ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic brought unprecedented changes to the museum field in 2020. Significant among these changes are losses in museum education. Using data collected from museum educators and museum directors, the authors document and contextualize what they consider incongruous, detrimental impacts on museum education. Most troubling, when examined in the context of pre-pandemic trends, the losses in education suggest a paradox of sorts. Prior to the pandemic, museum education was taking an increasingly prominent role in the museum field with audience engagement becoming an increasing priority. So, how could museums reduce education departments and their resources at a time when serving audiences is paramount? Ultimately, the losses in museum education reveal its vulnerability. Museum leadership asserts the importance of museum education, but when push comes to shove, makes significant cuts to museum education departments.

Friday the 13th. That is the unlucky date in Western superstition that the COVID-19 pandemic became a reality for many in the United States. On Friday, March 13, 2020, many states entered a lockdown of an unknown length of time. Museums shuttered, and museum educators found themselves at home doing as much as they could remotely in this wait-it-out period. But by April, it was clear that the COVID-19 pandemic was beyond the point of waiting it out. In the first week of April, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) terminated all museum educator contracts, announcing “it will be months, if not years, before we anticipate returning to budget and operations levels to require educator services.”Footnote1 For us at RK&A; the terminations at MoMA were the canary in the coal mine alerting us that the pandemic was about to take a serious toll on museum educators.Footnote2

Museum educators are the practitioners that we, as research and evaluation consultants, work most closely with; they are eager learners with an appetite for the data we can provide about audiences that will inform their practice. April left us anxious for our museum educator colleagues, but also for museums themselves. We believe in the educational role of museums and worried that adverse effects on the education departments would gut museums’ souls. Therefore, we turned to some of our close colleagues at the Museum Education division of the National Art Education Association (NAEA) to offer our research services to help support museum educators. This article grew from the seeds of the survey work we did for NAEA. What began as one survey to document the effects of the pandemic on art museum education grew into something more complicated when we were able to place the findings of our survey into the context of other similar survey data from the field. What we found confirmed our fear that museum education was affected more negatively than most other departments in museums. And paradoxically, education was still being highlighted as a museum priority despite the negative effects on education departments. In this article, we use data gathered from multiple sources to illuminate the incongruous, detrimental effects of the pandemic on museum education. We recognize these data represent just the 2020 effects on educators and do not consider any rehiring or new resource allocations into 2021.

Readers’ guide to data storytelling

Throughout the article, we generalize about museum educators – those working in all types of museums. Some of the sources we cite, however, are specific to art museums (e.g. the Association of Art Museum Directors, and Museum Education division of the National Art Education Association). For transparency, we write “(art) museum educators” when a reference is specific to art museum educators, but we, the authors, consider the reference relevant to the broader museum education audience. Further, we explicitly note when data may not be applicable to the broader museum education field.

Museum education pre-pandemic

The role of education has become increasingly central to museums throughout the course of their history. The renowned library revolutionary, museum director, and educational philosopher John Cotton Dana advocated in the early nineteenth century for a more visitor-centered museum that focused on education rather than collections.Footnote3 Dana also carved out the role we view as emblematic of museum education and museum educators today – the conduits to make the museum useful (Dana’s terminology), or relevant to visitors (in modern terminology). Despite Dana’s early acknowledgement of education as essential to museums, the role of education as a structural department within the museum and the professionalization of museum educators was tenuous throughout most of the twentieth century. For example, art museum education historian Terry Zeller (who began his career as an art and science museum educator) concluded in the 1980s, through his research into (art) museum educators and their training, that museum leadership must acknowledge the importance of education to museums and hire those with specific educational, versus curatorial, training.Footnote4 In a 1986 report published by the Getty Center for Education in the Arts, (art) museum education was deemed an “uncertain profession.”Footnote5 While the report focused on art museum educators and generated controversy, museum education professionals in other types of museums generally agreed with their assessment or, at least, agreed that the conclusions drawn were based on structural inequalities and common perceptions that have hindered the professionalization of museum educators.Footnote6

Since the 1980s, museum educators have taken on new roles and with it new influence in museums.Footnote7 In 1992, the American Association of Museums (now the American Alliance of Museums) published Excellence and Equity: Education and the Public Dimension of Museums, which placed education at the forefront of the museum’s work and called for museums to be welcoming and inclusive.Footnote8 Since then, many museum leaders (and notably those outside the role of educators) have advocated for education. At the turn of the twenty-first century, museum leader and scholar Stephen Weil called on museums to move “from being about something to being for somebody.”Footnote9 In the 2010s, museum and cultural leader and author Nina Simon provoked museums to be more inclusive and relevant cultural institutions and, through writing and public speaking, has supported museums in doing so.Footnote10 And presently, the Smithsonian’s Secretary, Lonnie Bunch, continues to make education a top priority in our nation’s museums and hopes the Smithsonian can be “not just a place to visit” but can “give people tools to live their lives.”Footnote11 In recent decades, educators have more regularly worked side by side with curators on exhibition development and, in more recent years, educators have risen in the ranks to directors of museums.Footnote12

Now, in the 2020s, education is in greater demand as Diversity, Equity, Access, and Inclusion (DEAI) work is taking a prominent role in the world.Footnote13 In January 2021, American Alliance of Museums (AAM) President and CEO Laura Lott called on museums to respond to the racial reckoning of the United States and commit to DEAI practices.Footnote14 A national landscape study of DEAI practices in museums found that museums focus more on public-facing DEAI efforts than on internal-facing work.Footnote15 While the study does not specify who is leading much of the public-facing DEAI work at museums, education is top of mind for many reasons. The principles of Excellence and Equity: Education and the Public Dimension of Museums resonate today in DEAI work.Footnote16 Furthermore, in a review of DEAI-focused initiatives, such as MASS Action, you will find no shortage of museum educators.Footnote17 Likewise, a review of museum education articles and conference sessions demonstrates the work education has been doing in DEAI.Footnote18 Therefore, it is not a far leap to state that educators’ knowledge of and experience with DEAI will continue to be critical to the museum at large particularly in efforts to ensure museums sustain their relevance to local communities.Footnote19

Despite the increased value placed on museum education, education still seems to need justification. In 2014, a Museum issue dedicated to education included an observation from AAM’s futurist Elizabeth Merritt: “Yet museum people find themselves having to explain, over and over, that museums are fundamentally educational institutions with learning embedded at the heart of our missions.”Footnote20 In another Museum issue dedicated to education, this one two years later, in 2016, AAM President and CEO Laura Lott makes a nearly identical statement to Merritt’s and asks why museums are not top of mind for education reformers.Footnote21 But these observations are not just from museum leadership; museum educators, too, seem to recognize this odd need for justification. In a conversation inspired by the 40th anniversary of AAM’s Education Committee (EdCom), Sarah Jesse, then chair of EdCom, asked colleagues, “So have we arrived? Or is there more that we need to do to continue to shine a light on the vital role of education within museums?”Footnote22 The question is answered, “I don’t want to say we’ve arrived, because on one level I don’t think we ever will have arrived.”Footnote23 We will return to this education justification disconnect later.

Museum education amidst the pandemic

Considering pre-pandemic trends, logic would suggest that museum educators would be in a relatively safe zone given the recognized role of educators and education departments in fulfilling the public-facing aspects of museums’ missions and charges to be inclusive and relevant. However, museum leaderships’ decision making during the COVID-19 pandemic feels like a major setback to museum education and museums in general. We have triangulated data from three sources to examine this observation further:

Survey of Museum Education Roundtable Members and Journal of Museum Education readers (Summer 2020)Footnote24

Survey of Art Museum Educators by the authors for the National Art Education Association’s Museum Education Division (Fall 2020)Footnote25

Survey of Museum Directors by the American Alliance of Museums with Wilkening Consulting (Fall 2020)Footnote26

These data sources document what happened in the first six to nine months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Key takeaways, which are intertwining issues, are as follows.

Disruptions in employment

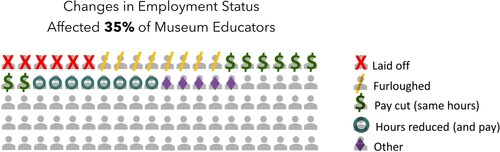

As noted earlier, the news of cuts in contract education staff at MoMA was a canary in the coal mine indicating that the loss of museum educators may be a fallout of the pandemic carrying long-term consequences for the field of museum education and the integrity of museums. More than one-third of museum educators reported a change in employment status resulting from the pandemic.Footnote27 Changes in employment status included layoffs, furloughs, pay cuts, reduced hours, the removal of benefits, pay freezes, and changes in position (see ).Footnote28

Figure 1. Infographic showing percent of museum educators who experienced changes in their employment status.

We looked further at the data to see which specific types of museum educators experienced these employment status changes. Those (art) museum educators working in private, non-profit museums were more likely to experience changes in employment status than their colleagues in all other types of museums (e.g. federal, state, local, and university museums).Footnote29 Also, (art) museum educators who work with K-12 programs, family programs, and teen programs were more likely to experience changes in employment status than their colleagues working in other educational areas (e.g. division heads, docent coordinators, adult programs, and public programs).Footnote30 Museum educators’ years of experience also factored into how their employment status changed. Those who have 5–14 years of experience in the field were least likely to have their employment status affected.Footnote31 Furloughs were highest among museum educators with 4 years of experience or less.Footnote32 By comparison, pay cuts were highest among those museum educators with 15 years of experience or more.Footnote33 There were no discernable trends in which (art) museum educators were most likely to be laid off.Footnote34

Given the charge of museums to make significant steps towards being more inclusive, both in their public-facing work and internally among staff, we wondered whether museum educators who identify as Black, Indigenous, or People of Color (BIPOC) were more adversely affected than their White colleagues. Museum education departments and survey respondents remain predominantly White so inferential statistical analysis is not possible.Footnote35 breaks down the racial identity of (art) museum educators surveyed compared with their employment status.Footnote36 We have reported the number of individuals per employment status category, as well as the percent of their racial group to allow for comparisons. Again, museum educators are predominantly White, so the number of individuals in the other racial categories becomes quite small, meaning the percent, while helpful for comparison, can be misleading. Yet, scanning the table, we observe a few curiosities about the data.

Table 1. Table of employment status by race showing greater effects on some BIPOC groups.

First, it seems Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish (art) museum educators were affected most greatly by layoffs (the two laid off worked in a museum in the Western region, are female, 35–44 years, have 15 years of experience or more, and one was part-time and one a full-time employee). Second, those who identified themselves as “another race or ethnicity” from the list provided experienced the third greatest employment status changes. As researchers, we cannot ethically recategorize these individuals into the other groups, but we might assume these individuals identify as BIPOC. Third, those who did not identify their race were among those most affected by furloughs. We cannot assume that these individuals are BIPOC or not.

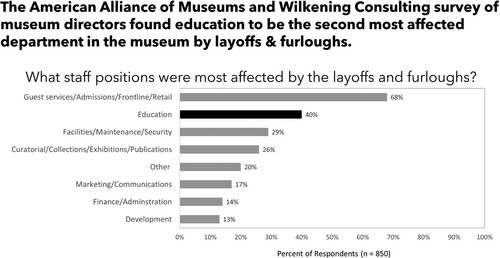

We recognize the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on museums – thinking about all the people who help a museum operate. Furthermore, we appreciate that museum leaders had to make difficult decisions during this crisis about staffing. Yet, the loss of museum educators as compared to the loss of staff in other departments is evidence of a very concerning pattern. A survey of museum educators by the American Alliance of Museums and Wilkening Consulting clearly indicates that education departments experienced more layoffs and furloughs than all other departments with exception of Visitor Services (see ).Footnote37 To problematize this data a bit, consider that the question asked about “staff” positions. Anecdotally, there are many additional colleagues supporting education departments that are in contract positions. Further, the survey collapses the category of curatorial with collections, exhibitions, and publications. If curatorial was considered its own category, we wonder what the comparison might look like.

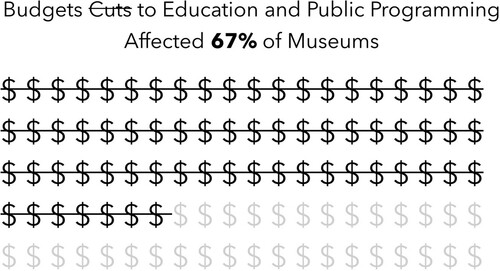

Figure 2. Infographic showing percent of museums that experienced budget cuts in education and public programming.

Budget cuts

A staggering 67% of museum directors cut back on education, programming, and other public service due to budget shortfalls and/or staff reductions in 2020 (see ).Footnote38 Keep in mind that the phrasing of the question asked is specific to cuts due to “budget shortfalls and/or staff reductions.” That is, these are not just cuts because the public services that were planned could not be rendered due to closure and social distancing measures. As with data on employment status, we found private non-profits to be less stable than other types of museums (e.g. federal, state, local, and university museums) – meaning they were more likely to make budget cuts.Footnote39 Again, we appreciate the difficult decision-making museum leaders faced. Museum directors reported losing 35% of their 2020 operating budget, and they anticipated losing 28% of their operating budget for 2021.Footnote40 Yet, cuts of such pervasiveness to education and public programming because of shortfalls is a troubling decision. We do not have data to compare how other services and operations of the museum were affected due to budget shortfalls. Nevertheless, the significant cuts to the public-facing work of the museum are likely to erode trust within communities, a point upon which we expand later in this article.

Figure 3. Horizontal bar graph showing museum staff positions most affected by layoffs and furloughs.

Effects on mental health and well-being of museum educators

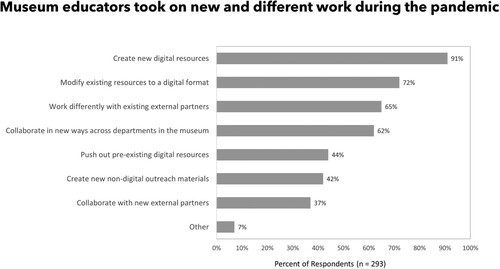

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a clinically documented effect on the general public, with reports of depression, stress, and anxiety emerging even among those who previously had not had mental health symptoms.Footnote41 Like the general public, museum educators have also been experiencing stress that is taxing to their mental health and well-being. When asked about the most pressing concern faced in their work during the pandemic, nearly one-half of (art) museum educators mentioned increased workloads and stress.Footnote42 With reductions in staff in education departments, remaining museum educators were required to take on additional and new ways of working amidst the pandemic. As shown in , approximately two-thirds of museum educators reported taking on new work, such as creating new digital resources, modifying existing resources, working differently with external partners, and collaborating in new ways across the museum.Footnote43 Further, our survey found that with the transition to remote work, only half of (art) museum educators were provided the technological equipment needed to create the virtual programming they want (and are asked) to produce.Footnote44

Figure 4. Horizontal bar graph showing new and different roles museum educators took on in the pandemic.

So, while asked to take on more responsibilities and in new ways, museum educators were not provided adequate equipment to do so.

Moreover, as a relationship-oriented department, museum educators bore additional emotional weight. Survey data show that (art) museum educators were very concerned for the safety of visitors, other museum staff, docents, and volunteers during the pandemic.Footnote45 And a survey fielded by Museum Education Roundtable found that the number one concern among museum educators during the pandemic is advancing anti-racism efforts and supporting DEAI.Footnote46 Working within one of the departments most committed to public-facing DEAI efforts, educators experienced emotional turmoil during the country’s racial reckoning that began after the murder of George Floyd and many other Black Americans. The effect of the pandemic on BIPOC museum educators was even greater. As one art museum educator shared in our survey: “As a Black woman, I wish my supervisors understood the turmoil of my mental health during the pandemic and uprisings. No one takes into consideration the staff’s well-being. It’s all about work and constantly pushing/creating events.”Footnote47

Looking to the future

Taken all together, these data signal to us that education in museums is in a much more vulnerable position than it was before the pandemic. A February 2020 survey of (art) museum directors showed that directors prioritized educational programming above everything else (followed closely by displaying artwork in the permanent collection).Footnote48 Yet, as we have seen, education was among the greatest casualties of pandemic-related staffing and budget cuts. How do we reconcile this dramatic difference in stated priorities and reality?

Our conclusion is that the pandemic revealed that education is not truly prioritized in museums. The job losses and budget cuts contradict where many of us believed education sat in the power hierarchy of museums and are concerning to say the least. The fact that education was more negatively affected than almost all other departments suggests a return to the “uncertain profession.” While the “uncertain profession” label irks us, it has seemed to be a mantle that educators still shoulder. Going back to a conversation among museum educators from 2014, the facilitator references the label of the “uncertain profession” and asks for adjectives to describe museum educators today; the words emboldened, confident, intentional, and unbounded rose to the top.Footnote49 However, certain was not among the adjectives.

This lack of certainty surrounding museum education has potentially grave implications in our mind. Now under-staffed and under-resourced education departments may lead to further losses post-pandemic. We are concerned about detrimental effects on the professionalization of the field overall, including “brain drain,” losing strides in leadership, and erosion of inroads made over decades of work in gaining respect, authority, influence, leadership, and resources. This would have negative effects on the profession of museum education’s ability to attract new, diverse, highly qualified individuals into the field as well as to retain existing museum educators, given tenuous job security and uncertainty.

A more far-reaching and insidious potential implication has to do with losses of audiences and communities due to reduction in the educational role of museums. Layoffs in education staff, especially as compared to other departments in museums, concern us because educators are frequently the name and face of the museum to local communities. Many museum educators find themselves working outside their museums often for relationship building, be it with schools, community organizations, or other external partners. In this regard, museum educators’ work is relational and, thus, it cannot be transactionally passed over to other individuals so easily when a museum educator leaves an institution. By cutting education staff, museums are physically removing the names and faces that community members know. Additionally, reducing budgets for public services is a recipe for eroding trust among the public, which results in particularly bad optics for museums that are trying to be responsive to DEAI calls to action.

Lastly, and of no small significance, we worry about the mental health and well-being of our museum education colleagues. We have concerns about burn-out among museum education professionals due to the heavy emotional lifting their jobs entail. These effects are being seen in many public-facing roles, such as in healthcare workers and K-12 teachers. We personally know museum educators who decided to leave the field, and there is a growing record of exits through personal testimonials.Footnote50 Some were laid off and decided they would not return to the museum field, seeking more empathetic working environments. Fortunately, or unfortunately, we hear, from folks who left the museum field, that the pastures are greener on the other side. This should worry museum leaders and make them consider how to support museum educators more holistically going forward.

As noted earlier in this article, the data we share is just from a moment in time in 2020. This article does not reconcile where museums and museum education stand today in our 2021 world. Our immediate thoughts on the implications shared above are quite dire. Yet, potentially more important are the questions raised in analyzing these data. Why is there a continued need to justify the educational role of museums? Why is there a continued need to justify museum education departments? What does it mean for a museum to cut funding to a department dedicated to education when the whole museum’s mission revolves around education?

Acknowledgements

This article was bolstered by the contributions of many. First, we want to recognize Juline Chevalier and Gwen Fernandez for their assistance with the qualitative analysis of the open-ended question responses on the RK&A survey of art museum educators. Thanks also to the National Art Education Association Museum Education Division leaders for their inputs in helping us design a survey responsive to their needs. Further, thanks to Gwen Fernandez and Amanda Thompson Rundahl for early edits that helped us shape this article and find our voice. Lastly, thank you to our blind peer reviewer, whose questions challenged us to clarify, and thus better, the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amanda Krantz

Amanda Krantz is Director of Research & Practice at RK&A.

Stephanie Downey

Stephanie Downey is Director & Owner of RK&A.

Notes

1 Di Liscia, “MoMA Terminates All Museum Educator Contracts.”

2 The authors each took to blogging in the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic to advocate for museum education. Stephanie wrote about the importance of maintaining school and museum partnerships, see Downey, “How Can Museums & Schools Continue Their Relationship During & After COVID-19?” Amanda wrote about her concerns that layoffs of museum educators will cut ties between museums and local communities, see Krantz, “Caution: Laying Off Museum Educators.”

3 Anderson, “Introduction: Reinventing the Museum.”

4 Kletchka, “Art Museum Educators: Who Are They Now.”

5 Eisner and Dobbs, The Uncertain Profession.

6 Specifically, Judith White Marcellini found resonance in the assessment and the ensuing discussions after panel discussions suggested resonance among other educators as well, see Stapp, “The Uncertain Profession,” 6, 9–10. And, Danielle Rice describes some of the structural inequalities that exist between curators and educators, see Stapp, “The Uncertain Profession,” 8–9. In another article, David Ebitz describes how these common perceptions have challenged the professionalization of museum education, see Ebitz, “Sufficient Foundation: Theory in the Practice.”

7 Ebitz, “Qualifications and the Professional Preparation and Development.”

8 American Association of Museums, Excellence and Equity: Education and the Public Dimension.

9 Weil, “From Being About Something to for Somebody.”

10 Simon, The Art of Relevance.

11 Woodruff and Davenport, “Lonnie Bunch on How the Smithsonian Can Help America.”

12 Villeneuve and Love, Visitor-Centered Exhibitions and Edu-Curation, ix–xii.

13 We follow the definition of Diversity Equity Access and Inclusion (DEAI) presented by Garibay and Olson in CCLI National Landscape Study: The State of DEAI Practices in Museums. Garibay and Olson define DEAI as,

Diversity: The ways in which human beings are similar and different, including but not limited to identities, social positions, lived experiences, values, and belief. Equity: Fair access to resources that advances social justice by allowing for full participation in society and self-determination in meeting fundamental needs. This requires addressing structural and historical barriers and systems of oppression. Accessibility: Ensuring equitable access to everyone along the continuum of human ability and experience. Inclusion: A culture that creates an environment of involvement, respect, and connection in which the richness of diverse ideas, backgrounds, and perspectives is valued.

14 Lott, “Museums and Racial Equality.”

15 Garibay and Olson, CCLI National Landscape Study.

16 Stevens, “Excellence and Equity at 25.”

17 “MASS Action: Museum as Site for Social Action.”

18 “Viewfinder: Reflecting on Museum Education.”

19 Garibay and Olson, CCLI National Landscape Study.

20 Merritt, “The Education Forecast.” The quote appears on page 27 following the comment, “You’d think, given these stats, people would consider museum as kin to schools, colleges and universities.”

21 Lott, “Museums are Key to Education Reform.”

22 Jesse et al., “The Museum Educator Revolution.”

23 For editorial authenticity, Ann Fortescue’s response continued: “Over the past 30 years, there has been both an internal and external shift that’s affecting museums and educators. Museum experiences are profound, impactful, and they make a significant difference to the individuals who visit us. We don’t always know what that impact is, but when we do, we shine the light on that, and on the data that supports that. The position of museum education will change as our knowledge base changes … ” We encourage you to read the entire conversation. Jesse et al., “The Museum Educator Revolution.”

24 Museum Education Roundtable, Survey of Members and Readers.

25 RK&A, “The Effects of COVID-19 on Art Museum Educators.”

26 American Alliance of Museums and Wilkening Consulting, National Snapshot of COVID-19 Impact on United States Museums.

27 Of those surveyed for NAEA Museum Education division, 34% of art museum educators experienced a change in employment status by 6 months into the pandemic. An earlier survey of the Museum Education Roundtable reported that 27% of museum educators experienced a change in employment status. We attribute the differences in percent to the earlier timing of the MER survey rather than to differences between art museum educators and a broader sample of museum educators. See RK&A, “The Effects of COVID-19 on Art Museum Educators” and Museum Education Roundtable, Survey of Members and Readers.

28 RK&A, “The Effects of COVID-19 on Art Museum Educators.”

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid.

35 Museum Education Roundtable, Survey of Members and Readers.

36 RK&A, “The Effects of COVID-19 on Art Museum Educators.”

37 American Alliance of Museums and Wilkening Consulting, National Snapshot of COVID-19 Impact on United States Museums.

38 Ibid.

39 RK&A, “The Effects of COVID-19 on Art Museum Educators.”

40 American Alliance of Museums and Wilkening Consulting, National Snapshot of COVID-19 Impact on United States Museums.

41 Khan et al., “The Mental Health Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic Across Different Cohorts.”

42 RK&A, “The Effects of COVID-19 on Art Museum Educators.”

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Ibid.

46 Museum Education Roundtable, Survey of Members and Readers.

47 RK&A, “The Effects of COVID-19 on Art Museum Educators.”

48 Sweeney and Frederick, Ithaka S + R Art Museum Director Survey 2020.

49 Jesse et al., “The Museum Educator Revolution.”

50 Kai Monet, “Honoring My Momentum of Change: Leaving Museums Behind.”

Bibliography

- American Alliance of Museums, and Wilkening Consulting. National Snapshot of COVID-19 Impact on United States Museums. Arlington, VA: American Alliance of Museums, 2020. Accessed December 1, 2020. https://www.aam-us.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/AAMCOVID-19SnapshotSurvey-1.pdf.

- American Association of Museums. Excellence and Equity: Education and the Public Dimension of Museums. Washington, DC: American Association of Museums, 1992.

- Anderson, Gail. “Introduction: Reinventing the Museum.” In Reinventing the Museum: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on the Paradigm Shift, edited by Gail Anderson, 1–7. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2004.

- Di Liscia, Valentina. “MoMA Terminates All Museum Educator Contracts.” Hyperallergic, April 3, 2020. https://hyperallergic.com/551571/moma-educator-contracts/.

- Downey, Stephanie. “How Can Museums & Schools Continue Their Relationship During & After COVID-19?” Art Museum Teaching (Blog), April 27, 2020. https://artmuseumteaching.com/2020/04/27/museums-schools-covid-19/.

- Ebitz, David. “Qualifications and the Professional Preparation and Development of Art Museum Educators.” Studies in Art Education 46, no. 2 (2005): 150–169.

- Ebitz, David. “Sufficient Foundation: Theory in the Practice of Art Museum Education.” Visual Arts Research 34, no. 2 (2008): 14–24.

- Eisner, Elliot W., and Stephen M. Dobbs. The Uncertain Profession: Observations on the State of Museum Education in Twenty American Art Museums. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Center for Education in the Arts, 1986.

- Garibay, Cecilia, and Jeanne Marie Olson. CCLI National Landscape Study: The State of DEAI Practices in Museums. Washington, DC: Cultural Competence Learning Institute, 2020. https://www.informalscience.org/sites/default/files/CCLI_National_Landscape_Study-DEAI_Practices_in_Museums_2020.pdf.

- Jesse, Sarah, Ann Fortescue, Nathan Richie, and Marley Steele-Inama. “The Museum Educator Revolution.” Museum 93, no. 5 (2014): 32–39.

- Khan, Kiran Shafiq, Mohammed A. Mamun, Mark D. Griffiths, and Irfan Ullah. “The Mental Health Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic Across Different Cohorts.” International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction (July 9, 2020). https://link.springer.com/article/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00367-0.

- Kletchka, Dana Carlisle. “Art Museum Educators: Who Are They Now?” Curator 64, no. 1 (2021): 79–97.

- Krantz, Amanda. “Caution: Laying Off Museum Educators May Burn Bridges to the Communities Museums Serve.” RK&A Blog (Blog), June 24, 2020. https://rka-learnwithus.com/caution-laying-off-museum-educators-may-burn-bridges-to-the-communities-museums-serve/.

- Lott, Laura. “Museums are Key to Education Reform.” Museum 95, no. 5 (2016): 5.

- Lott, Laura. “Museums and Racial Equality.” Museum 100, no. 1 (2021): 5.

- “MASS Action: Museum as Site for Social Action.” MASS Action. Accessed August 15, 2021. https://www.museumaction.org/.

- Merritt, Elizabeth. “The Education Forecast.” Museum 93, no. 5 (2014): 26–31.

- Monet, Kai. “Honoring My Momentum of Change: Leaving Museums Behind.” Viewfinder: Reflecting on Museum Education, March 25, 2021. https://medium.com/viewfinder-reflecting-on-museum-education/honoring-my-momentum-of-change-leaving-museums-behind-65611561f3fb.

- Museum Education Roundtable. Survey of Members and Readers. Washington, DC: Museum Education Roundtable, 2020. http://www.museumedu.org/download/1573/.

- RK&A. “The Effects of COVID-19 on Art Museum Educators.” Presentation at the National Art Education Association’s Museum Education Division Peer2Peer Webchats, Alexandria, VA, December 10 and 14, 2020.

- Simon, Nina. The Art of Relevance. Santa Cruz, CA: Museum 2.0, 2016.

- Stapp, Carol. “The Uncertain Profession: Perceptions and Directions.” The Journal of Museum Education 12, no. 3 (1987): 4–10.

- Stevens, Greg. “Excellence and Equity at 25: Then, Now, Next.” Museum 96, no. 4 (2017): 16–21.

- Sweeney, Liam, and Jennifer K. Frederick. Ithaka S + R Art Museum Director Survey 2020. New York, NY: Ithaka S + R, 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.314362.

- “Viewfinder: Reflecting on Museum Education.” Viewfinder: Reflecting on Museum Education. August 15, 2021. https://medium.com/viewfinder-reflecting-on-museum-education.

- Villeneuve, Pat, and Anne Rowson Love, eds. Visitor-Centered Exhibitions and Edu-Curation in Art Museums. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2017.

- Weil, Stephen E. “From Being About Something to for Somebody.” In Making Museums Matter, 28–52. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2002.

- Woodruff, Judy, and Anne Azzi Davenport. “Lonnie Bunch on How the Smithsonian Can Help America Understand Its Identity.” PBS News Hour, July 18, 2019. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/lonnie-bunch-on-how-the-smithsonian-can-help-america-understand-its-identity.