Abstract

Is socioeconomic marginalization associated with the radicalization of European foreign fighters? I analyze biographical data on 1019 foreign fighters from France, Germany, and the United Kingdom and compare their level of education and unemployment rate with those of the population most at risk of radicalization, namely the young male Muslim population within the respective country. Overall, the results indicate that compared to the population at the highest risk of radicalization, foreign fighters do not appear to be disproportionately socioeconomically deprived. An analysis of survey data on support for foreign fighters conducted among the Muslim minority in Germany further underlines these findings.

Various authors have highlighted problems related to the socioeconomic integration of Muslims in the European context, identifying these as the major root cause behind violent radicalization.Footnote1 For instance, discussing Islamist radicalism among Muslim minorities in Britain, Abbas argues that “it is the nature of social disintegration and economic polarities which fuels conflict and discontent among […] poor disaffected alienated young minorities.”Footnote2 Similarly, numerous studies on European foreign fighters reviewed by Dawson and Amarasingam “conclude that those leaving appear to be mainly marginalized individuals with limited economic and social prospects, who are experiencing various kinds of frustration in their lives.”Footnote3 These observations are echoed by journalists and politicians alike.Footnote4 For instance, John Kerry declared in 2014 that the United States had a vast interest in combating poverty, since poverty was considered to be the primary driver for terrorism.Footnote5 Security agencies across Europe have also identified socioeconomic deficits as major barriers to deradicalization and counter-terrorism efforts and thus urgently called for proactive improvement.Footnote6 This study contributes to these debates by investigating whether and to what extent socioeconomic marginalization is associated with the radicalization of European foreign fighters.

There is strong evidence that European Muslims with immigrant backgrounds indeed face disadvantages in education, access to the labor market, and occupational attainment.Footnote7 However, empirical inquiries into the relationship between economic conditions and radical behavior have so far failed to deliver conclusive and robust evidence.Footnote8 Early studies assessing the biographical characteristics of perpetrators found that participation in terrorist activities is largely independent of economic conditions.Footnote9 In contrast, recent scholarship based on European cases suggests an association between both low educational levels and weak labor market integration of European Muslims, and participation in political violence.Footnote10 However, this body of literature is characterized by a number of limitations.

First and most importantly, comparisons with a relevant control group are largely absent in these studies. When investigating the socioeconomic characteristics of foreign fighters, previous studies have generally only reported the distribution within their sample or compared their findings with trends in the general population.Footnote11 They highlight differences between their sample and the general population across these variables and conclude that these deficits are associated with radicalization. However, I argue that more meaningful results can be obtained by considering a comparison with trends among the population with the highest risk of radicalization, namely men aged 18 to 30 with a migration background from a Muslim-majority country. Without a relevant comparison group, it is not possible to determine whether the observed discrepancies simply reflect trends of socioeconomic marginalization among the Muslim migrant population, or whether the sampled foreign fighters are in fact over-represented within the economically disadvantaged segments of the relevant control group.

Second, these studies have not taken Wiktorowicz’s observations into account, which suggest that, in some cases, individuals may be economically marginalized because of their religious activism and not the other way around.Footnote12 Arguably, these cases can bias the findings and lead to an overestimation of the share of those without employment or educational qualifications. Third and finally, these studies draw their conclusions from small samples and case studies. To date, the largest sample can be found in a report published by the German security agencies, studying 784 foreign fighters from Germany. This is followed by a study investigating the characteristics of a total number of 370 Belgian and Dutch foreign fighters. Moreover, existing studies consider a maximum of two country cases only.Footnote13 These issues raise questions about the generalizability of their findings. In this study, I analyze biographies of over 1000 foreign fighters from three different countries, making it the largest sample of its kind to date. Moreover, I draw on original survey data from Germany to further examine whether socioeconomic determinants are associated with support for foreign fighters among Muslim respondents within a West European context. To my knowledge, so far, no study has explored attitudes toward foreign fighters using survey data.

To investigate the role of socioeconomic integration in Jihadi radicalization, I use original biographical data on foreign fighters from three European countries. I focus on France, Germany, and the U.K., since these countries were the top three European countries of origin of foreign fighters active in Syria and Iraq.Footnote14 It is estimated that more than 1000 foreign fighters have left France to fight for or otherwise support militant Islamist groups in Syria and Iraq, while more than 700 fighters departed from Germany and the U.K. each.Footnote15 These numbers illustrate how these countries were especially affected by Islamist mobilization in Europe. Accordingly, questions regarding the drivers behind this mobilization have been central in public debates and policy discussions within these countries.Footnote16 I complement the biographical data with findings from a survey study conducted among German Muslims in 2016 (n = 516). Survey data enables researchers to grasp the mobilization potential of certain movements –in this case the Jihadi foreign fighter movement– among a reference population i.e. the Muslim population in Germany.Footnote17 Those who take a positive stance regarding the goals of the Jihadi foreign fighter movement are also more likely to become actively engaged in activities of this movement. By conducting regression analyses of the survey data, I investigate the effect of the socioeconomic variables on support for foreign fighters, while controlling for a range of demographic variables.

For the purpose of this study, I define “foreign fighters” as individuals who have traveled or attempted to travel to Syria, Iraq, or Afghanistan, or any other conflict region, and were motivated by an Islamist ideology. This broad definition includes individuals who were actively involved in armed combat, who have attended militant training camps, but also noncombatants, who, for instance, traveled with the aim of marrying a militant abroad (the so-called “Jihadi brides”). Accordingly, I identified and collected information on a total number of 565 foreign fighters, who traveled or attempted to travel to a conflict country between 2000 and 2016. I then generated profiles and coded detailed biographical and relational information on the foreign fighters using a codebook specifically designed for this research project. This data is presented in the Jihadist Radicalization in Europe (JRE) database. I identified another 454 foreign fighters in Brandeis University’s Western Jihadism Project database who fit the sampling criteria and integrated them into the JRE database.Footnote18 The resulting dataset consists of 1019 foreign fighters.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

Following the events of September 11, 2001, the proposed relationship between socioeconomic marginalization and radicalization was addressed empirically and, crucially, widely refuted by the academic literature.Footnote19 However, with the rise of foreign fighters in the European context starting in 2012, it reemerged as a central explanatory factor and continues to dominate both the academic and the public discourses. A key element in this debate is the challenge of socioeconomic integration: European Muslims from migrant backgrounds face disadvantages in education, access to the labor market, and occupational attainment.Footnote20 These discrepancies are often highlighted and posited as the major root causes of Muslim radicalization in Europe. The two most central variables related to socioeconomic grievances are economic deprivation and educational attainment.

Economic Deprivation

Many public figures and government officials have asserted a causal link between economic deprivation and radicalization and have called for the eradication of poverty in order to combat terrorism.Footnote21 Traditional economic approaches suggest that individuals who are economically well off are more likely to abide by the law and less likely to commit illegal or criminal activities.Footnote22 This is because such individuals with high-wages, “when choosing how to allocate their time between legal and illegal activities to maximize their utility, will presumably find better (and less risky) alternatives.”Footnote23 Since they also have more at stake, they are less likely to engage in criminal activities. According to this line of thought, having a higher income or a well-paying job likely discourages support for violent action, “because those who are more satisfied with life do not believe that drastic measures are necessary to bring about change.”Footnote24 Moreover, economic grievances are often characterized by the frustration of not being able to fulfill the culturally defined goals or widely accepted objectives of a given society. An example of which is the failure to properly integrate into the labor market, thereby violating an important societal expectation.Footnote25

Previous scholarship investigating the biographical characteristics of Jihadist perpetrators finds that participation in terrorist activities is mostly independent of economic conditions.Footnote26 For instance, Krueger and Malečková investigated the determinants of participation in Hezbollah militant activities and in Israeli Jewish terrorist groups, whereas Berrebi conducted an analysis of the perpetrators of Palestinian terrorist attacks in Israel.Footnote27 Both studies compared violent activists to a nonviolent control group and concluded that economic deficits alone cannot explain engagement in political violence.

Notwithstanding, with the rise of the phenomenon of foreign fighters in the European context, socioeconomic explanations for radicalization have reemerged. Numerous investigations of biographies of Western foreign fighters have stressed the low economic prospects as significant “push factors” for the mobilization and recruitment of young Jihadists.Footnote28 For instance, Neumann argues that “(i)n Germany, Belgium, France and Scandinavia, a large majority come from deprived backgrounds and have neither school qualifications, professional training nor any prospect of a decent job.”Footnote29 Despite acknowledging that “socioeconomic characteristics alone do not explain the phenomenon of Jihadist foreign fighters,” Bakker and de Bont find that the disadvantaged societal position of young Belgian and Dutch Muslims holds significant explanatory value.Footnote30 Drawing on insights from the Belgian case, Coolsaet discusses extensively the economic inequalities and lack of job prospects as important explanatory factors.Footnote31

However, studies of this kind are limited due to their sampling bias. Sampling only on the dependent variable, they lack a control group or a counterfactual. Reynolds and Hafez attempted to address this deficiency by comparing the unemployment rate of German foreign fighters with available statistics on the rates of unemployment among Germans with and without migrant backgrounds.Footnote32 Their results suggest that, compared to the general German population with and without migrant backgrounds, German foreign fighters indeed have a disproportionately high unemployment rate. However, previous research shows that it is not the migrant population, but the young male Muslim population that is most at risk of radicalization in Germany.Footnote33I argue that this group should therefore be the relevant comparison group. As age-disaggregated data on the Muslim population is unfortunately largely unavailable in Germany, I instead use data on the general Muslim population. Without a relevant comparison group, it is not possible to determine whether the observed high share of unemployment simply reflects unemployment trends in the Muslim population or whether the foreign fighters are in fact disproportionately likely to be unemployed. If trends concerning certain characteristics of foreign fighters corresponded to the trends in the general Muslim population in Germany, then this would mean that foreign fighters are not substantially different from a random sample of that particular demographic group.Footnote34 In this case, these characteristics would not suffice to explain why individuals in the sample engage in radical behavior, whereas other individuals from the same demographic group with similar characteristics did not.

At this point, it is important to note that the assumed direction of causality between unemployment and radicalization could also be in the reverse direction. As Wiktorowicz observed, some activists in the radical Islamist organization al-Muhajiroun quit their jobs to be able to devote all their time and energy to religious activism.Footnote35 These so-called dawah activities include proselytizing, distributing the Koran in the streets, organizing public sermons, or picketing. In many cases, the same individuals later became involved in terror-related activities such as propaganda, recruitment, and terror plots or attacks. None of the studies investigating profiles of foreign fighters has, so far, taken into account whether the individuals were unemployed as a result of their radicalization instead of the other way around. Despite these considerations, my hypothesis mirrors those commonly stated in recent academic and public discourses, following the socioeconomic integration deficit theory:

Hypothesis 1: Compared to the population most at risk of radicalization, economically marginalized persons are over-represented among European foreign fighters.

Education

Another variable explaining Islamist radicalization processes that is popular in the public sphere but contested among academics is lack of education. In the public discourse, educational deficiencies are often highlighted as a possible driver of radicalization. According to this argument, “terrorism is caused in part by ‘ignorance’ […] and ignorance is associated with lack of education.”Footnote36 In line with this argumentation, various international organizations have promoted education programs as a means of tackling violent extremism.Footnote37 For these organizations, education is an effective intervention in countering radicalization, as it promotes civic competencies, critical thinking, and empathy, which are skills that can make individuals resilient to radical ideologies. Yet, despite its popularity in the media and among policymakers, the available empirical evidence does not demonstrate a clear relationship. Observational studies investigating attitudes toward religious violence or religious militant groups have so far mostly delivered inconclusive findings.Footnote38

Findings from biographical research on terrorism offenders have differed according to the country of study. Studies focusing on countries outside the West have pointed toward an inverse relationship, where higher-educated individuals are overrepresented in terrorist groups. For instance, drawing on samples from the Palestinian territories and Lebanon, Krueger and Malečková found that perpetrators of terrorism were on average better educated.Footnote39 In line with these findings, higher levels of education were found to be positively associated with participation in the case of Palestinian Islamic Jihad.Footnote40 A prominent study by Sageman on global Salafi jihad also found that ignorance does not play a significant role in radicalization: 62% of his sample attended university and the majority of them studied technical subjects.Footnote41 This finding has been further stressed by Gambetta and Hertog who demonstrated how subjects such as science, engineering and medicine are strongly over-represented among the university degrees held by members of the Islamist movements across the Muslim world.Footnote42

In contrast, recent studies focusing on European countries have found that Jihadists are often characterized by marked educational deficiencies and that these deficits play an important role in the radicalization process. For instance, Coolsaet identified the differences in educational attainment between young Belgian citizens with a non-European family background and the native population as a major risk factor for radicalization.Footnote43 Bakker reported that only a trivial minority (6%) of European Jihadists in his sample finished higher education.Footnote44 Lindekilde et al. identify the lack of competences and resources necessary for dealing with everyday tasks as the central driving force behind the radicalization of Danish foreign fighters.Footnote45 Reynolds and Hafez observed that German foreign fighters tended to perform below average in the German education system.Footnote46

Similarly, other authors have documented a large share of school or university dropouts among European foreign fighters.Footnote47 However, these accounts have not further explored why these individuals may have abandoned education. Paralleling the previously mentioned findings concerning employment status, some individuals may not have completed university degrees because they quit their studies to devote themselves to dawah activities. When comparing the average educational attainment of perpetrators with the average educational attainment of a reference group, such cases should be excluded from the analysis. However, the very few studies that have made such comparisons did not exclude these cases from their analyses. Considering these context-dependent differences, the lack of consideration for dropouts in previous analyses, and the prominence that the proposed association between education and radicalization enjoys in popular accounts, this relationship still requires further empirical examination. Moreover, the question of how radicalized individuals perform in terms of their educational qualifications compared to the population at highest risk of radicalization remains open.

Considering that the more recent literature in the European context supports the socioeconomic integration deficit theory, I test the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Compared to the population most at risk for radicalization, low educational qualifications are over-represented among European foreign fighters.

Bloc Recruitment

Arguably, Muslims with immigrant backgrounds living across different British, French, and German regions are similarly affected by socioeconomic deprivation and integration deficits. Therefore, if socioeconomic deprivation and integration deficits are an important factor in radicalization, then we should expect foreign fighter recruitment to be geographically dispersed –not clustered– across various regions.Footnote48 Moreover, if the socioeconomic deficit theory were true, the shares of foreign fighters stemming from different regions should differ proportionally with the shares of the Muslim populations residing in these regions. For instance, if 12% of the British Muslim population resides in Yorkshire and the Humber, then around 12% of the British foreign fighters should also originate from this region.

In contrast, the bloc recruitment theory contradicts the socioeconomic deficit hypothesis and predicts that “mobilization does not occur through recruitment of large numbers of isolated and solitary individuals. It occurs as a result of recruiting blocs of people who are already highly organized.”Footnote49 Particularly for high-risk/high-cost activism, e.g. terrorism, participants are expected to have a history of activism and to be integrated into activist and support networks, which act as the structural pull-factor that encourages individuals to take action.Footnote50

Previous research on the mobilization of terrorism offenders and foreign fighters from Europe generally confirms these observations made by social movement scholars. Most prominently, Sageman has extensively documented the importance of peer networks in the mobilization and recruitment processes of terrorism offenders.Footnote51 Similarly, Nesser has highlighted the crucial role of the Islamist extremist support networks in the strengthening of Jihadist militancy Europe.Footnote52 Concerning foreign fighters, Holman reported that two networks, the 19th and the Kari network, were responsible for sending the majority of the Belgian and French recruits to Iraq between the years 2003 and 2005.Footnote53 More recently, Kanol has documented the continued relevance of interpersonal and organizational networks in the radicalization of foreign fighters and found that the majority of foreign fighters were linked within a single social network prior to their mobilization.Footnote54 Reynolds and Hafez specifically investigated the role of bloc recruitment to test whether individuals radicalized primarily online or through interpersonal networks. They concluded that foreign fighters from Germany were geographically clustered, not diffused, and thus refuted the online radicalization hypothesis.Footnote55 Despite these recent findings, I formulate and test a version of this hypothesis as the socioeconomic deficit theory would predict:

Hypothesis 3: Given socioeconomic deficits, foreign fighters are geographically diffused and recruited from regions in line with the proportion of the Muslim populations residing there.

Data and Methods

Biographical Data

I use data on foreign fighters and noncombatant members of militant groups from France, Germany, and the U.K. to test my hypotheses. The data is drawn from the Jihadi Radicalization in Europe and the Western Jihadism Project databases. Detailed information on the two databases as well as the data collection procedures, and data resources used to compile them can be found in the Online Appendix 1.

The sample for this study consists of 327 foreign fighters from France, 322 from Germany, and 370 from the U.K. (). Unless specified otherwise, I use the term “foreign fighters” to refer to combatants and noncombatants in conflict areas as well as to those who have attempted to travel to a conflict country. 84% of the sample succeeded in reaching their destination and becoming foreign fighters, whereas 16% failed to reach their destination. The majority of those who failed were prevented from departing by security agencies. Many individuals were arrested at the airport, whereas others were arrested abroad in countries such as Turkey or Pakistan, as they attempted to cross the border to a conflict country or region and were deported. Some individuals also traveled or attempted to travel to multiple conflict countries. Given both the significant public attention shed on the most recent wave of foreign fighters active in Syria and Iraq and the centrality of this conflict in the academic literature, I analyze only the most recent travel attempt of those individuals who participated in multiple conflicts.

Table 1. Number of foreign fighters in the WJP- and JRE-databases across countries.

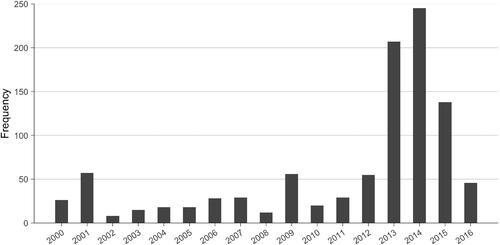

depicts the number of departures between 2000 and 2016. There are three identifiable waves of mobilization. The first peak in 2001 was connected to the events surrounding September 11. Some of the perpetrators visited al-Qaeda affiliated camps in Waziristan, the border region between Afghanistan and Pakistan, whereas others traveled to Waziristan just before or shortly after September 11. Waziristan was likewise the most frequent destination for foreign fighters from the second wave in 2009. Encompassing the period between 2012 and 2016, the third wave concerned the civil war in Syria and was by far the largest.

The main destinations for foreign fighters in the sample were Syria or Iraq (Levant).Footnote56 714 foreign fighters (70% of the sample) traveled to the Levant region, followed by 216 foreign fighters (21%) who traveled to Afghanistan or Pakistan (AFPAK). The insurgency in Somalia also attracted a small number of foreign fighters (43). Other conflict countries in this sample are, for instance, Mali, Libya, and Palestine.

Survey Data

A research company with local expertise was commissioned for the administration of the survey in Germany. A nationwide onomastic phone-book sample was used for computer-assisted-telephone-interviews by trained enumerators. Respondents had to be at least 18 years old to participate in the survey. Several quotas were used to ensure that different sociodemographic, ethnic, and denominational groups were adequately represented in the sample. Further detailed information on the survey design, sampling procedure, and methods can be found in the online data repository.Footnote57 Religious group membership was determined based on the self-identification of the respondents by answering the question ‘To which religion do you belong?’. A total number of 516 respondents identified as Muslim.

To measure respondents’ support for foreign fighters, they were asked to what extent they agreed with the statement: “Muslims who go to Syria and Iraq to fight to establish an Islamic State are heroes,” with the answer categories ranging from 1, completely agree, to 5, completely disagree. On average, respondents strongly disagreed with this statement (M = 4.3; SD = 1.0). I consider respondents whose answers were between one and three to be supportive of foreign fighters, the rest are considered not to be supportive. Based on this understanding, I generate a dummy variable, where 1, indicates support. Only a small share of around 16% of the respondents expressed support. To measure the effect of unemployment, respondents were asked whether they had a paid job in which they worked more than 15 h a week. 254 respondents (50%) stated that they were employed, 23 respondents (5%) stated that they were unemployed, and 230 respondents (45%) stated that they were not in the labor market (i.e. students, pensioners, caretakers etc.). To measure the effect of education, I ask for the respondents’ highest level of education. I recoded the seven possible answer categories into three groups: none or low level of educational attainment (186 respondents, 36%), middle level of educational attainment (235 respondents, 46%), and high level of educational attainment (89 respondents, 17%).

In the regression models, I control for age, gender, marital status, and conversion. Sample characteristics and information on the control variables can be found in the Online Appendix.

Demographic Data

Foreign fighters in the sample were predominantly male (87%). Only a minority of the sample was female (13%).Footnote58 Compared to previous studies and other databases, women were slightly under-represented in the sample.Footnote59 This may be due to the fact that these studies mainly examined foreign fighters who traveled to Syria and Iraq. In contrast to other militant Islamist groups involved in previous conflicts, the Islamic State has mobilized a considerably larger number of women. Scholars have pointed out how “entire families whose aim it is to settle down permanently” have traveled to Syria.Footnote60 Within my sample, looking at foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq only, the share of women lies at 17%, which corresponds roughly to the shares of women presented in previous studies.

86% of the sample had a migration background, meaning at least one parent had origins outside the country of residence. In most cases, the press reports stated whether an individual had a migration background or not. In other cases, I was able to identify whether an individual had a migration background or not using his or her name and surname. By means of this process, I was able to determine whether or not an individual had a migration background for 98% of the cases. The share of foreign fighters with a migration background was the highest in the U.K. (96%).

209 individuals in the sample (21%) did not grow up in a Muslim family but converted to Islam at a later stage of their life. There were marked differences between the three countries regarding the share of converts. The French sample had the highest share of converts, namely 27% of the sample having converted to Islam. In contrast, the share of converts in the British sample was significantly smaller (14%). Compared to results from previous studies and estimations by security agencies, there is an over-representation of converts in the sample. Although converts are only slightly over-represented in the French and the U.K. samples, the over-representation of converts in the German sample is somewhat more marked.Footnote61

The difference between the U.K. sample and the other two samples in terms of their share of converts among foreign fighters is more pronounced once the migration background of the converts is taken into account. Converts without a migration background constitute only 4% of the British foreign fighters, whereas this number is around 15% for both France and Germany. These findings correspond to results of previous studies.Footnote62

Overall, the average age at the time of departure was 25, with a standard deviation of 7. At 11 years old, the youngest foreign fighters in the sample were Joe George Dixon from the U.K. and Rayan from France.Footnote63 Women in the sample were also on average 25 years old with a standard deviation of 7. Women were strongly over-represented in the youngest age bracket, ranging from 10 to 18 years old, (24% women vs. 5% men) and slightly over-represented in the oldest age bracket, ranging from 36 to 75 years old, (17% women vs. 13% men).Footnote64 This over-representation can be explained by marriage patterns. Many young women in the sample traveled to conflict regions to find a partner or were married to foreign fighters already. In general, older women were wives or widows of foreign fighters and were involved in recruitment activities, which involved grooming potential wives for other fighters. The vast majority of male foreign fighters (83%) were either in their twenties or early thirties.

40% of the sample is originally from or has at least one parent from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. I categorize the following countries as belonging to the MENA region: Egypt, Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, Bahrain, Iraq, Iran, Yemen, Jordan, Qatar, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and the United Arab Emirates. Almost 20% of foreign fighters had South-East Asian origins (AFPAK). The AFPAK region includes Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. The third most common region of origin, excluding the population without a migration background, was Sub-Saharan Africa (11%), followed by Turkey (9%). There was no information available on the country of origin in 88 cases.

There were notable differences between France, Germany, and the U.K. Two-thirds of the foreign fighters from France had MENA origins. Only 2% had a Turkish migration background, whereas none of the foreign fighters from France had origins in the AFPAK region. There was a small minority of foreign fighters who were born in or originated from the French overseas territories, such as Réunion. Both the German and the U.K. sample were more heterogeneous in terms of the countries/regions of origins represented. Like France, the majority of the foreign fighters from Germany had MENA origins (35%). However, the second largest group were individuals with a Turkish migration background (25%). In contrast, the largest group in the U.K. sample had South Asian origins. MENA and Sub-Saharan African origin countries were equally represented, as one fifth of the sample had origins in these regions.

Results

Unemployment

The first hypothesis states that foreign fighters are disproportionately economically marginalized compared to the population at risk. I use a single measure of economic marginalization, namely the employment status prior to departure to a conflict country. The available sources revealed information on the employment status in 560 cases (55%). Almost half of the sample were employed (45%), around 23% were unemployed, and one third was still in education. If a person was unemployed, I additionally gathered information on the causes of their unemployment. I found that one fifth of those who were unemployed quit their jobs voluntarily to devote themselves to radical activism (23%), whereas 25% of the unemployed individuals were involuntarily out of work. There was no information available on whether the remaining half of the unemployed individuals (53%) were involuntarily unemployed or not. Discounting the individuals who were voluntarily unemployed due to their radicalization activities, the adjusted share of unemployed individuals lies at 18%.

To test my hypothesis, I focus on the employment status of foreign fighters across the three countries. I remove the small number of converts from the analysis, which enables me to make more meaningful comparisons with the population at the highest risk of radicalization. The results concerning the employment status of individuals who grew up in Muslim families (i.e. those who have not converted) are presented in . I will refer to the adjusted employment status, which excludes individuals who chose to be unemployed because of their radicalization, as a point of reference for the comparisons with the population at risk.

Table 2. Employment status (excluding converts).

The results show that more than two-thirds of the French sample were employed (69%). In the French sample, the adjusted share of unemployed individuals was 18%. Unemployment statistics for the Muslim population in France are not available. According to OECD data, the unemployment rate of the foreign-born population in France ranged from 14% to 18% between the years 2010 and 2016.Footnote65 The annual statistics report published by the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies has shown that the share of immigrants looking for a job in France increased from 15.2% in 2009 to 18.4% in 2015.Footnote66 The unemployment rate of men with non-EU citizenship was even higher than the overall migrant population and was reported to be around 22.7% in 2014.Footnote67 Given these statistics, the adjusted unemployment rate of 18% is not disproportionately high.

At 33%, the adjusted share of unemployed individuals is highest among the German sample. Data on the unemployment rate among the Muslim population in Germany is not available. However, available statistics suggest that young men with a migration background are particularly affected by high rates of unemployment in Germany. For instance, the unemployment rate among men with a migration background between the ages 15 and 25 was 18%.Footnote68 Moreover, adult populations with a Turkish (16%), Iraqi (28%), Syrian (25%), or Afghan (18%) migration background have a much higher rate of unemployment than Germans without a migration background (6%).Footnote69 The unemployment rate for non-German citizens is on average even higher than the unemployment rate for people with a migration background: between the years 2010 and 2014, the unemployment rate among Turkish citizens in Germany varied between 18% to 23%, while it was on average between 31% and 38% for citizens of Afghanistan, Eritrea, Iraq, Iran, Nigeria, Pakistan, Somalia, and Syria.Footnote70 Based on these statistics, an unemployment rate of 33% is only slightly above the unemployment rates for the demographic group corresponding to the sample.

The majority of foreign fighters from the U.K. were in education prior to their departure. Compared to the other two countries, U.K. had the lowest adjusted share of unemployed individuals (12%). A report published by the Women and Equalities Committee of the House of Commons documented that the unemployment rate among the Muslim population in the U.K. ranged between 17.2% in year 2011 to 12.8% in year 2015, whereas the overall unemployment rate ranged between 8.1% to 5.4% in the same time period.Footnote71 Compared to the general Muslim population, the foreign fighter sample from the U.K. is not disproportionately unemployed. Even if the unemployment rate for the general population is taken as a point of comparison, the difference is not so substantial.

Overall, these findings suggest that the European foreign fighters were not disproportionately unemployed compared to the general Muslim population in their respective countries. Only foreign fighters from Germany were slightly more affected by high unemployment rates, whereas the unemployment rate among the foreign fighters in British sample was even slightly below than that of the general British Muslim population. These findings are further confirmed by the results of the logistic regression analysis of the survey data. The findings presented in indicate that unemployed respondents are not significantly more likely to express support for foreign fighters than employed respondents.Footnote72 These results lead me to reject Hypothesis 1.

Table 3. Results of the logistic regression analysis.

Table 4. Professional qualification status (excluding converts).

Table 6. Federal state of residence of Foreign Fighters from Germany prior to mobilization and estimated Muslim population.

Table 7. Region of residence of Foreign Fighters from the U.K. prior to mobilization and estimated Muslim population.

Educational Attainment

The second hypothesis states that individuals with low educational qualifications are over-represented among the foreign fighter population compared to the population at risk. There was information on educational qualification for 521 cases (51%). I distinguished between having any form of professional qualification, such as a university degree, college diploma, vocational training, or apprenticeship, and having no professional qualification at all. If a person had no qualifications, I additionally gathered information on why this was the case. Those who quit their training to devote their time to dawah activities, who interrupted their training to travel to a conflict country, or who were arrested for terrorism-related activities before completing their training were coded as drop-out due to radicalization. Those who left university or dropped out of their training because of bad grades or other reasons not related to radicalization were not included in this category. The adjusted qualification status is the resulting number of individuals without any professional qualification minus those who dropped out due to their radicalization.Footnote73 In the following, I discuss the professional qualifications of foreign fighters from each country and compare them to trends among the general Muslim population within each country.

Compared to the first- and second-generation migrant populations, French foreign fighters did not disproportionately lack professional qualifications (see ): Around 45% of the first-generation French population had either a vocational training or a university degree, while around 52% of the descendants of migrants had such a professional qualification.Footnote74 The adjusted share of the French foreign fighter sample without a qualification (50%) corresponds to these numbers.

Without accounting for dropouts, the share of individuals in the German sample without any professional qualification is very high (78%). However, once drop-outs are considered, the share of those without any qualification falls to 52%. Compared to the proportion of the overall German population without any professional qualifications, this is a high number. However, compared to the population with a Turkish (64%) or Middle Eastern migration background (55%), those without any qualifications are, in fact, under-represented (see ).Footnote75

One notable characteristic of the British sample is that many recruits were university students, either in the U.K. or abroad, and dropped out of university following their radicalization. Accordingly, the adjusted share of British foreign fighters without any professional qualification is 53%. Using this adjusted figure, the number is actually lower than the share of those without any qualifications within the general Muslim population (61%).Footnote76

In sum, these findings indicate that compared to the Muslim population in Europe, European foreign fighters are not, on average, less qualified than the reference population. Concerning support for foreign fighters, the results of the regression analysis suggests that respondents with lower or mid-levels of education are not more likely to express support for foreign fighters than respondents with higher educational degrees. Therefore, I reject Hypothesis 2.

Additional Analyses

Previous research has identified four waves of foreign fighters and has shown how the characteristics of the Jihadis differed across the four waves.Footnote77 The foreign fighters of the first two waves were part of the al-Qaeda networks and active until the beginning of the 2000s. In terms of their demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, they were, on average, older, disproportionately from middle-class backgrounds, and much better educated than their successors. The third wave was boosted by the invasion of Iraq and was active until the 2010s, whereas the fourth wave emerged following the civil war in Syria. The literature suggests that, in contrast to the previous waves, foreign fighters of the fourth wave are mostly younger individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, who face a range of personal difficulties and lack perspectives.Footnote78

In this study, I have analyzed profiles of foreign fighters who departed to a conflict country between 2000 and 2016, which roughly corresponds to the most recent two waves of mobilization discussed in the literature. Arguably, the findings may be distorted due to the pooled sample consisting of Jihadists from two different waves. To investigate whether this is the case, I split the sample into two groups: those who were mobilized before 2011 and those who were mobilized after 2010. I then once again assessed the unemployment rates and the share of those with professional qualifications. The results of these analyses can be found in the Online Appendix Tables S5–S8.

The unemployment rates do not differ between the two waves. Both before and after 2011, the share of unemployed foreign fighters is around 18%, which is equal to the results of the pooled sample. In terms of education, however, there are marked differences between the two waves. Foreign fighters who were mobilized until 2011 are more likely to have a qualification (54%) than foreign fighters who were mobilized after 2010 (44%). The differences are most pronounced in France, where 69% of the foreign fighters from the wave before 2011 had a qualification versus 42% of the foreign fighters from the wave after 2010. Interestingly, the opposite pattern is observed among the British sample: British foreign fighters who were mobilized before 2011 are, in fact, on average, less educated (41%) than their successors (51%). One possible explanation for the differences among the pooled sample concerning the qualifications across the two waves is the age distribution (see Online Appendix Figure S4): Whereas around 60% of the foreign fighters who left after 2011 were below the age of 25, this share was only 45% among those who left before 2011. This age bracket corresponds to the period in life, in which individuals are most likely to obtain their educational qualifications. Overall, these findings provide further evidence against the explanatory role of socioeconomic integration deficits in the radicalization process of foreign fighters.

Bloc Recruitment

According to the third hypothesis, foreign fighters should be geographically diffused and recruited from regions in proportion to the Muslim populations residing there. To test this hypothesis, I compared the number of foreign fighters from each sub-national region within each country with the estimated share of the overall Muslim population in that corresponding region. I use the highest tier of sub-national division within each country: For France, the 13 administrative regions (excluding the 5 overseas regions); for Germany, the 16 federal states; and for the U.K., the 9 regions of England plus Wales. I was able to identify the region of residence prior to mobilization in 986 cases (97%).Footnote79

shows the region of residence in France prior to mobilization and the estimated Muslim population in that region. Since there were no official statistics on the number of Muslims living within each region, I estimated the number of Muslims using the number of foreign nationals originating from Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and Turkey reported in the 2016 French Census data.Footnote80 The findings clearly suggest a clustering of foreign fighters in certain regions. The vast majority of the sample was residing in a city or town in the Île-de-France region (44%). This may not be so surprising since Paris is situated within this region. However, despite hosting the majority of the Muslim population (36%), foreign fighters were still over-represented in this region (+8 percentage points). Foreign fighters were most disproportionately recruited from the Occitaine region, where there was a + 11percentage points difference. In contrast, they were under-represented in regions like Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (-1 percentage points), Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (-3 percentage points), or Grand Est (-5 percentage points) which host a considerable fraction of the French Muslim population.

Table 5. Region of residence of Foreign Fighters from France prior to mobilization and estimated Muslim population.

Official statistics on the Muslim population was also not available in Germany. Therefore, I estimated the number of Muslims in each region based on the number of foreign nationals originating from Muslim-majority countries using the 2011 German Census data (). 34% of the sample was based in North Rhine-Westphalia, which is also the federal state with the largest estimated Muslim population (31%). Nevertheless, foreign fighters were slightly over-represented there (+3 percentage points). All three city-states, namely Hamburg (+8 percentage points), Berlin (+3 percentage points), and Bremen (+3 percentage points), were major hubs of mobilization. On the other hand, foreign fighters from Baden-Württemberg and Bavaria were markedly under-represented (-10 and −9 percentage points, respectively). Together, these two federal states are home to the same number of Muslims as North Rhine-Westphalia. Yet, recruits from these states make up only less than half of those originating from North Rhine-Westphalia.

In the U.K., the London region was the major hub of foreign fighter recruitment. Despite London hosting only over a third of the Muslim population, half of the British foreign fighters (+13 percentage points) originated from this city (). Foreign fighters were particularly under-represented in the regions North West (-5 percentage points) and Yorkshire and the Humber (-6 percentage points).

Overall, foreign fighters were markedly under-represented in certain regions and significantly over-represented in others across all three countries. The metropolitan regions, in which the largest share of the respective Muslim populations resided in, were also the regions with the highest share of foreign fighters (Île-de-France in France, North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany, and London in the U.K.). Nevertheless, foreign fighters were over-represented in all these regions. The largest clustering was observed in London in the U.K., where foreign fighters were over-represented by +13 percentage points, followed by the Occitaine region in France (+12 percentage points). In contrast, in every country there were also regions with large Muslim populations, in which foreign fighters were significantly under-represented. Germany constitutes a particularly notable case, as disproportionately few foreign fighters were mobilized in Baden-Württemberg (-10 percentage points) and in Bavaria (-9 percentage points). These findings strongly contradict Hypothesis 3.

Conclusions

The results presented in this study challenge previous popular and academic accounts which highlight educational deficiencies and economic hardships as major drivers of Islamist radicalization in Europe.Footnote81 There are three reasons behind these contrasting results. The first reason concerns the sample. Previous studies mostly relied on small sample sizes and primarily focused on individual countries. In contrast, I drew on a much larger sample including more than 1000 observations from three different countries. The sample used in this study is unique, as it consists of the largest available number of observations on European foreign fighters to date. By including foreign fighters from France, Germany, and the U.K., I have shown how the average level of educational attainment of foreign fighters can differ between countries. Moreover, results from the U.K. show that above-average educational qualifications do not represent a sufficient remedy against radicalization. The second reason concerns my operationalization of the socioeconomic variables. Instead of focusing only on foreign fighters’ employment status or their highest level of educational attainment, as implemented in previous research, I examined the biographies of individuals. This allowed me to identify whether they had dropped out of education or quit their jobs precisely because of their radicalization. The relevance of taking such cases into account becomes clear once they are omitted from the measure. In fact, the adjusted results differ strongly from those prior to adjustment regarding both, the share of foreign fighters who were unemployed and of those without any professional qualifications.

Finally, my analytical strategy also breaks with that employed by previous research. In general, prior studies only reported the characteristics of foreign fighters in their sample and highlight the discrepancies between their sample and the general population. They then concluded that these integration deficits facilitated radicalization. In contrast, I compared my sample of foreign fighters to that of the population with the highest risk of radicalization, namely the young male Muslim population. When such data was not available, I drew on comparisons with the general Muslim population or with the population with a migration background. As I have shown, once the adjusted statistics are compared to the population most at risk of radicalization, the discrepancies tend to diminish. The average characteristics of foreign fighters in terms of employment status and educational attainment correspond to the average characteristics of the respective Muslim population. To further underline the generalizability of the findings, I complement the biographical data analysis with regression analyses of original survey data on the Muslim population in Germany. The results indicated that unemployed or less educated respondents were not more likely to support foreign fighters than employed or more educated respondents. Moreover, the data on contexts of mobilization confirmed predictions from social movement theory regarding bloc recruitment: When compared with the share of the Muslim population living in certain cities or regions, foreign fighters were over-represented in some, but notably under-represented in other regions. Given this geographical concentration, the data suggests that socioeconomic factors are rather peripheral to foreign fighter recruitment in Europe. As a result, the findings presented here contest the prominent integration deficit theory.

Based on these results, counterterrorism and deradicalization efforts are more likely to be successful when they are directed toward other drivers of recruitment and mobilization. A rich body of literature points to the crucial role of interpersonal and organizational networks in radicalization processes of terrorism offenders.Footnote82 In line with this scholarship, a recent comparative analysis has identified mobilizing structures, such as Salafist mosques, as important contexts of radicalization of European foreign fighters.Footnote83 As Nesser argues, the most important steps that need to be taken to deal with Islamist extremism in Europe should involve intercepting charismatic and resourceful entrepreneurs, who enlist, socialize, and train recruits, as well as restraining both national and trans-national network connections between extremists.

The main limitation of this study concerns the significant share of missing observations. Overall, information on employment status and professional qualifications was missing for around half of the cases. Similarly, for around half of the cases, no information was available on the reason for unemployment or for lack of professional qualifications. Arguably, these missing observations may have biased the findings. However, given the large sample size and the similar findings across three different countries, I assume that this bias was minimal. To obtain more definite conclusions regarding the role of socioeconomic variables, future research should draw on court and police records, which provide more complete and in-depth information on these variables. Unfortunately, such records are generally classified and not easily accessible. Publicly available data could also be complemented with survey data gathered from returnees from conflict countries. Another limitation is the lack of available data on the share of unemployment and the levels of educational attainment of young Muslim men in European countries. Ideally, data on the socioeconomic characteristics of the relevant control group, namely the population most at risk for radicalization, would have enabled more precise and accurate comparisons. Another fruitful avenue worth exploring further is the triangulation of findings from biographical research with representative survey studies. While this study only relied on such data in the case of one Western European country, Germany, cross-sectional comparative survey studies across European countries could considerably improve our understanding of radicalization processes.

Ethics

This study received an ethics approval from the WZB Research Ethics Committee (WZB Ethics Research Review No. 2019/1/52).

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (779.4 KB)Acknowledgements

Comments by Ruud Koopmans, Peter Wetzels, Naika Foroutan, Bart Schuurman, my colleagues at the Migration and Diversity department at the WZB, and by the anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged. The author also thanks Alice Bobée, Jan Osenberg, Ruben Below, Stefanie Nebel, and Thomas Tichelbäcker for superb research assistance.

Disclosure Statement

There are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Syed Mansoob Murshed and Sara Pavan, “Identity and Islamic Radicalization in Western Europe,” Civil Wars 13, no. 3 (2011): 259–79; Tinka Veldhuis and Jørgen Staun, Islamist Radicalisation: A Root Cause Model (The Hague: Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael, 2009); Robert S. Leiken, Europe’s Angry Muslims (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

2 Abbas Tahir, “Islamic Political Radicalism in Britain - Synthesizing the Politics of Identity in Context Introduction,” in Radikaler Islam im Jugendalter Erscheinungsformen, Ursachen und Kontexte, ed. Maruda Herding, 110–24. (Halle (Saale): Deutsches Jugendinstitut e. V., 2013): 119.

3 Lorne L. Dawson and Amarnath Amarasingam, “Talking to Foreign Fighters: Insights into the Motivations for Hijrah to Syria and Iraq,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 40, no. 3 (2017): 192.

4 Kennedy Odede, “Terrorism’s Fertile Ground,” The New York Times (2014). http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/09/opinion/terrorisms-fertile-ground.html%5Cnhttp://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/09/opinion/terrorisms-fertile-ground.html?nl=todaysheadlines&emc=edit_th_20140109 (accessed March 8, 2017); for earlier examples see also Claude Berrebi, “Evidence about the Link Between Education, Poverty and Terrorism among Palestinians,” Peace Economics, Peace Science, & Public Policy 13, no. 1 (2007): 1–36.

5 David Sterman, “Don’t Dismiss Poverty’s Role in Terrorism Yet,” Time (2015). https://time.com/3694305/poverty-terrorism/ (accessed June 1, 2018).

6 Secretary of State for the Home Department, Prevent Strategy (London: The Stationary Office, 2011); Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, “Integration Als Extremismus-Und Terrorismusprävention. Zur Typologie Islamistischer Radikalisierung Und Rekrutierung,” 2007. https://www.verfassungsschutz.de/de/oeffentlichkeitsarbeit/publikationen/pb-islamismus/broschuere-2007-01-integration (accessed June 1, 2018).

7 e.g., Claire L. Adida, David D. Laitin, and Marie-Anne Valfort, Why Muslim Integration Fails in Christian-Heritage Societies (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016); Anthony F. Heath, Catherine Rothon, and Elina Kilpi, “The Second Generation in Western Europe: Education, Unemployment, and Occupational Attainment,” Annual Review of Sociology 34, no. 1 (2008): 211–35.

8 For a review see Lorne L. Dawson, “A Comparative Analysis of the Data on Western Foreign Fighters in Syria and Ira: Who Went and Why?” ICCT Research Paper (2021).

9 e.g., Marc Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004); Alan B. Krueger and Jitka Malečková, “Education, Poverty and Terrorism: Is There a Causal Connection?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 17, no. 4 (2003): 119–44.

10 e.g., Sean C. Reynolds and Mohammed M. Hafez, “Social Network Analysis of German Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq,” Terrorism and Political Violence 31, no. 4 (2019): 661–86; Bakker, Edwin, and Roel de Bont, “Belgian and Dutch Jihadist Foreign Fighters (2012–2015): Characteristics, Motivations, and Roles in the War in Syria and Iraq,” Small Wars and Insurgencies 27, no. 5 (2016): 837–57.

11 e.g., Gavin Lyall, “Who Are the British Jihadists? Identifying Salient Biographical Factors in the Radicalisation Process,” Perspectives on Terrorism 11, no. 3 (2017): 62–70; Olivier Roy, Jihad and Death: The Global Appeal of Islamic State (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017); Bakker and de Bont, “Belgian and Dutch;” Rik Coolsaet, Facing the Fourth Foreign Fighters Wave. What Drives Europeans to Syria, and to Islamic State? Insights from the Belgian Case (Brussels: Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations, 2016).

12 Quintan Wiktorowicz, Radical Islam Rising. Muslim Extremism in the West (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2005): 51–53.

13 These limitations are understandable, given the financial costs, language barriers, and the time required to collect biographical information on foreign fighters from publicly available resources.

14 Bibi van Ginkel and Eva Entenmann (editors), “The Foreign Fighters Phenomenon in the European Union. Profiles, Threats and Policies,” The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague 7, no. 2 (2016): 50.

15 The Soufan Group, Foreign Fighters: An updated assessment of the flow of foreign fighters into Syria and Iraq (New York: The Soufan Group, 2015).

16 Another reason for why I focused on these three countries concerns language proficiency. Collecting and interpreting qualitative data requires a high level of language proficiency. The principal investigators of the data collection effort were fluent in German and in English, which is why these countries were ideal cases. Student assistants who were fluent in French were hired to code the French profiles.

17 Bert Klandermans and Dirk Oegema, “Potentials, Networks, Motivations, and Barriers: Steps towards Participation in Social Movements,” American Sociological Review (1987): 519–531.

18 Brandeis University, Jytte Klausen’s Western Jihadism Project. About the Project. 2019a. https://www.brandeis.edu/klausen-jihadism/project.html (accessed January, 1 2019).

19 Alberto Abadie, “Poverty, Political Freedom, and the Roots of Terrorism,” American Economic Review 96, no. 2 (2006): 50–56; Krueger and Malečková, “Education, Poverty.”

20 Adida, Laitin, and Valfort, “Why Muslim Integration;” Heath, Rothon, and Kilpi, “The Second Generation.”

21 Berrebi, “Evidence about,” 5–6.

22 Gary S. Becker, “Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach,” Economic Analysis of the Law: Selected Readings 76, no. 2 (2007): 255–65.

23 Berrebi, “Evidence about,” 19.

24 Najeeb M. Shafiq and Abdulkader H. Sinno, “Education, Income, and Support for Suicide Bombings: Evidence from Six Muslim Countries,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 54, no. 1 (2010): 152.

25 Robert Agnew, “A General Strain Theory of Terrorism.” Theoretical Criminology 14, no. 2 (2010): 131–53.

26 Marc Sageman, “Understanding Terror.”

27 Berrebi, “Evidence about;” Krueger and Malečková, “Education, Poverty.”

28 Dawson, “A Comparative Analysis,” 13–14.

29 Peter R. Neumann, Radicalized: New Jihadists and the Threat to the West (London: I.B. Tauris, 2016): 89.

30 Bakker and de Bont, “Belgian and Dutch,” 845.

31 Coolsaet, “Facing the Fourth.”

32 Reynolds and Hafez, “Social Network.”

33 e.g., Reynolds and Hafez, “Social Network;” Lyall, “Who are the British;” Coolsaet, “Facing the Fourth.”

34 Reynolds and Hafez, “Social Network,” 664.

35 Wiktorowicz, “Radical Islam,” 51–53.

36 Alexander Lee, “Who Becomes a Terrorist? Poverty, Education, and the Origins of Political Violence,” World Politics 63, no. 2 (2014): 214.

37 UNESCO, “Preventing Violent Extremism through Education. A Guide for Policy-Makers,” (2017). http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002477/247764e.pdf (accessed May 5, 2019); European Parliament, “Prevention of Radicalisation and Recruitment of European Citizens by Terrorist Organisations,” (2015). http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//NONSGML+TA+P8-TA-2015-0410+0+DOC+PDF+V0//EN (accessed May 5, 2019).

38 Shafiq and Abdulkader, “Education, Income;” Orlandrew E. Danzell, Yao-Yuan Yuan Yeh, and Melia Pfannenstiel, “Does Education Mitigate Terrorism? Examining the Effects of Educated Youth Cohorts on Domestic Terror in Africa,” Terrorism and Political Violence 30, no. 8 (2020): 1731–52.

39 Krueger and Malečková, “Education, Poverty.”

40 Berrebi, “Evidence about.”

41 Marc Sageman, Leaderless Jihad: Terror Networks in the Twenty-First Century (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008).

42 Diego Gambetta and Steffen Hertog, Engineers of Jihad (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017).

43 Coolsaet, “Facing the Fourth.”

44 Edwin Bakker, Jihadi Terrorists in Europe: Their Characteristics and the Circumstances in Which They Joined the Jihad- an Exploratory Study (The Hague: Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael, 2006).

45 Lasse Lindekilde, Preben Bertelsen, and Michael Stohl, “Who Goes, Why, and With What Effects: The Problem of Foreign Fighters from Europe,” Small Wars and Insurgencies 27, no. 5 (2016): 858–77.

46 Reynolds and Hafez, “Social Network.”

47 For the UK see Lyall, “Who are the British”; for Belgium and the Netherlands see Bakker and de Bont, R, “Belgian and Dutch.”

48 See Reynolds and Hafez, “Social Network;” for a similar approach.

49 Anthony Oberschall, Social Conflict and Social Movements (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1974): 125.

50 Doug McAdam, “Recruitment to High-Risk Activism: The Case of Freedom Summer,” American Journal of Sociology 92, no. 1 (1986): 64–90; Donatella della Porta, Clandestine Political Violence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

51 Sageman, “Leaderless Jihad.”

52 Petter Nesser, Islamist Terrorism in Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

53 Timothy Holman, “Belgian and French Foreign Fighters in Iraq 2003–2005: A Comparative Case Study,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 38, no. 8 (2015): 603–21.

54 Eylem Kanol, “Contexts of Radicalization of Jihadi Foreign Fighters from Europe 2022,” Perspectives on Terrorism, 16, no. 3, 45–62.

55 Reynolds and Hafez, “Social Network;”

56 See Online Appendix 2 Figure 1.

57 See Eylem Kanol, Ruud Koopmans, and Dietlind Stolle, “Religious Fundamentalism and Radicalization Survey. Version 1.0. 0. WZB Berlin Social Science Center. Data set.” (2020).

58 See Online Appendix 2 Table 1.

59 BBC, “Who are Britain’s Jihadists.” (2017). https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-32026985 (accessed March 8, 2017); Reynolds and Hafez, “Social Network;” Lyall, “Who are the British;” van Ginkel, and Entenmann, “The Foreign Fighters;” BfV, BKA, and HKE, “Analyse der den deutschen Sicherheitsbehörden vorliegenden Informationen über die Radikalisierungshintergründe und- Verläufe der Personen, die aus islamistischer Motivation aus Deutschland in Richtung Syrien ausgereist sind,” (2014). http://www.innenministerkonferenz.de/IMK/DE/termine/to-beschluesse/14-12-11_12/anlage-analyse.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (accessed June 18, 2017).

60 van Ginkel, and Entenmann, “The Foreign Fighters,” 31.

61 van Ginkel, and Entenmann, “The Foreign Fighters,” 31; Lyall, “Who are the British;” BfV, BKA, and HKE. “Analyse der.”

62 for Germany, see Reynolds and Hafez, “Social Network;” for the UK, see Lyall, “Who are the British;” unfortunately there are no comparable numbers available for France.

63 Despite their very young age, I have opted to include them in the sample since they have both been featured in Isis propaganda videos, where they were filmed executing prisoners. Matthew Weaver, “Sally Jones: UK punk singer who became leading Isis recruiter.” (The Guardian, 2017). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/12/sally-jones-the-uk-punk-singer-who-became-isiss-white-widow (accessed April 1, 2019); Noemie Bisserbe and Stacy Meichtry, “French Children Add to ISIS Ranks.” (Wall Street Journal, 2015). https://www.wsj.com/articles/french-children-add-to-isis-ranks-1451085058 (accessed April 1, 2019).

64 See Online Appendix 2 Table 3.

65 OECD, “Foreign-Born Unemployment,” 2019. https://data.oecd.org/migration/foreign-born-unemployment.htm (accessed April 2, 2019).

66 Catherine Demaison, Laurence Grivet, Denise Maury-Duprey, and Séverine Mayo-Simbsler, France, Portrait Social. Édition 2018. Montrouge: Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (Insee), (2018): 169.

67 Insee, “Tableaux de l’Économie Française. Édition 2014,” 2014. https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/1288329?sommaire=1288404#consulter-sommaire (accessed April 15, 2019).

68 Katharina Seebaß and Manuel Siegert. Migranten am Arbeitsmarkt in Deutschland. Working Paper 36 der Forschungsgruppe des Bundesamtes. (Nürnberg: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, 2011): 59.

69 Statistisches Bundesamt, Migration und Integration. Integrationsindikatoren. 2005-2017. (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2019): 92.

70 The German Federal Employment Agency reports the unemployment rate among citizens of these countries grouped together under the category of “non-European countries of origin of asylum seekers.” Bundesagentur für Arbeit, “T-Quoten-Migrations-Monitor-Arbeitsmarkt-Bundesebene-Mit-Quoten,” 2019. https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/Navigation/Statistik/Statistik-nach-Themen/Migration/Personen-nach-Staatsangehoerigkeiten/Personen-nach-Staatsangehoerigkeiten-Nav.html (accessed June 25, 2019)

71 House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee, “Employment opportunities for Muslims in the UK,” House of Commons, 2016. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmwomeq/89/89.pdf, 34.

72 I conducted two robustness checks which can be found in the Online Appendix. First, I estimated an ordered logistic regression model and arrive at the same results. Second, I included an additional indicator of economic marginalization, namely household income, in the regression analysis. Arguably, some individuals can be employed but still be economically marginalized, due to precarious employment conditions or low income. These results are in-line with the main analysis and suggest that respondents from low-income households are not significantly more likely to support foreign fighters than respondents from middle- or high-income households.

73 The adjusted qualification status is a rough estimation and should be interpreted cautiously. On the one hand, it over-estimates the number of individuals with a qualification, because not all of the individuals who dropped out due to radicalization would have completed their training. On the other hand, it under-estimates the number of individuals with a qualification, because there was no information available on why many individuals dropped out of their training. It is very likely that some of these individuals also dropped out due to radicalization. Moreover, individuals who dropped out of primary or secondary school were also excluded from this analysis, since I could not predict, whether they would have pursued a vocational training or university degree after school.

74 Own calculations based on data from Hajji, Ilhame, “Diplôme Selon Le Lien À La Migration Et Les Origines Sociales,” Infos Migrations 94, no. 9 (2019): 1–4.

75 Heinz-Herbert Noll and Stefan Weick. “Zuwanderer mit türkischem Migrationshintergrund schlechter integriert: Indikatoren und Analysen zur Integration von Migranten in Deutschland,” Informationsdienst Soziale Indikatoren 46, no. 46 (2011): 1–6.

76 Own calculations based on data from Nomis, “LC5204EW - Highest Level of Qualification by Religion.” 2011. https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/census/2011/lc5204ew (accessed October 10, 2019).

77 Sageman, “Understanding Terror.”

78 Coolsaet, “Facing the Fourth.”

79 A few number of foreign fighters grew up in and were citizens of France, Germany, or the UK but departed to a conflict country from another country. These few cases were removed from this analysis.

80 Insee, “Population Immigrée Selon Les Principaux Pays de Naissance En 2016. Comparaisons Régionales et Départementales,” 2019. https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/2012727 (accessed October 30, 2019). These are the only non-EU countries of origin reported in the 2016 French Census data. Insee reports the population from these countries in each French “department”, which I aggregated to the region level.

81 e.g., Coolsaet, “Facing the fourth;” Sterman, “Don’t dismiss;” Odede, “Terrorism’s Fertile;” Abbas, “Islamic Political;” Bakker and de Bont, “Belgian and Dutch.”

82 See e.g., Sageman, “Understanding Terror;” Nesser, “Islamist Terrorism.”

83 Kanol, “Contexts of Radicalization.”

84 Anja Stichs, Wie viele Muslime leben in Deutschland? Eine Hochrechnung über die Anzahl der Muslime in Deutschland zum Stand 31. Dezember 2015. Working Paper 71 des Forschungszentrums des Bundesamtes (Nürnberg: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, 2016).

85 Office for National Statistics, “CT0265 - Country of Birth by Year of Arrival by Religion,” 2011.

86 Insee, “Population Immigrée.”