ABSTRACT

This article investigates the relationship between elite power sharing and media freedom in dictatorships. While conventional wisdom posits that dictators have a strong incentive to control the media, they also need information to sustain their authoritarian rule. In this article, we argue that dictators need to allow for a higher level of media freedom when sharing more power with other elites. Specifically, dictators create transparency through media freedom to induce trust and cooperation among elites within the regime. We confirm the hypothesis by analyzing data from 98 dictatorships from 1960 to 2010. Our finding is robust to different model specifications. This article contributes to the literature by showing that authoritarian media freedom is determined by not only dictators’ need for local information as the conventional wisdom suggests, but also the power dynamics within their ruling coalitions.

Introduction

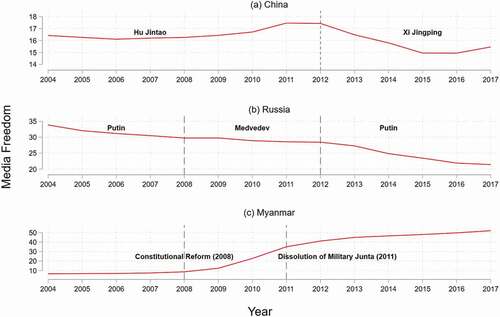

While every dictator has a strong incentive to control the media, it is unclear whether the intra-elite power-sharing within the ruling coalition affects the level of media freedom in authoritarian regimes. Several recent examples seem to suggest that it does. The developments in China’s political landscape under President Xi Jinping provide a motivating example. Since Xi took office in 2012, he has not only concentrated an immense amount of power in his own hands through various political maneuvers such as the anti-graft campaign that aims to crack down on both high-level and local officials abusing their power and/or were involved in corruption, but also adopted draconian measures to limit freedom of the media, both state-run and private (Shirk Citation2018). As Solis and Waggoner (Citation2020) index of media freedom indicates (see ), while media freedom in China has long been suppressed by the regime, we can still observe a stark contrast in media freedom between the Hu Jintao and the Xi Jinping eras. Another prominent example where the personalization of power leads to less media freedom is Russia under Putin. It is even more striking to see how Putin’s power grab through personalistic patronalism since he succeeded Yeltsin (Hale, Citation2017) is associated with a nonstop plunge in Russia’s media freedom rating (see ).

Figure 1. Media freedom in China, Russia, and Myanmar, 2004–2017.

Recently, we witnessed similar dynamics in Myanmar, where the military coup of February 2021 not only destroyed the intra-elite power-sharing arrangements created since the 2008 constitutional reform, but also led to more suppression of media freedom. What is interesting about the Myanmar case is that it substantiates the same proposition in the opposite direction. It was only a decade ago when the long-time opposition leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, and her party, the National League for Democracy (NLD) joined with the military to form a coalition government through the 2012 by-elections (Bünte, Citation2018). This shift in the intra-elite balance of power came with a relaxation of control over the media. According to , there had been a substantial increase in media freedom in Myanmar since 2008 – all the way from lower than 10 in 2008 to more than 50 in 2017.

These cases present an interesting pattern where, despite the lack of any major momenta for a regime transition, the level of media freedom in a dictatorship might go up or down depending on whether there is more or less power sharing within the ruling coalition. In particular, one wonders why, since media control is vital for sustaining dictators’ authoritarian rule, they would relax it after they began to share more power with their allies.

The current literature on authoritarian media freedom, however, is ill-positioned to explain these cases. While existing studies do tell us that a dictator sometimes strategically allows more media freedom to obtain information useful for maintaining regime stability (Egorov et al., Citation2009; Lorentzen, Citation2014; Qin et al., Citation2017; Repnikova, Citation2017), the literature’s assumption of the state being a unitary actor vis-à-vis society makes it less sensitive to how a shift in the balance of power within the ruling coalition might affect the media policy in such a regime. As a matter of fact, absent any dramatic increase (or decrease) in a regime’s capacity to monitor its society, there is no way for the literature to predict any changes in the levels of media freedom in China under Xi or Russia under Putin given their shared need for information to be responsive.

To fill this gap, we argue in this article that more (or less) power sharing among elites leads to a higher (lower) degree of media freedom. The argument draws upon the recent studies on comparative authoritarianism. In particular, authoritarian regimes are closed with very limited information flows, but their political leaders also need information to sustain their authoritarian rule. Meanwhile, other political elites need information to make sure that the ruling coalition is stable and the dictator does not collude with some elites against others. To overcome this information problem, authoritarian elites create political institutions within which they can observe each other’s activities and constrain the dictator’s power to distribute benefits (Boix & Svolik, Citation2013). Based on this insight, we argue that the media, even when only partially free, play a similar role in enhancing regime transparency. A transparent political environment within the ruling coalition is particularly helpful for authoritarian elites to assign accountability and sustain the status quo of power sharing among elites when there are external shocks or crises to the coalition. When dictators share more power with elites, they need to make the information environment more transparent as a way to seek support from their allies. In short, more power sharing between the dictator and ruling elites leads to more media freedom. We elaborate our argument in the following section.

A Theory of Media Freedom under Dictatorships

Authoritarian Media Control

Authoritarian leaders exercise their control over the media in two main ways. On the one hand, they control the management and staffing of media outlets. For example, through the Soviet-style nomenklatura established within the Chinese media, the Chinese authorities are able to control directly who the managers and editors will be (Brady, Citation2017). Moreover, through selective promotion of those journalists who are willing to cooperate with the authorities, dictators are also able to control the content of news reports (Lee & Chan, Citation2009). On the other hand, apart from personnel control, authoritarian leaders are also able to exercise their control through censorship. For example, in the USSR, Glavlit censored media reports following the instructions and regulations proposed by the central government and made decisions based on the ideological line of the Communist Party. Published works could be retracted at Glavlit’s discretion, both post-publication and pre-distribution (Lauk, Citation1999). Media censorship can also be implemented by limiting the circulation of newspapers. For example, before 2011 in Myanmar, only state media outlets were allowed to publish on a daily basis, while non-state ones could only publish weekly. Therefore, media freedom under dictatorships can be enhanced when both restrictions are relaxed. In the following sections, we explain why dictators are willing to relax them not only for obtaining more information on the ground, but also for sustaining the power-sharing relationship with their allies inside the ruling coalition.

Power Sharing and Dictatorships

Students of dictatorships have long noticed the importance of power-sharing arrangements or patronage distribution in authoritarian politics when dictators are not strong enough to monopolize power. As Bueno de Mesquita et al. (Citation2003, pp. 28–29) have succinctly summarized, “Make no mistake about it, no leader rules alone. Even the most oppressive dictators cannot survive the loss of support among their core constituents.” In other words, just like their democratic counterparts, the leaders of authoritarian countries are not exempt from making compromises and cutting deals with their core constituents to form a ruling coalition. This is why, roughly two decades ago, an earlier study on dictatorships by Wintrobe (Citation1998, p. 336) drew such an analogy: “If democracy may be likened to a pork barrel, the typical dictatorship is a warehouse or temple of pork.” In short, one key factor to sustaining dictators’ authoritarian rule is their sharing of power and resources with their allies.

Based on this insight, the recent literature on authoritarian institutions takes the argument a step further and shows that authoritarian regimes are able to live longer (Brownlee, Citation2007; Magaloni, Citation2008), attain higher economic growth rates (Gandhi, Citation2008), deliver greater human development (Miller, Citation2015), and induce more investment (Gehlbach & Keefer, Citation2011) when such a power-sharing relationship can be institutionalized through elections, legislatures, or political parties. If elite power sharing is so critical to all the important political-economic outcomes listed above, how can such cooperation be sustained? To answer this question, Boix and Svolik (Citation2013) argue that it is the institutionally-induced transparency that brings stability to the power-sharing relationship and minimizes potential conflicts among them. Specifically, such transparency is created through establishing political institutions such as parties and legislatures, where both dictators and their allies can monitor how resources are distributed during both normal times and crises. As crises could undermine dictators’ capacity to distribute resources to their allies and destabilize the ruling coalition, Casper (Citation2017, p. 967), for instance, demonstrates that countries joining the International Monetary Fund (IMF) programs are more likely to experience coups than those who do not because the IMF programs “heavily reduce a leader’s capacity to redistribute wealth.” Thus, when dictators face such a risk from their allies, they need to increase the transparency of distributive policies to convince their allies that the shortfall of redistribution is attributed to external shocks, not their breakup of the power- and resource-sharing agreements. In other words, transparency strengthens the former’s commitment to the latter by reducing “the misperception about the dictators’ compliance with a power-sharing agreement” and “avert unnecessary rebellions” from other ruling elites (Boix & Svolik, Citation2013, p. 301; Casper & Tyson, Citation2014). Furthermore, transparency helps dictators detect threats to regime stability by disclosing the misconduct or corruption of other elites (Egorov et al., Citation2009; Lorentzen, Citation2014; Lu & Ma, Citation2019; Malesky & Schuler, Citation2010).Footnote1

Media Freedom and Power-Sharing under Dictatorships

The argument that political institutions increase regime transparency and stabilize the power-sharing status quo in dictatorships highlights the need of information between authoritarian leaders and their allies. In addition to political institutions, this paper enriches this informational argument by expanding its scope to include the media for a similar role in enhancing transparency among political elites and sustaining the authoritarian ruling coalitions. While there is no denying that dictators and their allies do collude to hide undesirable information that could undermine the regime survival by manipulating the media (Guriev & Treisman, Citation2019; Malesky et al., Citation2011), media freedom, even just partial, can actually help them strengthen their political bond.

How exactly does media freedom work to help maintain authoritarian stability? As Bueno de Mesquita et al. (Citation2003) point out nicely, the larger a dictator’s winning coalition becomes, the more difficult it will be for them to recruit coalition members through their private wealth. Instead, they will need to rely more on the provision of public goods. In other words, when we argue that media freedom could make intra-elite power sharing more transparent, we do not mean that media outlets would have access to the details of such power sharing or that they would be allowed to report on it. What is actually brought to light through media freedom in the form of news reports, however, are policy outcomes that would affect the consensual distribution of resources between dictators and their allies. While reporting on public goods provision is not necessarily exempt from political interventions under dictatorships, it is not something totally exclusive to regime insiders. Accordingly, media outlets do not have to know precisely how intra-elite power sharing works to report on things that would be useful for all elite members of the winning coalition to monitor if their implicit pact is violated. While the “inner workings” of the ruling coalition are inevitably elusive, the policies that would affect the distribution of public goods among elites are not. Granting media outlets freedom can provide both dictators and their allies with the information they need.

One good example of how our theoretical logic plays out in high-level politics is the purge of one of China’s former politburo members, Chen Liangyu, in 2006. The case tells us how the transparency provided by media freedom helped consolidate the power-sharing framework among Chinese elites when some of them tried to shift the original power balance of the regime. As a member of the Politburo Standing Committee and the party secretary of Shanghai, Chen was one of the leaders of a very powerful political faction, the Shanghai Gang, led by Jiang Zemin, a former president who still enjoyed substantial political influence after his retirement in 2002. As a leader of a major faction against the then president, Hu Jintao, Chen not only openly confronted the central government by frequently defying its policies, but also engaged in corrupt practices locally to obtain personal political benefits (Li, Citation2007). While it was not until 2006 that Hu Jintao fired Chen and began a criminal investigation into his case, it should be noted that Chen’s violation of the implicit power-sharing pact among the Chinese elites had already been exposed by a media outlet, the China Business Journal, in August 2003 (Bai, Citation2015; Pei, Citation2006). The report did not touch on the power-sharing arrangement among the ruling elites, but only focused on how the Shanghai government failed to abide by the central policy on land sales. The very fact that such a case of potential corruption implicating a member of the Politburo Standing Committee could be reported shows the level of media freedom at the time and how it could help recalibrate the political equilibrium back to its original status. Counterfactually, without such transparency resulting from media freedom, the regime would have been less stable.

In addition, recent studies on China’s local politics offer good examples about how the media, even just partially free, enable authoritarian elites to identify and defuse potential challenges to the regime. By analyzing the data of commercial newspapers, Lu and Ma (Citation2019, p. 68) find that the politicians in China’s Party Congress who received more coverage in commercial media outlets were less likely to be promoted to higher positions. The commercial media, unlike their state-own counterparts, need to maximize readership (Stockmann, Citation2013), and therefore are more interested in reporting politicians’ misconduct or violations of party norms. These non-normal yet newsworthy reports “are perceived as potential threats to the power-sharing status quo by the peer elites within the CCP regime” (Lu & Ma, Citation2019, p. 68). Consequently, politicians receiving more coverage in the commercial media are less likely to be promoted. This finding implies that a partially free media environment helps authoritarian elites sustain the power sharing structure via collecting information to sanction their nonconformist peers.

Instead of looking at the commercial media, Chen and Hong (Citation2020) find alternatively that authoritarian elites would use the government-owned media to attack their peers, especially those who are from the same factions within the CCP. In particular, local government-controlled newspapers in one province report more negative news stories involving corruption investigations and large-scale industrial incidents of other provinces, especially when the leaders of the reported provinces belong to the same faction. This reporting strategy results from the intra-faction competition within the CCP. With their control over provincial newspapers, local officials have strong incentive to hide negative information about their governance. Nevertheless, the promotion incentive of politicians in other provinces induces them to use their media to disclose the misconducts of their peers. Chen and Hong (Citation2020) also find that the promotion probabilities of the reported politicians decrease while those of the reporting ones increase. In other words, the transparency brought about by the local media helps top leaders assign accountability to their subordinates and maintain regime stability.

Media Freedom, Protests, and Solidarity among Authoritarian Elites

As transparency induces regime stability in dictatorships, Hollyer et al. (Citation2018) further argue that some dictators may even intentionally increase regime transparency to facilitate popular protests that may lead to the collapse of the authoritarian coalition.Footnote2 Their insight is that when threats to their coalition become more visible in authoritarian regimes, elites become more cohesive to resist those external threats. Therefore, dictators with more consolidated power, personalist ones in particular, would be less likely to disclose information about the regime than their counterparts with more power sharing (Svolik, Citation2009).

What should be emphasized here, however, is that a transparent environment would prevent unnecessary coups between dictators and their allies, thereby stabilizing their ruling coalitions. In particular, Casper and Tyson (Citation2014, p. 558) argue that higher levels of media freedom in dictatorships make elites “less likely to misjudge the actions of other elites, and hence they correctly coordinate with their compatriots to overthrow the leadership whenever they can succeed and correctly coordinate to support the leadership whenever they cannot.” Similarly, Stein (Citation2016) also finds that media–state interactions under an authoritarian regime are used as a barometer by activists for gauging the government’s tolerance of mass actions and their safety. A related but different argument by Boleslavsky et al. (Citation2021) also suggests that allowing media freedom could increase the likelihood of regime survival. They argue that freer media may, on the one hand, dissuade citizens from protesting, or, on the other hand, mobilize them to protest for restoring a leader who has been toppled by a coup.

As a final note, according to our argument, all members of the coalition need media freedom to maintain the coalition’s stability and the final level of media freedom is a political equilibrium co-determined by dictators and their allies. Both parties are therefore important actors in shaping the media environment in dictatorships. It also implies that elites are by no means “bystanders.” Their actions, together with those of the dictators, set the level of media freedom in their regimes. Depending on the level of power sharing in a given regime, political elites choose an optimal level of media freedom that makes the distribution of resources among them transparent and allows them to monitor violations of the implicit pact. As studies on authoritarian institutions tells us, some dictatorships succeed in creating institutions (legislatures, parties, elections, etc.) involving political elites. In these cases, decisions on media freedom will be made inside formal institutions. China’s Communist Party Congress and Politburo, Jordan’s parliament, and Myanmar’s coalition cabinet and People’s Assembly are good examples. For authoritarian regimes that are less institutionalized, the bargaining over media freedom will take place more informally among elites.Footnote3 However, we do not assume an equal distribution of power among members of the coalition. A leader may share power with many elites, and some of them may be much stronger than others. What is important is that, if dictators share more power with other members of their coalitions, the level of media freedom also increases regardless of how that power is distributed.

Based on our discussions in this section, we test the following hypothesis on authoritarian media freedom: An authoritarian regime in which the dictator has a higher level of power sharing with his or her allies will allow greater media freedom.

Research Design

Data

To test our hypothesis, we compiled a dataset of 98 dictatorships from 1960 to 2010. Our observation ends at 2010 because it is the last year of observation of our key explanatory variable, Power Sharing, in the dataset on authoritarian regimes constructed by Geddes et al. (Citation2018).Footnote4 Table A.1 and Table A.2 in the online supplementary materials list the dictatorships and variables analyzed in this article, respectively.

Dependent Variable

We use the Media System Freedom (MSF) data constructed by Solis and Waggoner (Citation2020) as a proxy for media freedom. Using an item response theory model, Solis and Waggoner (Citation2020) treat media freedom as a latent variable and utilize 10 existing indices on media freedom to construct their MSF measurement on a unidimensional scale from 0 to 1, with a higher value indicative of more media freedom for a country-year observation. The MSF dataset covers 197 countries for the years 1948–2017. We exclude observations of democratic regimes based on the data on authoritarian regimes constructed by Geddes et al. (Citation2018). For ease of interpretation, we multiply the Solis-Wagoner index of media freedom by 100. In robustness checks, we use alternative measures of media freedom, including the press freedom index constructed by Freedom House, the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) indices on freedom of expression and government efforts on the Internet censorship (Coppedge et al., Citation2021), and Whitten-Woodring and Van Belle (Citation2017) Global Media Freedom Dataset on media environment. Our main results remain unchanged when we use these alternative measures.

Key Explanatory Variable

We use the personalism variable constructed by Geddes et al. (Citation2018) as a measure of power sharing in dictatorships. According to Geddes et al. (Citation2018, pp. 70–71), personalist rule indicates that “the dictator has personal discretion and control over the key levers of power in his political system.” For a long time, scholars developed typologies for dictatorship according to which some regimes were classified as “personalist” as opposed to other types (Geddes et al., Citation2014). As contended by Hadenius and Teorell (Citation2007), however, all authoritarian regimes exhibit different degrees of personalism and therefore calling some of them personalist simply makes us blind to “personalization” and its effects in supposedly non-personalist regimes. By considering eight dimensions related to how an authoritarian leader’s power is constrained by political institutions and their power-sharing relationship with other elites, Geddes et al. (Citation2018) use an IRT model to construct a measure of personalism. One major advantage of this measure is that it captures the within-variation of dictators’ personalization of power across different dictatorships. Every authoritarian regime in their dataset has a country-year observation for the degree of personalization: a “process of concentrating power in the hands of a leader within a regime” (Frantz et al., Citation2020, p. 373). The original measure of personalism is normalized and ranges from 0 to 1. As our focus is how a higher level of power sharing leads to more media freedom, we create a new variable of power sharing by reversing the measure of personalism.Footnote5 We multiply this new measure by 100 for ease of interpretation. Plotting the mean values of media freedom against power sharing for authoritarian regimes in our sample, as shown in , offers preliminary support for our hypothesis.

Figure 2. Power sharing and media freedom, 1960–2010.

Control Variables

Following Egorov et al. (Citation2009), we include a set of control variables in our analysis. First, we include a country’s logged GDP per capita (in constant 2005 US dollars, taken from the World Development Indicators) to control for the effect of economic development on media freedom. We expect it to be positively associated with media freedom because economic actors, including individuals and private companies, prefer information about business and the economic environment not to be distorted by the government.

Second, we include the endowment of natural resources. Authoritarian regimes endowed with scarce natural resources, such as oil or natural gas, are more likely to allow media freedom to address the issue of information asymmetry between dictators and the bureaucrats who work for them (Egorov et al., Citation2009). In particular, dictators with scarce natural resources are less able to improve the quality governance by offering public goods than their counterparts endowed with more natural resources. Nevertheless, they can enhance their quality of governance by putting local officials under the media’s watch. In short, the media help dictators to deter local bureaucrats from shirking. Thus, we include the logarithmic values of revenues from exporting oil and gas (Ross & Mahdavi, Citation2015). We expect the sign of this variable to be negative.

Third, we control for an authoritarian regime’s domestic instability. Governments facing internal conflicts like to control the flow of information to prevent their legitimacy from being challenged (Stier, Citation2015, p. 1283). In addition, when an authoritarian regime is experiencing more domestic conflict, the political environment becomes more dangerous and it becomes more difficult for the media to conduct investigations and file reports that are subject to government intervention. Accordingly, we control for the number of conflicts facing an authoritarian regime in the observed year based on the data of Marshall (Citation2017).

Fourth, we consider a country’s size by including a variable of logged population in our analysis. Stier (Citation2015, p. 1283) argues that a larger population indicates a larger market, so the government has a stronger incentive “to nationalize media outlets and absorb profits from advertisement revenues.” Egorov et al. (Citation2009) suggest that dictators impose more censorship if their countries have a larger population. The intuition is that citizens of a country with a large population are more likely to rely on the media to overcome the problem of collective action against the dictator. Thus, the dictator in such a country will be more likely to censor the media.

Fifth, we consider the effect of democratic development on media freedom by including a country’s Polity score, which measures key features of a political regime, such as the competitiveness of executive recruitment and political participation. We include this variable for two reasons. First, Egorov et al. (Citation2009) claim that this measure is the best available proxy for democratic constraints on the dictator. As dictators are less constrained, they will be more likely to suppress media freedom. Second, the media may have more freedom to report if a dictatorship is democratizing. Thus, we include Polity scores to control for the levels of democratic development. It should be noted that the variables of Polity score and power sharing measure different dimensions of authoritarian politics. As recently reported by Wright (Citation2021, p. 7), the measure of personalism/power sharing is “not highly correlated with any of the democracy sub-components” (emphasis original), including those of the Polity IV or V-Dem projects. In particular, the measure of personalism investigates eight characteristics of autocratic rule, and two among them are “whether the regime leader personally controls key organizations in the security apparatus” and “whether the leader has discretion over appointment to high office.” Dictators have more personal power if they have full control over the appointments of security apparatus and high offices. Accordingly, the correlation between Polity score and power sharing is only −0.21 in our sample. The low correlation not only makes collinearity a less serious issue in our analysis, but also indicates that the measure of power sharing captures other characteristics overlooked by the Polity score. Accordingly, we include both variables in our empirical analysis.

Sixth, a repressive autocratic regime would be likely to inhibit media freedom. Thus, we include a variable measuring a country’s level of repression, which is operationalized with the inverse of a country’s protection of human rights (Fariss, Citation2014; Frantz et al., Citation2020). We expect a higher level of state repression to be associated with a lower level of media freedom.

Main Results

To test our hypothesis, we estimate a series of regression models with different specifications and report the results in . We follow Egorov et al. (Citation2009) and use the lead (t + 1) of media freedom as the dependent variable in all models. This practice is mathematically equivalent to lagging all independent variables by 1 year (t-1) but keeps the observations for 2010. In Model 1, we estimate a bivariate linear regression model. The result of this simple model suggests the level of power sharing is positively correlated with the level of media freedom. This result holds after we include other variables with country-fixed effects in Model 2 and additional year-fixed effects in Model 3. Substantively, one standard deviation increase in power sharing leads to a 0.087 standard deviation increase in the index of media freedom, while one standard deviation increase in Polity score leads to a 0.403 standard deviation increase. In other words, the effect of power sharing on media freedom is about 21.5% of the effect of a country’s Polity score on media freedom.Footnote6

Table 1. Power sharing and media freedom in dictatorships, 1960–2010

Being fully aware of the dynamic structure of our panel data, we adopt two empirical strategies to deal with the issue of serial correlation. In Model 4, we estimate a two-way fixed-effects model with heteroskedasticity- and autocorrelation-consistent (HAC) standard errors. Additionally, we estimate a fixed-effect model with an AR(1) disturbance (Model 5). Our key finding remains unchanged in both models.Footnote7

The confrontation between the West and the communist countries significantly shaped these countries’ political development and media environment during the Cold War. Both camps used propaganda and censorship to stabilize their political regimes and promote their political ideologies. As indicated by Henry A. Grunwald (Citation1993), a former editor-in-chief of Time magazine, the collapse of the Soviet Union opened a new window for communist countries to rearrange their political structure and media environment. In Model 6 in , we control for the possible moderating effect of the Cold War on the relationship between power sharing and media freedom. The results suggest that dictatorships on average had lower levels of media freedom during the Cold War era. In addition, the positive signs of Power Sharing and Power Sharing X Cold War suggest that increases in power sharing are associated with more media freedom during the Cold War than they are in the post-Cold War era.

Robustness Checks

For robustness, we estimate additional models using alternative measurements of media freedom from other sources. First, we use the Freedom House’s Press Freedom Index as a proxy for media freedom. This index measures the degree of print and broadcast media freedom in more than 150 countries and territories. It focuses on the media’s ability to provide and access news and information without being tampered with by political and economic forces. The original index of press freedom ranges from 0 to 100, with a higher number indicative of less media freedom. For ease of interpretation, we reverse the index by subtracting it from 100. Thus, a higher value of this new variable indicates more media freedom. Because there are many missing values of this variable for the Cold War era, and Freedom House changed its categorical measure of press freedom to a continuous one after 1993, we only use the post-1993 data when estimating Model 1 of . Our main result remains unchanged.

Table 2. Robustness checks I

Second, we include two measures on media freedom based on data from the V-Dem project: the index of free expression and the index of government efforts on censoring the Internet (Coppedge et al., Citation2021). By construction, higher values of both variables indicate more government respect for media freedom and less effort devoted to Internet censorship. The results of Models 2 and 3 in are consistent with those in : a higher level of power sharing is associated with more media freedom and less Internet censorship.

Third, we adopt the measure of media freedom constructed by Whitten-Woodring and Van Belle (Citation2017). In their dataset, a country’s media environment is categorized as one of three types: not free, imperfectly free, and free. About 86.75% of country-year observations in our sample are categorized as “not free,” while less than 1.85% of countries have free media. Thus, we combined dictatorships with free and partially/imperfectly free media environments into the same category and estimate a binary logit model with not-free as the baseline. We estimate a fixed-effect logit model with year dummies and report the result in Model 4. The coefficient of power sharing is not statistically significant but its sign is consistent with our expectation.

We estimate two additional models to check the robustness of our key independent variable, Power Sharing. First, we use a recent measure of power consolidation constructed by Gandhi and Sumner (Citation2020), which offers a measure of power consolidation in dictatorships by investigating dictators’ freedom from military and party constraints as well as their control over political offices. As Gandhi and Sumner (Citation2020, p. 1547) suggest that this measure can be used to “determine whether power is, in fact, shared or consolidated,” we use it as an alternative measure of power sharing in Model 5.Footnote8 Second, we estimate a model with a variable on executive constraint as an alternative measure of power sharing. We use data from the Polity IV project on how the executive branch in a country is institutionally constrained. The results of Models 5 and 6 support our hypothesis.Footnote9

In addition to constraints on the executive branch, we consider the role of other institutional settings in authoritarian regimes. Some dictatorships may have a higher level of political liberty than others, and that also enhances power sharing and media freedom. Similarly, authoritarian regimes holding multi-party elections may have higher levels of power sharing and media freedom. To address these issues, based on the efforts of the V-Dem team, we include variables that measure authoritarian regimes’ liberal dimension and their holding of multi-party elections. The results, as shown in Models 1 and 2 in , indicate that both variables, along with that of Power Sharing, are positively related to media freedom.

Table 3. Robustness checks II

Previous studies demonstrate that authoritarian regime type affects policy choices in dictatorships (Wright, Citation2010). Based on this insight, we investigate whether the relationship between power sharing and media freedom holds if we control for authoritarian regime types proposed by Geddes et al. (Citation2018). In Model 3 in , we include three regime dummies for military, monarchical, and single-party regimes (with personalist regimes as the omitted category). The results suggest that these three types of regimes have higher levels of media freedom than their personalist counterparts, but the difference is statistically insignificant between single-party and personalist dictatorships.Footnote10

Our theory suggests that power sharing requires transparency among elites to maintain regime stability, and the media play a role in offering more information about the dictator and elites. Yet, a country would be required to increase its transparency if it wants to receive more foreign aid or foreign direct investment (FDI). In addition, states with weaker capacity may be less able to control the media. We explore these possibilities by including the variables of foreign aid, FDI, and state capacity in Models 4 to 6 in , respectively.Footnote11 We find that only foreign aid matters to media freedom while FDI or state capacity does not. Nevertheless, Power Sharing remains statistically significant in those three models.Footnote12

Conclusion

This article provides an empirical analysis of the relationship between power sharing and media freedom under dictatorships. Whereas the bulk of the existing literature views authoritarian regimes as a unitary actor, we take advantage of the unexplored variation in power sharing between dictators and their allies to demonstrate its effect on media freedom. This finding enriches our understanding of the authoritarian politics of media freedom in several ways.

First, previous studies focus on how authoritarian leaders strategically use the media to collect information on local officials’ misconduct and citizens’ dissatisfaction with regime. We broaden this perspective by showing that they use the media to sustain the status quo of power sharing within their ruling coalition. Authoritarian elites use the media to offer public information with which they can monitor each other’s activities under the power sharing structure. Especially, while it is very intuitive to find a more personalist dictatorship to be more likely to crack down on the media, it is less so for the other side of our finding that media freedom actually goes up as a dictatorship engages in more power-sharing.

Second, this paper advances the literature on the media’s role in determining the regime survival for dictatorships. Our finding suggests that media freedom can actually be conducive to their consolidation. Authoritarian elites are less likely to misperceive and miscalculate each other’s behavior if they know well enough, through the media, about how the power is actually shared. In other words, the relaxation of media controls doesn’t always arise from liberation or democratization of an authoritarian regime. As a matter of fact, the level of media freedom can increase even without a democratic transition.

Moreover, this study echoes a recent call made by Geddes et al. (Citation2014) to switch the focus in the literature of comparative authoritarianism from democratic to autocratic transitions, which account for about half of all regime changes. Since we have shown media freedom to be critical to authoritarian stability, exogenous changes in the media environment in a dictatorship can thus disrupt the power-sharing relationship among its elites and eventually lead to a regime change. From an empirical point of view, future research should test if changes in the media environment can also be a good predictor of autocratic transitions.

Finally, given the long historical period (1960 to 2010) included in our statistical analyses, the findings in this paper are naturally more germane to the traditional media and their behaviors. That said, our theoretical argument is also readily applicable to the social media. As recent studies on the Chinese censorship show (King et al., Citation2013; Qin et al., Citation2017; Roberts, Citation2018), to be able to have access to local information and respond to possible issues timely, the Chinese government did not censor all criticisms on the Internet against it as long as criticisms only targeted local corruption and had no potential to facilitate collective actions against the state. In other words, while this literature explains this partial freedom of expression on the Chinese Internet mostly as an authoritarian state’s information acquisition strategy, our study actually suggests another equally plausible alternative: partial freedom for social media as an intra-elite monitoring mechanism. Since the information provided via social media is equally valuable for elites to monitor their power-sharing arrangements, this study opens up yet another avenue for future research to test if the intra-elite political dynamics also explain the policy toward Web 2.0 in dictatorships.

Open Scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data, Open Materials and Preregistered. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2021.1988009.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (85.4 KB)Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 2019 Midwest Political Science Association annual conference and the seminar series of the Institute of Political Science at Academia Sinica. The authors would like to thank conference and seminar participants, Nathan Batto, Eric Frantz, Haifeng Huang, Li Shao, Hsin-Hsin Pan, Peter Rosendorff, Joseph Wright, the editors, and anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments. Wen-Chin Wu would like to thank Ding-yi Lai for excellent research assistance. Greg Sheen would like to dedicate this article to the late Professor Becky Morton for her encouragement and support.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The data described in this article are openly available in the Open Science Framework at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LQMGBG.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2021.1988009.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Greg Chih-Hsin Sheen

Greg Chih-Hsin Sheen is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at National Cheng Kung University.

Hans H. Tung

Hans H. Tung is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and Faculty Associate in the Center for Research in Econometric Theory and Applications at National Taiwan University.

Wen-Chin Wu

Wen-Chin Wu is Associate Research Fellow in the Institute of Political Science at Academia Sinica.

These authors contribute to this article equally and their names are listed alphabetically.

Notes

1. With a refined measure of media freedom, Solis and Waggoner (Citation2020) fail to replicate the empirical finding of Egorov et al. (Citation2009). While we appreciate Solis and Waggoner (Citation2020)’s insight and adopt their measure in our empirical analysis, on the theoretical front, we would maintain that the argument of Egorov et al. (Citation2009) can still be a plausible explanation for why some dictators introduce partial media freedom that is useful for motivating our theory. The key argument of Egorov et al. (Citation2009, p. 645) that we adopt in our reasoning is their focus on the role of natural resources, especially oil and natural gas, in the agency problem between the dictator and the bureaucrats. Specifically, “free media allow a dictator to provide incentives to bureaucrats and therefore to improve the quality of government.” Given that the same mechanism, following the logic of the agency problem, is also suggested in other papers such as Lorentzen (Citation2014), we are not so concerned that Solis and Waggoner (Citation2020) new finding questions its validity.

2. We use the word “may” in this context to highlight that although increasing regime transparency to facilitate popular protests or other expressions of public grievances is a strategic option for the dictator, it does bear a potential cost, and so is unlikely to be the dictator’s dominant strategy. Recently, Little (Citation2016) and Stein (Citation2017) have shown theoretically and empirically that the advancements of communication technology have ambiguous effects on mass mobilization under authoritarian regimes. Thus, a dictator needs to assess the costs and benefits involved before adopting this strategy. That said, it is however well-established in the literature that dictators would take advantage of the presence of popular threats to unify elites. Slater (Citation2010), for example, illustrates the point through a case study on Mahathir’s Malaysia where he strategically played the threat of communal instability to his advantage by acting as the “protector” of broad elite interests against it.

3. We thank one anonymous reviewer for suggesting Turkey as a good example to demonstrate how dictators reward their supporters with control over media outlets. Accordingly to Geddes et al. (Citation2018), Turkey was categorized as a democracy in 1983, and therefore we did not include it in our empirical analysis. Nevertheless, we followed this reviewer’s suggestion and checked the Reporters without Borders’ Media Ownership Monitor that provides valuable qualitative insights. A closer examination of the Turkish case suggests that it is quite consistent with our theory. First, media concentration in Turkey increased dramatically under President Erdoğan who invited his cronies to purchase Turkish media outlets. While his friends owned these media companies on paper, it did not mean they enjoyed full control over them. During the same period, the Turkish media were put on a tighter leash with more regulations, so the majority of the media outlets practiced self-censorship and avoided reporting anything negative about the government (Tunç, Citation2015). Second, according to a recent V-Dem study on Turkish political development, President Erdoğan has made the regime more autocratic and personalistic. In other words, his rewarding his allies with media ownership might be a case of escalation of personal control over the regime rather than power sharing.

4. Following an anonymous reviewer’s suggestion, we extend the data beyond 2010 by replacing the power-sharing variable with cruder but available measures such as legislative constraints and multiparty election. Our results, as reported in Table A.7 in the online supplementary materials, still hold.

5. Geddes et al. (Citation2018) also regard the inverse of personalism as power sharing. They dedicate two chapters of their book to show that early leadership conflict would lead to either power sharing between the dictator and his allies or the concentration of power in his hands.

6. Model 1 in Table A.3 of the online supplementary materials reports those standardized coefficients.

7. Power sharing is a dynamic process during which new leaders may need to share power with others or gather power in their own hands over time (Geddes et al., Citation2018). Thus, we estimate an error correction model (ECM) to estimate short-term and long-term effects of power sharing on media freedom. We find that power sharing has only short-term effects on improving media freedom. we report and discuss the results of ECM in Table A.4 in the online materials.

8. The Gandhi-Sumner index focuses on how power is consolidated in dictators’ hands by considering the potential threat of the military against the regime and the history of purges as well as executive changes. Thus, this index considers the dimension of regime resilience and consolidation in dictatorships. Meanwhile, Geddes et al. (Citation2018) analyze how power is distributed between the dictator and the other two key institutions in a dictatorship: the party and the security apparatus. Geddes et al. (Citation2018) also measure whether a dictator’s power is “personalized” or constrained by institutions. Accordingly, both indices capture different dimensions of authoritarianism and result in a low correlation coefficient of 0.09.

9. Our results remain unchanged when we estimate with the V-Dem’s data on legislative and judicial constraints on executive power (see Model 2 in Table A.3 of the online supplementary materials).

10. We also estimate separate models for each type of dictatorship. The results in Table A.5 of the online supplementary materials show that the positive relationship between power sharing and media freedom is strongest in single-party dictatorships, followed by military and personalist regimes. Yet, it is statistically insignificant in monarchical regimes.

11. The data on foreign aid and FDI are taken from the World Development Indicators. We log-transform both variable to address skewness. The data on state capacity, operationalized as “the extractive capacity of nations,” are taken from Fisunoglu et al. (Citation2020).

12. Readers may be concerned about the issue of endogeneity between power sharing and media freedom. With the average level of power sharing at the regional level as an instrument, we employ two-stage least squares (2SLS) instrumental regression analysis to address this issue. The results suggest that a higher level of power sharing leads to more media freedom. Due to length limit, we report the results in Table A.8 in the online supplementary materials.

References

- Bai, D. (2015, September 24). Chen Liangyu challenged the central government (Chinese). China Times. Retrieved June 10, 2021, from https://www.chinatimes.com/newspapers/20150924000501-260109?chdtv

- Boix, C., & Svolik, M. W. (2013). The foundations of limited authoritarian government: Institutions, commitment, and power-sharing in dictatorships. Journal of Politics, 75(2), 300–316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381613000029

- Boleslavsky, R., Shadmehr, M., & Sonin, K. (2021). Media freedom in the shadow of a coup. Journal of the European Economic Association, 19(3), 1782–1815. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvaa040

- Brady, A.-M. (2017). Plus ça change?: Media control under Xi Jinping. Problems of Post-Communism, 64(3–4), 128–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2016.1197779

- Brownlee, J. (2007). Authoritarianism in an age of democratization. Cambridge University Press.

- Bueno de Mesquita, B., Smith, A., Siverson, R. M., & Morrow, J. D. (2003). The logic of political survival. MIT Press.

- Bünte, M. (2018). Perilous presidentialism or precarious power-sharing? Hybrid regime dynamics in Myanmar. Contemporary Politics, 24(3), 346–360. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1413500

- Casper, B. A. (2017). IMF programs and the risk of a coup d’état. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(5), 964–996. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002715600759

- Casper, B. A., & Tyson, S. A. (2014). Popular protest and elite coordination in a coup d’état. Journal of Politics, 76(2), 548–564. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381613001485

- Chen, T., & Hong, J. (2021). Rivals within: Political factions, loyalty, and elite competition under authoritarianism. Political Science Research and Methods,9(3), 599-614. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.61

- Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Cornell, A., Fish, M. S., Gastaldi, L., Gjerløw, H., Glynn, A., Hicken, A., Lührmann, A., Maerz, S. F., Marquardt, K. M., McMann, K. M., Mechkova, V., Paxton, P., & Ziblatt, D. (2021). V-dem codebook v11. Varieties of Democracy (V-dem) Project. https://www.v-dem.net/en/data/reference-material-v11/

- Egorov, G., Guriev, S., & Sonin, K. (2009). Why resource-poor dictators allow freer media: A theory and evidence from panel data. American Political Science Review, 103(4), 645–668. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409990219

- Fariss, C. J. (2014). Respect for human rights has improved over time: Modeling the changing standard of accountability. American Political Science Review, 108(2), 297–318. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000070

- Fisunoglu, A., Kang, K., Arbetman-Rabinowitz, M., & Kugler, J. (2020). Relative political capacity dataset (Version 2.4) [Data set]. Harvard Dataverse. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NRR7MB

- Frantz, E., Kendall-Taylor, A., Wright, J., & Xu, X. (2020). Personalization of power and repression in dictatorships. Journal of Politics, 82(1), 372–377. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/706049

- Gandhi, J. (2008). Dictatorial institutions and their impact on economic growth. European Journal of Sociology, 49(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975608000015

- Gandhi, J., & Sumner, J. L. (2020). Measuring the consolidation of power in nondemocracies. Journal of Politics, 82(4), 1545–1558. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/708683

- Geddes, B., Wright, J., & Frantz, E. (2014). Autocratic breakdown and regime transitions: A new data set. Perspectives on Politics, 12(2), 313–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592714000851

- Geddes, B., Wright, J., & Frantz, E. (2018). How dictatorships work. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316336182

- Gehlbach, S., & Keefer, P. (2011). Investment without democracy: Ruling-party institutionalization and credible commitment in autocracies. Journal of Comparative Economics, 39(2), 123–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2011.04.002

- Grunwald, H. A. (1993). The post-cold war press: A new world needs a new journalism. Foreign Affairs, 72(3), 12–16. JSTOR. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/20045619

- Guriev, S., & Treisman, D. (2019). Informational autocrats. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 100–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.4.100

- Hadenius, A., & Teorell, J. (2007). Pathways from authoritarianism. Journal of Democracy, 18(1), 143–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2007.0009

- Hale, H. E. (2017). Russian patronal politics beyond Putin. Daedalus, 146(2), 30–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/DAED_a_00432

- Hollyer, J. R., Rosendorff, B. P., & Vreeland, J. R. (2018). Information, democracy, and autocracy: Economic transparency and political (in)stability. Cambridge University Press.

- King, G., Pan, J., & Roberts, M. E. (2013). How censorship in China allows government criticism but silences collective expression. American Political Science Review, 107(2), 326–343. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000014

- Lauk, E. (1999). Practice of soviet censorship in the press: The case of Estonia. Nordicom Review, 20(2), 19–31. http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?dswid=5396&pid=diva2%3A1534634

- Lee, F. L. F., & Chan, J. (2009). Organizational production of self-censorship in the Hong Kong media. International Journal of Press/Politics, 14(1), 112–133. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161208326598

- Li, C. (2007). Was the Shanghai gang shanghaied?—The fall of Chen Liangyu and the survival of Jiang Zemin’s faction. China Leadership Monitor, 20, 11–19. https://www.hoover.org/research/was-shanghai-gang-shanghaied-fall-chen-liangyu-and-survival-jiang-zemins-faction

- Little, A. T. (2016). Communication technology and protest. The Journal of Politics, 78(1), 152–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/683187

- Lorentzen, P. (2014). China’s strategic censorship. American Journal of Political Science, 58(2), 402–414. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12065

- Lu, F., & Ma, X. (2019). Is any publicity good publicity? Media coverage, party institutions, and authoritarian power-sharing. Political Communication, 36(1), 64–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2018.1490836

- Magaloni, B. (2008). Credible power-sharing and the longevity of authoritarian rule. Comparative Political Studies, 41(4–5), 715–741. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414007313124

- Malesky, E., & Schuler, P. (2010). Nodding or needling: Analyzing delegate responsiveness in an authoritarian parliament. American Political Science Review, 104(3), 482–502. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055410000250

- Malesky, E., Schuler, P., & Tran, A. (2011). The adverse effects of sunshine: A field experiment on legislative transparency in an authoritarian assembly. American Political Science Review, 106(4). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1642659

- Marshall, M.G. (2017). Major Episodes of Political Violence (MEVP) and Conflict Regions, 1946–2016. Center for Systemic Peacehttps://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html

- Miller, M. K. (2015). Electoral authoritarianism and human development. Comparative Political Studies, 48(12), 1526–1562. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015582051

- Pei, M. (2006, September 26). The tide of corruption threatening China’s prosperity. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/f8c5f0a8-4d82-11db-8704-0000779e2340

- Qin, B., Strömberg, D., & Wu, Y. (2017). Why does China allow freer social media? Protests versus surveillance and propaganda. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(1), 117–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.1.117

- Repnikova, M. (2017). Media politics in China: Improvising power under authoritarianism. University Printing House.

- Roberts, M. E. (2018). Censored: Distraction and diversion inside China’s great firewall (Illustrated edition). Princeton University Press.

- Ross, M., & Mahdavi, P. (2015). Oil and Gas data, 1932–2014. Harvard Dataverse. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZTPW0Y

- Shirk, S.L. (2018). China in Xi’s “New Era”: the return to personalistic rule. Journal of Democracy 29(2), 22–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0022

- Slater, D. (2010). Ordering power: Contentious politics and authoritarian leviathans in Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press.

- Solis, J. A., & Waggoner, P. D. (2020). Measuring media freedom: An item response theory analysis of existing indicators. British Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 1685-1704.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000101

- Stein, E. A. (2016). Censoring the press: A barometer of government tolerance for anti-regime dissent under authoritarian rule. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 8(2), 101–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802X1600800204

- Stein, E. A. (2017). Are ICTs democratizing dictatorships? New media and mass mobilization*. Social Science Quarterly, 98(3), 914–941. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12439

- Stier, S. (2015). Democracy, autocracy and the news: The impact of regime type on media freedom. Democratization, 22(7), 1273–1295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.964643

- Stockmann, D. (2013). Media commercialization and authoritarian rule in China. Cambridge University Press.

- Svolik, M. W. (2009). Power sharing and leadership dynamics in authoritarian regimes. American Journal of Political Science, 53(2), 477–494. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00382.x

- Tunç, A. (2015). Media integrity report: Media ownership and financing in Turkey. South East European Media Observatory. https://mediaobservatory.net/radar/media-integrity-report-media-ownership-and-financing-turkey

- Whitten-Woodring, J., & Van Belle, D. A. (2017). The correlates of media freedom: An introduction of the global media freedom dataset. Political Science Research and Methods, 5(1), 179–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2015.68

- Wintrobe, R. (1998). The political economy of dictatorship. Cambridge University Press.

- Wright, J. (2010). Aid effectiveness and the politics of personalism. Comparative Political Studies, 43(6), 735–762. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414009358674

- Wright, J. (2021). The latent characteristics that structure autocratic rule. Political Science Research and Methods, 9(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.50