Abstract

How conspiracy theories mobilize protesters against the Covid-19 measures and whether they harbor an underestimated potential for radicalization requires more research. This paper first recognizes the possibility of anti-government conspiracy theories to mobilize a heterogeneous “resistance movement” and theorizes their ability to radicalize some supporters. An analysis of 71 interviews from the German magazine “Demokratischer Widerstand” reveals that an entire “Covid-regime” is often marked as an enemy. The empirical investigation suggests that conspiracy beliefs reflect a means of processing adverse experiences and anxieties, yet are increasingly directed against the political order, fostering anti-democratic attitudes and actions.

The Heterogeneous German Covid-19 Protests

The outbreak of the Covid-19 virus in early 2020 disrupted many daily lives. Governments’ responding public health measures sought to minimize the spread of the virus, relieve the burden on healthcare systems, and care for populations. Next to advisory guidelines, such as hand washing and physical distancing, orders like mandatory masks, testing, and contact restrictions, governments worldwide ultimately also restricted public life through so-called lockdowns, including shop closures, travel restrictions, and sometimes curfews. While most citizens accepted temporary restrictions and curtailments of common fundamental rights as necessary to prevent Covid-19 from spreading, they were also met with protest, especially in Europe and beyond.Footnote1

Germany stands out as an interesting example, as protests started in spring 2020 but continue irregularly,Footnote2 while the will to exercise the democratic right to protest against the Covid-measures among the German population is high by international comparison (11–15%).Footnote3 However, a particularly distinctive feature of the German protests is their heterogeneity, manifested through cross-milieu solidarity between the far-right and far-left, esotericists, anti-vaccinationists, and other “enraged citizens.”

While reminiscent of past anti-Islam (Pegida) protests or the Monday demonstrations against the war in Ukraine,Footnote4 the pervasiveness of conspiracy theories in a protest scene identifying as a “resistance movement” against the government’s Covid-19 measures is unprecedented.Footnote5 At the same time, the protest movement also produces and hosts groups that ideate and sometimes plan concrete coup plots against the government guided by conspiracy theories, as a recent Germany-wide raid demonstrated. Hence, this paper explores the following questions: First, How do conspiracy theories mobilize individuals into “resistance” against the Covid-19 measures? and second, provided that they do feature strongly among protesters, What role might they play in catalyzing radicalization?

Conspiracy Theories as Mobilizers and Catalysts of Radicalization?

For a long time, it seemed unclear, especially to the authorities, how an ideologically and organizationally heterogeneous supposed “resistance movement,” which networks and communicates onlineFootnote6 and mobilizes up to tens of thousands on the streets,Footnote7 should be politically situated and to what extent it can also harbor and promote currents that endanger democracy. The latter can arguably only be answered if one refrains from describing the heterogeneous protests as a “melting pot”Footnote8 or avoids merely pointing to the rejection of state authority as a common denominatorFootnote9 but instead looks at protestors’ ties.

Conspiracy theories are one unifying factor that offers valuable insights for legitimate protest mobilizationFootnote10 but also for the possible radicalization of some individuals who exploit their democratic right to protest for anti-democratic aspirations. Whether they contribute to some protesters seeing violence as legitimate for political change or even violent acts based on such worldviewFootnote11 is furthermore a question arising particularly in light of growing concerns about anti-government extremism. This is a form of extremism characterized by a pronounced and consequential hostility to the government and all associated institutions and politicians,Footnote12 which can also manifest itself in concrete plans to overthrow it, as demonstrated by the recently uncovered plans of a grouping some of whose members had featured prominently in protests against Covid-measures.Footnote13

That conspiracy theories in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic are increasingly ascribed a radicalizing function is, among others, reflected in Ackerman and Peterson’s prediction that “dissatisfaction with government responses to Covid-19, reinforced by conspiracy theories, (…) is likely to exacerbate existing levels of frustration and fuel anti-government extremism in particular.”Footnote14 As detailed later, the radicalization-catalyzing role of conspiracy theories is generally increasingly discussed in the literature.Footnote15

Research Gap

To the author’s knowledge, little theoretical, let alone empirical, research has been conducted on first, how specific conspiracy theories can initially mobilize protesters to join a “resistance movement” during the Covid-19 pandemic and second, how they can drive a possible cognitive and behavioral radicalization of some protesters and turn an exercise of a democratic right into an undemocratic aspiration. This paper contributes to filling these gaps by first theoretically discussing the nexus between primarily anti-government Covid-19 conspiracy theories and radicalization and then qualitatively examining protesters’ statements about “resistance” in an empirical analysis of this nexus.

Investigating how Covid-19 conspiracy theories affect protest behavior and cognitive or behavioral radicalization not only follows the call for more research on “conspiracy-based radicalization”Footnote16 but also has practical and scientific added value. On the one hand, it is highly relevant for preventing and countering extremism to determine what promotes extremist worldviews and acts.Footnote17 On the other hand, addressing anti-government extremism from a primarily socio-psychological perspective promises to contribute to the debate on radicalization processes.Footnote18

Starting with a theoretical discussion that first clarifies what conspiracy theories are and why they are so prevalent during crises, the paper will identify anti-government conspiracy theories as unifying in the German protest scene against the Covid-19 measures, explain their qualities, and argue that they not only mobilize legitimate protest but can, though not necessarily, catalyze anti-government radicalization. Subsequently, the research questions How do conspiracy theories mobilize individuals into “resistance” against the Covid-19 measures? and, if they have a mobilizing effect, What role might they play in catalyzing radicalization? will be empirically investigated through a qualitative content analysis of 71 interviews from the protest magazine “Demokratischer Widerstand” [Democratic Resistance].

It will become apparent that interviewees primarily use conspiracy theories directed against a “Covid-regime” to process negative experiences of social hostility or confrontation with state authorities. These interpretive processes reflect an increasing hostility toward the political order combined with a growing sense of existential threat and thus lay the groundwork for considering violence against the “Covid-regime” as legitimate or system change as a necessity. Finally, after discussing the findings with reference to the theoretical discussion of the qualities and predicted effects of anti-government conspiracy theories on the Covid-19 protest, the paper will conclude with final remarks on its relevance and possible future research avenues.

Causes, Structures, and Effects of Covid-19 Conspiracy Theories

Whether the term conspiracy theory is appropriate since adherents’ beliefs are neither based on scientific facts nor dismissed in the face of counterevidence is questionable,Footnote19 but this notion, which ultimately aptly reflects a search for meaning,Footnote20 has persisted. Beyond terminological debates, a conspiracy theory can be defined as an “attempt to explain the ultimate causes of significant social and political events and circumstances with claims of secret plots”Footnote21 by actors with malevolent intentions.Footnote22 The belief that the vaccine is a tool to decimate the world population or that governmental measures serve to establish a dictatorship are examples of conspiracy theories in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Based on the observation that people believe in multipleFootnote23 and sometimes contradictory conspiracy theories,Footnote24 social psychologists presume the existence of a “conspiracy mentality,” a predisposition to “attribute significant events to the intentional actions of mean-intending groups or individuals.”Footnote25 However, they refrain from pathologizationFootnote26 by attributing a susceptibility to a conspiracy mentality to the individual’s socio-political context.Footnote27 If the latter triggers “larger anxieties and concerns,”Footnote28 conspiracy theories flourish. As Lamberty and Nocun explain,Footnote29 the Covid-19 pandemic triggers three psychological needs that Douglas et al. have proposed as subconscious motives for conspiracy belief.Footnote30

First, uncertainty about the course of the crisis, its implications on daily routines, and the government’s actionsFootnote31 arouse epistemic needs for understanding. Second, crisis-related grievances, such as concerns about financial existence, may result in feelings of losing control.Footnote32 Lastly, the prospect of feeling unique can also augment conspiracy theories’ psychological attractiveness.Footnote33 Such epistemic, existential, and social needs may explain why, for example, 47.8% of respondents in a German representative survey strongly agreed with the statement that the true background of the pandemic would never come to light.Footnote34

After addressing conspiracy theories’ definition and their prevalence during the pandemic, the paper now looks at why anti-government conspiracy theories, in particular, mobilize “resistance” to the Covid-19 measures.

The Structure of Anti-Government Conspiracy Theories

Following Byford, conspiracy theories exhibit a typical structure or “rhetorical style,”Footnote35 inducing cognitive sense-making processes to interpret a socio-political environment.Footnote36 These involve, on the one hand, recognizing causal links and, on the other, identifying malevolent actors who can be accused of conspiracy.Footnote37 While sharing any type of opponent unites, the image of the government as a conspirator does so in a distinctive way, as it allows people with very different realities of life to solidarize behind it.

Anti-government conspiracy theories identify the government and its representatives as conspirators, in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, for example, as architects of a dictatorship that subjugates citizens and suppresses any criticism of its actions. This enemy image makes anti-government conspiracy theories compatible in many ways so that they are, as Byford noted about the new world order conspiracy theory “ecumenical” i.e. “sufficiently broad to allow conspiracy theorists from the left and from the right, from religious and secular organizations to project onto [them] their disparate ideas and concerns.”

In the heterogeneous German Covid-19 protest scene, however, the perception of the government as a conspirator and opponent, which can thus be ascribed a bridging function, is additionally charged with ostensible historical analogies. Comparisons of the pandemic measures and their social effects with the Nazi or SED dictatorship set an imperative for action by presenting an opportunity to place oneself in the tradition of resistance.Footnote38 Thus, in Germany, it is mainly the theory that the government intends to reestablish a dictatorship that contributes to the emergence of a heterogeneous supposed “resistance movement” and, as described next, influences behavior in several ways.

The Behavioral Effects of Anti-Government Conspiracy Theories

The assumption that the government harbors malicious intentions is at least accompanied by a rejection of its decisions as illegitimate, as survey data on Covid-19 conspiracy theories repeatedly demonstrates.Footnote39 That normative political behavior consequently decreasesFootnote40 is furthermore shown by several studies reporting negative correlations between conspiracy theories and containment-related behaviorFootnote41 or an association between conspiracy thinking and decreasing social distancingFootnote42 or willingness to vaccinate.Footnote43

Moreover, the rhetorical style of conspiracy theories and especially the belief in the dictatorial aspirations of the German government during the Covid-19 pandemic sets an imperative for action and implies an urgency, as the present is seen as a crucial moment to expose the conspirator and join the “resistance movement.”Footnote44 Active forms of protest, such as founding protest initiatives or participating in street protests, reflect this and, despite their legality, can be non-normative and directed against the status quo.Footnote45

Long before the Covid-19 pandemic, Imhoff and Bruder suggested that “social protest supported by conspiracy beliefs may also be particularly prone to turn ugly.”Footnote46 This raises the question of whether anti-government conspiracy theories during the Covid-19 pandemic can also fuel anti-democratic attitudes and behavior. Bartlett and Miller’s description of conspiracy theories as a “radicalization multiplier”Footnote47 within extremist groups is increasingly complemented by studies considering the former also an “important pathway into extremism.”Footnote48 Similar precursors like grievancesFootnote49 or uncertaintyFootnote50 also suggest a connection, but why anti-government conspiracy theories may provide a pathway into anti-government extremism becomes particularly clear when recognizing the similarity of the structures of both phenomena.

Anti-Government Conspiracy Theories and Radicalization

Social identity theoryFootnote51 can be used to conceptualize both the functioning of conspiracy theories and radicalization, making it suitable for illuminating a possible link between the two phenomena. One extremism scholar who follows this theoretical approach is Berger, according to whom each extremist ideology has a similar structure in that it prescribes who belongs to the in-group and out-group while framing the former’s success or survival as inseparable from fighting the latter.Footnote52 In the case of anti-government extremism, the government is declared the out-group, while the in-group is “less clearly defined.”Footnote53 This is reminiscent of Covid-19 anti-government conspiracy theories picturing a loosely defined “resistance movement” opposing an ill-intended government.

Following Berger, an individual is being radicalized by developing an increasingly hostile attitude toward the out-group, culminating in the perception that it poses a threat to the in-group.Footnote54 He points out that a conspiracy theory “relentlessly drives narratives towards extremism” as it would make adherents perceive an acute, existential crisis “that cannot be solved except through extraordinary measures.”Footnote55 How this perception impacts behavior depends on the mode of radicalization. For example, following Hafez and Mullins’ conceptualization of radicalization as two-dimensional, an individual becomes cognitively radicalized when they see the use of violence as legitimate for social or political change. Additionally, behavioral radicalization occurs when the individual furthermore acts according to this belief, which must not but may be violent.Footnote56

Applied to anti-government conspiracy theories in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, cognitive anti-government radicalization occurs when the conspiracy believer develops increasing hostility toward the government and considers a violent overthrow legitimate or even necessary. For example, they may become increasingly obsessed with the idea that the government seeks to establish a dictatorship through the Covid-19 measures until they ultimately perceive this government as an acute threat against which even violent resistance appears as a legitimate, if not necessary, form of self-defense.Footnote57

A hypothetical case, for example, might be someone who is convinced that the government wants to decimate the population with a mandatory vaccination and therefore perceives his and his fellow human beings’ existence as threatened. He becomes additionally behaviorally radicalized when acting upon this conspiracy belief and may even resort to violent means to “set a sign” like the assassin of a petrol station employee in Idar-Oberstein.Footnote58 However, since incitement to violence or hate speech can also be manifestations of anti-government extremism,Footnote59 physical violence is not a necessary consequence of anti-government behavioral radicalization.

This theory does not claim to explain radicalization to anti-government extremism fully. Behind every radicalization is a highly individual, multifaceted development,Footnote60 and the Covid-19 pandemic can also give rise to conspiracy theories that do not address government action. However, the December 7 raid on a group, some of whose members appeared publicly at Covid-19 protests, and drew on an alleged government conspiracy to plot violent overthrow, highlighted how conspiracy theories can be inherent as “enablers, multipliers and facilitators”Footnote61 to anti-government extremism.

Empirical studies have so far only investigated whether and when conspiracy beliefs in general and violent radicalization are associated. For example, based on a nationally representative survey in the U.S., Uscinski and Parent found conspiracy beliefs to be associated with increased violent intentions.Footnote62 Conversely, van Prooijen, Krouwel, and Pollet identified an association between extreme political ideologies and an increased tendency to believe in conspiracy theories.Footnote63 Moreover, according to Rottweiler and Gill’s analysis of a representative German survey, there is a causal relationship between a stronger conspiracy mentality and violent extremist intentions, especially when someone has less self-control, weaker law-relevant morality, and more self-efficiency.Footnote64 Finally, one study that could already include Covid-19 conspiracy theories is Phadke, Samory, and Mitra’s on online radicalization in conspiracy theory discussions on the Internet forum “Reddit.” The authors found that continuous or increasing participation in these discussions was associated with increasing radicalization.Footnote65

It becomes evident that empirical research on the nexus between conspiracy theories and radicalization has so far taken a quantitative approach, finding associations and intervening variables. Accordingly, how anti-government conspiracy theories can induce radicalization remains empirically underexplored. It requires a qualitative approach, presented in the following chapter, to explore the role of specific conspiracy theories with their sense-making and out-group-identifying qualities in mobilizing protest and potentially radicalization.

Methodology

This paper aims to explore the role of conspiracy theories in mobilizing and possibly radicalizing some protesters against the German Covid-19 measures empirically. To this end, the research questions, How do conspiracy theories mobilize individuals into ‘resistance’ against the Covid-19 measures? and What role might they play in catalyzing radicalization? are addressed separately. Initially, the paper identifies interviewees’ protest motives to verify that conspiracy beliefs feature in the data and have a significant mobilizing function in contrast to other motives. Once established, it will explore how conspiracy theories’ sense-making and scapegoating functions mobilize into ‘resistance’ and may show a catalyzing effect on radicalization.

Data Selection

Interviews are well suited for uncovering individual motivations and examining underlying worldviews, but engagement with the protest scene under investigation runs the risk of skeptical to hostile attitudes toward the interviewer or recruitment attempts.Footnote66 Hence, the data basis for the empirical analysis is 71 interviews with protesters published between 29.09.2020 to 19.02.2022 in the protest magazine “Demokratischer Widerstand” [Democratic Resistance], one of the leading publications from the German protest scene.Footnote67

Founded by the journalist and conspiracy theorist Anselm Lenz, the magazine has been published weekly in print and digital format since 17.04.2020 for those feeling part of or supporting a supposed “resistance movement” against the Covid-19 measures. Based on the assessment of one scholar, who described the “Demokratischer Widerstand” as a reflection of protesters’ mindsets,Footnote68 all semi-structured interviews related solely to the Covid-19 measures, which according to the magazine, represent portraits of “affected people and experts,”Footnote69 were examined. In total, the 71 interviews present the views of 85 protesters, of whom 31.1% identify as female and 61.9% as male, while the average age of the former is 47 and the latter 49. Throughout this paper, individual interviews will be cited anonymously with the labels D1 to D71 (see Appendix A for a list of interviews).

While it must be acknowledged that the magazine’s editors may have edited or selected interviews, also given the fact that security authorities monitor parts of the protest scene, the interviews are nevertheless suitable data material as they promise regular long-term insights into the concerns and worldviews within a heterogeneous “resistance movement.”

Exploring the Functions and Effects of Conspiracy Beliefs

The data analysis builds on techniques of Qualitative Content Analysis. In a first step, considering all protest motives, a software-supported descriptive category-based analysisFootnote70 is used to ascertain whether conspiracy theories are widespread among the interviews and whether these beliefs motivate protest. In addition to protest motives, the author coded any mentioned antagonists and form of protest in preparation for further analysis.

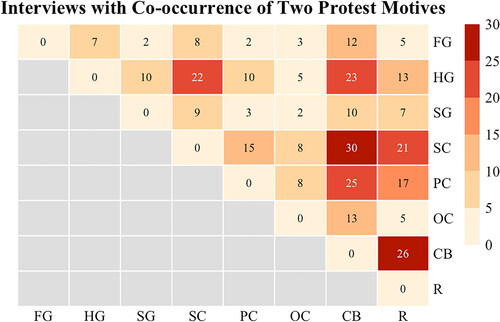

In a second step, the investigations move “beyond descriptive summation and reach explanation”Footnote71 by seeking to discover what role conspiracy theories play in shaping protest behavior. Thus, the paper explores patterns in how conspiracy theories’ sense-making and enemy-identifying qualities materialize and assesses what effect this has. A co-occurrence analysis, visualized as a heat map,Footnote72 will reveal which motives frequently co-occur with conspiracy beliefs, initiating a closer examination of these linkages. Using “genuine representative examples”Footnote73 for discussion, the paper will provide insights on how the meaning-making and out-group identifying qualities of conspiracy theories materialize and how they affect what shape “resistance” takes.

Several measures are taken to ensure the analysis’ quality despite the researcher working on their own. In addition to an audit trail, these include a time-delayed double coding of the text materialFootnote74 and an analytical approach that accounts for both the frequency of specific results as well as their weight in terms of content. Limitations of this study will be reflected after the presentation and discussion of analytical findings.

Analyzing Interviews with Individuals “in Resistance”

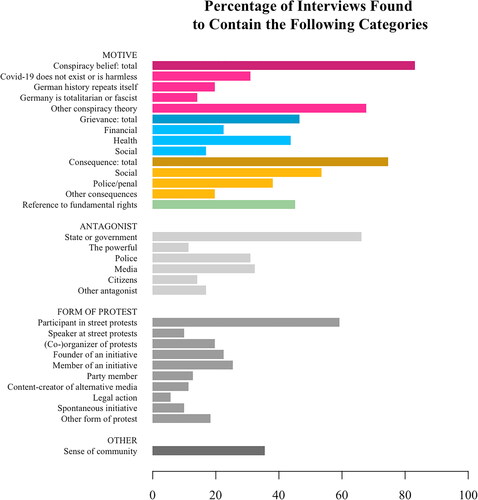

The analysis starts with describing protest motives that emerged from the 71 interviews. While some interviewees explicitly state reasons for their protest behavior, others reveal their motives through their statements. illustrates the percentage of interviews in which the protest motives that will subsequently be presented with examples were coded.

Conspiracy Beliefs

The first analytical interest was to use a category-based analysis to ascertain that conspiracy thinking underlies protest attitudes and behavior. With an occurrence in 83.1% of the interviews, conspiracy beliefs seem to motivate protest most often. While they do not identify their statements as conspiracy beliefs, interviewees accuse various actors of malicious intent in connection with the Covid-19 pandemic. These beliefs, appearing in four variants, then trigger or augment a desire for protest.

In 31% of interviews, Covid-19 is either downplayed or its existence denied. Interviewees allege deliberate misinterpretation or forgery of pandemic statistics and declare the governments’ measures disproportionate (D10; D47; D60). According to many, vaccination against a virus no worse than the influenza virus (D16; D35; D71) must be rejected as it would be useless or even dangerous (D43; D57; D69) or is an instrument of conspirators in a “pseudo-pandemic” (D15; D32; D45).

Echoing the remarks in the introduction, 19.7% of the interviews also include claims that German history is repeating. The Covid-19 measures remind some interviewees of ostracism during the Nazi regime (D31; D58; D63), and one interviewee considers vaccination a weapon of mass annihilation (D20). Protest is considered a conscientious task to ensure that Nazi crimes (Ibid.; D66) and other injustices, like denunciation during the GDR (D35; D50), are not repeated. Besides explicitly placing themselves in the tradition of a “resistance,” 14.1% of the interviewees insinuate totalitarian or fascist developments in Germany, using terms such as fascism, totalitarianism, or dictatorship interchangeably and jointly, for example, when they identify a “fascistoid structured hygiene and health dictatorship” (D60; D66) that calls for “resistance.”

In 67.6% of the interviews, other conspiracy theories emerge that reinforce the interviewees’ desire to protest. That vaccination is a genetic experiment led by billionaire Bill Gates (D36; D58; D71), that German police officers are mercenaries of the U.S. security company Constellis (D51), or that plans for a “Great Reset” (D70) are behind the pandemic are examples of theories of an international nature. In relation to Germany, it is often claimed that the government, “big players” (D44), or “dark forces” (D15) would systematically stage a pandemic (D15; D32; D52). Matching the accusations of history repeating itself or totalitarian developments, the “mainstream media” would broadcast propaganda (D18; D21; D67) while critics would be silenced (D17; D30; D39). Sometimes, however, it remains unclear intentions underly alleged conspiracies. Some speculate about power, money, and population control (D60), while others spread apocalyptic visions of targeted conspiracy (D20; D29; D45).

Other Protest Motives

Space constraints only allow a brief presentation of the other motives since they will be dealt with in more detail later in the context of how they intersect with conspiracy beliefs. Second most frequently, in 46.5% of the interviews, general grievances in relation to the Covid-19 pandemic appear to induce sympathy for or identification with a “resistance movement.”

Interviewees mention, for example, health complaints caused by Covid-19, affecting themselves, or especially children, the elderly, or people with preexisting health conditions, making the measures seem disproportionate and arousing needs for resistance (D13; D19; D64). For example, one interviewee wondered what “they” were “doing to our children” and felt called to join the resistance (D49; cf. D64; D65). However, a lack of social contacts and activities (D23; D60) or financial hardship (D1; D9; D43) are also described as burdens that drive people into resistance.

Furthermore, 45.1% of the interviews involve descriptions of experiencing negative consequences of rejecting the Covid-19 measures or participating in protests. Experiences such as access restrictions, negative media coverage, and hostility from fellow citizens due to, for example, refusing to wear a mask or getting vaccinated are often associated with feelings of discrimination or stigmatization (D5; D16; D63). An injustice that is “sick and requires resistance” (D57) would legitimize protest. The latter are alleged to use brutality against a peaceful resistance movement (D35; D51; D61), which many interviewees are not prepared to tolerate and against which they sometimes take legal action (D5; D21; D32).

Lastly, in 45.1% of the interviews, individuals claim that the Covid-19 measures would curtail fundamental rights or freedoms and, therefore, must be protested. However, except for exceptional cases, when the interviewee has a legal background (D39; D44; D28), the interviewees’ references to fundamental rights seem devoid of content, merely providing political meaning to protest behavior. Usually blending into a series of other reasons for protest (D20; D30; D66), they allow interviewees to identify not only as part of a “resistance movement” but also as part of a democracy movement (D29; D41; D60). That an interviewee mentions dismay about interference in fundamental rights as the sole reason for protest remains the exception (D33).

Examining Recourses to Conspiracy Theories

After the preceding exploration of what motivates interviewees to protest lent weight to the assumption that conspiracy theories play a key role in the decision to protest, the second analytical interest can be addressed next. To examine how conspiracy beliefs motivate protest and whether they may have a radicalizing effect, it is useful to study how they relate to other statements about protest motives. Do interviewees explicitly refer to conspiracy theories to make sense of grievances or give meaning to experienced negative consequences of their protest behavior? In line with the way conspiracy theories operate, do they blame an actor, potentially the government, and develop an increasingly hostile attitude toward them?

To prepare a detailed qualitative analysis to address such questions, a co-occurrence analysis can provide directional insights into what other motives frequently occur together with conspiracy beliefs in an interview. suggests that most frequently, in 30 interviews, interviewees express conspiracy beliefs (CB) as well as report animosity from fellow citizens or negative media coverage as a social consequence of their objection to or protest against the Covid-19 measures (SC). The second most frequently co-occurring motive with conspiracy beliefs, namely in 26 interviews, is an alleged violation of fundamental rights (R). Since it has already been established that the latter, however, rarely occurs alone, it will continue to be taken into account but will be put aside for the time being in favor of the next most frequent co-occurrence, namely that of reports of confrontations with state authorities (PC) and conspiracy beliefs in 25 interviews. Finally, two other commonly co-occurring motives are health grievances (HG) and conspiracy beliefs or health grievances and reports of social consequences.

Figure 2. Interviews with co-occurrence of two protest motives. FG = Financial Grievance, HG = Health Grievance, SG = Social Grievance, SC = Social Consequence, PC = Police/penal Consequence, OC = Other Consequence, CB = Conspiracy Belief, R = Reference to Fundamental Rights.

These findings invite further investigation into how interviewees relate statements that point to conspiracy thinking and those that include reports of negative consequences of opposition to or protest against the Covid-19 measures. If an interviewee alludes to conspiracy theories while describing such negative experiences as a motive for protest, it could indicate that conspiracy theories are explicitly employed to interpret the latter. If this assertion is true, the question arises as to what effect this interpretation has on behavior.

Based on the previous theoretical considerations, special attention should be paid to indications of possible cognitive or behavioral radicalization, such as a particular hostility toward a conspirator or perceptions of an acute threat. In the following analysis, some interviews are used repeatedly as examples for comprehensibility and clarity. However, once patterns found in how interviewees relate conspiracy beliefs and reports of negative media coverage, animosity from fellow citizens, or confrontations with state authorities are presented and interpreted, other examples will support the claims.

Conspiracy Beliefs and Social Animosity

A closer look at interviews reflecting both conspiracy beliefs and resentment about interpersonal conflicts or negative media coverage reveals that the latter often results from interviewees’ own experiences and that there are two ways in which interviewees connect such statements. First, conspiracy beliefs may induce protest behavior, which then results in experiencing criticism by other citizens or negative media coverage. Second, some interviewees embed such adverse experiences in a conspiracy theory. Since belief in a conspiracy was sometimes already motivating their protest and possibly the cause of fellow citizens’ hostility, the interviewee can draw on this belief and regain their negative experience as confirmation of their beliefs.

Several interviewees’ explanations of how they became active in an imagined “resistance movement” show that a turn to conspiracy theories initially encouraged their protest. An interview with an artist (D36) exemplifies how a turn to conspiracy theories induces protest, which then sparks criticism from fellow citizens. As his “wake-up moment” that inspired him to organize his first vigil and write journalistic and artistic pieces against the Covid-19 measures, he recalls his increasing sympathy for well-known conspiracy theorists and “violent physical reactions” to a television interview with Bill Gates (Ibid.). Furthermore, he considers personal attacks on social media due to his participation in protests as defamations of critics in times of “societal maldevelopments” (Ibid.). This interpretation points to another way in which conspiracy beliefs and experiences of social animosity are related.

Regardless of whether the protest behavior was already fueled by conspiracy beliefs or had other origins, the second way statements reflecting conspiracy beliefs are related to reports of social animosity is that some interviewees embed the latter in the former. For example, a pensioner couple (D35) expresses outrage about repeatedly being called “Covidiot” and laments over an “affinity of our beloved fellow human beings (…) for denunciation” (Ibid.). However, as this wording suggests, instead of holding fellow citizens responsible for such unpleasant experiences, the latter blend into a worldview in which the Covid-19 measures follow a “completely different plan,” and Germany is developing into a “final totalitarianism” (Ibid.).

The sense-making function of such conspiracy theories enables the couple to process unpleasant insinuations by interpreting them as signs of their fellow citizens’ manipulation. Moreover, once other citizens are absolved of their agency, their criticism loses substance, reinforcing rather than diminishing the conviction that protest is warranted. Thus, for the pensioner couple, the experience of being called a “Covidiot” validates that they face a malevolent “Covid-regime.”

Such “explaining away” of adverse experiences with conspiracy theories occurs in several interviews, and, as with the pensioner couple, it is more often an entire regime that is identified as hostile to the “resistance movement” instead of a conspiratorial government. Additionally, other interviews provide insights into other manifestations and specificities of this link. For example, several adverse experiences embedded in conspiracy theories reflect personal disappointments. One interviewee sees the distancing of her employer and house bans, which she perceives as humiliation and ostracism, as evidence of others being unwitting victims of a “fascistoid structured hygiene and health dictatorship” by ruling elites (D60; cf. D66).

Furthermore, the diagnosis of totalitarian developments in Germany is often associated with reports of negative media coverage, constituting another experience of social animosity. According to the sense-making process described above, a former police commissioner (D22), for example, interprets negative media coverage of the “resistance movement” as propaganda typical of a totalitarian regime. Similarly, various interviewees tend to draw parallels to the Nazi regime to interpret alleged discrimination against others. For example, one interviewee describes Germany resembling the Nazi regime when she witnesses her daughter being pushed for not wearing a face-covering (D20; D63; D69).

Having highlighted that conspiracy belief either causes social animosity or that the latter is interpreted with the former, the analysis turns to how statements expressing conspiracy beliefs and reports about another adverse experience, namely the confrontation with state authorities, are related in the interviews.

Conspiracy Beliefs and Confrontations with State Authorities

As the category-based analysis has shown, interviewees regularly resent state authorities’ behavior toward the “resistance movement.” Like reports of social animosity, those of police violence or house raids may be the result of behavior that conspiracy beliefs already triggered. For example, someone complaining about body searches at a protest event may have attended because they wanted to show “resistance” to alleged dictatorial developments in Germany. Likewise, it is evident that some interviewees interpret these confrontation experiences with recourse to conspiracy theories.

However, there is a significant difference between this sense-making process and the embedding of experiences of social animosity in conspiracy theories, especially regarding its effect, which will be discussed later. The perpetrator of the negative experience is already a state authority and not a fellow citizen whose actions can be explained away as a consequence of manipulation or propaganda. Instead, interviewees are directly confronted by a representative of the “Covid-regime,” either directly or indirectly, as a member of a “resistance movement.” In the interpretation of social animosity, the evil intentions of state authorities are only recognized through the behavior of fellow citizens, and a “Covid-regime” is identified as a context fostering hostility and thus creating an oppressive environment for individuals in “resistance” to the Covid-19 measures. However, if someone comes into direct conflict with a state authority, this experience is often interpreted as an attack by the latter on the “resistance movement” or the individual. In some cases, the state is consequently perceived as an abstract existential threat.

The interview with the pensioner couple (D35) is a particularly fitting example because it was conducted during a protest and interrupted by police action. The couple’s subsequent reaction shows that they immediately embed what happened in conspiracy theories. They interpret the police’s request to pick up their “No Third Dictatorship” posters in the police department responsible for state protection as a sign of the state’s increasing hostility toward its critics. This interview, like others, culminates in dystopian visions of the future whose imminence renders resistance a necessity. The pensioner couple fears a “miserable existence as a well-protected and much-loved zoo animal” (Ibid.), while other interviewees warn of imminent enslavement (D67) or a total crash (D29).

As noted earlier, there are also instances where an interviewee describes a confrontation with a state authority as a personal threat and detects a conspiracy explicitly directed against themselves. For example, the former police commissioner (D22) reports being repeatedly approached by the police during street protests and sees this as state authorities’ attempt to silence him. With phrases characteristic of conspiracy beliefs, he describes it as “very clear” that there was a political agenda to “prevent [him] from speaking in public and to disregard [his] health” (Ibid.). However, the interview with the former police commissioner also highlights that an interpretation of a confrontation with state authorities as a personal threat and a general conspiracy against a “resistance movement” are not mutually exclusive. Alleged attempts to silence him are regarded as evidence of general totalitarian developments in Germany (Ibid.).

What is noticeable here, as in other interviews where such interpretations occur, is that the imagination of an antagonist remains relatively vague. Like the interpretation of social animosity, the malicious out-group seems to be an abstract idea of a “Covid-regime” involving several conspiring state authorities, such as the police, government, and judiciary. For example, one interviewee reports how she was detained and humiliated by police officers and suspects that her previous outing as an abuse victim was used to “silence her through such attacks” (D21). Another interviewee interprets a raid as a deliberate attempt to ruin him economically and his reputation (D39). Who exactly “they” are remains open, but the idea of the state system as a threatening context producing hostile actors, such as police officers, permeates many interviews where such interpretations occur.

Radicalization Catalyzed by Recourse to Conspiracy Theories in Processing Negative Experiences

The previous part of the analysis has shown that the interpretation of negative media coverage, hostility by fellow citizens, and confrontations with state authorities with the theory of a malevolent “Covid-regime” is associated with increasing hostility toward the status quo as well as feelings of acute threat. The “Covid-regime” is either perceived as a danger to society and the “resistance movement” or as a threat against the interviewee. Dystopian scenarios also appear in other interviews where interviewees suspect that authorities will soon start shooting at protesters (D41), introduce camps or waterboarding (D63), or use vaccination to carry out genocide (D20). Such statements point to conspiracy theories as a breeding ground for cognitive radicalization, as they indicate an increasing hostility toward a supposed conspirator as well as a growing sense of existential threat. This mindset lays the groundwork for viewing violent action against all those sustaining the “Covid-regime” as legitimate self-defense or considering system change necessary to prevent further alleged crimes.

In some interviews, interviewees make statements about having changed or wanting to change their protest behavior and that this happened after an interpretation of negative experiences with conspiracy theories of a “Covid-regime” whose malicious intentions are perceived as a hostile threat. Overall, 19 interviews include accounts of experiences of social animosity and confrontations with state authorities, signs of conspiracy thinking, and suggest a change in protest behavior. Moreover, remarks pointing to behavioral changes occur almost exclusively in interviews that contain conspiracy thinking and accounts of adverse experiences, suggesting that the latter do not necessarily impact protest behavior but that there is an association, nonetheless.

Protest Intensification and Mobilization against a “Covid-Regime”

First, some interviews suggest that when someone experiences social animosity due to their opinions or protest against the Covid-19 measures, they become even more convinced of a need to protest or turn to a form of protest they consider more effective to challenge or confront the alleged conspirator and which can no longer be regarded as normatively exercising the democratic right to protest. This is usually the case when an interviewee identifies a “Covid-regime” as a threat to society and the resistance movement and believes resistance is necessary to stop totalitarian developments.

For example, after publishing a newspaper issue exhibiting conspiracy beliefs and containing Covid-denying texts, one interviewee received numerous emails and phone calls attacking him personally and questioning his opinions (D15). Moreover, he recalls being called a “Covid- denialist” in the local news. In his interview, he makes sense of these events by interpreting them with a conspiracy theory of dark forces, claiming that he has hit their “nerve.” Later, he also expresses the conspiracy belief that the crisis was staged by “pandemic drivers” who would plan a hostile take-over of society. Reacting to the personal attacks, he explains having “devoted the next newspaper issue exclusively to the current topic” (Ibid.).

This example demonstrates how the attempt to “explain away” unpleasant conflicts with fellow citizens and the media using a conspiracy theory makes the interviewee regard this as evidence of a vast conspiracy posing a continuous threat and readjust his behavior in response. The conviction of a malicious conspiracy behind the pandemic and that fellow citizens’ hostility results from their lack of knowledge motivates the interviewed publicist to enlighten them about the threats of a hostile take-over of society in subsequent newspaper issues (Ibid.).

Similarly, a pensioner first describes losing friends due to her rejection of the Covid-19 measures and links these experiences to the conviction that the Covid-19 pandemic follows a destructive plan (D66). Resentful about her local newspaper criticizing protests against the Covid-19 measures, she decides to register a demonstration for the first time. While the publisher (D15), with his strengthened commitment to enlighten others through alternative media, strives to set fellow citizens against conspiratorial forces, the pensioner sticks to a legitimate exercise of protest but feels compelled to intensify it.

Either way, making sense of social animosity by resorting to a conspiracy theory that identifies the experience’s cause in a hostile actors’ plot against the resistance movement thus contributes to protest being directed more directly against the alleged conspirator. For the interviewees, the conspirator becomes an opponent against whom it is insufficient to continue with the previous form of protest. Instead, they see the need to develop new or intensify previous strategies to become active for the sake of a supposedly oppressed majority and set citizens against a “Covid-regime.”

Declarations of War against a “Covid-Regime” and Anticipated System Change

Second, as previously highlighted, interviewees who recall a confrontational experience with state authorities often interpret this as a conspiracy directed explicitly against the “resistance movement” or themselves. Especially in the latter’s case, this sense-making process can translate into a particularly hostile attitude against state authorities and impact protest behavior since the state authorities are thereby considered as conspiring to harm the individual and thus an existential threat.

For example, an entrepreneur interprets a police raid as a deliberate attempt to terrorize him (D17). This, in turn, motivates him to seek retaliation and intensify his “resistance.” When asked if he was intimidated, the interviewee replies: “Certainly not. Also, and especially because I am traumatized by this situation, I must do something about it. Right now” (Ibid.). Similarly, the former police commissioner (D22) describes how he was arrested at a protest and forced to take a rapid Covid-test in the presence of armed police officers. He explains feeling “raped” and “traumatized” and subsequently announces that he will “fight as long as [he] can breathe and stand” (Ibid.).

In addition to such declarations, there are indications in some interviews that interviewees consider system change desirable, possible, or even probable. This is also exemplified by the former police commissioner (D22), the founder of an association called “Uniformed Personnel in Resistance.” Previously, the analysis found that he interprets his confrontations with state authorities as hostile intentions against him personally and subsequently expresses a combative attitude toward these actors, whose behavior he considers as evidence of totalitarian development. His association aims to recruit police officers and other state authorities for the “resistance movement” and thus set them against the state system.

By doing so, he seems to be preparing a subversion of the state system, an usurpation, although his behavior, at least according to his interview statements, remains nonviolent. Similarly, another interviewee describes plans for a citizens’ assembly in his village, delegitimizes local power structures, and wants to fundamentally reshape them (D38). Furthermore, some interviewees also indicate a withdrawal from societal life, which can be additional signs of a breakaway from mainstream society. This includes deciding on a lifestyle of a self-sufficient person to be prepared in case of emergency (D18; D58) or considering emigrating (D23) and joining “like-minded communities” abroad (D58).

Even though there is no space for a detailed review here, a look at some media reports about what interviewees were charged with corroborates the interpretation of these mindsets, decisions, and plans as groundwork for radicalization. For example, the organizer of the citizens’ assembly is now a well-known “Reichsbürger” [Reich citizen] who denies the German state’s right to exist.Footnote75 A doctor who was raided for producing forced vaccine certificates (D39) was reported for making the Hitler salute at a protest event,Footnote76 while the policeman and founder of “Uniformed Personnel in Resistance” (D22) was reported for carrying a pocketknife at a demonstration.Footnote77 Lastly, the house search of the entrepreneur (D17) was carried out on suspicion of assassination plans, and similarly, weapons were confiscated from one of the earlier interviewees (D6).Footnote78

In the following, the analysis results will be discussed together and with recourse to the theory on the qualities and effects of conspiracy theories. Thus, it can finally be interpreted to what extent conspiracy theories not only mobilize resistance against the Covid-19 measures but can also catalyze cognitive or behavioral radicalization.

Discussion of Empirical Findings

The preceding analysis sought to investigate empirically, based on 71 interviews from the magazine “Demokratischer Widerstand” with supposedly ordinary citizens portraying a “resistance movement” against the German Covid-19 measures, how Covid-19 conspiracy theories affect the desire to protest and whether they can fuel a protester’s radicalization. As discussed in the theory section, particularly anti-government conspiracy theories seeing Germany on the way to a dictatorship have a bridging function in the heterogeneous protests and may foster anti-government extremism. This is because they mark the government as a threatening enemy and thus provide a framework for increasing alienation and delegitimization that can ultimately legitimize the overthrow of the government and violence as self-defense.Footnote79

Search for Meaning, Sense of Moral Obligation, and Outrage at a “Covid-Regime”

The category-based analysis supported the underlying theoretical assumption that conspiracy theories are particularly common motives for protest. Moreover, the interviews confirmed a frequent observation that protesters believe Germany to be on a path to a dictatorship, triggering an urge to join a “resistance movement.”Footnote80 This history-relativizing distortion and the appropriation of terms such as anti-fascist resistance give some protesters the impression that they are morally obliged to protest and act selflessly in a preventive manner.

Furthermore, the category-based analysis highlighted that, in addition to conspiracy theories, personal grievances caused by the pandemic mobilize people to various forms of protest. This can be interpreted as reflecting the unsettling disruption of many daily lives and anticipated perceived loss of control through the pandemicFootnote81 and suggests that protest generally provides an outlet for frustration and distress. The focus on health complaints of children, the elderly, or people with preexisting health conditions is, like historical analogies, exemplary of an impression of having no choice but to behave morally right by protesting.

Another striking protest motive is the experience of unpleasant encounters interviewees make or observe because of their opinions or protest behavior, including negative media coverage, hostility from fellow citizens, or conflicts with state authorities. Searching for answers to how interviewees employ statements reflecting conspiracy beliefs, a co-occurrence analysis showed that they frequently occurred together with accounts of adverse experiences. Such a finding suggests that being called a “Covidiot” or being detained by the police may create additional epistemic needs for which conspiracy theories can provide attractive remedies.

Indeed, some interviewees were found to explicitly use conspiracy theories to interpret these experiences in a way that empirically confirms conspiracy theories’ theoretical functionality. Unpleasant media coverage, animosity by fellow citizens, or conflicts with state authorities are given meaning by attributing their cause to a conspiracy. However, in a subtle deviation from the theoretical propositions, the analysis showed that it is not only the government that interviewees expose as behind a malicious plot. Instead, identifying a “Covid-regime” reflects resentment against the political order and everyone influencing the rules and norms of society, including but not limited to the government.Footnote82 Consequently, not only anti-government conspiracy theories spread within the imagined “resistance movement” but also those that trigger resentments against the political and societal status quo.

System Critique, Delegitimization of the State, and Fantasies of Change

The report of hostility from fellow citizens is often accompanied by the perception of a “Covid-regime” as a threatening condition. However, contrary to a common assumption in the literature on conspiracy theories, other citizens calling interviewees “Covidiots,” for example, are not accused of complicity in a plot,Footnote83 but their behavior is explained as a lack of knowledge about the conspiracy.Footnote84 Thus, protesters regard such animosity as a symptom of the machinations of this very “Covid-regime,” thereby increasing the validity of this conspiracy theory.Footnote85

However, the accusation that the Covid-19 measures are intended to reestablish a dictatorship is also associated with a withdrawal of trust in political decision-makers or even delegitimizing the state’s legislative and executive. This provides the basis for non-normative and disruptive behavior, like the illegal issuance of mask exemptions. Such effects on behavior illustrate that conspiracy theories with inherent system critique merely expand the circle of antagonists to include any agents of the “Covid-regime” and, therefore, hardly differ from what was anticipated for anti-government conspiracy theories in the theoretical discussion.

The same applies to the prediction that conspiracy theories can fuel radicalization into anti-government – or rather produce ressentiments against the political order.Footnote86 For some interviewees, at least the groundwork of a catalyzing effect of conspiracy theories on cognitive radicalization could be identified, for example, in increasing hostility toward a “Covid-regime” and the perception of it as an acute danger. The interviews suggest that it is primarily the processing of adverse experiences, such as the hostility of other citizens toward the respective interviewee, negative media coverage, or physical confrontations with state authorities, that give rise to such an enemy image of the state. This can go as far as the interviewees seeing themselves, the “resistance movement,” or society threatened and feeling responsible for acting upon it.

In theory, it may follow that violence is increasingly perceived as necessary self-defenseFootnote87 or a heroic act and that this position is also accompanied by acceptance of others or one’s own use of violence.Footnote88 The present data does not provide explicit evidence of this, but this may also be due to their publicity and format.

Nevertheless, evidence of behavioral change based on conspiracy ideological interpretations of negative experiences could be found. For example, some interviewees who have experienced societal rejection and attribute this to a threatening “Covid-regime” seem to adjust their form of protest with a desire to enlighten other citizens about the unacceptability of the current “system” and to activate anti-state sentiments.

Other interviewees who have experienced confrontations with state authorities and a sense of threat against themselves or the “resistance movement” exhibit a more combative or vindictive attitude toward anyone associated with the “Covid-regime.” This ultimately corresponds with findings like those of Freeman et al., who find “noticeable high associations”Footnote89 between Covid-19 conspiracy theories and paranoia, or like those of Jolly and Paterson, according to whom people “who are most paranoid are most likely to respond violently to conspiratorially evoked anger”Footnote90 However, behaviors such as social withdrawal are more reflected in the analyzed dataset.

The interviews from the “Demokratischer Widerstand” thus paint a picture of a group of people who seem to have numerous motivations for exercising their democratic right to demonstrate against the Covid-19 measures. What is striking, however, is the high prevalence of conspiracy-theory thinking that stirs up hatred toward an abstract “Covid-regime” in which anti-democratic potential manifests itself in various forms. Nevertheless, also the compatibility of these resentments with other “extremisms” must be considered. The following remarks thus refer to the far-reaching mobilization potential from the conspiracy-ideological milieu in the context of the Covid-19 protests.

Extremist Opportunity Structures

Groups with ideologies usually assigned to the umbrella concept of the far rightFootnote91 can connect particularly well to such system critique and possibly see influencing or appropriating conspiracy theories related to Covid-19 as profitable.

An especially likely profiteer is the “Reichsbürger” [Reich citizens] movement, which categorically rejects the sovereignty of the German state as it considers Germany a company run by the Allies since the end of World War II.Footnote92 Assuming a conspiracy mentality, it stands to reason that protesters who believe in a conspiracy by a “Covid-regime” and therefore deny the legitimacy of any agents associated with it are susceptible to influence from the “Reichsbürger” movement. The empirical analysis has already indicated this by identifying one of the interviewees as a “Reichsbürger” through recourse to newspaper media. In addition, it also became known after the December raid across Germany against a group associated with the “Reichsbürger” that some of them had frequently participated in Covid-19 protests.

In the case of another interviewee, the analysis referred to reports of right-wing extremist gestures to substantiate that the empirical findings suggest signs of radicalization. Such examples appear to confirm claims that the extreme right is “in the best position to harness anti-government resentment.”Footnote93 Their ideology is often already based on system critique and considers the continued existence of an in-group as threatened by an out-group, usually foreigners or Jews, legitimizing violence as self-defense.Footnote94 Hence, extreme right groups may try to profit from Covid-19 protests, as has been empirically substantiated,Footnote95 by redirecting protesters to other enemy images to mainstream their narratives or recruit new members. For example, the idea of a “Covid regime” already serves anti-Semitic stereotypes.Footnote96

Finally, anti-state conspiracy theories and their resultant system critique are not far removed from palingenetic fantasies of fascism,Footnote97 denoting a desire for system renewal after its collapse.Footnote98 As the analysis showed, some interviewees express apocalyptic visions of manipulation, persecution, and even system breakdown. These will ultimately provide fascists with an opportunity to spread their fantasies of system overhaul, although visions of the future may differ.

The results of the empirical analysis can thus ultimately be interpreted as foreshadowing the empowerment of extremist groups, who are likely to use anti-state conspiracy theories and the accompanying delegitimization of the state opportunistically. If anti-system resentments already pose a danger of usurpation or extremist attacks against representatives of the “Covid-regime,” there is an additional danger of strengthening other extreme currents. The frequent designation of the Covid-19 protests as “open to the right”Footnote99 consequently finds affirmation, re-emphasizing the importance of understanding the nexus between conspiracy theories and radicalization, making these dynamics possible.

Limitations of the Empirical Analysis

Finally, the limitations of this study deserve a brief mention. First, its results should not be readily transferred to the whole protest scene, as it remains unclear to what extent the interviewees represent it.

Second, it must be pointed out that while protests against the Covid-19 measures may be breeding grounds or resonating spaces for anti-democratic positions, this does not mean that every person who exercises their right to protest, nor every person who believes in conspiracy theories, will become radicalized. At the same time, however, it can be expected that the number of people for whom the groundwork of or susceptibilities of radicalization are evident may be larger than the sample analyzed here suggests. After all, the editors of the “Demokratischer Widerstand” have their own tactical interests.

Conclusion

This paper shed light on the puzzling role of conspiracy theories in mobilizing individuals into a heterogeneous Covid-19 “resistance movement” in Germany and catalyzing radicalization. Based on a qualitative research desideratum on how particular conspiracy theories may motivate their believers to protest the Covid-19 measures and foster radicalization, it explored the research questions: How do conspiracy theories mobilize individuals into “resistance” against the Covid-19 measures? and What role do they play in catalyzing radicalization? Initial theoretical reflections were complemented by insights from an empirical investigation of 71 interviews from the magazine “Demokratischer Widerstand.” Together, they provide an answer to the research question offering relevant insights for theory and practice.

Theoretical and Empirical Insights

A theoretical examination of conspiracy theories in the context of the pandemic drew attention to anti-government conspiracy theories, especially the theory of a malevolent government whose Covid-19 measures seek to turn Germany into a dictatorship, as milieu-binding and thus decisive for the heterogeneity of the supposed “resistance movement.” Additionally, it was found that they can catalyze radicalization by enabling a protester to develop an increasingly hostile attitude toward the out-group government and legitimize violence as self-defense against this conspirator.

An empirical examination of the role of conspiracy theories in protest mobilization and radicalization added to this picture. A qualitative content analysis of 71 interviews from the magazine “Demokratischer Widerstand” first showed that conspiracy theories are not the only but a frequent protest motive. Subsequently, it demonstrated that interviewees explain negative experiences, such as rejection from fellow citizens, negative media coverage, or confrontations with state authorities, using conspiracy theories following specific patterns.

In the hostility toward a “Covid-regime,” stemming from the perception of the latter as oppressive and sometimes endangering the individual, as a harbinger of dictatorship or apocalypse, lies the potential of conspiracy theories to fuel anti-democratic attitudes and thus catalyze cognitive radicalization. Initial behavioral changes based on these attitudes have also already been identifiable.

Thus, interviewees’ statements reveal the structure and effects of anti-government conspiracy theories as predicted in theory, but they produce a delegitimization of the state and political order and not just anti-government attitudes. Such resentments, in turn, constitute an opportunity for other extremist actors to spread their ideologies.

Relevance and Further Research

With these findings, the paper contributes to research on the role of conspiracy theories during times of social crisis, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, and offers insights of practical relevance. It suggests that anti-government and anti-state conspiracy theories characterize heterogeneous Covid-19 protests and that marking state authorities and especially a “Covid-regime” as enemies may catalyze cognitive or eventually even behavioral radicalization.

Breaking away from the one-dimensional spectrum of extreme ideas that often remains a starting point in research on extremism appears necessary to understand heterogeneous movements that can endanger the democratic order, such as currents within the Covid-19 protests, but also similar phenomena, like within demonstrations against refugees or relating to the war in Ukraine. Moreover, the references to German history and appropriation of anti-fascist resistance raise questions about the manifestations, workings, and effects of anti-state conspiracy theories in other countries, which invites cross-country comparative investigations.

The paper also revealed that the development of anti-democratic attitudes and aggravation of protest behavior is particularly linked to processing negative experiences with fellow citizens or authorities. This finding is of practical relevance, as it emphasizes that the way society and decision-makers deal with conspiracy theorists can impact the potential danger they pose. Hence, this relationship must be further investigated theoretically and empirically, for example, by analyzing other data, such as social media communications, or observing individual protesters’ attitudinal and behavioral changes over time. The latter could especially verify whether this paper’s suggestions that anti-government and anti-state conspiracy theories can catalyze radicalization hold and could provide further insights into when and why this is the case. Ultimately, this can inform recommendations on how society and decision-makers should deal with conspiracy believers.Footnote100

Finally, this paper has also shown that many motives, such as financial or social grievances, or socio-psychological states, such as insecurity and perceived loss of control, underlie protest behavior. Consequently, adequate crisis management and communication could already reduce protests and conspiracy beliefs, thereby preempting anti-democratic sentiments and fantasies of system change.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on the author’s postgraduate dissertation, which was awarded the Lord Sedwill Handa CSTPV Dissertation Prize. The author would like to thank the Handa Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence and the supervisor of her MLitt dissertation, Dr. Bernhard Blumenau, for their support.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Jonathan White, “Emergency Europe after Covid-19,” in Pandemic, Politics, and Society: Critical Perspectives on the Covid-19 Crisis, ed. Gerard Delanty (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2021), 85–86.

2 “Global Protest Tracker,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, accessed June 24, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/publications/interactive/protest-tracker.

3 “Demonstrationsbereitschaft und Reaktanz,” Cosmo Consortium, last modified August 11, 2022, accessed April 25, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/publications/interactive/protest-tracker; Edgar Grande, Swen Hutter, Sophia Hunger, and Eylem Kanol, “Alles Covidioten? Politische Potenziale des Corona-Protests in Deutschland” (Discussion Paper ZZ 2021-601, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, Berlin, 2021); Pia Lamberty, Josef Holnburger, and Maheba Goedeke Tort, “CeMAS-Studie: Das Protestpotential während der COVID-19-Pandemie” (CeMAS, 2022), https://cemas.io/blog/protestpotential/.

4 Wolfgang Benz, “Querdenken: Usurpation und Radikalisierung - Verweigerer und Aufsässige,” in Querdenken: Protestbewegung zwischen Demokratieverachtung, Hass und Aufruhr, ed. Wolfgang Benz (Berlin: Metropol, 2021), 7; Martin Machowecz, “Wutbürger 2.0,” Die Zeit, September 2, 2020, https://www.zeit.de/2020/37/protest-wutbuerger-corona-politik-fluechtlingskrise-demokratie?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F (accessed July 7, 2022).

5 Juliane Wetzel, “Antisemitismus - Bindekitt für Verdrossene und Verweigerer,” in Querdenken: Protestbewegung zwischen Demokratieverachtung, Hass und Aufruhr, ed. Wolfgang Benz (Berlin: Metropol, 2021), 58.

6 Lea Gerster, Richard Kuchta, Dominik Hammer, and Christian Schwieter. “Stützpfeiler Telegram: Wie Rechtsextreme und Verschwörungsideolog:Innen auf Telegram ihre Infrastruktur ausbauen” (Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 2021).

7 Bundesministerium des Inneren und für Heimat (BMI), “Verfassungsschutzbericht 2021” (BMI22003, 2022), 116, https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/publikationen/themen/sicherheit/vsb-2021-gesamt.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3.

8 Ulrike M. Vieten, “The ‘New Normal’ and ‘Pandemic Populism’: The COVID-19 Crisis and Anti-Hygienic Mobilization of the Far-Right,” Social Sciences 9, no. 9 (2020): 19, https://doi.org/10.3390/SOCSCI9090165; BMI, “Verfassungsschutzbericht 2021,” 18.

9 Fabian Virchow and Alexander Häusler, “Pandemie-Leugnung und extreme Rechte in Nordrhein-Westfalen” (NRW-Kurzgutachten, Core-nrw, 2020).

10 Heike Kleffner and Matthias Meisner, “Virus 2.0.,” in Fehlender Mindestabstand: Die Corona-Krise und die Netzwerke der Demokratiefeinde, ed. Heike Kleffner and Matthias Meisner (Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 2021), 16; Pia Lamberty and Katherina Nocun, “Ein Brandbeschleuniger für Radikalisierung? Verschwörungserzählungen während der Covid-19 Pandemie,” in Fehlender Mindestabstand: Die Corona-Krise und die Netzwerke der Demokratiefeinde, ed. Heike Kleffner and Matthias Meisner (Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 2021), 117.

11 Mohammed Hafez and Creighton Mullins, “The Radicalization Puzzle: A Theoretical Synthesis of Empirical Approaches to Homegrown Extremism,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 38, no. 11 (2015): 960-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2015.1051375.2015, 960.

12 John M. Berger, Extremism (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2018), 36; Malaz Shahhoud and Lieke Wouterse, “Conclusion Paper: Preventing Possible Violence Based on Anti-Government Extremism on the Local Level” (Radicalisation Awareness Network, 2022); Benz, “Querdenken,” 7.

13 Florian Flade, Martin Kaul, Sebastian Pittelkow, Katja Riedel, und Sarah Wippermann, “Fantasien vom Umsturz,” Tagesschau, December 7, 2022, https://www.tagesschau.de/investigativ/ndr-wdr/razzia-reichsbuerger-staatsstreich-geplant-101.html.

14 Gary Ackerman and Hayley Peterson, “Terrorism and COVID-19: Actual and Potential Impacts,” Perspectives on Terrorism 14, no. 3 (June 2020): 61.

15 Bettina Rottweiler and Paul Gill, “Conspiracy Beliefs and Violent Extremist Intentions: The Contingent Effects of Self-Efficacy, Self-Control and Law-Related Morality,” Terrorism and Political Violence 34, no. 7 (2020,): 2, https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2020.1803288; Amanda Garry et al., “QAnon Conspiracy Theory: Examining its Evolution and Mechanisms of Radicalization,” Journal for Deradicalization 26 (2021): 152–216; Shruti Phadke, Mattia Samory, and Tanushree Mitra, “Pathways through Conspiracy: The Evolution of Conspiracy Radicalisation through Engagement in Online Conspiracy Discussions” (Proceedings of the Sixteenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 2022, Atlanta, Georgia: Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, 2022), 770–81.

16 Garry et al., “QAnon Conspiracy Theory,” 154; Abdul Basit, “Conspiracy Theories and Violent Extremism: Similarities, Differences and the Implications,” Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 13, no. 3 (2021): 9.

17 Grande et al., “Alles Covidioten?” 3; BMI, “Verfassungsschutzbericht 2021,” 120.

18 Benjamin Lee, “Radicalisation and Conspiracy Theories,” in Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories, ed. Michael Butter and Peter Knight, 1st ed. (London: Routledge, 2020), 354; Jamie Bartlett and Carl Miller, The Power of Unreason: Conspiracy Theories, Extremism and Counter-Terrorism (London: Demos, 2010).

19 Frenett and Joost, “Conclusion Paper,” 1; Virchow and Häusler, “Pandemie-Leugnung und extreme Rechte,” 36.

20 Michael Butter, “Verschwörungstheorien: Nennt sie beim Namen!,” Die Zeit, December 28, 2020, https://www.zeit.de/gesellschaft/2020-12/verschwoerungstheorien-corona-krise-wort-des-jahres-2020/komplettansicht.

21 Karen M. Douglas et al., “Understanding Conspiracy Theories,” Political Psychology 40, no. S1 (2019): 4, https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12568.

22 Karen M. Douglas, Robbie M. Sutton, and Aleksandra Cichocka, “The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 26, no. 6 (2017): 538, https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417718261; Cas Sunstein, Conspiracy Theories and Other Dangerous Ideas (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014), 3.

23 Viren Swami et al., “Conspiracist Ideation in Britain and Austria: Evidence of a Monological Belief System and Associations between Individual Psychological Differences and Real-World and Fictitious Conspiracy Theories,” British Journal of Psychology 102, no. 3 (2011): 443–63, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.2010.02004.x; Martin Bruder et al., “Measuring Individual Differences in Generic Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories across Cultures: Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire,” Frontiers in Psychology 4 (2013): 225, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00225.

24 Michael J. Wood, Karen M. Douglas, and Robbie M. Sutton, “Dead and Alive: Beliefs in Contradictory Conspiracy Theories,” Social Psychological and Personality Science 3, no. 6 (2012): 767–73, https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611434786.

25 Roland Imhoff and Martin Bruder, “Speaking (Un‐) Truth to Power: Conspiracy Mentality as a Generalised Political Attitude,” European Journal of Personality 28 (2014): 26, https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1930; Joseph E. Uscinski and Joseph M. Parent, American Conspiracy Theories (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

26 Jonas H. Rees and Pia Lamberty, “Mitreißend Wahrheiten: Verschwörungsmythen als Gefahr für den gesellschaftlichen Zusammenhalt,” in Verlorene Mitte - Feindselige Zustände: Rechtsextreme Einstellungen in Deutschland 2018/19, by Andreas Zick, Beate Küpper, and Wilhelm Berghan, ed. Franziska Schröter (Berlin: Karl Dietz Verlag, 2019), 207.

27 Van Prooijen and Douglas, “Belief in Conspiracy Theories,” 898.

28 Butter and Knight, “The History of Conspiracy Theory Research.”

29 Lamberty and Nocun, “Ein Brandbeschleuniger für Radikalisierung?” 120-21; Daniel Freeman et al., “Coronavirus Conspiracy Beliefs, Mistrust, and Compliance with Government Guidelines in England,” Psychological Medicine 52, no. 2 (January 2022): 251–63, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001890.

30 Douglas, Sutton, and Cichocka, “The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories.”

31 Neophytos Georgiou, Paul Delfabbro, and Ryna Balzan, “COVID-19-Related Conspiracy Beliefs and Their Relationship with Perceived Stress and Pre-Existing Conspiracy Beliefs,” Personality and Individual Differences 166, no. 110201 (2020): 2, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110201. Jan-Willem van Prooijen and Nils B. Jostmann, “Belief in Conspiracy Theories: The Influence of Uncertainty and Perceived Morality,” European Journal of Social Psychology 43, no. 1 (2013): 109–15, https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1922.

32 cf. Bruder et al, “Measuring Individual Differences;” Jan-Willem van Prooijen and Michele Acker, “The Influence of Control on Belief in Conspiracy Theories: Conceptual and Applied Extensions,” Applied Cognitive Psychology 29, no. 5 (2015): 753–61, https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3161.

33 Douglas, Sutton, and Cichocka, “The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories.”

34 Clara Schießler, Nele Hellweg, and Oliver Decker, “Aberglaube, Esoterik und Verschwörungsmentalität in Zeiten der Pandemie,” in Leipziger Autoritarismus Studie 2020. Autoritäre Dynamiken: Alter Ressentiments - Neue Radikalität, ed. Oliver Decker and Elmar Brähler (Gießen: Psychosozial-Verlag, 2020), 301.

35 Jovan Byford, Conspiracy Theories: A Critical Introduction (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 4. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230349216.

36 Van Prooijen and Douglas, “Belief in Conspiracy Theories,” 901.

37 Michael Barkun, A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America (Berkeley, Calif.; London: University of California Press, 2003), https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520238053.001.0001.

38 Robert Andreasch, “Die Geschichte wiederholt sich”: Bayerische ‘Coronarebellen’ im Sophie-Scholl-Widerstand,” in Fehlender Mindestabstand: Die Coronakrise und die Netzwerke der Demokratiefeinde, ed. Matthias Meisner and Heike Kleffner (Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 2021), 58. Benz, “Querdenken,” 14-15; Jasmin Degeling, Hilde Hoffman, and Simon Strick, “‘Mein Handy hat schon COVID-19!’ Überlegungen zu digitalem Faschismus unter Bedingungen der Corona-Pandemie,” Kultur & Geschlecht 26 (February 2021).

39 Schießler, Hellweg, and Decker, “Aberglaube, Esoterik und Verschwörungsmentalität,” 114.