Abstract

There has been a growing interest among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to analyze the online activities of extremists and terrorists. As studies in this research area have increased, various data collection techniques have emerged to address key research questions, ranging from manual extraction to computational tools to collect online information. This article examines the strengths and limitations of commonly used data collection methods in online terrorism and extremism research. We draw from our research experiences and highlight ethical dilemmas with collection methods in practice. We then set forth suggestions for progressing research in this space.

The role of the Internet in facilitating violent extremism and terrorism is a primary concern for many researchers, practitioners, and policymakers around the world.Footnote1 The so-called Islamic State (IS), an internationally designated terrorist organization, released a steady stream of video-recorded beheadings of Western hostages and other atrocity footage to radicalize some while intimidating others.Footnote2 Violent anti-fascist extremists used social media to instigate widespread violence against law enforcement during COVID-19 lockdowns and following George Floyd’s killing.Footnote3 Many of the right-wing extremists (RWEs) who engaged in violence during the Jan. 6 Capitol Riot also used online channels to coordinate and/or boast about their involvement.Footnote4 Understandably, law enforcement and intelligence communities have become invested in examining the digital footprints of violent extremist movements. It also comes as no surprise that online terrorism and extremism research have grown rapidly in recent years,Footnote5 with a variety of data collection techniques emerging to address key research questions in the space. The primary focus of this effort has been on extracting open-source, publicly available information from active data sources (e.g. social media platforms, websites, blogs, forums) and informative sources (e.g. online newspapers, government reports, existing databases).Footnote6

Open-source data collection strategies encompass a process of systematically identifying and accumulating relevant information from publicly available materials which can then be carefully mined, assembled, and codified.Footnote7 There are at least three advantages to using open-source research approaches. First, such an approach overcomes a variety of data challenges (discussed below), with previous research showing that the amount of information accessible is significant. Scholars have used this information to study problems in new ways.Footnote8 For these reasons, scholars have increasingly used open sources to study a range of issues including homicides,Footnote9 mass shootings,Footnote10 hate crimes,Footnote11 corporate crimes,Footnote12 and terrorism and violent extremism.Footnote13 Second, open sources capture more data that can be used to operationalize additional constructs to perform more refined tests of criminological theories.Footnote14 For example, research comparing open source to official data sources found that on every variable measured, open source methodologies captured as much or more information. In addition, variables not available in official data but useful for testing theory were only identified in open-sources, and difficult to capture geographic data were significantly more accessible in open-sources.Footnote15 Third, open sources seem ideally suited to study both rare events and difficult to access populations, including terrorists and violent extremists.Footnote16 Importantly, both the amount and type of data are not constrained by an outside source but are only limited by what is not presented in open sources.

Despite the growing efforts in online terrorism and extremism research to collect open-source information, little is known about the methodological, practical, and ethical challenges of open-source data collection in this research space particularlyFootnote17 or in terrorism and extremism studies generally.Footnote18 Instead, what we generally know comes from studies that briefly highlight limitations specific to a project or a particular research method. This article examines key strengths, limitations, and ethical concerns associated with open-source data collection methods commonly used in online terrorism and extremism research. The purpose of this article is to assist researchers and analysts in choosing between commonly used data collection methods based on their key strengths, limitations, and ethical concerns. In what follows, we examine computational and manual techniques for collecting extremist online content as well as offer suggestions for progressing research. By no means, however, do we include every study on, or trend in, data collection in online terrorism and extremism research. Instead, we focus on what we view as key current and emerging trends based on our involvement in the field. We have contributed to the expansion of online terrorism and extremism research, from developing computational tools for large-scale extraction and analysis of extremist content online at the International CyberCrime Research Centre (ICCRC),Footnote19 to creating the open-source database U.S. Extremist Cyber Crime Database (ECCD)Footnote20 to better understand online pathways to radicalization and mobilization. These experiences have provided us with unique insights regarding the usefulness of various open-source data collection efforts in online terrorism and extremism research.

Computational Techniques for Data Collection

Researchers, practitioners, and policymakers have argued that successfully identifying extremist online content (i.e. behaviors, patterns, or processes), on a large scale, is the first step in combating it.Footnote21 Yet it is estimated that the number of individuals with access to the Internet has more than doubled in the last 10 years, from over 2.4 billion users in 2012 to more than 5.4 billion as of 2022.Footnote22 With all of these new users, more information has been generated, leading to a flood of data. This has made it increasingly difficult to manually search for and collect online content in general or content posted by violent extremists, potentially violent extremists, or even users who adhere to extremist views because the Internet contains an overwhelming amount of information.Footnote23 These new conditions have necessitated the use of data collection methods that can side-step the laborious manual methods that traditionally have been used to identify and collect relevant information in online terrorism and extremism research.Footnote24

As a result of this evolving landscape, many law enforcement and intelligence communities have prioritized the development of large-scale tools to collect extremist online content for analytical purposes.Footnote25 Governments around the globe have also engaged researchers to develop automated and semi-automated data collection tools as well as advanced information technologies, machine learning algorithms, and risk assessment tools to identify and counter the threat of terrorism and violent extremism.Footnote26 Whether this work involves identifying extremist users of interest,Footnote27 measuring digital pathways of radicalization,Footnote28 or detecting virtual indicators that may prevent future terrorist attacks,Footnote29 the urgent need to collect and analyze terrorist and extremist content online, on a large scale, is a priority for law enforcement agencies and security officials worldwide.Footnote30 In what follows, we examine computational data collection techniques commonly used in online terrorism and extremism research to collect open-source information that fall within the purview of third party application programming interfaces (APIs), commercial crawlers, and custom-written crawlers.

Third Party APIs and Commercial Crawlers

Researchers have shown a vested interest in using web-crawlers to collect large volumes of content on the Internet since its inception,Footnote31 with this interest making its way into online terrorism and extremism research in the past 15 years.Footnote32 Web-crawlers, also known as “crawlers”, “data scrapers”, and “data parsers”, are the tools used by all search engines to automatically map and navigate the Internet and collect information about each website and webpage that a crawler visits.Footnote33 Once an end-user decides on a website from which parsing will begin, the crawler recursively follows the links from that webpage until some user-specified condition is met, capturing all content along the way. During this process, the software tracks all the links between it and other websites, and if an end-user so chooses, the software will follow and retrieve those links as well. As the content is retrieved, it is then saved to the user’s hard drive for later analysis. In short, most web-crawlers save the retrieved content onto a hard drive, essentially “ripping” a webpage or website because it contains content desired by the end-user.Footnote34

Third party APIs are but one example of a web-crawling technology used to examine the link between terrorism, extremism, and the Internet. APIs (Application Program Interfaces) are interfaces through which requests for a certain service can be made, to retrieve or store information, for example. APIs are commonly used by search engines, social media sites, and news media sites to interact with and obtain information from one another. Everyday examples include comparing prices for flights on one travel booking site, Google searching the local weather and receiving weather data from Apple’s Weather app, or shopping on an e-Commerce website and making a purchase with PayPal. Third party APIs are growing in popularity in online terrorism and extremism research, in part because of the relative ease of extracting large-scale data without the assistance of a computing scientist or technical support in general. Further, recently terrorists and violent extremists have exploited several key platforms that collect their online data via APIs, including IS’s prominent presence on Twitter and then later encrypted communication apps, such as Telegram.Footnote35

Social media platforms have provided researchers with access to, and subsequently large-scale downloading capabilities of, open-source, publicly shared information found on their sites via APIs (e.g. Twitter API, Facebook API, YouTube API, Instagram API, Reddit API, Telegram API).Footnote36 This has provided researchers with standard, simplified ways of collecting data that minimizes the need to clean, transform, or prepare the dataset. For these reasons, a growing body of literature is taking shape in online terrorism and extremism research that have collected data via APIs. Berger and Strathearn,Footnote37 for example, collected tweets from RWE accounts using Twitter’s API to examine the nature of social media interactions and the extent to which social media accounts were most influential in online networks. Scrivens and AmarasingamFootnote38 used Facebook’s API to extract data from prominent Canadian and Australian RWE group pages to assess their composition (e.g. the volume of content and types of posts that generated the most user engagement). Similar data collection tools were used by Hutchinson et al.Footnote39 to compare online mobilization efforts by Canadian and Australian RWE groups on their Facebook pages over time. Stall et al.Footnote40 collected Twitter data using its Access API Key to assess the meme environment surrounding the Kenosha shooting by Kyle Rittenhouse. Lastly, Thomas et al.Footnote41 collected tweets using Twitter’s API to examine how offline protests attended by Australian RWEs shape online interactions.

Similar to third party APIs, a variety of commercial and open-source tools are available for automated data collection and subsequent data analysis. These commercial-grade web-crawlers offer a variety of useful data filtering options via interactive interfaces, including filters on the data type collected and the source of that collection. To illustrate, filtering can be applied to content generally, such as language, location, date, author, and keyword. Data collection can also be filtered at a site level, such as domain name, site type (e.g. social media, blog, forum, news), or site section and category (e.g. news, sports, education, country of origin). Data collection of social media sites can be filtered by user engagement, such as number of likes, shares, comments, followers, ratings, comments, and so on.Footnote42 Indeed, a key methodological strength of commercial crawlers is their ability to offer flexibility in the data that can be included or excluded from collection efforts. Some commonly used data collection tools for open-source materials include Webhose.io (collection of structured data from news sites, blogs, forums, the dark web), Mozenda and Keyhole (search and collection of data from blogs, forums, social media using a set of keywords), Octoparse (collects unstructured data by choosing webpages to extract), and Social Mention (real-time search, monitoring, and collection of user-generated content from social media which is aggregated into a single stream of information).

Although used less frequently than third-party APIs, commercial crawlers have attracted some interest among those working in online terrorism and extremism research. Notable examples include LakomyFootnote43 who mapped the online propaganda campaign of a news media branch of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, a Salafi-jihadist organizations, collecting over 13,000 pieces of propaganda on its websites via a combination of SpiderFoot, a commercial-level reconnaissance application, and a Python script, among other data collection techniques. LakomyFootnote44 also examined the online propaganda strategy of the Turkestan Islamic Party’s media arm, Islam Awazi, on the surface, deep, and dark web using various open-source intelligence (OSINT) tools, including SpiderFoot. Lastly, LakomyFootnote45 examined the effectiveness of online CVE strategies by mapping propaganda distribution channels of leading militant Islamist extremists using various open-source intelligence techniques and a commercial crawler.

But in light of these successful projects, there are several limitations of collecting data via commercial crawlers and APIs in general. Both, for example, can be costly depending on the complexity and depth of data to be extracted. Most recently, X (formerly Twitter) announced that it will begin charging shockingly high prices for its API access, essentially pricing out researchers.Footnote46 Putting cost aside, chief among the limitations is that online platforms offering APIs or websites generally tend to place restrictions on data collected by outlining a set of rules (in fine print) that if broken are a breach of the site policy. These rules tend to apply to sections of a site that can and cannot be parsed or the amount of content that can be collected each day. This can restrict an individual’s ability to parse relevant information or slow down the data extraction process in general. An additional limitation of these methods is the “black box” problem. In short, commercial crawlers and third-party APIs may not be transparent about possible underlying data extraction strategies, which can be difficult for users to verify or reverse-engineer. To illustrate, Pfeffer et al.Footnote47 found that a random sample provided by the Twitter Sample API was not in fact random which was a result of an undisclosed, underlying sample mechanism. Although the new Academic X/Twitter API has resolved this concern for X/Twitter specifically,Footnote48 the black box problem is likely to persist in other third-party APIs or commercial crawlers because source code is often unavailable for users to check underlying sampling strategies or other operations of the data collected. Researchers should be aware of this concern if they choose to use third-party tools instead of developing their own web-crawlers.

From an ethical perspective, concerns have been raised about researchers “lurking” in terrorist and extremist online spaces for large-scale and, indeed, smaller-scale manual data collection purposes, wherein individuals whose data is being extracted did not give permission or informed consent to do so—an ethical concern outlined in the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) legal framework on the collection, handling, and storage of identifiable personal data. As a result, questions have been raised, primarily from university research ethics committees and boards, about whether researchers ought to obtain consent from the data’s creator and/or whether such content is needed similar to researchers typically expected to obtain consent from human subjects in offline research settings.Footnote49 In response, researchers have mostly turned to the public-private distinction, noting that it is unnecessary to obtain consent without a data creator’s permission if the content they are collecting and analyzing is from an open online setting because it is in the public domain and there is not an expectation of privacy, unlike password-protected or locked online spaces or accounts.Footnote50 Many online terrorism and extremism researchers in particular have also waived informed consent and argued that their data collection practices fall beyond the scope of the GDPR in what Brewer et al.Footnote51 describe as “instances where the anticipated benefits of the research outweigh any potential risks associated with the research… [and can] …produce considerable public benefit by providing crucial information that enhances understandings of the motivations driving certain criminal behaviors”. Nonetheless, as but one precaution to protect sensitive personal data collected, researchers typically take steps to protect subject privacy, such as anonymizing individual outputs and avoiding analysis of identifiable information, both of which also fall beyond the scope of the GDPR.Footnote52

Custom-Written Crawlers

While some online terrorism and extremism researchers have used standard, off-the-shelf web-crawler tools that are readily available online for a fee, it has become more common for researchers to use custom-written computer programs to collect high volumes of information online, oftentimes with widely used programming languages, such as Python, R, JavaScript, Ruby, and PHP.Footnote53 Numerous terrorism and extremism researchers and research centers, networks, labs, and think tanks (among others) have been involved in this growing endeavor in online terrorism and extremism research, including but not limited to the Dark Web Project,Footnote54 the Swedish Defense Research Agency,Footnote55 the VOX-Pol Network of Excellence,Footnote56 the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD),Footnote57 the International Centre for the Study of Radicalization and Political Violence (ICSR),Footnote58 and ourselves at the ICCRC. This popularity is largely the result of custom-written web-crawlers—and web-crawlers in general—being able to collect large volumes of data in a time-efficient manner,Footnote59 which has certainly been beneficial in online terrorism and extremism research. Scholars can upscale data collection and analysis effortsFootnote60 to “keep up” with the evolving nature of terrorists’ and extremists use of the Internet.Footnote61

Having said that, a key methodological limitation of web-crawlers is that it is difficult to guide the process because the crawler does not know what to collect and requires specific parameters for collection.Footnote62 Such a targeted approach, although requiring some front-end work (e.g. setting parameters for data extraction, which is detailed below), is beneficial in collecting information that is relevant and manageable at the analysis phases. Nonetheless, some webmasters have put rate-limiting techniques in place to protect their sites from large-scale web-scraping, which if detected can result in a user or IP address (the one used for data collection) being blocked or blacklisted from the site. Slowing such collection efforts by parsing small quantities of pages per day is one strategy to avoid detection, or by using a virtual private network to rotate an Internet protocol address.Footnote63 Regardless, once the data is collected, the resulting information is often disorganized and requires substantial data cleaning which can be time consuming, or manual programming which requires a level of expertise. Software, which can be expensive, is also needed to format and archive such large volumes of information.Footnote64 These are indeed challenges for most researchers working in the online terrorism and extremism space, as their ability to develop computational tools to collect and then maintain large-scale extremist content online lags parallel fields that collect similar online material.Footnote65 In addition, many web-crawler used in online terrorism and extremism research will not capture image- and video-based content and instead have collected such materials manually, in part because visuals, even if a researcher has them in hand, are more difficult and time-consuming to analyze than text because it should generally be done manually.Footnote66 That many web-crawlers in online terrorism and extremism research will not scrape such content is a key shortcoming because of the increased use of memes and images by terrorists and violent extremists as a means of recruitment, for example.Footnote67

On the other hand, a methodological strength of customized web-crawlers is the ability to collect and then merge disparate data sources to be analyzed as one. Some online terrorism and extremism researchers have taken advantage of this strength to address the growing threat of terrorists and extremists maintaining a presence on multiple online platforms and the need for more comparative research across platforms.Footnote68 As but a few examples, Davey and Ebner at ISDFootnote69 used a web-crawler to extract data from 4chan, 8chan, Voat, Gab, and Discord to then explore the ideological nexus and convergence of the “new” extreme right in Europe and the United States (U.S.). Scrivens et al. at the ICCRC used a customized web-crawler to collect content from RWE forums Iron March and Fascist Forge to quantify the existence of extremist ideologies, personal grievances, and violent extremist mobilization effortsFootnote70 as well as developmental posting behaviors found in the forums.Footnote71 Mehran et al.Footnote72 at VOX-Pol parsed data from RWE websites and jihadi magazines for a comparative analysis of linguistic patterns. Lastly, Davies et al.Footnote73 at the ICCRC extracted data from popular far-right, left-wing, jihadist, and incel discussion forums to examine the effect of COVID-19 on posting behavior.

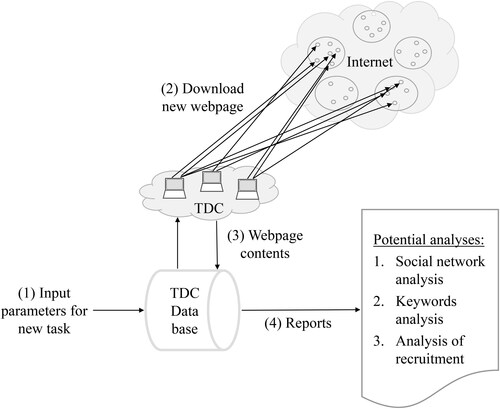

Another notable strength of customized web-crawlers is the ability to develop filtering tools to extract specific information of interest from online content (e.g. text, images, and video). The Dark Crawler (TDC),Footnote74 established at the ICCRC, is a useful example of a customized web-crawler for online terrorism and extremism research. TDC browses the Internet similar to other web-crawlers, but since it is a custom-written computer-program, it is much more flexible than the previously discussed web-crawling process. In particular, TDC is capable of seeking out extremist content online, among other types of content, based on user-defined keywords and other parameters (discussed below). As TDC visits each page, it captures all content on that page for later analysis—and while simultaneously collecting information about the content and making decisions about whether the page includes extremist content. The idea of this approach is based on a combination of research conducted with the Dark Web Project at the University of ArizonaFootnote75 and a project at the ICCRC that identified and examined online child exploitation websites.Footnote76 TDC has since demonstrated its benefit in collecting and investigating deviant and criminal online networks and communities in generalFootnote77 and terrorist and extremist content online in particular.Footnote78

TDC is a four step system that can be distributed across multiple virtual machines, depending on the number of machines available. The first of four steps, as expressed in , is to define a task along with its parameters. TDC can handle multiple tasks simultaneously, each of which is given a priority specified by the end-user. The priority of each task is determined by the number of machines allocated to it. For example, if tasks I, II, and III are given priority 50, 80, and 70, respectively, then task I will receive 25% of the available resources (50/(50 + 80 + 70) = 0.25 = 25%). If more machines are added to TDC, then the absolute number of resources available for each task will increase but the relative number of resources available for each task will remain the same.

Each task consists of four parameters to prevent it from perpetually crawling the Internet and wandering into websites and webpages unrelated to extremism.

Number of webpages: for practical purposes, since the number of webpages on the Internet is infinite, restrictions must be placed on the number of webpages that are retrieved by the web-crawler. Theoretically, any web-crawler could crawl for a long time and store the entire collection of webpages on the Internet. For our purposes at the ICCRC, however, this is unlikely for several reasons. First, the amount of storage that would be required to warehouse the extracted data is beyond the scope of any sensible research project. Second, webpages are created at a much higher rate than what can be extracted with TDC or web-crawlers generally. Lastly, a copy of the “full Internet” is not required to draw meaningful conclusions about a particular topic under investigation; extracting large-scale, representative samples, is more than adequate.

Number of domains: the number of Internet domains that TDC will collect data on can be specified. When limiting a crawl to n pages, the crawler will attempt to distribute the sampling equally across all websites that it has encountered, meaning that TDC will sample similar numbers of pages from each of the sites it visits. As a result, at the end of the task, if w websites are sampled, all sites will have approximately the same number of pages retrieved (=n/w) and analyzed.

Trusted domains: a set of trusted domains can then be specified by the end-user, which tells the crawler that all content on those domains should not be extracted. As an example, it can be assumed, with a high level of certainty, that a website, such as www.microsoft.com does not include or is linking to any extremist material. As a result, TDC is trained to assume that the website does not contain extremist content, and as such, it would not retrieve any pages from that site. Without having this mechanism in place, TDC could wander into a search engine, directing it completely off topic and making the resulting extracted network irrelevant to the specified topic and task.

Keywords: the purpose of TDC is to find, analyze, and map out the websites and webpages that include extremist content. To achieve this, TDC recursively retrieves all webpages that are linked from the webpage it is currently reviewing. However, since extremist content consists of a very small subset of all the content on the Internet,Footnote79 it would be expected that unconstrained, TDC would very quickly start to retrieve webpages that are completely unrelated to extremism. As a result, some mechanism must be built into TDC that controls which webpages it uses in its exploration process. This is done through the use of keywords, which are user-specified words that have been found to be indicative of extremist contentFootnote80 and thus indicate to TDC that the pages being retrieved are on-topic. Within the online terrorism and extremist domain, such keywords could include gun, weapon, or terror. But to make this mechanism more robust, a word counter can be included in TDC, which indicates a minimum threshold on the number of keywords that must exist on a page before the TDC considers it on topic.Footnote81

Once a task has been decided, each webpage is downloaded by TDC (—Step 2). If the downloaded page meets the parameters laid out above, then the page is considered “on topic”, all page content is saved, and all page links are followed out of it recursively (Step 3). The webpage contents are then stored in the database, and various reports and analyses can be performed (Step 4).

Manual Techniques for Data Collection

Although automated and semi-automated data collection tools have gained considerable traction in online terrorism and extremism research in recent years,Footnote82 manual extraction of open-source data has also been a commonly used technique for data collection.Footnote83 Computational techniques are certainly more efficient than manual techniques for data collection, as expressed in , but the latter allows researchers to capture more nuance and context in the data as well as improve its validity via manual extraction—especially with more latent issues or multiple variables or constructs requiring analysis (discussed further below). For instance, researchers from The American School Shooting StudyFootnote84 used manual techniques to identify and compile open-source documents on school shooting incidents and offenders in the U.S. These researchers manually flagged relevant information that was only mentioned in passing but which engaged important facts. The researchers then manually target searched and tracked down this information. Examples include: national stories noting in one sentence a key article in a local newspaper that the researchers then manually located; and a single reference by one national outlet to a radio interview with an important participant that researchers then manually searched and obtained its transcript. In both examples, the tracked down information included rich details about the incident and offender that were used to fill in a series of missing values. In these cases, the researchers thought like a private investigator and were intimately and thoroughly familiar with their search files’ content, which was a time-consuming process.

Table 1. Strengths and limitations of data collection methods in online terrorism and extremism research.

Traditionally, manual extraction in online terrorism and extremism research has consisted of data collection and analyses of terrorist and extremist websites and forumsFootnote85 wherein researchers manually visit a website, read each page within it, and develop a way to code, analyze, and summarize the content.Footnote86 Some recent examples of this approach include Holt et al.Footnote87 who manually collected online materials from several RWE forums to examine the breadth of extremist ideologies expressed across the platforms. Stall et al.,Footnote88 in combination with automated scraping, manually collected memes from several U.S.-based far-right online spaces, including a popular militia recruitment forum, to assess the right-wing meme ecosystem online. Some researchers have also manually extracted materials from open-source social media accounts, including Conway et al.Footnote89 who combined manual and semi-automated approaches to collect pro-jihadi accounts on Twitter for the purposes of examining the Syrian jihadi online ecology.

But far more common in the online terrorism and extremism literature is for researchers to create databases by manually collecting and triangulating open-source information from various online sources, including media reports, court documents, terrorism databases, and social media accounts. The development of these databases has provided researchers, practitioners, and policymakers with unprecedented opportunity and ability to address previously unexplored questions as well as assess and re-evaluate old questions with new resources and new research methods. Recent examples of such an initiative include Gill et al. who developed several terrorist offender databases to explore the on- and offline behavioral underpinnings of a lone-actor terrorists within the U.S. and EuropeFootnote90 as well as United Kingdom (U.K.)-based terrorists.Footnote91 Lee et al.Footnote92 constructed the “Global Cyberterrorism Dataset” for the purpose of mapping the global cyberterror networks of terrorist groups Al-Qaeda and IS. Whittaker created a database of known terrorists acting on behalf of IS within the U.S. to examine their online behaviorsFootnote93 and use of financial technologies in terrorist plots.Footnote94 Another notable example of a research project that used manual extraction procedures is the development of the ECCD.Footnote95

Extremist Cyber Crime Database

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Center of Excellence, the National Counterterrorism Innovation, Technology, and Education Center (NCITE), supported the creation of the ECCD. The ECCDFootnote96 was developed to fill a research gap and systematically track ideologically motivated cyberattacks against online critical infrastructure that supports commerce, communications, and functionality of the Internet. Such attacks are now a major concern among Western law enforcement agencies and policy-making bodies, as the Internet affords more than just communications capabilities—virtually all aspects of finance, power, water, and sewer grid management, as well as government and military operations, depend on the Internet to function. These resources are susceptible to compromise through various attack techniques, creating a profound threat to both the physical and cybersecurity posture of governments, industry, and civilians alike.Footnote97 Few studies have explored the ways that cyberspace has become a medium for attacks against the online infrastructure that supports commerce and communications between citizens, industry, and government.Footnote98 Such efforts are facilitated via computer hacking whereby individuals manipulate vulnerabilities in computer hardware and software to gain access to sensitive networks and data.Footnote99 Specifically, there is a lack of reporting on cyberattacks from both official data sources and general population surveys.Footnote100 Further, most broader terrorism databases, such as the Global Terrorism Database (GTD),Footnote101 use definitions that require violence, thus systematically excluding many cybercrimes.

The ECCD was created using manual extraction procedures to better understand how different ideological movements operate in online spaces and the extent to which trends in online operations reflect offline activities. Four inclusion criteria guided which attacks were included in the database: first, the attack must have occurred between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2018. Second, the attack must have targeted U.S infrastructure or target(s); the server targeted must be registered on U.S. soil. Third, if the perpetrator of the attack is a non-state actor, the attack must have been perpetrated for a specific ideological cause. The database focuses on the following ideologies: far-right extremism, jihadism, environmental/animal rights extremism, left-wing adherents, and single-issue/secular extremism or the actor may be state-affiliated, including both formal or informal ties to a national government, intelligence agency, or military unit. The attribution may be made by a cybersecurity company or government agency. Fourth, at least one of the following attack methods must have been used: data breach, DDoS, web defacement, doxing, and some other attack methods (i.e. email spamming, hacking of social media, or strobing GIF spamming). The creation of this database is similar to other manual extraction procedures to study terrorism (i.e. the U.S. Extremist Crime Database),Footnote102 school shootings (i.e. the American School Shooting Study),Footnote103 and hate crimes (i.e. the Bias Homicide Database).Footnote104

There are several important steps occurring in the building of the database. First, to capture the pertinent facts and elements about each attack, a rigorous Internet search and information procurement process is necessary. The identification of incidents and information about the incidents occurred by mining information from more than 120 separate sources to create a listing of all known attacks meeting the inclusion criteria. Some examples of sources include existing databases, chronologies and listings, official records, law enforcement reports, scholarly works, newspaper accounts/listings, other media’s listings, online encyclopedias, blogs, and watch-groups/advocacy reports. In addition, the Internet was searched, using major search engines like Google, Bing, and Yahoo, and leading newspapers like the New York Times, to locate relevant events. In addition, an exhaustive list of cybersecurity and hacker-related reporting portals was developed to identify additional information on these incidents.

Second, information from these sources were extracted and then organized into a detailed qualitative record pertaining to each attack and individuals involved in an attack. The goal of the manual search was to unearth every conceivable piece of open-source material about each participant. The source materials included media accounts, police and government documents, court records, and other materials. This information was stored chronologically within a Microsoft Word file, referred to as a “master file”. Studies show that using vast arrays of sources like this can reduce bias toward newsworthy incidents,Footnote105 as the data are gathered from local agencies and social media systematically, and this increases the likelihood of gathering details about various types of participants. Additionally, the integration of background checks and similar services can uncover useful data about personal lives and histories.Footnote106 Finally, information from social media platforms is used to do targeted searches for additional information.

Third, researchers reviewed the extracted information, or the “case file”, to identify the event and perpetrator characteristics they are interested in. To help ensure uniformity and accuracy of the coding, coders drew upon a standardized coding instrument and underwent a period of probationary training. For example, the codebook for the ECCD includes demographic characteristics, criminal history, drug and alcohol use, major educational and life events, manifestations of psychological conditions, peer and family social networks, influential relationships, civic engagement, and geographic attributes.

Indeed, manual techniques of data collection are used when the relevance and quality of information being extracted are most important.Footnote107 Yet researchers who are manually collecting data in general or developing databases, in particular, face several challenges. For example, both are labor-intensive and time-consuming. To illustrate, the use of multiple research assistants (RAs) to search and code cases highlights reliability concerns. Scholars must draft and employ protocols to minimize human searching and coding errors. The ECCD conducts systematic RA searcher trainings, for example, to ensure uniformity and reliability across searchers and research sites. Importantly, ECCD protocols mandate that searchers include every single piece of information, even tangential and repeat information they come across. The ECCD creators noted that as case investigations and court proceedings unfold new information that becomes available not only fills in “missing” values but corrects/updates previously coded values. The ECCD also devised protocols to address discrepancies, such as giving greater weight to the more “trusted” sources following prior research that ranked source types by their reliability (e.g. court document vs. anonymous blog). When media accounts were not consistent, the database privileged known outlets and recognized established local outlets over other media reports.

Another concern is the amount and type of information available about different types of events. Some events are high profile and of great media interest, and the level of social media engagement by perpetrators varies considerably. The ECCD thus documents the number and type of documents for each event, and there is an established system of reliability and validity testing, measured by the number and types of documents about each individual case (e.g. XX police documents, XX media accounts, XX court records, etc.) as well as the source for coded values (e.g. an offender self-admission, police statements, peer quotes, etc.). Finally, missing data is another common challenge that open-source studies generally and those creating databases via manual collection procedures particularly must address. Although there are various strategies to deal with missing data problems (e.g. imputation), it is also important to invest considerable human capital in expanding the search for information by doing targeted searches and occasionally purchasing access to public data aggregators, which may be time-consuming and costly.

This type of data collection strategy also engages a variety of ethical concerns. First, university research ethics committees and boards raise questions about the type of human subject review (i.e. full review, expedited, non-human subjects) that such projects require. On the one hand, these studies only collect publicly available information. Since the information is public and is available to all, there are no privacy expectations, no harm is caused from the data collection and thus the research is non-human subjects. On the other hand, the researchers are collecting/collating/combining/reorganizing much information from a variety of sources and then systematically coding that information in a single location, which poses some risk to the individuals identified. Further, there are different levels of publicly available information. Using Google, for example, to identify information that is then downloaded is more accessible compared to a scenario where the researcher must create an account and password on a site before accessing it and gaining access to the information for downloading. Indeed, the latter scenario might subject the project to a higher level of research ethics committees and board review. Second, since open-source databases are publicly available, it is important that they only include accurate information. This, of course, is a challenge since multiple sources may contain conflicting information, discrepancies, and/or inaccuracies. The researchers must devise protocols to manage conflicting accounts, as well as assess the quality of the source, and the information it contains so that users know how credible the coded values are. One important criterion for inclusion is criminal justice system involvement, such as conviction. This ensures that individuals who were never arrested or were tried but acquitted are not included in the study and thus protects their integrity.

It is also worth highlighting that the ECCD was constructed similarly to other terrorism databases that use open-source data collection strategies, such as the Extremist Crime Database (ECDB), the GTD, and Profiles of Individual Radicalization in the United States (PIRUS). Although the analysis of data from these databases have contributed significantly to the growth of empirical research published on terrorism and violent extremism, there are some additional limitations that should be noted. First, there are no specific universal protocols that all databases follow, so it is difficult to compare findings across studies. Second, researchers must be transparent about their database’s inclusion/exclusion criteria, as well as their search and source protocols, and managing conflicting variable values across source types. Unfortunately, many databases do not engage these issues and it is therefore difficult to determine why there are discrepancies in results. For example, some open-source databases use a finite number of sources to determine variable coding while others collect all available public information.

Third, there are other types of obstacles in terms of having sufficient information and variation in information available about events. One of the primary sources of information used in open-source databases are media accounts, but such accounts prioritize certain incidents (e.g. the more serious the incident, the more media articles are produced), certain interpretation of the incidents (e.g. government and law enforcement sources have a heavier presence in these stories are thus given the opportunity to emphasize some aspects of the story and downplay other aspects), and certain locations (e.g. media processes vary considerable by country). Relatedly, some studies only collect media accounts, others also include court documents, while others are even more expansive, including social media after action reports, and other sources.

Finally, there are increasing ethical concerns about the collection of such data as the boundaries of what is publicly available have become increasingly blurry. There is more information available and there are an increasing number of companies that aggregate information, including criminal record data, and there are debates about standards for the treatment of human subjects in studies that use open source. In general, if researchers (1) only use information that is available to all, either free or incur a minimal charge, and (2) do not interact with offenders or other individuals (e.g. by only focusing on event characteristics, and not emailing or contacting subjects—such as liking posts or friend requests—via social media), they do not implicate issues for university research ethics committees and boards since there is no engagement with human subjects.

Future Directions

It is increasingly common for online terrorism and extremism researchers to draw from and/or develop a variety of data collection techniques to conduct their research. Again, each of these different techniques has their strengths, limitations, and ethical concerns. Customized web-crawlers are the most common method of collecting open-source online extremist data, followed by the manual creation of databases, with researchers generally arguing that large-scale collection is impracticable via a manual approach—hence why most have turned to computers for data mining.Footnote108 Regardless of data collection preference, we propose several suggestions for improving online terrorism and extremism data collection efforts based on the methods examined in this article.

First, combining data extraction techniques in online terrorism and extremism research, such as blending manual and automated data extraction techniquesFootnote109 or linking commercial crawlers with other data extraction tools,Footnote110 will advance research in this space. These combinations, although relatively rare in the online terrorism and extremism literature, have shown signs of success, in part because a technical background is not required for data collection, and because researchers can draw from the abovementioned strengths of each extraction technique. Combining techniques will also help researchers better understand what is captured and what is missing using different strategies and identify areas where adjustments in the process should be made. In addition, combining techniques may be helpful in addressing some of the more challenging aspects of data collection in contemporary online terrorism and extremism research, such as identifying and then collecting image and video-based content from online sharing apps, such as Instagram and TikTok or from encrypted communication apps, such as Telegram and Signal, or even from gaming platforms, such as Steam and Twitch. Here, violent extremist content, users, or networks of interest could be manually identified from these platforms, and then the data extracted using computational techniques.

Second, future data collection efforts would benefit from the integration of traditional methods (e.g. in-depth interviews or surveys) with computational methods to address key research questions with policy implications. Scrivens et al., for example, used a customized web-crawler to extract online content from a sample of violent and non-violent RWEs who were identified by a former violent extremist during an in-depth interview. Here the researchers were in a unique position to identify which online users engaged in violent extremism offline to explore an array of their online behaviors compared to their non-violent counterpart.Footnote111 Such an open-source dataset containing users’ offline violent behavior is indeed rare in online terrorism and extremism research, as most drawing from open-source data simply do not have access to ground truth. This is a main limitation of open-source data generally, and not only in terrorism and extremism research, because developing a high level of confidence in the accuracy of second-hand information is challenging without first-hand collection of such data.Footnote112

Third, researchers must make archives of the extremist online content accessible to other researchers. Access to data in online terrorism and extremism research remains a challenge for many in the field, especially junior and early career scholars who may not have the resources or skillsets. This is despite the various calls from researchersFootnote113 to make such content more widely available for research purposes. Surprisingly, to date, only a small number of individuals have contributed to this initiative. The Dark Web Project, for example, collected and made available the content of 28 jihadi forums comprising over 13 million messages.Footnote114 TDC database includes, but is not limited to, over 11 million posts from the most conspicuous RWE forum, Stormfront; over 8 million posts that include Islamist content; as well as over 49 million posts drawn from 11 RWE subreddits. All are available to users for research upon request.Footnote115 Not only are these exceptional databases few and far between,Footnote116 these two resources have not been widely used by researchers, perhaps because they are less known compared to widely used databases, such as the GTD. Regardless, providing researchers with access to non-traditional data sources, especially open-source intelligence and social media data, will undoubtedly transform the future understanding of violent extremism and terrorism in generalFootnote117 and online terrorism and extremism in particular.Footnote118

Lastly, in addition to collecting and then sharing open-source data among key stakeholders generally, those working in online terrorism and extremism research should triangulate data across databases and datasets. Taking a lead in this respect are, for example, Holt, Freilich, Chermak, and LaFree,Footnote119 who triangulated data between the ECDB and the PIRUS databases, testing whether various criminological theories account for on- and offline pathways to hate and extremist violence. This provided multiple observational points to explore the similarities and differences across offenders’ background, attitudes, and behavior. Perhaps equally valuable would be for researchers to merge such databases with databases that include extremist online content, such as the abovementioned Dark Web Project and TDC database, and develop a central database in which various online platforms that violent extremists and terrorists have been known to frequent can be made available in one space. This would place researchers in a better position to explore key questions in online terrorism and extremism research, such as whether consumption of violent extremist online content leads directly to violent acts occurring that would not have occurred if the Internet did not exist.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See Maura Conway, “Determining the Role of the Internet in Violent Extremism and Terrorism: Six Suggestions for Progressing Research,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 40, no. 1 (2017): 77–98; see also Ryan Scrivens, Paul Gill, and Maura Conway, “The Role of the Internet in Facilitating Violent Extremism and Terrorism: Suggestions for Progressing Research,” in The Palgrave Handbook of International Cybercrime and Cyberdeviance, eds. Thomas J. Holt and Adam Bossler (London: Palgrave, 2020), 1–22.

2 Andrew Barr and Alexandra Herfroy-Mischler, “ISIL’s Execution Videos: Audience Segmentation and Terrorist Communication in the Digital Age,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 41, no. 12 (2018): 946–67.

3 Joel Finkelstein, Alex Goldenberg, Sean Stevens, Pamela Paresky, Lee Jussim, John Farmer, and John K. Donohue, Network-Enabled Anarchy: How Militant Anarcho-Socialist Networks Use Social Media to Instigate Widespread Violence Against Political Opponents and Law Enforcement (Princeton, NJ: Network Contagion Research Institute, 2020).

4 Brian Hughes and Cythia Miller-Idriss, “Uniting for Total Collapse: The January 6 Boost to Accelerationism,” CTC Sentinel 14, no. 4 (2021): 12–8.

5 See Conway, “Determining the Role of the Internet;” see also Scrivens et al., “The Role of the Internet.”

6 Megha Chaudhary, and Divya Bansal, “Open Source Intelligence Extraction for Terrorism-Related Information: A Review,” WIREs Data Mining Knowledge Discovery 12, no. 5 (2022): 1–35.

7 William S. Parkin and Jeff Gruenewald, “Open-Source Data and the Study of Homicide,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 32, no. 18 (2017): 2693–723.

8 Gary A. Ackerman and Lauren E. Pinson, “Speaking Truth to Sources: Introducing a Method for the Quantitative Evaluation of Open Sources in Event Data,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 39, no. 7–8 (2016): 617–40; Laura Dugan and Michael Distler, “Measuring Terrorism,” in Handbook on the Criminology of Terrorism, eds. Gary LaFree and Joshua D. Freilich (West Sussex: Wiley Press, 2016), 189–205; James Lynch, “Not Even Our Own Facts: Criminology in the Era of Big Data,” Criminology 56, no. 3 (2018): 437–54; Parkin and Gruenewald, “Open-Source Data.”

9 Parkin and Gruenewald, “Open-Source Data.”

10 Lin Huff-Corzine and Jay Corzine, “The Devil’s in the Details: Measuring Mass Violence,” Criminology and Public Policy 19, no. 1 (2020): 317–33; Christopher S. Koper, “Assessing the Potential to Reduce Deaths and Injuries from Mass Shootings Through Restrictions on Assault Weapons and Other High-Capacity Semiautomatic Firearms,” Criminology and Public Policy 19, no. 1 (2020): 147–70; Adam Lankford and James Silver, “Why Have Public Mass Shootings Become More Deadly? Assessing How Perpetrators’ Motives and Methods Have Changed Over Time,” Criminology and Public Policy 19, no. 1 (2020): 37–60; April M. Zeoli and Jennifer K. Paruk, “Potential to Prevent Mass Shootings Through Domestic Violence Firearm Restrictions,” Criminology and Public Policy 19, no. 1 (2020): 129–45.

11 Kayla Allison and Brent R. Klein, “Pursuing Hegemonic Masculinity Through Violence: An Examination of Anti-Homeless Bias Homicides,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36, no. 13–14 (2021): 6859–82; Jeff Gruenewald, “Using Open-Source Data to Study Bias Homicide Against Homeless Persons,” International Journal of Criminology and Sociology 2 (2013): 538–49.

12 Darrell J. Steffensmeier, Jennifer Schwartz, and Michael Roche, “Gender and Twenty-First-Century Corporate Crime: Female Involvement and the Gender Gap in Enron-Era Corporate Frauds,” American Sociological Review 78, no. 3 (2013): 448–76.

13 Steven M. Chermak and Jeffrey Gruenewald, “The Media’s Coverage of Domestic Terrorism,” Justice Quarterly 23, no. 4 (2006): 428–61; Steven M. Chermak, Joshua D. Freilich, William S. Parkin, and James P. Lynch, “American Terrorism and Extremist Crime Data Sources and Selectivity Bias: An Investigation Focusing on Homicide Events Committed by Far-Right Extremists,” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 28, no. 1 (2012): 191–218; William S. Parkin, Joshua D. Freilich, and Steven M. Chermak, “Ideological Victimization: Homicides Perpetrated by Far-Right Extremists,” Homicide Studies 19, no. 3 (2015): 211–36.

14 Gruenewald, “Using Open-Source Data;” Parkin and Gruenewald, “Open-Source Data.”

15 Lynch, “Not Even Our Own Facts.”

16 See note 9 above.

17 Conway, “Determining the Role of the Internet;” Maura Conway, “Online Extremism and Terrorism Research Ethics: Researcher Safety, Informed Consent, and the Need for Tailored Guidelines,” Terrorism and Political Violence 33, no 2 (2021): 367–80.

18 Gary LaFree and Joshua D. Freilich, eds., The Handbook of the Criminology of Terrorism (West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 2016).

19 The ICCRC is situated in Simon Fraser University’s School of Criminology and is affiliated with Michigan State University’s School of Criminal Justice and the John Jay College of Criminal Justice at the City University of New York, among other academic institutes. For more on the ICCRC, see https://www.sfu.ca/iccrc.html.

20 Thomas J. Holt, Steven M. Chermak, Joshua D. Freilich, Noah Turner, and Emily Greene-Colozzi, “Introducing and Exploring the Extremist Cybercrime Database (ECCD),” Crime & Delinquency. Ahead of Print (2022).

21 Martin Bouchard, Kila Joffres, and Richard Frank, “Preliminary Analytical Considerations in Designing a Terrorism and Extremism Online Network Extractor,” in Computational Models of Complex Systems, eds. Vijay K. Mago and Vahid Dabbaghian (New York, NY: Springer, 2014), 171–84; Garth Davies, Martin Bouchard, Edith Wu, Kila Joffres, and Richard Frank, “Terrorist and Extremist Organizations’ Use of the Internet for Recruitment,” in Social Networks, Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism: Radical and Connected, ed. Martin Bouchard (New York, NY: Routledge, 2015), 105–27; Richard Frank, Martin Bouchard, Garth Davies, and Joseph Mei, “Spreading the Message Digitally: A Look Into Extremist Content on the Internet,” in Cybercrime Risks and Responses, eds. Russell G. Smith, Ray C.-C. Cheung, and Laurie Y.-C. Lau (London: Palgrave, 2015), 130–45; Ryan Scrivens, Tiana Gaudette, Garth Davies, and Richard Frank, “Searching for Extremist Content Online Using The Dark Crawler and Sentiment Analysis,” in Methods of Criminology and Criminal Justice Research, eds. Mathieu Deflem and Derek M. D. Silva (Bingley: Emerald Publishing, 2019), 179–94; Matthew L. Williams and Pete Burnap, “Cyberhate on Social Media in the Aftermath of Woolwich: A Case Study in Computational Criminology and Big Data,” British Journal of Criminology 56, no. 2 (2015): 211–38.

22 Internet World Stats, “Internet Growth Statistics,” https://www.internetworldstats.com/emarketing.htm (accessed September 16, 2022).

23 Ryan Scrivens, Garth Davies, and Richard Frank, “Searching for Signs of Extremism on the Web: An Introduction to Sentiment-based Identification of Radical Authors,” Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 10, no. 1 (2018): 39–59.

24 Katie Cohen, Fredik Johansson, Lisa Kaati, and Jonas C. Mork, “Detecting Linguistic Markers for Radical Violence in Social Media,” Terrorism and Political Violence 26, no. 1 (2014): 246–56.

25 Cohen et al., “Detecting Linguistic Markers;” Scrivens et al., “Searching for Extremist Content Online.”

26 Min Chen, Shiwen Mao, Yin Zhang, and Victor C. M. Leung, Big Data: Related Technologies, Challenges and Future Prospects (New York, NY: Springer, 2014); Conway, “Determining the Role of the Internet;” Marc Sageman, “The Stagnation in Terrorism Research,” Terrorism and Political Violence 26, no. 4 (2014): 565–80.

27 Ryan Scrivens, “Exploring Radical Right-Wing Posting Behaviors Online,” Deviant Behavior 42, no. 11 (2021): 1470–84.

28 Benjamin W. K. Hung, Anura P. Jayasumana, and Vidarshana W. Bandara, “Detecting Radicalization Trajectories Using Graph Pattern Matching Algorithms,” in Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI), Tucson, AZ, USA, 313–5.

29 Fredrik Johansson, Lisa Kaati, and Magnus Sahlgren, “Detecting Linguistic Markers,” in Combating Violent Extremism and Radicalization in the Digital Era, eds. Majeed Khader, Loo Seng Neo, Gabriel Ong, Eunine Tan Mingyi, and Jeffery Chin (Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference, 2016), 374–90.

30 Conway, “Determining the Role of the Internet;” Frank et al., “Spreading the Message Digitally;” Scrivens et al., “Searching for Extremist Content Online.”

31 See Chen et al., Big Data.

32 Ahmed Abbasi and Hsinchun Chen, “Applying Authorship Analysis to Extremist-Group Web Forum Messages,” Intelligent Systems 20, no. 5 (2005): 67–75; Bouchard et al., “Preliminary Analytical Considerations;” Hsinchun Chen, Dark Web: Exploring and Data Mining the Dark Side of the Web (New York, NY: Springer, 2012); Cohen et al., “Detecting Linguistic Markers;” Frank et al., “Spreading the Message Digitally.”

33 Mike Thelwall, “A Web Crawler Design for Data Mining,” Journal of Information Science 27, no. 5 (2001): 319–25.

34 For more on web-crawlers generally, see Thelwall, “A Web Crawler Design for Data Mining”.

35 Ryan Scrivens and Maura Conway, “The Roles of ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Media Tools and Technologies in the Facilitation of Violent Extremism and Terrorism,” in The Human Factor of Cybercrime, eds. Rutger Leukfeldt and Thomas. J. Holt (New York, NY: Routledge, 2019), 286–309.

36 Behsaad Ramez, “Social Network APIs: The Internet’s Portal to the Real World,” Toptal, 2022. https://www.toptal.com/api-developers/social-network-apis (accessed October 12, 2022).

37 J. M. Berger and Bill Strathearn, Who Matters Online: Measuring Influence, Evaluating Content and Countering Violent Extremism in Online Social Networks (London: International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence, 2013).

38 Ryan Scrivens and Amarnath Amarasingam, “Haters Gonna ‘Like’: Exploring Canadian Far-Right Extremism on Facebook,” in Digital Extremisms: Readings in Violence, Radicalisation and Extremism in the Online Space, eds. Mark Littler and Benjamin Lee (London: Palgrave, 2020), 63–89.

39 Jade Hutchinson, Amarnath Amarasingam, Ryan Scrivens, and Brian Ballsun-Stanton, “Mobilizing Extremism Online: Comparing Australian and Canadian Right-Wing Extremist Groups on Facebook,” Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression. Ahead of Print (2021).

40 Hampton Stall, David Foran, and Hari Prasad, “Kyle Rittenhouse and the Shared Meme Networks of the Armed American Far-Right: An Analysis of the Content Creation Formula, Right-Wing Injection of Politics, and Normalization of Violence,” Terrorism and Political Violence. Ahead of Print (2022).

41 Emma F. Thomas, Nathan Leggett, David Kernot, Lewis Mitchell, Saranzaya Magsarjav, and Nathan Weber, “Reclaim the Beach: How Offline Events Shape Online Interactions and Networks Amongst Those Who Support and Oppose Right-Wing Protest,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Ahead of Print (2022).

42 Chaudhary and Bansal, “Open Source Intelligence Extraction.”

43 Miron Lakomy, “Crouching Shahid, Hidden Jihad: Mapping the Online Propaganda Campaign of the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham-affiliated Ebaa News Agency,” Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression. Ahead of Print (2021).

44 Miron Lakomy, “Listening to the “Voice of Islam”: The Turkestan Islamic Party’s Online Propaganda Strategy,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Ahead of Print (2021).

45 Miron Lakomy, “Why Do Online Countering Violent Extremism Strategies Not Work? The Case of Digital Jihad,” Terrorism and Political Violence. Ahead of Print (2022).

46 See Chris Stokel-Walker, “Twitter’s $42,000-per-Month API Prices Out Nearly Everyone,” Wired, March 10, 2023. https://www.wired.com/story/twitter-data-api-prices-out-nearly-everyone (accessed March 23, 2023).

47 Jürgen Pfeffer, Katja Mayer, and Fred Morstatter, “Tampering with Twitter’s Sample API,” EPJ Data Science 7, no. 1 (2018): 1–21.

48 See Jürgen Pfeffer, Angelina Mooseder, Jana Lasser, Luca Hammer, Oliver Stritzel, and David Garcia, “This Sample Seems to be Good Enough! Assessing Coverage and Temporal Reliability of Twitter’s Academic API.” arXiv:2204.02290 [cs.SI].

49 Stephane J. Baele, David Lewis, Anke Hoeffler, Oliver C. Sterck, and Thibaut Slingeneyer, “The Ethics of Security Research: An Ethics Framework for Contemporary Security Studies,” International Studies Perspectives 19, no. 2 (2018): 105–27; Conway, “Online Extremism and Terrorism Research Ethics.”

50 See Annette Markham and Elizabeth Buchanan, Ethical Decision-Making and Internet Research, Version 2.0 (AoIR, 2012); see also David Décary-Hétu and Judith Aldridge, “Sifting Through the Net: Monitoring of Online Offenders by Researchers,” The European Review of Organised Crime 2, no. 2 (2015): 122–41.

51 Russel Brewer, Bryce Westlake, Tahlia Hart, and Omar Arauza, “The Ethics of Web Crawling and Web Scraping in Criminological Research: Navigating Issues of Consent, Privacy and Other Potential Harms Associated with Automated Data Collection,” in Researching Cybercrimes: Methodologies, Ethics, and Critical Approach, eds. Anita Lavorgna and Thomas J. Holt (Cham: Palgrave, 2021), 441.

52 Ibid.

53 Chaudhary and Bansal, “Open Source Intelligence Extraction.”

54 For more on the Dark Web Project, see https://eller.arizona.edu/departments-research/centers-labs/artificial-intelligence/research/previous/dark-web-geo-web.

55 For more on the agency, see https://www.foi.se/en/foi.html.

56 For more on VOX-Pol, see https://www.voxpol.eu.

57 For more on ISD, see https://www.isdglobal.org/research-analysis/data-sets-and-research-methods/.

58 For more on ICSR, see https://icsr.info.

59 Thelwall, “A Web Crawler Design for Data Mining.”

60 Conway, “Determining the Role of the Internet.”

61 Scrivens and Conway, “The Roles of ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Media Tools.”

62 Filippo Menczer, Gautham Pant, and Padmini Srinivasan, “Topical Web Crawlers: Evaluating Adaptive Algorithms,” ACM Transactions on Internet Technology 4, no. 4 (2004): 378–419.

63 Adelina Kiskyte, “13 Tips on How to Crawl a Website Without Getting Blocked,” Oxylabs.io, September 16, 2021. https://oxylabs.io/blog/how-to-crawl-a-website-without-getting-blocked (accessed October 12, 2022).

64 Thelwall, “A Web Crawler Design for Data Mining.”.

65 See note 60 above.

66 A notable and recent exception to this is Kay L. O’Halloran, Sabine Tan, Peter Wignell, John A. Bateman, Duc-Son Pham, Michele Grossman, and Andrew Vande Moere, “Interpreting Text and Image Relations in Violent Extremist Discourse: A Mixed Methods Approach for Big Data Analytics”, Terrorism and Political Violence 31, no. 3 (2019): 454–74.

67 See Maura Conway, Ryan Scrivens, and Logan Macnair, “Right-Wing Extremists’ Persistent Online Presence: History and Contemporary Trends,” The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague 10 (2019): 1–24.

68 See note 60 above.

69 Jacob Davey and Julia Ebner, The Fringe Insurgency: Connectivity, Convergence and Mainstreaming of the Extreme Right (London: Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 2017).

70 Ryan Scrivens, Amanda Isabel Osuna, Steven M. Chermak, Michael A. Whitney, and Richard Frank, “Examining Online Indicators of Extremism in Violent Right-Wing Extremist Forums,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Ahead of Print (2021).

71 Ryan Scrivens, Thomas W. Wojciechowski, and Richard Frank, “Examining the Developmental Pathways of Online Posting Behavior in Violent Right-Wing Extremist Forums,” Terrorism and Political Violence. Ahead of Print (2020).

72 Weeda Mehran, Stephen Herron, Ben Miller, Anthony F. Lemieux, and Maura Conway, “Two Sides of the Same Coin? A Largescale Comparative Analysis of Extreme Right and Jihadi Online Text(s),” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Ahead of Print (2022).

73 Garth Davies, Edith Wu, and Richard Frank, “A Witch’s Brew of Grievances: The Potential Effects of COVID-19 on Radicalization to Violent Extremism,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Ahead of Print (2021).

74 See https://www.thedarkcrawler.com.

75 See Chen, Dark Web.

76 Richard Frank, Bryce G. Westlake, and Martin Bouchard, “The Structure and Content of Online Child Exploitation Networks,” in Proceedings of the 2010 ACM SIGKDD Workshop on Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI-KDD), Washington, DC, USA; Bryce G. Westlake and Martin Bouchard, “Criminal Careers in Cyberspace: Examining Website Failure Within Child Exploitation Networks,” Justice Quarterly 33, no. 7 (2015): 1154–81; Bryce G. Westlake, Martin Bouchard, and Richard Frank, “Finding the Key Players in Online Child Exploitation Networks,” Policy and Internet 3, no. 2 (2011): 1–25.

77 Richard Frank and Alexander Mikhaylov, “Beyond the ‘Silk Road’: Assessing Illicit Drug Marketplaces on the Public Web,” in Open Source Intelligence and Cyber Crime, eds. Mohammad A. Tayebi, Uwe Glässer, and David B. Skillicorn (Cham: Springer, 2020), 89–111; Mitch Macdonald and Richard Frank, “The Network Structure of Malware Development, Deployment and Distribution,” Global Crime 18, no. 1 (2016): 49–69; Mitch Macdonald and Richard Frank, “Shuffle Up and Deal: Use of a Capture-Recapture Method to Estimate the Size of Stolen Data Markets,” American Behavioral Scientist 61, no. 11 (2017): 1313–40; Alexander Mikhaylov and Richard Frank, “Illicit Payments for Illicit Goods: Noncontact Drug Distribution on Russian Online Drug Marketplaces,” Global Crime 19, no. 2 (2018): 146–70; Ahmed T. Zulkarnine, Richard Frank, Bryan Monk, Julianna Mitchell, and Garth Davies, “Surfacing Collaborated Networks in Dark Web to Find Illicit and Criminal Content,” in Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI), Tucson, AZ, USA, 109–14.

78 Bouchard et al., “Preliminary Analytical Considerations;” Davies et al., “Terrorist and Extremist Organizations’ Use;” Davies et al., “A Witch’s Brew of Grievances;” Frank et al., “Spreading the Message Digitally;” Scrivens et al., “Searching for Signs of Extremism on the Web;” Ryan Scrivens and Frank, “Sentiment-Based Classification of Radical Text on the Web,” in Proceedings of the 2016 European Intelligence and Security Informatics Conference (EISIC), Uppsala, Sweden, 104–7; Ryan Scrivens, Garth Davies, and Richard Frank, “Measuring the Evolution of Radical Right Wing Posting Behaviors Online,” Deviant Behavior 41, no. 2 (2020): 216–32; Scrivens, “Exploring Radical Right-Wing Posting Behaviors Online;” Scrivens et al., “Examining the Developmental Pathways;” Ryan Scrivens, George W. Burruss, Thomas J. Holt, Steven M. Chermak, Joshua D. Freilich, and Richard Frank, “Triggered by Defeat or Victory? Assessing the Impact of Presidential Election Results on Extreme Right-Wing Mobilization Online,” Deviant Behavior 42, no. 5 (2021): 630–45; Meghan A. Wong, Richard Frank, and Russell Allsup, “The Supremacy of Online White Supremacists – An Analysis of Online Discussions of White Supremacists,” Information and Communications Technology Law 24, no. 1 (2015): 41–73.

79 Frank et al., “Spreading the Message Digitally.”

80 Bouchard et al., “Preliminary Analytical Considerations;” Davies et al., “Terrorist and Extremist Organizations’ Use;” Scrivens, “Exploring Radical Right-Wing Posting Behaviors Online.”

81 For more on this threshold, see Frank et al., “Spreading the Message Digitally.”

82 See Conway, “Determining the Role of the Internet;” see also Scrivens et al., “The Role of the Internet.”

83 See Holt et al., “Introducing and Exploring the Extremist Cybercrime Database (ECCD).”

84 Joshua D. Freilich, Steven M. Chermak, Nadine M. Connell, Brent R. Klein, and Emily A. Greene-Colozzi, “Using Open-Source Data to Better Understand and Respond to American School Shootings: Introducing and Exploring the American School Shooting Study (TASSS),” Journal of School Violence 21, no 2 (2022); 93–118.

85 Ryan Scrivens, Tiana Gaudette, Maura Conway, and Thomas J. Holt., “Right-Wing Extremists’ Use of the Internet: Trends in the Empirical Literature,” in Right-Wing Extremism in Canada and the United States, eds. Barbara Perry, Jeff Gruenewald, and Ryan Scrivens (Cham: Palgrave, 2022), 355–80; Scrivens and Conway, “The Roles of ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Media Tools.”

86 See Frank et al., “Spreading the Message Digitally.”

87 Thomas J. Holt, Joshua D. Freilich, and Steven M. Chermak, “Examining the Online Expression of Ideology Among Far-Right Extremist Forum Users,” Terrorism and Political Violence 34, no. 2 (2022): 364–84.

88 Stall et al., “Kyle Rittenhouse and the Shared Meme Networks.”

89 Maura Conway, Moign Khawaja, Suraj Lakhani, and Jeremy Reffin, “A Snapshot of the Syrian Jihadi Online Ecology: Differential Disruption, Community Strength, and Preferred Other Platforms,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Ahead of Print (2021).

90 Paul Gill and Emily Corner, “Lone-Actor Terrorist Use of the Internet and Behavioural Correlates,” in Terrorism Online: Politics, Law, Technology and Unconventional Violence, eds. Lee Jarvis, Stuart Macdonald, and Thomas M. Chen (London: Routledge, 2015), 35–53.

91 Paul Gill, Emily Corner, Maura Conway, Amy Thornton, Mia Bloom, and John Horgan, “Terrorist Use of the Internet by the Numbers: Quantifying Behaviors, Patterns, and Processes,” Criminology and Public Policy 16, no. 1 (2017): 99–117.

92 Claire Seungeun Lee, Kyung-Shick Choi, Ryan Shandler, and Chris Kayser, “Mapping Global Cyberterror Networks: An Empirical Study of Al-Qaeda and ISIS Cyberterrorism Events,” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 37, no. 3 (2021): 333–55.

93 Joe Whittaker, “The Online Behaviors of Islamic State Terrorists in the United States,” Criminology & Public Policy 20, no. 1 (2021): 177–203.

94 Joe Whittaker, “The Role of Financial Technologies in US-Based ISIS Terror Plots,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Ahead of Print (2022).

95 Holt et al., “Introducing and Exploring the Extremist Cybercrime Database (ECCD).”

96 Ibid.

97 Jason Andress and Steve Winterfeld, Cyber Warfare: Techniques, Tactics and Tools for Security Practitioners, 2nd ed. (London: Elsevier, 2013); Dorothy E. Denning, “Cyber-Conflict as an Emergent Social Problem,” in Corporate Hacking and Technology-Driven Crime: Social Dynamics and Implications, eds. Thomas J. Holt and Bernadette H. Schell (Hershey, PA: IGI-Global, 2011), 170–86.

98 See Ryan Scrivens and Tiana Gaudette, “Terrorists’ and Violent Extremists’ Use of the Internet and Cyberterrorism,” in Crime Online: Causes, Correlates and Context, Fourth Edition, ed. Thomas J. Holt (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2021), 231–62.

99 Thomas J. Holt, Mattisen Stonhouse, Joshua D. Freilich, and Steven M. Chermak, “Examining Ideologically Motivated Cyberattacks Performed by Far-Left Groups,” Terrorism and Political Violence 33, no. 3 (2021): 527–48.

100 David Maimon and Eric R. Louderback, “Cyber-Dependent Crimes: An Interdisciplinary Review,” Annual Review of Criminology 2 (2019): 191–216.

101 Gary LaFree and Laura Dugan, “Introducing the Global Terrorism Database,” Terrorism and Political Violence 19, no. 2 (2007): 181–204.

102 See Joshua D. Freilich, Steven M. Chermak, Roberta Belli, Jeff Gruenewald, and William S. Parkin, “Introducing the United States Extremis Crime Database (ECDB),” Terrorism and Political Violence 26, no. 2 (2014): 372–84.

103 See Joshua D. Freilich, Steven M. Chermak, Nadine M. Connell, Brent R. Klein, and Emily A. Greene-Colozzi, “Using Open-Source Data to Better Understand and Respond to American School Shootings: Introducing and Exploring the American School Shooting Study (TASSS),” Journal of School Violence 21, no. 2 (2022): 93–118.

105 Chermak et al., “American Terrorism and Extremist Crime Data Sources and Selectivity Bias”; Laura Dugan and Michael Distler, “Measuring Terrorism,” in The Handbook on the Criminology of Terrorism, eds. Gary LaFree and Joshua D. Freilich (West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2016), 189–206.

106 Zeoli and Paruk, “Potential to Prevent Mass Shootings.”

107 See Gabriel Weimann and Katharina Von Knop, “Applying the Notion of Noise to Countering Online Terrorism,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 31, no. 10 (2008): 883–902.

108 Frank et al., “Spreading the Message Digitally.”

109 See Conway et al., “A Snapshot of the Syrian Jihadi Online Ecology”; see also Stall et al., “Kyle Rittenhouse and the Shared Meme Networks.”

110 See Lakomy, “Crouching Shahid, Hidden Jihad.”

111 Garth Davies, Ryan Scrivens, Tiana Gaudette, and Richard Frank, “They’re Not All the Same: A Longitudinal Comparison of Violent and Non-Violent Right-Wing Extremist Identities Online,” in Right-Wing Extremism in Canada and the United States, eds. Barbara Perry, Jeff Gruenewald, and Ryan Scrivens (Cham: Palgrave, 2022), 255–78; Ryan Scrivens, Thomas W. Wojciechowski, Joshua D. Freilich, Steven M. Chermak, and Richard Frank, “Comparing the Online Posting Behaviors of Violent and Non-Violent Right-Wing Extremists,” Terrorism and Political Violence. Ahead of Print (2021); Ryan Scrivens, Garth Davies, Tiana Gaudette, and Richard Frank, “Comparing Online Posting Typologies among Violent and Nonviolent Right-Wing Extremists,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Ahead of Print (2022); Ryan Scrivens, Thomas W. Wojciechowski, Joshua D. Freilich, Steven M. Chermak, and Richard Frank, “Differentiating Online Posting Behaviors of Violent and Nonviolent Right-Wing Extremists,” Criminal Justice Policy Review. Ahead of Print (2022); Ryan Scrivens, “Examining Online Indicators of Extremism among Violent and Non-Violent Right-Wing Extremists,” Terrorism and Political Violence. Ahead of Print (2022).

112 See Gary A. Ackerman and Lauren E. Pinson, “Speaking Truth to Sources: Introducing a Method for the Quantitative Evaluation of Open Sources in Event Data”, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 39, no. 7–8 (2016): 617–40; see also Chermak et al., “American Terrorism and Extremist Crime Data Sources and Selectivity Bias.”

113 Scrivens et al., “The Role of the Internet.”

114 For more information on the Dark Web Project, visit https://www.azsecure-data.org.

115 For more information on TDC, visit https://thedarkcrawler.com.

116 The National Archive of Criminal Justice Data also includes a few datasets from National Institute of Justice-funded projects related to online terrorism and extremism: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/pages/NACJD/index.html.

117 Gary LaFree and Joshua D. Freilich, “Government Policies for Counteracting Violent Extremism,” Annual Review of Criminology 2 (2018): 383–404.

118 See note 60 above.