Abstract

Violent extremists’ communications regularly yield lethal consequences. Yet despite this importance, no clear framework yet exists that exposes in a coherent way the various markers of violent extremist language. We construct a theoretical model of violent extremists’ language, integrating and refining existing approaches from different academic fields into a comprehensive account of its semantic content and structure. We evidence the empirical accuracy of this model by applying on the magazines of two ideologically different extremist groups (ISIS and US National-Socialist Movement) a bespoke computational text analysis method revealing the specific connections between the nouns, verbs, and adjectives of violent extremist corpora identified in our theoretical model.

Political actors communicate to influence their audiences’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Violent extremist groups and individuals, past and present, are no exception. From Nazis’ high-budget propaganda machine to the low-cost—but high impact—Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines in 1993–1994 Rwanda, from Ted Kaczynski’s luddite manifesto to Anders Breivik’s “compendium” of Islamophobic prose, ideologies and means of communication have differed but the goal remains the same: to disseminate radical worldviews and encourage violence. The digital revolution and subsequent boom in online communication have allowed violent extremists to reach larger audiences and employ ever-improving tools for crafting high-quality outputs, unlocking new possibilities for collaborationFootnote1 while simultaneously creating new dilemmas and vulnerabilities.Footnote2 This rapid evolution, further accelerated by the arrival of Artificial Intelligence, has created a landscape fertile for the viral dissemination of extremist discourse.Footnote3

Facing this new context where extremist content spreads faster and more widely than before, academic research on extremist communications has naturally become clustered around single ideologies/groups specialties (e.g. ISIS/jihadism specialists, far-right experts, etc.), producing case-specific findings on the key features and characteristics of these communications, such as their network-like architecturesFootnote4 or their major themes and narratives. Comparative studies remain the exception.Footnote5

While conducive to much-needed empirical work, this situation has, we argue, distracted scholars from higher-level questions on the nature of violent extremist communication as a single type of phenomenon behind its different instantiations. A strong overarching understanding of violent extremists’ communications, which rests on theoretical frameworks and methodologies which transcend case-specific observations, remains to be built. And within this ambitious agenda, we suggest that research ought first to identify the common linguistic markers that characterize violent extremists’ language across the ideological spectrum. Efforts to identify such markers do exist, but they are surprisingly rare and disconnected across several academic disciplines, with no coherent and comprehensive effort to bring them together. In 1989, Maass and colleagues opened a rich research agenda in Social psychology by observing that “surprisingly, the role of language in the maintenance and transmission of stereotypes has largely been ignored”Footnote6; yet about two decades after, Reicher and colleagues’ still lamented that “studies very rarely look at precisely what is being said” by “entrepreneurs of hate.”Footnote7 Recently, Baele continued to deplore that “the important role of language in triggering and sustaining political violence has […] been overlooked.”Footnote8

The present article addresses this need by identifying, coalescing, and complementing two major yet imperfect existing conceptualizations of the formal markers that characterize extremists’ language, thereby providing a single, more comprehensive theoretical model whose empirical accuracy is then evidenced by comparing two cases of extremist propaganda—ISIS on the one hand, and the US National-Socialist Movement (NSM, neo-Nazi) on the other hand—both analyzed with a recent computational method we tailored specifically to the study of such language. The framework, matching method, and empirical work, allow us to identify several markers of violent and nonviolent extremist language, and explain how they work together.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. In a first, theoretical step, we identify and review the two main existing theoretical frameworks seeking to identify the formal markers of violent extremists’ language, both of which developed from a desire to explain the role of this language in audiences’ radicalization and commitment to violence. One approach concentrates on how extremists identify and portray their enemies and themselves; in other words, it focuses on group identity claims and stresses the importance of certain types of nouns and adjectives. The other approach highlights extremists’ claims about the harm their enemies do to them (sometimes understood together as a crisis narrative) as well as the harm that they do their enemies (the solution narrative); in other words, it focuses on political action and stresses the significance of the particular verbs used. We then offer a unifying ideal-typical model integrating all these lexical features together, coalescing the two approaches and adding four important features. We connect the features of the model to considerations on radicalization, following Braddock’s encouragement to trace radicalization dynamics back to persuasive language.Footnote9

In a second, methodological step, we develop a computational technique for the generation of semantic networks, which directly enables the comparison of real empirical cases with our theoretical model. Specifically, we draw on recent advances in semantic analysis and probabilistic dependency parsing to extract from text relevant grammatical associations between the nouns, adjectives, and verbs of a given corpus. The transferability of this method will allow scholars and practitioners to efficiently study the language of a wide range of violent extremists, pushing forward the study of higher-level features detectable across cases.

In a third, empirical step, we apply our method to gain insights into the communication of ISIS and the NSM, whose respective magazines offer two comparable yet different cases against which to evaluate our theoretical model. We discuss our results under the light of the theories underpinning our framework, paying attention to the different levels of violence exerted by the two extremist organizations when analyzing their language.

Our contribution is therefore threefold. Theoretically, we advance the conceptual understanding of the formal markers characterizing violent extremists’ language by offering an empirically robust integrated theoretical model. This endeavor not only seeks to contribute to the several disciplines covered here, but also hopes to build bridges between their siloed research agendas. While many of its features will not strike specialists of extremist language as fundamentally new, this is the first attempt to include and connect them all into a single model that can act as a valuable theoretical blueprint for the field. Methodologically, we develop a scalable computational approach to aid in the systematic study of extremist communications (and polarizing discourse more broadly). This is especially valuable in a world of ever-increasing volumes of radical content circulating on the internet, requiring computational tools to quickly reveal not only key themes and ideas but also the extremity of the expressed beliefs. Empirically, the article strengthens an already rich research program on extremist and violent groups’ communications, which needs more theoretical effort to expose common dynamics and characteristics across cases. It offers a systematic and coherent way to consider together important features already identified, in a disjointed way, in existing studies. It also contributes to the already rich literature on how extremist magazines and other outputs foster radicalization and participate in the creation of extremist communities.Footnote10

Theory: An Integrated Lexical Model of Violent Extremists’ Language

Two main approaches co-exist in the literature on violent extremists’ language. The first one, which has its roots in the Social Identity paradigm in Social Psychology, focuses on in-/out-group depictions, suggesting that derogatory or dehumanizing labels and highly negative descriptions are the hallmarks of violent extremist language. The second one, which can be identified in a wider range of academic fields, emphasizes that violent extremists’ language consistently reinforce victimization narratives whereby the ingroup is claimed to face an existential threat from the relentless violence of the outgroup. Each subsumes a different explanation as to why these linguistic features reflect—and inspire—extremism, and sometimes violence.

The Social Identity Approach

The first approach argues that violent political extremists’ language is above all characterized by strong group identity appeals, more precisely a Manichean depiction of a social world made of two sharply distinguished groups: a positively described ingroup and negatively described out-group. As Donohue and Hamilton suggest in their recent review, this language “is driven largely by the need to reinforce intergroup identity.”Footnote11 Such a stance logically emerged from the Social Identity paradigm developed in the wake of seminal Social Psychology works like Allport’s or Tajfel’s,Footnote12 which showed that intergroup relations are heavily determined by the context and processes through which group categories are established, shared, and perceived. From that perspective, self- and other- categorization plays a crucial “meaning-giving, identity-conferring function in perception,”Footnote13 and it has been shown that individuals tend to overstate the homogeneity of both their own ingroup and the other groups they believe exist through a group homogenization effect where “perceived similarity within, and difference between, categories” is exaggerated.Footnote14 This homogenization effect is all the stronger among people who hold “essentialist” beliefs about social categories, that is, think groups’ characteristics are immutable and historically stable and therefore conceptualize social groups as sharply separated and unalterable.Footnote15 Essentialist beliefs about categories therefore deepens perceived differences and incompatibilities between social groups, and, crucially, are correlated with justification for inequalities disadvantaging the outgroupFootnote16 as well as increased prejudice and willingness to support ingroup action against outgroups.Footnote17

In a landmark contribution, Maass and colleagues brought these considerations from the study of cognition and behavior to that of language as such.Footnote18 They observed differences in how people describe the behaviors of their in-group versus those of their out-group, highlighting how language perpetuates positive stereotypes of the ingroup and negative stereotypes of the outgroup. Classifying words according to their level of abstractness, Maas and colleagues specifically observed a “linguistic intergroup bias,” i.e. that people communicate desirable ingroup and undesirable outgroup behaviors more abstractly than undesirable ingroup and desirable outgroup behaviors. Adjectives, which top the scale of abstractness, play a key role in essentializing the outgroup negatively (e.g. “deceitful,” “greedy”) and the ingroup positively (e.g. “honest,” “strong”).

This research paved the way for studies focusing directly on language in intergroup conflict and instance of extremism, with the underlying assumption—in line with the broader Social Identity paradigm—that the difference between this type of language and “normal” linguistic intergroup bias (and, further, polarizing language) is one of degree, not kind. Donohue and Hamilton, for example, clearly theorize an intensity scaling where depersonalization paves the way to the more extreme dehumanization.Footnote19 In a series of studies, Reicher and colleagues described the rhetoric tactics used by “entrepreneurs of hate” who seek to create group essentialist homogenization effects by encouraging perceptions of a virtuous ingroup opposed to a negative outgroup. On the one hand, the consistent use of exclusive in- and out- group labels, and the systematic negative portrayal of the outgroup and positive characterization of the ingroup with evocative adjectives (“worthless,” “impure,” etc., against “brave,” “pure,” etc.) reinforce polarized, exclusive social identities.Footnote20 On the other hand, two additional “techniques of reification” further essentialize ingroup and outgroup categories in ways that further sharpen their boundaries: through “naturalization,” group characteristics and behaviors are presented as the inevitable outcome of natural characteristics (e.g. use of scientific or psychological terms), and through “eternalization” groups and their characteristics are claimed to have existed in the same fundamental way for times immemorial.Footnote21 Group categories and their negative or positive attributed identities are thus presented to appear natural and impermeableFootnote22 and, more importantly, deserved and morally desirable: polarized essentialized identities become both at once heuristic devices for “understanding particular intergroup relationships” and tools for “justifying behaviour towards outgroup members.”Footnote23 In its most extreme form, such language includes dehumanization as a discursive strategyFootnote24 using contemptible labels (e.g. “parasites,” “snakes,” “monkeys”) that exacerbate this differentiation through the construction of an outgroup identity that is in-/sub-human, for example by implying that it is incapable of prosocial values or that it is solely driven by animalistic impulses such as greed or lust.Footnote25 Donohue combined these dimensions in his discussion of the “identity trap” characterizing the “language of genocide,” which immixes them all to “establish a social context that builds up the speaker’s social identity while denigrating the ‘enemy’s’ social identity.”Footnote26

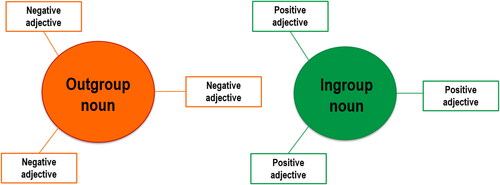

In sum, the language of “entrepreneurs of hate” is therefore one marked by a Manichean structure maximizing the alleged differences between an ingroup and its outgroup—a process usually called “metacontrast.” Schematically, this language can thus be modeled as in . Lexically, the key linguistic features are the nouns used to identify the ingroup and the outgroup and the adjectives used to characterize each. Such an approach subsumes that the key mechanism of radicalization at play with violent extremist communication is that language’s ability to play with people’s need for positive affiliation and status to create among the audience an uncompromising sense of belonging to an outstanding ingroup facing an execrable outgroup. The outgroup is hated—and conversely the ingroup is loved—because of who they are.

Evidence for this model abounds. Classic studies of violent extremists’ communications have indeed unveiled Manichean structures based on reified in-/out-group nouns (regularly derogatory and sometimes dehumanizing ones) and positive/negative adjectives. Most analyses of “Hutu Power”-operated radio before and during the Rwandan genocide, for instance, revealed the discursive construction of a sharp identity distinction between Hutus and TutsisFootnote27 with the salience of dehumanizing outgroup labels and offensive adjectives increasing as violence erupted and worsened.Footnote28 Similarly, scholars have noted the binary character of Nazi propaganda, opposing a pure “Aryan” German ingroup imbued with the best qualities to an extremely negative Jewish outgroup, with individuals belonging to either the in-group or out-group.Footnote29 Studying a more recent case, Ramsay has shown how ISIS’ consistent use of outgroup dehumanization to depict its enemies polarizes in-/out-group identities,Footnote30 creating a social world which, to take the group’s own words, has no “gray zone.” Contemporary white supremacist prose abounds with glorifying ingroup labels such as “warriors” or “knights,” facing outgroups dehumanized as “apes” or “chimps.” In their review of the effects of dehumanization, Rai, Valdesolo and Graham found that it increases instrumental violence.Footnote31

This linguistic process directly fuels known mechanisms of radicalization. To use Hafez and Mullins’ typology of radicalizing mechanisms,Footnote32 of example, such language contributes to the “ideology” mechanism whereby individuals embrace a new identity that has more meaning, importance, value, and agency as their previous one. Berger’s seminal conceptualization of extremism rests on this foundational construction of essentialized and antagonistic in-/out-group identities,Footnote33 as do many other frameworks.

The Existential Threat Approach

An alternative approach emphasizes that extremists’ language is “not simply [made] of extreme perceptions of in and out-groups’ identities (who they are) but also of perceptions of these groups’ actions (what they do).”Footnote34 Specifically, it stresses the insisting claim, in violent extremists’ language, that the outgroup constitutes an existential threat to the ingroup, which therefore needs to be defended. Two types of damaging actions have been noted by the literature.

First, authors have documented that violent extremists invariably claim that their ingroup suffers from unbearable physical violence waged by an outgroup, whose aim is sometimes alleged to be no less than the extermination of the ingroup. For instance, experts of the propaganda preceding and accompanying the Rwandan genocide have insisted on the ubiquity of claim that Tutsis were waging an extermination campaign against the Hutus, marked by barbaric acts such as the dismembering of babies or rape with extreme violence leading to death.Footnote35 McDoom makes this narrative a central driver of the violence.Footnote36 Similarly, detailed analyses of the dominant themes voiced by jihadist organizations like al-Qaeda and ISIS have shown that these groups cultivate the perception that Muslims (and in particular women and children) are routinely being killed and injured by Western “crusaders” and other enemies.Footnote37 Ebner’s comparative analysis of the “cumulative extremism” produced by interacting jihadist and far-right discourse identified this “victims and demons” dialectic as a common rhetorical trope across her corpora, with both radical Islamists and right-wing extremists propagating stories of rape, brutality, and relentless aggression.Footnote38 Ingram’s influential conceptualization of violent extremist propaganda as consisting of a “crisis-solution” dialectic stresses the foundational role of constructing among the target audience the perception that harm and violence have reached unprecedented levels (crisis) warranting an urgent—and violent—solution to protect the ingroup.Footnote39

Second, other scholars have noticed the ubiquity of conspiracy theories in violent extremists’ prose; this time, the claim is that the ingroup is the victim of more covert, less directly violent actions carried out by distant groups who aim to maintain them in a state of oppression and subjugation. Conspiracy theories—which have classically been defined as a “schema whereby a given group of people sharing a common ethnic, political, national, or religious origin is said to plot against another group […and whose…] unifying theme is the external placing of blame for some highly negative events”—Footnote40 have been shown to encourage negative attitudes to other groupsFootnote41 as well as acceptance of violence against the deemed culprit,Footnote42 and have been conceptualized as “radicalizing multipliers”Footnote43 strategically mobilized by “conspiracy entrepreneurs.”Footnote44 Baele summarized that conspiratorial narratives constitute no less than “the structuring linguistic marker” of language justifying and triggering violence.Footnote45 More and more case-studies of violent extremist communications reveal their conspiratorial structure, to the point that Bartlett and Miller observe that “conspiracy theories are widely prevalent across this extremist spectrum, despite the vast differences in the extremist ideologies themselves.”Footnote46 Des Forges’ analysis of the Rwandan genocide for instance highlighted the multi-layered character of the message aired by RTLM and Radio Rwanda, stressing, for instance, the importance of claims that distant outgroups such as the Belgians’ plot with Tutsis.Footnote47 For Kallis,Footnote48 the most important characteristic of Nazi messaging was its articulation of a conspiratorial structure linking a series of distinct nefarious actors (“international Jewry,” “plutocrats,” Communists, etc.) whose concealed interactions fundamentally threatened German identity.Footnote49 Fekete’s analysis of Anders Breivik’s “compendium” similarly exposed its conspiratorial structure,Footnote50 while Baele, Brace and Coan observed that conspiratorial verbs like “control,” “indoctrinate” or “brainwash” are ubiquitous in Incel online chatrooms.Footnote51 These conspiracies stress efforts by outgroups not only to undermine the ingroup but also to eventually eliminate it, either by making its existence unsustainable (e.g. Western support for despots in the Middle East, International Jewry purposefully collapsing German economy) and/or by gradually eroding its purity (e.g. Tutsi women seducing Hutu men, Nazi contamination theories, “great replacement” theory).

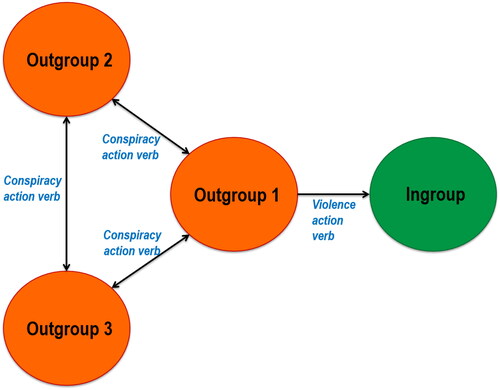

In sum, according to this second approach, extremists’ language is therefore marked by an oppressor-victim structure where the ingroup suffers from both violent attacks waged by a proximal outgroup and conspiracies carried out by more covert and distant outgroups. This victimization narrative, interlocking both violence and conspiracy, offers to audiences an explanation for their feelings of uncertainty, humiliation, and loss of tradition, while also providing clear blame attribution (while exonerating their own responsibility) and justifying retaliatory violence. illustrates the use of language predicted by the existential threat model (note that the figure only contains 3 outgroups for the sake of visibility—the number of outgroups obviously varies across cases). The key linguistic features are the verbs used to characterize the outgroups’ actions, and more precisely action verbs belonging to both the violence (e.g. “rape,” “torture,” “kill,” “attack”) and the conspiracy (e.g. “plot,” “influence,” “manipulate,” “deceive”) lexical fields. This model also opens up the possibility that several outgroups co-exist, each with distinct typical actions.

Such an approach assumes that the key mechanism of radicalization at play with violent extremist communication is language’s ability to create both at once a multidimensional sense of acute victimization and an illusion of total understanding, building on audiences’ fear and resentment to trigger absolute protection needs as well as a desire for revenge. Victimization narratives connecting violence and conspiracy are of course well known to scholars of radicalization; using multiple empirical examples, Braddock for example shows that terrorist narratives are key sources of radicalization.Footnote52 To use Hafez and Mullins’ typology again,Footnote53 this process relates to the “grievance” mechanism of radicalization, whereby individuals radicalize as their hatred against those allegedly harming their group accumulate. Belief in victimhood has been shown to have detrimental effects on intergroup relations, especially when it is understood in exclusive or competitive terms, that is, when people believe that their ingroup is the only one to suffer (exclusive) or suffers far more than other groups (competitive). Collective victimhood beliefs play a key role in fueling intractable conflict,Footnote54 predict negative intergroup attitudes in post-conflict settings,Footnote55 and predict hostile intergroup engagement.Footnote56 Language that encourages ingroup victimhood perceptions also place the ingroup on a moral pedestal, which both “provides moral power to oppose the enemy and seek justice” and offers “a licence to commit immoral and illegitimate acts.”Footnote57 Relentless claims that an outgroup harms the ingroup through direct violence and indirect cabals is therefore fueling well-known drivers of intergroup conflict.

An Integrated Lexical Model of extremists’ Language

The contrast between the two main approaches partly owes to our simplified presentation; indeed, authors from each approach often allude to dynamics pertaining to the other, alternative model. On the social identity side Reicher and colleagues for instance clearly stress that the outgroup is often portrayed not only as negative but also as threatening the ingroup,Footnote58 and Donohue’s “identity trap” explains how “affiliation messages” combine with “messages that emphasize power.”Footnote59 On the other side, Oliver and Wood directly linked conspiracy theories with Manichean narratives, explaining that the former reinforces beliefs in binary “melodramatic narratives […] that interpret history relative to universal struggles between good and evil.”Footnote60 This insight is illustrated in Herf’s analysis of Nazi propaganda which showed how its paranoid conspiracy theory reinforced a Manichean perception of the world.Footnote61 It remains, however, that the two models are largely distinct in what they consider to be the key markers of violent extremists’ language and, therefore, which radicalization mechanisms chiefly operate when this language is used. We therefore argue that a comprehensive and empirically accurate model of extremist language should not only merge these two approaches, but also add and refine a series of elements; the following paragraphs explain such an integrated model.

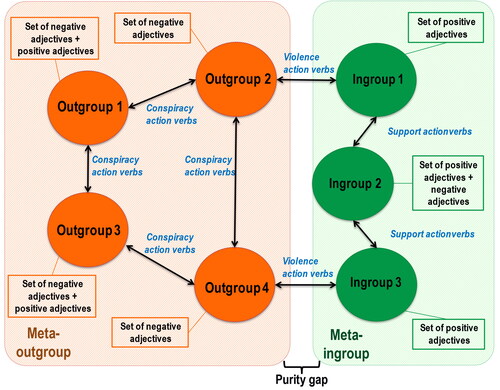

The key features of both models are kept and merged: a plurality of outgroups, each characterized by a specific set of negative adjectives, coexist and harm the ingroup. Some outgroups violently attack the ingroup whilst others conspire in the background to oppress and eventually eradicate it; violent outgroups’ behavior is supported—if not dictated—by the more distant plotters. This plurality is actually not incompatible with the binary approach adopted by the first model: we suggest that all these outgroups are collectively construed by the ingroup as a single “meta-outgroup” against which the positive identity of the ingroup is constructed. Merging the two models into a single structure allows for a clearer visualization of the interplay between their respective logics: it more clearly shows that existential threat narratives are all the more powerful when anchored into negative and dehumanizing descriptions of the outgroups (as the nouns and adjectives set up the context for interpreting the verbs) and, reversely, claims about the outgroups’ violent and conspiring behaviors further accentuate their characterization through negative adjectives (the verbs not only reinforce the negative description of adjectives but also legitimize this description as valid). The same interplay between the roles of adjectives and noun labels and verbs is true for the positive descriptions of the ingroup and narratives about its “solution” actions. In other words, the combined powers of existential threat narratives and derogatory or dehumanizing characterizations cannot be understood in isolation: it is this cumulative effect that dangerously brings together the two mechanisms of radicalization highlighted above.

We add the four following features. First, similarly to outgroups’ plurality, violent extremists’ language usually distinguishes several ingroups despite the ingroup’s proclaimed unity, for example along gender lines. Each of these subgroups of the meta-ingroup is not only differently characterized, they are also claimed to be differently targeted by the outgroups. Both Salafi-jihadist and Far-right propaganda, for example, depict ingroup women and men very differently, stressing their distinct natures and roles (e.g. women as weak, caring, and most happy at home), and differentiating the harms they suffer (e.g. women as victims of rape, men wounded or killed on the battlefield or in protests). Extremists also tend to differentiate an elite subgroup fighting for a broader, more ignorant or uncommitted ingroup (e.g. the Nazi party and the SS for Aryan people, “Knights Templars” for White Europeans in Breivik’s manifesto, etc.).

Second, these two approaches neglect how violent extremists advocate for a response to the perceived crisis, in other words they do not fully explain violence toward some of the outgroups. While several scholars of extremist communications have emphasized the importance of claims that the ingroup—or at least its vanguard subgroup—is actively and effectively reacting against outgroups’ scheming and violence, we argue that the type and intensity of solutions advocated by a group are what distinguishes violent extremists from nonviolent extremists (and ultimately prejudiced intergroup language). Ingram’s analysis of ISIS propaganda, for example, showed how its attribution of blame to outgroups for their role in a “crisis” comes with the assertion that the “solution” can only be provided by the ingroup who is resolutely delivering it through what is presented as the only remaining tactic given the severity of the situation: violence against the outgroup, and support for the ingroup.Footnote62 Solution narratives often correspond to crisis depictions by providing a method to regain certainty, reinforce tradition, and cohesion for the ingroup. The focus on extremist solution narratives thus ought to consider exactly which verbs are used to characterize the ingroup’s actions toward which outgroups, attuning to differences between nonviolent and violent forms of opposition. These advocated solutions relate to the type of adjectives used to describe the ingroup, such as “strong” or “brave”: these are positive attributes used to depict the ingroup members who partake in the group’s designated solution, thereby adding an additional radicalization pull factor by encouraging individuals to mobilize, often through violence, through fully identifying with the positive attributes of the ingroup.

Third, extremist language regularly includes, in the portrayal of some outgroups, positive characterizations alongside the negative ones. Some outgroups, usually the most distant ones, are often presented as both at once awful yet supremely cunning, intelligent, or powerful. This paradox of simultaneous dehumanization and “superhumanization,”Footnote63 which has already been noted in the social identity scholarship—Reicher and colleagues for example note that “outgroups are often portrayed as subhuman and superhuman”—Footnote64 is in fact a necessary construct to give self-defense appeals legitimacy and to give conspiratorial narratives coherence. In Nazi propaganda, for instance, Jews were not only presented as an inferior race devoid of humanness but also all-powerful puppeteers and experts in mimicry and manipulation.Footnote65 In Qutb’s infamous essay “The America I have seen” (1951), the Islamist ideologue presents the America as “the peak of advancement and the depth of primitiveness” in an attempt to both dehumanize and superhumanize American people and the West more generally.

Fourth, the linguistic separation of the social world between a meta-ingroup and a meta-outgroup underpins among violent extremists an existential fear of the impurity—both biological and immaterial (cultural, ideological)—that would result from the mixing of the two groups. In extremist language, descriptive assertions abound that the meta-ingroup and the meta-outgroup are fundamentally distinct, together with normative claims that the ingroup works toward enforcing this separation, which we call the “purity gap.” The more obsessed by the purity gap an extremist group becomes, the more violent it becomes, as evidenced in an increasingly exclusive language containing more and more action verbs denoting themes such as eradication or cleansing. For example, over the course of its rule, the Nazi system operated a gradual dissolution of the “Mischlinge” (mixed-race) label in its ideological documents, as the category became increasingly seen as threatening and therefore massacred.Footnote66 Another clear example is the notorious ISIS magazine issue (part of our corpus below) proclaiming the extinction of the “grey zone” between Muslims and the rest. Crucially, this fear is not only directed at the outgroup whose actions deliberately seek to “contaminate” the ingroup (as for instance the alleged contamination of Muslim societies by Western value and people, in jihadist thought), but also at specific segments of the ingroup depicted as weaker and potentially complicit to this nefarious agenda. In many cases across the ideological spectrum, this weaker and suspect ingroup are women, whose sexual life is therefore policed and securitized. Hutu extremists’ Kangura magazine for instance dictated “Ten Commandments” ruling interactions between Tutsis and Hutus in 1990, forbidding sexual interactions and calling for a tighter control of Hutu womenFootnote67; the more recent “Coalfax” project similarly sought to enforce the purity gap by publishing the names and addresses of white women engaged in romantic and sexual relationships with black men.Footnote68 Lexically, this purity concern is likely to manifest itself with a more nuanced characterization of the suspect ingroup, in a mirror effect of the balanced characterization of some outgroups.

Integrating the first two theoretical approaches together with these four additional elements, we generate an integrated lexical model of extremists’ language visualized in (as for , note that the number of outgroups and ingroups is hypothetical, chosen for visibility purposes, with out-/in-groups numbers obviously varying across cases; similarly, not all possible verb arrows are represented and these connections vary across cases).

Lexically, the key linguistic features are therefore both the specific sets of adjectives and specific sets of verbs that are attached to the identified outgroups and ingroups, themselves labeled by particular nouns (which can be derogatory or dehumanizing for the outgroups or glorifying for the ingroup). Specifically, each group is attached a specific set of negative or positive adjectives constructing its identity; ingroup-to-ingroup actions are marked by support verbs, ingroup-to-outgroup and outgroup-to-ingroup actions are often marked by violence verbs, and outgroup-to-outgroup actions by conspiracy verbs. Like model 2, model 3 is relational, in the sense that it does not simply depict groups of people and their traits, but also lays bare the relationships supposedly connecting these groups into a complex network. Note how the model situates one ingroup close to the meta-outgroups, at the edge of the purity gap: it is the ingroup allegedly most susceptible of contamination (as noted above, this is regularly women). Consider as well how the more distant outgroups are characterized not only by sets of negative adjectives but also by some positive ones, constructing them as simultaneously despicable yet with (at times superhuman) qualities; conversely, the ingroup understood to be weaker and most at risk of contamination is not only described with positive adjectives but also, at times, with negative ones.

In such an approach, the two key mechanisms of radicalization subsumed by models 1 and 2 interconnect: a positive ingroup identity plays on people’s need for favorable group affiliation while the activities of negatively depicted outgroups fuel both outgroup blame and support for violent retribution. Another mechanism is added: the ingroup’s fightback against the outgroups provides hope and enthusiasm for a solution allegedly within reach.Footnote69

Methods: A Semantic Network Approach to Violent Extremists’ Language

Cases and Data

To evaluate the empirical fit of our model, we compare it to two cases (this method is akin to the deductive ideal-type methodFootnote70 and other similar approaches): ISIS’ English language magazines Dabiq and Rumiyah on the one hand, and the US National-Socialist (Nazi) Movement’s (NSM) Stormtrooper and NSM Magazine on the other hand. We do so in the spirit of George and Bennett’s concept of a “structured and focused comparison,”Footnote71 that is, a detailed examination, carried out side by side, of one specific aspect in two or more cases, organized and implemented in such a way that these cases can easily be complemented by other ones at later stages. While generalizing from small-n investigations is difficult, we argue alongside scholars like Bengtsson and Hertting that carefully selected cases studied in methods like the structured and focus comparison can be used to isolate “the same ideal-type mechanisms [that can be expected] to be applicable also in similar actor constellations in other contexts.”Footnote72

More specifically, the rationale for the selection of our two cases comes from the fact that NSM and ISIS magazines are simultaneously “most similar” and “most different” “systems” and therefore pertinent for comparative case-studies.Footnote73 On the one hand, the two corpora are very similar: both are constituted of official PDF magazines destined to online distribution,Footnote74 and both disseminate an uncompromisingly extremist ideology in a propagandist perspective (in that sense both are simultaneously “extreme cases” and “paradigmatic cases,” to take Flyvbjerg’s typology).Footnote75 Moreover, the timelines of the two corpora largely overlap. On the other hand, the two corpora have key differences: their ideologies differ widely (neo-Nazism versus Salafi-Jihadism), as do the level of violence waged by the group (extreme and genocidal violence versus intimidation and harassment tactics) and the sociopolitical contexts within which the publications emerged (Middle East versus United States, regional conflict versus peace, large organization versus small movement). As a result, NSM and ISIS magazines are strikingly comparable yet very different, which makes them ideal cases to use when examining the empirical fit of our integrated theoretical model and locate potential linguistic variations reflecting more/less violent extremism. summarizes the main descriptive statistics for these two corpora.

Table 1. Corpus descriptive statistics.

Method

To compare the two corpora with the proposed model, we deployed the following three-step process. First, following Baele, Brace, and Coan,Footnote76 we relied on our in-depth expertise on both cases to manually annotate the prominent ingroup and outgroup actors for each corpus. We examined the top 500 nouns based on their frequency, thereby constituting a list of the most common ingroup and outgroup labels for both NSM (e.g. “illegal immigrants,” “Jews,” “patriots”) and ISIS (e.g. “mujahidin,” “apostates,” “crusaders”).

Second, we developed a computer-assisted approach for parsing, analyzing, and visualizing the grammatical and lexical structure of language. Drawing on recent advances in natural language processing (NLP) and probabilistic dependency parsing,Footnote77 our approach identified the prominent units of the theoretical model: noun-adjective pairs and subject-verb-object triplets. Put simply, our computational method not only tagged the nouns, adjectives, and verbs in each of the corpora, but also identified the grammatical relationships connecting them (say, noun X is the subject of verb Y; adjective X characterizes noun Y); this extra stage means that our method is much more accurate than methods relying solely on co-occurrence statistics, which can only provide guesses on the actual grammatical structure of sentences (say, noun X might be the subject of verb Y because it precedes it). More precisely, we proceeded in two steps. The first one was to tokenize, tag, and parse each sentence in our to corpora, using a large language model called spaCy: this model (1) tokenized raw text into sentences and, within sentences, words (“tokens”), (2) tagged each token with its grammatical function, in other words “part-of-speech” (“POS”; for example, “adjective”), and (3) extracted dependency relations using the model’s probabilistic parser (e.g. this word tagged as a noun is the subject of this other word tagged as a verb). The second step was to identify all subject-verb-object (SVO) triplets (combinations of a noun subject to a verb, and the object of this verb) and adjective-noun pairs (where the nouns are either a subject or object or a verb) using a custom-built algorithm. We then counted the frequency of each SVO triplet and adjective-noun pair to see which ones constitute recurring claims and evaluate their respective importance. Full details of the procedure, including a clear description of the work pipeline with the complete algorithm and real examples to illustrate the workflow at every step, are provided in Supplementary Appendix A; access to the full code is available at an anonymous online repository, also indicated in the Supplementary appendix.

Third, and given that the theoretical approaches outlined in are relational (e.g. an outgroup threatening an ingroup), we transposed the collected triplets and pairs data into a matrix file in order to use network visualization to display and analyze patterns in linguistic features both within and between groups. This matrix table condenses all combinations of nouns and verbs, with a frequency number for each combination (for example, in the ISIS corpus “mujahidin” is 11 times the subject of “kill”). In the network graphs generated from these matrix tables,Footnote78 the “nodes” represent the words and the “edges” (the links between the nodes) represent instances where they are combined in the corpora. The thickness of an edge represents the relative frequency of a relation, and the size of the nodes depends on degree (that is, the number of connections or edges the node has to other nodes); node colors depend on POS and in-/out-group list membership: verbs are shown in blue, ingroups in green, and outgroups in orange.Footnote79 Since off-the-shelf network layout algorithms (such as ForceAtlas or Fruchterman-Reingold) created extremely messy and unreadable graphs, we manually arranged the nodes in columns to best show the relationships with as much clarity as possible as well as to allow for an easy and direct comparison with the theoretical model. Of specific interest for our comparative task are statistics of subject-verb-object triplets where the ingroup does something to the outgroup (ingroup to outgroup), which allows us to contrast the advocated “solution” by a very violent group, ISIS, to the less violent extremist group, NSM.

Results and Discussion

While a single network graph could hypothetically be constructed for each of our two cases, such a graph would hardly be readable because of the number of groups populating it and their attached adjectives and verbs. For the sake of clarity, we therefore artificially split each case’s graph into two subject-verb-object triplets networks: one visualizing triplets where outgroup nouns are subjects and ingroup nouns are objects (this graph therefore depicts the “crisis”), and the reverse one visualizing triplets where ingroup nouns are subjects and outgroup nouns are objects (here visualizing the “solution”).

For each case, we add an additional graph pruning out large sections of the network to allow for a clearer zoom-in on particularly salient in-/out-groups relationships (this is especially needed in the case of ISIS, whose much denser networks remained hard to read in spite of our efforts to adequately render them to the fixed format of a journal article); it is in these two zoomed-in graphs that we include the adjectives most frequently attached to a variety of in-/out-groups. The zoom-in graph for ISIS magazines is a section of its “solution” network (ingroups as subjects) that focuses on the theme of conflict and war, while the zoom-in network for NSM magazines is a section of its “crisis” graph (outgroup as subjects) that focuses on the ethnicity theme.

–c represent ISIS magazines, and –c represent NSM magazines. We encourage the reader to explore these graphs using the original network files available in the supporting material, using a software (e.g. GEPHI) that allows for zoom-ins, better visualization of edges, possible selection of specific connections between particular individual nodes, and additional dynamic measures.

Figure 4. ISIS triplets—(a) outgroups are subjects, (b) ingroups are subjects, (c) adapted zoom-in [from (b)].

![Figure 4. ISIS triplets—(a) outgroups are subjects, (b) ingroups are subjects, (c) adapted zoom-in [from (b)].](/cms/asset/fffb46f1-ef9b-416d-a165-509134420236/uter_a_2213963_f0004_c.jpg)

Figure 5. NSM triplets—(a) outgroup are subjects, (b) ingroups are subjects, (c) adapted zoom-in [from (a)].

![Figure 5. NSM triplets—(a) outgroup are subjects, (b) ingroups are subjects, (c) adapted zoom-in [from (a)].](/cms/asset/e708728c-1645-4d69-89c4-1f40145e940d/uter_a_2213963_f0005_c.jpg)

Overall, the empirical data from both cases very closely matches the integrated theoretical model developed above and visualized in , confirming its empirical fit; there are, however, differences between the two cases that ought to be underscored and understood.

Starting with the nouns–adjectives pairs, both groups’ languages positively construct the ingroup identity and negatively depict that of the outgroup, in line with the social identity model. Adjectives are used to homogenize each side of a sharply Manichean worldview as either extremely good or evil. For the NSM, the “nation” is for instance “white,” “strong,” “free,” or “great,” while “blacks” are “horrible” and “violent” (other prominent pairs not included in the figures include “mad”-“immigrants” or “contemptuous”-“Muslims”). For ISIS, “mujahidin” are “truthful,” “sincere” or “good,” whereas the “kuffar” (nonbeliever) is “deviant,” “weak” and “ignorant,” and the “murtaddin” (apostate) are “cow-worshipping” or “unable.”

Furthermore, the practice of giving specific sets of adjectives to particular subgroups of the broad in-/out-groups—which is an addition of our integrated model—clearly appears in the network. In NSM prose, “blacks” and “black males” are for example associated with basic instincts and violence and crime (e.g. “violent,” “dangerous,” “sexual,” “hot-heated”), which contrasts with a depiction of “Jews” as a not only a more distant and greedy enemy (“financial,” “deceptive,” “worst”) but also, in accordance to our model, one whose positive or even “superhuman” qualities are acknowledged (“top”). These specific adjectives construct highly specific group identities; with the NSM example, the characterization of black men is a textbook example of dehumanization by describing the outgroup as only guided by animalistic impulses and drives, while the depiction of Jews reinforces their stereotype of scheming and conspiring people with some specific qualities. ISIS’ construction of its various outgroups’ identities similarly varies depending on the underpinning signification of the nouns labeling them. Additionally, some of the nouns used to label outgroups are clear examples of eternalization, especially in the ISIS corpus: the likes of “Crusaders” (suggesting a continuation of a thousand years’ war between the same groups), “taghut” (an important group concept in Salafi-Jihadi thought that can be traced back to Ibn al-Wahhab in the eighteenth Century), and “Khilafah” (denoting the linkage between IS and the prophetic caliphate).

Overall, the adjectives-nouns pairs laid bare by our method confirm the social identity model’s insistence on understanding violent extremists’ language as working through very strong identity appeals, creating a metacontrast effect whereby outgroups are homogenized as extremely bad and ingroups as perfect. However, and in accordance to our claim that this model alone is not sufficient to explain violent extremism, the construction of ingroups and outgroups is quite similar in both cases in spite of ISIS and NSM’s different levels of violence. The intensification of language between more and less violent extremists is only visible when attuning to subject-verbs-objects triplets.

These subject-verb-object triplets largely correspond to the quadruple pattern emphasized in our integrated model, demonstrating its pertinence beyond both the social identity model and the existential threat one: in both cases of ISIS and NSM’s languages, (1) some outgroups are responsible for direct violence against particular ingroups, (2) other outgroups plot together to operate a distant conspiracy, (3) specific ingroups actively deliver particular segments of the solution (some by confronting the outgroups, violently if needs be) while others are attributed other occupations, and (4) the various ingroups support and back each other.

In the NSM corpus first, our method reveals a clear distinction, among outgroups, between non-whites (especially African-Americans), migrants, the political elite, and Jews, in terms of what they allegedly do. “Black males” for example, are said to “rape”-“white woman,” “negroes” are claimed to “murder”-“white men,” and “foreign nationals”-“murder”-“white men.” Immigrants are predominantly depicted as flooding the nation; “immigrant”-“enter”-“nation,” and “illegal alien”-“enter”-“nation,” are prominent triplets. Elite politicians have a more systemic and distant action, they “dictate,” they “lull.” They are also active in conspiring together (this can be seen in SVO triplets where both the subject and the object are outgroups), with Jewish maneuvering particularly prominent; for example “Jews”-“get”-“president,” “Israel”-“order”-“government,” “ZOG”-“control”-“government.”Footnote80 Reacting to this state of affairs, the NSM confronts its enemy and organizes solidarity within the threatened ingroup. For example, we see that the “national socialist movement”-“stop” both “non-whites” and “illegal immigrants,” that “national-socialists”-“reject”-“establishment,” that the “nsm”-“condemns”-“antifa,” and that “white men”-“shoot”-“black men”; the “nsm”-“defends” both the “nation” and “america” while it “defends”-“our people”; the “national socialist movements” both “educates”- and “promotes”-“whites.” All these are positive actions delivering a solution to the crisis triggered by the outgroups’ actions.

Turning to the ISIS corpus, this quadruple pattern is also present, yet with some differences that offer key points of comparison and help elucidate the specific structure of violent extremist language as compared to non- (or less) violent text. ISIS’ prose depicts a world where extremely complex plots animate a deadly conflict that makes the ingroup suffer at extreme levels. Verbs belonging to the lexical field of violence are extremely frequent, much more than in NSM magazines, depicting high levels of brutality carried out by particular outgroups to specific ingroups. For instance, the “taghut”-“tyrannize”-“muslims,” “militias”-“execute”-“muhajirin,” the “coalition”-“destroys”-“khilafah,” “officer”-“torture”-“muslims,” or the “enemies”-“harm”-“mujahidin.” This outgroup-to-ingroup violence can also be more symbolic or even structural. For instance, the “kuffar”-“defame”-“believer,” the “apostates” both “insult”-“prophet” and “mock”-“messenger,” and the “munafiqin” (false Muslim) and “secularists” both “infiltrate”-“muslims.”

A dense web of outgroup–outgroup relationships indicates a thick conspiracy. Both the “sufi” and “ikhwan” outgroups are for instance said to “infect”-“factions,” “governments” allegedly both “exploit”-“al-Qaeda” and “need”-“Muslim Brotherhood,” the “Islamic front”-“congratulate”-“secularists,” and the “crusaders”-“promote”-“jews.” Yet in the ISIS corpus the separation between distant plotting outgroups and proximal violent outgroups is not as neat as for the NSM case (which more closely matched our model in that respect). Indeed a range of groups engage in both direct violence and distant plotting; “crusaders” for instance both “kill”-“muslims,” “target”-“khilafah,” “bomb”-“islamic state” or “hit”-“brother,” but also “back”-“taghut” and “back”-“factions.” This double narrative of violence and conspiracy matches theorists’ insistence on the role of victimhood and victimization discourses in violent extremist language.

Facing this extreme and overwhelming crisis, ISIS presents itself as delivering a no less extreme solution. On the one hand, the sheer quantity and diversity of verbs belonging to the lexical field of violence (“crush,” “bombard,” “encircle,” “stab,” “wound,” “injure,” “execute,” “assassinate,” “assault,” “devastate,” etc.) for which this time ingroups are subject and outgroups objects is revealing. “Mujahidin” are said to “kill,” “target,” “strike,” “fight,” “injure,” “burn,” or “terrorize” a range of enemies (the “kuffar,” “crusaders,” “nusayri soldiers,” “murtaddin,” etc.). Among the most prominent triplets in our data are linkages such as the “islamic state”-“massacre”-“enemies” or “soldiers of the khilafah”-“kill”-“murtaddin.” Overall, this clearly points to a narrative of retaliation and claimed proportionality of means between the aggression and the reaction to it, with ingroups “facing,” “warning,” “punishing,” “humiliating” the guilty outgroups. Ingroups also engage in less violent actions; for example they “destroy”-“idols,” “trick”-“secularists,” or “confront”-“sufi.” On the other hand, the various ingroups support each other. The “mujahidin”-“don’t abandon”-“brother,” the “muhajirin”-“revive”-“khilafah,” “brother”-“watch”-“sister,” and the “Islamic state”-“protect”-“muslims.” Our method’s presentation of ISIS’ insistence on its ability to provide a “solution” to the crisis confirms existing qualitative work highlighting the same propaganda theme and hence radicalization mechanism,Footnote81 and validates our suggestion that within the ingroup different subgroups are presented as carrying out different solution-related tasks (here, for example, women revive the caliphate while men fight and protect/watch them).

The difference in the level of ingroup-led violence narrated by NSM on the one hand and ISIS on the other, warrants further investigation, as it reflects the groups’ respective levels of actual violence. To study in a more directly comparative perspective the subject-verb-object triplets where the ingroup is the subject (in other words, where solution narratives are being constructed), we selected the most frequently used “solution” verbs of these triplets in the two corpora. shows the absolute frequency of the top five such verbs for ISIS together with the frequency of each ingroup subject and outgroup object associated with them. The results show that ISIS primarily advocate for raw violence, with “kill,” “target,” “fight” and “massacre” being four of their top five “solution” verbs directed at outgroups. Each of these violent solution verbs are associated with multiple ingroups and directed toward multiple outgroups, highlighting how these violent tactics are deemed appropriate by ISIS toward a broad spectrum of outgroups including the near (e.g. “murtaddin,” “mushrikin,” “kuffar,” “taghut”) and far enemies (e.g. “crusaders,” “coalition,” “christians”).

Table 2. ISIS top-5 verbs within S-V-O triplets where the ingroup is subject (and where an outgroup is object), with most frequently associated subjects and objects.

In comparison, shows the frequency for the top three “solution” verbs used by NSM. Not only are there much fewer subject-verb-object triplets where the ingroup is subject and outgroup is object across the NSM corpus (which does not only come from the smaller size of the text), but the frequency of such triplets is also very low (each of these used twice across the magazines) in comparison to the ISIS results. Given the very low frequency of “solution” verbs being used by NSM, these subject-verb-object triplets are associated with fewer ingroups and outgroups than the ISIS “solution” triplets. The nature of these “solution” verbs is also qualitatively distinct from ISIS, being more political in nature (i.e. “reject,” “condemn,” “stop”) and therefore quite distinctive from ISIS’ clear focus on direct violence. Looking at the previous , a violent “solution” verb does appear (“shoot” directed toward “black men”), but this was only used once in the NSM corpus. It is also worth looking back at , which shows the “crisis” subject-verb-object triplets, where the outgroups are the subject and the ingroup is the object: the largest, most frequently used “crisis” verb shown here is “murder” with connections suggesting the group promulgates “black men” and “foreign nationals” murdering “white men” and “Americans.” Overall, this suggests that while the NSM—like ISIS—does highlight the violence of the “crisis,” contrarily to ISIS the group does not build clear and insisting “solution” narrative, let alone a violent one. This action-oriented insistence on a (violent) solution is, we therefore suggest, a key marker of violent extremists’ language compared to less violent hate speech.

Table 3. NSM top-3 verbs within S-V-O triplets where the ingroup is subject (and where an outgroup is object), with most frequently associated subjects and objects.

In sum, all these results and findings largely match our ideal-typical model of violent extremist language, demonstrating its empirical validity and theoretical pertinence. The empirical evidence generated by the syntactic parsing of prominent nouns-adjective pairs and subject-verb-object triplets from ISIS and NSM magazines indeed corresponds with the theoretical framework developed to coalesce and further consolidate the social identity model and the existential threat one. But comparing the two cases against the backdrop of the model also allows for the identification of meaningful variations that are indicative of groups’ preferred narratives and endorsement of violence, and therefore the more specific pathways of radicalization likely to be provoked by propaganda. The comparison of “solution” triplets between NSM and ISIS, for instance, showed that distinctions exist between these two groups when it comes to the frequency of verbs supporting a solution narrative generally, and the verbs denoting violence more specifically, which not only reflects the differing degree of violence perpetrated by these two groups but also their differing choices when it comes to the type of message chosen to be delivered to their audiences in order to radicalize them. These similarities and differences confirm the pertinence of theories of radicalization that acknowledge both persistent mechanisms and variation across casesFootnote82 instead of a single set of universal drivers.

Conclusions

In this article, we aimed to construct a coherent theoretical model of violent extremists’ language, which integrates and refines the two major existing approaches into a comprehensive account of the lexical content and structure of such language. While scholars have already highlighted many of the features contained in our model, connecting them all together in a single framework had not yet been done and allowed to clarify how they interact in a cumulative radicalizing way. Using Natural Language Processing to identify nouns-adjectives pairs and subject-verb-object triplets in the magazines of two ideologically different extremist groups with varying levels of violent commitment (ISIS and US National-Socialist Movement), we demonstrated the high empirical accuracy of this integrated model and discussed differences between the two cases.

Our findings showed similarities in ingroups versus outgroups depictions and attributions, how outgroups’ actions directed at the ingroup construct a violent “crisis” narrative of victimization, and how interactions between outgroups deepen the crisis by adding a deeper conspiratorial layer. Additionally, our findings contribute to the literature highlighting the importance of “solution” narratives (here subject-verb-object triplets) in extremist language, with our results showing that the level of violence waged by a group is reflected by the saliency of violent solution verbs in that group’s language. The major similarities and smaller deviations between the two cases investigated in this study support the argument that extremist groups’ uses of language differ only in degree, not in kind, with common features present across cases with varying intensity. This is not to say that this “violent language” is the only driver of violence, as indeed a range of social contextual factors play a role in shaping sometimes very different forms of violent action,Footnote83 but that every instance of political violence is backed by this common language and can thus be analyzed through the lenses of our model. Again, while some of these insights were already present in the literature, the merits of our contribution are to integrate them all into a coherent model, to offer a rigorous, systematic, quantitative method for testing them, and to deploy this method to provide objective and rigorous evidence.

Despite its strengths, our article nonetheless has four main limitations which call for further research. First, while our empirical results match and thus largely validate our theoretical model, our focus on two cases evidently calls for more effort not only to assess the integrated model, but also to further investigate in a more systematic way the differences and similarities between different types of groups (levels of violence, ideologies, etc.). To this end, we provided as much detail as possible on our method to ensure its portability beyond the two cases investigated here.

Second, our attention to text left two major issues unexplored. On the one hand, the link between language and violence needs to be further unpacked, especially how exactly violent “solution” narratives relate to aggression or enhanced recruitment/mobilization capabilities, or how different variants of the “crisis” (subject-verb-object triplets where the outgroup is the subject and the ingroup the object) may translate to different levels of violence. On the other hand, the relationship between the kind of lexical structure of text described here and the increasingly important visual dimension of extremist outreach ought to be better understood. Multimodal approaches start to appear in propaganda research and extremism studies,Footnote84 but these efforts remain imperfect and unsystematic. A similar model and method than the one proposed here, but focusing on images, would be most welcome, especially now that computational methods for visual analysis become more commonplace and effective.

Third, the reliance of our NLP method on stemmed forms of words (e.g. “kill” for “kills,” “killed,” etc.) and its ignorance of verbs tenses (past, present, future) as well as conditionals, possibilities and imperatives expressed by secondary verbs (e.g. “may kill,” “could kill,” “should kill”), makes it blind to potentially relevant linguistic nuances. Future research could find ways to assess whether particular verbs are describing actions in the past or advocating for such action in the future, and how such differentiation may differ across extremist groups responsible for varying levels of violence.

Finally, our dependence on evident in- and out-group labels and concomitant exclusion of words that could potentially label both sides means that our analysis misses one dimension of language already identified as important in the literature: pronouns. Exploring our corpus in a qualitative way before applying our quantitative method, we indeed found that the use of pronouns is less self-evident than intuitively thought; the pronoun “they” (with “them”), for instance, regularly stood for ingroups, not outgroups. Our omission of pronouns because of this difficulty means that research is needed to integrate our model with classic accounts of pronouns’ role in sociolinguisticsFootnote85 and more recent attempts to connect them to the social psychology of intergroup processes.Footnote86

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (230.7 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For example UNODC, The Use of the Internet for Terrorist Purposes (New York: United Nations, 2012); Maura Conway, “Determining the Role of the Internet in Violent Extremism and Terrorism: Six Suggestions for Progressing Research,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 40, no.1 (2017): 77–98; Gary LaFree, “Terrorism and the Internet,” Criminology & Public Policy 16, no.1 (2017): 93–98.

2 For example Manuel Torres Soriano, “The Vulnerabilities of Online Terrorism,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 35, no.4 (2012): 263–277.

3 J.M. Berger, “The Dangerous Spread of Extremist Manifestos,” The Atlantic, 26 February 2019, available at https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/02/christopher-hasson-was-inspired-breivik-manifesto/583567/.

4 On the manosphere, see for example Horta Ribeiro M., Blackburn J., Bradlyn B., De Cristofaro E., Stringhini G., Long S.,Greenberg S., Zannettou S., “The Evolution of the Manosphere Across the Web,” 15th International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (AAAI 2021); on far-right platforms, see for example Manuela Caiani and Laura Parenti, European and American Extreme Right Groups and the Internet (New York: Routledge, 2016).

5 For example, Weeda Mehran, Stephen Herron, Ben Miller, Anthony Lemieux, and Maura Conway, “Two Sides of the Same Coin? A Largescale Comparative Analysis of Extreme Right and Jihadi Online Text(s),” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 2022, online before print; also Joshua Roose and Joana Cook, “Supreme Men, Subjected Women: Gender Inequality and Violence in Jihadist, Far Right and Male Supremacist Ideologies,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 2022, online before print.

6 Anne Maass, Daniela Salvi, Luciano Arcuri, Gun Semin, “Language Use in Intergroup Contexts: The Linguistic Intergroup Bias,” Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 57 (1989): 981–993.

7 Stephen Reicher, Nick Hopkins, Mark Levine, and Rakshi Rath, “Entrepreneurs of Hate and Entrepreneurs of Solidarity: Social Identity as a Basis for Mass Communication,” International Review of the Red Cross 87, no.860 (2005): 623.

8 Stephane Baele, “Conspiratorial Narratives in Violent Political Actors’ Language,” Journal of Language & Social Psychology 38, no. 5–6 (2019): 706–734.

9 Kurt Braddock, Weaponized Words. The Strategic Role of Persuasion in Violent Radicalization and Counter-Radicalization (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

10 For example Charlie Winter, The Virtual ‘Caliphate’: Understanding Islamic State’s Propaganda Strategy (London: Quilliam, 2015); Haroro Ingram, “An Analysis of Islamic State’s Dabiq Magazine,” Australian Journal of Political Science 51, no. 3 (2016): 458–477; Dan Milton, Communication Breakdown: Unraveling the Islamic State’s Media Efforts (West Point: Combatting Terrorism Center at West Point, 2016).

11 William Donohue, Mark Hamilton, “A Framework for Understanding Polarizing Language,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language and Persuasion, eds. Jeanne Fahnestock and Randy Harris (London: Routledge, 2022): 207–223.

12 Gordon Allport, The Nature of Prejudice (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1954); Henri Tajfel, Michael Billig, R.P. Bundy and Claude Flament, “Social Categorisation and Intergroup Behaviour,” European Journal of Social Psychology 2, no.1 (1971): 149–178; Henri Tajfel, John Turner, “The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior,” in Key readings in Social Psychology. Political Psychology, eds. John Jost and Jim Sidanius (New York: Psychology Press, 2004 [1979]): 276–293.

13 Penelope Oakes, “The Root of all Evil in Intergroup Relations? Unearthing the Categorization Process,” in Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology: Intergroup Processes, eds. Rupert Brown and Samuel Gaertner (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003): 9.

14 Oakes, “The Root,” 9; also Rupert Brown, “Social Identity Theory: Past Achievements, Current Problems and Future Challenges,” European Journal of Social Psychology 30, no.6 (2000): 745–778.

15 Nick Haslam, Louis Rothschild, and Donald Ernst, “Essentialist Beliefs about Social Categories,” British Journal of Social Psychology 39 (2000): 113–127.

16 Maykel Verkyuten, “Discourses about Ethnic Group (de-)Essentialism: Oppressive and Progressive Aspects,” British Journal of Social Psychology 42 (2003): 371–391.

17 Samuel Pehrson, Rupert Brown, and Hannah Zagefka, “When Does National Identification Lead to the Rejection of Immigrants? Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Evidence for the Role of Essentialist In-group Definitions,” British Journal of Social Psychology 48 (2009): 61–76.

18 Maass, Salvi, Arcuri, and Semin, “Language Use.”

19 Donohue and Hamilton, “A Framework.”

20 Stephen Reicher and Nick Hopkins, “Psychology and the End of History: A Critique and a Proposal for the Psychology of Social Categorization,” Political Psychology 22, no. 2 (2001): 383–407; Stephen Reicher, “The Context of Social Identity: Domination, Resistance, and Change,” Political Psychology 25, no. 6 (2004): 921–945. Reicher, Hopkins, Levine, and Rath, “Entrepreneurs of Hate.”

21 Reicher and Hopkins, “Psychology and the End of History,” 390.

22 Martin Ehala, Howard Giles, and Jake Harwood, “Conceptualizing the Diversity of Intergroup Settings: The Web Model,” in Advances in Intergroup Communication, eds. Howard Giles and Anne Maass (New York: Peter Lang, 2016): 301-316.

23 Brown, “Social Identity Theory,” 750.

24 Rowan Savage, “Modern Genocidal Dehumanization: A New Model,” Patterns of Prejudice 47 (2013): 139–161.

25 For example Nick Haslam and Steve Loughnan, “Dehumanization and Infrahumanization,” Annual Review of Psychology 65 (2014): 399–423. For examples and analyses of dehumanization rhetoric in extremist language, see for example Allison Betus, Michael Jablonski, and Anthony Lemieux, “Terrorism and Intergroup Communication,” in Oxford Encyclopedia of Intergroup Communication, eds. Howard Giles and Jake Harwood (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018): 405-420; or Michael Waltman and Ashely Mattheis, “Understanding Hate Speech,” in Oxford Encyclopedia of Intergroup Communication, eds. Howard Giles and Jake Harwood (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018): 461–483.

26 William Donohue, “The Identity Trap: The Language of Genocide,” Journal of Language & Social Psychology 31 (2012): 13–29.

27 For example Elizabeth Baisley, “Genocide and Constructions of Hutu and Tutsi in Radio Propaganda,” Race & Class 55 (2014): 38–59.

28 Brittnea Roozen and Hillary Shulman, “Tuning in to the RTLM: Tracking the Evolution of Language Alongside the Rwandan Genocide Using Social Identity Theory,” Journal of Language & Social Psychology 33 (2014): 165–182.

29 For example Diane Kohl, “The Presentation of ‘Self’ and ‘Other’ in Nazi Propaganda,” Psychology & Society 4 (2011): 7–26.

30 Gilbert Ramsay, “Dehumanization in Religious and Sectarian Violence: The Case of Islamic State,” Global Discourse 6 (2016): 561–578.

31 Tage Rai, Piercarlo Valdesolo, and Jesse Graham, “Dehumanization Increases Instrumental Violence, But Not Moral Violence,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, no. 32 (2017): 8511–8516.

32 Mohammed Hafez and Creighton Mullins, “The Radicalization Puzzle: A Theoretical Synthesis of Empirical Approaches to Homegrown Extremism,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 38, no. 11 (2015): 958–975.

33 J.M. Berger, Extremism (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2018).

34 Baele, “Conspiratorial Narratives,” 711.

35 Alison Des Forges, Leave No One to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda (New York, NY: Human Rights Watch, 1999).

36 Omar McDoom, “The Psychology of Threat in Intergroup Conflict: Emotions, Rationality, and Opportunity in the Rwandan Genocide,” International Security 37, no. 2 (2012): 119–155; Omar McDoom, The Path to Genocide in Rwanda: Security, Opportunity, and Authority in an Ethnocratic State (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

37 For example Haroro Ingram, “An Analysis of Inspire and Dabiq: Lessons from AQAP and Islamic State’s Propaganda War,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 40, no. 5 (2017): 357–375.

38 Julia Ebner, The Rage: The Vicious Circle of Islamist and Far-Right Extremism (London: I.B. Tauris, 2017).

39 Ingram, “An Analysis of Inspire and Dabiq.”

40 Arie Kruglanski, “Blame-Placing Schemata and Attributional Research,” in Changing Conceptions of Conspiracy, eds. Carl Graumann and Serge Moscovici (New York: Springer Series in Social Psychology, 1987): 219.

41 For example Karen Douglas, Joseph Uscinski, Robbie Sutton, Aleksandra Cichocka, Turkay Nefes, Chee Sian Ang, and Farzin Deravi, “Understanding Conspiracy Theories,” Advances in Political Psychology 40, no. 1 (2019): 29.

42 Joseph Uscinski and Joseph Parent, American Conspiracy Theories (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

43 Jamie Bartlett and Carl Miller, The Power of Unreason: Conspiracy Theories, Extremism and Counter-terrorism (London: Demos, 2010).

44 Cas Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule, “Conspiracy Theories,” University of Chicago Public Law & Legal Theory Working Papers 199 (2008): 9.

45 Baele, “Conspiratorial Narratives.”

46 Bartlett and Miller, The Power of Unreason, 3.

47 Des Forges, Leave No One to Tell the Story.

48 Aristotle Kallis, Nazi Propaganda and the Second World War (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005).

49 Herf concurs, stressing the “paranoid conspiracy theory” holding the many parts of the Nazi discursive puzzle together. See Jeffrey Herf, “The ‘Jewish War’: Goebbels and the Antisemitic Campaigns of the Nazi Propaganda Ministry,” Holocaust & Genocide Studies 19 (2005): 51–80.

50 Liz Fekete, “The Muslim Conspiracy Theory and the Oslo Massacre,” Race & Class 53, no. 3 (2011): 30–47.

51 Stephane Baele, Lewys Brace, and Travis Coan, “From ‘Incel’ to ‘Saint’: Analyzing the Violent Worldview Behind the 2018 Toronto Attack,” Terrorism & Political Violence 33, no. 8 (2021[2019]): 1667–1691.

52 Braddock, Weaponized Words.

53 Hafez and Mullins, “The Radicalization Puzzle.”

54 For example Dan Bar-Tal, Lily Chernyak-Hai, Noa Schori, and Ayelet Gundar, “A Sense of Self-Perceived Collective Victimhood in Intractable Conflicts,” International Review of the Red Cross 91, no. 874 (2009): 229–258.

55 Johanna Vollhardt and Rezarta Bilali, “The Role of Inclusive and Exclusive Victim Consciousness in Predicting Intergroup Attitudes: Findings from Rwanda, Burundi, and DRC,” Political Psychology 36, no. 5 (2014): 489–506.

56 JoannaVollhardt, Christopher Cohrs, Zsolt Szabo, Mikołaj Winiewski, Michelle Twali, Eliana Hadjiandreou, and Andrew Mcneill, “The Role of Comparative Victim Beliefs in Predicting Support for Hostile Versus Prosocial Intergroup Outcomes,” European Journal of Social Psychology 51 (2021): 505–524.

57 Bar-Tal et al., “A Sense of Self-Perceived Collective Victimhood,” 254–255.

58 Reicher et al., “Entrepreneurs of Hate.”

59 Donohue, “The Identity Trap.”

60 J. Eric Oliver and Thomas Wood, “Conspiracy Theories and the Paranoid Style(s) of Mass Opinion,” American Journal of Political Science 58, no. 4 (2014): 952–966.

61 Herf, “The ‘Jewish War’.”

62 Ingram, “An Analysis of Islamic State’s Dabiq Magazine.”

63 On this tension between dehumanization and “superhumanization” by extremists, read the review in Nick Haslam and Michelle Stratemeyer, “Recent Research on Dehumanization,” Current Opinion in Psychology 11 (2016): 25–29. On the prevalence, effects, and psychological sources of prejudicial superhumanization, see Adam Waytz, Kelly Hoffman, and Sophie Trawalter, “Superhumanization Bias in Whites’ Perceptions of Blacks,” Social Psychological and Personality Science 6, no. 3 (2015): 352–359.

64 Reicher et al., “Entrepreneurs of Hate.”

65 Kohl, “The Presentation,” 12.

66 Read Cornelia Essner, Isabelle Kalinowski, and Edouard Conte, “Qui Sera ‘Juif’? La Classification ‘Raciale’ Nazie des Lois de Nuremberg a la Conference de Wannsee,” Genèses 21 (1995): 4–28.

67 See Baele, “Conspiratorial Narratives,” 722-723.

68 See Stephane Baele and Lewys Brace, “Coalfax,” ExID Research Briefs 1 (2021). https://socialanalytics.ex.ac.uk/exid/post/briefing/.

69 While language provides a narrative of the group’s worldview that is often supplemented and accentuated by imagery, we do not claim that language is the only or even the most important causal factor in radicalization. Rather, we consider it to be an important factor that needs to be integrated into alternative approaches, for instance Scott Atran, “Who Becomes a Terrorist Today?” Perspectives on Terrorism 2, no. 5 (2008): 3–10; Olivier Roy, “Islamic Terrorist Radicalisation in Europe,” in European Islam, eds. Samir Amghhar, Amel Boubekeur, and Michael Emerson (Brussels: CEPS, 2007): 52–60; J.M. Berger and Jonathon Morgan, “The ISIS Twitter Census. Defining and describing the population of ISIS supporters on Twitter,” Brookings Project on US Relations with the Islamic World Analysis Paper 20 (2015); Fathali Moghaddam, “The Staircase to Terrorism: A Psychological Exploration,” American Psychologist 60, no. 2 (2005): 161–169; Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko, “Mechanisms of Political Radicalization: Pathways Toward Terrorism,” Terrorism & Political Violence 20, no. 3 (2008): 415–433; Michael King and Donald Taylor, “The Radicalization of Homegrown Jihadists: A Review of Theoretical Models and Social Psychological Evidence,” Terrorism & Political Violence 23, no. 4 (2011): 602–622.

70 Arnold Rose, “A Deductive Ideal-type Method,” American Journal of Sociology 56, no. 1 (1950): 35–42.

71 Alexander George and Andrew Bennett, Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005).

72 Bo Bengtsson and Nils Hertting, “Generalization by Mechanism: Thin Rationality and Ideal-type Analysis in Case Study Research,” Philosophy of the Social Sciences 44, no. 6 (2014): 707–732.

73 For example Theodore Meckstroth, “‘Most Different Systems’ and ‘Most Similar Systems’: A Study in the Logic of Comparative Inquiry,” Comparative Political Studies 8, no. 2 (1975): 132–157.