Abstract

The vast majority of those engaging with radical ideas do not pursue radicalization trajectories to an endpoint of violent extremism. However, empirical research charting journeys of “non-radicalization” remains scarce. This article draws on ethnographic research tracing pathways through an “extreme right” milieu. It identifies a range of journeys – of partial, stalled and non-radicalization – and the complex interweaving of political and personal grievances as well as affective and situational factors, which shape movement both toward and away from cognitive and behavioral extremism. Studying these pathways helps understand what prevents those engaging in radical milieus from crossing the threshold to violent extremism.

That the vast majority of those who engage with radical ideas do not pursue radicalization trajectories to their presumed endpoint of violent extremism is axiomatic.Footnote1 However, empirical research charting engagements with radical milieus that might be described as journeys of partial, stalled or non-radicalization, is scarce. This is partially an issue of research design; defining the parameters of study of a “non-phenomenon” is inherently challenging.Footnote2 Moreover, the tendency of studies to sample on the dependent variable – selecting for study only those who become violent extremists while excluding those who move in the same milieu but do not – naturally confirms the presupposition that violence characterizes the radicalization endpoint.Footnote3 This article argues that, while, as Fine and Corte put it “ignoring cases in which ‘the dog doesn’t bark’”,Footnote4 is methodologically neater, it is essential that we study those journeys that are still in process and have not yet manifested in acts of, or support for, violent extremism and, in the vast majority of cases, will never do so. This article traces the pathways of a small number of individuals participating in a broader study of an “extreme-right”Footnote5 milieu in the U.K. to illuminate the role of three key factors in shifts both toward and away from extremism. These are: degree of attitudinal and behavioral extremism (participation in violence); the relationship between political and personal grievances in driving radical action; and the role of situational and emotional/affective mediating factors in shifts along the radicalization-non-radicalization continuum. In tracing these journeys, the analysis focuses on what the study of these journeys in situ and still in process can add to our understanding of radicalization and non-radicalization.

Milieus, Trajectories and Resistance to Violent Extremism

Radicalization is a profoundly societal phenomenon – a process shaped by exposure to, and engagement in, specific social settings or radical groups.Footnote6 To advance our understanding of radicalization as process, it follows, we need to consider how individuals interact, over time, in and with radical settings and with what outcomes. Existing scholarship around three key concepts in radicalization studies – milieus, trajectories and resistance to violent extremism (non-radicalization) – are central to this endeavor.

Radical milieus are the settings in which trajectories of radicalization and non-radicalization unfold. They are social formations though which collective identities and solidarities are constructed and take multiple (religious, ethnic or political) forms,Footnote7 may, or may not, be territorially rooted and display varying degrees of cohesiveness. They provide the immediate social environments from within which those engaged in violent activity can gain affirmation for their actions; more routinely, they constitute the space in which “grievance” narratives and “rejected” or “stigmatized” knowledge are shared and come to form the basis of internal cultures.Footnote8 Thus, milieus may be either physical or virtual (usually they are both) and are emotional as well as ideological spaces providing opportunities for voicing anger at perceived injustice, identifying like minds or shared hurts and giving meaning to, and making sense of, life. They are also sites where important bonds are forged with others, especially for individuals whose family or peer relationships have been lacking or traumatizing.Footnote9

Radical milieus are not only sites of encounter with radical(izing) messages and agents, encouraging and exacerbating violence, but often diverse and multi-dimensional social environments in which individuals may criticize or challenge the narratives, frames and violent behaviors encountered.Footnote10 Thus, milieus may act not only to drive but also constrain radicalization by offering alternative (non-militant) forms of activism or a context in which to determine one’s own understanding of extremism and “red lines” that should not be crossed.Footnote11 Nor are radical milieus static contexts, factors or sites of radicalization; the milieu is rather an evolving relational and emotional field of activity, which underpins and envelops radical ideas and behaviors.Footnote12 Radicalization does not take place in a single, stable environment but as Lindekilde et al. state “in a dynamic constellation of multiple spaces and social relationships that change over time.”Footnote13 A relational, contextual and situational approach to understanding radicalization, operationalized through an ethnographic, milieu based research design, it is argued in this article, affords the opportunity to capture this dynamic quality by engaging, over an extended period, with milieu actors.

The notion of trajectories – exemplified by Horgan’s argument for the search for the “roots” of violent extremism to be replaced by understanding “routes” to violent extremismFootnote14 – provides a conceptual tool to capture the complex and changing engagement of individual actors with the radical(izing) milieu. It allows the identification of stages through which individual actors progress toward violent extremism and important transitions or turning points in radicalization (and deradicalization) journeys.Footnote15 It intrinsically recognizes multiple pathways into extremismFootnote16 and that different people on a shared pathway (active in the same movement, for example) have varying outcomes.Footnote17 In so doing, it overcomes some of the implicit linearity of classic models of radicalization, such as that of Wiktorowicz (2005) or Mogghadam, which envisage a combination of material, psychological, environmental and organisational/situational factors interacting to shape individual pathways to violent extremism in the form of pyramid or staircase structures in which space is progressively closed down as individuals pass through distinct stages of socialization or cross thresholds that implicitly or explicitly allow no “turning back”.Footnote18 It also accommodates a complex understanding of the relationship between the radicalization of ideas and behaviors including McCauley and Moskalenko’s argument for understanding radicalization as involving separate pathways of radicalization of “opinion” on the one hand and “action” on the other.Footnote19 McCauley and Moskalenko state explicitly that they are not presenting a “stairway model” – individuals can skip levels in moving up and down the pyramids – and that there is no “conveyor belt” from extreme beliefs to extreme action. However, the endpoint envisaged in both cases is violent extremism and, since at the apex of the “opinion pyramid” are those who not only justify violence but feel a personal moral obligation to take up violence in defence of the cause, this extreme commitment nonetheless appears to lay the ground for extreme action.

A trajectories oriented approach, it is argued here, might be logically extended to consider pathways, which have not yet ended in violent extremism and may never do so. Studying ongoing journeys helps develop a more textured picture of how pathways through radical(izing) milieus unfold by directing attention to the role of agency, alongside context, situation and interaction. While engagement in the milieu might reflect a relative shift toward more extremist positions – embarkation on a radicalization pathway – individuals are not passive objects of radicalizing influences.Footnote20 The ethnographic approach adopted in the research reported on in this article allows access to individuals’ own reflections on their encounters with, and responses to, radical(izing) messages and agents and informs our understanding of a range of trajectories of partial, stalled or non-radicalization in which there is no passage into violent extremism.

The concept of non-radicalization was introduced by Cragin to capture the process, and outcome, of resistance to radicalizing messages and agents.Footnote21 Her preliminary model identified the costs of participation, the perceived efficacy of violence, social ties to the organization and moral (non)acceptability of violent action as key factors in dissuading individuals from joining terrorist groups (resistance) and leaving such organizations (desistance).Footnote22 This model was generated from a review of secondary data sources but was subsequently empirically tested through a study involving semi-structured interviews with a small number of Palestinian political activists (associated with groups pursuing a violent agenda) and a survey of Palestinian youth (aged 18 to 30) living in the West Bank.Footnote23 While the immediacy of armed conflict in the context of that study renders the choices individuals make between violent and nonviolent pathways very different to those discussed in this article, both studies are concerned with the process of resistance to radicalization among those exposed to, or engaging with, radical ideologies or violence in their milieu.

The choices individuals make are shaped not only by cost-benefit calculations in relation to participation and the efficacy of violence, however, but by a range of affective and situational and dispositional factors. Social movements scholarship has explored the role of affective practices and “reciprocal emotions” – friendship, loyalty, solidarity, love – in collective action.Footnote24 In “extreme-right”, as in other, social movements, anger related to perceived unjust action can overcome negative emotions of threat, displacement and anxiety to facilitate participation in collective action and rituals and generate positive emotional energy and a sense of “togetherness”.Footnote25 Thus, while studies of radicalization generally consider social bonds as drivers of radicalization – preexisting ties bring people into radical movements while socialization within movements encourages radicalization into violent extremismFootnote26 – these affective dimensions of groups might potentially also alleviate ontological insecurity, satisfy the longing for community or “family” among milieu actors and thus facilitate resistance to violent extremism. Work on “resilience”Footnote27 in the field of counter-extremism also provides insight into the role of individual dispositions (open-mindedness, empathy, self-control, value complexity, self-esteem, tolerance of diversity and ambiguity), which may protect against radicalization, as well as of externally generated promotive factors (dialogue, education, social safety, vigilance) in non-radicalization trajectory outcomes.Footnote28

Radicalization is understood here as a dynamic societal phenomenon, which should be studied empirically not only through retrospectively constructed narratives of those who have reached its supposed “endpoint” (support for, or participation in, political violence) but via engagement with individuals at different points in their journey and in the social settings in which they encounter radical(izing) messages and agents. In practice, the majority of those moving through radical milieus engage with, appropriate some and reject other, ideas and behaviors that they encounter there. This leads to trajectories not only of radicalization but partial, stalled or non-radicalization. While myriad factors – at societal, group and individual levels – have been identified as important in these journeys, it is less frequently recognized that these factors, in different situational and affective contexts, can both facilitate and constrain radicalization. In the study drawn on below, an ethnographic approach, engaging directly with those still on their journeys through radical(izing) milieus, is employed to illuminate how similar factors work in different contexts and trajectories, identify when and how choices are made and elaborate an understanding of shifts toward and away from extremism beyond binary outcomes of radicalization or non-radicalization. In this way, radicalization is explored not only as process but in process.

The Milieu and Its Study

This article draws on ethnographic research with a “right-wing extremist” milieu in the U.K. conducted by the author as one of nine case studies of such milieus in nine European countries (France, Germany, Greece, Malta, The Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Russia and the U.K.) undertaken for the Horizon 2020 Dialogue about Radicalisation and Equality (DARE) project.Footnote29 The overall aim of the DARE project – which studied, in parallel, ten “Islamist” milieus – was to understand young people’s everyday encounters with, and responses to, radical(izing) messages.

The U.K. milieu study reported on here consists of individuals active in movements, organizations or campaigns associated in public discourse with the “far right” or “extreme right”. Research participants reported contact with a total of 32 movements but all had been active in, affiliated with, or attended events of at least one of: the English Defence League (EDL), the Democratic Football Lads Alliance (DFLA), the British National Party (BNP), Britain First, Generation Identity (GI) or Tommy Robinson support groups.Footnote30 Thus, the object of study is not a single group or network but a milieu in the sense that it is a space – physical and virtual – in which actors encounter, engage with and respond to radical or extreme messages and those who convey them. Moreover, in practice, individuals in the milieu are quite closely connected. Tracing three relationships – “knows personally”, “is or was in same movement as” and “knows of” – revealed that all research participants are connected to at least one other and many are connected by more than one of these relationships.

I engaged with the milieu from December 2017 to March 2020, undertaking participant observation and conducting one or more semi-structured interviews with 20 individuals. Field research began with an informal meeting with a young EDL activist whose agreement to participate in the research facilitated access to milieu events and other actors. Two further “snowballs” were started subsequently by direct messaging a core member of a movement of interest, in one case, and via a “gatekeeper” known from earlier research in the other. Written informed consent was obtained prior to commencing fieldwork and revisited informally with participants throughout the research.

Key socio-demographic characteristics were recorded for all participants.Footnote31 Due to the focus of the overall project on youth radicalization, participants were younger than the wider “extreme right” scene; three quarters were under the age of 30, with the remainder in their thirties. Fifteen participants were men and five were women, which broadly reflects the gender composition of the wider scene. At the time of interview, most research participants were in employment; nine full-time and three part-time. Three were occupied in an unpaid capacity (volunteering, in activism or caring). Four were unemployed of whom two had been unable to find employment since release from prison and one for health reasons. One was in full-time education. All participants were born in the U.K. and all were white (two being of mixed White European heritage). Of the 15 who declared a religion, five were Protestant, five were Catholic, four declared an “other” Christian faith and one was pagan.

The final data set consists of 100 sources including: 61 field diary entries; 25 audio and five video interview transcripts; and nine text documents received at observed events. All materials were uploaded into an NVivo 12 database for coding and analysis employing open and axial coding. Twenty-five of the field diary entries pertain to participant observations at events related to what milieu actors call “patriotic” causes.

While privileged access to the group ensued from the researcher’s shared whiteness with research participants, this was not an “insider” ethnography; in terms of age, gender, occupational status and political viewpoint, I was an outsider.Footnote32 This means that there is an element of self-selection in the study; individuals who took part in the research were those prepared to engage in dialogue with the researcher notwithstanding the challenge to their views this might entail. Thus, the findings do not represent views across the milieu, still less those of “extreme-right” activists more generally. Indeed, the empirical analysis in this article draws on an even narrower selection of respondents in order to allow the in-depth exploration of the range of trajectories through the milieu. Following the rationale for studying radicalization in process rather than retrospectively, it should also be borne in mind that the final outcome of trajectories remains unknown; caution must be exercised therefore before “comparing” cases. Indeed all data drawn from empirical research with those active in radical milieus must be treated with caution; actors’ accounts should not be accorded privileged status or taken at face value.Footnote33 However, as Dawson argues, the explanations and reflections on their attitudes and behavior offered by active members of extremist movements broadly conform to the classic sociological definition of “accounts” (interview narratives) and thus carry similar validity providing they are subject to the same critical interrogation as other such accounts.Footnote34 Thus, notwithstanding the limits of the ethnographic method, it is argued here that the view “from inside” provides an important supplement to existing research that has followed individual paths to terrorism through open source material and is empirically limited by the material available and the lack of opportunity to interrogate those accounts directly.

Understanding Individual Pathways Complexly: From Thematic to Narrative Analysis

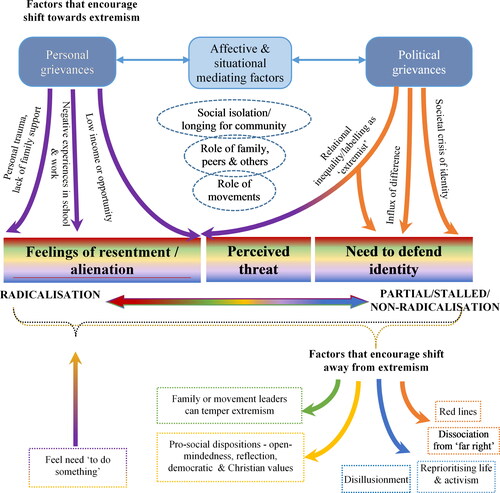

The thematic analysis of data gathered from the wider cross-national study (drawing on just under 200 interviews from nine European countries) suggested that pathways through “extreme-right” milieus are shaped by a complex interweaving of grievances and affective and situational factors (see ).Footnote35

This cross-case analysis identified a number of recurrent grievances as important in the turn to radical action. These are distinguished in drawing on McCauley and Moskalenko’s categories of political (developing as a response to political trends or events) and personal (stemming from the experience of victimization) grievances.Footnote36 However, the close analysis of individual narratives of milieu actors revealed that, in practice, these types of grievance are deeply intertwined. Political grievances – “influx of difference”, “societal crisis of identity” and “relational inequality”Footnote37 – frame what actors “stand against” and what they seek to change through their action. However, they are not purely ideological but profoundly emotionally inflected. They are experienced as changes that directly threaten societal values, ways of life and the state of “what is” and are often recounted through personal experiences of feeling angry, humiliated, treated unfairly or inappropriately.Footnote38 Personal grievances – such as personal trauma, lack of family support, negative experiences in work or school and low income or lack of opportunity – on the other hand, are unlikely to motivate to radical action unless the personal is framed and interpreted as representative of group grievance.Footnote39 This confirms Honneth’s argument that collective resistance emerges where subjects are able to articulate the feelings of disrespect endured personally within an intersubjective framework of interpretation that captures the experience of an entire group.Footnote40 Thus, while for some research participants, external events or personal experiences may radically shift their perspectives or motivate them to action – akin to the trajectories of “converts”Footnote41 – for most, they release a simmering anger or preexisting resentment or grievance.Footnote42 Similarly, those who are politically motivated to take radical action may be deterred if met with sanctions or repression while those who act out of personal grievance are less likely to view the costs as too high and to continue or even escalate their action.Footnote43

This macro level analysis also revealed that the process by which personal grievances become political, and political grievances take on profoundly personal meaning, is shaped by a wide range of situational or affective factors that, for some, contribute to a sense of collective existential insecurity and the perception of the need for radical action. Central to the analysis here, however, is the recognition that these affective and situational dimensions of participation in radical milieus may encourage also a shift away from extremism. Family members, friends and movement leaders or milieu influencers may steer individuals away from more extreme movements while encounters with more extreme elements in the milieu may lead individuals to distinguish themselves from “real” extremists and establish their own “red lines” or thresholds they will not cross. Life events or developments, as well as negative experiences of activism in the milieu, also cause individuals to pull back from radical positions or reprioritize other aspects of life over political activism.

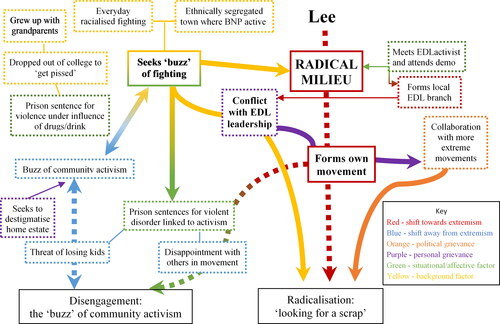

Complementing, the broad-brush picture of factors shifting “extreme-right” milieu actors along the radicalization-non-radicalization continuum presented in , the empirical discussion below draws on interview and observational data from the U.K. study to explore more complexly the individual trajectories of four respondents (see ).Footnote44 These respondents – Alice, Dan, Lee and Paul (all pseudonyms) – were aged in their twenties (Alice and Dan) or thirties (Lee and Paul) at the time of study and were selected based on two criteria. First, all had been active in the milieu over a number of years but had neither been involved in acts of terrorism nor declared their support for violence in the interests of their political cause.Footnote45 Thus, none had radicalized into violent extremism and thus their pathways constitute those of partial, stalled or non-radicalization that this article seeks to understand. Secondly, together these four pathways reflect the variance within the milieu of such non-radicalization. A detailed exploration of what prevents these individuals from crossing the threshold to violent extremism reveals different constellations, and relative importance, of three key factors: degree of attitudinal and behavioral extremism (participation in violence); the relationship between political and personal grievance in driving radical action; and how far shifts in trajectories are shaped by emotional/affective and situational factors. While the empirical analysis that follows is organized in terms of understanding each trajectory complexly, these three factors are highlighted in the analysis of each case and summarized in (below).

Table 1. Overview of trajectory characteristics.

“It’s a Matter of Survival”: Non-Violent Attitudinal Extremism in Paul’s Trajectory

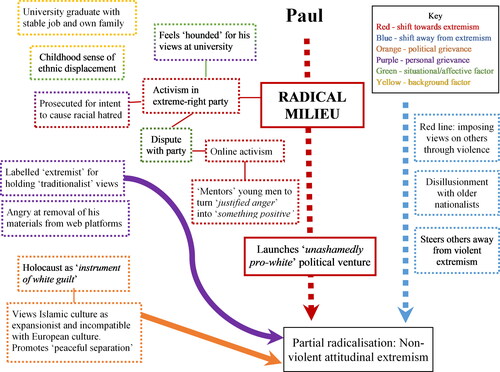

Paul was in his late thirties when interviewed and had been active politically from his early twenties. He had held a number of positions in an extreme-right political party until 2010, after which, as he put it, he “just became an independent voice”. While his journey was still in process, therefore, Paul had been moving around the “extreme-right” milieu for almost two decades (see ).

The movements with which Paul was, and currently is, affiliated, would place him furthest along the attitudinal radicalization continuum of the four respondents discussed here.Footnote46 Importantly, he not only receives and engages with extreme-right messaging but produces and disseminates it. This relative positioning on the extreme end of the spectrum within the milieu was evident from the fact that other actors in the milieu spontaneously referred to him as an example of a “real” extremist; one of the “neo-Nazi fan boys” threatening to hijack “the patriotic movement” according to one (Field diary, 13.04.2020). This comment was made after Paul launched a new political venture, which, during interview, he had said would be “unashamedly pro-white” and ensure a way for the indigenous people of all European countries “to celebrate their culture, heritage and tradition without fear of oppression or interference from either the state or other hostile groups”.

Although Paul does not adopt the terminology of Great Replacement, his attitudinal extremism is evident in the materials he produces, which promote a narrative of an existential threat to “the native White British”. He refers to the “Islamic population” as “aggressive expansionists”, believes Islamization will happen through population change, “door by door and street by street”, and argues that some areas of nearby cities and towns are already completely “transformed” by Islam. Paul recognizes that “the world is multicultural, i.e. there are many cultures” but believes that countries are better off as monocultures and some cultures – specifically Islamic cultures – are not compatible with European culture. His solution to what he sees as the ills of contemporary multiculturalism is “peaceful separation” because, he says, “human beings are happier, more contented, more at ease when they are around people who look like them, people who act like them, people who have shared belief systems, common goals”. Paul’s antisemitism also distinguishes him among the wider U.K. milieu studied. He claims Jews are disproportionately represented in “anti-Western” activities – pornography and usury – and central to the “globalism” and “internationalism” that he sees as the enemies of “western man”. He does not deny the Holocaust but believes it is used as an “instrument of white guilt”.

Notwithstanding what Paul himself describes as his “race-based outlook”, his radicalization journey stops short of the apex of both “opinion” and “action” pyramids of McCauley and Moskalenko’s “two-pyramids” model of radicalization,Footnote47 since he consistently rejects the use of violence and is careful to engage in only legal action. It is suggested below that this nonviolent, attitudinal extremism is forged from the constellation of three factors characterizing his trajectory: personal grievance results from, rather than drives, his political grievance; nonviolence is used to mark his own dissociation from extremism; and the relative insignificance of the affective dimension of the milieu, which he associates with “others” not self.

In Paul’s journey, personal grievance does not emanate from background factors but is a consequence of his views and activism. He describes his parents as aspirational – having “moved up the social scale by working hard” – and he is a university graduate himself. Although, growing up, he recalls a sense of ethnic displacement, expressed as a feeling that “the Asian kids […] stuck together”, he views such “in-group preference” as natural. Thus it is a source of grievance only due to what he terms “the societal acceptance for them to have that in-group preference” alongside the perceived illegitimacy of such preference for people like him. This is exemplified by his account of experiences at university, which he interprets as the unjust denial of white students a means of cultural expression: “if people try to set up groups, sort of like English Students or St. George’s Students Society”, he says, “they’re closed down. It’s called racist”. He also claims that those with patriotic or nationalist views were “hounded” and “threatened with being expelled” while his later experience of being prosecuted (but acquitted) for intent to cause racial hatred during an electoral campaign is interpreted as an example of how the establishment stokes extremism by seeking to silence critical voices.

Political grievance is rendered personal for Paul, therefore, primarily in relation to his own representation as “extremist”. He complains that “traditionalist” or “nationalist” views – which he describes as “morals or viewpoints that underpinned our society twenty, thirty years ago” – are currently “branded” as extremism. In his own understanding, any political, theological or ideological thought process becomes extremist only when accompanied by violence in order to impose it:

[…] opinions aren’t extremism. But they [extremists] try to bring about their opinions, and they try to express their opinions through violence, through terror. […] You can believe in an absolute Islamic caliphate. That’s not really extremism. Extremism is going out and blowing somewhere up, because you believe in the caliphate. I can believe in, you know, you can have people who believe in the Third Reich or Adolf Hitler. Now that’s not extremism until you start attacking people and imposing your will on others.

Imposing one’s views through violence is thus a “red line” for Paul and underpins his self-dissociation from those who are extremist. Indeed, Paul considers his efforts to move what he sees as a vulnerable demographic of “younger nationalists” in the milieu away from the (now proscribed) National ActionFootnote48 movement as indicative not only of his own non-extremism but “anti-extremism”. This attempt to “get the good people out of that horrible group”, as he puts it, appears to be one element of a broader sense of purpose Paul has in creating and sustaining the milieu as affective community.

The affective and situational factors so clearly shaping the journeys of the other respondents considered below appear absent from Paul’s account. However, during our second interview, Paul was angry about having had some materials removed from his YouTube channel, describing this in terms of a deep emotional loss: “I’m dying at the moment on the inside, watching my legacy just destroyed.” At the time, he had more than 90,000 subscribers to his channel, which connected him to what he refers to as “my community”. Thus, while Paul does not personally experience social isolation or longing for community, he sees his political activism as creating “a positive, outward looking community group” for those who do:

I’ve had young lads ring me up, and, “Look, I’ve got low self-esteem. I find it difficult to talk to people. I feel a bit isolated.” Because people feel isolated, because the establishment isolates people with different viewpoints. So that isolation breeds anger and frustration. And I pull people out of that isolated bubble and integrate them in the real world. I say to these people, “Look, come to the gym. Come for a…” […] I arrange camps, I arrange events. We do 10k assault courses. We have Christmas socials.

From Paul’s references to what he calls “a group of bitter old nationalists” who derive a “perverse pleasure out of younger men making the same mistakes they did”, it is evident that the early part of his engagement with the “extreme-right” milieu had left him bruised and disillusioned. Paul attributes his own survival to his personal resilience but feels protective toward younger activists who he fears would not have the same capacity to resist “thoughts or ideas of stupidity”. Thus, through his mentoring activity, he encourages them to turn their “hate and anger” into “something positive”.

The focus of Paul’s activism has shifted over the years but his pathway is characterized by relatively straight lines rather than the twists and turns of sudden radicalization or deradicalization. Even significant changes in his own personal life – such as the birth of his first child – did not stop him proceeding with the launch of his new political venture and thus exposing himself to increased scrutiny from counter-extremism agencies. In his case, it seems, starting his own family did not disrupt but confirmed the purpose of activism; the “meaning of life”, he says, lies in the creation of new life and a way of “trying to keep my race and people alive.” Thus, while his vision of activism as “a matter of survival” exemplifies Berger’s definition of extremism as the belief “that an in-group’s success or survival can never be separated from the need for hostile action against an out-group”,Footnote49 his journey remains one of partial radicalization since he consistently argues against the use of violence. Indeed, he even rejects populist protest movements, which he says allow people to “think they’re doing something. But it doesn’t lead to political change”. Thus, notwithstanding the combination of political grievance and personal grievance about his treatment within the current political system, achieving change, for Paul, means working through the current democratic, electoral system.

“I Want to Make a Difference”: Political Grievance, Emotional Receptivity and Non-Violent Activism in Dan’s Trajectory

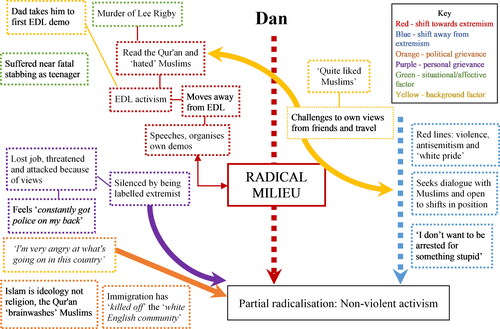

Whilst triggered by an external event, Dan’s trajectory through the milieu, like that of Paul, is characterized by relative consistency in its direction and pace rather than sharp deviations, accelerations or abrupt halts (see ). However, it is more overtly inflected than Paul’s by affective and situational factors in both shifts toward extremism and moments of encounter and reflection in which he demonstrates resilience to further radicalization.

When I first met Dan, he was twenty-three years old and designated one of the U.K.’s leading “faces of hate” by a leading anti-hate politics campaign organization.Footnote50 He is more emotionally expressive than Paul, uses words like “angry” and “hate” to articulate his frustrations and believes protest events act as important vents for such feelings. Dan’s journey into the milieu, indeed, begins with a distinct moment of affect; the murder of Lee Rigby (May 2013) which is imprinted in his mind as a vision of “this Islamist on the telly, with blood on his hands, ranting and raving”. Before that, he says, he had not known much about Islam but had “been to Muslim countries, quite liked Muslims actually at the time”. After the murder, he says, he “looked into Islam and things. Thought, “Whoa”.” This “whoa” verbally signals a moment of affect in which he is shifted to another state.Footnote51 This state is one of “hate” toward Muslims and is intensified after reading the Qur’an:

If their Qur’an is telling them to kill non-believers over a hundred times, they’re gonna do it. So in a way, I don’t blame the Muslims, because they’re getting it brainwashed into them. They’re getting it installed [sic] into them from a very young age. […] that’s where I think it’s all going wrong. I think it’s that book.

While these events are narrated as significant “turning points” in Dan’s movement into the “extreme-right” milieu, they are underpinned by a certain continuity. Dan’s dad – whom Dan describes as “not a racist” but “very anti-immigrant” – was already active in the milieu and, shortly after Lee Rigby’s murder, took Dan with him to an EDL demonstration. Dan went on to be active in the EDL (attending and speaking at events) for more than four years before ceasing to affiliate with any particular group but taking part in events across the “extreme-right” milieu including organizing his own actions.

Dan’s grievance is primarily political and relates to the perceived failure of the government to challenge Islam, which he considers an ideology, rather than a faith, and as responsible for “brainwashing” Muslims into Islamist extremism. However, his personal experience of growing up in a rapidly changing inner city also shapes a political grievance around what he refers to as “uncontrolled immigration” and which he blames for contemporary social problems such as crime, unemployment and the crisis in the National Health Service. In his late teens, Dan had suffered a near fatal stabbing and a close friend had been shot and killed. These traumatic experiences underpin a deep insecurity related to what he sees as a decline of order and community, which runs through his political grievances around the “influx of difference” and societal crisis of identity, which were found across the milieus in the cross-national study (see ):

[…] the thing with these, to me with immigration now is they’re letting everyone in. I could be living next to… I’ve got Romanians next door to me and Syrians further down. Now them Syrians, I don’t know who they are like, they could be rapists, could be anyone. I don’t like that. I’m very uncomfortable with that.

A sense of collective ontological insecurity is evident also in Dan’s repeated reference to his fear of imminent civil war.

Political grievance becomes personal for Dan also in relation to what he experiences as political exclusion or “silencing”. He characterizes his home city as “hard core left-wing” and complains of having been physically attacked in the street by Antifa activists and that the city’s mayor is “trying to ban all right-wing groups from ever protesting here”. He reported having been unfairly dismissed from employment five times due to his political views and feeling he had “constantly got police on my back”. On one occasion, he was stopped as he left the house to travel to a demonstration, had his speech confiscated and was released only after it was too late to make the event; this felt like being “silenced” in a literal way. Dan also expresses a strong sense of injustice at what he refers to as media, police and state institutions “classing everyone an extremist”, including him, regardless of where they are positioned within the right-wing spectrum. Like Paul, he dissociates himself from “extremism”, references National Action as “real” extremists and denounces Jack RenshawFootnote52 as “planning terrorist acts” and thus as indefensible.

In contrast to Paul, however, the “red lines” that guide Dan’s pathway through the milieu include ideas as well as actions. He strongly rejects antisemitism, expressing incredulity at Holocaust deniers: “[…] I don’t get them. How can you deny that really?” He had visited the Anne Frank Museum in Amsterdam and, at the time of study was planning to visit Auschwitz, as he put it, in order to “see it for myself”.Footnote53 This witnessing of history is important to Dan in his attempt to counter what he calls “a lot of anti-Jewish conspiracies out there”. He also rejects racism and white supremacism and recounts his decision not to attend a demonstration by a particular movement (the one Lee co-founded, see below) because he felt they were “a bit white pride” and having resisted attempts by “local neo-Nazis” to recruit him. Thus, while both Paul and Dan would constitute “sympathizers” (who believe in the cause but not that it justifies violence) on McCauley and Moskalenko’s “opinion” pyramid,Footnote54 Dan’s journey appears propelled by different motivations and dispositions. He is not engaged in a struggle for the “survival” of “my race”, but driven by his desire “to make a difference […] Even if people don’t agree with me, you know, what I feel is right, I want to do something.” He is not closed to having his views challenged and thrives on disagreement; talking about street protests, he says, “I love all that where you shout, and both sides are shouting at each other. Because that is democracy.” He also displays an openness to others, which he himself associates with what he calls “life experience” that he gained growing up, especially from having traveled abroad (including to majority Muslim countries) with his grandparents. This openness is reflected in his initiative to engage in dialogue with an Imam at the mosque in his local area and his expression of the desire “to actually sit opposite a radical Muslim or someone with thoughts of being radical and have a talk with them, and just find out why, why it is he feels that way”.

In fact Dan went on to participate in a series of “mediated dialogues” between a small number of respondents from his own milieu and those from the parallel study of an “Islamist” milieu.Footnote55 At the first event, an initial clash of views – over the relationship between Islam and ISIS – with one of the Muslim participants, developed over the course of the day into a recognition of self in other between the two. As Dan put it, “he was just like me. […] he was Muslim, followed the religion and that, but everything about him was me.” This was tested at the end of the day when each participant was given a few minutes to say something about themselves that they wanted to express and this young Muslim participant chose to recite from the Qur’an. Given his feelings about the Qur’an, Dan expected to feel anger and, he said, his heart had been thumping throughout. However, reflecting on this moment on the way home from the event, Dan admits he was moved by what he calls “a peaceful sound”. This stays with him; a powerful moment of affect that, this time, shifts him away rather than toward extremism.

Dan’s trajectory of partial radicalization appears to have been shaped significantly by situational and affective factors, evident, not least, in his initial engagement with the milieu. However, despite his intense and sustained activism, he has not radicalized further either attitudinally or behaviorally. He remains committed to nonviolence and, whilst not immune to the adrenaline of moments where fighting kicks off at events he attends, he chooses to stand and observe rather than join in: as he puts it, “I don’t want to be arrested for something stupid”. Dispositions of openness to challenge, and to dialogue with others, moreover, suggest his capacity for resilience to further radicalization that could be strengthened by externally generated opportunities to engage in prosocial activities.Footnote56 At the same time, he has not disengaged from the milieu, despite the disintegration of the EDL through which he became active, and a significant change of personal circumstances (birth of his first child) and he remains receptive to external events; during the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, he engaged in anti-lockdown and anti-5G activism.

Looking for “That Family”: Personal Grievance, Search for Meaning and Ideological Ambivalence in Alice’s Trajectory

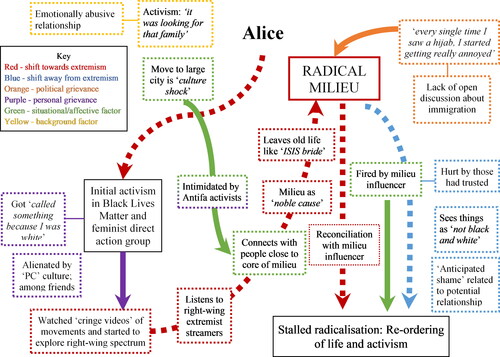

In contrast to the relative “continuity” characterizing the trajectories of Paul and Dan, Alice’s journey might be seen as closer to “conversion”.Footnote57 Affective and situational factors feature strongly but shape a journey through the milieu characterized by numerous twists and turns, rapid accelerations and sudden halts (see ).

Alice was in her late twenties at the time of interview – a graduate with a secure socio-economic background and supportive family. In contrast to Paul and Dan, Alice’s trajectory is shaped by predominantly personal rather than political grievance. She recounts her move into activism as the search for a sense of purpose and “family” following an extended period of unhappiness in what she describes as an “emotionally abusive” relationship. In this context, activism gave meaning to her life:

I think the activism kind of did give me a kind of purpose, a meaning. ‘Cause I’d given up on myself. I remember very specifically thinking, “I don’t care what happens to me anymore. Like, I would rather be dead. But if I’m gonna be alive a bit longer, I guess I should probably try and help other people.” […] So, yeah, so that’s kind of the state I was in when I kind of found politics. And it was definitely, like, with activism, it was looking for that family.

Her concerns about “black rights and institutional racism” led her initially to activism in the Black Lives Matter movement but she left because “everyone was bickering with each other, and I got called something because I was white and that pissed me off”. A similarly negative experience with a feminist direct action group – where she felt her own experience of emotional abuse was not recognized – led her to internet sources critical of these movements and to see herself as “stuck in a left-wing, social justice warrior-type bubble”. Listening to podcasts especially by conspiracy theorist Alex Jones and watching Donald Trump videos, personal grievances started to take on political dimensions. When she had first moved to the city, having grown up in an affluent and largely white town, she had felt it was “different” and “a bit intimidating”, but now:

[…] every single time I saw a hijab, I started getting really annoyed. And every time I saw any semblance of anything Muslim anywhere, I started to think, “Oh, fucking hell, they’re coming. You know, they’re here.”

Although Alice remains skeptical about alt-right theories of “a plan” to outbreed white people, she does feel there needs to be open discussion about the long-term implications of immigration because, she says, “if the population is going to change to such an extent that we’re no longer a majority white … country … well I don’t know if I want that, to be honest.”

The ideological dimension of Alice’s journey, however, remains relatively undeveloped (see ). She narrates her movement into the heart of the “extreme-right” milieu, rather, as strongly situationally and emotionally directed. As she starts to see her old “social justice” crowd through an alt-right lens, she feels increasingly alienated by what she calls a “kind of PC thing” among her friends and, at an “antifa protest” close to her place of work, she is directly threatened. She then connects, by direct messaging, with two people who lead her rapidly into the inner circle around a prominent “extreme-right” milieu figure.Footnote58 When she is invited to join them, she feels she has found the “noble cause” she was looking for. Comparing her next step to that of an “ISIS bride” (Field diary, 05.06.2019), she makes the decision to “pack up and leave” her old life and move into a house with others working for the movement.

[…] to me, it was like, it was like in Mulan when she cuts her hair off, you know. It was like, “You’ll thank me later.” And, like, so you cut your hair off and you get on your horse and you ride off, and then you’re like, “Oh, I’ll come back and I’ll be a hero; they’ll all be thanking me.” You just think you’re on this, like, noble quest, and, like, they don’t understand, but one day they’ll understand. […] I literally thought, like, together we were gonna sort of save Britain or something […]

Thus alongside the feeling of alienation from her old crowd, Alice experiences the thrill (akin to the “buzz” described by Lee, below) of the milieu on this part of her journey. Being close to a key influencer feels “like being in the cool club” while activism is “like literally being pirates or something, or like being in a rock band. You know, there’s so many mad but brilliant moments – moments that are, like, will stay with you forever.”

Alice’s journey stalls as rapidly and unexpectedly as it starts. After a dispute with the milieu influencer, Alice was sacked. The events surrounding this were widely discussed in the milieu and she suffered a torrent of online abuse including accusations that she was an infiltrator. The experience was emotionally overwhelming; she was shunned by others in the milieu and deeply hurt when it transpired that those to whom she had felt close had only ever partially accepted her. At first, she saw this as a personal betrayal but later as a wider problem in the movement, in which there was little space for someone with her gender and class background: “in a way, I can’t be taken seriously, because yeah, I am a girl. I’m a middle-class, posh…” A later, partial, reconciliation with the milieu influencer – in which Alice demonstrates her continued loyalty – brings her back into the milieu but at considerably greater distance.

Alice narrates this more distanced relationship as reflecting her desire to focus on new projects and to keep a healthy separation between her political, work and personal lives. However, it is clearly also shaped by a disillusionment with those she had trusted. As Bjørgo argues, high expectations of the emotional dimensions of the milieu carry potential disillusionment when political goals, friendship or a sense of belonging and purpose are left unfulfilled or betrayed.Footnote59 Alice’s resilience to being drawn fully back into the milieu is also the result of the genuine ambivalence she has toward the ideological narratives circulating there. In addition to her doubts about a conspiratorial plan for population replacement, she feels uncomfortable with the language of race she sometimes encounters in the milieu: “the idea of having […] people that genuinely look at a black person and think in terms of ‘alt-right kind of, you know, ‘What are they doing in my country?’ type stuff is, it’s kind of unnatural at this point”. Alice’s previous activism means she is able to relate to both “far right, and the far left” and has a capacity to see things as “not black and white”, as another respondent in the milieu says of her. Alongside tolerance of uncertainty and open-mindedness, Alice is highly reflective and articulates an anticipatory shame, which has also been linked to resilience to radicalization.Footnote60 Specifically, she imagines how she might appear to those outside the milieu if they were to see her previous participation in live-streamed shows in which she had been effectively “nodding along” to antisemitic remarks.

Alice’s reference to herself as akin to an “ISIS bride” captures her accelerated movement into the very core of the milieu and a conscious separation from her former life that might be understood as behavioral radicalization. However, she does not support or engage in violence for the cause and is ideologically ambivalent. Political grievance is thus weakly articulated and her trajectory is heavily shaped by affective and situational factors. While her journey might be characterized as currently “stalled”, the future is unpredictable due to the potential for situational and/or affective factors to re-direct it. However, her disposition toward seeing things from both sides, concern with how things look from the outside and desire to rebalance her life in terms of political activism, work and personal life suggest she will remain at least resistant to further radicalization if not move out of the milieu altogether.

“I Was There for the Scrap”: Violence, Attitudinal Radicalization and Disengagement in Lee’s Trajectory

Lee was in his late thirties at the time of interview and had been recently released from a third prison sentence for violent disorder related to political activism. He differs from the other research participants discussed here in that, on release from prison, he had committed to disengaging from the “extreme-right” milieu and narrated his journey as one of (de)radicalization. As he puts it, “I radicalised myself, and now I’ve gone through it, and now I’ve deradicalised myself”. Tracing Lee’s journey, however, reveals it to be far from so straightforward. The relative absence of both political and personal grievance in driving radicalization and his engagement in violence (behavioral radicalization) prior to significant cognitive radicalization suggests Lee’s journey is strongly shaped by situational and affective factors, especially the search to recapture the “buzz” - excitement, community and respect - associated with fighting in his teenage years.

Lee grew up on a notorious housing estate in a town in the north of England where he lived mainly with his grandparents due to his mother’s drug use issues. He failed to finish college – a vocational course he didn’t enjoy – after skipping classes to “get pissed” and ended up in prison at the age of twenty following involvement in a violent attack, which, Lee says, he cannot even remember due to the drink and drugs consumed. It was three years after release from prison that he became politically active. Lee’s early life circumstances are much more difficult than the other three respondents discussed here but they do not appear in his narration as a source of personal grievance. This is indicative of the indirect relationship between objective socio-economic conditions and radicalizationFootnote61 as well as the reluctance of extreme-right milieu actors to invoke inequality – viewed as rooted in naturalized difference – in recounting their journeys.Footnote62 It also reflects the fact that these circumstances do not lead to grievances, which then lead to engagement in violence; in Lee’s journey, violence is the starting rather than endpoint.Footnote63

Like the majority of young people who face difficult social structural issues and life crises, Lee first seeks to “resolve” these problems not by joining violent extremist groups but through mechanisms of everyday coping including alcohol and drug use and violence.Footnote64 However, this violence was not random but embedded in a local environment in which racialized violence was so endemic that it was factored into the organization of the school day:

We’d fight with them at dinnertime with the lads and then there were, their uncles and dads would come up after school. … They’d turn up with cricket bats and everything, so … So it got to the point where … about twenty minutes before school had finished, they’d come and collect the lads that they knew were involved in it. And they’d have the [police] vans down the middle of the yard and they’d say, “Right, you go down that way, and you go down that path. And you Muslim lads, go that way, your dads and that are waiting there.”

Lee recalls these in-school clashes as a “buzz” that were turned into a weekend leisure practice: “we used to make a point of going into their area, “cause we, we used to get pissed and that and go looking for them and go, go looking for a scrap and that.”

It was only in his early twenties that Lee became politically active. After encountering an EDL activist on a night out, he attended a demonstration and subsequently became involved in setting up a local division of the movement. Establishing the local movement secured a way to generate situations in which he could get the “buzz that I used to get when I were a kid fighting and that”. However, his use of political activism as a point of access to situations of potential violence – as well as a dispute over a video of Lee and others “doing Nazi salutes” – led to conflict with the EDL leadership, which was trying to rid the movement of its association with drunken, racist thugs. Lee’s subsequent expulsion from the EDL marks an important point in his radicalization trajectory as he starts to engage with more extreme groups and eventually sets up his own movementFootnote65 focusing on direct action, primarily picking fights with what he calls “militant left” groups and those supporting Irish republicanism. Despite a series of prison sentences resulting from violent clashes with oppositional groups, Lee recalls “we buzzed off it. We loved it” and describes this period as “some of the best time in me life.” Thus, Lee’s journey through the milieu appears to be driven less by political or personal grievance than his search for “a scrap”; a deeply imprinted, interaction ritual chainFootnote66 underpinning his participation in collective violence from early teenage years. By forming his own movement, he was able to ensure regular access to the emotional energy and feelings of solidarity he experienced from fighting.

The split from the EDL marks a period of ideological radicalization also. Lee starts to maintain contact with neo-Nazi groups such as (subsequently proscribed) National Action and, only by chance, misses the meeting at which Jack Renshaw revealed his plans to murder the Labour Party MP Rosie Cooper, as a result of which Renshaw was arrested, convicted under the Terrorism Act and sentenced to life imprisonment. Renshaw’s plot was exposed by an attendee at that meeting, who felt compelled to blow the whistle after hearing what was planned. When I asked Lee what his own reaction would have been had he been there, however, he replied, “I probably would have let them do it, with mind-set that I were in then, yeah. I wouldn’t have grassed them up or out. It’s like honour, innit?” It is important to recognize here that although Lee describes himself as not “into political side of it”, his violence is intrinsically connected to his political views. The teenage fighting in which he was involved was racialized and he grew up in an environment with a strong BNP presence; as a teenager, he had leafleted for the party on behalf of a relative of a friend. Even at the time of interview (when already disengaged from the milieu), he says that demographic change in his area makes him feel “like your identity’s being written out, isn’t it and your history’s being written out”. Moreover, he himself recognizes that as his new movement brought together individuals from more extreme parts of the milieu, so their mission statement tried to “accommodate” their “anti-immigrant”, “anti-Jew” and sectarian positions. His growing proximity to National Action, who he describes as “very, very antisemitic”, was critical in this radicalization process and his response that he would have “let them do it”, when asked about Renshaw’s plan, appears to signal a move to the apex of the “opinion pyramid”;Footnote67 from justifying violence to feeling a moral obligation to take up violence for the cause.

Situational and affective factors are crucial not only to Lee’s journey into the radical milieu but also his disengagement from it (see ). Like Alice, his strong emotional investment in the movement makes him open to disappointment. This forms when those in the movement failed to help his girlfriend and her children through financial difficulties whilst he was in prison, even though he had set up a hardship fund for those convicted in relation to the same incident. At the time of interview, he had six of his own children as well as a caring role for his partner’s children and feeling let down by the failure to support his girlfriend reinforced a growing sense that he had wrongly prioritized activism over family. The decisive moment came when social workers warned him that if he returned to activism after release, he risked losing access to his own and his partner’s children and he remembers, “straight away that gripped me, the switch went, and I thought, ‘That’s it. I can’t do it anymore. I can’t, I can’t run the risk of my kids and [names girlfriend]’s kids being taken away.’”

Lee appears to ascend further up both the “opinion” and “action” pyramids of radicalization than the other respondents discussed here; he engages with, although never joins, National Action and is convicted repeatedly for violence related to activism. However, tracing his trajectory reveals it is shaped strongly by neither political nor personal grievance but propelled by a longing for the buzz of teenage, racialized fighting, the community and respect that came with it and the repayment of loyalty that it required. Thus, when Lee imagines how he would have responded to Renshaw’s terrorist plot, he interprets the situation not as a question of ideological commitment (whether he would support such an act in the interests of the cause) but of loyalty (whether or not he would “grass them up”). His response is governed by his personal moral compass, shaped by chains of previous interactions and situations and ritualized in an etiquette of honor and loyalty.Footnote68 Moreover, while it is disillusionment with his own movement, as well as reprioritization of family in his life, which brings him to the decision to disengage from the milieu, it is re-finding this buzz in community activism that generates the resilience to do so.

Conclusion

This article brings fresh insight to our understanding of radicalization by employing three key concepts in the literature on radicalization and terrorism – “trajectories”, “milieus” and “non-radicalization” – to understand why and how most journeys through such milieus do not lead to violent extremism. Combining these three concepts – which posit radicalization as a dynamic and open-ended process – in a single theoretical framework allows us to move beyond the endpoint determinism of much research on radicalization and inform counter-extremism interventions based on evidence of what stalls or halts radicalization journeys. The empirical study drawn on employed an ethnographic approach, engaging with those still on their journeys through radical(izing) milieus, to explore radicalization not only as process but in process. While only a handful of the studied trajectories could be outlined in this article, their characterization in relation to three key dimensions – attitudinal/behavioral extremism, political/personal grievance, and strength of emotional/affective and situational drivers (see ) – suggest a number of implications for future research and counter-extremism intervention.

First, the study provides further evidence that radicalization pathways are non-linear and lead to a range of outcomes amongst which violent extremism is rare. It demonstrates further that we need not only to recognize non-radicalization as an outcome, but that there are multiple non-radicalization trajectories. These are illustrated through comparisons between trajectories of partial radicalization (Paul and Dan) and stalled/halted radicalization (Alice and Lee). While the degree of attitudinal extremism varies between Paul and Dan, their trajectories show a consistent rejection of the use of violence alongside continued active engagement in the milieu notwithstanding changes in movement affiliation and personal circumstances that lead others to disengage. In contrast Alice’s and Lee’s trajectories are characterized by more frequent and significant twists and turns and, at the point of research, had stalled or stopped. While their pathways are also very different (not least in the engagement in violence by Lee but not Alice), in comparison to Paul and Dan, they are both characterized by greater ideological ambivalence and more subject to situational and affective factors.

The second conclusion is thus to confirm the importance of the relational and emotional dimension of radical(izing) milieus. This is most apparent in the journeys of Lee and Alice for whom political activism satisfied a search for “family” and generated a collective energy (“buzz”) and collective purpose (“noble cause”) but for whom a sense of betrayal was also a key factor in drawing back or disengaging from the milieu. Dan, who is wary of being caught up in the emotional energy of collective action (for fear of being “arrested for something stupid”) nonetheless manages his feelings of anxiety, threat and displacement through the collective expression of anger over perceived injustice. Even Paul, who is dismissive of the kind of street-based protest which generates positive affect for Dan, is emotionally committed to the “positive, outward looking community group” he believes he is building through his activism.

Thirdly, the study confirms McCauley and Moskalenko’s suggestion that there is a relatively “weak relation between attitude and behavior” and that radicalization develops along separate pathways of radicalization of “opinion” on the one hand and “action” on the other.Footnote69 At the same time, the findings suggest that the “two pyramids model” remains over-determined by violence and thus unable to capture significant variation in degree of cognitive radicalization between milieu actors. Moreover, it reveals a stark gap between what constitutes “radicalized” in academic models and in public discourse; none of the actors considered here, theoretically, reach the apex of either pyramid whilst, in practice, two have been prosecuted in relation to their activism, three have been the object of police attention and all four have been exposed as “extremists” by anti-extremism organizations.

Fourthly, the study finds the distinction between political and personal grievanceFootnote70 in driving radicalization to be helpful and suggests the potential for further study of the relative weight, and order, of political and personal grievance in (non)radicalization trajectories. Moreover, while generalizations to the broader population of “extreme-right” activists cannot be made on the basis of this qualitative study, it found an apparent reluctance to articulate personal grievances by “extreme-right” actors, except where they relate to injustice experienced at the hands of “the system” (political, judicial etc.). It was also found that personal grievance was articulated more readily by those who were attitudinally and behaviorally least radicalized. Given a similar finding in relation to online activism by violent and nonviolent right-wing extremists, this might also warrant future study.Footnote71

Fifthly, in understanding what explains resistance to violent extremism among individuals exposed to radical ideologies, the study confirms a number of Cragin’s findings.Footnote72 In particular, perceived (in)efficacy of violence and moral (non)acceptability of violent action were found to be important “red lines” in the trajectories of partial radicalization while the costs of participation were crucial to decisions to disengage or pull back from the milieu. However, the findings suggest that resilience to violent extremism may be built through engagement in the radical milieu also. This may be a consequence of actions by milieu leaders or influencers in guiding, especially younger, actors, away from violence. It may also result from direct encounters with more extreme groups and individuals, which help individuals draw their own “red lines” in relation to “real extremists”.

Finally, the findings confirm that journeys through radical milieus are profoundly individual. Whether encounters in or through the milieu lead to a shift toward or away from extremism is shaped by background factors (ontological and material (in)securities), the degree to which political grievance has become personalized grievance, opportunities to resolve grievances in other ways, and personal dispositions (such as open-mindedness). However, resilience to violent extremism is not the outcome of a binary struggle between individual risk versus protective factors but a product of the interdependence between individuals, social systems and institutions.Footnote73 The profound affect experienced by Dan from participation in “mediated dialogue” and the commitment of Lee to harnessing the “buzz” he derives from community activism to “deradicalize” himself, illustrate the important role of external agencies, individuals and opportunity structures in building resilience through engagement in prosocial activities.Footnote74 This study suggests such interventions are important not only to prevent but also to prevent further radicalization.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to all the respondents in this study for the trust they showed in sharing their journeys with me. Thanks are extended also to Viggo Vestel for his collaboration on the European cross-case data analysis referred to in this article and to Rosie Mutton for work on early versions of and .

Disclosure Statement

The author has no potential conflict of interest to report.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Randy Borum, “Radicalization into Violent Extremism I: A Review of Social Science Theories,” Journal of Strategic Security 4, no. 4 (2011): 9; John Horgan, “Discussion Point: The End of Radicalization?” (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2012), http://www.start.umd.edu/news/discussion-pointend-Radicalization; Peter Neumann, “The Trouble with Radicalization,” International Affairs 89, no. 4 (2013): 879.

2 Mark Dechesne, “Non-Radicalisation under a Magnifying Glass: A Cross-European ‘Milieu Perspective’ on Resistance to Islamist Radical Messaging,” in Resisting Radicalisation? Understanding Young People’s Journeys through Radicalising Milieus, ed. Hilary Pilkington (New York: Berghahn, in press).

3 Hilary Pilkington, “Radicalisation Research Should Focus on Everyday Lives,” Research Europe 9, no. 7 (2017), https://www.researchresearch.com/news/article/?articleId=1366511; Bart Schuurman, “Non-Involvement in Terrorist Violence,” Perspectives on Terrorism 14, no. 6 (2020): 16.

4 Gary Alan Fine and Ugo Corte, “Dark Fun: The Cruelties of Hedonic Communities,” Sociological Forum 37, no. 1 (2021): 78.

5 Inverted commas are used when referring to the milieu studied in this article as “extreme-right”. This reflects research participants’ dissociation of self from this descriptor. For a fuller discussion, see Hilary Pilkington, “Why Should We Care What Extremists Think? The Contribution of Emic Perspectives to Understanding the ‘Right-wing Extremist’ Mind-set,” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 51, no. 3 (2022): 318–346.

6 Lasse Lindekilde, Stefan Malthaner, and Francis O’Connor, “Peripheral and Embedded: Relational Patterns of Lone-actor Terrorist Radicalization,” Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict 12, no. 1 (2019): 23.

7 Stefan Malthaner and Peter Waldmann, “The Radical Milieu: Conceptualizing the Supportive Social Environment of Terrorist Groups,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 37, no. 12: 979–98.

8 Stefan Malthaner, “Radicalization: The Evolution of an Analytical Paradigm,” European Journal of Sociology 58, no. 3 (2017): 389.

9 Hilary Pilkington and Viggo Vestel, “Situating Trajectories of ‘Extreme-Right’ (Non)Radicalisation: The Role of the Radical Milieu,” in ed. Pilkington, Resisting Radicalisation?

10 Malthaner and Waldmann, “The Radical Milieu”: 994.

11 Ibid.; Hilary Pilkington, “Situational and Interactional Dynamics in Trajectories of (Non)Radicalisation: A Micro-Level Analysis of Violence in an ‘Extreme-Right’ Milieu,” in ed. Pilkington, Resisting Radicalisation?

12 Malthaner and Waldmann, “The Radical Milieu”: 983.

13 Lindekilde, Malthaner, and O’Connor, “Peripheral and Embedded”: 23–24.

14 John Horgan, “From Profiles to Pathways and Roots to Routes: Perspectives from

Psychology and Radicalization into Terrorism,” The Annals of the Academy of the Political and Social Sciences 618 (2008): 80–94.

15 Ibid.; Stijn Sieckelinck, Elga Sikkens, Marion van San, Sita Kotnis, and Micha De Winter, “Transitional Journeys Into and Out of Extremism. A Biographical Approach,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 42, no. 7 (2019): 662–682.

16 See also: Annette Linden and Bert Klandermans, “Revolutionaries, Wanderers, Converts, and Compliants: Life Histories of Extreme Right Activists,” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 36, no. 2 (2007): 184–201; Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko, “Mechanisms of Political Radicalization: Pathways Toward Terrorism,” Terrorism and Political Violence 20, no. 3 (2008): 429.

17 Randy Borum, “Radicalization into Violent Extremism II: A Review of Conceptual Models and Empirical Research,” Journal of Strategic Security 4, no. 4 (2011): 57.

18 Fathali M. Moghaddam, ‘The Staircase to Terrorism: A Psychological Exploration’, American Psychologist 60, no. 2 (2005): 161–169; Quintan Wiktorowicz, Radical Islam Rising: Muslim extremism in the West (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005).

19 Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko, “Understanding Political Radicalization: The Two-Pyramids Model,” American Psychologist 72, no. 3 (2017): 211; Borum, “Radicalization into Violent Extremism I”: 30.

20 Lindekilde, Malthaner, and O’Connor, “Peripheral and Embedded”: 23–24.

21 Kim Cragin, “Resisting Violent Extremism: A Conceptual Model for Non-Radicalization,” Terrorism and Political Violence, 26 (2014): 337–353.

22 Ibid.

23 Kim Cragin, Melissa A. Bradley, Eric Robinson and Paul S. Steinberg, “What Factors Cause Youth to Reject Violent Extremism? Results of an Exploratory Analysis in the West Bank,” (Rand Corporation, 2015), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1118.html.

24 Jeff Goodwin, James M. Jasper, and Francesca Polletta, “Why emotions matter,” in Passionate Politics: Emotions and Social Movements, ed. Jeff Goodwin, James M. Jasper and Francesca Polletta (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 20; James M. Jasper, “The Emotions of Protest: Affective and Reactive Emotions in and around Social Movements,” Sociological Forum 13, no. 3 (1998): 417.

25 Manuel Castells, Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012), 2–3, 14–15; Randall Collins, “Social Movements and the Focus of Emotional Attention,’ in Passionate Politics ed. Goodwin, Jasper, and Polletta (2001), 27–29; Hilary Pilkington, Loud and Proud: Passion and Politics in the English Defence League (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016), 180–186, 197–199.

26 See, inter alia: Kris Christmann, Preventing Religious Radicalisation and Violent Extremism: A Systematic Review of the Research Evidence, (Youth Justice Board for England and Wales, 2012), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/396030/preventing-violent-extremism-systematic-review.pdf: 27; Malthaner, “Radicalization: The Evolution of an Analytical Paradigm,” 376–7; Linden and Klandermans, “Revolutionaries, Wanderers, Converts, and Compliants,” 185.

27 “Resilience” describes the capacity to absorb the impact of, and recover from, shock, trauma or disturbance. For a discussion of the application of the concept to the CVE field, see: Kieran Hardy, “Resilience in UK Counterterrorism,” Theoretical Criminology 19, no. 1 (2015): 77–94; Michele Grossman, “Resilience to Violent Extremism and Terrorism: A Multisystemic Analysis,” in Multisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change ed. Michael Ungar (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 293–317; William Stephens and Stijn Sieckelinck, “Resiliences to Radicalization: Four Key Perspectives,” International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice 66 (2021): 1–14, published online first, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2021.100486.

28 Stijn Sieckelinck and Amy-Jane Gielen, “Protective and Promotive Factors Building Resilience against Violent Radicalisation,” RAN Issue Paper (Amsterdam: RAN Centre of Excellence, 2017), https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network/ran-papers/docs/ran_paper_protective_factors_042018_en.pdf: 4; Grossman, “Resilience to Violent Extremism and Terrorism,” 298.

29 The study was granted ethical approval by the University of Manchester Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 2017-1737-3255) on 14 June 2017.

30 For a brief outline of each of these movements, see Hilary Pilkington, Understanding “Right-wing Extremism”: in Theory and Practice (DARE Research, 2020), https://www.dare-h2020.org/uploads/1/2/1/7/12176018/d7.1_uk_final.pdf, 177–179.

31 Ibid.: 180–182.

32 Further details of the ethnographic approach taken and issues of positionality can be found in Pilkington, “Why Should We Care What Extremists Think?”: 327–328.

33 Lorne L. Dawson, “Taking Terrorist Accounts of their Motivations Seriously: An Exploration of the Hermeneutics of Suspicion,” Perspectives on Terrorism 13, no. 5 (2019): 74–89; James Khalil, “A Guide to Interviewing Terrorists and Violent Extremists,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 42, no. 4 (2019): 429–443.

34 Dawson, “Taking Terrorist Accounts of their Motivations Seriously”, 84.

35 For the findings of this thematic analysis of the wider data set, see Pilkington and Vestel, “Situating Trajectories of ‘Extreme-Right’ (Non)Radicalisation”.

36 McCauley and Moskalenko, “Mechanisms of Political Radicalization”, 417–419.

37 These are the most salient themes from the cross-case analysis. For a more detailed discussion, see Pilkington and Vestel, “Situating Trajectories of ‘Extreme-Right’ (Non)Radicalisation”.

38 See also John M. Berger, Extremism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018), 127–131.

39 McCauley and Moskalenko, “Mechanisms of Political Radicalization”, 419.

40 Axel Honneth, The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1995), 163–4.

41 As identified by Linden and Klandermans, “Revolutionaries, Wanderers, Converts, and Compliants”.

42 Pilkington, “Loud and Proud”: 76.

43 McCauley and Moskalenko, “Mechanisms of Political Radicalization”, 425.

44 While the whole data set from the UK study informs this analysis, the specific data related to these four respondents includes a total of ten interviews and 25 field diary entries.

45 Paul had been prosecuted for intent to cause racial hatred but acquitted. Lee had served prison sentences for violent disorder relating to his activism but had no terrorism-related convictions.

46 Specific movements or parties that respondents have belonged to, founded or are currently active in, are not named if there is any risk that by so doing, respondents might be identified.

47 The “opinion pyramid” starts, at the base, with those who pursue no political cause (neutral) and climbs through those who believe in the cause but do not justify violence (sympathizers), those who justify violence in defense of the cause (justifiers) to the apex where people feel a personal moral obligation to take up violence in defense of the cause. At the base of the “action pyramid” are those not active in a political group or cause (inert), followed by those who are engaged in legal political action for the cause (activists), those who carry out illegal action for the cause (radicals) and, at the apex, those whose illegal action targets civilians (terrorists) (McCauley and Moskalenko, “Understanding Political Radicalization”).

48 National Action was formed by Alex Davies and Ben Raymond in 2013 as a nationalist youth movement seeking to establish Britain as a ‘white homeland’. In 2016, it became the first extreme-right organization in the UK to be proscribed as a terrorist organization.

49 Berger, Extremism, 44.

50 This source (2018) is not referenced to protect anonymity of the research participant.

51 See also Pilkington, “Loud and Proud”: 181–182.

52 Renshaw was a National Action activist convicted in 2018 of plotting to murder Labour MP Rosie Cooper and making a threat to kill a police officer.