neighborhoods that are socially cohesive, on average endure less riots and that this correlation survives controls for economic and ethnic variables and both spatial and temporal explanations. Our confidence is also strengthened by the variety of indicators for cohesion that construct our index, representing the different facets of cohesion. The diversity in data sources and approaches in the operationalization of cohesion supplies a wide foundation to the latent variable. That being said, we cannot rule out that cohesion is endogenous with our ethnic or economic variables, and that local riots may be impacted by omitted variables such as police presence and visibility and quality of governance more generally for which we do not have available data.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this article, we attempt to explain the determinants of a relatively understudied phenomenon within the conflict literature: urban intergroup violence. We adapted a neighborhood perspective in order to analyze spatiotemporal variation in violence occurring in Jerusalem between January 2013 and December 2015. The analyses show that intergroup violence is not distributed equally across urban space, and despite the considerable impacts of economic motivations, which are often accentuated in the study of ethnic conflicts, a major significant and robust determinant of intergroup violence is neighborhood social cohesion, which influences violence directly, and at times indirectly by moderating economic motivations. These findings prove to be consistent across three original granular datasets of intergroup violence occurring in Jerusalem during recent years and different scaling methods of the latent variable. We did not aim to, or indeed provide, a causal analysis that determines the relationship between cohesion and violence; however, we did show there is a robust negative correlation between our original measure of social cohesion and riots in East Jerusalem neighborhoods. This was consistent in three different datasets and also when controls were used for various alternative explanations, including economic cleavages and ethnic strife. The control for spatial interdependence in the riots, and previous day riots, further enhances our confidence in the results—showing that micro-level spatiotemporal dynamics indeed influence riots, but do not erase the significance of social cohesion.

Considering the ongoing intergroup tension and imminent presence of violence in Jerusalem during recent years, we argue that what drives residents out of their homes toward intergroup confrontations in urban environments is not only local accumulating dissent regarding ethnic friction and economic disadvantage, but more importantly social cohesion, or lack thereof, which is built on informal institutions, reputational motivations and personal connections. Thus, the variation in riots between Jabel Mukaber and At-Tur, two neighborhoods in the heart of East Jerusalem with relatively similar ethnic and economic motivations, portrays the momentous role of social organization with regard to urban violence. In other words, the difference between riot rates in both neighborhoods can be ascribed not to motivations, but rather to diverging social cohesion. On average, At-Tur’s rate of cohesion is less than half the rates of Jabel Mukaber, and as evident in our data, these lower levels of social cohesion are correlated with extremely differing sums of riots. Thus, between 2013 and 2015, the former, socially cohesive neighborhood has experienced one riot, whereas the latter in-cohesive neighborhood has experienced twenty-six riots.

The mechanism we outlined is not only pronounced in the correlation we found and the statical reality in these two neighborhoods, but also in the experience of practitioners and citizens on the ground. It is very hard to find counterfactual cases in which a riot was imminent, but then stopped due to local leadership in a cohesive neighborhood—since such negative cases are not reported. However, anecdotal evidence does support our view that local leaders use the power granted to them because of the cohesiveness of communities to stop the eruption of violence. Hasson reported on the experience of the civil leadership of East Jerusalem neighborhoods, particularly at Jabel Mukaber, during the wave of violence at the time.Footnote80 He interviewed members of parental committees, neighborhood committees, community center leaders, formal community secretaries, local campaigners, and local leaders. They reported that they feel that violent political struggles and protests are useless and lead to stagnation. They instead tried to lead nonviolent civil campaigns that focused on local issues, and channel anger to those campaigns instead of letting it erupt into riots with varying levels of success. “[T]he Palestinians in the city were left with no real leadership in the last decade. To this vacuum radical Muslim activists entered,” Hasson writes on the cause of the outbreak of violence in 2014.Footnote81 This pattern did not escape observation by governmental authorities. Following the outbreak of violence, the municipal administration of the city started promoting the communal feeling in neighborhoods to help prevent teenagers from turning to violent protest, including by starting youth groupsFootnote82 and by funding local cultural events during Ramadan.Footnote83 The police had initiated many diverse new policies of a similar nature, which are aimed at strengthening neighborhood cohesion. These include founding new community centers, cultural clubs and markets, and training local volunteers at communal organizing. They also started working with local village mukhtars in neighborhoods, the traditional leaders, to strengthen their authority. According to Halevi, the commander of the Jerusalem police district, “[A]ctions of this type are not the normal role of the police, but it prevents the need to increase patrols, deal with violent protests, stone throwing, and physical destruction, and they also reduce crime.”Footnote84

Despite our theoretical emphasis on neighborhood antecedents of intergroup violence, the choice of a SAR model serves as a clear statement that although the determinants of intergroup violence in urban settings are highly linked to meso-level motivations and social capacities, they are not independent of a broader urban and national context. Our results reiterate previous findings regarding the dependence of intergroup violence within specific locations on attributes of proximate neighborhoods, cities or regions. Thus, having “bad neighbors” can influence within-neighborhood dynamics of riots. If so, this model and the incorporation of citywide variables enable an analysis of intergroup violence as a complex phenomenon highly related to both meso-level and broader urban factors.

Our results are a step forward in understanding the dynamics of intergroup violence in ethnically divided cities. Emphasis was placed on culminating a neighborhood-level approach that accentuates the role of social cohesion in the study of violence. Doing so is especially important in contexts like Jerusalem and other divided cities where ethnic and economic motivations are categorically salient among members of a specific group within urban space.

Recent debates regarding policy measures to achieve a more peaceful fabric of life in Jerusalem have advocated for economic and infrastructural municipal investments within Palestinian communities. Alternatively, others propose that rather than integrate two groups in conflict, only partition and minimization of intergroup contact can alleviate the effects of conflict in Jerusalem. Acknowledging the partial validity of both perspectives, our analyses offer that, regardless of the top-down measures utilized to curb intergroup violence in Jerusalem, alleviating the outcomes of this phenomenon (both in our case and beyond) cannot be done without addressing bottom-up communities and their collective incentives and capacities to maintain conflict or cooperation.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (98.2 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Chagai Weiss, Andrea Ruggeri, Jessica di Salvatore, Noam Brenner, Noam Gidron, Omer Yair and Michael Freedman, as well as the editor and two anonymous reviewers, for helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Nir Hasson, “Urshalim: Israelis and Palestinians in Jerusalem 1967–2017,” Yediot Aharonot, 2017.

2 Jonathan Rokem, “Learning from Jerusalem: Rethinking Urban Conflicts in the 21st Century Introduction,” City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action 20, no. 3 (2016): 407–11.

3 Βαρρεττ Α. Λεε, Ραλπη Σ. Ορoπεσα, Βαρβαρα ·. Μετχη, ανδ Αϖερψ Μ. Γυεστ, ·Τεστινγ τηε Δεχλινε–oϕ Χoμμυνιτψ Τηεσισ: Νειγηβoρηooδ Οργανιζατιoνσ ιν Σεαττλε, 1929 ανδ 1979,· American Journal of Sociology 89, νo. 5 (1984): 1161; Ανδρεω ς. Παπαχηριστoσ, Δαϖιδ Μ. Ηυρεαυ, ανδ Αντηoνψ Α. Βραγα, ·Τηε Χoρνερ ανδ τηε Χρεω: Τηε Ινϕλυενχε oϕ Γεoγραπηψ ανδ Σoχιαλ Νετωoρκσ oν Γανγ ςιoλενχε,· American Sociological Review 78, νo. 3 (2013): 417; Ρoλανδ Λεσλιε Ωαρρεν, The Community in America. Ρανδ ΜχΝαλλψ Χηιχαγo, 1963; Βαρρψ Ωελλμαν ανδ Βαρρψ Λειγητoν, ·Νετωoρκσ, Νειγηβoρηooδσ, ανδ Χoμμυνιτιεσ: Αππρoαχηεσ τo τηε Στυδψ oϕ τηε Χoμμυνιτψ Θυεστιoν,· Υρβαν Αϕϕαιρσ Θυαρτερλψ 14, νo. 3 (1979): 363·90.

4 Ashutosh Varshney, “Ethnic Conflict and Civil Society: India and Beyond,” World Politics 53, no. 03 (2001): 362–98.

5 Susan Olzak, The Dynamics of Ethnic Competition and Conflict (Stanford University Press, 1994).

6 James D. Fearon and David D. Laitin, “Explaining Interethnic Cooperation,” American Political Science Review 90, no. 04 (1996): 715–35.

7 Jonathan Rokem, Chagai M. Weiss, and Dan Miodownik, “Geographies of Violence in Jerusalem: The Spatial Logic of Urban Intergroup Conflict,” Political Geography (2018): 88–97.

8 Marik Shtern, “Towards ‘Ethno-National Peripheralisation’? Economic Dependency Amidst Political Resistance in Palestinian East Jerusalem,” Urban Studies (2019); Marik Shtern and Jonathan Rokem, “Towards Urban Geopolitics of Encounter: Spatial Mixing in Contested Jerusalem,” Geopolitics (2021): 1129–47; Marik Shtern and H. Yacobi, “The Urban Geopolitics of Neighboring: Conflict, Encounter and Class in Jerusalem’s Settlement/Neighborhood,” Urban Geography (2019): 467–87.

9 Nufar Avni, “Between Exclusionary Nationalism and Urban Citizenship in East Jerusalem/ Al-Quds,” Political Geography (2020): 1; Nufar Avni, Noam Brenner, Dan Miodownik, and Gilaad Rosen, “Limited Urban Citizenship: The Case of Community Councils in East Jerusalem,” Urban Geography (2021): 4–5; Marik G. Raanan and Nufar Avni, “(Ad)dressing Belonging in a Contested Space: Embodied Spatial Practices of Palestinian and Israeli Women in Jerusalem,” Political Geography, 2020.

10 Daniel Arnon, Richard J. McAlexander, and Michael A. Rubin, “Social Cohesion and Community Displacement in Armed Conflict Evidence from Palestinian Villages in the 1948 War,” APSA Preprints (2021): 21–3; Sara Botterman, Marc Hooghe, and Tim Reeskens, “‘One Size Fits All’? An Empirical Study into the Multidimensionality of Social Cohesion Indicators in Belgian Local Communities,” Urban Studies (2012): 186–8; Gianmaria Bottoni, “A Multilevel Measurement Model of Social Cohesion,” Social Indicators Research (2018): 851–3.

11 Joseph Chan, To Ho-Pong, and Elaine Chan, “Reconsidering Social Cohesion: Developing a Definition and Analytical Framework for Empirical Research,” Social Indicators Research (2006): 288–91.

12 Malcolm Sutton, An Index of Deaths from the Conflict in Northern Ireland (2008).

13 Arif Hasan and Masooma Mohib, Urban Slums Reports: The Case of Karachi, Pakistan. Understanding Slums: Case Studies for the Global Report on Human Settlements (2003).

14 Claire M ́edard, “City Planning in Nairobi: The Stakes, the People, the Sidetracking.” In Nairobi Today: The Paradox of a Fragmented City, ed. H. Charton-Bigot and D. Rodriguez-Torres (Mkuki Na Nyota Publ., 2010), 25–60.

15 Nils B. Weidmann and Idean Salehyan, “Violence and Ethnic Segregation: A Computational Model Applied to Baghdad,” International Studies Quarterly 57, no. 1 (2013): 52.

16 Ravi Bhavnani, Karsten Donnay, Dan Miodownik, Mayaan Mor, and Dirk Helbing, “Group Segregation and Urban Violence,” American Journal of Political Science 58, no. 1 (2014): 226.

17 Stathis N. Kalyvas, The Logic of Violence in Civil War (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

18 Botterman et al., “One Size Fits All,” 186.

19 Paul Collier and Anka Hoeffler, “Greed and Grievance in Civil War,” Oxford Economic Papers 56, no. 4 (2004): 563–95.

20 Lars Erik Cederman, Andreas Wimmer, and Brian Min, “Why Do Ethnic Groups Rebel? New Data and Analysis,” World Politics 62, no. 01 (2010): 87–8.

21 Randall J. Blimes, “The Indirect Effect of Ethnic Heterogeneity on the Likelihood of Civil War Onset,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 50, no. 4 (2006): 536.

22 Fearon and Laitin, “Explaining Interethnic Cooperation”; Kalyvas, The Logic of Violence in Civil War.

23 Michael Mann, “The Social Cohesion of Liberal Democracy,” American Sociological Review (1970): 423–39.

24 Chan et al., “Reconsidering Social Cohesion,” 288.

25 Ade Kearns and Ray Forrest, “Social Exclusion, Social Capital and the Neighbourhood,” Urban Studies (2001): 2125–43.

26 Robert J. Sampson and Byron W. Groves, “Community Structure and Crime: Testing Social Disorganization Theory,” American Journal of Sociology 94, no. 4 (1989): 774–802; Robert J. Sampson, Stephen W. Raudenbush, and Felton Earls, “Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy,” Science 277, no. 5328 (1997): 918; Ora M. Simcha-Fagan and Joseph E. Schwartz, “Neighborhood and Delinquency: An Assessment of Contextual Effects,” Criminology 24, no. 4 (1986): 667.

27 Gretchen Helmke and Steven Levitsky, “Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics: A Research Agenda,” Perspectives on Politics 2, no. 4 (2004): 725–40, at 727.

28 Sampson and Groves, “Community Structure and Crime”; Sampson et al., “Neighborhoods and Violent Crime”; Clifford R. Shaw and Maurice E. Moore, The Natural History of a Delinquent Career (University of Chicago Press, 1931).

29 Fearon and David D. Laitin, “Explaining Interethnic Cooperation.”

30 James D. Fearon, “Ethnic Mobilization and Ethnic Violence,” The Oxford Handbook of Political Economy (2006): 852–68.

31 Sherrill Stroschein, “Politics Is Local: Ethnoreligious Dynamics under the Microscope,” Ethnopolitics 6, no. 2 (2007): 173–85.

32 Ted Robert Gurr, “Why Minorities Rebel: A Global Analysis of Communal Mobilization and Conflict since 1945,” International Political Science Review (1993): 161–201.

33 Ibid.

34 Lars E. Cederman and L. Girardin, “Beyond Fractionalization: Mapping Ethnicity onto Nationalist Insurgencies,” American Political Science Review 101, no. 01 (2007): 173; Cederman et al., “Why Do Ethnic Groups Rebel?.”

35 Donald L. Horowitz, Ethnic Groups in Conflict (University of California Press, 2001).

36 James D. Fearon and David D. Laitin, “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War,” American Political Science Review 97, no. 01 (2003): 75–90; M. Humphreys and J. M. Weinstein, “Who Fights? The Determinants of Participation in Civil War,” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 2 (2008): 436; Edward Miguel, Satyanath Satyanath, and Ernest Sergenti, “Economic Shocks and Civil Conflict: An Instrumental Variables Approach,” Journal of Political Economy 112, no. 4 (2004): 725; Dan Miodownik and Lilach Nir, “Receptivity to Violence in Ethnically Divided Societies: A Micro-Level Mechanism of Perceived Horizontal Inequalities,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 39, no. 1 (2016): 22–45.

37 Kyle Beardsley, “Peacekeeping and the Contagion of Armed Conflict,” The Journal of Politics 73, no. 4 (2011): 1051; Kyle Beardsley, Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, and Nigel Lo, “Roving Bandits? The Geographical Evolution of African Armed Conflicts,” International Studies Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2015): 503–16; Idean Salehyan and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, “Refugees and the Spread of Civil War,” International Organization 60, no. 2 (2006): 335; Sebastian Schutte and Nils B. Weidmann, “Diffusion Patterns of Violence in Civil Wars,” Political Geography 30, no. 3 (2011): 143–52; Y. Yuri M. Zhukov, “Roads and the Diffusion of Insurgent Violence: The Logistics of Conflict in Russia’s North Caucasus,” Political Geography 31, no. 3 (2012): 144.

38 Anjali Thomas Bohlken and Ernest John Sergenti, “Economic Growth and Ethnic Violence: An Empirical Investigation of Hindu – Muslim Riots in India,” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010): 589; Sarah Zukerman Daly, “Organizational Legacies of Violence: Conditions Favoring Insurgency Onset in Colombia, 1964–1984,” Journal of Peace Research 49, no. 3 (2012): 473.

39 Hillel Cohen, Kikar Hashuk Reika (Jerusalem Insititute for Israel Studies, 2007); Yitzhak Reiter, Muhamad Nchal, Israel Kimchi, and Lior Lehers. The Arab Neighborhoods in East Jerusalem (2014); Anne B. Shlay and Gillad Rosen, Jerusalem: The Spatial Politics of a Divided Metropolis (John Wiley & Sons, 2015).

40 Hasson, “Urshalim”; Shlay and Rosen, Jerusalem.

41 Reiter et al., The Arab Neighborhoods in East Jerusalem.

42 Residents are allowed to participate in municipal election as voters but not as candidates.

43 Ibid.

44 Hasson, “Urshalim.”

45 Cohen, Kikar Hashuk Reika.

46 Mohammad Ali Kadivar and Neil Ketchley, “Sticks, Stones, and Molotov Cocktails: Unarmed Collective Violence and Democratization,” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World (2018): 3.

47 Ibid.

48 Bottoni, “A Multilevel Measurement Model of Social Cohesion.”

49 Chan et al., “Reconsidering Social Cohesion.”

50 Botterman et al., “One Size Fits All.”

51 Kearns and Forrest, “Social Exclusion.”

52 Chan et al., “Reconsidering Social Cohesion.”

53 Brian L. Heuser, “Social Cohesion and Voluntary Associations,” Peabody Journal of Education (2005): 16.

54 Ida Rudolfsen, “Food Price Increase and Urban Unrest: The Role of Societal Organizations,” Journal of Peace Research (2021): 215.

55 Jan Delhey, Klaus Boehnke, Georgi Dragolov, Zsófia S. Ignácz, Mandi Larsen, Jan Lorenz, and Michael Koch, “Social Cohesion and Its Correlates: A Comparison of Western and Asian Societies,” Comparative Sociology (2018): 427.

56 Chan et al., “Reconsidering Social Cohesion.”

57 Ichiro Kawachi, Bruce Kennedy, and Richard G. Wilkinson, “Crime: Social Disorganization and Relative Deprivation,” Social Science & Medicine 48, no. 6 (1999): 719–31.

58 Ibid.

59 Sampson and Groves, “Community Structure and Crime”; Sampson et al., “Neighborhoods and Violent Crime.”

60 Yearly rate for 2014.

61 Yearly rate for 2013.

62 Yearly rate for 2014.

63 Yearly rate for 2015.

64 Botterman et al., “One Size Fits All.”

65 Kearns and Forrest, “Social Exclusion.”

66 Botterman et al., “One Size Fits All.”

67 Arnon et al., “Social Cohesion and Community Displacement.”

68 Ibid.

69 Hasson, “Urshalim.”

70 Data was obtained from Peace-Now, an Israeli NGO. Their data are available in English at https://peacenow.org.il/en/settlemwatch/israeli-settlements-at-the-west-bank-the-list

71 Hasson, “Urshalim.”

72 Our data include 547 days prior to these occurrences which are given a value of 0.

73 Census data are available for the years 2013 and 2015. In order to fill in the gap for 2014, we calculated the average yearly population growth according to existing data.

74 Helmke and Levitsky, “Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics.”

75 Botterman et al., “One Size Fits All.”

76 Federico Belotti, Gordon Hughes, and Andrea Piano Mortari, “Xsmle: Stata Module for Spatial Panel Data Models Estimation,” 2017; Michael D. Ward and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, Spatial Regression Models (Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences Series) (SAGE Publications, 2008).

77 The VIF score for the population variable is not too high (VIF = 1.93), but there is a strong correlation (r = −0.65) between it and the cohesion variable that may cause it to weaken the results due to multicollinearity. We also tested several alternative scales to index our different proxies for cohesion, with similar results in their relationship with riots.

78 We do not interact our ethnic friction and cohesion variables, since ethnic friction does not seem to have a statistically significant impact on riots in all our models. The results of such interaction are anyway not significant.

79 Our more inclusive variable.

80 See Hasson, “East Remains East: The Leadership in East Jerusalem Is Oppressed, and Violence Is Surging” (in Hebrew), 2014, accessed at https://www.haaretz.co.il/news/politics/.premium-1.2499290

81 Ibid.

82 See Hasson, “The Traffic Didn’t Shorten, But the Light Rail Is Changing the Face of Jerusalem” (in Hebrew), 2021, accessed at https://www.haaretz.co.il/news/local/.premium.HIGHLIGHT-MAGAZINE-1.10091433

83 See Briner and Hasson, “Following the Clushes Last Year: The Police Will Not Place Fences in Demascus Gate in the Ramadan” (in Hebrew), 2022, accessed at https://www.haaretz.co.il/news/politics/.premium1.10618076

84 As reported and quoted at the report on police activity in East Jerusalem, the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research (in Hebrew), accessed at https://jerusaleminstitute.org.il/events/police-in-east-jeru/