Abstract

This article analyses how and why gender is used in ideological narratives of Salafi-jihadist and extreme right propaganda. It argues that five overarching gendered narratives are leveraged to increase the appeal and resonance of overarching ideological narratives: constructions of a corrupt gender order linked to crisis; constructions of a historically traditional gender order reinstituted by the in-group; portrayals of “good” men and women contributing to solutions and “bad” men and women warranting punishment; constructions of local gendered crises that justify violent action from the in-group; and the juxtaposition of masculinities and femininities to shame or empower audiences into action.

From mothers and brides to monsters and heroes, discourse on gender and extremism is often rife with assumptions. The discussion has been energised in recent years with the furore surrounding the repatriation of Islamic State’s (IS) women, and more recently, with the rise of right-wing extremism and the Tradwife phenomenon. However, women’s political agency, their politico-military and strategic value, and the appeal of Salafi-jihadism and right-wing extremism to women are often downplayed or overlooked. Afterall, why would a woman join a misogynistic and hypermasculine extreme right organisation, or submit to seemingly oppressive religious norms? Conducting a top-down analysis of Salafi-jihadist and extreme right propaganda, with a focus on their gender appeals, can help breakdown assumptions, and provide insight into how and why gender ideology is constructed to target and appeal to audiences.

This study aims to analyse how and why gender is used in ideological narratives of Salafi-jihadist and extreme right propaganda. It applies discourse analysis to four case studies: Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula’s (AQAP) Inspire magazine, IS’s Dabiq magazine, James Mason’s Siege, and Anders Breivik’s 2083: A European Declaration of Independence. It draws on the “linkage” approach to analyse how violent extremist propaganda constructs a “competitive system of meaning” to shape audience perceptions and mobilise support.Footnote1 Violent extremists’ systems of meaning tend to champion an in-group as bearers of solutions and condemn an out-group as creators of crises. According to this literature, constructions of crisis and solutions linked to collective identities are powerful psychosocial forces that can influence identity construction and catalyse support for violent extremism. Our principal aim is to analyse how and why gender is constructed and manipulated within each case study’s system of meaning to target and appeal to audiences.

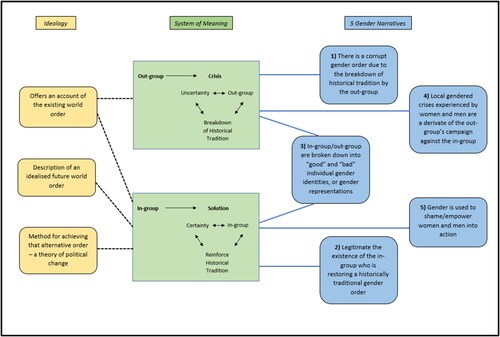

We argue that Salafi-jihadist and extreme right propaganda construct five overarching gendered narratives designed to increase the appeal and resonance of each respective system of meaning. First, narratives that attach a corrupt gender order to the breakdown of historical tradition by the out-group. This corrupt gender order is foundational to crises. Second, narratives that legitimate the in-group by attaching the reinstatement of a historically traditional gender order to the in-group and solutions. Third, narratives that break down collective in-group and out-group identities into individual gender identities, or “gender representations.”Footnote2 Fourth, narratives that justify action from the in-group by portraying local gendered crises caused by the out-group. Fifth, narratives that juxtapose femininities and masculinities to either shame or empower audiences into action. These five gendered narratives are strategically leveraged to personalise systems of meaning and motivate audiences to align their individual gender identity with the in-group by conforming to in-group gender representation expectations.Footnote3 Overall, our study offers the field a framework through which to analyse gendered narratives in violent extremist ideology, as well as the empirical results of applying this framework to Salafi-Jihadist and extreme right primary sources.

This paper begins by situating this study within the context of the academic field. It then establishes a framework for analysing overarching gender narratives in violent extremist propaganda before detailing methodologically how this framework is applied to the contents of Inspire, Dabiq, Siege, and 2083: A European Declaration of Independence. It then presents an in-depth analysis of how and why Salafi-jihadist and extreme right propaganda constructs and leverages gender within ideological narratives.

Literature Review

This study contributes to two streams of research in the literature. The first relates to propaganda analyses of gender in Salafi-jihadist and extreme right propaganda. Analyses of the strategic use of gender in Salafi-jihadist and extreme right propaganda remains a gap in academic discourse. Most studies on Salafi-jihadist gender appeals focus on propaganda appeals to female audiences.Footnote4 For example, Winter, Rafiq and Malik, Musial, Tarras-Wahlberg, Lahoud and Europol analyse Salafi-jihadist primary sources addressing a scholarly gap in how propaganda targets and appeals to women. Van Leuven, Mazurana and Gordon provide important perspectives in the manipulation of masculinities and femininities to motivate both men and women to join IS.Footnote5 Scholarship has also sought to investigate jihadi ideological rulings on female engagement in jihad.Footnote6 While we do not examine jihadi doctrine in this paper, we seek to contribute to broader analyses exploring the relationship between the use of both femininities and masculinities in jihadist propaganda produced by AQAP and IS.

Similarly, there are numerous studies on gender and the extreme right, although few that specifically examine the role of propaganda in association with gender.Footnote7 Some research focuses exclusively on the engagement of women, given that women are typically seen as non-native or incompatible with extreme right ideologies and behaviours, despite evidence to the contrary.Footnote8 Existing research that addresses the gap between the extreme right, gender, and propaganda is less plentiful. In 2018, Mattheis examined narrative frameworks used by women in the extreme right to navigate ideological space, by examining propaganda produced by Lana Lokteff, a far right media personality.Footnote9 Lokteff establishes the “proper” role of women (not as leaders, but as contributors) in the movement, creating or promulgating propaganda concerning women and the defence of white culture and gendered complementarity. Sayan-Cengiz et al. examine visual communication strategies of populist radical right parties in Europe and suggest that visual communication is used to dichotomise native (insiders) and migrant (outsiders) distinctions, with male outsiders framed as threatening alien “others.”Footnote10 Insider women are framed as being representative of the national identity, the spirit of the nation, reproducers, and defenders.Footnote11 Our study builds on this literature by examining the way in which gender is used in extreme right discourse to dictate which constructions of femininities and masculinities belong to the in-group and out-group and why.

The second stream of research relates to studies that apply the “linkage” approach as an analytical framework to violent extremist propagandaFootnote12 and an evaluation mechanism for assessing, preventing, and countering violent extremism messaging.Footnote13 A core contention of the linkage approach is that violent extremist propaganda aims to shape perceptions and mobilise the support of target audiences by deploying rational-choice and identity-choice messaging. This is achieved by constructing a “competitive system of meaning” that champions an in-group as bearers of solutions and condemns an out-group as creators of crises. This study contributes to this stream of research by using the linkage approach to conduct discourse analysis of Salafi-Jihadist and extreme right propaganda. Specifically, we use the linkage approach to analyse constructed systems of meanings and identify how and why gender is used within these broader ideological narratives.

To these ends, we found that gender is used in five key ways to increase the appeal and resonance of each case study’s system of meaning. First, narratives that attach a corrupt gender order to the breakdown of historical tradition by the out-group. Second, narratives that legitimate the in-group by attaching the reinstatement of a historically traditional gender order to the in-group and solutions. Third, narratives that break down collective in-group and out-group identities into individual gender identities. Fourth, narratives that justify action from the in-group by portraying local gendered crises caused by the out-group. Fifth, narratives that juxtapose femininities and masculinities to either shame or empower audiences into action. We therefore offer a unique contribution across both streams of literature. By situating these five gendered narratives within systems of meaning, this study develops a framework that can be adopted by other scholars to identify gendered narratives in violent extremist propaganda, analyse the relationality between the use of femininities and masculinities, and importantly, situate gender within overarching violent extremist ideological narratives. Therefore, this study offers the field a framework to analyse gender in violent extremist propaganda, as well as the results of applying this framework to Salafi-jihadist and extreme right primary sources.

Analytical Framework

Three concepts underpin the analytical framework applied in this study: propaganda, ideology, and gender. This study understands propaganda as a process pertaining to the deliberate and systematic use of discourse to sow, germinate, and cultivate ideas to shape the perceptions and behaviours of a target audience in a way that benefits the propagandist.Footnote14 Closely related is ideology. We draw on political and psychosocial analyses of identity-based movements to define ideology as a system of values, beliefs, and narrative constructs that provide an account of the existing world order by shaping audience perceptions of identity, advocate for an alternative idealised future, and motivate individual and collective action toward socio-political change to achieve that future.Footnote15 We understand gender as the socially constructed expectations of what it means to be a woman and man, with the primary purpose of achieving political objectives.Footnote16 The differences between what constitutes femininities and masculinities are contextual, evolving to the socio-political and military context they are contained within, and the governing cultural values and beliefs. As one performs their gender, they perform their individual identity, and determine membership to a collective identity.Footnote17 We aim to analyse how and why gender is used in ideological narratives of Salafi-jihadist and extreme right propaganda by first applying the “linkage” approach to examine their “competitive systems of meaning.”

The Linkage Approach to Analysing Violent Extremists’ “Competitive Systems of Meaning”

According to “linkage,” the overarching strategy of extremist propaganda is to shape perceptions and mobilise the support of audiences via a mix of rational-choice and identity-choice appeals.Footnote18 This combination of appeals promotes the propagandist’s “competitive system of control” (i.e. their politico-military activities),Footnote19 and provides audiences with a “competitive system of meaning.” In line with our understanding of ideology, this competitive system of meaning is an alternative frame for audiences to view, interpret, and understand the world by playing on in-group, out-group, solution, and crisis constructs. This frame creates a dichotomised perception of the world by championing an in-group as bearers of solutions and demonising the out-group as the cause of crisis. These psychosocial processes can play central roles in motivating in-group support while justifying the exploitation and targeting of the out-group.Footnote20

Ingram contends that identity construction is particularly influenced by two psychosocial factors: “perceptions of crisis” and “solutions.”Footnote21 Perceptions of crisis tend to be “characterised by uncertainty, the breakdown of tradition, and the influence of the Other.”Footnote22 Feelings of uncertainty can motivate individuals to engage in “uncertainty-reduction”Footnote23 behaviour that re-establishes security, stability, and their identity.Footnote24 Contributing to feelings of uncertainty is the breakdown of tradition, which “refers to the perception that historically rooted norms of belief and practice associated with the in-group identity are changing due to the influence of the Other.”Footnote25 The Other, or the out-group, is the cause of the breakdown of tradition and uncertainty, presenting an existential threat to the in-group. Attaching the out-group to “perceptions of crisis” offer audiences a simple explanation of the existing world order where the in-group is existentially threatened by the out-group.

“Solutions” are characterised by certainty, reinforcement of tradition, and commitment to the in-group.Footnote26 While the out-group is the cause of crisis, the in-group restores certainty and reinforces tradition by offering audiences security and a stable collective identity. Self-categorising to an in-group reduces uncertainty by providing “a consensually validated group prototype that describes and prescribes who one is and how one should behave”Footnote27 thereby shaping an individual’s perception of the world, their sense of self, and feelings of security.Footnote28 While the out-group sets the boundaries of how not to behave, the in-group represents how to behave to gain membership as part of a collective, directly weaken adversaries (the out-group), and contribute to “solutions.”Footnote29 As argued by several scholars,Footnote30 these psychosocial influences can play central roles in catalysing support for violent extremist groups that offer a “prototype” for audiences to emulate, prescribing behaviours, attitudes, and beliefs.Footnote31 Narratives attaching the in-group to solutions (certainty, reinforcement of tradition, and commitment to the in-group) are thus diametrically opposed to out-group/crisis constructs, providing audiences with an alternative idealised future and method for achieving socio-political change.

The Propaganda-Ideology-Gender Nexus: Situating Gender within Extremists’ Systems of Meaning

Through the process of applying linkage, this study identified five gendered narratives that are intrinsic to violent extremist “systems of meaning” (see Footnote32). This paper contends that these five gendered narratives are designed to increase the resonance of each respective “system of meaning” by personalising narratives through gendered appeals. First, the breakdown of historical tradition by the out-group has resulted in a corrupt gender order. This corrupt gender order is characterised by “gender dissidents” (women and men who transgress “correct” gender performances) who jeopardise the in-group’s broader socio-political order or alternative idealised future. This corrupt gender order causes women’s and men’s personal crises and threatens the existence of the in-group. Therefore, this first gendered narrative construct offers audiences an account of the existing world order where a corrupt gender order is central to the in-group’s demise. out-group.

In contrast, the second gendered narrative aims to legitimate the existence of the in-group by portraying the in-group as restoring a historically traditional gender order. The restoration of this gender order is portrayed as a method to denigrate the out-group and generate certainty by restoring historical tradition and achieving an idealised socio-political order more broadly. Restoring historical tradition and reinstituting the “correct” gender order is thus intrinsically tied to solutions. Therefore, the second gendered narrative offers a description of an alternative order, with the reinstatement of traditional gender order being foundational to achieving that broader socio-political objective.

The construction of a gender and conjugal orderFootnote33 is thus central to violent extremist systems of meaning. This paper follows Mackenzie and George’s conceptualisation of conjugal order as gendered and sexual behaviour that is regulated and policed by formal rules and informal norms and behaviours that work to uphold certain behaviours for women and men, such as maintaining women’s reproductive responsibilities. Similarly, Butler asserts that the construction of a gender order through “right” and “wrong” social performances “serves a policy of gender regulation and control.”Footnote34 As George contends,Footnote35 the policing of conjugal order can work to reinforce the idea that only those whose gendered behaviour is considered to be “correct” are worthy benefactors of protection, while those whose gendered behaviours are “incorrect” threaten the conjugal order, rendering the individual as not only unworthy of protection, but in the case of violent extremist narratives, as warranting violent retribution. Therefore, portrayals of gender transgressors who characterise a corrupt gender order, and in contrast, gender conformers who uphold the conjugal order are central to violent extremists’ competitive systems of meaning.

The third gendered narrative breaks down in-group and out-group collective identities into individual gendered identities,Footnote36 or what Ingram conceptualises as gender representations.Footnote37 This is achieved by attaching positive or negative values and performances that the propagandist claim directly contribute to solutions or crises, which in turn, distinguish each representation as part of the in-group or out-group.Footnote38 As theorised above, perceptions of crisis can disrupt identity and drive individuals to engage in behaviour that reaffirms their threatened identity.Footnote39 Systems of meaning offers audiences an “anxiety-controlling mechanism reinforcing a sense of trust, predictability, and control in reaction to disruptive change by reestablishing identity or formulating a new one.”Footnote40 However, reaping the benefits of membership to an in-group requires performing the identity expectations of that group.Footnote41 Indeed, identity (and gender) is made and re-made in everyday life.Footnote42 As individuals perform their gender by adhering to in-group gender representations, they attain securityFootnote43 by affirming membership to a collective identity.

In-group gender representations comprise a gender order that is foundational to achieving the in-group’s broader socio-political objectives and advancing an idealised future.Footnote44 As a result, the gendered values and behaviours attached to in-group representations are actions that directly benefit the in-group (or the propagandist), while values and behaviours attached to out-group representations undermine them. The performances attached to each in-group gender representation are explicit articulations of the methods, at an individual level, to achieve socio-political change towards the in-group’s idealised future. Therefore, the third gendered narrative aims to shape audience’s individual gender identities to not only align with the in-group, but to create a gender order that advances the in-group’s socio-political and military objectives toward an idealised future.

The fourth gendered narrative portrays women and men experiencing local gendered crises which are framed as a derivative of the crisis caused by the out-group.Footnote45 A common example of a local gendered crisis across both Salafi-jihadist and extreme right propaganda is of in-group women being unjustly targeted and sexually violated. Gendered messaging is thus used here to localise and personalise experiences of collective crisis, situating crisis at the individual level so that conflict is not just occurring at a distance. This has two intended purposes. First, linking gendered crises to the out-group’s campaign against the in-group motivates audiences to align their individual gender identity with the in-group (achieved by performing in-group gender representation expectations). Second, gendered messaging aims to demonstrate that the in-group is not only aware of gendered injustices women and men face, but also that those gendered injustices are the in-group’s raison d’être. While the out-group is the cause of women and men’s localised gendered crises, the in-group is the purveyor of women and men’s salvation. Therefore, the fourth gendered narrative justifies actions taken against the out-group by portraying women and men as victims of local gendered crises.

The fifth gendered narrative is one of complimentary contrasts. There is a symbiotic relationship between femininities and masculinities, “where depending on the narrative and target audience, gender is used to either shame or empower women or men and motivate action.”Footnote46 For example, violent extremists use gendered messaging to portray in-group women and men as obligated to be the solution to each other’s gendered crises. This promises female and male audiences mutually beneficial relationships of support and protection. For instance, women are often portrayed as victims needing saving by their male counterparts to encourage and empower male audiences to act. Conversely, women portrayed as stepping into masculinised roles for the benefit of the in-group are leveraged to shame inactive men. The female and male representations are therefore relational. Analysing how Salafi-jihadist and extreme right propaganda prioritise these five gendered narratives offers unique insights into how each extremist milieu wants their audiences to view the world, how to act, and how to view gender and power relations.

Case Selection and Methods

This paper is based on primary source analysis of two Salafi-jihadist and two extreme right propaganda items: AQAP’s Inspire magazine (17 issues) and IS’s Dabiq magazine (15 issues), compared to James Mason’s Siege, and Anders Breivik’s 2083: A European Declaration of Independence. Designed by Anwar al-Awlaki and Samir Khan, Inspire was the first English-language magazine published in 2010 by AQAP’s al-Malahem media foundation. Its focus was to “…inspire the believers to fight [al-Anfal: 65]”Footnote47 and most notably, to facilitate “individual jihad” with instructional material in the “Open Source Jihad” section. IS’s al-Hayat Media Centre launched Dabiq in July 2014 following the declaration of the self-proclaimed Caliphate on 29 June 2014.

The extreme right propaganda items are drawn from the violent neo-Nazi/white supremacist milieu. Mason’s Siege is an anthology of ideologically-informed propaganda pieces authored by Mason and contemporaries in the 1980s.Footnote48 While Siege does not provide direct instructional material like Inspire, it provides strategic advice on matters such as terrorism and resistance, in addition to ideological commentary. Breivik’s 2083 manifesto was released in conjunction with his Oslo attacks in 2011, when he bombed the Norwegian Prime Minister’s office block and attacked a youth camp on Utøya island with firearms.Footnote49 It provides direct advice on strategy and tactics, in addition to lengthy (and in some cases plagiarised) treatises on ideological concerns.

We analyse how and why gender is used in ideological narratives via two steps. The first applies the linkage approach to examine each item’s competitive system of meaning.Footnote50 Analysing systems of meaning in each case study enables the identification of their respective ideology: an account of the existing world order, advocation for an alternative idealised future, and the method for achieving socio-political change to achieve that alternative future. Through the process of applying this framework, we identified the five gendered narratives that are used to amplify the reach and resonance of each respective system of meaning. Thus, the second step conducts discourse analysis to examine how and why these five gendered narratives are constructed in relation to each respective system of meaning.

Analysis

Gender ideologies constructed within systems of meaning via the five gendered narratives offer audiences a more local and personalised frame through which to view and understand themselves and their place within the world. They depict an alternative and historically traditional gender order reinstituted by the in-group, in opposition to the out-group’s corrupt gender order, and foundational to achieving the in-group’s idealised future. While each case study similarly constructs an overarching system of meaning between a dichotomised in-group bearing solutions and out-group causing crises, nuances in ideological gendered narratives reflect divergence in socio-political and military objectives. These differences demonstrate how violent extremists’ gender orders are constructed dependent on strategic and socio-political context. The strategic logic that can be extrapolated from these findings is significant because it highlights the role that gender in propaganda can play in motivating audiences to perform and fulfil the specific gendered expectations of violent extremists contingent upon ideology, strategic conditions, and socio-political objectives.

Salafi-Jihadist

It is necessary to understand the strategic context within which Inspire and Dabiq were produced. In 2003–2004, following the routing of Al Qaeda (AQ) training camps in Afghanistan, AQ sought to shift its military strategy to, “…concentrate the research methods of the open fronts, and the methods of individual jihadi operational activity.”Footnote51 According to Abu Mus’ab al-Suri, the conditions after the September 11 events necessitated the decentralisation and globalisation of individual jihad to exhaust “the enemy by attacking his interests world wide.”Footnote52 For example, al-Suri writes,

But any Muslim, who wants to participate in jihad and the Resistance, can participate in this battle against America in his country, or anywhere, which is perhaps hundreds of times more effective than what he is able to do if he arrived at the open area of confrontation.Footnote53

AQ shifted to encouraging individuals, focusing on men, to carry out attacks around the world as opposed to travelling transnationally to training camps.Footnote54 Jihadist propaganda disseminated on the internet became central to this effort.Footnote55 Indeed, a consistent and infamous section throughout Inspire magazine is “Open Source Jihad” providing technical and operational advice to its supporters.Footnote56 This broader strategic context shapes AQAP’s system of meaning and its gender ideology.

Inspire’s system of meaning aims to motivate individuals globally to engage in individual jihad by demonstrating to audiences that “their actions are not just justified, but an urgent necessity within at least a wider politico-military strategy if not a cosmic struggle”Footnote57 against a global enemy led by the United States. Inspire leverages the five gendered narratives to personalise its system of meaning and increase urgency towards action. For example, Inspire’s constructed corrupt gender order describes gender transgressors exacerbating crisis.Footnote58 The United States’ corrupt gender order is framed as central to the in-group’s demise, and weaponised against in-group men:

…But also that is not unexpected from a nation that is leading the world into a moral decay that makes humans equal to animals. In fact animals have more values than some Americans. It is part of their so-called civilization to turn women into a roaming toilet which could be used casually by men. One of the things that bothered us in prison was their attempts to seduce us through their women but all praise is due to Allah, we were protected from this human trash.Footnote59

Reflecting emphasis on individual jihad, AQAP’s historically traditional gender emphasises the need for in-group men to choose between “…hijrah [emigration] or jihad. You either leave or you fight. You leave and live among Muslims or you stay behind and fight with your hand, your wealth, and your word.”Footnote62 This message is reinforced with a diversity of messaging, such as poetry, “What to expect in Jihad” sections, celebrating martyrs, and history and strategy articles justifying individual jihad as a means to persuade male audiences that it is their moral, strategic, and jurisprudential obligation to align with in-group male representation expectations. This justification is then followed with operational guidance on how to conduct individual jihadi operations in “Open Source Jihad.”

While emphasis is placed on in-group male representations due to AQAP’s politico-military strategy, female representations are leveraged in four ways to reinforce Inspire’s traditional gender order. First, in-group women, such as mothers, sisters, and wives, are praised for committing to their Muslim identity and traditional roles in the private sphere.Footnote63 For example, Umm Yaha writes, “O mother of the upcoming Mujahideen, the obligation and responsibility to teach and enlighten your children lies on your two shoulders…you should immunize them from falsification and deception…”Footnote64 Second, in-group women are portrayed as victims of gendered crises at the hands of the out-group, such as being indiscriminately killed by enemy forces,Footnote65 raped,Footnote66 or persecuted and imprisoned.Footnote67 Often, feminised victims are contrasted against masculinities to shame or empower men into action, thereby motivating male audiences to adhere to in-group male representations.

“The West should ban the Niqab covering its real face” captures these strategic dynamics. The article begins by portraying a corrupt gender order as the cause of local gendered crises for Muslim women in the West: “But the West is hiding behind a niqāb of human rights, civil liberties, women”s rights, gender equality and other rallying slogans while in practice it is being imperialistic, intolerant, chauvinistic and discriminating against the Muslim population of Western countries.’Footnote68 Inspire then aims to empower in-group women by demonstrating how commitment to their Muslim identity can solve this gendered crisis:

For this reason we promote that Muslim women in the West who do not view wearing niqāb as being a religious duty…to wear the niqāb as a public sign of their rejection of forced assimilation, as a symbol of their pride at being Muslim, as a public statement that is carried as a badge of honor in face of a decadent Western way of life.Footnote69

With the wars of niqāb being fought out and the defamation of Muĥammad continuing…one should only expect the West to remain a field of operation for the mujāhidīn. Within a short span of time there was Fort Hood, the operation of ‘Umar al-Fārūq, the attempt against the Swedish cartoonist and finally Times Square.Footnote70

Third, out-group women are condemned for threatening the traditional gender order, undermining AQAP’s socio-political objectives, and exacerbating crises. For example, Anwar Al-Awlaki portrays a female transgressor who started the “Everybody Draw Mohammed Day” as instigating a “nationwide mass movement of Americans joining their European counterparts in going out of their way to offend Muslims worldwide” and “should be taken as a prime target of assassination.”Footnote71 Al-Awlaki leverages this crisis to mobilise audiences to action and justifies retribution against out-group women by portraying a historically traditional gender order where the killing of women who defame the Prophet is permitted and central to solutions.Footnote72 Thus, out-group female representations are leveraged to personify the out-group’s corrupt gender order, demonstrate to female audiences how not to behave, and encourage in-group men to carry out retributive attacks.

The fourth portrayal, while infrequent throughout Inspire, praises combatant women. For example, Roshonara Choudhry is celebrated for carrying out an attack in London.Footnote73 However, the article refrains from explicitly calling on women to follow Choudhry’s example. Rather, Inspire leverages Choudhry’s actions to shame men into action:

A woman has shown to the ummah’s men the path of jihad! A woman my brothers! Shame on all the men for sitting on their hands while one of our women has taken up the individual jihad! She felt the need to do it simply because our men gave all too many excuses to refrain from it…To the men of the ummah: Take the example of this woman and you will find success in the afterlife.Footnote74

In contrast to Inspire’s emphasis on individual jihad, IS’s Dabiq promotes its five-phase insurgency manhaj (method) for establishing a Caliphate, and aims to legitimise IS as a divinely guided politico-military actor by portraying its manhaj as tried and tested in theory, practice, and jurisprudence.Footnote77 Throughout its history, IS has shifted “up” towards greater politico-military conventionality during times of strength comparative to adversaries – such as in parts of Iraq and Syria between 2014 and 2016 – and shifted “down” during periods of comparative weakness towards unconventional guerrilla operations – such as after its territorial defeats beginning in 2016.Footnote78

Dabiq’s 15 issues were released from 2014 to 2016 during IS’s period of strength when it engaged in more conventional warfare and sought to implement social, economic, and political initiatives. During this time, IS’s system of meaning and gender ideology portrays the in-group (IS and aligned Sunni Muslims) as the purveyors of women’s and men’s salvation through security and stability, where both women and men not only benefit from IS’s systems of control but are central to its effective implementation. To achieve this, Dabiq constructs a gender order that advances IS’s objectives by encouraging audiences to fulfil the duties needed for a functioning polity. For example, Ingram’s analysis of IS’s gender representations found that in-group female representations “mother/sister/wife” and “supporter” are prioritised the most frequently throughout Dabiq. “Supporters” are women in the West who must perform hijrah to the CaliphateFootnote79 where they are promised purpose and security in the Caliphate with powerful roles as a “mother” raising the next generation of lion cubs, a supportive wife, and membership to an everlasting “sisterhood.” Dabiq’s “To Our Sisters” section positions these female roles as being equally as important as men’s roles in achieving solutions:

O sister in religion, indeed, I see the Ummah of ours as a body made of many parts, but the part that works most towards and is most effective in raising a Muslim generation is the part of the nurturing mother.Footnote80

The use of in-group male representations reflects IS’s politico-military objectives during this time. Dabiq uses positive and empowering portrayals of men as fighters,Footnote84 fathers/brothers/husbands,Footnote85 martyrs,Footnote86 supporters who repent, give bay’ah (pledge allegiance) and perform hijrah,Footnote87 and as workers who implement governance.Footnote88 For example, workers are framed as selfless pious men who personify IS’s rational-choice appeals, delivering essential services and provisions needed for the survival of the Ummah. Indeed, Dabiq emphasises that while men of the Caliphate are eager to fight kufr, “true” Muslim men understand that a “state cannot be established and maintained without ensuring that a portion of the sincere soldiers of Allah look after both the religious and worldly affairs of the Muslims.”Footnote89

This diverse range of in-group male representations symbolises a functioning Caliphate that is providing for the population, “remaining and expanding”Footnote90 and building the ranks. Furthermore, positive portrayals of women and men work to accentuate appeals to gendered audiences. The use of “father/brother/husband” in conjunction with “mother/sister/wife” representations demonstrates that supporters are not just joining IS to fight, but to live. Women are promised belonging to an everlasting “sisterhood,” a supportive “husband” and a strong “father” for their children, and men are promised a “wife,” belonging to a “brotherhood,” and a “mother” for their children. Promoting social relations between Caliphate inhabitants is an important strategy for IS which aims to prevent defection. As Kinnvall and Giddens assert, “trust of other people is like an emotional inoculation against existential anxieties – ‘a protection against future threat and dangers which allows the individual to sustain hope and courage in the face of whatever debilitating circumstances she or he might later confront.”’Footnote91

Dabiq’s conjugal order punishes out-group female and male representations who undermine IS’s socio-political objectives, exacerbate crisis, and thus characterise the out-group’s corrupt gender order. For example, out-group women and men are those who do not perform hijrah,Footnote92 do not pledge bay’ah,Footnote93 and men who do not wage jihad.Footnote94 To motivate Western audiences to perform hijrah, Dabiq details how the West creates concepts which are “dictated by financial interest and sexual instinct,” to enable the “role of man and woman” to become mixed up, resulting in women not being a “mother, a wife, or a maiden’ but instigating the legislation of “marijuana, bestiality, transgenderism, sodomy, pornography, feminism, and other evils.”Footnote95 Dabiq emphasises, however, that women (and men) can save themselves from crises through commitment to the in-group:

The Western way of life a female adopts brings with it so many dangers and deviances…She is the willing victim who sacrifices herself for the immoral “freedoms” of her people, offering her fitrah on the altar of secular liberalism. If she feared for her soul, she would reflect on where the paths of Christian paganism and democratic perversion continue to lead her…The solution is laid before the Western woman. It is nothing but Islam, the religion of the fitrah.Footnote96

These findings demonstrate that Salafi-jihadist propaganda symbiotically manipulates the five overarching gendered narratives to increase the appeal and resonance of their competitive systems of meaning, and strategically construct a gender order that is foundational to achieving politico-military ends. Reflecting AQAP’s emphasis on individual jihad, Inspire’s gender order encourages in-group men to wage individual jihad globally to save themselves, victimised women, and the transnational Ummah. In contrast, Dabiq’s gender order is characterised by a diverse range of in-group female and male representations whose roles are portrayed as equally as important in establishing and maintaining the functions of a governing polity.

Extreme Right

The genealogy of extreme right systems of meaning cannot be so precisely articulated as with AQAP and IS. The extreme right is less cohesive, noteworthy for its historical embedment and enduring ideology. For example, the individual jihad promoted in Inspire can be identified in the extreme right writings in 1983. Louis Beam, a prominent member of the Ku Klux Klan and Aryan Nations in the United States, published “Leaderless Resistance” (subsequently revised and republished in 1992), which championed lone or small cell terrorism as a viable strategy to circumvent the oppressive power of the state.Footnote103 Groups, Beam argues, are too prone to infiltration, disruption, or surveillance. Disconnected, de-centralised phantom cells were his solution, acting in cooperation without direction or communication, but connected via newspapers, leaflets, and current affairs. Communications such as propaganda therefore become essential for the cells/actors to determine when it is time to act. Right-wing lone actor attacks, such as Breivik’s attack in 2011, Dylann Roof’s attack at Charleston Church in 2015, Robert Bower’s Tree of Life synagogue attack in 2018, Brenton Tarrant’s Christchurch attacks in 2019, and Patrick Crusius’ El Paso attack in 2019, demonstrate the endurance of the leaderless resistance concept.

While Siege was produced in the US neo-Nazi context, and 2083 in the Norwegian white supremacist context, they nonetheless contain ideological markers representative of common positions pervading the extreme right in Western liberal democratic settings. For example, disenchantment with the current order, with beliefs that society is corrupt and in decline, and that this decline poses an existential threat to the “white race.” Democracy is seen as part of the corrupt order, perverted by enemies such as Jews, Muslims, or the political left. Progressive policies, such as those that advance multiculturalism and equality, are viewed as threats to the in-group. It is common for extreme right propaganda to express a siege-mentality, where the in-group is portrayed as beset on all sides. As Mason expresses,

It’s all meaningless now. It was a White society with White Men, White Women and White Children. White families. White culture. White values. Up until the Fifties, if you weren’t White - including Jews - you either played it White or you didn’t exist. If you were a druggie, you kept it hidden, or else. There was an Ideal - though it was too poorly defined and not at all effectively enforced - and it was a White Ideal. It was slowly eroded to the point where, today, there is nothing left of it.Footnote104

This siege-mentality is leveraged to encourage violent and other forms of illicit or undemocratic strategies and tactics.Footnote105

This context shapes the system of meaning and gendered narratives contained within our extreme right case studies. Siege, for example, contains extensive ideological theorising united with strategic advice to accelerate the decline of society for a new world order. A corrupt gender order is depicted as inseparable from the decline of the so-called “white race.” The demise of the in-group is often coached in terms of racial survival, miscegenation (a derogatory term for biracial relationships) and the declining white birth-rate. The artificer of this crisis extends across multiple out-group identities: the Political Left, feminists, gender and ethnic minorities, and religious groups, such as Jews and Muslims. In 2083, the corrupt gender order is attributed to Jewish people, especially those associated with the Frankfurt SchoolFootnote106 and Cultural Marxism:

…the Critical Theorists of the Frankfurt School recognised that traditional beliefs and the existing social structure would have to be destroyed and then replaced. The patriarchal social structure would be replaced with matriarchy; the belief that men and women are different and properly have different roles would be replaced with androgyny; and the belief that heterosexuality is normal would be replaced with the belief that homosexuality is equally “normal.”Footnote107

Ever notice the typical Right Wing married couple? The little lady is ever bitching at hubby to drop that garbage and get a better-paying job. His own kids see him as a poor man’s Archie Bunker. That’s on a good day. The rest of the time it is off to divorce court. Why? Is the Movement really garbage? Are these women really bitches? The answer is no. The problem in every case lies with the man. The U.S. Right is made up of frustrated men, men who are afraid of this or that or the other and seek the company of others who are similarly frustrated and frightened in order to be able to ease their angst and perhaps work out some of their fantasies. What woman on earth would respond to that?Footnote109

Depictions of a corrupt gender order aim to instil a sense of crisis where so long as the perception of threat and peril to the gender order is maintained and linked to the out-group, then the requirement to act is maintained. The reinstitution of a historically traditional gender order is framed as essential for survival and salvation. According to Mason,

[Charles] Manson had the right idea about Family. It involved people of the same Race, the same Spirit, coming together for mutual security…Hand-in-hand with revolution, with survival, is the elemental component of the Family. It is really the only way the System can be destroyed, really the only way we can survive. TRIBES of White Warriors, bands of White Men with their Women and Children who have drawn together and then pulled away from the System to allow it to fall without taking them with it.Footnote110

Evidently, these traditional orders are often idealised, simplified, or imagined, overlooking the detail from those historical periods which challenge the given interpretation. For some, their historically traditional gender order is rooted in the 1950s, drawing on the nuclear family ideal and conjugal order. In 2083, it is argued that:

Most Europeans look back on the 1950s as a good time. Our homes were safe, to the point where many people did not bother to lock their doors. Public schools were generally excellent, and their problems were things like talking in class and running in the halls. Most men treated women like ladies, and most ladies devoted their time and effort to making good homes, rearing their children well and helping their communities through volunteer work. Children grew up in two – parent households, and the mother was there to meet the child when he came home from school.Footnote111

Like Salafi-jihadist propaganda, these narratives depicting the return to a purer way of living aim to convince audiences to conform to restrictive and heteronormative gender identities. A choice is presented to return to a golden age or purer times and a more authentic way of living:

The time of the individual choice is upon every White Man and Woman, within or without the Movement. Argument is fading fast and being replaced by: will you have a White world and an environment in which you can live or not?Footnote112

In detailing the expectations of in-group gender representations, the extreme right provide audiences with a template for how to behave and perceive others within an ideal gender and conjugal order. For example, in Siege, in-group women are promoted as valuable to the struggle, capable of ideological adherence, but incapable of leadership: “Women make the most excellent fanatics but they have to be properly motivated and LED. There is something very wrong with any organization that doesn”t have its share of women.’Footnote113 Such narratives aim to empower women in the movement as important contributors, while nonetheless limiting the scope of their involvement to reserve leadership for men.Footnote114 In contrast to Salafi-jihadist propaganda, another limitation to operational engagement is motherhood:

Hence, it is probably best that a WLF member remain single - at least in the eyes of the State – and women who desire an active role in terrorism against the System cannot afford to have dependent children. Movement morality must be fitted to the person and specialties of the operations involved.Footnote115

…religious, “apart” quality. They are in fact very moral, quaint in many ways, naïve in some ways, polite, soft-spoken, but more fiercely dedicated than most I’ve known calling themselves National Socialist. They are scrupulously honest. They bewilder me at times. They are very, very slick. They are keenly intelligent and usually know what you’re about to say before you say it. They resent the image made for them by the media far, far more than we resent the one that has been made for us. We laugh at and enjoy ours while they are outraged and indignant over theirs…Racially, they are all tops.Footnote116

This articulation of the “good woman” as a demure, well-behaved, willing, involved and quietly intelligent is nonetheless also one of a woman who defers to and is led by men. This provides an insight into the gender order which can permeate extreme right propaganda, as has been noted elsewhere.Footnote117

Out-group women exacerbate the crisis by having biracial relationships, non-forming sexual values, political differences (often construed as stupidity) or by association with out-groups. Women associated with out-groups are portrayed as ideological enemies, and as sub-human. As Mason states, “A favorite line when asked if we would condone the killing of women and children in the event of an all-out race war is one whereby I correct the language by adding, “You mean females and offspring?””Footnote118 Dehumanising out-group women aims to justify their death, as re-emphasised in the Christchurch manifesto which explicitly called for the killing of Muslim women and children.Footnote119 Similarly, 2083 contains vitriolic castigation of out-group women with immoral sexual freedoms:

I have several other promiscuous (slut) friends and I could list at least 30 male and females in my social environment if I wanted to. I don’t blame them personally and it has absolutely nothing to do with envy. I could easily have chosen the same path if I wanted to, due to my looks, status, resourcefulness and charm. It’s just terribly sad that my country have [sic] been the victim of severe Marxist infiltration leading to the political doctrines which have been allowed to destroy all moral and norms, resulting in the complete breakdown of our once great ethical standards.Footnote120

In-group men are not as frequently dissected as women. Like Salafi-jihadism, however, there is clear veneration of male heroes who act decisively, instinctively, and violently. Mason promotes the letter of Frank Spisak, a neo-Nazi serial killer who wrote, “It does give me a great sense of satisfaction knowing I went down with my guns blazing and took out several of the Enemy before they got me.”Footnote122 Mason himself cultivates the image of the ideal insider as an anonymous “man of action,” eloquent and charming, and intelligent enough to realise that the enemy would never allow a white knight or superheroes to emerge.Footnote123 For instance, Mason describes men who are the “crystalising Aryan force” as misunderstood wild men or losers who can achieve the great Aryan victory:Footnote124

Lonely, solitary, hermitic, these "men of deep insight and feeling who feel estranged in the masses of robot-like intellectuals and vapid women…" move to the fringes where they enjoy leisurely and silent observation. Thus detached, they become ‘other-worldly’, relatively immune to social and cultural vicissitudes and epiphenomena: such individuals become a warrior class, a corps of lethal portents, are willing to sally into the deadly fray, and are safe from the disappointments and let-downs of normal men.Footnote125

A similar picture is painted in 2083, invoking historical male warriors such as medieval knights and soldiers as in-group male representations. Across both manuscripts, in-group men are seen as the only salvation for the future, and the last line of defence of European civilisation.

In contrast, out-group men are portrayed as part of the political left (a banner used to catch Cultural Marxists, feminists, out-group women, homosexuals, and other minority groups).Footnote126 Out-group men are thus enemies of traditional masculinity, effeminised by the political left, and worthy of public humiliation and punishment.Footnote127 For example, Breivik writes that, “Indeed the feminisation of European culture is nearly completed. And the last bastion of male domination, the police force and the military, is under assault.”Footnote128 In a curious contrast, some extreme right-wing narratives describe out-group men as weak, emasculated, enslaved, or living in fear or cowardice, while simultaneously powerful enough to imperil in-group gender ideals.Footnote129 For instance, 2083 states,

As the social revolutionaries readily proclaim, their purpose is to destroy the hegemony of white males. To accomplish this, all barriers to the introduction of more women and minorities throughout the “power structure” are to be brought down by all means available. Laws and lawsuits, intimidation, and demonising of white males as racists and sexists are pursued through the mass media and the universities.Footnote130

And,

There is no doubt in the media that the “man of today” is expected to be a touchy-feely subspecies who bows to the radical feminist agenda. He is a staple of Hollywood, the television network sitcoms and movies, and the political pundits of talk shows. The feminisation is becoming so noticeable that newspapers and magazines are picking up on it.

Confronted with this seemingly united and faceless apparatus, in-group gender representations are seen to be in crisis.Footnote131

These narratives leverage personal gender crises as being perilous enough to legitimise direct action. For example, in 2083, Breivik attributes personal gender crisis to Muslim immigrants. Indeed, for the last decade or so, Muslims have increasingly been considered a malevolent out-group, either through their birth rates exceeding that of white couples, being portrayed as sexual predators of white women, or subversive, using their wealth to purchase positions of power (often referred to as the Eurabia Project conspiracy).Footnote132 Breivik portrays sexually predatory Muslim men who prey upon innocent white women and suggests that historically, women, boys and girls have been sold as slaves or raped by Muslim forces, with Christian women especially being forced into sexual slavery or harems as standard Muslim practice.Footnote133 According to Breivik, Christian men were castrated and forced into becoming eunuchs or enslaved for strategic political purposes and thus encouraged by local elites.Footnote134 This historical degradation of the in-group is juxtaposed against contemporary times where white women are abused by Muslim men:

Muslim girls were off limits to everyone, even the Muslim boys. The only available “commodity” at this point was therefore ethnic Norwegian girls, referred to as “whores.” Due to the tolerance indoctrinated through Norwegian upbringing - girls aren’t brought up to be sceptics, racists or anti-immigrant, just like most boys. They are all brought up to be very tolerant. As a result, many ethnic Norwegian girls, especially in Muslim dominated areas, despise ethnic Norwegian boys because they consider them as weak and inferior with lack of pride, seeing as they are systematically “subdued” by the “superior Muslim boys.” Ironically, Muslim boys are raised to view Norwegian girls as inferior “whores.” Their only purpose is to bring pleasure until the Muslim guys are around 20–25 when they will find a pure, “superior” Muslim girl, a virgin.Footnote135

Much like examples elsewhere, the inaction of in-group members, coupled with crisis narratives, are used to motivate the in-group to shame or empower them to action. Mason, when discussing the demonisation of the husband and father as the “bad guy” suggests that essential to the “Systems” conditioning was turning wives and children against their husbands. This was accomplished due to the complicity of American men:

Yes, they ARE mainly jerks and impotent buffoons deserving all the kicks the alien, anti-White System wants to deal them. For they are the ones who ALLOWED all of this to take place and come to pass. In this sense, the System media is flogging a dead horse to an almost cosmic degree.Footnote136

This is matched with narratives of in-group greatness and hope. At times, this means imitation of their ideological enemies. Mason, writing of the supposed elitism of Jews, suggests “we, like the Jews, must come to view ourselves as an elite, as a BREED APART from any other, because it is our DESTINY to do so.”Footnote139 Narratives which exploit ethnic separatism, historical unity and triumph are also leveraged to suggest that the vision of good society is both achievable and realistic.

Things change. They can change for the worse, but they can also change for the better. Our ancestors, better men and women than we are, held the line against Islam for more than one thousand years, sacrificing their blood for the continent. By doing so, they not only preserved the European heartland and thus Western civilisation itself, but quite possibly the world in general from unchallenged Islamic dominance. The stakes involved now are no less than they were then, possibly even greater.Footnote140

The constructed urgency to act in defence of an imperilled in-group exploits narratives of the gendered crisis, of women and men losing their femininity, of sexual predation by the out-group, memories of past strength and golden days, victories over enemies, and more. But without an idealised traditional gender order – without the commitment of both ideologically conforming men and women to the reinstituted traditional order – the impact on racial futures is seen to be cataclysmic.

Conclusion

This study analysed how and why gender is used in ideological narratives of Salafi-jihadist and extreme right propaganda by applying discourse analysis to four case studies: AQAP’s Inspire, IS’s Dabiq, Mason’s Siege, and Breivik’s 2083. It argues that gender is used to increase the appeal and resonance of each ideological milieu’s systems of meaning by leveraging five distinct yet interrelated gendered narratives: constructions of a corrupt gender order linked to crisis; constructions of a historically traditional gender order reinstituted by the in-group; portrayals of “good” men and women contributing to solutions and “bad” men and women warranting punishment; constructions of local gendered crises that justify violent action from the in-group; and the juxtaposition of masculinities and femininities to shame or empower audiences into action. Importantly, our qualitative analysis demonstrates how the use and manipulation of gender narratives shifts, depending on the overarching politico-military objectives of the movement. In the case of Salafi-jihadists, while Inspire constructs a gender order that motivates men to wage individual jihad globally by portraying victimised women as the motivator for action, Dabiq’s gender order portrays a diverse range of positive and empowering portrayals of in-group female and male representations who are portrayed as integral to maintaining the Caliphate. Siege and 2083 construct its system of meaning as ideologically and ethnically compatible “white” people bearing solutions to crisis inflicted by the out-group. As a result, constructions of a corrupt gender order revolve around sexually deviant women who undermine the traditional gender and conjugal ideal of the nuclear family with male heroes leading demure, well-behaved, and willing white women. Analysing how these gendered narrative constructs are leveraged in correlation with strategic objectives offers unique insights into how each ideological milieu wants its audiences to view the world, how to behave, and how to view gender and power relations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Haroro J. Ingram, “An Analysis of Islamic State’s Dabiq Magazine,” Australian Journal of Political Science 51, no. 3 (2016): 458–77; J. M. Berger, Extremism (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018); Joe Whittaker and Lilah Elsayed, “Linkages as Lens: An Exploration of Strategic Communications in P/CVE,” Journal for Deradicalisation 20 (2019); Alistair Reed and Jennifer Dowling, “The Role of Historical Narratives in Extremist Propaganda,” Defence Strategic Communications 4 (2018): 79–104.

2 Kiriloi M. Ingram, “An Analysis of Islamic State’s Gendered Propaganda Targeted Towards Women: From Territorial Control to Insurgency,” Terrorism and Political Violence (2021): https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2021.1919637.

3 This study is influenced by conceptual understandings of identity as being both partly individual or personal, and partly collective. For more on the concept of identity being concomitantly individual and collective, see Anthony Giddens and Philip Sutton, Sociology: 7th Edition (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013), 307; David Snow and Doug McAdam, “Identity Work Processes in the Context of Social Movements: Clarifying the Identity/Movement Nexus,” in Self, Identity, and Social Movements, ed. Sheldon Stryker, Timothy Owens and Robert White (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 41–67; Shelby Longard, “The Reflexivity of Individual and Group Identity within Identity-Based Movements: A Case Study,” Human and Society 37, no. 1 (2013): 55–79; Francesca Polletta and James Jasper, “Collective Identity and Social Movements,” Annual Review of Sociology 27 (2001): 283–305.

4 Europol, Women in Islamic State Propaganda: Roles and Incentives, 2020, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/48f7b117-367f-11ea-ba6e-01aa75ed71a1/language-en; Nelly Lahoud, “Empowerment or Subjugation: An Analysis of ISIL’s Gendered Messaging,” UN Women, June 2018, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Lahoud-Fin-Web-rev.pdf; Louisa Tarras-Wahlberg, “Promises of Paradise: IS Propaganda towards Women,” International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, The Hague, December 2016, https://icct.nl/publication/promises-of-paradise-is-propaganda-towards-women/; Julia Musial, “‘My Muslim sister, indeed you are a mujahidah’ – Narratives in the propaganda of the Islamic State to address and radicalise Western women. An Exemplary analysis of the online magazine Dabiq,” Journal for Deradicalisation no. 9 (2016): 39–100; Haras Rafiq and Nikita Malik, “Caliphettes: Women and the Appeal of Islamic State” Quilliam Foundation, 2015; Charlie Winter, “Women of the Islamic State: A Manifesto by the Al-Khannsaa Brigade” Quilliam Foundation, 2015.

5 Dallin Van Leuven, Dyan Mazurana and Rachel Gordon, “Analysing the Recruitment and Use of Foreign Men and Women in ISIL through a Gender Perspective,” in Foreign Fighters under International Law and Beyond, ed. Andrea de Guttry, Francesca Capone and Christophe Paulussen (The Hague: T.M.C Asser Press, 2016), 97–118.

6 Nelly Lahoud, “The Neglected Sex: The Jihadi’s Exclusion of Women From Jihad,” Terrorism and Political Violence 26, no. 5 (2014): 780–802; Nelly Lahoud, “Can Women be Soldiers of the Islamic State,” Survival 59, no. 1 (2017): 61–78; Susanne Schroter, The young wild ones of the Ummah. Heroic gender constructs in Jihadism, (Frankfurter Forschungszentrum Globaler Islam, 2015), https://www.academia.edu/20246399/Heroic_gender_constructs_in_jihadism; Charlie Winter and Devorah Margolin, “The Mujahidat Dilemma: Female Combatants and the Islamic State,” CTC Sentinel 10, no. 7 (2017): 23–8.

7 Agius, Christine, Alexandra Edney-Browne, Lucy Nicholas, and Kay Cook. “Anti-Feminism, Gender and the Far-Right Gap in C/PVE Measures.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 15, no. 3 (2022/07/03 2022): 681–705; Blee, Kathleen M. “Does Gender Matter in the United States Far-Right?” Politics, Religion & Ideology 13, no. 2 (2012): 253–65; Gidengil, Elisabeth, Matthew Hennigar, Andre Blais, and Neil Nevitte. “Explaining the Gender Gap in Support for the New Right: The Case of Canada.” Comparative Political Studies 38, no. 10 (2005).

8 Such as Asal, Victor, Nazli Avdan, and Nourah Shuaibi. “Women Too: Explaining Gender Ideologies of Ethnopolitical Organizations.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (2020): 1–18; Blee, Kathleen M. “Women and Organized Racial Terrorism in the United States.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 28, no. 5 (2005): 421–33; Blee, Kathleen M. Inside Organized Racism Women in the Hate Movement. Acls Humanities E-Book. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002; Campion, Kristy. “Women in the Extreme and Radical Right: Forms of Participation and Their Implications.” Special Issue: Global Rise of the Extreme Right. Social Sciences 9, no. 149 (2020); Durham, Martin. “Securing the Future of Our Race: Women in the Culture of the Modern day BNP.” In Cultures of the Post-War British Fascism, edited by Nigel Copsey and John E. Richardson. Routledge Studies in Fascism and the Far Right. New York: Routledge, 2015; Fangen, Katrine. “Living out Our Ethnic Instincts: Ideological Beliefs among Right-Wing Activists in Norway.” In Nation and Race: The Developing Euro-American Racist Subculture, edited by Jeffrey Kaplan and Tore Bjørgo. Boston: North Eastern University Press, 1998; Gottlieb, Julie V. “Women and British Fascism Revisited: Gender, the Far-Right, and Resistance.” Journal of Women’s History 16, no. 3 (2004): 108–23; McRae, Elizabeth Gillespie. Mothers of Massive Resistance: White Women and the Politics of White Supremacy. Oxford Scholarship Online: Oxford University Press, 2018.

9 Mattheis, Ashley. “Shieldmaidens of Whiteness: (Alt) Maternalism and Women Recruiting for the Far/Alt-Right.” Journal for Deradicalization Winter, no. 17 (2018): 128–62.

10 Sayan-Cengiz, Feyda, and Caner Tekin. “Gender, Islam and Nativism in Populist Radical-Right Posters: Visualizing ‘Insiders’ and ‘Outsiders’.” Patterns of Prejudice 56, no. 1 (2022): 61–93. Also see Heinemann, Isabel, and Alexandra Minna Stern. “Gender and Far-Right Nationalism: Historical and International Dimensions. Introduction.” Journal of Modern European History 20, no. 3 (2022): 311–21 for memes and discourses.

11 Mills, Colleen E., Margaret Schmuhl, Joel A. Capellan, and Jason R. Silva. “Hate as Backlash: A County-Level Analysis of White Supremacist Mobilization in Response to Racial and Gender “Threats”.” Social problems (Berkeley, Calif.) (2023).

12 Haroro Ingram, “The Strategic Logic of the ‘Linkage-Based’ Approach to Combating Militant Islamist Propaganda,” The Hague: International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (2015). https://icct.nl/app/uploads/2017/04/ICCT-Ingram-The-Strategic-Logic-of-the-Linkage-Based-Approach.pdf; Ingram, “An Analysis of Islamic State’s Dabiq Magazine”; J.M. Berger, “Countering Islamic State Messaging through ‘Linkage-Based’ Analysis,” The Hague: The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (2017). https://icct.nl/publication/countering-islamic-state-messaging-through-linkage-based-analysis/; Berger, Extremism; Haroro Ingram, Craig Whiteside and Charlie Winter, ISIS Reader, New York: Oxford University Press, 2020; Reed and Dowling, “The Role of Historical Narratives in Extremist Propaganda”; Whittaker and Elsayed, “Linkages as Lens”; S Zeiger et al., The ISIS Files: Planting the Seeds of the Poisonous Tree: Establishing a System of Meaning Through ISIS Education, Program On Extremism (2021), https://isisfiles.gwu.edu/concern/reports/j3860694x?locale=en.

13 Whittaker and Elsayed, “Linkages as Lens.”

14 While it is beyond the scope of this paper to conduct a review of propaganda literature, a comprehensive overview is available in Garth Jowett and Victoria O’Donnell, Propaganda and Persuasion (California: Sage Publications, 2006). Also see Jacques Ellul, Propaganda: the formation of men’s attitudes, (New York: Random House Vintage Books, 1965); Anthony Pratkanis and Elliot Aronson, Age of Propaganda: The Everyday Use and Abuse of Persuasion (Henry Holt and Company, 2011), 11, cited in Jowett and O’Donnell, Propaganda and Persuasion, 5; Philip M. Taylor, Munitions of the Mind: A History of Propaganda from the Ancient World to the Present Day (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003).

15 Andrew Heywood. Political Ideologies, 4th ed. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007); J. Wilson, Introduction to Social Movements. (Perseus Books Group, 1973); Robert Benford and David Snow, “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26, no. 6 (2000): 11–39; M. Dugas and A.W. Kruglanski, “The Quest for Significance Model of Radicalisation: Implications for the Management of Terrorist Detainees.” Behavioral Sciences & The Law, 32 (2014), p. 427; Berger, Extremism; Marhta Crenshaw, “Decisions to Use Terrorism.” In J. Horgan and K. Braddock (Eds.), Terrorism Studies: A Reader. (Routledge New York, 2012).; Ingram, “An Analysis of Islamic State’s Dabiq magazine.”

16 Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” Theatre Journal 40, no. 4 (1988): 519–31; R.W. Connell, Gender (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2002), 17; Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (London: Routledge, 1990); Laura Sjoberg and Caron E. Gentry, Women, Gender and Terrorism (Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

17 Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution,” 519–31; Daniel G. Renfrow and Judith A. Howard, “Social Psychology of Gender and Race,” in Handbook of Social Psychology, ed. J. DeLamater and A. Ward (London: Springer, 2003); Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (New York: Vintage Books 1973); Connell, Gender; Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution.” For more on individual and collective identity, see Giddens and Sutton, Sociology, 207; Snow and McAdam, “Identity Work Processes in the Context of Social Movements,” 41–67.

18 Haroro J. Ingram, “An Analysis of Inspire and Dabiq: Lessons from AQAP and Islamic State’s Propaganda War,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 40, 5 (2017): 357–75.

19 B. Fall, “The Theory and Practice of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency.” Naval War College, vol. 18, no. 3 (1965): https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/c1cb/1f5a6a19e8a049022bb4a070c63f1ca653b9.pdf; D. Kilcullen, Out of the Mountains – The Coming Age of the Urban Guerrilla. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013; D. Kilcullen, “Blood Year: Terror and the Islamic State.” Quarterly Essay, no. 58 (2015): 1–98.

20 For more, see William Sumner, Folkways: A Study of the sociological importance of usages, manners, customs, mores, and morals, (New York: Mentor, 1906), 12; Marilyn B. Brewer, “In-group bias in the minimal intergroup situation,” 307; Andrew Silke, “Retaliating Against Terrorism,” In Terrorists, Victims and Society: Psychological Perspectives on Terrorism and its Consequences, ed. Andrew Silke (West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2003), 228; Andrew Silke, “Holy Warriors: Exploring the Psychological Processes of Jihadi Radicalisation,” European Journal of Criminology 5, no. 1 (2008): 99–123.

21 Ingram, “An Analysis of Inspire and Dabiq,” 359.

22 Ibid.

23 Michael Hogg, “Uncertainty Identity Theory,” in The Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology: Volume II, ed. Paul A.M. Van Lange, Arie W. Kruglanski, and E Tory Higgins (ProQuest Ebook Central, 2011) 65. See also Michael Hogg, “From Uncertainty to Extremism: Social Categorisation and Identity Processes,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 25, no. 5 (2014): 338–42.

24 Silke, “Holy Warriors,” 99–123; Silke, “Retaliating Against Terrorism”; Hogg, “Uncertainty Identity Theory,”; Hogg, “From Uncertainty to Extremism.”.

25 Ingram, “An Analysis of Islamic State’s Dabiq magazine.”

26 Ingram, “An Analysis of Inspire and Dabiq,” 360; Ingram, “An Analysis of Dabiq,” 463.

27 Hogg, “Uncertainty Identity Theory,” 65.

28 Anthony Giddens, Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age (Cambridge: Polity, 1991); Alexandria Innes, “Everyday Ontological Security: Emotion and Migration in British Soaps,” International Political Sociology 11, no. 4 (2017): 380–97; Catarina Kinnvall, “Globalisation and Religious Nationalism: Self, Identity and the Search for Ontological Security,” Political Psychology 25, no. 5 (2004): 741–67; Jennifer Mitzen, “Ontological Security in World Politics: State Identity and the Security Dilemma,” European Journal of International Relations 12, no. 3 (2006): 344; Catarina Kinnvall and Jennifer Mitzen, “Anxiety, fear, and ontological security in world politics: thinking with and beyond Giddens,” International Theory 12, no. 2 (2020): 240–56.

29 See Sumner, Folkways, 12; Brewer, “In-group bias in the minimal intergroup situation,” 307; Andrew Silke, “Retaliating Against Terrorism,” 228; Marilynn Brewer, “The Psychology of Prejudice: Ingroup Love and Outgroup Hate,” Journal of Social Issues 55, no. 3 (1999): 433.

30 Berger, Extremism; Isaac Kafir, “Social Identity Group and Human (In)security: The Case of Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL),” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 20, no. 1 (2014); Leonard Robinson, “The Islamic State’s Use of Strategic “Framing” to Recruit and Motivate,” Orbis 61, no. 2 (2017): 172–86; Martha Crenshaw, “The Logic of Terrorism,” in Origins of Terrorism, ed. W. Reich (Washington: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1998).

31 Hogg, “Uncertainty Identity Theory”; Hogg, “From Uncertainty to Extremism,” 338–342.

32 This figure was devised drawing on Ingram’s cyclical cognitive reinforcement dynamic diagram in Ingram, “An Analysis of Inspire and Dabiq,” 361, and Ingram’s Macro-, Meso-, and Micro- Propaganda Strategy Diagram in The Islamic State’s Gendered Propaganda: Mobilising Women and Men from Territorial Control to Insurgency, thesis submitted to the University of Queensland, 2022, 79.

33 For more on conjugal order, see Nicole George, “Policing ‘conjugal order’: gender, hybridity and vernacular security in Fiji,” International Feminist Journal of Politics 19, no. 1 (2017): 55–70; Megan Mackenzie, “Securitizing Sex? Towards a Theory of the Utility of Wartime Sexual Violence,” International Feminist Journal of Politics 12, no. 2 (2010): 202–21; Megan Mackenzie, Female Soldiers in Sierra Leone: Sex, Security and Post-Conflict Development, New York, New York University Press: 2012.

34 Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution,” 528.

35 George, “Policing ‘conjugal order’,” 57.

36 Giddens and Sutton, Sociology, 307; Snow and McAdam, “Identity Work Processes in the Context of Social Movements,” 41–67; Longard, “The Reflexivity of Individual and Group Identity within Identity-Based Movements,” 55–79; Polletta and Jasper, “Collective Identity and Social Movements,” 283–305.

37 Kiriloi M. Ingram, The Islamic State’s Gendered Propaganda: Mobilising Women and Men from Territorial Control to Insurgency, thesis submitted to the University of Queensland, 2022; Ingram, “An Analysis of Islamic State’s Gendered Propaganda.”

38 Ibid.

39 Kinnvall, “Globalisation and Religious Nationalism,” 746.

40 Ibid.

41 Chun Wing Lee, “Collective Identity, Individual Identity and Social Movements: The Right-of-Abode Seekers in Hong Kong,” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 17, no. 1 (2008): 33–60; Ingram, “An Analysis of Islamic State’s Gendered Propaganda,” 3.

42 Innes, “Everyday Ontological Security,” 2; Kinnvall, “Globalisation and Religious Nationalism,” 741–67; Judith Butler, Giving an Account of Oneself (New York: Fordham University Press, 2005).

43 While it is beyond the scope of this paper to detail the connection between security attainment and identity, this paper views security as a process rather than an object to be gained. Akin to identity and gender, security can be identified as it is sought, and thus performed. Feeling secure is thus constituted in the performance of “security-seeking actions” by humans in everyday life, with self-categorisation to a collective group being a central means by which to control insecurity. For more, see Alexandria Innes, “In Search of Security: Migrant Agency, Narrative, and Performativity,” Geopolitics 21, no. 2 (2016): 263–83; Laura Shepherd, Gender, Violence and Security: Discourse as Practice (London: Zed Books, 2008); Mitzen, “Ontological Security in World Politics”; Kinnvall, “Globalisation and Religious Nationalism”; For more on the connection between security, collective identity, and gender identity through the gender representations, see Kiriloi M. Ingram, The Islamic State’s Gendered Propaganda: Mobilising Women and Men from Territorial Control to Insurgency, thesis submitted to the University of Queensland, 2022, 140–42.

44 Ingram, The Islamic State’s Gendered Propaganda, 2022; Ingram, “An Analysis of Islamic State’s Gendered Propaganda.”

45 Ingram conceptualises this as “micro-crises” in The Islamic State’s Gendered Propaganda, 124.

46 Ingram, “An Analysis of Islamic State’s Gendered Propaganda,” 2.

47 The Editor, “Letter from the Editor,” Inspire Issue 1 (2010), p. 2.

48 James Mason. Siege (2 ed.). (2015). Ironmarch.org.

49 Anders Behring Breivik. “2083: A European Declaration of Independence.” 2011.

50 It is important to note that this paper makes no assumption that the propaganda is effective in shaping perceptions and behaviours. However, it works from the premise that the objective of propaganda is to shape perceptions and behaviours of a target audience in a way that benefits the source of communication (the propagandist).

51 Abu Mus’ab al-Suri, “The Open Fronts & the Individual Initiative,” Inspire 2, October 2010, p. 20.

52 Alastair Reed and Haroro Ingram, “Exploring the Role of Instructional Material in AQAP’s Inspire and ISIS’s Rumiyah,” EUROPOL, 2017, 4–5, https://nsc.crawford.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publication/nsc_crawford_anu_edu_au/2017-06/reeda_ingramh_instructionalmaterial.pdf; Also see E.F. Kohlmann, “Homegrown Terrorists,” Theory and Cases in the War on Terror’s Newest Fronts,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political Science 618, no. 1 (2008): 98; Marc Sageman, 2008, Leaderless Jihad: Terror Networks in the Twenty-First Century, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; Marc Sageman, “The Next Generation of Terror,” in Foreign Policy, 8 October 2009, http://foreignpolicy.com/2009/10/08/the-next-generation-of-terror/.

53 Abu Mus’ab al-Suri, “The Open Fronts & the Individual Initiative,” Inspire 2, October 2010, 21.

54 Devorah Margolin and Chelsea Daymon, “Women in Violent Extremism: An Analysis of Far-Right and Salafi-Jihadist Movements,” Program on Extremism, 2022, 22. https://extremism.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs5746/files/Women-in-American-Violent-Extremism_Daymon-and-Margolin_June-2022.pdf; Sageman, Leaderless Jihad.

55 Reed and Ingram, “Exploring the Role of Instructional Material,” 5.

56 For example, “Open Source Jihad: Make a bomb in the kitchen of your Mom, How to use Asrar al-Mujahideen,” p. 32.

57 Reed and Ingram, “Exploring the Role of Instructional Material,” 5.

58 Anwar al-Awlaki, “May Our Souls be Sacrificed For You,” Inspire 1, 26; “My Life in Jihad,” Inspire 2, 14; “Interview with Shaykh Abu Sufyan the Vice Amir or Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula,” Inspire 2, 42; Ayman al-Zawahiri, “The Overlooked Backdrop,” Inspire 5, 37; “Inspire Responses Responding to Inquiries,” Inspire 8, 6; Abu Yazeed, “Samir Khan: The Face of Joy,” Inspire 9, 18; Abu Abdillah Almoravid, “France, the Imbecile Invader,” Inspire 10, 16.

59 Interview with Shaykh Abu Sufyan the Vice Amir of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, Inspire 2, 42.