Abstract

Recognizing the correlation between the growing spread of violent extremist and terrorist content on the internet and online platforms and the significant increase in attacks inspired by these posts prompted governments, security agencies, and private companies to launch various countermeasures to reduce the spread and impact of such material. Struggling to adjust to these countermeasures and maintain their online presence, terrorists and violent extremists have migrated from mainstream online platforms to alternative online channels like 4chan, 8chan, Telegram, TikTok, and most recently to the new platform TamTam. This paper describes the migration to and within social media generally, with a specific focus on the newly discovered migration to the platform TamTam and presents the results of our extensive content analysis of hundreds of posts and shares containing terrorist and violent extremist content on this platform. These findings are discussed in terms of ethical and practical implications.

Terrorists and violent extremists have been very resourceful in adapting and applying online platforms. Almost every new online platform and application – has been exploited by cyber-savvy terrorists and extremists. Starting with websites (since the late 1990s), these actors and groups have continued to evolve, adding forums and chatrooms; then, beginning in 2014, expanding to new social media (e.g. Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Instagram), online messenger apps (like WhatsApp, Telegram), moved to new platforms (from 4chan and 8chan to TikTok), using anonymous cloud storage platforms, and utilizing the Dark Net.Footnote1 While having never developed any new online channel or platform, these actors and groups were and still are learning how to use and exploit the most recent advancements and evolutions in the cyber sphere. These online platforms have become vital tools in their efforts to spread fear, radicalize, recruit new members, raise money, launch propaganda campaigns, teach and train, and coordinate attacks. In an attempt to combat the use of these online tools, social media platforms have felt pressure to take down this material from governments and security services. Despite these efforts, terrorists and extremists have maintained their presence on all social media, even moving to new platforms that are less regulated, providing them with free access, greater anonymity, and global audiences. This is how they explored and used platforms like 4chan, 8chan, Telegram, and TikTok, and, recently, the less know migration to TamTam. We will describe the migration to and within social media, as well as the recently discovered migration to the platform TamTam, and present the results of our extensive content analysis of hundreds of posts and shares containing terrorist and violent extremist content on this platform. Just as a previous study on the use of TikTok by violent extremists was the first to uncover the alarming abuse of that platform,Footnote2 we hope that the present study will join other studies in revealing the abuse of this new platform and the challenges it poses to countering online hate, violence, and terrorism.

Online Migration to and within Social Media

Terrorists’ and violent extremists’ online presence has developed over three decades, using websites, online forums, chatrooms, and, more recently, social media.Footnote3 The growing presence of terrorists and extremists in cyberspace is at the nexus of two key trends: the democratization of communications driven by user-generated content on the internet and the growing awareness of modern extremists of the potential of online channels for their aims. Consequently, not only has the number of terrorist/extremist online platforms increased rapidly, but the forms of usage have also diversified. The great virtues of online platforms, from websites to social media, are primarily anonymity, fast flow, ease of access, lack of regulation, and vast potential audiences.Footnote4 These advantages have not gone unnoticed by terrorists and violent extremist actors, who moved their communications, propaganda, instruction, and training to online platforms. As Hoffman and Ware concluded, “today’s far-right extremists, like predecessors from previous generations, are employing cutting-edge technologies for terrorist purposes.”Footnote5

The internet, which served in the late 1990s and early 2000s as the primary platform for various terrorist groups, was gradually replaced by the rise of social media. These platforms, which are user-based, allow for posting and sharing content, interactivity, and feedback. Thus, communication on social media is fundamentally different from that on the traditional internet, which is relatively stable, hierarchical, and less interactive. As a result, social networking online has become more attractive for violent extremist groups when targeting potential members and followers. These types of virtual communities are growing increasingly popular all over the world, especially among younger demographic groups. Extremist groups specifically target youth for propaganda, incitement, and recruitment purposes. More than a decade ago, Kohlman noted that “90% of terrorist activity on the internet takes place using social networking tools … These forums act as a virtual firewall to help safeguard the identities of those who participate, and they offer subscribers a chance to make direct contact with terrorist representatives, to ask questions, and even to contribute and help out the cyberjihad.”Footnote6

The growing concern that online contents could inspire attacks and the successful recruitment of foreign fighters through online interactions caused governments and security agencies to launch various countermeasures.Footnote7 These measures included the “deplatforming” of terrorist and violent extremist online content, interruption of their social media accounts, and pressuring social media companies to remove terrorist propaganda. Consequently, tech companies and social media platforms have increased their capabilities to detect and remove such content.Footnote8 To support these efforts, social media platforms like Facebook, YouTube, Microsoft, and Twitter have coordinated their deplatforming efforts through the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT) in order to deny accessibility to terrorist groups and to take down online accounts used for terrorist purposes. For example, Facebook reported using a system combining artificial intelligence and machine learning to remove over three million posts of the Islamic State (IS) and al-Qaeda propaganda. Twitter also announced that it had removed over a million accounts for promoting and sharing terrorist content. Striving to overcome these countermeasures and maintain their online presence, groups like IS had to move from mainstream online platforms to alternative online channels. They migrated to newer and less strict platforms such as Telegram, 4chan, 8chan, and TikTok to disseminate propaganda items. In reaction, in 2019, the European Union’s Internet Referral Unit and Telegram launched an extensive operation to remove accounts and channels associated with IS. The campaign resulted in the removal of more than 250 channels belonging to IS’s Nashir News Agency, Caliphate News 24, the Nasikh Agency, and most other major groups and channels.Footnote9 These measures caused another wave of migration within social media: in 2019, IS and al-Qaeda operatives and sympathizers migrated from their traditional digital hubs such as Twitter, Facebook, and Telegram to Diaspora, Friendica, MeWe, Riot, Threema, Hoop Messenger, Mastodon, and Rocket Chat.Footnote10 A range of relatively new and highly accessible communication “applications” is another component of this trend. One of these new applications is TamTam.

TamTam’s Story

TamTam is a relatively new online messaging application. It allows the users to invite up to 20,000 participants to a public or private chat, add up to 50 chat administrators, share files up to 2 GB, have group video calls with up to 100 participants, and get unlimited cloud storage. All these services are provided free of charge. In addition, it allows the use of texting, voice, or video calls, with all messages encrypted and stored in a distributed network of servers. Like Telegram, TamTam requires only a telephone number to log in, with the application being available on mobile phones, personal computers, and notebooks.

TamTam is a messenger application launched in May 2017 by the Russian company Mail.ru Group (which also owns Vkontakte, Odnoklassniki, and ICQ). Its launch followed the Russian authorities’ order to internet service providers to start blocking the instant messenger Telegram on 16 April 2017. A few days earlier, advertisements for the new chat app started appearing on several Telegram channels (and even in a few newspapers). In addition, a day before Russia began blocking Telegram, TamTam introduced the ability to create anonymous accounts that do not require a linked mobile phone number (which is how Telegram accounts are registered), letting users sign up with existing accounts on Google or Odnoklassniki.

The TamTam application was announced as a “complete copy of Telegram” and “another messenger with channels,” suggesting that this is the new app that would replace Telegram in Russia. The developers declared that TamTam “has channels that can be opened by ordinary users, as well as brands, media outlets, bloggers, and other authors.” Footnote11 Indeed, TamTam is so similar to Telegram that even its domain name differs by just a single character: “tt.me” instead of Telegram’s “t.me.” In October 2017, TamTam launched voice and video calls, as well as a Web-accessible version. After its initial release, the application saw quick adoption, with Mail.ru Group claiming that TamTam reached a combined 3 million installations on iOS and Android devices in September 2017 only.Footnote12

TamTam’s liberal policies, easy access with no registration required, growing reach, and multimedia services also attracted terrorists and violent extremists. For example, IS (the Islamic State) chose TamTam as its platform to claim responsibility for the November 2019 London Bridge attack, where a 28-year-old British citizen of Pakistani origin, Usman Khan, killed two people by stabbing and injured three others. Although this was the first time IS used TamTam to claim responsibility for a terrorist attack, its use of the platform was noted as early as April 2018 when it was discovered that IS had set up several channels in TamTam, under the name Nashir News Agency. In 2019, it became evident that “ISIS supporters secretly staged a mass migration from messaging app Telegram to a little-known Russian platform.”Footnote13 ISs’ move to TamTam even frustrated some of its supporters, who alleged that “TamTam is Russian malware” that could give “spies access to all of the accounts on your device.”Footnote14

But it was not only IS: TamTam services have also been used by neo-Nazis, accelerationists, and other violent extremist groups. In November 2022, a Counter Extremism Project (CEP) study found 13 channels on TamTam that promoted terrorism and neo-Nazi accelerationism, including bomb-making instructions.Footnote15 These channels, which “migrated” from Telegram, posted a series of guides on making explosives, the manifestos of several white supremacist shooters, videos of several neo-Nazi groups, including the Atomwaffen Division, The Base, The Feurkrieg Division, and The National Socialist Order. One of the posted videos, open to all users, was devoted to praising the violent actions of white supremacists, referring to them as “saints.” Seven channels on TamTam posted a neo-Nazi book acceleration book that was previously posted on Telegram. The over 260-page online book advocates acts of terrorism and violence, calls for lone wolf operations, attacks on infrastructure, and suggests targeting people of color, Jews, Muslims, Latinos, and the LGBT community. The book’s content, authored by more than 25 different writers, includes attractive graphics, essays, infographics, practical manuals for homemade explosives, copycat attacks of events like the Christchurch terrorist rampage, and practical instructions on target selection, surveillance, and equipment purchase. Responding to the CEP report, TamTam removed 18 channels that promoted acts of terrorism.Footnote16

Another study on violent extremist content migrating from Telegram to TamTam revealed that “several ERW major propaganda channel and chat admins had created backups of their Telegram assets on TamTam as early as July 2022, as these were being taken down on a weekly basis by Telegram. But by mid-November, these same admins were promoting TamTam as the future platform for accelerationist networks online – as one proponent of the move wrote, ‘Telegram is for losers […] the real top Gs are on TamTam’ – and dozens of new links to TamTam channels and chats had begun circulating across the Terrorgram Collective’s ecosystem.”Footnote17 It should be noted that TamTam’s own regulations prohibit users from promoting and calling for violence, terrorism, or extremism.Footnote18

Method

To study terrorist and extreme right wing (ERW) content on TamTam, we applied a multistep data collection and systematic content analysis. TamTam, like other similar messaging applications, has multiple entities, including users, personal chats (between users), and channels (where channel administrators can share media with subscribers to the channel). The first step involved in the detection of extremist narratives, images, and messages from both members of the extreme right wing and terrorism, was the identification of users and channels publishing, responding to, or sharing such content. Then we downloaded all the posted items (video clips, texts, graphics, etc.) into a digital database. In the second step, we conducted qualitative and qualitative content analysis on the database to reveal the characteristics of the content and the users.

Ethical Concerns: Researcher Safety & Collection of Data

Before beginning any field research, the authors considered the ethics related to researcher safety and collection of data in the “field.”

Researcher Safety

Multiple recent studies and reports have noted concerns about researcher safety, specifically highlighting the importance of protecting researchers’ mental, emotional, and physical wellbeing.Footnote19 Recent studies have highlighted that exposure to extremist propaganda, even in the context of conducting research can lead to emotional distress, cynicism, and anger.Footnote20 Drawing upon research which has shown that specific structural activities offered to researchers—such as mental health workshops and meetings with psychologists specializing in secondary trauma—can help to mitigate some of these potential issues, the authors worked with their research institute to offer training workshops on the type of content that research assistants may be exposed to during the study and also offered the opportunity for research assistants to meet with a counselor in one-on-one meetings. While this area of research on the ethics is still relatively understudied, the mitigation strategies for researcher psychological safety utilized in this study align with the findings of current recommendations and best-practices outlined in recent publications.Footnote21

In addition to concerns regarding the mental, emotional, and psychological wellbeing of researchers, other studies have highlighted concerns regarding the physical safety of researchers when conducting field research on political violence.Footnote22 While some of these risks are reduced when engaging in exclusively online research and analysis of extremist actors, there are still significant concerns that have been noted including “hack back,” wherein extremist actors are able to identify the researcher who is passively collecting data from known extremist sites and chat rooms by using specific technical skills.Footnote23 Recognizing that these concerns also applied to monitoring and data collection on TamTam, the authors developed a specific system for protecting the identities of all research assistants involved in the data collection process. The authors set up specific machines that did not possess any information about the researchers, assistants, or purpose of the research on them. In line with recommended best practices outlined in previous studies, the machines were “up-to-date and ha[d] anti-virus software installed.”Footnote24 These machines were only used by research assistants to review and collect data from the TamTam channels in the presence of one of the authors to ensure that they were following all predetermined procedures. At the conclusion of each working session—after the data had been input into the database—the machines were formatted to remove any history of activity and potentially harmful material. These procedures align with and build upon existing recommended practices for reducing the likelihood of a “hack back” or doxing by extremist actors when conducting online research.Footnote25

Ethics of Deception in Collecting Data

In addition to ethical questions regarding researcher safety, data collection also raises significant concerns. In social science research, the principle of “informed consent” from participants is widely upheld. However, its application in studies involving extremists and terrorists can be challenging, due to the potential risks researchers may face while trying to acquire such consent. Considering these risks, some researchers suggest strategies such as concealing the researcher’s identity, using pseudonyms, or “lurking” to collect data.Footnote26 Although these methods, particularly the use of pseudonyms and false profiles, are endorsed by some, primarily non-academics, for data collection on online extremist activities, recent studies indicate substantial ethical implications. For example, if all researchers were to use pseudonyms on extremist message boards, it could distort the perception of the number of genuine users.Footnote27

To avoid the potential repercussions of introducing additional false profiles and subsequently skewing the data, the authors of this study chose a non-intrusive method of data collection. They opted for a viewing-only approach, not joining any channels, groups, or chats. This methodology aligns with the authors’ commitment to non-engagement with the research subjects or their environment.

Sampling Method

Given the nature of the TamTam application and its search function, it is challenging to identify channels or users without having their exact user, group, or channel names on the platform. This unique challenge of the application meant that the preferred sample population was hidden or hard-to-reach. Drawing on the existing literature, which explored how to collect data and metadata from hidden or hard-to-reach populations on other similar messaging applications and platforms, we chose to utilize the snowball sampling method.Footnote28 This method has proven successful in accessing these hard-to-reach data, specifically extremist relation content, on these platforms as it relies on referrals from existing data to find subsequent data. Following the existing methodologies in similar studies of other platforms,Footnote29 we began by identifying key terms related to extreme right wing and jihadist extremism. These terms were drawn from published works on these groups’ most utilized narratives. The general topics included terms well-known terms used by these individuals and groups, such as “1488,” “National Socialism,” and “Siege” when searching for the extreme right wing, and “Jihad,” “Caliphate,” and “Caliph” for the jihadist content. Using these terms, we were able to identify two channels related to the extreme right wing, specifically accelerationist extremism, and one channel related to jihadist extremism.

After identifying these initial channels, we examined the posts (images, videos, audio messages), comments, and conversations on each channel to identify material that contained relevant content, such as discussions about extremist ideology, calls to action, or propaganda materials. Once the relevant posts and related users were identified in these “seed” channels, we examined the group membership lists of the individuals to identify other groups they were members of. During this second stage, any channel with fewer than ten posts was disregarded as irrelevant, following the precedent set by previous studies on similar platforms.Footnote30 In addition to examining the membership lists of the users of these “seed” channels, we also followed links to other TamTam channels and groups shared within the channels. These channels were then reviewed to determine their relevancy based on the content shared. By using the natural networks and shared affiliations of users, channels, and content, we were able to identify other groups and sources of content related to extremist narratives. This resulted in the identification of 9 channels that regularly produced, shared, or promoted extremist content. Given the nature of TamTam, it is possible that each of these channels are maintained by one user, a team, or a group of users.

The Database

Once relevant channels were identified, our team of coders (graduate research interns at the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism at Reichman University, Israel) began to collect, download, and store each post for analysis. For each post collected, the team downloaded the post or artifact (video, image, PDF, audio file, or text) and its relevant metadata, including the identity of the post author, date of publication, time of publication, content type, and the total number of views of the post. This data, and the relevant original file, were stored in a database for later coding and analysis. Data was collected for this study over a 12-week period (December 2022 – February 2023). Using this method, the database contained 1,016 relevant posts. These posts enjoyed an impressive viewership: during this three-month period, these extremist and mostly violent posts were viewed over 3,371,651 times. The average number of views per item is high (approximately 3,600 views per item), but so is the variance: some of the posts had very few views, while some enjoyed over 50,000 views.

Findings

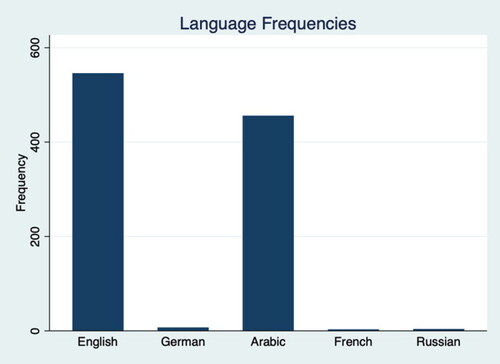

Our monitoring revealed several channels posting terrorist and violent extremist items on TamTam during our survey period. These included extreme right wing channels and two Jihadi IS-related channels. So as not to promote or increase the reach of these channels and their extremist content by the researchers chose to omit the name of the specific channels. There were 546 posts (53.25%) in extreme right wing channels and 475 (46.75%) in Jihadi channels. As presented in , the posts were primarily in English and Arabic.

The extreme right wing posts were primarily in English, while the Jihadi posts were primarily in Arabic, as noted in .

Table 1. Channel and languages.

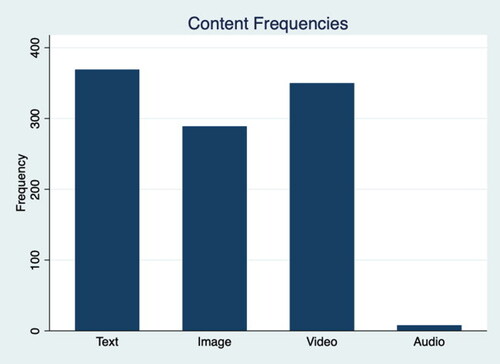

The posts included various content types, with a clear preference for text messages, images, and videos (see ).

The post format varies across channels and types of groups: As seen in , the Jihadi channels clearly prefer visual formats (videos and images) over texts and audio. Conversely, the extreme right wing channels varied: while the most active channel, ERW Channel 5, prefers text messages, the other six channels appear to prefer visual formats.

Table 2. Channels and content types.

Like all social media, the value of the posts relies on reach or exposure. As our database included the number of views per item, we were able to examine the exposure of each post and compare between channels, content type, and ideology. While it is not currently possible to assess how many times the content was viewed by unique users, the total number of views during out surveyed 3-month period was 3,371,651 views. Given the violent nature of this content, the high number of total views is quite concerning. While the total number of views was large, the viewership varied across the groups, as noted in . While some posts enjoyed over 56,000 views, others had none. The most significant difference was between the Jihadi posts (with very high viewership) and the extreme right wing posts (with relatively low viewership).

Table 3. Viewership by groups.

The Jihadi posts on TamTam attracted more viewership, with posts from channels claiming to be affiliated with the Islamic State totaling more than 2.42 million views and an average of nearly 7,000 views per posting. This is rather alarming viewership considering the type of content presented (to be explored in later sections). Comparatively, the postings in channels espousing an extreme right wing ideology tended to attract fewer views (total number of views were several thousand). Notably, a majority of the Jihadi posts (98%) were in Arabic, presumably catering to Arabic-speaking audiences. Nevertheless, given that the majority of these posts are visual in nature, comprising video clips and images, the intended target audience may be broader.

The use of TamTam is very different when comparing Jihadist channels and extreme right wing channels. Based on the findings of this study, Jihadists employ TamTam channels as repositories of visual material, particularly video clips produced by ISIS. Video clips included propaganda videos such as “Flames of War,” gruesome footage of executions featuring beheadings, mass shootings, and burning of victims, training videos featuring children, youth, and foreign fighters, speeches of leaders such as Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and fighting scenes. The placement of these videos on TamTam is a tactic employed by ISIS to relocate their digital libraries to more permissive platforms, ultimately using them as “virtual dead drops.”Footnote31 As a result, these channels can serve as online archives, providing end users with the ability to access files with any internet-capable device from any location. At its simplest, it is a secure virtual space that any user can access via his/her browser or a desktop application like TamTam. Jihadists have already used several free online archives, and TamTam appears to be an additional avenue to store and distribute their materials safely.

The use of TamTam channels by individuals and groups espousing an extreme right ideology differs from Jihadi groups. For instance, some of the popular channels among the extreme right primarily serve as a platform for social interaction, where users communicate via text messages. On one popular channel, ERW Channel 5, these interactions accounted for 93% of the collected data. Other channels espousing extreme right wing beliefs posted images and videos related to previous extreme right wing attacks. One popular subject was the Christchurch, New Zealand attack which resulted in the deaths of 51 people. This attack was perpetrated and broadcast live on Facebook by Brenton Tarrant. Other posts on these channels encompassed a broad spectrum of content with racist, anti-Semitic, anti-LGBT, white supremacist, and neo-Nazi undertones. Some of the images feature pictures of Hitler, SS troops, Nazi memorabilia, and Nazi propaganda items.

Following the precedent set by recent studies examining violent themes in online content, we conducted a content analysis to assess the prominence of verbal and visual violence in the posts.Footnote32 Verbal Violence was defined as the use of terms and phrases which are associated with the following perceptual and behavioral aspects of violence: (a) support, praise, and legitimization of violent practices; (b) indicating a willingness to use violence; (c) using violent terms for describing a social or personal situation; and (d) indicating planning and coordinating efforts to execute violent acts. Visual violence was defined as the use of pictures or visuals of (a) use of violence; (b) use of weapons; and (c) presentation of victims of violence. To ensure consistency in coding of verbal and visual violence, the authors independently coded the material and then met to discuss any differences in assigned codes. The authors had a near identical result. The prominence of violence in our sample was high: 39.3% of the postings included verbal violence and 44.9% included visual violence. However, there are differences across groups and types, as noted in .

Table 4. Visual and verbal violence by channel.

Most of the channels included visual and verbal content but some were clearly more eager to distribute such materials. For example, 72% of the posts produced by the channel claiming affiliation with the Islamic State included visual violence. These posts were primarily in the form of video executions, including beheadings, children shooting handcuffed prisoners, or depictions of killed or injured victims. Similarly, 55% of the posts produced by Jihadist Channel 1 included visual violence and very often of extreme acts of violence. These two channels espousing Jihadi beliefs also more frequently used verbal violence (70% of Jihadist Channel 2 posts and 65% of the Jihadist Channel 1 posts). While the Jihadist affiliated channels had a relatively consistent high percentage of posts which included visual and verbal violence, there was significant variance between the channels espousing extreme right wing beliefs. For example, one channel, ERW Channel 5, posted relatively few pieces of content involving visual (17%) or verbal violence (4.8%), while other channels, such as ERW Channel 2, had higher proportions of items with both visual and verbal violence.

highlights that both visual and verbal violence are more prevalent in channels espousing Jihadist beliefs than those channels espousing extreme right wing beliefs. This disparity is likely attributable to the distinct approaches adopted by these two groups in utilizing the TamTam platform. Users that espouse extreme right wing beliefs appear to use TamTam as a social media platform, facilitating communication, exchanging ideas and notes, responding to events, and sharing information. The members of these groups originate from diverse countries, bringing their individual experiences to the table and forging connections with international networks. This emphasis on social interaction and communication among these channels may help to explain the lower incidence of verbal and visual violence in the posts.

Table 5. Visual and verbal violence by ideology.

Conversely, Jihadists primarily use the platform as a means of archiving and sharing visual materials produced by the Islamic State, primarily in Arabic. Given that channels espousing Jihadist beliefs appear to view the platform through this practical lens (storage & dissemination), devoid of interaction, exchange, or social relationships, they place a greater emphasis on verbal and visual violence as a tool to propagate their extreme beliefs, a finding consistent with other studies.Footnote33

While difference in the presence of visual and verbal violence was noted, the question remains: is the prevalence of verbal or visual violence related to exposure and reach? When analyzing our collected data, the average number of views per item containing visual violence was 5,182, compared to an average of 1,742 views per item with no visual violence. As such, it was noted that posts including visual violence had nearly three-times the viewership of posts without. Similar findings were noted when examining the impact of verbal violence. Of the posts collected, items containing verbal violence had an average of 5,305 views, compared to 1,357 views for items without.

Conclusion

TamTam is a messaging platform developed by Mail.Ru Group, which is one of the largest internet companies in Russia. With millions of users, TamTam has become a popular messaging app, providing fast, simple, and secure communication. One of the features that sets TamTam apart is its security. TamTam is built around state-of-the-art encryption technology, which ensures that all user data is encrypted and secure. This means that users can communicate with confidence, knowing that their conversations are private. This secure and safe environment attracts, as with many other social media platforms, radical, violent and terrorist actors. In its online “General Requirements to Messages in Channels and Chats” TamTam operators declare that the messages on TamTam must not:

Promote and call for violence and cruelty, committing suicide and other illegal and immoral acts.

Propagate extremism, terrorism, excite hostility based on racial, ethnical or national identity, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, religious opinions, age, limited physical or mental abilities or diseases.

Contain images and video of low quality, obscene, pornographic, images of dead people and animals, with marks of violence, cruelty and other scaring or aesthetically unacceptable images.

Contain other information of an illegal nature.

Does TamTam apply its regulation? In 2022, TamTam removed 18 channels endorsing neo-Nazi accelerationism and acts of terrorism. The channels which were previously located on Telegram posted a series of guides on how to make explosives, the manifestos of several white supremacist mass shooters, videos from several neo-Nazi groups, including the Atomwaffen Division, the National Socialist Order, The Base, and Feuerkrieg Division, and video clips promoting acts of terrorism. While TamTam removed this content, as our study reveals, the platform fails or has not attempted to remove all terrorist and violent extremist contents. It is clear that for some of these groups TamTam became a useful storage and dissemination center while for others it is forum for the exchange of information and social interaction. Moreover, TamTam already declared in 2019 that it blocked hundreds of channels after they were used by the Islamic State (IS) to claim responsibility for the London Bridge terrorist attack that claimed the lives of two Londoners. Yet, as the results of this study show, the IS and other extremist content on TamTam still exists.

Extremist supporters on other online platforms have noted the continued presence of extremist content on TamTam, and its deliberate or unintentional acceptance of this content. A Telegram user, known for posting extremist material, declared in November 2022 that the “Great Migration to TamTam has begun,” suggesting that others move to TamTam because the platform “is a telegram clone without all of the censorship of telegram” [sic].Footnote34 In the same month, a TamTam user posted that “the group of channels was moving from Telegram to TamTam because the latter does not remove content.”Footnote35 This perceived permissiveness of the platform for extremist content may encourage others to migrate to TamTam.

More generally, TamTam and the trends noted in this paper are typical of the dynamic movement of terrorists and violent extremists online. Countermeasures such as surveillance and deplatforming on many platforms, have prompted extremist actors to search for more permissive environments to propagate their extremist content, interact, and make connections. These mass migrations have been common in recent years, with actors moving from Twitter to a more permissive platform such as Telegram. The recent movement to TamTam is the most recent instance of this online migration trend.

The findings of this research regarding migration generally, and TamTam in particular, highlight the pressing need for new policy solutions to combat the dissemination of extremist content. The persistent migration of extremists to new platforms poses a significant challenge for intelligence, law enforcement, and counterterrorism agencies. Breaking the cycle of cat-and-mouse chases across platforms requires the development of a new strategy. Specifically, to break the cycle of abuse-response-migration, a long-term preemptive strategy based on close collaboration between states and social media developers is needed. Such a collaborative effort between policymakers and developers could identify emerging trends in the next generation of platforms and incorporate institutional safeguards against abuse in their planning and design. Without such a coordinated response, no significant progress can be made in curtailing the production and propagation of extremist content. Historical precedents show that even if TamTam fully enforces its own regulations and removes content that violates its terms of use, violent extremists will merely relocate to a more permissive space. Policymakers and platforms must be ahead of the extremists to effectively combat their activities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Gabriel Weimann, Terror on the Internet: The New Arena, The New Challenges (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2006); Gabriel Weimann, Terror in Cyberspace: The Next Generation (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006); Gabriel Weimann, “The Evolution of Terrorist Propaganda in Cyberspace,” in The SAGE Handbook of Propaganda, ed. Paul Baines, Nicholas O’Shaughnessy, and Nancy Snow (London: SAGE, 2020), 579–94; Scrivens Ryan, Gill Paul, and Maura Conway, “The Role of the Internet in Facilitating Violent Extremism and Terrorism: Suggestions for Progressing Research,” in The Palgrave Handbook of International Cybercrime and Cyberdeviance, ed. Thomas Holt and Adam Bossler (New York: Springer, 2020), 1417–35.

2 Gabriel Weimann and Natalie Masri, “Research Note: Spreading Hate on TikTok,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 46, no. 5 (2020): 752–65.

3 Weimann, Terror in Cyberspace: The Next Generation; Scrivens et al., “The Role of the Internet in Facilitating Violent Extremism and Terrorism: Suggestions for Progressing Research.”; Brian Fishman, “Crossroads: Counter-Terrorism and the Internet,” Texas National Security Review 2, no. 2 (2019): 82–100; Charlie Winter, Peter Neumann, Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Magnus Ranstorp, Lorenzo Vidino, and Johanna Fürst, “Online Extremism: Research Trends in Internet Activism, Radicalization, and Counter-Strategies,” International Journal of Conflict and Violence 14, no. 2 (2020): 1–20; and John Vacca, ed. Online Terrorist Propaganda, Recruitment, and Radicalization (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2019).

4 Gabriel Weimann, “How Modern Terrorism Uses the Internet,” United States Institute of Peace USIP) Special Report (March 13, 2004), https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/sr116.pdf.

5 Bruce Hoffman and Jacob Ware, “Are We Entering a New Era of Far-Right Terrorism?,” War on the Rocks (November 27, 2019), https://warontherocks.com/2019/11/are-we-entering-a-new-era-of-far-right-terrorism/.

6 Cited by Yuki Noguchi, “Tracking Terrorists Online,” Washington Post, Washingtonpost.com Video Report (April 19, 2006), https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/discussion/2006/04/11/DI2006041100626.html.

7 J.M. Berger, “The Metronome of Apocalyptic Time: Social Media as Carrier Wave for Millenarian Contagion,” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, no. 4 (2015): 61–71; Jytte Klausen, “Tweeting the Jihad: Social Media Networks of Western Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 38, no. 1 (2015): 1–22; Gabriel Weimann, New Terrorism and New Media (Washington, DC: Commons Lab of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, 2014), https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/publication/STIP_140501_new_terrorism_F.pdf.; and Gabriel Weimann, “Why Do Terrorists Migrate to Social Media?,” in Violent Extremism Online: New Perspectives on Terrorism and the Internet, ed. Anne Aly, Stuart Macdonald, Lee Jarvis, and Thomas Chen (New York: Routledge, 2016): 67–84.

8 Maura Conway, Moign Khawaja, Suraj Lakhani, Jeremy Reffin, Andrew Robertson, and David Weir, “Disrupting Daesh: Measuring Takedown of Online Terrorist Material and Its Impacts,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 42, no. 1-2 (2019): 141–60; Baharat Ganesh and Jonathan Bright, “Countering Extremists on Social Media: Challenges for Strategic Communication and Content Moderation,” Policy & Internet 12, no. 1 (2020): 6–19.

9 EUROPOL, “Europol and Telegram Take on Terrorist Propaganda Online,” (2019), https://www.europol.europa.eu/media-press/newsroom/news/europol-and-telegram-take-terrorist-propaganda-online.

10 Richard Rogers, “Deplatforming: Following extreme Internet celebrities to Telegram and alternative social media,” European Journal of Communication 35, no. 3 (2020): 213–29, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0267323120922066 and Bennett Clifford. “Migration Moments: Extremist Adoption of Text-Based Instant Messaging Applications,” Special Report by Global Network on Extremism and Technology (2020), https://gnet-research.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GNET-Report-Migration-Moments-Extremist-Adoption-of-Text%E2%80%91Based-Instant-Messaging-Applications_V2.pdf.

11 Mikhail Zelensky, “Some Messenger Called ‘TamTam’ Is Trying to Replace Telegram in Russia. What the Heck Is It?,” Meduza (April 18, 2018), https://meduza.io/en/feature/2018/04/17/some-messenger-called-tamtam-is-trying-to-replace-telegram-in-russia-what-the-heck-is-it.

12 Ibid.

13 Mitch Prothero, “ISIS Supporters Secretly Staged a Mass Migration from Messaging App Telegram to a Little-Known Russian Platform after the London Bridge Attack,” Insider (December 3, 2019), https://www.insider.com/isis-sympathisers-telegram-tamtam-london-bridge-2019-12.

14 Jeff Stone, “Islamic State Propaganda Efforts Struggle after Telegram Takedowns, Report Says,” Cyberscoop (July 28, 2020), https://cyberscoop.com/islamic-state-propaganda-telegram-europol/.

15 Counter Extremis Project, “Extremist Content Online: TamTam Edition” (November 22, 2022), https://www.counterextremism.com/press/extremist-content-online-tamtam-edition.

16 “TamTam Deletes Channels Promoting Neo-Nazi Accelerationism and Terror,” Homeland Security Today (December 5, 2022), https://www.hstoday.us/subject-matter-areas/counterterrorism/tamtam-deletes-channels-promoting-neo-nazi-accelerationism-and-terror/.

17 Charlie Winter, “The Great Migration: Recent Accelerationist Efforts to Switch Social Media Platforms,” VOX-Pol Blog (January 18, 2023), https://www.voxpol.eu/the-great-migration-recent-accelerationist-efforts-to-switch-social-media-platforms/. Winter reports that “In the first week of December 2022, TamTam had caught onto what was happening and started to aggressively disrupt the migration.” Yet, our scan of TamTam revealed that terrorists and extremists are still very prevalent and active on this platform.

18 See “TamTam Chats and Channels Regulations,” https://about.tamtam.chat/en/regulations/.

19 Maura Conway, “Online Extremism and Terrorism Research Ethics: Researcher Safety, Informed Consent, and the Need for Tailored Guidelines.” Terrorism and Political Violence 33, no. 2 (March 24, 2021): 367–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2021.1880235; Stephane Baele et al., "The Ethics of Security Research: An Ethics Framework for Contemporary Security Studies." International Studies Perspectives 19, no. 2 (2018): 105–27; Peter King, “Building Resilience for Terrorism Researchers,” VOX-Pol Blog (September 19, 2018); Michael Krona, “Vicarious Trauma from Online Extremism Research: A Call to Action,” GNET Insights (March 27, 2020(; Adrienne Massanari, “Rethinking Research Ethics, Power, and the Risk of Visibility in the Era of the Alt-Right Gaze,” Social Media and Society 4 no. 2 (2018): 1–9; Joe Whittaker, Building Secondary Source Databases on Violent Extremism: Reflections and Suggestions (Washington, DC: Resolve Network, 2019); Charlie Winter, Researching Jihadist Propaganda: Access, Interpretation, and Trauma (Washington, DC: Resolve Network, 2019).

20 Baele et al., “The Ethics of Security Research,” 115; King, “Building Resilience for Terrorism Researchers”; Krona, “Vicarious Trauma from Online Extremism Research.”

21 Baele et al., “The Ethics of Security Research,” 115–6.

22 Ibid., 112.

23 David Décary-Hétu and Judith Aldridge, "Sifting through the Net: Monitoring of Online Offenders by Researchers." European Review of Organised Crime 2, no. 2 (2015): 122–41.

24 Ibid., 134.

25 Ibid.

26 Julia Ebner, Going Dark: The Secret Social Lives of Extremists (London: Bloomsbury, 2021).

27 Conway, “Online Extremism and Terrorism Research Ethics: Researcher Safety, Informed Consent, and the Need for Tailored Guidelines,” 372–4; Kerstin Eppert, Lena Frischlich, Nicole Bögelein, Nadine Jukschat, Melanie Reddig, and Anja Schmidt- Kleinert, Navigating a Rugged Coastline: Ethics in Empirical (De-)Radicalization Research (Bonn: CoRE – Connecting Research on Extremism in North Rhine-Westphalia, 2020).

28 Ahmad Shehabat, Teodor Mitew, and Yahia Alzoubi. “Encrypted Jihad: Investigating the Role of Telegram App in Lone Wolf Attacks in the West,” Journal of Strategic Security 10, no. 3 (2017): 27–53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26466833; Cliona Curley, Eugenia Siapera, and Joe Carthy, “Covid-19 Protesters and the Far Right on Telegram: Co-Conspirators or Accidental Bedfellows?,” Social Media and Society 8, no. 4 (2022), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/20563051221129187; Valentin Peter, Ramona Kühn, Jelena Mitrović, Michael Granitzer, and Hannah Schmid-Petri. “Network Analysis of German COVID-19 Related Discussions on Telegram,” in Natural Language Processing and Information Systems, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, ed. Rosso et al., vol. 13286 (Springer, 2022), https://ca-roll.github.io/downloads/Telegram_Sampling_and_Network_Analysis.pdf.

29 Samantha Walther and Andrew McCoy. "US Extremism on Telegram." Perspectives on Terrorism 15, no. 2 (2021): 100–24; Curley et al., “Covid-19 Protesters and the Far Right on Telegram: Co-Conspirators or Accidental Bedfellows?.”

30 Peter et al., “Network Analysis of German COVID-19 Related Discussions on Telegram.”

31 Gabriel Weimann and Asia Vellante, “The Dead Drops of Online Terrorism:

How Jihadists Use Anonymous Online Platforms,” Perspectives on Terrorism 15 (2021): 163–77.

32 Arie Perliger, Catherine Stevens, and Eviane Leidig. "Mapping the Ideological Landscape of Extreme Misogyny," ICCT Research Paper (2023), https://www.icct.nl/sites/default/files/2023-01/Mapping-the-Ideological-Landscape-of-Misogyny%20%282%29.pdf.

33 Adam Badawy and Emilio Ferrara, “The Rise of Jihadist Propaganda on Social Networks,” Journal of Computational Social Science 1 (2018): 453–70, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42001-018-0015-z; Philip Baugut and Katharina Neumann, “Online Propaganda Use during Islamist Radicalization,” Information, Communication & Society 23, no. 11 (2020): 1570–92, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1594333 ; and Miron Lakomy, “Recruitment and Incitement to Violence in the Islamic State’s Online Propaganda: Comparative Analysis of Dabiq and Rumiyah,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 44, no. 7 (2021): 565–80, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1057610X.2019.1568008.

34 Quote taken from Telegram channel on November 29, 2022.

35 Counter Extremism Project (CEP), “Extremist Content Online: TamTam Edition,” ZCEP Report (November 18, 2022), https://www.counterextremism.com/press/extremist-content-online-tamtam-edition.