?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Objective

Measuring attitudes of farmers to safe farming practices using quantitative causal relationship approaches is central to improving understanding of (un)safe practices. This knowledge is important in the development of effective farm safety interventions. However, the accuracy of quantitative attitudinal studies in explaining farmers’ decision-making faces a potential measurement challenge, i.e. a high level of optimism bias. In this paper, we present research that develops and tests farm safety attitudinal questions that are framed around “real-life” farming practices with the objective of reducing optimism bias.

Methods

We apply construal level theory (CLT) to support the design of vignettes that reflect common risk scenarios faced by farmers. Applying qualitative analysis of 274 fatal farm incidents that occurred in Ireland between 2004 and 2018 we identify the occupational behaviors (what farmers do), social (who are farmers), spatial (where farming takes place), and temporal (when farming happens) dimensions of risks resulting in most deaths. The results informed subsequent co-design activities with farm safety experts and farm advisors to develop “real-life” scenarios, attitudinal questions, and response options. The questionnaire was piloted and subsequently implemented to collect data from a sample of 381 farmers with either tractors or livestock. The results of the survey were compared to previous attitudinal research on farmer’s attitudes to safety in Ireland to establish if there was as follows: i) increased variance in the responses, and ii) a statistically significant difference in the attitudes of respondents compared to the results reported in previous studies.

Results

The findings established that when farmers were provided with real-life scenarios, their responses were less optimistic and more varied, i.e. there was a greater range of responses, compared to previous studies.

Conclusion

Applying CTL to the development of attitudinal survey instruments anchors attitudinal questions within farming specific occupational, social, spatial, and temporal contexts. The use of vignettes that draw on real-life scenarios offers the potential for improved design of surveys that seek to understand farmer/worker practices. The results suggest that this approach can improve the measurement of attitudes to farm safety.

Introduction

Farming is a dangerous occupation and farmers typically engage in risky behavior resulting in high levels of occupational injuries and accidents.Citation1,Citation2 A common response to this challenge is to raise awareness of occupational risks associated with farming through communication, educational, and training initiatives.Citation1–4 There is evidence, however, that increased awareness does not result in reduced risk taking.Citation2,Citation5–7 In response, research has sought to understand attitudes to safety as these are considered a key intrinsic motivator influencing adoption or non-adoption of farm safety behaviors.Citation2,Citation8,Citation9 For the purpose of this paper, attitudes refer to the degree to which an individual thinks a behavior is important, favorable/good or vice versa. There is a growing body of quantitative, cross-sectional research utilizing socio-cognition and psychological theories such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Health Belief Model (HBM) to examine Farm Health and Safety (FHS) attitudes and behaviors.Citation1,Citation10,Citation11 There are, however, concerns regarding the reliability and validity of the data collected using these approaches.Citation2,Citation12,Citation13 It is questionable whether such methods capture the depth of farmers’ attitudes, perceptions, beliefs, norms, and values, as well as their less optimistic views and opinions.Citation1,Citation2,Citation14–17 In particular, several studies have raised concerns regarding the presence of optimistic bias when investigating FHS issues.Citation2,Citation13,Citation18,Citation19 This body of research indicates that, in general, farmers think FHS is important, and they plan on being safe in the future.Citation2,Citation5,Citation8,Citation14 Qualitative studies have, however, found that when discussing farm safety, farmers explain they take risks, because they perceive safety actions as not always necessary or possible.Citation5,Citation6,Citation20 Such differences between expressed attitudes to general questions regarding safety and more contextually rich discussions of the same issue can result in inaccurate responses with general attitudinal questions and, consequently, erroneous study conclusions.Citation2 This, in turn, raises important methodological questions regarding how to quantitatively measure attitudes relating to potentially sensitive issues, such as the non-adoption of farm safety practices. The aim of this paper is to introduce an approach using vignettes that draw on construal level theory (CLT) to reduce optimism bias and improve measurement of attitudes to farm safety.

According to CLT, psychological distance pertains to the extent to which an individual, for instance a farmer, perceives a phenomenon as closely related to their occupation (what they do), its timing (when it occurs), its location (where it happens), and its societal context (in which social context it occurs).Citation21 Trope and LibermanCitation21 define psychological distance as the distance from an individual’s perception of self in the “here and now”, to how their perception can change based on different ways in which an object or event might be removed from that point in time, in space (physical and human geography), in social distance. Trope and LibermanCitation21 also argue that increasing psychological distance, i.e., moving from direct experience to more abstract conceptualization of an issue, impacts on prediction, preference, and action. This has important implications for the design of studies that seek to understand attitudes. If the design, including framing, of questions and response options are generic or abstract, persons may experience cognitive challenges when assessing both questions and response options. Therefore, they may not consider the issue to be one that impacts on them specifically.Citation2,Citation22 It also opens up the possibility for optimism bias, specifically “self-deception” that may be unconscious, namely, where the individual seeks to maintain a positive self-concept. Finally, if psychological distance is not adequately considered, there may be a tendency on the part of respondents to overestimate the likelihood of positive events and underestimate the likelihood of negative events resulting in optimism bias.Citation23

Though commonly included within attitudinal surveys focused on farm safety, generic statements along the lines of “farm safety is important” may be problematic if a specific context is not developed beforehand.Citation21 In the absence of such framing, such as “farming safely is more important than making a profit this year”, the respondent is presented with a normative statement that can lead to what they perceive as the optimistic answer. Inclusion of temporal aspects, geographical proximities, or social and occupational factors when framing the question can reduce optimism bias in self-administered questionnaires.Citation24

A body of research has developed in recent years applying vignettes to better understand farm safety behavioursCitation25–27 Utilizing vignettes, namely short evocative stories, as a method to depict real-life scenarios for assessing socio-cultural and psychological constructs, including “attitude”, has been suggested as an effective tool for obtaining a more authentic measure of attitudes.Citation28 Vignettes are applied in surveys to present a scenario that may outline particular practices, events or behaviors within specific social, cultural, and occupational contexts that frame questions in ways that reduce physiological distance. Respondents are then asked to answer questions that assess socio-cultural and psychological constructs based on their assessment of the scenario presented.Citation28 Vignettes are employed to provide respondents with a more detailed and easily understandable portrayal of a situation in which they might need to make a decision or take an action.Citation28 Whilst vignettes have been applied to assess “farm safety”, to the best of our knowledge, there is no evaluation of differences between the level of vignette-based and general FHS attitudes from farmers in the same context. To assess if there is a difference between a vignette-based approach and conventional attitudinal questions, it is important to consider not only the overall attitudinal score but also the variability in responses. Greater variability may point to the effect of reducing psychological distance. Almost, all previous Irish studies have reported positive and less variated FHS attitude, indicating the possibility of optimism bias.Citation5,Citation9,Citation19,Citation29–32 Therefore, two assumptions are tested in this study:

H1:

Vignette-based FHS attitude questions, which present trade-offs or risky situations where farmers may perceive closer psychological distances, will elicit more varied responses.

H2:

The overall attitudinal score estimated through vignette-based FHS questions will be lower than those previously recorded in general FHS attitudinal surveys reported by past studies in Ireland

To this end, the present study introduces an approach that seeks to reduce optimism bias and improve the accuracy of the attitudinal questions through the use of “real-life” farm safety vignettesCitation28 before comparing the results of our work to other studies that have been carried out in Ireland. We utilize a mixed qualitative and quantitative research approach, the aim of which is to design and validate vignettes as a means of quantitatively measuring attitudes in a more contextually rich manner. The study addresses the following objectives to support testing of the study hypotheses:

Identify the actions and behaviors leading to farm work-related fatal incidents through an analysis of qualitative content describing such incidents.

Utilize the results of the qualitative analysis of fatal incidents to inform the co-design of vignettes and associated questions with input from a farm safety expert group.

To evaluate the results of vignette-based attitudes and compare them to previously reported FHS attitudes in the same context.

Methods

Designing the vignettes

Inductive content analysis of short descriptions

To design vignettes that narrow the psychological distance of attitudinal questions for farmers, inductive content analysis using NVivo 11 (version 11.1.1) was undertaken on 274 qualitative descriptions of farm fatalities that occurred between 2004 and 2018.Citation33 To identify the key trade-off scenarios leading to farm-work related fatalities in Ireland, the content analysis was structured around primary questionsCitation33 addressing what was the primary cause of the fatality, an assessment of when and where the incident occurred and any associated behaviors, e.g., person did not secure gates or worked with a defective tractor. Each of the 274 qualitative descriptions consists of two or three short factual sentences reported by Irish Health and Safety Authority (HSA) inspectors that summarize their assessment of the fatal incident.Citation33 The lead author read through each assessment twice to familiarize themselves with the format and content.Citation33 In line with previous studies,Citation26,Citation34 open coding was applied to identify themes and sub-themes from qualitative data to support development of “real-life” scenarios that were subsequently used to develop vignettes. The meaning and content of each code was discussed, approved, and agreedCitation33 by a group consisting of the lead author, one researcher (co-author), two FHS specialists (one of whom is a co-author), and one the farm safety inspector.

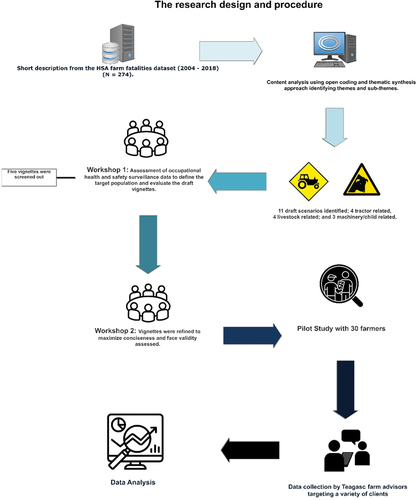

Developing the vignettes and identifying the target population

Drawing on the outcomes of content analysis, 11 stories/scenarios were initially designed that reflected the major themes and sub-themes. These data informed the development of 11 draft vignettes summarizing risks and risky behavior(s). Two expert group workshops were held. The first workshop involved farm advisors (n = 3), FHS specialists (n = 2), and social and behavioral science researchers (n = 2) with experience in farm safety behavioral research. This workshop drew on professional experience to assess occupational health and safety surveillance data to define the target population and evaluate the draft vignettes. Based on this assessment it was recommended that the target population should comprise farmers involved in tractor/machinery and livestock activities, such as beef, dairy, and mixed farming (with both bovine livestock and crops) as these enterprises account for most fatal farm incidents in Ireland.Citation35 This workshop also assessed the draft vignettes and provided recommendations regarding the inclusion/exclusion of each vignette and refinement of the final set of vignettes. To confirm the face validity of the vignettes, a second workshop was conducted with seven farm advisors. During this workshop, the vignettes were refined to maximize their conciseness and ensure the target group (farmers) easily understood them (). This group also considered the content validity of questions associated with each vignette and the response options. Further details describing this process are presented below ().

Design of questions and response options

To design attitudinal questions based on vignettes, we drew on the standard framework developed study and previous research. SPSS Version 21 by Colémont and Van den Broucke.Citation10,Citation36,Citation37 These ensured items (questions) were designed based on the conceptual definition of attitude. A bipolar 5-point Likert scale was used to quantify the attitudinal questions (completely disagree (1) to completely agree (5)).Citation36 To examine face validity, the qualitative assessment of vignettes and attitudinal questions was conducted through a qualitative face validity approachCitation38 by a panel of farm advisors (n = 8) who had not participated in designing the vignettes (first workshop). Qualitative face validity refers to the extent to which vignettes and questions measuring a specific construct, in our case “attitude”, are understandable by and appropriate to the target group.Citation38 Accordingly, vignettes and items measuring attitude were evaluated based on “feasibility, readability, consistency of style and formatting, and the clarity of the language used”,Citation39 first by the panel of FHS specialists and behavior/social science researchers who participated in the first workshop and then by a panel of farm advisors who participated in the second workshop. To evaluate the reliability of items measuring attitude, a pilot study was carried out among 30 farmers outside of the study sample. Cronbach’s Alpha was estimated at 0.84 which was greater than the acceptable cutoff point (>0.7).Citation40

Comparison with previous studies

For the purpose of this paper, our comparisons for vignette-based FHS attitude were with published cross-sectional studies, which reported general farm safety attitudinal results in Ireland.Citation5,Citation9,Citation19,Citation29–32 To ensure the comparability of attitudinal questions with different scales and to control potential measurement-scale bias, a simple Linear Scale Transformation (LST) techniqueCitation41 was applied to bring the scales of all questions (with different Likert scales) to the same range (0–100). LST is a rescaling technique of the ratings of “k-step primary rating scales to make comparable the results obtained by using primary scales with different numbers (k) of ratings”.Citation42 The LST technique applied the following equation:

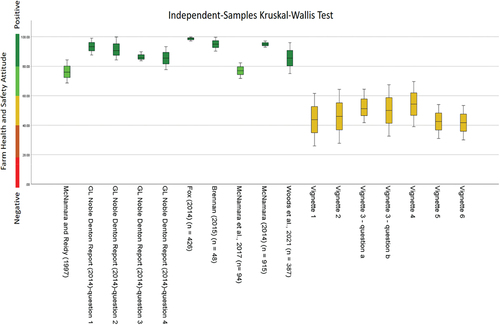

Y and X refer to the standardized value (post-transformation) and unstandardized value (pre-transformation), respectively. B and A pertain to the highest (100) and lowest (0) values of standardized attitude, respectively. a and b refer to the lowest and highest values of the pre-transformed attitude, respectively. To compare the level of attitudinal questions in the current study with previous Irish studies (H2), the Kruskal–Wallis H test was applied. The Kruskal–Wallis H test is the most appropriate statistical test to compare means while comparing more than two variables (e.g., attitudinal questions) with an ordinal scale or non-normal distribution.Citation43 Two assumptions for the use of the Kruskal–Wallis H test include non-normal distribution of variables and ordinal-scale variables, both of which were met.Citation43 Since all attitudinal questions from previous studies and the present one were measured using an ordinal scale (Likert scale), the Kruskal–Wallis H test was applied to examine if there is a significant difference between the level of vignette-based attitudinal questions (current study) and general farm safety attitudinal questions (previous studies) on average. Dunn’s test, as post-hoc pairwise comparison test, was conducted to illustrate whether the average attitudes reported in previous studies were significantly different from each other, to identify any significant differences between vignette-based FHS attitude questions, and lastly to highlight questions or studies that reported significantly different levels of attitude. Furthermore, this analysis was extended to compare the differences in attitude averages between the current study and previous research. SPSS Version 21Citation44 was used to perform the statistical analysis (). The average age of farmers and enterprise/type of farm (as two main background variables reported by previous studies) of the farmers participating in this study were compared with previous studies. This enabled us to consider if observed differences in average FHS attitudes were attributable to potential differences in the socio-demographic profiles of the respondents of the selected studies.

Participants and procedures

The target population of the study were farmers exposed to tractor/machinery-related and either dairy or beef livestock-related hazards/dangersCitation35 as these are the two major causes of fatalities in Ireland. These were the primary themes extracted from the evaluation of the qualitative descriptions of farm fatalities () and the focus of much of the input from experts and farm advisors participating in the workshops. Therefore, farmers from beef, dairy, and mixed farming enterprises (N = 99,741, 73.8% of all Irish farms)Citation45 formed the study population. Previous research has established that these enterprises record the highest levels of fatal injuries.Citation35,Citation46 To identify the minimum representative sample size of this cohort, the Krejcie and Morgan sampling equationCitation47 was applied. This resulted in a minimum sample of 348 farmers being identified as necessary to achieve a 95% confidence interval.

Two modes of data collection were applied: firstly, face-to-face interviews undertaken by farm advisors with a variety of clients and, secondly, completion of a self-administered questionnaire by farmers participating in education and training courses. None of the latter courses were focused on farm health and safety issues or topics. This approach was applied as a means of accounting for known bias issues associated with different modes of survey implementation.Citation24 To prevent any recruitment and study sample bias and obtain a higher response rate, we used a suitable stratified random sampling technique to ensure advisors surveyed farmers from three homogenous groups (leading, conventional, and traditional). Advisors were asked to randomly invite farmers with different levels of experience to complete the questionnaire. To enable advisors to collect data effectively, an online training seminar was organized for advisors supporting the data collection. Following the workshop, a comprehensive guideline document was also provided to advisors.

As it was not possible to select farmers participating in education and training courses to complete the questionnaire based on their level of experience, specific courses were targeted. This ensured that farmers of different ages, from different parts of the country with different types (size and intensity) of dairy, beef, or mixed enterprises were included as part of the sample. Taken together, this approach, i.e., the combination of face-to-face and self-administered questionnaires, resulted in 381 farmers fully completing the survey (response rate = 99.23%). This is higher than the acceptable response rate (60%<) for in-person surveys.Citation48 An attitudinal question associated with each vignette was presented after each vignette in the questionnaire.

Results

The findings of thematic analysis, providing a concise overview of qualitative research, and the outcomes of the workshop in designing vignettes are reported before presenting descriptive statistics of the study population. We also summarize the demographic characteristics of the samples used in previous studies. Finally, the results of the quantitative research, including the examination of the study hypotheses through the assessment of vignette-based FHS attitudes and comparisons between the level of vignette-based FHS attitudes and past studies, are presented.

Demographics of farmers surveyed in the current and previous studies

Prior to undertaking our analyses and to ensure there was no bias associated with our sampling technique, the socio-demographic profile of farmers, such as age, gender, and enterprise, was compared to that of the population of the Irish farmers’.Citation45 In general, the age profile of farmers surveyed in the current study was similar to the whole population (). Of 381 farmers in our study, 85.8% were male (n = 327) and 11.7% (n = 54) were female, with the majority of Irish farmers have been male in the whole population (86.6% male and 13.4% female).Citation45

Table 1. Evaluation and sampling vignettes.

Content analysis of short farm workplace fatality descriptions

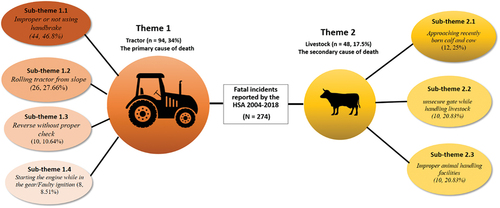

“Tractor” was identified as the most frequent term used in short descriptions of farm workplace fatality (94, 34%), followed by “livestock” (48, 17.5%) including cow (29, 8.03%) and bull (19, 5.84%). This formed the two major themes for our study.

Within the “Tractor” theme, the major sub-themes identified (): “Improper or not using handbrake” (44, 46.8%), followed by “rolling tractor from slope” (26, 27.66%), “reverse without proper check” (10, 10.64%), “starting the engine while in the gear/faulty ignition” (8, 8.51%), “entangled by uncovered PTO shaft” (5, 5.3%) (). “Approaching recently born calf and cow” (12, 25%), “unsecure gate while handling livestock” (10, 20.83%), “improper animal handling facilities” (10, 20.83%)’ were comprised major sub-themes in “livestock” theme ().

Refining vignettes (qualitative assessment of stories/scenarios)

Drawing on the findings of the content analysis, vignettes were developed that depicted trade-off scenarios encompassing “tractor” and “livestock” sub-themes. The vignettes sought to reduce psychological distances by framing them with reference to social, temporal, spatial, and occupational characteristics identified from the review of farm fatalities ().

To evaluate the vignettes, certain criteria were applied which encompassed factors such as “the frequency of occurrence/exposure” and “the resemblance of situations” described in the vignettes to actual farm conditions. These assessments are detailed in . Following evaluation, five vignettes were eliminated based on the assessments of a panel of experts, based on identifying the frequency and chance of exposure to such trade-off situations described in vignettes as either low or irrelevant to the majority of farmers in our study population (most vulnerable farm enterprises to tractor and livestock related fatal incidents). Ultimately, six vignettes (three machinery-related and three livestock-related) were selected (). Following on the second workshop, minor changes were made to the statements within each vignette, making sure that the terminology used was familiar to farmers and that the vignettes remained sufficiently concise ().

Farmers with beef, dairy, and mixed farming enterprises (with livestock and crops)Citation35 are the main cohorts of surveyed farmers in the current and each of the previous studiesCitation5,Citation9,Citation19,Citation29–32 (). These farming enterprises are the predominant types in Ireland, with 73.8% of all Irish farmers engaged in enterprises involving tractor and livestock-related hazards.Citation45

Table 2. The profile of farmers surveyed in the current and previous studies.

In terms of demographics, the age distribution of farmers in previous studies ranged from 18% to 43% under 44 years of age, 45–55 years (22% to 32%), and over 55 (31.2% to 57%) (). The age distribution of the respondents in the present study that of the whole population. This contrasts with BrennanCitation19 and Woods et al.Citation32 who reported data from a slightly younger profile farmers (). The age profile of farmers surveyed in McNamara and Reidy,Citation29 Fox,Citation30 and McNamaraCitation31 studies were not available. There was no difference on the average of standardized FHS attitude reported by all previous studies ().

Comparing results from measures using vignettes and generic attitudinal statements

Prior to comparing the results of this study to previous studies, we assessed whether the attitudinal scores reported in previous studies were significantly different from each other. These studies reported positive general FHS attitudes. A post-hoc pairwise comparison test established no statistically significant differences between the levels of general FHS attitude reported by all previous studies (P-value = 0.32) which ranged in sample size from 42 to 926 farmers (). This indicates that there was no association between the level of general FHS attitude and the study sample sizes (). Comparing between the current study and the published studies, we find that the results of the Kruskal–Wallis H test reveal a significant difference in the average FHS attitude (p value = 0.001). The respondents to the vignettes reported lower levels of vignette-based FHS attitudes (ranging from 41.7 to 54.3) in comparison with all previous studies (ranging from 76 to 98.8) (; ). The Standard Deviation (SD) for vignette-based FHS attitudes ranged from 11.5 to 18.3. Conversely, a low level of standard deviation was reported in general FHS attitudes from all previous studies (; ). Notably, the highest bound of the vignette-based attitude is still lower than the lowest bound of the general FHS attitude (; ). Therefore, H1 is accepted namely: vignette-based FHS attitude questions that reduce psychological distances elicited more realistic and varied responses. The post-hoc pairwise comparison test highlighted a significant difference between all vignette-based questions and all general FHS questions reported by past studies ( and ). Consequently, H2 is confirmed, namely, there is a significant difference between the level of vignette-based FHS attitude and general FHS attitude reported by past studies in Ireland.

Table 3. Comparison of the level of FHS attitude in the current study with previous Irish studies-.

Discussion

Why farmers respond to vignettes and generic attitudinal statements in different ways?

Previous studies completed in Ireland measured attitudes in a general sense, i.e., they did not present “real-life” scenarios. These studies reported significantly positive attitudes toward safety (ranging from 76 to 95).Citation5,Citation9,Citation19,Citation29–32 These studies conclude that FHS, in general, is considered (by farmers) as important, favorable, good, or a priority. There was limited variance in the attitudinal scores reported in these studies, indicating that the majority of respondents held positive attitudes to farm safety with little variation in the views/thoughts. This suggests that the common approach, i.e., the use of generic attitudinal statements, is consistent with producing broadly comparable results despite variation in the composition, size, and time when the data were collected. In contrast to these studies, our findings indicate farmers reported significantly lower scores in response to vignette-based FHS attitude questions. The obvious conclusion is farmers respond differently to questions that frame the issue by providing a context they understand and with which they identify. Context rich vignettes reduce psychological distance. The finding that there is greater variation in responses to these questions suggests more considered responses to the questions compared to more generic framings. Thus, vignette-based FHS attitude may be a more realistic and a better predictor or a factor explaining FHS actions compared with general measures of FHS attitude.

The use of vignettes provides farmers with a clearer understanding of risky situations, prompting them to assess the potential implications and consider the potential risks. This judgment stands in stark contrast to the evaluation of FHS as a generic concept, which lacks a clear picture of what, how, when, and where a safety action may be considered important or unimportant, or a priority or not. Consequently, this leads farmers to maintain a generally positive outlook, regardless of the potential risks. It is evident that when attitudes are measured generally, farmers generally perceive a subjective and abstractCitation21 feeling towards the concept of safety, leading them to report more positive attitudes. However, when asked vignette-based attitudinal questions, respondents expressed different views and attitudes that align more with the findings of qualitative studies on farm safety attitudes.Citation2,Citation5,Citation26 These findings are consistent with studies highlighting that farmers may view safety as generally important but not a priority or something that is important, or from their perspective, not practical.Citation2,Citation5,Citation26,Citation49

In contrast to the findings of many qualitative studies, research applying quantitative approaches has found that attitudes to safety amongst farmers is, on average, positive.Citation5,Citation8,Citation9,Citation19,Citation29–32 This does not necessarily mean that “attitude” is irrelevant or not a determinant of actions. It suggests approaches that adopt a targeted approach to risk reduction and management are more likely to resonate with farmers compared to generic awareness raising approaches. Instead, it is necessary to support farmers to cultivate and maintain FHS attitude that encompasses not only safety in a general sense but also in specific FHS actions, for example preparing for handling livestock or regularly maintaining tractors and machinery.

Applying vignettes as an effective tool in quantifying realistic farm safety attitudes

This study demonstrates that while farm safety is generally recognized as an important aspect of farm management,Citation2,Citation5,Citation9,Citation29,Citation31,Citation32 it may not be prioritized or deemed essential in many trade-off situations.Citation5,Citation6,Citation8,Citation26 A consequence of this finding may be the occurrence of numerous, potentially avoidable, farm workplace fatal and non-fatal injuries. This finding also suggests that asking generic and positive attitudinal questions may result in measuring general FHS assessment, which may not be relevant to a specific farm safety action and thus not a predictor of such action despite showing the general views of farmers about FHS. Consequently, to enhance our understanding of farm safety decision-making and the influence of attitudes on such actions, it is crucial to design quantitative research studies, such as cross-sectional studies, that incorporate scenario or situation-based attitudinal questions. These questions should enable farmers to form a more detailed and accurate perception of the importance or priority of an action that is socially, temporally, and geographically relevant to their real-life situations. Using vignettes based on common trade-off farm work-related scenarios can lead to a more precise and context relevant measurement of attitude. A vignette-based attitude can reflect the extent to which individual farmers think safety actions are important or a priority while being exposed to a risky situation, which is in line with the findings of qualitative studies that report negative FHS specific attitudes.Citation5,Citation6,Citation20 Certainly, vignettes can prove instrumental in capturing attitudes that align with qualitative findings, particularly when assessing the connection between FHS attitudes and safety-related actions in cross-sectional quantitative studies employing a causal relationship approach. Additionally, these attitudes can be evaluated within quantitative impact assessment studies examining the effects of policies, training programs, initiatives, and interventions on improving attitudes and behaviors related to farm safety.

Limitations

One of the key limitations of our analysis was the inability to compare results associated with behavior or intention to those of published studies. This is a consequence of previous research not considering socio-psychological concepts, such as values, perceptions, or beliefs. It is essential to consider such constructs in future studies to determine if their levels differ when employing vignettes to measure those constructs. A further limitation is the focus of the comparative analysis on Irish studies. There is a need for a broader comparison of attitude measurements using the proposed approach in this study to international studies to determine if the level of optimism bias decreases in different regional or national contexts. Lack of measuring general FHS attitude was another limitation of the present study. Whilst this was not the focus of this study, the inclusion of a generic attitudinal question similar to those used in previous studies would have been sensible and invaluable to the analysis presented above.

Conclusion

The findings of this study illustrate that the use of vignettes can offer deeper insights and, hence, improve understanding of FHS attitudes and ultimately FHS decision-making. Framing attitudinal questions within real-life scenarios related to FHS that resonate with the social, temporal, and spatial aspects of farmers’ work context reduce the psychological distance of the issue being assessed. Consequently, respondents are more realistic when considering their responses.

This study drew on a database of brief descriptions of incidents in farm workplaces that resulted in fatal injuries to identify key safety challenges and, by working with farm safety experts and farm advisors, developed the vignettes. Whilst this type of resource is unlikely to be available in many countries, it may be possible to use alternative sources including medical reports, coroner reports, or media coverage to identify safety scenarios. Based on the invaluable input received from experts and specialists in FHS, we strongly advise their inclusion in the development of data collection instruments that seek to measure farmer attitudes. Our experience in conducting the study highlighted the significance of expert input into the development of the vignettes, questions, and response options.

The insights derived from the approach developed through this research increases understanding of the difference between general and more specific measures of FHS attitudes to workplace practices. This understanding is important in explaining the persistence of farm injuries to farm safety stakeholders and policy makers and highlights that awareness raising by itself is unlikely to change attitudes and, consequently, behaviors. This is particularly the case where farmer are self-employed and their work-related thoughts and actions are predominantly under their own control. The knowledge gained from this study is also critical to the development of interventions including FHS policies, training programs, and behavioral change interventions that directly target not just the risks but also the contexts within which risk-taking is learned and enacted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mohammadrezaei M, Meredith D, McNamara J. Subjective norms influence advisors’ reluctance to discuss farm health and safety. J Agric Educ Extension. 2022;29(5):1–25. doi: 10.1080/1389224X.2022.2125410.

- O’Connor T, Kinsella J, O’Hora D, McNamara J, Meredith D. Safer tomorrow: Irish dairy farmers’ self-perception of their farm safety practices. J Safety Res. 2022;82:450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2022.07.012.

- DeRoo LA, Rautiainen RH. A systematic review of farm safety interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(4 Suppl):51–62. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00141-0.

- O’Connor T, Meredith D, McNamara J, O’Hora D, Kinsella J. Farmer discussion groups create space for peer learning about safety and health. J Agromedicine. 2021;26(2):120–131. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2020.1720882.

- Noble Denton GL. Determining underlying psycho-social factors influencing farmers’ risk related behaviours (both positively and negatively) in the Republic of Ireland. Ireland; Final report; prepared for HSA (Ireland). Report Number 4002015-2014.

- Sorensen JA, May JJ, Paap K, Purschwitz MA, Emmelin M. Encouraging farmers to retrofit tractors: a qualitative analysis of risk perceptions among a group of high-risk farmers in New York. J Agric Saf Health. 2008;14(1):105–117. doi:10.13031/2013.24127.

- Elkind PD. Perceptions of risk, stressors, and locus of control influence intentions to practice safety behaviors in agriculture. J Agromedicine. 2007;12(4):7–25. doi: 10.1080/10599240801985167.

- Manolova H, Jack C, Angioloni S, Ashfield A. Farm safety: a study of young farmers’ awareness, attitudes and behaviors. J Agromedicine. 2023;28(3):576–586. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2023.2180124.

- McNamara J, Griffin P, Kinsella J, Phelan J. Health and safety adoption from use of a risk assessment document on Irish farms. J Agromedicine. 2017;22(4):384–394. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2017.1356779.

- Colémont A, den Broucke S V. Measuring determinants of occupational health related behavior in Flemish farmers: an application of the theory of planned behavior. J Safety Res. 2008;39(1):55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2007.12.001.

- Caffaro F, Lundqvist P, Micheletti Cremasco M, Nilsson K, Pinzke S, Cavallo E. Machinery-related perceived risks and safety attitudes in senior Swedish farmers. J Agromedicine. 2018;23(1):78–91. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2017.1384420.

- Sorensen JA, Jenkins PL, Emmelin M, et al. The social marketing of safety behaviors: a quasi-randomized controlled trial of tractor retrofitting incentives. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(4):678–684. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.200162.

- Weinstein ND, Lyon JE. Mindset, optimistic bias about personal risk and health‐protective behaviour. Br J Health Psychol. 1999;4(4):289–300. doi: 10.1348/135910799168641.

- Murphy M, O’Connell K. Farm deaths and injuries: changing Irish farmer attitudes and behaviour on farm safety. 2017. Dept. of Management & Enterprise Conference Material [online]. https://sword.cit.ie/dptmecp/2.

- Gibbs JL, Walls K, Sheridan C, et al. Evaluation of self-reported agricultural tasks, safety concerns, and health and safety behaviors of young adults in U.S. Collegiate agricultural programs. Safety (Basel). 2021;7(2):10.3390/safety7020044. doi: 10.3390/safety7020044.

- Caponecchia C. It won’t happen to me: an investigation of optimism bias in occupational health and safety. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2010;40(3):601–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00589.x.

- Shepperd JA, Klein WM, Waters EA, Weinstein ND. Taking stock of unrealistic optimism. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2013;8(4):395–411. doi: 10.1177/1745691613485247.

- Pollock KS, Fragar LJ, Griffith GR. Occupational health and safety on Australian farms: 3 safety climate, safety management systems and the control of major safety hazards. Australian Farm Bus Manag J. 2016;13:18–35. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.284950.

- Brennan C. Exploring the Impact of a Farm Safety Intervention Programme in Ireland Examining farmer’s Behaviour Towards Farm Safety-A Study of the Farm Safety Mentor Programme. Galway: National University of Galway; 2015.

- Shortall S, McKee A, Sutherland LA. Why do farm accidents persist? Normalising danger on the farm within the farm family. Sociol Health Illn. 2019;41(3):470–483. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12824.

- Trope Y, Liberman N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance [published correction appears in Psychol Rev. 2010 Jul;117(3): 1024]. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):440–463. doi: 10.1037/a0018963.

- Stavrinos D, Heaton K, Welburn SC, McManus B, Griffin R, Fine PR. Commercial truck driver health and safety: exploring distracted driving performance and self-reported driving skill. Workplace Health Saf. 2016;64(8):369–376. doi:10.1177/2165079915620202.

- Sharot T. The optimism bias. Curr Biol. 2011;21(23):R941–R945. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.030.

- Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 4th ed. Michigan, The USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2014.

- Irwin A, Poots J. Investigation of UK Farmer Go/No-go decisions in response to tractor-based risk scenarios. J Agromedicine. 2018;23(2):154–165. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2017.1423000.

- Tone I, Irwin A. Watch out for the bull! farmer risk perception and decision-making in livestock handling scenarios. J Agromedicine. 2022;27(3):259–271. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2021.1920528.

- Irwin A, Tone IR, Sedlar N. Developing a prototype Behavioural marker system for farmer non-technical skills (FLINTS). J Agromedicine. 2023;28(2):199–207. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2022.2089420.

- Vanclay F. Regional Studies. The Potential Application of Qualitative Evaluation Methods in European Regional Development: Reflections on the Use of Performance Story Reporting in Australian Natural Resource Management. 2015; 49(8): 1326–1339. doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.837998.

- McNamara J, Reidy K. Survey of Safety and Health on Irish Farms. Dublin, Ireland: Teagasc; 1997:61.

- Fox M. Advisory Methods to Improve farmers’ Engagement in Farm Health and Safety Adoption. Ireland: University College Dublin; 2014.

- McNamara JG. A Study of the Effectiveness of Risk Assessment and Extension Supports for Irish Farmers to Improve Farm Safety and Health Management. Ireland: University College Dublin; 2015.

- Wood N, Mohammadrezaei M, McGee M, et al. Farm safety attitudes and behaviours of livestock farmers in Ireland. BeSafe international seminar; 2022; Dublin, Ireland.

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

- Irwin A, Poots J. The human factor in agriculture: an interview study to identify farmers’ non-technical skills. Saf Sci. 2015;74:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2014.12.008.

- Mohammadrezaei M, Meredith D, McNamara J. Beyond age and cause: a multidimensional characterization of fatal farm injuries in Ireland. J Agromedicine. 2023;28(2):277–287. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2022.2116138.

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior: frequently asked questions. Hum Behav And Emerging Technologies. 2020;2(4):314–324. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.195.

- Ajzen I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Amherst; 2006.

- Engel L, Bucholc J, Mihalopoulos C, et al. A qualitative exploration of the content and face validity of preference-based measures within the context of dementia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):178. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01425-w. Published June 11, 2020.

- Taherdoost H. Validity and reliability of the research instrument; how to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research. How To Test The Validation Of a Questionnaire/Survey In a Res. August 10, 2016. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3205040.

- Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53–55. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd.

- Göb R, McCollin C, Ramalhoto MF. Ordinal methodology in the analysis of likert scales. Quality & Quantity. 2007;41(5):601–626. doi: 10.1007/s11135-007-9089-z.

- Kalmijn W. Linear scale transformation. In: Michalos A, ed. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer; 2014:3627–3629.

- Ostertagová E, Ostertag O, Kováč J. Methodology and application of the Kruskal-Wallis test. AMM. 2014;611:115–120. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.611.115.

- Spss I. Statistics for Windows Version, 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; released. 2020.

- Central Statistics Office. Census of Agriculture 2020 – Preliminary Results. Dublin, Ireland: Central Statistics Office; 2020.

- Meredith D, Mohammadrezaei M, McNamara J, O’Hora D. Towards a better understanding of farm fatalities: identification and estimation of farming fatality rates. J Agromedicine. 2023;28(2):239–253. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2022.2113196.

- Krejcie RV, Morgan DW. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ Psychol Meas. 1970;30(3):607–610. doi: 10.1177/001316447003000308.

- Nulty DD. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Educ. 2008;33(3):301–314. doi:10.1080/02602930701293231.

- Barnes KL, Rudolphi J, Kivirist L, Bendixsen CG. Childhood agricultural injury prevention among organic farmer mothers. J Agromedicine. 2021;26(2):273–277. doi:10.1080/1059924X.2020.1744495.