ABSTRACT

Objectives To assess demographic and causal factors of fatal farm incidents involving animals in Australia. Methods Descriptive study of the National Coronial Information System for persons fatally injured by an animal on an Australian farm over the 2001–20 period. Data were analysed in relation to age, sex, state where incident occurred, work-relatedness and causal agents. Results There has been little change in the mean number of animal-related injury deaths across Australia in the 2001–20 period (mean 6.5), however this is a 35% reduction on an earlier 1989–92 assessment (mean 10). The majority of incidents (81%) involved horses (n = 75) and cattle (n = 31). Males were involved in 86 (66%) cases, with 54 female cases. People aged 60 years and over accounted for 46% of the cases, with more than half occurring during work. Of the decedents, 85% fell from or were struck by an animal at the time of the incident, with 40% resulting in a head injury. Conclusion While annualized case numbers have decreased slightly, the leading agents remain consistent with previous studies. The lack of genuine progress in addressing fatalities related to horses and cattle, along with the representation of older persons in the cohort, require attention drawing on the Hierarchy of Controls.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Farm animals are central to the rural landscape as well as the culture of farming across Australia. Generally, farm animals are referred to as livestock and are kept for production or lifestyle. However, there are also native animals such as bees, snakes, and spiders that can have fatal impacts. Livestock involved in farm production or used for recreational purposes on farm, include cattle, horses, sheep, pigs, poultry, and goats. While seemingly harmless animals, there are specific characteristics (e.g. size, speed, and potential aggression), which may increase the injury risk.Citation1

Internationally, farming is considered to be one of the most dangerous workplaces.Citation2–4 In addition, fatalities involving livestock, especially large animals such as cattle and horses, have been consistently reported.Citation5,Citation6

Added to this, data from Safe Work Australia indicate livestock farmers and workers accounted for almost half of all work-related fatalities from 2013–16. Furthermore, 11% of serious workers compensation claims in the agricultural sector occurred from being hit by an animal.Citation7 Similar findings have been observed overseas, with the most common mechanism of injury being struck/kicked by an animal.Citation8–10 Historically, sentinel data from an Australian study assessing fatal injury in 1989–92, indicated an average of 10 cases per year involving an animal, with two-thirds of these being work-related and 57% resulting from being hit or bitten by an animal.Citation11 In recent years, several parts of Australia have been subjected to rainfall deficiencies leading to drought conditions.Citation12 With drought, stock handling and feeding is increased as diminishing fodder and water levels become critical. Subsequently, this increased exposure time raises the potential risks for persons working with or around livestock.

Livestock farmers and workers are involved in a range of tasks such as feeding and inspecting, mustering stock, drafting in yards, loading/unloading for transport, assisting cows during calving, castrating, branding, ear marking, identification tagging, shearing, mulesing, milking, shoeing, mating, artificial insemination, administering drench or vaccinating and handling sick or injured animals. Additionally, recreational activities involving animals may include horse riding or learning to ride a horse.

Despite the prevalence and severity of agricultural injuries in Australia, there is limited national research specific to farm-animal-related injury. In turn, the lack of insufficient data and recent climatic conditions forcing increased handling and movement of livestock, is prompting further investigation. The purpose of this study was to describe non-intentional fatal injury caused by animals on Australian farms during 2001–2020 and examine evidence based solutions to reduce the impact.

Methods

The National Coronial Information System (NCIS) is a secure database of information for reportable deaths to the Australian and New Zealand coroner.Citation13 This study draws on available data from the NCIS register from 2001 through to the latest available (December 31, 2020). Cases pertaining to Australian farm-related incidents were included where: (i) the person died unexpectedly and the cause of death is unknown; (ii) the person died in a violent or unnatural manner; and (iii) a doctor has been unable to sign a death certificate giving the cause of death. Preliminary information for each case is uploaded into the NCIS and these remain “open” until the coroner hands down a final determination and the case is then “closed”. The term “open” or “closed” is the identifying status of a particular case. For each incident, a Cause of Death is determined and recorded by a coroner, with specific cause of death details independently coded by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) against the International Classification of Disease and Health Related Problems (Tenth Revision) (ICD-10).Citation14

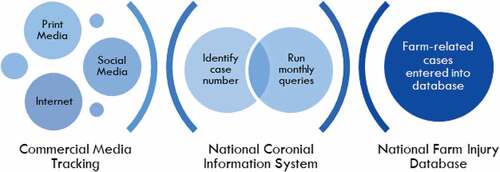

Data extraction from NCIS for inclusion involves two inter-related processes (). First, a commercial media tracking organisation (iSentia/Meltwater) is used to scan approximately 2,500 daily, weekly, and monthly publications Australia wide. Publications are scanned for various designated search terms (e.g. “farm*”, “injury”, “property”, “growers”, “producers”, “horticulture”). Where a potential on-farm case is identified, the corresponding NCIS case file number is obtained for this “open” case. This process has been used since 2005 and has proven to be reliable in identifying potential case events for inclusion.Citation15–17 However, as not all cases are reported in the media, there is potential for cases to be under-numerated. Consequently, the second approach to identifying cases of relevance relies on keyword searches of the NCIS (farm*) for each year. These are then reviewed with cases that are not farm-related and those confirmed as intentional by the coroner, being withdrawn from the dataset.

The available NCIS data for farm-related cases are coded using the Farm Injury Optimal Dataset,Citation18 with farm fatalities including both work and non-work related activities. The dataset provides specific codes on demographics, role in event (e.g. operator, bystander), work relatedness, relevant causal agents of injury (cattle [bull, cow, steer, etc], horses and sheep, etc.), mechanism of injury and other context-specific information as applicable such as helmet usage. Other Australian farm injury studies have widely used the dataset.Citation15–17,Citation19 Data for all deaths on farms where the agent of injury was an animal were extracted from the NCIS database for the period 2001–2020. Hence, these data exclude all incidents that occur off-farm, e.g. horses at a racetrack and cattle at public saleyards, etc. “Open” cases have been included in this study. While “Open” cases contain restricted information, particularly in relation to agent and mechanism of injury, these are included to ensure case numbers are not underrepresented.

Descriptive analyses of the data were completed in Excel including age and sex breakdown, state where incident occurred, work-relatedness, and causal agents. Confidence intervals (95%) were calculated to illustrate the dispersion in the data for work, non-work, and the total number of incidents over the selected time periods. Ethics approval for this study was granted through the Department of Justice Human Research Ethics Committee – Approval number CF/19/27527.

Results

During the study period, 130 people were fatally injured by an animal (mean 6.5/year), consisting of 73 (56.2%) work cases and 57 (43.8%) non-work incidents (). Of the cases, 96.2% were closed (n = 125) by a coroner. Males were involved in 86 (66%) cases, with 54 female cases. There was no statistical variation in the relative proportion of work-related cases or total cases over the years investigated. However, a significant reduction was noted for non-work cases between the 2005–08 and 2017–20 periods.

Table 1. Number of on-farm deaths caused by animal-related injury in Australia, 2001–2020, by work relatedness.

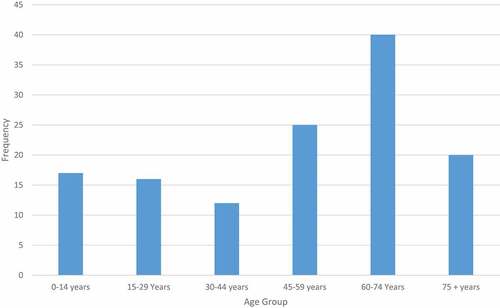

As indicated in , those aged 60 and over, represented almost half (46%) of all deaths. Children (0–14 years) were involved in 17 cases (10.7%). The majority (83%) occurred in the states of New South Wales, Queensland or Victoria.

Leading agents were horses (n = 75) and cattle (n = 31), resulting in over 81% of deaths. Other animals (n = 24); bee, camel, deer, dog, pig, sheep, snake, spider, wasp, accounted for less than 20% of cases. Analysis of the nature of incidents emphasizes the leading mechanism of injury as: falling from an animal (n = 57), being struck by an animal (n = 54) or being bitten (n = 18). These incidents resulted in head (n = 52) and chest (26) injuries as leading causes of fatal injury.

Horses

Horses were responsible for 58% of all cases (n = 75), with males (n = 43) and females (n = 32) being represented. Work-related cases accounted for 41.3% (n = 31) of the cases, with the majority of these (n = 19) occurring whilst mustering livestock. Incidents involving males were more likely to be work related (n = 26), with females predominately recreational (n = 27). Those decedents in the youngest age group (0–14 years), were all recreational. At time of incident, decedents were riding the horse and fell (n = 56), kicked by a horse (n = 8), leading a horse (n = 6) or trampled by a horse (n = 5). Of the 32 head injury cases sustained while riding, helmet use (yes/no) was known for 29 incidents, with eight cases (27.5%) involving a rider wearing a helmet at the time of the incident. Only one of these cases involved a rider over the age of 50 years.

Cattle

The second leading agent centred on cattle, accounting for 24% of all cases (n = 31). Almost all were work-related (98%; n = 30), with more than 75% involving a person aged 60 years and over. Males accounted for 26 (84%) of the decedents. At the time of the incident, persons came into contact with bulls (n = 15), cows (n = 9), and steers (n = 6), with one case unknown. Individuals were drafting stock (n = 11), herding stock (n = 8), loading/unloading stock (n = 6), and feeding or inspecting stock (n = 6) at the time of incident. Overall, 70% were trampled, with cattle yards (n = 23) being the primary location. Of these, eight of the 21 cases (38%) where detail was available, involved people working alone.

Other animals

The involvement of other animals in this cohort (bee, camel, deer, dog, pig, sheep, snake, spider, wasp), resulted in being bitten (n = 18) or struck (n = 6) by an animal. Persons were trampled or crushed by larger animals (camel, deer, sheep) and mauled by smaller animals (dog). Individuals coming into contact with native animals, suffered an anaphylactic reaction from being bitten by a bee or wasp (n = 8) and poisoning from snakes and spiders (n = 6). Cases were equally distributed between work (n = 12) and non-work (n = 12) activities.

Discussion

In this descriptive study, 130 animal-related cases were identified over the 20-year period, representing 8.2% of all on farm non-intentional deaths in this timeframe. Incidents predominantly involved horses and cattle (81%). People aged 60 years and over account for 46% of the cases, with more than half occurring during work. Furthermore, 85% of decedents fell from or were struck by an animal at the time of the incident, with 40% resulting in a head injury. While these data reflect the mortality patterns, there will nonetheless also be a very considerable number of non-fatal cases involving farm animals.Citation20

Over the past 20 years, there has been no significant change in the proportion of fatal cases involving animals for either work or non-work incidents (with the exception of non-work cases between 2005–08 and 2017–20). However, in comparison to previous information covering the 1989–1992 period,Citation11 these data indicate a 47% reduction in the mean number of animal-related fatalities from 40 (mean 10) during the 1989–1992 period to 21 (mean 5.25) in 2017–2020. These numbers are encouraging, particularly in recent years (2017–2020), when a majority of Australia has had extensive drought conditions,Citation21–24 leading to increased stock handling and movement. Despite the overall reduction in cases, horses and cattle continue to dominate the incidents, which is in keeping with previous assessments within Australia, Canada, and the USA.Citation5,Citation25,Citation26

In terms of agricultural safety and injury prevention, the Hierarchy of Controls aim to eliminate or reduce the risk of injury by using evidence-based solutions, ranking from the highest level of protection to the lowest.Citation27 This is also a requirement of Australian Workplace Health and Safety (WHS) Regulations.Citation28 Elimination of the hazard is viewed as the highest level of health and safety protection; however, this may not be “reasonably practicable” in all situations (e.g., removing “rogue” animals – beef cattle, dairy, sheep, pork, and horse production). Reducing risk through substitution (e.g. using alternate vehicles rather than a horse) and engineering controls (e.g. improved cattle yard design to minimise potential contact between handlers and stock), provide the next levels of protection. Administrative actions (training on handling livestock) and use of personal protective equipment (PPE), such as helmets and chest guards, are the least reliable control measures with the lowest level of protection. Consequently, effective implementation of the Hierarchy of Controls should guide intervention approaches to maximise the potential to reduce the impact of animal-related injury. Additionally, it is frequently desirable to not only use the highest level of intervention, but to use a range of all approaches to maximise safety outcomes.Citation27

The analyses clearly define horses as the major cause of fatal injury because of falls from or being struck. Horses are known for their unpredictable nature and intent to hurt (kick or bite), and therefore potentially pose a significant safety risk.Citation29–31 Where “reasonably practicable” horses may be removed or their use restricted in working stock (cattle/sheep). Withstanding this, if not practical, options to substitute for a lesser risk (mustering with a motorbike, side-by-side vehicle or farm ute [pick-up]), should be examined. While there may be alternate foreseeable risks with farm vehicles (e.g. crashes/rollovers), operators maintain physical control over the vehicle, unlike horses. Further, administrative controls to consider include issues relating to the rider (age, experience, training), horse (age, temperament) and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) (e.g. helmets) to reduce potential injury severity.

Lack of helmet use whilst riding horses identified in this study is significant. Notwithstanding that helmets are classed as PPE and are the lowest level of protection within the Hierarchy of Controls, it is reasonable to hypothesise that a number of head injury cases sustained while riding, may have been prevented if helmets were worn.Citation27,Citation32 While fatalities can and do still occur when helmets are worn, as illustrated in these data (8/21 head injury cases),Citation27,Citation32 WHS Regulations in Australia state that employers have a duty of care to provide PPE.Citation28 Therefore, where horse riding is a workplace requirement, approved helmets (AS 2063.3) are an essential PPE item.

Within Australia, helmets are a highly contested issue and the lack of use outlined in this study highlights the necessity for greater attention. It is not infrequent to hear riders are not wearing helmets as “they are too hot”, “too uncomfortable” and “accidents happen”.Citation33,Citation34 Despite these concerns, there are quantified data illustrating that helmets are no “hotter” than the quintessential Australian “Akubra” or cowboy hat.Citation35 Consequently, part of this hesitancy for use may well be based upon historic and “image” based factors that perpetuate underlying behaviours. Notwithstanding such barriers, similar resistance to issues with bicycle helmet use in Australia has been demonstrated to be malleable to behavioural change and reductions in head injuries.Citation36

Cattle are known to become stressed and change their nature when handled, restrained, or forced into enclosed areas (e.g. cattle yards, trucks), increasing risk of injury.Citation37,Citation38 This study reinforces this rationale as 70% of cases were the result of being trampled whilst working in cattle yards, all of which were potentially attributable to changes in the animal behaviour. Given these numbers, key interventions to reduce mortality for persons working in cattle yards, especially older persons are critical. The removal of the hazard (cattle) is not reasonably practical, except for removing “rogue” individual animals. As such, engineering controls centring on safer yard design should be a high priority for action. For example, clear walkways to draw cattle through, self-latching gates, raised board walks, access, and escape ways.Citation39 Indeed, some jurisdictions have actively assisted with rebates for specific safety equipment (e.g. new cattle/sheep yards), to assist farmers in updating redundant and less safe facilities.Citation40–42 Improvements in yard design should then be supplemented by relevant animal handling training, although the finding that over 70% of cattle cases involve persons over 60 years of age, is at the very least, suggestive that these individuals already had extensive experience. More recently, there has also been some movement towards the use of PPE (e.g. chest guards and helmets) in cattle yards for corporate cattle operations.

International research indicates when workers are properly trained to work with these potentially dangerous animals (handling, recognition of behavioural and danger signs and mechanisms to avoid), it can reduce the incidence of injury.Citation10 While there is no definitive evidence to support this in Australia, it is reasonable to believe appropriate training has the potential to reduce the incidence of injury. Nevertheless, it must be emphasised that training is one of the lower levels of health and safety protection, therefore higher levels of control should be explored to eliminate or minimise the risk, with training being an additional component that assists with enhancing safety. Unfortunately, due to limited information in coronial records pertaining to competency/training of the deceased persons, this information could not be ascertained.

In terms of involvement of other animals (camel, deer, sheep), it is clearly due to the size, nature, and weight of the animal. Consequently, as these are to some extent comparable to horses and cattle, higher levels of safety within the Hierarchy of Controls should be a priority when handling these animals. Additionally, while encounters with native animals such as snakes and spiders are almost inevitable in an Australian context, appropriate emergency preparedness including suitably equipped first-aid kits and the provision of training will ameliorate negative outcomes. Meanwhile, other native animals, e.g. bees and wasps, can result in anaphylactic reactions. Where persons are already known to be at-risk of anaphylaxis, suitable emergency preparations must be available (i.e. EpiPen – adrenalin injections),Citation43 along with training for co-workers in how to use the devices if required.

As indicated in this assessment, those 60 years and older account for almost half (46%) of all deaths. These findings support existing data in Australia and elsewhere, illustrating older farmers are at increased risk.Citation5,Citation17,Citation44 It may be suggested that normal physiological and cognitive changes that are associated with the ageing process underpin these incidents.Citation45 Consequently, as farmers are working beyond normal retirement age and the average age of the workforce continues to increase,Citation46 a preventative focus targeting older farmers is required to address the impact on this cohort.

The strength of this study is that it draws on the national coronial data set, which is the gold standard source of Australian data capturing all animal-related deaths in the period. While there are a small number of cases yet to be finalised by a coroner in the database (4%), these missing data are relatively minimal and are likely to have negligible impact on the interpretations made. Although crude numbers of incidents can be accurately displayed, the lack of a suitable denominator to provide robust rates means that findings should be treated with caution. Specifically, it is impossible to determine with any validity the number of persons exposed to animals or the extent (hours) of exposure. Relatedly, it is also important to recognise the overall reduction could be influenced by changes in practices over the past 20 years (i.e. horses have been frequently replaced by other vehicles for use in mustering cattle and sheep). Consequently, the decrease in horse-related cases may well have been offset by an increase in the use of vehicles (and associated deaths/injuries). Finally, reports made by State Work Health and Safety agencies on work-related incidents are not contained within the electronic NCIS database. If such reports could be accessed this may assist with more definitive statements on competency/training of a rider or animal handler.

Overall, the data indicate a reduction in animal-related fatal incidents in the 20-year period, however horses and cattle continue to be the leading agents. In addition, the significant representation of older persons in these data requires attention. As local and export livestock markets increase and drought conditions ease across Australia, it is timely to revitalise engagement of safety regulators and agricultural industries to reduce animal-related deaths.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere appreciation to the staff within the National Coronial Information System for their assistance with case identification and clarifying case details.

Our thanks are extended to the staff of the National Coroners Information System for on-going assistance with the coronial records.

Disclosure statement

There are no issues to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Fragar L. Managing Beef Cattle Production Safety. Kingston, ACT: Australian Centre for Agricultural Health and Safety; 2005.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Fatal occupational injuries for selected industries, 2015-19 Washington2021 [ Available from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cfoi.t04.htm accessed 6 November 2021.

- Worksafe New Zealand. Summary of Fatalities Wellington: Worksafe NZ; 2021 [ Available from: https://data.worksafe.govt.nz/graph/summary/fatalities accessed 25March 2022.

- Health and Safety Executive. Fatal injuries in agriculture, forestry and fishing in Great Britain London: HSE; 2021 [ Available from: https://www.hse.gov.uk/agriculture/pdf/agriculture-fatal-injuries-2021.pdf accessed 17 October 2021.

- Cheng Y. Indiana farm fatality summary with historical comparisons. J Agric Saf Health 2021. 2016;26(3):105–119. doi:10.13031/jash.13635.

- Dogan K, Demirci S Livestock-Handling Related Injuries and Deaths: IntechOpen; 2012 [ Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/40418 accessed 15 March 2022.

- Safe Work Australia. Priority Industry Snapshot: Agriculture. Available from. Canberra: SWA; 2018. https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/doc/agriculture-priority-industry-snapshots-2018. accessed 10 October 2021.

- Damroth K, Damroth R, Chadhart A, et al. Farm Injuries: animal most common, machinery most lethal: an NTDB study. Am Surg. 2019;85(7):752–756. doi:10.1177/000313481908500737.

- Rhind J, Quinn D, Cosbey L, et al. Cattle‑related Trauma: a 5‑year retrospective review in a adult major Trauma center. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2021;14(2):86–91. doi:10.4103/JETS.JETS_92_20.

- Watts M, Meisel E, Densie I. Cattle-related trauma, injuries and deaths. Trauma. 2013;16(1):3–8. doi:10.1177/1460408613511387.

- Franklin R, Mitchell R, Driscoll T, et al. Farm-Related Fatalities in Australia. Moree: ACAHS, NOHSC and RIRDC; 2000.

- Bureau of Meterology. 122 years of Australian rainfall Canberra2022 [ Available from: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/history/rainfall/accessed 16 February 2022 2022.

- National Coroners Information System. NCIS Home Page Melbourne2020 [ Available from: http://www.ncis.org.au/accessed 13 April 2022.

- World Health Organisation. International Classification of Disease - Revision 10. Geneva: WHO; 1990.

- Lower T, Temperley J. A review of Australian farm tractor fatalities 2001-2016. Journal of Health, Safety and Environment. 2018;34:47–58.

- Lower T, Monaghan N, Quads MR. Farmers 50+ Years of Age, and Safety in Australia. Safety. 2016;2(2):12. doi:10.3390/safety2020012.

- Monaghan N, Lower T, Rolfe M. Fatal incidents in Australia’s older farmers (2001-2015). J Agromedicine. 2017;22(2):100–108. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2017.1282907.

- Herde E, L T. Farm Injury Optimal Dataset Version 2.1. Moree: Australian Centre for Agricultural Health & Safety; 2013.

- Lower T, Peachey K, Rolfe M. Farm-related injury deaths in Australia (2001-20. Aust J Rural Health 2022. doi:10.1111/ajr.12906.

- Henley G, Harrison J Hospitalised farm injury, Australia, 2010-11 to 2014-15. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2018 [ Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/injury/hospitalised-farm-injury-australia-2010-11-2014-15/contents/table-of-contents accessed 5 March 2022.

- Bureau of Meteorology. Annual climate statement 2017 2018 [ Available from: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/current/annual/aus/2017/accessed 17 February 2022.

- Bureau of Meteorology. Annual climate statement 2018 2019 [ Available from: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/current/annual/aus/2018/accessed 17 February 2022.

- Bureau of Meteorology. Annual climate statement 2019 2020 [ Available from: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/current/annual/aus/2019/accessed 17 February 2022.

- Bureau of Meteorology. Annual climate statement 2020 2021 [ Available from: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/current/annual/aus/2020/accessed 17 February 2022.

- Canadian Agricultural Injury Reporting. Agriculture-Related Fatalities in Canada Edmonton Alberta: CAIR; 2016 [ Available from: https://www.casa-acsa.ca/wp-content/uploads/CASA-CAIR-Report-English-FINAL-Web.pdf accessed 6 April 2022.

- Herde E, Lower T. Non-intentional farm injury fatalities in Australia, 2003–2006. NSW Public Health Bull. 2012;23(2):21–26. doi:10.1071/NB11002.

- Safe Work Australia. How to manage work health and safety risk Canberra: SWA; 2011 [ Available from: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1702/how_to_manage_whs_risks.pdf accessed 27 March 2022.

- Safe Work Australia. Model Work health and safety regulations Canberra: SWA; 2019 [ Available from: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/doc/model-whs-regulations accessed 17March 2022.

- Australian Centre for Agricultural Health & Safety. Horses on Farm. Moree: ACAHS; 1994.

- WorkSafe New Zealand. Riding horses on farms - good practice guidelines Wellington: Worksafe NZ; 2017 [ Available from: https://www.worksafe.govt.nz/topic-and-industry/agriculture/working-with-animals/horses/riding-horses-on-farms-gpg/accessed 27 March 2022.

- NSW Department of Primary Industries. Commonsense with horses Sydney: NSWDPI; 2006 [ Available from: https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/animals-and-livestock/horses/management2/commonsense-with-horses accessed 13 April 2022.

- Lower T, T J. Farm safety - time to act. Health Promot J Austr. 2018;29(2):167–172. doi:10.1002/hpja.166.

- Government of Western Australia. Station hands riding horses without wearing safety helmets Perth: department of mines industry regulation and safety; 2020 [ Available from: https://www.commerce.wa.gov.au/publications/safety-alert-062020-station-hands-riding-horses-without-wearing-safety-helmets accessed 13 March 2022.

- Haigh L, Thompson K. Helmet use amongst equestrians: harnessing social and attitudinal factors revealed in online forums. Animals. 2015;5(3):576–591. doi:10.3390/ani5030373.

- Taylor A, Caldwell R, Dyer R. The physiological demands of horseback mustering when wearing an equestrian helmet. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008;104(2):289–296. doi:10.1007/s00421-007-0659-5.

- Olivier J, Boufous S, Grzebieta R. The impact of bicycle helmet legislation on cycling fatalities in Australia. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(4):1197–1203. doi:10.1093/ije/dyz003.

- Grandin T. Assessment of stress during handling and transport. J Anim Sci. 1997;75(1):249–257. doi:10.2527/1997.751249x.

- Grandin T, Shivley C. How farm animals react and perceive stressful situations such as handling, restraint, and transport. Animals (Basel). 2015;5(4):1233–1251. doi:10.3390/ani5040409.

- Fragar L, Temperley J Cattle handling safety - a practical guide Moree: Australian Centre for Agricultural Health and Safety; 2015 [ Available from: https://aghealth.sydney.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Cattle-handling-Safety-Guide-A-Practical-Guide.pdf accessed 26 February 2022.

- Safework NSW. Small business rebate 2015 [ Available from: http://www.safework.nsw.gov.au/health-and-safety/how-we-can-help/small-business-rebates accessed 7 March 2022.

- WorkCover NSW. NSW sheep & beef cattle industry action plan 2013-2014. Working together to improve safety in the sheep and beef cattle farming industry Sydney: WorkCover NSW; 2013 [ Available from: http://www.workcover.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/15298/sheep-and-beef-cattle-action-plan-4516.pdf accessed 7 April 2022.

- WorkSafe Tasmania. Primary producer safety rebate scheme. Hobart: WorkSafe Tas; 2021 [ Available from: https://worksafe.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/631302/Guidelines-for-Primary-Producer-Safety-Rebate-Scheme.pdf accessed 7 March 2022.

- Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy. How to give EpiPen 2021 [ Available from: https://www.allergy.org.au/hp/anaphylaxis/how-to-give-epipen accessed 14 April 2020.

- Walker J, Lower T, Peachey K. Comparison of severe on-farm injuries to older and younger persons in New South Wales (2012-2016). Aust J Rural Health. 2021;29(3):429–434. doi:10.1111/ajr.12716.

- Harada C, Natelson Love M, Triebel K. Normal cognitive aging. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(4):737–752. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2013.07.002.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Agricultural commodities 2017-2018. 2019 [ Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/7121.0 accessed 7 April 2022.