ABSTRACT

Objectives

In this paper, we use a UK case study to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the mental health (emotional, psychological, social wellbeing) of farmers. We outline the drivers of poor farming mental health, the manifold impacts of the pandemic at a time of policy and environmental change, and identify lessons that can be learned to develop resilience in farming communities against future shocks.

Methods

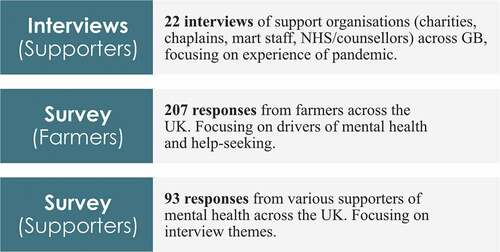

We undertook a survey answered by 207 farmers across the UK, focusing on drivers of poor mental health and the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. We also conducted 22 in-depth interviews with individuals in England, Scotland and Wales who provide mental health support to farmers. These explored how and why the COVID-19 pandemic affected the mental health of farmers. These interviews were supplemented by 93 survey responses from a similar group of support providers (UK-wide).

Results

We found that the pandemic exacerbated underlying drivers of poor mental health and wellbeing in farming communities. 67% of farmers surveyed reported feeling more stressed, 63% felt more anxious, 38% felt more depressed, and 12% felt more suicidal. The primary drivers of poor mental health identified by farmers during the pandemic included decreased social contact and loneliness, issues with the general public on private land, and moving online for social events. Support providers also highlighted relationship and financial issues, illness, and government inspections as drivers of poor mental health. Some farmers, conversely, outlined positive impacts of the pandemic.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic is just one of many potential stressors associated with poor farming mental health and its impacts are likely to be long-lasting and delayed. Multiple stressors affecting farmers at the same time can create a tipping point. Therefore, there is a need for long-term support and ongoing evaluation of the drivers of poor mental health in farming families.

Introduction

Farmers are essential workers providing citizens with the food they need, along with a range of other goods and services including environmental management, access to nature, and maintenance of cultural and social heritage. Farmers have often been relatively isolated, physically, socially, and culturallyCitation1 and it is evident that there is low mental health among farmers globally.Citation2–10 Social isolation and potential loneliness which may result from it are linked to a number of mental health issues in the farming community, such as stress, depression and anxiety,Citation11 and stem from a range of drivers including location, changes in public and consumer perception, and lone working conditions.

A recent survey in England and Wales suggested that 36% of the farming community were probably or possibly depressed.Citation12 Comparing this figure with other occupational sectors is challenging as evaluation of occupational health across all sectors differs depending upon the occupation and few will have a sample size as large as the cited study. However, with regards to employment status overall, it is estimated that approximately 14%-16% of those employed full-time or part-time have reported experiencing a common mental disorder (CMD), of which depression is one.Citation13

There is a wide range of drivers affecting the mental health and wellbeing of farmers and each are inter-dependent. Factors affecting farming mental health (seeCitation14) can be split into a number of categories, including personal/social reasons (sexuality, personal relationships, illness, loneliness, isolation), farm enterprise-related issues (weather, climate change, crop/animal diseases, financial problems, farm accidents, lack of succession, tenancy issues), policy-related concerns (paperwork, inspections, uncertain government policy), and problems with members of the public/media (rural crime, online or media criticism).

Agriculture is a key sector of the UK economy, with utilised agricultural area comprising 71% of total UK land area. Of the 17.2 million hectares of this total agricultural area, the main land uses see 6.1 million hectares used for crops (e.g. cereals, oilseeds, potatoes, horticultural and other crops) with 10 million hectares of permanent grassland (dairy, upland and lowland livestock production) and 1.2 million hectares in common rough grazing.Footnote1 The average size of a farm holding is 81 hectares, but there is a large range with 105,000 holdings under 20 hectares and 41,000 holdings over 100 hectares. On the latest 2016 figures, 36% of all farm holders were over the age of 65 years with just 3% being under 35.

The UK as a whole is currently undergoing a period of uncertainty as it transitions away from the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which, amongst other things, partially paid farmers based on the amount of land they farmed (Basic Payment Scheme). Since agriculture is a devolved issue in the UK, policies are enacted differently in England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.Footnote2 The post-Brexit agricultural transition is thus proceeding differently in each nation. England is transitioning towards a ‘public money for public goods ‘(e.g. environmental and cultural services) system of environmental land management with various schemes being co-designed from before and during the pandemic, and initial pilots taking place from 2021. Wales too is intending to follow a similar system (Sustainable Farming System) opening in January 2025. Scotland began consulting its farming stakeholders in August 2021 on new policies with a test programme from 2022. Northern Ireland’s land border with the European Union has seen direct payments in line with CAP continue until 2022, after which new legislation will be brought forwards. New trade deals also continue to be signed with different countries, each bringing unique sets of impacts to UK farmers. In short, the UK’s departure from the European Union has caused (and is causing) considerable uncertainty for farmers across the UK.

Farmers can struggle to access wellbeing support for many reasons including distance from mental health services, inadequate rural healthcare provision, and lack of public transport.Citation10,Citation15 The impacts of poor mental health and wellbeing on farmers are exacerbated by a reluctance from some to reach out for support. Farming culture and values commonly attributed to it such as, self-reliance, stoicism, strength, and resilience may mean that farmers do not feel comfortable asking for mental health support.Citation16–18 Farmers have a tendency to be, and to be seen to be, independentCitation18,Citation19 and try to maintain values such as self-reliance and resilience that inhibit them from seeking the help they may need. These values are not shared equally across farming communities, nor indeed amongst farming men, in which ideas of masculinity have sometimes been associated with enhanced stigma of seeking support.Citation19–22

The pandemic, and the associated policy responses of lockdown, social distancing, closed schools and nurseries, poor health and economic disruption, clearly had the potential to impact negatively on already poor farming mental health. Early research conducted at the start of the pandemic explored what the impact of COVID-19 on rural communities (and specifically the mental health of farmers) might be.Citation2–10 This research suggested that farming families may be particularly badly affected by the pandemic as a result of worse-than-average co-morbidities,Citation4 the number of dependent children requiring childcare,Citation4,Citation23 and isolation from healthcare and other rural services. Early research, however, noted that there could also be positive impacts of the pandemic, for example due to farmers being recognised as essential workers or improved working conditions with better sanitation and awareness of worker safety.Citation24

From the perspective of farmers and individuals providing mental health support to them, our research explored the impact of the pandemic between approximately 14 and 21 months after the onset of the pandemic. The following research questions were explored in a UK context:

Taking into consideration farm demographic factors, how has the COVID-19 pandemic affected farmers’ levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation?

How did the pandemic affect the relative importance of selected drivers of poor farming mental health and how did they combine together to create multiple points of stress?

Were there any positive impacts of the pandemic on farming mental health?

We were particularly interested in the complexity of the pandemic as a unique shock event and the multiple stressors it caused or exacerbated, creating a moment of crisis for UK farming (harking back to previous crises e.g. Foot and Mouth disease).Citation25

Methods

Our research was undertaken between May and December 2021, which was an unstable time with ever-changing COVID-19 restrictions in the UK. Research was conducted via a mixed methods approach, incorporating both online and telephone interviews with two online surveys (). Two broad themes were covered in the interviews and surveys: (1) drivers of poor farming mental health and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and (2) the impact of the pandemic on the organisations and individuals who assist farmers with poor mental health. This paper refers to data collected on the first theme. The methods were approved by an ethics committee at the University of Reading, which covered issues such as anonymization, informed consent, confidentiality and data storage. No participants received an incentive to partake in the study.

Support providers

A range of organisations and individuals support farmers in times of stress and distress ().Citation26–28 Their perspective on how and why farmers reached out for support during the pandemic is important.

Table 1. Sources of support for farmers (categorised from a literature review, including).Citation27

They offer formal and informal support such as pastoral support, counselling, financial aid, crisis relief, advocacy, advice, friendship, and information exchange.

We used the Prince’s Countryside Fund National Directory of Farm and Rural Support GroupsCitation29 to contact supporters of farming mental health, as well as professional contacts gained through previous projects and social media. Representatives from England, Wales, and Scotland were interviewed. We did not develop contacts in Northern Ireland until after the interviews were complete and this is a limitation of the study. We conducted a purposeful sample, aiming to interview a range of supporters across the three categories; 14 agricultural (10 farming mental health charities [regional and national], 1 industry group, 3 peer groups), 6 pastoral spiritual (2 chaplains, 3 healthcare, 1 local council) and 2 social support (1 auction mart staff, 1 local community group). We designed a semi-structured interview schedule (to allow flexibility to probe areas of interest raised by the interviewee) based on a scoping literature review undertaken in April 2021 (see Appendix 1). We based our questions around three main themes, (1) General Farmer Support, (2) COVID-19 Farmer Support, and (3) Future Challenges and Solutions. Interviews were piloted with four people, without changes being necessary, and these data were used in subsequent analysis. The ongoing uncertainty with the COVID-19 pandemic meant that face-to-face interviews were not possible and so were conducted online or on the phone. In total, 22 interviews were conducted during the months of May and June 2021, which varied in length from 30 minutes to 70 minutes. They were audio-recorded and transcribed. The interviews were undertaken by three researchers on the project team; interviews were coded both manually and by using NVivo by two co-authors.

The manual coding was undertaken by reading the transcripts over fully and looking for broad themes. Once themes were established, the transcripts were read over again multiple times to search for relevant quotes that fit with the themes. These were manually highlighted and grouped together on a word document and then finally added into a report that set out the main themes from the data and backed them up with quotes. The NVivo coding followed a similar strategy, employing the software to identify emerging themes from the transcript and organise them using nodes and sub-nodes where required. Inductive and deductive coding were employed, with pre-set themes closely following those set out in the interview guides. All coding was performed from a critical realist perspective and was ultimately merged into a word document in order for researchers to cross-check themes and to make it accessible to the wider team.

We followed up the in-depth interviews with an online survey to explore the same themes (using the Qualtrics survey platform) for the same target group across the whole of the UK (see Appendix 2). The survey was open between November and December 2021. It was available in English and Welsh. We began distribution by contacting our earlier interviewees and asked them to complete, and share, the surveys with their own networks. We then advertised the surveys on social media, in the farming press, and via farming forums. In total 93 supporters of farming mental health answered the survey ( in Appendix 4).

Farmers

We used an online survey (Qualtrics) distributed in the same way as above to capture the perspectives of farmers themselves on the impacts of COVID-19 on their mental health (see appendix 3). The survey was similarly open between November and December 2021 and available in English and Welsh. We gathered 207 responses from across the UK covering a range of ages, sectors, and a good gender balance ( Appendix 4). Cross-tabulations were only conducted by gender due to smaller sample sizes within categories for other demographics (e.g., age). Open-ended answers were thematically coded.

Results

To provide further context to the responses, farmer survey responses are accompanied by demographic information (age, gender, region, farm type). For consistency, supporter survey quotes are also only accompanied by supporter type. Due to the sensitive nature of the supporter interviews, and the smaller pool of individuals that can threaten full anonymization, quotes from the transcripts are only accompanied by the supporter type (e.g., chaplain or mental health charity).

Detrimental effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

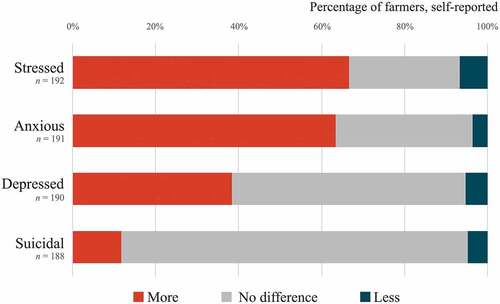

We asked farmers to self-report on how the pandemic had affected their levels of stress, anxiety, suicidal ideation and depression. In total, 67% of farmers surveyed reported feeling more stressed, 63% felt more anxious, 38% felt more depressed, and 12% felt more suicidal ().

Figure 2. Changes to levels of self-reported farmer stress, anxiety, depression and suicide during the pandemic (n varies as each sub-question was not compulsory).

Female respondents were notably more likely to report increased levels of anxiety and stress during the pandemic (see ).

Table 2. Reported levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and suicide by gender.

In the interviews with members of support organisations, we heard evidence that more farmers were struggling:

“Anecdotally we’re hearing of an awful lot more farmers who are struggling. In terms of suicides, the rate is really high anyway, but I would say reports of people considering or attempting suicide have increased.” (supporter 21, mental health charity)

Supporters of farming mental health also spoke about the knock-on effects of greater anxiety and stress. One said that “if your anxiety levels are up, then anything that might be lurking that you would normally cope with, you don’t cope with” (supporter 16, chaplain), suggesting that anxious farmers would be less resilient to various pressures.

Drivers of poor mental health during the pandemic

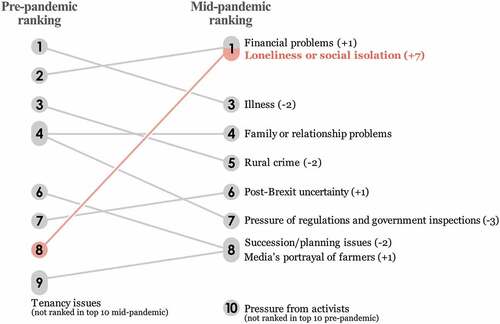

We asked farmers to give the reasons why they have reached out for mental health support before and during the pandemic. shows the top ten drivers of poor farming mental health at both times, noting that 104/207 and 112/207 had not accessed mental health support before or during the pandemic respectively (with a roughly equal split between men and women). Loneliness and social isolation became the joint biggest drivers of poor mental health during the pandemic, up from a position of eight beforehand.

The supporter survey results (n = 93) showed that the main reasons that farmers reached out to organisations for support during the pandemic were loneliness and social isolation (89% of supporters selected this), family or relationship issues (87%), financial problems (82%), illnessFootnote3 (75%) and pressure of regulations and inspections from government (66%). An arable farmer from the East of England (45–54, male) in the survey said during the pandemic, “all services from NHS GPs were totally unavailable in person” with “online services on 3 months wait”. An open-ended response from a mental health charity worker in the supporter survey said that the experience of COVID-19, had “enhanced fear of the future and instilled concern about the trustworthiness of government”, a point supported by an upland livestock farmer from Wales (35–44, male) who said he was “worried about Welsh Government inspections and the inspector’s DELIBERATELY AGGRESSIVE stance’ (capitals in original).

Interviews with support providers added detail to the drivers of poor mental health identified above, and added new ones. There was a clear sense that you cannot “pull out any one of these [drivers] in total isolation” (supporter 17, chaplain), and that contextual events such as changes in agricultural policy post-Brexit in the UK were a significant source of stress. Additional drivers of poor farming mental health at any time mentioned in the interviews were: weather/climate change, labour shortages, feeling undervalued by government and society, animal and crop disease outbreaks, and workplace incidents on the farm. Supporters added further detail on why farmers had reached out during the pandemic. One argued that farmers who they had worked with thought that the government or society was “not valuing what food producers have done for the countryside” (supporter 17, chaplain), perhaps typified by a sense that the media have a “terrible agenda against farming” (supporter 10, auction mart staff). This is joined by the pressure of record keeping “and the consequences of failing an inspection … can break someone” (supporter 21, mental health charity). Combined with a number of other problems, such as “poor housing, isolation” (supporter 11, mental health charity), having vegans “shouting abuse” (supporter 10, auction mart staff), family issues such as bereavement with its “enormous consequences” (supporter 21, mental health charity) and illness during the pandemic, plus succession concerns which can “plunge [farmers] into a really bad place” (supporter 2, mental health charity), the impact on mental health is wide-ranging.

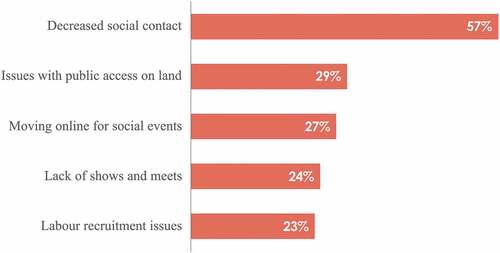

The pandemic itself provided a range of unique pressures that exacerbated existing poor mental health. The top five pressures identified (n = 207) were decreased social contact (57%), followed by problems with the public on private land when exercising (29%), moving online for social events (27%), lack of agricultural shows and meets (24%), and labour recruitment issues (23%) ().

Figure 4. Specific issues caused by COVID-19 that impacted negatively on farming mental health (n = 207).

Other COVID-related effects challenging more than 15% of farmers (n = 207) were moving online for work (21%), physical isolation (21%), anxiety of contracting COVID-19 (19%), lack of sales/trade (19%), family and relationship issues (19%), decreased access to frontline services (18%) and an increase in addictive behaviours (16%). The introduction of COVID restrictions are more likely to have impacted on younger respondents in some cases. For example, 86% of 18–24 year olds and 74% of 25–34 year olds reported that reduced social contact had impacted on their mental health compared to 58% of the sample as a whole. Livestock farmers – who often find it hard to get away from the farm – were more likely to report that the lack of agricultural shows impacted on their mental health with 32% of lowland and 40% of upland livestock farmers reporting this compared to 24% of the sample as a whole. An open-ended survey comment in the supporter survey (mental health charity worker) focused on long-term COVID-related loneliness and social isolation and its links to other factors:

“Loneliness and isolation will keep affecting some as they re-adjust to seeing people again. Some are struggling with social anxiety. More have joined online platforms like Facebook and are grieved by anti-farming comments and have fallen out with people, causing more social isolation.”

Other such supporter survey comments related to the likelihood that the pandemic would negatively impact farming mental health for the long-term. One comment was that the pandemic would “without a doubt” cause “an increase in long-term mental health issues” with several comments referring to the long-term impact of increased isolation and loneliness causing more introversion, as well as stress and depression. Some comments argued that it was “too early to say” (chaplain), again cementing the notion that the pandemic’s impacts could be long-lasting and delayed. Others, however, felt that “farmers will recover in the long-term” (regional farming charity) and “bounce back” (national farming charity).

The interviews with members of support organisations probed how the pandemic had uniquely affected farming mental health. Business challenges, labour shortages, increased wait time for support services, increased rural isolation and the rural digital divide, poor physical health, and fewer opportunities to talk to friends and support networks, were all discussed. One farmer mentioned to a supporter (supporter 1, mental health charity) that the inability to “get out there with your friends and go to a pub or dances or hog roasts” had been a major challenge. Isolation could be increased by poor digital connectivity. As one supporter said, who lived in a rural area, “I live in the middle of nowhere … the wi-fi is just not strong enough” (supporter 10, auction mart staff). Family breakdown, childcare issues, bereavement, and increasing addictive behaviours (e.g. alcoholism) and domestic abuse were also reported by support organisations who had assisted farmers during the pandemic. “Drop-and-go” policies for leaving livestock (farmers not allowed to stay with stock as they were sold) and social distancing at livestock marts, where farmers could not speak to fellow farmers or stay with their stock to watch the sale was also a challenge. According to one supporter:

“A farmer said “this is all wrong. I’ve been with these lambs since they were born. I’ve looked after them. I’ve now had to leave them and at the last point in their life, I’ve had to go away.” And he was all but in tears.” (supporter 17, chaplain)

Another had said to a supporter that he had “dropped the livestock off and gone … all social contact basically went for farmers” (supporter 9, Council worker).

Positive impacts of the pandemic on farmers

Both the farmer survey and the supporter interviews highlighted that the impact of COVID-19 on farming mental health had not been universally negative. As one supporter (supporter 8, Health Worker), who also farmed, argued in an interview, “it’s actually been business as usual”, whilst another (supporter 1, mental health charity) argued that farmers were still “able to get out and walk around … and do work relatively unencumbered”. In one sense, therefore, some farmers “realised that their industry was less affected than most” (supporter survey, charity). Some farmers were very positive about the consequences of the pandemic. One said in an open-ended survey response that the pandemic was the “best thing that ever happened” as it “allowed a whole refocus of life and business” (45–54, male, West Midlands, Mixed), whilst another said “lockdown was the best invention ever” (45–54, male, Yorkshire and the Humber, mixed). Another said they were “very happy with the new world and having the ability to not do things” (55–65, male, East of England, arable).

Specific benefits of the COVID-19 pandemic on farming were noted by farmers and supporters in our study. The first theme raised was that farmers received more recognition and value from the general public as essential workers (even if this was fleeting), providing food on the supermarket shelves. One farmer said (farmer survey, 25–34, West Midlands):

“I think farmers were more valued by the general public as we were seen as key workers and the importance of food production and food security were more in the spotlight.”

Some farmers enjoyed having the family together more often at home, although it was a stressor for some. One farmer (35–44, male, West Midlands) noted:

“My wife couldn’t work so to be honest it was amazing that I could see her more and know that the family were safe.”

Lockdown responses to the pandemic, and the requirement for people to stay local, promoted business opportunities for some. An auction mart staff member (supporter 10) noted in an interview:

“more people have stayed in this country for obvious reasons … there’s been more food eaten in this country, and people haven’t been spending on other things, so they’ve spent money on food. I think people have learnt to cook and learnt to eat better, and it’s all helped, certainly the red meat industry, massively.”

In strict lockdown, both farmers and supporters noted that the decrease in rural traffic and that it had become “pleasantly quiet” (supporter 8, Health worker).

Others noted increased community cohesion in rural areas as people came together to support one another in turbulent times. In interview, a chaplain (supporter 3) said:

“ … the communities there have come together … who is your neighbour has become quite an important question, and in rural places you tend to know who your neighbour is and you’ve got to know it far better during the pandemic than you would have done beforehand.”

Supporters of farming mental health also noted that the pandemic had increased the take-up of digital methods of engagement by the farming community (though not by all) as advice was delivered online. One farming charity interviewee (supporter 18) said:

“COVID has obviously been very negative, but also it’s also engaged people digitally in a way that has perhaps moved us forward 10 years in terms of how the farming community are consuming information.”

Discussion

Despite some positive impacts of the pandemic on community cohesion, digital engagement, and valuing farmers, it is clear that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing poor mental health across farming communities in the UK, a finding that is likely to be replicated elsewhere. As one supporter of farming mental health argued in the survey, “unless the fundamental problems are addressed, then farmers mental health will continue to suffer.” Our research shows that whilst it is important to address the mental health impacts of the pandemic, an undue focus on the pandemic’s impacts could mask many other drivers of poor farming mental health that existed long before, and will exist long after, COVID-19. The impact of multiple stressors hitting farmers at once can create a tipping point, which means that farmers cannot cope with an additional pressure, however minor it might be if experienced on its own.

Many of the concerns revealed by research conducted early in the pandemic about existing poor physical health in the farming community,Citation4 childcare dependencyCitation4,Citation23 and isolation from healthcare and rural servicesCitation2–5 were well-founded. The social isolation of farming communities has clearly been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which not only restricted the ability of farmers to receive professional pastoral support for mental health, but also reduced interaction with agricultural peers, spiritual helpers like chaplains, and social support from friends in local pubs and at agricultural shows and markets. Such social contact can provide a vital buffer to poor mental health.

Our research has also shown, however, that different drivers of poor farming mental health are likely to affect different types of farmers in varying ways. A distributed scale of mental health problems and impacts across different types of farmers was noted in the Big Farming Survey.Citation12 The higher levels of self-reported stress and anxiety from female farmers in our study may be explained by one or both of two reasons: firstly, that female farmers are more likely to self-report feeling stressed and anxious and secondly, that female farmers, as discussed in the literature, suffer disproportionate demands on their time during and outside of times of crises – including an enhanced childcare burden and caring responsibilities. The emphasis on rural masculinities in mental health-related studies often overlook the risks posed to women in agricultural communities, when in fact almost half of women in farming between the ages of 25 and 54 are possibly or probably depressed,Citation11,Citation12 for reasons not necessarily attributable to the pandemic. Gender needs, therefore, to be considered in further investigations of rural mental health moving forward. Younger farmers in our survey reported more of a negative mental health impact from lack of social contact during the pandemic than older farmers. However, not all farmers in our study were negatively impacted by the unique shock event of COVID-19. Our quotes on the positive impacts of the pandemic, including the quotes implying a sense of calm and enhanced mental wellbeing as a result of lockdown and social distancing, illustrate the complexity of isolation. In some ways, it can be a key problem for farming mental health, but for some farmers, it can be something that they enjoy. For all the problems brought by crises, certain events could allow farming communities to reset and adapt, as noted with the faster adoption of digital communication and local business opportunities during lockdown.

An important message from this study concerns the likely medium to long-term effects on farming mental health. Stress and anxiety can worsen over time and lead to crisis events such as clinical depression and suicide and the long-term and delayed impacts of the pandemic were noted in both supporter interviews and survey responses. Self-reported levels of stress and anxiety increased for more than 60% of farmer respondents (and even larger proportions of female respondents), illustrating that poor mental health is an issue faced by all genders. Without adequate support and policy intervention, these could lead to more serious mental health outcomes in the coming years. Shock events can have long lasting consequences, as for example, seen with Foot and Mouth Disease in the UK,Citation25,Citation30,Citation31 or market crises in New ZealandCitation32 or the farm debt crisis of the 1980s in the USA.Citation33 Suicides and depression linked to these events are still reported today.

Conclusion

Researchers and policy-makers across the world should be mindful of the long-term scarring effects of the pandemic, alongside the long-term effects of the agricultural policy transitions being undertaken globallyCitation34 that disrupt farming communities and heighten levels of stress and anxiety. Other shock events will occur in the future – animal or crop disease outbreaks, human pandemics, climate breakdown, amongst others – and therefore, lessons about how farming communities have coped (or not) with COVID-19 can help in planning future responses. The experience of the pandemic striking at a time of multiple stressors, such as policy uncertainty and more recently by the fuel and energy price crises, shows that the context and complexity of shock events is important. When a single shock event, such as the pandemic, causes multiple problems (e.g., shielding, childcare issues, isolation, market disruption), the impacts of mental health are likely to be worse and long-lasting. However, our research also illustrates the need for more nuanced research into how crises affect farming mental health and how they might affect some types of farmers, for good or bad, in different ways (e.g., younger/older, male/female). Though local contexts will vary, our findings are likely to hold global relevance in terms of understanding how farming communities may struggle in times of crisis.

As Phillipson et al.Citation5 argued at the start of the pandemic, the mental health impacts of COVID-19 are likely to be more pronounced in rural areas that are “less able to maintain social contact online whilst social distancing and shielding” as a result of poor broadband and inadequate mobile phone connections in many of these places. Our findings show that whilst some farmers were able to adapt to digital forms of engagement during the pandemic, those struggling with low digital literacy, poor broadband and mobile phone connectivity were disproportionately affected. Farmers across the board tended to struggle more than ever to access rural frontline services. When future shocks appear, the rural digital divide and poorer access to frontline services (a global problem), will marginalise some rural communities again without appropriate intervention.

Strategies to address poor farmer mental health need to be tailored to farming and rural landscapes, which face different challenges than urban areas, including isolation, a more pronounced digital divide, and reduced access to primary healthcare services. Yet, there is still much that we do not know. Globally, there is limited information on how mental health differs according to certain characteristics, including between farm types, ages, genders, regions. Consequently, there is little known about how best to target interventions to support different farmers. Furthermore, there is minimal research that breaks down crisis events by complexity such that the effects of multiple stressors striking at the same time can be investigated. Ultimately, farming mental health is a challenge that requires as much research and industry attention as other longer-established occupational health and safety issues. We hope this paper inspires further action to normalise conversations around mental health in farming communities, to address the rural digital and service divide, and to conduct further research on how to target support differently to farmers and other people who work on the farm.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the organisations and individuals who helped to distribute and answer surveys and interviews. We thank Juliette Schillings for coding survey responses. We thank Veronica White for her assistance with the figures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Anonymised survey data is available at https://reshare.ukdataservice.ac.uk/855791/. Interview data is unavailable for ethical reasons given it is a sensitive topic and the sample population is small and potentially identifiable. Interviewees did not give permission for data to be archived.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/868945/structure-jun19-eng-28feb20.pdf and https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/agriculture-in-the-united-kingdom-2021

3. As interpreted by each respondent – we did not specify type of illness (e.g. physical or mental).

References

- Lobley M, Winter M, Wheeler R. Chapter 7. Farmers and social change: stress, well-being and disconnections. In: Lobley M, Winter M, Wheeler R, eds. The Changing World of Farming in Brexit UK. London: Routledge; 2019:168–201.

- Darnhofer I. Farm resilience in the face of the unexpected: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Agric Human Values. 2020;37(3):605–606. doi:10.1007/s10460-020-10053-5.

- Hossain M, Purohit N, Sharma R, Bhattacharya S, McKeyer EL, Ma P. Suicide of a farmer amid COVID-19 in India. Healthcare. 2020;8:1–8.

- Meredith D, McNamara J, Van Doorn D, Richardson N. Essential and Vulnerable: implications of Covid-19 for Farmers in Ireland. J Agromedicine. 2020;25(4):357–361. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2020.1814920.

- Phillipson J, Gorton M, Turner R, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and its implications for rural economies. Sustainability. 2020;12(10):1–9. doi:10.3390/su12103973.

- Rudolphi JM, Barnes KL. Farmers’ Mental Health: perceptions from a Farm Show. J Agromedicine. 2020;25(1):147–152. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2019.1674230.

- Smith K. Desolation in the countryside: how agricultural crime impacts the mental health of British farmers. J Rural Stud. 2020;80:522–531. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.10.037.

- Wypler J, Hoffelmeyer M. LGBTQ+ Farmer Health in COVID-19. J Agromedicine. 2020;25(4):370–373. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2020.1814923.

- Adhikari J, Timsina J, Raj Khadka S, Ghale Y, Ojha H. COVID-19 impacts on agriculture and food systems in Nepal: implications for SDGs. Agric Syst. 2021;186:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102990.

- Henning-Smith C, Alberth A, Bjornestad A, Becot F, Inwood S. Farmer Mental Health in the US Midwest: key Informant Perspectives. J Agromedicine. 2022;27(1):15–24. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2021.1893881.

- Wheeler R, Lobley M. “It’s a lonely old world”: developing a multidimensional understanding of loneliness in farming. Sociologia Ruralis. 2022; Accepted;Forthcoming. doi:10.1111/soru.12399.

- Wheeler R, Lobley M. Health-related quality of life within agriculture in England and Wales: results from a EQ-5D-3L self-report questionnaire. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13790-w.

- Baker C (2021). Mental health statistics (England). A report for the House of Commons library. Available at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06988/SN06988.pdf (Accessed July 2022).

- Yazd SD, Wheeler SA, Zuo A. Key risk factors affecting farmers’ mental health: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23):4849. doi:10.3390/ijerph16234849.

- Vayro C, Brownlow C, Ireland M, March S. “Don’t … Break Down on Tuesday Because the Mental Health Services are Only in Town on Thursday”: a Qualitative Study of Service Provision Related Barriers to, and Facilitators of Farmers’ Mental Health Help-Seeking. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2021;48(3):514–527. doi:10.1007/s10488-020-01085-4.

- Crimes D, Enticott G. Assessing the Social and Psychological Impacts of Endemic Animal Disease Amongst Farmers. Front Vet Sci. 2019;6:342. Published 2019 Oct 4. doi:10.3389/fvets.2019.00342.

- Vayro C, Brownlow C, Ireland M, March S. “Farming is not Just an Occupation [but] a Whole Lifestyle”: a Qualitative Examination of Lifestyle and Cultural Factors Affecting Mental Health Help-Seeking in Australian Farmers. Sociologia Ruralis. 2020;60(1):151–173. doi:10.1111/soru.12274.

- Emery SB. Independence and individualism: conflated values in farmer cooperation? Agric Human Values. 2015;32(1):47–61. doi:10.1007/s10460-014-9520-8.

- Roy P, Tremblay G, Robertson S, Houle J. “Do it All by Myself”: a Salutogenic Approach of Masculine Health Practice Among Farming Men Coping With Stress. Am J Mens Health. 2017;11(5):1536–1546. doi:10.1177/1557988315619677.

- Cole DC, Bondy MC. Meeting Farmers Where They Are - Rural Clinicians’ Views on Farmers’ Mental Health. J Agromedicine. 2020;25(1):126–134. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2019.1659201.

- Allan JA, Waddell CM, Herron RV, Roger K. Are rural Prairie masculinities hegemonic masculinities? Norma. 2019;14(1):35–49. doi:10.1080/18902138.2018.1519092.

- Herron RV, Ahmadu M, Allan JA, Waddell CM, Roger K. “Talk about it:” changing masculinities and mental health in rural places? Soc Sci Med. 2020;258:113099. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113099.

- Salzwedel M, Liebman A, Kruse K, Lee B. The COVID-19 Impact on Childcare in Agricultural Populations. J Agromedicine. 2020;25(4):383–387. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2020.1815616.

- Franklin RC, O’Sullivan F. Horticulture in Queensland Australia, COVID-19 Response. It Hasn’t All Been Bad on Reflection. J Agromedicine. 2020;25(4):402–408. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2020.1815620.

- Bennett K, Carroll T, Lowe P, Phillipson J. Coping with crisis in Cumbria: consequences of Foot and Mouth Disease. University of Newcastle: 2002

- Hagen BN, Harper SL, O’Sullivan TL, Jones-Bitton A. Tailored Mental Health Literacy Training Improves Mental Health Knowledge and Confidence among Canadian Farmers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3807. doi:10.3390/ijerph17113807.

- Nye C, Lobley M. COVID-19, Christian Faith and Wellbeing. University of Exeter ; 2020. Available at: https://sociology.exeter.ac.uk/research/crpr/research/publications/researchreports/

- Nye C, Winter M, Lobley M. The role of the livestock auction mart in promoting help-seeking behavior change among farmers in the UK. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1581. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13958-4.

- The Princes’ Countryside Fund. National Directory of Farm and Rural Support Groups. 2021. Available at: https://www.princescountrysidefund.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Support-Groups-directory-2021-spreads-1.pdf (Accessed April 2022)

- Convery I, Bailey C, Mort M, Baxter J. Death in the wrong place? Emotional geographies of the UK 2001 foot and mouth disease epidemic. J Rural Stud. 2005;21(1):99–109. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2004.10.003.

- Hodges M. Foot and mouth outbreak 20 years on - Have lessons been learned in Cumbria? The Cumberland News. 2021. Available at: https://www.newsandstar.co.uk/news/19100748.broadcast-journalist-caz-graham-looks-back-devastating-foot-and-mouth-outbreak-2001/ (Accessed April 2022)

- Beautrais AL. Farm suicides in New Zealand, 2007-2015: a review of coroners’ records. Australian & New Zealand J Psychiatry. 2017;52(1):78–86. doi:10.1177/0004867417704058.

- Snee T. Long after ’80s farm crisis, farm workers still take own lives at high rate. 2017. Available at: https://now.uiowa.edu/2017/06/long-after-80s-farm-crisis-farm-workers-still-take-own-lives-high-rate (Accessed April 2022)

- de Boon A, Sandström C, Rose DC. Governing agricultural innovation: a comprehensive framework to underpin sustainable transitions. J Rural Stud. 2021;89:407–422. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.07.019.

Appendix 1

Supporter interview questions (bold questions used in this paper).

Introductory questions

1) Tell me about your job role and what you do.

2) Tell me about what your organisation does and how do they support farmers’ mental health?

Section 1 (General Farmer Support):

3) In your experience where do farmers go for support? Are you aware of any farmer groups in the areas within which you work (such as farmer clusters, facilitation-funded groups or discussion groups)? If so, do you think these play a role in terms of social support?

4) What do you think the reasons might be if farmers do not reach out for support?

5) How many other farmer support organisations operate in your geographical area? Do you ever work together with these other organisations? In what way?

6) What sort of people do you tend to work with? I mean in terms of age, gender, farming sector, farm size, geography?

7) What are the worries that farmers face?

8) Do you find there are issues with low mental health? (Yes/No) What effects does this have (e.g. on what/whom, their business, family)?

9) What challenges do organisations such as yours face when providing or offering support?

10) How important do you think faith (such as Christianity) is to some of the people you support?

Section 2 (Covid-19 Farmer Support specific):

11) In a few words, can you describe how you think Covid-19 affected farmers?

12) How has the Covid-19 pandemic impacted farmer mental health from your point of view?

13) What kind of support have you/your organisation offered during the Covid-19 pandemic?

14) Does this support differ to what was offered pre-pandemic?

15) Have there been challenges to providing this support during the Covid-19 pandemic?

16) What measures have you had to implement in order to continue being effective as an organisation?

17) Are you seeing the same issues since the beginning of the pandemic? (Yes/No) Do these issues tend to be more or less severe than before the pandemic?

18) Are you aware of a change in specific mental health issues arising as a result of Covid-19? How might further change in attitudes be facilitated?

19) How might you compare the impact of Covid-19 on the mental health/wellbeing of farmers with that of other crises, such as foot and mouth?

Section 3 (Future challenges and solutions):

20) If there have been challenges, how could support be offered to you/the organisation?

21) Would support from the government, e.g. DEFRA, help?

22) Are there any risks attached to receiving to funding from DEFRA?

23) Is there a risk attached to too many organisations competing in what is now a rather crowded area of work? How do you feel about the number and type of other organisations offering support to farmers?

24) What do you think will be the main issues for farmers moving forward into a post-pandemic world?

25) Do you see any solutions to these challenges?

Closing questions and remarks:

26) Are there any other issues relating to mental health and farmer support you would like to raise?

27) Are there any other issues regarding the post-pandemic world that you think are important and will affect the mental health of farmers?

Appendix 2

Supporter survey questions (questions in bold analysed for this paper)

Q1 What is your age?

○ 18–24 years old

○ 25–34 years old

○ 35–44 years old

○ 45–54 years old

○ 55–65 years old

○ 66+

Q2 What is your gender?

○ Male

○ Female

○ Non-binary/third gender

○ Prefer not to say

○ Other, please state _______________________________

Q3 Which region do you work in? Please select from the list below (you could choose more than one).

North-East

East Midlands

Yorkshire and the Humber

South-West

West Midlands

East of England

North-West

London

South-East

Scotland (please state which county) ______________

Wales (please state which county) ________________

Northern Ireland (please state which county) ___________________________________________

Q4 Which of the following are you involved in as an employee or volunteer? Please select all that apply.

Industry body (e.g. NFU, AHDB, LEAF)

National Farming Charity (e.g. non-mental health specific)

Regional Farming Charity (e.g. non-mental health specific)

Religious Charity

Faith Group (e.g. chaplain)

Primary Healthcare

Mental Health Charity (farmer focused)

Mental Health Charity (general)

Finance and Advice Organisation/Business

Local Community Group

Auction Mart

Rural Pub

Agricultural Show

Other, please state _____________________________

Q5 Who do you frequently work with to provide support to farming families? Please select all that apply.

Industry body (e.g. NFU, AHDB, LEAF)

National Farming Charity (e.g. non-mental health specific)

Regional Farming Charity (e.g. non-mental health specific)

Religious Charity

Faith Group (e.g. chaplain)

Primary Healthcare

Mental Health Charity (farmer focused)

Mental Health Charity (general)

Finance and Advice Organisation/Business

Local Community Group

Auction Mart

Rural Pub

Agricultural Show

Farmer Groups

Other, please state ______________________________

Don’t work with others

Q6 Are you an employee or volunteer within the organisation/group you work for/help out in?

○ Employee

○ Volunteer

○ Other, please state ______________________________

Q7 On a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much), how serious were the following barriers to providing mental health support to farming families during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Q8 Which of the following were reasons why farming families reached out for support before the COVID-19 pandemic? Please select all that apply.

Loneliness and/or social isolation

Illness (including diagnosable mental health issues)

Family or relationship issues

Succession/exit planning issues

Financial Issues

Pressure of regulations and inspections from the government

Post-Brexit policy uncertainty

Tenancy Issues

The media’s portrayal of farmers

Online criticism

Accidents on the farm

Other, please state ___________________________

Q9 Which of the following were reasons why farming families reached out for support during the COVID-19 pandemic? Please select all that apply.

Loneliness and/or social isolation

Illness (including diagnosable mental health issues)

Family or relationship issues

Succession/exit planning issues

Financial Issues

Pressure of regulations and inspections from the government

Post-Brexit policy uncertainty

Tenancy Issues

The media’s portrayal of farmers

Online criticism

Accidents on the farm

Other, please state ___________________________

Q10 In your experience of providing mental health support to farming families, who tends to reach out first for support? Please select from the below list.

○ Farmer themselves

○ Farming families

○ Farming friends

○ Other, please state _______________________________

Q11 During the COVID-19 pandemic, what has worked best in terms of how to offer mental health support to farming families?

________________________________________________________________

Q12 In your opinion, were there any positive consequences of the pandemic in terms of either farmer mental health or your ability to provide support?

Q13 What do you think might be the long-term effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on mental health and resilience in farming communities?

________________________________________________________________

Q14 What support would your organisation benefit from in the future, in order to support farming families’ mental health more effectively?

________________________________________________________________

Q15 Do you have any other comments to make on the topic of farmer mental health support?

Appendix 3

Farmer survey questions (questions in bold analysed for this paper)

Q1 What is your age?

○ 18–24 years old

○ 25–34 years old

○ 35–44 years old

○ 45–54 years old

○ 55–65 years old

○ 66 years old and above

Q2 What is your gender?

○ Male

○ Female

○ Non-binary/third gender

○ Prefer not to say

○ Other (please state) ____________________________

Q3 Which region do you farm in? Please select from the list below (select more than one if farm straddles border).

North-East

East Midlands

Yorkshire and the Humber

South-West

West Midlands

East of England

North-West

London

South-East

Scotland (please state which county) _______________

Wales (please state which county) ________________________________________

Northern Ireland (please state which county) ________________________________________

Q4 Which of the following categories best describes your farming enterprise? Select one.

○ Arable/General Cropping

○ Lowland Livestock

○ Upland Livestock

○ Mixed

○ Dairy

○ Pigs

○ Poultry

○ Horticulture

○ Other, please state ________________________________________

Q5 For which of the following reasons have you reached out for support before the COVID-19 pandemic? Please select all that apply.

Loneliness and/or social isolation

Illness (including diagnosable mental health issues)

Family or relationship issues

Succession/exit planning issues

Financial Issues

Pressure of regulations and inspections from the government

Post-Brexit policy uncertainty

Tenancy Issues

The media’s portrayal of farmers

Online criticism

Accidents on the farm

Pressure from animal rights/activists’ groups

Rural crime

Haven’t reached out for support

Other, please state ______________________________________

Q6 For which of the following reasons have you reached out for support during COVID-19 pandemic? Please select all that apply.

Loneliness and/or social isolation

Illness (including diagnosable mental health issues)

Family or relationship issues

Succession/exit planning issues

Financial Issues

Pressure of regulations and inspections from the government

Post-Brexit policy uncertainty

Tenancy Issues

The media’s portrayal of farmers

Online criticism

Accidents on the farm

Pressure from animal rights/activists’ groups

Rural crime

Haven’t reached out for support

Other, please state ________________________________________

Q7 What challenges did you face during Covid-19 restrictions that affected your mental health? Please select all that apply.

Decreased social contact

Labour/recruitment issues

Lack of shows/shepherds meets

Lack of sales/trade

Moving online for social events

Moving online for work

Increase in addictive behaviours (e.g. alcohol consumption)

Anxiety linked to contracting COVID-19

Issues with general public on private land or public rights of way

Illness within the family

Family or relationship issues

Bereavement

Decreased access to frontline services (e.g. NHS)

Physical isolation

Drop-and-go at marts

Shielding

Other, please state ________________________________________

Q8 During the COVID-19 pandemic, did you feel:

Q9 On a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much), how did the following barriers impact your decision to seek (or not seek) mental health support during COVID?

Q10 If you received help for low mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, which of the following means of support did you find useful? Please select all that apply:

GP appointment in person

GP appointment online

In person counselling service appointment

Online counselling service appointment

Telephone call with friend

Telephone call with charity

Online charity call

Face-to-face charity visit

Face-to-face conversation with friend

Other, please state ______________________________________

Not Applicable

Q11 In your opinion, were there any positive consequences of the pandemic for the support of farming families’ mental health?

________________________________________________________________

Q12 What support would you benefit from in the future to help you reach out for mental health support?

________________________________________________________________

Q13 Do you have any other comments to make on the topic of farmer mental health support?

________________________________________________________________

Appendix 4

Sample characteristics

Table A. Sample characteristics of supporter survey.

Table B. Sample characteristic of farmers’ survey.