ABSTRACT

This article examines the nationalist rhetoric of Biden and Trump in the 2020 presidential election, focusing on how the candidates represented, and contested, the meaning of American national identity. To do so, we construct a novel analytical framework to undertake a contextual content analysis of Biden and Trump’s campaign tweets (n = 4,321). We demonstrate that the meaning of national identity was a key source of contestation in the election, and that the parameters of this contestation closely tracked a longstanding cleavage in American political culture between civic and ethnic nationalist traditions. Biden largely drew upon the civic nationalist tradition to defend a conception of American national identity that is grounded in liberal myths and symbols. By contrast, Trump largely drew upon the ethnic nationalist tradition to defend a conception of American national identity that is grounded in white American myths and symbols. Critically, both candidates used these opposing nationalist traditions to frame each other as a grave threat to the nation’s “true” identity and, ultimately, as un-American. This “nationalist polarization” of presidential politics is a troubling development for the future of American democracy.

Introduction

The 2020 American presidential election was billed by both the incumbent Donald Trump and his challenger Joe Biden as a great struggle over the meaning of America’s national identity. In a much-cited speech, delivered at the National Archives at the height of the campaign, Trump declared, “our mission is to defend the legacy of America’s founding, the virtue of America’s heroes, and the nobility of the American character … the only path to national unity is through our shared identity as Americans” (Trump, Citation2020). Meanwhile, Biden depicted his campaign as a “battle for the soul of America,” asserting that it was about “who we are as a nation, what we believe, and maybe most importantly, who we want to be – it’s about our essence; it’s about what makes us Americans” (Biden, Citation2020). The centrality of national identity in this messaging begs for further investigation of the precise role that it played in the 2020 campaign.

In this article, we take on this investigation. Our inquiry is guided by a set of linked questions. We ask, how did Trump and Biden represent, and contest, the meaning of America’s national identity? More specifically, what kinds of nationalist myths and symbols did the candidates draw upon, and where do these myths and symbols come from? Furthermore, how did contestation over national identity relate to other campaign issues and, critically, how did it shape their depictions of each other – as opponents of their respective visions of America’s identity? Finally, what are the implications of depicting each other in this way for understanding political polarization in America? To address these questions, we construct a new analytical framework to carry out a contextual content analysis of the nationalist rhetoric of Trump and Biden’s Twitter communication during the 2020 presidential election.

We primarily seek to contribute to an area of research in American political communication examining the nationalist rhetoric of contemporary presidential campaigns. Much of the literature here is concerned with the rhetoric of right-wing, Republican presidential candidates – with an intensive focus on Donald Trump (e.g., Austermuehl, Citation2020; Feinberg et al., Citation2022; Ott & Dickinson, Citation2019; Restad, Citation2020; Rowland, Citation2021; Schertzer & Woods, Citation2021, Citation2022). This research demonstrates how Trump and other right-wing candidates present an exclusionary vision of American national identity, which privileges white Americans at the expense of racial, ethnic, and religious minorities and migrants. While this rhetoric is sometimes explicit, more often it is encoded in rhetorical devices, such as racist “dog whistles” or “fig leaves” (Haney-López, Citation2014; Mercieca, Citation2020; Rowland, Citation2021; Saul, Citation2017). Nevertheless, in our view, this research tends to have an overly restrictive definition of American nationalism that grounds it only in white American identity. This work can thus downplay other, opposing traditions of American identity – particularly the longstanding tradition that is grounded in the more inclusive, classical liberal ideals of the so-called “founding documents.” To this point, several recent studies of presidential campaign communication have run against the general thrust of the field by suggesting that nationalism is used, and contested, by candidates on both the right and the left, with the former supporting an exclusionary white American tradition, and the latter supporting an inclusive liberal tradition (see Barreto & Napolio, Citation2020; Bonikowski et al., Citation2021, Citation2022; Lieven, Citation2016; Stuckey, Citation2005).

This nuanced approach to American nationalism as a contested ideology between exclusionary and inclusive traditions is supported by extensive research on the development of American political culture. This work demonstrates how America’s social and political institutions have been shaped by a long-running conflict between these traditions (Bonikowski & DiMaggio, Citation2016; Citrin et al., Citation1990; Gerstle, Citation2017; Kaufmann, Citation2004; King & Smith, Citation2005; Lepore, Citation2019; Li & Brewer, Citation2004; Lieven, Citation2012; Schertzer & Woods, Citation2022; Smith, Citation1997). Related research further suggests that this conflict has recently become more entrenched, with the two main political parties increasingly divided accordingly, such that Republicans tend to support the exclusionary tradition, and the Democrats tend to support the inclusive tradition (Bonikowski et al., Citation2021). Indeed, we are seeing an increasingly central role of identity politics in political campaigns in America, with Democrat and Republican leaders tapping into divides over race, religion and cultural issues, layering them over partisan cleavages (Mason, Citation2018; Sides et al., Citation2018). This has contributed to a growing polarization of American politics, which is threatening a backsliding of democratic norms (Graham & Svolik, Citation2020; Kingzette et al., Citation2021; Lieberman et al., Citation2019). More generally, these insights on American political culture broadly correspond with findings from the comparative study of nationalism. Here several scholars use the concepts of “ethnic” and “civic” nationalism (rather than “exclusionary” and “inclusive,” respectively) to understand nationalist cleavages between defenders of the cultures of dominant ethno-national groups, and defenders of liberal ideals (see Breton, Citation1988; Brubaker, Citation2009; Jones & Smith, Citation2001; Reeskens & Hooghe, Citation2010). Work in this field has shown that while it is deeply problematic to categorize entire nations as “civic” or “ethnic,” these concepts can help us understand the division and contestation that takes place within nations over the meaning of national identity (Hutchinson, Citation2005; Schertzer & Woods, Citation2022).

In this paper, we use insights from research on American political culture and the study of nationalism to develop a new analytical framework to carry out a contextual content analysis of the nationalist rhetoric of Biden and Trump’s presidential campaign communication. More precisely, this framework builds directly on previous work that traces how nationalists use deeply rooted ethnic myths and symbols in their political communication (see Schertzer & Woods, Citation2021, Citation2022). Here, we have expanded our analytical lens to trace the use of nationalist rhetoric more generally – in both its ethnic and civic variants – by actors from both the political right and left. As we show in this article, this wider aperture allows us to better capture the role of nationalism as a source of contestation between political candidates than existing work to date. Critically, by tracing the different ways that candidates represent the “true” nature of the nation’s identity, we can better understand the role of nationalism as a key feature of presidential campaign communication, for both left-wing and right-wing candidates.

Using this framework, our analysis of Biden and Trump’s Twitter communication during the 2020 presidential election affirms that nationalist rhetoric was central to both candidates’ campaigns – indeed, it was more prevalent in Biden’s tweets (36%) than Trump’s tweets (27%). Furthermore, while both candidates referred to nationalist myths and symbols as themes in their own right, they also used them to frame their messaging on other topics during the campaign. The way in which the candidates did so was also a key source of contestation between them. Here, the candidates took up the longstanding struggle between the civic and ethnic traditions of American national identity, with Biden defending the former, and Trump defending the latter (although both candidates also occasionally used myths and symbols from the opposing tradition). The centrality of this struggle in Biden and Trump’s campaigns also affected how they depicted each other: both candidates depicted their counterpart as a grave threat to America’s “true” identity. As we discuss in the conclusion, this way of representing political opponents as external “Others” who are fundamentally antithetical to a nation’s identity illuminates that there is a nationalist dimension to America’s polarized politics. This “nationalist polarization” has the potential to further undermine democratic norms.

To make this case, we begin by outlining our analytical framework. We then apply this framework to analyze Trump and Biden’s Twitter communication, before discussing the significance of our findings.

Analytical Framework

This article is about how political candidates within democracies use nationalist rhetoric to defend opposing conceptions of national identity. To unpack this process, our analytical framework builds upon a perspective that sees national identity as a quasi-religious source of meaning in the modern world (see Hayes, Citation1960; Mosse, Citation1975; Smith, Citation2003). Relatedly, we define nationalism primarily as a meaning-making ideology that is concerned with cultivating, and defending, a distinct conception of national identity (on the role of “cultural nationalism” in this process, for example, see Hutchinson, Citation1986; Woods, Citation2016). In short, nationalism and national identity are closely linked; it is through nationalism that national identity is infused with meaning. One of the primary ways nationalism seeks to achieve this objective is by drawing upon institutionalized sets of myths and symbols about the nature of a group, as a nation. In particular, these “myth-symbol complexes” provide nationalism with cultural resources for representing the nation as a unique moral community that is identifiable by cultural boundaries denoting who belongs, and who does not (see Schertzer & Woods, Citation2022: Chapter 2; Smith, Citation1998, 181–83).

We define national myths as foundational beliefs that a national community holds about itself. By addressing existential questions (e.g. “who are we?,” “where did we come from?” etc.), myths provide national communities with meaning and legitimacy (see Schöpflin Citation1997). National myths are inextricably intertwined with symbols – it is through symbols that myths are externalized and communicated to a community’s membership (Armstrong, Citation1982, p. 11). However, in segmented communities, the mythic meanings of symbols are often multivocal, and can become vectors for conflict. For example, while the American Flag is broadly accepted to be a symbol of American national identity, its precise meaning is contested by Americans on the right and left of the political spectrum. This is not to say that the meanings of all symbols are wholly fluid – the meanings of some symbols are relatively durable, such as the association of the confederate flag with myths of white supremacy and resistance to the federal government.

National identities today tend to be so deeply embedded in the institutions of political communities throughout the world that the idea that they constitute a “nation” is a widely accepted, largely unnoticed, banal feature of life (Billig, Citation2005). This phenomenon is particularly associated with political communities in the West, where the idea of the “nation” was institutionalized under the cover of statehood over a relatively longue durée (Malesevic, Citation2019). However, if this process resulted in the nation becoming banal, it did not result in a single, monolithic conception of its identity. Instead, western states tend to be characterized by internal “culture wars,” in which rivals draw on opposing nationalist myths and symbols to defend the nation’s “true” identity (Hutchinson, Citation2005). This is especially apparent in debates over immigration, in which opposition to, and support for, immigration is framed by competing conceptions of national identity (see Fitzgerald, Citation1996; Perhson & Green, Citation2010; Wright, Citation2011).

The dichotomy between civic and ethnic nationalism, which we touched upon in the introduction, is a useful device for interpreting these internal cleavages. Civic nationalism emphasizes classical liberal principles (i.e., natural rights, political equality, rule of law, representative government) as the basis of solidarity and, as such, it promotes an inclusive vision of the nation’s boundaries in which anyone can belong irrespective of their ethnic, racial, religious or class background (provided that they ascribe to civic nationalism’s liberal principles). It is important to underscore here that civic nationalism is not a cosmopolitan ideology without boundaries – it is decidedly a nationalist ideology. As such, it is above all concerned with the defense of its principles within its national territorial boundaries. Relatedly, it is not uncommon for civic nationalism to construct cultural boundaries with perceived “Others” on the basis that they do not properly adhere to liberal principles. By contrast, ethnic nationalism emphasizes a common ethnic heritage as the basis of solidarity and promotes an exclusionary vision of the nation’s boundaries, which is based upon perceived shared characteristics of the ethnic majority. Unlike civic nationalism, in the view of ethnic nationalism, perceived “Others” will therefore never truly belong. We acknowledge that this dichotomy between civic and ethnic nationalism has been criticized on the basis that most nationalisms contain both civic and ethnic elements (Brubaker, Citation1999; Smith, Citation2010, 42–46; Yack, Citation1996). However, we agree with Genevieve Zubrzycki (Citation2002) that the dichotomy retains heuristic value if it is used as an ideal type rather than as a true reflection of reality (see also Schertzer & Woods, Citation2022: Chapter 2).

The exclusionary features of ethnic nationalism means that it often combines with racism, especially in the West, where ethnic nationalists tend to emphasize the whiteness of their nations in order to exclude people who are not perceived to be white (see Valluvan, Citation2019). This phenomenon is particularly true in America (see Eyerman, Citation2022). Researchers focusing on America thus tend to focus on whiteness when exploring exclusionary identity politics (e.g., Abramowitz, Citation2018; Jardina, Citation2019; Ott & Dickinson, Citation2019). This has led to a preference to focus on racial appeals and use concepts like “white nationalism” rather than “ethnic nationalism.” We use “ethnic nationalism” because ethnicity is a somewhat looser concept than “race,” which can include a diverse set of group signifiers, such as religion, language, and various cultural practices – in addition to including “race” (see Schertzer & Woods, Citation2022: Ch. 2). The concept of ethnic nationalism therefore enables us to specify a complex of related nationalist signifiers – of which, in the American case, whiteness is central, but which also includes and intersects with Christianity, the English language (spoken with an “American” accent), and being “native born,” among many others. We thus recognize that in America you can not necessarily “unbundle” these signifiers of national identity. For example, whiteness tends to be intertwined with Christianity (Butler, Citation2021; Perry & Whitehead, Citation2015). At the same time, focusing on ethnic nationalism allows us to trace these intersections from a broader, comparative viewpoint. In short, our analytical framework treats racism as an important component of a broader, ethnic nationalist American myth-symbol complex.

Given our focus on the communication of political elites, we should explain how we understand their relationship to myth-symbol complexes. Against the view that nationalist traditions are “invented” by elites via a top-down process (c.f. Hobsbawm & Ranger, Citation1983; Brubaker, Citation2004), we argue that they are constructed via an interactive process between political elites and wider populations. In this process, elites incorporate institutionalized myths and symbols from target populations into their political communication in order to infuse it with meaning and thereby garner support. In our view, the political communication of elites is therefore relatively constrained by the existing complex of myths and symbols within their target populations (see Motyl, Citation2001). By the same token, this complex of myths and symbols provides elites with cultural resources to draw upon in pursuit of their political aims. From a historical perspective, the recurring use of these myths and symbols by elites serves to periodically reinvigorate their significance, and helps to ensure that they persist through time (for more on this approach, see Schertzer & Woods, Citation2022: Chapter 2). While this approach is mainly derived from Anthony Smith’s insights (see Smith, Citation1998; 2009), it also broadly aligns with framing analysis (Snow & Benford, Citation1992; Benford & Snow, Citation2000) and cultural sociology (Alexander et al., Citation2006; Woods & Debs, Citation2013).

Finally, to identify and trace the various mytho-symbolic elements of national identity used in political communication, we have developed a schema of five, foundational nationalist referents that play a role in boundary-making:

People – how the characteristics of the nation’s membership is perceived

Religion – how the nation’s relationship to religion is perceived

Territory – how the nation’s territory is perceived

History – how the nation’s past, present, and future, is perceived

Place in the World – how the nation’s relationship with other nations is perceived

These five referents are based on a wide reading of literature on ethnicity and nationalism – particularly Armstrong (Citation1982) and Smith (Citation1986, 1991; 2009) – on the most common elements of nationalist myth-symbol complexes. We acknowledge this schema is not exhaustive. Our aim is to address the most common referents across time and space that nationalists use to define “their” nation’s identity. Furthermore, in practice, these referents are not discrete; as components of a broader myth-symbol complex, they tend to be enmeshed with one another. For example, in the American case, the categories of “people” (e.g., white) and “religion” (e.g., Christian) often overlap with one another. And, as we noted earlier, some symbols that underpin these referents can have an element of multi-vocality whereby they reinforce different conceptions of the nation, depending on how they are employed in myths about the nation’s identity. Nevertheless, we feel there is value in retaining these as discrete categories for the purpose of analyzing nationalist content. For example, there is a compelling argument – even in the American case – to retain a category for “religion” that is distinct from “people.” Doing so enables fine-grained comparison of processes related to how, why, and when the categories intertwine, and when they unravel – for example, in the history of relations between Anglo Protestants and Irish Catholics in America.

Our analytical framework pulls from these threads in the study of nationalism – on myth-symbol complexes, on the interactive relationship between elites and the “masses” in the construction of myth-symbol complexes, on the civic-ethnic dichotomy, and on the five referents of national identity – to examine Biden and Trump’s campaign communication.

Mapping America’s Conflicting Traditions of National Identity

Our analytical framework for examining the role of nationalist myths and symbols in presidential campaigns requires a method that is sensitive to historical and cultural context. In short, we first need to map a nation’s myth-symbol complex before analyzing how it is used by the candidates. This two-stage methodology draws on insights from contextual content analysis (see McTavish & Pirro, Citation1990). America is an interesting case because it is characterized by a long-running conflict between civic and ethnic traditions of national identity – each of which are comprised of a distinct complex of myths and symbols.

Beginning with the civic tradition, for much of America’s history, there was a near consensus among (white) scholarly observers that its national identity was fundamentally based upon classical liberal ideals (see Arieli, Citation1964; Hartz, Citation1955; Lipset, Citation1996; Schlesinger, Citation1998). For several leading 20th century students of nationalism, these characteristics made America a paradigmatic civic nation (see Greenfeld, Citation1992; Kohn, (Citation2017 [1944]). This understanding of American national identity has since been roundly criticized. However, it has proved to be remarkably durable beyond academia (Lieven, Citation2012). Indeed, America’s civic tradition is so widely believed that it is akin to a religion – it is, as Gunnar Myrdal (Citation2017 [1944]) put it, the “American Creed.” And much like a religion, it is accompanied by a dense cultural complex. At the core of this complex is a myth that America is a world-historical political community founded on classical liberal ideals, as symbolized, especially, by its “founding documents.” This, in turn, informs a related myth that anyone can belong to the American nation, irrespective of their backgrounds. Accordingly, this myth suggests that in a world mired in ascribed hierarchies and ethnic hatreds, America is “exceptional” and, as such, it has a special mission to be a beacon for its liberal ideals (see Lieven, Citation2012). In the decades following the Second World War, amidst the rise of the civil rights movement, this classical civic mythology became intertwined with a more progressive, anti-racist liberal myth (see Gerstle, Citation2017, pp. 268–310). Unlike previous incarnations, the progressive myth acknowledges America’s illiberal and racist past (and present). As such, it supports a program of working to banish existing illiberalisms, so that America can fulfill its destiny and take up its true (civic) identity. It is this progressive myth, for example, that former President Barack Obama called upon in his famed speech, “A More Perfect Union” (NPR, Citation2008).

By contrast, the ethnic tradition originated with English Protestant settlers, among whom a myth-symbol complex developed through relations with various perceived out-groups, including Indigenous Americans, African Americans, and other white settlers who were neither British nor Protestant. The core elements of the emergent cultural complex were whiteness, Anglo-Saxonness, and Protestantism (see Higham, Citation2002; Horsman, Citation1986; Kaufmann, Citation2004). Later, during the rapid growth of black enslavement in the 19th century, whiteness became preeminent (Painter, Citation2010). The ethnic tradition underwent further changes in the second half of the 20th century, amid the integration of European and Catholic Americans with Anglo-Protestants. As a result, the myth that America is a Protestant nation was largely replaced with a broader myth that it is Christian. Similarly, the myth of America’s Anglo-Saxonness was largely replaced by myths emphasizing its broader European heritage. Through these changes, whiteness endured as a key symbol denoting who truly belongs as a “real” American (see Ignatiev, Citation1995; Jacobson, Citation1999; Roediger, Citation1991). Another important change in the ethnic tradition in the second half of the 20th century relates to how it was expressed. Following the successes of the civil rights movement, the explicit defense of white American identity by mainstream politicians became untenable (see Schertzer & Woods, Citation2022: Chapter 4). Nevertheless, white identity remains a central element of American politics (Jardina, Citation2019) and it continues to be expressed implicitly through speech codes (i.e. racist dog whistles) (Haney-López, Citation2014).

Throughout America’s history, the conflict between America’s civic and ethnic traditions has alternated between phases when it is relatively calm, and phases when it is more intense – the latter of which was demonstrated most spectacularly by the Civil War (for an overview, see Schertzer & Woods, Citation2022: Chapter 4). Arguably, we are entering a new phase of heightened conflict where conflicts over the meaning of American national identity are animating politics (Mason, Citation2018; Sides et al., Citation2018). The emergence of this current phase occurred with Barack Obama’s election to the presidency in 2008. Obama’s win was perceived by many liberal observers as a triumph of America’s civic identity. However, it also triggered a cultural backlash among many conservative (and mainly white) Americans, who coalesced around the Tea Party movement, and subsequently greatly influenced the Republican Party (Norris & Inglehart, Citation2019; Skocpol & Williamson, Citation2016). The Tea Party was ostensibly inspired by fiscal conservatism, but its members often expressed ethnic nationalist ideas (Gerstle, Citation2017, pp. 375–426). Trump capitalized on this backlash by making ethnic nationalism central to his successful campaign for the presidency in 2016 (Schertzer & Woods, Citation2021). Trump’s win and use of ethnic nationalism galvanized the defenders of the civic tradition and set the stage for the 2020 election as a battle between competing traditions of American national identity.

To understand precisely how these conflicting traditions manifested themselves in the 2020 campaign, we began by mapping their core myths and symbols using our schema of the five foundational referents of national identity (see ). To do so, we drew upon research on America’s conflicted political culture (e.g., Bonikowski & DiMaggio, Citation2016; Citrin et al., Citation1990; Gerstle, Citation2017; Kaufmann, Citation2004; King & Smith, Citation2005; Lepore, Citation2019; Li & Brewer, Citation2004; Lieven, Citation2012; Schertzer & Woods, Citation2022; Smith, Citation1997). We recognize that this table is far from exhaustive. What we have done here is try to capture core myths and their related symbols. As we discussed in the preceding section, we also acknowledge that the mythic meanings of symbols are often multivocal and contested. We have tried to mitigate this possibility by selecting indicative symbols that are associated with relatively durable meanings. However, to properly interpret meaning, the context in which they occur is key – this is why, as we outline below, we use a contextual method for analyzing content. We should also note that the myths and symbols listed here are directed inward, in the sense that they indicate “our” national identity. However, myth-symbol complexes develop in relation to perceived out-groups. This means that the myths and symbols in this table are also simultaneously directed outward; by indicating who “we” are, they indicate who “we” are not (on this process, see Schertzer & Woods, Citation2022: Chapter 2).

Table 1. Civic and ethnic myths and symbols of American national identity.

The Role of National Identity in the 2020 Presidential Campaign

In this section, we discuss findings from our analysis of Biden’s and Trump’s Twitter communication. Leaders campaign through many mediums – such as speeches, paid adds, earned news media coverage, internet memes, and social media – often tailoring their messaging to target different audiences. In this article we are specifically looking at Twitter for several reasons: it played a critical role in the rise and success of Trump; both Trump and Biden used it as a central platform for their campaign communication; while the candidates likely adapted their messaging for the platform, it also serves as an aggregator and distributor of their broader campaign communication; and, as a primarily text-based medium, it facilitates the kind of content analysis we are carrying out here. Accordingly, we collected every tweet by Biden and Trump for the most intense campaigning period prior to the 2020 vote (June 20, 2020, to November 3, 2020).Footnote1 All told, this equates to 4,321 tweets.Footnote2

Our method to investigate these tweets draws from qualitative content analysis. We used as our framework to identify when and how the candidates used national myths and symbols in their tweets. We also further coded tweets to track other substantive themes, and to indicate whether they conveyed positive or negative sentiment (or neither).Footnote3 This method of combining content analysis with sentiment analysis helped us to unpack how Biden and Trump used competing depictions of America’s national identity in their Twitter communication. While the text-based nature of Twitter can facilitate content analysis, the medium can also present challenges, particularly for identifying how leaders use national myths and symbols on the platform. National myths and symbols are historically constituted and widely institutionalized, such that their meanings are so embedded in populations that they can be communicated implicitly. As discussed in the introduction, when American politicians use ethnic nationalist rhetoric today, they tend to do so through “dog-whistles” and other rhetorical devices (Haney-López, Citation2014; Mercieca, Citation2020; Rowland, Citation2021; Saul, Citation2017). Even when leaders tap into the civic tradition, they often do so using pithy statements that imply their intended meanings. These characteristics make it difficult to precisely categorize the nationalist content of messages as it often requires historical and cultural knowledge to identify the meaning. In addition, the short-form nature of prose on Twitter means that complex codes can be buried in short, subtle, and opaque phrases.

To manage these coding challenges, we adopted an interpretivist approach to content analysis sensitive to the context of political communication. Our coding process followed a deliberative and collaborative approach seeking intercoder consensus (see Naganathan et al., Citation2022; O’Connor & Joffe, Citation2020).Footnote4 Our analysis was conducted in phases. After an initial phase of data immersion and refining the coding framework, three authors undertook a collaborative process of coding, in which each tweet was read in sequence by at least two of them, and all disagreements were tracked and resolved through deliberation at regular meetings. In the next phase, the two remaining authors reviewed every coded tweet, noting disagreements and again resolving them through deliberation at regular meetings. In addition, these authors carried out keyword searches to check the consistency of coding across time and to ensure main themes were not missed. Coding was carried out using computer software (NVivo).Footnote5 Through this deductive and inductive approach, every tweet was read and coded by at least four of the five authors – with disagreements resolved through deliberation. This is a labor-intensive process, that we recognize does not fully address subjectivity. However, the deliberative and collaborative process is well suited to unpack the complex and contextual nature of the messaging (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013; Guba & Lincoln, Citation1994; Naganathan et al., Citation2022).

In line with our expectations, national myths and symbols were central to both Biden and Trump’s campaigns (see ). Unexpectedly, Biden used them in a greater proportion of his tweets than Trump (36% to 27%, respectively). Following the billing of the election as a “battle for the soul of the nation,” the candidates drew upon distinct sets of myths and symbols to present opposing visions of America’s national identity. Here the candidates’ campaigns largely reflected the long-running conflict between the civic and ethnic traditions, with Biden more commonly referring to the former, and Trump more commonly referring to the latter. The split here is striking. Biden used civic myths and symbols in approximately 90% of his nationalist tweets, while Trump used ethnic myths and symbols in approximately 88% of his nationalist tweets. To a lesser extent, both candidates also referred to the opposing tradition. Both candidates also occasionally combined the two traditions in one message (Biden did this over 20 times, and Trump did this over 30 times).

Table 2. Myths and symbols of national identity in Biden and Trump’s tweets.

The importance of national identity to both campaigns – irrespective of whether they used the civic or ethnic traditions – is brought into relief when considering it in relation to other themes broached by the candidates (see ). National identity was the third most popular theme overall, behind “current events and public policy,” and “attacking political actors and opponents.” In terms of specific public policy issues, Trump’s focus was law and order (over 360 tweets), foreign policy (over 290 tweets, of which approximately 100 referred to China), and the economy (over 280 tweets). Biden’s campaign touched upon a broader range of public policy issues; he also focused on the economy (in over 220 tweets) and healthcare (in over 110 tweets). Given the timing of the election, as we would expect, COVID-19 was also a major public policy topic for both candidates – although more so for Biden (over 330 tweets) than Trump (under 200 tweets). In tweets related to “political actors and opponents,” Biden focused squarely on Trump, as we would expect from a challenger. Trump similarly focused on Biden, but also spent considerable time criticizing the “radical left,” Democrats, and even fellow Republicans (occasionally). Both candidates tweeted about “campaign announcements” (mentioning events, polls, etc.) and “democracy and electoral processes” (mentioning the state of democracy, mail in voting, voting rights, etc.) to a similar extent. In terms of the other key themes, as expected, Trump referred to the media and criticized the establishment much more than Biden. Meanwhile, Biden’s tweets referred to gender more than Trump.

Table 3. Main themes in Biden and Trump’s tweets.

While both candidates referred to myths and symbols of national identity as a theme in its own right, as indicates, they also often paired them with other themes. When this occurred, the myths and symbols functioned as framing devices for the other themes by infusing them with nationalist meanings. In these instances, the candidates also sought to further reinforce these intended meanings through strategic use of positive and negative sentiment. To better understand these elements of Biden and Trump’s Twitter communication, the following sections examine each of their campaigns in depth. We focus on how the candidates invoked the five referents of national identity (people, religion, history, territory, and place in the world) and used sentiment to construct in- and out-groups to present opposing visions of America’s national identity.

The Civic Nationalism of Biden’s Tweets

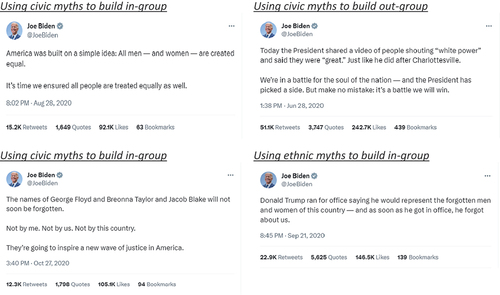

Biden drew heavily from myths and symbols associated with the civic tradition of American identity to campaign on the idea that he was best placed to reunite America after a period of division wrought by the illiberalism of Trump (see for a sample of indicative tweets). To do so, Biden argued that Americans needed to restore their true (civic) identity – their “soul,” in his words (June 28, 2020; July 20, 2020).Footnote6 Biden’s nationalist rhetoric drew most heavily from civic nationalist myths and symbols associated with the American people (over 350 tweets) and its history (over 220 tweets), while he drew from civic myths associated with America’s place in the world, its religion and its territory less frequently (over 85, 30, and 20 tweets, respectively).

Among the clearest ways that Biden evoked the civic mythology in his nationalist rhetoric was by depicting America as a fundamentally diverse community that is inclusive of people from all backgrounds. The ties that bind this diverse community, according to Biden’s tweets, is a shared belief in the equality of all its citizens: “America was built on a simple idea … all men – and women – are created equal” (August 28, 2020). In many respects, and in various ways, Biden built on this core conception of the “true” character of the American people in his nationalist messaging.

In a related manner, Biden invoked civic myths of the American people to put forward a positive message about immigration, tweeting, for example, that America was “built through immigration” (October 20, 2020). Civic myths related to the American people also framed Biden’s tweets about racial justice for black Americans, which he represented as a core value (July 11, 2020) and a pillar of realizing a more inclusive society and economy (July 28, 2020). The civic myth of the American people similarly framed his support of the Black Lives Matter movement (October 27, 2020: 1:16pm), as well as his opposition to the unequal treatment of black Americans by police and the criminal justice system (October 27, 2020: 3:40pm).

Biden’s nationalist rhetoric often built upon these civic conceptions of the American people by also drawing on civic myths and symbols related to America’s history. Here Biden’s messages were anchored by the progressive myth that America’s destiny is to overcome its various illiberalisms, in order to progress to a unified future when all Americans are treated equally. With this myth as a framework, Biden depicted the election as a critical moment in the nation’s progress toward its civic destiny – it was “about who we are as a nation, what we believe – and maybe most importantly – who we want to be” (October 27, 6:58pm). Similarly, he tweeted that “America is at an inflection point,” in which it could choose a darker, divided path, or it could choose “to heal, to be reborn, to unite … [to take a] path of hope and light” (August 23, 2020). By choosing the latter path (by voting for him), Biden also suggested that Americans would bring about the “more perfect union” envisioned by Obama (August 17 and 25, 2020; June 19, 2020). The progressive historical myth also provided a framework for Biden’s understanding of the struggle for racial justice – on this issue, America could either regress by following Trump or finally realize its true ideals of equality and justice (October 18, 2020; August 22, 2020; July 4, 2020). In addition to civic myths related to the American people and their history, Biden also invoked civic myths related to their exceptional place in the world as a “beacon of hope” (June 20, 2020) and as a leader and protector of democracy (August 18, 2020).

Biden similarly drew from these civic referents of peoplehood and history in his identification of the main threats to his vision of American identity. Notably, Biden’s tweets identified racism and ethnic nationalism (August 3, 2020; Aug 12, 2020; August 31, 2020), alongside Trump as the central exponent of these ideologies (October 7, 2020), as the main threat to the “true” American nation grounded in liberalism and equality for all. Similarly, Biden also regularly criticized law enforcement and its treatment of black people in America – tweeting that the violence, civil rights violations, and unequal treatment they receive were not aligned with the true values of America (August 28, 2020; September 24, 2020). Biden linked Trump to these issues, suggesting that his “law and order” agenda threatened America’s values and its minority communities (August 31, 2020; September 3, 2020). This line of argument – that those who sow division were a threat to the realization of America’s true identity – was the dominant way Biden constructed his out-groups. As such, Biden’s criticism of Trump was deeper than just citing his support for white nationalist and racist ideas (though he did that as well, see October 22, 2020); he presented Trump as fundamentally antithetical to America’s civic identity, which made him “unable and unfit to bring the country together to overcome its threats and challenges” (July 29, 2020; October 18, 2020).

Biden’s use of the civic tradition as a central frame for his campaign can also be seen in how his tweets combined the core referents of nationalist myths and symbols with sentiment. When employing civic myths and symbols, Biden used clearly positive language about 82% of the time. This was particularly apparent when he discussed black people and people of color, about whom he was positive about 86% and 82% of the time, respectively. Relatedly, when tweeting about Black Lives Matter and protests for racial justice, Biden was overwhelmingly positive (83% of the time). This way of positively framing minority groups and related policy priorities reflects an inclusive nationalism centered on a civic conception of the American people. In contrast, when he discussed law and order issues, Biden was much more mixed in his use of positive and negative language (he was positive about 45% of the time, and negative about 55% of the time) – suggesting that Biden was conflicted on whether the criminal justice system supported or hindered his civic vision of American identity.

While the civic tradition was central to Biden’s campaign, he did occasionally tweet in ways that hinted at the ethnic tradition – although his messaging here was often implicit and very subtle. One of the ways Biden did this was by combining elements of both civic and ethnic myths. This intermixing was noticeable, for example, when Biden referred to America’s exceptional place in the world. Generally, when Biden invoked notions of American exceptionalism, he rooted them in civic myths by highlighting America’s liberal ideals: “America is an idea stronger than any army and bigger than any ocean … more powerful than any dictator or tyrant” (August 18, 2020). However, at times, Biden would also imply – subtly – that America’s greatness stems from the special, innate characteristics of its people – that the reason they can achieve anything is because “the American people are tough, resilient, and always fully of hope” (June 23, 2020). Or, that “there’s no greater economic engine in the world” because of “the hard work and ingenuity of the American people” (September 28, 2020). While there is only a subtle difference in these examples, they do show how Biden was able to draw from different sources of exceptionalism – one rooted more in the civic ideals of the nation, the other rooted more in the purported unique characteristics of the American people. Perhaps even more importantly, Biden’s tweets on American exceptionalism show how rhetoric can draw from either tradition to construct an exclusionary nationalist message (i.e., in these instances, the common theme is that America is superior to other nations).

More explicitly, we also saw Biden use elements of the ethnic tradition in relation to religion. He emphasized that he was a Catholic, and that it was his religious values and faith that made him ready to lead America (Nov 1, 2020).Footnote7 In one instance, he even invoked a religious (rather than liberal) grounding for America’s national identity, tweeting that his commitment to protect American values stemmed from the fact they aligned with his Catholic values: “my Catholic faith drilled into me a core truth – that every person on earth is equal in rights and dignity. As president, these are the principles that will shape all that I do, and my faith will continue to serve as my anchor … ” (October 29, 2020). Biden also subtly invoked the ethnic myth that the “true” American homeland exists in small towns peopled by native-born, white Christians, rather than in the more diverse large cities. Here he would tweet about how his own values – i.e. true American values – were shaped by his upbringing in Scranton (which he juxtaposed with Trump’s home on “Park Avenue”), and how it is the “hardworking people” in these types of towns that really make America run (Nov 1, 2020; Nov 2, 2020). While Biden is clearly playing class politics here, he is also subtly implying that his upbringing in a working class (white) family from Scranton makes him a special ally of similar types of (white) people. As one tweet stated: “Scranton, Pennsylvania, isn’t just where I’m from – it’s the people I’m for” (Nov 2, 2020). Biden even adopted one of Trump’s favored codes for referring to white, working-class Americans: “after campaigning in 2016 to lift up the ‘forgotten man,’ President Trump has completely lost sight of working people” (October 30, 2020). Of course, much more often than not, Biden used civic myths to project a broadly inclusive message. Nevertheless, in several select instances, in our interpretation, his tweets subtly shifted to a more targeted (white, Christian) working class audience.

The Ethnic Nationalism of Trump’s Tweets

Trump’s Twitter communication was grounded in the ethnic nationalist tradition of American identity (see for a sample of indicative tweets). He centered his messaging with a narrative that the nation was losing its greatness because of the growing power of a series of internal and external threats abetted by Biden. Accordingly, the election was “a battle to save the Heritage, History, and Greatness of our Country” (June 30, 2020). Race – and whiteness – were central in Trump’s messaging: the group that was under threat was the white, Christian majority. Through this narrative, Trump cast himself as a heroic figure, who alone was capable of protecting the white majority and returning it (and thus the nation’s true identity) to greatness – such that it would “reign” again (July 13, 2020). In crafting this narrative, Trump drew most often from ethnic myths and symbols associated with America’s history (over 260 tweets) and its people (over 250 tweets). He also relied heavily on ethnic notions of America’s territory (over 170 tweets), while drawing less often from the ethnic tradition when discussing America’s place in the world and its religion (over 90 and 40 tweets, respectively).

Contrary to Biden’s explicit use of civic nationalist myths and symbols, Trump’s use of ethnic nationalist myths and symbols tended to be implied. Rather than stating his support for the ethnic tradition outright, Trump would allude to it using codes (i.e. dog whistles). This mirrors his strategy in 2016, and it follows trends in other western countries where the explicit defense of national identity on the basis of ethnicity, race, or religion remains somewhat taboo (Schertzer & Woods, Citation2021). For this reason, Trump does not refer to white people or whiteness directly. Nevertheless, we found that the ways in which Trump’s tweets referred to America and its various threats drew from ethnic nationalist myths – often combining referents to people, religion, history, and territory – to depict “true” Americans as native-born, Christian, and rural.

With respect to the American people, Trump used coded language to refer to an embattled, but hidden (white) majority group – a “vast silent majority” (June 28, 2020). Trump identified with this group, and directed most of his tweets to them. We find allusions to the ethnic characteristics of this “silent majority” in Trump’s use of plural first-person pronouns, which he would commonly juxtapose with plural third-person pronouns – often in reference to something of “ours” that “they” are threatening to take away from “us.” For instance, when discussing the movement to remove historical monuments linked to white supremacy, Trump declared: “they are determined to tear down every statue, symbol, and memory of our national heritage” (Trump, Citation2020 [emphasis added]). Here, the group to which Trump refers with the pronoun “our” is not explicitly stated, but through the context of the messaging, it is clear that Trump is drawing from ethnic myths associated with both American peoplehood and its history: he is emphasizing the greatness of its white people, and downplaying their historical maltreatment of people of color. Similarly, Trump also alluded to an ethnic definition of the American people – combined with myths about the homeland of the true American nation – in his tweets about the threat that “dangerous” cities posed to “suburban housewives:” “the ‘suburban housewife’ will be voting for me. They want safety & are thrilled that I ended the long running program where low income housing would invade their neighborhood” (Aug 12, 2020). Here, Trump does not explicitly state that these “suburban housewives” are white people, nor does he state explicitly that the dangerous people in “low income housing” are not white people, but these meanings are clearly implied when considered in the context of the long history of racist dog whistles about white American women being targeted by dangerous black men (Haney-Lopez 2014: 20). We see this tendency also in Trump’s regular evocation of veterans and hardworking middle-class Americans as the true members of the nation, those that are working to protect “us” while being threatened from “them” (October 31, 2020: 10:05pm; October 30, 2020).

Trump also drew from the ethnic tradition in his references to various groups whom he claimed threatened America’s greatness – turning in particular to myths and symbols associated with American history (and its future). Here his most prominent threat was the “radical left.” While on its face, Trump is referring to a classic “right-left” political cleavage, he often paired “radical left” with ethnic and myths and symbols. A common rhetorical strategy here was to simply suggest that leftist ideas are not American – hence, he depicted the election as a “choice between the AMERICAN DREAM and a SOCIALIST NIGHTMARE” (October 29, 2020). Another strategy was to link the “radical left” with the movement for racial justice – implying that the left was more concerned with “them” (black people) than “us” (white people). For instance, Trump tweeted about how the “radical left” and its “critical race theory” was indoctrinating people and threatening “our history” and, as such, he would “restore PATRIOTIC EDUCATION”) (October 31, 2020). Similarly, Trump linked the “radical left” to BLM protestors (August 5, 2020), tweeting that these “sick and deranged” people “would destroy our American cities” – and that only he could protect America from them, so that it could “go on to the Golden Age” (July 28, 2020). This tweet also illustrates how Trump combined ethnic myths related to people and territory to frame cities as threats. As with his tweets about “suburban housewives,” Trump made use of well-known racist dog whistles to claim that the cities were overrun by criminals, thugs, looters, and anarchists, which he suggested threatened suburban America (July 14, 2020; July 26, 2020; Sept 8, 2020).

In addition to these internal threats, Trump often referred to external threats, particularly China. Here Trump again drew upon the ethnic tradition. He often did this by combining the ethnic myth that there are strict cultural boundaries between the American people and foreign outsiders, layering on fears associated with COVID-19. In Trump’s tweets, COVID-19 was a foreign, specifically Chinese, virus – it was the “Wuhan Virus,” the “China Virus,” and the “China Plague” (July 20, 2020; Sept 30, 2020; October 7, 2020). More generally, Trump also referred to China as a threat to America’s dominant place in the world, and to “regular, hardworking” Americans’ way of life (Nov 2, 2020). Here his messaging often combined with another frequent threat: “globalists” – of which, according to Trump, Biden is a central figure (Sept 18, 2020; Nov 2, 2020: 4:24pm) – working to take the American dream away from real, hardworking Americans.

For Trump, Biden was the linchpin that tied together these various threats. A win for Biden would therefore hasten America’s decline from greatness. One series of tweets exemplifies this perspective:

Every corrupt force in American life that betrayed you and hurt your [sic] are supporting Joe Biden: The failed establishment that started the disastrous foreign wars; The career politicians that offshored your industries & decimated your factories; The open borders lobbyists … that killed our fellow citizens with illegal drugs, gangs & crime; The far-left Democrats that ruined our public schools, depleted our inner cities, defunded our police, & demeaned your sacred faith & values; The Anti-American radicals defaming…our noble history, heritage & heroes; and ANTIFA, the rioters, looters, Marxists, & left-wing extremists. THEY ALL SUPPORT JOE BIDEN!

Trump’s tendency to rely on the ethnic tradition is clear when we consider how he employed sentiment when discussing aspects of the American people in his communication. For example, Trump was largely negative when discussing black people: in tweets mentioning black Americans, he used negative language about 77% of the time. In our view, this highlights a contradiction in Trump’s tweets, whereby his occasional courting of black voters was negated by the negative sentiment that he used to refer to them. This contradiction is evident in the many tweets that refer to black Americans alongside themes of urban crime and poverty. Trump was also almost universally negative on issues related to racial justice – with regard to Black Lives Matter, he used negative language about 90% of the time. Similarly, when discussing immigration – a topic he mentioned much less often in 2020 compared with 2016 (Schertzer & Woods, Citation2021) – Trump used negative language nearly 70% of the time in keeping with his longstanding representation of immigration as a threat to the American people (e.g., October 27, 2020).

While Trump’s tweets were firmly associated with the ethnic tradition of American identity, like Biden, he also occasionally used the opposing tradition. For instance, Trump often tweeted about how he was seeking to protect civil rights, and how he was the leader of the party that helped to establish the civic values of liberty, equality, and justice for all (June 20, 2020). He also tapped into the civic myth of the American people – that it is an inclusive community that accepts people regardless of their “race, religion, or creed” (November 1, 2020). In keeping with this theme, Trump also occasionally tweeted in languages other than English (July 15, 2020; November 2, 2020: 5:24pm). The clearest examples of Trump’s use of the civic myths were in relation to his efforts to court black and Latino Americans: “Joe Biden has been a disaster for African Americans and Hispanic Americans – I am fighting for citizens of every race, color and creed” (October 31, 2020). He repeated similar tweets nearly 50 times in the campaign – a significant break from his 2016 campaign, in which he overwhelmingly referred to black people, and particularly Hispanic Americans, as malign outgroups (Schertzer & Woods, Citation2021). At the same time, while Trump did use civic myths and symbols to project a more inclusive message, he was sometimes ambiguous when using them – even mixing them with ethnic myths and symbols. For example, while Trump praised the right to religious liberty in tweets, he also had tweets about how America is ultimately Christian as “ONE GLORIOUS NATION UNDER GOD!” (October 31, 2020). Similarly, Trump’s occasional positive tweets about black Americans were countered by the large number of negative tweets about racial justice and BLM.

Discussion: Nationalist Polarization and the Threat to Democracy

The primary takeaway from our analysis is that the longstanding struggle between the civic and ethnic nationalist traditions of American national identity was a central theme of the 2020 presidential campaign. Biden largely drew from the civic nationalist tradition to campaign on the idea that he could save America’s “soul” by defeating Trump and the anti-American forces of illiberalism and racism, and thereby recommit the nation to its true liberal destiny. By contrast, Trump mainly drew from the ethnic nationalist tradition to campaign on the idea that he could restore America’s greatness by defeating Biden and the various anti-American forces that were threatening America’s true (white) identity. Biden and Trump’s willingness to take up these opposing traditions in order to frame each other as a threat to America – as antithetical to the values and “true” identity of the nation – suggests that there is a significant nationalist dimension to presidential politics. In this concluding section, we elaborate on these findings – focusing particularly on this process of ‘nationalist polarization’ and its implications for the state of American democracy.

Students of American politics will likely find it unsurprising that Trump’s campaign communication was framed by ethnic nationalism, and that Biden’s campaign communication was framed by civic nationalism. This finding is consistent with recent work on nationalist rhetoric in American campaign communication arguing that nationalism is used, and contested, by candidates on the right and the left (e.g., Bonikowski et al., Citation2022; Lieven, Citation2016; Mason, Citation2018; Sides et al., Citation2018). It also follows the literature drawing attention to the growing role of identity – particularly whiteness and race – in American politics today (e.g. Abramowitz & McCoy, Citation2019; Hooghe & Dassonneville, Citation2018; Jardina, Citation2019). By re-purposing the civic-ethnic dichotomy and by distinguishing between five foundational referents of national identity, we have added precision to the work mapping nationalist rhetoric in presidential politics. Furthermore, by drawing on research examining the development of American political culture, we have added a historical perspective to demonstrate the deep roots of the competing nationalist traditions of American identity that were at play in 2020.

Highlighting the historical roots of Trump and Biden’s competing nationalist visions helps us understand the ongoing role that they play in shaping contemporary politics. Contra the assumptions of “top-down” approaches to nationalism and culture (Breuilly, Citation2009; Brubaker, Citation2004; Hobsbawm & Ranger, Citation1983), Biden and Trump did not simply “invent” new traditions of American national identity to fit the particularities of their campaigns. Rather, the opposite occurred – both Trump and Biden’s campaigns largely reflected preexisting traditions of national identity. From this historical perspective, the 2020 presidential campaign looked less like a struggle over contemporary issues, and more like the latest iteration of a longstanding struggle over America’s national identity. And, while it is true that both Biden and Trump’s campaigns clashed over leading issues of the day – such as policing or immigration – they largely did so by framing these issues in relation to the struggle over national identity. In doing so, they sought to suffuse their positions with meaning – by conveying to the electorate that what was truly on the ballot in 2020 was the future of America’s identity. As we know from American history, when these two competing visions for the foundations of American national identity rise to the fore and become more overt, political instability and conflict has tended to follow (see Schertzer & Woods, Citation2022: Chapter 4).

The overt embrace of the competing visions of national identity is a worrying development in the context of increasing political polarization and debates over democratic backsliding in America. In theory, differences over policy can be resolved rationally by debating the opportunity cost of taking one position over another – this is, in part, the kind of process that Habermas (Citation1989) suggested occurs in a properly functioning democratic public sphere. However, differences over the interpretation of meaning cannot be resolved through ratiocination. Instead, meaning is conveyed through culture and apprehended through emotions (Alexander et al., Citation2006). In this regard, we saw how Biden and Trump each sought to convince their supporters of the “truth” of their respective campaigns by appealing to their emotions through myths and symbols of national identity. To the extent that they succeeded, their supporters are unlikely to be convinced otherwise by appeals to reason. This is further complicated by the fact that Trump and Biden embedded their appeals in a cultural conflict with deep historical roots. The persistence of this conflict through time suggests that efforts to bridge America’s political polarization will be a challenging prospect, to say the least.

There are also specific implications associated with national identity being a key object of contestation in presidential elections. National identity develops in relation to perceived external others – we come to know who “we” are by identifying who “we” are not. Therefore, when national identity is contested, the possibility is raised that opponents will be depicted as an external Other who do not represent who “we” are. The Biden and Trump campaigns raised these stakes even further: they depicted one another, not just as unrepresentative of American identity, but as a grave threat to its identity. This was particularly the case for the Trump campaign. Whereas Biden depicted those that do not share an inclusive, civic vision of American identity as a threat, Trump targeted and framed segments of the population, relying on ascriptive criteria like race and religion, as a threat to the (white) majority. Given how the candidates framed each other, it is unsurprising that they both used apocalyptic language when talking about the possibility that their opponent might win the presidency. In their terms, a win for their opponent represented an existential threat to America’s national identity.

This framing of opponents has potentially serious consequences for American democracy. There has recently been much research and debate on whether America’s polarization is causing its democracy to “backslide” (e.g. Ahmed, Citation2022; Broockman et al., Citation2022; Graham & Svolik, Citation2020; Lieberman et al., Citation2019). Our findings highlight the role of nationalism in this process. As John Stuart Mill was aware, some minimal sense of shared national identity – of “common sympathies,” to use his term – among the electorate is essential for successful liberal democracies (Mill, Citation1977 [1861], 546). In short, there first needs to be a shared definition of the “people” in order to have “rule by the people.” Nationalism has played a key role in liberal democracy by giving the notion of “the people” some meaning – by merging the abstract “people” with the more concrete “nation” (Yack, Citation2001). It is this shared and widely accepted idea that democratic institutions are controlled by, and represent, the people qua nation that grants them legitimacy. If elections cleave over the very definition of who “we” are, then there is a risk that the losing side will not recognize the winning candidate’s legitimacy.

In making this argument, our reasoning is no doubt influenced by the events of January 6th, 2020, and the ongoing refusal by many of Trump’s supporters to accept Biden’s legitimacy. We also acknowledge that the events of January 6th and beyond were triggered by much more than campaign rhetoric – and that all the various causal forces need proper testing and debate. Nevertheless, in our view, the fact that the leading candidates of the 2020 campaign framed one another as “un-American” at the very least provides insights into why so many Americans continue to question the legitimacy of its outcome.

Looking ahead, unresolved questions for future research relate to how the 2020 election compared to previous elections. Was the centrality of the conflict over national identity typical of American presidential campaigns? Or, does 2020 stand out for the salience of this conflict? Has the salience of this conflict been increasing across recent presidential elections? Is it related to idiosyncratic factors associated with Trump or are there other, structural factors at play? Either way, given the fall out of the 2020 election, and given the fact that – at the time of writing – it looks increasingly likely that Trump and Biden will again be on the ballot in the 2024 election, we suggest that America’s cultural conflict will be even more salient in that campaign, with a high potential for grave consequences.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the thoughtful comments and suggestions to earlier an version of the paper from the participants of the American Political Science Association’s panel on ‘Fragmentation, Polarization and National Identity.’ We are similarly grateful to the participants of seminars on the paper held at the Center for Cultural Sociology at Yale University, and the School of Media and Communication at the University of Leeds.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eric Taylor Woods

Dr. Eric Taylor Woods is an Associate Professor in Sociology at the University of Plymouth. His current research examines the intersections of politics, culture, and media-with a particular focus on how these phenomena relate to nationalism and identity.

Alexandre Fortier-Chouinard

Alexandre Fortier-Chouinard is a PhD candidate in Political Science at the University of Toronto. He specializes in political engagement, campaign promise fulfillment, and research methods.

Marcus Closen

Marcus Closen is a PhD Candidate in Political Science at the University of Toronto. His research examines group representation in national legislatures, with an emphasis on advanced industrialized democracies.

Catherine Ouellet

Catherine Ouellet is an incoming Assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at the Université de Montréal. She specializes in Quebec/Canadian politics and public opinion, with an emphasis on lifestyle and the construction of social identities.

Robert Schertzer

Dr. Robert Schertzer is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto. His current research focuses on the ideas, institutions and political communication related to rising nationalism in liberal democracies.

Notes

1. On June 6th Biden officially received enough delegate votes to become the Democratic nominee for the 2020 presidential election. We waited for two weeks after this date to begin capturing tweets to ensure we were focusing only on the period where Biden was positioning himself as challenger to Donald Trump, rather than his democratic competitors. This approach ensures we are focusing on the general election in our analysis, while leaving ample time to capture sufficient tweets that reflect Biden and Trump’s campaign strategy (136 days of campaigning).

2. Because we are interested in the direct messaging of the candidates, and to avoid issues with bots, we excluded re-tweets. The majority of the tweets for both candidates were collected directly from the Twitter API through an rtweet package; however, after Donald Trump was removed from the platform following January 6th, 2020, we also used www.thetrumparchive.com to ensure we captured all of his tweets. The full list and text of all tweets collected is available in our supplementary material on the Harvard Dataverse, accessible here: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AZWHQG.

3. The full codebook is available on the Harvard Dataverse, accessible here: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AZWHQG.

4. Our approach facilitates intercoder consensus through collaboration and discussion rather than reaching intercoder reliability scores by comparing coding conducted by multiple people independently (on these different approaches see Braun & Clarke, Citation2013; O’Connor & Joffe, Citation2020). At the same time, we follow many of the best practices that can facilitate intercoder reliability, notably the bifurcation between the developers of the codebook and the initial coding, the use of a data immersion phase to refine the codebook, a clear process for resolving coder disagreement and measures to mitigate power dynamics among the coders (see Lacy et al., Citation2015; MacPhail et al., Citation2015).

5. Supplementary materials – which provide more detail on this process, all Twitter data and the codebooks – is available on the Harvard Dataverse, accessible here: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AZWHQG.

6. References to tweets indicate the date that they were sent from users’ accounts. We indicate.

the time when we cited more than one tweet in a single day.

7. Earlier in America’s history (notably in the 18th and 19th centuries) Biden’s Catholic faith would have put him at odds with the WASP majority; however, as discussed earlier in the article and elsewhere, throughout the 20th century the religious boundaries of the majority group in America shifted from a basis in Protestantism (in contrast with Catholicism) to a broader Christian basis (Schertzer & Woods, Citation2022: Chapter 4). A related process has taken place, whereby Anglo-Saxon identity – as the central referent for the heritage of members of the majority group – has shifted to a more nebulose notion of whiteness rooted in European heritage. Thus, today, whiteness, European heritage and Christianity are among the key ethnic referents for membership to the American nation.

References

- Abramowitz, A. I. (2018). The great alignment: Race, party transformation, and the rise of Donald Trump. Yale University Press.

- Abramowitz, A., & McCoy, J. (2019). United States: Racial resentment, negative partisanship, and polarization in Trump’s America. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 681(1), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716218811309

- Ahmed, A. (2022). Is the American public really turning away from democracy? Backsliding and the conceptual challenges of understanding public attitudes. Perspectives on Politics, 21(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592722001062

- Alexander, J. C., Giesen, B., & Mast, J. L. (Eds.). (2006). Social performance: Symbolic action, cultural pragmatics, and ritual. Cambridge University Press.

- Arieli, Y. (1964). Individualism and Nationalism in American Ideology. Harvard University Press.

- Armstrong, J. A. (1982). Nations before nationalism. University of North Carolina Press.

- Austermuehl, F. (2020). The normalization of exclusion through a revival of whiteness in Donald Trump’s 2016 election campaign discourse. Social Semiotics, 30(4), 528–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2020.1766205

- Barreto, A. A., & Napolio, N. G. (2020). Bifurcating American identity: Partisanship, sexual orientation, and the 2016 presidential election. Politics, Groups & Identities, 8(1), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2018.1442727

- Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 611–639.

- Biden, J. R. (2020). Remarks by Vice President Joe Biden in Warm Springs, Georgia. Online. Retrieved January 5, 2023, from https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-vice-president-joe-biden-warm-springs-georgia

- Billig, M. (2005). Banal nationalism. Sage.

- Bonikowski, B., & DiMaggio, P. (2016). Varieties of American popular nationalism. American Sociological Review, 81(5), 949–980. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416663683

- Bonikowski, B., Feinstein, Y., & Bock, S. (2021). The partisan sorting of “America. American Journal of Sociology, 127(2), 492–561. https://doi.org/10.1086/717103

- Bonikowski, B., Luo, Y., & Stuhler, O. (2022). Politics as usual? Measuring populism, nationalism, and authoritarianism in US presidential campaigns (1952–2020) with Neural Language models. Sociological Methods & Research, 51(4), 1721–1787. https://doi.org/10.1177/00491241221122317

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research. Sage.

- Breton, R. (1988). From ethnic to civic nationalism: English Canada and Quebec. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 11(1), 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.1988.9993590

- Breuilly, J. (2009). Nationalism and the making of national pasts. In S. Carvalho & F. Gemenne (Eds.), Nations and their histories: constructions and representations. Palgrave.

- Broockman, D. E., Kalla, J. L., & Westwood, S. J. (2022). Does affective polarization undermine democratic norms or accountability? Maybe not. American Journal of Political Science, 67(3), 808–828. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12719

- Brubaker, R. (1999). The manichean myth: Rethinking the distinction between ‘civic’ and ‘Ethnic’ nationalism. In H. Kriesi, K. Armingeon, H. Slegrist, & A. Wimmer (Eds.), Nation and national identity: The European experience in perspective (pp. 55–72). Ruegger.

- Brubaker, R. (2009). Citizenship and nationhood in France and Germany. Harvard University Press.

- Butler, A. (2021). White Evangelical racism: The politics of morality in America. University of North Carolina Press.

- Citrin, J., Reingold, B., & Green, D. P. (1990). American identity and the politics of ethnic change. The Journal of Politics, 52(4), 1124–1154. https://doi.org/10.2307/2131685

- Eyerman, R. (2022). The making of White American identity. Oxford University Press.

- Feinberg, A., Branton, R., & Martinez-Ebers, V. (2022). The trump effect: How 2016 campaign rallies explain spikes in hate. PS: Political Science & Politics, 55(2), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096521001621

- Fitzgerald, K. (1996). The face of the nation: Immigration, the state, and the national identity. Stanford University Press.

- Gerstle, G. (2017). American crucible: Race and nation in the twentieth century. Princeton University Press.

- Graham, M. H., & Svolik, M. W. (2020). Democracy in America? Partisanship, polarization, and the robustness of support for democracy in the United States. American Political Science Review, 114(2), 392–409. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000052

- Greenfeld, L. (1992). Nationalism: Five roads to modernity. Harvard University Press.

- Guba, E., & Lincoln, Y. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). Sage.

- Habermas, J., & Press, P. (1989). The public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society.

- Haney-López, I. (2014). Dog whistle politics: How coded racial appeals have reinvented racism and wrecked the middle class. Oxford University Press.

- Hartz, L. (1955). The liberal tradition in America: An interpretation of American political thought since the revolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Hayes, C. J. H. (1960). Nationalism: A religion. Macmillan.

- Higham, J. (2002). Strangers in the land : Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925. Rutgers University Press.

- Hobsbawm, E., & Ranger, T. (1983). The invention of tradition. Cambridge University Press.

- Hobsbawm, E. & Ranger, T. (1983). The invention of tradition. Cambridge University Press.

- Hooghe, M., & Dassonneville, R. (2018). Explaining the Trump vote: The effect of racist resentment and anti-immigrant sentiments. PS: Political Science & Politics, 51(3), 528–534. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096518000367

- Horsman, R. (1986). Race and manifest destiny: The origins of American racial anglo-saxonism. Harvard University Press.

- Hutchinson, J. (1986). Dynamics of cultural nationalism: The Gaelic revival and the creation of the Irish nation state. Routledge.

- Hutchinson, J. (2005). Nations as zones of conflict. Sage.

- Ignatiev, N. (1995). How the Irish became white. Routledge.

- Jacobson, M. F. (1999). Whiteness of a different color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race. Harvard University Press.

- Jardina, A. (2019). White identity politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Jones, F. L., & Smith, P. (2001). Diversity and commonality in national identities: An exploratory analysis of cross-national patterns. Journal of Sociology, 37(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/144078301128756193

- Kaufmann, E. (2004). The rise and Fall of Anglo-America. Harvard University Press.

- King, D. S., & Smith, R. M. (2005). Racial orders in American political development. American Political Science Review, 99(1), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051506

- Kingzette, J., Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M., & Ryan, J. B. (2021). How affective polarization undermines support for democratic norms. Public Opinion Quarterly, 85(2), 663–677. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfab029

- Kohn, H. (2017 [1944]). The idea of nationalism: A study of its origins and background. Macmillan.

- Lacy, S., Watson, B., Riffe, D., & Lovejoy, J. (2015). Issues and best practices in content analysis. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 92(4), 791–811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699015607338

- Lepore, J. (2019). This America: The case for the nation. Hachette UK.

- Li, Q., & Brewer, M. B. (2004). What does it mean to be an American? Patriotism, nationalism, and American identity after 9/11. Political Psychology, 25(5), 727–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00395.x

- Lieberman, R. C., Mettler, S., Pepinsky, T. B., Roberts, K. M., & Valelly, R. (2019). The Trump presidency and American democracy: A historical and comparative analysis. Perspectives on Politics, 17(2), 470–479. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592718003286

- Lieven, A. (2012). America right or wrong: An anatomy of American nationalism. Oxford University Press.