ABSTRACT

Studies addressing the normative questions of whether social media use positively or negatively affects citizens’ levels of democratic engagement and satisfaction with democracy have produced mixed findings. This study tests the proposition that political polarization plays an important contingent role in explaining these relationships. Combining Varieties of Democracy (VDEM) and World Values Survey (WVS) data, this study examines how issue polarization and affective polarization at the country level shape the relationships between social media use for political information and democratic outcomes in 27 developed democracies. The findings show divergent consequences of social media use contingent on affective polarization. In the countries with high affective polarization, social media use increased democratic engagement (i.e. participation and voting) and decreased satisfaction with democracy (i.e. political satisfaction and perceived quality of democracy), which may have implications for democratic erosion and backsliding. In the countries with low affective polarization, social media use increased the perceived quality of democracy but had no effect on political satisfaction. Issue polarization had a limited contingent influence. The findings contribute to the literature by explicating the dynamics of country-level affective polarization that can shape and contextualize the relationship between social media use and democratic engagement in democracies across the world.

An estimated 60% of the world’s population uses social media (Statista, Citation2023). For citizens in many democracies, social media platforms have become sources of information that shape their political attitudes and decisions. Against this background, political communication scholars have explored two overarching research questions related to the normative role of social media in politics: first, whether social media increases democratic engagement, such as voting in elections or other forms of political participation (Boulianne, Citation2020), and second, to what extent social media fosters political information environments showing that governments are responsive to the demands of their citizens, which is an important precursor of satisfaction with democracy (Ceron & Memoli, Citation2015; Placek, Citation2023). However, these studies have produced mixed findings.

To resolve the issue of these contradictory findings, this study examines the contingent role of political polarization, which we propose shapes the relationships between social media use and the two types of democratic outcomes mentioned above. Public and scholarly discourses about political polarization have posed it as a direct threat to democracies globally (Gidron et al., Citation2020). Diverging opinions, attitudes, and beliefs on policy issues as well as intergroup dislike, distrust, and hostility among political elites and citizens (Iyengar et al., Citation2019) can undermine democratic norms, such as rational debate (Rossini, Citation2022), which can lead to democratic backsliding and gradual erosion in the quality of democracy (McCoy & Somer, Citation2018). Political polarization also shapes countries’ political information environments. In highly polarized countries, political actors’ strategic use of rhetoric can enlarge cleavages in society by stoking in-group/out-group resentment and even hate (McCoy et al., Citation2018). This rhetoric, in turn, can be amplified exponentially across social media among users who come across and share political content (Kubin & von Sikorski, Citation2021). Thus, the degree of political polarization in a country should also be reflected in the types and valence of political information in its social media space (Urman, Citation2019).

Based on this argument, we test the moderating role of two types of political polarization, namely affective and issue polarization, on the relationships between social media use for political information and democratic outcomes in 27 established democracies. Among these are countries that are known to have very polarized politics, such as the United States, Brazil, and Malaysia, and others that do not, such as Canada, New Zealand, and Japan. By testing these potential moderators, this study addresses several gaps in the literature. First, it helps explain the divergent findings in the literature on the relationships between social media use and democratic outcomes. Second, it provides a more nuanced cross-national understanding of the dynamics of political polarization and social media, given that the scholarship to date has focused mostly on the United States (Urman, Citation2019). Third, it highlights the important contextual role of political polarization among other factors (e.g., “free” and “other” press systems; Boulianne, Citation2019), which can inform the design of meta-analyses and cross-national comparative research on the democratic consequences of social media use.

Social Media, Democratic Engagement, and Satisfaction with Democracy

Normative theories of democracy presume an information environment that informs citizens on the important political and social issues that affect their lives and provides them with opportunities to express their views to elected government officials (Delli_carpini, Citation2004). From a rational choice perspective, such an environment lowers the costs of participation in politics for citizens as it reduces the time, money, and effort required to access relevant information and news that inform their political actions and choices (Vissers & Stolle, Citation2014). Legacy media such as newspapers and television have long served this information function to increase democratic engagement (McLeod et al., Citation1999), but in the past two decades social media platforms such as Facebook have gained popularity as sources of information. According to the 2022 Reuters Institute Digital News Report, 42% of online users in the United States use social media as a source of news, which is in the middle range between democracies in the lower range, such as Japan (28%) and Germany (32%), and those in the higher range, such as Chile (70%) and Thailand (78%) (Newman et al., Citation2022).

Social media use is not universal among citizens but has nevertheless altered the dynamics of political communication in various ways, and these processes can be understood through the “network media logic” framework (Klinger & Svensson, Citation2015). Based on previous theorizing of “media logic” as a form and process in which media transmits communication (Altheide, Citation2016), “network media logic” encompasses different “communication norms and practices related to media production, distribution and usage” (p. 1246), which stands in contrast with the “mass media logic” of legacy media. For example, based on the logics of production and distribution, election candidates can engage in “personalized politics” by bypassing the traditional gatekeepers of information (i.e., professional media and journalists) and disseminating information directly to supporters and potential voters through social media posts and tweets (McGregor, Citation2017). Furthermore, these users are not mere recipients of information as they can also serve as “intermediaries” to increase the virality of the information by sharing it across “networks of like-minded others” (Klinger & Svensson, Citation2015, p. 1246). These logics were demonstrated by Wojcieszak et al. (Citation2022) in their study of Twitter users, who they found were overwhelmingly engaged with and shared information from politically aligned in-group actors (i.e., politicians, pundits, and news media) rather than those from the out-group. This is not to say that the social media space is devoid of legacy media presence: the mass media and network media logics overlap because news media organizations and journalists have also appropriated social media to develop connections with audiences and promote their content (Gulyas, Citation2013). Nonetheless, because of the logic of media usage that allows users on social media to engage in selective exposure and customize their information environments (Merten, Citation2020), the news media and journalists must compete with other political actors to gain citizens’ attention.

The three aspects of the network media logic (production, distribution, and media usage) are intertwined, and collectively they can further reduce the costs for citizens who use social media to obtain timely and relevant political information that facilitates democratic engagement compared with those who do not use social media. This assertion is supported by several meta-analyses of the literature, although not all coefficients of previous studies were statistically significant (Boulianne, Citation2019; Skoric et al., Citation2016). A possible reason is that these analyses have usually pooled different measures of democratic engagement. Voting in elections is often considered in the political literature to be one aspect of political participation, alongside others such as donating to campaigns and contacting government officials (Brady et al., Citation1995). From a cross-national comparative perspective, however, voting should be considered a distinct form of democratic engagement because some countries have high voter turnout but relatively low citizen engagement in politics, for reasons such as compulsory voting (e.g., Singapore and Peru) or political culture (e.g., Japan). Therefore, in this study, we consider voting to be separate from political participation, and we propose the following base hypothesis:

H1:

Social media use for political information is positively related to (a) political participation and (b) voting.

Compared with those attending to democratic engagement, fewer studies of social media have examined satisfaction with democracy, despite it being one of the most important variables in comparative politics and public opinion research (Singh & Mayne, Citation2023). Normatively, satisfaction with democracy is closely tied to the notion of government responsiveness to citizen demands, which is required to maintain political trust and the legitimacy of the democratic system (Linde & Ekman, Citation2003). Two important indicators of satisfaction with democracy are political system satisfaction, which emphasizes the overall performance of the political institutions and actors in meeting the normative standards of democracy, and perceived quality of democracy, which reflects individuals’ judgments on the relative state of democracy in their countries (Mayne & Hakhverdian, Citation2016). For a long time, the legacy media in both offline and online forms served the normative role of increasing citizens’ political learning and trust in political institutions as part of a “virtuous circle” (Norris, Citation2000). Studies on the role of social media, however, have offered mixed findings. Based on a survey with respondents from 27 European countries, Ceron and Memoli (Citation2015) found that Internet use (i.e., “Web 1.0 news source”) was positively related to satisfaction with democracy, whereas social media use (i.e., “Web 2.0 news sources”) was negatively related, especially when there were high levels of political disagreement. They attributed this finding to social media being an unmediated and unfiltered space in which users can be exposed to anti-democratic and counter-attitudinal views. This is understandable from the network media logic perspective because public actors with populist or radical agendas can easily and cheaply use social media to disseminate among user networks their anti-system ideologies and views. Even more serious is the spread of misinformation and hate speech by such actors, which can further undermine democratic attitudes (Kuehn & Salter, Citation2020). A longitudinal analysis of respondents from 11 Central and Eastern European countries by Placek (Citation2023) offered the more nuanced finding that the relationship between social media use and satisfaction with democracy was positive when a country’s democracy was functioning properly (i.e., a stable liberal democracy score over time) but was negative under conditions of democratic backsliding (i.e., a decrease in the liberal democracy score over time). This intriguing finding suggests that underlying political cleavages in society can play an influential role on the social media and satisfaction with democracy relationship, which is a point that we expand upon below. Given the mixed findings on the direct relationship, we raise the following research question:

RQ1:

Is social media use for political information positively or negatively related to (a) political satisfaction and (b) perceived quality of democracy?

Political Polarization and Democratic Outcomes

In recent years, scholars and commentators have framed political polarization as a direct threat to democracy (Gidron et al., Citation2020), and one of its manifestations is the shaping of political communications on social media (Kreiss & McGregor, Citation2023). Two distinct forms of political polarization are commonly emphasized in the literature: issue polarization and affective polarization (Kubin & von Sikorski, Citation2021). These two forms of polarization can shape the relationships between social media use and democratic outcomes in different ways.

Issue/Affective Polarization, and Democratic Engagement

Issue polarization is characterized by increasing attitude extremity on policy issues among the mass public (Mason, Citation2013), whereas affective polarization posits that partisanship represents an important social identity that can exacerbate positive feelings toward the in-group and animosity toward the out-group (Iyengar et al., Citation2012). Although ideological extremity is not a necessary condition for affective polarization, the two are related (Mason, Citation2018). Political parties offer citizens distinct candidate choices and their issue and policy differences serve as heuristic cues that reduce the cognitive effort of voters in making their decisions, which should increase political participation (Levendusky, Citation2010). Countering this perspective is the argument that issue polarization demobilizes voters because most citizens tend to be centrists and the extreme positions engendered by polarized elites could lead to ideological conflict that turns off the electorate (Fiorina & Abrams, Citation2008). Affective polarization is manifested by the strengthening of partisanship toward the in-group as a form of social identity (West & Iyengar, Citation2020), which can elicit action-oriented emotions, such as anger and enthusiasm, that drive political participation (Huddy et al., Citation2015). Negative sentiments toward out-groups can also drive political activities, such as donations, volunteering, and voting on behalf of the in-group (Iyengar & Krupenkin, Citation2018). There is evidence that affective polarization is an important driver of political engagement even when controlling for issue polarization (Mason, Citation2015), but Wagner’s (Citation2021) analysis of 166 elections in 51 countries showed that affective polarization but not issue polarization had a robust positive relationship with political engagement and voting. Given these mixed findings, we raise a second general research question:

RQ2:

What are the relationships between issue/affective polarization and (a) political participation and (b) voting?

Issue/Affective Polarization and Satisfaction Toward Democracy

Research has suggested that citizens are more satisfied with democracy when they perceive greater heterogeneity in the issue positions of political parties, as this gives them more electoral choices (Ridge, Citation2021). This implies a positive role for higher levels of issue polarization. High levels of affective polarization, however, can come at the expense of such core normative features of democracy as compromise, consensus, deliberation, and tolerance, which over time can lead to a gradual deterioration of the quality of democracy (Somer et al., Citation2021). Citizens are more concerned with winning at all costs, which amplifies hostile feelings and bias against those with opposing political views (Wojcieszak & Warner, Citation2020). More extreme voters are also more likely to place partisan interests above democratic values and are more willing to compromise democratic norms for their ideological agendas (Svolik, Citation2019). Although some country-level analyses have found affective polarization to be related to democratic backsliding (Orhan, Citation2022) and the erosion of democratic quality (Somer et al., Citation2021), Broockman et al. (Citation2022) found no discernable effects of affective polarization on democratic outcomes. We thus raise the following further research question:

RQ3:

What are the relationships between issue/affective polarization and (a) political satisfaction and (b) perceived quality of democracy?

How Political Polarization Shapes the Democratic Outcomes of Social Media Use

As the network media logic emphasizes the sharing of information among networks of like-minded others, we can expect symmetry between a country’s political structure and its social media space. In a cross-national study of 16 democracies, Urman (Citation2019) showed that the structure of polarization among social media users was aligned to a large extent with the degree of polarization among political parties in a country. At one end of the spectrum, Denmark represented a “perfectly integrated political Twittersphere,” as the accounts of all political parties in the country shared overlapping audiences; at the other end, the United States and South Korea represented “perfectly polarized” political social media spaces, as there were no overlapping audiences among the political parties. Country-level polarization can thus shape the structure and networks of the social media space, which can have direct implications for the type and valence of the political information shared among political actors and like-minded citizens.

In highly polarized countries, issue differences and hostility among partisans are amplified in the social media space because political elites, such as politicians, pundits, and partisan media, are motivated to disseminate content promoting in-group favoritism and out-group derision (Settle, Citation2018). For example, studies have shown that whereas politicians post more positive tweets about their own party than negative tweets of the opposing party (Yu et al., Citation2023), users tend to share negative and divisive content toward political out-groups because it has a greater chance of “going viral” (Rathje et al., Citation2021). In both cases, the heightened discursive emphasis on intergroup competition and threat can further increase the salience of a citizen’s political identity, which is a core psychological driver of democratic engagement (Huddy et al., Citation2015). Therefore, in highly polarized countries, social media can not only reduce the cost for individuals to gain information about politics but can also mobilize them to support their candidate or party based on information disseminated by like-minded political elites and citizens. Conversely, in countries that are less polarized, the valence and tone of social media communications are likely to be less hostile. These expectations lead us to propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

The relationships between social media and participation/voting are stronger with higher levels of (a) issue polarization and (b) affective polarization than with lower levels.

The role of political polarization in the social media and satisfaction with democracy relationship is more nuanced. In high-polarization countries, political cleavages are made more salient on social media, which can reduce social trust and cohesion among citizens (Lee, Citation2022). This should lower citizens’ satisfaction with democracy. However, the relationship might also be positive at lower levels of polarization. In a cross-national analysis of elections in 50 countries, Ridge (Citation2021) found that citizens who perceived their political system to include a broad range of political parties representing different positions were more satisfied with democracy; as she noted, “voters want choices, which requires difference, and they want those choices to cover the median ideological position, not just the extrema” (p. 428). In the case of Denmark’s “perfectly integrated” social media political structure, for example, users are connected to political parties that represent different political positions, which can give them the perception that there is representation and choice in their country’s politics. Conversely, in “perfectly polarized” social media spaces, users are connected only to their own parties, which can lead to perceptions that there is a lack of choice or diversity of perspectives on important political and social issues that affect their lives. We thus propose our final hypothesis:

H3:

The relationships between social media and political satisfaction/perceived quality of democracy diverge at different levels of (a) issue polarization and (b) affective polarization. At lower levels of political polarization, the relationships are positive; at higher levels, the relationships are negative.

Finally, by defining and examining the roles of issue and affective polarization separately, this study can provide a more nuanced analysis of different forms of political polarization. This leads to the final research question:

RQ4:

To what extent are the findings raised in addressing the previous hypotheses and research questions similar or different across the two types of political polarization?

Methodology

Sample

Data for the study was obtained and combined from two sources. For country-level measures of polarization we drew from the Varieties of Democracy (VDEM) dataset Version 12 (Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, et al., Citation2021). VDEM is a cross-national project that measures different facets of democracy over time and the dataset comprises various political and civil indicators of countries around the world that were coded by at least five country experts for each country indicator. For individual-level measures we drew data from the World Values Survey 7 (WVS-7) dataset Version 5 (Haerpfer et al., Citation2022), which comprises various indicators of citizen attitudes, values, beliefs, and political behaviors across 64 countries. Each country sample in the WVS-7 is representative of the population (i.e., aged 18 and above and living in private households) and was administered face-to-face to respondents in their native languages from early 2017 to mid-2020. Because citizens were asked about their perceptions of democracy and frequency of voting in national elections the final combined sample (i.e., countries included in both VDEM and WVS-7 datasets) were filtered to include only “full” and “flawed” democracies following the typology of political regime types in the Democracy Index produced by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). Accordingly, a “full democracy” is generally characterized by high political freedoms and civil liberties along with diverse and independent media and judiciary. A “flawed democracy” is characterized by having free and fair elections, but with significant weaknesses in other aspects (e.g., infringements on media freedom, problems in government, etc.) The final data comprised 43,225 respondents from 27 countries that included Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Mongolia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Peru, Philippines, Romania, Serbia, Singapore, Slovakia, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, United Kingdom, United States, and Uruguay. Supplementary Materials: Appendix B further elaborates on the V-Dem methodology and how the V-Dem-based data compares with other cross-national datasets.

Country-Level Measures

In this study, we adopted the more holistic measures of country-level political polarization that were applied in previous research (e.g., Humprecht et al., Citation2020; Somer et al., Citation2021). Issue polarization is broadly defined as differences in opinions and views among society on key political issues. Affective polarization is the extent to which partisans from opposing camps interact with each other in a friendly or hostile manner. Supplementary Materials: Appendix B provides a more thorough discussion on the measurement of political polarization.

Affective Polarization

Each country was rated with a score between 0 to 4 based on the question “Is society polarized into antagonistic, political camps?” The question is contextualized by the following description:

Here we refer to the extent to which political differences affect social relationships beyond political discussions. Societies are highly polarized if supporters of opposing political camps are reluctant to engage in friendly interactions, for example, in family functions, civic associations, their free time activities and workplaces. (Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Marquardt, et al., Citation2021, p. 224)

The answers ranged from 0 = “Not at all. Supporters of opposing political camps generally interact in a friendly manner” (i.e., New Zealand), to 4 = “Yes, to a large extent. Supporters of opposing political camps generally interact in a hostile manner” (e.g., Brazil, United States).

Issue Polarization

Each country was rated with a score between 0 to 4 based on the question: “How would you characterize the differences of opinions on major political issues in this society?” The question is contextualized by the following description:

While plurality of views exists in all societies, we are interested in knowing the extent to which these differences in opinions result in major clashes of views and polarization or, alternatively, whether there is general agreement on the general direction this society should develop. (Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Marquardt, et al., Citation2021, p. 329)

The answers ranged from 0 = “Serious polarization. There are serious differences in opinions in society on almost all key political issues, which result in major clashes of views.” to 4 = “No polarization. There are differences in opinions but there is a general agreement on the direction for key political issues.” As the original scale had lower values representing higher polarization, we reversed the scale to represent higher polarization. They ranged from “0” for Uruguay to “4” for Chile and South Korea.

Individual-Level Measures

Political Engagement and Attitudes

Political Participation

Respondents were asked whether they had engaged in the following forms of “political action and social activism”: (1) signing a petition, (2) donating to a group or campaign, (3) contacting a government official, (4) encouraging others to take action about political issues, and (5) encouraging others to vote. Affirmative answers were combined to create an index of political participation (from M = 0.42 in Peru to M = 2.68 in Germany).

Voting in Elections

Respondents were asked how frequently they voted in national level elections. The answers included 1 = “Never,” 2 = “Usually,” and 3 = “Always” (from M = 2.22 in Czech Republic to M = 2.90 in Uruguay).

Political System Satisfaction

Respondents were asked “How satisfied are you with how the political system is functioning in your country these days?” The answers ranged from 1 = “Not satisfied at all” to 10 = “Completely satisfied” (from M = 2.59 in Brazil to M = 6.78 in South Korea).

Perceived Quality of Democracy

Respondents were asked “How democratically is this country being governed today?” The answers ranged from 1 = “Not at all democratic” to 10 = “Completely democratic” (from M = 3.70 in Brazil to M = 7.58 in Germany).

Social Media Use and Controls

Social Media Use for Political Information

Respondents indicated their frequency of using “Internet and social media tools like Facebook, Twitter etc.,” to search for information about politics and political events. Answers were coded as 1 (“Have done”) and 0 (“Might do/Would never do”). Citizens in Romania answered affirmatively the least (11%) and those in Germany the most (66%). While this measure did not capture the intensity of usage, it should be noted that in 19 of the 27 countries in the sample, 70% or more of respondents do not use social media for political information at all. Therefore, even if continuous measures were available from the dataset, they could only be used to analyze a relatively small subset of respondents who may have different characteristics as the general population. Therefore, the binary distinction is still important and suitable for the purposes of this study.

Controls

A battery of country and individual level controls was included in the study. Country-level variables from various sources included population (Cyprus = 1.2 million to United States = 331.4 million); gross domestic product (Mongolia = US$13.3 billion to United States = US$20.9 trillion); human development index (Philippines = .72 to Germany = .95), electoral democracy index (Thailand = 6.0 to New Zealand = 9.4), number of political parties (United States = 2 to various = 10), press freedom (Singapore = 45 to Netherlands = 90) and Internet penetration (Philippines = 53% to South Korea = 98%). Supplementary Materials: Appendix C further summarizes the definitions and sources of these variables. Individual-level variables from the WVS included traditional media use, which was a composite measure combined from measures of newspaper, TV, and radio use (1 = “never” to 5 = “daily”); political interest (1 = “not at all interested” and 4 = “very interested”); frequency of political talk with friends (1 = “never” and 3 = “frequently); and); and ideology strength, which was a folded measure based on respondents’ left/right ideology (1 = “left” to 10 = “right”), which was then recoded so that 1 = weak left/right to 5 = very strong left/right. Demographics included age, gender, education (0 = “No education” and 8 = “Doctoral”), and household income (1 = “Lowest group” and 10 = “Highest group”).

Results

Analytic Approach

As individual respondent data is nested within countries the assumption of independent observations required for regression analysis is violated, which can result in smaller standard errors that lead to Type I error. Therefore, we adopted multilevel modeling to conduct the analyses. As political participation represented count data (i.e., occurrences of a behavior) we used quasi-Poisson regression to model the relationships of political polarization as it is appropriate for analyzing over-dispersed count variables whose variances are higher than their mean (Coxe et al., Citation2009). Linear regression models were applied to the other three continuous dependent variables (i.e., vote in elections, political satisfaction, and perceived quality of democracy) in this study. Taking into consideration the two types of dependent variable data, we used generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) analysis via the glmmTMB R package (Brooks et al., Citation2017).

Predicting Democratic Engagement and Satisfaction with Democracy

The intraclass correlation (ICC) in the intercept-only models showed that country (N = 27) explained 27%, 9%, 15%, and 14% of the variance respectively for political participation, voting in elections, political satisfaction, and perceived quality of democracy. This indicated that democratic engagement and satisfaction with democracy varied across countries and mixed-model analyses were appropriate. All individual and country-level variables were then entered as fixed effects. Standardized coefficients were reported to facilitate comparison of effect sizes among the variables as summarized in below. H1 proposed that social media use was positively related to (a) political participation and (b) voting. Both were confirmed by Models 1 (β =.30, p < .001) and 2 (β = .06, p < .001) so the hypothesis was accepted. Regarding its relationship with satisfaction with democracy (RQ1), social media was negatively related to political satisfaction (RQ1a: β = −.11, p < .001) and perceived quality of democracy (RQ1b: β = −.04, p < .01). RQ2 and RQ3 respectively focused on the relationship between issue/affective polarization and the four democratic outcomes. Issue polarization was negatively related to political participation (RQ2a: β = −.22, p < .05), but not voting (RQ2b). Neither form of polarization predicted political satisfaction (RQ3a) or perceived quality of democracy (RQ3b).

Table 1. Multilevel models predicting democratic engagement and attitudes.

Cross-Level Interactions of Social Media and Polarization on Democratic Outcomes

Models 5 to 8 in represented the main models with cross-level interactions added to examine the individual-level relationships between social media and democratic outcomes at different levels of country-level issue and affective polarization. H2 proposed that the relationship between social media and participation/voting will be stronger under higher levels of (a) issue polarization and (b) affective polarization compared to lower levels.

Table 2. Cross-level interactions predicting democratic engagement and attitudes.

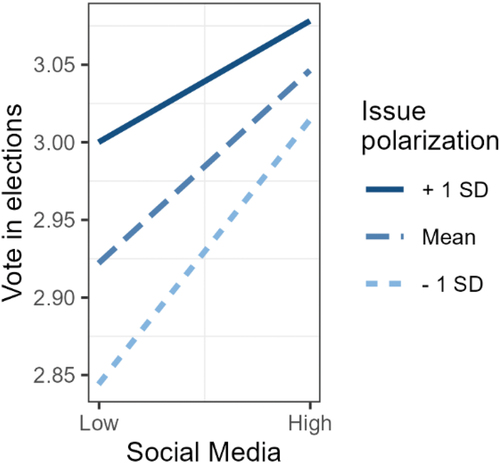

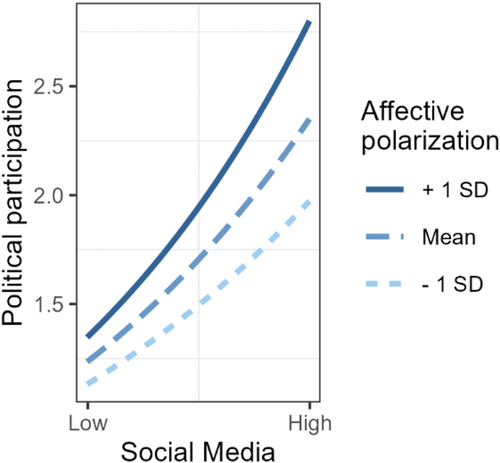

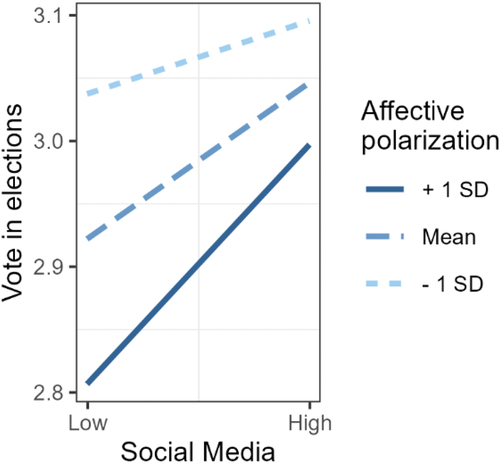

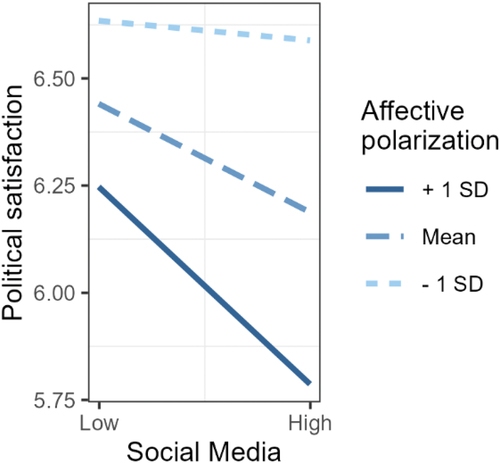

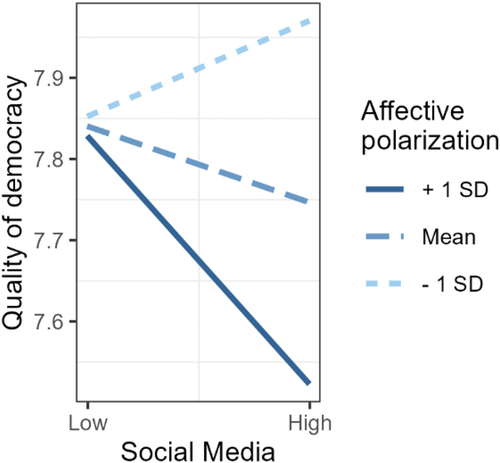

The interaction between social media and issue polarization was significant only for voting in elections (β = −.02, p < .001) and it was in the opposite direction as hypothesized (). H2a was not supported. The interactions between social media and affective polarization were significant for political participation (β = .04, p < .001) and voting in elections (β = .03, p < .001). As shown in , while the relationships between social media use and democratic engagement were positive overall, they were stronger under higher levels of affective polarization compared to lower levels. H2b was supported. H3 proposed that the relationships between social media and political satisfaction/perceived quality of democracy would diverge at different levels of (a) issue polarization and (b) affective polarization. The social media and issue polarization interaction was not significant for either outcome. H3a was not supported. However, the social media and affective polarization interactions were significant for both political satisfaction and the perceived quality of democracy. showed evidence of divergence. For political satisfaction (), the relationship with social media was relatively unchanged at low levels of affective polarization, but it became progressively negative at higher levels of affective polarization. For perceived quality of democracy (), the relationship with social media was positive at low levels of affective polarization, but negative at high levels of affective polarization. H3b was only partially supported because the social media and political satisfaction relationship was relatively unchanged at low levels of affective polarization rather than positive as proposed by H3b.

Figure 1. Cross-level interactions of issue polarization and social media on voting.

Figure 2. Cross-level interaction of affective polarization and social media on participation.

Figure 3. Cross-level interaction of affective polarization and social media on voting.

Figure 4. Cross-level interaction of affective polarization and social media on political satisfaction.

Figure 5. Cross-level interaction of affective polarization and social media on perceived quality of democracy.

The overall findings showed there were differences on the moderating roles of country-level issue and affective polarization on the relationship between social media use and the four democratic outcomes measured in this study (RQ4). Notably, affective polarization had more of a significant contingent role than issue polarization. Implications are discussed next.

Discussion

The relationship between social media and citizens’ participation in politics has been extensively examined by researchers, but not all studies have supported the notion that social media use leads to greater democratic engagement. There have also been mixed findings on the influence of social media on citizens’ satisfaction with democracy. This study seeks to bring more clarity to the literature by focusing on the contingent roles of issue and affective polarization. Our findings point to affective polarization as an important moderator that elucidates “cross-national patterns” of the role of social media in democratic outcomes (Boulianne, Citation2020).

Consistent with the general findings of previous meta-analyses (e.g., Boulianne, Citation2019; Skoric et al., Citation2016), using social media for political information was positively related to political participation and voting. To this we add the further finding that it was also negatively related to political satisfaction and perceived quality of democracy. These findings can be understood from the perspective of the network media logic, which emphasizes the role of social connections among political actors and like-minded citizens. Through these connections, users can not only receive information about politics but also calls to action, such as politicians encouraging their followers via tweets to vote for them in upcoming elections. As to the negative relationship, it is possible that there is disproportionate dissemination of negative and uncivil political content and discourse on social media platforms that does not conform with democratic norms (Ceron & Memoli, Citation2015). Such negative content can be amplified further in countries with higher affective polarization as partisan tensions and hostilities at the society level are reflected in the social media space (Urman, Citation2019). Conversely, when affective polarization is low there could be more heterogeneous and less negative political content, such that the social media use relationship does not change for political satisfaction and even becomes positive for perceived quality of democracy. Thus, in countries with relatively low affective polarization, such as Germany, Japan, New Zealand, and Taiwan, social media use for political information is conducive to promoting citizens’ positive attitudes toward the overall quality of democracy in their countries. Conversely, in countries with high affective polarization, such as the United States and Thailand, the social media space can be used to express and share intolerance toward other social groups and civil society (Rossini, Citation2022) and to endorse non-democratic behaviors (Somer et al., Citation2021). This may lead to negative attitudes toward the political system and democracy, which could have longer-term implications for democratic erosion and backsliding (Placek, Citation2023).

At the same time, we found that affective polarization further amplified the positive relationship between social media use and democratic engagement, which is consistent with the “benevolent consequences” or “blessing in disguise” argument by Harteveld and Wagner (Citation2022) that higher affective polarization can be desirable to increase citizen engagement in politics. Indeed, the distinct two-way dynamics of country-level affective polarization uncovered in this study brings to mind the theoretical tensions explicated two decades ago between participatory and deliberative democracy as the same “passion” and “enthusiasm” that citizens may hold for political participation can also harm their social relationships (Mutz, Citation2006). That is, the same emotional underpinnings that motivate participation may also undermine interpersonal trust and thus lead to a breakdown in social cohesion and lower perceived quality of democracy.

Another important finding is that the contingent roles of issue and affective polarization were different, even though they were highly correlated among the 27 countries (r = .68). This validates previous arguments that “differentiation matters” when examining the dynamics of different types of political polarization and social media (Kubin & von Sikorski, Citation2021). Compared to affective polarization, the dynamics of social media use on satisfaction with democracy were not influenced by issue polarization, possibly because divides on issue or policy are less salient in the social media space than are divides based on social groups. Issue polarization amplified the relationship between social media use and voting, although the magnitude was greater at lower levels of issue polarization. A possible explanation is that elections are generally more competitive when there is a greater diversity of parties and candidates representing different policy and issue positions, and it is reasonable to assume that social media plays a lesser role in citizens’ motivations to vote when the overall political environment is already very competitive.

Taken together, the findings suggest that certain countries, especially those that score highly in affective polarization (e.g., Argentina, Brazil, Malaysia, Thailand, and the United States), could be more prone to democratic erosion than others from citizens’ use of social media. Comparatively, this might be less of a concern in countries with high issue polarization but low affective polarization, such as Taiwan, Serbia, and the Netherlands, given that the findings suggest that affective polarization rather than issue polarization at the country level is more intertwined with the negative aspects of the social media space that reduce satisfaction with democracy.

Limitations and Future Studies

Several limitations of the study and avenues for further exploration should be noted. Foremost is that the polarization findings are bounded by our conceptual underpinnings of the concept. Polarization, and especially affective polarization, has been measured in diverse ways in the literature (Druckman & Levendusky, Citation2019). For example, the concept in this study emphasizes intergroup relations among partisan publics rather than perceived differences in political parties, and the findings should be interpreted with this in mind. Scholars examining the antecedents and consequences of political polarization are advised to present up front their definition(s) of polarization, given this study’s finding that different forms of political polarization influence democratic outcomes in different ways. Moreover, this study positions political polarization as a contextual country-level variable in finding that it shaped the relationship between social media use and democratic outcomes. There is a body of political communication scholarship that has focused primarily on how individuals’ use of social media can influence their levels of perceived political polarization (see the review by Kubin & von Sikorski, Citation2021), although a recent study has also theorized and shown that perceived political polarization leads to greater social media use (Nordbrandt, Citation2021). For greater clarity on the dynamic relationships of social media and political polarization at different levels of analysis, future cross-national studies can adopt longitudinal designs to consider individual differences in social media use and perceived polarization on democratic outcomes as well as the direction of causation within a larger polarization context at the country level.

Another point related to the measure of social media use is that this study focuses only on informational uses of social media, when expressive uses are also prominent on social media and have been shown to engender democratic outcomes (Boulianne, Citation2019). The extent to which political polarization amplifies or suppresses expression on social media is another potential avenue of exploration. Future research can also consider the polarization dynamics of different social media platforms as each have their own specific affordances for political expression, such as the relatively public news feed in Facebook (Settle, Citation2018) and the more private and closed spaces of messaging apps such as WhatsApp (Kligler-Vilenchik et al., Citation2020), which may influence democratic outcomes in different ways. This is especially relevant to our measure of using social media to search for information about politics and political events, which could take different forms depending on the platform. Moreover, as this study was based on secondary data it was not possible to parse out the specific informational uses of social media for political information; for example, whether the information came from a professional media outlet or a friend. This is something that future cross-national comparisons can seek to address.

Our findings also do not speak to the normative aspects of polarization and the prevailing assumption among scholars and commentators that polarization is “bad” for democracy, because the social media platforms that induce intergroup tensions and antagonism are also often the same platforms on which marginalized groups can make their voices heard and mobilize to “assert their right to political and economic equality” (Kreiss & McGregor, Citation2023, p. 12). As pointed out by some critics, the normative ideals of consensus and social cohesion in a deliberative democracy by and large ignore the role of power (e.g., Mouffe, Citation1999). In fact, for some of the “flawed” democracies in our sample, high levels of political polarization and its associated outcomes could actually be necessary to prevent further democratic erosion, such as by the removal of populist political leaders who pose an exponentially larger threat to the democratic system in their countries.

Despite these limitations, this study is one of the first to elucidate how different types of political polarization interact with social media use for political information to influence individuals’ democratic engagement and satisfaction with democracy. Contrary to what is implied by the literature, these dynamics and their potential to engender positive and negative democratic outcomes are not limited to the United States and Europe, where much of the polarization literature resides, but are also at play in other democracies around the world.

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data and Open Materials through Open Practices Disclosure. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.48668/G23XXX

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Open Data and Open Materials through Open Practices Disclosure. The data and materials are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.48668/G23XXX

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (60.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The main data that support the findings of this study are openly available from Worlds Value Survey (Wave 7, ver. 5) at https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV7.jsp and V-Dem (ver. 12) at https://www.v-dem.net/data/dataset-archive. Other data sources for the study are detailed in the Supplementary Materials: Appendix C.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2024.2325423

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael Chan

Michael Chan (PhD, CUHK) is an Associate Professor at the School of Journalism and Communication, Chinese University of Hong Kong. His research focuses on individuals’ uses of digital technologies and subsequent political, social, and psychological outcomes.

Jingjing Yi

Jingjing Yi (MA, Syracuse University) is a PhD student at the School of Journalism & Communication, Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her research areas include social media, media psychology, and game studies.

References

- Altheide, D. L. (2016). Media logic. The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118541555.wbiepc088

- Boulianne, S. (2019). Revolution in the making? Social media effects across the globe. Information, Communication & Society, 22(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2017.1353641

- Boulianne, S. (2020). Twenty years of digital media effects on civic and political participation. Communication Research, 47(7), 947–966. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650218808186

- Brady, H. E., Verba, S., & Schlozman, K. L. (1995). Beyond SES: A resource model of political participation. American Political Science Review, 89(2), 271–294. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082425

- Broockman, D. E., Kalla, J. L., & Westwood, S. J. (2022). Does affective polarization undermine democratic norms or accountability? Maybe not. American Journal of Political Science, 67(3), 808–828. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12719

- Brooks, M. E., Kristensen, K., Benthem, K. J. V., Magnusson, A., Berg, C. W., Nielsen, A., Skaug, H.J., Machler, M., & Bolker, B. M. (2017). glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. The R Journal, 9(2), 378. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2017-066

- Ceron, A., & Memoli, V. (2015). Flames and debates: Do social media affect satisfaction with democracy? Social Indicators Research, 126(1), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0893-x

- Ceron, A., & Memoli, V. (2015). Flames and debates: Do social media affect satisfaction with democracy?. Social Indicators Research, 126(1), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0893-x

- Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., & Ziblatt, D. (2021). V-Dem Codebook v11.1: Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3802627

- Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Marquardt, K. L., & Wilson, S. (2021). V-Dem methodology v11.1: Varieties of democracy (V-Dem) project. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3802748

- Coxe, S., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2009). The analysis of count data: A gentle introduction to poisson regression and its alternatives. Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634175

- Delli_carpini, M. X. (2004). Mediating democratic engagement: The impact of communications on citizens’ involvement in political and civic life. In L. L. Kaid (Ed.), Handbook of political communication research (pp. 395–434). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Druckman, J. N., & Levendusky, M. S. (2019). What do we measure when we measure affective polarization? Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(1), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz003

- Fiorina, M. P., & Abrams, S. J. (2008). Political polarization in the American public. Annual Review of Political Science, 11(1), 563–588. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.053106.153836

- Gidron, N., Adams, J., & Horne, W. (2020). American affective polarization in comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press.

- Gulyas, A. (2013). The influence of professional variables on journalists’ uses and views of social media. Digital Journalism, 1(2), 270–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2012.744559

- Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., Puranen, B. … Puranen, B. (Eds.). (2022). World values survey: Round seven – country-pooled datafile version 5.0. JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat. https://doi.org/10.14281/18241.20

- Harteveld, E., & Wagner, M. (2022). Does affective polarisation increase turnout? Evidence from Germany, the Netherlands and Spain. West European Politics, 46(4), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2087395

- Huddy, L., Mason, L., & Aarøe, L. (2015). Expressive partisanship: Campaign involvement, political emotion, and partisan identity. American Political Science Review, 109(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000604

- Humprecht, E., Esser, F., & Van Aelst, P. (2020). Resilience to online disinformation: A framework for cross-national comparative research. The International Journal of Press/politics, 25(3), 493–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219900126

- Iyengar, S., & Krupenkin, M. (2018). The strengthening of partisan affect. Political Psychology, 39(S1), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12487

- Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

- Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs038

- Kligler-Vilenchik, N., Baden, C., & Yarchi, M. (2020). Interpretative polarization across platforms: How political disagreement develops over time on Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. Social Media + Society, 6(3), 6(3. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120944393

- Klinger, U., & Svensson, J. (2015). The emergence of network media logic in political communication: A theoretical approach. New Media & Society, 17(8), 1241–1257. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814522952

- Kreiss, D., & McGregor, S. C. (2023). A review and provocation: On polarization and platforms. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231161880

- Kubin, E., & von Sikorski, C. (2021). The role of (social) media in political polarization: A systematic review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 45(3), 188–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2021.1976070

- Kuehn, K. M., & Salter, L. A. (2020). Assessing digital threats to democracy, and workable solutions: A review of the recent literature. International Journal of Communication, 14, 2589–2610.

- Lee, A. H.-Y. (2022). Social trust in polarized times: How perceptions of political polarization affect Americans’ trust in each other. Political Behavior, 44(3), 1533–1554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09787-1

- Levendusky, M. S. (2010). Clearer cues, more consistent voters: A benefit of elite polarization. Political Behavior, 32(1), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-009-9094-0

- Linde, J., & Ekman, J. (2003). Satisfaction with democracy: A note on a frequently used indicator in comparative politics. European Journal of Political Research, 42(3), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00089

- Mason, L. (2013). The rise of uncivil agreement: Issue versus behavioral polarization in the American electorate. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(1), 140–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764212463363

- Mason, L. (2015). “I disrespectfully agree”: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12089

- Mason, L. (2018). Ideologues without issues: The polarizing consequences of ideological identities. Public Opinion Quarterly, 82(S1), 866–887. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfy005

- Mayne, Q., & Hakhverdian, A. (2016). Ideological congruence and citizen satisfaction: Evidence from 25 advanced democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 50(6), 822–849. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414016639708

- McCoy, J., Rahman, T., & Somer, M. (2018). Polarization and the global crisis of democracy: Common patterns, dynamics, and pernicious consequences for democratic polities. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(1), 16–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218759576

- McCoy, J., & Somer, M. (2018). Toward a theory of pernicious polarization and how it harms democracies: Comparative evidence and possible remedies. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 681(1), 234–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716218818782

- McGregor, S. C. (2017). Personalization, social media, and voting: Effects of candidate self-personalization on vote intention. New Media & Society, 20(3), 1139–1160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816686103

- McLeod, J. M., Scheufele, D. A., & Moy, P. (1999). Community, communication, and participation: The role of mass media and interpersonal discussion in local political participation. Political Communication, 16(3), 315–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/105846099198659

- Merten, L. (2020). Block, hide or follow—personal news curation practices on social media. Digital Journalism, 9(8), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1829978

- Mouffe, C. (1999). Deliberative democracy or agonistic pluralism? Social Research, 66(3), 745–758.

- Mutz, D. C. (2006). Hearing the other side: Deliberative versus participatory democracy. Cambridge University Press.

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Eddy, K., & Nielsen, R. K. (2022). Digital News Report 2022. http://www.digitalnewsreport.org/

- Nordbrandt, M. (2021). Affective polarization in the digital age: Testing the direction of the relationship between social media and users’ feelings for out-group parties. New Media & Society, 25(12), 3392–3411. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211044393

- Norris, P. (2000). A virtuous circle: Political communications in postindustrial societies. Cambridge University Press.

- Orhan, Y. E. (2022). The relationship between affective polarization and democratic backsliding: Comparative evidence. Democratization, 29(4), 714–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.2008912

- Placek, M. (2023). Social media, quality of democracy, and citizen satisfaction with democracy in central and eastern Europe. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 21(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2023.2220319

- Rathje, S., Van Bavel, J. J., & van der Linden, S. (2021). Out-group animosity drives engagement on social media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(26), 118(26. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2024292118

- Ridge, H. M. (2021). Just like the others: Party differences, perception, and satisfaction with democracy. Party Politics, 28(3), 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820985193

- Rossini, P. (2022). Beyond incivility: Understanding patterns of uncivil and intolerant discourse in online political talk. Communication Research, 49(3), 399–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220921314

- Settle, J. E. (2018). Frenemies: How social media polarizes America. Cambridge University Press.

- Singh, S. P., & Mayne, Q. (2023). Satisfaction with democracy: A review of a major public opinion indicator. Public Opinion Quarterly, 87(1), 187–218. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfad003

- Skoric, M. M., Zhu, Q., Goh, D., & Pang, N. (2016). Social media and citizen engagement: A meta-analytic review. New Media & Society, 18(9), 1817–1839. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815616221

- Somer, M., McCoy, J. L., & Luke, R. E. (2021). Pernicious polarization, autocratization and opposition strategies. Democratization, 28(5), 929–948. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1865316

- Statista. (2023). Global social network penetration rate as of January 2023, by region. Retrieved June 25, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/269615/social-network-penetration-by-region/

- Svolik, M. W. (2019). Polarization versus democracy. Journal of Democracy, 30(3), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0039

- Urman, A. (2019). Context matters: Political polarization on twitter from a comparative perspective. Media, Culture & Society, 42(6), 857–879. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719876541

- Vissers, S., & Stolle, D. (2014). Spill-over effects between Facebook and on/offline political participation? Evidence from a two-wave panel study. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 11(3), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2014.888383

- Wagner, M. (2021). Affective polarization in multiparty systems. Electoral Studies, 69, 102199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102199

- West, E. A., & Iyengar, S. (2020). Partisanship as a social identity: Implications for polarization. Political Behavior, 44(2), 807–838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09637-y

- Wojcieszak, M., Casas, A., Yu, X., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. A. (2022). Most users do not follow political elites on Twitter; those who do show overwhelming preferences for ideological congruity. Science Advances, 8(39), eabn9418. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abn9418

- Wojcieszak, M., & Warner, B. R. (2020). Can interparty contact reduce affective polarization? a systematic test of different forms of intergroup contact. Political Communication, 37(6), 789–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1760406

- Yu, X., Wojcieszak, M., & Casas, A. (2023). Partisanship on Social Media: In-Party Love Among American Politicians, greater engagement with out-Party hate Among ordinary users. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09850-x