Abstract

Despite its prominence in radicalization models, we lack an integrated understanding of how, when, and to what extent identity causes or prevents extremist radicalization. In this systematic review we therefore inventoried the various conceptualizations of identity as determinant of extremist radicalization in quantitative research, and evaluated their effect. Synthesis of 75 studies revealed that the majority examined social and contextual identity concepts, around a quarter investigated identity needs and motives, and only two tested personal and developmental identity concepts. While the link between some identity concepts and extremism enjoy good empirical support, many are in need of further scrutiny.

Due to its far-reaching impact on people’s social and personal functioning, identity is ascribed a key role in radicalization and its prevention.Footnote1 On the one hand, identity helps us establish and maintain relationships, directs our behavior toward groups and communities that we do and do not belong to,Footnote2 and influences our societal engagement.Footnote3 On the other hand, the personal sense of who we are and who we strive to be guides us in shaping our life paths, including choosing an occupation and adopting or developing an ideology.Footnote4 In addition, identity provides us with a sense of purpose, significance, meaning, self-worth, and belongingFootnote5; and reconsidering who we are can help us recover from traumatic life-changing experiences,Footnote6 ultimately affecting our general well-being.Footnote7 Consequently, when problems with identity arise, peoples’ social and personal functioning can be affected, having all kinds of harmful consequences,Footnote8 including, potentially, radicalization.

Indeed, apart from perceived relative deprivation, identity-related issues are one of the two most recurring factors in theoretical models attempting to explain radicalization.Footnote9 Radicalization is commonly conceptualized as a transformational process by which individuals gradually accept, support, or engage in violent behaviors in support of ideological causes,Footnote10 with a recent focus on distinguishing between cognitive versus behavioral radicalization.Footnote11 Arguably, in nearly every phase of the radicalization process identity plays an important role. However, theoretical models diverge in their assumptions about how identity functions in the process and at which stage. Some modelsFootnote12 propose that, apart from the subjective perception of relative deprivation and social injustice, the process of radicalization arises from threats to one’s social identity. According to a number of other models,Footnote13 some form of personal crisis (e.g. an identity crisis) serves as a “cognitive opening” that onsets the process of radicalization, causing individuals to challenge their previous (world) view and to seek out groups or ideological frameworks that facilitate answers and, ultimately, identity-construction. Because extremist groups provide a sense of meaning through clear-cut, unambiguous ideologies, they are considered particularly attractive. Along with identification with an extremist group, individuals are thought to adopt the group’s norms and values: the radicalization process is in full operation.Footnote14 And once the group membership and ideological dedication become central to the individuals’ identity, they may even be willing to exhibit violence on behalf of it (i.e. extremist actions), which is the supposed final stage of radicalization.Footnote15 Finally, identity was also proposed as a key element for de-radicalization: shifts in life priorities, psychological and physical well-being, or group dynamics, can lead to changes in identification, such that individuals no longer define themselves by the extremist group or ideology,Footnote16 thereby reducing the risk of being triggered to act on behalf of said group or ideology.

However, despite its prominent role in various theoretical models on radicalization, we do not have an integrated idea of whether and when identity causes, reduces, or prevents radicalization.Footnote17 In particular, what is missing from the literature is an evidence-based overview of the putative effect of identity on extremist radicalization, an absence that is likely routed in a number of complications.

Complications in Research on Identity and Extremist Radicalization

An important underlying obstacle to understanding the putative effect of identity on extremist radicalization is the complexity of identity as a construct and the wide variety of theoretical perspectives from which it can be approached. In general terms, identity refers to the idea people have of who they are, based on the multiple affiliations or commitments that they have (e.g. ethnic, religious, political, sexual, vocational, relational etc.) and how subjectively meaningful and essential they are to their self-understanding.Footnote18 Depending on the theory, however, the term identity can refer to very different things that operate at different conceptual levels. To help categorize the various theories and their approach to identity, Vignoles, Schwartz, and LuyckxFootnote19 proposed three broad theoretical approaches: social and contextual perspectives, personal and developmental perspectives, and perspectives on identity needs and motives.

First, from the perspective of social and contextual identity theories, the concept of identity can refer to the group memberships a person finds meaningful to their sense of selfFootnote20 or the cultural norms, values and beliefs they have internalized.Footnote21 Within these theories, people’s identity is considered highly responsive to changes in social context and is regarded the core ingredient to all intra- and intergroup dynamics, including nationalism, xenophobia, dehumanization, intergroup violence, and genocide.Footnote22 Second, theories that approach identity from a personal and developmental perspective describe identity as people’s personal idea of who they are, including their goals, values, beliefs, and world view, and are concerned with the process by which they actively form and reconsider this idea over the course of their lives.Footnote23 The particular way in which people develop their personal identities is, in turn, thought to determine whether or not they are successfully adapted to both the smaller and bigger life challenges, ultimately effecting both their personalFootnote24 and socialFootnote25 functioning. Finally, there is a category of theories that focus on the needs and motives underlying identity processes which offer an explanation as to why maintaining and defending, revising and constructing a social or personal identity is important to people in the first place.Footnote26 According to these theories, a range of psychological needs motivates people to identify with those groups, ideologies, characteristics, social roles etc. which have the capacity to fulfill them. Moreover, to maintain a positive sense of self (i.e. an identity that fulfills one’s psychological needs), these theories propose that in response to factors that threaten their identity, people engage in identity management behaviors, including reconstruction and defense mechanisms.

Considering the variety of theories, the scientific literature on identity is described as vast and fragmented to the extent that scholars from one theoretical perspective are oblivious of others.Footnote27 Unfortunately, this appears to seep through to research on identity and extremism, because efforts to understand the effect of identity on radicalization have emerged more or less independently from different scientific fields, such as forensic, social, developmental, and political psychology, as well as criminology, political science, and sociology. This fragmentation poses a challenge to integrating our knowledge regarding the link between identity and extremist radicalization.Footnote28

Another complicating issue in the literature on extremist radicalization is that, occasionally, terms referring to theoretically conceptualized identity problems are used arbitrarily. Among the many specific identity problems that have been suggested to cause extremist radicalization are: a perceived conflict between in- and outgroup,Footnote29 deep-seated uncertainties about the self and the world,Footnote30 failing at the developmental challenge of constructing an identity,Footnote31 or unsuccessful acculturation.Footnote32 However, scholars and practitioners seem to casually use terms such as “identity crisis,” “identity conflict,” “identity quest,” “the search for identity” and “identity struggles” interchangeably, neglecting possible theoretical distinctions between them. For instance, while identity crisis was originally conceptualized as the developmental challenge adolescents face during their transition from childhood into adulthood,Footnote33 occasionally, extremism scholars and practitioners seem to use the term as a general place-holder for identity-related issues or when referring to problems that are in fact specific to social and cultural identity concepts and processes.Footnote34 This inconsistency in the use of terms can lead to misunderstandings and the false impression that the impact of specific identity problems is well-established in the scientific literature,Footnote35 while this might not actually be the case.

As a consequence of the complexity of identity as a construct, the fragmentation of the literature studying it, as well as the arbitrary use of specified identity concepts as umbrella terms, our insight into the role identity plays within the process of extremist radicalization is largely unintegrated.Footnote36 Without understanding the role of different identity concepts in the process of extremist radicalization, we cannot learn how and when we can embrace its strengths, whilst also managing its damaging impact on individuals and groups.Footnote37 Ultimately, this lack of understanding hinders us from effectively tackling identity-related issues in prevention and intervention programs.Footnote38 To start with, we need an overview of how identity has been conceptualized and examined in empirical research on violent extremism, including what identity concepts have been studied extensively and which concepts have received less attention. Moreover, we need to establish which identity concepts are empirically linked to violent extremism and which are not.

The Current Study

In this study, we systematically reviewed quantitative scientific research that tested the role of identity in increasing or reducing violent extremist attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. The objective of this study was twofold. First, we aimed to inventory the various conceptualizations of identity that have been studied as predictors of violent extremism in the quantitative literature. Second, based on the empirical evidence that we found, we aimed to record the extent to which each identity concept predicts extremist radicalization. Due to the heterogeneity of study designs, sample populations, ideologies, outcome variables, and – most importantly – the various identity concepts, a meta-analysis was not suitable, resulting in a narrative synthesis instead. In order to organize the identity concepts that emerged in this review, we categorized them into the three broad categories of identity theories introduced earlierFootnote39: social and contextual perspectives on identity, personal and developmental perspectives on identity, and perspectives on the needs and motives underlying identity processes.

Method

Search Strategy and Data Sources

To conduct this systematic literature review, we used the PRISMA protocol, an evidence-based reporting guideline for systematic reviews.Footnote40 To identify search terms we conducted pilot searches with terms from three broad categories: violent extremism, identity, and terms referring to empirical research. Since we wanted to include all conceptualizations of identity (sensitivity), but avoid literature on identification documents and policies (specificity), we decided to include the single search term “identity” (identit*) without further determination (i.e. social identity, identity formation, identity threat, etc.). Based on the pilot searches we formulated search strings for seven databases: Scopus, Psycinfo, Criminal Justice Abstracts, APA PsycArticles, Psychology and Behavioral Science Collections, ProQuest, and Web of Science. These databases were chosen because they cover research in psychology and criminology, two disciplines in which research on radicalization is conducted at the individual level. An example of a database-specific search string that was used in this review is provided in the appendix of this paper. If the database’s settings allowed it, we restricted the search to title, abstract, and keywords. The search was carried out on March 23rd 2020 and resulted in 4651 documents.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were considered eligible when they met the following inclusion criteria:

Document type. Only peer-reviewed articles published in a scientific journal were included in this review.

Outcome measure. As a number of scholars have stressed,Footnote41 any ideology is fit for radicalism, making the amount of potentially radical attitudes, intentions, and behaviors virtually endless. In order to distinguish extremism from widely-studied concepts related to radicalization (e.g., including racism, xenophobia etc.), we therefore restricted the included literature to studies that implement indicators of violent extremism as outcome variable. Derived from McCauley and Moskalenko’sFootnote42 two-pyramid model of radicalization that distinguishes between cognitive and behavioral extremism, we considered studies eligible if the outcome variable was conceptualized as a) violent extremist attitudes and beliefs (e.g., support for political violence and extremist groups or wanting to be or identifying as a member of a violent extremist group), b) violent extremist intentions (i.e., intending to use violence to achieve political goals in the future), and c) violent extremist behaviors (i.e., using or having used violence to achieve political goals in the past, e.g. being convicted of violent extremist crimes or reporting the use of past extremist violence).

Predictive measure. In this review, we only included studies that examined identity as independent variable, either as main predictor or as co-variable. As long as there was variation on the independent variable, we considered various identity operationalizations appropriate, such as the extent of identification (e.g., with a specific group, ideological goal, physical feature, personality trait or skill), indications of identity development (e.g., identity processing styles or developmental identity status) or the extent to which individuals experienced identity-related issues and needs (e.g., feelings of uncertainty about one’s own identity). Studies that used proxies for identity, such as single-choice questions on ethnicity or nationality were excluded from this study because group-membership does not necessarily equate with identity, unless individuals derive social and personal meaning from it relevant for their self-definition.Footnote43

Aggregation level. In order to avoid aggregation bias, which can lead to the false conclusion that what is true for the group must be true for the individual,Footnote44 we only included studies that measured both dependent and independent variables at the individual level. Studies on supra-individual level, for example on the supposed (but not individually assessed) identity crisis of a specific tribe and its effect on violent riots (also not individually assessed) in a country, were not included in this review.

Empirical studies. Only empirical studies were included. Literature reviews, article or book reviews, and theoretical papers that did not use original data were excluded.

Full-text availability. Articles were only included when full-texts were accessible to the researchers.

Language. Due to language constraints, only articles in English, Dutch, and German were included.

Selection of the Literature

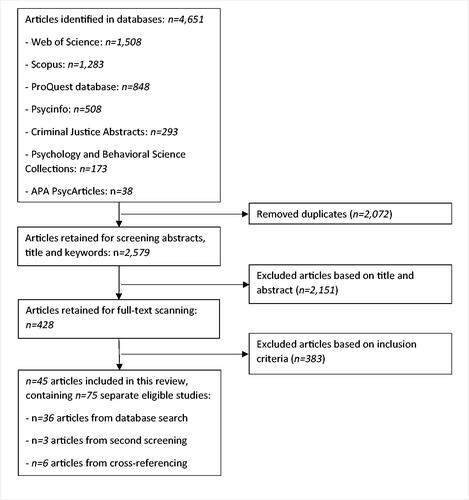

The different steps in which the literature was reviewed and selected are presented in . After the removal of duplicates, the first author and a research assistant independently screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining 2572 documents for eligibility, consulting the first seven inclusion criteria. The selections of both researchers were compared and any disagreements reviewed. If it was unclear whether an article was eligible given the information provided in its title and abstract, an article was included for full-text scanning. Ultimately, the comparison between first and second screening resulted in 3 additional eligible articles.

In a second step, the full-text of each article was scanned for eligibility, checking for the same seven inclusion and exclusion criteria. Given the quantity of screened-in scientific articles, we decided to confine the literature review to quantitative studies only, adding an eighth and final inclusion criterion:

8. Study design. Only quantitative studies employing (semi-) experimental, longitudinal, interventional, observational, or mixed-method designs that utilized quantitative data were included.

Removing all articles not in line with the eight inclusion criteria and checking the full-texts for relevant cross-references resulted in the final selection of 45 eligible articles.

Results

Characteristics of the Literature

presents an overview of the articles and studies included in this systematic review, along with their main characteristics. The 45 selected articles in this review contained 75 eligible studies. While all included studies relied on quantitative analyses, four employed a mixed-method approach, such that data derived through interviews, news articles, and case files were first coded and then statistically analyzed. Twelve studies made use of an experimental research design, three of a longitudinal design, and two studies were interventional.

Table 1. Overview of the main characteristics of the included articles and studies.

The reviewed studies were conducted in more than 50 different countries across the globe, including Europe, the Middle East, South East Asia, Oceania, North America, South America, and Africa. With 15 studies, the USA was represented most, followed by Spain (n = 10). The studies were conducted among a variety of sample populations, including members of ethnic or religious minority groups (n = 33), members of ethnic majority groups (n = 12), university students (n = 18), adolescents and young adults (n = 8), individuals recruited through online crowdsourcing companies, such as Amazon Mechanical Turk (n = 13), members of social media groups (n = 6), individuals with specific political affiliations (n = 8), terrorist suspects (n = 3), terrorist detainees (n = 2), and football hooligans (n = 1). Overall, the sample sizes were sufficient, with an average of 584 participants per study. Only six studies had small sample sizes with between 26 and 66 participants, due to limited access to the sample population (i.e. football hooligans, terrorist suspects or detainees). The average age per sample ranged from 15 to 46 years and the majority of samples consisted between 40 to 60% of men. In twenty studies (mostly involving university students), the sample consisted to more than 60% of females, while in only 12 studies (mostly involving terrorist suspects, individuals convicted for terrorism, members of religious communities, or football hooligans), more than 60% of the sample was male. Only four studies reportedly drew and examined representative samples.

Regarding the outcome variable, 36 of the reviewed studies tested violent extremist attitudes and beliefs, 44 tested violent extremist intentions, and 5 tested violent extremist behaviors, with 22 studies having examined more than one outcome variable. With regards to ideological focus, the majority of reviewed studies investigated Islamist or anti-Western forms of extremism (n = 31), closely followed by studies on right-wing extremism (including conservatism, right-wing authoritarianism, nationalism, anti-Islamism or other ethnicity-based extremism, n = 27). Seven studies examined left-wing extremism (including egalitarianism, left-wing authoritarianism, leftist anti-Zionism, pro-democracy and human rights extremism) and only one study addressed violent extremism in the name of Christianity. While seven studies examined several extremist ideologies, 20 studies assessed ideology-non-specific indicators of violent extremism.

Identity Concepts and Their Relation with Violent Extremism

presents an overview of all identity concepts that were used as predictor variable, and their direct and indirect relation with the three categories of violent extremism. The reviewed studies made use of a variety of identity concepts from different theories, with about half examining more than one identity concept in relation to violent extremism (n = 37). Following Vignoles and colleagues’Footnote90 suggestion, we categorized the identity concepts into (1) social and contextual perspectives on identity, (2) personal and developmental perspectives on identity, and (3) the needs and motives underlying identity processes. In the following sections, we present the various conceptualizations of identity the reviewed studies employed, how the concepts were operationalized, and their reported relation with violent extremism.

Table 2. Overview of all identity concepts examined in the reviewed studies and the amount of statistically significant positive (i.e. increasing, “+”), statistically significant negative (i.e. decreasing, “-”), and statistically non-sigificant (“0”) relations each was reported to have with violent extremist attitudes and beliefs, intentions, and behaviors. Effects in parentheses “()” indicate indirect or interaction effects with significant covariates (see ).

1) Social and Contextual Identity Concepts and Their Relation with Violent Extremism

The large majority of reviewed studies examining the putative effect of identity on violent extremism approached and defined identity from a social and contextual perspective. Although there is some conceptual overlap, we categorized the social and contextual identity concepts into: ingroup identification, identity fusion, civic identity, common-ingroup identification, dual versus separated identification, and cultural identity.

Ingroup Identification

Of the reviewed studies, 33 tested the putative risk effect of ingroup identification on violent extremist attitudes, intentions or behaviors. Ingroup identification or social identity refers to the meaning people derive from their various group memberships for their self-definition.Footnote91

In the reviewed studies, ingroup identification was operationalized as the extent to which participants identified with a specific social category, such as their nationality or country of heritage (n = 20), ethnicity (n = 8), political affiliation (n = 7), religion (n = 5), as well as their family, friends and college (x = 2). A large proportion of the reviewed studies on ingroup identification examined whether individuals who identify strongly with a subordinate (n = 10; e.g. ethnic or religious minority) or superordinate (n = 21; e.g. ethnic majority, nationality) ingroup are more likely to favor or (intent) to use extremist violence, than individuals who identify less strongly with their ingroup. In twelve studies, ingroup identification was only added as control variable to investigate whether other identity concepts have a comparatively stronger effect on violent extremism (see “Identity fusion”).

Overall, we found that ingroup identification is the most extensively investigated identity concept in the quantitative literature on extremism. Results regarding the link between ingroup identification and violent extremism vary, however, as it seems to depend on the presence of other factors. On the one hand, a substantial proportion of studies support the hypothesis that individuals who identify strongly with their (either subordinate or superordinate) ingroup are more likely to have violent extremist attitudes and intentions, particularly when they perceive it to be inherently superior to or negatively affected by outgroups. On the other hand, the large number of non-significant effects in studies that examined multiple identity concepts suggests that other factors, like identity fusion, may be better at predicting extremist radicalization than ingroup identification.

Identity Fusion

Twenty-three studies examined the putative risk effect of identity fusion on indicators of violent extremism. A fused identity is present when someone’s social identity takes over their personal identity, such that they form an equivalent or the sense of “being one” with the ingroup.Footnote92

In the reviewed studies, identity fusion was operationalized as the extent to which people have their personal identity fused with their country or nationality (10), political party (6), like-minded political supporters (2), political leader (7) or political cause (n = 1), as well as any social group of choice (n = 2) and group of friends (n = 2). Seven of the reviewed studies examined the effect of more than one form of identity fusion.

Overall, we found identity fusion to be the second most studied identity concept in quantitative research on violent extremism. The evidence strongly supports the hypothesis that identity fusion is a putative risk factor for extremist attitudes and intentions, such that fusion of people’s personal and social identity predicted higher support for and willingness to use violence for their ingroup or the realization of its political goals. Moreover, identity fusion was also found to have a stronger link with violent extremism than ingroup identification. Finally, five experimental studies provided support for the causal link between a salient fused identity and extremism, such that individuals whose fused identity was activated through perceived identity threats (e.g. threat of sharia law, threat to their personal identity, an increase in perceived relative deprivation) were significantly more likely to report extremist intentions.

Civic Identity

Five studies examined the putative risk effect of civic identity on extremist attitudes and intentions. Civic identity is described as the sense of oneself as a civic actor (i.e. someone that actively shapes civic life), and due to its fundamental link to particular social groups and communities and their position, function, and goals within society, can be considered a social and contextual identity concept.Footnote93

In the reviewed studies, civic identity was operationalized as the extent to which participants identified with being a political agent or activist, with their groups’ activist agenda, and with their personal political or religious cause.

Although very limited, the evidence indicates that, in line with the hypothesis, stronger identification with being a political agent or with one’s political goals is associated with a higher likelihood of having violent extremist attitudes and intentions. However, this effect was limited to individuals with post-conventional (versus conventional) moral reasoning, egalitarian (versus conservative) views, obsessive (versus harmonious) identification with their cause, experienced hatred, perceived identity threat, and strong identification with groups that pursue radical goals.

Common-Ingroup Identification

In ten of the reviewed studies it was tested whether identification with a common-ingroup is negatively linked to violent extremism. Common-ingroup identification refers to the extent to which members of different social groups sharing the same environment (e.g. various ethnocultural or religious groups within a single country) identify with a superordinate social category that overarches and encompasses their minor identities,Footnote94 such as citizenship or humanity.

In the majority of studies, common-ingroup identification was operationalized as the extent to which members of ethnic or religious minority groups identified with their country of residence or its mainstream society, and whether this was linked to a reduced likelihood of reporting extremist attitudes or intentions. Only two studies investigated whether national or continental identity also function as a radicalization-preventative common-ingroup identity among ethnic majority groups.

Taken together, there is some indication that common-ingroup identification may have a protective effect on violent extremism, such that members of ethnic and religious minority groups who identify strongly with a superordinate group (i.e. their country of residence or nationality) may be protected from developing extremist attitudes, intentions, and in one study even behaviors, a link that was partially explained by the absence of perceived ingroup superiority or negative attitudes toward outgroups. For members of ethnic majority groups, however, the opposite seems to be the case: two studies found that the supposed common-ingroup identification was positively linked to violent extremist attitudes and intentions, suggesting that members of ethnic majorities are less likely to perceive nationality as an overarching identity that encompasses minority outgroups and, instead, view it as their exclusive ingroup identity (see “Ingroup identification”).

Dual (versus Separated) Identification

Of the reviewed studies, nine examined the putative effect of dual or separated identities on indicators of violent extremism. A dual or integrated identity is of particular relevance for individuals who belong to more than one social group or category and commonly refers to the identification with both an ethnocultural minority ingroup and national mainstream society.Footnote95 A separated identity, on the other hand, is present when individuals do not combine the two identities but only define themselves through their ethnocultural group-membership.Footnote96

In the reviewed studies, dual and separated identity were measured separately, such that participants were asked to evaluate whether they identified equally strong with both their ethnocultural minority ingroup (e.g. their country of heritage, ethnicity or religion) and national mainstream society (i.e. dual identity) or preferred one over the other (i.e. separated identity). In two studies participants were additionally asked whether they perceived the two social identities as compatible versus conflicted.

Overall, only few studies report a positive effect of separated identities and incompatible dual identities on violent extremism. In these studies, members of ethnic or religious minority groups in Western countries reported stronger support for political violence and exhibited more violent behaviors when they clearly preferred their ethnocultural identity over their national mainstream identity or when they did identify with both social groups, but experienced them to be inherently conflicted. The majority of examined links between dual (versus separated) identity and indicators of violent extremism, however, proved non-significant.

Cultural Identity

Of the studies reviewed in this paper, six examined the effect of cultural identity on indicators of violent extremism. Cultural identity is defined as having chosen the cultural community to which one wants to belong and having internalized its values, beliefs, and principles as guidelines to function within it.Footnote97 In the reviewed studies, the conceptualization of cultural identity is similar to dual (versus) separated identification. However, instead of focusing on identification with two ethnocultural groups, four levels of acculturation describe how people manage their cultural identity when they partake in two cultures: integration (i.e. incorporating both mainstream and heritage cultures into one’s identity), assimilation (i.e. cultural identity solely based on mainstream culture), separation (i.e. cultural identity solely based on heritage culture), and marginalization (i.e. neither identifying with one’s culture of heritage nor with mainstream culture).Footnote98

Five of these studies operationalized cultural identity as the extent to which participants did (i.e. inclusion) or did not (i.e. alienation) identify with their culture of heritage or the mainstream culture of the country they reside in. Only one study examined all four levels of acculturation. While the majority of the studies on cultural identity hypothesized that members of minority groups with an alienated, separated or marginalized cultural identity have a higher tendency to exhibit violent extremist attitudes and intentions, four studies tested whether this was also true for members of a respective majority group.

Overall, the studies found that, among members of both ethnocultural minority and majority groups, cultural separation, marginalization, and alienation were positively linked to violent extremist attitudes and intentions, partially explained by moral justification, experiences of social exclusion (see “the need to belong”), general support for war, feelings of insignificance (see “the need for significance”), and experiences of discrimination. On the other hand, an integrated cultural identity was linked to lower support for political violence among members of an ethnic-religious minority who did consider their existence meaningful (see “need for significance”), suggesting a protective effect.

2) Personal and Developmental Identity Concepts and Their Relation with Violent Extremism

Only two of the reviewed studies approached identity from a personal and developmental perspective, each examining a different identity concept: identity diffusion and alternative identities. While identity diffusion has a thorough theoretical base, we did not find any specific theory underlying the concept of alternative identities. However, bearing similarities with the concept of possible future selves,Footnote99 as well as personal identity formation processes,Footnote100 we categorized it as a personal and developmental identity concept.

Identity Diffusion

One study examined the putative effect of identity diffusion on violent extremism. The concept of identity diffusion is based on Erikson’sFootnote101 model of psychosocial development and Marcia’sFootnote102 identity status theory and describes a state in which a person is neither committed to any form of identity nor actively trying to acquire one. Experienced as an identity crisis, identity diffusion evokes the sense of not knowing who one is, what one’s place and function is in the world, and what future directions to take in life.Footnote103

In the reviewed study, identity diffusion was operationalized as the combined extent to which an individual experiences a frequent change in life goals, sees themselves in different ways at different times, borrows tastes and opinions from other people, frequently picks up interests and drops them, and thinks that others cannot reliably predict how they are going to behave.

As hypothesized, the authors of this paper found a positive link between identity diffusion and attitudes in favor of three violent extremist ideologies, such that high school students with a diffused identity reported higher approval of extremist ideas from right-wing, left-wing, and Islamist ideologies than students with a clear and stable sense of self. This effect was partially explained by parenting style, including parental monitoring and parental consistence, as well as critical life events and academic performance.

Alternative Identities

One study examined the effect of adopting alternative identities on violent extremism. Alternative identities were operationalized as the extent to which participants had a balanced multi-facetted identity as opposed to an identity that is exclusively devoted to being a fighter for Islam. This construct was based on semi-structured interviews in which participants expressed what aspects in their lives they valued and what they planned to focus on in their futures, such as starting a family, working on their friendships, starting a business, or dedicating their life to the Islamist cause.

In line with their hypothesis, the authors found a direct negative link between alternative identities and violent extremist behaviors, such that terrorist detainees who had identities that trumped their jihadi identity were significantly less likely to support violent jihad, even if they were still committed to jihadi ideology. The adoption of alternative identities also mediated the negative effect of the detainees’ attitude toward the deradicalization program on their support for violent jihad. These findings suggest that even when convicted terrorists stick to their ideology, they may not resort to violence if they adopt alternative identities and goals.

3) Needs and Motives Underlying Identity Processes and Their Relation with Violent Extremism

In their effort to study the putative effect of identity on violent extremism, 16 studies approached identity from theoretical perspectives that focus on the psychological needs and motives underlying identity formation. Although Vignoles and colleaguesFootnote104 suggest that there may possibly be more identity needs, we reviewed studies that examined psychological needs and motives that have previously been empirically linked to identity formation, including uncertainty (i.e. the need for a sense of certainty), the need for significance and status, the need to belong, the need for self-esteem, and motivational types and dimensions. Since some studies operationalized these identity needs as need fulfillment, for the sake of interpretation, we reverse-coded them to represent need frustration.

Uncertainty

Six studies examined the putative effect of uncertainty on violent extremist attitudes or intentions, a concept that refers to a sense of uncertainty about oneself, one’s future, and the world, and that can be caused by societal (i.e. economic recessions, sociocultural shifts, reforms or war etc.) or personal (i.e. death of a loved one, disease, job loss etc.) crises.Footnote105

In the reviewed studies uncertainty was operationalized as the tendency of people to feel uncertain about a variety of things in life and across different situations (i.e. trait measure) and the extent to which participants currently feel uncertain about themselves, their place in the world, their future, or with regards to interacting with others (i.e. state measure).

Based on our review, there is only little support for the hypothesis that a sense of uncertainty about the self causes a higher willingness to engage in violent extremist action or to identify with violent extremist groups. The majority of studies did not find a significant link between uncertainty and violent extremism. When there was a positive link, however, other factors such as openness to experience, male gender, low education, identification with the US democratic party (but not the US republican party), as well as a combined riskiness factor (i.e. consisting of perceived individual and collective relative deprivation, procedural injustice, symbolic and realistic threat facing the ingroup, and exclusion from decision-making) played a significant role.

Need for Significance

In six of the reviewed studies it was examined whether a need for significance is positively linked to violent extremism. Need for significance describes the personal desire for having a purpose in life and being of importance to the world and others.Footnote106

In each of the five studies, the need for significance was operationalized differently: as the extent to which participants value having a high status, express megalomania, and view their existence as meaningful (reversed), as well as the combined measure of having a meaningful existence (reversed), the need to belong, a sense of self-esteem (reversed) and control (reversed), as well as experiencing humiliation, shame, hopelessness and anger.

There is some evidence to suggest that participants who feel insignificant and who have a strong desire for being highly respected and considered important by others are more likely to express support for violent extremist ideas and groups, especially when they also reported experiences of discrimination, when their moral judgment functioned at a post-conventional level, or when they strongly identified with being an activist (see “civic identity”).

Need to Belong

Seven studies examined the extent to which violent extremism is predicted by the need to belong. The need to belong represents people’s desire to be accepted by othersFootnote107 and is considered a fundamental human needFootnote108 that, when not satisfied, can cause high levels of distress.Footnote109

The need to belong was conceptualized as both state and trait measures. It was operationalized as the current desire to belong to a specific culture, as feeling lonely, being socially excluded or recalling a time when one has felt alienated (i.e. induced experimentally), and as the personal tendency to have strong sense of belonging to a community (reversed).

Evidence regarding the effect of the need to belong on violent extremism is mixed. In line with their hypotheses, a few studies found that individuals expressed significantly more support for Islamist terrorist organizations or a higher willingness to fight and die for their ingroup when they felt socially excluded or had a strong desire to belong to a community. Contrary to the hypothesis, however, in three other studies the need to belong was not linked to violent extremism, or – even more surprising – negatively associated to it. There is no overarching explanation as to what underlying factors could account for the differences in results.

Need for Self-Esteem

Four studies focused on self-esteem and its effect on extremist radicalization. While self-esteem typically describes a person’s overall subjective sense of personal worth or value,Footnote110 collective self-esteem refers to the sense of value people have based on their social identity.Footnote111

In the reviewed studies, the need for self-esteem was operationalized as the extent to which participants have a need for self-appreciation, derive a sense of self-esteem through their social identity (i.e. self-esteem; reversed), and believe that others perceive their social group as prestigious (i.e. perceived public group-esteem; reversed), as well as a combined measure of these facets (i.e. collective self-esteem, reversed).

Overall, there is some support for a putative risk effect of the need for self-esteem on violent extremism, but only when it operates at a collective level: individuals who believed that others view their social group not as prestigious and who had experienced discrimination were more likely to be sympathetic of violent extremism or to have violent extremist intentions. However, this effect does not seem to be robust, as the majority of studies did not find a link between the need for self-esteem on violent extremist attitudes, intentions, and behaviors.

Discussion

In this study, we systematically reviewed quantitative scientific research that examined the putative effect of identity on violent extremism. The background of this review was the observation that, although identity is considered one of the key factors in the process of radicalization,Footnote112 we lack an integrated view of how, when, and to what extent it causes, prevents, and reduces violent extremism.Footnote113 One of the reasons why we lack such insight is the complexity of identity as a construct: the field of identity research is vast and offers many different ideas of what identity is and how it functions, including its influence on people’s attitudes and behaviors. Therefore, in this study, we inventoried the various identity concepts that have been studied as presumed predictors of violent extremism in quantitative research, and reviewed the extent to which these identity concepts are empirically linked to violent extremism.

Identity Concepts in Quantitative Research on Violent Extremism

We found that, in line with the vastness of identity research in general,Footnote114 quantitative studies on the putative effect of identity on violent extremism use a variety of identity concepts that stem from a scope of different theories. However, the amount of attention each of the perspectives received is skewed, with the overwhelming majority examining identity concepts that are routed in social and contextual theories. Thus, within quantitative research on extremism, identity is most often approached in the form of meaningful group-memberships and how they operate in specific social contexts. This makes sense, as social identity processes are crucial for understanding the internalization of group-based norms, values, and beliefsFootnote115 and inter-group violence,Footnote116 therefore playing an integral part in various theoretical radicalization models.Footnote117 In line with the idea that salient social identities are the core ingredient of all inter-group conflicts, the two most studied identity concepts were ingroup identification and identity fusion, which, in combination with contextual factors such as perceived ingroup threat, have been examined as presumed risk factors of extremist attitudes and intentions. In comparison, considerably less attention has been given to social identity concepts that are suggested to help prevent or reduce violent extremism: common-ingroup identification, dual (versus incompatible dual or separated) identification, and integrated (versus separated, assimilated, and marginalized) cultural identities, which we found were commonly studied as tools to help counter-act the monopoly of single social identities, and therefore suggested to reduce the support for or willingness to use political violence.

Surprisingly, only two studies examined the link between personal and developmental identity concepts or processes and extremist radicalization, with one investigating the restorative effect of alternative identities on the recidivism of terrorist offenders,Footnote118 and the second testing the putative risk effect of identity diffusion on left-wing, right-wing, and Islamist extremist attitudes.Footnote119 The lack of quantitative research on this perspective is remarkable, as the presumed link between personal and developmental identity processes and extremist radicalization is a familiar one among both scholars and policy makers: apart from the suggestion that a personal (identity) crisis may function as a cognitive opening for radicalization,Footnote120 for more than a decade, young people’s vulnerability to extremist radicalization has been ascribed to the challenge of forming an identity during adolescence.Footnote121 Yet, despite its popularity, we found that the link between identity (processes) and violent extremism has barely been empirically tested from a personal and developmental approach.

Finally, approximately a quarter of the reviewed studies examined the relation between identity needs and violent extremism, including the need for certainty (i.e. uncertainty), the need for significance and status, the need to belong, and the need for self-esteem.

The (Putative) Effect of Identity on Violent Extremism

The second aim of this paper was to review the evidence for the link between the different identity concepts and violent extremism. The relation that stands out as the most statistically robust is that between identity fusion and violent extremism, such that, across ideologies, individuals whose social identity is fused with their personal identity tend to report stronger support for extremist violence or the willingness to engage in violence themselves. Furthermore, comparative studies showed that a fused identity increases the risk of extremism, over and above strong ingroup identification.Footnote122 Finally, the presumed causal direction of the effect of a salient fused identity on violent extremism is confirmed in five experimental studies, offering evidence that identity fusion can be considered a key risk factor for cognitive extremism. As none of the reviewed studies has examined the link between identity fusion and behavioral extremism, however, future studies should investigate whether the effect also translates to extremist actions.

Ingroup identification in itself seems to be a relevant identity concept for violent extremism as well. In line with a number of theoretical radicalization models,Footnote123 a substantial number of reviewed studies found that, across different populations and ideologies, identifying with one’s ingroup increases the likelihood of supporting or intending to use violence in favor of that group, especially when the ingroup is perceived as threatened by outgroups. Similarly, in line with the social identity model of collective action,Footnote124 it was found that on the basis of a relevant social identity, group-based anger and efficacy are linked to extremist intentions. There is also some evidence to suggest that a civic or activist identity increases the likelihood of violent extremist attitudes and intentions, but only when combined with post-conventional moral reasoning, obsessive identification with one’s cause, experienced hatred, and perceived identity threat.

In contrast to evidence on the role of ingroup identification and identity fusion, we have only little insight into the link between how people manage their multiple social or cultural identities and how that effects violent extremism, with most findings being mixed. While common-ingroup identification and integrated (i.e. dual) social or cultural identities were considered promising ingredients in the prevention of extremist radicalization,Footnote125 some of the reviewed studies demonstrated that under certain circumstances their presumed protective effect can potentially turn and actually form a risk: for instance, members of ethnocultural majorities may not consider a proposed common-ingroup identity (e.g. nationality) inclusive and gatekeep it form minority groups.Footnote126 Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that individuals who have an integrated or dual identity, but perceive its two components (i.e. cultures) to be incompatible may be more inclined to extremist beliefs and intentions.Footnote127 These findings imply that successfully managing multiple social identities involves more than making sure that members of a multicultural society form an integrated social or cultural identity. Instead, underlying societal issues that render social identities incompatible, such as experiences of lower social status, relative deprivation or ingroup discrimination, but also perceived symbolic or realistic threat, may have to be tackled as well.

Similarly, findings with regard to the effect of the four identity needs on violent extremism were mixed. While there is some evidence that the need for certainty (i.e. uncertainty), significance and status, belonging, and self-esteem are linked to a preference for violent extremist organizations and support for extremist violence, about half of the effects are not statistically significant. One of the reasons for the lack of support, may be the fact that most of the respective studies examined the putative effect of identity needs on extremist attitudes and intentions and not on the identification with extremist groups, as was originally proposed by the Uncertainty-Identity TheoryFootnote128 and the Significance Quest Model of Radicalization,Footnote129 as well as general theories on need-motivated identity construction.Footnote130 Moreover, most of the reviewed studies assessed identity needs and indicators of extremism at the same point in time, making it impossible to establish the presumed precedence or even causal effect. Therefore, it is not yet established that frustrated identity needs are present before individuals are radicalized and not when they have already identified with an extremist group and adopted their ideas. Thus, future longitudinal or experimental research is necessary to determine whether frustrated identity needs are the driving force that cause individuals to identify with extremist groups and adopt extremist ideologies to account for their need frustration. Moreover, future studies should include more than one identity need instead of examining only one. While we found that it is thus far mostly tested whether extremist radicalization is caused by the one supposedly fundamental psychological need (i.e. uncertainty and the need for significance etc.), theories within the identity-need-motive-approach propose that the list of needs that motivate identity construction is in fact inconclusiveFootnote131 and that which identity need is the motivating force may depend on people’s personality,Footnote132 but also on the kind of groups that are accessible to them.Footnote133 Finally, since, surprisingly, a number of identity needs (e.g. the need to belong) were linked to a decrease in violent extremism, it is be worthwhile to explore how they could be used to protect people from radicalizing. For example, it has been argued that positively reinterpreting uncertainty as a challenge that people can master through cooperation instead of hostility may prevent people from radicalizing.Footnote134 Moreover, teaching people how to maintain a healthy, positive identity that fulfills their identity needs may increase their resilience to extremism.Footnote135

Since they have thus far received too little attention in quantitative empirical research, we cannot draw firm conclusions regarding the effect of personal and developmental identity concepts and processes on violent extremism. In line with the suggestion that extremist radicalization can be caused by a personal (identity) crisis,Footnote136 one study found that a diffused identity was linked to a higher likelihood of having right-wing, left-wing, or Islamist extremist attitudes.Footnote137 Moreover, in line with the implication that deradicalization is linked to finding new priorities in life, accompanied by shifts in identity,Footnote138 one study found that forming multi-facetted identities based on significant life changes was negatively related to violent extremist behaviors as they present an alternative to identities that are exclusively based on extremist conventions and group membership.Footnote139 However, both findings require replication and more scrutiny in future research.

General Shortcomings and Outlines for Future Research Directions

Apart from providing an inventory of identity concepts as predictors of extremist radicalization, this review demonstrates that, although radicalization is commonly referred to as a process, most quantitative studies on the putative effect of identity employed a cross-sectional research design and only collected data at one point in time. As a result, most studies in this review cannot draw any conclusions regarding the role the various identity concepts play at the different stages of radicalization, including whether they are a cause or part of it. For instance, personal and developmental identity concepts and processes, such as identity diffusion, as well as frustrated needs and motives were suggested to contribute most to an increased vulnerability to enter the first stages of radicalization, such that they create a cognitive opening to extremist ideologies and groups.Footnote140 Personal and developmental processes may also provide possible mechanisms for deradicalization.Footnote141 Social and contextual identity concepts and processes, on the other hand, may play a more important part in the transition from non-violent to violent intergroup behavior among those who already have an established identity but perceive it to be threatened or undervalued. In order to defend their social identity (and the psychological needs it fulfills) people may resort to violence, and when their social identity is fused with the personal identity, the violence may even escalate into terrorist activity.

Alternatively, personal and developmental identity issues and social and contextual identity conflicts may also account for two qualitatively different radicalization processes.Footnote142 While personal identity and identity formation may matter more at an individual level (e.g. online and lone-wolf extremism), social and cultural identity may be more important for understanding societal tensions. In line with this, Schwartz, Dunkel & WatermanFootnote143 argue that social identity factors refer particularly to ethnically or religiously motivated radicalization that are based on normative and collective commitments (i.e. right-wing extremism or extremist Islamism), while identity processes of other extremist groups, such as abortion opponent groups, animal rights activists, eco-terrorists, Baader-Meinhof Gang or Students for a Democratic Society, may be considerably different. Indeed, one of the reviewed studies has shown that individuals with politically progressive views and post-conventional moral reasoning (versus individuals with conservative views and conventional moral reasoning) may be more prone to radicalize when they lack a sense of meaningfulness.Footnote144 More experimental and longitudinal studies are necessary to test these assumptions.

Finally, in order to understand and intervene in radicalization processes, it is not only crucial to assess the “main effects” of each conceptualization of identity, but to acknowledge how interactions between the different identity concepts affect the process of radicalization.Footnote145 We also need to acknowledge that rather than being the prime cause of radicalization into violent extremism, identity issues are most likely a factor that either increases or decreases the risk of radicalization when combined with other risk factors.

Limitations of This Systematic Review

This systematic review has two important limitations. First, despite the comprehensive search, it is possible that we missed relevant studies. We only used the overarching term “identity” as primary search term to find empirical studies that examined different conceptualizations of identity as determinant of violent extremism. However, this may have resulted in missing studies that included concepts that are part of one of the three theoretical perspectives but did not specifically use the term “identity.” Identity needs, including the need to belong, the need for certainty, or the need to belong, for instance, may have been studied in relation with violent extremism, without having been defined as identity concepts. Second, this systematic review relied on narrative synthesis, rather than meta-analysis. This way we could not establish which identity concept has the strongest link with violent extremist attitudes, intentions, or behaviors. However, given the heterogeneity of study designs, sample populations, ideologies, outcome variables, and – most importantly – the various ways in which identity has been studied in relation to extremist radicalization, at this point, a meta-analysis would not have made much sense. As we demonstrated in this review, some identity concepts were studied quite extensively, while others, thus far, have received very little attention in quantitative research on extremist radicalization, leaving not enough statistical power to compare their effects. When the field develops further, future reviews may include meta-analytical techniques to establish more precisely how strong various identity concepts are related to extremist attitudes, intentions and behaviors, for which types of extremism and for who.

Conclusion

This systematic review of 75 studies illustrates that the relation between identity and extremist radicalization is a fruitful area of research in which several insights have been gained, but that is in need for future research. Most importantly, our review demonstrated that the attention each of the three broad theoretical perspectives on identity receives in quantitative extremism research is skewed, with the large majority of studies conducted on social and contextual identity concepts, about a quarter on the needs and motives underlying identity formation, and only two studies on personal and developmental identity concepts. As identity concepts operate differently, this review also emphasizes that it is important to distinguish more carefully between them to be able to understand its effect on violent extremism. Finally, regardless of the many hypotheses on the presumed effect of identity on violent extremism, only few studies employed a design that allows for conclusions regarding the causal direction of this effect. All in all, this field of research is promising, but we need to conduct more integrated and sophisticated research, including studies with longitudinal or experimental designs.

Acknowledgments

With special thanks to Mischa Hoffer for her help as second screener.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Seth J. Schwartz, Curtis S. Dunkel, and Alan S. Waterman, “Terrorism: An Identity Theory Perspective,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 32, no. 6 (2009); Christopher Dean, “The Role of Identity in Committing Acts of Violent Extremism-and in Desisting from Them," (HeinOnline, 2017); Harrie Jonkman, et al., Onderwijs, identiteitsontwikkeling bij jongeren en hun omgang met idealen: Een studie naar het ontstaan van radicalisering in de vroege adolescentie en de rol van het onderwijs hierin (2022); Michael King and Donald M Taylor, “The Radicalization of Homegrown Jihadists: A Review of Theoretical Models and Social Psychological Evidence,” Terrorism and political violence 23, no. 4 (2011).

2 Boris Bizumic, et al., “The Role of the Group in Individual Functioning: School Identification and the Psychological Well-Being of Staff and Students,” Applied Psychology-an International Review-Psychologie Appliquee-Revue Internationale 58, no. 1 (2009); Susan E. Cross, Jonathan S. Gore, and Michael L. Morris, “The Relational-Interdependent Self-Construal, Self-Concept Consistency, and Well-Being,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85, no. 5 (2003); William B. Swann Jr., et al., “Identity Fusion: The Interplay of Personal and Social Identities in Extreme Group Behavior,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 96, no. 5 (2009).

3 Elisabetta Crocetti, Rasa Erentaitė, and Rita Žukauskienė, “Identity Styles, Positive Youth Development, and Civic Engagement In Adolescence,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 43, no. 11 (2014); Elisabetta Crocetti, Parissa Jahromi, and Wim Meeus, “Identity and Civic Engagement in Adolescence," Journal of Adolescence 35, no. 3 (2012).

4 Erik H. Erikson, “Childhood and Society 2nd ed.,” Erikson-New York: Norton (1963); Erik H. Erikson, “Identity and the Life Cycle: Selected Papers,” (1968); Erik Erikson, “Youth: Identity and Crisis,” New York, Ny: Ww 10 (1968); Seth J. Schwartz, et al., “Identity Development, Personality, and Well-Being in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood: Theory, Research, and Recent Advances,” (2013); Justin T. Sokol, “Identity Development Throughout the Lifetime: An Examination of Eriksonian Theory,” Graduate Journal of Counseling Psychology 1, no. 2 (2009).

5 Vivian L. Vignoles, et al., “Beyond Self-Esteem: Influence of Multiple Motives on Identity Construction,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90, no. 2 (2006).

6 Jeannette CG Lely, et al., “The Effectiveness of Narrative Exposure Therapy: A Review, Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression Analysis,” European Journal of Psychotraumatology 10, no. 1 (2019).

7 Dan P. McAdams, “Narrative Identity,” in Handbook of Identity Theory and Research (Springer, 2011); Lauren L. Mitchell, et al., “A Conceptual Review of Identity Integration Across Adulthood,” Developmental Psychology 57, no. 11 (2021); Schwartz et al., “Identity Development, Personality, and Well-Being in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood: Theory, Research, and Recent Advances.”; Seth J. Schwartz, et al., “Identity in Emerging Adulthood: Reviewing the Field and Looking Forward,” Emerging Adulthood 1, no. 2 (2013); W. David Wakefield and Cynthia Hudley, “Ethnic and Racial Identity and Adolescent Well-Being,” Theory into Practice 46, no. 2 (2007).

8 Mitchell et al., "A Conceptual Review of Identity Integration across Adulthood.”; Schwartz et al., “Identity Development, Personality, and Well-Being in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood: Theory, Research, and Recent Advances.”; Schwartz et al., “Identity in Emerging Adulthood: Reviewing the Field and Looking Forward.”; Wakefield and Hudley, “Ethnic and Racial Identity and Adolescent Well-Being.”

9 King and Taylor, “The Radicalization of Homegrown Jihadists: A Review of Theoretical Models and Social Psychological Evidence.”

10 Alex P. Schmid, “Radicalisation, De-Radicalisation, Counter-Radicalisation: A Conceptual Discussion and Literature Review,” ICCT Research Paper 97, no. 1 (2013).

11 McCauley and Moskalenko, “Understanding Political Radicalization: The Two-Pyramids Model.”

12 Fathali M. Moghaddam, “The Staircase to Terrorism: A Psychological Exploration,” American Psychologist 60, no. 2 (2005); J. van Stekelenburg and P. G. Klandermans, “Radicalization,” Identity and Participation in Culturally Diverse Societies. A Multidisciplinary Perspective (2010).

13 Dirk Baier, “Report for the 23rd German Congress on Crime Prevention” (Paper presented at the Internet documentation of the German Congress on Crime Prevention. Hannover. Retrieved March, 2018); Mitchell D. Silber, Arvin Bhatt, and Senior Intelligence Analysts, Radicalization in the West: The Homegrown Threat (Police Department New York, 2007); Quintan Wiktorowicz, Islamic Activism: A Social Movement Theory Approach (Indiana University Press, 2004); Quintan Wiktorowicz, Radical Islam Rising: Muslim Extremism in the West (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005).

14 Silber, Bhatt, and Analysts, Radicalization in the West: The Homegrown threat; Wiktorowicz, Islamic Activism: A Social Movement Theory Approach; Wiktorowicz, Radical Islam Rising: Muslim Extremism in the West.

15 Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko, “Toward a Profile of Lone Wolf Terrorists: What Moves an Individual from Radical Opinion to Radical Action,” Terrorism and Political Violence 26, no. 1 (2014); Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko, “Understanding Political Radicalization: The Two-Pyramids Model,” American Psychologist 72, no. 3 (2017); Schwartz, Dunkel, and Waterman, “Terrorism: An Identity Theory Perspective.”

16 Mary Beth Altier, Christian N. Thoroughgood, and John G. Horgan, “Turning Away From Terrorism: Lessons from Psychology, Sociology, and Criminology,” Journal of Peace Research 51, no. 5 (2014); Schwartz, Dunkel, and Waterman, “Terrorism: An Identity Theory Perspective.”

17 Michael P. Arena and Bruce A. Arrigo, “Social Psychology, Terrorism, and Identity: A Preliminary Re-Examination of Theory, Culture, Self, and Society,” Behavioral Sciences & the Law 23, no. 4 (2005); Dean, “The Role of Identity in Committing Acts of Violent Extremism-and in Desisting from Them.”; Schwartz, Dunkel, and Waterman, “Terrorism: An Identity Theory Perspective.”

18 Vivian L. Vignoles, Seth J. Schwartz, and Koen Luyckx, “Introduction: Toward an Integrative View of Identity,” in Handbook of Identity Theory and Research (Springer, 2011).

19 Vignoles, Schwartz, and Luyckx, “Introduction: Toward an Integrative View of Identity.”

20 i.e., social identity, see Henri Tajfel and John C Turner, “The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior,” in Political Psychology (Psychology Press, 2004).

21 i.e., cultural identity; see Lene Arnett Jensen, Jeffrey Jensen Arnett, and Jessica McKenzie, Globalization and Cultural Identity (Springer, 2011).

22 David Moshman, “Us and Them: Identity and Genocide,” Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 7, no. 2 (2007); David Moshman, “Identity, Genocide, and Group Violence,” in Handbook of Identity Theory änd Research (Springer, 2011); Steven K. Baum, The Psychology of Genocide: Perpetrators, Bystanders, and Rescuers (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

23 i.e., personal identity; e.g., Erikson, “Youth: Identity and Crisis.”; Erik Homburger Erikson, “The Problem of Ego Identity,” Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 4, no. 1 (1956); Erikson, “Childhood and Society 2nd ed.”; Erikson, “Identity and the Life Cycle: Selected Papers.”; Sam A. Hardy and Gustavo Carlo, “Identity as a Source of Moral Motivation,” Human Development 48, no. 4 (2005); Douglas A. MacDonald, “Spirituality: Description, Measurement, and Relation to the Five Factor Model of Personality,” Journal of Personality 68, no. 1 (2000); Hazel Markus and Paula Nurius, “Possible Selves,” American Psychologist 41, no. 9 (1986); Dan P. McAdams and Kate C. McLean, “Narrative Identity,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 22 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413475622; Alan S. Waterman, “Identity, the Identity Statuses, and Identity Status Development: A Contemporary Statement,” Developmental Review 19, no. 4 (1999).

24 see Marilynn B. Brewer and Miles Ed Hewstone, Self and Social Identity (Blackwell Publishing, 2004); Julian Hasford, et al., “Community Involvement and Narrative Identity in Emerging and Young Adulthood: A Longitudinal Analysis,” Identity 17, no. 1 (2017); Mitchell, et al., “A Conceptual Review of Identity Integration across Adulthood.”; Schwartz et al., “Identity Development, Personality, and Well-Being in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood: Theory, Research, and Recent Advances.”; Schwartz et al., “Identity in Emerging Adulthood: Reviewing the Field and Looking Forward.”; Wakefield and Hudley, “Ethnic and Racial Identity and Adolescent Well-Being.”

25 Brewer and Hewstone, Self and Social Identity; Crocetti, Jahromi, and Meeus, “Identity and Civic Engagement in Adolescence.”; Hasford et al., “Community Involvement and Narrative Identity in Emerging and Young Adulthood: A Longitudinal Analysis.”

26 Glynis Breakwell, “17 Identity Process Theory,” The Cambridge Handbook of Social Representations (2015); Michael A. Hogg, “Uncertainty–Identity Theory,” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 39 (2007); Constantine Sedikides and Michael J. Strube, “Self-Evaluation: To Thine Own Self Be Good, To Thine Own Self Be Sure, To Thine Own Self Be True, and To Thine Own Self Be Better,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Elsevier, 1997); Vivian L. Vignoles, et al., “Identity Motives Underlying Desired And Feared Possible Future Selves,” Journal of Personality 76, no. 5 (2008); Vignoles, et al., “Beyond Self-Esteem: Influence of Multiple Motives On Identity Construction.”

27 Vignoles, Schwartz, and Luyckx, “Introduction: Toward an Integrative View of Identity.”

28 Dean, “The Role of Identity in Committing Acts of Violent Extremism-and in Desisting from Them.”

29 Dean, “The Role of Identity in Committing Acts of Violent Extremism-and in Desisting from Them.”; Swann Jr, et al., “Identity Fusion: The Interplay of Personal and Social Identities in Extreme Group Behavior.”; William B. Swann Jr, et al., “When Group Membership Gets Personal: A Theory of Identity Fusion,” Psychological Review 119, no. 3 (2012).

30 Hogg, “Uncertainty–Identity Theory.”; Michael A. Hogg and Janice Adelman, “Uncertainty–Identity Theory: Extreme Groups, Radical Behavior, and Authoritarian Leadership,” Journal of Social Issues 69, no. 3 (2013).

31 Schwartz, Dunkel, and Waterman, “Terrorism: An Identity Theory Perspective.”; Wim Meeus, “Why Do Young People Become Jihadists? A Theoretical Account On Radical Identity Development,” European Journal of Developmental Psychology 12, no. 3 (2015).

32 e.g., Meeus, “Why Do Young People Become Jihadists? A Theoretical Account on Radical Identity Development.”

33 Erikson, “Youth: Identity and Crisis.”; Erikson, “The Problem of Ego Identity.”; Erikson, “Childhood and Society 2nd ed.”; Erikson, “Identity and the Life Cycle: Selected Papers.”; James E. Marcia, “The Ego Identity Status Approach to Ego Identity,” in Ego identity (Springer, 1993).

34 e.g., marginalization; Chris Angus, “Radicalisation and Violent Extremism: Causes and Responses,” (2016); Jamie Bartlett and Carl Miller, “The Edge of Violence: Towards Telling the Difference between Violent and Non-violent Radicalization,” Terrorism and Political Violence 24, no. 1 (2012); Alejandro J. Beutel, “Radicalization and Homegrown Terrorism in Western Muslim Communities: Lessons Learned for America,” Minaret of Freedom Institute 30 (2007); Kris Christmann, “Preventing Religious Radicalisation and Violent Extremism: A Systematic Review of the Research Evidence,” (2012); Tomas Precht, “Home Grown Terrorism and Islamist Radicalisation in Europe,” Retrieved on 11 (2007).

35 e.g., Myriam Vandenbroucke, et al., “Gemeentelijk beleid voor Marokkaans-Nederlandse jongeren,” Rapportage over de wenselijkheid van specifiek doelgroepenbeleid (2008).

36 Arena and Arrigo, “Social Psychology, Terrorism, and Identity: A Preliminary Re-examination of Theory, Culture, Self, and Society.”; Dean, “The Role of Identity in Committing Acts of Violent Extremism-and in Desisting from Them.”; Schwartz, Dunkel, and Waterman, “Terrorism: An Identity Theory Perspective.”

37 Dean, “The Role of Identity in Committing Acts of Violent Extremism-and in Desisting from Them.”

38 Arena and Arrigo, “Social Psychology, Terrorism, and Identity: A Preliminary Re-Examination of Theory, Culture, Self, and Society.”; Dean, “The Role of Identity in Committing Acts of Violent Extremism-and in Desisting From Them.”; Michael Wolfowicz, et al., “A Field-Wide Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Putative Risk and Protective Factors for Radicalization Outcomes,” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 36, no. 3 (2020).

39 Seth J Schwartz, Koen Luyckx, and Vivian L. Vignoles, Handbook of Identity Theory and Research (Springer, 2011).

40 David Moher”, et al., “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement,” Annals of Internal Medicine 151, no. 4 (2009).

41 e.g., Hogg and Adelman, “Uncertainty–Identity Theory: Extreme Groups, Radical Behavior, and Authoritarian Leadership.”

42 McCauley and Moskalenko, “Toward a Profile of Lone Wolf Terrorists: What Moves an Individual from Radical Opinion to Radical Action.”; McCauley and Moskalenko, “Understanding Political Radicalization: The Two-Pyramids Model.”

43 e.g., Henri Ed Tajfel, Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (Academic Press, 1978); Martijn Van Zomeren, Tom Postmes, and Russell Spears, “Toward an Integrative Social Identity Model of Collective Action: A Quantitative Research Synthesis of Three Socio-Psychological Perspectives,” Psychological Bulletin 134, no. 4 (2008).

44 W. S. Robinson, "Ecological Correlations and the Behavior of Individuals," American Sociological Review 15, no. 3 (1950).

45 Ludovico Alcorta, Jeroen Smits, Haley J. Swedlund, and Eelke de Jong, “The ‘Dark Side’ of Social Capital: A Cross-National Examination of the Relationship between Social Capital and Violence in Africa,” Social Indicators Research 149, no. 2 (2020): 445–65.

46 Jocelyn J. Bélanger, Manuel Moyano, Hayat Muhammad, Lindsy Richardson, Marc-André K. Lafrenière, Patrick McCaffery, Karyne Framand, and Noëmie Nociti, “Radicalization Leading to Violence: A Test of the 3n Model,” Frontiers in Psychiatry 10 (2019): 42.

47 Lars Berger, “Local, National and Global Islam: Religious Guidance and European Muslim Public Opinion on Political Radicalism and Social Conservatism,” West European Politics 39, no. 2 (2016): 205–28.

48 Tomasz Besta, “Overlap between Personal and Group Identity and Its Relation with Radical Pro-Group Attitudes: Data from a Central European Cultural Context,” Studia Psychologica 56, no. 1 (2014): 67–81.

49 Tomasz Besta, Ángel Gómez, and Alexandra Vázquez, “Readiness to Deny Group’s Wrongdoing and Willingness to Fight for Its Members: The Role of Poles’ Identity Fusion with the Country and Religious Group,” Current Issues in Personality Psychology 2, no. 1 (2014): 49–55.

50 Tomasz Besta, Marcin Szulc, and Michał Jaśkiewicz, “Political Extremism, Group Membership and Personality Traits: Who Accepts Violence?/Extremismo Político, Pertenencia Al Grupo Y Rasgos De Personalidad:¿ Quién Acepta La Violencia?,” Revista de Psicología Social 30, no. 3 (2015): 563–85.

51 Elif Çelebi, Maykel Verkuyten, Talha Köse, and Mieke Maliepaard, “Out-Group Trust and Conflict Understandings: The Perspective of Turks and Kurds in Turkey,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 40 (2014): 64–75.

52 Adrian Cherney, and Kristina Murphy, “Support for Terrorism: The Role of Beliefs in Jihad and Institutional Responses to Terrorism,” Terrorism and Political Violence 31, no. 5 (2019): 1049–69.

53 Jeremy W. Coid, Kamaldeep Bhui, Deirdre MacManus, Constantinos Kallis, Paul Bebbington, and Simone Ullrich, “Extremism, Religion and Psychiatric Morbidity in a Population-Based Sample of Young Men,” The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science 209, no. 6 (2016): 491–7.

54 Bertjan Doosje, Annemarie Loseman, and Kees Van Den Bos, “Determinants of Radicalization of Islamic Youth in The Netherlands: Personal Uncertainty, Perceived Injustice, and Perceived Group Threat,” Journal of Social Issues 69, no. 3 (2013): 586–604.

55 Bertjan Doosje, Kees Van den Bos, Annemarie Loseman, Allard R. Feddes, and Liesbeth Mann, “My in-Group Is Superior!”: Susceptibility for Radical Right-Wing Attitudes and Behaviors in Dutch Youth,” Negotiation and Conflict Management Research 5, no. 3 (2012): 253–68.

56 Oluf Gøtzsche-Astrup, “Personality Moderates the Relationship between Uncertainty and Political Violence: Evidence from Two Large Us Samples,” Personality and Individual Differences 139 (2019): 102–9.

57 Jonas R. Kunst, John F. Dovidio, and Lotte Thomsen, “Fusion with Political Leaders Predicts Willingness to Persecute Immigrants and Political Opponents,” Nature Human Behaviour 3, no. 11 (2019): 1180–1189.

58 Shana Levin, Peter J. Henry, Felicia Pratto, and Jim Sidanius, “Social Dominance and Social Identity in Lebanon: Implications for Support of Violence against the West,” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 6, no. 4 (2003): 353–68.