ABSTRACT

This article argues that to capture Russia’s influence abroad, one needs to comprehend the country’s “gray diplomacy” as a neoliberal realm open to individual initiatives. We define “entrepreneurs of influence” as people who invest their own money or social capital to build influence abroad in hopes of being rewarded by the Kremlin . We test this notion by looking at both famous and unknown entrepreneurs of influence and their digital activities. We divide them into three broad categories based on their degree of proximity to the authorities: the tycoons (Yevgeny Prigozhin and Konstantin Malofeev), the timeservers (Alexander Yonov and Alexander Malkevich), and the frontline pioneers (the Belgian Luc Michel). An analysis of the technical data documenting their online activities shows that some of these initiatives, while inscribed into Moscow’s broad aspirations to great powerness, are based on the specific agendas of their promoters, and thus outlines the inherent limits of Moscow’s endeavors.

Introduction

The Russian political regime is often represented as a pyramid, with an omniscient Putin at the top making all the decisions, which then trickle down the administrative ladder. A more precise pyramidal model depicts power circles at the top with diverse and sometimes contradictory interests, with Putin presumably arbitrating between them. In practice, however, this pyramidal model only applies to strategic sectors such as the military or energy, large companies that are deemed vital to the national economy, and foreign policy areas that directly impact state sovereignty and the country’s international image. The remaining sectors of Russian power are largely decentralized, with nodes of power and authority at different steps of the ladder, contradictory interests, limited coordination, and a cacophony of diverging voices.

Similarly, foreign observers tend to see Russian networks of influence abroad as pyramidal, even though they are better represented as concentric circles of actors with different levels of access to the Russian authorities. Indeed, the Russian state leaves ample room for different categories of entrepreneurs who act in their own name and have their own business schemes. We have therefore opted to describe them using the term entrepreneurs of influence. Like all entrepreneurs, these individuals take on the risks and perils of their actions; they often use their own financial and social capital to invest in a sector, hoping that the Kremlin will provide a return on investment – whether financial and/or political – but knowing that they may fail and be disavowed by the Russian authorities or become a casualty of their competitors’ settling of scores.

A notable feature of the activities of these entrepreneurs of influence in recent years is that they have been conducted largely online. Entrepreneurs of influence create websites, organize influence campaigns on social networks, etc., to leverage their economic or political capital vis-à-vis the authorities. These activities leave behind digital traces called metadata that are freely accessible and can be used to document some of their tactics in detail. The techniques used to harvest, infer, and analyze such data are known as Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT).

An analysis of the technical data documenting the online activities of influence entrepreneurs allows us to debunk several widespread claims, such as the existence of centralized, detailed, and well-oiled strategies of influence abroad. On the contrary, it shows that most of these initiatives follow the specific agendas of their promoters and coordinate with official state institutions to varying degrees. The article presents granular insights into the global networks of influence that Russia has developed in recent years and outlines the inherent limits of Moscow’s endeavors.

To explore our interpretative grid, we look at the roles played by several entrepreneurs of influence and their digital traces. We divide these entrepreneurs into three broad categories based on their degree of proximity to the authorities: the tycoons (looking at the case studies of Yevgeny Prigozhin and Konstantin Malofeev), the timeservers (looking at Alexander Yonov and Alexander Malkevich), and the frontline pioneers (looking at the Belgian Luc Michel). We conclude by explaining that as a “poor great power,”Footnote1 “gray diplomacy” launched by private entrepreneurs seems to be the most cost-effective way for the Russian regime to try to regain a say in some sectors of international affairs.

Entrepreneurs of influence and their digital traces: a conceptual and methodological approach

The incredible diversity of actors who participate in Russia’s actions abroad is regularly highlighted. A European report on Russian disinformation, for instance, mentions the notion of “polarization entrepreneurs” – although without expanding on this (Bentzen Citation2018). Several journalists have observed the role of “freelancers” in Russia’s so-called hybrid warfare (Stelzenmüller Citation2017). Mark Galeotti has coined the term “adhocrats” to describe the actors of the largely de-institutionalized Putin regime, which uses a complex chain of command to create plausible deniability (see Kim Citation2017). However, there has not yet been robust scholarly analysis of the phenomenon. This article hopes to begin to fill that gap by introducing the concept of entrepreneurs of influence.

The notion of an entrepreneur of influence, as elaborated in this article, is grounded in a large body of literature that has documented the inner machinery and logics of Russian power over the past three decades. During the turbulent 1990s, “violent entrepreneurship” dominated the shift toward a market economy, epitomized by the famous “thieves in law” (vory v zakone, big mafia bosses with patrons inside the political system and the law-enforcement agencies) (Volkov Citation2002; Galeotti Citation2018). This culture of violent entrepreneurship seems to have been exported abroad and is now developing at a transnational level.

Researchers have highlighted the client and allegiance relationships that have cemented the Putin system of power. In this context, intra-elite relationships answer to logics of capitalization of the administrative resource (Kryshtanovskaya Citation2005; Ledeneva Citation2013; Raviot Citation2018), which has been notably ferocious in sectors deemed strategic and symbolic for the renewal of Russian power. One of the most strategic sectors for speculation is the development of networks of influence abroad that extract profits from the economic, political, and symbolic resources that the state agrees to invest there. The entrepreneurs in this sector are often not located at the summit of the pyramid; grassroots militia groups are for instance also used to perform some hybrid actions at home and abroad (Galeotti Citation2019).

To capture how these networks of influence work, it is necessary to distinguish between several categories of entrepreneurs of influence. Some are an integral part of Russia’s public diplomacy, with recognized institutional status in the organigram of the Russian state. These include(d) Natalya Narochnitskaya, who led the Institute for Democracy and Cooperation in Paris until it was closed in 2018, and Vladimir Yakunin, who launched the Dialogue of Civilizations’ annual meetings in Rhodes and then the Dialogue of Civilizations in Berlin (Barbashin and Graef Citation2019). To this category can be added the main oligarchs who coordinate closely with the Kremlin to fund the promotion of Russia abroad, including the billionaire president of Renova Group, Viktor Vekselberg, who bought Fabergé eggs and other Russian cultural objects to send them back to Russia. These individuals typically do not invest heavily in the digital sphere: their institutional status is secure enough for them to engage in more classical cultural diplomacy.

A second category that interests us here includes individuals who work outside the sphere of official public diplomacy and lack clear institutional recognition by the Russian state. In their eyes, the digital sphere is a key space for developing influence because it is seen as an open realm amenable to bottom-up individual initiatives, it is possible to fail and start over, and large investments of financial and social start-up capital are not necessarily required. The farther the concentric circles are from political power, the more the figures located within them need to rely on distant relationships with better-positioned individuals who can shore up their support from the central authorities.

In the third category, we find foreign personalities who negotiate the use of their services in their home country or in a third country but lack direct access to official Russian structures. These foreign personalities are left to speculate about their actual position in Moscow’s organigram of influence, and they act as “free electrons” at their own financial and legal peril.

The degree of autonomy left to individual entrepreneurs of influence remains difficult to grasp: are campaigns carefully staged or exercises in improvisation? Whereas some figures (such as Prigozhin) appear to coordinate closely with their patrons, it is less clear that others (such as Malofeev) do so. Many of these individual initiatives seem unconnected; they often appear opportunistic; they sometimes find themselves in competition with one another; and their moves seem to be shaped by local conditions, concerns, and considerations – yet they all position themselves under a shared strategic frame. The Kremlin has laid out a broad array of great power aspirations and then allowed myriad grassroots actors to interpret these aspirations in their own way and develop their own tactics for achieving them. If an initiative launched by an entrepreneur of influence fails, the Russian state structure therefore enjoys its famous plausible deniability and can refuse to take responsibility for it; if, however, the initiative succeeds, an entrepreneur of influence may be rewarded with official endorsement of his/her initiative.

Entrepreneurial behavior is determined by the political and economic forces that shape the Russian power system, especially personal loyalty to the President, as well as by the digital space, which represents one of entrepreneurs’ main spheres of action. Their operations, conducted in parallel to the return of Russia to any given region of the world, mostly take place in what Douzet and Grumbach have called the datasphere, i.e., the space “made of the totality of the digital data and technologies subtending it” (Douzet Citation2020, 6). Similarly to other spaces where a social environment can emerge, the datasphere – of which cyberspace is a component – answers to its own logics, and the actors who invest it seek to make these logics their own.

Any form of digital activity leaves behind metadata. Metadata document all our activities in the datasphere; the nature of an action and the context in which it was done are recorded in multiple forms in servers, where they can be accessed to various degrees. This data produced by the tools we use daily (social networks, browsers, routers, etc.) is extremely important not only to administrators and advertisers, but also to any actor that wishes to take advantage of this mass of information for the purposes of analysis, forecasting, or the exertion of diverse forms of control.

Like any actor with a digital presence, entrepreneurs of influence leave a multitude of traces behind them, most of which are never publicly disclosed due to data protection rules. This is true, for instance, of metadata produced by intermediation platforms such as Facebook and Instagram: as there are strong limitations on the ability to download metadata from social networks, we have de facto excluded them from the scope of our study. A tiny proportion of these traces, however, are open-source and freely available, namely data from the WHOIS register or Domain Name System (DNS) routing tables that indicate to which IP address a web address belongs. It is possible to use this accessible metadata to better understand certain networks of actors and put together a more detailed chronology or cartography. In other words, inferring information from technical data or metadata brings new elements to research, or at the very least allows researchers to confirm or dismiss certain hypotheses. For example, it is possible to determine that a cluster of websites is managed by a centralized entity even though nothing about their appearance or content would suggest that they were related. To make such a determination, we must figure out whether these websites share one or more similar Internet Protocol (IP) addresses – although this method has become less effective over timeFootnote2 – or identical advertising identifications (IDs).

Additionally, we can compare past and present declarative data extracted from WHOIS to identify similarities in postal addresses, names, and so on. Finally, a substantial part of such investigations could be described as a kind of “digital archeology,” as digital traces do not disappear when a website ceases to exist. Indeed, digital vestiges of forgotten information operations that happened 10 years ago are still available, even if all the contents have disappeared from the Internet. This makes it possible to establish detailed chronologies and trace the biographies of some entrepreneurs of influence. Tools such as the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine (https://archive.org/web/) are important for such investigations, as they store snapshots of websites and pages that went offline a long time ago.

Known as OSINT (Open-Source Intelligence), these techniques and their results have been popularized by the work of investigative teams such as Bellingcat or EU Disinfo Lab (EUDisinfoLab Citation2020) on various sensitive topics. In the case of Russia, the identification of the agents behind Navalny’s poisoning attempt through the digital traces they left behind illustrates that even intelligence agencies can be compromised by such methods. In broader perspective, the rise of OSINT reveals how digital traces, which were once considered as technical metadata with no political significance or utility, are now central to understanding power structures in the digital era.

If such investigations are common in some technical and journalistic communities,Footnote3 or to literature on so-called active measures (Shultz Citation1984; Rid Citation2020), they have been underused by social scientists interested in power relationships. Of course, a growing number of OSINT investigations are being released to help social scientists document phenomena such as Russian influence. In most cases, however, investigations are mobilized as external sources and not as a part of the demonstration per se. This epistemological limitation tends to relegate OSINT to the status of a documentation technique. We, however, argue that it has a role to play in conceptual matters. In our case, analyzing and cross-analyzing metadata produced by the digital activities of actors of interest allows us to delineate the concept of an entrepreneur of influence and to dismiss a number of presupposed ideas about the organization of the Russian apparatus of influence. As such, this article is a demonstration not only of the concept, but also of the utility of such technical methods for area studies.

The tycoons: serving Russia’s interests abroad

In the first category of entrepreneurs of influence who navigate the world of “gray diplomacy,” we find those we call the tycoons: figures with a solid network of patrons who are already system “insiders” in many respects but do not have official, recognized, institutionalized status. They use their own financial capital to launch influence operations abroad, and then use these influence operations to build legitimacy at home. We focus on the cases of the infamous Yevgeny Prigozhin and Konstantin Malofeev, who have been competing to take control of the patriotic/nationalist Rodina party in advance of the September 2021 parliamentary elections (Shevchuk Citation2020). Both hope to have built enough support within the regime to be able to capitalize on their successes abroad and create a new political brand for themselves that would serve the ideological niche of nationalism to the “right” of the centrist United Russia party.

Yevgeny Prigozhin’s media empire and its unknown ramifications

Yevgeny Prigozhin (b. 1961) is a well-known figure within Russia’s influence apparatus. Among other things, he is one of the key figures of the famous Russian private military company (PMC) Wagner, which has mercenaries on the ground in countries including Libya, the Central African Republic, Mozambique, and Venezuela (Vasilyeva Citation2017; Marten Citation2019b, Citation2020; Rondeaux Citation2019; Bellingcat Citation2020; Weiss and Vaux Citation2020a). Prigozhin is well known among the general public in the West, having been named as the founder of the Internet Research Agency (IRA) in an FBI indictment of Russia’s meddling in the 2016 US presidential election (Linvill et al. Citation2019).

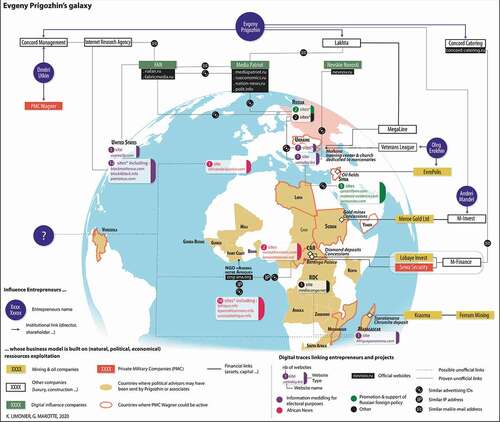

Dubbed “Putin’s chef” by the media because his business activities focused on catering, Prigozhin is at the center of a vast galaxy of interests that has been documented by several investigations. His companies and activities left many traces, which were followed by some Western and Russian journalists for years, constructing a very complex web of interests that we tried to summarize in the following map (see ).

This map is a geographical representation of Prigozhin’s interests around the world, with an emphasis on his digital activities. It shows information coming from many sources, correlated with digital traces and metadata that were retrieved by the authors of this paper. In other words, this map makes it possible to visualize the “digital archeology” we conducted to illuminate how Prigozhin’s digital influence network developed and became a core element of his “empire.”

This cartography is not intended to represent the whole spectrum of Prigozhin’s activities. His military activities through PMC Wagner are only mentioned, while some initiatives that left almost no digital traces have been excluded, as with the Association for Free Research and International Cooperation (AFRIC), an entity used by Prigozhin and his associates to organize political meetings, provide consulting on political matters, and observe elections in Africa (Shekhovtsov Citation2020). We decided not to focus on such initiatives, as they have mostly taken place in the real world and have left no evidence of digital activity.

Interestingly, Prigozhin’s “digital empire” is divided into two parts: first, activities within Russia or in countries that are Russia’s top strategic priorities (Ukraine, Syria, and the United States); and second, activities in Africa (Bat Citation2020). In both of these groups, there are clear overlaps between business interests and digital influence operations, making it possible to draw a kind of evolving business model for Prigozhin’s activities.

Digital traces linked to influence operations are more visible in the first set of countries than they are in Africa, mainly due to the period when such actions took place: Ukraine, Syria, and the US were targeted in 2014–2016, when manipulation techniques were less sophisticated and less observed by journalists and researchers. By contrast, many digital influence operations taking place in Africa are probably still active, but the tracks of these activities are being covered more carefully. In other words, there is a difference between Prigozhin’s “first digital influence empire,” which flourished until the 2016 US presidential election and was characterized by impunity, and his “second empire,” which is much more difficult to track via OSINT alone.

The first signs of Prigozhin’s digital involvement date back to 2011–2012, when tens of thousands of Russian citizens demonstrated against Vladimir Putin’s intent to run for a third presidential term (Greene Citation2014). To undermine the credibility of the demonstrators and their leaders, trolls and bots appeared en masse on the Russian Internet for the first time. At the time, there was no clear evidence that these trolls and bots had ties to Prigozhin. A year later, however, a Novaya Gazeta investigation revealed the existence of a well-organized troll farm in Olgino, near St. Petersburg (Gerard Citation2019), that was owned by Prigozhin and employed nearly 400 people (Garmazhapova Citation2013). It soon launched operations to influence Ukraine after Maidan and the United States during the 2016 presidential election. The Internet Research Agency, as it would come to be known, became famous for its alleged role in Donald Trump’s victory. Digital traces of some websites founded by the IRA during this operation can still be found, while Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s (Citation2019) report adds some interesting details.

But the IRA was only a small part of Prigozhin’s first digital influence empire. Other official structures soon appeared, including Nevskie Novosti, the Federal News Agency (FAN), and the Media Patriot group (the latter two located at the same address where the IRA was once housed) as well as other companies owned by Prigozhin.Footnote4 In the Prigozhin nexus, Media Patriot and FAN are dedicated to internal Russian public opinion and to the Russian-speaking communities living in the “Near Abroad” – with the exception of the website USAreally.com, which is still active in addressing an American audience (Peniguet Citation2018). Even if they are at the forefront of – and the showcase for – Prigozhin’s digital influence empire, FAN and Media Patriot share similar advertising IDs or IP addresses with a nexus of Ukrainian websites that were active at the time of the 2014 Maidan revolution (see Emaidan Citationn.d.). Some might have been fake websites trying to pass as anti-Russian platforms; they confirm Prigozhin’s engagement in the Ukrainian conflict.

Less known is the case of Nevskie Novosti, whose ties to Prigozhin were revealed by the Mueller report (Mueller Citation2019). A St. Petersburg-based media company, it officially manages the local news website nevnov.ru (Fontanka.ru Citation2019). We discovered that nevnov.ru shares a technical signature (a Google Analytics ID) with the Ukrainian website uatoday.biz (active in 2015–2016), which in turn has identical signatures to a series of websites related to the Syrian civil war, such as syriainform.com, material-evidence.com, and syriaunion.com (UA Today Citationn.d.). Some of these websites deserve a more thorough investigation, as they represent a facet of the Prigozhin nexus that has not been explored by scholars so far.

Websites and entities linked to FAN, Media Patriot, and Nevskie Novosti thus form the core of this “first digital influence empire,” which today coexists with another vast group of initiatives targeting Africa. This “African empire” seems to have been developing since at least 2017, probably in an attempt at diversification. Indeed, if digital influence represents a significant part of Prigozhin’s activity, it is far from his only sphere: the companies tied to this tycoon have profiles as diverse as catering and construction – and equally varied objectives. In many cases, there are correlations between activities such as mining or security/PMC and digital traces linked to information operations.

This is especially true in Africa, where the exploitation of natural resources seems to be intimately connected to digital influence. In the Central African Republic, for example, Russian presence has been epitomized in the activities of two companies specializing in security and diamond mining, respectively: Sewa Security and Lobaye Invest (Olivier Citation2019). These two companies, registered in Bangui, are linked to an entity known as M-Finance (Marten Citation2019a) that has demonstrable links to Prigozhin. Indeed, the email address available on Russian registers for M-Finance refers back to the historical server of Prigozhin’s luxury catering company, concord-catering.ru (Davlyatchin Citation2019). Nowadays, Sewa Security is responsible for President Touadéra’s security; its employees are presumably housed in the former Bokassa palace located in Berengo. Lobaye, for its part, has obtained several mining concessions in the center of the country – an area of heightened tensions that is controlled by the Seleka (Centrafrique le défi Citation2018).

These activities in the fields of security and mining are correlated with digital initiatives of unclear origin, as several websites openly supporting Russian presence in the country have been detected for years. These include the website lemondeenvrai.net, which has an IP and analytics ID similar to tens of other platforms linked to an Ivory Coast–based NGO called Aimons Notre Afrique (ANA). ANA, which openly presents itself as a “coalition of media” working to prevent “Africa’s destabilization” by Western actors (Aimons Notre Afrique Citationn.d.), administers at least 18 news websites that often present Russia in a very positive way. If the link between ANA and Russian interests remains unknown, the pattern of a digital initiative comprised of tens of websites created and administered by a central entity and addressing topics close to Russia’s interests in the region is reminiscent of the strategies of Prigozhin’s “first digital empire.”

Moreover, it is similar to what has been seen in other African countries, such as Madagascar. Investigations have confirmed the presence of Russian political advisors in Madagascar to help several candidates in the 2018 presidential elections, but none won more than a small percentage of the vote (Rozhdestvensky and Badanin Citation2019). These activities were accompanied by an attempt to use the St. Petersburg-based Ferrum Mining, which is probably linked to Prigozhin’s interests (Rozhdestvensky and Badanin Citation2019), to take over a chromite mine belonging to a local firm (Ihariliva Citation2019). In the field of digital influence, the London-based Center Dossier – an NGO funded by former oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky – revealed that Madagascar was targeted by a campaign conducted through a website called afriquepanorama. This website was funded by Prigozhin’s collaborators and is now offline (Harding and Burke Citation2019). Afriquepanorama had a lot of content in common with the Congo-based website mediacongo.net, whereas the Center Dossier mentions another platform that could have been supported by Prigozhin. Called African Daily Voice, the news agency was once owned by an advisor of former Ivory Coast president Laurent Gbagbo, who has been prosecuted by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity (Kobia Citation2019).

Konstantin Malofeev: building a monarchist cluster in Russia and Abroad

Konstantin Malofeev (b. 1974) embodies another type of tycoon, one less well versed in military adventures than Prigozhin, but with a more developed ideological agenda.

A lawyer by training, in 2005 Malofeev founded Marshall Capital Partners, an investment fund specializing in telecommunications.Footnote5 He was also elected to the Board of Directors of Svyazinvest, Russia’s largest state-controlled telecommunications company, prior to its merger with Rostelecom (Sal’manov Citation2012; Shleinov Citation2013). Malofeev has benefited from close political and personal connections to Igor Shchegolev (b. 1965), who was minister of telecommunications and mass communications when Malofeev served on the board of Svyazinvest. Malofeev and Shchegolev launched the League for a Safe Internet, which hoped to help strengthen Russian legislation online, win market share in the communications sector, and promote the launch of conservative websites with a clear “traditional values” agenda (Russian Reader Citation2019).

Using funds raised by Marshall Capital, Malofeev founded the Philanthropic Fund of St. Basil the Great, which now boasts some 30 programs advocating a broad range of family values (anti-abortion groups, assistance to former convicts and single mothers, etc.), providing Orthodox religious education, and offering assistance to churches and monasteries.Footnote6 Malofeev has also been funding the Donbas insurgency – even if, officially, he is simply providing humanitarian assistance per an agreement between his Fund and the Donetsk Republic (Ser’gina and Kozlov Citation2014) – but was marginalized on the Donbas scene once Vladislav Surkov, then Assistant to President Putin, took over control of the insurgents (Hosaka Citation2019). Proud of his monarchist convictions (Malofeev Citation2014), Malofeev has funded several meetings at which the European and Russian far rights have become acquainted with one another and with monarchist circles (Shekhovtsov Citation2017).

Malofeev is active not only in Europe, but also at home. In 2006, he opened the St. Vasily the Great Gymnasium, a private boarding institution in the Moscow suburbs that can accommodate up to 400 pupils. The gymnasium, which claims that it is forming a new Russian elite and instilling monarchist values in students, fosters a tsarist atmosphere by holding traditional balls and hanging portraits of the imperial and major aristocratic families on the walls. It reproduces the tsarist education program, with daily prayers in Slavonic and classes on Orthodoxy, Latin, calligraphy, and traditional etiquette (Mandraud Citation2017). In 2015, Malofeev launched the first monarchist television channel, Tsargrad – after the old Russian name for Constantinople. Tsargrad was able to secure about 13 million regular viewers as a cable channel on the NTV network, but was demoted from cable to the Internet two years later (Dziadul Citation2017).

In 2016, Malofeev inaugurated the Two-Headed Eagle, ostensibly an association for historical enlightenment but that seems to act as a political party with a clear objective: “the transformation of Russia into a full monarchy … by constitutional means” (Dvuglavnii orel Citation2017). The Association has been able to secure some support among the establishment: it counts several MPs and high-level officials among its members – including former governor of Belgorod Yevgeny Savchenko and Lieutenant General Leonid Reshetnikov, the former director of the Russian Institute for Strategic Studies (RISI), the think tank of the Foreign Service Intelligence (SVR) (Chapnin Citation2017) – and can rely on the backing of part of the Moscow Patriarchate.

While continuing to instrumentalize his connections with the European far right and aristocratic circles, Malofeev began looking for new theaters of action and decided to test himself on the African scene by becoming president of the International Agency for Sovereign Development (IASD, or the Agency). Launched during the Russia–Africa Summit of November 2019, the Agency aims to “assist governments of developing countries, especially the countries of the African continent, in carrying out economic reforms, raising funds on international capital markets and unlocking potential of increasing shareholder value of the largest corporations in the region.”Footnote7 The IASD published a report entitled Conspiracy Against Africa: Breaking the Shackles of Colonialism (Zagovor protiv Afriki: razbivaya okovy kolonializma), which employed all the usual clichés about the persistence of European colonialism in Africa and the dictates of the Washington Consensus institutions that purportedly entrench the dependency and exploitation of Africa (Pudovkin Citation2019). The Agency says it is helping to raise funds and attract investors to bond offerings outside European markets to contribute to Africa’s economic decolonization. So far, it has been hired as a consultant by three African governments and has apparently raised US$2.5 billion for the construction of a pipeline in Niger and the development of transportation infrastructure in Guinea and the Democratic Republic of Congo (Malofeev Citation2019).

The Agency is a perfect example of the mechanisms of Russian para-diplomacy: it is a private institution that benefits from official endorsements. It was launched during the Russia–Africa Summit and was an official partner of the summit along with the state atomic corporation Rosatom, a fact that highlights its ambiguous status. It has publicly received help from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs to establish contacts with potential African partners (Zibrova Citation2019). The report Conspiracy Against Africa was also unveiled in the presence of Sergey Glazyev, the presidential advisor for regional integration and one of the brains behind the Eurasian Economic Union, which advocates for a directed economy modeled on the Soviet Union,Footnote8 and is a member of the ultra-conservative Izborsky Club (Laruelle Citation2016). Glazyev is now listed among the consultants of the Agency and has echoed the anti-colonial and anti-Western message of the report, providing the narrative with a form of official endorsement by the Russian state (Parfent’eva and Kozlov Citation2019).

The Agency can also rely on some influential powerbrokers. It is, for instance, associated with Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, the eccentric former President of the Kalmyk Republic, who is currently under US sanctions for aiding and abetting Russia’s allies in Syria (US Department of the Treasury Citation2015). Ilyumzhinov traveled to Sierra Leone, Kenya, Togo, and Burkina Faso in 2019 to help set up investment meetings with Russian firms (Maldonaldo Citation2020). The current director of the Agency is Mikhail Leshchenko, who made his career in communications, was once vice-president of Svyavinvest, and was also an adviser to Minister of Communications Igor Shchegolev. Malofeev’s sudden reorientation toward the development of Africa is pure opportunism, but it confirms the ability of entrepreneurs of influence to secure enough high-level support to create such an institution from scratch and acquire official recognition for it.

Malofeev’s digital traces reflect his strategy of building a patronage network to secure his status. Registered in late 2014, the domain name tsargard.tv has since been linked to 3 IP addresses (Tsargrad Citationn.d.). Each of these addresses is linked to other websites that address themes and issues close to Malofeev’s values. This general architecture, where many websites share a similar IP address (and sometimes a similar Analytics ID) and focus on related topics, strongly suggests a single administrator. Between 2015 and 2016, Tsargrad.tv shared the same IP address as websites (often inactive as of 2021) promoting Christian fundamentalism and the defense of childhood.Footnote9 Among them was the personal website (now offline) of Elena Mizulina (Wayback Machine Citation2020), the current Chairman of the Duma Committee on Family, Women and Children Affairs, who is well known for her role in passing several controversial laws regarding the LGBT+ community and the adoption of Russian orphans by foreigners. The IP address also links to the still-active personal page of the infamous geopolitician Alexander Dugin (dugin.ru), as well as the official website of the National Center for Assistance to Missing Children (findchild.ru).

In the same IP cluster, one can find an inactive page for the Russian section of the World Congress of Family, a reactionary organization that defends the so-called traditional family (Stoeckl Citation2020); the integrist journal Views&Values Christian Global Post, which was active only for a few months in 2014–2015; and the multilingual Christian fundamentalist website ihsv.info (now offline), the name of which, IHSV, is a reference to Emperor Constantine’s In hoc signo vinces (“In this sign you will conquer”). Interestingly, this IP cluster was also linked to the domain lbihost.ru, active in 2016, which was an attempt by the League for a Safe Internet to create its own hosting service (Wayback Machine Citation2019); this might explain this concentration of websites on similar IPs and servers.

During less than a month in 2015, tsargrad.tv changed its IP address and revealed another cluster of coherent websites, including an inactive blog by Dugin; a very professional and well-funded website promoting the Shmidov family, 35 children and orphans being raised by an Orthodox priest (shmidovy.ru); and the website of the youth wing of the League for a Safe Internet (kiberdruzhina.ru), a cyber-militia that claims to fight against content that “threatens the physical and moral health of children” (Safe Internet League Citationn.d.). Since 2015, tsargrad.tv has been linked to another IP address revealing a cluster of a variety of websites, these ones more professional. They include novorosinform.org, a website that provides information on Donbas secessionism under the Novorossiya label and once shared an IP address with pro-Donbas websites such as novorossia.su (linked to Yonov’s Antiglobalist Movement – see below). A digital archeology of Malofeev’s actions thus confirms his consistent ideological engagement with ultra-conservative values, as well as revealing his connections within the political establishment (including with Mirzulina) and his patron-like role in relation to public intellectuals like Dugin.

The timeservers: merchandizing influence

In a second concentric circle are located merchants of influence who build a career for themselves by trying to sometimes precede, sometimes follow what they interpret as the Kremlin’s objectives. In contrast to the tycoons, they are not already well-established insiders and do not display a specific ideological or pragmatic agenda; instead they have to fight to secure their status inside the “system” and are available to provide almost any services. We call this group the timeservers, highlighting two case studies: Alexander Yonov and Alexander Malkevich.

Alexander V. Yonov, an economist by training, was formerly president of the Russia Committee for Solidarity with the Peoples of Syria and Libya. He currently serves as a member of the Paris-based International Committee for the Protection of Human Rights (CIPDH), which presents itself as an organization of lawyers who defend human rights pro bono (CIPDH Citation2021). He is also editor-in-chief of Sodruzhestvo narodov (Community of Peoples) and hosts the radio show “We Don’t Forget Our Own,” dedicated to Russian compatriots. Finally, he is a member of the presidium of the organization Officers of Russia, an organization close to Dmitry Rogozin’s Rodina Party (IONOV Transcontinental Citation2000b). Yonov has his own company, Yonov Transcontinental, which specializes in industrial agriculture, energy, and communications security, and which also appears to work in the private security sector (IONOV Transcontinental Citation2000a). This track record – accumulating administrative status inspired by the Soviet legacy of the friendship of peoples and internationalism, as well as membership in the various military-patriotic associations in vogue today – is typical for an entrepreneur of influence little known to the Russian public, and even less to foreign observers.

In 2011, Yonov launched the initiative that has been most successful at attracting the interest of state structures: the Anti-Globalization Movement of Russia (AntiglobalistSkoe dvizhenie Rossii, AGD). The AGD aimed to “[help] countries and individuals in their opposition to the dictate of the unilateral world and in their quest for an alternative agenda” (see Antiglobalization Movement of Russia Citationn.d.). The Movement listed 32 foreign partner organizations in Syria, Libya, Palestine, Iraq, Lebanon, Egypt, Sudan, Tunisia, Iran, Venezuela, Bolivia, Argentina, El Salvador, and North Korea, as well as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) from the US, the United Kingdom, Germany, Poland, Italy, and France. The fact that Bashar Al-Assad, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and the late Hugo Chavez were among its honorary members demonstrates that the movement’s organizers could reach high in the pyramid of power.

The main objective of the movement was to convene two important conferences in 2015 and 2016 on “Dialogue of Nations: The Right of Peoples to Self-Determination and the Construction of a Multipolar World” (Meduza Citation2015). Thanks to funding from the National Charity Fund (Natsional’nyi blagotvoritel’nyi fond), these conferences were held in one of Moscow’s most famous hotels. The Fund, created in 1999 by Vladimir Putin to provide public funds for patriotic activities, contributed 2 and 3.5 million rubles, respectively, to these conferences (Makarenko Citation2015, Citation2016). During these two conferences, the Dialogue of Nations brought together numerous secessionist associations with an anti-American or anti-colonial agenda: the secessionist movements of Texas, California, Puerto Rico, and Hawaii; the Uhuru movement for the defense of African-Americans (a former fellow traveler of the Soviet Union that called for a Black internationalist socialism); autonomist movements from Catalonia and Sicily, the Republican Sinn Féin in Ireland, and the Polisario Front that advocates for the independence of Western Sahara; and several European far-right parties, such as the Italian Northern League and one of its partners, the pro-Russian groupuscule Millennium. Since 2016, the organization has apparently reduced its activities – its Facebook page is now inactive – even though annual seminars are still organized in its name.

Yonov probably met Alexander Malkevich during the campaign for the liberation of Maria Butina, a Russian citizen who was detained by the FBI and convicted by a US court of being an unregistered Russian agent. Malkevich, who made a career for himself at various Russian regional TV channels, has found himself in the public eye on two recent occasions. First, in 2018, he was editor-in-chief of the website USAreally when it was blocked by US authorities, with the result that Malkevich himself was added to the list of persons prohibited from entering the United States (US Department of Treasury Citation2018). Then, in 2019, two of his employees, who had presented themselves as “sociologists,” were detained in Libya and accused of supporting Muammar Gaddafi’s son, Saif al-Islam al-Gaddafi, who is wanted by the International Court of Justice for crimes against humanity (MacKinnon Citation2019).

Like Yonov, Alexander Malkevich has accumulated a variety of roles. He is a member of the Civic Chamber, which is probably his most official duty, and sits on several Duma commissions on information security. He also founded the Foundation for the Protection of National Values (Fond zashchity natsional’nykh tsennostei), which, according to its website, “works to protect the national interests of the Russian Federation, preserve traditional culture, study international experience, protect freedom of speech and media representatives around the world, and cooperate with international organizations” (Foundation for National Values Protection 2020). The Foundation has seemingly since integrated into the Prigozhin empire: the two purported sociologists arrested in Libya were apparently mercenaries affiliated with the Wagner Group.

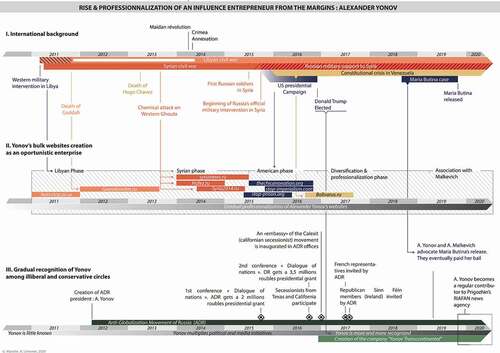

Using a similar methodology to the one we used to understand how Prigozhin’s and Malofeev’s digital galaxies are structured, we tried to retrieve digital traces left by Yonov online. By checking URLs that were once linked to the IP address of the Anti-Globalization Movement website (Antiglobal Citationn.d.), we found approximately 20 entities (now offline) that focused on topics of political significance. We argue that these websites were probably created by Alexander Yonov (who is listed on some websites as “founder” – see Syria2014 Citation2014, 2014) or in close coordination with him, as they share the same IP address, have clear political coherence, and follow an interesting chronological pattern (see ).

Yonov launched his first activist websites in 2011–2013. One of these early sites (Greenkomitet.ru Citation2012) supported the Libyan Jamahiriya and the Gaddafi regime, while another (Natostop.pl.ua Citation2011) denounced Western military intervention and “NATO imperialism” more generally. The centrality of the Libyan crisis to the early stages of the politicization of an entrepreneur like Yonov is not anodyne; in Russia, Western intervention in Libya was perceived as yet another manifestation of American and European imperialism (Bijan Citation2019). In other words, it sowed the seeds for the Russian apparatus of informational influence that was to emerge later, especially during the Syrian civil war. Later, Yonov came to focus on the Syrian crisis, likely launching three websites – hafez.ru, Syrianews.ru, and Syria2014.ru – defending Bashar Al-Assad.

In 2015–2016, two more domain names were purchased at Yonov’s IP address: stop-prison.org, registered in Yonov’s name (WHOXY Alexander Citationn.d.), and thechicanonation.org. Both websites potentially targeted a US audience around the 2016 presidential elections. There are no traces of the content of either site. That being said, the first, stop-prison.org, appears on a Facebook page called “Dallas Committee to Stop FBI Repression” (2015), which focuses on the repression of minorities in Texas. For its part, the second, thechicanonation.org, the name of which might refer to Mexican Americans or to the Chicano movement (a civil rights movement inspired by the Black Power Movement), has been flagged as a malicious domain that has been observed spamming. This allows us to hypothesize, even in the absence of clear digital traces, that they might be the remains of an operation that targeted minorities in the US in the context of the 2016 elections.

The scandal created around Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential elections seems to have sapped Yonov’s passion for creating websites – or maintaining existing ones. No new domain has been linked to his usual server; the website of the Anti-Globalization Movement of Russia has gone silent. With the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) taking a close interest in the actors behind informational interference, creating websites no longer seems to be an easy way to exert influence.

Aside from a few meetings with Irish and French activists, Yonov’s political activities seem to have been frozen – but it is likely that his influence endeavors have in fact entered a new dimension. His name is now regularly mentioned in the newspapers of the Media Patriot group and he gives interviews to larger Russian newspapers, such as Moskovskii komsomolets. He has also become a consultant for the International Agency for Sovereign Development (Kislyakov Citation2020). Most importantly, Yonov and Malkevich were tasked with raising funds to bail out Maria Butina and organizing her extradition to Russia (Izvestiya Citation2019; Michel Citation2019). Because the Butina issue was highly sensitive, their international visibility confirms that they have both been able to secure recognition within the structures of Russia’s “gray diplomacy.”

The local pioneers: opening new front lines

In a third concentric circle are local actors who join Russia’s actions abroad out of ideological conviction and/or due to materialistic, opportunistic motives. These local actors have their own agendas to pursue in terms of securing their own networks and legitimacy, and interact in a more distant way with Russian institutions or representatives. We take the Belgian Luc Michel as our case study of these “local pioneers.”

Michel has been involved in the nationalist-revolutionary sphere since his late teens, inspired by Jean-François Thiriart (1922–1992), the ideologist of a pan-European fascist third wave who promoted the idea of a “Euro-Soviet Empire from Vladivostok to Dublin” (Thiriart Citation1984). In 2006, the French newspaper Libération painted Michel as “paranoid” and a “megalomaniac” (Albertini and Benetti Citation2016).

Michel founded the small Communitarian National-European Party, envisioning it as a pan-European movement that would, by uniting far right and far left, liberate Europe from “Yankee colonialism” (Nation-Europe Citation2005). Seeing Russia as the main opponent of US imperialism, he had built contacts with Russian far-right ideologists such as Alexander Dugin by the early 1990s, but he also defended other “resistance” figures such as Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi.

In the mid-2000s, Michel succeeded in institutionalizing his status through the Commonwealth of Independent States–Election Monitoring Organization (CIS-EMO), an organization that has been a pioneer in monitoring controversial elections in the post-Soviet space. He then established his own electoral monitoring organization, the Eurasian Observatory for Democracy and Elections (EODE), which has validated the secessionist elections and referendums organized in Transnistria, Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, Crimea, Donbas, etc., and has offices in Moscow, Paris, Brussels, Sochi, and Chișinău.Footnote10

Michel subsequently turned his interest to Africa, becoming the figurehead of the TV channel Afrique Media (afriquemedia.tv). Based in Cameroon, where its domain name was registered in 2011, the channel brands itself the “pan-African CNN” and is followed by nearly 260,000 people on Facebook. Once headed by the activist Kemi Séba, Afrique Media has produced vast amounts of content condemning “foreign influences” portrayed as eager to “destroy Africa.” Overall, the editorial line of the outlet can be described as verging on conspiracy theory with a patina of radical pan-Africanism that blames Westerners – especially the French – for every problem facing the African continent.

Michel seems to have endorsed Afrique Media as early as 2014. That year, he announced on his blog that Russia had “saved Afrique Media from the rascalism of Canal+” (Michel Citation2014)Footnote11 in a business quarrel over the attribution of satellite frequency bands. Without going into any detail about this so-called rescue mission or his role therein, Michel congratulated himself on having apparently, “with help from the Russians,” prevented the cessation of the channel’s broadcasts on a frequency owned by Canal+.Footnote12 Since then, Michel has continuously offered support to this pan-African media outlet. In 2016–2017, he held a fundraising call to finance the construction of new offices for the channel, a move he repeated in 2019 to finance the opening of an Afrique Media office in Brussels (Leetchi Citationn.d.). In addition to his financial support, Michel often appears on the channel, where he presents himself as a geopolitician and Africa specialist. In April 2019, he met with the First Lady of Chad in Ndjamena, introducing himself as Afrique Media’s main TV anchor (Alwihda Info Citation2019).

Afrique Media is not the only platform linked to Michel. The Belgian adventurer also runs a large network of websites directed toward African audiences. He manages the website La voix de la Libye (The Voice of Libya) as well as several online TV channels in Chad, Cameroon, and Benin. Most of these websites are registered in the name of Fabrice Béaur, a fellow Belgian citizen who is also a member of the Communitarian National-European Party (WHOXY Fabrice Citationn.d.). Béaur, a political activist who has written for Sputnik News and the Iranian outlet PressTV, seems to have provided technical support to Michel by creating and organizing his network of websites (WHOXY Fabrice Citationn.d.).

Michel is typical of the early entrepreneurs of influence: he has invested resources – time, money, and networks – in promoting Russia’s vision of the African continent on different platforms. It is very unlikely that Michel acted at the request of Moscow, even if he and Prigozhin may be connected through AFRIC (Weiss and Vaux Citation2020b). Yet he and Afrique Media are de facto echo chambers for Russian narratives, as such narratives are aligned with their own political agendas. This type of pioneering entrepreneur therefore sees Russia as a resource that can be deployed to bring his own projects to fruition.

Conclusion

Western experts often present Russia’s so-called hybrid warfare as a black box closed to external observers. While it is difficult to capture personal interactions and informal endorsements, a more granular approach to the actors of Russia’s parallel diplomacy through techniques of digital investigation offers important insights into the structure of the Russian political system. It is far more plural, decentralized, and chaotic than outside observers tend to see it as being.

This plurality and decentralization may have emerged by default, but the Kremlin now purposefully uses it. As a poor great power, Russia has to promote private initiatives that support its strategic interests and use entrepreneurs of influence to test the ground where official public diplomacy is weak or limited. If the test succeeds, then official structures can consolidate the established network. If the test fails, official institutions enjoy plausible deniability and can adapt their approaches and discourses in response to these failures.

The cases explored here are good examples of the nexus of entrepreneurs of influence that has evolved around the networks of Russian power. Some of these entrepreneurs – like Prigozhin and, to a lesser extent, Malofeev – have already found their way into the concentric circles of the regime; others, like Michel, remain on the margins. As for Yonov, his progressive transformation into a full-fledged entrepreneur of influence with a well-stocked address book – that is, a person capable of organizing transnational solidarity networks – took over a decade and was solidified by the creation of the International Agency for Sovereign Development.

Their experiences reflect the Russian strategy of using plausible deniability in games of foreign influence that are not part of the country’s recognized public diplomacy. They also point to the neo-liberal nature of Russia’s current ideological production: entrepreneurs of influence operate at their own risk, without a safety net, and must largely self-fund their activities. It is up to them to create a financially self-sufficient mechanism of influence. It is also important to note that the Kremlin uses different networks of influence in different regions of the world; those employed in Europe are far more traditional than those used in Africa. Because Russia made its return to the African continent long after France, China, and the United States, it finds itself playing marginal cards – either taking advantage of its Soviet past or leaving the door open to adventurers of all kinds.

Entrepreneurs of influence encapsulate the often-understudied neoliberal aspect of Russia’s return to the international scene. Activities that were once the exclusive province of state institutions have now been outsourced to private actors. Some imagination, a lot of opportunism, and financial or social start-up capital help these entrepreneurial figures to find a room of their own in the gray zones of Russia’s quest for great-power status.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. This paradox was already noticed in the early 1990s by Sokoloff (Citation1993). See also Hancock (Citation2007).

2. It is increasingly rare to find clusters through this method, since an IP address can now refer to hundreds of websites that are linked only by having the same host.

3. Thanks in particular to the work of the investigative media outlet Bellingcat.

5. The most complete biography of Malofeev (in Russian) is Komitet Narodnogo Kontrol’ya (2020). See also Latynina (Citation2012). In English, see Arkhipov, Meyer, and Reznik (Citation2014).

6. Originally named the Russian Society of Philanthropy in Defense of Motherhood and Childhood.

7. See the Agency’s website: https://iasd.ru.

8. For a neoliberal reading of Glazyev’s economic policies, see Åslund (Citation2013).

9. These websites included support.parentchannel.ru; shop.safeinternetforum.ru; parentchannel.ru; rusreview.com; whiteinternet.info; incident64.ru; and safeinternetforum.ru.

10. For a longer biography of Luc Michel, see Shekhovtsov (Citation2015).

11. The original blog post has been deleted, but a cache can still be found on the Voice of Libya website, one of the many administered by Luc Michel: https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:ym1K_Cg0YOYJ:https://lavoixdelalibye.com/2014/08/02/la-russie-sauve-afrique-media-de-la-voyoucratie-canal/+&cd=2&hl=fr&ct=clnk&gl=fr

12. See note 11.

References

- Aimons Notre Afrique. n.d. “Qui Sommes-Nous? [Who Are We?].” Accessed 12 March 2021. http://ong-ana.org/a-propos-d-ana/qui-sommes-nous/

- Albertini, D., and P. Benetti. 2016. “Burundi: Fachosphère D’influence [Burundi: Influence Fashosphere].” Libération, 1 August 2016. https://www.liberation.fr/planete/2016/08/01/burundi-fachosphere-d-influence_1469773

- Antiglobal. n.d. “ANTI-GLOBAL.RU.” Accessed 15 March 2021. https://builtwith.com/relationships/anti-global.ru

- Antiglobalization Movement of Russia. n.d. “Vstupai Ryady Antiglobalistov! [Join the Troops of Antiglobalists!].” Accessed 12 March 2021. http://anti-global.ru/?page_id=164

- Arkhipov, I., H. Meyer, and I. Reznik. 2014. “Putin’s ‘Soros’ Dreams of Empire as Allies Wage Ukraine Revolt.” Bloomberg, June 15. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-06-15/putin-s-soros-dreams-of-empire-as-allies-wage-ukraine-revolt

- Åslund, A. 2013. “Sergey Glazyev and the Revival of Soviet Economics.” Post-Soviet Affairs 29 (5): 375–386. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2013.809199.

- Barbashin, A., and A. Graef. 2019. “Thinking Foreign Policy in Russia: Think Tanks and Grand Narratives.” Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/thinking-foreign-policy-in-russia-think-tanks-and-grand-narratives/

- Bat, J.-P. 2020. “L’Afrique Centrale: Le Nouveau ‘Grand Jeu’ [Central Africa: The New Great Game].” Hérodote 2020/4 (179): 91–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.3917/her.179.0091.

- Bellingcat. 2020. “Putin Chef’s Kisses of Death: Russia’s Shadow Army’s State-Run Structure Exposed.” Bellingcat, August 14. https://www.bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2020/08/14/pmc-structure-exposed/

- Bentzen, N. 2018. “Foreign Influence Operations in the EU.” European Parliamentary Research Service, July. Accessed 12 March 2021. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/625123/EPRS_BRI(2018)625123_EN.pdf

- Bijan, A. 2019. “Importance of the Libyan Crisis for Russia after the Arab Spring.” Russian International Affairs Council, December 13. https://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/columns/african-policy/importance-of-the-libyan-crisis-for-russia-after-the-arab-spring/

- Centrafrique le défi. 2018. “Centrafrique: Lobaye Invest SARLU décroche un permis de recherche [CAR: Lobaye Invest SARLU Secures a Research Permit].” Centrafrique le défi, August 31. https://www.centrafriqueledefi.com/pages/economie-industrie/centrafrique.html

- Chapnin, S. 2017. “Tsarskie Ostanki: Obratnyi Otschet [Tsarist Remains: The Countdown].” Colta, July 18. https://www.colta.ru/articles/media/15442-tsarskie-ostanki-obratnyy-otschet

- CIPDH. 2021. “Notre Équipe [Our Staff].” http://cipdh.fr/notre-equipe/

- Dallas Committee to Stop FBI Repression. 2015. “Facebook Post by Aleksandr Ionov.”, May 20. https://www.facebook.com/csfrdallas/posts/httpstop-prisonorg201501151langen/464669140358128/

- Davlyatchin, I. 2019. “Zoloto Vagnera [Wagner’s Gold].” Rosbalt, February 19. https://www.rosbalt.ru/piter/2019/02/19/1764754.html

- Douzet, F. 2020. “Éditorial. Du Cyberespace À La Datasphère. Enjeux Stratégiques De La Révolution Numérique [Editorial. From Cyberspace to Datasphere. Strategic Stakes of the Digital Revolution].” Hérodote N°177-178 (2): 3–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.3917/her.177.0003.

- Dvuglavnii orel. 2017. “Russkoe Istoricheskoe Prosveshchenie Sdelalo Shag Vpered. Itogi Vserossiiskogo Obshchego Sobraniya Obshchestva ‘Dvuglavyi Orel’ [Russian Historical Upbringing Moved Forward. Results from the Pan-Russian General Conference of the Two-Headed Eagle].” Dvuglavnii oriol, November 8. Moscow. https://rusorel.info/v-rossii-sushhestvuet-moshhnoe-monarxicheskoe-dvizhenie-itogi-vserossijskogo-obshhego-sobraniya-obshhestva-dvuglavyj-orel/

- Dziadul, C. 2017. “Russian Channel Tsargrad Goes Off Air.” BroadbandTVNews, November 24. https://www.broadbandtvnews.com/2017/11/24/russian-channel-tsargrad-goes-off-air/

- Emaidan. n.d. “EMAIDAN.COM.UA.” Accessed 15 March 2021. https://builtwith.com/relationships/emaidan.com.ua

- EUDisinfoLab. 2020. “How Two Information Portals Hide Their Ties to the Russian News Agency Inforos.” June. https://www.disinfo.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/20200615_How-two-information-portals-hide-their-ties-to-the-Russian-Press-Agency-Inforos.pdf

- Fontanka.ru. 2019. “Peterburgskoe Izdanie, Blizkoe K Evgeniyu Prigozhinu, Rasproshchalos’ S Zhurnalistom, Podderzhavshim Ivana Golunova [A St Petersburg Publisher, Close to Yevgeny Prigozhin, Cut Links with Journalists Defending Ivan Golunov].” fontanka.ru, June 10. https://www.fontanka.ru/2019/06/10/154/?feed

- Foundation for National Values Protection. n.d. “About Us.” Accessed 2 October 2020. https://en.fznc.world/about-us/

- Galeotti, M. 2018. The Vory: Russia’s Super Mafia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Galeotti, M. 2019. Russian Political Warfare: Moving beyond the Hybrid. London: Routledge.

- Garmazhapova, A. 2013. “Gde Zhivut Trolli. Kak Rabotayut Internet-provokatory V Sankt-Peterburge I Kto Imi Zapravlyaet [Where are the Trolls Living? How Do the Internet Challengers Work and Who Is Directing Them].” Obshchestvo, September 9. https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2013/09/09/56265-gde-zhivut-trolli-kak-rabotayut-internet-

- Gerard, C. 2019. “Usines À Trolls Russes: De L’association Patriotique Locale À L’entreprise Globale [Russian Troll Factories: From Local Patriotic Association to Global Enterprise].” La Revue des médias, June 21. https://larevuedesmedias.ina.fr/usines-trolls-russes-de-lassociation-patriotique-locale-lentreprise-globale

- Greene, S. A. 2014. Moscow in Movement: Power and Opposition in Putin’s Russia. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Greenkomitet.ru. 2012. Accessed 15 March 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20120207091204/http://greenkomitet.ru/

- Hancock, K. J. 2007. “Russia: Great Power Image versus Economic Reality.” Asian Perspective 31 (4): 71–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/apr.2007.0003.

- Harding, L., and J. Burke. 2019. “Leaked Documents Reveal Russian Efforts to Exert Influence in Africa.” The Guardian, June 11. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/11/leaked-documents-reveal-russian-effort-to-exert-influence-in-africa

- Hosaka, S. 2019. “Welcome to Surkov’s Theater: Russian Political Technology in the Donbas War.” Nationalities Papers 47 (5): 750–773. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2019.70.

- Ihariliva, M. 2019. “Kraomita Malagasy—Le Partenariat Avec Les Russes Suspendu [Kraomita Malagasy—the Partnership with Russians Suspended].” L’Express de Madagascar, January 15. https://lexpress.mg/15/01/2019/kraomita-malagasy-le-partenariat-avec-les-russes-suspendu/

- Info, A. 2019. “Tchad: Afrique média désigne Hinda Déby pour le prix du mérite panafricain [Chad: Afrique Média Names Hinda Déby for the Pan-African Merit Award].” Alwihda Info, April 16. https://www.alwihdainfo.com/Tchad-Afrique-media-designe-Hinda-Deby-pour-le-prix-du-merite-panafricain_a72267.html

- IONOV Transcontinental. 2000a. Accessed 3 October 2020. http://www.it-int.one/

- IONOV Transcontinental. 2000b. “Ionov, Aleksandr Viktorovich.” Accessed 3 October 2020. http://www.it-int.one/ionov-aleksandr/

- Izvestiya. 2019. “V MITs Izvestiya Proidet Press-konferentsiya Po Teme Poddezhki Marii Butinoi [Izvestiya Holds a Press Conference on Maria Butina].” Izvestiya, May 27.Moscow. https://iz.ru/882565/2019-05-27/v-mitc-izvestiia-proidet-press-konferentciia-po-teme-podderzhki-marii-butinoi

- Kim, L. 2017. “Russian ‘Adhocracy’ Helps Create Cushion of Plausible Deniability for Putin.” NPR, July 20. https://www.npr.org/2017/07/20/538370622/russian-adhocracy-helps-create-cushion-of-plausible-deniability-for-putin

- Kislyakov, M. 2020. “V SSha Zadumalis’ O Sokrashchenii Voennykh Kontigentov V Afrike [The US Thinks about Reducing Its Military Contingent in Africa].” MK.ru, January 20. https://www.mk.ru/politics/2020/01/20/v-ssha-zadumalis-o-sokrashhenii-voennykh-kontingentov-v-afrike.html

- Kobia, R. 2019. “African Daily Voice—Rififi À La Tête De L’agence De Presse [African Daily Voice—Battles at the Press Agency Headquarters].” Afriqueactu.radio, May 13. https://www.afriqueactu.radio/les-actus/c/0/i/33630227/african-daily-voice-rififi-la-tete-de-lagence-de-presse

- Komitet Narodnogo Kontrol’ya. n.d. “Spravka: Malofeev Konstantin Valer’evich [Biographical Entry: Malofeev Konstantin Valer’evich].” Accessed 12 March 2021. http://comnarcon.com/444

- Kryshtanovskaya, O. V. 2005. “Anatomiya Rossiiskoi Elity.” In [Anatomy of the Russian Elite]. Moscow: Zakharov.

- Laruelle, M. 2016. “The Izborsky Club, or the New Conservative Avant-Garde in Russia.” The Russian Review 75 (4): 626–644. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/russ.12106.

- Latynina, Y. 2012. “Kakaya Svyaz’ Mezhdu Molokozavodami, Pedofilami, ‘Rostelekomom’ I Neudavshimsya Senatorom Malofeevym [What Is the Link between Milk Factories, Pedophiles, Rostelekom, and the Unsuccessful Senator Malofeev].” Novaya Gazeta, November 22. https://www.novayagazeta.ru/articles/2012/11/23/52462–kakaya-svyaz-mezhdu-molokozavodami-pedofilami-171-rostelekomom-187–i-neudavshimsya-senatorom-malofeevym

- Ledeneva, A. 2013. “Can Russia Modernise?” In Sistema, Power Networks and Informal Governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leetchi. n.d. “Afrique-Media-Bruxelles S’installe Dans La Capitale De L’Europe [Afrique-media-bruxelles Settles in Europe’s Capital].” Accessed 12 March 2021. https://www.leetchi.com/c/afrique-media-bruxelles

- Linvill, D. L., B. C. Boatwright, W. J. Grant, and P. L. Warren. 2019. “‘THE RUSSIANS ARE HACKING MY BRAIN!’ Investigating Russia’s Internet Research Agency Twitter Tactics during the 2016 United States Presidential Campaign.” Computers in Human Behavior 99 (October): 292–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.027.

- Machine, W. 2019. “lbihost.org.” Accessed 15 March 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20160101000000*/lbihost.ru

- Machine, W. 2020. “elenamizulina.ru.” Accessed 15 March 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/2020*/elenamizulina.ru

- MacKinnon, A. 2019. “Report: The Evolution of a Russian Troll.” Foreign Policy, July 10. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/07/10/the-evolution-of-a-russian-troll-russia-libya-detained-tripoli/

- Makarenko, G. 2015. “V Moskve Na Den’gi Blizkogo K Kreml’yu Funda Proidet S”ezd Separatistov [A Congress of Separatists Held in Moscow Funded by Money Close to the Kremlin].” RBC.ru, September 15. https://www.rbc.ru/politics/15/09/2015/55f6a58f9a7947405d1eed9e

- Makarenko, G. 2016. “V Moskve Vtoroi Raz Proidet Mezhdunarodnyi S”ezd Separatistov [A Second Congress of Separatists Organized in Moscow].” RBC.ru, September 13. https://www.rbc.ru/politics/13/09/2016/57d2d0a19a79472489b0d4c0

- Maldonaldo, M. 2020. “Russia’s Hardest Working Oligarch Takes Talents to Africa.” PONARS Eurasia Policy memo 672 (September). https://www.ponarseurasia.org/russia-s-hardest-working-oligarch-takes-talents-to-africa/

- Malofeev, K. 2014. “Interv’yu—Konstantin Malofeev, Osnovatel’ ‘Marshala kapitala’[Interview with Konstantin Malofeev, Marshall Capital Founder].” Vedomosti, November 13. http://www.vedomosti.ru/newspaper/articles/2014/11/13/v-sankcionnye-spiski-vklyuchali-posovokupnosti-zaslug

- Malofeev, K. 2019. “Konstantin Malofeev: ‘Russia Is a Partner of Strategic Importance to Africa.’” Roscongress, October 15. https://roscongress.org/en/materials/konstantin-malofeev-rossiya-dlya-afrikanskikh-stran-yavlyaetsya-prioritetnym-partnerom/

- Mandraud, I. 2017. “Tsarskaya Shkola V Rossii [A Tsarist School in Russia].” Le Monde (via INOSMI), April 7. https://inosmi.ru/social/20170407/239071082.html

- Marten, K. 2019a. “Into Africa: Prigozhin, Wagner, and the Russian Military.” PONARS Policy Memo 561 (January). https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:FxG5Et4g8SkJ:https://www.ponarseurasia.org/ru/node/10096+&cd=9&hl=fr&ct=clnk&gl=fr

- Marten, K. 2019b. “Russia’s Use of Semi-State Security Forces: The Case of the Wagner Group.” Post-Soviet Affairs 35 (3): 181–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2019.1591142.

- Marten, K. 2020. “Where’s Wagner? The All-New Exploits of Russia’s ‘Private’ Military Company.” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo 670 (September).

- Meduza. 2015. “Parad Suverenitetov. V Moskvu S”ekhalis’ Separatist so Vsego Mira [Parade of Sovereignties. Secessionists from All the World Met in Moscow].” Meduza, September 21. https://meduza.io/feature/2015/09/21/parad-suverenitetov

- Michel, C. 2019. “Leading Voices in Russian Interference Efforts Rally to Support Maria Butina.” ThinkProgress (blog), May 29. https://archive.thinkprogress.org/russian-malefactors-rally-for-maria-butina-bcd97b91749d/

- Michel, L. 2014. “La Russie sauve Afrique media de la ‘voyoucratie’ Canal+ [Russia Is Rescuing Afrique Media from Canal+ Mafia].” Luc Michel’s Transnational Action, August 12.

- Mueller, R. S. 2019. “Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election.” US Department of Justice (March). https://www.justice.gov/storage/report.pdf

- Nation-Europe. 2005. “Their ‘Europe’ Is Not Ours: PCN-NCP, the Party of the Unitary and Communitarian Europe, Says ‘No’ to the American False Europe of NATO and Capitalism!’.” Nation-Europe 43 (May): 39.

- Natostop.pl.ua. 2011. Accessed 15 March 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20110518143740/http://www.natostop.pl.ua/

- Olivier, M. 2019. “Russie-Afrique: Centrafrique, Le Pays Des Soviets? [Russia-africa: CAR, the Land of the Soviets?].” Jeune Afrique, August 20. https://www.jeuneafrique.com/mag/814887/politique/russie-afrique-centrafrique-bienvenue-au-pays-des-soviets/

- Parfent’eva, I., and V. Kozlov. 2019. “Investor Malofeev Stal Konsul’tantom Afrikanskikh Pravitel’stv [Investor Malofeev Became Consultant for African Governments].” RBC.ru, September 11. https://www.rbc.ru/business/11/09/2019/5d7796cc9a794731b3800996

- Peniguet, M. 2018. “USA Really, Un Nouveau Média Privé De Propagande Russe [USA Really, a New Private Medium Deprived of Russian Propaganda].” Le Grand Continent, April 30. https://legrandcontinent.eu/fr/2018/04/30/usa-really-un-nouveau-media-prive-de-propagande-russe/

- Pudovkin, Y. 2019. “Glaz’ev I Malofeev Rekomendovali Afrike Snizit’ Zavisimost’ Ot Zapada [Glazyev and Malofeev Recommended that Africa Reduce Its Dependency on the West].” RBC.ru, October 23. https://www.rbc.ru/politics/23/10/2019/5db043e99a794743f8855285

- Raviot, J.-R. 2018. “Putinism, a Praetorian System?.” In Notes de l’IFRI Russie/NEI/Visions, Vol. 106 (March).

- Reader, R. 2019. “The Safe Internet League.” The Russian Reader, August 12. https://therussianreader.com/2019/10/02/firewalling/

- Rid, T. 2020. Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare. New York: Farrar: Straus and Giroux.

- Rondeaux, C. 2019. “Decoding the Wagner Group: Analyzing the Role of Private Military Security Contractors in Proxy Warfare.” November 2019. https://d1y8sb8igg2f8e.cloudfront.net/documents/Decoding_the_Wagner_Group.pdf

- Rozhdestvensky, I., and R. Badanin. 2019. “Master and Chief: How Evgeny Prigozhin Led the Russian Offensive in Africa.” Proekt.media, March 14. https://www.proekt.media/en/article/evgeny-prigozhin-africa/

- Safe Internet League. n.d. “The Cyberguard.” http://ligainternet.ru/en/liga/activity-cyber.php

- Sal’manov, O. 2012. “Kto Spryatalsya V ‘Rostelekome’ [Who Was Hiding in Rostelekom?].” Vedomosti, December 17. http://www.vedomosti.ru/newspaper/articles/2012/12/17/kto_spryatalsya_v_rostelekome

- Ser’gina, E., and P. Kozlov. 2014. “‘V Sanktsionnye Spiski Vklyuchali Po Sovokupnosti zaslug—Konstantin Malofeev, Osnovatel’ ‘Marshal Kapitala’ [A Package of Famous People Joined the List of Sanctioned Peoples: Konstantin Malofeev, Marshall Capital Founder].” Vedomosti, November 13. https://www.vedomosti.ru/newspaper/articles/2014/11/13/v-sankcionnye-spiski-vklyuchali-posovokupnosti-zaslug?

- Shekhovtsov, A. 2015. “Far-Right Election Observation Monitors in the Service of the Kremlin’s Foreign Policy.” In Eurasianism and European Far Right: Reshaping the Europe-Russia Relationship, edited by M. Laruelle, 223–244. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

- Shekhovtsov, A. 2017. Russia and the Western Far Right. Tango Noir. London: Routledge.

- Shekhovtsov, A. 2020. “Fake Election Observation as Russia’s Tool of Election Interference: The Case of AFRIC.” European Platform for Democratic Elections, April. https://www.epde.org/en/news/details/fake-election-observation-as-russias-tool-of-election-interference-the-case-of-afric-2599.html

- Shevchuk, M. 2020. “Dve Rodiny. Natsional-patrioticheskie Partii V Bor’be Za Vnimanie Putina [Two Rodinas. National-Patriotic Parties in the Fight for Putin’s Attention].” Republic.ru, October 28. https://republic.ru/posts/98305

- Shleinov, R. 2013. “Vysokie Otnosheniya [High Relations].” Vedomosti, March 18. http://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/articles/2013/03/18/vysokie_otnosheniya

- Shultz, R. H. 1984. Dezinformatsia: Active Measures in Soviet Strategy. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Sokoloff, G. 1993. “La puissance pauvre: Une histoire de la Russie de 1815 à nos jours.” In [The Poor Great Power: A History of Russia from 1815 to Nowadays]. Paris: Fayard.

- Stelzenmüller, C. 2017. “The Impact of Russian Interference on Germany’s 2017 Elections.” Brookings Institution, June 28. https://www.brookings.edu/testimonies/the-impact-of-russian-interference-on-germanys-2017-elections/

- Stoeckl, K. 2020. “The Rise of the Russian Christian Right: The Case of the World Congress of Families.” Religion, State & Society 48 (4): 223–238. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09637494.2020.1796172.

- Syria2014. 2014. “Kto My [Who are We?].” Accessed 15 March 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20140624091651/http://syria2014.ru/kto-my

- Thiriart, J. 1984. L’empire Euro-Sovietique de Vladivostock à Dublin l’aprés-Yalta. La mutation du communisme. Essai sur le totalitarisme éclairé [The Euro-Soviet Empire from Vladivostok to Dublin. Post-Yalta. The Transformations of Communism. Essay on Enlightened Totalitarianism]. Charleroi: Editions Machiavel.

- A Today. n.d. “UATODAY.BIZ.” Accessed 15 March 2021. https://builtwith.com/uatoday.biz

- Tsargrad. n.d. “TSARGRAD.TV.” Accessed 15 March 2021. https://builtwith.com/relationships/tsargrad.tv

- US Department of Treasury. 2018. “Treasury Targets Russian Operatives over Election Interference, World Anti-Doping Agency Hacking, and Other Malign Activities.” December 19. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm577

- US Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Networks Providing Support to the Government of Syria, Including For Facilitating Syrian Government Oil Purchases from ISI.” November 25. 2015, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/pages/jl0287.aspx

- Vasilyeva, N. 2017. “Thousands of Russian Private Contractors Fighting in Syria.” Associated Press, December 12. https://apnews.com/7f9e63cb14a54dfa9148b6430d89e873/Thousands-of-Russian-private-contractors-fighting-in-Syria

- Volkov, V. 2002. Violent Entrepreneurs: The Use of Force in the Making of Russian Capitalism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Weiss, M., and P. Vaux. 2020a. The Company You Keep: Yevgeny Prigozhin’s Influence Operations in Africa. Washington, DC: Free Russia Foundation.

- Weiss, M., and P. Vaux. 2020b. “Russia Is Using Undercover Racists to Exploit Africa’s Anti-Racist Political Revolt.” The Daily Beast, September 8. https://www.thedailybeast.com/prigozhin-is-using-afric-to-exploit-africas-anti-colonial-political-revolt

- WHOXY Alexander. n.d. “WHOXY Domain Search Engine, Alexander Ionov.” Accessed 12 March 2021. https://www.whoxy.com/name/1479586

- WHOXY Fabrice. n.d. “WHOXY Domain Domain Search Engine, Fabrice Beaur.” Accessed 12 March 2021. https://www.whoxy.com/name/14733152

- Zibrova, E. 2019. “My Dolzhny Ne Sozhalet’ O Den’gakh, a Maksimal’no Ispol’zovat Kuplennoe. Konstantin Malofeev O Rabote S Afrikoi [We Don’t Have to Regret the Money Spent, but Make the Maximum Use of What Has Been Bought. Malofeev on His Work with Africa].” RT, November 7. https://russian.rt.com/business/article/684396-malofeev-intervyu-afrika