Abstract

This article critically evaluates the impact of existing terrorism offenses in countering extreme right-wing terrorism (ERWT) in the United Kingdom (U.K.) in order to examine why this developing threat to security has yet to elicit any legislative counter measures. Informed by evidence from a comprehensive dataset of ERWT convictions between 2007 and 2022 it finds that terrorist offenses have been sufficiently adaptive as to have had a significant impact in countering ERWT, negating any need for reform. Concerns, however, are identified in the application of existing measures and suggestions are made as to how they should be addressed to enhance their impact.

In recent years, security and intelligence experts in the United Kingdom (U.K.) have been paying increasing attention to the threats to national security posed by violent individuals and groups espousing extreme right-wing ideologies. While militant Islamism remains the principal concern of the U.K.’s security services, the threat of extreme right-wing terrorism (ERWT) has grown markedly since 2014.Footnote1 Indicative of this trend, 12 out of 32 foiled late-stage terrorism plots between March 2017 and December 2021 involved extreme right-wing terrorists.Footnote2 Moreover, currently approximately 40 percent of terrorism-related arrests and 20 percent of counter terrorism investigations concern individuals and groups associated with far-right ideological perspectives.Footnote3

While the growing threat of ERWT is acknowledged by the U.K. government it is striking that, in contrast to responses elicited by Northern Ireland and militant Islamist terrorism, it has not resulted in the introduction of any new legislative counter measures. Scholars have referred to the extensive development of counter terrorism law in the U.K. over the last 50 years in response to Northern Ireland and Islamist-based violence as representing a “spiral” – a constant, relentless response to new forms of terrorist threats.Footnote4 However, the U.K.’s reaction to the threats posed by ERWT to date must be characterized as one of “stasis,” represented by a lack of any legal counter response.

It is possible that the determinants of this legislative stasis are to be found either in lessons learned from the damaging impact of measures introduced in “knee-jerk” emergency legislation enacted in response to terrorist threats in the past.Footnote5 Moral panic conceptual approaches to legislative development may also invite conclusions that the ERWT threat has yet to engender sufficient levels of moral outrage and fear amongst the public to induce the political elite to act by introducing new counter measures.Footnote6 It is more likely, however, that the rationale for the lack of any legislative response triggered by ERWT is to be located in the adaptive capacity of existing counter-terrorism legislation. This assumes that terrorism offenses introduced in response to Northern Ireland and Islamist terrorism are capable of having a significant impact in countering the activities of ERWT. It is this proposition that this article aims to test.

Very little robust evidence-based scholarly attention has been paid to examining this critical issue. Almost nothing has been said about the implementation of existing terrorism-related offenses on cases involving extreme right-wing terrorists. An emerging body of scholarly work has contributed to reducing the deficit, though it has either not been focused specifically on U.K. legal counter measures or has been more concerned with exploring sources of radicalization and political, as well as historical, contextual contributions to the emerging ERWT threat.Footnote7 Yet accurately identifying ERWT offending, the types of offenses which are relevant to it, and how they are applied, could not be more important. Indeed, this has become a priority concern for many states and the United Nations Security Council. In June 2021 the General Assembly called on Member States to develop their understanding of threats presented by terrorism based on xenophobia, racism and other forms of intolerance, or in the name of religion or belief (“XRIRB Terrorism”) and develop effective responses through national legislation and the establishment and maintenance of criminal justice systems.Footnote8 In response to this the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has recently been working on a project funded by the German Federal government designed to enhance conceptual and analytical understanding of XRIRB Terrorism and the relevance of existing criminal justice mechanisms for countering it.Footnote9 Furthermore, with the exception of the U.K. and Germany, there have been very few prosecutions in other jurisdictions of individuals associated with the far-right for terrorist offenses. The experience of the U.K. in applying existing legislation therefore offers important lessons for other countries facing surges in far-right violence, particularly former Commonwealth states and those with similar adversarial criminal justice systems that historically have looked to the U.K. for inspiration when developing counter-terrorism legislation.

Empirically informed by a range of sources, including government reports and interviews with prosecutors, this article fills an important gap in existing scholarship by critically evaluating the impact of existing terrorism offenses in countering ERWT. It seeks to achieve this by means of an in-depth analysis of the substantive terrorism offenses that have been most relevant for convictions of individuals associated with ERWT in the U.K. between 2007 and 2022, which is informed by findings from a high-resolution dataset of convictions for these offenses during this period. In doing so it critically assesses the impact of these offenses in reducing the risk of ERWT, highlights prosecutorial and evidential challenges and proposes a number of policy and practice recommendations. It finds that legislation introduced to combat Northern Ireland and Islamist-based terrorism has been sufficiently adaptive as to have a significant impact on extreme right-wing terrorist offending. In total, 70 individuals associated with the far-right have been convicted of over 200 separate terrorist offenses during the examined 15-year period. All of these convictions relate to just eight specific offenses contained in existing legislation enacted in 2000 and 2006. The spiraling pattern of legislative reform designed to counter Islamist terrorism and political violence in Northern Ireland over the last 50 years has resulted in the introduction of a range of terrorist offenses equally significant for combatting ERWT. The current legislative stasis is therefore understandable, though problems are identified in the application of existing measures to ERWT and proposals are made as to how they should be addressed in order to enhance their impact in countering this and other forms of terrorism. The first part of the article examines the evolution of the threat of ERWT in the U.K. Part two articulates the “spiral to stasis” conceptualization of U.K. legislative responses to new terrorist threats. Part three outlines the methodology for the compilation of the dataset and analyses the offenses revealed by it to have been most relevant to ERWT offending, while part four draws some broader conclusions.

Evolution of the ERWT Threat in the U.K.

ERWT in the U.K. has associations with the broader far-right movement, the origins of which can be traced to Sir Oswald Mosley’s ultranationalist British Union of Fascists banned by the government in 1940. Politically motivated violence and terrorism have been persistent features of this movement, which comprises a complex assortment of political parties, street movements, extremist organizations and atomized lone actors advocating a diverse range of ideologies and narratives. Indeed, violent extremist and terrorist acts of individuals connected with associated political parties, such as the National Front, which emerged in late 1960s, and its 1980s offshoot, the British Nationalist Party (BNP), have contributed to undermining the legitimacy of these parties and ensuring that they have operated largely at the fringe of the British political system. Notable examples include David Copeland’s bomb attack in Soho, London in 1999, killing 3 people and injuring 140 others, and David Folley’s racially aggravated murder of an individual in 2010. Both had links with the BNP.Footnote10 Several other supporters of the party have been convicted of offenses relating to possession of weapons, ammunition and explosives.Footnote11

The nationalist and anti-immigration agenda of the BNP has been shared by more recently formed far-right street movements, including Britain First and the English Defence League (EDL), both of which also have links violent activity. Britain First, formed in 2011, assumed a combative approach advocating “mosque invasions” and “Christian patrols” contributing to a noticeable trend of targeted attacks by far-right activists on Islamic centers throughout Britain. Since 2013 at least 7 violent attacks have taken pace or been foiled at or outside mosques and Islamic community centers.Footnote12 Individuals associated with the EDL have also been linked to arson attacks on mosques, racially aggravated murder and possessing equipment for bomb making.Footnote13

In 2013, when the EDL had become increasingly marginalized amongst the far-right milieu following the resignation of its leader, and the BNP had collapsed amid internal disputes and claims of corruption, the British government evaluated right-wing extremism as constituting “a very low risk to national security.”Footnote14 This threat assessment changed following the emergence in 2014 of the neo-Nazi organization “National Action,” (NA) which espoused a national socialist, white supremacist agenda and engaged in an aggressive campaign to radicalize individuals to commit acts of violence. An attempted murder of a Sikh dentist by a young man found in possession of NA material in 2015,Footnote15 and the conviction of a member of NA for an offense in connection with possession of pipe bomb in 2016Footnote16 alerted authorities to NA’s increasing threat to security and contributed to the government’s resolution to proscribe it in December 2016, a decision compounded by the organization’s glorification of far-right extremist Thomas Mair’s murder of Jo Cox MP earlier that year.

In the two-year period following Jo Cox’s murder the number of individuals detained for ERWT offenses in the U.K. increased nearly fivefold.Footnote17 Those convicted included Darren Osborne who perpetrated a vehicle attack on a crowd of Muslim worshipers at a Mosque in Finsbury Park in 2017, killing one of them,Footnote18 and Jack Renshaw, a member of NA, charged with preparing acts of terrorism for plotting to kill Rosie Cooper MP and a police officer.Footnote19 In 2019 45 percent of cases referred to the U.K. counter-terrorism program Channel involved right-wing radicalization, eclipsing cases of Islamist radicalization, and the following year the Metropolitan Police Assistant Commissioner confirmed that far-right violent extremism represented the fastest growing threat to the country.Footnote20 By this stage, such was the Home Office’s level of concern over the rapidity of the evolution of the ERWT threat it had transferred responsibility for its detection from the police to the security service MI5, placing the terrorist risk from ERWT for the first time alongside that presented by Islamist and Northern Ireland dissident Loyalist and Republican groups.

The intensification of the threat of ERWT to national security over the last decade is not a phenomenon unique to the U.K. Over the same period similar dynamics have been observed in other countries in Western Europe and in North America, Australia and New Zealand.Footnote21 Horrific attacks were conducted by right-wing extremists in Christchurch, New Zealand in 2019 and in Halle and Hanau in Germany in 2019 and 2020. Following the Hanau attack the German justice minister confirmed that far-right terrorism represented the most significant threat to democracy in the country.Footnote22 By then, according to Germany’s domestic security services nearly 13,000 far-right extremists were thought to be “orientated toward violence.”Footnote23 Meanwhile, in Australia investigations concerning ideologically-motivated violent extremism have increased to the extent that they constitute roughly 40 percent of the workload of its security intelligence services;Footnote24 and in the United States right-wing actors have been responsible for more incidents resulting in victims being killed than radical Islamist violent extremists since 2001.Footnote25 These developments are indicative of recent trans-national surge in far-right terrorist activity underpinned by online interconnectivity, which contributes to the radicalization of individuals in the U.K. and accentuates the threat of ERWT to domestic security.

Conceptualising Legislative Responses to New Terrorist Threats in the U.K.: From Spiral to Stasis

A prevailing narrative in scholarship concerned with state responses to terrorism proposes that counter-terrorism legislation develops in response to new terrorist threats to national security.Footnote26 New terrorist crises, according to this conventional view, prompt normative government responses frequently characterized by the introduction of new legislative measures designed to criminalize terrorist behavior, extend the powers of law enforcement agencies and enhance investigative techniques for apprehending and prosecuting suspects.

The U.K.’s legislative responses to political violence in Northern Ireland and, more recently, to Islamist-inspired violence support this assumption. Reacting to increasing threats to security arising from an escalation in violence in 1972, the province’s most violent year, the government quickly enacted The Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1973 (EPA), which introduced new powers of arrest, detention and proscription. When bomb attacks on two public houses in Birmingham the following year signaled a migration of violence from Northern Ireland to mainland Britain, the government introduced additional measures into criminal law in England and Wales under The Prevention of Terrorism Act 1974 (TPA).Footnote27 Subsequently, in response to changing threats from both Northern Irish and militant Islamist terrorism, the EPA and the TPA were repealed and its measures were consolidated in the Terrorism Act 2000 (TA 2000). Later, in response to calls for legislative innovations by United Nations Security Council Resolutions passed following the 9/11 attacks in 2001, and in reaction to the London 7/7 bombings in 2005, the U.K. Parliament enacted several pieces of legislation containing new criminal offenses designed to counter both the domestic and global dimensions of a new terrorist threat arising from Al-Qaeda and its affiliates.Footnote28 More recently, and pursuant to attacks at Fishmongers’ Hall, Streatham in 2019 and Forbury Gardens, Reading in 2020 committed by individuals and former offenders associated with Islamist terrorism, Parliament has introduced new measures which have increased sentencing provisions under existing terrorism legislation and strengthened the management of terrorist risk offenders.Footnote29

A significant body of scholarship has examined the impact that these legislative measures have had on countering terrorism in the U.K.Footnote30 Much of this work has been concerned with distortions to the delicate balance between enhancing state security and protecting civil liberties and on intrusions into the civilian sphere brought about by coercive measures introduced in reactive and hastily enacted legislation that deviate from established principles of criminal law and legality.Footnote31 A pattern of legislative response has been observed in this scholarly work involving the introduction, often under emergency provisions, of wide-ranging and broadly defined new measures which extend the powers of law enforcement agencies and introduce new criminal offenses, and which, over time, become permanent, later applying to non-terrorist crimes.Footnote32 Typically, as part of this pattern of response, human rights-based court and parliamentary interventions often diminish the intended effect of new measures, resulting in the government passing more repressive iterations in later legislation. What emerges from this body of work is that the development of counter-terrorism law in the U.K. can appropriately be characterized by what Donohue has referred to as a “spiral” – a constant, relentless developmental response to new forms of terrorism.Footnote33

In the context of responses to ERWT this spiral effect is perceptible in many of the countries that have been experiencing increases in this evolving threat to security in recent years. In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in Utoya and Oslo the Government of Norway enacted 31 policy responses and amendments to its Penal Code enhancing weapons control, surveillance and data collection powers. Footnote34 Australia enacted a Criminal Code Amendment (Sharing Abhorent Violent Material) Act in 2019 in response to changes to the threat landscape of far-right terrorism. In Germany, the Federal Parliament passed the Act on Combatting Right-Wing Extremism and Hate Crime in 2021, which introduced a range of measures designed to curb online hate and anti-Semitic speech and protect victims from increased threats from right-wing extremist circles. Moreover, in response to recommendations by a Royal Commission enquiry initiated by the Christchurch attacks, the New Zealand Parliament introduced new legislation in September 2021 which substantially amended the definition of a terrorist act, criminalized the planning of a terrorist attack and granted enforcement agencies increased powers to prevent terrorist activities.Footnote35

Unlike these countries, however, and in stark contrast to the aggressive legislative reaction generated by Northern Ireland and Islamist-based terrorism, the recent surge in ERWT has not triggered any legislative reform in the U.K. Scholars have previously questioned the adaptive potential of existing terrorism offenses, noting that some that were introduced in response to a particular terrorist threat - Northern Ireland or militant Islamism – have had limited application to the other.Footnote36 Yet the observed legislative stasis assumes that the same terrorism offenses are sufficiently adaptive to be capable of disrupting ERWT activity, negating any necessity for continued, spiraling reform. It is to these terrorism-related offenses that this article turns next in order to assess their applicability to ERWT and impact in countering it.

Methodology

This study is concerned with the applicability of existing counter-terrorism legislation to ERWT. It therefore focuses on the implementation of substantive counter terrorism law on cases involving extreme right-wing terrorists. These laws include the TA 2000, the Anti- Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, the Terrorism Act 2006 (TA 2006), the Counter-Terrorism Act 2008, the Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Act 2011, the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015, the Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Act 2019, the Counter-Terrorism and Sentencing Act 2021. These pieces of legislation contain a range of offenses specific to terrorist- related activity. Other criminal offenses such as murder, manslaughter and keeping explosives with intent to endanger life or property may be connected to terrorism but are not contained in substantive terrorism legislation and are therefore not included in the dataset.Footnote37

The dataset analyses cases involving the conviction of ERWT individuals for substantive terrorist offenses between 2007 and 2022. This period was selected because it represents an important 15-year period in the evolution of far-right terrorism in the U.K., during which it has been assessed as presenting a low risk to national security, a risk significant enough to warrant the transfer responsibility for investigating it from the police to the security services and the second most significant threat to security in the U.K., behind only that of Islamist terrorism. By selecting this period of fluctuating far-right threats to security the study seeks to avoid bias in statistical analysis caused from collecting data only during periods of minimal or heightened levels of terrorist offending.

It was compiled following a systematic collation and examination of open-source data, news reporting and information from government agencies, including the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and the Home Office, as well as transcripts of court cases and sentencing remarks. The variables for which evidence was compiled, where available from these sources, included (1) the terrorist offenses for which an individual has been convicted and the number of counts for each particular offense; (2) sentences imposed following conviction; (3) date and location of incident; (4) organizational affiliation of the offender, if any; (5) whether they were acting alone; (6) the target involved, if any; (7) whether the incident resulted in any victims being killed or wounded; and (8) the mental health of offenders. Interviews with experts involved in the prosecution of individuals associated with ERWT informed analysis of the law.

Dataset and Analysis

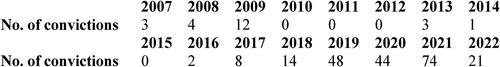

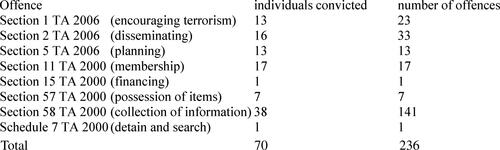

The dataset reveals that between 2007 and 2022 70 individuals associated with ERWT were convicted of 236 substantive terrorist offenses ( and ). Indicative of a recent escalation in far-right terrorist offending 70 percent (166) of convictions for these offenses during this 15-year period were secured between 2019 and 2021. All of those convicted were men apart from two women who were convicted of membership to a proscribed organization as a result of their association with NA.Footnote38

Figure 1. Individuals convicted and number of offenses committed per offense (2007–2022). *Some individuals were convicted of more than one terrorism offense. As a result, the total number of separate individuals convicted of one or more terrorism offenses is 70.

A majority of 67 percent (47) of convictions involved individuals acting alone.Footnote39 The remainder were convicted of offenses in connection with membership of a proscribed organization or were part of small groupuscules of between two and four individuals. All convictions related to eight specific offenses contained in the TA 2000 and the TA 2006. The most relevant offenses for ERWT are encouraging acts of terrorism,Footnote40 disseminating terrorist publications,Footnote41 planning terrorist acts,Footnote42 possession of items for terrorist purposes,Footnote43 collection of information for terrorist purposesFootnote44 and membership of a proscribed organization.Footnote45 One individual was convicted of a terrorist financing offenseFootnote46 and another of an offense under Schedule 7 TA 2000 for refusing to provide authorities with passwords to his computers.Footnote47 The contours of the more significant offenses in terms of their impact in countering ERWT are examined below.

Collection of Information:Section 58TA 2000

The offense under Section 58 of the TA 2000 requires the prosecution to prove that an individual has collected, possessed or viewed any information “likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism” and that they knew the nature of the information in their possession.Footnote48 It is a defense if the defendant can establish a reasonable excuse on the basis that they “did not know and had no reason to believe” that the information was of the necessary character.Footnote49

Earlier incarnations of s 58 were first provided for in legislation applying to Northern Ireland, before being extended to the rest of the U.K. in 1994 and later consolidated in the TA 2000.Footnote50 The dataset reveals that it has had significant relevance to ERWT. In total, 38 extreme right-wing terrorists were convicted of 141 counts of the offense between 2007 and 2022. The broad ambit of the offense, which is not concerned with the intent of the defendant, and the fact that a defendant can be liable for multiple counts of the offense relative to the number of publications they have accessed, underscore a finding from the dataset that there has been a greater degree of offending for this offense than for all of the other terrorism offenses combined during this period.

Cases concerning the far-right provide support for critiques which point to the criminal boundaries of the offense being unsatisfactorily broad in terms of the conduct that it seeks to prohibit, and unnecessarily indeterminate, lacking clarity as regards firstly, what information is caught by the offense and, secondly, what is capable of amounting to a reasonable excuse.Footnote51 The first problematic interpretive issue, concerning the information that is likely to considered useful to a terrorist to trigger the offense, has become a matter for judicial interpretation. The House of Lords has provided guidance, determining that the information must be of use to terrorists, not ordinary people, and designed to provide practical assistance to them.Footnote52 Convictions of Extreme Right-Wing Terrorists have in many instances involved the possession of instruction manuals for developing IEDs and recipes for constructing and employing weapons to inflict serious harm on members of the public. Ian Davison, the first person in the U.K. to be convicted for producing a chemical weapon, was found guilty of 3 counts of the s 58 offense in 2009.Footnote53 Mark Colborne planned a mass cyanide attack.Footnote54 Conor Ward had collected manuals on the manufacture of explosives and biological and chemical weapons;Footnote55 and David Dudgeon had in his possession instructions for producing chemical and biological weapons, as well as video files containing techniques for attacking people with knives.Footnote56

It is uncontroversial that these types of publications could be considered useful to prospective terrorists and therefore capable of satisfying one of the key evidential requirements of the s 58 offense. In many of these cases it is notable that the defendants possessed similar publications. Indeed, successful convictions have assisted counter-terrorism police and the CPS in the creation of a database of material capable of being useful to a terrorist. The independent reviewer of terrorism legislation has confirmed that prosecutions for s 58 offenses often depend on police “striking lucky” and finding material which ‘provides a “hit” against this database.Footnote57 If an item is not on this database, the prosecution will have to decide whether or not it falls within the ambit of the offense. Nevertheless, cases involving the far-right reveal that it is evidently not always clear to the police, prosecution or, indeed, to individuals charged with an offense whether any particular material may or may be likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism. An individual, for example, was recently charged and prosecuted for the s58 offense for possessing a publication entitled “The Ethnic Cleansing Manual.”Footnote58 However, he was acquitted on the basis that it was adjudged to have amounted to no more than the delusional ramblings of the author rather than something that could be useful for terrorist purposes. This lends credence to Cornford’s concern that the material that can potentially be captured by the offense remains worryingly “mysterious.”Footnote59

Bearing in mind the established rule of law ideal that individuals “should know what is and is not legally authorized” in order to be able to make rational choices about their behavior it is understandably problematic if there is any uncertainty about what material may or may not satisfy the offense.Footnote60 In this regard, the police and prosecution appear to be at an advantage over the public as they have to hand a database of material the possession of which by any defendant is likely to be considered sufficient to warrant a prosecution and lead to a conviction. Individuals unsure about whether or not to download particular material do not have the same information. The result is that the offense imposes safeguarding duties on individuals in terms of the material they may possess but there is greater executive certainty over the nature and extent of that duty than there is to members of the public who may find themselves liable to have breached it. Publication of the database would enhance transparency and provide a measure of equivalence between the executive and the public in terms of understanding the criminal scope and margins of the offense. It may also provide some clarity with regard to the second issue of interpretative concern relating to the s 58 offense, namely the reasonable excuse defense.

Here, the House of Lords have confirmed that defendants will need to establish an “objectively reasonable” excuse for explaining why they “did not know, and had no reason to believe” that the information was likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism.Footnote61 Critics have alluded to unsatisfactory uncertainty over the limits of the defense and insufficient guidance for juries as to whether and when they might be able to accept possession for reasons of “personal interest or simple curiosity” as excusable.Footnote62 The cases in the dataset reveals that the defense has been interpreted narrowly and these types of excuses are unlikely to be persuasive. Those who have accessed material online where a summary of content is provided for perusal before it can be downloaded have understandably found it more difficult to establish a defense that they did not know its nature.Footnote63 It has similarly been problematic for defendants to rely on the defense in situations where the title of the document that they accessed and saved – in one case, for example, “Home Made Detonators” – renders the content of the material so obvious that the defendant is unlikely to be able to demonstrate that they had no reason to believe that it might be useful to a prospective terrorist.Footnote64 Furthermore, defendants who have claimed that their possession of material was “an act of early teenage folly”Footnote65 or “research out of boyish curiosity”Footnote66 have failed to persuade either the judge or the jury that these were objectively reasonable excuses. Similar types of excuses of being able to boast to anyone of having it,Footnote67 “boredom,”Footnote68 “academic interest,”Footnote69 being “unaware of the nature of the documents”Footnote70 and required for “the proper conduct of a security business”Footnote71 have been unsuccessful. These cases provide useful precedents for a better understanding of the limits of the s 58 defense. Nevertheless, it is axiomatic that it is much less likely that defendants will seek to rely on it if evidence is established that they were aware of the contents of a publicly available database of material that has previously been adjudged to have been of the necessary character.

While the s 58 offense has been effective in restricting the circulation of information potentially useful to individuals connected to the far-right who may have a terrorist ideation, and, in this respect, offers a pragmatic means of protecting society, the cases in the dataset reveal two problematic issues. Firstly, it is capable of penalizing conduct in situations where the harm is remote, criminalizing possession which involves neither the infliction nor the threat of harm and punishing individuals who view particular material but who are unlikely to have any terrorist purpose.Footnote72 Approximately 68 percent of those individuals convicted of at least one count of the s 58 offense between 2007 and 2022 were only convicted of this offense. They had neither disseminated the information they possessed, nor had they used it to encourage others to commit acts of terrorism. The nature of the information and their possession of it alone was sufficient to render them culpable of the offense, irrespective of whether they had no connection with terrorist acts in the past and were potentially unlikely to in the future. Moreover, 24 percent of those convicted of the offense were vulnerable adults who had a history of mental health issues, including personality disorders, and autistic spectrum disorder (ASD).

Secondly, for the purposes of the defense, it is irrelevant that the documents are widely available and can be purchased online via, for example, Amazon. The ease of access of some of the publications that commonly appear in these cases continues to be an issue of concern. Judge John Milford called for the publication accessed via Amazon by Ian Davison to be removed from its website and copies destroyed in its warehouses when convicting him for the s 58 offense in 2010.Footnote73 Yet Oliver Bel, who complained that it was “strange that [he] should be punished for possession of a freely available book”Footnote74 when he was convicted of the offense in 2021, had been able to access the same publication online from Amazon 11 years later. If the U.K. government is genuinely concerned with preventing the collection of information that is useful to terrorists and restricting its circulation, in line with its commitments alongside other G7 states outlined in the Taormina statement of the fight against terrorism and violent extremism, it must apply greater pressure on private commercial companies that sell these publications to conduct more rigorous safeguarding procedures.Footnote75

Encouraging Terrorism and Disseminating Terrorist Publications: Sections 1 and 2 TA 2006

The offense under section 1 of the TA 2006 prohibits the publication of statements with the intent to directly or indirectly encourage others to commit, prepare or instigate acts of terrorism or when reckless as to whether others will be so encouraged. Statements which are likely to be understood to glorify the commission or preparation of terrorist acts in the past, future or generally are included within the ambit of the offense. Its allowance for “direct or indirect” inducement, the expansive possibility of “likely” and an all-encompassing “past, future or generally” time scale for glorification substantially broaden the scope of the offense in terms of the kind of conduct it prohibits the type of conduct it construes as constituting terrorism.Footnote76 A similarly broadly constructed offense under section 2 criminalizes the dissemination of terrorist publications.

Both offenses were added to the armory of U.K. terrorism offenses in response to the terrorist attacks in London in 2005. In terms of their adaptivity, they have been relevant to prosecutions of Islamist-inspired terrorists but have had limited application to political violence in Northern Ireland. They have, nevertheless, been significant for ERWT. Since 2007 13 individuals associated with ERWT have been convicted of 23 counts of encouraging terrorism and 16 have been convicted of 33 counts of disseminating terrorist publications. In the majority of these cases, the individuals concerned were also convicted of offenses under s 58 relative to their possession of documents and information which they disseminated or the process of their encouragement of terrorism. Notably, all 56 counts of the two offenses were prosecuted between 2019 and 2022. No individual associated with ERWT was convicted of either offense in the proceeding 11-year period. This may be indicative of the impact of MI5 engagement in the investigation of ERWT. Alternatively, it points to a prevailing trend of ERWT offending involving the incentivization of violence amongst others as a way of promoting a violent subcultural status amongst the far-right milieu, accelerated by technological advances and the development of new encrypted online platforms. Morgan Seales and Gabriele Longo were convicted of offenses under section 1 after encouraging attacks on mosques similar to those perpetrated in New Zealand via messages posted on a WhatsApp group.Footnote77 Sam Imrie was convicted of the same offense in after filming himself setting fire to a building and uploading the video footage, pretending that it was an Islamic center and posting statements on Facebook and Telegram;Footnote78 and Michael Nugent was convicted of 5 counts of the section 2 offense for distributing copies of manuals for the construction of bombs and firearms via various online chat groups.Footnote79

These cases are likely to represent only the tip of the iceberg in terms of ERWT breaches of these offenses. Extreme Right-Wing Terrorists are generally tech-savvy, and employ “dark net” sites, virtual private networks and internationally-based “free speech” platforms such as Gab and 4chan to avoid detection of their dissemination of terrorist material.Footnote80 This presents challenges in terms of working with service providers to detect and remove harmful content as well as identifying and prosecuting perpetrators of these offenses. In this regard, an interviewed prosecutor of ERWT cases has confirmed experiencing difficulties proving beyond all reasonable doubt that an accused was the owner and operator of a relevant social media account when an anonymous identity and an overseas encrypted platform was employed to post content.Footnote81 In order to obtain admissible evidence from these platforms, prosecutors are required to submit mutual assistance requests to the relevant country in which they are based. These take a number of months to process, causing substantial delays to investigations and prosecutions. While the U.K. Parliamentary Intelligence and Security Committee has recently acknowledged that international cooperation is key to tackling ERWT more work needs to be done to establish international cooperation partnerships in order to expedite the sharing of relevant information necessary to facilitate the prosecution of ERWT individuals for these terrorism offenses.Footnote82

Preparation of Terrorist Acts:Section 5TA 2006

Since 2007 13 individuals motivated by right-wing ideology have been convicted of 13 separate offenses of planning acts of terrorism under section 5 TA 2006. This offense, designed to enable intervention to the activities of possible terrorists at a very early stage, is one of the most serious precursor offenses introduced by the 2006 Act, carrying a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. It is committed if an individual intends to either commit or to assist acts of terrorism and “engages in any conduct in preparation for giving effect to [this] intention.”Footnote83 None of the 13 individuals who were convicted of the section 5 offense were assisting others to commit acts of terrorism. Some had affiliations with far-right organizations, but they were not planning acts of terrorism as part of a conspiracy or a terrorist cell, and therefore all were acting on their own.Footnote84

In some of these cases the prosecution were able to establish the constituent elements of the offense by presenting evidence corroborating a connect between the defendants indorsement of extreme right wing ideological or racial causes and items found in their possession consistent with preparation of chemical related attacks or attacks to be perpetrated with specific weapons.Footnote85 The majority of cases, however, concerned the possession of IEDs or of materials consistent with their production. Martyn Gilleard was convicted and sentenced in 2008 for 16 years imprisonment in connection with possession of homemade nail bombs, as well as weapons and ammunition.Footnote86 Ian Forman received a sentence of 10 years in 2013 in connection with a similar plan to attack Mosques with explosive devices that he was preparing at his home.Footnote87 The same year, Pavlo Lapshyn was convicted of the offense connection with planned nail bomb attacks planted outside Mosques in the Midlands.Footnote88 Others had yet to make explosive devices but had acquired materials for their assembly. Ethan Stables was sentenced to an indefinite hospital order in 2018 after planning to carry out a bomb attack at a local gay pride event.Footnote89 More recently, Jack Reid became the youngest person in the U.K. to the be convicted of the offense in 2019 at the age of 16 following an attempt to obtain ingredients to make explosives.Footnote90

Commentators have expressed concern over a reliance on the judgment of counter-terrorism experts to identify what conduct will or will not be sufficiently wrongful to warrant prosecuting an individual with this offense, a criticism which is supported by questionable decision-making in a number of cases concerning ERWT suspects.Footnote91 In 2008 Nathan Worrell, for example, was found in possession of right- wing materials and Nazi memorabilia as well as instructions on how to make IEDS.Footnote92 He had also experimented with the manufacture of a time-delay mechanism. The facts of this case are not dissimilar to those concerning Peter Morgan who was arrested when bomb-making equipment was discovered in his possession. Neither Worrell nor Morgan had constructed an IED, but they had in their possession instructions on how to make them and items associated with their construction. In both cases also neither party had identified specific targets, although investigators had found evidence of support for right-wing ideological causes. Morgan was convicted of the section 5 offense in 2018 and sentenced to 12 years imprisonment. Worrell, however, was tried and convicted of a lesser offense under section 57 TA 2000. Nevertheless, on sentencing Worrell the trial judge confirmed that the facts of the case established that Worrell “intended to use some of the items for terrorist purposes,”Footnote93 suggesting that a case could certainly have been made that he was engaging in conduct with the intention of preparing to commit an act of terrorism, pursuant to section 5 TA 2006. Given the similarity of the facts of both cases and the conduct of the offenders, it is difficult to reconcile the decision of counter-terrorism experts to prosecute Morgan, but not Worrell, for the section 5 offense. It points to a change in perspective amongst counter-terrorism experts between 2008 and 2018 over the threat that the far-right milieu posed to national security, resulting in individuals being charged and prosecuted for more serious offenses where possible by the time of Morgan’s conviction. It points to selective criminalization of individuals based on the threat landscape of the type of terrorist ideation to which they are connected.

A similar concern over selective prosecution of the section 5 offense arises in the matter concerning Ryan McGee. A supporter of the EDL and a serving solider in 2013, McGee had written of murdering immigrants and was found to be in possession of IED at the time of his arrest. He had gone further than Morgan with his activities with explosives in that he had actually constructed an IED. However, the CPS decided not to prosecute McGee for a terrorist preparation offense on the basis that it was satisfied that he had no “intention to use the device for any terrorist or violent purpose, and that he had no firm intention to activate the device.”Footnote94 No further information was provided to explain how the CPS had reached this decision. A suspect’s intentions will be determined from a range of evidence, including their testimony, the activities in which they were engaged and the extent to which their behavior was directed toward realizing what is indicative of their ambitions. The offense entitles “any conduct” to be taken into consideration, allowing for a very broad interpretation of the acts which might be considered as amounting to preparatory activity. However, the proposition that the acts which are indicative of these intentions can only be correctly determined by counter-terrorism experts, and consequently not by the members of the public, risks violating the established rule of law principle of maximum certainty that requires laws to be sufficiently precise to the public to enable them to make coherent decisions about how they conduct themselves. Furthermore, any over-reliance on the administrative discretion of executive experts to prosecute select individuals for the section 5 offense and uncertainty over the application of their discretionary powers induces claims of discriminatory practices. Notably, following the sentencing of McGee, legal representatives of Mohommod Nawaz, who had been convicted of a terrorism offense in relation to religiously-inspired activities, complained of a discriminatory system lacking in transparent decision-making.Footnote95 In addition, an interviewed expert cited the McGee case as an example of an unconscious bias that in their experience existed amongst both juries and the judiciary which results in leniency in decisions to prosecute, convict and sentence individuals inspired by right-wing ideology as opposed to those associated with Islamist-inspired terrorism.Footnote96 Ultimately, the cases concerning Worrell and McGee serve as a warning to legal authorities to avoid practices when investigating ERWT suspects for the commission of an offense under section 5 capable of being construed as discriminatory and underpinned by dispositions toward selective prosecution of individuals for the offense.

Proscription and Membership: Sections 3 and 11 TA 2000

Current procedures entitle the Secretary of State for the Home Department to exercise his or her discretion and proscribe an organization if it is “concerned in terrorism.”Footnote97 An organization will be deemed to have satisfied this test if it “commits or participates in acts of terrorism, prepares for terrorism, promotes or encourages terrorism, or is otherwise concerned in terrorism.Footnote98 Once an organization is proscribed, further criminal offenses can be triggered under section 11 TA 2000 involving belonging to and inviting support for the organization, expressing an opinion supporting it, and wearing clothing or publishing images, flags and logos indicating support for it.

The proscription measures were first developed in response to the threat of terrorism in Northern Ireland. Academics have questioned their adaptability to other forms of terrorism. Their impact on Islamist terrorism has been limited. However, they have proved relevant for countering ERWT. Since the proscription of National Action in 2016 successive Secretaries of State have exercised their discretion to proscribe 7 additional right-wing organizations.Footnote99 Their decision-making has been underpinned by a number of symbolic, political and motivations. At the symbolic level, the banning of ERWT groups serves to counteract critical assessments of proscription practices seeking to highlight discrimination and bias toward banning Islamist groups and organizations connected to the conflict in Northern Ireland. At the political level, it offers a measure of reassurance to the electorate on which the governments have depended for their political survival that they are capable of responding to the threats that right-wing groups present to national security. In this respect it was not until Jo Cox MP was murdered by a National Action supporter that the U.K. government felt compelled to reevaluate its threat assessment of right-wing organizations and the efficacy of employing proscription powers to disrupt their threat capability. Prior to this, its threat assessment characterized the violent far-right milieu as populated by individuals largely acting alone rather than as part of any broader organized network capable of presenting a security risk. Information from the data set reveals that successive governments between 2007 and 2015 underestimated the radicalizing influence of ERWT organizations in existence at the time on those who were committing terrorist offenses. Half of the individuals who were convicted of terrorism offenses during this period, before the banning of NA, had affiliations with right-wing neo-Nazi organizations.Footnote100 If the warning signs of this pattern of terrorist offending had been fully evaluated at the time, more political pressure may have been applied to the U.K. government to exercise its powers to proscribe right-wing organizations before 2016.

At the practical level, proscription measures offer a means of reducing the radicalizing impact of those groups that have been banned by preventing their recruitment of new members and continued dissemination of online propaganda. Requests to overseas internet providers to remove material produced by right-wing groups are more likely to be persuasive if the government has invoked its powers under section 3 TA 2000 and banned them.Footnote101 The measures also entitle authorities to prosecute individuals for membership and expressing support for the organization.

Following the proscription of NA, at least 27 individuals have been arrested on suspicion of being a member of the group, 21 people have been charged with terrorism offenses and 17 have been convicted of the offense under section 11.Footnote102 While these convictions suggest that existing proscription measures are an effective means of combatting ERWT and reducing the radicalizing influence of those individuals connected to them, there are concerns that their impact may be little more than marginal, or worse, counterproductive. Media attention to the banning of organizations and the trials, convictions and sentencing of individuals for membership offenses provides valuable publicity for the hateful and extremist rhetoric that they are trying to promote. Furthermore, the banning of organizations can drive right-wing extremists underground and render their activities more difficult for domestic intelligence agencies to investigate.Footnote103

Perhaps more significantly ERWT attacks that have occurred in the U.K. have all been conducted by individuals acting alone rather than under the auspices of any particular organization.Footnote104 Self-initiated terrorists (S-ITs) associated with the far-right continue to pose a greater threat to security than networked groups.Footnote105 The dataset reveals that 65 percent of Extreme Right-Wing Terrorists who were convicted of terrorism offenses between 2007 and 2022 were acting alone. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that approximately 20 percent of these individuals had a connection at some stage with a proscribed organization, far-right political party, or street movement occupying space in the far-right landscape in the U.K.

Existing proscription powers have impacted on ERWT activity in the U.K. However, as Roach rightly points out, the value of proscription orders are undermined when former members of banned groups re-organize under the egis of newly-named entities, and continue to associate and exchange documents and images.Footnote106 To combat this, it is recommended that legal authorities enhance the impact of existing proscription measures by utilizing supplementary interventions, such as those available under the Policing and Crime Act 2009. This enables the court to issue, on application by the police, injunction orders preventing individuals within a group of three or more individuals from associating in public with other members, being in a particular place, wearing specified articles of clothing and using the internet to promote the activities of the group and to facilitate or encourage violence. Prohibitions can carry a power of arrest and breaches are considered a civil contempt of court, punishable by up to 2 years in prison and/or an unlimited fine. Employing these measures alongside proscription powers may prove effective as part of a process of developing broader strategic responses to counter the radicalizing influence of ERWT groups.

Conclusion

A prevailing narrative in leading scholarship that counter-terrorism legislation develops in response to new threats to national security is not supported by responses to date to the threat of ERWT activity in the U.K. Unlike responses elicited by political violence in Northern Ireland and Islamist-based terrorism, ERWT has not yet resulted in the introduction of any legislative counter measures.

The findings from this study support a conclusion that the rationale for this legislative stasis can be located in the adaptive nature of existing substantive terrorism-related offenses. Over the last 15 years, 70 Extreme Right-Wing Terrorists have been convicted of in excess of 200 counts of terrorist offenses contained in legislation enacted in 2000 and 2006 to disrupt Northern Ireland and Islamist-based terrorism. The significant impact of these offenses in countering ERWT has important implications for both national and international counter terrorism strategies. At the international level, the U.K.’s reliance on eight specific terrorism offenses for all ERWT convictions over the last 15 years should have resonance for other states that are critically examining the adaptive potential of their domestic law to countering surges in ERWT threats to security. At the domestic level, the reliance on existing terrorism offenses to counter ERWT implies that the extensive armory of extant counter-terrorism laws is such that the U.K. now possesses all the legislative weapons that it requires to combat new types of terrorist threats to security.

While the examined offenses have proved to be adaptive, question marks remain, however, over the impact of both terrorist financing legislation and proscription measures on ERWT. The former has been relevant for the conviction of only one individual associated with far-right ideologies to date. The latter has led to the banning of far-right organizations and the convictions of a number of individuals for membership offenses. Nevertheless, the majority of ERWT offenses in the last 15 years have been committed by individuals acting alone. Other types of injunctive interventions, such as those available under the Policing and Crime Act 2009, should be utilized in conjunction with proscription powers to disrupt the activities of individuals connected with ERWT organizations.

In addition to proposing improved application of complementary powers, this analysis of the applicability of existing terrorism offenses to ERWT reveals a number of concerns that should be addressed to enhance their impact in countering terrorism. As we have seen, the collection of information offense under s 58 TA 2000 has been highly relevant to countering ERWT activity. Yet the practical utility of this offense for protecting society is undermined when it remains all too easy for private commercial online companies to continue to profit from the sale of publications to individuals who are likely to be found guilty for possessing them, irrespective of their vulnerability due to mental health issues. Furthermore, the timely prosecution of individuals for disseminating terrorist publications and encouraging terrorism under sections 1 and 2 TA 2006 is being impeded by delays in obtaining admissible from overseas encrypted online platforms.

This analysis also exposes exercises in prosecutorial discretion that appear to broaden the scope of some terrorist offenses beyond their original purpose, and practices that risk contravening the principle of legal certainty. The existence of a database that is only available to the police and not the public places the executive at an unequal advantage in terms of understanding what information is likely to come within the scope of the s 58 TA 2000 offense. Similarly, the questionable prosecution of some individuals associated with ERWT but not others for the offense under section 5 TA 2006 suggests that only counter terrorism experts are capable of understanding the scope of the offense and what of “any conduct” is likely to be interpreted as preparing for an act of terrorism.

The broad ambit of existing terrorism offenses has ensured that they have been equally applicable to ERWT as to Northern Ireland Islamist-based terrorism, which they were introduced to counter. It underpins their adaptivity, applicability to ERWT and the legislative stasis that has characterized the U.K.’s recent response to ERWT to date. Yet the existing counter terrorism legal framework must remain under a continuous process of review to address challenges to its legitimacy, efficacy and impact in countering ERWT and other forms of terrorist threats to security in the U.K., which may inevitably result in further episodes of spiraling reform in the future.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest is reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 I adopt the same definition of extreme right-wing terrorism as that approved by the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament, namely that it refers to ‘the segment of the far-right movement involved in politically motivated violence’ and includes cultural nationalism, white nationalism and white supremacist ideologies. See Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament, “Extreme Right-Wing Terrorism,” July 13, 2022, available at https://isc.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/E02710035-HCP-Extreme-Right-Wing-Terrorism_Accessible.pdf

2 Counter Terrorism Policing, December 9, 2021, available at https://www.counterterrorism.police.uk/latest-home-office-statistics-reveal-7-late-stage-plots-foiled-since-march-2020/

3 Johnathan Hall, Q.C., Report of the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation on the Operation of the Terrorism Acts 2000 and 2006, and the Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Act 2011, July 6, 2022.

4 Laura Donohue, The Cost of Counterterrorism: Power, Politics and Liberty, Cambridge University Press 2008.

5 Laura Donohue, Counter-terrorist Law and Emergency Powers in the United Kingdom 1922-2000 (Dublin, Irish Academic Press, 2001).

6 Scott A. Bonn, Mass Deception: Moral Panic and the U.S. War on Iraq (Rytgers University Press, 2010).

7 For example, Jessie Blackbourn, “Counterterrorism legislation and far-right terrorism in Australia and the United Kingdom,” Common Law World Review 50, no.1 (2021):76-92; David Lowe, “Far-Right Extremism: Is It Legitimate Freedom of Expression, Hate Crime, or Terrorism? Terrorism and Political Violence,” Terrorism and Political Violence, (2020); Lucia Zedner, “Countering terrorism or criminalizing curiosity? The troubled history of UK responses to right-wing and other extremism,” Common Law World Review, 50, no.1 (2021): 1-19.

8 A/RES/75/291 June 30, 2021.

9 UNODC, “Manual on the Prevention of and Responses to Terrorist Attacks on the Basis of Xenophobia, Racism and Other Forms of Intolerance, or in the Name of Religion or Belief,” July, 2022 available at https://www.unodc.org/documents/terrorism/ManualXRIRB/UNODC_Manual_on_Prevention_of_and_Responses_to_Terrorist_Attacks_on_the_basis_of_XRIRB.pdf (accessed July, 2022).

10 Sarah Lee, “London Nail Bombings Remembered 20 years On,” BBC News, April 30, 2019 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-47216594 (accessed July 2022); R v David Folley [2013] EWCA Crim 396.

11 BBC News, “Ex-BNP man jailed over chemicals,” July 31, 2007; Press Association, “BNP member given 11 years for making bombs and guns,” The Guardian, January 15, 2010.

12 This includes an arson attack on a mosque in Grimsby in 2013, Darren Osborne’s vehicle attacks on a crowd outside Finsbury mosque in north London in 2017, attacks on worshippers in Bradford in 2018 and east London in 2019, and plans to attack mosques in Walsall, Aberdeen and Fife.

13 BBC News, “Gloucester Mosque Attack: Two Men Jailed,” November 21, 2013.

14 UK Home Office, “Fact sheet: Right-wing terrorism”, March 19, 2019, https://homeofficemedia.blog.gov.uk/2019/03/19/factsheet-right-wing-terrorism/ (accessed February, 2022).

15 Steven Morris, “Nazi-obsessed loner guilty of attempted murder of dentist in racist attack,” The Guardian, June 25, 2015.

16 BBC News, “Neo-Nazi pipe bomb teenager admits terror offence,” July 16, 2018.

17 The Guardian, “Far-Right Terror Detentions Rise Fivefold Since Jo Cox Murder,” September 16, 2018.

18 Vikram Dodd, “Finsbury Park attack: man ‘brainwashed by anti-Muslim propaganda’ convicted,” The Guardian, February 1, 2018.

19 R v Jack Renshaw, Sentencing Remarks of Mrs Justice McGowan, May 17, 2019.

20 Home Office, “Individuals Referred to and Supported Through the Prevent Programme, April 2018 to March 2019’” (2019); Vikram Dodd and Jamie Grierson, “Fastest-growing UK terrorist threat is from far-right, say police,” The Guardian, September 19, 2019.

21 David Ibsen et al, “Violent Right-Wing Extremism and Terrorism – Transnational Connectivity, Definitions, Incidents, Structures and Countermeasures,” Counter Extremism Project, November 2020, p. 5-6.

22 Melissa Eddy, “Far-Right Terrorism Is No. 1 Threat, Germany Is Told After Attack,” The New York Times, February 21, 2020.

23 “Right-wing terror in Germany: a timeline,” Deutsche Welle, February 20, 2020.

24 Mark Daalder “NZ left behind as Australia designates far-right group,” Newsroom, April 8, 2021.

25 Seth G. Jones and Catrina Doxsee, “The Escalating Terrorism Problem in the United States,” June 17, 2020, Centre for Strategic International Studies, https://www.csis.org/analysis/escalating-terrorism-problem-united-states (accessed April 2022).

26 For example, John B. Bell, A Time of Terror: How Democratic Societies Respond to Revolutionary Violence (New York: Basic Books, 1978); Philip Thomas, Emergency Terrorist Legislation Journal of Civil Liberties (1998): 240-49; Philip Thomas, Legislative Responses to Terrorism in Beyond September 11: An Anthology of Dissent, ed. Phil Scraton (Pluto Press, 2002), 93-101; Laura Donohue, The Cost of Counterterrorism: Power, Politics and Liberty, Cambridge University Press 2008; Elena Pokalova Legislative Responses to Terrorism: What Drives States to Adopt New Counterterrorism Legislation? Terrorism and Political Violence 27, no.3 (2015): 474-96; Mariaelisa Epifanio and Todd Sandler, Legislative response to international terrorism, Journal of Peace Research 48 no.3, (2011): 399-411; Victor Ramraj et al, Global Anti-Terrorism Law and Policy (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

27 Jessie Blackbourn, “The UK’s Anti-terrorism Laws: Does Their Practical Use Correspond to Legislative Intention?” Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism 8, no.1 (2013): 19-34, 20.

28 The Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, the Terrorism Act 2006, the Counter- Terrorism Act 2008, the Terrorist Asset-Freezing Act 2010, for example, have been guided by 2002 and 2008 EU Framework Decisions on counter-terrorism law and shaped by requirements of UN Security Council Resolutions, including 1371 and 1624.

29 The Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Act 2019, the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill 2021, and the Counter Terrorism and Sentencing Act 2021.

30 For example, Clive Walker, Blackstone’s Guide to Anti-Terrorism Legislation, (Oxford University Press, 2014); Blackbourn, “The UK’s anti-terrorism laws;” Keith Syrett, The United Kingdom in Comparative Counter-Terrorism Law, ed. Kent Roach (Cambridge University Press, 2015), 167-202.

31 See Dermot P.J. Walsh, The Use and Abuse of Emergency Legislation in Northern Ireland, London: Cobden Trust, 1983) Phil Edwards, “Counter-Terrorism and Counter-Law: An Archetypal Critique,” Legal Studies 38 (2018): 279-297; Paul Wilkinson, Terrorism and the Liberal State (London: Halstead, 1977); Victor Tadros, “Justice and Terrorism,” New Criminal Law Review 10, no.4 (2007):658-689; Andrew Cornford, “Terrorist Precursor Offences: Evaluating the Law in Practice,” Criminal Law Review 8 (2020): 663-685; Donohue, “The Cost of Counterterrorism.” Sangeeta Shah, “The UK’s anti-terror legislation and the House of Lords: The first skirmish,” Human Rights Law Review, 5 no. 2 (2005): 403-421.

32 Paddy Hilyard, “Soapbox The Prevention of Terrorism Act,” Irish Studies Review 1, no. 3 (1993):43-44, 43; Colm Campbell, “Wars on Terror and Vicarious Hegemons: The UK, International Law, and the Northern Ireland Conflict,” Int’l & Comp. L. Quarterly, 54 (2005): 321.

33 Helen Fenwick, “Reconciling international human rights law with executive non-trial-based counter-terror measures: the case of UK temporary exclusion orders,” in The Rule of Crisis: Terrorism, Emergency Legislation and the Rule of Law ed. Pierre Auriel, Olivier Beaud, Carl Wellman (Springer International Publishing, 2018), 121-156; Donohue, “The Cost of Counterterrorism.”

34 Michael J. Piaseczny, ‘The determinants of differing legislative responses in similar States: A Nordic Case Study,’ Mapping Politics (2018).

35 John Ip, “Law’s Response to New Zealand’s ‘Darkest of Days,” Common Law Review, 50, no. 1, (2021): 32.

36 Jessie Blackbourn, “The UK’s Anti-terrorism Laws: Does Their Practical Use Correspond to Legislative Intention?” Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism 8, no.1 (2013): 19-34.

37 Individuals may be sentenced for these offences on the basis that they have a terrorist connection by virtue of section 2 Counter Terrorism Act 2008.

38 Claudia Patatas and Alice Cutter.

39 They may have been in communication with others but were acting on their own volition and not in conjunction with those others or as part of any conspiracy.

40 Section 1 Terrorism Act 2006.

41 Section 2 Terrorism Act 2006.

42 Section 5 Terrorism Act 2006.

43 Section 57 Terrorism Act 2000.

44 Section 58 Terrorism Act 2000.

45 Section 11 Terrorism Act 2000.

46 Section 15 Terrorism Act 2000.

47 Schedule 7 entitles the police to interrogate, search and detain a suspect for up to 6 hours at a port in the UK to determine if they are involved in the preparation, instigation or commission of a terrorist act.

48 The potential for online viewing of material was added in 2019 by the Counter-Terrorism and Border Security Act 2019.

49 Section 58(3A)(a) Terrorism Act 2000.

50 The Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1973 and the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.

51 Cornford, “Terrorist Precursor Offences.”

52 R v G, R v J [2010] 1 A.C 43. In R v K [2008] EWCA Crim 185.

53 James Lynn, “Ricin Proved neo-Nazi Ian Davison ‘was serious,” BBC News, May 14, 2010.

54 “Terror plotter Mark Colborne detained indefinitely,” BBC News, December 22, 2015.

55 “Banff Man Conor Ward jailed for terrorism offences,” BBC News, April 12, 2018.

56 Two Years in Jail for Far-right Extremist who downloaded terror manuals,” East Lothian Courier, October 4, 2019.

57 Jonathan Hall Q.C., “The Terrorism Acts in 2019, Report of the independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation on the Operation of the Terrorism Acts 2000 and 2006,” March 2021, para 7.66

58 Interview with prosecutor, March 2022.

59 Cornford, “Terrorist Precursor Offences.”

60 Richard Ericson, “Rules in policing: Five perspectives’” Theoretical Criminology 11, no. 3, 368; R v Brown [2011] EWCA Crim 2751.

61 G [2009] UKHL 13 at 79; R v A(Y) [2010] 2 Cr. App. R 15.

62 Cornford, “Terrorist Precursor Offences.”

63 Interview with prosecutor, March 2022.

64 Ibid.

65 R v John [2022] EWCA Crim 54 at 11.

66 R v Dunleavy [2021] EWCA Crim 39 at 13;

67 R v Dunleavy at 14.

68 Vikram Dodd, “Soldier Jailed for Making Nail Bomb avoids terror charge,” The Guardian, November 28, 2014.

69 R v Bel [2021] EWCA Crim 1461 at 15.

70 R v Golaszewski [2020] EWCA Crim 1831 at 3

71 Ibid.

72 The prosecution is not required to prove a terrorist purpose to secure a conviction under s 58. See R v G, R v J [2010] 1 A.C. 43.

73 Martin Wainwright, “Neo-Nazi Ian Davison jailed for 10 years for making chemical weapon,”The Guardian May 14, 2010.

74 R v Bel [2021] EWCA Crim 1461 at 15.

75 “G7 Taormina Statement on the Fight Against Terrorism and Violent Extremism” (2017): 1-3 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/23562/26-g7-statement-fight-against-terrorism-and-violent-extremism.pdf (accessed May 2022).

76 Edwards, “Counter-Terrorism.”

77 “Pair jailed for inciting copycat terror attacks,” BBC News, October 23, 2019.

78 “Man Jailed for threatening to burn down Mosque,” BBC News, December 2, 2021.

79 “Michael Nugent: man’s jail term increased for ‘extreme’ online material,” BBC News,

October 22, 2021.

80 Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament, “Extreme Right-Wing Terrorism,” 105-111.

81 Interview with prosecutor, March 2022.

82 Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament, “Extreme Right-Wing Terrorism,” 117.

83 Section 5(1) Terrorism Act 2006.

84 Stables was associated with National Action; Morgan with the Scottish Defence League; Dunleavy with the Feuerkrieg Division; Gilleard and Lewington with National Front and Blood and Honour.

85 Mark Colborne plotted a mass cyanide attack in 2014; Jack Renshaw planned to attack Rosie Cooper MP with a machete in 2017. Paul Dunleavy was convicted of one count of the offence in 2020 following a discovery of weapons and ammunition at his home; and in 2021 Matthew Cronjager was convicted of the offence following an attempt to obtain a 3D printed gun or sawn-off shotgun.

86 “Nazi sympathiser jailed for planned nail bomb attacks,” The Guardian, June 25, 2008.

87 Helen Pidd, “Neo-Nazi terrorist jailed for plotting to blow up Merseyside mosques,” The Guardian May 1, 2014.

88 Vikram Dodd, “Pavlo Lapsyhn jailed for 40 years for murder and mosque bombs,” The Guardian October 25, 2013.

89 Frances Perraudin, “Man found guilty of planning terror attack on Cumbria gay event,” The Guardian, February 5, 2018.

90 Daniel de Simone, “Terror plot: Durham teenage neo-Nazi named as Jack Reed,” BBC News, January 11, 2021.

91 Edwards, “Counter-Terrorism and Counter-Law,” 292; Helen Fenwick and Gavin Phillipson, “UK counter-terror law post 9/11: initial acceptance of extraordinary measures and the partial return to human rights norms,” in Global Anti-Terrorism Law and Policy, ed. Victor V Ramraj (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 481-513, 507.

92 R v Worrell [2009] EWCA Crim 1431.

93 Ibid, at para 7.

94 Vikram Dodd, “Solider jailed for making nail bomb avoids terror charge,” The Guardian, November 28, 2014.

95 Ibid.

96 Interview with prosecutor, March 2022.

97 Section 3 Terrorism Act 2000.

98 Section 3(5) Terrorism Act 2000.

99 Atomwaffen, The Base, Sonnenkrieg Division and Feuerkrieg Division. Further orders have been made in relation to three other organisations as affiliations of National Action - NS131, Scottish Dawn and System Resistance Network.

100 These include Blood and Honour and Aryan Strike Force.

101 Hall, “The Terrorism Acts in 2019,” 39.

102 Ibid, 38.

103 Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament, “Extreme Right-Wing Terrorism,” 98.

104 Benjamin Lee, “Overview of the Far-Right Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats,” Commission for Countering Terrorism, 2019): 10-11

105 The UK Parliament now refers to lone actors as ‘self-initiated terrorists.’ See Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament, “Extreme Right-Wing Terrorism,” 29; Clare Ellis, Raffaello Pantucci, Jeanine de Roy van Zuijdewijn, Edwin Bakker, Benoit Gomis, Simn Paolmbi and Melanie Smith, “Lone-Actor Terrorism: Final Report” (London: RUSI, 2016).

106 Roach, “Counterterrorism,” 8.