Abstract

White nationalists represent a growing security threat worldwide. Of concern are their narratives and conspiracy theories that position immigrants of diverse color and religion as the feared “other”—outgroups that are perceived to threaten the values, resources and safety of White people. We use survey data from 570 White Australians to better understand how and why such perceived “outgroup threats” elicit prejudice toward non-White immigrants. We find that perceived outgroup threats are strongly associated with greater prejudice. Importantly, we find that belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy theory explains the outgroup threat/prejudice relationship, while heightened feelings of uncertainty strengthen the relationship.

The rise of White nationalism in Australia, like in many other parts of the world, poses a significant threat to the security and social cohesion of Australia’s multiethnic society.Footnote1 White nationalism is built on negative attitudes and prejudice toward immigrants of diverse color or religion, with prejudice reflecting an irrationally based, negative belief about certain immigrant groups and their members. White nationalists define White people as those from European ancestry of non-Jewish decent. They perceive the White race to be superior to other races, and they hold that White people should maintain their majority in majority-White countries, maintain their political and economic dominance and that their cultures and religions should be prioritized. They see non-White immigrants to be a threat to the White race and thus oppose immigration from non-White countries.Footnote2

While people are entitled to hold different attitudes about certain groups or to dispute and debate public policy over issues such as migration without being labeled racist, Swain argues that White nationalism diverts significantly from mainstream conservatism on these issues. She argues White nationalism becomes extremist in nature when: (1) it positions people of color as criminal by nature, (2) when non-White people are seen as a threat to the type of civilization that White people have created, (3) when arguments are made that the alleged genetic inferiority of racial minorities requires a regime of White separatism to preserve Western culture from degradation, and (4) when arguments are made to incite violence against people from non-White backgrounds.Footnote3

Not all White nationalists will act violently on their beliefs, but the ultimate concern for Australia’s intelligence agencies is another terrorist attack akin to the Christchurch massacre, which was perpetrated by an Australian White nationalist who believed in and promoted the “The Great Replacement” conspiracy theory.Footnote4 This conspiracy claims that Western governments are allowing their countries to be taken over, and White populations replaced, by non-White people.Footnote5

Australia is considered a fertile environment for White nationalism.Footnote6 Yet Grossman et al. note “the institutionalisation and expression of nationalist-exclusivist attitudes … have remained markedly under-researched in the Australian context”, despite mounting evidence of its growth in Australia.Footnote7 Drawing on survey data, our study explores how and why White Australians come to adopt such exclusivist attitudes toward non-White immigrants. We contend that prejudice toward non-White immigrants can be understood through the lens of outgroup threat; the perception that members of an “outgroup” (e.g., non-White immigrants) pose a real or imagined threat to members of an “ingroup” (e.g., White Australians).Footnote8 Prior research shows that outgroup threat can result in antiimmigrant sentiment and racial prejudiceFootnote9, but less is known about the psychological mechanisms by which this occurs. We propose that conspiracy beliefs play an important role in explaining why outgroup threat results in prejudice toward non-White immigrants. That is, we argue that conspiracy beliefs serve as an important psychological “bridge” explaining the outgroup threat–prejudice relationship. Further, we suggest that outgroup threat becomes particularly salient when people experience heightened uncertainty about the state of society.Footnote10 That is, when uncertainty is high, outgroup threat becomes more salient, thereby fostering stronger conspiracy beliefs and prejudice. By better understanding the relationship between these attitudes and beliefs in a general sample of White Australians, we hope to better understand the potential drivers of White nationalist ideology, and hope that interventions can be developed to prevent such attitudes morphing into more dangerous forms of White nationalism.

Before outlining our study in detail, we first highlight how Australia’s historical and current policy landscape surrounding immigration and border protection might contribute to perceiving non-White immigrants as a threat. This will be followed by a review of existing literature linking outgroup threat with prejudice, and a discussion of how conspiracy beliefs and uncertainty might explain and strengthen this relationship, respectively.

Australia’s Policy Landscape: A Catalyst for White Nationalism and Antiimmigrant Sentiment?

As noted above, Australia is considered a fertile environment for White nationalism. While there are many psychological reasons an individual might develop White nationalist views, it is important to understand some elements of Australia’s social, cultural and political history that help situate these views in a wider context. One-quarter of Australia’s 28 million residents were born overseas.Footnote11 Yet, while Australia has maintained large-scale multiethnic immigration for decades, and prides itself on accepting migrants from all countries of the world, this was not always the case.Footnote12 From 1901, Australia’s Immigration Restriction Act effectively prohibited people of color and non-European ancestry from entering Australia.Footnote13 This approach was known colloquially as the White Australia Policy, as it gave preferential treatment to British migrants over others until 1966. It was only in 1975 that the Racial Discrimination Act was passed, which made racially based immigration selection criteria unlawful.

However, the legacy of the White Australia Policy remains, with non-White immigration and asylum policy a continual feature of political debate today. In the early 2000s, the Howard administration (1996–2007) labeled illegal immigrants arriving by boat from the Middle East and Central Asia as a national security threat. Illegal arrivals peaked in 2013, with more than 20,000 illegal immigrants from Muslim-majority countries being processed that year. Since then, Australia’s conservative governments have continued to make it a key policy goal to “stop the boats”. Illegal immigrants who do make it to Australia are processed and detained indefinitely until appropriately vetted (in many cases this can take years). These policies have been touted by conservative governments as protecting Australians from harm.Footnote14 Narratives about the dangers posed by immigrants and asylum seekers persist and are heightened once more as we write, following a decision of the High Court of Australia that saw nearly 150 people held in immigration detention immediately released. Both sides of politics have accused each other of releasing “dangerous” outsiders into the community.

While most Australians welcome the diversity that multiethnic immigration brings, prejudice continues to influence some Australians’ attitudes toward non-White immigrants.Footnote15 In 2017, for example, 20% of Australians still favored exclusivist immigrant selection policies based on race, ethnicity or religion.Footnote16 Antiimmigrant rhetoric and moral panics about “boat people”, immigrants from conflict zones and the place of Islam in Australian society continue to pervade public discourse in Australia, which perpetuates perceptions of outgroup threat and prejudicial attitudes among a minority of the White population.Footnote17

The Link between Outgroup Threat and Prejudice: A Summary of Existing Literature

“Outgroup threat” has been identified as a major predictor of ingroup prejudice toward outgroup members.Footnote18 An ingroup is a group to which one belongs and strongly identifies with, while an outgroup is any group to which one does not belong or identify with. Group identity is important because people tend to behave in ways that benefit their ingroup at the cost of outgroups, especially when they feel threatened by an outgroup.Footnote19 According to Riek et al., outgroup threat occurs when “one group’s actions, beliefs, or characteristics challenge the goal attainment or well-being of another group”.Footnote20 This can result in hostility and other forms of antisocial behavior toward members of the outgroup. This concept can help to explain prejudice toward any outgroup, but it is frequently used to explain hostility directed toward immigrants from ethnic, racial and religious minority groups.Footnote21

Numerous scholars have explored the link between outgroup threat and prejudice. Drawing on Stephan and Stephan’s Integrated Threat Theory, this body of work consistently identifies two types of outgroup threat that can generate prejudice: realistic threat and symbolic threat.Footnote22 Realistic threat has its origins in realistic group conflict theory, which seeks to understand intergroup conflict.Footnote23 It captures perceptions that a particular outgroup poses a threat to the power or resources of one’s ingroup. As Stephan et al. note, realistic threats typically arise from “competition for scarce resources such as land, power, or jobs, but they can also arise because of threats to the welfare of the group”.Footnote24 For example, White Australians may see non-White immigrants as disrupting the economic or political power of their country, and taking away their jobs and/or housing. Symbolic threat, by contrast, captures fears around perceived differences in morals, values, norms, beliefs and culture. Symbolic threat is often experienced when ingroup members perceive that their way of life or value system is being undermined by an outgroup. It is typically based in perceived moral rightness or superiority of the ingroup’s perspective.Footnote25 For example, White Australians may perceive that increasing numbers of immigrants from diverse ethnicities and religions are changing the identity, culture and religious values of Australia. Stephan et al. argue these outgroup threats generate prejudice to varying degrees depending on the nature of the relationship between the outgroup and ingroup.Footnote26 If the groups have a history of conflict, realistic threats should be most strongly associated with prejudice. If the groups are extremely dissimilar in terms of values, norms, beliefs and practices, then symbolic threat should best predict prejudice.Footnote27

Many empirical studies have linked perceived realistic and symbolic threats with prejudice toward non-White immigrants specifically. Stephan et al., for example, explored public attitudes toward Moroccan and Ethiopian immigrant groups in Spain and Israel.Footnote28 They found that survey participants who perceived these immigrants as both a realistic and symbolic threat were more likely to hold negative attitudes toward these immigrant groups. Similarly, Schweitzer et al. demonstrated that both realistic and symbolic threat were positively related to increased prejudice directed toward refugees in Australia.Footnote29 And Velasco-González et al. found that perceiving Muslims as a symbolic threat, but not a realistic threat, was correlated with Dutch adolescents’ prejudice toward Muslim immigrants and reduced support for multiculturalism.Footnote30

A third type of outgroup threat—terroristic threat—was added more recently to Integrated Threat Theory. This was done on the basis that people can conflate Islam with terrorism, which generates fear and prejudice toward Muslims specifically.Footnote31 Doosje et al. found that perceived terroristic threat was related to both subtle and blatant prejudice and discriminatory intentions directed toward Muslim immigrants in nine European countries.Footnote32 Perceived terroristic threat predicted personal discrimination against Muslims, higher approval of institutional discrimination against Muslims, and higher endorsement of strict antiimmigration policies limiting Muslim immigration. Uenal found that terroristic threat was associated with anti-Islam sentiment, while realistic threat was associated with anti-Muslim prejudice, and symbolic threat with both.Footnote33 Hence, there is strong evidence linking outgroup threat to prejudice toward non-White immigrants, but more research on the specific mechanisms involved—including the role of conspiracy thinking and uncertainty—is needed.

Linking Conspiracy Theory Beliefs and Uncertainty to Outgroup Threat and Prejudice

To explain how outgroup threat can generate prejudice, Gaertner and Dovidio theorized that outgroup threat perceptions lead people to feel discomfort, anxiety, uneasiness, fear and disgust.Footnote34 These feelings then result in negative views and prejudice directed toward the source of perceived threat. We offer an alternative explanation. We suggest that outgroup threat can elicit “motivated reasoning” processes that enhance belief in conspiracy theories that denigrate non-White immigrants. We further propose that heightened feelings of uncertainty about the state of society (caused by a myriad of factors, such as low political trust, declining social capital, ongoing wars/international conflict, mass migration, economic uncertainty, COVID-19, etc.) strengthen the effect of outgroup threat on conspiracy belief formation and prejudice. Consistent with a wider literature on conspiracy thinking, we suggest that conspiracy beliefs provide meaning and predictability to uncertain situations and provide people with a sense of control and certainty.Footnote35 As such, conspiracy beliefs foster prejudice toward the source of the perceived threat in order to protect against the feelings of discomfort, anxiety, uneasiness, fear or disgust generated by the initial outgroup threat perception.

Conspiracy theories are explanatory frameworks that claim that events and processes in society result from secretive actions conducted by a small group of individuals in power or by members of a particular social category.Footnote36 They often portray some outgroup acting behind closed doors, plotting a nefarious agenda that seeks to either control or harm members of one’s ingroup or society more broadly (e.g., weaken the ingroup’s political or economic power, change their way of life/culture, or physically hurt them).Footnote37 As such, conspiracy theories place blame onto, and promulgate fear about, outgroups. Scholars have argued that outgroup threat perceptions can result in individuals believing in conspiracy theories about a particular outgroup to make some abstract threat from that outgroup more concrete.Footnote38

Conspiracy theories have important political and social consequences and have been linked to violent extremism and outgroup hatred.Footnote39 For example, conspiracy theories about Jewish people dominating the world are strongly associated with anti-Semitic attitudes and attacks against Jews.Footnote40 Conspiracy beliefs about Jewish people have even been shown to predict enhanced prejudice toward not only Jewish people but also toward other outgroups (e.g., Asians, Arabs).Footnote41 Importantly, White nationalist group narratives are littered with conspiracy theories.Footnote42 The perpetrator of the Christchurch massacre, for example, believed in The Great Replacement conspiracy.

The Great Replacement is the most widely known conspiracy theory linked to antiimmigrant sentiment and features heavily in the narratives espoused by White nationalist groups.Footnote43 It falsely claims that Western governments and immigrant groups are intentionally replacing White Christian populations with Muslims and other ethnic/racial minority groups. It stokes fears that non-White immigrants are plotting to destroy the political power of White people and to erase the host country’s culture and values.Footnote44 According to Moscovici, minority groups are prone to being framed as collective conspirators in conspiracy theories like The Great Replacement.Footnote45 This has much to do with the perceived symbolic threat that immigrants from different cultures, religions and ethnicities can pose to a predominantly White Christian ingroup.

Indeed, Uenal provided empirical evidence linking perceived outgroup threat to conspiracy beliefs about the Islamization of Europe.Footnote46 Drawing on German survey data, Uenal revealed that symbolic threat was associated with increased belief in The Great Replacement.Footnote47 And Obaidi et al. found that heightened Great Replacement beliefs were associated not only with persecution of Muslims in Norway and Denmark, but also with self-reported violent intentions toward Muslims.Footnote48 Interestingly, Obaidi et al. presented evidence suggesting that symbolic and realistic threats both explained the association between conspiracy belief and prejudice.Footnote49 That is, believing in The Great Replacement conspiracy heightened people’s perception that Muslims and Islam posed a realistic and symbolic threat to Danes and Norwegians. In turn, this enhanced respondents’ prejudice toward Muslims (i.e., conspiracy belief → outgroup threat → prejudice). This latter finding contradicts Uenal’s suggestion that outgroup threat precedes conspiracy belief formation.Footnote50

We side with Uenal’s position that outgroup threat precedes conspiracy belief formation, and propose that conspiracy beliefs explain the relationship between outgroup threat and prejudice (i.e., outgroup threat → conspiracy belief → prejudice). We draw on Van Prooijen’s Existential Threat Model of conspiracy theory formation to confirm our position.Footnote51 We add that these relationships will be strongest when people experience heightened feelings of uncertainty about society.

A “Mediating” Role for Conspiracy Beliefs and a “Moderating” Role for Uncertainty?

People come to believe in conspiracy theories to meet some personal need for security and control, especially under conditions of uncertainty.Footnote52 Uncertainty arises when people feel anxious, powerless or experience anomie (where they perceive that the moral fabric of society is declining). It can flourish in conditions where political trust is low, when social capital has been eroded or due to concern over ongoing domestic and world issues (e.g., wars, pandemics, economic hardship).Footnote53 Uncertainty involves perceived discrepancies between a person’s current circumstances and some preferred expectation or desire.Footnote54 Uncertainty has been shown to directly promote belief in various conspiracy theories, but it can also strengthen the effect of perceived outgroup threat on conspiracy belief formation.Footnote55 When people feel highly uncertain—about a given group, event, situation or circumstance—perceived outgroup threats can become more salient and enhance belief in specific conspiracy theories relevant to their circumstances. In other words, existing empirical research suggests that uncertainty statistically “moderates” (i.e., strengthens) the association between outgroup threat and conspiracy belief [moderation occurs if the strength of a relationship between an independent variable (e.g., outgroup threat) and dependent variable (e.g., prejudice) varies by a third variable (e.g., uncertainty)].

In his Existential Threat Model of conspiracy belief formation, Van Prooijen suggested that heightened uncertainty stimulates a need for information, in what Van Prooijen refers to as an epistemic sense-making process.Footnote56 Sense-making involves an attempt to establish simple yet meaningful causal relationships between seemingly random information. People need to recognize these expected relationships to experience their world as predictable. Linking this argument back to outgroup threat, Van Prooijen argues that the sense-making in response to a perceived threat makes people hypervigilant and prone to overestimate an outgroup’s hostile intentions.Footnote57 He suggests this perceived threat leads to biased and distorted mental processing of information that can make people “see” connections and patterns between events and actions that are not there. Biased mental processing can also make people explain events and actions as an “intentional and evil scheme by powerful conspirators”.Footnote58 In other words, perceived outgroup threats elicit conspiracy beliefs by stimulating two types of mental processing that can distort perceptions of reality. The first is seeing patterns among random, unconnected information, and the second is seeing hostile intentions/agency where none exists.Footnote59 This sense-making process serves to reassert control in response to threat and feelings of uncertainty. Hence, one way to efficiently reduce feelings of uncertainty that perceived threats produce is to formulate clear and subjectively certain opinions and beliefs about reality. Kossowska and Bukowski argue that conspiracy theories do this by attributing “significant unexplained events to a secret activity undertaken by powerful individuals, groups, or organizations”, thereby providing “a sense of coherence, understanding and reduction of ambiguity”.Footnote60 Hence, conspiracy theories allow people to retain a sense of safety and predictability in a seemingly uncertain world.

In Van Prooijen’s Existential Threat Model, distressing events and situations (i.e., threats) produce conspiracy theories only when people can blame those threats on the nefarious actions of a salient or antagonistic outgroup.Footnote61 This explains why many conspiracy theories, such as The Great Replacement conspiracy, blame social problems or societal events on outgroups that are perceived to be a threat (e.g., Muslims, Jews, non-White immigrants). This hostile outgroup is often negatively stereotyped (e.g., depicted as a threat to safety, values and resources), and so these threatening qualities subsequently reinforce people’s suspicion and hostility toward the outgroups.Footnote62

Uenal provided empirical evidence that outgroup threat precedes the formation of conspiracy beliefs, and other research has revealed that conspiracy beliefs can precede the development of prejudice.Footnote63 Yet only two published studies (of which we are aware) have directly tested whether conspiracy beliefs explain (i.e., mediate) the outgroup threat/prejudice relationship. The first study was conducted in Poland and Ukraine by Bilewicz and Krzeminski who found that experiencing symbolic threat from Jewish people influenced participants’ support for discriminatory policies toward Jews (i.e., prejudice).Footnote64 Importantly, they also found that this relationship could be explained by beliefs about Jewish control in the areas of politics, economy and media; that is, conspiracy beliefs about Jews mediated the perceived symbolic threat and prejudice relationship.

In the second study, Mashuri and Osteen found a similar relationship. But they investigated the attitudes of Muslims as the majority group in Indonesia (i.e., the ingroup) toward non-Muslims living in Indonesia (i.e., the outgroup).Footnote65 Mashuri and Osteen suggested to participants that non-Muslim minority groups living in Indonesia pose a threat to the majority group because they are associated with distant Western threats to Muslim culture (symbolic threat) and economic power (realistic threat). They found that highlighting these outgroup threats made participants more willing to ban interreligious or interfaith discussions and dialogs.Footnote66 These threats also enhanced participants’ support for collective protest against the outgroup. Importantly, like in the Bilewicz and Krzeminski study, participants’ conspiracy beliefs about the West having conspired to harm Islam or Muslims explained these relationships. Belief in the presented anti-West conspiracy theory led ingroup members (Muslims) to become suspicious that the outgroup (non-Muslims) had malevolent intentions to harm them, which explained their religious intolerance and support for collective protest.Footnote67

The two aforementioned studies support the idea that conspiracy beliefs serve as an important psychological “bridge” linking outgroup threat to prejudice. But neither study shed light on whether conspiracy beliefs explain the relationship between outgroup threat and prejudice toward non-White immigrants specifically. Both studies also did not explore whether feelings of uncertainty strengthened the relationship between outgroup threat, conspiracy belief and prejudice.

The Current Study

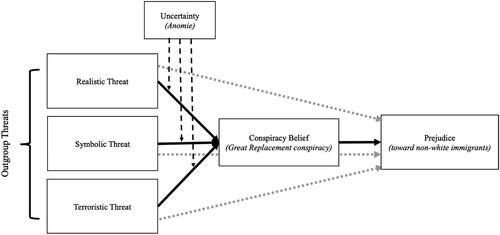

Our study examines whether outgroup threat enhances prejudice toward non-White immigrants in Australia. Importantly, it tests whether belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy theory explains (i.e., mediates) the relationship between perceived outgroup threat and prejudice, and examines whether these relationships are strengthened (i.e., moderated) by feelings of uncertainty. As such, our study aims to better understand why and how outgroup threat can elicit prejudice toward non-White immigrants among White Australians. presents our conceptual model.

Our study builds on earlier work in four important ways. First, it focuses on prejudice toward non-White immigrants specifically. Second, it tests whether three forms of outgroup threat (realistic, symbolic and terroristic) are positively associated with conspiracy beliefs (specifically, belief in The Great Replacement) and prejudice toward non-White immigrants.Footnote68 Third, it empirically tests whether Great Replacement conspiracy beliefs explain the relationship between perceived outgroup threat and prejudice (i.e., a mediation effect is tested). Finally, it explores whether feelings of uncertainty strengthen these relationships (i.e., a moderation effect is tested). Uncertainty in our study is conceptualized as “anomie”; the view that societal norms and the moral fabric of society is declining and so people can no longer be trusted. We use anomie as our measure of uncertainty, as prior research suggests it is associated with heightened conspiracy beliefs and prejudice, and can often be higher during periods marked by mass immigration.Footnote69 We test six hypotheses:

H1: Outgroup threats (realistic, symbolic and terrorist) will be positively associated with prejudice toward non-White immigrants.

H2: Outgroup threats will be positively associated with conspiracy beliefs (i.e., The Great Replacement).

H3: Uncertainty (i.e., anomie) will strengthen (i.e., moderate) the relationship between outgroup threats and conspiracy beliefs, such that the relationship between outgroup threats and conspiracy beliefs will be stronger for those who experience heightened uncertainty.

H4: Conspiracy beliefs will be positively associated with prejudice.

H5: Conspiracy beliefs will explain (i.e., mediate) the relationship between outgroup threats and prejudice.

H6: Uncertainty will strengthen the mediation effect tested in H5, such that the mediation effect will be stronger among those who experience heightened uncertainty (i.e., a moderated-mediation relationship).

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedure

Survey participants were recruited over a four-week period using Facebook’s AdManager function. Facebook allows researchers to advertise a survey to its users based on demographic criteria (e.g., those aged 18+; living in Australia). Facebook is often used by individuals and groups to spread conspiracy beliefs.Footnote70 As such, it represented a viable way to recruit participants with conspiracy beliefs.

The survey and broader project received ethics approval from Griffith University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference: 2021/613 and 2023/095, respectively). Only Australian Facebook users aged 18+ were invited to complete a survey about ethnic diversity and immigration in Australia. The Facebook advertisement directed interested participants to a LimeSurvey web link where they could provide consent and complete an anonymous online survey. During the four-week fielding period, 1,560 Facebook users clicked on the LimeSurvey link, but only 960 individuals submitted their survey responses (61.5% cooperation rate). After removing participants who had completed less than 50% of the survey (n = 300) a final useable sample of 660 participants was achieved. This represents a 42.3% adjusted cooperation rate.

Participants ranged in age from 18 to 89 (M = 57.17; SD = 14.52), 37.1% were men, 72.6% were born in Australia, 69.7% reported being university educated, and respondents from all states and territories in Australia were well represented (see ). Of the 660 participants, 570 reported being Caucasian, 19 identified as Indigenous-Australian, 25 were of Asian descent, 39 selected the “other” category, and the remaining seven respondents chose not to divulge their ethnic/racial background. Given our study seeks to better understand the negative attitudes espoused by White nationalists, only responses provided by White Australian participants were analyzed (i.e., Caucasians; N = 570).

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

Measures

The survey contained 168 items, but only items described in or below were included in this article. They included: outgroup threats (symbolic, realistic and terroristic); conspiracy belief (i.e., belief in The Great Replacement), uncertainty (i.e., anomie), prejudice toward non-White immigrants, and control variables. All multi-item scales were subjected to a single principal-axis factor analysis using promax rotation (six factors were specified in the model). shows there was no cross-loading between any items across the six factors, and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Test was satisfactory (.95). Each multi-item scale was also reliable as evidenced by Cronbach alpha scores.

Table 2. Principal axis factor analysis (with promax rotation) exploring the discriminant validity of all multi-item scales.

Outgroup Threats: Independent Variable

Outgroup threats arising from non-White immigrants was measured using three multi-item scales: (a) realistic threat, (b) symbolic threat and (c) terroristic threat. Each scale was measured on a 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree Likert scale, with higher scores reflecting stronger perceptions of outgroup threat.

Realistic threat was measured using three items designed to capture perceived threats related to available resources (i.e., jobs, housing). They were adapted from the work of Stephan et al. (e.g. “Because of the presence of immigrants, White Australians have more difficulties in finding a job”; M = 2.22; SD = 1.11; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92).Footnote71 Symbolic threat was measured using three items adapted from the work of Stephan et al. and Obaidi et al.Footnote72 It measures perceived outgroup threats related to culture, worldviews and beliefs (e.g., “Australian identity is being threatened because there are too many immigrants”; M = 2.26; SD = 1.31; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97). Terroristic threat was measured with two items adapted from the work of Uenal and measured the perceived threat of terrorism from Islam and Muslims (e.g., “I am worried that Australia’s peaceful society is being threatened by radical Islamist groups”; M = 3.25; SD = 1.08; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84).Footnote73

Uncertainty: Moderator Variable

Uncertainty was measured with four items adapted from the work of Teymoori et al. and McCarthy et al.Footnote74 The items have been used previously to measure feelings of anomie (a state of mind where individuals perceive that the moral fabric of society is declining and that people can no longer be trusted) (e.g., “There seems to be an absence of moral standards these days”). Each item was measured on a 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree Likert scale; higher scores reflect higher levels of uncertainty (M = 3.30; SD = 0.94; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85).

Conspiracy Beliefs: Mediator Variable

Conspiracy beliefs were measured by asking participants how much they endorsed beliefs based on The Great Replacement conspiracy theory. The four items used were adapted from the work of Obaidi et al. and have been previously used to measure the belief that Muslim immigrants are secretly plotting to replace the White majority group (e.g., “Muslim migration to Australia is part of a bigger plan to make Muslims a majority of the population”).Footnote75 Each item was measured on a 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater endorsement of The Great Replacement conspiracy (M = 2.18; SD = 1.22; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94).

Prejudice: Dependent Variable

Prejudice was measured using three items based on the work of Williamson et al.Footnote76 These items measure (in)tolerance of non-White immigrants in Australia (e.g., “Racial/ethnic minority groups bring diversity and interest to Australians”). Each item was measured on a 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree Likert scale. Items were reverse scored so that higher scores on the scale reflected greater prejudice toward non-White immigrants (M = 1.90; SD = 0.98; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93).

Control Variables

Control variables were: age (M = 58.21; SD = 13.84), gender [dummy coded as 0 = female (63.0%); 1 = male (37.0%)), country of birth (dummy coded as 0 = overseas (25.2%); 1 = Australia (74.8%)], educational attainment (1 = did not finish high school; 2 = high school; 3 = trade; 4 = university degree; 5 = postgraduate degree; M = 3.78; SD = 1.19) and political leaning. Political leaning was measured with one item: “Some people talk about ‘left’ (e.g., Australian Labour Party, Greens), ‘right’ (e.g., Liberal National Party, One Nation) and ‘center’ to describe political parties and politicians. With this in mind, where would you place yourself in terms of your support for political parties?” This was measured on a scale of 1 = very left-wing to 4 = center to 7 = very right-wing scale (M = 3.27; SD = 1.65; 54.1% of respondents reported being left-leaning, 21.5% were centrist, and 24.4% were right-leaning).

Results

Bivariate Correlations

All bivariate relationships between measures were in the direction expected (see ). The three outgroup threat scales were positively associated with each other. Each was also positively associated with uncertainty, conspiracy beliefs and prejudice, respectively. Likewise, uncertainty, conspiracy beliefs and prejudice were each positively associated with each other.

Table 3. Bivariate correlations.

Importantly, we captured a substantial number of participants who endorsed The Great Replacement conspiracy theory. shows that 15.3% of the sample agreed with the statement “Muslims want to invade and colonize Australia”, and 27.4% agreed that “Immigration from Muslim countries poses an existential threat to Australians”. In addition, 15.8% agreed that “Muslim migration to Australia is part of a bigger plan to make Muslims a majority of the population”. Fewer than 10% of respondents, however, reported holding explicit prejudicial attitudes toward non-White immigrants (e.g., 9.7% disagreed with the statement “It is a good thing for society to be made up of different cultures”; see ).

Table 4. Level of endorsement for The Great Replacement conspiracy theory and prejudice.

Testing Our Conceptual Model

The moderated-mediation model presented in our conceptual model (see ) was tested using Model 7 of the “PROCESS” macro in Statistical Package for Social Sciences v28. Bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (N = 5,000) were used to test the significance of the indirect (i.e., mediated) effects of outgroup threat on prejudice via conspiracy beliefs, and how these relationships were moderated by uncertainty (i.e., conditional indirect effects). An index of moderated mediation was used to test the significance of the moderated-mediation effects (i.e., the difference of the indirect effects across different levels of uncertainty). Importantly, all continuous variables were mean-centered before entry into the models. Significant effects are supported by the absence of zero within the confidence intervals. Prior to running the regression models, collinearity diagnostics for all multi-item scales were computed. Variance Inflation Factor scores were below 5.0, revealing no issues with multicollinearity.

Is Outgroup Threat and Uncertainty Associated with Belief in The Great Replacement Conspiracy?

presents three regression models that use outgroup threat measures (i.e., realistic, symbolic and terroristic threat), uncertainty and control variables as predictors of The Great Replacement conspiracy belief. Model 1 shows the results where realistic threat was the focal predictor of conspiracy beliefs. Model 2 shows the results where symbolic threat was the focal predictor of conspiracy beliefs. Model 3 presents terroristic threat as the focal predictor of conspiracy beliefs. Of the control variables, shows only age and political leaning were significantly associated with conspiracy beliefs; older participants and right-leaning participants were more likely to believe in statements aligned with The Great Replacement conspiracy, although age was only weakly associated with these beliefs.

Table 5. PROCESS models showing predictors of conspiracy belief, with either realistic, symbolic or terrorist threat as the focal predictor.

As expected, uncertainty was positively associated with Great Replacement beliefs; those who felt greater uncertainty were also more likely to believe in The Great Replacement conspiracy. With respect to the outgroup threat measures, both symbolic threat and terroristic threat were positively associated with The Great Replacement measure across all three models. However, realistic threat was unrelated to The Great Replacement measure in our data. These findings suggest that those who were concerned that non-White immigrants pose a threat to Australia’s way of life or safety were most likely to agree with statements that aligned with The Great Replacement conspiracy.

Does Uncertainty “Moderate” the Relationship Between Outgroup Threat and Belief in The Great Replacement Conspiracy?

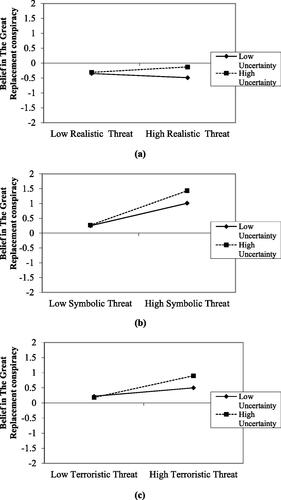

shows interaction effects (i.e., moderation effects) between uncertainty and each of the three outgroup threat measures on conspiracy beliefs. depicts these moderation effects graphically. While there was no direct relationship between realistic threat and conspiracy beliefs, Model 1 in shows that uncertainty moderated the relationship between realistic threat and belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy (see ). For those scoring high on uncertainty (+1 SD), the positive relationship between realistic threat and belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy was much stronger than those scoring low on uncertainty (−1 SD). In fact, simple slope effects revealed a significant and positive relationship between realistic threat and conspiracy beliefs for those high on uncertainty (b = .08; lower limit confidence interval [LLCI] = .01; upper limit confidence interval [ULCI] = .16) but a negative and insignificant association for those scoring low on uncertainty (b = −0.07; LLCI = −0.16; ULCI = .02).

Figure 2. Interaction (i.e., moderation) effects between (a) realistic threat and uncertainty, (b) symbolic threat and uncertainty, and (c) terroristic threat and uncertainty, on belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy theory. Note: All measures have been mean-centered.

Uncertainty also interacted with symbolic threat on belief in The Great Replacement (Model 2 of ) and with terroristic threat on belief in The Great Replacement (Model 3). While the association between symbolic threat and belief in The Great Replacement was positive for those scoring both low (b = .38; LLCI = .30; ULCI = .47) and high (b = .57; LLCI = .50; ULCI = .64) on uncertainty, those scoring high on uncertainty did show a stronger positive relationship between symbolic threat and belief in the conspiracy (see ). The same interaction pattern observed for symbolic threat was observed for terroristic threat (see ). That is, the relationship between terroristic threat and belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy was significant and positive for those scoring both high and low on uncertainty, but it was stronger for those scoring high on feelings of uncertainty (b = .35; LLCI = .28; ULCI = .41) compared to those scoring low on uncertainty (b = .15; LLCI = .08; ULCI = .22).

Does Belief in The Great Replacement Conspiracy “Mediate” the Relationship between Outgroup Threat and Prejudice, and Is This Relationship “Moderated” by Uncertainty?

displays findings for a moderated-mediation model examining prejudice as the outcome variable. It shows that both realistic threat (b = .19; LLCI = .12; ULCI = .26) and symbolic threat (b = .33; LLCI = .24; ULCI = .41) were positively and significantly associated with prejudice. Participants who perceived immigrants as a greater threat to resources (i.e., realistic threat) or Australia’s way of life/culture (i.e., symbolic threat) displayed more prejudice toward non-White immigrants. Terroristic threat was unrelated to prejudice when controlling for all other variables in the model.

Table 6. Moderated mediation with realistic, symbolic and terroristic threat as the focal predictors of prejudice.

Of particular interest is the significant and positive association between belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy (i.e., the mediator variable) and prejudice. Participants who believed more strongly in The Great Replacement conspiracy also showed higher levels of prejudice toward non-White immigrants (b = .16; LLCI = .08; ULCI = .25).

also shows the indirect effects of each type of outgroup threat on prejudice via the mediator variable (i.e., belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy) at both low and high levels of uncertainty. First, the findings show that belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy significantly explained (i.e., mediated) the association between symbolic threat and prejudice for participants who scored both low (b = .06; LLCI = .02; ULCI = .11) and high (b = .09; LLCI = .03; ULCI = .16) on uncertainty. The index of moderated mediation (b = .02; LLCI = .00; ULCI = .03) was significant, suggesting the mediation effect varied by level of uncertainty. This indicates that believing in The Great Replacement conspiracy explained the symbolic threat/prejudice relationship more strongly for those participants who expressed high (+1 SD) levels of uncertainty.

Second, shows that conspiracy belief explained the association between terroristic threat and prejudice for participants who scored both low (b = .02; LLCI = .01; ULCI = .05) and high (b = .06; LLCI = .02; ULCI = .10) on uncertainty. Again, the index of moderated mediation was significant (b = .02; LLCI = .01; ULCI = .03), suggesting that this mediation effect was strongest for those who scored high on uncertainty. Finally, the realistic threat to prejudice relationship was not mediated by belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy for either those who scored low or high on uncertainty.

Discussion

Our study aimed to understand how and why outgroup threat can elicit White Australians’ prejudice toward non-White immigrants. We examined the relationship between three different types of outgroup threat (i.e., realistic, symbolic or terroristic) and prejudice. Importantly, we explored whether belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy theory could explain this relationship, and whether this relationship was strongest for those who experienced greater feelings of uncertainty about society.

Findings and Their Implications

In sum, our findings suggest that belief in conspiracy theories—specifically The Great Replacement conspiracy—is critically important for explaining why perceived outgroup threat from immigrants can enhance prejudice toward non-White immigrants. Our findings also show that these conspiracy beliefs have their greatest explanatory effect for those who experience greater feelings of uncertainty about society.

As expected, we found that outgroup threat was positively associated with White Australians’ prejudice toward non-White immigrants (support for H1); both realistic and symbolic threat were significantly associated with higher levels of prejudice, but terroristic threat was not. In other words, when immigrants were perceived to threaten Australians’ access to resources or their values and way of life, prejudice toward non-White immigrants was higher. These findings support prior research linking symbolic and realistic threat to prejudice.Footnote77 Of the two outgroup threats, however, symbolic threat had the strongest association with prejudice in our study (see ). This specific finding supports Stephan et al.’s proposal that symbolic threat should be the stronger predictor of prejudice if the ingroup and outgroup are extremely dissimilar in terms of culture, values, beliefs and practices.Footnote78 The fact that symbolic threat appeared to be the most salient of the three types of outgroup threat in our study is not surprising. Our studied sample comprised all White respondents and our survey questions asked them about their opinion regarding non-White immigrants to Australia; specifically, their openness to the diversity in culture and ideas that these groups bring to Australia. Such question framing thus highlighted the underlying symbolic differences that non-White immigrant groups pose to White Australians.

The fact that symbolic and realistic—but not terroristic—threats were significantly associated with prejudice toward non-White immigrant outgroups is an important finding. Anti-Muslim prejudice, for example, has been linked to perceived threats of terrorism.Footnote79 Perceiving that Muslims are taking jobs and resources away from a White population (realistic threat), and that Islam poses a threat to White culture and values (symbolic threat), may be a more significant driver of White Australians’ prejudiced beliefs about Muslim immigrants than the perception that Muslims are responsible for terrorism (terroristic threat).

Outgroup threat was also found to be positively associated with heightened support for The Great Replacement conspiracy theory (support for H2). This finding supports previous research showing that perceiving outgroup threat elicits stronger belief in conspiracy theories.Footnote80 Symbolic threat was again the outgroup threat most strongly linked with participants’ belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy, with those who perceived immigrants as posing a greater threat to the values and way of life of Australia being more likely to believe in The Great Replacement conspiracy (see ). Terroristic threat was also associated with such beliefs. Given that Islam is often conflated with terrorism, and has been depicted as conflicting with Christian values, it is unsurprising that both terroristic and symbolic threat featured most prominently as predictors of belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy.Footnote81

Our findings also supported H4 and H5. We hypothesized and confirmed that Great Replacement conspiracy believers would be more likely to express heightened levels of prejudice toward non-White immigrants (H4). We also hypothesized and confirmed that these conspiracy beliefs would explain (i.e., mediate) the relationship between outgroup threat and prejudice (H5). Given that The Great Replacement conspiracy claims that non-White immigrants are plotting to replace White populations, it is not surprising that belief in that specific conspiracy theory would help to explain greater levels of prejudice against non-White immigrants. However, given that symbolic—but not terroristic—threats were associated with prejudice, a distinction might be drawn between belief in The Great Replacement based in symbolic compared to terrorist threat perceptions. When driven by symbolic threat perceptions, belief in The Great Replacement should be of greater concern to law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

More broadly, levels of agreement with Great Replacement beliefs in our data are concerning. Just over 15% of the sample agreed that Muslims were plotting to invade and colonize Australia and replace White Australians, and more than 25% agreed that immigration from Muslim countries posed an existential threat to Australians (see ). As belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy is linked directly to White nationalist terrorist attacks globally, including the Christchurch massacre, it might be expected that only a very small percentage of the Australian population would agree with the conspiracy theory. Our data do not suggest that people agreeing with the survey statements about The Great Replacement necessarily agree with the conspiracy theory to the same extent as it is elaborated on in the Christchurch offender’s manifesto. However, it is nonetheless concerning that a notable percentage of the general White Australian population does agree with core Great Replacement beliefs when asked about them indirectly in a survey about attitudes toward immigration and ethnic/racial/religious diversity.

Finally, we suggested that feelings of uncertainty would strengthen the relationship between outgroup threat and conspiracy beliefs (H3) and that the relationship linking outgroup threat, conspiracy beliefs and prejudice would also be stronger for those experiencing greater uncertainty (H6). Again, we found general support for H3 and H6, but only when considering symbolic threat and terroristic threat.

In sum then, believing in a conspiracy theory like The Great Replacement does appear to serve as an important psychological “bridge” explaining why outgroup threat enhances White Australians’ prejudice toward non-White immigrants. The absence of realistic threat in the moderated-mediation effects might be explained by the fact that realistic threat perceptions (e.g., that immigrants are taking jobs or housing away from White Australians) relate to more practical and perennial concerns about immigration and other areas of government policy. By contrast, symbolic and terroristic threats may be more amenable to the grandiose, concocted explanations found in conspiracy theories like The Great Replacement and prejudice.

In any case, the role of uncertainty in driving people to believe in conspiracy theories as a sense-making process is clear. Scholars suggest that conspiracy theories tend to become activated when peoples’ surroundings are perceived as threatening and when they experience heightened uncertainty.Footnote82 Belief in conspiracy theories can be thought of as a motivated reasoning response for reestablishing certainty and control.Footnote83 People rely on conspiracy theories to make sense of events, situations or circumstances by establishing simple and meaningful causal relationships between stimuli.Footnote84 This sense-making process makes people prone to exaggerate the hostile intentions of outgroups, which can lead to confirmation bias, distorted thinking and prejudice regarding outgroups. Conspiracy theories about outgroups that explain why individuals feel as they already do reassures these individuals that their feelings and concerns are justified, and that their hostility and prejudice toward the outgroup should continue.

This raises important policy questions: given that uncertainty is a key precursor of conspiracy beliefs and that it strengthens the relationship between outgroup threat and prejudice, how might governments and their agencies best address the emergence of conspiracy thinking? It is widely recognized that conspiracy beliefs are notoriously difficult to shift through counterargument and appeals to logic. For example, Sunstein and Vermeule state that conspiracy theories are “unusually hard to undermine or dislodge; they have a self-sealing quality, rendering them particularly immune to challenge”.Footnote85 Conspiracy theorists do not seek out those beliefs for their rationality, to be amended or replaced through the scientific method as soon as a better explanation becomes available. Rather, conspiracy beliefs—which are often unscientific and unprovable—are sought out in times of heightened uncertainty to reassert control and predictability, and to confirm perceived threats that are felt emotionally and implicitly. The conspiracy theories often demonize outgroups who are perceived as a threat on symbolic, terroristic or less often on realistic grounds. Direct efforts to counter these beliefs may cause conspiracy theorists to double down rather than to reflect openly and revise their views—hence their “self-sealing” nature.Footnote86 In a systematic review of the literature, O’Mahony et al. confirmed that most interventions to counteract entrenched conspiracy beliefs were ineffective. Instead, warning people ahead of time about a particular conspiracy theory or explicitly teaching them how to identify unreliable information before conspiracy beliefs took hold showed more promise.Footnote87

Hence, approaches that address the precursors to conspiracy belief formation compared to challenging established beliefs directly should be given priority. Governments may wish to challenge the outgroup threat perceptions that contribute to conspiracy thinking (symbolic and terroristic threat) and prejudice (symbolic and realistic threat). These may be more amenable to direct challenge than the conspiracy theories they produce. A second approach is for governments to address uncertainty as a driver of conspiracy beliefs. Governments cannot change world events or provide absolute certainty over all situations, but they can adopt strategies to minimize feelings of uncertainty during uncertain times. Clear and consistent public messaging, transparency and accountability and a preference for proactive strategies over reactive decision making, may all mitigate the conditions that lead individuals to seek out conspiracy beliefs. Additional government support to communities during uncertain times, even if provided for other specific and necessary reasons, may also have some indirect protective benefit. Especially when crises like high inflation, international conflicts/wars and mass refugee displacement continue for many years, such approaches may pay dividends in reducing drivers of conspiracy thinking and prejudice toward non-White immigrants over the long term.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Before concluding, our study’s limitations must be considered. First, our survey data were cross-sectional in nature (i.e., collected at one point in time). Thus, any causal relationships implied between the key variables in our study cannot be determined. For example, we proposed that outgroup threats should precede conspiracy belief formation, but our data do not preclude that conspiracy beliefs might precede outgroup threat perceptions. In order to tease out the causal direction of our theorized relationships, longitudinal or experimental methodologies should be considered to replicate our findings. Second, as we recruited participants through Facebook to maximize our chances of recruiting conspiracy believers this might limit the generalizability of our findings to the wider Australian population. Prior studies on conspiracy beliefs that have utilized representative samples have been criticized for not capturing sufficient numbers of conspiracy believers.Footnote88 Our data collection method ensured that this was not a problem, but whether our findings can be replicated beyond Australian Facebook users remains to be seen. Third, given our interest in the types of negative attitudes and beliefs espoused by White nationalists in Australia we measured belief in The Great Replacement conspiracy theory. We also focused on prejudice toward non-White immigrants. However, other conspiracies may be equally prevalent among those who are prejudiced toward non-White immigrants (e.g., the Zionist Occupation Government conspiracy, which is an antisemitic conspiracy theory that claims that Jews secretly control the governments of Western states). Future research may wish to consider alternative conspiracy theory beliefs, or other forms of prejudice toward different outgroups, to provide a more in-depth exploration of how outgroup threats, uncertainty and conspiracy beliefs shape prejudice more generally.

Conclusion

Our study aimed to understand how and why outgroup threat perceptions generate prejudice toward non-White immigrants. We examined the three widely recognized types of outgroup threat—realistic, symbolic and terroristic threat—and their relationship with prejudice. We explored whether belief in core aspects of The Great Replacement conspiracy theory that is often espoused by White nationalists could explain the relationship between outgroup threat and prejudice toward non-White immigrants among a general sample of White Australians. In addition, we examined whether this relationship was strengthened by heightened experiences of uncertainty. By studying these relationships we hoped to identify avenues to prevent more dangerous White nationalist attitudes from developing in the general population.

We found that conspiracy beliefs are crucial in explaining why perceived outgroup threat perceptions enhance prejudice toward non-White immigrants. This relationship is strongest among those who experience heightened feelings of uncertainty about society. These findings strengthen previous research showing that people seek out conspiracy theories as a sense-making process and to reassert feelings of control and predictability in an uncertain world.Footnote89

Our study suggests additional findings of interest to the field. One is that terroristic threat perceptions are linked with conspiracy belief, but not prejudice. Since the 11 September 2001 attacks, Islam and terrorism have often been conflated, leading to increased discrimination against Muslim populations.Footnote90 Our data suggest that such conflations, even if they result in conspiracy thinking about Muslim populations, are less likely to generate prejudice compared to realistic and symbolic threat perceptions. Symbolic threat appears to be the most concerning, as it relates both to higher conspiracy thinking and prejudice. Based on our data, White nationalist beliefs underpinned by symbolic threat, in contrast to similar beliefs based in realistic and terroristic perceptions, may provide the greatest source of risk. The risks posed by symbolic threats are consistent with a second key finding—that a notable and concerning percentage of respondents agreed with core Great Replacement beliefs. Efforts by governments and their agencies to address outgroup threat perceptions and minimize feelings of uncertainty in times of ongoing crisis may pay dividends over the long term by addressing the circumstances that lead people to seek out conspiracy beliefs in the first place. Ongoing research into those possibilities may prove valuable in reducing the threats that conspiracy thinking and dangerous forms of White nationalism pose to national and global security.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests or conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Lydia Khalil, Rise of the Extreme Right: The New Global Terrorism and the Threat to Global Democracy (Sydney: Penguin, 2022); Mario Peucker and Debra Smith, “Far-Right Movements in Contemporary Australia: An Introduction,” in The Far-Right in Contemporary Australia, ed. Mario Peucker and Debra Smith (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 19–52; Mike Burgess, “Director-General of Security: Annual Threat Assessment” (ASIO, Canberra, 2022), www.asio.gov.au/publications/speeches-and-statements/director-generals-annual-threat-assessment-2022.html (accessed 28 February 2022).

2 FBI, “State of Domestic White Nationalist Extremist Movement in the United States” (FBI, Washington, 2006), https://archive.org/details/foia_FBI_Monograph-State_of_Domestic_White_Nationalist_Extremist_Movement_in_the_U.S./page/n2/mode/1up?view=theater (accessed 17 May 2024).

3 Carol Swain, The New White Nationalism in America: Its Challenge to Integration (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

4 Mattias Gardell, “‘The Radicalisation of Western Man’: The Great Replacement, White Radical Nationalism, and Lone Wolf Violence,” in Radicalisation: A Global and Comparative Perspective, ed. James Lewis and Akil Awan (London: Hurst and Company, 2023).

5 Mattias Ekman, “The Great Replacement: Strategic Mainstreaming of Far-Right Conspiracy Claims,” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 28, no. 4 (2022): 1127–43; Milan Obaidi, Jonas Kunst, Simon Ozer, and Sasha Y. Kimel, “The “Great Replacement” Conspiracy: How the Perceived Ousting of Whites Can Evoke Violent Extremism and Islamophobia,” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 25, no. 7 (2022): 1675–95.

6 Peucker and Smith, “Far-Right Movements in Contemporary Australia.”

7 Michelle Grossman, Mario Peucker, Debra Smith, and Hass Dellal. Stocktake Research Project: A Systematic Literature and Selected Program Review on Social Cohesion, Community Resilience and Violent Extremism 2011–2015 (Melbourne: Victorian Government, 2016), 27.

8 Blake Riek, Eric Mania, and Samuel Gaertner, “Intergroup Threat and Outgroup Attitudes: A Meta-Analytic Review,” Personality and Social Psychology Review 10, no. 4 (2006): 336–53.

9 Walter Stephan and Cookie White Stephan, “An Integrated Threat Theory of Prejudice,” in Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination, ed. Stuart Oskamp (London: Psychology Press, 2000), 23–45; Macarena Vallejo-Martín, Jesús M. Canto, Jesús E. San Martín García, and Fabiola Perles Novas, “Prejudice towards Immigrants: The Importance of Social Context, Ideological Postulates, and Perception of Outgroup Threat,” Sustainability 13, no. 9 (2021): 4993.

10 Ingrid Johnsen Haas and William Cunningham, “The Uncertainty Paradox: Perceived Threat Moderates the Effect of Uncertainty on Political Tolerance,” Political Psychology 35, no. 2 (2014): 291–302; Jolanda Jetten, Kim Peters, and Bruno Casara, “Economic Inequality and Conspiracy Theories,” Current Opinion in Psychology 47 (2022): 101358.

11 Australian Bureau of Statistics, “Australia’s Population by Country of Birth,” Statistics on Australia’s Estimated Resident Population by Country of Birth (Australian Bureau of Statistics, last modified 31 October 2023), https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/australias-population-country-birth/2022 (accessed 30 November 2023).

12 James Jupp, From White Australia to Woomera: The Story of Australian Immigration (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

13 Ibid.

14 Peucker and Smith, “Far-Right Movements in Contemporary Australia: An Introduction”; Liberal Party of Australia and The Nationals, “The Coalition’s ‘Operation Sovereign Borders’ Policy” (Canberra: Liberal Party of Australia), https://web.archive.org/web/20160303211828/http://lpaweb-static.s3.amazonaws.com/Policies/OperationSovereignBorders_Policy.pdf (accessed 29 February 2024); Phivos Deliyannis, “The Securitization of the “Boat People” in Australia (Malmo: Malmo University, 2020); Kim Huynh, Australia’s Refugee Politics in the Twenty First Century: Stop the Boats! (New York: Routledge, 2023).

15 Thomas Pettigrew, George Fredrickson, Dale Knobel, Nathan Glazer, and Reed Ueda, Prejudice (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002).

16 Andrew Markus, Mapping Social Cohesion: The Scanlon Foundation Surveys 2017 (Victoria: Monash University, 2017), http://scanlonfoundation.org.au/socialcohesion2017/ (accessed 30 November 2023).

17 Huynh, Australia’s Refugee Politics in the Twenty First Century.

18 Vallejo-Martín et al., “Prejudice towards Immigrants.” Walter Stephan and Cookie White Stephan, “Intergroup Anxiety,” Journal of Social Issues 41 (1985): 157–66; Fatih Uenal, “Disentangling Islamophobia: The Differential Effects of Symbolic, Realistic, and Terroristic Threat Perceptions as Mediators between Social Dominance Orientation and Islamophobia,” Journal of Social and Political Psychology 4, no. 1 (2016): 66–90.

19 Anthony Greenwald and Thomas Pettigrew, “With Malice toward None and Charity for Some: Ingroup Favoritism Enables Discrimination,” American Psychologist 69, no. 7 (2014): 669–84; Kristina Murphy, Ben Bradford, Elise Sargeant, and Adrian Cherney, “Building Immigrants’ Solidarity with Police: Procedural Justice, Identity and Immigrants’ Willingness to Cooperate with Police,” The British Journal of Criminology 62, no. 2 (2022): 299–319.

20 Riek et al., “Intergroup Threat and Outgroup Attitudes”, 336.

21 Walter Stephan, Oscar Ybarra, and Guy Bachman, “Prejudice toward Immigrants,” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 29, no. 11 (1999): 2221–37; Petru Lucian Curşeu, Ron Stoop, and René Schalk, “Prejudice toward Immigrant Workers among Dutch Employees: Integrated Threat Theory Revisited,” European Journal of Social Psychology 37, no. 1 (2007): 125–40; Vallejo-Martín et al., “Prejudice towards Immigrants.”

22 Stephan and Stephan, “An Integrated Threat Theory of Prejudice”; Walter Stephan, Oscar Ybarra, Carmen Martnez Martnez, Joseph Schwarzwald, and Michal Tur-Kaspa, “Prejudice toward Immigrants to Spain and Israel: An Integrated Threat Theory Analysis,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 29, no. 4 (1998): 559–76.

23 Robert LeVine and Donald Campbell, Ethnocentrism: Theories of Conflict, Ethnic Attitudes, and Group Behavior (New York: Wiley, 1972); Muzafer Sherif, In Common Predicament: Social Psychology of Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1966).

24 Stephan et al., “Prejudice toward Immigrants to Spain and Israel”, 560.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Robert Schweitzer, Shelley Perkoulidis, Sandra Krome, Christopher Ludlow, and Melanie Ryan, “Attitudes towards Refugees: The Dark Side of Prejudice in Australia,” Australian Journal of Psychology 57, no. 3 (2005): 170–79.

30 Karina Velasco González, Maykel Verkuyten, Jeroen Weesie, and Edwin Poppe, “Prejudice towards Muslims in the Netherlands: Testing Integrated Threat Theory,” British Journal of Social Psychology 47, no. 4 (2008): 667–85.

31 Bertjan Doosje, Anja Zimmermann, Beate Küpper, Andreas Zick, and Roel Meertens, “Terrorist Threat and Perceived Islamic Support for Terrorist Attacks as Predictors of Personal and Institutional Out-Group Discrimination and Support for Anti-Immigration Policies—Evidence from 9 European Countries,” Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale 22, no. 3 (2009): 203–33; Uenal, “Disentangling Islamophobia.”

32 Ibid.

33 Uenal, “Disentangling Islamophobia.”

34 Samuel Gaertner and John Dovidio, Prejudice, Discrimination and Racism: Problems, Progress and Promise (Orlando: Academic Press, 1986).

35 Richard Moulding, Simon Nix-Carnell, Alexandra Schnabel, Maja Nedeljkovic, Emma Burnside, Aaron Lentini, and Nazia Mehzabin, “Better the Devil You Know Than a World You Don’t? Intolerance of Uncertainty and Worldview Explanations for Belief in Conspiracy Theories,” Personality and Individual Differences 98 (2016): 345–54; Elżbieta Kużelewska and Mariusz Tomaszuk, “Rise of Conspiracy Theories in the Pandemic Times,” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law-Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique 35, no. 6 (2022): 2373-89; Jan-Willem Van Prooijen, and Karen Douglas, “Conspiracy Theories as Part of History: The Role of Societal Crisis Situations,” Memory Studies 10, no. 3 (2017): 323–33.

36 Fatih Uenal, “The Secret Islamization of Europe Exploring the Integrated Threat Theory: Predicting Islamophobic Conspiracy Stereotypes,” International Journal of Conflict and Violence (IJCV) 10 (2016): 93–108.

37 Karen Douglas, Robbie Sutton, and Aleksandra Cichocka, “The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 26, no. 6 (2017): 538–42; Jan-Willem van Prooijen and Karen Douglas, “Belief in Conspiracy Theories: Basic Principles of an Emerging Research Domain,” European Journal of Social Psychology 48, no. 7 (2018): 897–908; Uenal, “The Secret Islamization of Europe.”

38 Jan-Willem van Prooijen and Karen Douglas, “Belief in Conspiracy Theories: Basic Principles of an Emerging Research Domain”; Douglas et al., “The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories”; Uenal, “The Secret Islamization of Europe.”

39 Daniel Jolley, Rose Meleady, and Karen Douglas, “Exposure to Intergroup Conspiracy Theories Promotes Prejudice Which Spreads across Groups,” British Journal of Psychology 111, no. 1 (2020): 17–35; Anni Sternisko, Aleksandra Cichocka, and Jay Van Bavel, “The Dark Side of Social Movements: Social Identity, Non-Conformity, and the Lure of Conspiracy Theories,” Current Opinion in Psychology 35 (2020): 1–6; Cass Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule, “Conspiracy Theories: Causes and Cures,” Journal of Political Philosophy 17, no. 2 (2009): 202–27. Jamie Bartlett and Carl Miller, The Power of Unreason: Conspiracy Theories, Extremism and Counter-Terrorism (London: Demos, 2010).

40 Agnieszka Golec de Zavala and Aleksandra Cichocka, “Collective Narcissism and Anti-Semitism in Poland: The Mediating Role of Siege Beliefs and the Conspiracy Stereotype of Jews,” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 15, no. 2 (2012): 213–29; Miroslaw Kofta and Grzegorz Sedek, “Conspiracy Stereotypes of Jews during Systemic Transformation in Poland,” International Journal of Sociology 35, no. 1 (2005): 40–64.

41 Jolley et al., “Exposure to Intergroup Conspiracy Theories Promotes Prejudice Which Spreads across Groups.”

42 Bartlett and Miller, The Power of Unreason. Sara Kamali, “White Nationalism Is a Political Ideology That Mainstreams Racist Conspiracy Theories,” The Conversation (September 2022). https://theconversation.com/white-nationalism-is-a-political-ideology-that-mainstreams-racist-conspiracy-theories-184375 (accessed 17 May 2024).

43 Kamali, White Nationalism Is a Political Ideology; Bartlett and Miller, The Power of Unreason; Alexander Jedinger, Lena Masch, and Axel Burger, “Cognitive Reflection and Endorsement of the “Great Replacement” Conspiracy Theory,” Social Psychological Bulletin 18 (2023): 1–12.

44 Gabriele Cosentino, Social Media and the Post-Truth World Order: The Global Dynamics of Disinformation (Berlin: Springer Nature, 2020).

45 Serge Moscovici, “The Conspiracy Mentality,” in Changing Conceptions of Conspiracy, ed. Carl Graumann and Serge Moscovici (New York: Springer, 1987), 151–69.

46 Uenal, “The Secret Islamization of Europe.”

47 Ibid.

48 Obaidi et al., “The Great Replacement Conspiracy.”

49 Ibid.

50 Uenal, “The Secret Islamization of Europe.”

51 Jan-Willem Van Prooijen, “An Existential Threat Model of Conspiracy Theories,” European Psychologist 25, no. 1. (2019): 16–25.

52 Jolley et al., “Exposure to Intergroup Conspiracy Theories Promotes Prejudice Which Spreads across Groups.”

53 Marina Abalakina-Paap, Walter Stephan, Traci Craig, and W. Larry Gregory, “Beliefs in Conspiracies,” Political Psychology 20, no. 3 (1999): 637–47; Martin Bruder, Peter Haffke, Nick Neave, Nina Nouripanah, and Roland Imhoff, “Measuring Individual Differences in Generic Beliefs in Conspiracy Theories across Cultures: Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire,” Frontiers in Psychology 4 (2013): 225; Monika Grzesiak-Feldman, “The Effect of High-Anxiety Situations on Conspiracy Thinking,” Current Psychology 32 (2013): 100–18; Jetten et al., “Economic Inequality and Conspiracy Theories”; Małgorzata Kossowska and Marcin Bukowski, “Motivated Roots of Conspiracies: The Role of Certainty and Control Motives in Conspiracy Thinking,” in The Psychology of Conspiracy, eds. Michal Bilewicz, Aleksandra Cichocka, and Wiktor Soral (London: Routledge, 2015), 145–61; Van Prooijen and Douglas, “Conspiracy Theories as Part of History.”

54 Kossowska and Bukowski, “Motivated Roots of Conspiracies.”

55 Haas and Cunningham, “The Uncertainty Paradox.”

56 Van Prooijen, “An Existential Threat Model of Conspiracy Theories.”

57 Ibid.

58 Ibid., 94.

59 Ibid.

60 Kossowska and Bukowski, “Motivated Roots of Conspiracies”, 146.

61 Van Prooijen, “An Existential Threat Model of Conspiracy Theories.”

62 Douglas et al., “The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories.”

63 Uenal, “The Secret Islamization of Europe Exploring the Integrated Threat Theory”; Jolley et al., “Exposure to Intergroup Conspiracy Theories Promotes Prejudice Which Spreads across Groups.”

64 Michal Bilewicz and Ireneusz Krzeminski, “Anti-Semitism in Poland and Ukraine: The Belief in Jewish Control as a Mechanism of Scapegoating,” International Journal of Conflict and Violence (IJCV) 4, no. 2 (2010): 234–43.

65 Ali Mashuri and Chad Osteen, “Threat by Association, Islamic Puritanism and Conspiracy Beliefs Explain a Religious Majority Group’s Collective Protest Against Religious Minority Groups,” Psychology and Developing Societies 35, no. 1 (2023): 169–96.

66 Ibid.

67 Ibid.

68 Bilewicz and Krzeminski, “Anti-Semitism in Poland and Ukraine”; Mashuri and Osteen, Ibid.

69 Amelie Nickel, “Institutional Anomie, Market-Based Values and Anti-Immigrant Attitudes: A Multilevel Analysis in 28 European Countries,” International Journal of Conflict and Violence (IJCV) 16 (2022); Dario Padovan and Alfredo Alietti, “The Racialization of Public Discourse: Antisemitism and Islamophobia in Italian Society,” European Societies 14, no. 2 (2012): 186–202; John Western and Andrea Lanyon, “Anomie in the Asia Pacific Region: The Australian Study,” in Comparative Anomie Research: Hidden Barriers – Hidden Potential for Social Development, ed. Peter Atteslander, Bettina Gransow, and John Western (London: Routledge, 1999), 73–98.

70 Axel Bruns, Stephen Harrington, and Edward Hurcombe, “Corona? 5G? or Both?’: The Dynamics of COVID-19/5G Conspiracy Theories on Facebook,” Media International Australia 177, no. 1 (2020): 12–29.

71 Stephan et al., “Prejudice toward Immigrants to Spain and Israel.”

72 Ibid.; Obaidi et al., “The “Great Replacement” Conspiracy.”

73 Uenal, “Disentangling Islamophobia.”

74 Ali Teymoori, Jolanda Jetten, Brock Bastian, Amarina Ariyanto, Frédérique Autin, Nadia Ayub, Constantina Badea, Tomasz Besta, Fabrizio Butera, Rui Costa-Lopes, et al. “Revisiting the Measurement of Anomie,” PLoS One 11, no. 7 (2016): e0158370; Molly McCarthy, Kristina Murphy, Elise Sargeant, and Harley Williamson, “Examining the Relationship between Conspiracy Theories and COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: A Mediating Role for Perceived Health Threats, Trust, and Anomie?” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 22, no. 1 (2022): 106–29.

75 Obaidi et al., “The “Great Replacement” Conspiracy.”

76 Harley Williamson, Kristina Murphy, and Elise Sargeant, The Attitudes to Punishment Survey Wave 1 Technical Report (Brisbane: Griffith University, 2018).

77 Stephan et al., “Prejudice toward Immigrants to Spain and Israel”; Schweitzer et al., “Attitudes towards Refugees”; Velasco González et al., “Prejudice towards Muslims in the Netherlands.”

78 Stephan et al., “Prejudice toward Immigrants to Spain and Israel.”

79 Uenal, “Disentangling Islamophobia.”

80 Uenal, “The Secret Islamization of Europe”; Bilewicz and Krzeminski, “Anti-Semitism in Poland and Ukraine.”

81 Uenal, “Disentangling Islamophobia”; Samuel P. Huntington, “The Clash of Civilisations?” in The New Social Theory Reader, ed. Steven Seidman and Jeffrey Alexander (London: Routledge, 2008), 305–14.

82 Jolley et al., “Exposure to Intergroup Conspiracy Theories Promotes Prejudice Which Spreads across Groups”; Van Prooijen and Douglas, “Conspiracy Theories as Part of History”; Jetten et al., “Economic Inequality and Conspiracy Theories.”

83 Kossowska and Bukowski, “Motivated Roots of Conspiracies.”

84 Van Prooijen, “An Existential Threat Model of Conspiracy Theories.”

85 Sunstein and Vermeule, “Conspiracy Theories: Causes and Cures”, 204.

86 Ibid.

87 Cian O’Mahony, Maryanne Brassil, Gillian Murphy, and Conor Lineman, “The Efficacy of Interventions in Reducing Belief in Conspiracy Theories: A Systematic Review.” PLoS One 18, no. 4 (2023): e0280902.

88 Karen Douglas and Robbie Sutton, “Why Conspiracy Theories Matter: A Social Psychological Analysis,” European Review of Social Psychology 29, no. 1 (2018): 256–98.

89 Van Prooijen, “An Existential Threat Model of Conspiracy Theories.”

90 Uenal, “Disentangling Islamophobia”; Uenal, “The Secret Islamization of Europe.”