ABSTRACT

We explain why citizens believed and shared false political information during the 2019 UK general election campaign. In two surveys of samples mirroring the adult population conducted before the vote (total N = 4018), we showed respondents 24 different news statements and asked if they had seen them before, whether they believed them, and how likely they would be to share them on social media. The statements included actual disinformation that was circulating and had been debunked, placebos that did not feature in the campaign but were carefully constructed to resemble actual false statements spreading at the time, and true statements that were being reported during the campaign. We find that the more that respondents received their campaign news via professional news organizations, the more they were able to distinguish true from false information. Conversely, the more that respondents used social media for campaign news, the less they were able to distinguish true from false information. These differences also shaped the intention to share true versus false news, and false news, once perceived as accurate, was more likely to be shared than true news overall. This “campaign disinformation divide” between getting news from professional journalistic organizations and news from social media has important implications for contemporary election campaigns in democratic public spheres.

Election campaigns demand that the public play at least two key roles. First, citizens must discern between true and false information. This has become all the more important because misinformation and disinformation now circulate abundantly during campaigns. Second, citizens who use social media – 72% of British adults at the time of the 2019 election (OFCOM, Citation2020) – can act either to amplify or attenuate the spread of accurate and inaccurate political information.

In this study, we aim to clarify the factors that explain these important online behaviors. As we discuss below, research on the relationship between citizens’ use of different sources of news and resilience against disinformation has generally been lacking. We assess whether differences in media use for campaign news predict whether people discern between, and intend to share, true and false political information. In what we term the “campaign disinformation divide” the more that people got their campaign news from professional news organizations, the better able they were to discern truth from falsehood. Conversely, the more that people used social media for campaign news, the less able they were to discern truth from falsehood. This pattern also held when we examined people’s intentions to share news. We also show that those who (incorrectly or not) perceive a headline as accurate are more likely to say they will share that headline. This suggests that the association between media use and the sharing of true and false information is likely to be mediated by discernment. Finally, we reveal that false information, when perceived to be accurate, is more likely to be shared than true information.

Hypotheses and Research Question

The spread of false and exaggerated information threatens democratic norms (Bennett & Livingston, Citation2018; Freelon & Wells, Citation2020). Widespread circulation of dubious, manipulated, or fabricated material calls into question expectations of rationality, authenticity, and equality in public debate and may legitimize cynicism and distrust at both elite and popular levels.

In this study, we define “disinformation” as intentionally spreading information known to be false and “misinformation” as unintentionally spreading false information believed to be true (Jack, Citation2017). We focus on disinformation because, as we explain below, we assessed citizens’ responses to falsehoods originally circulated by political and journalistic elites, who likely had access to accurate information and tools for verification and can therefore be reasonably assumed to have spread those falsehoods intentionally. Although deception often occurs through complex combinations of truth and falsehoods (Chadwick & Stanyer, Citation2022), and political debates are ripe with what Vraga and Bode (Citation2020) define as “controversial” claims, on which evidence is scant and expert opinion is evolving, the false headlines we focused on can be considered relatively “settled” because reputable fact checkers mustered sufficient evidence to rate them as inaccurate.

We explain two important outcomes of the spread of disinformation in a campaign: that citizens believe inaccurate information and that they then intend to share it on social media. We explain these outcomes as a function of people’s patterns of media use for campaign news. We ground our argument in a theory of how different media differentially equip people to identify false and misleading claims, provide different kinds of material to share in online networks, encourage citizens to adopt different kinds of civic norms, and attract audiences that may be differently equipped and inclined to identify and share accurate and inaccurate content.

Misinformation and Disinformation in the UK Media System

Concerns about misinformation and disinformation in the UK began to grow after the 2016 Brexit referendum, in which online propaganda to spread falsehoods was abundant (Bastos & Mercea, Citation2019). Disinformation and misinformation circulates widely among British social media users: a survey found that 57.7% of UK social media users saw inaccurate news on social media in the past month (Chadwick & Vaccari, Citation2019). The 2019 general election campaign also featured substantial disinformation (Wring & Ward, Citation2020). Most British citizens get their political news from a blend of television (57%), news websites (56%), and social media (41%). Radio (28%) and print newspapers (24%) are still important, but lag behind (Fletcher et al., Citation2020). The online news market is dominated by traditional media, particularly the public service broadcasters BBC and ITV and the tabloid newspapers The Daily Mail, The Sun, and The Daily Mirror (Chadwick et al., Citation2018). Broadcasters are subject to a strict regulatory regime that ensures their public affairs coverage – including online – is balanced. They are also forbidden from officially backing a political party. UK newspapers, by contrast, openly endorse political parties (Wring & Ward, Citation2020). The tabloid press often publish sensationalized, exaggerated, and occasionally fabricated news, but broadcast news is a more popular election news source overall.

The Campaign Disinformation Divide

Previous research has addressed disinformation’s diffusion and, to a limited extent, its impact on attitudes and behavior, but scholarship has mostly overlooked whether different media use patterns explain citizens’ capacity to distinguish between true and false information. Most work has focused on individual digital platforms (e.g., Garrett, Citation2019; Vosoughi et al., Citation2018) or on digital media in isolation. For example, Allcott and Gentzkow (Citation2017) found that people who primarily use social media for news were less likely to accurately identify both true and false news headlines related to the 2016 U.S. presidential elections. However, they did not compare the role of social media with that of professional news organizations and did not consider news sharing. Garrett (Citation2019) found that social media use was linked with a slightly increased tendency among strong partisans to endorse false statements in the 2012 U.S. presidential elections but not in 2016. Koc-Michalska et al. (Citation2020) found that social media users who post at least occasionally about politics were substantially more likely to believe they had encountered false news. None of these studies allows for comparison with use of other media for getting campaign news.

To our knowledge, only two published studies included use of both professional and social media for news as predictors of misinformation sharing, but neither of them specifically compared the role of these news sources. Based on panel data from Chile, Valenzuela et al. (Citation2019) did not find any significant associations between professional and social media use for news and misinformation sharing. However, their analysis was centered on the use of social media, but not professional media, for news. Rossini et al. (Citation2021) analyzed cross-sectional survey data from Brazil and did not find significant correlations between the use of professional news media and the accidental or intentional sharing of false information on Facebook and WhatsApp. They also found negative correlations between the use of social media for news and the intentional sharing of falsehoods on Facebook and WhatsApp, but a positive correlation between social media news use and the unintentional sharing of misinformation on Facebook. These contradictory findings highlight the need for further research on this important topic.

Patterns of News Consumption and the Discernment and Sharing of Disinformation

There are good reasons why the balance of sources people use for campaign news may explain their ability to identify false information, which in turn may also explain downstream behavior such as sharing such information on social media. Some recent studies (Castro et al., Citation2021; Shehata & Strömbäck, Citation2021) suggest that, even though social media are a relevant source of news for substantial numbers of citizens, their use does not always result in the acquisition of political knowledge. Castro et al. (Citation2021, p. 24) argued that “traditional news media – in their offline and online formats – convey a more valuable array of political information and are more successful in providing a general overview of what is going on in politics and society than other news sources.” Based on survey data in seventeen European countries, they found that citizens who rely heavily on social media for news are substantially less politically knowledgeable than those who mainly get their news via traditional media and online news websites. Shehata and Strömbäck (Citation2021, p. 128) argued that news on social media juxtaposes content from many different sources, is organized according to social endorsements rather than journalistic gatekeeping, and entails forms of personalization that may prevent some users from seeing relevant information. Based on panel surveys in Sweden, the authors show that “people are less likely to learn general news about politics and current affairs from using social media than from using traditional news media” (Shehata & Strömbäck, Citation2021, p. 129). While these studies focus on the acquisition of political knowledge, as opposed to the ability to identify false information, their underlying logic is consistent with our theory that professional news organizations may be more likely than social media to disseminate valid and relevant information that may better enable their audiences to discern between truth and falsehood.

In the UK, professional news organizations provide citizens with information that is more likely to have been editorially selected, verified, and contextualized. Broadcast media content, which remains the most popular source of election news even if accessed online, is tightly regulated based on public service provisions, while the press is bound by a weaker though still relevant set of rules, mainly established via industry-wide self-regulation codes administered by independent regulators. Professional journalistic norms also play a role, especially during election campaigns. The UK’s tabloid press is well known for its sensationalist reporting style, which also extends to its political coverage. Yet, tabloid use during UK elections should also be considered in the context of citizens’ heavy use of public service professional media sources.

A further key development is the growth and institutionalization of fact checking journalism. The UK’s main independent fact checker, Full Fact, is a small charity organization with only a handful of staff that partnered with Facebook as a Third Party Fact Checker during the 2019 general election and is routinely quoted by journalists in their coverage of campaigns. The most prominent fact checking takes place inside professional, public service organizations the BBC and Channel 4. Given fact checking’s prominence in election coverage by professional media organizations and its affinity with the public service broadcasting ethic, we should expect exposure to news from professional media to matter for people’s capacities to discern falsehoods.

Social media, by contrast, convey a much wider variety of information, some provided without context or verification and some shared to deceive others. One in ten UK social media users regularly amplify false and misleading information (Chadwick et al., Citation2022) and correcting misinformation is less common on social media than sharing problematic information (Chadwick & Vaccari, Citation2019, pp. 18–19). Social media are not bound by laws beyond those on crime and illegal speech and they regulate users’ behaviors through their own terms of service and community standards, enforced with platform-specific moderation tools that have been criticized for their partial or inconsistent application (Gillespie, Citation2020). This may mean that on social media individuals are more likely to be exposed to false or misleading news with less counterpoint or fact-checking. Disinformation-based extremism also matters for the quality of experience on social media. This can be a deliberate political strategy on social media to recruit supporters by sowing divisions (Cox et al., Citation2021). It can be a funding model for “conspiracy entrepreneurs” (Sunstein & Vermuele, Citation2009) who seed links to websites into Facebook groups to profit from online advertising or use social media to redirect users to their crowdfunding tools (EU DisinfoLab, Citation2020). These practices increase the likelihood that social media users will be exposed to disinformation. Of course, some of this exposure may be selective: some people will be motivated to seek out information that affirms their conspiracy-based attitudes. Still, in today’s media systems, affirming a belief often involves sharing evidence and information about it via social media. Even those who select-in to disinformation due to their own predilections are likely to find it easier to affirm their beliefs if they find resources to share (Chadwick et al., Citation2018). And, even if that exposure is incidental, or does not lead to the individual being newly deceived, encountering disinformation on social media may still have a disorienting effect that challenges people’s abilities to discern truth from falsehood (Deibert, Citation2019).

This point highlights that social media use might have longer-term consequences for norms of online civic culture. Some studies have shown that frequent use of social media and not prioritizing seeking news from professional sources are both associated with lower political knowledge (Castro et al., Citation2021; Gil de Zúñiga et al., Citation2020). A strand of research from the early phase of social media expansion examined the relationship between “dutiful” and “actualizing” styles of citizenship (Bennett et al., Citation2011). Dutiful citizenship was mostly associated with key institutions of modernity such as political organizations, mass education, and the press. These organized citizens’ knowledge and shaped opportunities for expression based on expectations of a duty to acquire formal civic skills. In contrast, actualizing citizenship derived from immersion in peer-defined online networks where informal expression and flexible, personalized forms of engagement were more relevant than formal organizations and hierarchical logics (Bennett et al., Citation2011). Building on these insights, Feezell et al. (Citation2016, p. 104) found that “media routines may cultivate a sense of civic duty in a way that helps to offset the costs of voting and even inspire dutiful citizenship.” Citizens who communicated online based on dutiful styles were more likely to vote, but actualizing styles did not have the same effect. The citizenship norms enacted on different media can thus have important implications for civic behavior.

This kind of perspective, reframed to account for disinformation, can help develop new, experientially focused accounts of media use. People’s citizenship orientation, capacity, and sense of responsibility may be differentially shaped over time by the communicative norms they encounter in everyday media consumption. Norms are learned in part by observing the behavior of others (Cialdini et al., Citation1991). They not only concern what is deemed acceptable, for example, regarding standards of verification and the use of evidence, but also derive from expectations about the obligations of informed citizenship that people encounter. These understandings are likely to be evolving under the conditions of extreme uncertainty and informational abundance in contemporary media systems. A useful starting point involves considering how different forms of news consumption may encourage different behavioral expectations among citizens about the extent to which they should devote vigilance toward the information environment of a campaign. This goes beyond simple exposure to true and false information and includes how norms are encoded in news coverage of elections. For some citizens, the narrower editorial selection and presentation typical of professional news organizations might convey signals about what matters for the national political conversation and the individual’s role within it. And, given that fact checking has become such a prominent part of professional media coverage of UK election campaigns, people exposed to such coverage are more likely to have encountered not just fact-checked information but also the norm, encoded in news content, that fact checking is itself a necessary, worthwhile, and responsible activity during a campaign.

Finally, news acquired via professional news organizations and social media may explain citizens’ response to disinformation because these sources attract different audiences who are differently equipped and motivated to discern between truth and falsehood. For instance, Castro et al. (Citation2021) find that citizens who get their news mainly via traditional and public service media are more likely to be male and older; they also have higher levels of education, interest in politics, and trust in media. By contrast, citizens who mainly get their news via social media are more likely to be female and younger, and report lower levels of education, interest in politics, and trust in media. Citizens who mainly rely on online news websites (including by professional news organizations) have a very similar profile to those who depend on social media, but they are highly interested in politics. Audience characteristics may have relevant implications for citizens’ ability to discern truth from falsehood. When there is a wide choice of media, citizens with different levels of civic skills and motivations might gravitate toward campaign news sources that provide them with the kind of information they prefer and enshrine the norms they support. In reality, however, as cultivation theory approaches have shown, the effects of content and audience characteristics are likely to compound each other: different news sources may provide audiences with content of different quality, which may lead some citizens to increase their exposure to the channels that more closely meet their demands and expectations while reducing their engagement with the channels that fail to do so (e.g., Slater, Citation2007).

Based on these considerations, we hypothesize that the more people get campaign news from professional media, the more they will be able to accurately identify true and false news about the campaign (H1). Conversely, the more people get campaign news from social media, the less likely they will be to accurately identify true and false news (H2).

H1: Greater exposure to campaign news via professional news organizations is associated with higher perceived accuracy of true news headlines than false news headlines.

H2: Greater exposure to campaign news via social media is associated with higher perceived accuracy of false news headlines than true news headlines.

That citizens believe false information about an election is troubling enough, but social media also enable people to distribute campaign news among their networks. The consequences of this sharing behavior may be even more problematic, for it may quickly increase the number of people who potentially believe false information and act upon it. Hence, our second outcome of interest is the intention to share true or false news headlines on social media.

Multiple factors explain why social media users might share true and false information online (Duffy et al., Citation2020; Kümpel et al., Citation2015; Pennycook & Rand, Citation2019). Scholars have assessed the characteristics of the users and organizations sharing the news, of the content being shared, and of the networks across which information travels (Kümpel et al., Citation2015). Individuals’ personality, affective orientation, motivations, cognitive styles, and skills have been shown to affect the sharing and correction of false news (Bode & Vraga, Citation2021).

However, we know surprisingly little about the role of different sources of news. Yet, the sources of news people use to keep up with an election may influence the kinds of news they share online. People are more likely to share what they are exposed to. As discussed above, frequent social media users are more likely to see unverified information than those who mainly consume content produced by professional news organizations. Media are resources people mobilize as they seek to exercise agency (Edgerly et al., Citation2016). Some individuals consciously share news because they want to achieve goals – whether self-serving, altruistic, or social (Kümpel et al., Citation2015) – or take advantage of network media logic (Klinger & Svensson, Citation2015) to influence campaign information flows. Content that can help achieve these goals is widely available via both professional news organizations and social media. But social media provide a wider variety of information, often packaged in easily “shareable” formats such as memes, rich media, vivid images, animations, and catchy quotes (e.g., Nissenbaum & Shifman, Citation2017).

Based on this reasoning, we hypothesize that the more individuals get their information from professional news organizations, the more inclined they will be to share true rather than false news (H3). Conversely, the more people acquire information from social media, the more likely it is they will intend to share false rather than true news online (H4).

H3: Greater exposure to campaign news from professional news organizations is associated with a stronger intention to share true news headlines than false news headlines.

H4: Greater exposure to campaign news from social media is associated with a stronger intention to share false news headlines than true news headlines.

The Role of Perceived Accuracy in News Sharing

A basic question is whether people are more likely to share news if they believe it to be true (Duffy et al., Citation2020). Some social media users may willingly share news that they know to be false to achieve partisan gain, disrupt the flow of information, or entertain themselves and others (Chadwick et al., Citation2018). However, most people who share false news believe it to be true at the time they share it (Chadwick & Vaccari, Citation2019). False news shared online is also often accompanied by statements of disbelief (Metzger et al., Citation2021) and, when individuals are primed to pay greater attention to the veracity of information, they become less likely to share false news (Pennycook & Rand, Citation2019). Overall, we expect that most people are more inclined to share news on social media that they believe to be true and not false. Hence, we hypothesize (H5):

H5: Perceived accuracy of news headlines is positively associated with the intention to share them.

By testing H5, we can also shed light on the relationships between sources of campaign news, perceived accuracy of news, and the intention to share it, in a quasi-mediation mechanism. If sources of campaign news predict the intention to share true and false news (H3 and H4, the c-path), is it because, as indicated by H5 (the b-path), campaign news sources predict the perceived accuracy of true and false news (H1 and H2, the a-path)? Or, do campaign news sources independently predict the intention to share true and false news above and beyond the extent to which perceived accuracy predicts an individual’s intention to share true and false news?

Finally, we contribute to the debate on whether false information stands a better chance of spreading online than true information, as shown by Starbird et al. (Citation2014) and Vosoughi et al. (Citation2018). Previous analyses are based on Twitter data and their findings may be skewed due to the demographics and attitudes of that important, but relatively less popular, social media platform (Blank, Citation2017). Given the limits of existing research, we formulate a question (RQ1):

RQ1: Is any positive relationship between perceived accuracy of news headlines and the intention to share them stronger for true or for false news headlines?

Method

Sample and Design

We rely on two online surveys (combined nrespondents = 4,018) administered by Opinium Research shortly before the 2019 election on samples that resemble the UK adult population in terms of gender, age, education, and region (see Supplementary Material SM1).

In the first part of the survey, respondents answered questions (devised by Opinium as part of its electoral survey) about demographic characteristics, attitudes to UK politics and the campaign, and intended voting behavior. Subsequently, in each survey, respondents saw twelve campaign news headlines, which we presented in randomized order and added to the survey specifically for this study. After seeing each headline, respondents were asked whether they had come across the news story in the last few weeks, whether they thought it was true or false, and, in the second survey only, how likely they would be to share it online. All participants saw all twelve headlines in each survey.

Of the twelve headlines in each survey, eight were false statements derived from a database we compiled of all published fact checks from the UK’s four leading fact checkers (BBC Reality Check, Channel 4 Fact Check, Full Fact, and First Draft) during the campaign (November 1 – December 4, 2019, n = 169). These eight headlines summarized disinformation, often originating from political elites, that was circulating on social media or in news coverage and which had been authoritatively debunked. Each survey also included two placebo false headlines. These did not feature in the campaign but were constructed by us to read as if they were actual false headlines spreading during the campaign. To preserve balance, in each survey one placebo conveyed disinformation damaging to the Conservatives, the incumbent party, the other to Labour, the main opposition party. Finally, each survey included two true headlines from statements that had been reported during the campaign – again, one harmful to each of the two main parties. Including placebos and true headlines allowed us to control for the extent to which respondents would believe and share any kind of headline (Levine et al., Citation1999) and for any effect that respondents’ trust in the survey company or our research project may have had on their assessments of the false headlines.Footnote1

The survey ended with a detailed debriefing note that explained why the headlines had been shown, illustrated which of them were false, and provided links to authoritative fact checks. SM2 reports all the headlines and descriptive statistics on participants’ response to them.

When combining both surveys, we analyze a total of 24 headlines: 16 false, 4 placebos, and 4 true. We compare how participants responded to false headlines (combining the actually circulating disinformation and the placebos) with how they responded to true headlines. Overall, we have 12*4,018 = 48,216 observations across twenty-four headlines: 40,180 for twenty false headlines and 8,036 for four true headlines. As we measured the intention to share news only in the second survey, the models predicting this outcome are based on 12*2,000 = 24,000 observations across 12 headlines: 20,000 for ten false headlines and 4,000 for two true headlines.

Measures of the Dependent Variables

Perceived Headline Accuracy

In both surveys, after showing respondents each headline we asked: “What do you think about the accuracy of this news story?.” The response modes were: “It is definitely true” (scored 5), “It is probably true” (4), “I am not sure if it is true or false” (3), “It is probably false” (2), and “It is definitely false” (scored 1; M = 3.20, SD = 1.04).

Intention to share the headline. In the second survey only, we also asked respondents: “If you had the opportunity to share this news story on social media such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, or on private messaging apps, such as WhatsApp and Snapchat, would you do so?” Response modes were: “Yes, definitely” (scored 5), “Yes, probably” (4), “Maybe” (3), “Probably not” (2), and “Definitely not” (scored 1; M = 2.16, SD = 1.24).

Measures of the Independent Variables

Media Used for Campaign News

Before we showed respondents the headlines, we asked: “How often do you turn to each of the following for getting news about the general election campaign?” and listed 13 different media, in random order per participant.Footnote2 Response modes were: “Several times a day” (scored 5), “About once a day” (4), “About once a week” (3), “Less often” (2), and “Never” (scored 1).

We ran a principal component analysis (PCA) that included the ten channels that our respondents reported using most: the five most frequently used channels we conceptualized as professional news organizations (broadsheet newspapers, tabloid newspapers, television, radio, and online news websites) and the five most frequently used social media channels (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and private messaging apps). The full results of the PCA and the distribution of the resulting factors scores in the sample are reported in SM3.Footnote3 A solution featuring two components with Eigenvalues >1 emerged. After oblique rotation, the five social media channels all loaded on the first factor (use of social media for election news, M = 0.00, SD = 1.00). The five professional channels all loaded on the second factor (use of professional media for election news, M = 0.00, SD = 1.00). Thus, we computed the factor scores for each respondent and used them as independent variables in our models.

Headline False Vs. True

We coded the headlines as 0 = false and 1 = true. We used this variable in interaction terms to assess whether using different sources for news was associated with different levels of perceived accuracy of, and intention to share, true versus false headlines.

Control Variables

To ensure that our relationships of interest are not confounded by other variables that could potentially affect our key outcomes, our models include various relevant controls: whether participants recognized the headline, whether they incorrectly recognized placebo headlines, whether the headline covered an issue important to the participants, whether the headline attacked the participants’ preferred party or Brexit position, the likelihood of voting in the 2019 general election, gender, educational attainment, the number of cars as a proxy for income, and whether participants took part in only one or both surveys.Footnote4

Models

Since we exposed each participant to both true and false headlines, we wanted to control for a respondent’s general propensity to perceive any headlines as accurate and share them, regardless of whether they were true, false, or placebos. To account for these differences, we ran mixed linear regression models that allowed the intercept to vary for each participant, thus capturing a participant’s average response to all headlines. In addition, we added our control variables as single fixed effects terms to account for their general influence on our two dependent variables across all headlines. To test H1-H4, we added interaction terms that capture whether our relationships of interest vary between true and false headlines. Here, a significant interaction coefficient implies that the relationship between use of a type of media for news and the perceived accuracy of a headline or the intention to share it differs between true and false headlines. If the interaction term is positive, with increased use of the respective media the outcome increases more strongly for true than for false headlines. If the interaction term is negative, the outcome increases more strongly for false than for true headlines as use of the relevant media increases. These interaction terms thus estimate participants’ ability to discern between truth and falsehood in their responses to the headlines.

Results

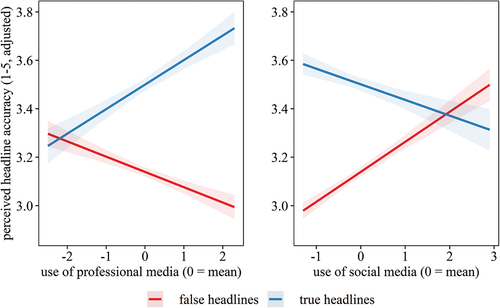

displays the model explaining how participants assessed the accuracy of the headlines we showed them. As predicted by H1, the interaction between true vs. false headlines and use of professional media for election news is positive and significant (b = .164, p < .001). The more a person uses professional media for campaign news, the more likely she is to perceive a true headline as more accurate than a false one. As shown in the left panel in , greater use of professional media is associated with greater discernment between truth and falsehood.

Table 1. Mixed linear regression model explaining perceived headline accuracy using the PCA factors for media use (surveys 1 and 2 combined).

Figure 1. Perceived accuracy of true vs. false headlines by use of professional and social media for getting news about the election (surveys 1 and 2 combined).

The interaction term between use of social media for campaign news and true vs. false headlines in tests H2. Again, we find support for this hypothesis, as the coefficient is negative and significant (b = −.188, p < .001). That is, the more that participants use social media for getting news about the election, the more likely they are to perceive false headlines as more accurate than true headlines. As shown in the right panel in , respondents with low levels of social media news use perceive true headlines to be more accurate than false headlines, but those who use social media for news the most perceive false headlines to be equally as accurate as true headlines. In other words, the ability to distinguish between true and false headlines dissolves away among people who rely heavily on social media for their campaign news.

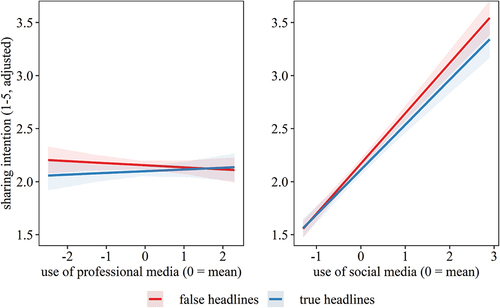

Next, we turn to the models explaining participants’ intention to share the news headlines. Model A in tests H3 and H4. As predicted by H3, the interaction term between use of professional media for campaign news and true vs. false headlines is positive and significant (b = .036, p = .011). Increased reliance on professional sources for news is associated with a slightly stronger intention to share true than false headlines. In contrast, the interaction term between use of social media for campaign news and true vs. false headlines (H4) is negative and significant (b = −.050, p < .001). The more participants use social media for news, the more inclined they are to share false rather than true headlines. However, these results should be interpreted with caution because the coefficients are relatively small. Accordingly, reveals that the differential relationship between use of both types of media for campaign news and sharing true vs. false headlines is less pronounced than the one involving perceived accuracy of the headlines. For our sharing outcome, the significantly different slopes for the use of professional and social media do not differ strongly enough to lead to clearly observable different estimates across different levels of campaign news use.

Table 2. Mixed linear regression models explaining intention to share headlines using the PCA factors for media use (survey 2 only).

Figure 2. Intention to share true vs. false headlines by use of professional and social media for getting news about the election (only survey 2).

Although the strength of these relationships varies depending on the outcome we consider, the results show that use of professional media for campaign news is positively associated with higher perceived accuracy of, and stronger intention to share, true than false headlines, while the opposite holds for use of social media for news. These congruent findings raise the question of whether the relationship between patterns of media use and the intention to share true vs. false headlines is in fact mediated via perceived headline accuracy. Model B in sheds light on this possibility by integrating perceived headline accuracy into the model explaining the intention to share headlines. As predicted by H5, perceived headline accuracy is positively and significantly associated with the intention to share headlines (b = .195, p < .001). Moreover, the interaction terms between the types of media used for campaign news and true vs. false headlines are no longer significant in this model. In other words, perceived headline accuracy, rather than media use per se, predicts the intention to share a headline. However, has already shown that the perceived accuracy of true vs. false headlines is explained by the types of media used for campaign news in the first place. These results are consistent with the possibility that the relationship between patterns of media use and intention to share true vs. false news is mediated via perceived headline accuracy. Even though the characteristics of our data prevent us from testing this mediation model directly, the logic of our analysis follows the analytical approach proposed by Baron and Kenny (Citation1986), as we compared models that predict the intention to share news and that include and exclude perceived accuracy of news.

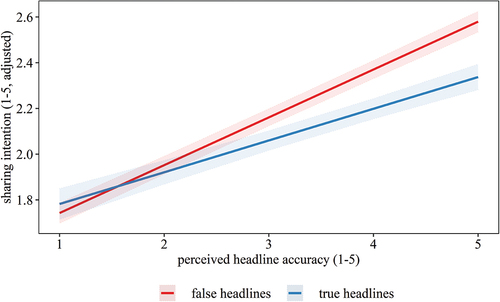

Finally, we assess whether the relationship between perceived accuracy and the intention to share news differs between true vs. false headlines (RQ1). In Model C in , the interaction term between perceived accuracy and true vs. false headlines is negative and significant (b = −.070, p < .001). Thus, as perceived headline accuracy increases, the intention to share false headlines increases more strongly than the intention to share true headlines (). In short, once false news is perceived as accurate, it is more likely to be shared than true news.

Figure 3. Intention to share true vs. false headlines by perceived headline accuracy (only survey 2).

Robustness Checks and Additional Analyses

We conducted a wide range of robustness checks, available in the Supplementary Materials (SM5-9). These employ CFA-based factor scores rather than PCA-based factor scores as independent variables (SM5-6) and integrate a range of additional controls: general use of social media (SM7) and interaction terms between whether the headline was false vs. true and a) education, b) likelihood of voting in the 2019 election, and c) whether the headline attacks respondents’ preferred party or position (SM8-9). The results all confirm our main findings.

Moreover, to better understand the role of different media in the campaign disinformation divide, we ran additional models where, instead of our PCA scores, we entered as key predictors the ten individual variables measuring use of different campaign news sources (SM10). These models largely confirm our results. Higher use of broadsheets, television, and news websites is significantly associated with a greater likelihood to perceive true headlines as more accurate than false headlines (consistent with H1). Conversely, higher use of Instagram, YouTube, and private messaging apps is associated with higher perceived accuracy of false headlines than true headlines (consistent with H2). In the additional models predicting the intention to share news headlines, most associations are not significant. Still, we found a significant correlation between higher use of television and a higher intention to share true than false news (consistent with H3), and a significant association between higher use of Instagram and a stronger intention to share false than true news (consistent with H4).

However, these additional models also revealed two notable exceptions. In the model predicting perceived accuracy of news headlines, higher use of tabloids for news is associated with higher perceived accuracy of false than true headlines and use of Twitter for news is associated with higher perceived accuracy of true than false headlines. Use of Twitter for news is also significantly associated with a higher intention to share true than false news. These results qualify our main argument. UK tabloid newspapers produce sensationalized and partisan coverage (Chadwick et al., Citation2018) and it is thus not surprising that their use for news is, on its own and not as part of a broader diet of professional news, associated with lower discernment between true and false headlines. By the same token, considered in isolation, Twitter is, among the social media we measured, by far the most news-focused and, thus, on its own and not as part of a broader diet of social media, is most likely to attract users who are more interested in public affairs, more skilled in differentiating between true and false information, and more cautious with the news they share (Blank, Citation2017).Footnote5

Limitations

This study has some limitations that we must acknowledge. First, our analysis is based on opt-in online samples that do not generalize to the population in the same ways as probability-based samples (Baker et al., Citation2010). Secondly, the statistical associations we showed cannot demonstrate causality. In particular, the audiences for news via professional news organizations and social media differ on some key characteristics that may contribute to explaining citizens’ ability to identify, and likelihood of sharing, true and false information. Although our models employed a robust set of control variables including age, education, a proxy for income, and measures tapping into respondents’ political involvement and their interest in, and position on, the issues discussed in the headlines, we cannot fully rule out this alternative explanation. Longitudinal and experimental studies should investigate the nature and underlying mechanisms of these relationships over time. Thirdly, although we took great care to use true, false, and placebo headlines capturing the key policy issues of the campaign, which we derived from a large database we compiled of all published fact checks from the UK’s four leading fact checkers, a different set of headlines may have yielded different results. Also, not all problematic campaign communication can easily be classified as true or false, but often entails exaggeration, innuendo, and selective presentation and omission (Chadwick & Stanyer, Citation2022). We did not fully measure the impact of these different types of attempted deception in this study. Fourthly, the mix of true and false news headlines we showed participants may not be reflective of typical campaign news but presenting the headlines in random order and including placebos should have minimized this potential source of bias. Fifthly, we classified the headlines based on truthfulness, topic, and party or position attacked, but we did not address other potentially relevant variables, e.g., whether the headlines originated from journalists or politicians, whether they focused on personality or policy, and the emotional responses they elicited. Future research should assess the role of these and other message-level features, while also testing how these relate to the broader factors assessed in our study. Sixthly, we included relevant control variables, but we could not incorporate standard measures of income, ideology, political interest and knowledge, trust in news sources, or digital literacy. Finally, our measure of news sharing on social media captures an attitude – the intention to share – rather than a behavior – the act of sharing.

Conclusions

This study clarifies some of the key challenges, and potential remedies, that characterize democratic election campaigns in dissonant public spheres (Bennett & Pfetsch, Citation2018). We have revealed a stark campaign disinformation divide, as citizens who access campaign news via different sources are differently able to distinguish false from true information, which in turn has implications for their intention to share news online. Building on, but also departing from, existing research (Allcott & Gentzkow, Citation2017; Rossini et al., Citation2021; Valenzuela et al., Citation2019; Zimmermann & Kohring, Citation2020), we found that citizens’ exposure to campaign coverage by professional news organizations was associated with their greater ability to differentiate true from false information (left panel of ). By contrast, exposure to campaign news on social media was associated with lower levels of discernment, as their heavier users were more likely to believe false information (right panel of ) and, in turn, more inclined to share it (right panel of ). Because people are more likely to share information they believe to be true (Pennycook & Rand, Citation2019), the relationship between use of different sources of news and the perceived accuracy of disinformation also helps explain the behavioral outcome of online sharing. Finally, the more respondents perceived a headline as accurate, the more likely they were to share it, but this was more the case for false than true headlines (). Thus, false information was more “shareable” than true information (Vosoughi et al., Citation2018).

These findings highlight the centrality of journalists in enabling citizens to protect themselves and others from disinformation (Freelon & Wells, Citation2020). Even though most of the false headlines we showed participants had been widely publicized by news organizations as well as circulating online, our findings suggest that news produced by professional journalistic organizations may offer, in relative terms, stronger protection against both believing and sharing false information than news accessed via social media. As we outlined in our theoretical framework, the comparatively strong public service values that govern UK broadcast journalism and the tradition of professionalism of the printed press, mixed with a self-regulatory regime, may mean that professional news media cover campaigns in a way that potentially enhances discernment and resilience against disinformation (Castro et al., Citation2021). By contrast, the kind of information that circulates on social media, even if much of it may originate with, or be adapted from, content produced by news organizations, may leave users more vulnerable to developing misperceptions which, as we documented, could in turn result in the further propagation of falsehoods in a vicious circle of exposure, misperception, and sharing.

As we also highlighted in our theoretical discussion, this study provides a first step on a path to reframing how the long-term inculcation of citizenship norms may depend on people’s different media consumption patterns (Bennett et al., Citation2011). The divide we have revealed may be one manifestation of a deeper transformation that goes beyond the fact that mere exposure to disinformation is higher among those who spend more time on social media. Disinformation-based extremism and deliberate attempts to deceive are now widespread online (Chadwick & Vaccari, Citation2019; Vosoughi et al., Citation2018) and even if such attempts do not succeed, disorientation is itself an outcome that could make it more difficult to discern truth from falsity (Deibert, Citation2019).

Perhaps more fundamentally, citizens who spend more time engaging with professional media coverage of a campaign may be more likely to be exposed to the style of citizenship that promotes norms of vigilance as communicative goods in themselves. As we argued, the best example of this is the growth of the fact checking genre in professional media organizations’ election coverage. Not only does fact checking provide citizens with information useful for understanding and appraising attempts to deceive, it may also signal the norm that fact checking is itself a necessary and valuable activity and one required to build resilience to disinformation.

Our analysis highlights the value of research designs that focus on the campaign media system in its entirety rather than on digital media only, or on a single social media platform (Klinger & Svensson, Citation2015). We have shown that professional news media will be central in renovating and repairing disrupted public spheres, but social media companies have a crucial role to play as well. More incisive policies may be needed to reduce the spread of disinformation online. Yet, policies that bolster professional news organizations will be equally important.

Open Scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badge for Open Data. The data are openly accessible at https://osf.io/xfked/?view_only=f3df4b38d106460e84eaf86352b1a3e3.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (2.8 MB)Acknowledgments

We thank Opinium Research for inviting us to add our experiment to their multi-wave general election tracker surveys. We also thank participants in the panel at the American Political Science Association 2021 Annual Meeting, where we first presented this study.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The data described in this article are openly available in the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/xfked/?view_only=f3df4b38d106460e84eaf86352b1a3e3.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2022.2128948

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cristian Vaccari

Cristian Vaccari (PhD, IULM University in Milan) is a Professor of Political Communication and Director of the Centre for Research in Communication and Culture at Loughborough University.

Andrew Chadwick

Andrew Chadwick (PhD, London School of Economics) is a Professor of Political Communication in the Department of Communication and Media at Loughborough University, where he is also director of the Online Civic Culture Centre.

Johannes Kaiser

Johannes Kaiser (PhD, University of Zurich) is a postdoctoral researcher at the Online Civic Culture Centre at Loughborough University.

Notes

1. By using placebo headlines in this way we extend Allcott and Gentzkow’s (Citation2017) and Zimmermann and Kohring’s (Citation2020) method of using them to assess faulty recall of false news.

2. We also included an item measuring face-to-face conversations with other people, but we did not consider it for this analysis because it was not central to our theoretical framework.

3. Results did not change when we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) instead of PCA, both in terms of the variables included in each dimension (see SM3) and in terms of the results of our multivariate models (see SM5-6). Alternative specifications of the CFA with different combinations of news sources did not yield a better fit (SM3).

4. See SM4 for extensive information on how we constructed these variables and on their distribution.

5. In SM7 we discuss the strengths of using PCA in greater detail.

References

- Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

- Baker, R., Blumberg, S. J., Brick, J. M., Couper, M. P., Courtright, M., Dennis, J. M., Lavrakas, P. J., Garland, P., Groves, R. M., Kennedy, C., Krosnick, J., Lavrakas, P. J., Lee, S., Link, M., Piekarski, L., Rao, K., Thomas, R. K., Zahs, D., & Dillman, D. (2010). Research synthesis: AAPOR report on online panels. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74(4), 711–781. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfq048

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Bastos, M. T., & Mercea, D. (2019). The Brexit Botnet and user-generated hyperpartisan news. Social Science Computer Review, 37(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439317734157

- Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317

- Bennett, W. L., & Pfetsch, B. (2018). Rethinking political communication in a time of disrupted public spheres. Journal of Communication, 68(2), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqx017

- Bennett, W. L., Wells, C., & Freelon, D. (2011). Communicating civic engagement: contrasting models of citizenship in the youth web sphere. Journal of Communication, 61(5), 835–856. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01588.x

- Blank, G. (2017). The digital divide among twitter users and its implications for social research. Social Science Computer Review, 35(6), 679–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439316671698

- Bode, L., & Vraga, E. K. (2021). Correction experiences on social media during COVID-19. Social Media & Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211008829 .

- Castro, L., Strömbäck, J., Esser, F., & Theocharis, Y. (2021). Navigating high-choice european political information environments: A comparative analysis of news user profiles and political knowledge. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 27(3), 763–783. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612211012572

- Chadwick, A., & Stanyer, J. (2022). Deception as a bridging concept in the study of disinformation, misinformation, and misperceptions: Toward a holistic framework. Communication Theory, 32(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtab019

- Chadwick, A., & Vaccari, C. (2019). News sharing on UK social media: Misinformation, disinformation, and correction. Online Civic Culture Centre. https://www.lboro.ac.uk/research/online-civic-culture-centre/news-events/articles/o3c-1-survey-report-news-sharing-misinformation/

- Chadwick, A., Vaccari, C., & Kaiser, J. (2022). The amplification of exaggerated and false news on social media: The roles of platform use, motivations, affect, and ideology. American Behavioral Scientist, online first, https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642221118264

- Chadwick, A., Vaccari, C., & O’Loughlin, B. (2018). Do tabloids poison the well of social media? Explaining democratically dysfunctional news sharing. New Media & Society, 20(11), 4255–4274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818769689

- Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A., & Reno, R. R. (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 24, 201–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60330-5.

- Cox, K., Ogden, T., Jordan, V., & Paille, P. (2021). Covid-19, disinformation and hateful extremism. RAND Europe. https://bit.ly/3orGFsQ

- Deibert, R. (2019). The road to digital unfreedom: Three painful truths about social media. Journal of Democracy, 30(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0002

- DisinfoLab, E. U. (2020). How Covid-19 conspiracists and extremists use crowdfunding platforms to fund their activities. https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/how-covid-19-conspiracists-and-extremists-use-crowdfunding-platforms-to-fund-their-activities/

- Duffy, A., Tandoc, E., & Ling, R. (2020). Too good to be true, too good not to share: The social utility of fake news. Information, Communication & Society, 23(13), 1965–1979. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1623904

- Edgerly, S., Thorson, K., Bighash, L., & Hannah, M. (2016). Posting about politics: Media as resources for political expression on facebook. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13(2), 108–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2016.1160267

- Feezell, J. T., Conroy, M., & Guerrero, M. (2016). Internet use and political participation: Engaging citizenship norms through online activities. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13(2), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2016.1166994

- Fletcher, R., Newman, N., & Schulz, A. (2020). A mile wide, an inch deep: Online news and media use in the 2019 UK general election. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3582441

- Freelon, D., & Wells, C. (2020). Disinformation as political communication. Political Communication, 37(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1723755

- Garrett, R. K. (2019). Social media’s contribution to political misperceptions in U.S. presidential elections. PLOS ONE, 14(3), e0213500. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213500

- Gil de Zúñiga, H., Strauß, N., & Huber, B. (2020). The proliferation of the “news finds me” perception across societies. International Journal of Communication 14, 1605–1633 .https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/11974/3011.

- Gillespie, T. (2020). Content moderation, AI, and the question of scale. Big Data & Society, 7(2), 205395172094323. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720943234

- Jack, C. (2017). Lexicon of Lies: Terms for problematic information. Data & Society. https://datasociety.net/pubs/oh/DataAndSociety_LexiconofLies.pdf

- Klinger, U., & Svensson, J. (2015). The emergence of network media logic in political communication: A theoretical approach. New Media & Society, 17(8), 1241–1257. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814522952

- Koc-Michalska, K., Bimber, B., Gomez, D., Jenkins, M., & Boulianne, S. (2020). Public beliefs about falsehoods in news. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(3), 447–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220912693.

- Kümpel, A. S., Karnowski, V., & Keyling, T. (2015). News sharing in social media: A review of current research on news sharing users, content, and networks. Social Media + Society, 1(2), 2056305115610141. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115610141

- Levine, T. R., Park, H. S., & McCornack, S. A. (1999). Accuracy in detecting truths and lies: Documenting the “veracity effect.” Communication Monographs, 66(2), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759909376468

- Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., Mena, P., Jiang, S., & Wilson, C. (2021). From dark to light: The many shades of sharing misinformation online. Media and Communication, 9(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i1.3409

- Nissenbaum, A., & Shifman, L. (2017). Internet memes as contested cultural capital: The case of 4chan’s /b/ board. New Media & Society, 19(4), 483–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815609313

- OFCOM. (2020). Adults’ Media Use & Attitudes report 2020. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/196375/adults-media-use-and-attitudes-2020-report.pdf

- Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2019). Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning. Cognition, 188, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.06.011

- Rossini, P., Stromer-Galley, J., Baptista, E. A., & Veiga de Oliveira, V. (2021). Dysfunctional information sharing on WhatsApp and Facebook: The role of political talk, cross-cutting exposure and social corrections. New Media & Society, 23(8), 2430–2451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820928059

- Shehata, A., & Strömbäck, J. (2021). Learning political news from social media: Network media logic and current affairs news learning in a high-choice media environment. Communication Research, 48(1), 125–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217749354

- Slater, M. D. (2007). Reinforcing spirals: The mutual influence of media selectivity and media effects and their impact on individual behavior and social identity. Communication Theory, 17(3), 281–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00296.x

- Starbird, K., Maddock, J., Orand, M., Achterman, P., & Mason, R. M. (2014). Rumors, false flags, and digital vigilantes: Misinformation on twitter after the 2013 Boston marathon bombing. iConference 2014 Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.9776/14308

- Sunstein, C. R., & Vermuele, A. (2009). Symposium on conspiracy theories— conspiracy theories: causes and cures. Journal of Political Philosophy, 17(2), 202–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2008.00325.x

- Valenzuela, S., Halpern, D., Katz, J. E., & Miranda, J. P. (2019). The paradox of participation versus misinformation: Social media, political engagement, and the spread of misinformation. Digital Journalism, 7(6), 802–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1623701

- Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

- Vraga, E. K., & Bode, L. (2020). Defining misinformation and understanding its bounded nature: Using expertise and evidence for describing misinformation. Political Communication, 37(1), 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1716500

- Wring, D., & Ward, S. (2020). From bad to worse? The media and the 2019 election campaign. Parliamentary Affairs, 73(Suppl._1), 272–287. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsaa033

- Zimmermann, F., & Kohring, M. (2020). Mistrust, disinforming news, and vote choice: A panel survey on the origins and consequences of believing disinformation in the 2017 German parliamentary election. Political Communication, 37(2), 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1686095