Abstract

While numerous researchers have taken a macro approach to assessing the state of the field of terrorism studies, little has been done to better understand one vital sub-section: women and terrorism. Despite women’s active and supportive participation in terrorism and political violence, it is often repeated that they are overlooked, under-analyzed, and ignored in the research which has often taken a gender-blind approach. Yet, there has been notable growth in this literature since 9/11. The rise of the Islamic State, and women’s active participation in the group, also drove a new wave of research and analysis on women and terrorism. Now, fifty years since the emergence of terrorism studies, and over two decades since 9/11, this article asks how has the state of literature on women and terrorism evolved? This article reviews the academic literature on women and terrorism through the examination of 661 articles, books, and chapters published from 1970 through 2021 on the topic—the largest such review to date. This study uses a quantitative approach to examine 17 data points including the authorship, publication, research focus, methods, and data trends within the field of women and terrorism. By doing so, this project builds on its predecessors by examining the exponential leaps in this field of research at the macro level and how it has evolved over the last fifty years, particularly in relation to terrorism studies more generally. This work finds that there is now definitively a significant and important body of research that exists on women and terrorism, but that key limitations in this body of work persist.

While women have been active and supportive participants in terrorism and political violence throughout history, women have generally been stated to be overlooked in the field of study more generally.Footnote1 With the first well-known major review of women and terrorism literature published in 2009,Footnote2 the rise of the Islamic State (IS) from 2014 drove a new wave of research and analysis on women and terrorism, with many researchers claiming that this was still an “under researched field” that required more attention. Now, over two decades after 9/11, and approximately five decades after the emergence of terrorism studies we ask: how has the state of literature on women and terrorism evolved over the last fifty years? This review seeks to build on and expand from its predecessors by examining the exponential leaps in this field over the last fifty years, and consider key trends in areas such as authorship, focus, and methodology, amongst others. It also aims to determine how more recent analysis on the topic of women and terrorism has evolved, and how its evolution more broadly contrasts or aligns with strengths and limitations in the larger field of terrorism studies.

This article reviews the literature on women and terrorism from 1970 through 2021 by examining 661 academic articles, chapters, and books across seventeen data points thus making it the most in-depth review on this topic to date.Footnote3 This study is a quantitative literature review which examines authorship, publications, research focus, methods, and data trends within the field of women and terrorism. By doing so, this research hopes to address at the macro level an understanding of the field of research on women and terrorism over the last fifty years. In contrast to popular belief that women are generally overlooked in this field, this article demonstrates that there is in fact a long history of academic inquiry and analysis of women’s roles in terrorism, and that this inquiry has expanded notably in recent years—researchers can no longer state that “women and terrorism” are overlooked in this field. And yet, research shows that literature on women and terrorism is not well incorporated into the field of terrorism research at large.Footnote4 More so, women and terrorism as a sub-field has not been holistically analyzed, nor evaluated to see how it has evolved over time. Without such an evaluation, there is a risk of ongoing prioritization of select research themes (groups, regions, ideologies, etc.), or limited reflection on potentially problematic trends (e.g. proliferation of one-time authors, Western-centric focus of researchers, etc.). This article aims to ultimately present the state of the field of research on women and terrorism since the founding of this field thereby allowing researchers to consider where to take research on this topic next, and where and how to improve various aspects of this body of work.

The Complexities of Studying Women and Terrorism

Reviewing the current state of the literature has a long and important history in academia and has proved particularly important for the young field of terrorism studies,Footnote5 which has, over the years, leveled much criticism against itself, even while making significant and positive changes within the field. While individual research on a phenomenon allows for a micro examination of an issue, a review of the state of the literature allows for academics to better understand the current state of the field, identify gaps or methodological shortfalls, and pinpoint areas of future research potential. The need for this review has been particularly prompted by an influx of literature on this phenomenon of women and terrorism, without yet taking stock of the state of this literature and considering how it stands up to the critiques of those raised more generally in terrorism studies.

Before 9/11, several important studies were conducted that sought to identify key problems with terrorism research, including addressing how researchers gathered data, the methodological tools used, and the level of analysis.Footnote6 One finding common throughout almost all the review articles was the reliance on secondary data and the dependence on qualitative research methods. While relevant and important studies, the state of terrorism has evolved significantly in the last 25 years. A deluge of research occurred in the post 9/11 environment, and with it came a new analysis reviewing the state of the literature.Footnote7 These authors acknowledged the drastic increase in research since 9/11, and even a rise in collaborative research between multiple authors, but pointed to some pitfalls, including a continued use of secondary data,Footnote8 and the fact that a majority of the articles in the field of terrorism studies were authored by “one-time research visitors to the field” which significantly hampered the continuity in the field of study.Footnote9

When looking at the corpus of research in the field of terrorism studies, many authors focused solely on terrorism journals to understand the main trends in the field.Footnote10 However, one study found that many of the 100 most cited articles on terrorism were published outside of traditional terrorism journals.Footnote11 Thus, a new wave of research has sought to pull from a larger corpus of literature.Footnote12 While the above literature reviews have contributed fascinating insights about the field of terrorism studies, they were gender blind. More specifically, none of the above studies directly addressed issues related to women and terrorism as a research focus—which we believe is an important and growing sub-focus in the wider field. This literature seeks to amend that and assess if some of the general trends in terrorism studies more widely also mirror those in this subfield of women and terrorism.

Reviewing Women and Terrorism

Using a diverse toolbox of tactics, including suicide attacks, bombings, stabbings, airplane hijackings, vehicular attacks, kidnapings, and assassinations, the research methodologies used to study the phenomenon of terrorism are just as numerous as its modus operandi.Footnote13 The research on women and terrorism has been traditionally studied under the disciplines of political science, sociology, psychology, communications, criminology, and women’s studies, amongst others.Footnote14 Thus, research on women and terrorism focuses on a variety of topics including the event, motivations, causes, psychological reasons that underlie involvement, identity, radicalization, strategies, implications, religion, gender, and the roles of the individual and the organizations.Footnote15

While our review starts in 1970, authors have been looking at women as terrorist actors for decades prior.Footnote16 For example, an article in a 1952 edition of The Russian Review, “The Case of Vera Zasulich” discussed the case of the woman charged for the attempted murder of the Governor of the State of St. Petersburg, Fydor Trepov in 1878.Footnote17 Zasulich, who remained at the scene after the attack famously stated why she did not flee, “I am a terrorist, not a murderer.”Footnote18 She wanted it to be known that there were political motivations behind her actions. Though women have been involved in political violence long before this, Zasulich’s case is often highlighted as one of the first of contemporary acts of political violence by a woman (especially those recognized under Rapoport’s four waves of modern terrorism).Footnote19

While research has looked at the state of terrorism research in general, very few comprehensive reviews have been carried out on the state of literature on women and terrorism. While many authors have struggled to build up current research on women and terrorism, including the authors of this article, very few have chosen to create an entire article reviewing said literature. The most well-known first “formal” review of the state of literature was Karen Jacques & Paul J. Taylor’s (2009) “Female Terrorism: A Review” (Terrorism and Political Violence).Footnote20 This vitally important study examined 54 publications, using both qualitative and quantitative analysis. Overall, this study found a continued reliance on secondary sources, an overreliance on narrative analysis, an inexplicable reluctance to describe rather than explain events. While a groundbreaking study for its time, and still a bedrock of research on women and terrorism, this review utilized a small sample size, with only 54 publications, including traditionally reviewed books and articles published in peer-reviewed journals, it also included conference reports and proceedings, PhD theses, and reports published by leading counter-terrorism centers.

While other authors have reviewed aspects of the scholarship,Footnote21 or released useful bibliographies on women and terrorism,Footnote22 critical examinations of the literature on women and terrorism are still underrepresented. In 2020, Margaret Gonzalez-Perez published an article entitled “Women, Terrorist Groups, and Terrorism in Africa.”Footnote23 This article is important for two reasons. First, it is one of the most recent—and one of only a handful of—review articles on women and terrorism, and second, it looks at one of the most under examined regions in the field—Africa. The study looked at women’s agency, societal norms, and gendered expectations. It also raised unique concerns about current literature on this subject, as in the African context in particular much of the information “is presented through a Western lens.”Footnote24 Yet, Gonzalez-Perez’s qualitative interrogation of a select five cases studies also limits broader trends in the field more generally.

Most recently, Davis et al. (2021) examined how “well-integrated” research on women and terrorism was in the broader field of terrorism studies, measuring the “impact or influence of the subfield.”Footnote25 For this, they undertook citation analysis, while also considering the topic, group/ideology, and region of study of 448 publications between 1996 and 2020. Differing from our study, Davis et al. chose to extend beyond academic literature alone to include “semi-academic publishers,” and include literature on insurgent and guerilla groups, in English, French, and Spanish. They found that between 2007 and 2016 approximately 7% of terrorism research focused on women and terrorism. The most significant finding the authors found was that despite the growing sub-field of women and terrorism, it is often poorly cited in the terrorism literature at large. Specifically, they found that about a third of all publications on women and terrorism had no scholarly citations at all; 35% had 1–5 citations and 34% had between six and 427 citations (mean average of 10).Footnote26 This proves a significant (and welcome) contribution to the field, and raises important questions about how literature on women and terrorism fits into the larger field of terrorism research (and indeed, how it is taken up by this field). Our piece complements and builds further off of this via a larger data set, and more critically focuses on the contours of the field and study of women and terrorism itself.

Finally, other authors have made contributions to the field indirectly. For example, when examining authorship in terrorism studies, Phillips (2023) found the important growth of women authorship in the field of terrorism studies more generally, particularly those from other fields such as psychology. The author hypothesizes that this could be due to increasing mentorship and role models.Footnote27 This review thus helps consider if this growth in women authors in this field may also influence the focus and expansion of research on women and terrorism.

This research project, examining fifty years of research on women and terrorism, builds on these important studies mentioned above, especially inspired by the work of Jacques and Taylor (2009). This paper critically assesses the literature that has been published to date to address at the macro level an understanding of the field of research on women and terrorism.

Methodology

This study examines the state of the literature on women and terrorism over the last fifty years, from 1970 through 2021.Footnote28 The literature on terrorism has traditionally fallen under terrorism studies, with articles found in traditional terrorism journals including: Terrorism and Political Violence (TPV), Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (SCT), Perspectives on Terrorism, the Combating Terrorism Center Sentinel (CTC Sentinel), Critical Studies on Terrorism, Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict, Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, Journal of Terrorism Research, and the Journal for Deradicalization (JDR, 2014–present).Footnote29 As noted above, many of the reviews of the literature have thus often featured in these core terrorism journals.Footnote30 However, as shown by Silke and Schmidt-Petersen, some of the most cited articles in terrorism research have been published outside of the core terrorism journals.Footnote31 As noted by Davis et.al., the study of women has often been considered “gendered,” and due to a “gender ghetto,” authors examining women and terrorism have more actively (as our findings also confirm) chosen to publish beyond these journals, and have ventured into the fields of gender studies, feminist theory, critical studies, psychology, communications, defense, criminology, and more.Footnote32

Identifying and Collecting the Data

In order to create the dataset used for this article and capture a wide breadth of publications from multi-disciplinary fields, the authors drew from the methodological work of Schuurman (2019; 2020) to better assess and compare trends in the field more generally,Footnote33 and employed two sequential steps to ensure the widest possible literature could be identified. We began by using a fixed set of both broad and targeted search termsFootnote34 in Google Scholar and the Library of Congress catalog that we believed were best suited to identify research focused on women and terrorism.Footnote35 In Google Scholar, these targeted searches were reviewed up to at least the thirtieth page of each individual search result in all cases, or further until the authors deemed the results were exhausted. Secondly, this was supplemented and cross checked through an examination of the popular terrorism journals and book publishers, as well as sample bibliography reviews of some of the most popular publications to ensure all relevant literature was being accounted for in the search. After applying the considerations discussed below, the final dataset included 661 solely academic publications comprising books, edited volumes, chapters, articles, and special issues published between the years 1970 and 2021 on women and terrorism. The year 1970 was chosen as a starting point as contemporary literature generally refers to this period as the starting point of contemporary terrorism studies.Footnote36 This detailed literature review took the authors five years to complete.

By moving beyond traditional terrorism journals, which in and of themselves decide what articles to include in their publications, we were faced with a dilemma as to how to define terrorism for the scope of this article, and the classification of groups to be included or excluded. Insurgents, armed groups, terrorist organizations, and rebels have at times been labeled interchangeably risking a search bias that may limit certain articles which preferred a term other than “terrorism” which also had the potential to exclude literature on regions where these insurgencies have more frequently taken place (e.g. South America, Africa, and Asia).

One initial consideration was to only include groups that had been listed by the US or UK as a foreign terrorist organization, which were indeed utilized.Footnote37 However, the U.S. only started designating terrorist groups in 1997, while the U.K. only started after the passing of the Terrorism Act 2000, which risked excluding many relevant groups and thus publications.Footnote38 Furthermore, due to political and domestic considerations in the U.S. and U.K. policy driving the definition of domestic terrorism,Footnote39 it was decided that to unilaterally use this criteria was too narrow of a scope. For example, domestic law enforcement in the U.S. has identified the significant threat posed by a range of domestic actors and movements, with Christopher Wray, the Director of the FBI, defining domestic violent extremists as “individuals who commit violent criminal acts in furtherance of ideological goals stemming from domestic influences, such as racial bias and anti-government sentiment.”Footnote40 Historically right-wing extremism, specifically domestically, has been left off terrorism designation lists, however, a growing number of far right groups have been designated as terrorist groups.Footnote41

As such, the authors of this article decided to include domestic terrorist groups (those often related to the far right), even when not designated as such by governments.Footnote42 Moreover, many single-issue groups are not designated. For example, one book looked at the use of terrorism by suffragettes,Footnote43 while another publication looked at single issue terrorism as a neglected field and considered both suffragettes and animal rights activists.Footnote44 Thus, the secondary threshold for inclusion (beyond official designation) was if the author of the academic article or book defined the group or individual as a terrorist actor or a terrorist act. This also meant that the rich body of research on rebel governance was excluded from this analysis. For example, articles referencing women in rebel groups in Eritrea or Nepal, have been excluded, while all Northern Ireland related terrorist groups or women in the KKK have been included. This also suggests that some of the research on women in leftist groups that were prominent in South America, for example, may be excluded under this criteria, unless there were specific references to them as “terrorists” within the publications. Furthermore, the authors observed an extensive body of work that discussed “domestic terrorism” as it related to intimate partner violence,Footnote45 which we also excluded, even though recently there has been more of an attempt to bridge research on domestic intimate partner violence and political violence.Footnote46

Publications included in our dataset were limited to academic books, edited volumes, book chapters, and articles published in peer-reviewed journals. Articles were only included if the primary focus was women as terrorist actors, or if it contained a substantial stand-alone section on women, or compared women’s and men’s participation. Books were included if the entire book was on women. If only a chapter or specific section focused on women, the specific chapter of interest was cited. In cases where edited volumes or special editions focused on women and terrorism the stand-alone publication was cited, as well as each relevant chapter or article within. Updated editions of books were only referenced once using the original publication date. If women were mentioned in passing, or appeared to be of cursory focus, then these articles and books were excluded. The full reading list is available as an external document that can be requested from the authors.

The authors were aided in the data collection process by several research assistants, whose invaluable work was checked by the authors during regularly held weekly meetings (see acknowledgements). Throughout this process, the authors checked the sample, addressed any highlighted concerns, and double checked all cases that were included and excluded from the sample. To ensure coding reliability, each of the authors checked the entire sample, flagging any discrepancies in the coding process, and addressing these issues together. The data was aggregated and placed into Microsoft Excel. The data collection began in early 2019 and concluded in 2023.

The Coding Process

Guided by the methodological work of Schuurman (2019; 2020), this article examines seventeen data points focused on the following information: 1) title, 2) year of publication; the author(s) [including 3) names, 4) the number of authors, and the deduced 5) location and 6) perceived gender of the authors];Footnote47 7) publication type;Footnote48 8) name of the publication; 9) group name;Footnote49 10) ideology;Footnote50 11) region;Footnote51 12) methodology;Footnote52 13) number of groups discussed;Footnote53 14) the use of primary or secondary sources;Footnote54 15) the type of data source;Footnote55 16) if the research compared men to women, or looked exclusively at women; and 17) keywords.Footnote56 When breaking down the coding process in each of these data points, the authors decided to create specific coding categories as elaborated in the footnotes, rather than using open ended coding.

These categories not only describe this body of literature more generally but can also help highlight trends and evolutions in this field. For example, the name, number, and location of authors can speak to trends of co-authorship in the field, and to confirm whether Silke’s concerns that 90% of research studies in this field are single authored, or that 80% of research in this field is from one timers.Footnote57 The perceived gender of the author can also help determine if it is largely female authors driving the growing research on this topic, while the location of the authors can also help us consider whether the study of women and terrorism also aligns with assertions that research produced in the Western states, specifically the U.S. and U.K., dominates this field. The publication type highlights where this literature is finding an audience, including whether this is largely within or outside of, traditionally terrorism studies journals. Group name, ideology, and region help us consider thematically which groups are being emphasized (and which are not). Methodological trends can also help us see whether broader quantitative trends, or qualitative interrogations are predominant, the latter of which may speak in a more detailed manner to the “who, what, when, where, and why” questions in the study of women and terrorism. The questions around data sources speak to the general health of this field, while distinguishing whether articles consider men and women or just women, which helps highlight concerns of the potential siloed nature of this subject. Finally, the keywords tell us what is being focused on in this literature—the thematic focus in this body of work.

Limitations

To date, this is the largest study of its kind to examine the literature on women and terrorism. To be clear, this is an article on women and terrorism, and not gender and terrorism.Footnote58 While the authors are aware of—and have even taken part in—the many epistemological debates in the field, this article does not seek to engage with such debates. Gender is defined as a social construct, and the research and language used to discuss women and gender has evolved significantly in the last fifty years.Footnote59 However, historically articles referencing gender in relation to women have often focused on women as a specific group of interest (noun), while describing gendered features or considerations of those women. To be as inclusive with the data as possible, and ensure some of this literature is not overlooked, the authors have utilized both the terms gender and sex in our search of the literature.

As noted in the data collection section, publications included in the review were limited to academic books, edited volumes, chapters, special issues, and articles published in peer-reviewed journals. The authors thus excluded conference reports and proceedings, PhDs, government reports, news, and long-read articles, as well as reports, articles, and blogs published by other centers including think tanks, bodies like the UN, I/NGOs, and research centers. We acknowledge that this list of excluded publications contains many influential pieces of research often cited in the field.Footnote60 Whether due to the funding available for research through such institutions; the speed with which publications can be released (particularly in relation to timely, topical issues); the desire for academics to more directly influence policy and practice; or multiple institutional affiliations that scholars and researchers may hold; many authors choose to publish work outside of the traditional peer-review process, utilizing the publication and dissemination efforts of think tanks, international organizations, and non-governmental organizations.Footnote61 While the level of quality-control peer review processes may differ amongst these, the impact that they may have amongst policymakers and practitioners is noteworthy, and this field should be acknowledged for the research it can and has produced. Despite this, for the purpose of this review these articles are excluded.

A secondary limitation that must be acknowledged is that the authors only searched and included English language publications in this study. This may mean that some literature or groups appear underrepresented in this literature (e.g. German literature on RAF). In countries with a much longer history of both leftist violence, or nationalist or far right violence, including diverse countries such as Sri Lanka, Turkey, or Germany, this may mean that there is in fact much more non-English research written on this topic than has been identified here. The authors acknowledge that even with this review process, no methodology is perfect, and there is a risk that some publications may have been overlooked.

A third limitation is related to our keyword analysis. The list of keywords utilized in our dataset came from two sources. First, from the articles themselves where possible, and second, for the remaining articles, the authors came up with the keywords ourselves. Moreover, as noted by Schuurman, the assignment of keywords is an arbitrary and biased process and may misrepresent the totality of the article.Footnote62 However, by utilizing 661 articles and 3,305 keywords, we hope to convey the scope of the issues focused on without skewing the data. Also, by removing keywords that are already anticipated by the focus of this article (e.g. women, female, terrorism) we believe we sufficiently captured the thematic areas represented by these publications.

Findings

The findings of our study are explored below in five main sections: main trends, authorship trends, research trends, methodological trends, and keyword trends.

Main Trends

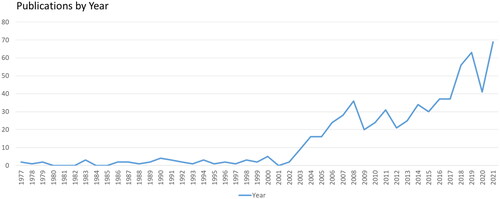

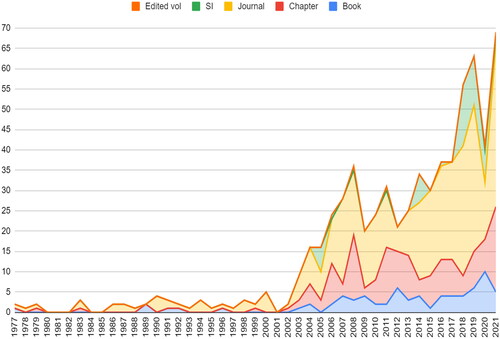

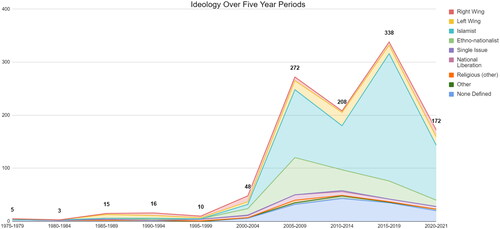

Between 1970 and 2021, a total of 661 articles on women and terrorism were published and included in this study. While our study began in 1970, the first piece of research included in our dataset was only published in 1977 (see Appendix B for the full list of articles published each year).Footnote63 The number of articles written that discussed women and terrorism remained fairly static between 1970 and 2000 and increased notably and consistently after 2004 (see ).Footnote64 For example, the years 1970–2000 (30 years of scholarship) saw 42 articles discussing women and terrorism, while the years 2001 − 2021 (20 years of terrorism scholarship) saw 619 published. The top three years for publications on women and terrorism have all been since 2018: 2021 (69 articles), 2019 (63 articles) and 2018 (56 articles).

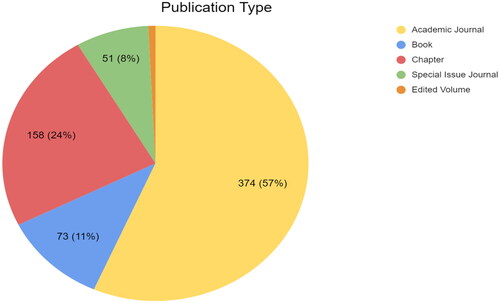

The publication type is also notable: journal articles have comprised 57% of all publications, followed by book chapters (24%), books (11%), and special issue journals (8%) (see ).

Special issues tended to align with higher periods of publications on women and terrorism as can be seen in . Discussing trends where research on women and terrorism was being published, of the 661 publications ultimately included only 105 (16%) of these were in the top nine terrorism journals (see methodology). More precisely, only 25% of the total 425 peer-reviewed articles were published in the top nine terrorism journals. This included Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (55),Footnote65 Terrorism and Political Violence (21), Critical Studies on Terrorism (8), CTC Sentinel (8), Perspectives on Terrorism (5), Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression (3), Journal of Terrorism Research (2), Journal for Deradicalization (2) and Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict (1).

This suggests that most of the literature on women and terrorism may not be as readily identified by scholars and researchers which prioritize these key journals in the field. This in turn lends to the perception that women are often overlooked in the study of terrorism, but also highlights that literature on women and terrorism is not as incorporated into the field of terrorism studies at large (echoing the finding of Davis, West, and Amarasingam (2021) who note the poor integration of literature on women and terrorism into the broader field of terrorism studies). One possible explanation for this is that many scholars writing about women and terrorism appear to hail from other fields (e.g. criminology, psychology, war studies, police studies, regional studies, etc.). For example, International Annals of Criminology accounted for 14 articles while Women and Criminal Justice published 8 articles. There are also some feminist journals that featured prominently such as International Feminist Journal of Politics (8 entries), Journal of International Women’s Studies (5), and Feminist Review (4). However, and notably, it is mainstream terrorism journals (Studies in Conflict & Terrorism and Terrorism and Political Violence in particular) which host the most research on women and terrorism, not those such as Critical Terrorism Studies which may appear more likely to engage in debates around gender stereotypes, perceptions, or roles as they pertain to female terrorists.

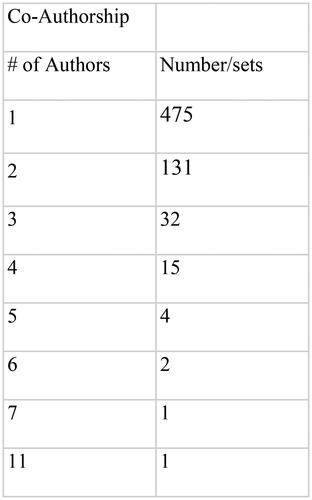

Another key trend identified was in relation to authorship which speaks to not only the longevity and focus of individual authors in the field, but also trends in collaboration versus single authorship. Of the 661 publications reviewed 475 (72%) were single authored, and 186 (28%) were co- or multi-authored (see ). In relation to co- and multi-authored articles, the majority of these were co-authored, while one publication had up to 11 authors.Footnote66 This is in line with trends in terrorism captured by Silke (2003) who noted 83% of publications were single-authored, though our findings suggest this is slightly better in relation to authorship on women and terrorism.Footnote67

The number of times a single author published was also noteworthy. The most published authors on this subject in the dataset are Caron Gentry (15 publications); Laura Sjoberg and Mia Bloom (12 publications each); Kathleen Blee (11 publications); followed by Anat Berko, Edna Erez, and Katherine Brown (8 publications each). Only eight other authors had written over five publications on this topic.Footnote68 Notably, these are all perceived female authors,Footnote69 and while today they are well known names in the field of terrorism studies, they all hail from different academic fields.Footnote70

The field of terrorism studies has often been considered a “man’s world,” but the sub-field of women in terrorism is most certainly “a woman’s world” with 69% (653) of the authors being female, and only 31% (289) male. This suggests that female authors in particular have seen a need to highlight the roles of women in terrorism, or research the participation of women in terrorism where this was previously overlooked. It also raises questions about why fewer male authors do not research this topic.

The topic of women and terrorism is dominated by authors from what could be described as “the west.” Notably of the 943 author locations listed across all publications: 448 (48%) were published by authors located in North America; 261 in Western Europe (28%); followed by Asia (7%), MENA (5%), Africa (5%), Eastern Europe (5%), Australia (4%), and South America (<1%). There were no noted authors from the Caribbean, and only one author of an unknown region. This is in line with the broader trend of western-dominated perspectives in the study of terrorism which may overlook important scholarship or scholars in some of the areas most impacted by terrorism, and suggests a need to more actively engage with scholars and partners from regions of study.

Research Trends

In line with broader trends in terrorism studies reviews, the ideological focus of research on women and terrorism has primarily been focused on Islamist terrorism (52%) with the next closest being ethno-nationalist (16%), left-wing (9%), right-wing (5%), national liberation (3%), and other (1%).Footnote71 Notably, less than 1% of the publications that were identified as focusing predominantly or exclusively on women were categorized as focusing on single issue terrorism or other religious terrorism. Moreover, 13% of articles did not have an ideological focus, but rather spoke about women’s participation in terrorism more generally. This could suggest that those studying the topic are interested in developing theoretical or conceptual arguments around women’s roles in political violence. This also suggests that the field may know less about women’s participation in certain types of terrorism (e.g. single issue such as environmental, anti-abortion, etc.), but also that there is perhaps a disproportionate focus on their roles in Islamist terrorism. Furthermore, in notable movements such as the Red Army Faction (Germany) or the Italian Red Brigades who had many prominent female members, it is likely that much more analysis exists in German and Italian that is not accounted for here. These findings also encourage us to consider whether new and innovative research is being produced on women’s roles in Islamist terrorism, or whether much of this is repetitive in nature, pointing to similar themes and findings.

Many of the first studies published in their respective periods focused on left-wing ideology (1975–1979),Footnote72 ethno-nationalist ideology (1980–1984),Footnote73 or had no ideological focus (1975–1984).Footnote74 The first studies in our dataset focusing on women in right-wing ideology and national liberation ideologies were both published in 1986, respectively.Footnote75 Interestingly, the first study focusing on Islamist ideology was not published until 1990.Footnote76 However, Islamist ideology first became the most common ideological focus of any five-year period in 2005–2009 (128, or 47% during that period), peaked as the most common ideology in the 2015–2019 period (240, or 71% during that period), also remaining the most common ideological focus in 2020–2021 (103, or 60% during that period) (see ). These upticks notably aligned with both women’s roles with Al-Qaeda in Iraq from the mid-2000s, and later in the Islamic State from 2014 onwards, as well as the broader proliferation of the field of terrorism studies after 9/11. These research trends on ideology are largely in line with Rapoport’s four waves thesis which highlighted leftist terrorism (the third wave), where women “became leader and fighters once more,” and religious terrorism (the fourth wave) dominating the focus, where 9/11 can be seen as a catalyst in this period. It is notable that Rapoport notes in the first wave of anarchist terrorism women too played significant roles, though as our review shows, women did not garner much focus in this early period (also emphasized in the group focus below).Footnote77 This suggests that historical analysis of women’s roles in early terrorism remains overlooked in contemporary literature.

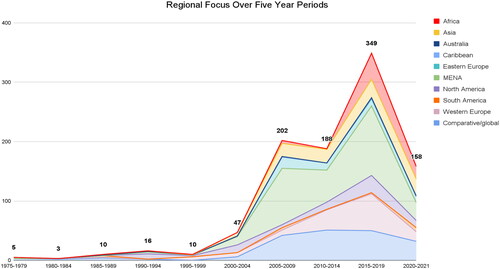

The regional focus in the field has also been, perhaps unsurprisingly, dominated by a focus on the MENA region which represents 32% of all research. Western Europe (14%), Asia (11%), North America (8%), Africa (7%), Eastern Europe (6%), and South America (2%) fall far behind, while less than 1% of publications focused on Australia or the Caribbean. 19% of articles took a comparative focus. This finding aligns with other authors who have highlighted not only the significant uptick in terrorism research after 9/11, but also the predominant focus on Islamist terrorism.

The first studies published in their respective period include Eastern Europe (1975–1979),Footnote78 Western Europe (1980–1984),Footnote79 and global and comparative studies (1975–1984).Footnote80 The first study focusing on South America was published in 1986,Footnote81 the first about Asia in 1987,Footnote82 the first about North America in 1990,Footnote83 and the first about the MENA region in 1991.Footnote84 As shown in , studies focusing on the MENA region were the majority regional focus for each five-year time period beginning in 2000–2004 until 2015–2019. Global and comparative studies were the majority regional focus for 2020–2021 (20%) followed closely by the MENA region (19%) and Asia (18%). One study in 1995–1999 focused on Africa, while 44 studies from 2015 to 2019 and 21 studies from 2020 to 2021 focused on Africa.

There has also been a focus on specific groups/actors in the study of women and terrorism that generally mirrors that of the broader field of terrorism studies. Notably, the groups and broader ideological categories which have gained the most significant focus are AQI/ISIS (17%), Palestinian Nationals (8%), Hamas (7%) al-Qaeda (6%), LTTE (5%), other Islamists (5%), Palestinian Islamic Jihad (5%), Chechen (5%), right-wing (4%), left-wing (3%), Boko Haram (3%), and the German Red Army Faction (3%). All remaining groups made up less than 2% of the publications respectively, including the IRA, Al-Shabaab, PKK, ETA, Weather Underground, FARC, Taliban, Hezbollah, Red Brigades, FLN, and Shining Path. 3% of articles focused on groups beyond those listed (i.e. “other groups”), while 15% of articles did not focus on a specific group (for a full list of group focus, see Appendix C).

The first studies about AQI/ISIS were published in 2005.Footnote85 From 2005 to 2009, 5% (13) of the publications were about AQI/ISIS, and from 2010 to 2014, 7% (15) of the publications were about AQI/ISIS. Publications about AQI/ISIS peaked in frequency from 2015 to 2019 at 34% (114) but remained the most popular group focus from 2020 to 2021 at 26% (45), in line with the international attention placed on ISIS as it mobilized tens of thousands of foreigners to join its ranks in Iraq and Syria, and the notable international attacks perpetrated by the group and its followers.Footnote86

Methodological Trends

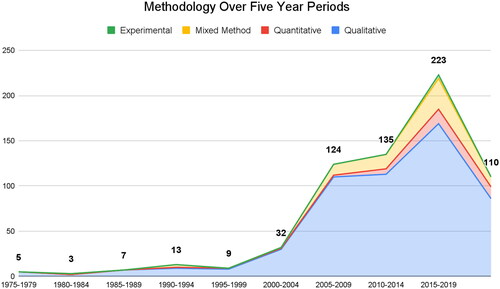

Next, we considered methodological trends in the literature on women and terrorism. Notably, this field is dominated by qualitative research (582 articles, or 82%), with only a fraction engaging mixed methods (78, or 12%), quantitative (40, or 6%), or experimental methods (4, or <1%).

Qualitative research is the most common research methodology used across all five-year periods since 1975 (see ). The first study using mixed methodology research was published in 1983,Footnote87 and the first study using only quantitative methodology was published in 1990.Footnote88 All four experimental studies were published in the 2015–2019 time. This predominance of qualitative research suggests a trend in the field to interrogate questions about what women’s roles are, why they are participating, and assessing the implications of this in the field. There was also a predominance of multi-organizational (i.e. comparative) focus in articles (375, or 57%) over singular organizations examined (286, or 43%). This points to a desire to consider women’s role and participation in terrorism comparatively across different groups. Within these articles, they have most frequently focused exclusively on women (505, or 76%) over comparative cases which have examined the roles of men and women simultaneously (156, or 24%). This may suggest that those authors writing on women and terrorism often study men and women independently in assessments of groups, versus viewing these groups and all their actors in a holistic fashion.

While there has been a sizable amount of primary data sources used, 43% of research used at least one primary source, this has fallen short of the field of terrorism studies more generally where Schuurman recorded 58% using at least one primary source (see Appendix D for the full breakdown).Footnote89 While it is difficult to discern the decision behind why authors decided to not use primary sources in research, one possible reason could be that those studying this body of research are focused on developing theoretical and conceptual arguments around women and terrorism. For example, as noted above 13% of articles did not have an ideological focus, but rather spoke about women’s participation in terrorism more generally. That being said, the lack of primary source data suggests that scholars interested in the subject of women and terrorism should prioritize more primary data sources when possible to advance new and unique empirical findings.

Keyword Trends

Finally, we examined the keyword trends. In order to delve into the findings of keyword trends on women and terrorism, as noted in the methodology, we excluded the words female, women, and terrorism from our keyword analysis. We decided to leave the word gender in order to see how women in terrorism were studied in relation to gender and gender roles. The ten most common keywords (including stemmed words) found in the 661 articles were:

gender, gendered, gendering—134 (4.01%)Footnote90

suicide bomber/s, suicide bombings—133 (3.98%)

role/s—115 (3.44%)

ISIS—103 (3.08%)

fighter/s—82 (2.46%)

jihad, jihadi, jihadism, jihadist—76 (2.28%)

radical/s, radicalism, radicalization—67 (2.01%)

motivate/s, motivation/s—63 (1.89%)

media—60 (1.80%)Footnote91

recruitment, recruiter—44 (1.32%)

An examination of the top ten most common words overall suggests that interrogations of gendered roles and dynamics around women’s involvement (including their violent roles), particularly their roles as suicide bombers and fighters, media narratives around women, and women’s motivations to participate in terrorist violence, have dominated the research on women and terrorism. In line with the methodological trends, these lines of research have been largely qualitative in their nature. Notably, these keywords suggest a focus on women joining groups (motivations, recruitment, radicalization), their roles and particularly violence in groups, and how these women are portrayed in the media. Notably absent are a focus on processes after one has joined a group, including disengagement, deradicalization, rehabilitation, reintegration, and so forth.

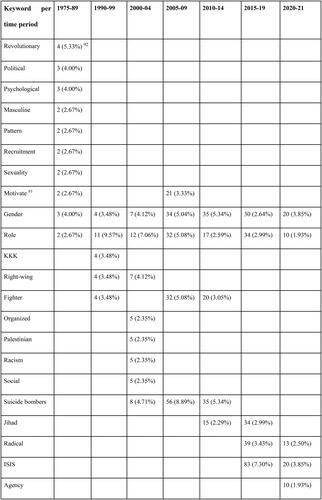

Next, we decided to look at the top-five most frequently used keywords per five-year period. Due to small sample size in the early years of research, we decided to group together the early years of research before 2000 (i.e. 1975–1989 and 1990–1999). We found that the most common keywords were as follows (for a full list, see Appendix E; see ):

One thing that is clear through analysis of the keywords is that the field of terrorism has tended to respond to trends in the world in that particular period—a tendency shared with terrorism studies more broadly. The period of 1975 to 1989 for example considers revolutionary terrorism, and the psychological state of terrorist actors—an initial trend in terrorism studies which considered the psychological state of terrorists. The 1990s saw a focus on right-wing extremism, particularly women in the KKK—a body of work largely driven by Kathleen Blee. The first half of the 2000s saw a rise of women suicide bombers, largely driven by Palestinian militants during the second intifada, but also the LTTE in Sri Lanka and “black widows” in Chechnya. The latter half of the 2000s continued to focus on women as suicide bombers, where al-Qaeda in Iraq now too was contributing to this trend.

There was also more focus being placed on women’s motivations to join terrorist groups, and their roles including those of fighters and suicide bombers. This focus on suicide terrorism aligns with the trend in terrorism studies more broadly where Schuurman too noted that suicide terrorism was a top trend in 2007,Footnote92 though this extended for a period of fifteen years in the case of women suicide bombers suggesting a fixation on women’s most violent participation in terrorist movements. Suicide bombers continued to be a focus between 2010 and 2014, where there was now a focus as well on jihadism that would continue until the end of the dataset—another trend in the field of terrorism studies more broadly.Footnote93 Unsurprisingly, women’s roles in jihad dominated the field in 2015–2019, particularly their roles in ISIS between 2015 − 2019 as thousands of women from around the world traveled to Iraq and Syria to join ISIS, even as their roles were a combination of domestic and more diverse across different aspects of the “caliphate.”Footnote94 Discussions of women’s agency also start appearing in 2020–2021 suggesting that the field was focusing more intently on nuances in women’s participation in political violence.

It is notable that such trends around gendered roles and dynamics do not appear to be reflected in studies of terrorism more generally (especially male militants).Footnote95 This suggests that gendered interrogations of actors vis-à-vis terrorism has been driven by scholarship on women, and also that scholarship on women has prioritized gendered interrogations of their participation.Footnote96

Conclusions and Future Thoughts

This review has thoroughly examined research over the last 50 years on women and terrorism. It has built on, further validated, and extended from some of the early (and scarce) reviews in the field (see section “Reviewing Women and Terrorism”) in several important ways. These include tracing the “sharp growth” in publications that Jacque and Taylor (2009) observe over a longer period of time and confirming that research trends they identified continue today (e.g. portrayal in the media, roles, motivation and recruitment), and concerns about the use of secondary data. While distinct from Davis, West, and Amarasingam (2021) we echo their concerns about how integrated, and indeed recognized, this literature on women and terrorism is, and further validate their findings around thematic, regional, and group focus in this field. We also further validate their findings around specific thematic focus on women’s participation and roles, framing in media, and roles in suicide terrorism (though again, on strictly academic literature). Overall, this paper has also further expanded the data points used in analysis over a wider period on strictly academic literature while providing new and original analysis of this data. As our research found overall, this field of scholarship on women and terrorism remains very young, predominantly produced by Western women, authoring alone, and published outside of key terrorism journals. Research trends highlight that over half of this literature has focused on Islamist terrorism in the MENA region, is qualitative research, with less than half using at least one primary source. The keywords indicate that women’s motivations to join a group, and their roles in groups and portrayal in the media retained the highest focus, and indicate a responsive nature to key events of the day, yet notably neglect the processes after which women join groups—a significant research gap.

By presenting these findings we hope this presents an opportunity to reflect on the field of terrorism studies more generally, and particularly to prompt further inquiry into the trends identified above. For example, these findings raise important questions about why this literature—as expansive as we demonstrate it is—has not been more actively recognized in the field of terrorism studies, or those of political violence more broadly. For example, as noted in the findings, only 25% of the total 425 peer-reviewed articles in this dataset were published in the top nine terrorism journals. If women were not on the front lines of combat, it suggests that their roles were not considered as frequently in analysis of terrorist organizations. It also speaks to broader trends highlighted by scholars like Enloe, who asked “where are the women?” and have noted that while women have always been present in international politics, they have often been overlooked due to a male-dominated nature and focus of this field.Footnote97 Yet, this research suggests that women are no longer necessarily overlooked in research, but in fact that they are being increasingly focused on, but in specific subjects (recruitment, roles, media portrayal), which could be problematic for more holistic considerations of aspects of women and terrorism. Such a narrow and repetitive focus also risks a growing body of literature that doesn’t extend to new or under-researched topics, notably in areas such as rehabilitation, reintegration, vis-a-vis new and emerging technologies, and others. It could also simply reflect broader trends where terrorist actors are predominantly men, and women’s involvement in fact may receive disproportionate attention relative to their participation.

This review also raises important observations about researchers and authorship in the field of women and terrorism studies including where most researchers in this field hail from (this continues to be Western dominated), and how frequently they publish or co-publish (there is still a notable trend of single authorship and one-time authorship). This suggests a need to partner with or promote authorship from local researchers in affected areas including Africa and the MENA region. It also highlights that research on women and terrorism tends to be more qualitative in its nature, and focused on several dominant themes (e.g. their most violent roles, their motivations to join a group, and media representation). Understanding these data trends has important implications for the field of study. For example, if researchers all hail from certain regions, their world view likely dominates our understanding of the issue at hand. If people only publish once and never again, it highlights the lack of research building on itself and the overall growth of the field. These are concerns that have already been raised in wider reviews of the field. We may also consider the implications of female authors largely studying women and terrorism. For example, does this suggest that this subject matter may be a more welcoming entry point or focus for female scholars to the field of terrorism studies, or are female scholars more likely to focus on a subject matter that they perceive as overlooked in the wider field? This could be explored more in qualitative discussions with female (and male) scholars in this field to better understand why scholars prioritize the subjects they do, and help us reflect on the implications of this for the field.

As we continue to observe women’s participation in terrorist activities, in a variety of regional conflicts and driven by multiple ideologies, as scholars of terrorism we can perhaps reflect more on themes that have been overlooked or under-researched. For example, there could be more focus on certain overlooked regions (e.g. Africa, South America). New trends related to terrorist technologies, AI, or other contemporary issues could also be investigated in relation to their impacts and implications for both men and women involved in political violence. As translation technologies become more advanced, this may open up opportunities for scholars to tap into literature from other languages (for example, German or Spanish) which may help offer insights from these affected regions. Cases or examples from under-studied groups or regions may also offer useful insights to the field more generally instead of the field continuously creating “new” knowledge without fully integrating knowledge developed over decades of scholarship. Finally, instead of focusing on women in terrorism alone, future research is encouraged to consider terrorist actors more generally and aspects such as gendered roles, motivations, or ideological features for a more holistic understanding of such groups as they apply to both men and women.

We hope that future research will reflect on the findings from this data set and delve deeper into some of the analysis and areas for future research presented above to focus on the research trends and continued gaps and shortfalls in this literature itself. Encouragingly though, we can now definitively say that a significant and important body of research exists on women and terrorism.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback which enriched this piece further. We would also like to thank our research assistants (in order of most recent participation): Camille Jablonski, Avery Schmitz, Mallory Thompson, Brandon Miller, William Feigert, Amy Sinnenberg, Hallie Thomas, Jacqueline Schultz, Allison Dong, Sara Kropf, and Rebecca Visser for their assistance on this project. Finally, the authors would also like to thank the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, the Program on Extremism, Leiden University and the International Center for Counter-Terrorism, the Hague for facilitating this review.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

For access to the dataset, please contact the authors directly.

Notes

1 For example: Laura Sjoberg and Caron E. Gentry, eds. Women, Gender, and Terrorism (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011); Karla J. Cunningham, “Cross-Regional Trends in Female Terrorism,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 26, no. 3 (2003): 171–95, doi: 10.1080/10576100390211419; Karen Jacques and Paul J. Taylor, “Female Terrorism: A Review,” Terrorism and Political Violence 21, no. 3 (2009): 499–515, doi: 10.1080/09546550902984042; Margaret Gonzalez-Perez, “Women, Terrorist Groups, and Terrorism in Africa,” in The Palgrave Handbook of African Women’s Studies, ed. Olajumoke Yacob-Haliso and Toyin Falola (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 603–20, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-77030-7_93-1; Jessica Davis, Leah West, and Amarnath Amarasingam, “Measuring Impact, Uncovering Bias? Citation Analysis of Literature on Women in Terrorism,” Perspectives on Terrorism 15, no. 2 (2021): 58–76, https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/binaries/content/assets/customsites/perspectives-on-terrorism/2021/issue-2/davis-et-al.pdf.

2 Jacques and Taylor, “Female Terrorism: A Review,” 499–515.

3 As noted by Silke, terrorism studies is still rather young, “existing in a meaningful sense since the late 1960s.” As such, the authors decided to start the review in 1970, as the first academic conferences and academic gatherings date back to the early 1970s. In doing so, this allows us to look at 50 years of literature. Andrew Silke, “Contemporary Terrorism Studies: Issues in Research,” in Critical Terrorism Studies: A New Research Agenda, ed. Richard Jackson, Marie Breen Smyth, and Jeroen Gunning (London: Routledge, 2009), 34–48, doi: 10.4324/9780203880227.

4 Jessica Davis, Leah West, and Amarnath Amarasingam, “Measuring Impact, Uncovering Bias? Citation Analysis of Literature on Women in Terrorism.”

5 It is important to acknowledge that significant contributions to the field of terrorism studies sometimes come from outside of terrorism studies journals.

6 Alex P. Schmid and Albert J. Jongman, Political Terrorism: A Research Guide to Concepts, Theories, Data Bases and Literature (Amsterdam: SWIDOC, 1982), 418; Alex P. Schmid and Albert J. Jongman, Political Terrorism: A New Guide to Actors, Concepts, Data Bases, Theories, and Literature (Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing, 1988). Schmid and Jongman’s seminal work used surveys to gather information from terrorism researchers and analysts on their experiences in the field. Furthermore, the author’s themselves compiled one of the most extensive bibliographies on political terrorism to date. Prior to the rise of the internet, the authors found sources for the bibliography from: The New York Public Library, the Library of Congress, the Widener Library (Harvard), British Library, University Library of Leiden. Publications were divided into an impressive 20 major categories (and 46 subcategories), addressing issues such as conceptual issues, insurgent terrorism, mass communication of terrorism, ideologies, psychological, criminological and military perspectives, and terroristic activities by region to name a few; Ted Robert Gurr, “Empirical Research on Political Terrorism: The State of the Art and How It Might Be Improved,” in Current Perspectives on International Terrorism, ed. Robert O. Slater and Michael Stohl (London: Macmillan Press, 1988), 115; Ariel Merari, “Academic Research and Government Policy on Terrorism,” Terrorism and Political Violence 1, no. 3 (1991): 88–102, doi: 10.1080/09546559108427094; John Horgan, “Issues in Terrorism Research,” The Police Journal 70, no. 3 (1997): 193–202, doi: 10.1177/0032258X9707000302; Martha Crenshaw, “The Psychology of Terrorism: An Agenda for the 21st Century,” Political Psychology 21, no. 2 (2000): 405, doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00195; and Andrew Silke “The Devil You Know: Continuing Problems with Research on Terrorism,” Terrorism and Political Violence 13, no. 4 (2001): 1–14, doi: 10.1080/09546550109609697.

7 Andrew Silke, “The Road Less Travelled: Trends in Terrorism Research,” in Research on Terrorism: Trends, Achievements and Failures, ed. Andrew Silke (London: Frank Cass, 2004), 183–84, doi: 10.4324/9780203500972; Andrew Silke, “An Introduction to Terrorism Research,” in Research on Terrorism: Trends, Achievements and Failures, ed. Andrew Silke (London: Frank Cass, 2004), 12–15, doi: 10.4324/9780203500972; Andrew Silke, “Research on Terrorism: A Review of the Impact of 9/11 and the Global War on Terrorism,” in Terrorism Informatics, ed. Hsinchun Chen, Edna Reid, Joshua Sinai, Andrew Silke, and Boaz Ganor, vol. 18, Integrated Series in Information Systems (Boston, MA: Springer, 2008), 27–50, doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-71613-8_2; Silke, “Contemporary Terrorism Studies: Issues in Research,” 34–48; Magnus Ranstorp, “Mapping Terrorism Studies After 9/11: An Academic Field of Old Problems and New Prospects,” in Critical Terrorism Studies: A New Research Agenda, ed. Richard Jackson, Marie Breen Smyth, and Jeroen Gunning (London: Routledge, 2009), 13–33.

8 Silke, “Research on Terrorism: A Review of the Impact of 9/11 and the Global War on Terrorism.”

9 Ranstorp, “Mapping Terrorism Studies After 9/11: An Academic Field of Old Problems and New Prospects,” 13–33.

10 Silke, “The Devil You Know: Continuing Problems with Research on Terrorism,” 1–14; Bart Schuurman, “Topics in Terrorism Research,” Critical Studies on Terrorism 12, no. 3 (2019): 463–80, doi: 10.1080/17539153.2019.1579777; Bart Schuurman, “Research on Terrorism, 2007–2016: A Review of Data, Methods, and Authorship,” Terrorism and Political Violence 32, no. 5 (2020): 1011–26, doi: 10.1080/09546553.2018.1439023.

11 Andrew Silke and Jennifer Schmidt-Petersen, “The Golden Age? What the 100 Most Cited Articles in Terrorism Studies Tell Us,” Terrorism and Political Violence 29, no. 4 (2017): 692–712, doi: 10.1080/09546553.2015.1064397.

12 Joseph K. Young and Michael G. Findley, “Promise and Pitfalls of Terrorism Research,” International Studies Review 13, no. 3 (2011): 411–31, doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2486.2011.01015.x; Michael J. Boyle, “Progress and Pitfalls in the Study of Political Violence,” Terrorism and Political Violence 24, no. 4 (2012): 527–43, doi: 10.1080/09546553.2012.700608; John F. Morrison, “Talking Stagnation: Thematic Analysis of Terrorism Experts’ Perception of the Health of Terrorism Research,” Terrorism and Political Violence 34, no. 8 (2022): 1509–29, doi: 10.1080/09546553.2020.1804879.

13 Pamala L. Griset and Sue Mahan, Terrorism in Perspective (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2003).

14 Jacques and Taylor, “Female Terrorism: A Review,” 499–515.

15 Ibid.; Young and Findley, “Promise and Pitfalls of Terrorism Research,” 411–31.

16 Winthrop Lane, “The Making of a Russian Revolutionist. An Interview with Marie Sukloff,” The Survey 32 (1914): 257–26.

17 Samuel Kucherov, “The Case of Vera Zasulich,” The Russian Review 11, no. 2 (1952): 86–96, doi: 10.2307/125658.

18 Beatrice De Graaf and Alex P. Schmid, eds., Terrorists on Trial: A Performative Perspective (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2016), 60.

19 David C. Rapoport, “The Four Waves of Modern Terrorism,” in Attacking Terrorism: Elements of a Grand Strategy, ed. Audrey Kurth Cronin and James Ludes (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press 2004).

20 Jacques and Taylor, “Female Terrorism: A Review,” 499–515.

21 For example: Emmanuel-Pierre Guittet, “Gendered Political Violence: Female Militancy, Conduct and Representation in Contemporary Scholarship – A Review,” International Feminist Journal of Politics 20, no. 2 (2018): 274–81, doi: 10.1080/14616742.2016.1257336.

22 Judith Tinnes, “Bibliography: Defining and Conceptualizing Terrorism,” Perspectives on Terrorism 14, no. 6 (2020): 204–36. While Tinnes’s piece was an important contribution to the literature by aggregating journal articles, book chapters, books, edited volumes, theses, and other resources, no new analysis took place.

23 Margaret Gonzalez-Perez, “Women, Terrorist Groups, and Terrorism in Africa,” in The Palgrave Handbook of African Women’s Studies, ed. Olajumoke Yacob-Haliso and Toyin Falola (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 603–20, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-77030-7_93-1.

24 Gonzalez-Perez 2020, 617.

25 Davis, West, and Amarasingam, “Measuring Impact, Uncovering Bias? Citation Analysis of Literature on Women in Terrorism,” 58.

26 Ibid., 67.

27 Brian J. Phillips, “How did 9/11 affect terrorism research? Examining articles and authors, 1970–2019,” Terrorism and Political Violence 35, no. 2 (2023), 423.

28 We focused on women as perpetrators and excluded cases that solely focused on women’s victimization at the hands of an organization. i.e., ISIS and Yazidi women.

29 For a more comprehensive list see: Judith Tinnes, “A Resources List for Terrorism Research: Journals, Websites, Bibliographies (2018 Edition),” Perspectives on Terrorism 12, no. 4 (2018): 115–42.

30 Silke, “The Road Less Travelled: Trends in Terrorism Research,” 183–4; Young and Findley, “Promise and Pitfalls of Terrorism Research,” 411–31; Schuurman, “Topics in Terrorism Research: Reviewing Trends and Gaps, 2007–2016,” 463–80; Schuurman, “Research on Terrorism, 2007–2016: A Review of Data, Methods, and Authorship,” 1011–26.

31 Silke and Schmidt-Petersen, “The Golden Age? What the 100 Most Cited Articles in Terrorism Studies Tell Us,” 692–712.

32 Davis, West, and Amarasingam, “Measuring Impact, Uncovering Bias? Citation Analysis of Literature on Women in Terrorism,” 58. See also: Jacques and Taylor, “Female Terrorism: A Review,” 499–515; Schuurman, “Topics in Terrorism Research: Reviewing Trends and Gaps, 2007–2016,” 463–80; Schuurman, “Research on Terrorism, 2007–2016: A Review of Data, Methods, and Authorship,” 1011–26. This article’s methodology took inspiration from these three texts.

33 Our article has particularly utilized many of the same categorizations highlighted by Schuurman to allow for not only a review of the state of the literature on women and terrorism, but also to allow for future reflections on how this compares to the broader field of terrorism studies. Schuurman, “Topics in Terrorism Research: Reviewing Trends and Gaps, 2007–2016,” 463–80; Schuurman, “Research on Terrorism, 2007–2016: A Review of Data, Methods, and Authorship,” 1011–26.

34 These terms included: Female and Terror; Female and Terrorism; Gender and Terror; Gender and Terrorism; Women and Terror; Women and Terrorism; Women and Suicide Terrorism; Women and Suicide Bombings; Female and Suicide Terrorism; Female and Suicide Bombings; Female Fighters and Terror; Female Fighters and Extremism; Women and Violent Extremism; Female and Violent Extremism; Women and Jihad; Women, Terrorism + 1) Red Army Faction 2) Red Brigades 3) Africa 4) Sri Lanka 5) Columbia 6) Palestine 7) right-wing 8) left-wing 9) ETA 10) weather underground 11) direct action 12) Ireland 13) shining path and 14) environmental terrorism, 15) domestic terrorism.

35 Despite this article focusing on women and terrorism, the authors decided to include “gender and terror/terrorism” in our searchers. While we are aware of the diverse gendered identities, and that gender is a social construct, we recognize that gender has historically been associated with women and wanted to ensure that our list captured this (problematic) trend. We excluded any literature that discussed gender as related solely to men, gender relations, or gender analysis, though future research could also consider how gender has been analyzed in relation to men, masculinity, and political violence. We understand that this list of search terms may not be exhaustive, however, we believe that they have been able to capture the widest breadth of research possible.

36 See, for example, Lisa Stampnitzky, Disciplining Terror: How Experts Invented ‘Terrorism’ (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 7.

37 “Foreign Terrorist Organizations,” United States Department of State, Bureau of Counterterrorism, https://www.state.gov/foreign-terrorist-organizations/ (accessed 1 February 2019); “Proscribed Terrorist Groups or Organisations,” Home Office, Last Modified November 26, 2021, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/proscribed-terror-groups-or-organisations–2/proscribed-terrorist-groups-or-organisations-accessible-version (accessed 1 February 2019); “Homeland Threat Assessment (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Washington, DC, 2020), https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/2020_10_06_homeland-threat-assessment.pdf (accessed 1 November 2020). In the US concerns from domestic terrorism highlight homegrown violent extremists and white supremacist extremists as the two greatest threats from 2020. DHS further highlights racially and ethnically motivated violent extremism, as well as that from anti-government or anti-authority groups.

38 Beck, Colin J., and Emily Miner, “Who Gets Designated a Terrorist and Why?” Social Forces 91, no. 3 (2013): 837–72.

39 “The Department defines domestic terrorism as an act of unlawful violence, or a threat of force or violence, that is dangerous to human life or potentially destructive of critical infrastructure or key resources, and is intended to affect societal, political, or other change, committed by a group or person based and operating entirely within the United States or its territories. Unlike HVEs, domestic terrorists are not inspired by a foreign terrorist group.” U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “Strategic Framework for Countering Terrorism and Targeted Violence,” September 2019.

40 Christopher Wray, “Worldwide Threats to the Homeland” (Statement Before the House Homeland Security Committee, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Washington, DC, 2020), https://www.fbi.gov/news/testimony/worldwide-threats-to-the-homeland-091720 (accessed 20 September 2020); “Department of Homeland Security Strategic Framework for Countering Terrorism and Targeted Violence” (U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Washington, DC, 2019). The U.S. Department of Homeland Security themselves acknowledges this issue, pointing to the fact that “many groups and individuals defined as “domestic terrorists” are becoming increasingly transnational in outlook and activities. The current label we employ to describe them, which comes from the Federal Government’s lexicon, should not obscure this reality.”

41 Michael R. Pompeo, “United States Designates Russian Imperial Movement and Leaders as Global Terrorists” (Press Statement, U.S. Department of State, Washington, DC, 2020), https://2017-2021.state.gov/united-states-designates-russian-imperial-movement-and-leaders-as-global-terrorists/index.html (accessed 10 April 2020); Jamie Grierson, “UK to Ban Neo-Nazi Sonnenkrieg Division as a Terrorist Group,” The Guardian, Last Modified February 24, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/feb/24/uk-ban-neo-nazi-sonnenkrieg-division-terrorist-group (accessed 25 February 2020). This has begun to change as the U.S. designated the foreign-based Russian Imperial Movement and the U.K. has designated National Action and Sonnenkrieg Division.

42 Yasmine Ahmed and Orla Lynch, “Terrorism Studies and the Far Right – The State of Play,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 47, no. 2 (2021): 199–219, doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2021.1956063.

43 Simon Webb. The Suffragette Bombers: Britain’s Forgotten Terrorists (Pen and Sword History: South Yorkshire, 2014).

44 Rachel Monaghan, “Single-Issue Terrorism: A Neglected Phenomenon?” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 23, no. 4 (2000): 255–65.

45 For example, Straus, Murray A., and Kristi L. Gozjolko, “‘Intimate Terrorism’ and Gender Differences in Injury of Dating Partners by Male and Female University Students,” Journal of Family Violence 29 (2014): 51–65; Frye, Victoria, Jennifer Manganello, Jacquelyn C. Campbell, Benita Walton-Moss, and Susan Wilt, “The Distribution of and Factors Associated with Intimate Terrorism and Situational Couple Violence among a Population-Based Sample of Urban Women in the United States,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 21, no. 10 (2006): 1286–313.

46 See, for example, Laura Sjoberg and Caron E. Gentry, “Introduction: Gender and Everyday/Intimate Terrorism,” Critical Studies on Terrorism 8, no. 3 (2015): 358–61; Rachel Pain, “Everyday Terrorism: Connecting Domestic Violence and Global Terrorism,” Progress in Human Geography 38, no. 4 (2014): 531–50 and more recently Caron E. Gentry, “Misogynistic Terrorism: It Has Always Been Here,” Critical Studies on Terrorism 15, no. 1 (2022): 209–24.

47 The authors acknowledge that it is a delicate matter to determine the perceived gender of an author. As we were unable to carry out a collection of gender identity survey data, we have decided to code the likely perceived gender of the authors. We followed the same methodology as Phillips (2023), to determine the perceived gender of an author, using “a combination of first names if highly likely to be indicative (e.g., David or Linda), photographs on websites if available, and pronouns used to refer to the author if found.” While this was sufficient information for most scholars, we acknowledge that this is not a foolproof method, and apologize if we mis-gendered any of the authors.

48 Each piece of research was also coded as either an edited volume, book, chapter, journal article, or special issue journal.

49 Please see Appendix A for the full list of groups listed by name and their associated ideology. Groups that were mentioned fewer than five times were not given their own code but labeled as ‘other’. A note: groups with global affiliates like al-Qaeda have all been included under a single umbrella (e.g. AQIM, AQAP were all considered al-Qaeda). Individual groups that aligned with al-Qaeda but have since splintered off from al-Qaeda, such as Islamic State which had its roots in al-Qaeda in Iraq, have been distinguished from al-Qaeda Central (coded as AQI/Islamic State).

50 Ideologies included: ethno-nationalist, Islamist, left-wing, national liberation, religious (other), right-wing, single issue, and none defined.

51 Regions were divided into: Africa, Asia, Australia, Caribbean, Eastern Europe, MENA (Middle East North Africa), North America, South America, Western Europe, Comparative (comparing two regions)/global (when articles were thematic or global in scope), Other* refers to no region—these cases will be very rare. A note: Turkey crosses two continents but for the purposes of this data it is classified as Asia. This also means that groups like the PKK become difficult to place in a singular regional context as they transcend countries including Turkey, Iraq, and Iran. In this case, dependent on which country it was operating in, this was the region identified (for example: Turkey = Asia, Iraq and Syria = MENA).

52 While acknowledging the categories created by Silke and used by Schuurman, the authors of this research divided research methodology into qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. The authors acknowledge that both inferential and descriptive statistics were lumped together as quantitative research. Articles were only codified as quantitative if the research was carried out by the authors and was not codified as such when reproduced from other sources. The bar for inclusion was low. For example, if the research used any form of qualitative or quantitative data, it was labeled as such. See: Silke “The Devil You Know: Continuing Problems with Research on Terrorism,” 1–14; Schuurman, “Topics in Terrorism Research: Reviewing Trends and Gaps, 2007–2016,” 463–80; Schuurman, “Research on Terrorism, 2007–2016: A Review of Data, Methods, and Authorship,” 1011–26.

53 A single case study is looking at a single organization. A comparative case study looks at multiple organizations.

54 The authors followed Schuurman’s lead in using the definition of primary sources derived from Princeton University: specifically, “Primary sources typically provide information based on the direct observation of, or participation in, a certain subject, whereas secondary sources relay such information indirectly.” The bar for inclusion was low. For example, if the research used any primary data, it was labeled as such. Schuurman, “Research on Terrorism, 2007–2016: A Review of Data, Methods, and Authorship,” 1011–26.

55 Types of data include: primary source documents, including: archival material, surveys/questionnaires, terrorist primary sources, interviews with third parties, interviews with terrorists, fieldwork-based research, experiments, personal experience/autobiographies. Secondary source documents, including: databases, secondary literature/data, literature reviews, media (film and artistic materials) analysis, journalism/news organizations, clinical psychological/psychiatric assessments, and court documents.

56 Unfortunately, not all articles included specific keywords, and those that did often had too few or too many. In such cases, the authors formulated these themselves based on the title and abstract of the paper. Each paper was given five keywords to describe the research. Words such as female and woman and terrorism were excluded, while words like gender, femininity and masculinity have been included. While all articles in this data set include women/female, the keywords provide insights into the research trends on this topic.

57 Silke, “The Road Less Travelled: Trends in Terrorism Research,” 69.

58 As noted, we excluded any literature that focused on gender alone (see footnote 35).

59 For example, UN Women defines gender as “the social attributes and opportunities associated with being male and female and the relationships between women and men and girls and boys, as well as the relations between women and those between men.” UN Women, “Concepts and Definitions,” https://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/conceptsandefinitions.htm (accessed 1 May 2024).

60 This has even meant excluding multiple relevant articles authored by the authors of this article.

61 E.g., UN and INGO or NGO reports, POE, ISD, ICSR, ICCT, RUSI, NCITE, CREST, etc.

62 Schuurman, “Topics in Terrorism Research.”

63 Vera Broido, Apostles into Terrorists: Women and the Revolutionary Movement in the Russia of Alexander II (Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1977).

64 This trend was also broadly captured by Davis, West and Amarasingam (2021) who noted research spikes in 2007, 2011, and 2016 in their unique data set.

65 This includes 55 in Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, and 5 from its predecessor Terrorism, which it eventually combined with. See Stampnitzky 2014, 43, footnote 28.

66 Pedro Manrique, Zhenfeng Cao, Andrew Gabriel, John Horgan, Paul Gill, Hong Qi, Elvira M. Restrepo, Daniela Johnson, Stefan Wuchty, and Neil Johnson, “Women’s Connectivity in Extreme Networks,” Science Advances 2, no. 6 (2016): e1501742.

67 Silke, “The Road Less Travelled: Trends in Terrorism Research.”

68 These included Anne Speckhard, Elizabeth Pearson, and Margaret Gonzalez Perez (7 each); Alexis Henshaw and Karla Cunningham (6 each); and Anita Peresin, Cindy Ness, and Jennifer Philippa Eggert (5 each).

69 It should also be noted that this does not mean that these, and other authors, have not also published on other topics in terrorism studies. Furthermore, pointing our readers to our coding and limitations sections, it should be acknowledged that this is the perceived gender of the authors. The authors themselves may identify differently, and if we have mis-gendered, we apologize.