Abstract

Tech platforms have been through several regulatory phases concerning the countering of terrorist content on their platforms: from a lack of regulation, to the government demands of self-regulation, to the present day where regulation has been implemented across the world. Much of this regulation, however, has been heavily criticised. After consideration of these criticisms, and research into regulatory approaches in a range of other industries, this article proposes a responsive regulatory approach to countering online terrorist content. Responsive regulation argues that regulation should be responsive to specific industry structure because different structures are conducive to different degrees and forms of regulation. This article categorizes tech platforms based on different compliance issues: awareness and expertise; capacity; and willingness. It then proposes four regulatory tracks in response, in order to try to mitigate the occurrence of these compliance issues.

Tech platforms have been through several regulatory phases concerning the countering of terrorist content on their platforms: from the complete lack of regulation, to the government demands of self-regulation,Footnote1 to the present day where regulation has been implemented across the world. Much of which is continuing to inspire similar regulation in other countries.Footnote2 This article adopts Black’sFootnote3 definition of regulation as the intentional and sustained use of an authoritative party to attempt to change the behaviour of others which is done by setting specific, defined standards through the use of information-gathering and behaviour control.

Governments around the world began implementing regulationFootnote4 because platforms were not complying with the self-regulatory approach to countering online terrorist content consistently or to a level deemed sufficient.Footnote5 De Gregorio argues that a new set of legal rights has been necessary to empower users, increase transparency and accountability, and foster democratic values in the content moderation process.Footnote6 However, internet regulation is extremely complex.Footnote7 The appearance of unlawful content on tech platforms created an issue that traditional legal instruments have struggled to solve. The global and borderless nature of the internet has meant that tech platforms are arguably better placed to remove terrorist content than state actors because many of the users posting unlawful content are not able to be identified by the state or are beyond its jurisdiction.Footnote8

Much of the existing regulation has generated significant criticism, including the effect on free speech and concerns around creating unfair burdens on certain platforms that could reduce market competitiveness.Footnote9

In previous work, I identified three main compliance issues that are likely to arise when implementing regulation to counter online terrorist content on tech platforms.Footnote10 These are, tech platforms lacking the: 1) awareness and expertise required to comply; 2) capacity and resources required to comply; and 3) willingness to comply. This article argues that without sufficient consideration of these issues, regulation could unfairly penalize tech platforms (particularly smaller platforms), and could incentivize actions that will jeopardize the rights and interests that regulation seeks to protect, for example, over-blocking and infringing on free speech.

In other work, I examined a number of regulatory approaches that have been undertaken in other industries in order to investigate new approaches to the issue of countering online terrorist content.Footnote11 One regulatory approach that appeared promising was responsive regulation. This article, therefore examines these three compliance issues through a responsive regulation framework and proposes four regulatory tracks that could be taken to try to minimize these compliance issues. This will highlight that platforms are not homogeneous but rather vary in compliance issues. This is due in part, to platforms having significant differences from one another, including the number of employees they have, the size of their userbase, access to funds and resources, the missions and values that they implement in running their business, the features they offer their users, the types of content found on their services, and the challenges they face as a result of these varying factors.Footnote12

This article will discuss an overview of existing regulatory frameworks that seek to counter online terrorist content. It will then discuss a responsive regulatory approach and argue why it is appropriate for this context. Finally, this article will propose a responsive regulatory approach which involves categorizing tech platforms into a number of categories and proposing a regulatory track for each category. This includes a discussion of an educative approach to non-compliance and potential sanctions.

Overview of Existing Regulatory Frameworks

Existing regulatory frameworks have been moving in a direction where tech platforms must implement complaints procedures, appeals mechanisms and transparency reports (for example, the European Commission’s TERREGFootnote13, and NetzDGFootnote14). Whilst this can be argued as positive, there must be consideration for the expertise and resources that are required by all platforms in being able to comply with this. A move that has not been praised is increasingly strict timeframes or a lack of clarity around timeframes in which content must be removed from platforms services (for example, TERREG’s one-hour timeframe for removal). With this comes the concern that the timeframes are particularly challenging and burdensome for smaller platforms, making it difficult if not impossible to comply. Furthermore, strict timeframes have resulted in platforms having no choice but to utilise artificial intelligence technology that automatically and proactively searches for and removes content in order to comply.Footnote15 With this comes risks of over-blocking, errors and bias.Footnote16

A common criticism is the failure to provide definitional clarity of the platforms and content that is included under its scope. Without this, it is possible that platforms will not realise regulation applies to them. Platforms could also resort to over-blocking, particularly when they are unsure about what should be removed, and the enforcement actions are severe. On the other hand, platforms could also under-block because of a lack of definitional clarity, or out of fear of losing their users.Footnote17 Another criticism is that regulation is aimed solely at the major platforms, or platforms with a certain sized userbase (for example, NetzDG), missing out smaller and micro platforms which are often targeted by terrorist organisations.Footnote18 Alternatively, regulation is aimed at all tech platforms but places more demands on the major platforms (for example, the UK Online Safety Bill). Finally, regulation is aimed at all platforms but does not consider the challenges smaller platforms face with compliance.

While in some ways regulation in this area can be seen to be improving, there are still many criticisms and a lack of consideration for platforms that struggle with compliance. This article argues that a responsive regulatory approach could help to, first, categorize platforms and compliance issues, and second, propose responses that aim to minimize the challenges that platforms face with compliance.

Responsive Regulation: Understanding Compliance

Ayres and Braithwaite argue that regulation should be responsive to specific industry structure because different structures are conducive to different degrees and forms of regulation.Footnote19 They also argue that governments should be attuned to the differing motivations of regulated actors to comply with regulation because the most successful regulation will speak to the diverse objectives of the regulated firms. Responsive regulation therefore focuses on what triggers a regulatory response as well as what the regulatory response should be.Footnote20 Responsive regulation argues that for regulation to be effective, efficient, and viewed legitimately, it should take neither a solely deterrent nor solely cooperative approach.Footnote21 It proposes an approach that combines several theories of compliance and enforcement.Footnote22 Arguably, the main contribution is understanding the effects that enforcement can have and the argument that different companies have different motivations for complying or failing to comply, and that a company can have multiple, potentially conflicting, motivations regarding compliance.Footnote23

Under responsive regulation, compliance and non-compliance can be explained by a number of perspectives.Footnote24 For example, a company may be motivated financially or because of concerns for its reputation. Alternatively, compliance may occur as the result of accepting that rules must be followed or as the outcome of a learning process.Footnote25 Some companies may even comply because it is seen as a moral duty.Footnote26 Scholars have taken an approach of categorising companies based on certain characteristics, attitudes, values and resources. This allows the creation of profiles of each category of company, an assessment of the likelihood of compliance/non-compliance, and the reasons for this. For example, Kagan and Scholz created categories of companies to explain non-compliance.Footnote27 These categories include “amoral calculators” (companies who use a risk-benefit analysis to make compliance decisions); “political citizens” (companies who decide not to comply because they do not agree with the rules); and “organisationally incompetent” (companies who fail to comply due to lacking sufficient management and systems). Hawkins also categorised companies.Footnote28 These were: “socially responsible” (companies that acknowledged the importance of sorting the issue); “unfortunate companies” (who lacked the technical or financial means to comply); “reckless companies” (who openly defied compliance); and “calculating companies”; (who tried to cover up their non-compliance). Finally, HawkinsFootnote29 and BaldwinFootnote30 discuss a category referred to as “irrational non-compliers”, containing companies that refuse to comply out of malice or due to being ill-informed.

It is argued that one deterrence strategy is unlikely to be effective if the companies have different motivations to comply.Footnote31 An advantage of categorising companies is that it can be useful in making decisions about how to counter non-compliance.Footnote32 One example is that companies categorised as organisationally incompetent could be provided with user-friendly guidance manuals that tell them everything they need to know to comply.Footnote33 Whereas, this may be a waste of resources for companies who either do not require them or will not use them.Footnote34 It is argued that regulators are likely to hold a company more responsible for compliance the more it appears that it is able to comply, provide advice and encouragement when companies appear willing but unable to comply, and take a tough stance where non-compliance is intentional.Footnote35 The examples of categories that scholars have devised for companies in other industries all contain similar themes. One is that there are usually companies that lack the ability to comply, for reasons such as resources (financial, technical or other) or expertise. There are also usually companies at both ends of the spectrum: those who follow the rules (because it financially benefits them or is seen as a moral duty etc.) and companies that are unwilling to comply (also for varying reasons).

One issue, however, may be when companies fall into a grey area where it is not clear which category they belong to. It is also important to remember that assigning a company to a category is not a static process. Companies may fall into more than one category at a time or move between categories over time.Footnote36 It could also be difficult to assess the motivations of a company,Footnote37 with incorrect categorisations creating tensions between the company and the regulator.Footnote38

The Four Categories

Based on this responsive regulation framework and previous work by the author,Footnote39 this article proposes categories of tech platforms based on potential compliance issues. The first compliance issue is lacking awareness and expertise. This may be awareness of several different things. It could be lacking awareness of whether their platform is being exploited by terrorists and if so, in what ways.Footnote40 It could be lacking awareness of the need to comply with regulation. This is increasingly a problem as more countries are implementing regulation and it is a lot for companies to keep up with, as well as the earlier-mentioned issue of lack of definitional clarity meaning that they may not be aware that regulation applies to them. Finally, it could be lacking awareness of how to comply with the regulatory standards. If a platform lacks the necessary awareness to comply then this means that the platform does not have the knowledge and expertise required to undertake the actions and processes necessary to comply with regulation. Platforms require knowledge and expertise across many broad areas to comply with regulatory standards. It is important to note that terrorist groups constantly adapt and evolve,Footnote41 and because of this compliance issues are complex and on-going. A platform may find that where it once held the necessary knowledge and expertise, it suddenly requires assistance to keep up with terrorist groups ever-evolving strategies.

Tech Against Terrorism asked the tech platforms that participated in its Terrorist Content Analysis Platform (TCAP) consultation what their interest is in learning more about transparency reporting: 56.6% reported being “very interested”; 33.3% were “interested” and 11.1% were “not interested”.Footnote42 This finding that over half of the tech platforms want to further their knowledge on a common demand in recent regulation suggests that at least some platforms would welcome a regulatory track that seeks to provide this.

The second compliance issue is lacking capacity. A platform that lacks capacity is one that does not have access to the resources needed to comply. The resources that are required will differ from platform to platform depending on a number of factors, including the number of users a platform has, the volume of content it hosts, and the extent to which and in what ways the platform is exploited by terrorist groups.Footnote43 As with awareness and expertise, the position here is fluid. A platform may at one time have sufficient resources to comply with the standards, however, suddenly become targeted by a terrorist group more heavily than it had been or become exploited in a new way, and find that it no longer has sufficient resources.

Tech Against Terrorism tech platforms in their TCAP consultation how they would rate their financial and technical resources for countering terrorist exploitation.Footnote44 Only a third of the platforms that participated reported having allocated and available technical resources and less than half reported having allocated and available financial resources. This illustrates the necessity of focusing on capacity-building.

Finally, a platform could lack willingness to engage with regulation. An unwilling platform will not demonstrate reasonable efforts towards compliance. A platform may decide that it is unwilling to comply because regulation is at odds with its mission and values and could result in losing its brand identity and userbase. It may also be possible that a platform is unwilling because of laziness. This compliance issue differs to the previous two. For the previous two, platforms and regulators are, in theory, able to work together to boost compliance. With this compliance issue, however, the platforms are unlikely to voluntarily agree to work with a regulator to resolve the issue. The final category are platforms that do not face any of these compliance issues: they have the awareness and expertise, capacity and resources, and willingness to comply with the regulator.

Where a tech platform faces more than one of the compliance issues, the issue of awareness must be addressed first because you cannot gauge the other issues until the platform is aware of the regulatory demands. Willingness must be addressed next because the following compliance issues require engagement with the regulator which cannot be done without willingness. Awareness of how to comply must be addressed next to ensure that a platform fully understands the issues regarding terrorist use of their platform and how to comply. Finally, capacity would be addressed last to increase resources/make existing resources go further in order to carry out compliance. Once all compliance issues are addressed, it is proposed that the tech platform could be eligible to move to a system of (amended) enforced self-regulation (discussed below).

Educative Approach

Existing regulation in this area has focused on punishing non-compliance and been criticised as creating challenges for smaller platforms.Footnote45 Punitive approaches can result in a regulatory game of cat and mouse in which companies could be tempted to engage in creative compliance where companies may make it seem as though they are complying when they are not, or platforms may become unable to survive due to the penalties and lack of ability to overcome their compliance issues.Footnote46

An educative approach, on the other hand, is based on advice-giving and training with the enforcer playing the role of consultant, it seeks to educate and provide assistance, and exhaust these options before resorting to enforcement action.Footnote47 This approach is thought to help companies make sense of what is required of them to comply,Footnote48 help them internalise the rules and principles (Honneland, 2000), and reinforce good practice.Footnote49 However, enforcement action can be available when necessary. This may encourage companies to take the carrot because the use of a stick is a possibility.

Research by Fairman and Yapp, who interviewed representatives of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), found that most of the SMEs interviewed (n = 81) were unable to accurately judge whether they were complying because of a lack of knowledge and understanding of what was required.Footnote50 Many believed they had complied when they had not. They found that when a company did not understand what was required of them, the most common response was choosing to ignore the requirements. When investigating why companies might be happy to ignore regulation, the response was that the company was aware that severely punitive actions were only taken in extreme circumstances. Companies were therefore confident that they were not going to be severely punished. Many SMEs did not understand the risks created by their services and could not afford safety specialists. As a result, many companies were found to rely on the inspector to tell them how to comply.

This research into SMEs is important because many of the platforms exploited by terrorist organisations are SMEs.Footnote51 Although an educative approach may be resource and time-intensive, it is important to prevent the problems identified in Fairman and Yapp’s research.Footnote52 Further, compliance is a continual processFootnote53 and education is required to ensure that platforms realise this, and to ensure that platforms have access to on-going education around compliance.Footnote54 This is particularly so given that both the tech industry and terrorist organisations evolve so quickly. This is also important given that Fairman and Yapp’s research showed that many SMEs tend to view compliance as an outcome and as static. Fairman and Yapp found that where an educative approach is taken, SMEs are more likely to comply with and understand what is required of them.Footnote55 This research is supported by Braithwaite and Makkai who found that non-coercive and informal approaches are more likely to result in compliance than punitive enforcement approaches.Footnote56

Enforcement Pyramid

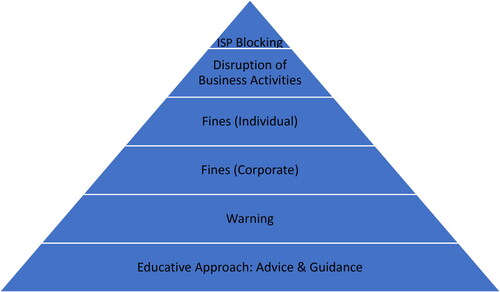

Enforcement pyramids are a tool in responsive regulation that the regulator can take to incentivize compliance. The lower levels take an educative (sometimes referred to as persuasive) approach that does not involve sanctions, however, if these levels do not work, the regulator can move up the pyramid to increasingly punitive sanctions.Footnote57 Typically, the regulator will begin at the lower levels and only when a company displays non-compliance will the regulator move up the levels. If a company chooses to cooperate, the regulator can begin to move back down the levels.Footnote58 This approach whereby the regulator responds to a company based on its behaviour is sometimes referred to as a “tit-for-tat” strategy”.Footnote59 Johnstone argued, however, that for a tit-for-tat strategy to work, the regulator must be able to identify what kind of company it is regulating.Footnote60 This is why this article has already identified four categories that a platform could be assigned to.

Overall, the aim of the pyramid is to encourage cooperation at the bottom levels of the pyramid, providing encouragement, advice and guidance, as typical of an educative approach, and become punitive only when the educative methods fail.Footnote61 The lower levels of the pyramid are more concerned with repair and results than with retribution.Footnote62 The lower levels ensure a level playing field that punishment is dependent only on willingness to comply, not ability to comply.Footnote63 Companies that are willing to comply but face issues receive help instead of sanctions. The upper levels of the pyramid are to deter companies from non-compliance. Punishment is thought to work when penalties are severe, assuming companies are rational, future-oriented and concerned with their reputation.Footnote64

Braithwaite argues that failing to comply is a less attractive option for a company when faced with a regulator armed with a range of enforcement strategies in an enforcement pyramid than a regulator who only has one option.Footnote65 Research argues that some penalties work better for some companies than others, therefore, it makes sense to have a range of penalties.Footnote66 This is the case even when the one enforcement option is very severe. In such cases companies are usually aware that the regulator cannot use the one enforcement option lightly and that they will have to do something terrible for it to be sanctioned against them. As Braithwaite points out, regulators have more power and credibility “when they can escalate deterrence in a way that is responsive to the degree of uncooperativeness of the firm, and the moral and political acceptability of the response”.Footnote67

Enforcement Pyramid Levels and Sanctions

Fines are often the go-to sanction. Although fines may be able to work as a financial deterrent, there are problems that can occur when dealing with large, profitable companies. The fine has to be very large to have an impact and make the company doubt that it is worth risking non-compliance.Footnote68 However, if it is too large then there is a risk that the fine will result in the company increasing costs; this could work as a deterrent or subsequently negatively affect consumers, and in this case the companies that advertise on the platforms.Footnote69 Where jurisdictional issues exist, enforcing a fine may not be feasible.Footnote70 The cost of the regulator trying to collect the fine may end up being greater than the value of the fine. Companies are aware of this and may intentionally fail to pay.Footnote71 On a different note, the jurisdictional problems may end up disproportionately affecting some platforms. For example, the major platforms tend to have offices based across several continents, whilst other platforms have only one base and may be able to evade enforcement more easily, creating consequences for some platforms but not others. Some unwilling platforms may be more likely to intentionally locate themselves in jurisdictions that are uncooperative. Therefore, fines alone, without the threat of more severe sanctions, may not be effective or may create issues around fairness.

displays a proposed example of an enforcement pyramid for this context. The bottom level of the pyramid starts with the educative approach, based on providing advice, guidance and encouragement.Footnote72 This level requires both the regulator and regulatee working in good faith with open lines of communication. If the platform does not appear to be engaging, then the regulator will move up one level and provide the platform with a warning and stipulate a timeframe in which it must demonstrate efforts to engage/comply, otherwise, the regulator will move up a level again. The regulator must be mindful that a platform could end up in a loop of warning – display of willingness – inaction – warning – display of willingness – inaction, as a way of evading punishment for non-compliance. There must be a restriction on the number of warnings a platform can receive before being escalated up another level. It should be noted, however, that platforms may need flexibility with the timeframes, for example, a specific action might take a major platform with a large number of employees only a few days to fix, but other platforms with a much smaller number of employees longer.Footnote73

The middle levels of the pyramid are where the sanctions begin. The two levels are comprised of different types of fines. The first type is imposed on the company. This is a common sanction used in other regulation across this industry (e.g. NetzDG, UK Online Harms Bill). The intention is to create a direct economic impact that deters companies from non-compliance. In addition to this, there is also a chance of reputational damage. In the case of tech platforms this could affect the way both advertisers and users perceive the platform, which could lead to even further economic damage.Footnote74 It is important that fines are proportionate so as not to place smaller platforms at a greater disadvantage. Bishop and Macdonald have suggested that such fines should be based on the financial strength of the company (as is done in the GDPR legislation).Footnote75 This could be up to a certain amount or it could be a percentage of the company’s total turnover in the preceding financial year.

The next level of fine is for individual members of the platform’s senior management team. This is a sanction in both the UK Online Harms Bill and Australia’s Abhorrent Violent Material Act. Such fines require members of the senior management of platforms to be identified as responsible for taking actions that ensure compliance. If the identified member of senior management fails in this duty, then the regulator can impose a fine on them as an individual. It is thought that the threat such a fine creates will get the attention of the person responsible and be a large incentive to ensure compliance because the consequences will impact them on a personal financial level.Footnote76 It would also reflect badly on the individual’s reputation, potentially hindering their future career opportunities elsewhere. However, this could make it very difficult for tech platforms to hire people in these roles, and will make it difficult for companies to comply if they are struggling to fill these positions. Further, it may be difficult to pinpoint which member of senior management should be responsible for what actions. There are again jurisdiction issues, and it can be difficult to demonstrate requirements such as neglect, especially in an industry with such complex management structures.Footnote77

The top two levels of the pyramid carry the most severe sanctions and should not be used lightly. Second from the top is disruption to business activities. This involves penalising companies that provide supporting services, in order to persuade them into withdrawing their services. An example could be removal from a search engine or app store. It is thought that platforms would not want to risk the impact this could have on their growth. This may, however, affect smaller or newer companies more than the already well-established platforms.Footnote78 There is also the example of Gab who, with effort, have overcome these issues to create their own third-party services, for example, their own browser.Footnote79

Failing this, the top level and last resort is enforcing ISP blocking. This entails the blocking of access to a platform in a country. This is likely to have a big impact on platforms of all sizes and will affect their ability to grow. This is a very serious action to take with enormous consequences for not just the platform but the users of the platform, many of whom only post lawful, non-violating content. From a human rights perspective, this action may not be deemed proportionate depending on the ratio of lawful to unlawful content on the platform.Footnote80 It could have a significant socio-economic impact and be viewed as a prior restraint on free speech which requires special justification in a liberal democracy.Footnote81 Micova and Jacques argue that before these top levels are implemented, the decision should be subject to checks around appeal, judicial review and public reporting requirements.Footnote82 There is also the limitation that users have learned technical ways to circumvent ISP blocking.Footnote83 It is important to restate the importance of the regulator exhausting the middle levels of the pyramid before enforcing the highest levels.

It is unlikely that even the most carefully designed regulation will put forth a perfect solution. It is in part due to the problem of most sanctions containing limitations. This highlights the importance of a regulator having a diverse range of sanctions at its disposal. If the regulator uses such a pyramid effectively by, (1) not moving up the levels too readily but; (2) following through with increasing the severity of the sanction when required, then it may prove to be more successful than only using one sanctioning tool.

Braithwaite insists that the harsher enforcement tools tend to be seen as more legitimate after a more persuasive style has already been attempted, and when regulation is perceived as more legitimate, the likelihood of compliance increases.Footnote84 Gunningham, Kagan and Thornton found that hearing about sanctions taken against other firms, led to companies reviewing and sometimes taking further action to ensure their own compliance.Footnote85 However, if not enforced properly, then companies who always readily comply will feel at a competitive disadvantage if they spend time, money and effort complying while other companies that do not go unpunished.Footnote86

Regulatory Tracks

The proposed regulatory tracks are designed as a response to the three compliance issues identified and a fourth track is proposed to outline the procedure that should take place when a tech platform does not face any of the identified compliance issues. The overarching goal is to provide the help, guidance and incentive that each tech platform requires in order to achieve regulatory compliance ().

Table 1. Regulatory tracks.

demonstrates the combinations of potential compliance issues faced and assigns the appropriate regulatory track(s) that must be utilised and in which order, to work towards full compliance.

Table 2. Assortment of compliance issues into the relevant regulatory track.

Regulatory Track 4: Unwillingness

This regulatory track is aimed at tech platforms that are unwilling to comply with regulation. This is the track that will most likely require the regulator to apply sanctions from the enforcement pyramid. The regulator should begin by investigating why the tech platform is unwilling to engage. Platforms may not wish to spend time, money and effort complying because they do not see it as their responsibility or platforms may have strong values that are in opposition to regulation and censorship. The latter platforms may believe that compliance would force them to change their values, brand identity or unique selling point and consequently drive away their userbase. Such platforms are only likely to engage if the regulator applies severe sanctions. Even with the enforcement of the most severe sanctions, it is likely that some platforms, will try to find creative ways around compliance (e.g. the earlier example of Gab). Sanctions could still, however, create difficulties for the platform; it can be very expensive and time-consuming for platforms to create their own third-party services, and therefore the regulator should, where necessary, apply them.

Regulatory Track 3: Lack of Awareness

This regulatory track is aimed at tech platforms that face compliance issues because of a lack of awareness, knowledge or expertise. First, the regulator must assess that a tech platform is fully aware of regulation and what is required of them. Next, it must assess that the platform understand how terrorists are exploiting their platform and to what extent this is happening. The regulator will have to assess which parts of compliance companies require help with. The effectiveness of this track relies on the regulator and tech platform working together. The role of the regulator is to take an educative approach and provide guidance, advice and encouragement.Footnote87 The role of the tech platform is to engage with the regulator’s efforts to provide knowledge and expertise, and use this knowledge and expertise to comply. Only if the tech platform begins to demonstrate a lack of engagement or willingness should the regulator begin to move up the levels of enforcement pyramid.

The regulator should provide educative training materials for tech platforms based on the demands that regulation places on them. This is likely to include areas such as terrorist use of tech platforms, creating counter-terrorism policies, best practice regarding content moderation, implementing complaints procedures, appeals mechanisms, and publishing transparency reports etc. However, some platforms may face unique issues and challenges with knowledge and expertise depending on the infrastructure of their platform and/or the ways in which terrorists exploit their platform and may need help from the regulator with overcoming these issues. This may require pointing tech platforms to collaborating and learning from various relevant NGOs, CSOs and academics.

Regulatory Track 2: Capacity

This regulatory track is aimed at tech platforms that face compliance issues because they lack the capacity and resources necessary for compliance. The regulator must assess the areas in which the tech platform requires assistance with increasing their resources and making existing resources stretch further. The regulator will focus on helping the tech platforms to build capacity in ways that do not place a financial burden on the platform. This is ambitious; however, the focus will be on other means such as sharing tools and best-practice across the industry. The effectiveness of this track relies on the regulator and tech platform working together to increase access to the required resources. This track also takes an educative approach and requires flexibility and innovation from the regulator and platforms across the industry.

The first method that can be employed by the regulator is the designing and sharing of resources across the industry. The regulator could provide a range of useful templates that can be accessed by the tech platforms, such as a transparency report template. During their consultation for the TCAP, Tech Against Terrorism found that tech companies find producing transparency reports arduous, however, expressed that it would be helpful to receive support with the process.Footnote88 The second method that the regulator can draw from is existing industry collaborations.Footnote89 Through this there can be the sharing of best practice, and the sharing of tools and technology. The tech platforms in track 1 that have designed tools, technology and other relevant resources and undertake what is considered best practice must participate in and support collaborative initiatives to increase access to resources for platforms that do not have readily available access to such resources. However, it is acknowledged that there would need to be careful consideration regarding concerns platforms may have around sharing proprietary software and how this may affect competition between the platforms.

It must be acknowledged that the involvement of relevant collaborative ventures, such as the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT)Footnote90, have come under criticism. One raised by Douek is the lack of oversight and without such oversight, it is unclear whether the GIFCT respects the rights that it claims to.Footnote91 Further, there is a lack of transparency regarding tools such as the hash sharing database.Footnote92 It is unclear what content is stored in this database or how accurate the tool is in identifying terrorist content. There is also a lack of opportunity to challenge or appeal content in the database. Another criticism has been that any bias in one platform’s tools and technology could then seep into the moderation on other platforms.Footnote93 Douek argues that such collaborations could result in allowing the major platforms “to decide standards for smaller players”.Footnote94 This removes the ability for contestation and debate that normally arises from the market-place of ideas.

Although there are these limitations, the sharing of best practice, tools and technology is particularly useful in situations of cross-platform abuse.Footnote95 Such a standardised approach may help to minimize the current whack-a-mole problem whereby terrorist groups flock to platforms that do not have the capacity to remove them. Without this sharing of tools and technology, platforms that lack capacity may believe that they must err on the side of caution and take a remove-everything approach to avoid punitive measures, infringing on freedom of speech.Footnote96 Moreover, it allows smaller platforms to avoid the failures and pitfalls that other tech platforms have experienced before them.Footnote97 Overall, without such sharing, platforms that lack capacity will be vulnerable to punitive measures and face challenges that will burden them in ways that could disadvantage them and reduce market competitiveness.

Some examples where best practice, tools and technology could be shared are how to implement appeal mechanisms and flagging mechanisms. Another example would be providing the platforms with access to the GIFCT’s hash sharing database. A final example are the tools and methods used to track and collect data for transparency reports. This example has been noted by Tech Against Terrorism that,

“Many of the smaller platforms that are exploited by terrorist groups struggle to publish transparency reports due to lack of capacity: without automated data capturing process in place, compiling and publishing a transparency report can be time and labour intensive”.Footnote98

The third method that the regulator can draw on is collaboration with academia, NGOs and CSOs. Through this there may also be opportunities to share tools and technology. Finally, the regulator could make available industry-wide resources that guide tech platforms with how to implement programmes and practices. One example is implementing a Trusted Flagger programme which provides tools for those who are highly accurate at reporting content to a platform for review.Footnote99 This takes some pressure off platform’s content moderator workloads, as well as reducing financial burdens. Trusted flaggers have been reported to accurately flag content in over 90% of cases which is three times more accurate than the average flagger.Footnote100

The purpose of this track is to help and assist platforms build their resources and capacity to comply in a way that does not place a financial burden on them. The aim is to help make existing resources go further, to learn from each other and share resources. The approach is based on seeking resources created by the regulator or other relevant experts, sharing best practice, tools and technology across the industry and collaborating with experts and other platforms where possible.

Regulatory Track 1: (Amended) Enforced Self-Regulation

Tech platforms in this track will be willing to comply with regulation and have both the awareness and expertise, and capacity and resources, to fully comply. As a result of self-regulation not having worked in the past, this track proposes that something more than self-regulation is required. This research explored enforced self-regulation as an approach, however, argues that a balance between self-regulation and enforced self-regulation could have potential. This track, therefore, proposes an amended enforced self-regulation.

Self-regulation is defined by Ogus and Carbonara as “law formulated by private agencies to govern professional and trading activities”.Footnote101 Self-regulation, therefore, places the responsibility of ensuring compliance on the organisation itself. Ogus and Carbonara criticize that a self-regulatory approach has much potential for abuse, and this is supported by the Jugendschutz.net study on the NetzDG Act which found widespread inconsistency across tech platforms removal of content under a self-regulatory approach.Footnote102

According to Braithwaite, who first coined the term enforced self-regulation,

“Under enforced self-regulation, the government would compel each company to write a set of rules tailored to the unique set of contingencies facing that firm. A regulatory agency would either approve these rules or send them back for revision if they were insufficiently stringent. At this stage in the process, citizens’ groups and other interested parties would be encouraged to comment on the proposed rules”.Footnote103

Hutter describes enforced self-regulation as,

“a mix of state and corporate regulatory efforts. The government lays down broad standards which companies are then expected to meet. This involves companies in developing risk management systems and rules…regulatory officials oversee this process. They undertake monitoring themselves and can impose public sanctions for non-compliance”.Footnote104

This regulatory track is based on this enforced self-regulation approach, however, has some amendments that must be noted. Regulation typically sets out regulatory demands that companies must comply with. Under an enforced self-regulatory approach, companies can have freedom to write their own rules that they must comply with and the regulator approves them. This article argues that tech platforms should not have this freedom to write their own regulatory rules. Regulation should be set out in an industry-wide standard that all tech platforms (with the help of the various tracks) must try to comply with. However, under the enforced self-regulatory approach, companies have flexibility in how they meet these regulatory demands and are monitored by regulators to ensure that they are meeting compliance. This means that two platforms in this track may adopt different methods to one another in their efforts to comply with the same regulation, however, still achieve the same outcome. If the regulator assesses that the decisions/methods tech platforms have implemented to comply with the regulatory standards are not sufficient then, in an enforced self-regulation style, the regulator will inform the platform that they must revise these methods. If the tech platform fails to revise the methods, then the regulator will take enforcement action, beginning at the bottom of the enforcement pyramid and working up the levels until the tech platform complies. Therefore, unlike traditional enforced self-regulation, the tech platforms are not free to write their own regulatory standards. However, the tech platforms do have some freedom and flexibility in deciding how they undertake regulatory compliance and this will be overseen by a regulator and either result in approval with on-going monitoring, or revision and monitoring.

It is important to note that no regulatory approach is perfect, there are some potential limitations to this approach. Enforced self-regulation has been criticised as risking regulatory overkill, complicating the regulatory landscape, and trying to disguise that it is still government regulation.Footnote105 Bruhn raises the problem of the “inspectors dilemma” whereby the regulator will face challenges when monitoring compliance, such as dealing with competing values between the different parties and the expectations that contradictory demands and objectives are solved or fulfilled.Footnote106

Although there are limitations, an enforced self-regulatory approach and the amendment made to this approach for this context, aims to overcome these problems and the problems identified with self-regulation. It proposes an industry wide-standard, that provides flexibility with the methods of compliance, however, without infringing on innovation.Footnote107 This could minimize the tensions and resentment that regulation can create, and provides a chance for strong relationships between the platforms and the regulator. It opens a channel of communication that can minimize misunderstandings and open pathways to clarifications and help if necessary. BraithwaiteFootnote108 and HutterFootnote109 argue that the flexibility with compliance methods is likely to make engagement and compliance more appealing to companies, with a subsequent benefit that the platforms will not be able to plead ignorance in situations of failed compliance. This approach brings together the expertise of both the regulator and the tech platforms which Bruhn argues is important because no party has the complete knowledge and comprehensive picture required to regulate.Footnote110 In response to the criticism that it could make the regulatory landscape more complex, where regulation puts forth clear regulatory demands in an industry-wide manner, it is more likely that this approach will help to make the regulatory landscape clearer. Other advantages include that it may instil a new sense of trust from the public.Footnote111 This is because the regulatory demands have been set by an independent regulator and the monitoring undertaken by the regulator ensures the accountability that self-regulation is missing. The on-going monitoring and threat of enforcement action creates a compliance incentive.Footnote112 Finally, enforced self-regulation is less time-consuming than other models of regulation.Footnote113

It is argued that platforms in this track are capable of becoming more critical of themselves and developing a culture of self-evaluation. This could result in a culture of continuous improvement and development.Footnote114 Tech platforms in this track are thought to be capable of this because they are willing and have the knowledge, expertise and resources required to do so. Under such requirements, a tech platform should direct efforts to improving “communications, training, management style, and improving efficiency and effectiveness”, with long-term goals in mind, where possible.Footnote115

As this track is the regulatory track with the most hands-off approach from the regulator, the regulator will need to be cautious of attempts by tech platforms to evade a more hands-on regulatory track.Footnote116 It is important that the tech platforms are aware that the regulator can remove them from this track at any time, and are aware of the tools the regulator has at its disposal. If the regulator does not remove platforms from this track during non-compliance, then the regulator will lose credibility.

Conclusion

This article discussed research into a responsive regulatory approach which categorises companies regarding regulatory non-compliance. The main benefit is the creation of profiles of each different category of company which can be used to create tailored responses. This article created four categories of platforms regarding compliance with regulation to counter terrorist content on their services. These were lacking the: awareness and expertise to comply; capacity and resources to comply; willingness to comply; or having the knowledge and expertise, capacity and resources, and willingness to comply. In response, four regulatory tracks were proposed to try to increase compliance. An enforcement pyramid is used to try to take a primarily educative approach to helping the platforms achieve compliance, only using a punitive approach when there is no other choice.

These four categories and regulatory tracks are proposed in response to the issues of the previously tried self-regulatory approach, and to mitigate the criticisms of existing regulation. This approach proposes more involvement from the regulator than has been undertaken in this context before, however, has been used in other industries. Whilst these categories and tracks may not be exhaustive and come with some limitations, they have been proposed in order to raise awareness of the compliance issues with existing regulation and to try to overcome the concerns around over-blocking and unfair burdens on smaller platforms during attempts to counter online terrorist content on these services.

Acknowledgements

This article was based on a chapter from my PhD thesis. I would like to thank my PhD supervisors Professor Stuart Macdonald; Dr Lella Nouri; and Dr Patrick Bishop for all the guidance and feedback that went into this chapter and my PhD thesis more broadly.

Disclosure Statement

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Notes

1 Self-regulation relies “substantially on the goodwill and cooperation of individual firms for their compliance” (Sinclair, 1977, p. 534)

2 Jillian York and Christoph Schmon, “The EU Online Terrorism Regulation: a Bad Deal.” Electronic Frontier Foundation (2021). https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/04/eu-online-terrorism-regulation-bad-deal (accessed June 21, 2022).

3 Julia Black, “Decentring Regulation: Understanding the Role of Regulation and Self-Regulation in a “Post-Regulatory” World,” Current Legal Problems 54 (2001a): 103–47; Julia Black, “Critical Reflections on Regulation,” Australian Journal of Legal Philosophy 27, no. 1 (2002): 1–27.

4 Regulation can be in traditional command-and-control format; however, it can also use non-legislative instruments such as standards, guidance, and licensing (Kosti et al. 2019), and is used for what might be called ‘double edged sword’ activities where the aim is to attenuate the negative aspects of an activity whilst preserving its positive aspects.

5 Majid Yar, “A Failure to Regulate? The Demands and Dilemmas of Tackling Illegal Content and Behaviour on Social Media,” International Journal of Cybersecurity Intelligence & Cybercrime 1, no. 1 (2018): 5–20.

6 Giovanni De Gregorio, “Democratising online content moderation: A constitutional framework.” Computer Law & Security Review 36 (2020): 105374.

7 Timothy S. Wu, “Cyberspace Sovereignty–The Internet and the International System,” Harvard Journal of Law & Technology 10 (1996): 647.; Des Freedman, Outsourcing internet regulation. Misunderstanding the internet (2012), 95–120.

8 David S. Ardia, “Free Speech Savior Or Shield For Scoundrels: An Empirical Study of Intermediary Immunity under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act,” Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review 43 (2019): 373; Wolfgang Schulz, “Regulating Intermediaries to Protect Privacy Online–The Case of the German NetzDG,” HIIG Discussion Paper Series (2018): 1–14.

9 März (2018) Leitlinien zur Festsetzung von Geldbußen im Bereich des Netzwerkdurchsetzungsgesetzes (NetzDG) vom 22., p. 3., Cited in Sandra Schmitz and Christian M. Berndt, “The German Act on Improving Law Enforcement on Social Networks (NetzDG): A Blunt Sword?. “Available at SSRN 3306964 (2018); Sandra Schmitz and Christian M. Berndt, “The German Act on Improving Law Enforcement on Social Networks (NetzDG): A Blunt Sword?” Available at SSRN 3306964 (2018): 1–41; Andreas Splittgerber and Friederike Detmering, Germany’s new hate speech act in force: what social network providers need to do now. Technology Law Dispatch (2017). https://www.technologylawdispatch.com/2017/10/social-mobile-analytics-cloud-smac/germanys-new-hate-speech-act-in-force-what-social-network-providers-need-to-do-now/?utm_content=bufferd5f9a&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer#page=1 (accessed June 21, 2022); Article 19, “Germany: The Act to Improve Enforcement of the Law in Social Networks” (2017). https://www.article19.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/170901-Legal-Analysis-German-NetzDG-Act.pdf (accessed June 21, 2022), 1–25; William Echikson and Olivia Knodt, “Germany’s NetzDG: A Key Test for Combatting Online Hate.” CEPS Research Reports No. 2018/09 (2018): 1–24; Stefan Theil, “The Online Harms White Paper: Comparing the UK and German Approaches to Regulation,” Journal of Media Law (2019): 1–11; Tech Against Terrorism, “The online regulation series | The United Kingdom” (2020a). https://www.techagainstterrorism.org/2020/10/22/online-regulation-series-the-united-kingdom/?utm_source=Tech+Against+Terrorism&utm_campaign=d1b6edac7b-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2019_03_24_07_51_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_cb464fdb7d-d1b6edac7b-140969075 (accessed June 21, 2022); Sally Broughton Micova and Sabin Jacques, “HM Government’s Online Harms White Paper Consultation response from the Centre for Competition Policy University of East Anglia.” (2019): 1–7; Patrick Bishop, Seán Looney, Stuart Macdonald, Elizabeth Pearson, and Joe Whittaker. “Response to the Online Harms White Paper”. CYTREC, Swansea University (2019) https://www.swansea.ac.uk/media/Response-to-the-Online-Harms-White-Paper.pdf (accessed June 21, 2022), 1–12; Ariel Bogle, “Laws Targeting Terror Videos on Facebook and YouTube ‘Rushed’ and ‘Knee-Jerk’, Lawyers and Tech Industry Say”. ABC (2019). https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2019-04-04/facebook-youtube-social-media-laws-rushed-and-flawed-critics-say/10965812 (accessed June 21, 2022); Andre Oboler, “In Australia, A New Law on Livestreaming Terror Attacks Doesn’t Take into Account How the Internet Actually Works,” Nieman Lab (2019). https://www.niemanlab.org/2019/04/in-australia-a-new-law-on-livestreaming-terror-attacks-doesnt-take-into-account-how-the-internet-actually-works/ (accessed June 21, 2022); Evelyn Douek, “Australia's’ Abhorrent Violent Material,” Australian Law Journal (2019): 41–60; Natalie Alkiviadou, “Hate Speech on Social Media Networks: towards a Regulatory Framework?” Information & Communications Technology Law 28, no.1 (2019): 19–35.

10 Amy-Louise Watkin, “Regulating Terrorist Content on Tech Platforms: A Proposed Framework Based on Social Regulation,” PhD Thesis (Swansea University, 2021).

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 European Commissions regulation ‘on preventing the dissemination of terrorist content online’ commonly known as TERREG, was adopted in April 2021. It places demands on tech platforms to counter terrorist content on their services. Accessed via https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52018PC0640

14 Germany introduced the Network Enforcement Act which is commonly known as NetzDG. It came into force January 2018. It seeks to counter fake news, hate speech and misinformation on tech platforms. Accessed via https://www.bmj.de/SharedDocs/Gesetzgebungsverfahren/Dokumente/NetzDG_engl.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2

15 David Kaye, “Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression” (2018). https://perma.cc/9XWD-7JQU (accessed June 21, 2022).

16 Evan Engstrom and Nick Feamster, “The limits of filtering: A look at the functionality and shortcomings of content detection tools” (2017) https://perma.cc/UV5H-89SK (accessed June 21, 2022): 1–27; Daphne Keller, “Internet Platforms: Observations on Speech, Danger and Money,” Aegis Series Paper No. 1807 (2018): 1–43; Bernhard Warner, “Tech Companies are Deleting Evidence of War Crimes,” The Atlantic (2019). https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/05/facebook-algorithms-are-making-it-harder/588931/ (accessed June 21, 2022).

17 Mia Bloom, Hicham Tiflati, and John Horgan, “Navigating ISIS’s Preferred Platform: Telegram,” Terrorism and Political Violence 31, no.6 (2019): 1242–54.; Maura Conway, Moign Khawaja, Suraj Lakhani, Jeremy Reffin, Andrew Robertson, and David Weir, “Disrupting Daesh: Measuring Takedown of Online Terrorist Material and Its Impacts,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 42, no.1-2 (2019): 141–60; Lella Nouri, Nuria Lorenzo-Dus and Amy-Louise Watkin, “Following the whack-a-mole: Britain First’s Visual Strategy from Facebook to Gab.” Global Research Network on Terrorism and Technology: Paper No. 4 (2019): 1–20; Nick Robins-Early, “Like ISIS Before Them, Far-Right Extremists Are Migrating to Telegram,” Huffington Post (2019). https://www.huffpost.com/entry/telegram-far-right-isis-extremists-infowars_n_5cd59888e4b0705e47db36ef (accessed June 21, 2022); Sidney Fussell, (2019) “Why the New Zealand Shooting Video Keeps Circulating,” The Atlantic (2019). https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/03/facebook-youtube-new-zealand-tragedy-video/585418/ (accessed June 21, 2022).

18 Tech Against Terrorism, “ISIS Use of Smaller Platforms and the DWeb to Share Terrorist Content,” Tech Against Terrorism (2019). https://www.techagainstterrorism.org/2019/04/29/analysis-isis-use-of-smaller-platforms-and-the-dweb-to-share-terrorist-content-april-2019/ (accessed June 21, 2022).

19 Ian Ayres and John Braithwaite, J. Responsive Regulation (Oxford: OUP, 1992).

20 Ibid.

21 Vibeke Lehmann Nielsen and Christine Parker, “Testing Responsive Regulation in Regulatory Enforcement,” Regulation & Governance 3, no. 4) (2009): 376–99.

22 Ibid.

23 Ian Ayres and John Braithwaite, J. Responsive Regulation (Oxford: OUP, 1992); John Braithwaite, Restorative Justice & Responsive Regulation (Oxford University Press On Demand, 2002).

24 Ton Van Snellenberg and Rob van de Peppel, “Perspectives on Compliance: Non‐Compliance With Environmental Licences in the Netherlands,” European Environment 12, no. 3 (2002):131–48.

25 Robyn Fairman and Charlotte Yapp, “Enforced Self‐Regulation, Prescription, And Conceptions Of Compliance Within Small Businesses: The Impact Of Enforcement.” Law & Policy 27, no. 4 (2005): 491–519.

26 Vibeke Lehmann Nielsen and Christine Parker, “Testing Responsive Regulation in Regulatory Enforcement,” Regulation & Governance 3, no. 4 (2009): 376–99.

27 Robert Kagan and John T. Scholz, “Criminology of the Corporation and Regulatory Enforcement Strategies.” in Enforcing Regulation, ed. Keith Hawkins and John M. Thomas (Boston: Kluwer Nijhoff, 1984): 67–95.

28 Keith Hawkins, Environment and Enforcement (Oxford: OUP, 1984).

29 Ibid.

30 Robert Baldwin, Rules and Government (Oxford: OUP, 1995).

31 Neil Gunningham, “Enforcement and Compliance Strategies,” The Oxford Handbook of Regulation 120 (2010): 131–35.

32 Julia Black, “Managing Discretion”. Unpublished manuscript, London School of Economics, UK (2001b): 1–40; Robert Baldwin. Rules and Government (Clarendon Press, 1997).

33 Julia Black, “Managing Discretion”. Unpublished manuscript, London School of Economics, UK (2001b): 1–40.

34 Eugene Bardach and Robert A. Kagan. Going by the Book: The Problem of Regulatory Unreasonableness (Routledge, 1982).

35 Peter Mascini, “Why was the Enforcement Pyramid so Influential? And What Price Was Paid?” Regulation & Governance 7, no. 1 (2013): 48–60.

36 Ian Ayres and John Braithwaite, J. Responsive Regulation (Oxford: OUP, 1992); John Braithwaite, Restorative Justice & Responsive Regulation (Oxford University Press On Demand, 2002).

37 Neil Gunningham, “Enforcement and Compliance Strategies.” in The Oxford Handbook Of Regulation 120 (2010): 131–35.

38 Julia Black, “Managing Discretion”. Unpublished manuscript, London School of Economics, UK (2001b): 1–40.

39 Amy-Louise Watkin, “Regulating Terrorist Content on Tech Platforms: A Proposed Framework Based on Social Regulation,” PhD thesis (Swansea University, 2021).

40 A reality for many tech platforms according to Brian Fishman, Head of Counterterrorism Policy at Facebook https://tnsr.org/2019/02/crossroads-counter-terrorism-and-the-internet/

41 Isaac, Kfir, “Terrorist Innovation and Online Propaganda in the Post-Caliphate Period”. Available at SSRN 3475008. (2019): 1–30.

42 Tech Against Terrorism, “REPORT: Conclusions from the online consultation process for the Terrorist Content Analytics Platform (TCAP) – August 2020.” Tech Against Terrorism (2020b) https://www.terrorismanalytics.org/policies/consultation-report (accessed June 21, 2022).

43 See Watkin (2021) for a chapter that explains the different ways that terrorist organisations use different tech platforms.

44 Tech Against Terrorism, “REPORT: Conclusions from the Online Consultation Process for the Terrorist Content Analytics Platform (TCAP) – August 2020.” Tech Against Terrorism (2020b). https://www.terrorismanalytics.org/policies/consultation-report (accessed June 21, 2022).

45 Adam Hadley and Jacob Berntsson, J. Regulation: Concerns about effectiveness and impact on smaller tech platforms. VOX-Pol Blog (2020). https://www.voxpol.eu/the-eus-terrorist-content-regulation-concerns-about-effectiveness-and-impact-on-smaller-tech-platforms/ (accessed June 21, 2022); Article 19, “EU: Terrorist content regulation must protect freedom of expression rights.” Article 19. (2020). https://www.article19.org/resources/eu-terrorist-content-regulation-must-protect-freedom-of-expression-rights/ (accessed June 21, 2022)

46 Julia Black, “Managing Discretion”. Unpublished manuscript, London School of Economics, UK (2001b): 1–40.

47 Robyn Fairman and Charlotte Yapp, “Enforced Self‐Regulation, Prescription, and Conceptions of Compliance Within Small Businesses: The Impact of Enforcement,” Law & Policy 27, no. 4 (2005): 491–519.

48 Karl Weick, Making Sense of the Organisation (London: Blackwell, 2001).

49 Robyn Fairman and Charlotte Yapp, “Enforced Self‐Regulation, Prescription, and Conceptions of Compliance within Small Businesses: The Impact of Enforcement,” Law & Policy 27, no. 4 (2005): 491–519.

50 Ibid.

51 Tech Against Terrorism, “ISIS use of smaller platforms and the DWeb to share terrorist content.” Tech Against Terrorism (2019). https://www.techagainstterrorism.org/2019/04/29/analysis-isis-use-of-smaller-platforms-and-the-dweb-to-share-terrorist-content-april-2019/ (accessed June 21, 2022).

52 Robyn Fairman and Charlotte Yapp, “Enforced Self‐Regulation, Prescription, and Conceptions of Compliance within Small Businesses: The Impact of Enforcement,” Law & Policy 27, no. 4 (2005): 491–519.

53 Keith Hawkins, Environment and Enforcement (Oxford: OUP, 1984); Bridget M. Hutter, Compliance: Regulation and Environment (Oxford: OUP, 1997).

54 Albert J. Reiss, "Selecting Strategies of Social Control Over Organizational Life,'’ in Enforcing Regulation, ed. Keith Hawkins and John Thomas (Boston: Kluwer-Nijhoff, 1984): 23–35.

55 Robyn Fairman and Charlotte Yapp, “Enforced Self‐Regulation, Prescription, and Conceptions of Compliance Within Small Businesses: The Impact of Enforcement,” Law & Policy 27, no. 4 (2005): 491–519.

56 John Braithwaite and Toni Makkai, “Testing an Expected Utility Model of Corporate Deterrence. Law & Society Review 25, no. 7 (1991).

57 Julia Black, “Managing Discretion” Unpublished manuscript, London School of Economics, UK (2001b): 1–40.

58 Ian Ayres and John Braithwaite, J. Responsive Regulation (Oxford: OUP, 1992).

59 Vibeke Lehmann Nielsen and Christine Parker, “Testing Responsive Regulation in Regulatory Enforcement,” Regulation & Governance 3, no. 4 (2009): 376–99.

60 Richard Johnstone, “From Fiction to Fact-Rethinking OHS Enforcement', National Research Centre for Occupational Health and Safety Regulation (Vol. 11).” Working Paper 11. (2003).

61 Ian Ayres and John Braithwaite, J. Responsive Regulation. (Oxford: OUP, 1992); Stephen Fineman and Andrew Sturdy, “The Emotions Of Control: A Qualitative Exploration Of Environmental Regulation,” Human Relations 52, no. 5 (1999): 631–663.

62 Keith Hawkins, Environment and Enforcement (Oxford: OUP, 1984).

63 Neil Gunningham, “Enforcement and Compliance Strategies.” in The Oxford Handbook of Regulation 120, (2010): 131–35.

64 Ibid; John Braithwaite, To Punish or Persuade: Enforcement of Coal Mine Safety (SUNY Press, 1985).

65 John Braithwaite, “Convergence in Models of Regulatory Strategy,” Current Issues in Criminal Justice 2, no. 1 (1990): 63, 59–65.

66 Marshall Clinard and Peter Yeager, “Corporate Crime (Vol. 1).” (Transaction Publishers, 2011); Leonard Orland, “Reflections on Corporate Crime: Law in Search of Theory and Scholarship,” American Criminal Law Review 17, (1979): 501; Christopher D. Stone, “Where the Law Ends: The Social Control of Corporate Behavior,” Business Horizons 19, no. 3 (1976): 84–87; Brent Fisse and John Braithwaite, J., “Sanctions Against Corporations: Dissolving the Monopoly of Fines,” Business Regulation in Australia 129 (1984): 146.

67 John Braithwaite, “Convergence in Models of Regulatory Strategy,” Current Issues in Criminal Justice 2, no. 1 (1990): 63.

68 John Braithwaite, To Punish or Persuade: Enforcement of Coal Mine Safety (SUNY Press, 1985); Christopher Kennedy, “Criminal Sentences for Corporations: Alternative Fining Mechanisms,” California Law Review 73 (1985): 443.

69 John Braithwaite, To Punish or Persuade: Enforcement of Coal Mine Safety (SUNY Press, 1985); Christopher Kennedy, “Criminal Sentences for Corporations: Alternative Fining Mechanisms,” California Law Review 73 (1985): 443; Patrick Bishop and Stuart Macdonald, “Terrorist Content and the Social Media Ecosystem: The Role of Regulation,” in Digital Jihad: Online Communication and Violent Extremism, ed. Francesco Marone (ISPI, 2019): 132–52.

70 Patrick Bishop and Stuart Macdonald, “Terrorist Content and the Social Media Ecosystem: The Role of Regulation,” in Digital Jihad: Online Communication and Violent Extremism, ed. Francesco Marone (ISPI, 2019), 132–52.

71 John Braithwaite, To Punish or Persuade: Enforcement of Coal Mine Safety (SUNY Press, 1985).

72 Ibid.

73 Patrick Bishop and Stuart Macdonald, “Terrorist Content and the Social Media Ecosystem: The Role of Regulation,” in Digital Jihad: Online Communication and Violent Extremism, ed. Francesco Marone (ISPI, 2019): 132–52.

74 Ibid.

75 Ibid.

76 Christopher Kennedy, “Criminal Sentences for Corporations: Alternative Fining Mechanisms,” California Law Review 73 (1985): 443.

77 Patrick Bishop and Stuart Macdonald, “Terrorist Content and the Social Media Ecosystem: The Role of Regulation,” in Digital Jihad: Online Communication and Violent Extremism, ed. Francesco Marone (ISPI, 2019): 132–52.

78 Ibid.

79 David Gilbert, “Here’s How Big Far Right Social Network Gab has Actually Become,” Vice (2019). https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/pa7dwg/heres-how-big-far-right-social-network-gab-has-actually-become (accessed June 21, 2022); Patrick Bishop, Seán Looney, Stuart Macdonald, Elizabeth Pearson, and Joe Whittaker. “Response to the Online Harms White Paper”. CYTREC, Swansea University. (2019) https://www.swansea.ac.uk/media/Response-to-the-Online-Harms-White-Paper.pdf (accessed June 21, 2022): 1–12.

80 Patrick Bishop and Stuart Macdonald, “Terrorist Content and the Social Media Ecosystem: The Role of Regulation,” in Digital Jihad: Online Communication and Violent Extremism, ed. Francesco Marone (ISPI, 2019): 132–52; Home Office (UK), Online Harms White Paper – Initial consultation response (2020). https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/online-harms-white-paper/public-feedback/online-harms-white-paper-initial-consultation-response (accessed June 21, 2022).

81 Patrick Bishop and Stuart Macdonald, “Terrorist Content and the Social Media Ecosystem: The Role of Regulation,”. in Digital Jihad: Online Communication and Violent Extremism, ed. Francesco Marone (ISPI, 2019): 132–52.

82 Sally Broughton Micova and Sabin Jacques, “HM Government’s Online Harms White Paper Consultation response from the Centre for Competition Policy University of East Anglia” (2019): 1–7.

83 Patrick Bishop and Stuart Macdonald, “Terrorist Content and the Social Media Ecosystem: The Role of Regulation,” in Digital Jihad: Online Communication and Violent Extremism, ed. Francesco Marone (ISPI, 2019): 132–52.

84 John Braithwaite, "The Essence of Responsive Regulation," UBC Law Review. 44 (2011): 475.

85 Neil Gunningham, Robert A. Kagan, and Dorothy Thornton. Shades of Green: Business, Regulation, and Environment (Stanford University Press, 2003).

86 Sidney A. Shapiro, and Randy S. Rabinowitz. "Punishment Versus Cooperation in Regulatory Enforcement: A Case Study of OSHA," Administrative Law Review 49 (1997): 713.

87 Anders Bruhn, “The Inspector’s Dilemma Under Regulated Self-Regulation,” Policy and Practice in Health and Safety 4, no. 2 (2006): 3–23.

88 Tech Against Terrorism, “REPORT: Conclusions from the online consultation process for the Terrorist Content Analytics Platform (TCAP) – August 2020.” Tech Against Terrorism (2020b). https://www.terrorismanalytics.org/policies/consultation-report (accessed June 21, 2022)

89 The Christchurch Call is an example of an existing collaboration, it includes over 120 governments, online service providers and civil society organisations, see https://www.christchurchcall.com/

90 GIFCT is an independent organization that undertakes a lot of work with tech platforms to remove terrorist content, including the Hash Sharing Database, its Independent Advisory Council, and Working Groups amongst other things that can be read about on their website https://gifct.org/

91 Evelyn Douek, “The Rise of Content Cartels,” Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia (2020), 28.

92 Emma Llanso, “Platforms Want Centralized Censorship. That Should Scare You.” Wired (2019). https://www.wired.com/story/platforms-centralized-censorship/ (accessed June 21, 2022).

93 Evelyn Douek, “The Rise of Content Cartels,” Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia (2020), 28.

94 Ibid, 28.

95 Emma Llanso, “Content Moderation Knowledge Sharing Shouldn’t Be A Backdoor To Cross-Platform Censorship,” Techdirt (2020). https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20200820/08564545152/content-moderation-knowledge-sharing-shouldnt-be-backdoor-to-cross-platform-censorship.shtml:?utm_source=Tech+Against+Terrorism&utm_campaign=6ebef31ab9-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2019_03_24_07_51_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_cb464fdb7d-6ebef31ab9-140969075 (accessed June 21, 2020).

96 Evelyn Douek, “The Rise of Content Cartels,” Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia (2020): 28.

97 Emma Llanso, “Content Moderation Knowledge Sharing Shouldn’t be a Backdoor to Cross-Platform Censorship,” Techdirt (2020). https://www.techdirt.com/articles/20200820/08564545152/content-moderation-knowledge-sharing-shouldnt-be-backdoor-to-cross-platform-censorship.shtml:?utm_source=Tech+Against+Terrorism&utm_campaign=6ebef31ab9-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2019_03_24_07_51_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_cb464fdb7d-6ebef31ab9-140969075 (accessed June 21, 2020).

98 Tech Against Terrorism, “Transparency reporting for smaller platforms.” (2020c) https://www.techagainstterrorism.org/2020/03/02/transparency-reporting-for-smaller-platforms/?utm_source=Tech+Against+Terrorism&utm_campaign=d7804fffb6-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2019_03_24_07_51_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_cb464fdb7d-d7804fffb6-140969075 (accessed June 21, 2022).

99 YouTube, “Growing our Trusted Flagger Program into YouTube Heroes,” YouTube. (2016) https://youtube.googleblog.com/2016/09/growing-our-trusted-flagger-program.html (accessed June 21, 2022).

100 Ibid.

101 Anthony Ogus and Emanuela Carbonara, “Self-regulation,” in Production of Legal Rules (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2011), 587.

102 Jugendschutz.net, Löschung rechtswidriger Hassbeiträge bei Facebook, YouTube und Twitter, (2017) Cited in The German Act on Improving Law Enforcement on Social Networks (NetzDG): A Blunt Sword?. Sandra Schmitz and Christine M Berdnt. (2018) Available at SSRN 3306964.

103 John Braithwaite, “Enforced Self-Regulation: A New Strategy for Corporate Crime Control,” Michigan Law Review 80, no.7 (1982): 1470.

104 Bridget M. Hutter, “Is Enforced Self-regulation a Form of Risk Taking?: The Case of Railway Health and Safety,” International Journal of the Sociology of Law 29, no. 4 (2001): 380.

105 Robert, P. Kaye, “Regulated (Self-) Regulation: A New Paradigm for Controlling the Professions?,” Public Policy and Administration 21, no. 3 (2006): 105–19.

106 Anders Bruhn, “The Inspector’s Dilemma Under Regulated Self-regulation,” Policy and Practice in Health and Safety 4, no. 2 (2006): 3–23.

107 Bridget M. Hutter, “Is Enforced Self-regulation a Form of Risk Taking?: The Case of Railway Health and Safety,” International Journal of the Sociology of Law 29, no. 4 (2001): 380, 379–400.

108 John Braithwaite, “Enforced Self-regulation: A New Strategy for Corporate Crime Control,” Michigan Law Review 80, no.7 (1982): 1470, 1466–507.

109 Bridget M. Hutter, “Is Enforced Self-Regulation a Form of Risk Taking?: The Case of Railway Health and Safety,” International Journal of the Sociology of Law 29, no. 4 (2001): 380, 379–400.

110 Anders Bruhn, “The Inspector’s Dilemma Under Regulated Self-Regulation,” Policy and Practice in Health and Safety 4, no. 2 (2006): 3–23.

111 Robert, P. Kaye, “Regulated (Self-) Regulation: A New Paradigm for Controlling the Professions?,” Public Policy and Administration 21, no. 3 (2006): 105–19.

112 John Braithwaite, “Enforced Self-regulation: A New Strategy for Corporate Crime Control,” Michigan Law Review 80, no.7 (1982): 1470, 1466–507.

113 Bridget M. Hutter, “Is Enforced Self-regulation a Form of Risk Taking?: The Case of Railway Health and Safety,” International Journal of the Sociology of Law, 29, no. 4 (2001): 380, 379–400.

114 Annick Carnino, "Management of Safety, Safety Culture and Self Assessment" (2000): 4, 11–14.

115 Ibid, 4

116 Kimberly D. Krawiec, “Organisational Misconduct: Beyond the Principal-agent Model,” Florida State University Law Review 32 (2004): 571.