Abstract

Since the early 1970s, the United Kingdom (U.K.) has experienced political violence undertaken by militant animal rights actors. This violence has included the use of car bombs and incendiary devices, which are more akin to the tactics of a terrorist campaign. Similar acts in the United States have been described as “eco-terrorism” yet this label has not gained traction in the U.K. This article is concerned with the labeling of militant animal rights actions in the U.K. and explores the labels that have been applied by the print media, notably The Guardian to the actions of those animal rights actors who have utilized or espoused illegal and violent tactics in the pursuit of their cause. Moreover, the article takes a more in-depth look at the labeling of the group Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (SHAC) in its campaign against Huntingdon Life Sciences and its business partners. How actions are labeled can have repercussions in shaping the public debate and policy implications.

The vast majority of animal rights actors worldwide engage in legal and peaceful tactics such as marches, protests, letter writing, email or online petitions as well as public information stalls.Footnote1 However, a very small number of individuals and groups have engaged in illegal actions in order to pursue their agenda—this is referred to in this article as militant animal rights actions.Footnote2 Moreover, some militant animal rights actors have used political violence including arson attacks, car bombs and incendiary devices. Such acts have been labeled as “eco-terrorism” in the United States (U.S.) where the actions of militant animal rights actors and radical environmentalists are taken together under this umbrella term. Hirsch-Hoefler and Mudde define eco-terrorism as a “strategy that employs the threat or use of force or violence to instill fear in (a subset of) the population with the ultimate aim of […] the ending of environmental destruction and animal rights abuse” [emphasis in original].Footnote3 Moreover, Sumner and Weidman found in their research that there has been a growing acceptance of the term in the U.S. amongst journalists and their sources and within government.Footnote4 Similarly, Wagner found that newspapers have increasingly framed ecotage, that is to say those illegal acts such as vandalism, arson and threats undertaken by activists to protect nature (including animals), whilst not posing a threat of harm to humans, as terrorism.Footnote5 Indeed, the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) was added to the domestic terrorism list by the FBI in 1987 following an arson attack on the University of California, Davis, Animal Diagnostics Laboratory, which destroyed a building and 20 vehicles, causing $5.1 million in damage.Footnote6 In testimony before the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, Senator James N. Inhofe stated:

The Department of Justice and the Department of Homeland Security agree that eco-terrorism is a severe problem, naming the serious domestic terrorist threat in the United States today as the Earth Liberation Front (ELF) and the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) which, by all accounts, is a converging movement with similar ideologies in common personnel.Footnote7

This is 1 of today’s most serious domestic threats, coming from the special interest extremist movements that we have heard about this morning: ALF, ELF, as well as another outfit called Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty, commonly known as SHAC…these individuals are most certainly domestic terrorists, in the truest sense, because their agenda clearly advocates the unlawful or threatened use of force or violence to intimidate or coerce our society, our Government, for the benefit of their own ideological or political reasons.Footnote8

Before examining the labels that have been applied to such actions in the U.K., a brief overview of the evolution of militant animal rights activity is provided. Following this, the methodology employed in the research is discussed before focusing on the labels applied to militant animal rights actions with a particular focus on SHAC.

Evolution of Militant Animal Rights Activity

Militant animal rights actions can be traced back to the early 1970s with the emergence of a group calling itself the Band of Mercy after a nineteenth century direct action group of the same name comprised of young supporters of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals who damaged guns belonging to hunters.Footnote13 The twentieth century group was comprised of two members of the Hunt Saboteurs Association,Footnote14 Ronnie Lee and Cliff Goodman and four other animal rights actors who had come to believe that action should also be taken to save animals in factory farms and laboratories and not just on behalf of animals hunted for recreation.Footnote15 The Band initially targeted hunts by rendering their vehicles unusable during the cub hunting seasonFootnote16 before embarking upon a campaign of property damage including arson and the destruction of equipment at various laboratories involved in animal experimentation and the arson of two boats that were to be used in a seal cull. In a statement to the press following their arson attack on a pharmaceutical building under construction, the group stated “we are a non-violent guerrilla organisation dedicated to the liberation of animals from all forms of cruelty and persecution at the hands of mankind.”Footnote17 This campaign was relatively short-lived as both Lee and Goodman were apprehended by the police. In March 1975, they were convicted of causing more than £50,000 worth of damage and received a three-year custodial sentence.Footnote18 Released early from prison, Lee rebranded the Band of Mercy to the Animal Liberation Front in 1976 with initially 30 members.Footnote19 Reflecting upon his jail time, Lee stated:

I feared this could deter other people and put an end to this form of direct action. But when I came out of prison, I was pleasantly surprised at the number of animal protection campaigners who now wanted to become involved. It was at this point that it was decided to change the name to the Animal Liberation Front (A.L.F.), in order to clearly reflect what we stood for.Footnote20

In the mid-1980s two groups emerged who were willing to use violence against humans, namely the Animal Rights Militia (ARM) and the Hunt Retribution Squad (HRS).Footnote25 The ARM claimed responsibility for sending letter bombs to the leaders of the four main political parties in 1982, six minor bomb attacks on scientists’ homes in 1985 and four car bombs in January of the following year. The group was also responsible for the planting of incendiary devices in shops in Cambridge, Oxford, York, and Harrogate and on the Isle of Wight in 1994. Targets varied and included shops selling animal products such as leather, chemists, a sports shop and a medical charity shops.Footnote26 The group also claimed responsibility for alleged product contaminations including injecting eggs with rat poison and tampering with antiseptic cream.Footnote27 In contrast, the HRS established in 1984, were primarily concerned with attacking “blood sports,” namely hunting and angling. The group had threatened to break the hands of hunt supporters with hammers, chainsaw their vehicles and in 1993 planted incendiary devices at the office of a shooting magazine.Footnote28 A third group willing to harm humans appeared in October 1993, calling itself the Justice Department and initially sent a letter bomb addressed to an individual connected with blood sports, the device exploded at a postal sorting office. A further thirty attacks were claimed by the group in the last three months of 1993, including timed incendiary devices, poster tube, and videocassette bombs. Those targeted included individuals connected with blood sports, companies involved in animal experimentation, and furriers. The group claimed a further one hundred attacks in the 1994, including two serious car bombs, which exploded under vehicles belonging to individuals connected to animal experimentation. The group also extended their targeting to include secondary targets, namely suppliers of a service or goods to a business involved in animal “exploitation” and sent six letter bombs to companies involved in the transportation of livestock.Footnote29

Throughout the noughties, militant animal rights activity has been concerned with supporting specific animal rights campaigns, namely against Darley Oaks Farm in Staffordshire; the University of Oxford and Huntingdon Life Sciences (HLS) based in Cambridgeshire.Footnote30 As Lee notes with respect to the ALF, it “tends more to act as a back up to existing campaigns, often delivering the killer blows to businesses that are already under pressure from other methods of campaigning. Additionally, its actions are more concentrated and thus far more successful.”Footnote31 Thus, the Save the Newchurch Guinea Pigs’ campaign against Darley Oaks Farm (a supplier of guinea pigs for medical research), owned by the Hall family, which lasted some seven years from 1999 to 2006, also involved the ALF and the ARM. The Farm and its employees were subject to arson attacks, death threats, hate mail, hoax bombs, criminal damage (e.g. smashed windows), and a smear campaign alleging pedophilia. The ALF claimed responsibility for the “liberation” of 600 guinea pigs by the ALF and the ARM in 2004, dug up and stole from a graveyard the remains of Christopher Hall’s mother-in-law, Gladys Hammond.Footnote32

The anti-vivisection group SPEAK’s campaign against the construction of a new biomedical sciences building for research animals at the University of Oxford started in 2004. The group engaged in legal protests with demonstrations, leafletting, picketing the building site and letter writing while the ALF has attacked not only the University (e.g. arson attack on Hertford College’s boathouse) but also contractors and suppliers working on the project.Footnote33 Despite stressing that “we’re a legal campaign, we do not encourage people to break the law. There are no links between us and these direct action groups,” Mel Broughton, a co-founder of SPEAK was arrested in 2007 following the discovery of a number of incendiary devices at colleges of the University.Footnote34 He was found guilty in 2009 of conspiracy to commit arson and subsequently sentenced to 10 years imprisonment less time on remand.Footnote35

The campaign against HLS began in 1999 with the formation of Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (SHAC), which sought the company’s closure. During SHAC’s lifespan (1999–2014), a range of tactics were used including public demonstrations in Cambridge and pickets and protests outside the company’s premises and the targeting of anyone involved with, or with business-links to including their customers, suppliers and shareholders.Footnote36 As Ellefsen and Busher note,

despite claims to be embedded within a nonviolent tradition, throughout much of the campaign, conventional and transgressive protest tactics were combined with violent tactics…This included some activists who largely associated with the underground faction of the campaign setting fire to cars in people’s driveways, throwing bricks through the windows of their houses, disseminating malicious rumors and threatening to harm people’s children.Footnote37

Both the ALF and ARM have been involved in the campaign against HLS.Footnote38 Bomb attacks undertaken by Donald Currie on companies with indirect links with HLS were claimed by the ALF – Currie was apprehended and sentenced to 12 years for four charges of arson, one of attempted arson, and two counts of possessing explosives with the intent of carrying out further explosions.Footnote39 The ARM sent warning letters to companies supplying services to HLS threatening physical violence including a nursery and local building companies.Footnote40 However, SHAC founder members, Greg and Natasha Avery, were found guilty in 2009 of conspiracy to blackmail companies with links to HLS and received sentences of nine years, with the prosecution “linking the ostensibly lawful campaign of protest and demonstration by SHAC with the unlawful, criminal campaign of intimidation, badged as ALF.”Footnote41

With the scope of militant animal rights activity outlined, the methodology utilized in this article’s research is discussed.

Methodology

The research examines the labels applied to militant animal rights activity through an analysis of print media articles. The methodology, namely a content analysis, mirrors the approach taken within the extant North American literature on eco-terrorism.Footnote42 According to Berelson content analysis is “[…] a research technique for the objective, systematic and quantitative description of the manifest content of communication.”Footnote43 Two separate content analyses were undertaken, the first utilized the ProQuest Historical Newspapers database for the period beginning January 1972 through to the end of December 1998. This period was chosen to capture data from the formation of the Band of Mercy in 1972 and covers the emergence of animal rights groups such as the ALF and ARM who were willing to undertake militant action, namely illegal actions including the use of violence in the pursuit of their cause. The year 1998 was the last year before SHAC was established. The second content analysis is concerned with one particular group, namely SHAC, who as previously discussed were linked with militant action and whose campaign led the British Government to create and/or amend laws to deal with militant animal rights activity.Footnote44 LexisNexis was utilized and covered the period from the beginning of January 1999 through to the end of December 2020.Footnote45 Although SHAC’s campaign against Huntingdon Life Sciences ended in 2014, a number of SHAC members’ court cases were held after this date. For example, SHAC members Natasha Simpkins and Sven Van Hasselt were sentenced in January 2018 following their campaign against HLS, which saw researchers targeted with incendiary devices, false allegations of pedophilia and packages claimed to have been contaminated with HIV sent to suppliers and customers of HLS.Footnote46 For both analyses, one newspaper, The Guardian was chosen. The rationale for this choice was based on the public’s perception. According to Ofcom, no other British newspaper received more votes than The Guardian with respect to accurateness, quality and trustworthiness.Footnote47

For the first content analysis, the sample of articles to be examined was generated using the search terms “animal rights” and “animal liberation.” These two search terms yielded 1614 articles. Each article was read and duplicate articles, letters to the editors and articles that contained tangential or passing references to animal rights and/or animal liberation were removed leaving a final sample of 347 articles. These were downloaded and codes were derived from the text data. Although the articles were in pdf format they weren’t text but an image and as such were not amenable to being coded in a qualitative data analysis computer software package like NVivo and so were manually coded. In terms of the second content analysis, the search term “Stop Huntington Animal Cruelty” was used and yielded 70 articles.Footnote48 Seven duplicatesFootnote49 and one letter were removed, thus, leaving a sample of 62 articles, which were downloaded and codes derived from the text. For consistency, these articles were also manually coded.

A summative approach involving a deep structure (latent) content analysis was undertaken for both samples to not only identify and quantify the words or labels employed in the text with respect to militant animal rights actors but also to explore the underlying meaning of the words and the context of their usage. As Hsieh and Shannon point out a summative approach can provide researchers with an “insight into how words are actually used.”Footnote50 However, it is important to note that issues around researcher bias and trustworthiness have been raised with respect to qualitative content analysis.Footnote51 To counter researcher bias, a reflective process was employed, whereby coding and the categorizing of the data was returned to and was not a one-time event.

Labeling of Militant Animal Rights Activity

During the 1980s and 1990s, militant animal rights actors were engaged in a constant campaign with the ALF claiming between 15 and 20 actions every night.Footnote52 A Brass Tacks television program shown in 1986 reported that since 1982, groups like the ALF and ARM had undertaken some 2,000 actions per year causing £6 million worth of damage.Footnote53 While details of such actions could be found regularly in the pages of animal rights newsletters and magazines (e.g. Animal Liberation Front Supporters Group and Liberator) and latterly on websites such as the Animal Liberation Front Information Services and Bite Back, relatively few articles were found in The Guardian in comparison to alleged actions. This is not surprising given the extant literature on the media reporting of crime especially in terms of the newsworthiness of events. Research on the newsworthiness of events has identified a number of requirements (news values) for news stories including timeliness, relevance, identification, conflict, sensation and exclusivity.Footnote54 Moreover, Chibnall’s detailed study of crime reporting in the British press lists eight “professional imperatives,” which he argues guide journalists’ decisions on what they think ought to be in the news.Footnote55 More recently, Jewkes suggests that there are twelve “news structures” and “news value” that shape the reporting of crime.Footnote56 As MacDougall observes:

At any given moment billions of simultaneous events occurs throughout the world…All of these occurrences are potentially news. They do not become so until some purveyor of news gives an account of them. The news, in other words, is the account of the event, not something intrinsic in the event itself.Footnote57

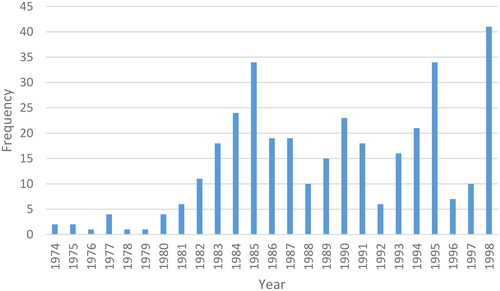

In terms of the research, over a 27-year period (1972–1998), only 347 articles were found to include details of militant animal rights actions or refer to activists or groups undertaking such actions. shows the temporal spread of articles, no articles were found in either 1972 or 1973.

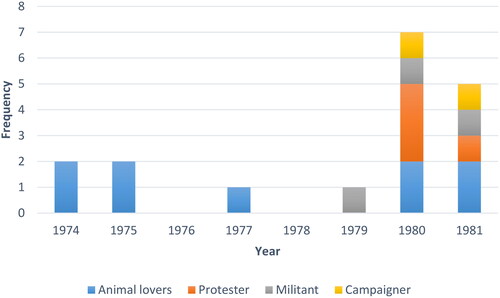

Only four articles were found mentioning the Band of Mercy during its active period (1972–1974). Group members were referred to as “animal lovers”Footnote62 and the group characterized as a “guerrilla group.”Footnote63 This characterization may be linked to the already noted group’s press statement, where they described themselves as a guerrilla organization. Moreover, the group was labeled as an animal welfare group rather than an animal rights group and considered “anti-vivisection” in nature despite some of their targets not being linked to animal experimentation.Footnote64 Press coverage also noted support for convicted member’s actions and positive comments by the trial judge on the defendants’ characters. For example, the Labour MP Ivor Clemitson joined the campaign calling for a reduction in the length of Ronnie Lee’s custodial sentence saying “I have every sympathy with Mr Lee. He made a stand against unnecessary experiments on animals and I think he is right.”Footnote65 Whereas, the judge presiding over Lee and Goodman’s trial noted they were “men of integrity and sincerity.”Footnote66

Robin Webb, an ALF spokesperson at time noted that “the late 1970s and early ‘80s saw the media treating activists, to a large extent, as well-intentioned animal lovers who, as true British eccentrics, were just taking things a little too far; they were the Robin Hoods of the animal welfare world.”Footnote67 Indeed, one of the few articles published in 1981 was concerned with the clearing of a woman, who had been charged with leading a group of masked and armed ALF members in a robbery at a farm where nine dogs were released. The judge directed the jury to find the defendant not guilty and stated “robbery is really a charge of stealing and using force. This is not a case of dishonesty – it’s a case of public disorder.”Footnote68 Webb’s observation is reflected in the labeling of militant animal rights activity as shown in .

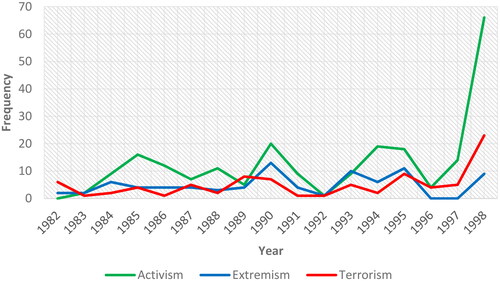

Yates, an animal rights activist argues that those involved with the animal rights campaign have increasingly been labeled as “animal terrorists” and that “the focus is firmly on the “terroristic” nature of the animal movement, whenever that label can be applied.”Footnote69 However, examination of the coding of the data from 1982 through 1988 reveals a variety of labels were applied to militant animal rights activity. The most frequently used label was activismFootnote70, which appeared 222 times across 124 articles (36%), whereas terms associated with the label terrorismFootnote71 appeared 86 times across 52 (15%) news articles and those with the label extremismFootnote72 83 times across 61 (18%) articles. shows the use of such labels from 1982 onwards.

The emergence of the ARM in 1982 coincided with the application of terms associated with the labels of extremism and terrorism. For example, following the sending of letter bombs to politicians including Margaret Thatcher, the then Prime Minster, we have the first application of the label extremists to animal rights activists and the tactic used is explicitly connected to terrorism: “Letter bombs, which have in the past been mainly used by the IRA and INLA, are a new departure for animal rights extremists.”Footnote73 Although, the ARM claimed responsibility for the letter bombs and a letter with their signature was found in one of the packages, there was some confusion initially as to the sender of the devices as the Irish National Liberation Army also claimed responsibility.Footnote74 Increases in the use of such labels can also be seen with the appearance of other animal rights groups willing to use violence against humans, namely the HRS in 1984 and the Justice Department in 1993. Articles relating to HRS activity were mainly concerned with their attempted desecration of the 10th Duke of Beaufort’sFootnote75 grave on Boxing Day in 1984 and HRS members’ subsequent trial. The group did not attract labels associated with terrorism but their actions were seen as extreme and they were referred to as the “militant wing of the animal liberation movement.”Footnote76

The use of explosives in the bomb attack on Bristol University in 1989 saw the labels of extremists and terrorism applied with universities being described as “soft targets.”Footnote77 Likewise, the planting of car bombs also resulted in the labels of extremism and terrorism featuring in articles on such attacks.Footnote78 Interestingly, while some labels concerning extremism and terrorism are applied by sources connected to law enforcement, politicians and companies and individuals targeted, some labels are also applied by journalists. For example, ErlichmanFootnote79 refers to “animal rights terrorists” while ParryFootnote80 discusses not only “animal rights terrorists” but also “animal rights terrorism,” “animal terrorists” and “extremists.”

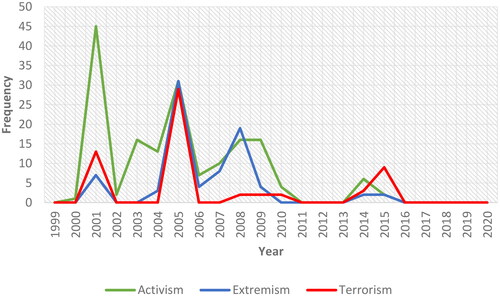

In terms of the second content analysis that focused on the coding of labels applied to SHAC, terms associated with terrorismFootnote81 appeared 60 times across 18 (29%) news articles, whereas ones associated with extremismFootnote82 appeared 70 times across 30 (48%) articles. Examination of the data also revealed the existence of other terms used more frequently to label SHAC and acts associated with its campaign beyond those associated with terrorism and extremism. Thus, the terms associated with activismFootnote83 appeared 169 times across 54 (87%) articles.

As can be seen in the terms used to label SHAC have oscillated throughout the years under study. Terms associated with activism were the most utilized throughout the early-2000s (e.g. 2000–2003). Interestingly, in 2005, all three terms were almost equally applied. SHAC’s tactical signature of intimidation, namely home-visits and e-mails, letters and telephone calls was especially prevalent between 2003 and 2005.Footnote84 Thus, it can be suggested that both journalists and their sources were deciding on the most appropriate label for SHAC and its activities. This is clearly demonstrated in the following quote:

Environmental extremists and animal rights activists, including the British-based Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty, pose one of the most serious terrorism threats to the US, according to the FBI [emphasis added].Footnote85

The application of terms associated with activism continued to have more stable usage than other terms during the mid-2000s to late-2000s. However, the labels associated with activism appear to have lost ground to terms associated with terrorism during the mid-2010s. As previously noted, terms associated with terrorism appeared 60 times across 18 news articles. On closer analysis, their use was mostly concentrated in three articles, which together accounted for 37 occurrences or 62% of the terms usage.Footnote86

Within articles where the label terrorism was found, it was used by sources opposed to SHAC and its activities. Thus, the term terrorism was employed to delegitimise the group. For example, a then Harlan U.K.’s spokesperson stated that SHAC and its acts were “animal rights terrorism.”Footnote87 Moreover, HLS spokespersons were quoted in articles labeling SHAC and its activities as not only terrorism but also “financial terrorism” and “economic terrorism.”Footnote88 Additionally, the term “urban terrorism” was used by the Conservative MP, John Major (in whose constituency HLS is located) in the House of Commons in support of legislation designed to tackle militant animal rights activity and also by Mr. Justice Butterfield in sentencing SHAC members on blackmail charges.Footnote89

It is also worth noting that terms associated with terrorism were used to label other militant animal rights actors and groups. For example, a High Court judge, Mr. Justice Owen noted that the Save Newchurch Guinea Pigs was conducting a “guerilla campaign of terrorism” in his ruling in an injunction case brought by villagers against demonstrators targeting Darley Oaks Farm.Footnote90 The deceased animal rights hunger striker Barry Horne was referred to as a terrorist and compared to the IRA’s Bobby Sands while SHAC was labeled a “pressure group” within the same article by Toolis:

In life he was a nobody, a failed dustman turned firebomber. But in death Barry Horne will rise up as the first true martyr of the most successful terrorist group Britain has ever known, the animal rights movement. […] Horne was a dedicated animal rights terrorist [emphasis added].Footnote91

Conclusion

As acknowledged elsewhere “the news is not an objective presentation of political reality, but an interpretation of events and issues from the perspective of reporters, editors, and selected sources.”Footnote92 The framing and labeling of an event or an actor in a specific way promotes a particular interpretation of events and affects readers’ perception of that event or actor. As Wagner points out the labeling of an event or actor as terrorism involves not only a “powerful rhetorical technique” but also creates “an irreversible frame.”Footnote93 Moreover, “newspapers remain pivotal in setting the public policy agendas around crime and criminal justice.”Footnote94 Within the U.S., the labeling of militant animal rights activity as “eco-terrorism” has resulted in the introduction of specific legislation resulting in the harsher sentencing of such activists convicted of arson and vandalism. In the U.K., counter-terrorism police included a number of animal rights groups including the ALF and SPEAK on a list of extremist ideologies. The list also included Extinction Rebellion, a nonviolent environmental protest group.Footnote95

The present research has analyzed how The Guardian newspaper labeled militant animal rights activity since its emergence in 1972 up until 1998 before focusing on a particular group, SHAC in the years between 1999 and 2020. Our research demonstrated that at least in terms of The Guardian for the time periods analyzed, both militant animal rights activity and SHAC were largely labeled as activism as opposed to terrorism. This is in contrast to research conducted on the labeling of similar activity in the U.S. undertaken by environmentalists, notably the Earth Liberation Front, which found that the U.S. print media saw such activity as terrorism and in particular, eco-terrorism.Footnote96 Moreover, the terms associated with extremism and terrorism were nearly equally applied to militant animal rights activity in the period between 1982 and 1988 while in terms of SHAC the label extremism was applied more often. This may in part be as a result of SHAC operating on the one hand as an above ground organization as opposed to groups like the ALF, ARM, HRS and Justice Department who operated underground. On the other hand, some members of SHAC carried out militant animal rights activity, which was claimed by the ALF.

We recognize that our research has limitations in that only one broadsheet newspaper was selected for analysis. Whilst The Guardian is considered the most trustworthiness, accurate and quality newspaper in Britain, it is also regarded as being the most left-wing newspaper.Footnote97 Future work could include expanding the research to other newspapers from across the political spectrum including tabloid titles, which may offer alternative results.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Robert Garner, Animals, Politics and Morality (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993); Robert Garner, “Defending Animal Rights,” Parliamentary Affairs 51, no. 3 (1998), 458–469, doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pa.a028810.

2 Like other social constructs, the term “militant” has various definitions as to what constitutes a militant act or person and militancy more generally. The term has been used frequently with respect to the women’s suffrage movement in the UK in the early twentieth century to distinguish between those activists and organisations willing to use unlawful methods in the pursuit of votes for women and those activists and organisations who pursued lawful methods. See Laura E. Nym Mayhall, “Defining Militancy: Radical Protest, the Constitutional Idiom, and Women’s Suffrage in Britain, 1908-1909,” Journal of British Studies 39, no. 3 (2000), 340-371, doi: 10.1086/386223 for a good discussion of this. In contrast, Gerard Saucier, Laura G. Akers, Seraphine Shen-Miller, Goran Kneževié and Lazar Stankov, “Patterns of Thinking in Militant Extremism,” Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, no. 3 (2009), 256-271, doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01123.x define militancy as involving an ‘intention and willingness to resort to violence’ (p. 256). The ALF has also described its actions as militant (see for example John Ezard, “Homes Attacked in Protest Over Tests on Animals,” The Guardian, January 5, 1981, 20.

3 Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler and Cas Mudde, “‘Ecoterrorism’: Terrorist Threat or Political Ploy?,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 37, no. 7 (2014), 596, doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2014.913121.

4 David T. Sumner and Lisa Weidman, “Eco-terrorism or Eco-tage: An Argument for the Proper Frame,” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 20, no. 4 (2013), 855-876, doi: 10.1093/isle/ist086.

5 Travis Wagner, “Reframing Ecotage as Ecoterrorism: News and the Discourse of Fear,” Environmental Communication 2, no. 1 (2008), 25–39, doi: 10.1080/17524030801945617.

6 G. Davidson Smith, “Single Issue Terrorism,” Commentary (Canadian Security Intelligence Service) 74 (1998). https://fas.org/irp/threat/com74e.htm#r4; Walter Laqueur, The New Terrorism: Fanaticism and the Arms of Mass Destruction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999); Southern Poverty Law Center, “Eco-violence: The Record,” Intelligence Report 2015, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2015/eco-violence-record (accessed January 31, 2022).

7 James M. Inhofe, “Eco-terrorism Specifically Examining the Earth Liberation Front and the Animal liberation Front,” Senate Hearing 109-947, Committee on Environment and Public Works (2005, May 18), 1, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-109shrg32209/html/CHRG-109shrg32209.htm (accessed January 31, 2022).

8 John Lewis, “Eco-terrorism Specifically Examining the Earth Liberation Front and the Animal liberation Front,” Senate Hearing 109-947, Committee on Environment and Public Works (2005, May 18), 12, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-109shrg32209/html/CHRG-109shrg32209.htm (accessed January 31, 2022).

9 Hirsch-Hoefler and Mudde, “‘Ecoterrorism’”; Sumner and Weidman, “Eco-terrorism or Eco-tage.”

10 Paul J. Karasick, “Curb your Ecoterrorism: Identifying the Nexus between State Criminalization of Ecoterror and Environmental Protection Policy,” William & Mary Environmental Law & Policy Review 33, no. 2 (2009), 581-603.

11 Hirsch-Hoefler and Mudde, “‘Ecoterrorism’,” 588.

12 Gordon Mills, “The Successes and Failures of Policing Animal Rights Extremism in the UK 2004-2010,” International Journal of Police Science & Management, 15, no. 1 (2013), 33, doi: 10.1350/ijps.2013.15.1.299

13 Ronnie Lee, “Direct Action History Lessons: The Formation of the Band of Mercy and A.L.F.,” No Compromise 28, (2005, Fall), 25; Elzbieta Posluszna, Environmental and Animal Rights Extremism, Terrorism, and National Security (Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2015).

14 The Hunt Saboteurs Association (HSA) established in 1963 engages in direct action to disrupt hunts by laying false scents to confuse hounds, blowing horns, feeding meat to the hounds, locking gates and preventing hunt members from digging out foxes who have gone to earth (HSA, “History,” 2022, https://www.huntsabs.org.uk/about-the-hsa/). For an interesting discussion of the dynamics between the hunt and the saboteurs see Ian Noble, “Peace Signs and Placards, Blue Lights and Breach,” Police Journal 60, no. 4 (1987), 317-320, doi: 10.1177/0032258X8706000409. In July 1974, a member of the HSA offered a reward of £250 for information about the Band of Mercy and stated to the press that ‘We approve of their ideals, but are opposed to their methods’ (cited in Noel Molland, “Thirty years of direct action,” in Terrorists or Freedom Fighters? Reflections on the Liberation of Animals, ed. Steve Best and Anthony J. Nocella II (New York: Lantern Books, 2004), 71.

15 Rachel Monaghan, “Animal Rights and Violent Protest,” Terrorism and Political Violence, 9, no. 4 (1997), 106-116, doi: 10.1080/09546559708427432; Rachel Monaghan, “Terrorism in the Name of Animal Rights,” Terrorism and Political Violence 11, no. 4 (1999), 159-169, doi: 10.1080/09546559908427538; Rachel Monaghan, “Not Quite Terrorism: Animal Rights Extremism in the United Kingdom,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 36, no. 11 (2013), 933-951, doi:10.1080/1057610X.2013.832117.

16 Cub hunting involves the hunting of fox cubs by young hounds in their training to hunt. See League against Cruel Sports, “Cub hunting,” 2022, https://www.league.org.uk/cub-hunting for more details.

17 Lee cited in Arkangel, “ALF, The early years – part 1,” Arkangel 30 (n.d.), 20.

18 The Guardian, “Animal lover threatens to fast,” The Guardian, March 25, 1975, 8.

19 David Henshaw, Animal Warfare (London: Fontana, 1989).

20 Lee cited in João da Silva, “The Eco-terrorist Wave,” Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 12, no. 3 (2020), 208, doi:10.1080/19434472.2019.1680725.

21 Monaghan, “Animal Rights”; Richard D. Ryder, Animal Revolution (Oxford: Blackwells, 1989); Keith Tester and John Walls, “The Ideology and Current Activities of the Animal Liberation Front,” Contemporary Politics 2, no. 2 (1996), 79-90, doi: 10.1080/13569779608454729.

22 Animal Liberation Front, The ALF Primer, 3rd ed. (n.d.), 7. https://animalliberationpressoffice.org/publicationsonline/alf_primer_3rdedition_imposed.pdf

23 Cited in Robin Webb, “Animal Liberation – By “Whatever Means Necessary,” in Terrorists or Freedom Fighters? Reflections on the Liberation of Animals, ed. Steve Best and Anthony J. Nocella II (New York: Lantern Books 2004), 79.

24 Garner, Animals, politics and morality; Monaghan, “Not quite terrorism.”

25 Monaghan, “Terrorism in the name of animal rights,”; David Pallister, “Grave Attack Activists Warn of Violence,” The Guardian, December 27, 1984, 1; Posluszna, Environmental and Animal Rights Extremism.

26 Monaghan, “Not quite terrorism.”

27 Animal Rights Militia, “Communique,” Bite Back Magazine, August 28, 2007, https://www.directaction.info/news_aug28_07.htm; The Guardian, “Eggs ‘Injected with Poison’,” The Guardian, March 13,1985, 3.

28 Janet George, “The Real Animals: P.S.,” The Guardian, December 31, 1993, 20; Pallister, “Grave attack activists.”

29 Monaghan, “Terrorism in the name of animal rights.”

30 Monaghan, “Not quite terrorism.”

31 Lee, “Direct action history lessons,” 25.

32 Monaghan, “Not quite terrorism.”

33 Alok Jha, “As Activists Try to Stop Construction of University’s Research Building, Scientists Call for a Crackdown on Extremists,” The Guardian, July 19, 2004, 3; Sandra Laville, “Animal Militants Set Fire to Oxford Boathouse: University Targeted in Arson Campaign to Halt Construction of Primate Research Centre,” The Guardian, July 21, 2005, 2.

34 Quoted in Jha, “As activists try to stop construction,” 3.

35 R. v Broughton [2010] 549 EWCA Crim, WL 4007021.

36 David Metcalfe, “The Protest Game: Animal Rights Protests and the Life Sciences Industry,” Negotiation Journal 24, no .2 (2008), 125-144, doi: 10.1111/j.15719979.2008.00173.x; Posluszna, Environmental and Animal Rights Extremism; Andrew Upton, “‘Go On, Get Out There, and Make it Happen’: Reflections on the First Ten Years of Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (SHAC),” Parliamentary Affairs 65, no. 1 (2012), 238–254., doi:10.1093/pa/gsr027.

37 Rune Ellefsen and Joel Busher, “The Dynamics of Restraint in the Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty Campaign,” Perspectives on Terrorism 14, no. 6 (2020), 165.

38 John Donovan and Richard T. Coupe, “Animal Rights Extremism: Victimization, Investigation and Detection of Campaign of Criminal Intimidation,” European Journal of Criminology 10, no. 1 (2013), 113-136, doi:10.1177/1477370812460609.

39 Esther Addley, “Animal Liberation Front Bomber Faces Jail after Admitting Arson Bids: Police Hail Conviction of Anti-vivisection Extremist: Investigation into ‘Seven or Eight’ Similar Offences,” The Guardian, August 18, 2006, 4; Esther Addley, “Animal Liberation Front Bomber Jailed for 12 Years: Victim Was Left Living in State of Fear, Court Told Conviction Devastating Blow to Extremists,” The Guardian, December 8, 2006, 7.

40 The Guardian, “Animal Rights Group Threatens Nurseries,” The Guardian, September 29, 2005, 1.

41 Donovan and Coupe, “Animal rights extremism,” 123.

42 Wagner, “Reframing ecotage as ecoterrorism,” undertook a content analysis of six national US daily newspapers using ProQuest Newspapers from the beginning of 1984 until the end of 2006 for a range of terms related to eco-terrorism yielding 155 news stories. Paul Joosse, “Elves, Environmentalism, and ‘Eco-terror’: Leaderless Resistance and Media Coverage of the Earth Liberation Front,” Crime Media Culture 8, no. 1 (2012), 75-94, doi: 10.1177/1741659011433366 examined 62 New York Times articles compiled using Proquest Newsstand from October 1998 until November 2009 for the search terms related to the Earth Liberation Front. Sumner and Weidman, “Eco-terrorism or eco-tage” explored a 10-year period from the beginning of 1999 - 25 September 2009 using LexisNexis Academic and its source category ‘US Newspapers and Wires’. Searched terms related to eco-terrorism yielding a sample of 594 articles. An article by John Sorenson, “Constructing Terrorists: Propaganda about Animal Right,” Critical Studies on Terrorism 2, no. 2 (2009), 237-256, doi: 10.1080/17539150903010715 while concerned with animal rights used the Factiva database and appears not to confine the search to any particular country, dates consulted are not noted and the number of articles selected for examination while given for various search terms are not clarified as final sample sizes (e.g. removal of duplicate articles etc.).

43 Cited in Kimberly A. Neuendorf, The Content Analysis Guidebook, 2nd ed. (Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, 2017), 16.

44 Donovan and Coupe, “Animal rights extremism”; Monaghan, “Not quite terrorism.”

45 It was not possible to use the same database to cover both periods as the LexisNexis database for the chosen newspaper is only available from July 1984 and the ProQuest Historical Newspapers has an end date of 2003.

46 Chris Baynes, “Animal Rights Campaigners Sentenced after Protest Group Sent ‘Aids-Contaminated’ Post to Researchers,” The Independent, January 26, 2018, 2.

47 Ofcom, “New Consumption in the UK: 2020,” (Ofcom, London, August 13, 2020), https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/201316/news-consumption-2020-report.pdf. The Guardian was also found to be the most trusted newspaper brand in the UK by research conducted by the Pew Research Centre and by the UK Publishers Audience Measurement Company (PAMCo) – for more details see Jim Waterson, “Guardian Named UK’s Most Trusted Newspaper,” The Guardian, October 31, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2018/oct/31/guardian-rated-most-trusted-newspaper-brand-in-uk-study.

48 A search for “SHAC” brought up articles concerned with other organisations and businesses that had the same name or acronym such as Shac Communications, a lobbying and PR firm and Shelter Housing Aid Centre.

49 When the same news story had more than one version, the latest one was used. This occurred with “Court jails Huntingdon animal test lab blackmailers” (2009) and “Animal rights campaigner: ‘I’m a scapegoat’” (2014).

50 Hsiu-Fang Hsieh and Sarah E. Shannon, “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis,” Qualitative Health Research, 15, no. 9 (2005), 1285, doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687.

51 Ibid; Satu Elo, Maria Kääriäinen, Outi Kanste, Tarja Pölkki, Kati Utriainen and Helvi Kyngäs, “Qualitative Content Analysis: A Focus on Trustworthiness,” SAGE Open, 4, no. 1 (2014), doi: 10.1177/2158244014522633.

52 Monaghan, “Terrorism in the name of animal rights.”

53 Garner, Animals, politics and morality.

54 Tony Harcup and Deirdre O’Neill, “What is News?,” Journalism Studies 18, no. 12 (2017), 1470-1488 doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2016.1150193

55 Chibnall’s (1977) eight ‘professional imperatives’ include immediacy, dramatisation, personalisation, simplification, titillation, conventionalism, structured access and novelty. For more details, see Steve Chibnall, Law and Order News: An Analysis of Crime Reporting in the British Press (London: Tavistock, 1977).

56 Jewkes’ (2015) twelve ‘news structures’ and ‘news values’ are threshold, predictability, simplification, individualism, risk, sex, celebrity or high status persons, violence or conflict, visual spectacle or graphic imagery, conservative ideology and political diversion, proximity and children. For more details, see Yvonne Jewkes, Media and Crime, 3rd ed. (London: SAGE Publications, 2015).

57 Cited in Tim Newburn, Criminology (London: Routledge, 2017), 79.

58 Wagner, “Reframing ecotage as ecoterrorism,” 27.

59 Paul Mason, “Misinformation, Myth and Distortion,” Journalism Studies 8, no. 3 (2007), 481-496, doi: 10.1080/14616700701276240; Peter L.M. Vasterman, “Media-Hype: Self-Reinforcing News Waves, Journalistic Standards and the Construction of Social Problems,” European Journal of Communication, 20, no. 4 (2005), 508–530, doi: 10.1177/0267323105058254.

60 Fiona Fox, “Shocking’ Animal Rights Exposés by Newspapers were Nothing of the Kind,” The Guardian, October 7, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/science/2014/oct/07/animal-rights-uk-newspapers-buav

61 Home Office, “Report of ASRU Investigation into compliance” (Home Office, London, 2014), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/compliance-investigations-by-the-animals-in-science-regulation-unit, 7.

62 The Guardian, “Animal lover threatens to fast.”

63 John Ezard, “Guerrilla War for Animals,” The Guardian, July 12, 1974, 8.

64 Ibid; The Guardian, “Visiting Ban on Hunger Striker,” The Guardian, March 29, 1975, 5.

65 Quoted in The Guardian, “Visiting ban on hunger striker,” 5.

66 The Guardian, “Animal lover threatens to fast,” 8.

67 Webb, “Animal liberation,” 77.

68 The Guardian, “Leader of Dogs Raid Cleared of Robbery,” The Guardian, December 8, 1981, 4.

69 Roger Yates, “Media dance,” Arkangel, 30 (n.d.), 15.

70 Activism code included terms “activism” and “activists”.

71 Terrorism code included terms “terror”, “terrorism”, “terrorist(s)”, “terrorising” and “terrorised”.

72 Extremism code included terms “extremism”, “extremist(s)” and “extreme”.

73 Gareth Parry, “Downing Street Security Review Follows Bombs,” The Guardian, December 2, 1982, 2.

74 Ibid.

75 The 10th Duke of Beaufort was a former master of the Beaufort Hunt and one of Britain’s most prominent huntsmen.

76 Pallister, “Grave attack activists,” 1.

77 Dennis Johnson, “Campus Blast Raises Fears,” The Guardian, February 24, 1989, 28; Tim Radford, “Universities ‘Soft Target’ for Extremists,” The Guardian, February 24, 1989, 2.

78 Joanna Coles, “Animal Rights’ Bomb Hits Vet,” The Guardian, June 9, 1990: 3; Gareth Parry, “Animal Crusaders Who Risk Murder,” The Guardian, June 11, 1990, 3.

79 James Erlichman, “‘Final Blow’ Dealt to Live Animal Exports,” The Guardian, August 31, 1994, 4.

80 Parry, “Animal crusaders,” 3.

81 Terrorism code included terms “terror”, “terrorism” and “terrorist(s)”.

82 Extremism code included terms “extremism” and “extremist(s)”.

83 Activism code included terms “activism” and “activist(s)”.

84 Donovan and Coupe, “Animal rights extremism”; Mills, “The successes and failures.”

85 Jamie Wilson, “FBI calls UK Animal Activists Terrorists,” The Guardian, May 20, 2005, 2

86 Ibid.; Peter Huck, “Collateral Damage,” The Guardian, March 2, 2005, 2; Ben Quinn, “City of London Police Put Occupy London on Counter-terrorism Presentation with al-Qaida; Anti-capitalist Campaigners Described as ‘Domestic Extremism’ and Put on Slide With Pictures of 2005 London Bombing and the 1996 IRA Bombing,” The Guardian, July 20, 2015, 13.

87 Paul Kelso and Steven Morris, “Haphazard Army with the Scent of Victory,” The Guardian, January 18, 2001, 5. Harlan UK is a privately owned supplier of laboratory animals and has been targeted by militant animal rights activity.

88 Andrew Clark, “Moving Habitat Huntingdon Life Sciences to List in the US,” The Guardian, January 18, 2001: 25; Steven Morris, “Haphazard Army with the Scent of Victory,” The Guardian, January 16, 2001: 7.

89 Owen Bowcott, “Court Jails Huntingdon Animal Test Lab Blackmailers,” The Guardian, January 21, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2009/jan/21/huntingdon-animal-rights; Mary O’Hara and Peter Hetherington, “Crank or Campaigner? After Ten Nail Bombs Police Still Cannot Decide,” The Guardian, February 10, 2001, 14.

90 Mark Honigsbaum, “Guinea Pig Activists avoid Clampdown,” The Guardian, March 18, 2005, 4.

91 Kevin Toolis, “Inside Story: To the Death,” The Guardian, November 7, 2001, 6.

92 Wagner, “Reframing ecotage as ecoterrorism,” 27.

93 Ibid., 25.

94 Chris Greer and Eugene McLaughlin, “News Power, Crime and Media Justice,” in The Oxford Handbook of Criminology, ed. Alison Liebling, Shadd Maruna and Lesley McAra, 6th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 261.

95 Vikram Dodd and Jamie Grierson, “Terrorism Police List Extinction Rebellion as Extremist Ideology,” The Guardian, January 10, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/jan/10/xr-extinction-rebellion-listed-extremist-ideology-police-prevent-scheme-guidance.

96 Joosse, “Elves, environmentalism, and ‘eco-terror’”; Sumner and Weidman, “Eco-terrorism or eco-tage”; Wagner, “Reframing ecotage as ecoterrorism.”

97 Matthew Smith, “How Left or Right-wing are UK’s Newspapers?,” YouGov, March 7, 2017, https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2017/03/07/how-left-or-right-wing-are-uks-newspapers (accessed January 31, 2022).