Abstract

Building on calls for more analyses of constructions of gender within extremist groups, this study examines Australian neo-Nazis’ construction of hegemonic masculinity on the digital media platform, Telegram. Undertaking a keyword co-occurrence analysis of 3,279 posts and a qualitative analysis of 624 posts from 6 Australian neo-Nazi Telegram Channels, we empirically validate how Australian neo-Nazis use this media platform to idealise a strong, white and combat-ready masculinity. This masculinity is centred on protecting ‘vulnerable’ white women and girls from non-white men and simultaneously casts alternative masculinities, in particular those associated with the LGBTQIA + community, as weak and deviant.

In the Australian context, and paralleling other Western nation-states,Footnote1 there has been a recent resurgence in public visibility of neo-Nazi groups. For example, in January 2021, it was reported that between 30 and 40 men were seen performing Nazi salutes and chanting Nazi and white power slogans while they camped and hiked in the (locally) well-known Grampians National Park.Footnote2 This increase in public visibility of neo-Nazi groups in the Australian context is of note, given scholarsFootnote3 have documented that anti-democratic, old right-wing extremist groups, such as neo-Nazis, have decreased in popularity in Australia in recent years, while other nationalistic, patriot and often Islamophobic groups have gained support, particularly in the mid-2010s.Footnote4 However, given the recent increase in public visibility and coordination of neo-Nazi groups, it appears that “old” right-wing extremist groups are resurgent in Australia, particularly neo-Nazis. This resurgence also appears bound up with the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been referred to as a “breeding ground” for the far-rightFootnote5 given it has provided a unique opportunity to exploit disenfranchisement and distrust in liberal democratic systems of governance. This advantage manifests in (apparently successful) efforts to draw in men who feel dissatisfied with their relationships, career, or financial prosperity.Footnote6

While there is a growing scholarship exploring patriarchal gendered social and political visions among the far-right, researchers have called for a stronger and more sustained focus on the ways such groups are centrally “anti-feminist and even misogynistic”.Footnote7 ScholarsFootnote8 have warned that there is a gender blind spot in countering and preventing violent extremism, especially relating to misogyny and masculinism. Existing research typically focuses on the experiences of men in far-right groups by using qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups,Footnote9 looks at small samples of snippets of discourse from far-right websites, manifestos and online interviews,Footnote10 or relies on no empirical data, but rather describes past or present manifestations of the far-right.Footnote11

While these existing research approaches are valuable, large-scale, mixed-methods studies that blend computational and qualitative analyses are required to establish empirically the role that gender plays in contemporary neo-Nazi groups, and validate the findings of existing, smaller-scale, more qualitative research. Such studies are increasing in number, but still are not common. A recent studyFootnote12 combined word frequency analysis with qualitative thematic analysis to explore gender ideology in far-right online spaces (Telegram and Stormfront) in Australia and the UK. Relatedly, the role social media platforms (especially alternative social media platforms where users are subjected to little content moderation) have played in proliferating specifically neo-Nazi conceptualisations of gender dynamics is under researched.Footnote13

With this in mind, the present study highlights how Telegram as a platform is allowing neo-Nazis to gather, share harmful ideologies, mobilise, and recruit. To understand and combat the phenomenon of neo-Nazis we must understand how they are using these platforms and to what end. Additionally, while much is known about masculinity and the far-right, the existence, contemporary formation, implications and nuances of gender hierarchies within far-right groups remains a topic of significant research interest in digital contexts. Research on contemporary neo-Nazi masculinity in particular is relatively rare, while work exploring discourses of masculinity in neo-Nazi online communitiesFootnote14 is in its infancy.

Joining this body of research, this paper explores the gender hierarchy that is outlined and considered “natural” by Australian neo-Nazi groups. To do so, we employed a multi-layered research design, where a keyword co-occurrence analysis of 3279 posts from 6 Australian neo-Nazi Telegram channels (Telegram is a digital messaging platform introduced below) was employed to determine the prominence, and overlap, of gender constructs, while a qualitative analysis of 624 posts determined the context surrounding these keywords. Studying how different groups use digital platforms to connect, share ideas, and mobilise – especially violent, ideologically extreme groups that promote hatred and vilification – is vital to better understanding how these groups operate and recruit new members.

Before exploring these findings, literature on the relationship between masculinity and the far-right, with a particular focus on gender hierarchies and male aggrievement, will be outlined, as well as recent research that has specifically addressed the proliferation of far-right online communities. Next, the study’s materials and methods are detailed, and its findings are discussed—organised around themes of men and masculinity, and women and femininity.

Literature Review

Far-Right and Neo-Nazi Masculinity

Scholars situate the “far-right” as an umbrella term that is composed of two subgroups: the radical right and the extreme right. The radical right is characterised as anti-system, but with a belief that their political aims can be achieved within existing frameworks of democracy,Footnote15 often through populist political reform.Footnote16 On the other hand, the extreme right openly rejects democracy,Footnote17 and often focuses on neo-fascist and neo-Nazi ideology.Footnote18 This study is on the latter, and in particular neo-Nazism. Neo-Nazi groups are an example of right-wing extremism which encompasses political ideologies that combine nationalism, xenophobia, racism, anti-democratic sentiment, a call for a strong state and the use of political violence.Footnote19

That racial hierarchies—which position white people as superior to non-white people—are embedded in far-right ideologies is axiomatic, documented extensively in research and resonant in the public imagination. A related significant issue, while less documented, is the way gendered discourses of misogyny and homophobia are used to justify social hierarchies. Most literature on such issues accounts for the far-right more broadly, with a handful of studies focusing specifically on masculinity within neo-Nazi groups. Attention to masculinity is important because research shows that neo-Nazi and other far-right groups are male-dominated.Footnote20 Indeed, the leaders, members and voters of the far-right are predominantly male globally.Footnote21

In the literature on the broader far-right, a patriarchal social hierarchy is justified in part by valorising a conception of hegemonic masculinity,Footnote22 a culturally valorised form of masculinity rooted in white men’s normative domination of both women and other men who are perceived as threats.Footnote23 In this formulation, and well established in social science literature, ConnellFootnote24 theorises multiple masculinities—notably complicit, subordinated and marginalised masculinities—and their organisation in a dominance hierarchy, which stabilises the gender order and ensures the continuance of women’s oppression. Consistent with this, scholars have documented that part of constructing masculinity within far-right groups is the subordination of other masculinities.Footnote25 Racially “othered” men are for example often described to be part of a group of marginalised masculinities that are locked out of the rewards of hegemonic masculinity. However, in the context of the far-right, racially minoritised men arguably reflect another category of subordinated masculinity (associated with gay men), rather than more simply marginalised masculinity, given the connection of the former with being actively oppressed through discursive and physical violence.Footnote26

This conception of a gender hierarchy is common in far-right discourse, and is in line with conservative views on gender that seek to keep men and women in their respective places. Far-right groups, then, have numerously been characterised as sexist and misogynistic.Footnote27 Most far-right groups are ambivalently sexist, in that they combine elements of benevolent and hostile sexism.Footnote28 The far-right expects “their” women to conform to sexist norms, such as reproducing children and being mothers; and racist/nativist norms, such as not dating outside of their race or culture.Footnote29 Misogyny is also present in the portrayal of women and girls as weak or feeble, and needing the protection of men, sometimes from the sexual violence of other, depraved (usually non-white) men, who are framed as “aliens”.Footnote30 This portrayal of white women in need of protection from the sexual violence perpetrated by dangerous non-white men has been found to be a cause for the radical rightFootnote31 and a narrative that mobilises activism.Footnote32 Other researchFootnote33 has had similar findings, suggesting that non-white men are subordinated through portrayals of being simultaneously inferior and animalistic, and thus a threat to women and children.

The smaller body of research focused on neo-Nazism documents similar findings. The particularity of neo-Nazis emerges in the group’s commitment to an understanding of themselves as heirs to Hitler’s National Socialists.Footnote34 Combining ultranationalism, xenophobia, nativism, homophobia and racism,Footnote35 neo-Nazis also have a preoccupation with antisemitism,Footnote36 and advocate for racial segregation as well as actively encourage genocide.Footnote37 This predilection for violence also has implications for gender relations in neo-Nazi ideology. Masculinity is constructed in multiple ways within neo-Nazism, and sometimes through its positioning with other identities. Misogyny is also present, with previous research finding that the only central component of neo-Nazi ideology that is consistently present among members of different neo-Nazi groups is the conceptualisation of men as protectors of weak women,Footnote38 the family and the nation.Footnote39 For example, previous researchFootnote40 has found that neo-Nazi groups outlined a risk posed by black men who wanted to “rape white women”, but were also concerned that the same men might also target white adolescents with acts of homosexual rape.

There is though a duality of misogyny and virulent homophobia that is present within neo-Nazi ideology. Gay masculinities are used to outline an antithesis to a desired masculinity, often because they are viewed as “effeminate”.Footnote41 For example, existing researchFootnote42 has found that members of neo-Nazi groups were internally subjected to homophobic slurs when expressing emotions, which was considered a sign of overt weakness. This reflects that emotions are feminised, seen as unmasculine, and in turn associated with gay men.Footnote43 Notably, as pointed out in existing researchFootnote44 hate and rage are not framed as emotions, but rather as inherent attributes of a desired masculinity. Relatedly, gay men were believed by Nazis to be a demonic Jewish and communist construct that intended to destroy the Aryan family unit,Footnote45 an attitude that underpins the targeting of LGBTQIA + communities with violence that remains prevalent within contemporary neo-Nazi and white supremacist groups.Footnote46

Aggrieved Men

The existence and prominence of these racial and gender hierarchies are central to understanding a significant motif of far-right groups, which is far-right men’s perception of, and backlash to, the idea that they now occupy a subordinate position within the gender hierarchy. This perception underscores feelings of sadness, anger and victimhood.Footnote47 These feelings have been conceptualised in previous scholarship as “aggrieved entitlement”,Footnote48 referring to the victimhood an individual feels when they believe that benefits and privileges they are entitled to have been stolen, lost or unjustly shared with others. Aggrieved entitlement is particularly relevant to masculinity because privilege, social control and domination have historically belonged to men. Sociological factors, such as the widening gap between traditional male breadwinner expectations and changes in the labour market and economy can result in aggrieved entitlement, where young men feel as though something valuable has been taken from them unfairly.Footnote49

It has been argued that support for the far-right is representative of a reactionary rehabilitation for threatened white heterosexual masculinity, and that membership to far-right groups may supply aggrieved men with compensation for the domains of their life where they feel they have missed out, such as within their careers, relationships and finances.Footnote50 Relatedly, young white, heterosexual men and boys are framed as having their natural, dominant position now being occupied by women and girls,Footnote51 with far-right men at times viewing themselves as victims of oppressionFootnote52 and gender discrimination.Footnote53 The presumed culprits identified as causing this shift include a culture of political correctness and social justice, women, feminists, leftists, the LGBTQIA + community, foreigners, people of colour, Jewish people, people with disabilities and “emasculated” men.Footnote54

This issue of aggrievement is particularly prominent for men in neo-Nazi groups for whom a central narrative is that the “natural” race and gender hierarchy has been overturned. Indeed, it has been documented that one of the main goals of some neo-Nazi groups is the restoration of masculinity and the retrieval of male entitlement.Footnote55 As such a feeling of aggrieved entitlement can be a powerful recruitment tool for neo-Nazi groups, where a perceived loss of power has been used to radicalise and recruit disaffected young men, and notably low self-esteem, social marginalisation and difficulty forming a masculine identity are among several key variables associated with men joining neo-Nazi groups.Footnote56 Specifically, neo-Nazi groups appeal to aggrieved young men because they promise a superior subject position for members, which would restore the white patrimonial hierarchy.Footnote57 Joining a neo-Nazi group is framed as a way to reassert the white patriarchy and as an initial step in breaking away from white victimhood, and restoring the assumed natural gender hierarchy.Footnote58 This ties closely with related idealised concepts within neo-Nazism, such as an embrace of aggression and a Nietzschean Will to Power.Footnote59

Additionally, racist doctrine and fascist governance have been framed as ways to re-masculinise the self.Footnote60 As such, members can be motivated by aggrieved entitlement to come together to either reinforce, or reclaim, the hegemonic masculine position in society that they feel entitled to.Footnote61 Relatedly, a key effort of extreme right groups is to bring the perceived victimhood of men into broad public discourse.Footnote62

Aggrieved men can find solidarity by joining neo-Nazi groups and spending time bonding with other men in typically all-male groupsFootnote63 and a crucial element of fascism is the practice of rituals of male bonding. Research finds that members of neo-Nazi groups bond over the idea of coming together as a band of brothers and defending an invaded nation,Footnote64 and that members participate as a form of a rite of passage, with the male bonding that occurs being as or even more important to members than racism or ideology.Footnote65 Male bonding also plays an important role in allowing members to co-construct their masculinityFootnote66 and recruit new members, with existing researchFootnote67 finding that male teenage members of Swedish neo-Nazi groups were recruited by male mentors, such as older cousins, brothers and friends.

Even in the context of feeling, or even being, not recognised as hegemonically masculine, the aspiration of such men to be restored to their “rightful place” atop a gender and racial dominance hierarchy fits well with Connell’s theorising. Indeed, via the concept of “protest masculinity”, Connell’sFootnote68 formulation of hegemonic masculinity allows for thinking about masculine victimhood and aggrievement. In their later refinement of protest masculinity, Connell and MesserschmidtFootnote69 define the concept as a gendered identity “which embodies the claim to power… but which lacks the economic resources and institutional authority” to enact it. Elaborating, WalkerFootnote70 describes protest masculinity as “oriented toward a protest of the relations of production and the ideal type of hegemonic masculinity”, while also emphasising its “destructive, chaotic, and alienating” tendencies.Footnote71 Conventional uses of protest masculinity are almost exclusively reserved for understanding the resistance strategies of underprivileged men. The relational character of the gender order is thus further underscored such that hegemonic masculinity refers to the mechanism of domination, permitting us to understand how other masculinities – in this case those practised within neo-Nazi groups – react to, fit within, and actively try to recreate the socially organised hierarchy.

Networked Far-Right Masculinity

Before outlining this study’s details, literature on the far-right and online spaces will be discussed. This is a necessary precursor to, and justification for, this research’s attention to the gendered discourses of neo-Nazi online groups. A significant portion of recent research exploring the connection between the far-right, masculinity and online spaces has focused on the crossover between the far-right and the “manosphere” (the digital manifestation of the Men’s Liberation Movement).Footnote72 Ideologically, both the far-right and the manosphere espouse misogynistic and sexist beliefsFootnote73 and both communities share figureheads.Footnote74 Men attracted to these communities join based on similar motivations, such as feelings of frustration, dissatisfaction and disorientation.Footnote75

Less research has considered masculinity within online neo-Nazi communities. However, that which exists finds that masculinity and masculine imagery play an important part in online propaganda. Previous research exploring Australian neo-Nazi Telegram channelsFootnote76 found that dual concepts of masculinity and whiteness were used to substantiate exclusivist and supremacist claims to land and territory. Physicality, over intellectual pursuits, is seen as a priority, and outdoor training, boxing, and mixed martial arts have been found to commonly occur in Australian neo-Nazi online propagandaFootnote77 and reflect a priority on domination. Similar findings have been yielded from other studies. One studyFootnote78 found that the most dominant form of masculinity constructed on the white supremacist forum Stormfront was that which promoted racial superiority and a patriarchal protection of white women and families, echoing previous researchFootnote79 that has found misogyny present within the far-right aligns with their valorisation of hierarchy, order and traditional values. However, pointing to the presence of a masculinity contestationFootnote80 an additional form of masculinity was prominent too, one that is domineering, regressive and vitriolic, and which draws heavily from alt-right and manosphere ideologies. Other scholars have outlined the presence of gendered practices within extreme right online spaces. For example, researchFootnote81 has found that the Women’s Forum on Stormfront.org (a women-only extremist online space) served as a virtual community which was able to frame and reinforce gendered practices in extreme right movements; however ideological contestation was present, where women pushed back against the patriarchal gender ideology and traditional gender norms espoused by the movement, including physical and aesthetic standards.

Adding to the extensive literature on the far-right and masculinity, the smaller literature on masculinity and neo-Nazis, and the smaller-still research on networked neo-Nazism and masculinity, this research asks the following questions:

RQ1: How do contemporary Australian neo-Nazi online communities conceptualise an idealised masculinity relative to other, undesirable masculinities?

RQ2: How are women and femininity used by Australian neo-Nazi online communities to co-construct and justify an idealised masculinity?

Methodology

To gain an in-depth understanding of how masculinity and femininity is constructed and performed within contemporary Australian neo-Nazi groups, this study employed a mixed-methods approach.Footnote82 Data was collected from Telegram, which is a cloud-based messaging app known for its focus on speed and security, that allows users to communicate in several different ways, one of which being “channels”, which is the Telegram communication tool explored in this research. Channels can be created by users to broadcast messages (both text and multimedia posts), and can be public or private, with public channels potentially reaching large audiences who can view the channel without a Telegram account, and can find channels through search engines. This research collected data from public Telegram channels only.

Telegram was the platform chosen for this study because during an initial scoping activity, it became apparent there were a host of Australian neo-Nazi individuals and groups present on the platform that were either absent from, or less active on, other mainstream platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, as well as alternative social media platforms such as Gab. Telegram appears to have become an important platform for far-right groups, so much so that the term “Terrorgram” (or “Fascist Telegram”) is used colloquially to refer to roughly 300 far-right and neo-fascist Telegram channels which are shared across other channels with the intent of increasing the far-right’s online visibility.Footnote83 It has also been found that Telegram is an important platform for the Australian far-right,Footnote84 and more specifically Australian neo-Nazi groups, such as The National Socialist Network and the European Australian Movement.Footnote85

To select channels for analysis, a non-probability sampling approach was adopted, similar to that used in existing research exploring Australian far-right Telegram channels,Footnote86 where an initial Australian neo-Nazi Telegram channel was identified as theoretically relevant to the research questions, and then a further 5 channels were selected based on the posting activity of the initial channel—specifically the initial channel was reposting content from the additional channels. Channels were only included if they openly self-identified as neo-Nazis within their discourse. A total of 3,279 posts were collected from the 6 public channels between January 8, 2020 and November 18, 2022. Telegram posts, and associated metadata, were collected from the selected channels via the Telegram API using Python.

There are two key ethical considerations to discuss with regard to the data used in this study: first, the ethics of collecting this data through a waiver of consent, and why it would be both impractical and dangerous to seek informed consent from the users of these channels; and second, a short reflection on why the Telegram channels and figures within them have been kept anonymous. First, are the data “public” and thus “fair game” for researchers to collect and analyse? We acknowledge and follow callsFootnote87 for researchers to reflect critically on the intentionality of social media users when it comes to including “public” social media posts in research. Their study of Twitter users revealed that many users were uncomfortable with the prospect of even their public tweets being included in research without their consent. However, in some cases, they suggest that when proper levels of anonymisation can be undertaken and when the research serves a greater social good, not seeking informed consent can be appropriate. We argue that conducting this research is essential to understanding how neo-Nazi groups use digital media platforms to mobilise and grow. Following the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2023), we argue that the benefits to society outweigh the risks of discomfort associated with including public Telegram channel posts without users’ express permission. Second, why are Telegram Channels and neo-Nazi figures within these channels not identified? Existing researchFootnote88 has noted previously that including identifying information about users – including group names – can increase the chances of backlash, and can alert groups to researcher scrutiny, putting researchers at additional risk of hostility. Based on this, the names of the neo-Nazi groups included in this research have not been listed.

It is worth noting, and warning readers in advance, that the exemplar posts that are included in the findings and discussion sections are represented verbatim, meaning that spelling errors and slurs remain unchanged. The ethical decision to include these racial, misogynistic and homophobic slurs uncensored was difficult, but was ultimately made because removing or censoring them may have inadvertently downplayed the abhorrent nature of the groups being studied.

The data analysis is overall guided by Connell’s hegemonic masculinity framework. Given that hegemonic masculinity is the organising principle of unequal gender relationships, the analysis focuses on espoused configurations of gender practice among neo-Nazi men and how these are constructed relationally through discussion of women and other non-hegemonic masculinities. As above, racially minoritised men are considered in Connell’s work to represent a form of marginalised masculinity, locked out from the privileges of hegemonic masculinity. However, we conceptualise such men as another category of subordinated masculinity, which while typically associated with gay masculinity, is appropriate in the context of far-right ideologies that situate racially minoritised men as necessitating extreme social exclusion.

We recognise that new interpretations of frameworks have been offered in scholarship on the far-right. However, we proceed with an application of Connell’s ideas in ways more consistent with its sociological origins. For example, a recent studyFootnote89 deployed a tripartite model of overlapping categories – hegemonic masculinity, hypermasculinity and toxic masculinity – to present a typology of gendered narratives. This, however, is inconsistent with Connell’s concerns with, for example, the meaning and her rejection of the use of the term toxic masculinity.Footnote90 Crucially, it obfuscates that hegemonic masculinity – as a process, structure and concept – captures the other two proposed types, and furthermore also falls into the trap of categorisation and typological expansion that Connell and other masculinity scholars have sought to avoid.Footnote91 Applying Connell’s formulation in a more “pure” form also allows us to retain a focus on how “Hegemonic masculinity is always constructed in relation to various subordinated masculinities as well as in relation to women”.Footnote92 Our aim is not to map other categories onto our data, but to document the process and particularity of relational subordination, and reveal the character and form of neo-Nazi hegemonic masculinity and the way it situates “others”. Hence, a series of deductive themes, drawn from a relational understanding, were developed and used as key anchors for our Conellian analysis. These are represented in .

Table 1. Deductive gender themes.

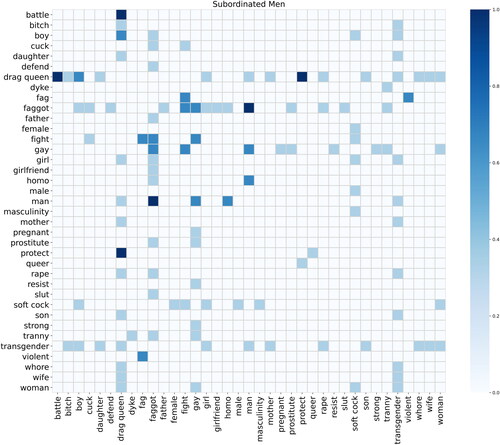

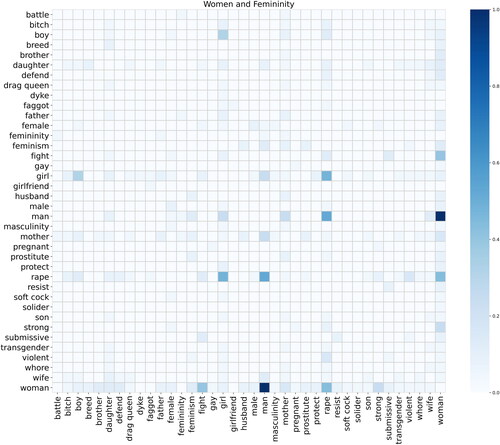

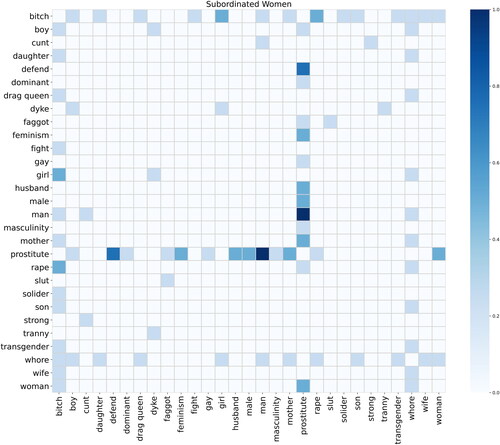

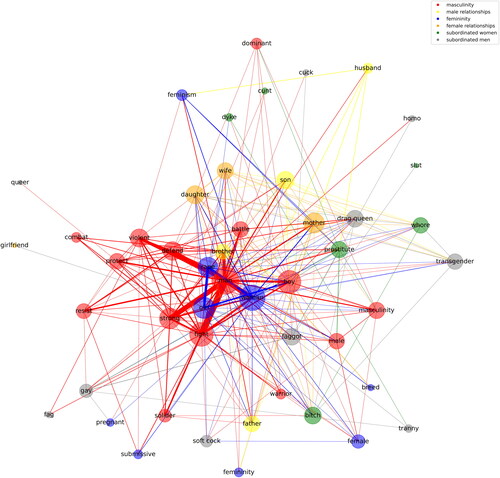

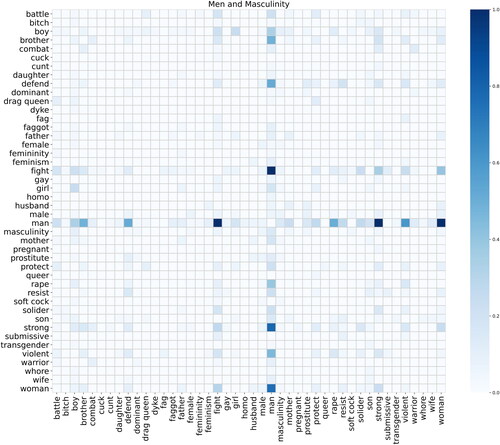

To gain a broad understanding of the gender themes within the entire dataset a keyword co-occurrence network was created.Footnote93 This keyword co-occurrence network provided insights into which gender themes were being discussed most. Keywords associated with each theme were identified during the literature review and expanded using synsets (sets of synonyms) executed using Python’s Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK). For example, the keyword “fight” was drawn from existing scholarship,Footnote94 and synonyms such as “combat” and “battle” were drawn from synsets. Within the keyword co-occurrence network, keywords are represented as nodes, and links between nodes represent co-occurrence between a pair of keywords. Nodes are sized by degree centrality (the total number of links incident on the node), meaning the larger the node, the more frequently the keyword occurs. Links are weighted by the number of times a pair of keywords co-occur, meaning the thicker the link the higher the co-occurrence of a pair of keywords. Both nodes and links are coloured by their associated gender theme. The product of this analysis is a weighted network representing the prevalence of keywords within the dataset, along with their co-occurrence. Additionally, keyword co-occurrence matrices were visualised as heatmaps, which show the normalised weighting of co-occurring keywords and were used to clearly represent which gender themes were being discussed concurrently.

The keyword co-occurrence analysis shed light on which gender themes were most prominent within the overall dataset, and how they overlapped. However, it was limited in that it was unable to provide details about the context surrounding the keywords. As such, all posts that contained a keyword associated with one of the gender themes (n = 624) were inductively coded to establish the specific nature of the discourse, and exemplar posts were selected and included in the findings and discussion section.

Findings and Discussion

The following sections demonstrate the ways that neo-Nazi men construct an idealised masculinity that comprises a vision of hegemonic masculinity, but which, given its lack of cultural level endorsement, also aligns with protest masculinity. This idealised form is in opposition to “subordinated masculinities”, and at the same time women, through increased levels of misogyny directed at those women that deviate from idealised forms of femininity.

The co-occurrence network map () demonstrates, through the scale of nodes by degree centrality, that masculinity, men, and their relationships were the most prominently discussed gender themes within the dataset. Similarly, it represents that femininity, women, and their relationships were the second most prominently discussed. It shows that subordinated men were discussed more frequently than subordinated women. These findings confirm existing research, which has found that discussions of men (both dominant and subordinate) are prominent within neo-Nazi discourse,Footnote95 along with sexist and misogynistic discussions of women.Footnote96

Figure 1. A network map visualising the co-occurrence of keywords associated with the different gender themes. The size of nodes (keywords) is determined by their frequency within the text corpus, and edge width is determined by the frequency of co-occurrence of two keywords.

The co-occurrence network also gives insights into the high levels of connectivity between gender themes, this being represented through the ties being coloured by the gender theme that connects two co-occurring keywords. However, the exact nature of that connectivity is hard to comprehend given the amount of ties between nodes. The heatmaps allow for a more detailed exploration of the connectivity between gender themes.

A Fraternity of Strong Male Warriors

As demonstrated by the co-occurrence network map, men and masculinity was the most dominant theme within the dataset, with 7 of the 20 most commonly occurring keywords belonging to this theme. Men and masculinity were constructed in a specific way, as illustrated in . Neo-Nazi discourse consistently framed men as warriors and protectors who need to be both capable and willing to fight, with “man” and “fight” (weight = 1.00) and “man” and “strong” (weight = 0.78) being the two most commonly co-occurring keywords within the entire dataset. A series of other commonly co-occurring keyword pairs reinforce that an idealised masculinity is one that is both strong and violent, two of the most prominent being “man” and “defend” (weight = 0.50) and “man” and “violent” (weight = 0.44).

Figure 2. Heatmap visualising the co-occurrence of keywords related to men and masculinity. To see the level of co-occurrence between two keywords, first identify the two keywords of interest (one on the x axis, and one of the y axis) and follow the gridlines to see the point at which they intersect. Looking at the square where they intersect, use the colour gradient on the right-hand side of the figure to determine how commonly the keywords co-occurred relative to other keyword combinations – the darker the blue of the square, the more commonly those keywords co-occurred. Follow this procedure for all additional heatmaps presented throughout the findings and discussion section.

The promotion of a strong and violent masculinity as ideal by neo-Nazi groups is unsurprising. Men are viewed as naturally occupying a position of domination within the gender hierarchyFootnote97 due, in part, to their physicality, and as such, white men take on the role of warriors, who must defend the race and nation.Footnote98 Physical strength is essential given the ideal warrior is a virile young man who has a strong body,Footnote99 and as such neo-Nazis celebrate and promote virile and muscular forms of white masculinity.Footnote100 The reality of this ideology is illuminated through the qualitative analysis. Neo-Nazis consider training to be both physically fit, and capable of combat, as essential. The former can be established through training in the gym and participating in hikes, while the latter necessitates learning to fight, in particular by mastering a martial art. One post, after claiming that physical training is characteristic of the Aryan spirit, and antithetical to the Jewish spirit, encourages all Australian neo-Nazis to:

Get in the fucking Gym today, go for a run, hit the bag.

NSW and QLD members held a group training and camp weekend, cultivating and exchanging practical skills and combat training techniques. The importance of building bonds with your brothers in the racial struggle for a free White Australia cannot be understated. The bonds we forge, and the work we put in today, will carry us to victory tomorrow. Tribe & Train.

Part of the process of outlining a desired, white warrior masculinity is placing it in contrast to “undesirable”, and “subordinate” masculinities. Previous research has found that gender and sexuality-diverse people are regularly targeted by the far-rightFootnote103 and our analysis further reveals how fixated posts in these Telegram channels are on queer people. Similarly, neo-Nazis have consistently targeted gay men.Footnote104 As can be seen in , references to subordinated men commonly occurred, with 6 of the 20 most commonly occurring keywords belonging to this theme. In terms of framing an “inferior” form of masculinity, members of the LGBTQIA + community were regularly targeted, with strong co-occurrences for “man” and “faggot” (weight = 1.00), “combat” and “drag queen” (weight = 1.00) and “battle” and “drag queen” (weight = 1.00). Notably, the keyword “fight” co-occurred with multiple keywords associated with LGBTQIA + people, such as “fag” (weight = 0.70), “faggot” (weight = 0.70) and “gay” (weight = 0.70). Australian neo-Nazis were particularly focused on the risks of what they perceived to be paedophilic, Satanic and sometimes Jewish drag queens (notably echoing Nazi beliefs that gay men were demonic Jewish constructsFootnote105) using events that included children as grooming opportunities. There was a heavy emphasis on strong, white and combat-ready neo-Nazi warriors defending children by disrupting these events.

The common homophobic myth that connects gay men to paedophiliaFootnote106 occurred frequently in the dataset. The quote below illustrates the ongoing narrative that members of the LGBTQIA + community are paedophiles, claiming that Headspace (an Australian non-profit organisation focusing on youth mental health) clinics are “grooming” young people. Non-binary and transgender people were also targeted in largely the same way, where they were framed as being unnatural and deviant, as well as paedophiles—the below containing transphobic commentary about a “man” masquerading as an “ugly woman”:

So I walked into a “Headspace” here in Vic on my way to the gym, because I saw a poster at the front saying "We recognise ALL genders" and my lack of filter required me to ask if they had made a mistake and had meant "BOTH". Anyhow, I looked around and these places are basically just grooming centres for today’s youth. The “man” behind the desk was masquerading as an ugly woman and the mental health specialists (the only two in their at the time) was a self-described pansexual. This is disgusting and these “safe spaces” are anything but - they are essentially brainwashing centres ala Frankfurt School style.

The premier of Victoria, Daniel Andrews, is a corrupt, homosexual, pedophile drug addict, who is completely bought out and compromised by Chinese and Jewish Supremacy lobbies.

Several slurs that were not explicitly homophobic, such as “soft cock” and “cuck” were used to subordinate emasculated men, often those that were associated with left-wing political ideologies, such as feminism. Other men and masculinities commonly subordinated were those that were not white and heterosexual. Black and Jewish men were most commonly targeted and were framed as dangerous, evil and scheming. One of the most common references to black men was within the context of a sexual assault or murder, almost invariably of a white woman, which will be further discussed below.

Weak, Defenceless Women

Some existing research exploring the connection between gender hierarchies and violent extremism has been critiqued for focusing on aggrieved masculinities without sufficiently considering misogynyFootnote108. The keyword co-occurrence map demonstrated that women and femininity was the second most prominent theme, accounting for 7 of the 20 most commonly occurring keywords. As can be seen in , “man” and “woman” (weight = 1.00) were the most commonly co-occurring keywords within the women and femininity theme. These co-occurring keywords were often associated with general mentions of “white men and white women” within the text corpus, however, they were also used in conjunction to openly define masculinity and femininity relative to each other:

Our highest order/moral is the preservation and advancement of the White Race. This can not be achieved without it’s two supporting pillars being strengthened; that being the return and cultivation of Masculinity and Feminity as seperate and powerfully unique energies that when ready can merge to strengthen the race (a new little Aryan).

Women play some role in the development of boys and men, but that role is for mother’s, sisters, extended family and eventually one’s wife.

Beyond their interpersonal relationships with men, women and girls were evoked as vulnerable and in need of defence, illustrated through co-occurring keywords such as “fight” and “woman” (weight = 0.40) and “woman” and “defend” (weight = 0.12). The most prominent danger women and girls were presumed to face was sexual assault, with two of the most commonly co-occurring keywords in the women and femininity theme being “man” and “rape” (weight = 0.52), and “woman” and “rape” (weight = 0.44). Portraying white women as weak or feeble and in need of white men’s protection is a common tactic employed by the far-right, with non-white men often imagined targeting white women with different forms of sexual violenceFootnote109. Similar tropes were regularly present within the discourse of Australian neo-Nazis, with vulnerable women often evoked as at risk from the sexual deviance of non-white men:

This is a full blown violent invasion and women are the first victims. Feminism can’t be bothered to stand up for women when it’s their precious colored men doing the raping. Imagine the cognitive dissonance if they were forced to have an honest conversation about assault risk factors. It’s absolutely abhorrent that European women aren’t safe in their own countries.

Ten niggers gang raped two fifteen-year-old girls in Brisbane. This is why we burn crosses!

Abo Whore Lydia Thorpe performs black communist salute whilst subversively swearing allegiance to destroy White Australia. The whole system is a circus run by vile anti-White communists and traitors.

Secondly, non-heterosexual women were framed in a similar way to other members of the LGBTQIA + community—being viewed as sexual deviants who prey on innocent children:

Kaz Ross or Roz Ward, I often get confused between the two of them because they are both fat, retarded, Dykes that spread maoist pedophile propaganda to children and teenagers.

Conclusion

Existing research exploring the role that gender plays in the far-right has focused on the experiences of men in far-right groups by using methods such as surveys, interviews or focus groups,Footnote111 has considered small samples of snippets of discourse from far-right websites, manifestos and online interviews,Footnote112 or have been primarily theoretical.Footnote113 While this previous work has made significant contributions to our understanding of far-right groups, further methodological innovation is needed to understand this rapidly evolving and increasingly digitally mediated movement. Using a large dataset of social media-based data, and a blend of computational and qualitative methods, this study contributes data-driven empirical analysis to further deepen our understanding of how contemporary Australian neo-Nazi groups conceptualise and promote certain visions of men and masculinity, and women and femininity. Connell’s work on hegemonic masculinity was used as an analytical lens, and the findings speak to the ongoing concept’s salience.Footnote114 Given neo-Nazis lack societal-level endorsement or cultural ascendancy, it is contended that this masculinity might better be understood as a protest masculinity, but one seeking to restore a certain vision of hegemonic masculinity characterised by an even more pronounced hierarchy of race and gender dominance and division than is currently the case.

In addition to mapping out the discursive construction of gender in these spaces by these groups, this study has also provided some insight into how neo-Nazi groups are using the digital media platform Telegram to connect, mobilise, and recruit new members. Further research into the digital mediation of these groups and these ideologies is urgently needed, from a number of different methodological and theoretical positions.

This study clearly outlines that contemporary neo-Nazi groups construct masculinities and femininity within a naturalised relational hierarchy, confirming existing research that has documented the domination of women and “inferior” men as part of neo-Nazi masculinity.Footnote115 At the top of the hierarchy are men who embody a specific type of masculinity—one that is white, physically strong and combat-ready. This type of masculinity is fraternal, in that white men within neo-Nazi groups co-construct their masculinity through activities that are almost always group-based, such as exercising and training in hand-to-hand combat. The co-construction of such a masculinity is framed as essential, as neo-Nazi men viewed themselves as warriors responsible for protecting women, children and the nation against adversaries.

Non-hegemonic masculinities are subordinated within the neo-Nazi idealised gender hierarchy. In particular, LGBTQIA + masculinities are positioned as antithetical to an idealised masculinity, in that they are considered weak, feminine, deviant and degenerate. Not only are LGBTQIA + masculinities used to outline what is not part of an idealised masculinity, but they are also framed as an existential threat, both on a local and global scale. On the local scale, members of the LGBTQIA + community, especially drag queens, are accused of both corrupting and preying upon children. While an extreme version, the ordering of these masculinities remains consistent with Connell’s critical conceptualisation of a dominance hierarchy in the normative gender order. An example of the extreme departure from this is that on the global scale, with neo-Nazis propagating conspiratorial narratives of “globohomo”, viewing political and legal entities as part of a broader globalist plot to degenerate, depopulate and destroy Western culture through global monoculture and gender ideology.Footnote116

Against the grain of a sometimes narrow focus on aggrieved masculinity,Footnote117 this study also illuminates the gendered discourses of sexism and misogyny and the ways these are imbricated with justifications for a gender and race hierarchy. The data illustrates the portrayal of white women as vulnerable and requiring immediate defence, which in turn is used to justify the necessary and urgent need to develop a fraternity of strong, combat-ready white men. In particular, the threat of sexual violence against white girls and women is used to simultaneously establish the vulnerability of women and femininity, and subordinate non-white men as predators of both white women and girls, which supports the findings of existing research.Footnote118

Future research into neo-Nazi groups’ constructions of gender should continue to attend to the digital mediation of these movements, ideally across a range of different social media platforms and a host of diverse neo-Nazi groups, to continue to develop clearer, more in-depth and empirically-grounded insights. Additionally, future research would benefit from using existing research to historicise neo-Nazi gender constructs to understand how they shift and develop over time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 99–105.

2 Alexander Darling and Andrew Kelso, “White Supremacists Chanting in the Grampians Draws the Anger of Locals,” ABC News, January 28, 2021.

3 Mario Peucker, Debra Smith, and Muhammad Iqbal, “Not a Monolithic Movement: The Diverse and Shifting Messaging of Australia’s Far-Right,” in The Far-Right in Contemporary Australia, ed. Mario Peucker and Debra Smith (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 93–6.

Geoff Dean, Peter Bell, and Zarina Vakhitova, “Right-Wing Extremism in Australia: The Rise of the New Radical Right,” Journal of Policing, Intelligence and Counter Terrorism 11, no. 2 (2016): 121–42.

4 Mario Peucker and Debra Smith, “Far-Right Movements in Contemporary Australia: An Introduction,” in The Far-Right in Contemporary Australia, ed. Mario Peucker and Debra Smith (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 1–17.

5 Ali MC, “Australia’s Far Right Gets Covid Anti-Lockdown Protest Booster,” Al Jazeera, 2021.

6 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 99–105.

7 Joshua M Roose and Joana Cook, “Supreme Men, Subjected Women: Gender Inequality and Violence in Jihadist, Far Right and Male Supremacist Ideologies,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (2022): 1–29.

8 Christine Agius, Alexandra Edney-Browne, Lucy Nicholas, and Kay Cook, “Anti-Feminism, Gender and the Far-Right Gap in C/PVE Measures,” Critical Studies on Terrorism 15, no. 3 (2022): 681–705.

9 Christer Mattsson, and Thomas Johansson, ““We Are the White Aryan Warriors”: Violence, Homosociality, and the Construction of Masculinity in the National Socialist Movement in Sweden,” Men and Masculinities 24, no. 3 (2021): 393–410.; Elizabeth Ralph-Morrow, “The Right Men: How Masculinity Explains the Radical Right Gender Gap.” Political Studies 70, no. 1 (2022): 26–44.; Michael Kimmel, “Racism as Adolescent Male Rite of Passage: Ex-Nazis in Scandinavia,” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 36, no. 2 (2007): 202–18.

10 Joshua M Roose and Joana Cook, “Supreme Men, Subjected Women: Gender Inequality and Violence in Jihadist, Far Right and Male Supremacist Ideologies,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (2022): 1–29.; Simon Copland, “Weak Men and the Feminisation of Society: Locating the Ideological Glue between the Manosphere and the Far-Right,” in Global Perspectives on Anti-Feminism: Far-Right and Religious Attacks on Equality and Diversity, ed. Judith Goetz and Stefanie Mayer, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh, 2023), 116.

11 Blu Buchanan, “Gay Neo-Nazis in the United States: Victimhood, Masculinity, and the Public/Private Spheres,” GLQ 28, no. 4 (2022): 489–513.; Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 99–105.

12 Alexandra Phelan, Jessica White, Claudia Wallner, and James Paterson. Misogyny, Hostile Beliefs and the Transmission of Extremism: A Comparison of the Far-Right in the Uk and Australia. Lancaster: Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST), 2023.

13 Jillian Sunderland, “Fighting for Masculine Hegemony: Contestation between Alt-Right and White Nationalist Masculinities on Stormfront,” Men and Masculinities 26, no. 1 (2023): 3–23.

14 Ibid; Alexandra Phelan, Jessica White, Claudia Wallner, and James Paterson. Misogyny, Hostile Beliefs and the Transmission of Extremism: A Comparison of the Far-Right in the Uk and Australia. Lancaster: Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST), 2023.

15 Cas Mudde, The Far Right Today (Cambridge: John Wiley & Sons, 2019), 7.

16 Callum Jones, “‘We the People, Not the Sheeple’: Qanon and the Transnational Mobilisation of Millennialist Far-Right Conspiracy Theories,” First Monday 28, no. 3 (2023).

17 Cas Mudde, The Far Right Today (Cambridge: John Wiley & Sons, 2019), 7.

18 Callum Jones, “‘We the People, Not the Sheeple’: Qanon and the Transnational Mobilisation of Millennialist Far-Right Conspiracy Theories,” First Monday 28, no. 3 (2023).; Imogen Richards, Callum Jones and Gearóid Brinn, “Eco-Fascism Online: Conceptualizing Far-Right Actors’ Response to Climate Change on Stormfront,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (2022): 2.

19 Cas Mudde, “Right-Wing Extremism Analyzed: A Comparative Analysis of the Ideologies of Three Alleged Right-Wing Extremist Parties (NPD, NDP, CP’86),” European Journal of Political Research 27, no. 2 (1995): 203–24.

20 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 13.

21 Cas Mudde, The Far Right Today (Cambridge: John Wiley & Sons, 2019), 147–52.; Jessie Daniels, “The Algorithmic Rise of the “Alt-Right”,” Contexts 17, no. 1 (2018): 60–5.

22 Raewyn W Connell, Masculinities (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), 76–81.

23 Joshua M Roose and Joana Cook, “Supreme Men, Subjected Women: Gender Inequality and Violence in Jihadist, Far Right and Male Supremacist Ideologies,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (2022): 1–29.

24 Raewyn W Connell, Masculinities (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), 76–81.

25 Joshua M Roose and Joana Cook, “Supreme Men, Subjected Women: Gender Inequality and Violence in Jihadist, Far Right and Male Supremacist Ideologies,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (2022): 1–29.; Elizabeth Ralph-Morrow, “The Right Men: How Masculinity Explains the Radical Right Gender Gap.” Political Studies 70, no. 1 (2022): 38–44.; Nicole Loroff, “Gender and Sexuality in Nazi Germany,” Constellations 3, no. 1 (2011), 55–9.

26 Christer Mattsson, and Thomas Johansson, ““We Are the White Aryan Warriors”: Violence, Homosociality, and the Construction of Masculinity in the National Socialist Movement in Sweden,” Men and Masculinities 24, no. 3 (2021): 393–410.

27 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 9; Joshua M Roose and Joana Cook, “Supreme Men, Subjected Women: Gender Inequality and Violence in Jihadist, Far Right and Male Supremacist Ideologies,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (2022): 1-29; Michaela Köttig, Renate Bitzan and Andrea Pető, Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe (Cham: Springer, 2017), 87–90.

28 Cas Mudde, The Far Right Today (Cambridge: John Wiley & Sons, 2019), 147–50.

29 Cas Mudde, The Far Right Today (Cambridge: John Wiley & Sons, 2019), 147–62.

30 Elizabeth Ralph-Morrow, “The Right Men: How Masculinity Explains the Radical Right Gender Gap.” Political Studies 70, no. 1 (2022): 10.

31 Elizabeth Pearson, Emily Winterbotham, Katherine E Brown, Elizabeth Pearson, Emily Winterbotham, and Katherine E Brown, “The Far Right and Gender,” in Countering Violent Extremism: Making Gender Matter, ed. Elizabeth Pearson, Emily Winterbotham and Katherine E Brown (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 233–79.

32 Elizabeth Pearson, “Gendered Reflections? Extremism in the Uk’s Radical Right and Al-Muhajiroun Networks,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 46, no.4 (2023): 489–512.

33 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 15.

34 James H Anderson, “The Neo-Nazi Menace in Germany,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 18, no. 1 (1995): 39–46.

35 Jeff Gruenewald, Steven Chermak, and Joshua D Freilich, “Far-Right Lone Wolf Homicides in the United States,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 36, no. 12 (2013): 1015–24.

36 Ruth Wodak, “The Radical Right and Antisemitism,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, ed. Jens Rydgren (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 61–85.

37 Amy Cooter, “Neo-Nazi Nationalism,” Studies in ethnicity and nationalism 11, no. 3 (2011): 365–83.

38 Cas Mudde, The Far Right Today (Cambridge: John Wiley & Sons, 2019), 147–62.

39 Michael Kimmel, Angry White Men: American Masculinity at the End of an Era (London: Hachette UK, 2017).

40 Raphael S Ezekiel, “An Ethnographer Looks at Neo-Nazi and Klan Groups: The Racist Mind Revisited,” American Behavioral Scientist 46, no. 1 (2002): 55.

41 Blu Buchanan, “Gay Neo-Nazis in the United States: Victimhood, Masculinity, and the Public/Private Spheres,” GLQ 28, no. 4 (2022): 503.

42 Christer Mattsson, and Thomas Johansson, ““We Are the White Aryan Warriors”: Violence, Homosociality, and the Construction of Masculinity in the National Socialist Movement in Sweden,” Men and Masculinities 24, no. 3 (2021): 404.

43 Raewyn W Connell, Masculinities (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), 76–81.; Christer Mattsson, and Thomas Johansson, ““We Are the White Aryan Warriors”: Violence, Homosociality, and the Construction of Masculinity in the National Socialist Movement in Sweden,” Men and Masculinities 24, no. 3 (2021): 404.

44 Ibid.

45 Nicole Loroff, “Gender and Sexuality in Nazi Germany,” Constellations 3, no. 1 (2011), 59.

46 Christer Mattsson, and Thomas Johansson, ““We Are the White Aryan Warriors”: Violence, Homosociality, and the Construction of Masculinity in the National Socialist Movement in Sweden,” Men and Masculinities 24, no. 3 (2021): 404.

47 Joshua M Roose, Michael Flood, Alan Greig, Mark Alfano and Simon Copland, Masculinity and violent extremism (London: Palgrave, 2022), 65–71.

48 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 15.

49 Ibid.

50 Annie Kelly, “The Alt-Right: Reactionary Rehabilitation for White Masculinity.” Soundings 66, no. 66 (2017): 70–5.; Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 13.; cf. Steven Roberts and Karla Elliott, “Challenging dominant representations of marginalized boys and men in critical studies on men and masculinities”, Boyhood Studies 13, no. 2 (2020): 87–104 caution against reading working-class men as especially reactionary because of precarious economic circumstances.

51 Michaela Köttig, Renate Bitzan and Andrea Pető, Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe (Cham: Springer, 2017), 99.

52 Pam Nilan, Josh Roose, Mario Peucker, and Bryan S Turner, “Young Masculinities and Right-Wing Populism in Australia,” youth 3, no. 1 (2022): 286.

53 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 14.

54 Michaela Köttig, Renate Bitzan and Andrea Pető, Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe (Cham: Springer, 2017), 272–6.; Christer Mattsson, and Thomas Johansson, ““We Are the White Aryan Warriors”: Violence, Homosociality, and the Construction of Masculinity in the National Socialist Movement in Sweden,” Men and Masculinities 24, no. 3 (2021): 404.; Pam Nilan, Josh Roose, Mario Peucker, and Bryan S Turner, “Young Masculinities and Right-Wing Populism in Australia,” youth 3, no. 1 (2022): 286.

55 Michael Kimmel, “Racism as Adolescent Male Rite of Passage: Ex-Nazis in Scandinavia,” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 36, no. 2 (2007): 207.

56 Revital Sela-Shayovitz, “Neo-Nazi Movement in the Twenty-First Century”, in The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism, ed. John Stone, Dennis Rutledge, Polly Rizova, Anthony D Smith and Xiaoshuo Hou (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2016), 2.

57 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 14.

58 Ibid.

59 Imogen Richards, Maria Rae, Matteo Vergani, and Callum Jones, “Political Philosophy and Australian Far-Right Media: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Unshackled and XYZ,” Thesis Eleven 163, no. 1 (2021): 117.

60 Annie Kelly, “The Alt-Right: Reactionary Rehabilitation for White Masculinity.” Soundings 66, no. 66 (2017): 75.

61 Joshua M Roose, Michael Flood, Alan Greig, Mark Alfano and Simon Copland, Masculinity and violent extremism (London: Palgrave, 2022), 65–71.

62 Michaela Köttig, Renate Bitzan and Andrea Pető, Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe (Cham: Springer, 2017), 87.

63 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 99–105.; Michaela Köttig, Renate Bitzan and Andrea Pető, Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe (Cham: Springer, 2017), 83–7.

64 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 16.

65 Michael Kimmel, “Racism as Adolescent Male Rite of Passage: Ex-Nazis in Scandinavia,” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 36, no. 2 (2007): 207–12.

66 Michaela Köttig, Renate Bitzan and Andrea Pető, Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe (Cham: Springer, 2017), 83–7.

67 Michael Kimmel, “Racism as Adolescent Male Rite of Passage: Ex-Nazis in Scandinavia,” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 36, no. 2 (2007): 207.

68 Raewyn W Connell, Masculinities (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995), 76-81.

69 Raewyn W Connell and James W Messerschmidt, “Hegemonic Masculinity:Rethinking the Concept,” Gender & Society 19, no. 6 (2005): 848.

70 Gregory Wayne Walker, “Disciplining Protest Masculinity,” Men and masculinities 9, no. 1 (2006): 5.

71 cf. Steven Roberts, Young working-class men in transition (New York: Routledge, 2018).

72 Alice E Marwick and Robyn Caplan, “Drinking Male Tears: Language, the Manosphere, and Networked Harassment,” Feminist Media Studies (2018): 543.; Marta Barcellona, “Incel Violence as a New Terrorism Threat: A Brief Investigation between Alt-Right and Manosphere Dimensions,” Sortuz: Oñati Journal of Emergent Socio-Legal Studies 11, no. 2 (2022): 175–7.

73 Marta Barcellona, “Incel Violence as a New Terrorism Threat: A Brief Investigation between Alt-Right and Manosphere Dimensions,” Sortuz: Oñati Journal of Emergent Socio-Legal Studies 11, no. 2 (2022): 173.

74 Alice E Marwick and Robyn Caplan, “Drinking Male Tears: Language, the Manosphere, and Networked Harassment,” Feminist Media Studies 18, no. 4 (2018): 544.

75 Marta Barcellona, “Incel Violence as a New Terrorism Threat: A Brief Investigation between Alt-Right and Manosphere Dimensions,” Sortuz: Oñati Journal of Emergent Socio-Legal Studies 11, no. 2 (2022): 172.

76 Imogen Richards, Gearóid Brinn, and Callum Jones, Global Heating and the Australian Far Right (New York: Routledge, 2023), 101.

77 Imogen Richards, Gearóid Brinn and Callum Jones, Global Heating and the Australian Far Right (New York: Routledge, 2023), 102.; Alexandra Phelan, Jessica White, Claudia Wallner, and James Paterson. Misogyny, Hostile Beliefs and the Transmission of Extremism: A Comparison of the Far-Right in the UK and Australia. Lancaster: Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST), 2023, 42.

78 Jillian Sunderland, “Fighting for Masculine Hegemony: Contestation between Alt-Right and White Nationalist Masculinities on Stormfront,” Men and Masculinities 26, no. 1 (2023): 18.

79 Christine Agius, Alexandra Edney-Browne, Lucy Nicholas and Kay Cook, “Anti-Feminism, Gender and the Far-Right Gap in C/Pve Measures,” Critical Studies on terrorism 15, no. 3 (2022): 18.

80 See also Marcus Maloney, Steven Roberts, and Timothy Graham, Gender, Masculinity and Video Gaming: Analysing Reddit’s r/gaming Community (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

81 Yannick Veilleux-Lepage, Alexandra Phelan and Ayse D Lokmanoglu, “Gendered Radicalisation and ‘Everyday Practices’: An Analysis of Extreme Right and Islamic State Women-Only Forums,” European Journal of International Security 8, no. 2 (2023): 238.

82 This approach mirrors that used in existing research that has explored masculinity on the social media site, 4Chan by Marcus Maloney, Steve Roberts, and Callum Jones, “‘How Do I Become Blue Pilled?’: Masculine Ontological Insecurity on 4chan’s Advice Board.” New Media & Society 0, no. 0 (2022): 6.

83 Imogen Richards, Gearóid Brinn and Callum Jones, Global Heating and the Australian Far Right (New York: Routledge, 2023), 96.

84 Alexandra Phelan, Jessica White, Claudia Wallner, and James Paterson. Misogyny, Hostile Beliefs and the Transmission of Extremism: A Comparison of the Far-Right in the UK and Australia. Lancaster: Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST), 2023, 20.

85 Imogen Richards, Gearóid Brinn and Callum Jones, Global Heating and the Australian Far Right (New York: Routledge, 2023), 69.

86 Alexandra Phelan, Jessica White, Claudia Wallner, and James Paterson. Misogyny, Hostile Beliefs and the Transmission of Extremism: A Comparison of the Far-Right in the UK and Australia. Lancaster: Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST), 2023, 20.

87 Casey Fiesler and Nicholas Proferes, ““Participant” Perceptions of Twitter Research Ethics,” Social Media + Society 4, no. 1 (2018).

88 Callum Jones, Verity Trott, and Scott Wright, “Sluts and Soyboys: MGTOW and the Production of Misogynistic Online Harassment,” new media & society 22, no. 10 (2020): 6–7.; Scott Wright, Verity Trott and Callum Jones, “‘The Pussy Ain’t Worth It, Bro’: Assessing the Discourse and Structure of MGTOW,” Information, Communication & Society 23, no. 6 (2020): 912-913.

89 Alexandra Phelan, Jessica White, Claudia Wallner, and James Paterson. Misogyny, Hostile Beliefs and the Transmission of Extremism: A Comparison of the Far-Right in the Uk and Australia. Lancaster: Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST), 2023, 17–9.

90 Michael Salter, “The Problem With a Fight Against Toxic Masculinity,” The Atlantic, February 27, 2019.

91 Andrea Waling “Rethinking masculinity studies: Feminism, masculinity, and poststructural accounts of agency and emotional reflexivity,” The Journal of Men’s Studies 27, no. 2 (2019): 89.

92 Raewyn W Connell, Gender and power: Society, the person and sexual politics (California: Stanford University Press, 1987), 183.

93 This was largely modelled on the approach adopted by Srinivasan Radhakrishnan, Serkan Erbis, Jacqueline A Isaacs and Sagar Kamarthi, “Novel Keyword Co-Occurrence Network-Based Methods to Foster Systematic Reviews of Scientific Literature,” PloS one 12, no. 3 (2017).

94 Christer Mattsson and Thomas Johansson, ““We Are the White Aryan Warriors”: Violence, Homosociality, and the Construction of Masculinity in the National Socialist Movement in Sweden,” Men and Masculinities 24, no. 3 (2021): 402–4.

95 Nicole Loroff, “Gender and Sexuality in Nazi Germany,” Constellations 3, no. 1 (2011), 49–59.

96 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 39.; Pam Nilan, Josh Roose, Mario Peucker, and Bryan S Turner, “Young Masculinities and Right-Wing Populism in Australia,” youth 3, no. 1 (2022): 286.; Joshua M Roose, Michael Flood, Alan Greig, Mark Alfano and Simon Copland, Masculinity and Violent Extremism (London: Palgrave, 2022), 70.

97 Michaela Köttig, Renate Bitzan and Andrea Pető, Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe (Cham: Springer, 2017), 68.

98 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 14–6.

99 Michael L Allsep, “The Myth of the Warrior: Martial Masculinity and the End of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” in Evolution of Government Policy Towards Homosexuality in the Us Military, ed. James Parco and David Levy (New York: Routledge, 2016), 251–70.

100 Agnieszka Graff, Ratna Kapur, and Suzanna Danuta Walters, “Introduction: Gender and the Rise of the Global Right,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 44, no. 3 (2019): 548.

101 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 15.; Michaela Köttig, Renate Bitzan and Andrea Pető, Gender and Far Right Politics in Europe (Cham: Springer, 2017), 83–5.

102 Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 16.

103 Callum Jones, “‘We the People, Not the Sheeple’: Qanon and the Transnational Mobilisation of Millennialist Far-Right Conspiracy Theories,” First Monday 28, no. 3 (2023).

104 Nicole Loroff, “Gender and Sexuality in Nazi Germany,” Constellations 3, no. 1 (2011), 49–59.; Blu Buchanan, “Gay Neo-Nazis in the United States: Victimhood, Masculinity, and the Public/Private Spheres,” GLQ 28, no. 4 (2022): 489–513.

105 Nicole Loroff, “Gender and Sexuality in Nazi Germany,” Constellations 3, no. 1 (2011), 49–59.

106 Kerry Robinson, “Doing Anti-Homophobia and Anti-Heterosexism in Early Childhood Education: Moving Beyond the Immobilising Impacts of ‘Risks’,’Fears’ and ‘Silences’. Can We Afford Not To?,” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 6, no. 2 (2005): 180.

107 Xinyi Zhang and Mark Davis, “Transnationalising Reactionary Conservative Activism: A Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis of Far-Right Narratives Online,” Communication Research and Practice 8, no. 2 (2022): 132.

108 Joshua M Roose, Michael Flood, Alan Greig, Mark Alfano and Simon Copland, Masculinity and Violent Extremism (London: Palgrave, 2022), 26.; Pablo Castillo Díaz and Nahla Valji, “Symbiosis of Misogyny and Violent Extremism,” Journal of International Affairs 72, no. 2 (2019): 37–56.

109 Elizabeth Ralph-Morrow, “The Right Men: How Masculinity Explains the Radical Right Gender Gap.” Political Studies 70, no. 1 (2022): 34.; Cas Mudde, The Far Right Today (Cambridge: John Wiley & Sons, 2019), 159–60.

110 Raewyn W Connell, Masculinities (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995).

111 Christer Mattsson, and Thomas Johansson, ““We Are the White Aryan Warriors”: Violence, Homosociality, and the Construction of Masculinity in the National Socialist Movement in Sweden,” Men and Masculinities 24, no. 3 (2021): 393–410.; Elizabeth Ralph-Morrow, “The Right Men: How Masculinity Explains the Radical Right Gender Gap,” Political Studies 70, no. 1 (2022): 26–44.; Michael Kimmel, “Racism as Adolescent Male Rite of Passage: Ex-Nazis in Scandinavia,” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 36, no. 2 (2007): 202–18.

112 Joshua M Roose and Joana Cook, “Supreme Men, Subjected Women: Gender Inequality and Violence in Jihadist, Far Right and Male Supremacist Ideologies,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (2022): 1–29.; Simon Copland, “Weak Men and the Feminisation of Society: Locating the Ideological Glue between the Manosphere and the Far-Right,” in Global Perspectives on Anti-Feminism: Far-Right and Religious Attacks on Equality and Diversity, ed. Judith Goetz and Stefanie Mayer, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh, 2023), 116.

113 Blu Buchanan, “Gay Neo-Nazis in the United States: Victimhood, Masculinity, and the Public/Private Spheres,” GLQ 28, no. 4 (2022): 489–513.; Pam Nilan, Young People and the Far Right (Singapore: Springer, 2021), 99–105.

114 Please refer to: James W Messerschmidt, “The Salience of “Hegemonic Masculinity”,” Men and Masculinities 22, no. 1 (2019): 85–91.

115 Blu Buchanan, “Gay Neo-Nazis in the United States: Victimhood, Masculinity, and the Public/Private Spheres,” GLQ 28, no. 4 (2022): 489–513.; Christer Mattsson and Thomas Johansson, ““We Are the White Aryan Warriors”: Violence, Homosociality, and the Construction of Masculinity in the National Socialist Movement in Sweden,” Men and Masculinities 24, no. 3 (2021): 402–4.

116 Xinyi Zhang and Mark Davis, “Transnationalising Reactionary Conservative Activism: A Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis of Far-Right Narratives Online,” Communication Research and Practice 8, no. 2 (2022): 132.

117 Joshua M Roose, Michael Flood, Alan Greig, Mark Alfano and Simon Copland, Masculinity and Violent Extremism (London: Palgrave, 2022), 26.; Pablo Castillo Díaz and Nahla Valji, “Symbiosis of Misogyny and Violent Extremism,” Journal of International Affairs 72, no. 2 (2019): 37–56.

118 Elizabeth Ralph-Morrow, “The Right Men: How Masculinity Explains the Radical Right Gender Gap,” Political Studies 70, no. 1 (2022): 34.; Cas Mudde, The Far Right Today (Cambridge: John Wiley & Sons, 2019), 159–60.