ABSTRACT

Drawing on transcripts from the television network Channel One, a popular news source in Russia, this article addresses the question: “How was Vladimir Putin covered by state-controlled media while the regime became increasingly centralized?” The literature on the subject is scarce and inconclusive. Dictators create different images of themselves, and the portrayals of present-day spin dictators — those who primarily rely on the power of propaganda to persuade rather than dominate — are understudied. While some analysts point to Putin’s omnipresence in mass media, others uncover the lack of media personalization and relatively neutral coverage. Using 385,981 news transcripts from 2000–2022 and relying on techniques from natural language processing, I examine how a present-day autocrat attempts to optimize the intensity of state-controlled propaganda. I uncover three main tendencies. First, during all the years in power, the ruler has been more frequently referred to through positive stories. Second, there is only partial evidence that the relative references to Putin on Channel One have significantly increased over time. Third, during all his years in power, Putin has been more frequently mentioned in domestic news rather than in stories about foreign affairs. However, I also demonstrate that the share of news about foreign affairs and events abroad that mentions the ruler has been increasing every year since 2013. By focusing on the supply side of propaganda, this article contributes to the literature on autocratic resilience and spin dictators.

KEYWORDS:

Political scientists agree that many present-day dictators enjoy genuine popularity at home and point to state-controlled mass media as a major tool to generate public support (Guriev & Treisman, Citation2022). They also acknowledge that there is no single and simple concept such as autocratic propaganda and that mass-media manipulation strategies vary across non-free regimes (Carter & Carter, Citation2023). These arguments highlight the need to examine mass-media management in each autocracy separately.

The literature further acknowledges that spin dictatorship is becoming a popular form of survival for non-free regimes (Guriev & Treisman, Citation2022). Spin dictatorsFootnote1 use mass media for genuine persuasion and shaping citizens’ beliefs about the world. This strategy is contrasted with fear propagandaFootnote2 employed by old-school tyrants. In the fear-based model, by compelling citizens to consume content acknowledged by all as false, a ruler makes hisFootnote3 capacity for repression widely recognized (Svolik, Citation2012, p. 81).

The scholars suggest that propaganda for persuasion is employed to some extent by almost all present-day non-free regimes.Footnote4 A shift to persuasive propaganda has been observed even in China (Wang, Citation2023), despite its previous characterization as a regime heavily reliant on fear propaganda (Huang, Citation2015). However, the exact strategies used by spin dictators have only recently started to attract attention from scholars. This article helps fill this gap by examining the mass-media coverage of a spin dictator himself.

Studying the strategies of dictators’ image-making is important. The image of the rulers projected in the media helps them remain in power, given their ability to track public opinion and the context, including ongoing developments in economics, politics, and media consumption. Because of advances in technology, present-day dictators have freedom in shaping their public image (Chang, Citation2024). A better grasp of the mass-media strategies an autocrat might use could help uncover not only the mechanisms of autocratic regime’s resilience but also its strengths and weaknesses.

Autocrats’ approaches to their image-making in mass media vary. Mobutu, Papa Doc, and Ceaușescu compulsively promoted their own personae (Ezrow & Frantz, Citation2011, pp. 229–232; Dikötter, Citation2019, p. 165). Mubarak was known for having a low-key and business-like style that did not generate strong emotions to oust him (Ezrow & Frantz, Citation2011, p. 271). Hitler used an image of a non-person (Kershaw, Citation2013) and the nation’s friend and protector, while threatening his audience with dire consequences if a certain course of action was not followed (Pratkanis & Aronson, Citation2001, pp. 161, 255). Presently, OrbanFootnote5 is portrayed by his media as a fighter against a variety of enemies, a symbol of the nation, and a relatable politician (Sonnevend & Kövesdi, Citation2023), while China’s leaders – under certain circumstances – encourage criticism of themselves (Chang, Citation2024). This article aims to contribute to the literature of mass-media coverage of dictators by examining the case of Putin’s Russia.

Before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Putin’s Russia was as a typical case of a spin dictatorship. Political scientists agree that Vladimir Putin has been enjoying unwavering popularity during more than twenty years in office, with his approval ratings rarely dipping below 70% (Frye, Citation2022, pp. 52–53). The literature further acknowledges that mass media has served as an important tool that has helped him to stay in power (Sharafutdinova, Citation2020, pp. 133–166) and that state-controlled television has been the most popular source of news consumption in Russia (Frye, Citation2022, p. 136). However, the exact news-management strategies employed by national television remain understudied. While scholars attended to television narratives about the state of the economy (Rozenas & Stukal, Citation2019), ethnicity (Hutchings & Tolz, Citation2015), foreign protests (Lankina & Watanabe, Citation2017; Otlan et al., Citation2023), and the memory of the past (McGlynn, Citation2023), they have rarely focused on the media coverage of Russia’s dictator himself.

Only a handful of studies have touched upon the subject. Rozenas and Stukal (Citation2019) found that Putin is more likely to be referred to in the fragments of economic news with a positive sentiment. Carter and Carter (Citation2023, p. 270) documented that Putin is mentioned by newspaper Rossyiskaya Gazeta’s coverage of international affairs only occasionally (35% of all coverage), whereas in comparison, 75% of the content of the People’s Daily makes references to Xi Jinping or the Chinese Communist Party. Baturo and Elkink (Citation2021) detected no significant evidence of increasing mass-media focus on Putin in 2000–2018.

Indirect evidence about the media image of the ruler also remains inconclusive. Popular writing often describes him as a hidebound conservative and an orthodox nationalist, referring to his 2007 Munich Speech, which challenged American power in the world order. At the same time, events in the history of Putin’s rule that contradict the argument, such as Russia’s inquiries about joining NATO, are left somewhat unnoticed. Moreover, the nationalistic image of the dictator on the international arena does not necessarily imply that a similar reputation is promoted by domestic media. For instance, Greene and Robertson (Citation2019, pp. 65–66) argue that at least before the annexation of Crimea, Putin assiduously avoided presenting himself as an outright nationalist; Guriev and Treisman (Citation2022) suggest that many present-day dictators promote the image of competency, primarily aiming to be portrayed as effective managers and humble servants of the people. Yet, to the best of my knowledge, most claims regarding Putin’s mass-media image management, as well as the image of spin dictators in general, have not been tested using any systematic analysis, either qualitative or quantitative, with datasets from state-controlled news media. This article helps fill this gap.

I theorize that in a spin dictatorship, a state-aligned mass-media outlet has two interrelated goals. First, it seeks to signal to the public that the ruler is competent. Second, it aims not to lose its audience (and possibly attract new viewers) due to intense propaganda, censorship, or other information manipulation techniques. In other words, mass media aims to create an image that can potentially invoke genuine public support and approval, rather than demonstrate a capacity for repression, as is often seen in fear autocracies. To shed light on the image management of a spin dictator, I formulate and test three hypotheses related to the sentiment of stories mentioning the ruler, the frequency of the ruler’s appearance on national media, and the country-topics of episodes mentioning the ruler. While my findings contribute to the literature on spin dictators in general, my hypotheses are specifically formulated for the context of Putin’s Russia. This choice is primarily due to the unique characteristics of the regime, which include, but are not limited to, nearly complete national control over mass media, a predominantly monolingual population with limited access to information from abroad, the state’s prominent role on the international stage, its capacity to sustain long-term foreign conflicts, and the ruler’s ability to leverage increased economic prosperity in the past.

Drawing on 385,981 textual news reports from Channel One, one of the most popular television networks in Russia during the period, and applying techniques from natural language processing (NLP) to estimate the sentiment of every news episode and label the stories with the most likely country of origin of an event, I document that in every year from 2000 to the first two months of 2022, Putin has been more frequently mentioned in more positive news and in domestic stories rather than in reports about foreign affairs. I also find only partial evidence of increasing mass-media focus on the ruler while his autocracy was strengthening. Further analysis of domestic narratives does not reveal radical changes over time. The ruler has been predominantly mentioned in the stories about economics, business, social welfare, health services, and education, followed by cultural affairs, sporting events, ceremonies, and questions of national security.

On average, 16% of news about events in Russia and 7% of stories about foreign affairs and events abroad refer to the ruler, which amounts to 9% and 3% of total reports from Channel One, respectively. At the same time, I document a steady and significant increase – from 3% in 2012 to 18% in 2021 – in the share of news about foreign affairs and events originating abroad that mentioned the ruler.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

Full control over national media allows a dictator to craft any desired image of himself. Indeed, history provides even extreme examples of rulers claiming to possess wizardly and supernatural powers (Dikötter, Citation2019). However, an excessively positive, intense, or distorted in other ways image is unlikely to be an effective strategy for persuading the masses. Increased bias reduces the informational content of the news, thus lowering the trust in mass media and decreasing the likelihood that individuals who need that information to make decisions will consume it (Gehlbach & Sonin, Citation2014). Literature emphasizes a risk – return trade-off of propaganda concerning the citizen skepticism, action, and trust (Horz, Citation2021). Moreover, even in situations when the information disseminated by an autocratic regime is factual, intense government releases of such information may amplify citizen skepticism (Chang, Citation2021). Furthermore, not only may proactively creating favorable content backfire but the same holds true for the suppression of unfavorable information. The literature on censorship, another strategy at autocrat’s disposal, exemplifies how extreme media manipulation may cause mass disapproval of the regime (Gläßel & Paula, Citation2020).

As the sentiment, intensity of coverage, and topics are among the key measurable characteristics of communication and texts (Grimmer & Stewart, Citation2013), I formulate my hypotheses about mass-media coverage of a dictator from these three angles. When addressing the content of the stories, I pay special attention to the country-topics of news coverage not only for theoretical reasons discussed below, but also for practical purposes, as the existing NLP models enable accurate classification of stories in this manner.

Theoretical expectations about the tone of the coverage of present-day spin dictators are mixed. The literature on archetypical tyrants clearly predicts the sentiment to be positive. For instance, Ford (Citation1935) writes:

The dictator becomes the symbol of all that is good, the source from which all blessings flow. Is a new bridge dedicated? Credit Hitler or Mussolini or Stalin! Are the marshes reclaimed? It is Mussolini’s work! Do trains run on time? Are the streets clean, the parks well groomed … give thanks to the Party and its Leader. (p. 265)

On one hand, there are reasons to expect that spin dictators, akin to their predecessors, would portray themselves in a wholly positive light rather than in a neutral or even occasionally negative manner. Guriev and Treisman (Citation2022, p. 75) suggest that instead of the old threat – “Be obedient, or else!” – the message of a spin dictator is: “Look what a great job we’re doing!” Some descriptive examples align with this claim. Dobson (Citation2012, pp. 122–133) documents that Chávez, a typical spin dictator, only allowed the stories that depicted him in a positive light. Baser and Öztürk (Citation2017, p. 214) note that Erdoğan similarly censors all criticism in his address.

On the other hand, there are reasons to expect the portrayal of a spin dictator to be neutral (similar in tone to other stories) or even occasionally negative. First, and most importantly, as I discuss above, too-biased news can backfire, amplify public skepticism, and reduce mass-media consumption. Conversely, negative (or neutral) coverage of the ruler may signal openness and increase the perception of information transparency. This could translate into further credibility and demand for consuming state-controlled media for more information regarding policies and politics (Wang, Citation2023). Additionally, the literature does not find positive emotions to be a particularly effective tool to manufacture consent (Pratkanis & Aronson, Citation2001; Soroka & McAdams, Citation2015). Some descriptive examples also support this logic. Dobson (Citation2012, p. 220) shows that Mubarak, who was portrayed in a positive light on national media in the 1980s and 1990s, strategically started to allow criticism of himself from the 2000s onwards. When it comes to Russia, the scholarship also does not find many signs of positive coverage of Putin and notes that contrary to the classical personalist regimes, its media is far from demonstrating the ruler’s personal prestige in its extreme form (Baturo & Elkink, Citation2021). To address this puzzle, I formulate the following hypothesis:

H1 (Sentiment): Putin is mentioned more frequently in news episodes that convey a more positive sentiment compared to other stories.

The expectations about the personalization (the relative and absolute frequency of the references to the ruler) in state-controlled mass media are also mixed. The literature agrees that once a dictator takes control, he tries to maximize his power and personalize the regime, and these attempts do not stop when the regime is formed (Geddes et al., Citation2018). Therefore, it is somewhat reasonable to expect state-controlled media to pay more attention to the ruler while his autocracy is strengthening. However, again, extreme mass-media personalization may backfire. As Carter and Carter (Citation2023, p. 9) put it, “propaganda is only powerful when subtle.” Furthermore, empirical evidence on this question is scarce and far from conclusive. While some scholars mention Putin’s omnipresence in mass media, their arguments are often focused on his macho image (Sperling, Citation2016) and lack analysis. To the best of my knowledge, the only systematic attempt to study mass-media centralization on Putin has been conducted by Baturo and Elkink (Citation2021, pp. 139–160). Drawing on a collection of sources downloaded from Integrum archive,Footnote6 the authors detect no significant evidence of increasing media focus on Putin over time. Therefore, I formulate the following hypothesis:

H2 (Frequency): The mentions of Putin increase with each consecutive term in power.

Theoretical expectations about the country-topics of news reports are more precise but rarely tested empirically. The literature suggests that since citizens are generally uncertain about whether the ruler implements sound policies, autocrats may use propaganda to take credit for progress during favorable domestic circumstances such as, for instance, economic upturn (Dukalskis & Gerschewski, Citation2018), thereby earning the loyalty of their subjects without seriously undermining the credibility of state-aligned mass media. However, when domestic situation becomes less favorable, the task of misinforming the populace presents additional challenges as the audience can benchmark the information from the news against their immediate experience by observing their private incomes, safety, protests on the streets, and so on (Lipman et al., Citation2018). In these circumstances, mass-media may attempt to shift its attention away from domestic affairs and resort to the stories that address foreign news or the country’s role in the international area (Aytaç, Citation2021). The literature offers two distinct yet not mutually exclusive explanations for how this strategy may assist the ruler in garnering domestic support.

First, the stories that involve foreign news may be used as a simple distraction from domestic events as they are more difficult for an ordinary citizen to fact-check (Carter & Carter, Citation2023, p. 23). When the constraints on honest news management are weaker, image management can be more critical without undermining the reputation for credibility.

Second, foreign news in autocracies often reports on a threat emanating from abroad, which, according to the diversionary theory of war, may help enhance national cohesion and bolster domestic support for the leader (Oakes, Citation2012). Irrespective of the real or imagined nature of the threat, the message conveyed to the general population is: “A dangerous enemy is at our gates … we cannot afford to have dissent and disunity at home” (Moghaddam, Citation2013, pp. 67, 110). In this regard, Alrababa’h and Blaydes (Citation2021) show that prior to the 2011 Arab uprisings, Syria’s domestic newspapers concentrated on Israel as a threat. However, after 2011, the focus on Israel was replaced by the discussions about foreign plots against the Syrian state. Similarly, Moghaddam (Citation2013, pp. 67–70) describes how in the months preceding the actual overthrow of the Shah, Iran’s Khomeini repeatedly warned his domestic audience that the US was plotting to interfere in the country. The literature on the last decade of Putin’s regime also often observes that “Russia is presented [by national mass-media] as a besieged fortress, with Vladimir Putin as its savior on the ramparts” (Greene & Robertson, Citation2019, p. 207).

In summary, the theory suggests that image-making that is focusing on foreign rather than domestic affairs, might be an effective strategy for an autocrat aiming to distance himself from an unfavorable situation at home and enhance his public approval. However, imposing risk on the propaganda apparatus by radically shifting the news management strategies may prove costly, as excessively extreme propaganda may backfire. Therefore, I formulate the following hypothesis:

H3 (Country-topics): When the economy is down, Putin is mentioned more frequently is the news that relate to foreign relations and events..

News Management on National Television in Russia

Putin’s Russia is characterized by near-total state control over political information flows. Soon after his first election, the ruler began to assert power over mass media. By the end of Putin’s first presidential term, three most-popular TV networks – Channel One, Russia-1, and NTV – had come under Kremlin authority. As the decade neared its end, almost all national television was controlled by just three entities: the state, Gazprom-Media,Footnote7 and a series of companies owned by the members of Putin’s inner circle (Lipman et al., Citation2018).

The Presidential Administration, an executive office supporting the president’s activities, regulates news management on national television in Russia. It instructs TV managers about the main talking points to be covered in the news (Sharafutdinova, Citation2020, p. 137), assigns networks to Kremlin officials (kurators) responsible for steering national TV toward the regime’s priorities (Greene & Robertson, Citation2019, p. 41), and disseminates instructions (temniki) regarding the thematic agenda and key perspectives to be emphasized in the news (Sharafutdinova, Citation2020, p. 136). The instructions dictate which news should be highlighted and in what context, as well as which events should be disregarded.

Consequently, national networks are left with almost no freedom of choice in their news reporting. Importantly, the Kremlin closely monitors public opinion and, therefore, can test the effectiveness of its mass-media manipulations strategies (Rogov & Ananyev, Citation2018).

With 70% of the population monolingual and only 11% speaking English (Levada-Center, Citation2014), and independent media being consistently under pressure from the state (Paskhalis et al., Citation2022), state-controlled television has been the most popular news source during this period. While growing web access decreased the popularity of and trust in the old media, that decrease was far from rapid (Levada-Center, Citation2021), partially due to a successful state initiative to provide all households with access to national television networks free of charge. Even in 2019, between 64% and 85% of Russian citizens gained their knowledge about current affairs from watching TV (Sharafutdinova, Citation2020, p. 150).

Channel One, previously known as ORT, is a state-owned network marketed as the flagship channel of the All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company (VGTRK). It was one of the first TV channels to come under firm control and ownership by the state and is known not only for broadcasting but also for producing various forms of news, political, and entertainment content (Lipman et al., Citation2018). For most of Putin’s rule, the channel was the most-popular TV network in Russia. Even in 2019, almost half of the Russian population reported watching Channel One news regularly (Levada-Center, Citation2019b).

Since transcripts from two other top channels, Russia-1 and NTV, for the period between 2000 and 2022 were not available in open access, the corpus used in this article is limited to data from only one network, Channel One. This limitation, however, is unlikely to compromise the research design because news management on Russian TV adheres to standardized instructions from the Kremlin.

Data and Estimation Strategy

My analysis relies on a corpus comprising 385,981 transcripts of news reports transmitted on Channel One between December 311,999, the day when Putin became an acting President of Russia, and February 23, 2022, the day before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine (). The data was scraped from the media outlet’s website. The stories are all in Russian and, on average, are 235 (SD = 231) words long. Stories that mentioned Vladimir Putin were identified using keyword search.Footnote8

Figure 1. Corpus from Channel One.

The corpus comprises all news transmitted on Channel One, encompassing Novosti (“News”) and Vremya (“Times”) programs, and does not include entertainment shows. To verify transcripts’ accuracy, I randomly selected 39 episodes (0.01% of the data) from the website and cross-referenced the video content with the text. To ensure the accuracy of the website data representing Channel One’s broadcasts, I collected information about the 24-hour actual broadcast in Moscow and compared the programming with the data from the website. In both cases, no discrepancies were found.

My approach assumes that the relative volume or, in other words, the intensity of news coverage can be used as a proxy for the intent to influence popular opinion. I adopt this strategy not only for practical reasons – counting news episodes allows me to grasp trends in a large dataset – but also for theoretical ones. As I discuss above, the literature acknowledges that the Kremlin pays special attention to the intensity of news coverage of individuals and events and traces the effects of mass-media manipulations on public opinion.

The Sentiment of News Reports

To determine the sentiment of news reports, I used Rubert-tiny, a model which is based on a set of Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) (Devlin et al., Citation2018) and fine-tuned on Russian-language datasets.Footnote9 Rubert-tiny was selected based on availability (trained on the largest set of Russian-language corpora) and functionality (can be used for sentiment analysis). The model estimates the predicted probabilities of three classes (positive, negative, or neutral), selects the class with the highest probability, and assigns labels to each document in a corpus accordingly. It also calculates one-dimensional estimates of a sentiment score for each document, ranging from –1 to +1, with a score of zero indicating relative neutrality of a document and higher sentiment score signifying more positive sentiment. These scores, in addition to the three class labels, were be used for comparative analysis ().

Table 1. Sentiment analysis: classification results.

NLP techniques are relatively new to the study of political science, which is both a merit and a drawback. On one hand, they help label a large dataset without the involvement of human coders. On the other hand, the question remains, what does it mean for a story to be labeled positive, negative, or neutral? To illustrate the technique, in the Appendix (A3), I provide examples of news reports labeled as negative, neutral, and positive.

Country-Topics of News Reports

Every news episode in the corpus was labeled with the most likely country-topic of news report using Newsmap (Watanabe, Citation2018), a semi-supervised classifier.Footnote10 Newsmap substitutes manual coding of news stories with dictionary-based labeling to extract geographical words from a corpus. The model calculates association scores of words based on co-occurrences, and, therefore, does not require any human coders’ involvement or syntactical analysis of a corpus. First, the system searches individual documents for keywords from a seed dictionary and assigns class labels (countries); second, it aggregates the frequency of words according to the class labels and creates contingency tables. At the final stage, the model labels each news item with the most-likely country-topic of news origin.

Validation of the Classification Results

The results of the classification obtained with Rubert-tiny and Newsmap have been validated by human coders. Two annotators, fluent in Russian as their first language and familiar with the context of Russian politics and the social sphere, were assigned identical unlabeled samples from the corpus (n = 600). The size of the dataset was selected with an aim to maximize human validation within logistical constraints (Song et al., Citation2020). The coders were instructed to independently read and label each story as positive, negative, or neutral, taking on the perspective of Channel One’s audience. Additionally, the coders were instructed to suggest the most-likely country-topic of a news event.

Each sample comprised 100 stories that were randomly selected from the corpus, aiming to estimate the accuracy of Rubert-tiny and Newsmap and 300 stories that were randomly selected from the subsets of the corpus for each sentiment-class, aiming to estimate the precision for the “positive,” “negative,” and “neutral” classes. Additionally, 200 stories, 50 for each country-topic, were randomly selected from the subsets of the corpus that were labeled as covering the most-popular country-topics (). Based on the labeling, the accuracy score of Rubert-tiny amounted to 81%, while the precision amounted to 81% for “negative,” 82% for “neutral,” and 95% for “positive” classes. The estimate of the accuracy score for Newsmap amounted to 89%, while the precision estimates for the labels “Russia,” “US,” “Ukraine,” “United Kingdom” were 100%, 84%, 94%, and 86% respectively. In all the cases, Krippendorff’s alpha was not lower than 0.90 (See A5 in the Appendix).

Most of the misclassified cases for Newsmap can be attributed to news that involves international organizations, outer space-related events, and economic reports that are not associated with any specific country. The reports on US involvement in Syria have been typically classified as news about Syria. The reports on the Western reaction to events in Ukraine have been typically classified as news that focuses on Ukraine.

Putin’s Premiership During Medvedev’s Presidency

From May 7, 2008 to May 7, 2012, Dmitry Medvedev served as the President of Russia, whereas Vladimir Putin assumed the position of Prime Minister. My research design does not exclude this period from the analysis and treats Putin as a leader of the state regardless of his title. The literature suggests that Putin remained a pivotal figure in Russia’s political landscape and chose to work in “tandem” with Medvedev only because Russia’s constitution barred him from serving as the president for a third consecutive term (Greene & Robertson, Citation2019, pp. 20–22; Zygarʹ, Citation2016, pp. 117–128). In this respect, Dobson (Citation2012, pp. 20–20) notes that mass media were instructed to cover Putin extensively during this period.

Subjects of the Stories

News content, of course, is not limited to geography and entails other topics, both covered and omitted. To draw a better picture of news narratives, I conducted several procedures. First, using a subset of the sentences that mention Putin, I created and compared a list of the most frequent words, an analogous list based only on domestic stories, and separate lists for each presidential term.Footnote11 This technique helped uncover the variation in the narratives; in other words, as Carter and Carter (Citation2023, p. 31) explain:

The words that are common in one corpus and uncommon in another are distinctive. They convey something meaningful about content in the corpora relative to another. Semantic distinctiveness is useful for capturing the subtleties embedded within millions of propaganda articles.

Additionally, relying on explorative analysis using topic modeling, I selected four broad and distinguishable themes mentioned in domestic news: (1) economic and business, (2) social welfare, health services, and education, (3) national army and security, and (4) cultural affairs, sporting events, and formal ceremonies. While the topics are solely based on the data from Channel One, they are close to those outlined in the relevant literature (Guriev & Treisman, Citation2019; Carter & Carter, Citation2023, pp. 173–227; Baturo & Elkink, Citation2021, pp. 139–160). After a manual inspection of the features, I created four dictionaries, which allowed me to compare the mentions of Putin within each category.Footnote12 Although the themes frequently overlapped and certain stories did not cover any of the themes, this approach helped me label 84% of domestic stories that mention the ruler.

Results

The analysis reveals evidence in support H1 (Sentiment) and H3 (Country-topics) but demonstrates only partial evidence in favor of – or against – H2 (Frequency).

H1 (Sentiment)

The results show that Putin was more frequently mentioned in the news reports labeled as more positive (). The regression analysis of the output of Rubert-tiny reveals a positive and statistically significant link between the positive sentiment of a story and a variable that equals one if the story involves Putin. The linear regression coefficient for a dummy variable that equals one if a story mentions Putin and one-dimensional estimate for the sentiment is positive and statistically significant. The logistic regression coefficients for dummy variables for the sentiment labels assigned by Rubert-tiny also show that more positive stories are more likely to involve Putin. I interpret these findings as evidence in support of H1.Footnote13

further illustrates the findings by providing the distribution of the sentiment scores for all stories, separately depicting those that involve Putin. Overall, 23% of the stories in the corpus were labeled as negative, 52% as neutral, and 25% as positive. The related shares for the stories that involve Putin are 9%, 56%, and 34%.

H2 (Frequency)

Although the data reveals that the share of news reports that involve the ruler started to gradually increase from 2012 (, ), the evidence is favor of – or against – H2 is only partial. On average, Vladimir Putin was mentioned in 13% of the news episodes during his first presidential term (2000–2004), 10% during the second (2004–2008), 6% during his premiership (2008–2012), 13% during the third (2012–2018), and in 20% during the period between the beginning of his fourth presidential term (2018) and February 23, 2022 (). These findings are partially in line with Baturo and Elkink (Citation2021, pp. 139–160), who do not observe strong evidence of mass-media personalization of the ruler.

Table 2. Daily references to Putin.

The regression analysis of the link between the daily share of news episodes that mention the ruler and dummy variables for the presidential terms, with term one as the reference category, reveals analogous results (). Although the coefficient for a variable for Putin’s fourth term is higher than the coefficients for the variables for the other terms, the evidence of a gradual and consistent increase is only evident for the last term. However, this revealed strategy of mass-media management requires contextual consideration, as the ruler by far remained the most popular politician in the Russian media landscape (A9 in the Appendix).

H3 (Country-Topics)

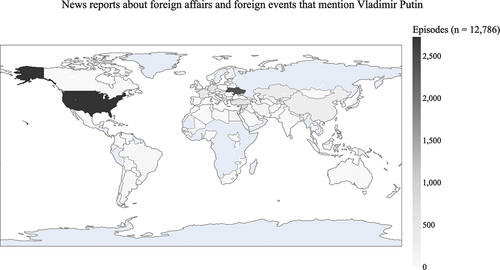

The share of news about foreign affairs and events in reports that mention Vladimir Putin has been gradually increasing from 2013 (), after Russia’s economy began to shrink. The ruler was covered by 3% of the news about foreign affairs and events abroad in 2012, 5% in 2013, 8% in 2014, 9% in 2015, 10% in 2016, 12% in 2017, 14% in 2018, 2019, and 2020, 18% in 2021, and 24% in the first two months of 2022. These findings are, again, in line with Baturo and Elkink (Citation2021, p. 157), who document that the topic of international politics became the most salient in Putin’s speeches from 2015.Footnote14 The results are also consistent with Aytaç (Citation2021), who describes Erdoğan’s strategies during economic crisis. Fluctuations in the share of news about foreign affairs and events (inverse for domestic news in ) imply that the new tendency in mass-media representation of the dictator has not resulted from general fluctuations in mass-media attention to foreign policy or sensationalism attributed to the annexation of Crimea. In other words, although the domestic media’s focus on foreign events increased over time, the shift in the coverage of the ruler occurred not solely due to this tendency, but in addition to it ().

However, importantly, every year from 2000 to the first two months of 2022, Vladimir Putin has been more frequently mentioned in reports that cover domestic events than in stories about foreign affairs and news originating abroad (). On average, news about foreign affairs and events amounted to 28% of all reports that covered the ruler during his first term in power (2000–2004), 24% during his second presidential term (2004–2008), 13% during his premiership (2008–2012), 35% during his third presidential term (2012–2018), and 27% during the period between the beginning of his fourth presidential term (2018) and February 23, 2022 (). The coverage was primarily focused on Ukraine and the United States ().

Subjects of the Stories

During most of his presidential terms, the most frequent words in the sentences mentioning Putin were verbs (“said,” “noted,” “declared,” “conducted,” “met,” “emphasized,” “discussed”) and nouns related to communication (“meeting,” “negotiation”),Footnote15 which can be interpreted as a sign of relatively neutral coverage of the ruler. Nouns (mostly related to economics and development) were only prevalent in the sentences that mentioned Putin during his premiership under Medvedev’s presidency, which is in line with Zygar’s observation (Zygarʹ, Citation2016, p. 130): “Putin assigned the role of cash dispenser to Dmitry Medvedev … to make him more recognizable to voters, he needed to be moved to a more prominent position.” I also find that state-controlled mass media emphasized regional development, meetings with governors, and governors’ responsibilities.

The analysis of the most prevalent themes (topics) in domestic news that refer to Putin does not reveal radical changes in narratives over time. In all presidential terms, Putin was mentioned in the news about (1) economics and business, followed by (2) social welfare, health services, and education, (3) cultural affairs, sporting events, and ceremonies, and (4) national security and the army. These findings are partially in line with Sonnevend and Kövesdi (Citation2023), who study the image-making of Viktor Orbán on Facebook and document that the ruler is portrayed as a symbolic condensation of the nation, a relatable politician, and a strong competence in elite political contexts. The results support the idea of Guriev and Treisman (Citation2022) that spin dictators create an image of skilled managers at home. However, my analysis additionally shows that the mass-media strategy regarding domestic news has not changed dramatically during the economic downturn in the last presidential terms. Yet, as I discuss above, it should be noted that news that mention the dictator are more likely to express positive sentimentcompared to all other news stories.

Discussion and Conclusion

Drawing on 385,981 news reports from television network Channel One, this article examined the mass-media coverage of the dictator over time from three different angles: the sentiment of the stories, the intensity of coverage, and the country-topics. The study found only partial evidence of mass-media personalization over time, which can be attributed to the ruler’s understanding that excessive personalization may backfire, and his attempt to craft subtle propaganda rather than foster a personality cult. The study also discovered that the stories involving the leader were consistently more positive compared to other news. During every year from 2000 to the first two months of 2022, the ruler has been mentioned more frequently in stories about domestic events than in those concerning foreign affairs; however, since 2013, the share of news reports about foreign affairs and events abroad that mention the ruler have been increasing steadily. These findings are informative in the context of Russia’s economy and public opinion.

Political scientists often argue that from 2000 to 2012, when oil prices were soaring, Putin took advantage of increased prosperity by portraying himself in mass media as a competent manager, whereas from 2012, when Russian economy began to shrink, he shifted his media agenda to focus on foreign affairs (Frye, Citation2022, pp. 17, 148–151; Sharafutdinova, Citation2020, pp. 15–16, 22). To the best of my knowledge, this claim rarely relied on any systematic analysis of news reports. My analysis proves the claim to be rather accurate but provides an important caveat. While from his third presidential term, Putin indeed began to increasingly exploit foreign agenda in his mass-media image, the share of domestic news reports that mention the ruler did not drop. In other words, from 2013, mass media continued to portray Putin as a servant of the people at home, and, in addition, began to increasingly promote his persona as an advocate for Russia’s interests abroad.

The share of news about foreign policy in the media coverage of the dictator rose in line with popular nationalistic attitudes in Russia. Putin’s third term in power exhibited a long-term upsurge in presidential approval, national pride, trust in the army, and the perception of Russia as a great power (Levada-Center, Citation2019a; Greene & Robertson, Citation2019, pp. 87–121). Of course, it is still unclear to what extent popular opinion has been influencing the decisions of propagandists to change the media image of the ruler and to what extent propaganda itself has been influencing popular opinion during the period. Nonetheless, my results offer fact-based evidence of the transformations in the media image of the dictator and add to the argument that the strategies of autocratic rulers are often adapted to circumstances (Frye, Citation2022; Lankina & Watanabe, Citation2017), challenging an alternative view that a dictator’s popularity results from his personality and values (Bratton & Van de Walle, Citation1997; Jackson et al., Citation1982). More broadly, my findings contribute to the scholarship on autocratic resilience, which remains an understudied area of political science (Frantz & Ezrow, Citation2022).

Additionally, by providing evidence of the surgical use of propaganda in an autocracy with nominally democratic institutions, this article contributes to the recently growing body of research on mass-media management strategies in autocracies (Carter & Carter, Citation2023). Indeed, the methods of propaganda vary across and within regimes. Even the Soviet propagandas of Lenin, Stalin, and Khrushchev differed in their techniques, themes, and symbolism (Ellul, Citation2001, p. 62). In this context, a relatively new form of mass-media manipulation – domestic propaganda in Putin’s Russia – has not been sufficiently scrutinized. By examining the case of Putin’s Russia, this article sheds light on the mass-media management strategies employed by a present-day spin dictator.

Russia is not a unique case of a personalist autocracy with nominally democratic institutions and state control over major mass-media outlets. Other examples include Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Uganda. The literature suggests that in such states, national control over mass media may help generate genuine support for the rulers (Carter & Carter, Citation2023). For instance, the evidence from Venezuela shows that closing the opposition TV station helped increase Chavez’s public support – but only in cases where viewers could not switch to another opposition network (Knight & Tribin, Citation2019). Based on the findings from this article and on the theoretical framework it employed, it is reasonable to expect that other personalist autocracies with nominally democratic institutions, when attempting to manage news flows to bolster support for their leaders, would also resort to covert mass-media manipulation rather than establish an old-school personality cult. However, the literature on mass-media coverage of present-day personalist dictators is scarce, and further research may help examine if my proposition holds true.

Besides the key findings, the study reveals that news reporting about Putin was less intense during Medvedev’s presidency, despite instructions to the mass media for extensive coverage. While this observation can be explained by the simple fact that Putin had to share media space with Medvedev, there are broader nuances to consider, which may provide a direction for future research. The observation suggests that under certain circumstances, an autocrat may choose to relinquish some of his media attention to adhere to the constraints imposed by nominally democratic institutions – in Russia’s case, a two-term presidency limit.

Two limitations of this study are worth mentioning. To analyze news-management strategies, I used TV transcripts because, as I explain above, most of the population in Putin’s Russia received their news from television. However, other media, especially domestic online platforms, are also employed by autocracies to manufacture consent for the regime. While analyzing these outlets is beyond the scope of my study, they represent avenues for further research for scholars interested in understanding how media aids autocratic regimes’ survival.

Another limitation arises from depending on text-as-data methods. Grimmer and Stewart (Citation2013) argue that automated content analysis will never replace close reading of text. To overcome the various limitations of my methodology, I extensively used validation. However, judging from the conservative logic that “all quantitative models of language are wrong – but some are useful,” it is important to remember that while my methodology was a feasible way to analyze such a large collection of news transcripts, it is less precise and less accurate than a thorough study with the involvement of human coders.

Open scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badge for Open Data. The data are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZU1T0C.

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badge for Open Data. The data are openly accessible at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZU1T0C.

Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (51.1 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2024.2380438

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lanabi La Lova

Lanabi La Lova is a postdoctoral researcher at the European Institute at the London School of Economics and Political Science. She uses data science-based approaches to study autocratic resilience and transitional justice.

Notes

1. Also referred to as informational autocrats (Guriev & Treisman, Citation2019) and democratators (Simon, Citation2014).

2. Also referred to as propaganda as signaling (Huang, Citation2015).

3. I refer to a dictator as he due to the lack of examples of female dictators (Gandhi & Przeworshi, Citation2006).

4. However, the degree of its usage varies and is likely to be linked to the constraints imposed by nominally democratic institutions (Carter & Carter, Citation2023).

5. On Viktor Orban being a classical example of an informational autocrat rather than a democratic leader, see Simon (Citation2014, p. 33) and Guriev and Treisman (Citation2022, p. 221), who offer a further literature review.

6. Baturo and Elkink (Citation2021) do not detail the exact size and structure of the corpus they analyzed.

7. A subsidiary of a state-controlled corporation PJSC Gazprom.

8. In A1 and A3 of the Appendix, I provide the examples of a news transcripts.

9. See A2 in the Appendix for more details about RuBERT-tiny.

10. See A4 in the Appendix for more details about Newsmap. Since a model trained on a larger dataset is expected to produce more accurate and precise results, the labels were assigned based on a larger dataset spanning from December 23, 1998 until June 20, 2022.

11. See A6 and A7 in the Appendix for more details about the most frequent words.

12. See A8 in the Appendix for more details about the dictionaries.

13. The stories mentioning Putin are, on average, 50,3% longer than all the other stories (the difference is statistically significant at 0.01 level), therefore, controlling for the length of the episodes may only strengthen the results in favor of H1.

14. The analysis of Baturo and Elkink (Citation2021, pp. 139–160) is focused on 2000–2008 and 2012–2018.

15. A5–6 in Online Appendix.

References

- Alrababa’h, A., & Blaydes, L. (2021). Authoritarian media and diversionary threats: Lessons from 30 years of Syrian state discourse. Political Science Research and Methods, 9(4), 693–708. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2020.28

- Aytaç, S. E. (2021). Effectiveness of incumbent’s strategic communication during economic crisis under electoral authoritarianism: Evidence from Turkey. The American Political Science Review, 115(4), 1517–1523. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000587

- Baser, B., & Öztürk, A. E. (2017). Authoritarian politics in Turkey: Elections, resistance and the AKP. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Baturo, A., & Elkink, J. (2021). The new kremlinology: Understanding regime personalization in Russia. Oxford University Press.

- Bratton, M., & Van de Walle, N. (1997). Democratic experiments in Africa: Regime transitions in comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press.

- Carter, E. B., & Carter, B. L. (2023). Propaganda in autocracies: Institutions, information, and the politics of belief. Cambridge University Press.

- Chang, C. (2021). Information credibility under authoritarian rule: Evidence from China. Political Communication, 38(6), 793–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2021.1901806

- Chang, C. (2024). The art of self-criticism: How autocrats propagate their own political scandals. Political Communication, 41(3), 461–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2024.2303166

- Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2018). Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding.

- Dikötter, F. (2019). How to be a dictator: The cult of personality in the twentieth century. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

- Dobson, W. J. (2012). The dictator’s learning curve: Inside the global battle for democracy. Random House.

- Dukalskis, A., & Gerschewski, J. (2018). What autocracies say (and what citizens hear): Proposing four mechanisms of autocratic legitimation. In A. Dukalskis & J. Gerschweski (Eds.), Justifying dictatorship: Studies in autocratic legitimation (pp. 1–18). Routledge.

- Ellul, J. (2001). Propaganda: The formation of men’s attitudes. Vintage. ( Original work published 1965).

- Ezrow, N. M., & Frantz, E. (2011). Dictators and dictatorships: Understanding authoritarian regimes and their leaders. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

- Ford, G. (1935). Dictatorship in the modern world. University of Minnesota Press.

- Frantz, E., & Ezrow, N. (2022). The politics of dictatorship: Institutions and outcomes in authoritarian regimes. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Frye, T. (2022). Weak strongman: The limits of power in Putin’s Russia. Princeton University Press.

- Gandhi, J., & Przeworski, A. (2006). Cooperation, cooptation, and rebellion under dictatorships. Economics & Politics, 18(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0343.2006.00160.x

- Geddes, B., Wright, J. G., & Frantz, E. (2018). How dictatorships work: Power, personalization, and collapse. Cambridge University Press.

- Gehlbach, S., & Sonin, K. (2014). Government control of the media. Journal of Public Economics, 118, 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.06.004

- Gläßel, C., & Paula, K. (2020). Sometimes less is more: Censorship, news falsification, and disapproval in 1989 East Germany. American Journal of Political Science, 64(3), 682–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12501

- Greene, S. A., & Robertson, G. B. (2019). Putin v. The people: The perilous politics of a divided Russia. Yale University Press.

- Grimmer, J., & Stewart, B. M. (2013). Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Political Analysis, 21(3), 267–297. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mps028

- Guriev, S., & Treisman, D. (2019). Informational autocrats. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 100–127. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.4.100

- Guriev, S., & Treisman, D. (2022). Spin dictators: The changing face of tyranny in the 21st century. Princeton University Press.

- Horz, C. M. (2021). Propaganda and skepticism. American Journal of Political Science, 65(3), 717–732. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12592

- Huang, H. (2015). Propaganda as signaling. Comparative Politics, 47(4), 419–444. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041515816103220

- Hutchings, S., & Tolz, V. (2015). Nation, ethnicity and race on Russian television: Mediating post-Soviet difference. Routledge.

- Jackson, R. H., Jackson, R. H., & Rosberg, C. G. (1982). Personal rule in Black Africa: Prince, autocrat, prophet, tyrant. University of California Press.

- Kershaw, I. (2013). The “hitler myth”: Image and reality in the third reich. In D. Crew (Ed.), Nazism and German society (pp. 1933–1945). Routledge.

- Knight, B., & Tribin, A. (2019). The limits of propaganda: Evidence from Chavez’s Venezuela. Journal of the European Economic Association, 17(2), 567–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvy012

- Lankina, T., & Watanabe, K. (2017). ‘Russian spring’or ‘Spring betrayal’? The media as a mirror of Putin’s evolving strategy in Ukraine. Europe-Asia Studies, 69(10), 1526–1556. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2017.1397603

- Levada-Center. (2014). Report. Foreign languages skills 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2023, from https://www.levada.ru/2014/05/28/vladenie-inostrannymi-yazykami/

- Levada-Center. (2019a). Report. National identity and pride. Retrieved June 9, 2023, from https://www.levada.ru/2019/01/17/natsionalnaya-identichnost-i-gordost/

- Levada-Center. (2019b). Report. Russian media landscape 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2023, from https://www.levada.ru/2019/08/01/21088/

- Levada-Center. (2021). Report. Russian media landscape 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2023, from https://www.levada.ru/2021/08/05/rossijskij-medialandshaft-2021/

- Lipman, M., Kachkaeva, A., & Poyker, M. (2018). Media in Russia: Between modernization and monopoly. In D. Treisman (Ed.), The new autocracy: Information, politics, and policy in Putin’s Russia (pp. 159–190). Brookings Institution Press.

- McGlynn, J. (2023). Memory makers: The politics of the past in Putin’s Russia. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Moghaddam, F. M. (2013). The psychology of dictatorship. American Psychological Association.

- Oakes, A. (2012). Diversionary war: Domestic unrest and international conflict. Stanford University Press.

- Otlan, Y., Kuzmina, Y., Rumiantseva, A., & Tertytchnaya, K. (2023). Authoritarian media and foreign protests: Evidence from a decade of Russian news. Post-Soviet Affairs, 39(6), 391–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2023.2264079

- Paskhalis, T., Rosenfeld, B., & Tertytchnaya, K. (2022). Independent media under pressure: Evidence from Russia. Post-Soviet Affairs, 38(3), 155–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2022.2065840

- Pratkanis, A. R., & Aronson, E. (2001). Age of propaganda: The everyday use and abuse of persuasion. Macmillan.

- Rogov, K., & Ananyev, M. (2018). Public opinion and Russian politics. In D. Treisman (Ed.), The new autocracy: Information, politics, and policy in Putin’s Russia (pp. 191–216). Brookings Institution Press.

- Rozenas, A., & Stukal, D. (2019). How autocrats manipulate economic news: Evidence from Russia’s state-controlled television. The Journal of Politics, 81(3), 982–996. https://doi.org/10.1086/703208

- Sharafutdinova, G. (2020). The red mirror: Putin’s leadership and Russia’s insecure identity. Oxford University Press.

- Simon, J. (2014). The new censorship: Inside the global battle for media freedom. Columbia University Press.

- Song, H., Tolochko, P., Eberl, J.-M., Eisele, O., Greussing, E., Heidenreich, T., Lind, F., Galyga, S., & Boomgaarden, H. G. (2020). In validations we trust? The impact of imperfect human annotations as a gold standard on the quality of validation of automated content analysis. Political Communication, 37(4), 550–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1723752

- Sonnevend, J., & Kövesdi, V. (2023). More than just a strongman: The strategic construction of Viktor Orbán’s charismatic authority on facebook. The International Journal of Press/politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612231179120

- Soroka, S., & McAdams, S. (2015). News, politics, and negativity. Political Communication, 32(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.881942

- Sperling, V. (2016). Putin’s macho personality cult. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 49(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2015.12.001

- Svolik, M. W. (2012). The politics of authoritarian rule. Cambridge University Press.

- Wang, C. Y. (2023). The ideology if blowing in the wind: Managing orthododoxy and popularity in China’s propaganda. Political Communication, 41(3), 435–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2023.2290492

- Watanabe, K. (2018). Newsmap: A semi-supervised approach to geographical news classification. Digital Journalism, 6(3), 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1293487

- Zygarʹ, M. (2016). All the Kremlin’s men: Inside the court of Vladimir Putin. PublicAffairs.