Abstract

Militias are violent actors, shown to be self-serving, and to consistently act as spoilers of peace. So far, research has focused on their use of instrumental violence to directly undermine peace talks. Yet, militias have alternative, more indirect ways to act as spoilers of peace. As such, we seek to explore whether militias spoil peace by preventing nonviolent resistance (NVR) events, which have previously been associated with an increased likelihood of peace deals. Specifically, we argue that pro-government militias (PGMs) deter and prevent NVR events with the threat of violence when governments offer concessions to rebel groups in efforts to maintain a profitable status quo. We extend previous panel data sources covering the African continent in the time period 1997-2014 to show evidence of these relationships. This paper contributes to research showing the negative effects of PGMs and offers policy implications for civil society in conflict zones and peace prospects.

Recent work on militias has shown that these organisations have incentives to spoil peace negotiations directlyFootnote1 and they do this to maintain the status quo in which the beneficial situation of conflict continues.Footnote2 However, little is known about the influence militias have on third-parties, and specifically nonviolent resistance (NVR) events that seek to promote peace. During the civil war in Liberia from 1999 to 2003, the pro-government militia (PGM) – the Anti-Terrorist Unit - viciously treated pro-peace protesters. In one example, on 21 March 2001, the Anti-Terrorist Unit attacked pro-peace protesters rallying at the University of Liberia.Footnote3 More than 20 protesters were detained and women were reportedly raped while being unlawfully held for several weeks by the militia. Such activity is clearly meant to deter such groups from engaging in future protest. This will have a clear impact on the emergence of peace, especially as recent research has drawn attention to the importance of NVR in promoting positive outcomes in civil war peace processes.Footnote4 However, the impact militias, especially, PGMs may have on NVR activities remains poorly understood.

Civilians and civil society actors have engaged in various NVR actions in conflict zones and arguably in very difficult and dangerous situations, also facing the threat of repression.Footnote5 In other words, in spite of the dangers, civilians have taken nonviolent action to protect themselves, challenge belligerents, influence their behaviour to stop the violence, and pressure conflict parties for peace.Footnote6 Even though militias tend to be violent, unarmed civilians confronting armed actors is certainly not a precedent. Hence, whether militias can deter NVR or not is a non-trivial question given that NVR has emerged even in the most precarious settings. Specifically, critical points in civil war peace processes (e.g. offers of concessions) can demonstrate the strikingly different incentives held by PGMs and civil society actors engaging in NVR events: PGMs seek to prolong conflict, while NVR to stop it.

In this paper, we address this puzzle by focussing on NVR events during periods of peace negotiations, specifically, at crunch points during negotiations – when public concessions are offered by the government to rebel groups (signalling a readiness for peace). We believe these announcements are most likely to attract the attention of journalists, civil society organisations, and PGMs seeking to spoil. These policy announcements represent key moments on the path toward peace and are much more easily observable than the incidence of negotiations, which may be held in secret, or in a foreign country. Nonviolent resistance events are also more likely to be focused around moments of key policy announcements.

Thus, we would expect protest to be more likely to occur at crunch points during negotiations in efforts to encourage governments to sign up to peace. However, in states such as Liberia, where PGMs are active and these groups have had ample opportunity to harass and brutally attack pro-peace protesters, we expect the incidence of protests during crunch points in negotiations to be less likely. In sum, we argue that PGMs deter nonviolent resistance demonstrations at critical points during civil war peace processes with the ever-present threat of violence underpinned by their history of human rights abuses and violence against protesters.

Militias are informal armed groups that do not form part of regular standing forces, such as the army or air force, and are typically drawn from the civilian population. However, this informality belies their organised and often hierarchical nature, which distinguishes them from spontaneous mobs of vigilantes.Footnote7 This research follows Raleigh,Footnote8 defining political militias as “armed groups using violence or the threat of violence to influence an immediate political process.” This definition differentiates militias from rebel groups who use violence to re-define a political process through secession or government overthrow. Political aims differentiate militias from criminal gangs and private security companies that are set up for the pursuit of profit. In this paper, we focus on PGMs, which are identified as politically pro-government or sponsored by the government.Footnote9 Examples include groups such as the Ulster Volunteer Force in Northern Ireland or the Janjaweed in Sudan.

We use the continent of AfricaFootnote10 to test our hypotheses and data on nonviolent resistance demonstrations from the Social Conflict Analysis Database (SCAD) covering the period 1997-2014.Footnote11 We use information from the Relational Pro-Government Militia Dataset (RPGMD) to code PGM events in the Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset (ACLED) creating a unique dataset of PGM activity in Africa.Footnote12 We also extend data on the offering of concessions coded by ThomasFootnote13 to cover the 2010-2014 period. Our analyses reveal that PGMs are found to be discouraging nonviolent resistance demonstrations at critical times in peace processes and they achieve this by increasing their violence against civilians in preventive action. To validate our conclusions, we show evidence that not all militias produce this negative effect - those not associated with the government – non-government militias (NGMs)Footnote14 – do not systematically discourage nonviolent resistance demonstrations in any way. Overall, with this research we demonstrate that specifically PGMs, not all militias, can act as deterrent to civilian-led nonviolent action but primarily in high-stake situations during peace processes, namely the offers of concessions.

The contributions of this paper are threefold: (1) to our knowledge, this is the first study to consider the deterrence effect of militias on forms of nonviolent resistance such as peaceful demonstrations during civil war; (2) the paper presents and explores a new data resource on the activity of PGMs in the continent of Africa from 1997-2014 that will have many potential applications; and (3) it extends the concessions data of ThomasFootnote15 to cover the years from 2010-2014.

This research provides key implications for civil society, governments, and international actors. Research has shown that inclusive peace processes are more likely to result in sustainable peace.Footnote16 The suppression of civil society voices by PGMs during peace processes can thus have a devastating impact on the likelihood that an agreement is signed, on violence recurrence, and on human and economic development. PGMs must be managed effectively to prevent the suppression of the public voice, and civil society organisations must be equally supported to make their voices heard in a safe and secure environment. Without this, peace processes are unlikely to receive the proper scrutiny of mass publics, broad-based participation is likely to be discouraged and the redress of grievances and popular support for peace are likely to be side-lined.

Militias and the Status Quo during Civil Wars

One of the most robust characterisations of militias is as spoilers of peace. Though we might at first think PGMs should be fully aligned with the goals and methods of the state they serve, it has been observed that the relationship between state and PGM often falls victim to typical principal-agent problems.Footnote17 An additional complication is that African states are rarely unitary and often highly fractionalised given that “the state” and related institutions are perceived as prizes to be captured. Still, in this paper we are forced to simplify the complexity of African states in order to develop our theoretical expectations. PGMs can be seen as distinct actors with their own complex internal power dynamics and organisational aims. While these groups are politically allied to the state, they do not always act in accordance with its wishes.Footnote18 Abbs, Clayton, and ThomsonFootnote19 find this may be especially true of PGMs that do not share the same ethnicity with the incumbent government. SchneckenerFootnote20 points out that non-state armed groups – including militias – spoil peace because “capable state structures would limit their room for manoeuvre and opportunities to pursue their political and/or economic agendas.” Peace also presents an existential threat, if the monopoly of the use of violence is restored. AliyevFootnote21 confirms this expectation, finding that civil conflicts involving militias are more likely to end in low-level violence than any other outcome (including military victory, peace agreement, or ceasefire). Aliyev emphasises the nature of militias as nefarious organisations, whose side-profits would be reduced by any outcome other than low-level violence. Thus, militias have clear incentives to maintain the status quo of ongoing civil conflict.

Maher and ThomsonFootnote22 outline in their exposition of the Colombian case, how paramilitaries can maintain an advantageous status quo by targeting key actors or engaging in other violence during an ongoing peace process. They also lay out mechanisms through which militias may indirectly spoil peace by taking advantage of the power shift to improve their own position once rebels have disarmed. Similarly, Steinert, Steinert and CareyFootnote23 test militias’ post-conflict spoiling using a cross-country analysis, finding significant results to support the view.

Nevertheless, more recently, Abbs, Ari and NelsonFootnote24 have found that the use of violence by militias can both spoil and promote peace through their effect on the likelihood of negotiations. The use of militias by states to combat insurgents diminishes the chances that these groups come to and stay at the negotiation table, while their use as proxies for violence against civilians backfires as it draws critical international attention, forcing governments to commit to talks. Thus, a fair amount of work has been completed detailing the impacts of militias acting as spoilers on the conflict and post-conflict environment. However, to date, no research has focussed on the impact of militias on ongoing peace processes. In this paper, we address this gap by looking at key points in the peace process – when concessions are offered by the state to rebel groups.

At the same time, the primary reason states engage PGMs during civil conflict is to act in counterinsurgency. For instance, various PGMs emerged to fight the Boko Haram insurgency and the Islamic State’s West Africa Province faction in the North-East of Nigeria.Footnote25 These forces have been crucial for the Nigerian military as they provide intelligence and support for military operations in the region. NVR events, as they threaten the status quo of state leadership, policy, and militia relations, could also be seen as a natural and legitimate target in militias’ counterinsurgent activity. Furthermore, states may use PGMs instrumentally to prevent mass protest around negotiations and the offering of concessions. Certainly, Charles Taylor of Liberia ordered the repression of NVR movements during negotiations in the late stages of the war in 2002-2003 fearing that mass protests would embarrass his administration in the eyes of the international community.Footnote26

Nonviolent Resistance as a Threat to the Status Quo

The finding that nonviolent resistance has been comparatively more successful than violent methods in achieving the stated goals of opposition movements has opened the avenue for further investigations into the effects of violent and nonviolent methods of oppositionFootnote27. Previous research on nonviolent resistance and armed conflict has primarily examined these outcomes using comparative frameworksFootnote28. Yet, a growing body of work has started to explore the dynamics and effects of nonviolent action occurring within the contexts of an ongoing violent armed conflict. For instance, AbbsFootnote29 shows that nonviolent resistance happening within civil war contexts is associated with a higher probability of peace deals between the belligerents. Relatedly, Leventoğlu and MetternichFootnote30 present evidence that rebels fighting the government are able to secure a peace agreement and concessions with the government when nonviolent resistance is present. These findings suggest that nonviolent action in civil war contexts can contribute to peaceful outcomes and the successful resolution of the dispute, directly threatening the status quo.

Far from passive victims and powerless bystanders, civilians in war zones have been able to defend themselves, overcome power asymmetries and withstand violence and control by violent armed actors.Footnote31 Abbs and PetrovaFootnote32 demonstrate that different nonviolent action tactics used by civilians and civil society actors in conflict zones can have important effects on the propensity for negotiations and on overall peace process. In particular, the authors show that protest tactics can positively influence the likelihood of negotiations. Overall, this strand of previous research suggests that civilians and civil society actors do have agency to shape government–rebel interactions, threatening the status quo via nonviolent action, but little is known about the conditions or drivers that make such civilian-led opposition more or less likely.

Militias and the Skill of Repression

Potential repression of civil society and the public voice by militias is not an activity unique to the conflict, or the negotiation environment. Militias have been used pervasively by governments as agents of repression. Mitchell, Carey, and ButlerFootnote33 present quantitative evidence which suggests militias may be well placed to prevent nonviolent resistance. In their 2014 paper, the authors examine the impact of militias on the risk of repression using data on the Physical Integrity Rights Index (CIRI) and Pro-government Militias from 1982-2007. Arguing that these groups may be used instrumentally by governments to avoid responsibility for human rights abuses during crackdowns and blaming a potential loss of control by the principal of its agents, they show that the presence of pro-government militias increases the likelihood of repression.Footnote34 Rudbeck, Mukherjee, and NelsonFootnote35 also develop an argument around the costs of repression that governments incur by repressing nonviolent dissent directly. In their paper, the authors demonstrate that states have strong incentives to use PGMs instead of the regular security forces in order to cut costs and shield themselves from possible international and domestic backlash. Carey and GonzálezFootnote36 make similar findings in their examination of post-conflict respect for human rights; though, they find the positive relationship between PGMs and repression only works through organisations that are part of the legacy of the conflict environment – new groups are not associated with reduced respect for human rights in post-conflict contexts.

Koren and MukherjeeFootnote37 specifically examine the impact of militias on nonviolent resistance campaigns, arguing that PGMs are more likely to be used instrumentally by states to repress nonviolent dissent; while, governments are more likely to rely on police and other official state forces to repress violent dissent, such as riots. This is because state forces are seen as more reliable as threat levels and stakes rise, while PGMs may follow their own priorities and fail to prevent violent overthrow of the state. In contrast to this previous research, our study examines the effect of PGMs in spoiling the prospects for peace at specific points in a civil war peace processes, namely the offering of concessions, through the deterrence of nonviolent demonstrations, rather than reactive repression.

More generally, violence used by state forces or state-affiliated forces, such as militias, has been seen as a legitimate barrier to mass mobilisation and plausibly a key impediment to the incidence of demonstration activity. HendrixFootnote38 points to the fact that violent repression tends to reduce future participation in collective action and to increase the chances of retaining the status quo. OlsonFootnote39 argued that any likely costs associated with participation in collective action would reduce the individual’s propensity to take part. And intimidation of pro-peace movements and activists has been seen in places such as Israel, where right-wing groups have sought to supress calls for compromise and peace.Footnote40 Still, some contend that repression may backfire and instead of quelling resistance, it may in fact contribute to increased levels of protest activity.Footnote41 However, these studies do not consider the idiosyncrasies associated with civil war contexts and do not factor in the role militias may play in these developments. Unlike regular security forces, PGMs, in particular, often do not strictly follow the orders of their state principal and may engage in violence without state orders.Footnote42

In summary, PGMs can be used instrumentally by states to deter dissent during delicate periods in negotiations. But beyond this, militias can be characterised as regular spoilers of peace, seeking to maintain a profitable status quo. Because of this, we expect PGMs to have clear incentives to prevent potentially destabilising NVR protests around crunch points in peace processes. Furthermore, PGMs have the skills and experience to engage in such activities, being oft used by states to repress civil society in and outside of civil conflict. Yet, beyond their trained repressive response to NVR protests, we believe PGMs will seek to discourage NVR events from occurring in the first place during crunch points in negotiations. These complex and highly organised agents are not only reactionary players in the game of national politics. For reasons previously discussed, it is in their direct interest to deter threats to the status quo (i.e. conflict). Given that NVR events can be seen as a direct threat to the status quo, and the proven efficacy of militias in supressing dissent, we expect that pro-government militias will seek to prevent protest around critical points in peace processes. Thus, we believe that the presence of PGMs will reduce the likelihood of NVR events from occurring at crunch points in negotiations.

Hypothesis 1: When concessions are offered by the government, the presence of PGMs is likely to be associated with a lower likelihood of nonviolent demonstrations than if PGMs were not present.

In order to prevent nonviolent demonstrations by the general public, PGMs are likely to use violence against civilians.Footnote43 We suggest that this is the underlying mechanism behind our theoretical expectation that given government concessions to the rebels, PGMs will be likely to hinder nonviolent demonstrations. As mentioned above, PGMs have clear incentives to spoil any prospects for peace, as they largely benefit from the ongoing conflict and associated instability. StantonFootnote44 finds that PGMs have also been associated with the deliberate targeting of civilians, but our context of examining key junctures of civil war peace processes, namely negotiations and the offer of concessions, when nonviolent action in the form of protests are most likely, makes it implausible that selective repression would take place. The violence is unlikely to be targeted as it is not always possible to pre-determine which groups are going to get out on the streets and raise their voices. The PGM’s goal in this context is to stifle any potential trouble makers. Violence against civilians should discourage mass mobilisation as it will give the impression that anyone dissenting will be targeted, shifting the balance of cost-benefit even further into the negative.

Hypothesis 2: When concessions are offered, there is a higher likelihood of PGM violence against civilians.

Research Design

Independent Variables

Militia presence at the country-in-conflict-monthFootnote45 level is coded using data on daily events in the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).Footnote46 Political militias are identified in this data set by their political goals of “influencing and impacting governance, security and policy”, while “not seeking the removal of a national power, but are typically supported, armed by, or allied with a political elite and act towards a goal defined by these elites or larger political movements.”Footnote47,Footnote48 Within ACLED, Magid and SchonFootnote49 have catalogued pro-government militias in the period 1997-2014. Thus, PGM activity can be identified by matching the names of actors from the database created by Magid and Schon. This matching reveals that 47% of identified political militia activity observed in the ACLED data set relates to PGMs. On the basis of this information we construct our first key independent variable, which is binary and captures PGM activity in a given country-month. In some of the models, we swap the PGM variable with a variable measuring the activity by political militias unaffiliated with and unsupported by the government to demonstrate further that it really is the PGMs who seek to spoil prospects for peace, not just any political militia. To this end, in those models we measure activity by “non-government militias” (NGMs) with a binary variable constructed on the basis of the matching mentioned above.

Information on government concessions is taken from Jakana Thomas’ dataset on negotiations and concessions in African civil wars (1989-2009).Footnote50 Concessions are defined as compromises offered by the government which speak directly to rebels’ demands. In other words, concessionsFootnote51 that are unrelated to rebels’ demands are not recorded as those are unlikely to translate into significant and satisfactory wins for the rebels.Footnote52 For the purposes of this paper, we extend the time period of Thomas’ dataset by following the author’s coding rules to expand the information on concessions to 2014. Concessions is a key independent variable, and it is a binary variable taking a value of one if there was at least one concession relating to rebels’ demands in a given country-month, and zero otherwise. Thus, our dataset yields 99 country-in-conflict-months with concessions. We include an interaction term of concessions and PGM, as our theoretical expectation (hypothesis 1) suggests a conditional effect of PGMs, given government concessions, on nonviolent demonstrations. We do the same in the models where we explore the effect of NGMs as a form of a placebo test.

Dependent Variables

We leverage the Social Conflict Analysis Database (SCAD) to obtain information on protest incidence, our dependent variable.Footnote53 Here we use nonviolent demonstrations and protest interchangeably and more precisely, we operationalise protest incidence in several different ways to demonstrate that the hypothesised relationships hold for protest activity over various issues. We take all peaceful action recorded in SCAD that is not in favour of government authorities, i.e. pro-government demonstrationsFootnote54 are not included in our analyses, as the inclusion of pro-government protest activity is likely to mask the effect of PGMs on protest incidence. On this basis we code our first dependent variable Protest, which is a binary variable taking a value of one if there was a protest in a given country-month and zero otherwise. We record a second binary dependent variable, Pro-peace protest, which captures only those protests that are explicitly over issues relating to domestic war, violence, and terrorism. Our third dependent variable, also binary, Protest (misc.), explores protest activity over various issues such as the economy and social issues. That is, with this operationalisation of the outcome variable, we investigate whether the effect of PGMs is different for protest activity over issues that are neither pro-government, nor pro-peace. Finally, in some of the models we use protest events from the ACLED dataset as a binary dependent variable to ensure that our findings are not driven by particularities of the SCAD dataset.Footnote55

Since both ACLED and SCAD are events’ datasets, we elaborate on the aggregation approach we took since our unit of observation is the country-in-conflict-month. While SCAD events have both a start and an end date, ACLED events are coded only on the basis of a particular date. In the SCAD dataset there are only about 16% of events that have a duration of two months, the vast majority of events are shorter in duration. Hence, we code whether in a given month, in a given country there was a protest event (for events lasting two months, we code both months). With ACLED, we record whether there was a protest event in a given country-in-conflict-month (the ACLED dataset records the date of the event and hence, we take the month of a particular event).

In order to test our proposed mechanism further, we also conduct analyses on the effect of concessions on PGM attacks on civilians respectively. If militias are responsible for the intimidation of civilians given concession announcements, this should serve as a strong indication of how militias are deterring protest. To gain information on PGM violence against civilians, we use the ACLED data set and we record events where specifically PGMs engage in attacks on civilians.Footnote56 This yields the binary dependent variable PGM attacks on civilians and with this analysis we test Hypothesis 2. We also redo this analysis by changing the dependent variable PGM attacks on civilians with the variable NGM attacks on civilians (also obtained from the ACLED data set) as a placebo test since we argue that concessions, and hence, greater prospects for peace, are likely to have an effect on PGM attacks on civilians, not on non-government political militias’ likelihood of committing violent acts in general. Hence, if concessions have an effect on PGM attacks on civilians, but not on NGM attacks on civilians, we will see this as a strong evidence in support of our theory.

Controls

In the analyses, we use a variety of control variables that might impact both the outcome of interest and key independent variables. Battle-related deaths (BRD) is taken from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program Georeferenced Event Dataset (GED).Footnote57 The log-transformed monthly count of battle-related deaths may influence the likelihood for nonviolent action as well as concessions.Footnote58 We also account for the logged values of a country’s Gross domestic product per capita (GDP p.c. (log)).Footnote59 Economic grievances could trigger protest and further instability, stalling negotiations and the possibility for concessions.Footnote60 Additionally, PGM activity could also be influenced by inadequate economic development such as decreasing wages and limited resources. A country’s regime type is captured with the Polity variable.Footnote61

Other types of contention could impact the propensity for PGM activity, the likelihood of concessions as well as the feasibility for protest action. To account for these possibilities, we control for whether or not there were any strikes and riots in a given country-month. We take information from the SCAD dataset to code the binary variable Strikes, which captures both general and limited strikes, as well as the binary variable Spontaneous riots.Footnote62 With the Time since last event variable we measure the number of months since the last protest incidence. Common support of these controls across the categories of PGM presence versus no presence and concessions versus no concessions are shown in the appendix.

Estimation

Our estimation approach is driven by the binary nature of the dependent variables we explore and consists of a series of logistic regressions with robust standard errors clustered by country to allow for within-country correlation. We apply a one-month time lag to the independent variables that are expected to vary by month to address any simultaneity concerns.

Results and Discussion

presents the findings from the quantitative analyses testing hypotheses 1 and 2. We present eight regressions with different operationalisations of the dependent variable: in models 1 and 2 the outcome variable is all protests, except pro-government protest (over a wide range of issues); in models 3 and 4 we restrict the dependent variable to pro-peace protests only (protests with explicit demands pushing for peace and the cessation of violence and the conflict overall); in models 5 and 6 we consider protests over various issues, such as elections or economic grievances, unrelated to peace; finally, in models 7 and 8 we use an alternative protest incidence dependent variable from the ACLED dataset.

Table 1. Logit regressions of protest incidence.

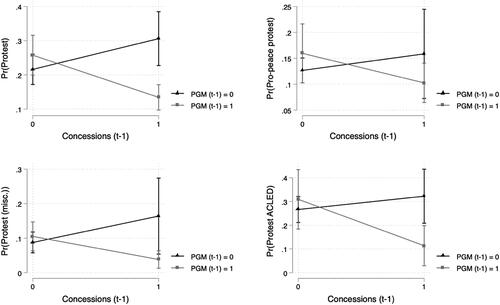

With hypothesis 1 we proposed that PGMs are more likely to discourage nonviolent demonstrations when concessions are offered in efforts that prolong the conflict. The interaction term Concessions x PGM tests this theoretical expectation. Across all models, it is negative and statistically significant and the predicted probabilities plots in depict the diminishing probability of protest given concessions and PGM activity, showing support for hypothesis 1.

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities.

Notes: The graph presents predicted probabilities of protest given PGM and Concessions. All other control variables are held at their observed values. The graph is created on the basis of Models 1, 3, 5, and 7. Computed with 95% confidence intervals.

Importantly, these correlations hold across the various operationalisations of our dependent variable, demonstrating that neither particular protest issue, nor the use of a particular dataset is driving the findings. We believe that this lends further credence to our theoretical expectation that PGMs are repressing indiscriminately when concessions are offered – the effect on protest and civil society movements is not limited to pro-peace movements, but it holds across the board.

Conversely, the interaction term Concessions x NGM does not reach statistical significance in any of the models in , suggesting that NGMs do not affect the likelihood of protest when concessions are offered. This lends support for our theoretical expectation and can be seen as evidence that PGMs, rather than NGMs, do aim to spoil peace processes. NGM groups may be aligned with opposition parties and rebel groups, or function as protectors of specific communities. For instance, the Da Nan Ambassagou militia in Mali has been a prominent force in the protection of the Dogon communities,Footnote63 while the Renamo-affiliated Mujeeba militia in Mozambique has served as a tool for rebel control.Footnote64 Such organisations are likely to have little to no incentives to discourage demonstrations around the time of concessions. Firstly, any association between anti-government protest and insurgency is extremely unlikely to lead NGMs to supress dissent, as counterinsurgency is not one of their primary functions during episodes of civil conflict.

Secondly, as mentioned in the examples above, NGMs’ key roles revolve around the protection and control of specific localities rather than counterinsurgency efforts. Particularly, pro-rebel militias will be unlikely to discourage nonviolent demonstrations when concessions are offered because they would like to maintain pressure on the state to follow through on its promises and to encourage further concessions. The lack of effect shown across models 2, 4, 6, and 8 in further lends credence these claims.

In , we seek to further investigate the underlying mechanism behind hypothesis 1 and the ways through which PGMs, around times of concessions, may discourage protest in an effort to spoil peace. Models 1 and 2 show the full sample examining the effect of concessions on PGM and NGM attack on civilians, respectively, while in models 3 and 4 we restrict the sample to cases where PGM and NGM groups were present.

Table 2. Logit regressions of PGMs attacks on civilians.

Concessions are a positive and statistically significant correlate of PGM attacks on civilians, showing support for hypothesis 2 and suggesting that such breakthroughs in the negotiation process between the government and rebels are likely to trigger violence against civilians by PGMs to ward off civilian-led initiatives that pressure for peace.Footnote65 We contend that such violence by PGMs is the tool through which PGMs dampen mobilisation and participation in nonviolent action such as protests. Looking at NGM attacks on civilians, the coefficient of the Concessions variable is negative and not statistically significant. Hence, such critical moments in the negotiations between the conflict belligerents are not associated with civilian targeting by NGMs. Results also reveal that both PGM and NGM attacks on civilians are less likely to occur the longer the time since the last attack. Country-level controls as well as the intensity of the conflict between the government and the rebels do not have a distinguishable effect on the likelihood of PGM attacks targeting civilians.

We also seek to further assess whether a specific type of PGMs are responsible for spoiling the prospects for peace. PGMs are broadly categorised as semi-official or informal groups. “A semi-official PGM has a recognised legal or semi-official status,”Footnote66 whereas informal groups have a much looser affiliation. Informal PGMs are clandestine agents of the government and they are not officially recognised by the regime.Footnote67 In our sample, about 26% of PGMs are defined as semi-official and the rest are informal PGM groups. Due to the small number of observations for semi-official PGMs we are only able to concentrate on informal PGMs for this additional analysis. To obtain information on whether PGMs are informal we use the Relational Pro-Government Militia Dataset (RPGMD).Footnote68

In , we replicate the analysis presented in , but with the inclusion of only informal PGM presence as a key explanatory variable, instead of all PGMs.

Table 3. Logit regressions of protest incidence.

Here, we find a consistently statistically significant negative interaction term between concessions and informal PGMs. This suggests that it is likely the informal PGMs spoiling and preventing civilian-led action to pressure for peace. Informal PGMs have strong incentives to discourage any form of pressure on the conflict parties to resolve the conflict as in the absence of conflict, their role should wane or become obsolete. Hence, such informal PGMs are likely to obstruct mobilisation and participation in protest action in an effort to spoil peace and keep the conflict ongoing. While we cannot directly test the effect of semi-official PGMs, in a similar manner as informal PGMs, we present evidence that namely informal PGMs tend to be spoilers of peace. More formalised groups are much less prevalent and should be less likely to engage in such activity, as the state is likely to have more control over them and to discourage any potential for spoiling. Yet, we leave to future research to determine whether semi-official PGMs produce similar effects to informal PGM groups or not, as data unavailability on semi-official PGMs obstruct us to do so. All in all, we contend that the persistent negative effect of PGM groups, especially informal PGMs, is a strong signal that PGMs deter protest action in order to break negotiations and keep the conflict ongoing.

Robustness Checks

In order to further examine the above findings, we conducted a series of additional analyses that are presented in the appendix. These include fixed effects regressions and further examination of the mechanism. Results presented in Tables A2–A4 of the appendix show that the findings presented in the primary models of – models 1 and 2 – remain the same under the condition of country-fixed effects, country-year fixed effects, and country-month fixed effects with the interaction of concessions and PGM presence remaining significant at the five percent level. In the appendix we also replicated the analysis presented in , but we do not include any control variables (see Table A5). The findings hold, which suggests that they are not driven by the inclusion of controls.

In , we examine the likelihood of militia violence against civilians given the offering of concessions by the government. We believe it is also interesting to see whether militia violence against civilians increases in intensity when concessions are offered. To test this, the dependent variable of militia violence against civilians is replaced with a count of militia violence against civilian events. Results presented in the appendix suggest this is the case for PGMs with a result significant at the ten percent level. Again, there are no significant findings for NGMs.

Our key theoretical proposition states that when concessions are offered by the government, the presence of PGMs is likely to be associated with a lower likelihood of nonviolent demonstrations. Hence, we seek to explore whether this is the case also in terms of the number of nonviolent protest events in Table A7. Overall, the results closely resemble those presented in the main article with the notable exception of pro-peace protests. The intensity of pro-peace protests seems to be unaffected by PGM activity around the time of government concessions to rebel groups. This points to the conclusion that if PGMs are unsuccessful in deterring pro-peace protest in the first place, then they are unlikely to play a decisive role in the intensity of pro-peace protest action.

Finally, in Tables A8 and A9 we redo the regressions presented in and include additional controls to check whether our main finding holds. In particular, we seek to capture the repressive environment with an index on physical violence and an index on freedom of association taken from the Varieties of Democracy (VDEM) dataset.Footnote69 The former represents respect for physical integrity rights, while the latter captures the extent to which parties and civil society organisations are allowed to exist and operate. More repressive contexts are likely to see more militia activity and to dissuade collective mobilisation such as protests. We also include a variable measuring a country’s population size as more populous countries should have more potential participants in protests. With the variable state fiscal capacity from the VDEM dataset we seek to control for states’ strength as weaker states are likely to see more militia activity.Footnote70 Even with the inclusion of these variables, our main finding holds - when concessions are offered by the government, the presence of PGMs is likely to be associated with a lower likelihood of nonviolent demonstrations than if PGMs were not present.

Conclusions

The barriers to nonviolent mobilisation, especially in civil war contexts, are certainly numerous. Yet, in spite of the dangers, civilians have taken nonviolent action to protect themselves, challenge belligerents, influence their behaviour to stop the violence, and pressure conflict parties for peace.Footnote71 In this paper we show that PGMs are likely to be deterring protest action at key points in civil war peace processes, namely when concessions are offered by the state to rebel groups. Specifically, we present evidence which suggests that informal PGMs are likely the ones preventing peaceful demonstrations by civilians and civil society actors in attempts to spoil peace and maintain a preferential status quo. PGMs are often viewed as spoilers of peace, and we agree with this characterisation. Our findings lend further support for it, specifically by uncovering a previously unexplored process through which PGMs negatively affect the chances for peaceful resolution of violent armed conflict. In particular, we show that PGMs tend to discourage protest action when concessions are offered to rebels by using violence against civilians, raising the costs to protest and placing a barrier to collective mobilisation to pressure for peace. While the data used in this paper are limited to the African continent only, we suspect that similar effects can be found elsewhere given that PGMs are agents used widely throughout the world. We leave it to future research to explore these associations beyond the African context as currently data availability limits us to do so.

In an effort to offer a more nuanced understanding of militias’ effects on conflict resolution developments, we also explore the role of NGMs. Our results from large-N analyses point to no substantial effect of NGMs on the likelihood of protest activity, which is another indication that PGMs are likely the key, albeit indirect, spoilers of peace via the suppression of protest activity.

This research uncovers a new path through which PGMs subvert the chances for sustainable peace and development. The prevention of inclusive peace processes through the suppression of civil society has wide-reaching detrimental effects. Hence, our findings have important implications for civil society, governments and the international community. If governments utilising PGMs, especially informal PGMs, are unable to control their agents, PGMs’ incentives to spoil peace can remain unabated. While the use of PGMs as a counterinsurgency tool by governments is instrumental in warding off armed actors, the threat to civil society participation in collective action, specifically in an effort to pressure for peace, is a critical sign that PGMs can be a double-edged sword. Civilians and civil society actors need to be wary of the ways through which PGMs might undermine their intentions to engage in collective nonviolent action such as protests. Just because their voices cannot be heard on the streets, does not mean they have nothing they would like to say. International actors must be cognisant of the impact PGMs have on civil society during peace processes. Where PGMs are present they must redouble their efforts to ensure safe spaces for civil society actors to guarantee opportunities for bridging divides and engagement in bridging activities such as collective demonstrations in support for peace.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (575.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Suramya Srivastava for her work as research assistant to code government concessions to rebel groups in Africa from 2010-2014. Our thanks go to attendees of the Network of European Peace Scientists Annual Conference in 2021, and the Conflict Research Society Annual Conference of the same year. We would also like to thank Luke Abbs for feedback on a pre-submission draft of this article. Finally, we would like to show our gratitude to the Editor and anonymous Reviewers for helping us to improve this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 David Maher and Andrew Thomson, “A Precarious Peace? The Threat of Paramilitary Violence to the Peace Process in Colombia,” Third World Quarterly 39, no. 11 (November 2018): 2142–72; Christoph V Steinert, Janina I. Steinert, and Sabine C. Carey, “Spoilers of Peace: Pro-Government Militias as Risk Factors for Conflict Recurrence,” Journal of Peace Research 56, no. 2 (March 2019): 249–63; Huseyn Aliyev, “‘No Peace, No War’ Proponents? How pro-Regime Militias Affect Civil War Termination and Outcomes,” Cooperation and Conflict 54, no. 1 (March 2019): 64–82.

2 Aliyev, “‘No Peace, No War’ Proponents?”

3 Amnesty International, “Liberia: Students Raped by Government Security Forces,” July 31, 2001, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr34/013/2001/en/.

4 Luke Abbs, The Impact of Nonviolent Resistance on the Peaceful Transformation of Civil War (Washington, DC: ICNC Press, 2021); Luke Abbs and Marina G. Petrova, “The Quest for Peace: Analysing the Effects of Nonviolent Action on Civil War Peace Processes,” Working Paper, (2021).

5 Cécile Mouly, María Belén Garrido, and Annette Idler, “How Peace Takes Shape Locally: The Experience of Civil Resistance in Samaniego, Colombia,” Peace & Change 41, no. 2 (2016), 129–66; Juan Masullo, “The Power of Staying Put Nonviolent Resistance Against Armed Groups in Colombia,” (2015), https://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/The-Power-of-Staying-Put.pdf; Oliver Kaplan, “Nudging Armed Groups: How Civilians Transmit Norms of Protection,” Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 2, no. 3 (2013), 1–18; Oliver Kaplan, Resisting War: How Communities Protect Themselves (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

6 Kaplan, Resisting War; Abbs and Petrova, “The Quest for Peace.”

7 Sabine C. Carey, Neil J. Mitchell, and Will Lowe, “States, the Security Sector, and the Monopoly of Violence,” Journal of Peace Research 50, no. 2 (March 2013), 249–58.

8 “Pragmatic and Promiscuous: Explaining the Rise of Competitive Political Militias across Africa,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 60, no. 2 (2016), 289.

9 Carey, Mitchell, and Lowe, “States, the Security Sector, and the Monopoly of Violence.”

10 We limit our analysis to the continent of Africa only due to limited data availability. We hope that future data collection efforts will enable us to expand the analysis of this important topic.

11 Idean Salehyan et al., “Social Conflict in Africa: A New Database,” International Interactions 38, no. 4 (2012), 503–11.

12 Clionadh Raleigh et al., “Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset,” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010), 651–60; Yehuda Magid and Justin Schon, “Introducing the African Relational Pro-Government Militia Dataset (RPGMD),” International Interactions 44, no. 4 (July 2018), 801–32.

13 Jakana Thomas. “Rewarding Bad Behavior: How Governments Respond to Terrorism in Civil War.” American Journal of Political Science 58, no. 4 (2014), 804–18.

14 Non-government militias (NGMs), as organisations, which may be loyal to opposition parties, local communities, or even rebel groups, are not likely to discourage protests during critical points in peace processes because it is directly in their favour to allow them to proceed. This is because NGMs have an incentive to create and contribute to gains for the opposition with the ultimate goal of pressuring the government to fulfil its commitment to promised concessions. One such example is the pro-Renamo militia Mujeeba created and used by the rebel group in the context of the Mozambique civil war to maintain control over various village communities Nelson Kasfir, Georg Frerks, and Niels Terpstra, “Introduction: Armed Groups and Multi-Layered Governance,” Civil Wars 19, no. 3 (2017), 257–78.

15 Thomas, “Rewarding Bad Behavior.”

16 Desirée Nilsson, “Anchoring the Peace: Civil Society Actors in Peace Accords and Durable Peace,” International Interactions 38, no. 2 (2012), 243–66.

17 Neil J. Mitchell, Sabine C. Carey, and Christopher K. Butler, “The Impact of Pro-Government Militias on Human Rights Violations,” International Interactions 40, no. 5 (2014), 812–36.

18 Corinna Jentzsch, Stathis N. Kalyvas, and Livia Isabella Schubiger, “Militias in Civil Wars,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59, no. 5 (August 2015), 755–69; Paul Staniland, “Militias, Ideology, and the State,” ed. Corinna Jentzsch, Stathis N. Kalyvas, and Livia Isabella Schubiger, Journal of Conflict Resolution 59, no. 5 (August 2015), 770–93.

19 Luke Abbs, Govinda Clayton, and Andrew Thomson, “The Ties That Bind: Ethnicity, Pro-Government Militia, and the Dynamics of Violence in Civil War,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64, no. 5 (2020), 903–32.

20 Ulrich Schneckener, “Dealing with Armed Non-State Actors in Peace- and State-Building, Types and Strategies,” in Transnational Terrorism, Organized Crime and Peace-Building, ed. Wolfgang Benedek et al. (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2010), 237.

21 Aliyev, “‘No Peace, No War’ Proponents?”

22 Maher and Thomson, “A Precarious Peace?”

23 Steinert, Steinert, and Carey, “Spoilers of Peace.”

24 Luke Abbs, Ari Baris, and Phillip Nelson, “Peace Negotiations and Militia Activity in African Conflicts.” Working Paper, (2021).

25 Vanda Felbab-Brown, “Militias (and Militancy) in Nigeria’s North East: Not Going Away,” Hybrid Conflict, Hybrid Peace, (2020), https://i.unu.edu/media/cpr.unu.edu/post/3895/HybridConflictNigeriaWeb.pdf.

26 Tavaana, “How the Women of Liberia Fought for Peace and Won,” (2021), https://tolerance.tavaana.org/en/content/how-women-liberia-fought-peace-and-won.

27 Maria J. Stephan and Erica Chenoweth, “Why Civil Resistance Works,” International Security 33, no. 1 (2008), 7–44; Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011).

28 David E. Cunningham, Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, Belén González, Dragana Vidović, and Peter B. White, “Words and Deeds: From Incompatibilities to Outcomes in Anti-Government Disputes.” Journal of Peace Research 54, no. 4 (2017), 468–83.; Süveyda Karakaya, “Globalization and Contentious Politics: A Comparative Analysis of Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 35, no. 4 (2018), 315–35; Charles Butcher and Isak Svensson, “Manufacturing Dissent Modernization and the Onset of Major Nonviolent Resistance Campaigns.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 60, no. 2 (2016), 311–39; Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham, “Understanding Strategic Choice: The Determinants of Civil War and Nonviolent Campaign in Self-Determination Disputes.” Journal of Peace Research 50, no. 3 (2013), 291–304.

29 Abbs, The Impact of Nonviolent Resistance on the Peaceful Transformation of Civil War.

30 Bahar Leventoğlu and Nils W. Metternich, “Born Weak, Growing Strong: Anti-Government Protests as a Signal of Rebel Strength in the Context of Civil Wars.” American Journal of Political Science 62, no. 3 (2018), 581–96.

31 Oliver Kaplan, “Protecting Civilians in Civil War: The Institution of the ATCC in Colombia,” Journal of Peace Research 50, no. 3 (2013), 351–67; Kaplan, Resisting War: How Communities Protect Themselves; Mouly, Garrido, and Idler, “How Peace Takes Shape Locally: The Experience of Civil Resistance in Samaniego, Colombia.”

32 Abbs and Petrova, “The Quest for Peace.”

33 Mitchell, Carey, and Butler, “The Impact of Pro-Government Militias on Human Rights Violations.”

34 While we recognise the possibility that repression of nonviolent resistance by PGMs can be a delegated action by the state or an independent initiative of PGMs, we cannot theoretically or empirically address these nuances since such decision-making is likely to either be covert, or subject to misinformation.

35 Jens Rudbeck, Erica Mukherjee, and Kelly Nelson, “When Autocratic Regimes Are Cheap and Play Dirty: The Transaction Costs of Repression in South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt.” Comparative Politics 48, no. 2 (2016), 147–66.

36 Sabine C. Carey, and Belén González, “The Legacy of War: The Effect of Militias on Postwar Repression.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 38, no. 3 (2021), 247–69.

37 Ore Koren and Bumba Mukherjee, “Civil Dissent and Repression: An Agency-Centric Perspective.” Journal of Global Security Studies 6, no. 3 (September 2021).

38 Hendrix Cullen, “When and Why Are Nonviolent Protesters Killed in Africa ?” Korbel Quickfacts in Peace and Security, (2015).

39 Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965).

40 Zarrar Khuhro, “Rise of Zealots,” DAWN, 2015, https://www.dawn.com/news/1199448/rise-of-zealots.

41 Ursula Daxecker, “Dirty Hands: Government Torture and Terrorism,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61, no. 6 (2017), 1261–89; Erica Chenoweth, Evan Perkoski, and Sooyeon Kang, “State Repression and Nonviolent Resistance,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61, no. 9 (October 2017), 1950–69; Jonathan Sutton, Charles R. Butcher, and Isak Svensson, “Explaining Political Jiu-Jitsu: Institution-Building and the Outcomes of Regime Violence against Unarmed Protests,” Journal of Peace Research 51, no. 5 (2014), 559–73.

42 Jessica A, Stanton, “Regulating Militias: Governments, Militias, and Civilian Targeting in Civil War,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 59, no. 5 (2015), 899–923.

43 Unfortunately, we are unable to theorise and measure the nature of violence against civilians (i.e., discriminate versus indiscriminate).

44 Stanton, “Regulating Militias: Governments, Militias, and Civilian Targeting in Civil War.”

45 Our universe of cases consists of countries in conflict on the African continent and we follow the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) definition of armed conflict: “a contested incompatibility that concerns government and/or territory where the use of armed force between two parties, of which at least one is the government of a state, results in at least 25 battle-related deaths in one calendar year”; UCDP, “UCDP Definitions,” Uppsala Conflict Data Program, 2022.

46 Raleigh et al., “Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset.”

47 ACLED, “Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Codebook,” Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, 22 (2019).

48 Note that ACLED codes militias and rebels separately. Hence, in this analysis we are certain that we are not capturing rebel activity, but only militia activity.

49 Magid and Schon, “Introducing the African Relational Pro-Government Militia Dataset (RPGMD).”

50 Thomas, “Rewarding Bad Behavior.”

51 We also do not code different types of concessions.

52 Thomas, “Rewarding Bad Behavior.”

53 Salehyan et al., “Social Conflict in Africa: A New Database.”

54 Pro-government demonstrations refer to demonstrations in explicit support of the government.

55 Raleigh et al., “Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset.”

56 Ibid.

57 Ralph Sundberg and Erik Melander, “Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset,” Journal of Peace Research 50, no. 4 (2013), 523–32.

58 Thomas, “Rewarding Bad Behavior.”

59 World Bank, “The World Bank DataBank,” Data Bank, 2019; Michael Coppedge et al., V-Dem Methodology V10., Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, 2020.

60 Felix S Bethke and Jonathan Pinckney, “Non-Violent Resistance and the Quality of Democracy,” Conflict Management and Peace Science, (2019), 1–21; Chenoweth and Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict.

61 Monty G. Marshall and Keith Jaggers, “Polity IV Project. Codebook and Data,” Polity IV Project, 2015, http://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html; Coppedge et al., V-Dem Methodology V10.

62 Salehyan et al., “Social Conflict in Africa: A New Database.”

63 Antonin Tisseron, “Pandora’s Box. Burkina Faso, Self-Defense Militias and VDP Law in Fighting Jihadism,” Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Peace and Security, (2021).

64 Corinna Jentzsch, “Auxiliary Armed Forces and Innovations in Security Governance in Mozambique’s Civil War,” Civil Wars 19, no. 3 (2017), 325–47.

65 We cannot measure the nature of violence against civilians (indiscriminate versus discriminate) due to data limitations, but we hope that future studies will be able to replicate, measure and further clarify these associations.

66 Carey, Mitchell, and Lowe, “States, the Security Sector, and the Monopoly of Violence.”

67 Ibid.

68 Magid and Schon, “Introducing the African Relational Pro-Government Militia Dataset (RPGMD).”

69 Coppedge et al., V-Dem Methodology V10.

70 Ibid.

71 Kaplan, Resisting War; Abbs and Petrova, “The Quest for Peace.”