ABSTRACT

Objectives

California’s agricultural industry, an “essential industry” during the COVID-19 pandemic, required support to understand and implement changing public health knowledge and regulations in the workplace. The Western Center for Agricultural Health and Safety (WCAHS) transitioned from traditional in-person trainings with agricultural stakeholders to remote engagement, such as webinars. We aimed to assess the use of real-time webinar trainings and identify agricultural employer concerns about reducing the risk of COVID-19 in the workplace.

Methods

We conducted a thematic analysis of webinar chat from WCAHS’ “Reduce the Risk of COVID-19 in Your Workplace” monthly webinar series held from December 2020–May 2021. De-identified chat transcripts were analyzed using a deductive approach to assess participant concerns as they related to prevention and response actions, employer responsibilities, and evolving public health knowledge. Codes were identified by an iterative process using semantic interpretation and summarized into four major themes.

Results

Our analysis reveals participants’ concerns relating to (1) prevention of COVID-19 in the workplace, (2) response to COVID-19 in the workplace, (3) employer concerns, and (4) evolving, real-time knowledge. Participants shared multiple, overlapping concerns. Many also asked for information tailored to specific scenarios in their workplace.

Conclusion

Providing industry-specific guidance and examples in an accessible means is critical for supporting agricultural employers and their highly vulnerable workers. Virtual trainings will likely continue to be an effective means of outreach with the agricultural industry. Future outreach and education efforts should consider virtual engagement and opportunities to document experiences amid changing work environments, social cultures, and learning activities.

Introduction

California has the largest agricultural industry in the nation, producing 13% of U.S. total commodities and earning an annual revenue of $50 billion.Citation1 The roughly 400,000–800,000 agricultural workers in California are considered “essential workers” by the State Public Health Officer during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, meaning agricultural workers continued operations in fields and packing houses during statewide “stay at home” orders.Citation2–5 Investigations in California have shown disproportionate impacts of the pandemic on farmworker communities. One study in the Salinas Valley, June–November 2020, observed a .COVID-19 prevalence of 22.1% in a sample of farmworkers compared to 17.2% in the general population.Citation6

Farmworkers in California are primarily Latino. Across the nation, Latinos experienced five to seven times greater risk of COVID-19 mortality relative to whites.Citation7,Citation8 Social and structural factors, such as crowded living conditions, lack of social distancing, and monolingual Spanish communities, are shown to contribute to this increased risk.Citation9 Occupational exposure may play a key role in COVID-19 transmission within Latino communities.Citation7,Citation10 Chicas et al.Citation10 surveyed agricultural workers in Florida and showed the majority of participants implemented personal COVID-19 prevention practices; however, employer-based prevention practices were lacking. Additionally, the COVID-19 Farmworker Study (COFS) studied impacts, risk disparities, and workplace prevention of COVID-19 through farmworker surveys and interviews in the western U.S.Citation11 COFS found workers experienced uneven workplace protections and communication, decreased work time resulting in reduced income, and persistent healthcare barriers. The study also documented vulnerabilities among Indigenous farmworkers beyond those faced by Spanish-speaking farmworkers.Citation12

In 2020, the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA) instructed agricultural employers to update their Injury and Illness Prevention Program to address the newly identified risk of COVID-19 and subsequently adopted Emergency Temporary Standards.Citation13,Citation14 Thus, agricultural employers had to learn how to implement new guidance and regulations during the pandemic, e.g., supplemental paid sick leave, quarantine procedures, testing, and vaccinations. Concurrently, the Western Center for Agricultural Health and Safety (WCAHS), a prominent, interdisciplinary research institute engaging with agricultural communities to promote health and safety and study workplace hazards, began COVID-19 education and outreach.Citation15

WCAHS worked with government agencies to implement monthly webinars titled “Reduce the Risk of COVID-19 in Your Workplace” in Spanish and English. These webinars provided education on infection control, updated guidance on state and local regulations, and an opportunity to troubleshoot industry needs for agricultural employers during a real-time pandemic response. Participants, including stakeholders across the agricultural industry, could ask questions of WCAHS staff and representatives from the California Labor Commissioner and Cal/OSHA through chat functions during the webinar.

WCAHS outreach and engagement activities are traditionally done in-person and within target communities, yet the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated use of remote, virtual environments.Citation15–17 Studies showed webinar series can be an effective method to communicate health and safety information during the pandemic.Citation18–20 Jepsen et al.Citation18 found webinars provided an important tool to assess occupational safety and health concerns, mental health, and social impacts of the pandemic on farmers and farmworkers. Prior to the pandemic, Wardynski et al.Citation21 evaluated the effectiveness of a webinar series for people interested in entering Michigan’s agricultural industry. The authors found webinar trainings helped accommodate participants traveling long distances to attend in-person meetings. Thus, this will likely continue to be an effective means of outreach with the agricultural industry.Citation22

Webinars provide a unique opportunity for hosts and panelists to engage with participants in a virtual environment. Meaningful textual data is documented via communication in the chat. Similar remote outreach and virtual engagement during the pandemic has been studied using thematic analysis.Citation23–25 This is a common qualitative method used to examine the implicit or explicit meanings within texts, such as dialogue from webinar chats, and allows researchers to assess information transfer, program objectives, or participant concerns by identifying patterns and major themes in textual data.Citation22,Citation26

Thus, we conducted a thematic analysis to examine webinar chats and summarize key comments from participants, including safety officers, supervisors, growers, and farm labor contractors. Specifically, we aimed to assess the use of real-time webinar trainings to identify agricultural employer concerns about reducing COVID-19 workplace risks. This study highlights the benefit of educational webinars to maintain support for essential industries and their high-risk workers.

Methods

Data collection

Participants for the WCAHS’ “Reduce the Risk of COVID-19 in Your Workplace” webinar series were recruited through announcements in Proximamente, the center’s bilingual training newsletter; promotion at WCAHS events (e.g., monthly seminar series, supervisor heat trainings); WCAHS’ website; and employer association partners’ newsletters. Webinars, roughly 1.5–2.5 hours, were conducted using Zoom with participant microphones disabled during the presentation portion. Participants could write in the chat throughout the webinar and responses from presenters were provided orally at the end during the Q&A feature. Starting in January, participants could also ask oral questions during Q&A; however, chat remained the primary means to question WCAHS staff, Cal/OSHA, and the California Labor Commissioner about webinar content.

Webinars in December 2020 and January 2021 were conducted in English and Spanish at separate times on the same day. However, subsequent monthly webinars (February–May 2021) were bilingual, i.e., presented in English with the option of live Spanish interpretation. This decision was made to promote diversity of participant engagement and a better understanding of different issues. Over time, webinar content was adapted based on current scientific knowledge and state/federal regulations and guidelines. Participants were permitted to attend all webinars in the series.

Transcripts of chat dialogue were obtained from the Zoom chat function, which records all messages sent during the session. Oral questions were recorded in real time by WCAHS staff. We included transcripts of written dialogue from eight webinars in our analysis; oral questions were excluded due to differences in data collection and accuracy of data. WCAHS staff provided de-identified transcripts with a random unique identifier for participants in each webinar. Spanish chat transcripts were translated to English by WCAHS staff prior to analysis.

Thematic analysis

A thematic analysis of webinar chat was conducted using a deductive approach.Citation22 Codes and themes were generated from participant chat to assess objectives of the webinar series – providing updates on emerging science related to COVID-19 and guidance on complying with legal requirements and ensuring worker safety – and to elucidate agricultural employer concerns.

De-identified transcripts were analyzed using hardcopies and Microsoft Excel. Codes were identified by an iterative process using semantic interpretation. As new codes were developed, the new structure was applied to all transcripts until saturation was reached. New questions continued to be raised as the public health response evolved, but by the last four webinars, comments fell within the coded topics previously identified. Themes were developed by aggregating codes as they related to each other and the overarching research aims.

A single researcher (CJ) reviewed and became familiar with the transcript data, developed codes, and compiled codes into themes. The research team, comprised of WCAHS staff implementing the webinar series (YRS, TA), and the Program Director (HR), then collaborated to discuss themes and ensure they accurately represented the data and the webinar series conversations. Appropriate names and definitions were developed to characterize each theme.

Pre- and post-webinar survey

Webinar participants were asked to complete a poll in Zoom prior to the presentation and a survey was sent via Zoom and email upon completion of the webinar. In the pre-webinar poll, participants self-reported occupation from a multiple choice and responded to Likert-type questions regarding knowledge and comfort with COVID-19 response in the workplace. The post-webinar survey asked the same Likert-type questions. In addition, open-ended questions for feedback were included in the post-webinar survey.

Questions in the pre- and post-webinar surveys were edited following the December sessions. All subsequent webinars, January–May 2021, asked the same set of questions, thus, response frequencies from these six sessions are summarized in aggregate to provide more context regarding the knowledge and comfort of participants. Responses to open-ended questions were not analyzed.

This study was approved for programmatic assessment and determined to be research not involving human subjects by the University of California, Davis Institutional Review Board (IRB) Administration; therefore, IRB review was not required.

Results

Participant characteristics

Over the course of the webinar series, participation in the webinars and chat varied. Participation and engagement are summarized in . The lowest monthly attendance occurred in April 2021 (N = 17, for bilingual webinar), while the highest was in December 2020 (N = 94, for English and Spanish webinars combined). Participants identified predominantly as safety officers (46.8%) and supervisors (25.2%), along with growers/farmers and farm labor contractors (14.4% and 13.7%, respectively).

Table 1. Summary of participation for the “Reduce the risk of COVID-19 in your workplace” webinar series, presented by the Western center for agricultural health and safety (WCAHS). Engagement in the chat shows the number of participants who submitted any text entry to the webinar chat. Distinct comments is the number of comments included in the analysis, excluding information from presenters and moderators and comments with identifiable information.

Thematic analysis

The thematic analysis revealed the following major themes in chat dialogue:

Prevention of COVID-19 in the workplace

Response to COVID-19 in the workplace

Employer concerns

Evolving, real-time knowledge

The following is a summary of the themes and coded topics used to define them.

Theme 1: prevention of COVID-19 in the workplace

The webinar introduced participants to key concepts of COVID-19 prevention including appropriate strategies to use in the workplace. Participants were introduced to the hierarchy of controls: elimination, substitution, engineering controls, administrative controls, and personal protective equipment (PPE; ), illustrating different levels available to reduce the risk of injury and illness in the workplace.Citation27 Participants were encouraged to start looking for solutions from the top (most protective), and identify policies to support safe use of PPE (least protective), as it does not eliminate the risk and depends on correct use.

Figure 1. Image from the Western center for agricultural health and safety’s “Reduce the risk of COVID-19 in your workplace” webinar. The image is used to convey the hierarchy of strategies for prevention and response to COVID-19 in the workplace.

In this context, participants asked about prevention of COVID-19 in the workplace. Participants were interested in COVID-19 testing availability (sites, cost, eligibility) and requirements, engineering controls, such as ventilation or safely distanced workstations, and guiding safe behaviors among employees in- and outside the workplace. Some participants explicitly asked about how to prevent COVID-19 outbreaks in their workplaces:

“What are some basic guidelines ag[riculture] employers should follow for daily evaluation of workers to keep COVID out of the workplace? Should temperature checks be included?” – December 9, 2020.

“How should we screen workers as they arrive to work to see if they are coming with COVID symptoms or signs – what should a foreman look for in workers and should results be documented every day?” – translated from Spanish, December 9, 2020.

Theme 2: response to COVID-19 in the workplace

Participants also discussed response actions to COVID-19 in the workplace, i.e., responding to an employee with a positive case or known exposure at work as opposed to a focus on preventing COVID-19 infections in the workplace. Employers were inquisitive about responsive strategies such as quarantining, safe management of an employee who tests positive, and working with public health workers on worksites. They asked about practical applications relating to their workplace and how they are responding to COVID-19 health and safety requirements.

Comments focused on compliance with new regulations and guidance, but also included concerns regarding implementation of response actions in the workplace. This primarily included questions about how to implement adaptive response, i.e., translating guidance to their specific work scenarios. For instance,

“What if there are potentially exposed workers, and the employer advises them to get tested for COVID, but for some reason some workers refuse to be tested. Can the employer exclude those workers from the workplace – could the employer take disciplinary action, including termination for refusal to comply with safe work practices?” – December 9, 2020 webinar.

Another concern commonly expressed in the context above included the communication of exposures to employees. When considering appropriate response actions to COVID-19 in the workplace, handling exposures was a main concern. Questions from participants included topics such as how to address varying literacy, what information to provide, and how to handle employees who do not take appropriate actions following an exposure.

“Sect. 3205 specifically requires employers to provide a WRITTEN notice to employees when there is a COVID case worker in their worksite. What if there are workers of limited literacy? How should employers address this issue?” – December 9, 2020 webinar.

Theme 3: employer concerns

Across both prevention and response, another theme emerged related to employer concerns. Through the chat, participants expressed many concerns, challenges, and needs they faced. Participants discussed the role of employers in multiple contexts, described by the following sub-themes: employer needs, employer responsibilities, extent or limit of employer prevention practices, and concerns about worker benefits and protections.

Sub-theme 3.1: employer needs

Participants discussed needs for information on COVID-19 and related public health guidance. This included requests for resources and questions on where to access resources. Specific resources that were requested include:

COVID-19 prevention checklist

Cal/OSHA inspection checklist

Cal/OSHA model COVID-19 prevention program in Spanish

Quarantine timeframes

Recording of the WCAHS informational webinar

Presentation slides from the WCAHS informational webinar

Hardcopies of materials for dissemination to field workers

In some instances, these resources existed and were immediately provided to participants. Other resources could be provided upon follow up after the webinar. However, some requests, such as the Cal/OSHA model COVID-19 prevention program in Spanish, needed to be developed. Participants also expressed that the content of the webinars themselves, i.e., the presentation slides and recordings, would be helpful reference material.

Sub-theme 3.2: employer responsibilities under the Cal/OSHA COVID-19 regulation

In the webinar chat, participants commented on concerns about health and safety requirements, employer liability, and how to implement public health guidance. For example,

“If you have an employee who depletes their sick time leave but medically will need longer than 3 days to recover, as an employer are you required to hold their spot or can you let them go with[out] the fear of them litigating and using retaliation as a [motive]” – March 19, 2021 webinar.

Many participants asked specific situational questions when they felt public health or occupational guidelines were conflicting or lacked clarity. Participants utilized the webinar chat to request tailored information and guidance for their workplace. For instance,

“[I]f an employee traveled outside of CA, to Mexico, and is returning – under the emergency order are we obligated to pay them COVID19 pay based on the CA Dept of Health requirement for quarantine?” – January 21, 2021.

This participant further stated they were confused about the employer’s obligations to follow state quarantine procedures when exposure is not work related and takes place outside the country. State and federal guidelines did not clearly address every possible exposure scenario or potential workplace risk of exposure. The webinar provided employers an opportunity to ask state representatives questions directly. Cal/OSHA and Labor Commissioner representatives participating in the webinar series were able to share feedback from the webinar with their respective agencies to inform future frequently asked question (FAQ) resources created by their units about state policies.

Sub-theme 3.3: extent of employer authority on prevention practices

Participants also asked questions relating to the extent of regulatory and management authority in and outside the workplace. There were multiple scenarios in which participants were uncertain about the limits of employer enforcement capabilities for workplace health and safety. The concern was typically discussed in the context of community, or non-workplace, COVID-19 spread. For instance,

“Can the employer punish workers if they arrive in shared transportation if the workers do not have a face covering on?” – translated from Spanish to English, December 9, 2020 webinar.

Several questions related to activities outside of the workplace that would affect health and safety in the workplace were asked. This also included questions about requirements for workers who may decline testing, quarantine, or vaccination.

“For people who work in the fields, can employers require that they get vaccinated?” – translated from Spanish to English, April 16, 2021 webinar.

Sub-theme 3.4: concerns about worker benefits and protections

Each of the preceding themes also tie into comments on workers’ benefits and protections. Participant questions focused on employee health and safety practices, e.g., testing, quarantine, and other required response actions, from the employers’ perspective.

A recurring topic across the webinar series was supplemental paid sick leave. As the webinars were conducted, state and federal laws for paid sick leave updated in real-time. The evolution of information over time prompted additional questions and potential confusion about the most current provisions and guidelines. For example,

“Any chance of the 80 hours supplemental paid sick leave being extended? Or anything else like that available now/for this year? Also, if employer requires the workers to get vaccinated & they get sick for 1–3 days, do[es] the employer still pay for their days off? Is there any sort of law about that?” – March 19, 2021 webinar.

Theme 4: evolving real-time knowledge

The webinars were held monthly during a period of frequent scientific and policy change. Questions posed during webinars reflected the changing pandemic environment.

“With things changing almost on a daily basis, how can I determine the exact amount of days an employee should quarantine for, should he/she test positive?” – December 9, 2020 webinar.

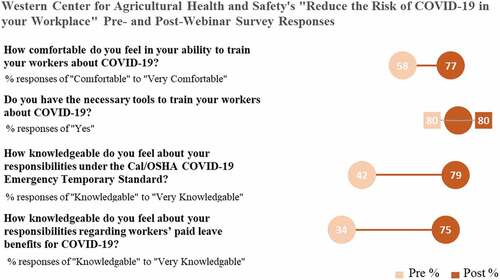

Information on COVID-19 continued to evolve as the webinars were conducted from December 2020–May 2021. New laws, guidelines, and mitigation strategies were developed over the course of the series, as shown in . Prominent changes included new federal and state paid sick leave laws, the California “stay at home” order, and the implementation of COVID-19 vaccinations. Agricultural workers were part of California’s phase 1B during the vaccination rollout, which allowed many to begin receiving vaccines in January/February 2021.

Figure 2. Timeline of COVID-19 response actions in California and the Western center for agricultural health and safety (WCAHS) “Reduce the risk of COVID-19 in your workplace” webinar series.

The evolving public health response was also apparent in the types of questions asked across the webinar series. For instance, questions about vaccines contrast from availability to possible side effects during webinars before and after vaccines were accessible.

“When vaccines are available and employees get the vaccine, will they be obligated to show this to the employers?” – December 9, 2020 webinar.

“[W]ho is experiencing COVID vaccine side affects [sic]?” – May 21, 2021 webinar.

While both were seeking information about the vaccine, the context shifted across the webinar series for these types of questions as public health information and response actions progressed.

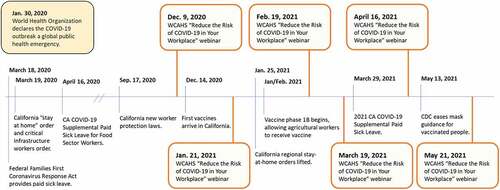

Pre- and post-webinar survey

Response data from pre- and post-webinar surveys provide a simple examination of the impacts of webinars on knowledge and comfort within the topic areas. Results showed changes in the percentage of participants responding positively, i.e., “comfortable” to “very comfortable” or “knowledgeable” to “very knowledgeable” (). There was an increase in comfort and knowledge in three of the four questions from pre- to post-webinar with no change for the question about the availability of necessary tools to train workers (80% pre- and post-webinar). Responses to pre- and post-webinar surveys are not matched by participant; thus, interpretations of these results are limited.

Figure 3. Western center for agricultural health and safety’s (WCAHS) “Reduce the risk of COVID-19 in your workplace” Pre- and post-webinar survey responses. The chart shows the degree of change in percent of favorable responses, indicated below each question, for pre- and post-webinar survey results across the webinar series. Questions included Likert-type responses on comfort and knowledge, as well as a yes/no response.

Discussion

As the pandemic response, public health knowledge, and regulatory requirements changed over the course of the webinar series, our analysis conveys the evolving nature of real-time, remote training activities. We identify multiple, overlapping, and evolving concerns webinar participants faced over the six-month period within the four major themes. Participants’ questions and comments during the series offer a unique perspective on concerns they faced, namely, how to prevent COVID-19 spread at the worksite, how to implement administrative controls related to screening and testing, employer responsibilities, and workers’ benefits.

Throughout the webinar series, ongoing participation suggested a continued demand on the part of agricultural employers to remain abreast of changes and obtain new resources. The COVID-19 pandemic placed additional burdens on California’s agricultural industry to maintain active operations while providing a safe workplace for highly vulnerable workers.Citation28 The major themes in our analysis provide critical information on specific communication, information, and response needs within the agricultural industry. Participants were interested in how to maintain an adaptive response and integrate new information to the circumstances of their workplace.

Many questions sought to clarify employers’ authority and the allowable questions and/or requirements employers may make of their employees. Participants frequently framed questions using scenarios from their workplace, including a common concern, the potential for COVID-19 spread and transmission outside of the workplace. Some participants also stated confusion about conflicting information, guidelines, and requirements from state and federal agencies. Clarifying questions pertained not only to differences or inconsistencies between agencies, but also rapidly changing information published by the same agency.

Documenting experiences of workers amidst changing work environments, social cultures, and learning activities with thematic analysis of webinar chat has also been done for virtual trainings in another essential industry, education and medicine.Citation23 These findings, and our own, indicate online training can be an effective method to provide rapid occupational health and safety information to essential industries. It was critical to provide accessible, real-time information to agricultural employers.

WCAHS educational programs are traditionally conducted in-person; however, circumstances dictated this educational program be remote. Many other institutions working with the agricultural industry were forced to transition from in-person outreach to virtual platforms for outreach and engagement, too.Citation18–20,Citation29 The virtual environment enabled us to reach a greater audience without the geographic and time constraints of in-person events. It also enabled live interpretation to provide the same content in English and Spanish, improving interaction between languages without the need for individual listening devices used in-person.

In our study, the webinar series engaged agricultural stakeholders who have deep experience in the operations of California’s agricultural industry and thus, our webinars provided practical and industry-tailored information on COVID-19 prevention in their workplace. The importance of industry-specific guidance and examples was evident within each major theme. For example, a participant asked about engineering controls to abide by distancing requirements for bunk beds in employee provided housing. Another participant asked how to provide written notices to workers with limited literacy. Both topics touch on unique risks in the agricultural industry relating to employer concerns and prevention and response of COVID-19. A critical component of the webinars was to make public health concepts, regulatory guidance, and legal content clear and accessible for agricultural stakeholders. Imagery and scenarios were used to illustrate how prevention practices could be implemented in different production settings.

Webinars also featured multiple speakers who presented on and could respond to questions across a range of topics, from COVID-19 facts to occupational safety requirements and labor laws addressing workers’ benefits, such as supplemental paid sick leave. The combination of expertise from WCAHS, Cal/OSHA, and the California Labor Commissioner provided comprehensive and practical solutions to participants. In the face of seemingly conflicting information from different sources, our analysis conveys participants valued hearing from agency representatives to learn definitively current rules and requirements.

Strategies identified during the webinar series were implemented in an ongoing manner and provide insight for future online training events. Event promotion should highlight the current concerns and most recent updates and the training content must similarly be up to date. Webinar participants sought deeper information than was readily available online and wanted to understand how guidelines could be implemented in their real-world situation. We also found offering live interpretation, rather than separate English and Spanish trainings, ensured all participants received the same content. In the future, we may consider alternating the primary and secondary languages of webinars to further accessibility equity.

Limitations

The webinar series was not conducted with the intention of formal evaluation, but rather as a rapid response to address critical needs in the agricultural industry. Thematic analysis provides insights into real-world experiences of the participants; however, we cannot confirm the accurate representation of participant chat. Chat dialogue was anonymized and provided no information on participant characteristics. Uncertainties regarding participation also limit our interpretation of survey results. It is unclear to what degree participants attended multiple webinars and we were unable to match pre- and post-survey response data by participant.

Conclusions

Engaging with agricultural employers through a webinar series provides beneficial support and education to an essential industry. We provide novel information on the concerns of agricultural employers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Future webinars, training opportunities, or other engagement should continue to capture the thoughts and concerns of employers while remaining adaptive to the ongoing public health emergency. It is critical to maintain support for these essential industries as well as their high-risk workers.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Elizabeth Georgian, Ph.D., University of California, Davis, for her editorial work on this manuscript. We greatly appreciate all staff from the Western Center for Agricultural Health and Safety for their involvement in the webinar series and contributions of contextual knowledge. Nelly Chávez, JD, MILR, University of California, Davis, assisted us with translating chat transcripts from Spanish to English. We would also like to acknowledge all the participants of the webinar series for their engagement. We are especially thankful to the involvement and expertise of Michael Alvarez, representative of California Division of Occupational Safety and Health, as well as Rick Mejia, Nicholas Seitz, Armida Abaoag, and Celina Damian, representatives of the California Labor Commissioner, in the webinar series.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- California Department of Food and Agriculture. California Agricultural Statistics Review 2019-2020. Sacramento, California: California Department of Food and Agriculture; 2020. Accessed 5 May 2022.

- Martin P, Hooker B, Akhtar M, et al. How many workers are employed in California agriculture? Calif Agric. 2016;71(1): 30–34.

- Occupational Employment Statistics and Wages. [Internet]. Employ. Dev. Dep. Accessed June 9, 2021, https://www.labormarketinfo.edd.ca.gov/data/oes-employment-and-wages.html.

- State of California. Executive order N-33-20 [Internet]. 2020. https://covid19.ca.gov/img/Executive-Order-N-33-20.pdf.

- California State Government. Essential workforce. [Internet]. 2022 Accessed May 5, 2022, Available from: https://covid19.ca.gov/essential-workforce/#:~:text=Workers such as plumbers%2C electricians,any facility supporting COVID19 such as plumbers%2C electricians,any facility supporting COVID19

- Lewnard JA, Mora AM, Nkwocha O, et al. Prevalence and clinical profile of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection among farmworkers. Emerg Infect Dis. [Internet]. 2021;27:1330–1342. California, USA, June–November 2020, https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/27/5/20-4949_article.htm

- Sáenz R, Garcia MA. The Disproportionate Impact of COVID-19 on Older Latino Mortality: The Rapidly Diminishing Latino Paradox. Journals Gerontol Ser B [Internet] 2021;76(3):e81–e87. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbaa158.

- Bassett MT, Chen JT, Krieger N. The unequal toll of COVID-19 mortality by age in the United States: quantifying racial/ethnic disparities. Harv Cent Popul Dev Stud Work Pap Ser. 2020:19.

- Rodriguez-Diaz CE, Guilamo-Ramos V, Mena L, et al. Risk for COVID-19 infection and death among Latinos in the United States: examining heterogeneity in transmission dynamics. Ann Epidemiol. [Internet]. 2020;52:46–53.e2. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1047279720302672

- Chicas R, Xiuhtecutli N, Houser M, et al. COVID-19 and agricultural workers: a descriptive study. J Immigr Minor Heal. [Internet]. 2021; https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10903-021-01290-9

- Ramirez SM, Mines R, Carlisle-Cummins I. COFS phase one report [Internet]. Santa Cruz. 2021. https://cirsinc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/CA-COFS-Phase-One-Final-Report.pdf

- Binational Center for Indigenous Oaxacan Community Development, Vista community clinic/FarmWorker CARE coalition, California institute for rural studies, Experts in their Fields: Contributions and Realities of Indigenous Campesinos in California during COVID-19. 2021; www.covid19farmworkerstudy.org.

- State of California. California code of regulations, title 8, section 3203. Injury and Illness Prevention Program. [Internet] 3203 United States: 2021. https://www.dir.ca.gov/title8/3203.html

- State of California. California code of regulations, title 8, Section 3205. COVID-19 prevention. [Internet]. United States; 2021. https://www.dir.ca.gov/title8/3205.html

- Riden HE, Schilli K, Pinkerton KE. Rapid response to COVID-19 in agriculture: a model for future crises. J Agromedicine. 2020;25:392–395. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2020.1815618.

- Ramos AK, Duysen E, Carvajal-Suarez M, et al. Virtual outreach: using social media to reach Spanish-speaking agricultural workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Agromedicine. [Internet]. 2020;25:353–356. DOI:10.1080/1059924X.2020.1814919.

- Mohalik R, Poddar S Effectiveness of webinars and online workshops during the COVID-19 pandemic. SSRN Electron J [Internet]. 2020. https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3691590.

- Jepsen SD, Pfeifer L, Garcia LG, et al. Lean on your land grant: one university’s approach to address the food supply chain workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Agromedicine. [Internet]. 2020;25(4):417–422. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2020.1815623.

- Bamka W, Komar S, Melendez M, et al. “ Ask the Ag agent” Weekly webinar series: agriculture-focused response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Ext. 2020;58:v58–4tt2.

- Dudley MJ. Reaching invisible and unprotected workers on farms during the coronavirus pandemic. J Agromedicine. 2020;25:427–429. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2020.1815625.

- Wardynski FA, Isleib JD, Eschbach CL. Evaluating impacts of five years of beginning farmer webinar training. J Ext 2018;56(6):9.

- Creswell JW, Hanson WE, Clark Plano VL, et al. Qualitative research designs: selection and implementation. Couns Psychol. 2007;35:236–264. doi:10.1177/0011000006287390.

- Cleland J, McKimm J, Fuller R, et al. Adapting to the impact of COVID-19: sharing stories, sharing practice. Med Teach. [Internet]. 2020;42:772–775. DOI:10.1080/0142159X.2020.1757635.

- Chivers BR, Garad RM, Boyle JA, et al. Perinatal distress during COVID-19: thematic analysis of an online parenting forum. J Med Internet Res. [Internet]. 2020;22(9):e22002. http://www.jmir.org/2020/9/e22002/

- Rao SPN, Minckas N, Medvedev MM, et al. Small and sick newborn care during the COVID-19 pandemic: global survey and thematic analysis of healthcare providers’ voices and experiences. BMJ Glob Heal. 2021;6:1–11.

- Riessman CK. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 2008.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Recommended Practices for Safety and Health Programs. [Internet]. 2016 Accessed November 17, 2021, https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/OSHA3885.pdf

- Beatty T, Hill A, Martin P, et al. COVID-19 and farm workers: challenges facing California agriculture. Univ Calif Giannini Found Agric Econ [Internet]. 2020;23:2–4. https://www.doleta.gov/naws/research/data-tables/

- Rohlman DS, Campo S, TePoel M. Protecting young agricultural workers: the development of an online supervisor training. J Agromedicine. [Internet]. 2021;1–9. DOI:10.1080/1059924X.2021.1979155.