ABSTRACT

In 1903, Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924) opened a most personal museum in which the building, the collection and installations are the vision of one woman, at a time when few opportunities were available to her gender in America. In its 2019–2024 strategic plan, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum committed to becoming a more visitor-centric art museum that prioritizes welcoming a broader audience than ever before. Through innovative exhibitions that link the past to today, and by investing its energy and resources in both its collection presentation and the visitors who engage with it, we ensure that Gardner’s museum is truly “for the education and enjoyment of the public forever.”

A museum that never changes

Opened in 1903, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (ISGM) recalls the design of a Venetian palazzo or palace. A seasoned traveler and global explorer nearly all of her life, Isabella Stewart Gardner grounded her “Fenway Court,” as it was known in her time, with a central courtyard, with one central twist: the pink stucco walls that are often found on the exterior of Venetian palaces has been flipped to the inside courtyard walls, surrounding lush plants, flowers, ancient Roman sculptures and a mosaic (). She then filled three floors of rooms and galleries around the courtyard with all kinds of art spanning the ages: over 7500 objects (including paintings, sculpture, drawings, prints, furniture, textiles, metalwork, architectural fragments, and other bric-a-brac), 1500 books, and over 7000 pieces of archival material.

Figure 1. Courtyard with nasturtium display, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Sean Dungan.

Her collection is best known for European Medieval and Italian Renaissance art and nineteenth-century American painting. The museum features artwork from around the world, pieces that demonstrate her interest in exploring different continents and cultures throughout her life. Wherever she traveled and when she was home in Boston, she surrounded herself with family, friends, artists, poets, and performers including Joseph Lindon Smith, Ralph Curtis, Violet Paget, Anders Zorn, Henry James, John Singer Sargent, Antonio Mancini,Footnote1 as well as Okakura Kakuzo, Charles Eliot Norton, James McNeill Whistler, many of whom informed her learning and collection, and inspired her – and in return, she supported and inspired them through active patronage and regular professional and social gatherings. She also supported the development and education of many young scholars and artists, including Bernard Berenson, F. Marion Crawford and Dennis Miller Bunker.Footnote2 For twenty years, the museum inspired and dazzled everyone who walked through the doors.

Gardner (1840–1924) had a personal, unique vision for her eponymous museum, as well as a clever way to ensure it remained as she installed it, in perpetuity. When she passed away in 1924, her last will and testament gave explicit directions that “no works of art shall be placed [within the museum] other than I, or the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in the Fenway, Incorporated, own or have contracted for at my death.”Footnote3 Thus, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum is a rare art museum in which the building, the collection, and its installations are the vision of one person, “a Museum for the education and enjoyment of the public forever … ”Footnote4

The challenges of forever

Unlike many art museums with deep collections, a fraction of which are on display at any given time, the entire Gardner Museum collection is on view permanently. Nothing may ever be added, changed or removed; the art and installations must always be just how she left them.Footnote5 Since her will insures a consistent display, visitors often consider the Gardner Museum as a “one and done” type of place. After visiting once, they do not need to come back, which challenges us to consider how to develop return visitors out of both existing and new audiences.

Furthermore, Gardner’s privilege informed her lens as she traveled around the world and later built her collection which visibly shows her Eurocentric tastes. A majority of the figures in the museum are represented with fair or white skin tones; people of color often do not see themselves reflected in the art. Not one drawn to convention, Gardner did not approach her museum in the typical manner. The galleries and artworks are not labeled, nor are the artworks arranged chronologically or categorically. Relatively little of her copious correspondence survives, and although she created several guidebooks to the collection, she did not write or document her rationale for how the museum is arranged. This lack of information can frustrate today’s seasoned museum goer who looks for the labels, while alienating first-time visitors who may feel they lack the background knowledge or access to resources to make meaning with the collection.

Renewing the promise: for the public forever; strategic plan 2019–2024

The Gardner, like many museums today, recognizes that in order to become relevant to a broader range of audiences it has to consider ways of reaching more local, diverse, and younger audiences. The Museums As Site for Social Action (MASS Action) Toolkit explains,

the real business case for museums is relevance. With the reality of changing demographics, the change is not reflected in who museums serve. The traditional audience for museums has been white. As that segments declines in relation to other segments, museums must provide value to a much broader segment of society, those that have been traditionally marginalized by museums.Footnote6

In the 1970s, nearly 70% of Boston was white, in contrast to now, 40 years later, with only 47% of the city’s population is white.Footnote7 The Gardner’s 2019 annual visitor demographics showed about 35% of visitors are local (within the 495 interstate) and 42% are young adults between the ages of 18–34 years old. While our number of young adult visitors echo the city’s demographics, we are far from reflecting the racial and ethnicity of the city of Boston. And just over 14% of Gardner employees are people of color.

To address these disparities, in 2018–19 the Gardner Museum created a strategic plan with Isabella Stewart Gardner as the guiding force of its rationale:

this Strategic Plan propels Isabella's vision into the twenty-first century. It is fueled by our ambition to make the museum not only more welcoming to diverse audiences, but more reflective of the many voices and perspectives that comprise the vibrant communities we serve.Footnote8

Creativity is our Legacy. We celebrate our founder’s passion for innovation and risk-taking, and her dedication to multidisciplinary experiences of art. We carry forth her commitment to contemporary artists and creators to share and explore new perspectives and new work.

Community is our Purpose. We are dedicated to making our collections, exhibitions, and programs relevant and welcoming to all audiences.

The Collection is our Catalyst. Our collection expresses both individual and universal human experiences in ways that are distinctive and inspiring. We have an imperative to care for the collection, to explore its complex histories, and to demonstrate its enduring relevance in a changing world.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion are our Commitments. We will continue to build a culture of diversity, equity, and inclusion in holistic ways that inspire all aspects of our work, from exhibition interpretation to staff development. Our fundamental goal is for visitors, staff, volunteers, and trustees of all backgrounds to experience the Gardner as a place of community and respect.Footnote9 Over the next 5 years, we have committed to dramatically increase the racial diversity while also encourage more younger adults in ages 18–34 and more local visitors to visit.

The founder’s legacy and twenty-first-century museum education practice

Isabella Stewart Gardner drives the uniqueness of the Gardner Museum. The museum staff and board have embraced Gardner’s will while simultaneously recognizing the challenges it creates in the processes needed to transform into an even more visitor-centric museum. The Gardner Museum maintains its relevance as a place for art and a sanctuary for the people, but this is now achieved in ways Gardner would never have imagined because the definition of “the public” has changed. The world we now live in demands inclusivity and belonging as moral imperatives.

Growing attendance, new spaces

The [Gardner] must always remain ‘live,’ for that was the idea in the original conception and in the execution of the idea, a living message of … art to each generation. (Olga Monks, niece of Isabella Stewart Gardner)Footnote10

In order to expand spaces and resources, the board and staff took the bold step in 2009 of legally amending Gardner’s will, seeking permission to add a new building to the founder’s historic building.Footnote12 Permission was granted and the 70,000 square foot new wing, designed by Renzo Piano, opened in 2012 to 240,000 annual visitors, added much-needed visitor amenities such as café, gift shop, gallery space for rotating special exhibitions, concert hall, orientation room, expanded coat check and restrooms, education studio, and lobby for admissions.Footnote13 By 2019, the annual attendance grew again by 50% to over 345,000, transforming the Gardner into a museum that now requires different approaches to education and interpretation.

Understanding visitor experience

On days the museum was open to the public, family friend Louise Endicott noted that Gardner was, “eager to see how it all affects people … and ready to explain everything to enquiring people.”Footnote14 She also created a guidebook to the collection, which mapped a specific route for moving through the Museum. It was clearly important to Isabella Stewart Gardner for visitors to get the most out of their museum visit, a legacy that continues today.

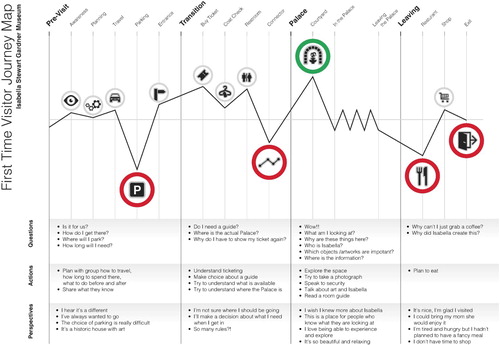

As the attendance steadily grew over the past few years, we began to focus more on the general visitor experience. In 2016 we partnered with Frankly, Green + WebbFootnote15 to interview visitors–both “super fans” who were already familiar with the Gardner Museum and first-time visitors, and created a visitor journey map that described trends in overall visitor experience. We plotted actions, thinking, and feelings that exist from the moment a visitor decided to visit, what happened during the visit (entry experience, in the galleries, did they eat at the restaurant), how they decided to leave, and how they talked about or shared their experience with others afterwards. Asking visitors about every decision and the factors that impacted it was fascinating and helped staff understand many visitors’ points of view, and understand how they experienced the museum.

All visitors struggled at the same “pain points” in the journey (); it was hard to find parking, a line frequently formed to enter, and an additional line to the coat check was frequently long, and it was challenging to find information about the artwork in the galleries. Coat check was an issue At the same time, most visitors named the courtyard to be a highlight, and a place they would like to visit again to share with friends. An important motivator for visitors was the social aspect–they enjoyed visiting with friends, in a different place than they typically spent time–that was more of a driver that seeing the art.

Figure 2. First Time Visitor Journey Map, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Image: Frankly Green + Webb, Oakland.

Line chart entitled “First Time Visitor Journey Map, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.” Across the top, a museum visit is broken down into the chronological steps: “Pre-Visit,” “Transition,” “Palace,” and “Leaving.” There are sub-steps for each of those. Along the bottom, visitor questions, actions and perspectives for each step of a museum visit are listed. In the middle, a line graph with icons charts the visitor journey. During the Pre-Visit portion of the visitor journey, sub-step “Awareness” leads to an increase in the line graph with an icon of an eye. “Pre-Visit: Planning” leads to a decrease on the line graph with an icon of gears. “Pre-Visit: Travel” leads to an increase on the graph with an icon of a car. “Pre-Visit: Parking” leads to an extreme decrease on the graph with a parking icon circled in red. “Pre-Visit: Entrance” leads to an extreme increase on the graph with an icon of a wayfinding sign. “Questions” for the “Pre-Visit Section:” “Is it for us? How do I get there? Where will I park? How long will I need?” “Actions” for this section: Plan with group how to travel, how long to spend there, what to do before and after, share what they know. “Perspectives” for this section: “I hear it’s a different, I’ve always wanted to go, the choice of parking it really difficult, it’s a historic house with art.” The next step of the journey listed on the top of the graph is “Transition.” “Transition: Buy Ticket” leads to an increase on the chart with an icon of a ticket. “Transition: Coat Check” leads to a decrease on the graph with an icon of a hanger. “Transition: Restroom” leads to an increase with an icon of a male/female restroom sign. “Transition: Connector” leads to an extreme decrease with an icon of a line graph circled in red. “Questions” listed for the “Transition” section: “Do I need a guide? Where is the actual Palace? Why do I have to show my ticket again?” “Actions” for the “Transition” section: understand ticketing, make choice about a guide, try to understand what is available, try to understand where the Palace is. “Perspectives” from the “Transition” section: “I’m not sure where I should be going, I’ll make a decision about what I need when I get in, So many rules?!” The “Palace” step of the visitor journey is listed next. “Palace: Courtyard” leads to an extreme increase on the graph with an icon of an arch and fountain circled in green. Between “Transition: In the Palace” and “Transition: Leaving the Palace,” the line graph goes up and down several times. There are no icons for those two sub-steps. “Questions” for “Palace”: “Wow!! What am I looking at? Why are these things here? Who is Isabella? Which objects/artworks are important? Where is the information?” “Actions” for “Palace:” explore the space, try to take a photograph, speak to security, talk about art and Isabella, read a room guide. “Perspectives” for “Palace:” “I wish I knew more about Isabella, this is a place for people who know what they are looking at, I love being able to experience and explore, It’s so beautiful and relaxing.” The last step listed is “Leaving.” “Leaving: Restaurant” leads to a large decrease on the graph with an icon of a fork and knife circled in red. “Leaving: Shop” leads to an increase with an icon of a shopping cart. “Leaving: Exit” leads to a decrease with an icon of a door and an arrow circled in red. “Questions” for “Leaving”: “What can’t I just grab a coffee? Why did Isabella create this?” “Actions” for “Leaving:” plan to eat. “Perspectives” for “Leaving:” “It’s nice, I’m glad I visited, I could bring my mom she would enjoy it, I’m tired and hungry but I hadn’t planned to have a fancy meal, I don’t have time to shop.”

This data informed the redesign of our updated website and also gave the Gardner a roadmap of areas to address in the overall visitor experience. The data helped us to define a seamless, welcoming, and personalized journey from entry to exit, which formed our first set of Visitor Experience (VX) principles:

Visitors feel welcome during their entire visit

The path from entry to art is brief

Visitors have a personal, high-touch experience (feel supported)

Visitors understand the museum’s offer (what we provide)

Visitors are able to get more information when they want it and have their questions answered all along their journey (about the founder, museum, collection)

Visitors find it easy to navigate the museum

Visitor needs to pause and recharge are met

We next developed a twenty-member, cross-departmental VX team that addressed these pain points through a series of pilots: we listened to visitor questions in the galleries, partnered with a local university to offer discounted parking option, built a self-serve new locker room for visitors to store their coats and bags, switched from admission tickets to tags, and have experimented with different ways of offering layers of information and prompts for close looking in the galleries. Reports of what we discovered and the iterative ways of addressing these areas were regularly reported to the museum’s senior leadership.

Opportunities in storytelling: embracing multiple perspectives

The visitor journey data also created the content template and user experience design of several audio projects. In 2017, we updated all audio content, making it available both on our website and via rental devices. All content was also translated in its entirety into the four most requested languages: French, Japanese, Spanish, and Mandarin to ensure widest accessibility.

Our previous audio guide had over 40 stops that emphasized an art historical way of exploring the museum. However, the visitor journey mapping revealed that the visual art was not the main reason for visiting. The updated audio guideFootnote16 approach now addresses the four questions that all visitors have while exploring the Gardner Museum: Who is Isabella Stewart Gardner, why does the museum look this way, how do I get the most out of my visit and how do I find my way around this place? We transformed the audio stops from individual points about specific objects into holistic gallery overviews and we also provided navigational cues such as “with your back to the fireplace” or “look towards the courtyard” to eliminate confusion and help visitors orient themselves in each space.

In addition, to help visitors connect with the collection and see themselves reflected in the museum, we created several audio “Artist Walks.” These twenty-minute long walking audio tours are led by artists sharing “their personal impressions and discussing Isabella Stewart Gardner’s arrangements of her collection, encouraging listeners to take a closer look.”Footnote17 The artists, such as art educator and multimedia artist Elisa H. Hamilton (),Footnote18 provide visitors with a variety of entry points into the Gardner experience – connecting to themes on motherhood, asking questions about how different races are portrayed, or inviting reflections on personal transformations. This approach legitimizes the personal-meaning making that Gardner herself sought to create for visitors. By releasing different audio Artist Walks over time, we encourage “Museum Enthusiasts” to return and discover new stories and connections, while “Art Ambassadors” may share them (via social media and in person) as a practical tool to introduce the Gardner to their friends and family members.

Figure 3. Artist Elisa Hamilton in the Titian Room, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston. Photo: Author.

Contemporary art and community: neighborhood salon luminaries

Another strategic plan goal is to “create an incubator for innovation in programs and exhibitions that advances scholarly inquiry, explores relevant social issues, and tests new models of collaboration with artistic, community, and academic partners.”Footnote19 Gardner leveraged her privilege and wealth to access, support, and convene a wide range of artists across disciplines. Starting in 2016, the Gardner leveraged its role as a cultural institution, embarking on a new approach to community engagement which emphasizes deep, mutually beneficial relationship building and program co-creation over time as a means to establish trust and collaboration with local artists, creative influencers, policy-makers, and community leaders. Each year, the Director of Community Engagement and a community co-host invite up to ten artists and cultural innovators to participate in our Neighborhood Salon Luminaries program.

Just as Isabella Stewart Gardner curated her regular salons and circles of influence to include all forms of art, the Luminaries also represent a broad gamut including painters, musicians, a pastry chef, choreographers, community organizers, a DJ, and filmmakers. Together, Luminaries and Gardner Museum educators form a contemporary neighborhood salon, meeting quarterly throughout a year. The initial salon meeting is the introduction to the cohort and the Gardner Museum, including group activities in the museum galleries and an overview of upcoming programming. During the remaining three salons, the Luminaries take turns presenting projects or initiatives of personal importance. These personal forms of storytelling have included the performance of a piece of music that was written at a time of immense personal change, eating different incredible desserts, and the sharing of an autobiographical playlist. In each of these exchanges, the artists and museum educators develop deeper personal and creative understandings of one another.

The community building continues further as Gardner education team members then meet with each Luminary to learn even more about their practice, and make connections to upcoming museum exhibitions and programming–fostering opportunities for the Gardner Museum to become a cultural home for the Luminaries. Initial Luminary activities include performing a piece of music at an upcoming free day, designing an art-making project in the Education Studio, or creating a new body of work based on their experiences in the museum.Footnote20 Over time, deeper collaborations develop through commissions for a dance series for an exhibition and co-curating an evening of programming.

Equity, diversity, accessibility and inclusion are key values for this program and the Luminaries epitomize the communities that we would like to engage more: 77% of the 36 Luminaries to date (December 2019) have been people of color, 60% female and 8% gender non-conforming, and most are under the age of 40 and all live within Boston and surrounding towns.

By investing in their comfort and sense of belonging at the Gardner, we have been able to diversify audiences at our programs. The Luminaries share via social media not only the programs they themselves co-design with the Gardner, they frequently attend each other’s programs and cross-promote as well, broadening the invitation for more communities to come to the Gardner and see what connections they may find. This past summer, we saw evidence of this traction in record-high attendance (average of about 1400 people over 4 h) at our three free Neighborhood Nights. For comparison, on a typical busy day, we may have up to 1200 visitors over 6 h. While the Luminaries demonstrate for their communities what it means to feel a sense of belonging at the Gardner, they also model for our museum colleagues what is possible through these co-produced, collaborative programs. By investing this staff time and resources in the Luminaries Salon, the ISGM has enhanced museum-wide interpretation, programming, and communication planning.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion are our commitment

In her lifetime, Gardner hired Harvard students (at that time, only men) as guards, and limited the availability of tickets first in charging $1 dollar each, and secondly through their sale only through Harvard’s art department.Footnote21 While current museum programs are informed by our founder, we also do not let her hold us back.

As the museum has moved towards welcoming a wider range of visitors, it has been equally important to prepare museum staff and volunteers to understand the needs and interests of different populations. In 2019, we worked with Dina Bailey from International Coalition of Sites of ConscienceFootnote22 on four museum-wide initiatives: a cultural assessment to gauge current thinking around diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) issues, implicit bias trainings to broaden our cultural competency and increase awareness of our personal biases, facilitated dialogue workshops around challenging topics such as race and class, and a train-the-trainer workshop for an interdepartmental team build staff capacity to maintain this work and establish more DEI initiatives moving forward.

Concurrent with these foundational workshops and assessments, education team members organized a group of community conversations (both at the Gardner and in the community) around challenging issues of race, class, gender, and sexuality addressed in an exhibition, Boston’s Apollo: Thomas McKeller and John Singer Sargent, which featured a portfolio of drawings of McKeller, a Black model, that Sargent gifted to Gardner. The drawings were preliminary studies for a set of murals in the rotunda of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, murals in which McKeller’s poses were transformed into white gods and goddesses.Footnote23 These community conversations were crucial for our education and curatorial teams as well as museum leadership to better understand others’ lived experiences that are very different than our own. This tactic of strategically centering voices of local, younger, people of color revealed gaps in cultural competence as well as implicit biases in our predominantly white staff. As a result, the curator decided to share authority in the exhibition’s interpretation, asking community collaborators to write more than half of the labels. To further center McKeller’s story, we also co-developed with community team members a timeline that used his lifespan (1890–1962) as endpoints for a timeline, highlighting significant events in Boston that affected Black communities. By broadening the perspectives beyond our own, which are predominantly white and curatorial lenses, we aim to ensure authentic, meaningful connections for strategic growth audiences. While exhibition exit surveys will help us determine if we were successful, this approach to exhibition interpretation planning has already informed subsequent work, in curators’ continuing consideration of audiences.

For the education and enjoyment forever for all

While Isabella Stewart Gardner’s legacy is for her museum to remain her vision forever, her values are interpreted and re-interpreted by every generation. Through an organizational commitment to visitor data, new approaches to education and interpretation, as well as the moral imperative for new and deeper collaborations through community engagement, and dedicated resources to improve visitor experience, the Gardner Museum will become an art museum with more meaningful connections, full of education and enjoyment, forever, for all.

Acknowledgements

I would like to recognize several past and current Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (ISGM) colleagues who informed this article, including Lauren Budding, Margaret Burchenal, Sara Egan, Brian Hone, Shana McKenna, Christina Nielsen, Pieranna Cavalchini, Carolyn Royston, Nathaniel Silver, Kimberly Thompson Panay, Rhea Vedro, Wanessa Tillman, and Corinne Zimmermann. I would also like to acknowledge Laura Mann of Frankly, Green + Webb for her invaluable mentorship in visitor experience and human-centered design over the past several years. Finally, Peggy Fogelman’s leadership and vision through the ISGM strategic planning process has been a guiding force for much of the work described in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

About the author

Michelle Grohe is the Esther Stiles Eastman Curator of Education at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, Massachusetts. She works closely with other senior leaders and the Director to advance the Gardner as a distinctive provider of innovative, inspiring cultural experiences that broaden and diversify the Museum’s audiences, and expand its network of community partners, artists, and affinity groups. Grohe has a B.F.A. in studio art from Millikin University and M.A. in art + design education for museums at RISD, and served as the Museum Education Division Director on the national board of the National Art Education Association in 2017–2019.

Notes

1 Christina, Riley and Nathaniel, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 10.

2 Goldfarb, The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 14–20.

3 Christina, Riley and Silver, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 21.

4 Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Renewing the Promise, 2.

5 The exceptions to changes to Gardner’s placement of artworks are when works of art are loaned for exhibitions, and when scholarship or conservation necessitates work or study, which often leads to short-term, in-house exhibitions in designated spaces not protected by the will. These exhibitions provide visitors with opportunities to take a closer look at familiar artworks in juxtaposition with other works from the Gardner or borrowed.

6 Taylor and Kegan, “Organizational Culture and Change: Making the Case for Inclusion.”

7 Lima and Melniks. Boston: Measuring Diversity in a Changing City, 2.

8 Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Renewing the Promise, 7–8.

9 Gardner Museum. Renewing the Promise, 12.

10 Goldfarb, The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 20.

11 Shana McKenna, email to author, December 6, 2019.

12 “Now, in a victory the Gardner had been awaiting for months, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts ruled on March 4 that the museum can depart from the strict parameters of Gardner’s prickly will. It called the expansion a ‘reasonable deviation’ from the will because it is in the public interest to protect the building from overuse.” https://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/15/arts/design/15good.html

13 Jacobsen, “Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum/Renzo Piano Workshop.”

14 Hall Tharp, Mrs. Jack: A Biography of Isabella Stewart Gardner, 261.

15 Grohe and Mann, “Walking in the Shoes of Our Visitors.”

18 For more about Elisa and her work, see https://www.gardnermuseum.org/about/community-efforts/luminaries/Hamilton-elisa.

19 Gardner Museum, Renewing the Promise, 10.

20 To learn more about how the Neighborhood Salon Luminaries impact programming, see Gardner Museum, Luminaries, 2019.

21 Hall Tharp, Mrs. Jack: A Biography of Isabella Stewart Gardner, 262.

Bibliography

- Brown, Alan, and Rebecca Ratzkin. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Research Synthesis: Key Themes and Ideas from a Multi-Method Study of Visitors and Supporters. Internal Report. San Francisco, CA, 2013.

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihalyi . “Notes on Art Museum Experiences.” In Creating the Visitor-Centered Museum, edited by Peter Samis and Mimi Michaelson. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Goldfarb, Hilliard T. The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum: A Companion Guide and History. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995.

- Goodnough, Abby. “A Wounded Museum Feels a Jolt of Progress.” Accessed January 19, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/15/arts/design/15good.html.

- Grohe, Michelle, and Laura Mann. “Walking in the Shoes of our Visitors: Human-Centered Design and Organizational Change at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.” In MW19: Museums and the Web 2019. Boston, MA, 2019. https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/walking-in-the-shoes-of-our-visitors-human-centered-design-and-organizational-change-at-the-isabella-stewart-gardner-museum/.

- Hall Tharp, Louise. Mrs. Jack: A Biography of Isabella Stewart Gardner. 3rd ed. Singapore: CS Graphics, 2010.

- Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. “Neighborhood Salon Luminaries.” Accessed December 1, 2019. https://www.gardnermuseum.org/about/community-efforts/luminaries.

- Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. “The Neighborhood Salon.” Accessed December 1, 2019. https://www.gardnermuseum.org/about/luminary-co-creation#chapter2.

- Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Renewing the Promise: For the Public Forever, Strategic Plan 2019–24. Boston, MA: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, 2019. https://www.gardnermuseum.org/organization/executive-summary-2019.

- Kaplan, Kate. Where and How to Create Customer Journey Maps. Nielsen Norman Group, 2016. Published July 31, 2016. Consulted September 30, 2018. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/customer-journey-mapping/.

- Lima, Alvero, and Mark Melnik, eds. Boston: Measuring Diversity in a Changing City. Boston, MA: Boston Redevelopment Authority, Research Division, 2013. Accessed December 1, 2019. http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/1d0a0e62-c131-417e-a53d-ceccb92b5dc4/.

- Nielsen, Christina, Casey Riley, and Nathaniel Silver. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum: A Guidebook. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017.

- Perez, Sarah. “Bose Acquires Andrew Mason’s Walking Tour Startup, Detour.” TechCrunch, April 24, 2018. https://techcrunch.com/2018/04/24/bose-acquires-andrew-masons-walking-tour-startup-detour/.

- Samis, Peter, and Mimi Michaelson. Creating the Visitor-Centered Museum. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Taylor, Chris, and Mischa Kegan. “Organizational Culture and Change: Making the Case for Inclusion.” In Museum Site for Social Action Toolkit, 34–75. Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2017. PDF. Accessed December 1, 2019. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58fa685dff7c50f78be5f2b2/t/59dcdd27e5dd5b5a1b51d9d8/1507646780650/TOOLKIT_10_2017.pdf.

- United States Census Bureau. “Quick Facts City of Boston, Massachusetts.” Accessed December 1, 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/bostoncitymassachusetts.