Abstract

Are individuals who obtain their news from online news sources or from social media more likely to fear terrorism? If so, why is this the case? Based on the 2021 Chapman Survey of American Fears, this study draws two key conclusions. First, subjects who more frequently use online and social media news sources exhibit higher levels of fear of terrorism. Second, the relationship between online and social media news reliance and fear of terrorism is mediated through conspiratorial attitudes. These findings are robust to the inclusion of a host of demographic and attitudinal control variables.

Do individuals who more frequently get their news online and through social media fear terrorism more than those who obtain their news from other sources? If so, what might explain the link between online/social media news reliance and fear of terrorism? Finally, what role does conspiratorial thinking play in mediating the relationship between online and social news consumption and fear of terrorism?

Although the actual odds of being a victim of a terrorist attack are extremely low, people’s fear of being a victim of a terrorist attack is consistently high according to recent research.Footnote1 A recent (2021) surveyFootnote2 conducted by Chapman University revealed that around 46.7% of Americans are either “afraid” or “very afraid” of terrorist attacks and around 37.3% fear being the victim of a terrorist attack. In a 2020 survey by Pew,Footnote3 73% of American respondents reported regarding terrorism as a major threat, making terrorism the second greatest concern next to the spread of infectious diseases. Gallup reports that concern about being the victim of terrorism has held constant at around 36 to 51% over the past decade (2011 to 2021).Footnote4

As studied in fear of crime research,Footnote5 individuals have different responses to fear of crime, such as avoiding public places, increasing protective behaviors, minimizing the cost of crime victimization, communicating information and emotions related to crime with others and actively seeking more information about crime in the media and their local environment. Likewise, fear of terrorism causes similar responses among Americans. According to the recent survey about fear of terrorism,Footnote6 24% of Americans stated that they avoided going to public venues such as sport events, concerts, and so on due to fear of terrorism. Moreover, 53% of Americans indicated that they fear traveling abroad because of recent terrorist attacks and 70% said that they would be targeted by terrorists if they travelled outside of the United States.

The burgeoning literature on fear of terrorism provides a preliminary understanding of the role of media in fear of terrorismFootnote7 as well as the underlying social, demographic and individual factors associated with fear of terrorism.Footnote8 Previous research has reported that exposure to media coverage on terrorism increases the individual level of fear of terrorism. When individuals consume terror-related news from either passive media (e.g., newspaper, television or radio) or active media (Google News, Facebook, Twitter, etc.), their fears of terrorism increase.Footnote9 Moreover, earlier studies on fear of terrorism found that women, older adults, politically conservative and more religious people, single individuals, people with low socioeconomic status and less education significantly expressed more fear of terrorism than others.Footnote10

Understanding the link between media consumption and fear of terrorism is critical, given its importance to policymaking and policy responses. Scholars argue that when a major terrorist attack occurs, media (traditional, online and social) plays a significant role in shaping the public’s responses, including fear responses.Footnote11 At times, when various media outlets inform people about a terrorism incident, they (un)intentionally create fear and panic within the society.Footnote12 The discourse of terrorism fear through the media paves the way to the politics of fear, defined as “decision makers’ promotion and use of audience beliefs and assumptions about danger, risk, and fear, to achieve certain goals”.Footnote13 Fear of terrorism is one of the critical factors in defining and shaping the political agenda of governments and largely influences counterterrorism policies and practices. However, an inflated fear of terrorism through various media outlets can lead to the adoption of costly counterterrorism policies and excessive practices.Footnote14

In this study, we examine the effects of different types of news media consumption on individuals’ reported fear of terrorism. We contrast individuals who rely on social and online sources for news with those who rely on other sources, such as national or local print and television media or talk radio and daytime talk shows, to determine whether social and online media users are more likely to exhibit fear of terrorism. We theorize that social media and online news users are more likely to express fear of terrorism. Moreover, we also theorize that an important link between social media and online news consumption and fear of terrorism is conspiratorial thinking, which we argue disproportionately characterizes social media and online news consumers and that reinforces feelings of threat and danger, leading to an increased fear of terrorism. To the best of our knowledge, this research is the first study to incorporate conspiratorial thinking as a mediator between reliance on online and social media news and fear of terrorism. It aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of real-world dynamics and causal relationships among online/social media news and fear of terrorism, rather than merely examining a basic connection between two variables.Footnote15 Understanding the mediating role of conspiratorial thinking can provide practical recommendations for online and social media companies, as well as broader policy implications for governments, to mitigate its effects on fear of terrorism. In the next sections, we briefly review some of the relevant literature, present our theory and hypotheses and discuss our results and findings.

Literature Review

Fear of Terrorism

Numerous definitions of terrorism exist within academic discourse, yet the root of the term lies in the Latin word “terror”, denoting “fear” or “horror”.Footnote16 In an effort to establish a universally accepted understanding of terrorism, Schmid proposes the following definition to capture the fundamental aspects of terrorist actsFootnote17: “Terrorism refers, on the one hand, to a doctrine about the presumed effectiveness of a special form or tactic of fear-generating, coercive political violence and, on the other hand, to a conspiratorial practice of calculated, demonstrative, direct violent action without legal or moral restraints, targeting mainly civilians and non-combatants, performed for its propagandistic and psychological effects on various audiences and conflict parties”. In fact, Kydd and Walter state that terrorist organizations utilize a range of strategies and tactics to achieve their goals and objectives, with intimidation being one of the five fundamental strategies used to instill fear and panic among civilians.Footnote18 Terrorist organizations employ psychological warfare tactics with the goal of perpetuating fear and sustaining elevated levels of anxiety and terror indefinitely.Footnote19 Moreover, Sinclair and Antonius contend that persistent fears of future terrorist attacks significantly affect various aspects of individuals’ lives. These fears influence decisions concerning residence, employment, voting preferences, social interactions and future plans.Footnote20

The vulnerability theory states that fear depends on three interactive factorsFootnote21: exposure to risk, loss of control and the expectancy of serious consequences. According to the assumptions of the vulnerability theory, when people perceive the severity of the consequences of terrorist attacks and sense their inability to control the situation, they feel vulnerable to terrorist incidents and their consequences.Footnote22 Physical, social and situational factors come into play when assessing an individual’s vulnerability to a terrorist attack. If an individual feels physically powerful enough to protect themselves from a terrorist attack, or if they have social resources to prevent or respond to these attacks, or if the presence of a capable guardian who can protect them is evident, these factors will influence their fear of terrorism.Footnote23

Previous studies examined the effects of social, demographic and individual factors on fear of terrorism. First, women consistently expressed higher levels of fear of terrorism compared to men in earlier studies.Footnote24 For instance, Boscarino and colleagues surveyed New Yorkers after one year of the 11 September 2001 (9/11) terrorist attacks and they found that women were more fearful of future terrorist attacks.Footnote25 Similarly, Brück and Müller analyzed the nationally representative survey data collected in Germany and found that women reported more concerns about terrorism.Footnote26 Finally, Onat and colleagues compared Americans’ fear of terrorism and fear of violent crimes using nationally representative data and reaffirmed that women expressed more fear of violent crimes and fear of terrorism compared to men.Footnote27

Second, previous studies indicated that older people are more fearful of terrorism than younger individuals.Footnote28 For example, Boscarino et al. found that older people were more fearful of terrorism.Footnote29 Moreover, Oksanen and colleagues studied the effect of cyberhate exposure on societal fear after the November 2015 Paris terror attacks and found that older individuals reported higher perceived societal fear than younger people in France, Finland and the United States.Footnote30 Last, May et al. examined a statewide victimization survey in Kentucky and their analysis suggested that older respondents were more fearful of terrorism than their counterparts in other age groups.Footnote31

Third, earlier studies also reported that single individuals, people with low socioeconomic status and less education significantly had higher terrorism fear than their counterparts.Footnote32 Drakos and Mueller found that individuals with white-collar jobs less likely reported terrorism as one of the most pressing concerns in their country in Europe.Footnote33 Similarly, Onat and colleagues found that individuals who were not married and had a low level of education expressed higher levels of fear of terrorism.Footnote34 Finally, Krause et al. found that the more people become knowledgeable about terrorism, the less they perceive the threat to themselves and to the United States.Footnote35

Previous research also studied the roles of political viewpoints, religiosity and race in fear of terrorism to understand how social identities shape individuals’ interpretation of national security and terrorism, as well as their responses to these threats and uncertainties.Footnote36 For example, Reinhart states that conservative individuals consistently express greater levels of concern about terrorism in national opinion polls compared to liberals.Footnote37 Moreover, Snook et al. realized that Americans’ perception of the risk of terrorism differentiates based on their political preferences.Footnote38 While conservative individuals see Islamist terrorism as a greater risk than liberals, liberal individuals perceive right-wing extremism as a greater risk to U.S. national security. In addition, Williamson and colleagues found that more politically conservative people express a greater fear of terrorism.Footnote39 Last, in a recent study, Guler and colleagues found that conservative individuals demonstrate increased levels of terrorism-related fear, in line with previous studies highlighting the influence of political ideologies on shaping individuals’ attitudes and actions concerning terrorism and terrorist attacks.Footnote40

The majority of the earlier research on the relationship between the level of religiosity and fear of terrorism found a positive relationship, meaning that more religious people express increased fear of terrorism.Footnote41 For example, Dillon and colleagues found that individuals who found religion important in their life were more likely to worry about terrorism in a cross-national survey.Footnote42 Moreover, Haner et al. reported that highly religious Christians expressed more concern about terrorism and reported more fear or worry about a terrorist attack in a national survey administered in the United States.Footnote43 However, Onat and colleagues found that individuals who attend religious services more frequently have less fear of terrorism, based on a national representative survey conducted in the United States.Footnote44 Previous studies on the relationship between race and fear of terrorism have not yielded conclusive findings. While some studies found that minorities experience more fear of terrorism,Footnote45 other researchers noted that racial status was not a statistically significant predictor in their studies.Footnote46

The Role of the Media in Fear of Terrorism

The media plays a critical role in reporting terrorism incidents and informing people about terrorist threats and activities. In fact, there is a contentious relationship between media and terrorism. Terrorist organizations aim to exploit various means of communication to disseminate their messages as much as possible, propagating their ideologies and agendas among the targeted society.Footnote47 They utilize different media outlets to spread their propaganda to the widest possible audiences. When a terrorist attack occurs, media companies compete to broadcast every possible detail about the incident first to their viewers, aiming to maintain their ratings and increase viewership. However, the extensive media coverage of a terrorist attack facilitates the spread of terrorist propaganda throughout the societies and promotes fear and worries about terrorism among citizens.Footnote48

The cultivation theory asserts that the media has the ability to cultivate its own reality and may create a distorted worldview of reality. The exaggerated display of violence and extreme incidents also triggers fear and sense of danger as a prime residue among their audiences.Footnote49 Previous research has noted that extensive exposure to news about terrorism and terrorist attacks increases fear of terrorism and leads to a disproportionate fear of terrorism.Footnote50 However, individual characteristics and previous life experiences play important roles in interpreting media coverage about terrorism.Footnote51

Prior research on fear of terrorism and the media also has examined the influence of different media types on fear of terrorism.Footnote52 First, Cho and colleagues studied the differences in emotional and cognitive responses of people to 9/11 terrorist attacks between television and print news reports. Their findings indicated that television news coverage was more emotional than newspaper reports, and respondents who relied on television news experienced more positive and negative emotions toward the 9/11 terrorist attacks.Footnote53 Moreover, Williamson and associates analyzed the impact of active media (Internet, newspaper and government leaflets) and passive media (television and radio) sources on fear of terrorism.Footnote54 Their study found that respondents who actively accessed media were more fearful of terrorism than passive consumers. The increasing opportunities to access different kinds of media outlets have provided greater choices and freedom for consumers to select, filter and interact with terrorism news outlets. In addition, Oksanen et al. found that exposure to online hateful communication after terrorist incidents increased societal fear and extensive social media use heightened fear of terrorism.Footnote55 Finally, Onat and colleagues examined the influences of online and social media news on fear of terrorism, and their results indicated that only exposure to social media news had a significant impact on fear of terrorism.Footnote56

Conspiratorial Thinking

The word conspiracy is derived from the Latin conspirare, meaning “to breath together”,Footnote57 and it refers to the proposal to join a secret agreement to commit unlawful or wrongful acts.Footnote58 Conspiracy theorists assert that the truth about major social, political or historical incidents is deliberately being hidden from the public to cover up the genuine intentions and plots of powerful conspirators. According to the British Encyclopedia, conspiracy theories attempt to explain harmful or tragic events as a result of the actions or plots of a small powerful group while rejecting the official narratives and commonly accepted explanations about those events.Footnote59 In fact, the global opinion polls demonstrate that a considerable proportion of people around the world believe in various conspiracy theories and readily reject the official versions of the narratives about significant events while seeking answers from alternative narratives.Footnote60 As an example, the results of a global opinion poll conducted by World Public Opinion.org in 17 countries (2008) found that there was no international consensus about who was behind the 9/11 attacks. Majorities in only nine of the countries believed that Al Qaeda was the behind the attacks, while 15% blamed the U.S. government for the incident. Similarly, based on a survey conducted in the United States in 2007, while 64% of respondents indicated that they believed the official narratives about the 9/11 attacks, 26% said the U.S. government knew about the attacks but consciously let them happen and 5% of respondents claimed that certain elements in the U.S. government actively planned or assisted in making the attacks happen.Footnote61

According to Bader et al., all conspiracy theories share one grand similarity—assuming the existence of extremely powerful others.Footnote62 The conspiratorial mindset embraces a complex mixture of fear, supernatural power and paranormalism to respond to uncertainty, ambiguity and chaos in their minds. Byford points out that the principal medium for the dissemination of conspiracy theories is the Internet, which facilitates the spreading of conspiracies like wildfires through online chats, forums, video-sharing websites and social media outlets.Footnote63

In fact, the online environment provides an echo chamber for individuals who tend to hear the same perspectives and opinions, reinforcing their existing worldviews and ideologies. Cinelli and colleagues studied the role of social media platforms on the formation of echo chambers and their research found that social media users tend to prefer information that aligns with their worldviews, disregard opposing information and connect with polarized groups around shared narratives.Footnote64 Moreover, a recent study on the online diffusion of true and false news discovered that false news spreads more than true news due to its novelty.Footnote65 According to the results of a study on user responses to news narratives on Facebook, polarized users of conspiracy news were more focused on posts from their community, and their attention was more oriented toward disseminating conspiracy content.Footnote66 On the other hand, polarized users of scientific news were less committed to diffusion and more likely to comment on conspiracy pages. However, recent studies indicate that online conspiracy theories, “infodemics” and echo chambers may not be as prevalent as often assumed, and the online environment may serve to reinforce existing viewpoints rather than convince individuals to adopt new ones.Footnote67 Consuming and processing online/social media news has a critical role in constructing the fear of terrorism, but misinformation, disinformation and conspiratorial narratives about terrorism and terrorist activities enhance political polarization, social tension and fear within society.Footnote68

Theory and Research Hypotheses

In this study, we propose a positive relationship between reliance on social media and online websites to obtain news and fear of terrorism. We also propose that the impact of social media/online news reliance and fear of terrorism is mediated through increased conspiratorial attitudes. That is, individuals who rely on social media and online sites for news are more likely to subscribe to an array of conspiracy theories and to exhibit conspiratorial thinking patterns and this helps to explain why they are more afraid of terrorism. A set of literatures guides our argument.

First, a robust body of studies have found that individuals who more frequently use social media and online sites to obtain information are more likely to fear terrorism.Footnote69 Bader et al. document the link between forms of media consumption, particularly social media consumption, and increased perception of threats and fear of adverse occurrences like terrorism.Footnote70 Empirical research by Onat et al. finds a statistical link between social media usage and fear of both terrorism and violent crime in the United States; exposure to online media news predicts fear of terrorism in their study but not fear of violent crimes.Footnote71 Other empirical studies find a similar link between social media/online news reliance and fear of terrorism, but document important nuances such as differentiated gender effects,Footnote72 neighborhood conditions,Footnote73 and whether or not the individual was also exposed to xenophobic messaging and information online.Footnote74 These studies provide a baseline assumption for us that individuals who more frequently turn to social media or online websites to consume news are more likely to express fear of terrorism. This leads to our first hypothesis:

H1: Individuals who more frequently obtain news from online and social media sources are more likely to exhibit fear of terrorism.

Numerous scholars document that conspiracy theories and conspiratorial disinformation are ubiquitous on the Internet and are popularized through online websites and through social media.Footnote75 The medium fosters and reinforces conspiracies and disinformation for reasons mentioned above: the ease of sharing information, absence of vetting and fact checking, the nurturing of conspiracies in online echo chambers and through filter bubbles.Footnote76 A large number of studies demonstrate that individuals who use social media or rely on online sites for information are more likely to encounter conspiracy theories and are more likely to form conspiracy theory–informed beliefs.Footnote77 Other studies produce similar findings but uncover some important nuances and conditions to the relationship. For example, using two empirical studies, Enders et al. found that individuals who get their news from social media and who more frequently use social media were more likely to express beliefs in conspiracy theories. However, this was conditional on exhibiting a predisposition to believing conspiracy theories a prior.Footnote78

Researchers have also determined that belief in conspiracy theories and conspiratorial thinking patterns are associated with diminished trust, higher levels of paranoia, greater sensitivity to nonimmediate dangers, and increased perception of threat in individuals.Footnote79 Studies conducted in Turkey find correlations between individual threat perception and a greater propensity to express conspiracy theories.Footnote80 Individuals who subscribe to conspiracy theories more frequently exhibit chronic feelings of vulnerability and more readily perceive and ruminate over threats.Footnote81 Franks et al. argue that individuals are attracted to and adopt conspiracy theories as a coping mechanism when faced with often abstract external threats.Footnote82 Conspiracy theories allow individuals who feel threatened to make threats more tangible and direct and to transfer blame for threats to a constructed body of conspirators. Finally, increased threat perception and sensitivity to dangerous crises are associated with social group–based conspiratorial beliefs.Footnote83

Given these literatures, we expect to find conspiratorial thinking to significantly mediate the effect of social media and online news consumption on a particularly poignant manifestation of threat for most Americans given aforementioned polling data: terrorism. Therefore, the second hypothesis we test is:

H2: The effect of online and social media news consumption on fear of terrorism is mediated through increased conspiratorial beliefs and attitudes.

Research Design and Methodology

To test the hypotheses of the study, we use public opinion data from the 2021 (Wave 7) Chapman University American Fears Survey.Footnote84 Our sample includes 1,001 subjects and is broadly representative of the wider American public.Footnote85 For the analysis, we employ two sets of techniques. To test H1, that individuals who more frequently use online sources and social media to obtain news are more likely to be fearful of terrorism, we use an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis. To test H2, that the impact of online and social media usage for news on fear of terrorism is mediated through increased conspiratorial beliefs, we use a Sobel-Goodman test of mediation.Footnote86

Variables

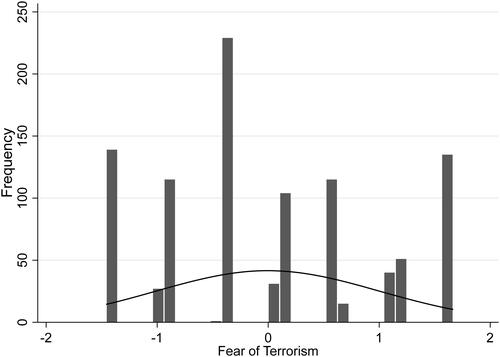

The dependent variable for our study measures subject fear of terrorism and is constructed from two survey questions: “How afraid are you of the following events: A terrorist attack?”Footnote87 and “How afraid are you of being the victim of the following crimes: Terrorism?”Footnote88 Subjects responded to these questions using Likert choices of very afraid, afraid, slightly afraid and not afraid.Footnote89 Fear of terrorism is common in the sample. Around 46.8% of subjects reported being afraid or very afraid of terrorist attacks as events, while around 37.2% of subjects internalized this fear by reporting being afraid or very afraid of being the victim of a terrorist attack. Subject responses to these questions are highly correlatedFootnote90 and factor analysis shows that they load onto a single factor. We therefore used factor analysis to produce a continuous factor dependent variable that ranges from −1.459 to 1.666 to use in our analysis. This makes our dependent variable more compatible with the assumptions of the OLS modeling technique and eases interpretation of results. However, we also ran robustness checks using an unweighted, additive index version of the dependent variable and these reproduce the main results.Footnote91

The frequency distribution of the dependent variable is shown in .

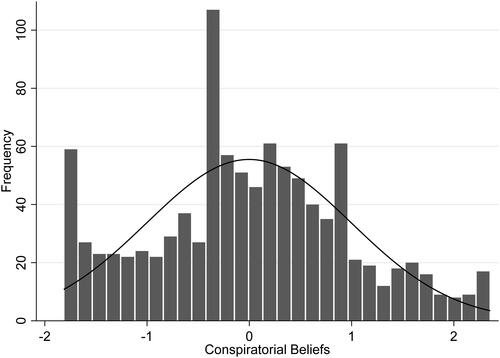

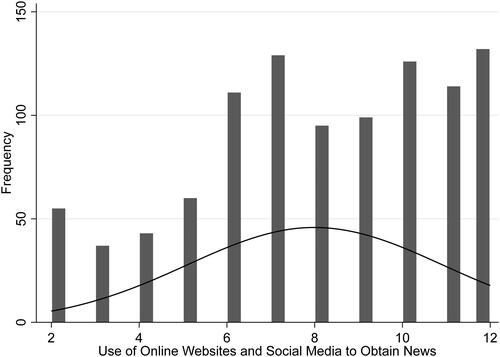

The independent variable of the study measures subjects’ reliance on online and social media for news consumption. It is constructed into an additive index using responses to two correlated questionsFootnote92 about news habits: “How often do you read online news websites?”Footnote93 and “How often do you get your news from social media?”Footnote94 In the sample, around 19.7% of subjects reported reading online news websites every day or most days, while around 26.5% reported getting their news from online sites on a weekly or monthly basis. The majority, around 56.7%, reported that they rarely—less than once a month—or never read online news sites. Reliance on social media for news was a bit more common in the sample. Around 31.2% of subjects reported using social media for news daily or most days, while 21.5% reported relying on social media weekly or monthly. A plurality, 47.61%, stated that they used social media to obtain news less than monthly or never. The additive index constructed by combing responses to these two questions ranges from 2 to 12. When these two sets of responses are combined, use of either online websites or social media to obtain news is relatively frequent in the sample. This is illustrated in , which plots the distribution of the independent variable.

Figure 2. Distribution of independent variable: Use of online websites and social media to obtain news.

In our main analysis, we combine use of social media and use of online websites for news into one variable because both are identified in the literature as increasing users’ belief in conspiracy theories and fear of terrorism in similar ways. However, to make sure that we did not miss potentially unique effects that these two modes might have on the mediator and dependent variable, we split these modes into two independent variables and reran the analysis. The results of these tests are summarized in and (see Appendix), and they closely mirror the findings in our main analysis. Both use of online websites and use of social media to obtain news are significant predictors of fear of terrorism whose effect is mediated through conspiratorial beliefs.

For the mediation analysis, we construct a mediating variable that measures subjects’ proclivity to subscribe to an array of common conspiracy theories using eight questions from the Chapman Survey. These conspiracies include belief that the government is concealing what it knows about alien encounters; airplane crashes and disasters; global warming; the assassination of former president John F. Kennedy; the moon landing; the “Illuminati/New World Order”; mass shooting events such as the Sandy Hook, Las Vegas or Parkland tragedies; and Q’Anon conspiracies.Footnote95 Responses to these questions are correlatedFootnote96 and load onto one factor. We therefore created a continuous factor variable to measure subjects’ (cumulative) conspiratorial attitudes, which ranges between −1.814, indicating a very low proclivity toward conspiratorial thinking, and 2.335, indicating very high, across-the-board conspiratorial thinking. Conspiratorial beliefs are somewhat normally distributed in the sample of respondents, although overall the distribution is leftward skewed, indicating a larger number of respondents who expressed below-median levels of conspiratorial attitudes. This is illustrated in .

The modal subject (sixty-two subjects, approximately 6.2% of the sample) expressed a relatively low level of belief (−0.424 on factor variable scale) that the U.S. government is concealing information from the public about popular conspiracies, while the mean subject also was slightly less likely to evince conspiratorial thinking pattern (−0.003 on factor variable scale).

In the estimations, we control for a host of behavioral, demographic and attitudinal factors that may also affect subjects’ fear of terrorism. First, we control for other media consumption patterns by holding constant the frequency with which subjects reported relying on national newspapers; local newspapers; network television news; local television news; cable news channels, such as CNN, MSNBC and Fox; talk radio; and daytime talk television programs to obtain political news. Of these modes, local television news was the most popular source for news for subjects, with around 46.7% reporting that they watched local television news “most days” or “every day”.Footnote97 The next most popular media were network news (29.5% reported using it daily or almost daily), local newspapers (25.2%) and national newspapers (23.7%). Although cable news is widely viewed as a force that shapes Americans’ political attitudes about current events, fewer subjects reported relying heavily on it. Around 18.6% reported watching CNN, 16.5% reporting watching Fox and 16.4% reported watching MSNBC daily or almost daily. Around 18.1% reported being daily or almost daily listeners to talk radio. Finally, only around 6.2% of subjects reported tuning in to daytime talk television every day or most days for their news.

In the estimations, we also controlled for subject age,Footnote98 gender,Footnote99 education level,Footnote100 household income,Footnote101 employment status,Footnote102 self-reported race or ethnicity,Footnote103 religion,Footnote104 beliefs about the inerrancy and literalism of the Bible,Footnote105 region of the country,Footnote106 partisan affiliation,Footnote107 and political ideology.Footnote108 In the sample, the modal subject was female (50.2%; 48.8% identified as male while 1% either identified as nonbinary or preferred not to self-identify). The median subject was between 30 and 49 years of age, had completed at least a two-year or associate’s degree from a college or university, and had a household annual income of between U.S.$50,000 to 100,000. Around 6.2% of subjects reported that they were unemployed and seeking work. In terms of ethnic breakdown, around 66.6% of subjects identified themselves as White, non-Hispanic, around 9.0% identified as Black, non-Hispanic, while around 15.5% identified as Hispanic or Latino (and not White or Black). Half (50.0%) of the sample identified as being Christian (any denomination) while around 12.8% of subjects stated that they regard the Christian Bible as the literal word of God and inerrant—a measure we use to capture Christian fundamentalism. Approximately 23.9% of subjects lived in the West, 19.4% in the Northeast, 37.1% in the South and 19.5% in the Midwest. Partisan affiliation is relatively evenly split in the sample: around 36.2% of subjects identified themselves as Democrats (strong or leaning), while around 28.3% identified as Republicans (strong or leaning). Around 32.4% of subjects identified as independents. Political ideology is similarly evenly distributed in the sample with around 34.2% of subjects identifying as politically liberal (leaning liberal, liberal or extremely liberal), 33.5% identifying as moderate and 32.2% identifying as politically conservative (leaning conservative, conservative, extremely conservative). We also controlled for the time subjects took to take the survey: the median subject took around 22 minutes to complete the survey. All subjects that refused to provide answers to any survey questions were removed from the sample. Full descriptive statistics of all variables used in the analysis are provided in (see Appendix).

Results

The results of our analyses provide support for both of our hypotheses. Individuals who more heavily rely on online and social media news sources are more likely to be fearful of terrorism. The effect of online and social media reliance for news on fear of terrorism is mediated through increased conspiratorial attitudes, suggesting that heavier use of online and social media usage is associated with a proclivity toward conspiratorial patterns of thought that foster greater fear of terrorism.

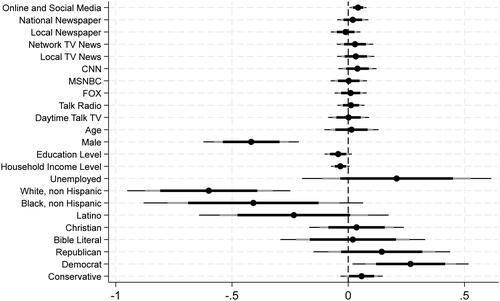

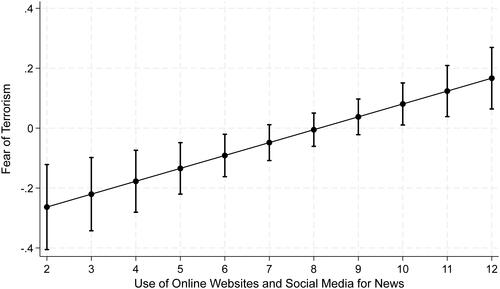

As previously noted, we conducted two types of empirical test. Our first test employs an OLS regression technique to determine the effect of online and social media usage to obtain news on attitudes about terrorism (H1). The main results of this test are summarized in .

Figure 4. Marginal effects of use of online websites and social media to obtain news and fear of terrorism.

Fear of Terrorism. Continuous variable constructed using factor analysis of two survey questions: (1) How afraid are you of the following events: A terrorist attack? Reponses: very afraid, afraid, slightly afraid, not afraid (inverted); (2) How afraid are you of being the victim of the following crimes: terrorism? Responses: very afraid, afraid, slightly afraid, not afraid (inverted).

Use of Online Websites and Social Media for News. Additive index constructed using two survey questions: (1) How often do you read online news websites? Responses: every day, most days, once or twice a week, once or twice a month, less than once a year, never (inverted): (2) How often do you get news from social media?: Responses: every day, most days, once or twice a week, once or twice a month, less than once a year, never (inverted).

Controls: Model includes the following controls: frequency of getting news from national newspaper, local newspaper, network television news, local television news, CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, talk radio, daytime talk television; age; gender; education level; household income level; employment status; race/ethnicity; religion; literal interpretation of Bible; U.S. region of residence; partisan identification; political ideology; duration of survey.

graphs the marginal effects of a one-unit change of the independent variable—frequency of use of online websites or social media to obtain news—on the dependent variable—a factor variable measuring level of expressed fear of terrorism. As evident in , the effect of online and social media usage for news on fear of terrorism is positive and significant (β = .043, 95% CI [.021, .064]) with a p-value of.000. Increasing the independent variable from its minimum to maximum value is associated with a corresponding 63.2% increase in subject reported fear of terrorism.Footnote109 A full summary of the model on which is based is presented in (see Appendix).

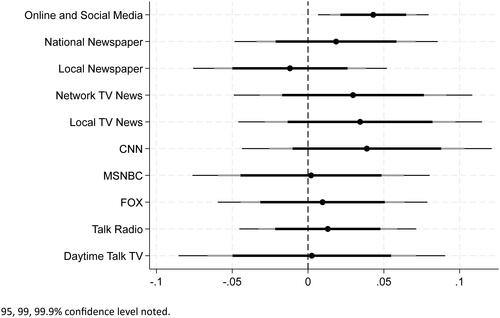

and compare the relationships and substantive impacts that the other variables in the model have on fear of terrorism. presents a coefficient plot of all variables used in the analysis, showing the relative substantive impact of reliance on online and social media news sources on fear of terrorism.

Figure 6. Coefficient plots: Types of news consumption and fear of terrorism 95, 99, 99.9% confidence level noted.

Note. All covariates included in model. Covariates included but not displayed (to conserve space): age; gender; education level; household income level; employment status; race/ethnicity; religion; literal interpretation of Bible; U.S. region of residence; partisan identification; political ideology; duration of survey.

Most of the other variables in the model are not significant predictors of fear of terrorism. This includes the other sources of news modeled in the analysis. Subjects who reported that they relied on national newspapers; local newspapers; network television news; local television news; cable news channels like CNN, MSNBC and Fox; talk radio; or daytime talk television were no more or less likely to express fear of terrorism. presents a close-up of these findings by reporting only news sources as predictors of fear of terrorism (but still including all controls as in the full model).

A handful of other variables are significant in the analysis. Males are significantly less likely to express fear of terrorism (β = −0.418, 95% CI [−0.541, −0.296]) as are more educated subjects (β = −0.042, 95% CI [−0.077, −0.007]), and higher-income subjects (β = −0.034, 95% CI [−0.058, −0.010]), Whites (β = −0.597, 95% CI [−0.790, −0.368]). In contrast, Democrats (β = .266, 95% CI [.118, .415]) and subjects expressing higher levels of political conservatism (β = .058, 95% CI [.003, .112]) are more likely to fear terrorism.

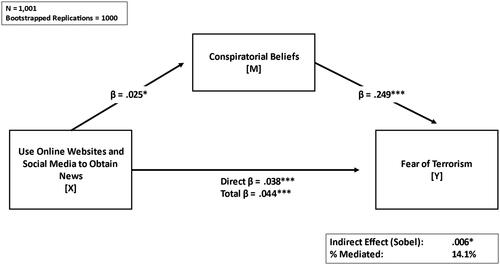

Our second empirical tests use a mediation technique to test the second hypothesis. The results of the mediation analysis are summarized in .

The effect of online website and social media usage to obtain news on fear of terrorism is significantly mediated through an increase in conspiratorial belief patterns. As shown in , subjects who use online sites and social media to follow the news are significantly more likely to hold an array of conspiratorial beliefs (β = .025, 95% CI [.004, .046]), suggesting that they are more receptive to conspiracy theories about the U.S. government. In turn, subjects exhibiting conspiratorial belief patterns—those that subscribe to a wider array of conspiracy theories about the U.S. government–are more likely to fear terrorism (β = .249, 95% CI [.185, .312]). Moreover, the Sobel tests indicates that the effect of online and social media news habits on fear of terrorism are significantly mediated through conspiratorial thinking (Sobel estimation.006, p = .025). The percentage of the effect of online and social media news information reliance on fear of terrorism mediated through conspiratorial beliefs is 14.1%. This indicates that we are capturing some but not all of the mediation effect, suggesting that other unobserved factors are also at play. Future research might address this by evaluating other potential mediators that are not included in the dataset we used for the study. In particular, future studies might examine other individual characteristics of subjects including propensity for paranoia, a quality that likely affects assessment of risk and may mediate the effects of reliance on online websites and social media for news on fear of terrorism.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to understand how regular consumption of news through social and online media influences individuals’ fear of terrorism while considering the potential effect of conspiratorial thinking as a mediating factor between online/social news consumption and the fear of terrorism. The results of our analyses indicated that individuals who more frequently utilize online and social media news sources have higher levels of fear of terrorism and being the victim of a terrorist attack compared to individuals who rely on other news sources. However, this relationship between online/social media consumption and fear of terrorism is mediated by the presence of conspiratorial attitudes. People who rely more on online and social media for news tend to present higher levels of conspiratorial thinking, which in turn increases their likelihood of fearing terrorism and being a victim of a terrorist attack.

The results of this study make significant contributions to the fear of terrorism literature. First, in parallel with the findings of previous research,Footnote110 our study confirms that online/social media news consumption heightens fear of terrorism. Individuals who obtain their news from online or social media sources express more fear of terrorism compared to their counterparts. This finding indicates that Internet as a news source in active media provides a breeding ground for cultivation of an increase in fear of terrorism.Footnote111 However, different from the previous research, our findings suggest that conspiratorial thinking serves as a mediating factor between online/social media news consumption and the fear of terrorism. As far as we know, this is the first study that uncovers the mediating role of conspiratorial thinking in the relationship between the online/social media news and the fear of terrorism.

As suggested by Jackson and Gray, fear of crime could be the result of functional and dysfunctional fear; while functional fear leads to positive aspects of problem solving, crime prevention and taking precaution against potential threat, dysfunctional fear causes quality of life to erode.Footnote112 Conspiratorial thinking and conspiratorial attitudes may cause an inflated fear of terrorism that can be classified as dysfunctional fear. The distrust of the government among Americans and their tendency to subscribe to a wider array of conspiracy theories make them susceptible to readily believing conspiratorial stories and news circulating on online platforms. The Internet provides a suitable communication medium for the spreading of conspiracies, reinforcing fake news and false information about terrorism and offering a convenient platform for misinformation and disinformation about terrorist activities through online forums, social media outlets and other online mediums.Footnote113 This worsens the inflated fear of terrorism among citizens and prompts the adoption of expensive and aggressive counterterrorism measures.

The findings of this research have potential policy implications. First, online and social media news outlets should be more cognizant and mindful while disseminating information about terrorism and terrorist attacks to minimize the risk of excessive fear of terrorism. Even though fact-checking programs utilized by social media platforms are useful and promising in identifying and minimizing online misinformation and disinformation, they should develop more effective strategies and tools to deal with the spread of conspiratorial theories and narratives related to terrorism and terrorist activities. Specifically, social and online media platforms should better utilize artificial intelligence, machine learning and natural language processing tools to enhance the detection and response to conspiracy topics.Footnote114 Detecting and correcting conspiracy-related false, fake and deepfake online/social media news will minimize the spread of conspiracy narratives related to terrorism and terrorist attacks.Footnote115 Moreover, social media platforms should be more open to providing data to researchers studying their roles on the diffusion and amplification of conspiratorial narratives on terrorism.Footnote116 The results of these scientific studies can offer a better understanding for developing efficient interventions to minimize the spread of conspiratorial theories on online platforms and reduce unnecessary fear of terrorism. Second, the U.S. government and governments of other countries should prioritize addressing citizens’ distrust of government and skepticism toward official explanations of terrorist attacks and terrorism. This will help reduce conspiratorial thinking and conspiratorial attitudes when it comes to terrorism news. As suggested by some researchers, providing factual information about the relative risk of terror attacks to the American public can change their perceptions and beliefs about terrorism and reduce fear of terrorism and decrease the demand for excessive counterterrorism policies.Footnote117 The latest research indicates that directly contradicting or mocking conspiracy theories is unlikely to sway believers’ adherence to them. Instead, it is more effective to interact with moderate individuals within conspiracy groups.Footnote118 In fact, a recent systematic review on the efficacy of interventions in reducing belief in conspiracy theories found that interventions that promote analytical thinking or critical skills were notably successful in changing such beliefs.Footnote119 Therefore, governments should increase their support for educational policies, programs and practices that promote the analytical and critical thinking skills of their citizens. This would help them question the credibility of conspiracy theories and shift their attention to information supported by credible evidence and scientific consensus.Footnote120

This research also highlights potential avenues for future academic research on the fear of terrorism. Future qualitative research may delve deeper into how conspiratorial thinking fosters fear of terrorism within online communities, exploring specific types of online/social media news that trigger this type of fear and the roles that conspiratorial mindsets play in shaping this relationship. Moreover, future studies may also explore other mediating or moderating factors that come into play between the fear of terrorism and media consumption (traditional, online and social) to uncover the underlying factors in these relationships.

It’s important to note that this research comes with certain limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of the study prevents us from drawing casual or temporal conclusions. Second, the reliance on self-reported survey data could introduce potential sources of biases. The third limitation pertains to the sample size. Even though the Chapman Survey utilized probability panels and weighting techniques to ensure a nationally representative sample, having a larger sample size would be better for testing relationships at a national scale.

Conclusion

This study investigated whether individuals who rely on online news sources or social media are more prone to fearing terrorism and explored the mediating role of conspiratorial attitudes between online/social media news consumption and fear of terrorism. The findings of the research revealed that those who use online and social media news sources more often also tend to exhibit higher levels of conspiratorial thinking, which in turn increases the likelihood of them fearing terrorism. These findings remained consistent even after accounting for various demographic and attitudinal factors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Roxy Amirazizi, “America’s Top Fears 2020/2021,” The Chapman University, 2022; Jacob Poushter and Moira Fagan, “Americans See Spread of Disease as Top International Threat, along with Terrorism, Nuclear Weapons, Cyberattacks,” 2020.

2 Chapman University Survey of American Fears (2021). Codebook and data available online at chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.chapman.edu/wilkinson/research-centers/babbie-center/_files/Babbie%20center%20fear2021/wave-7-american-fears-methodology-report-v2-06.15.21.pdf (Data accessed 30 May 2023).

3 Pew Research Center, “Americans See Spread of Disease as Top International Threat, along with Terrorism, Nuclear Weapons, Cyberattacks,” 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/04/13/americans-see-spread-of-disease-as-top-international-threat-along-with-terrorism-nuclear-weapons-cyberattacks/.

4 Gallup, “Terrorism,” https://news.gallup.com/poll/4909/terrorism-united-states.aspx.

5 James Garofalo, “The Fear of Crime: Causes and Consequences,” The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (1973-) 72, no. 2 (1981): 839–57. doi: 10.2307/1143018; C. Hale, “Fear of Crime: A Review of the Literature – C. Hale, 1996,” https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/026975809600400201 (accessed 23 October 2023).

6 Christopher D. Bader, Joseph O. Baker, L. Edward Day, and Ann Gordon, Fear Itself: The Causes and Consequences of Fear in America (Oxford University Press, 2020).

7 Leevia Dillon, Brittany E. Hayes, Joshua D. Freilich, and Steven M. Chermak, “Gender Differences in Worry About a Terrorist Attack: A Cross-National Examination of Individual- and National-Level Factors,” Women & Criminal Justice 29, no. 4–5 (September 3, 2019): 221–41. doi: 10.1080/08974454.2018.1528199; Paul D. Driscoll, Michael B. Salwen, and Bruce Garrison, “Public Fear of Terrorism and the News Media,” in Online News and the Public (2005), 165–84; Atte Oksanen, Markus Kaakinen, Jaana Minkkinen, Pekka Räsänen, Bernard Enjolras, and Kari Steen-Johnsen, “Perceived Societal Fear and Cyberhate after the November 2015 Paris Terrorist Attacks,” Terrorism and Political Violence 32, no. 5 (3 July 2020): 1047–66. doi: 10.1080/09546553.2018.1442329; Ismail Onat, “Media, Neighborhood Conditions, and Terrorism Risk: What Triggers Fear of Terrorism?,” Rutgers University – Graduate School – Newark, 2016. doi:10.7282/T3JD5003; Lotte Skøt, Jesper Bo Nielsen, and Anja Leppin, “Risk Perception and Support for Security Measures: Interactive Effects of Media Exposure to Terrorism and Prior Life Stress?,” Journal of Risk Research 24, no. 2 (1 February 2021): 228–46. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2020.1750460; Pamela Wilcox, M. Murat Ozer, Murat Gunbeyi, and Tarkan Gundogdu, “Gender and Fear of Terrorism in Turkey,” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 25, no. 3 (2009): 341–57. doi: 10.1177/1043986209335011; Harley Williamson, Suzanna Fay, and Toby Miles-Johnson, “Fear of Terrorism: Media Exposure and Subjective Fear of Attack,” Global Crime 20, no. 1 (2 January 2019): 1–25. doi: 10.1080/17440572.2019.1569519.

8 Joseph A. Boscarino, Charles R. Figley, and Richard E. Adams, “Fear of Terrorism in New York after the September 11 Terrorist Attacks: Implications for Emergency Mental Health and Preparedness,” International Journal of Emergency Mental Health 5, no. 4 (2003): 199; Tilman Brück and Cathérine Müller, “Comparing the Determinants of Concern about Terrorism and Crime,” Global Crime 11, no. 1 (8 February 2010): 1–15. doi:10.1080/17440570903475634; Joy J. Burnham, “Children’s Fears: A Pre-9/11 and Post-9/11 Comparison Using the American Fear Survey Schedule for Children,” Journal of Counseling & Development 85, no. 4 (2007): 461–66. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00614.x; Konstantinos Drakos and Catherine Mueller, “On the Determinants of Terrorism Risk Concern in Europe,” Defence and Peace Economics 25, no. 3 (4 May 2014): 291–310. doi:10.1080/10242694.2013.763472; M. Salih Elmas, “Perceived Risk of Terrorism, Indirect Victimization, and Individual-Level Determinants of Fear of Terrorism,” Security Journal 34, no. 3 (2021): 498–524. doi: 10.1057/s41284-020-00242-6; Murat Haner, Melissa M. Sloan, Francis T. Cullen, Teresa C. Kulig, and Cheryl Lero Jonson, “Public Concern about Terrorism: Fear, Worry, and Support for Anti-Muslim Policies,” Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 5 (2019): 237802311985682. doi:10.1177/2378023119856825; Fang Hong, Yijing Lin, Mikyung Jang, Amanda Tarullo, Majed Ashy, and Kathleen Malley-Morrison, “Fear of Terrorism and Its Correlates in Young Men and Women from the United States and South Korea,” Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research 12, no. 1 (2020): 21–32; Ismail Onat, Mehmet F. Bastug, Ahmet Guler, and Sedat Kula, “Fears of Cyberterrorism, Terrorism, and Terrorist Attacks: An Empirical Comparison,” Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression (10 March 2022): 1–17. doi:10.1080/19434472.2022.2046625; Ismail Onat, Ahmet Guler, Sedat Kula, and Mehmet F. Bastug, “Fear of Terrorism and Fear of Violent Crimes in the United States: A Comparative Analysis,” Crime & Delinquency 69, no. 5 (2023): 891–914. doi:10.1177/00111287211036130; Mally Shechory Bitton and Yousef Silawi, “Do Jews and Arabs Differ in Their Fear of Terrorism and Crime?,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34, no. 19 (2019): 4041–60. doi: 10.1177/0886260516674198; Mally Shechory-Bitton and Keren Cohen-Louck, “An Israeli Model for Predicting Fear of Terrorism Based on Community and Individual Factors,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 35, no. 9–10 (2020): 1888–907. doi:10.1177/0886260517700621; Jun Shigemura, Carol S. Fullerton, Robert J. Ursano, Leming Wang, Raffaella Querci-Daniore, Naoshi Horikawa, Aihide Yoshino, and Soichiro Nomura, “Gender Differences in the Fear of Terrorism among Japanese Individuals in the Washington, DC Area,” Asian Journal of Psychiatry 3, no. 3 (2010): 117–20.

9 Williamson et al., “Fear of Terrorism,” 4.

10 Boscarino et al., “Fear of Terrorism in New York,” 4. Burnham, “Children’s Fears,” 464; Brück and Müller, “Comparing the Determinants,” 8; Haner et al., “Public Concern about Terrorism,” 11; Hong et al., “Fear of Terrorism and,” 27; David C. May, Joe Herbert, Kelly Cline, and Ashley Nellis, “Predictors of Fear and Risk of Terrorism in a Rural State,” 2011; Shigemura et al., “Gender Differences,” 118; Wilcox et al., “Gender and Fear,” 350.

11 Ashley Marie Nellis, “Gender Differences in Fear of Terrorism,” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 25, no. 3 (2009): 322–40. doi:10.1177/1043986209335012; Ismail Onat, “Media, Neighborhood Conditions, and Terrorism Risk: What Triggers Fear of Terrorism?,” Rutgers University – Graduate School – Newark, 2016. doi: 10.7282/T3JD5003.

12 Jonathan S. Comer and Philip C. Kendall, “Terrorism: The Psychological Impact on Youth,” Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 14, no. 3 (2007): 179.

13 David L. Altheide, “Terrorism and the Politics of Fear,” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 6, no. 4 (2006): 415–39. doi: 10.1177/1532708605285733; Jessica Wolfendale, “Terrorism, Security, and the Threat of Counterterrorism,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 30, no. 1 (2007): 75–92. doi: 10.1080/10576100600791231.

14 Benjamin H. Friedman, “Managing Fear: The Politics of Homeland Security,” Political Science Quarterly 126, no. 1 (2011): 77–106; Brigitte L. Nacos, Yaeli Bloch-Elkon, and Robert Y. Shapiro, “Selling Fear: Counterterrorism, the Media, and Public Opinion,” in Selling Fear (University of Chicago Press, 2011); Daniel Silverman, Daniel Kent, and Christopher Gelpi, “Putting Terror in Its Place: An Experiment on Mitigating Fears of Terrorism among the American Public,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 66, no. 2 (2022): 191–216. doi:10.1177/00220027211036935.

15 Dawn Iacobucci, Mediation Analysis (SAGE, 2008).

16 V. I. Vasilenko, “The Concept and Typology of Terrorism,” Statutes and Decisions 40, no. 5 (2004): 46–56. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10610014.2004.11059722.

17 Alex P. Schmid, “The Revised Academic Consensus Definition of Terrorism,” Perspectives on Terrorism 6, no. 2 (2012).

18 Andrew H. Kydd and Barbara F. Walter, “The Strategies of Terrorism,” International Security 31, no. 1 (1 July 2006): 49–80. doi:10.1162/isec.2006.31.1.49.

19 Bruce Hoffman, “Rethinking Terrorism and Counterterrorism Since 9/11,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 25, no. 5 (1 September 2002): 303–16. doi:10.1080/105761002901223. John G. Horgan, The Psychology of Terrorism (Routledge, 2014).

20 Samuel Justin Sinclair and Daniel Antonius, The Psychology of Terrorism Fears (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

21 M. Killias, “Vulnerability: Towards a Better Understanding of a Key Variable in the Genesis of Fear of Crime,” Violence and Victims 5, no. 2 (1990): 97–108.

22 Wesley G. Skogan, Police and Community in Chicago: A Tale of Three Cities (Oxford University Press, 2009).

23 Theo Lorenc, Mark Petticrew, Margaret Whitehead, David Neary, Stephen Clayton, Kath Wright, Steven Cummins, Amanda Sowden, and Adrian Renton, “Crime Fear of Crime and Mental Health: Synthesis of Theory and Systematic Reviews of Interventions and Qualitative Evidence,” Public Health Research 2, no. 2 (March 2014): 1–398. doi:10.3310/phr02020.

24 Boscarino et al., “Fear of Terrorism in New York,” 4; Burnham, “Children’s Fears,” 464; Brück and Müller, “Comparing the Determinants,” 8; Haner et al., “Public Concern about Terrorism,” 11; Hong et al., “Fear of Terrorism and,” 27; Onat et al., “Fear of Terrorism and Fear,” 906; Shechory-Bitton and Kohen-Louck, “An Israeli Model for,” 4049; Wilcox et al., “Gender and Fear,” 350.

25 Boscarino et al., “Fear of Terrorism in New York,” 4.

26 Brück and Müller, “Comparing the Determinants,” 8.

27 Onat et al., “Fear of Terrorism and Fear,” 906.

28 Boscarino et al., “Fear of Terrorism in New York,” 5; Brück and Müller, “Comparing the Determinants,” 13; May et al., Predictors of Fear,” 14; Oksanen et al., “Perceived Societal Fear,” 1057; Onat et al., “Fear of Terrorism and Fear,” 905.

29 Boscarino et al., “Fear of Terrorism in New York,” 5.

30 Oksanen et al., “Perceived Societal Fear,” 1057.

31 May et al., “Predictors of Fear,” 14.

32 Boscarino et al., “Fear of Terrorism in New York,” 13; Konstantinos Drakos and Catherine Mueller, “On the Determinants of Terrorism Risk Concern in Europe,” Defence and Peace Economics 25, no. 3 (4 May 2014): 291–310. doi:10.1080/10242694.2013.763472; Shechory-Bitton and Kohen-Louck, “An Israeli Model for,” 1897.

33 Drakos and Mueller, “On the Determinants of,” 10.

34 Onat et al., “Fear of Terrorism and Fear,” 903.

35 Krause, Peter, Daniel Gustafson, Jordan Theriault, and Liane Young, “Knowing Is Half the Battle: How Education Decreases the Fear of Terrorism,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 66, no. 7–8 (1 August 2022): 1147–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220027221079648.

36 George A. Bonanno and John T. Jost, “Conservative Shift Among High-Exposure Survivors of the September 11th Terrorist Attacks,” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 28, no. 4 (2006): 311–23. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp2804_4; Stewart J. H. McCann, “Threatening Times, ‘Strong’ Presidential Popular Vote Winners, and the Victory Margin, 1824–1964,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73, no. 1 (July 1997): 160–70. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.160; Drakos and Mueller, 10; Guler, Ahmet, Ismail Onat, and Mehmet F. Bastug, “Deconstructing Fears of Terrorism: A Comparison between Fear from Domestic and International Terrorist Groups,” Terrorism and Political Violence (2024): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2024.2308223. R. J. Reinhart, “Terrorism Fears Drive More in US to Avoid Crowds,” Gallup, 2017; Snook, Daniel W., Ari D. Fodeman, Katharina Meredith, and John G. Horgan, “The Politics of Perception: Political Preference Strongly Associated with Different Perceptions of Islamist and Right-Wing Terrorism Risk,” Terrorism and Political Violence 0, no. 0 (2022): 1–18. doi:10.1080/09546553.2022.2122815; Williamson et al., “Fear of Terrorism,” 12.

37 Reinhart, “Terrorism Fears,” https://news.gallup.com/poll/212654/terrorism-fears-drive-avoid-crowds.aspx.

38 Snook et al., “The Politics of Perception,” 9.

39 Williamson et al., “Fear of Terrorism,” 12.

40 Ahmet Guler, Ismail Onat, and Mehmet F. Bastug, “Deconstructing Fears of Terrorism: A Comparison between Fear from Domestic and International Terrorist Groups,” Terrorism and Political Violence (2024): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2024.2308223.

41 Dillon et al., “Gender Differences in,” 232; Elmas, “Perceived Risk of,” 515; Haner et al., “Public Concern about Terrorism,” 11; Shechory-Bitton and Cohen-Louck, “An Israeli Model for,” 1896; Onat et al., “Fears of Cyberterrorism,” 10.

42 Dillon et al., “Gender Differences in,” 232.

43 Haner et al., “Public Concern about Terrorism,” 11.

44 Onat et al., “Fears of Cyberterrorism,” 10.

45 Boscarino et al., “Fear of Terrorism in New York,” 12; Haner et al., “Public Concern about Terrorism,” 11; Ashley Marie Nellis and Joanne Savage, “Does Watching the News Affect Fear of Terrorism? The Importance of Media Exposure on Terrorism Fear,” Crime & Delinquency 58, no. 5 (1 September 2012): 748–68. doi: 10.1177/0011128712452961; Onat et al., “Fear of Terrorism and Fear,” 906.

46 Elmas, “Perceived Risk of,” 517; May et al., “Predictors of Fear,” 13.

47 Brigitte L. Nacos, “The Terrorist Calculus behind 9-11: A Model for Future Terrorism?,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 26, no. 1 (2003): 1–16. doi:10.1080/10576100390145134; Alex Peter Schmid and Janny de Graaf, Violence as Communication: Insurgent Terrorism and the Western News Media (Sage, 1982).

48 Comer and Kendall, 10.

49 George Gerbner and Larry Gross, “Living with Television: The Violence Profile,” Journal of Communication 26, no. 2 (1976): 172–99.

50 Elmas, “Perceived Risk of,” 515; Nellis, “Gender Differences in,” 331; Onat, “Media, Neighborhood Conditions,” 123.

51 Dillon et al., “Gender Differences in,” 232; Nellis and Savage, “Does Watching,” 760.

52 Jaeho Cho, Michael P. Boyle, Heejo Keum, Mark D. Shevy, Douglas M. McLeod, Dhavan V. Shah, and Zhongdang Pan, “Media, Terrorism, and Emotionality: Emotional Differences in Media Content and Public Reactions to the September 11th Terrorist Attacks,” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 47, no. 3 (2003): 309–27. doi: 10.1207/s15506878jobem4703_1; Marlies Debrael, Leen d’Haenens, Rozane De Cock, and David De Coninck, “Media Use, Fear of Terrorism, and Attitudes towards Immigrants and Refugees: Young People and Adults Compared,” International Communication Gazette 83, no. 2 (2021): 148–68. doi:10.1177/1748048519869476; Oksanen et al., “Perceived Societal Fear,” 1055; Onat et al., “Fear of Terrorism and Fear,” 906; Williamson et al., “Fear of Terrorism,” 12.

53 Cho et al., “Media, Terrorism,” 320.

54 Williamson et al., “Fear of Terrorism,” 12.

55 Oksanen et al., “Perceived Societal Fear,” 1055.

56 Onat et al., “Fear of Terrorism and Fear,” 906.

57 Jovan Byford, “Towards a Definition of Conspiracy Theories,” in Conspiracy Theories (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2011), 20–37. doi: 10.1057/9780230349216_2.

58 Merriam-Webster, “Definition of Conspiracy,” 21 October 2023. https://www.merriamwebster.com/dictionary/conspiracy.

59 British Encyclopedia, “Conspiracy | Definition, Examples & Cases | Britannica,” 23 October 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/conspiracy.

60 Karlyn Bowman and Andrew Rugg, “Public Opinion on Conspiracy Theories,” 2013. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1296991/public-opinion-on-conspiracy-theories/1900250/.

61 Matthew Robinson, “The 9/11 Terrorist Attacks: 20 Years Later,” Journal of Crime and Criminal Behavior 2, no. 1 (2022): 1–28.

62 Bader et al., “Fear Itself,” 40.

63 Byford, “Towards a Definition,” 21.

64 Matteo Cinelli, Gianmarco De Francisci Morales, Alessandro Galeazzi, Walter Quattrociocchi, and Michele Starnini, “The Echo Chamber Effect on Social Media,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of Sciences of the United States of America 118, no. 9 (2 March 2021): e2023301118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2023301118.

65 Soroush Vosoughi, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral, “The Spread of True and False News Online,” Science 359, no. 6380 (9 March 2018): 1146–51. doi:10.1126/science.aap9559.

66 Alessandro Bessi, Mauro Coletto, George Alexandru Davidescu, Antonio Scala, Guido Caldarelli, and Walter Quattrociocchi, “Science vs Conspiracy: Collective Narratives in the Age of Misinformation,” PLoS One 10, no. 2 (2015): e0118093.

67 Adam M. Enders, Joseph E. Uscinski, Michelle I. Seelig, Casey A. Klofstad, Stefan Wuchty, John R. Funchion, Manohar N. Murthi, Kamal Premaratne, and Justin Stoler, “The Relationship Between Social Media Use and Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories and Misinformation,” Political Behavior 45, no. 2 (2023): 781–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09734-6.

68 Martin Innes, Diyana Dobreva, and Helen Innes, “Disinformation and Digital Influencing after Terrorism: Spoofing, Truthing and Social Proofing,” Contemporary Social Science 16, no. 2 (15 March 2021): 241–55. doi:10.1080/21582041.2019.1569714; Brigitte L. Nacos, Yaeli Bloch-Elkon, and Robert Y. Shapiro, “Selling Fear: Counterterrorism, the Media, and Public Opinion,” in Selling Fear (University of Chicago Press, 2011); James A. Piazza, “Fake News: The Effects of Social Media Disinformation on Domestic Terrorism,” Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict 15, no. 1 (2 January 2022): 55–77. doi:10.1080/17467586.2021.1895263.

69 An important counter finding is produced by Debrael et al. “Media Use, Fear of Terrorism, and Attitudes towards Immigrants and Refugees,” who fail to detect a significant relationship between social media and online news reliance and fear of terrorism.

70 Bader et al., “Fear Itself,” 40.

71 Onat et al., “Fear of Terrorism and Fear,” 906.

72 Nellis, “Gender Differences in,” 331.

73 Onat, “Media, Neighborhood Conditions,” 123.

74 Markus Kaakinen, Atte Oksanen, Shana Kushner Gadarian, Øyvind Bugge Solheim, Francisco Herreros, Marte Slagsvold Winsvold, Bernard Enjolras, and Kari Steen-Johnsen, “Online Hate and Zeitgeist of Fear: A Five-Country Longitudinal Analysis of Hate Exposure and Fear of Terrorism After the Paris Terrorist Attacks in 2015,” Political Psychology 42, no. 6 (2021): 1019–35. doi:10.1111/pops.12732.

75 Allcott, Hunt, and Matthew Gentzkow, “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31, no. 2 (2017): 211–36; Mark Dredze, David A. Broniatowski, and Karen M. Hilyard, “Zika Vaccine Misconceptions: A Social Media Analysis,” Vaccine 34, no. 30 (2016): 3441; Yuxi Wang, Martin McKee, Aleksandra Torbica, and David Stuckler, “Systematic Literature Review on the Spread of Health-Related Misinformation on Social Media,” Social Science & Medicine 240 (2019): 112552.

76 Byford, “Towards a Definition,” 21; Cinelli et al., “The Echo Chamber,” 5; Vosoughi et al., “The Spread of,” 2.

77 Daniel Allington, Bobby Duffy, Simon Wessely, Nayana Dhavan, and James Rubin, “Health-Protective Behaviour, Social Media Usage and Conspiracy Belief during the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency,” Psychological Medicine, 1–7. Accessed October 24, 2023. doi:10.1017/S003329172000224X. Bessi et al., 8. Aengus Bridgman, Eric Merkley, Peter John Loewen, Taylor Owen, Derek Ruths, Lisa Teichmann, and Oleg Zhilin, “The Causes and Consequences of COVID-19 Misperceptions: Understanding the Role of News and Social Media,” Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 1, no. 3 (2020); Benjamin J. Dow, Amber L. Johnson, Cynthia S. Wang, Jennifer Whitson, and Tanya Menon, “The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Search for Structure: Social Media and Conspiracy Theories,” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 15, no. 9 (2021): e12636. doi:10.1111/spc3.12636; Kathleen Hall Jamieson, and Dolores Albarracin, “The Relation between Media Consumption and Misinformation at the Outset of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in the US,” The Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 2020; Innes et al., 2149; Daniel Romer and Kathleen Hall Jamieson, “Conspiracy Theories as Barriers to Controlling the Spread of COVID-19 in the US,” Social Science & Medicine 263 (2020): 113356; Carl Stempel, Thomas Hargrove, and Guido H. Stempel, “Media Use, Social Structure, and Belief in 9/11 Conspiracy Theories,” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 84, no. 2 (2007): 353–72. doi:10.1177/107769900708400210.

78 Adam M. Enders, Joseph E. Uscinski, Michelle I. Seelig, Casey A. Klofstad, Stefan Wuchty, John R. Funchion, Manohar N. Murthi, Kamal Premaratne, and Justin Stoler, “The Relationship Between Social Media Use and Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories and Misinformation,” Political Behavior 45, no. 2 (2023): 781–804. doi:10.1007/s11109-021-09734-6.

79 Anna Greenburgh and Nichola J. Raihani, “Paranoia and Conspiracy Thinking,” Current Opinion in Psychology 47 (2022): 101362; Marcel Meuer and Roland Imhoff, “Believing in Hidden Plots Is Associated with Decreased Behavioral Trust: Conspiracy Belief as Greater Sensitivity to Social Threat or Insensitivity towards Its Absence?” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 93 (2021): 104081.

80 Türkay Salim Nefes, “Political Parties’ Perceptions and Uses of Anti-Semitic Conspiracy Theories in Turkey,” The Sociological Review 61, no. 2 (2013): 247–64. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12016; Turkay Salim Nefes, “Scrutinizing Impacts of Conspiracy Theories on Readers’ Political Views: A Rational Choice Perspective on Antisemitic Rhetoric in Turkey,” The British Journal of Sociology 66, no. 3 (2015): 557–75. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12137.

81 Marina Abalakina-Paap, Walter G. Stephan, Traci Craig, and W. Larry Gregory, “Beliefs in Conspiracies,” Political Psychology 20, no. 3 (1999): 637–47. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00160; Roland Imhoff and Martin Bruder, “Speaking (Un–)Truth to Power: Conspiracy Mentality as a Generalised Political Attitude,” European Journal of Personality 28, no. 1 (2014): 25–43. doi:10.1002/per.1930.

82 Bradley Franks, Adrian Bangerter, and Martin W. Bauer, “Conspiracy Theories as Quasi-Religious Mentality: An Integrated Account from Cognitive Science, Social Representations Theory, and Frame Theory,” Frontiers in Psychology 4 (2013): 424.

83 Miroslaw Kofta, Grzegorz Sedek, and Patricia Natally Slawuta, “Beliefs in Jewish Conspiracy: The Role of Situation Threats to Ingroup’ Power and Positive Image,” in 34th International Society of Political Psychology (ISSP) Conference, Istanbul, Turkey, 2011; Ali Mashuri and Esti Zaduqisti, “We Believe in Your Conspiracy If We Distrust You: The Role of Intergroup Distrust in Structuring the Effect of Islamic Identification, Competitive Victimhood, and Group Incompatibility on Belief in a Conspiracy Theory,” Journal of Tropical Psychology 4 (2014): e11; Robert Thomson, Naoya Ito, Hinako Suda, Fangyu Lin, Yafei Liu, Ryo Hayasaka, Ryuzo Isochi, and Zhou Wang, “Trusting Tweets: The Fukushima Disaster and Information Source Credibility on Twitter,” in Iscram, 2012; Van Prooijen, Jan-Willem, and Karen M. Douglas, “Belief in Conspiracy Theories: Basic Principles of an Emerging Research Domain,” European Journal of Social Psychology 48, no. 7 (2018): 897–908. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2530.

84 Codebook and data available online at chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.chapman.edu/wilkinson/research-centers/babbie-center/_files/Babbie%20center%20fear2021/wave-7-american-fears-methodology-report-v2-06.15.21.pdf (Data accessed 30 May 2023).

85 Contact the authors for comparisons between the survey sample and U.S. demographic statistics.

86 Specifically we use the “sgmediation2” statistical package designed for Stata by Trenton Mize. For details on this package, please see: https://www.trentonmize.com/software/sgmediation2.

87 Q16S in Chapman University American Fears Survey.

88 Q18R in Chapman University American Fears Survey.

89 We inverted subject responses to simply analysis.

90 χ2 = .733 ***.

91 Results available from authors.

92 χ2 = .265 ***.

93 Q9C in Chapman University American Fears Survey.

94 Q9K in Chapman University American Fears Survey.

95 Questions Q20A, Q20C, Q20D, Q20E, Q20F, Q20G, Q20H, Q20I in Chapman University American Fears Survey. Note, we exclude from the variable Q20B because it asks subjects whether they believe the government is hiding what it knows about the 9/11 terrorist attacks, a subject that is related to the dependent variable of the study. When this question is included in the variable, the results are the same. Results available from the authors.

96 χ2 ranges between .3877 *** and .5996 ***. Note, responses to all eight conspiracy questions are Likert scale responses: strongly agree; agree; disagree; strongly disagree. These are inverted in our analysis to ease interpretation.

97 Note, media modes are not mutually exclusive categories and subjects were able to report consuming high (or low) levels of consumption of different types of media at the same time.

98 PAGEFINAL in Chapman University American Fears Survey. Note, the age measure is an ordinal indicator for the age category of subject: 1 = 18–29; 2 = 30–49; 3 = 50–64; 4 = 65 and older.

99 Q36 in Chapman University American Fears Survey.

100 Z8 in Chapman University American Fears Survey measured as ordinal indicator of highest level of schooling achieved by subject.

101 Z9 and Z9B in Chapman University American Fears Survey.

102 EMPLOY in Chapman University American Fears Survey.

103 PRACE in Chapman University American Fears Survey.

104 PRELIGION in Chapman University American Fears Survey.

105 Q3 in Chapman University American Fears Survey.

106 PREGION in Chapman University American Fears Survey.

107 Q5 in Chapman University American Fears Survey.

108 Q4 (inverted) in Chapman University American Fears Survey.

109 Or, a 5.7% increase in fear of terrorism for each unit increase in use of online or social media to obtain news.

110 Bader et al., “Fear Itself,” 40; Oksanen et al., “Perceived Societal Fear,” 1057; Onat et al., “Fear of Terrorism and Fear,” 905.

111 Williamson et al., “Fear of Terrorism,” 12.

112 Jonathan Jackson and Emily Gray, “Functional Fear and Public Insecurities about Crime,” The British Journal of Criminology 50, no. 1 (2010): 1–22.

113 Hunt Allcott and Matthew Gentzkow, “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 31, no. 2 (2017): 211–36; Byford, Towards a Definition,” 21; Cinelli et al., “The Echo Chamber,” 5; Dredze et al., “Zika Vaccine,” 2; Vosoughi et al., “The Spread of,” 2; James A. Piazza and Ahmet Guler, “The Online Caliphate: Internet Usage and ISIS Support in the Arab World,” Terrorism and Political Violence 33, no. 6 (18 August 2021): 1256–75. doi:10.1080/09546553.2019.1606801; Wang et al., 7.

114 O’Mahony, Cian, Maryanne Brassil, Gillian Murphy, and Conor Linehan, “The Efficacy of Interventions in Reducing Belief in Conspiracy Theories: A Systematic Review,” PLoS One 18, no. 4 (5 April 2023): e0280902. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280902. Galende, Borja Arroyo, Gustavo Hernández-Peñaloza, Silvia Uribe, and Federico Álvarez García, “Conspiracy or Not? A Deep Learning Approach to Spot It on Twitter,” IEEE Access 10 (2022): 38370–78. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3165226.

115 Todd C. Helmus, “Artificial Intelligence, Deepfakes, and Disinformation: A Primer,” RAND Corporation, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep42027.

116 Authors, HKS Misinformation Review Guest, “Tackling Misinformation: What Researchers Could Do with Social Media Data,” Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 9 December 2020. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-49.

117 Silverman et al., “Putting Terror in,” 209; Erin M. Kearns, Allison E. Betus, and Anthony F. Lemieux, “Why Do Some Terrorist Attacks Receive More Media Attention Than Others?” Justice Quarterly 36, no. 6 (19 September 2019): 985–1022. doi:10.1080/07418825.2018.1524507.

118 William Marcellino, Todd C. Helmus, Joshua Kerrigan, Hilary Reininger, Rouslan I. Karimov, and Rebecca Ann Lawrence, “Detecting Conspiracy Theories on Social Media: Improving Machine Learning to Detect and Understand Online Conspiracy Theories,” RAND Corporation, 29 April 2021. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA676-1.html.

119 Cian O’Mahony, Maryanne Brassil, Gillian Murphy, and Conor Linehan, “The Efficacy of Interventions in Reducing Belief in Conspiracy Theories: A Systematic Review,” PLoS One 18, no. 4 (5 April 2023): e0280902. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280902.

120 Emma F. Thomas, Lucy Bird, Alexander O’Donnell, Danny Osborne, Eliana Buonaiuto, Lisette Yip, Morgana Lizzio-Wilson, Michael Wenzel, and Linda Skitka, “Do Conspiracy Beliefs Fuel Support for Reactionary Social Movements? Effects of Misbeliefs on Actions to Oppose Lockdown and to ‘Stop the Steal’.” British Journal of Social Psychology n/a, no. n/a. Accessed 15 February 2024. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12727.

Appendix

Table A1. Descriptive statistics.

Table A2. Use of social media and online websites for news and fear of terrorism, full model results.

Table A3. Estimating separately use of social media and online websites for news and fear of terrorism.

Table A4. Mediation results, estimating separately use of social media and online websites for news and fear of terrorism.