ABSTRACT

For more than two decades a key pillar of regime stability in Belarus was legitimation through economic stability and security, prompting experts to speak of a “social contract” between the state and its citizens. The 2020 protests, however, convey significant dissatisfaction with the Lukashenka regime across a broad social and generational base. By comparing survey data from late 2020 with data from 2011 and 2018, we examine changing attitudes towards democracy and state involvement in economic affairs. We find a departure from paternalist values, implying an erosion of the value base for the previous social contract. Belarusian society has become more supportive of liberal political and economic values. This trend is particularly driven by the older generation and does not exclude Lukashenka’s support base. Meanwhile, attitudes towards democracy and the market have implications for people’s social and institutional trust, preference for democracy, and political participation.

Students of authoritarianism used to explain the long-lasting stability of the autocratic Belarusian regime under Alyaksandr Lukashenka not only with reference to the excessive use of repression against political opponents. The stability of the Lukashenka regime was also said to rely on the legitimation derived from maintaining a Soviet-style welfare state (Way Citation2005; Cook Citation2007; Fritz Citation2007; Haiduk, Rakova, and Silitski Citation2009; Clem Citation2011; Balmaceda Citation2014; Yarashevich Citation2014; Pikulik Citation2019; Dimitrova et al. Citation2020). This led Belarusian experts to speak of a “social contract” that seemed to create a broadly shared public consent that the lack of political participation is rewarded with economic stability and security. Paternalist values favoring strong state intervention in the economy and social welfare were said to form the value base for the social contract with the state (Haiduk, Rakova, and Silitski Citation2009; Merzlou Citation2019; Shelest Citation2020).Footnote1 While recent studies pointed toward an erosion of that “social contract” as a result of deteriorating socio-economic conditions in Belarus over the past decade (Wilson Citation2016; Douglas Citation2020), we know little about the change in political and economic attitudes underpinning this development.

Against this backdrop, this paper addresses three questions: How have attitudes towards political participation and state intervention in economic and social affairs changed in Belarus over the past decade? Which parts of the population are the driving force behind change and/or continuity? How do political and economic attitudes relate to political participation as well as interpersonal and institutional trust? The first two questions help us to better understand the erosion of the previous social contract between state and citizens in Belarus, while the last question sheds light on the implications of our findings for Belarus’s regime trajectory and the strategic options Lukashenka or a potential autocratic successor will have to generate stability with other means than repression.

Considering the closed nature of Belarus’s authoritarianism – as marked by the absence of free and fair elections, a lack of horizontal accountability and political rights, combined with an all-dominating role of the ruling elite in the economic sphere and the control of mass media (Ademmer, Langbein, and Börzel Citation2019; Levitsky and Way Citation2010) as well as in the sphere of education (Manaev, Manayeva, and Yuran Citation2011)Footnote2 – we would not expect an increase in liberal attitudes in Belarus, neither in the political nor economic sphere. That is because autocracies are expected to undermine democracy-supporting attitudes and to foster autocracy-supporting ones (Rohrschneider Citation1999; Neundorf Citation2010). Further, it is often assumed that individuals adopt pro-democratic attitudes through mass media, public discourses, and/or the educational system (Bermeo Citation1992; Mishler and Rose Citation2002). As these spheres are controlled by the ruling elites in autocratic Belarus, this mechanism can hardly be at work. Rather, economic performance and the communist legacy seem to contribute to an approval of the autocratic regime (Klymenko and Gherghina Citation2012). Moreover, a departure from paternalist values – marked by support for a strong role of the state in the economy and social affairs – is highly unlikely, as paternalism is deeply rooted in Belarusian society, inherited from the USSR period (Merzlou Citation2019).

Therefore, it is puzzling that our analysis, based on a comparison of survey data generated in 2011, 2018, and late 2020 among Belarusians aged 18 to 64, reveals a shift in attitudes towards democracy and state intervention in social and economic affairs. Rather than revealing widespread paternalism, our findings show that Belarusians have become more liberal, both in political and economic terms: people are now more inclined to associate a democratic form of government with liberal rather than authoritarian traits than roughly a decade ago. Moreover, we find that people's attitudes towards state intervention in issues of social security and equality have changed in the time period under scrutiny. While Belarusians continue to be market-friendly, fewer Belarusians associate a democratic form of government with redistributive policies than in the past, in particular since 2018. In a similar vein, support for stronger state intervention in the well-being of citizens has been declining.

A second puzzling finding of our analysis relates to the intergenerational differences in attitudes towards democracy and state intervention in social and economic affairs that we can identify. Students of democratization often explain political liberalization with reference to underlying shifts in values, brought about – among other things – by education (Inglehart and Welzel Citation2005). In the context of Ukraine’s Orange Revolution, for example, some scholars noted a deep transformation of values and explained these developments with reference to the emergence of a new generation of young Ukrainians who travel abroad, study at American or European universities, and are exposed to Western media (Diuk Citation2006). Along similar lines, more recent studies on intergenerational differences in the post-Soviet context claimed that younger age groups, who have not lived through Communist rule, are more inclined to democracy than older age groups (Diuk Citation2012; Turkina and Surzhko-Harned Citation2014; Tucker and Pop-Eleches Citation2017, 134; Klicperova-Baker and Kostal Citation2018, 42).Footnote3 Younger age cohorts also reveal stronger preferences for self-enhancement and competitiveness regardless of the context, group status, and ethnic differences (Bushina and Ryabichenko Citation2018). Further, younger generations are more skeptical towards stronger state control over the economy and favor economic deregulation and competition. They also dislike redistributive policies (Turkina and Surzhko-Harned Citation2014). Along similar lines, Tucker and Pop-Eleches (Citation2017) find that older age groups, who have lived longer under Communism, are likely to support state control of the economy (182) and to favor state-provided social welfare (189).

The extent to which our data speaks to a different story is therefore surprising: in 2020, a liberal understanding of democracy as well as support for competition, private ownership, and individual responsibility increases with age. While a liberal understanding of democracy already prevailed among older age cohorts in 2011 (albeit at a lower level), opposition to state intervention in market dynamics and social issues has tended to increase with age over the past decade. In fact, people whose birth and adolescence coincided with Alyaksandr Lukashenka taking office in 1994 are far more likely to have an authoritarian understanding of democracy in 2020 than older generations. They are also more likely to favor a stronger state intervention in the economy. These findings suggest that the older generation in Belarus no longer seems to believe that the state can deliver on its past promises and is the key driving force behind growing societal preferences for political and economic liberalism.

To gain a better understanding of the implications of these findings for Belarus’s future political trajectory, we analyze how growing support for political and economic liberalization relates to actual support for democracy, institutional and interpersonal trust, and people's voting behavior. We examine actual support for democracy, because strong support for democracy can play into the hands of authoritarian regimes if people associate a democratic form of government with authoritarian components, such as a powerful army (Kirsch and Welzel Citation2019). We examine the link between institutional and interpersonal trust and attitudes towards democracy and the market, because in an authoritarian context strong institutional trust and weak interpersonal trust can undermine opportunities for democratic and economic development (Almond and Verba Citation1963; Putnam Citation1993). Finally, we analyze the link between voting behavior and attitudes toward democracy and the state’s role in the economy to reveal whether the growing political and economic liberalizations only extend to regime opponents or also include Lukashenka’s support base.

From the perspective of regime change (even if highly unlikely in the current situation), it is important to underline that Belarusians who support democracy tend to associate a democratic form of government with liberal rather than authoritarian components. Further, the quest for more political and economic liberalism goes hand in hand with lower trust in state institutions and is not limited to regime opponents. A significant obstacle to any further horizontal collaboration is that people who share liberal attitudes, in both political and economic terms, do not display higher levels of interpersonal trust.

An important caveat remains, however. Lukashenka’s support base is often said to consist of blue-collar workers, the elderly, and more religious people. The most recent 2020 data do not include respondents older than 64, and we therefore restricted our analysis accordingly. The reduced demands for stronger state involvement among the older age group in our sample, should, however, warn us against drawing simplistic conclusions about the support of elderly voters for the system in place. The disregard for the pandemic throughout 2020, but also the violence that grandchildren had to endure during the protests after the August election, may have severely shaken these people’s confidence in the regime.

Data and research design

For the analysis, we combined three data sets, namely, the World Values Survey (WVS) 2011, the European Values Survey (EVS) 2018, and a survey conducted by the Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS) in December 2020.Footnote4 The WVS and EVS were conducted face-to-face; for security reasons and given the restrictions related to the pandemic in 2020, our ZOiS survey was conducted online. A total of 1,535 people responded to the WVS; 1,548 to the EVS; and 2,002 people to the ZOiS survey. The age range included in the three samples differed, with WVS and EVS covering a spectrum ranging from 18 to 80+, whereas the ZOiS survey could only reliably reach out to the population aged 16 to 64.

Taking into account these differences in the sample composition, we singled out respondents aged 18 to 64 for our key analysis, as this was the overlapping group in terms of age. The samples also differ in terms of the settlement size in which respondents lived. WVS and EVS included respondents living in settlements with less than 20,000 inhabitants, who could, however, not be reached in a systematic way via an online survey. In total, this left us with 3,664 respondents of the same age and living in the same settlement size across the three surveys. We included the WVS and EVS respondents who did not overlap with the ZOiS survey as separate groups to understand whether these types of respondents differed in their political and social attitudes, and they are included in the full models (see the online appendix).Footnote5

It is beyond doubt that survey data generated face-to-face and data generated through an online sample are inherently different. However, in an authoritarian context with very active repression measures, it is by no means a foregone conclusion that a face-to-face survey will yield more reliable results. On the contrary, biases induced by the enumerator might be even higher in a situation where respondents feel that they might be monitored and there could be real-world implications for stating political and social preferences. The online survey, however, ensured the anonymity of respondents and the administrators of the ZOiS survey were able to verify in several other, notably open-ended questions, that respondents took the survey to heart. The time spent on responding – on average 34 minutes – also indicates that respondents did not rush through it. Moreover, in the analysis we always performed a robustness check separating the individual years in the models; for readability, we aggregated the results in the presentation.

Dependent variable: views on democracy and the market

All three datasets included an identical set of questions on attitudes towards the market and political questions that required respondents to rank the importance of several items. These questions were at the center of our first analysis. We transformed 12 out of the total of 13 questions into five indices representing attitudes towards social and political questions.Footnote6

One set of questions allowed us to understand what people consider to be “the essential characteristics of democracy” on a scale from 1 to 10 (). We divided these items into three dimensions: one centered on aspects linked to a liberal understanding of democracy; one that illustrates authoritarian traits; and one that emphasizes redistributive aspects. We presume that people share a liberal understanding of democracy if they emphasize free elections and the protection of political and civil liberties, whereas an authoritarian notion of democracy is shared by people who consider the defining feature of democracy to be the extra political powers enjoyed by religious authorities or the military (Welzel Citation2011; Kirsch and Welzel Citation2019). An egalitarian notion of democracy considers socio-economic inequalities as a major impediment to the actual exercising of political rights and civil liberties (Coppedge et al. Citation2011, Citation2015). Redistributive policies are therefore a defining feature of the egalitarian notion of democracy (Welzel Citation2011).

Table 1. Elements for the question: “We would now like to know what you consider being the essential characteristics of democracy. Use this scale where 1 means ‘not at all an essential characteristic of democracy’ and 10 means ‘an essential characteristic of democracy.’”

A further set of questions revolved around economic aspects and asked respondents to state their preferences regarding how the relationship between the state and the economy should be organized (). For these fourth and fifth indices, we included all four questions that were asked across all three surveys to measure commitments to state involvement in market dynamics and social issues, with the latter centering notably on questions of redistribution. On one end of the continuum is a strong preference for redistribution undertaken through the government, as indicated by support for income equality and government responsibility for everyone’s basic needs. Questions of state-market relations are captured by respondents’ preference for government or private ownership of firms and preference (or not) for competition.

Table 2. Elements for questions involving the level of state involvement in market dynamics and social issues

All questions required respondents to rank their preference on a ten-point scale and we constructed five indices based on the responses. More precisely, we aggregated these raw scores taking into account the number of valid responses given, so that, for instance, a respondent who assigned 10 points to two of the three items in the liberal index questions received the full score of 30 on that index. This was done in order to avoid a situation, for instance, where a respondent who only provided one 10-point answer on one of the three variables of the liberal index would receive 10 points, thus placing that person in the lower range.

In terms of the outcome variables, we were interested in two blocks. A first one revolves around institutional and interpersonal trust. Here, we were interested in understanding how a particular understanding of democracy and preferences for the organization of the relationship between the state and the market relate to the trust people have in other citizens and in the country’s institutions. Do liberal understandings of democracy correlate with higher interpersonal and institutional trust and authoritarian understandings with lower interpersonal and institutional trust? Interpersonal trust was operationalized by eliciting responses to a question that asked whether people who one meets for the first time can be trusted.Footnote7 To measure institutional trust, we aggregated several trust questions relating to various political and security institutions, notably the parliament, the judiciary, the president, the police, the secret service, and the armed forces. Since we were not interested in specific institutions in this analysis, we aggregated the responses into an overall trust ranking for state institutions.Footnote8 A separate analysis was done on the extent to which people trust the church and the media. The church has time and again, in particular at the local level, acted in more independent and critical ways, and some of the media remained beyond the tight control of the state during the time of analysis and therefore deserve to be analyzed in their own right.

Another set of variables revolves around political behavior and attitudes. We were particularly interested in how important respondents considered a democratic form of government to be. The 2020 ZOiS survey asked respondents the following question: “People often compare democratic and non-democratic regimes. Which of the following statements do you agree with the most? Please select only ONE most suitable option.” People had a choice between the following three responses: “Democracy is preferable to any other kind of government”; “Under some circumstances, an authoritarian government can be preferable to a democratic one”; “For people like me, it doesn’t matter whether we have a democratic or non-democratic regime.” We transformed these responses into a numerical scale with three values reflecting the importance attributed to democracy. In the WVS and EVS surveys, respondents had to rank the importance of democracy on a scale from 1 to 10, which we also transformed into a numerical scale with three items.Footnote9 Given the different wording of the question, a direct analysis was not undertaken and the models were computed separately for each year.

Lastly, we were interested in understanding how respondents participated in elections and whether they participated in protests. The EVS and WVS surveys only asked about electoral participation, not about candidate choice. The latter did, however, feature in the ZOiS survey and was used for the analysis. Since the question about protest participation was not asked in the 2011 survey, we restricted our analysis to the two most recent survey years. In all cases we were primarily interested in determining whether a particular type of political behavior and attitudes was linked to a liberal or authoritarian understanding of democracy or different understandings of the relationship between the state and the market.

Independent variables

In our first analysis we are interested in finding out who shares certain attitudes towards democracy and state intervention in market affairs and social issues in Belarus. Existing research on attitudes towards democracy and the market suggests a number of critical individual-level factors that are treated here as independent variables to reveal whether any of them displays a statistical significance that warrants more in-depth analysis.Footnote10 These variables are as follows:

Education: We recoded the various questions asked about educational achievement into a three-scale variable, where 1 is the lowest possible value, referring to primary school education, and 3 the highest, referring to university-level education.

Wealth: The ZOiS survey used a standard income affordability scale asking what respondents can easily acquire, whereas the WVS and EVS surveys asked about the self-perceived financial positioning of the household. We transformed all the data into a three-step scale with low, medium, and high income.

Employment type: A range of questions on employment type was recoded into four categories in order to capture people who were employed (full-time or part-time), unemployed, students, or retired (and others).

Religion: In the case of Belarus, it was important to distinguish between those who declare themselves to be Orthodox, those who are part of the Protestant or Roman Catholic churches, and those who do not practice any religion. We recoded the responses into these response categories and included the categorical variable in the model.

Age was included as a continuous variable in the analysis.

Gender was included as a dummy variable, with 1 for male respondents.

Population strata were recoded on a four-point scale, with thresholds at: less than 20,000 inhabitants; between 20,000 and 99,999; between 100,000 and 499,999; and more than 500,000. Respondents in rural areas with less than 20,000 inhabitants are part of the 2011 and 2018 surveys and included in the full regression models (see online appendix).

While most of these variables are linked to socio-economic status, religion underpins the ideological predisposition of respondents.

In our second analysis we consider how the growing liberal understanding of democracy and increasing market-friendliness among Belarusians relate to trust, actual support for democracy, and political behavior, in order to better understand the implications of changing or persisting attitudes towards democracy and the market for Belarus’s potential political trajectory.

In authoritarian settings, trust values tell us much more about underlying political and social preferences than electoral votes. Previous surveys among Belarusians revealed stagnating or even declining trust in state institutions over the last few years (Bertelsmann Stiftung Citation2018; Krawatzek Citation2019), indicating the malfunctioning of the old social contract. At the same time, authoritarian regimes are also marked by low levels of interpersonal trust, which, among other obstacles, hinders horizontal cooperation. Against this background, we would expect those with more liberal political and economic attitudes to display lower levels of trust in state institutions and higher levels of interpersonal trust. Further, we consider attitudes towards the importance of democracy. From the perspective of political regime change, widely shared liberal notions of democracy can undermine the legitimacy of authoritarian regimes, if a liberal understanding goes hand in hand with widespread support for democracy. Conversely, an authoritarian understanding of democracy plays into the hands of an authoritarian regime if citizens articulate strong support for democracy (Kirsch and Welzel Citation2019). To understand which dynamic is at play in Belarus, we analyze how support for democracy is linked to a particular understanding of democracy. Finally, we want to understand how attitudes towards democracy and the market relate to participation in national elections.

Analysis and interpretation

Political and economic liberalization

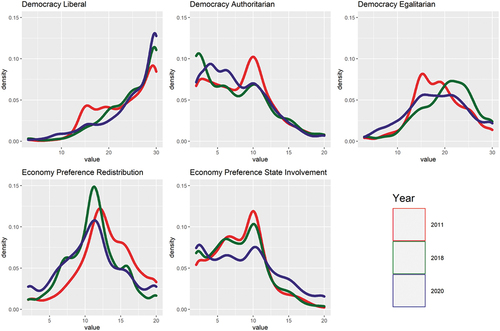

The five indices at the heart of the analysis already reveal some important insights into how Belarusians understand democracy and their economic preferences over time (). The density plots below convey the prominence of each value on the respective index.

The majority of Belarusians associates a democratic form of government with liberal rather than authoritarian components in the time period under scrutiny (2011–2020). On average, support for liberal components has been increasing across the three surveys, indicating that a growing number of respondents believe that democracy enables their political participation in free elections, equality of men and women, and the existence of civil rights. On the other hand, for a few Belarusians, authoritarian traits are central to their understanding of democracy in the time period under scrutiny. Associations with illiberal components, such as the rule of the military or religious leaders, were on average markedly lower in 2020 than in previous years, and were highest in 2011, when a still sizeable share of respondents scored a value of 10 on that index.

Support for egalitarian notions of democracy declined considerably from 2018 to 2020, with fewer and fewer Belarusians associating a democratic political system with redistributive policies. This association of democracy with egalitarian components is also very dispersed across respondents, notably in 2020.

Lastly, in the period from 2011 to 2020 the population’s economic preferences have generally moved away from wanting the state to be heavily involved in either the market or questions of redistribution. Whereas state involvement in redistribution was seen as desirable by a large share of the respondents in 2011, indicated by the right tail of the distribution, this value had already moved in 2018 and was at its lowest in 2020. When it comes to views on the desirability of state involvement in the market, we identified only a slight change from 2011 through to 2020, but overall responses have become more dispersed over time.

These results reveal a partial liberalization of Belarusian society over the last 10 years, more in political but also in economic terms: despite the authoritarian nature of the ruling regime, the majority of Belarusians has developed a stronger liberal understanding of democracy over the past decade. This is insofar surprising, as people living in authoritarian regimes tend to share an ambiguous understanding of democracy in the sense that authoritarian notions of democracy mix with or even overshadow liberal notions (Kirsch and Welzel Citation2019, 60). When it comes to their economic preferences, Belarusians are on average slightly more market-friendly today than they were in 2011. They are significantly less supportive of state intervention in social issues than 10 years ago. Put differently, an increasing number of Belarusians does not think that state intervention in social and economic affairs is the most efficient mechanism to provide public goods.Footnote11 The 2020 ZOiS survey shows that 52% of the respondents back greater individual responsibility in general, while 46% tend to dislike state intervention to ensure income inequality. This is an intriguing finding since Belarusian society is traditionally known for its paternalism based on the notion of a strong state presence in the economy and in regulating the well-being of citizens (Haiduk, Rakova, and Silitski Citation2009; Merzlou Citation2019; Shelest Citation2020).

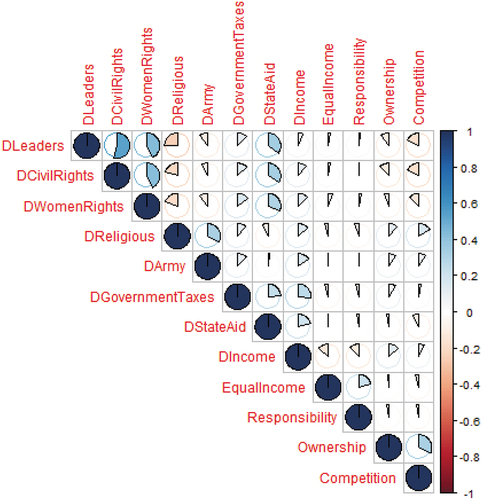

The indices themselves are internally consistent over time. The three variables in the liberal index correlate highly with one another (the first three variables in the correlation plot), as do the two statements included in the authoritarian traits of democracy index (). The egalitarian aspects correlate positively with many aspects, and most importantly, the liberal components of democracy correlate positively with state aid for the unemployed. Lastly, the views on economic preferences for state involvement in the market and redistribution correlate strongly with one another.Footnote12

Figure 2. Correlation plot for individual variables across the five indices for the three survey years.

The correlations across the five indices confirm that these indices distinguish different dimensions across the political, economic, and social spectrum. The liberal score correlates negatively with the authoritarian score; the view that redistribution is central for democracy relates positively to liberal and authoritarian understandings of democracy; and the scores for economic preferences regarding distribution show no correlation with understandings of democracy. A preference for more state involvement in the market relates positively with an understanding of democracy that emphasizes authoritarian components.

Who shares liberal attitudes?

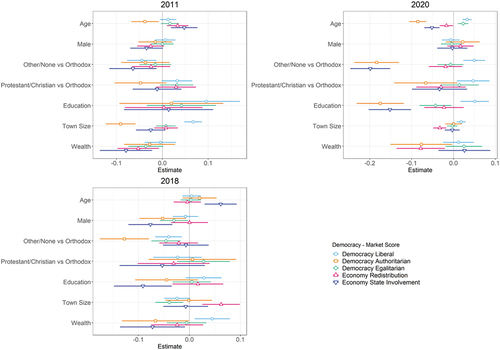

Our first analysis identifies the kind of respondents that linked with the different indices we derived. For that purpose, we took the aggregated scores on the respective indices and performed five Poisson regressions to account for the fact that the dependent variable is a count variable (). We undertook the regressions separately for each year as well as on the aggregate level, when we added the year in which the survey was conducted as a variable. See the online appendix for full details of the regressions.

Our multivariate analysis reveals that the age of respondents has the strongest effect on people's attitudes towards democracy and state intervention in the economy. Strikingly, however, particularly in a comparison of the results for 2020 and 2011, this effect is not in the direction the literature on intergenerational differences in post-Soviet societies would lead us to expect: older people associate more liberal and egalitarian components with democracy in 2020, while young people mentioned authoritarian elements in 2011 and 2020. The shift in economic preferences by age is also confirmed by the analysis, with older people preferring more state involvement in 2011 and younger ones in 2020. For 2018, only a preference for state economic involvement sets young people apart. We will zoom in on these counterintuitive results further below.

The relevance of gender is surprisingly low, although women are slightly more likely to demand state involvement in the market in 2011 and 2018. Religious affiliation is, however, an important factor behind these views on democracy and the market. Particularly in 2020, those respondents self-identifying as Orthodox stand out, with much higher values on the authoritarian index as well as a stronger preference for economic redistribution compared to non-believers. The difference with Protestants or Catholics is not statistically significant. When it comes to views on the political component of democracy and economics, the picture is less clear-cut than in previous years. Education is highly relevant, notably in 2020, with better educated individuals mentioning liberal elements more frequently and being less likely to associate the rule of religious leaders or the army with democracy. Lastly, a lower level of education correlates with a higher preference for state involvement in market dynamics in 2018 and 2020. The financial situation does not play a significant role in 2020, whereas in previous years better-off individuals tended to be more market-friendly.

We will now take a closer look at the link between age and attitudes towards democracy and the market, so as to better understand the dynamics at work here. Since younger generations are likely to experience different existential conditions from the ones that shaped older generations (Abramson and Inglehart Citation1992; Schwartz Citation2006), we would expect to see differences in the value preferences of older and younger generations. Factors such as physical aging and the growing importance of family and children among older age groups are assumed to increase preferences for (economic) security and stability (Schwartz Citation2006).

In line with this assessment, scholarship on intergenerational relations in the post-Soviet context has identified profound generational splits in political and social views. In her comparative study on youth-led protest movements in Russia, Ukraine, and Azerbaijan, Diuk (Citation2012) portrayed the younger generation as a voice demanding political change. In contrast, older generations seem to be inclined to authoritarianism and have a low estimation of democracy (Klicperova-Baker and Kostal Citation2018, 42; Turkina and Surzhko-Harned Citation2014). Previous studies on intergenerational differences in the post-Soviet context also revealed stronger preferences for self-enhancement and competitiveness among younger generations (Bushina and Ryabichenko Citation2018) as well as for market-friendly policies and limited state intervention in social affairs (Turkina and Surzhko-Harned Citation2014). In Belarus, fears about a subversive potential of young people led the regime to integrate the young generation into state-controlled youth movements since the early 2000s, way before similar developments began in Russia (Hall Citation2017; Silvan Citation2020).

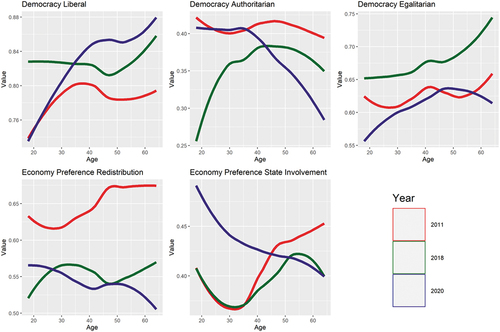

Against this background, the picture that emerges here is notable in several respects (). When it comes to a liberal understanding of democracy (“Democracy Liberal” score), the newest data from 2020 reveal a remarkable difference between young and old: younger people are significantly less likely to state that liberal components are essential characteristics of democracy, whereas older people (40+) tend to associate liberal aspects (free elections, political and civil rights) with democracy at much higher rate. Differences in age were of little importance in 2018 and – to a lesser extent – in 2011, but they are a driving factor in the current situation.

Figure 4. Response variation by age on the five indices measuring views on democracy and the market in Belarus.

In terms of an authoritarian understanding of democracy (“Democracy Authoritarian” score), the age of respondents was not a significant factor in 2011. However, in 2018, younger respondents, aged 18 to 30, and those older than 50, were less likely to mention authoritarian components than middle-aged people; and in 2020, younger respondents aged 18 to 35 were more likely to state that the army and religious leaders are essential for democracy. This is a remarkable finding, which may be explained by the impact of a streamlined educational system and the early introduction of social structures such as the state-sponsored Republican Union of Youth (BRSM) – with official membership numbers somewhere above 500,000 (Silvan Citation2020, 1323) – despite its failure to enable the genuine career advancement of young people.Footnote13

The understanding of democracy in egalitarian terms – e.g. equality and social justice (“Democracy Egalitarian” score) – has also shifted significantly over time. In 2020, middle-aged respondents, between 35 and 60 in particular, were likely to link democracy with social aspects, and the overall 2020 value was way lower than in 2018, when a pronounced difference between age groups could also be identified, with higher support among respondents older than 50 years.

Compared to 2011, the preference for strong state intervention in economic redistribution (“Economy Redistribution” score) has dropped markedly. The difference by age is, however, relatively minor. Whereas people older than 45 years tended to prefer redistribution back in 2011, this is no longer the case. Now, in 2020, it is young people who have a slightly higher preference for redistribution.

There is a noteworthy development when it comes to the age distribution, with respondents younger than 40 being more pronounced in their preference for state involvement in market affairs (“Economy State Involvement” score) in 2020, unlike previous years when that tended to be the stance of older people. The observed shift in economic attitudes across generations could be the result of the direct experience of a dysfunctional state-led economic and social welfare system on the part of the older age cohort. This might have led to a certain disillusionment among that age cohort, which might have impacted less on young people.

Summing up, as indicated by the most recent ZOiS survey, the political and economic liberalization of Belarusian society seems to be driven in a substantive way by the older rather than the younger generation, questioning conventional wisdoms about younger age groups as potential drivers of political change. This analysis considered in particular the effect of age at every moment in time – for an analysis of the different cohorts behind these age groups, the online appendix provides further analysis and context.

Trust, political behavior, and attitudes in relation to understandings of democracy and the market

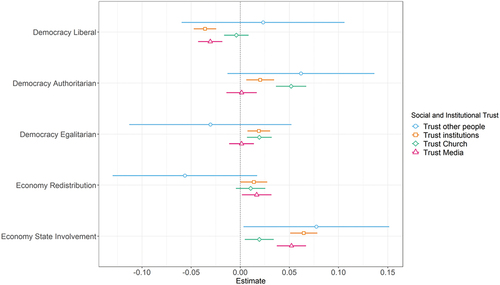

To assess the relationship between trust and attitudes towards democracy and the market, we used a proportional odds model with a dependent variable consisting of four categories for institutional trust, and a binary logistic regression for interpersonal trust, with a dependent variable coded as yes or no (). Somewhat surprisingly, in the case of interpersonal trust, none of the five indices seems to relate to whether or not people trust other people (who they encounter for the first time). This is insofar worrisome as high levels of interpersonal trust provide the social context for the emergence and maintenance of liberal democracies and effective economies (Almond and Verba Citation1963; Putnam Citation1993).

Figure 5. Proportional odds model showing relationship between trust and understandings of democracy, the state, and the market in Belarus.

By contrast, trust in various Belarusian institutions relates clearly to the different indices that we derived above. Trust in state institutions is an aggregate of political (president, parliament), security (armed forces, police), and judiciary (justice system), while we kept media as well as the church apart, assuming that different patterns can be observed across these institutions. Trust in state institutions is indeed strongly correlated with the understandings people hold of democracy, but also with their preferences for the relationship between the market and the state. People who are more likely to associate democracy with liberal components are also more likely to distrust the state media or state institutions in general, though they do not differ from the rest of the population in terms of their trust towards the church. People with higher values on the authoritarian index are more likely to trust the diversity of state institutions and in particular the church, as are people who score high on the egalitarian index. Preferences for economic redistribution matter only little for institutional trust, although preferences for a more active role of the state in market affairs correlates with high trust values in the various state institutions.

From the independent variables describing individual characteristics (socio-economic status, ideological predisposition) – see the online appendix for full details – it is noteworthy that female respondents, across all years, express higher social and institutional trust values. Students indicate higher interpersonal trust, also speaking to their horizontal ties and involvement in associations and other trusted networks. Employees in the public sector, across all three survey years, express high interpersonal trust as well as trust in state institutions and the media.

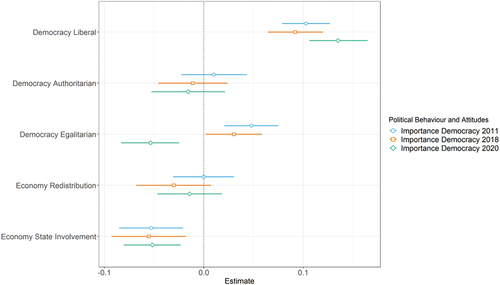

Further, we considered the relationship between political behavior and attitudes, on the one hand, and understanding of democracy and the market on the other. We begin with attitudes towards the importance of democracy (). From the perspective of political regime change, widely shared liberal notions of democracy can undermine the legitimacy of authoritarian regimes, if a liberal understanding goes hand in hand with widespread support for democracy. Conversely, an authoritarian understanding of democracy plays into the hands of an authoritarian regime if citizens articulate strong support for democracy (Kirsch and Welzel Citation2019). To understand which dynamic is at play in Belarus, we analyzed how support for democracy is linked to a particular understanding of democracy. We split the data into three models, as the question was not asked the same way across the three surveys. Across all years, people who consider liberal elements to be central for democracy are also more likely to state that democracy is more important for them, with no corresponding effect for people who associate democracy with authoritarian elements. However, in 2011 and 2018, people who highlighted egalitarian components were more likely to favor democracy, whereas the opposite is the case in 2020. And lastly, those favoring less redistribution and state involvement in the economy are also more likely to think that democracy is important for them.

Figure 6. Proportional odds model showing relationship between political attitudes (importance of emocracy) and understandings of democracy, the state, and the market in Belarus.

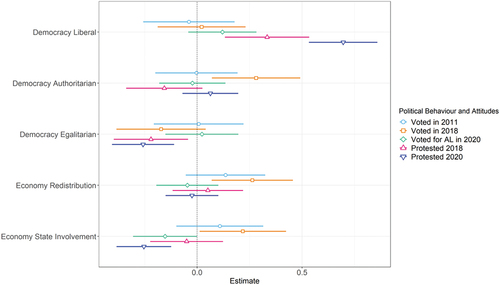

Finally, looking at the likelihood of having participated in national elections, it is striking that hardly any of the five indices seem to matter a great deal, as they mostly fail to achieve conventional levels of statistical significance (). The only exception were people who mentioned that they voted in 2018. This finding is particularly noteworthy with regard to the 2020 ZOiS survey that asks specifically about the candidate a respondent voted for, whereas the WVS/EVS only enquire into electoral participation.

Figure 7. Proportional odds model showing relationship between political attitudes (voting and protest activity) and understandings of democracy, the state, and the market in Belarus.

While the support base for Lukashenka has been usually associated with people who favor his program of redistribution or are more likely to dismiss liberal democratic elements, the results of the 2020 survey reveal that people who voted for Lukashenka can no longer be clearly associated with these attitudes.

The likelihood of having participated in protests also points to an intriguing development. As the question was not asked in 2011, we only considered the 2018 and 2020 data. The 2020 protests were much more clearly carried out by people who viewed liberal democratic elements as essential characteristics of democracy, and they were also less likely to mention egalitarian aspects or to favor a more interventionist state when it comes to market dynamics and redistributive policies. This finding underlines the highly politicized nature of the most recent protests and the existence of a tangible ideational profile of the protesters. Although participants in previous protests do not look completely different, the magnitude of the liberal score was significantly lower, and also, people who mentioned authoritarian elements (rule by the church or the army) were somewhat less likely to have participated in past protests. However, participants in previous protests do not differ from current protesters when it comes to their preference for redistribution.

Despite the authoritarian nature of the ruling regime, our results show that the majority of Belarusians have developed a stronger liberal understanding of democracy over the past decade. Further, the political and economic preferences of Lukashenka’s support base have become harder to pin down for the regime, while those who actively oppose the regime are no longer willing to give up on political participation and are ready to accept lower state intervention in social and economic affairs. It seems therefore that the societal basis for the old contract has started to erode both among Lukashenka’s support base and among regime opponents, and the beginning of this process can be traced back to well before the 2020 protests.

Conclusion

For a long time the stability of the Lukashenka regime relied not only on the excessive use of repression, but also on the provision of economic and social security that led Belarusian citizens to accept authoritarian rule. We have argued that the value base for this social contract has been eroding over the past decade. To substantiate this argument, this paper investigated changing attitudes towards democracy and the market among Belarusians on the basis of survey data generated in 2011, 2018, and 2020. Our analysis reveals a political and economic liberalization of Belarusian society over the last 10 years: as of late 2020, Belarusians are as market-friendly as in 2011, but they have become less supportive of state intervention in social issues over the past decade. Further, they are much more likely to mention liberal elements as central for democracy, while convictions that authoritarian elements are key to democratic forms of government have weakened. Put differently, people do not believe that the state can deliver what it has promised for so long and they have lost their illusions about the potential benefits of a strong interventionist state. They are, moreover, less inclined to give up political participation.

Strikingly, the erosion of the value base for the previous social contract extends to Lukashenka’s support base. True, this support base is more likely to appreciate authoritarian traits as central for democracy and is in favor of redistribution, but it is a shrinking part of the population based on our data. While those sharing liberal attitudes are more likely to distrust state institutions, they are not confined to the group participating in political protests or avoiding participation in national elections.

A further intriguing finding of this paper relates to intergenerational differences. We can show important differences across generations, although not in the direction that one might intuitively expect. Young people are more inclined to demand state intervention in the economy and social affairs and more likely to associate authoritarian traits with democracy. At this point we can only speculate about the impact of the seemingly effective co-optation strategies embodied in Belarus’s streamlined education system, and the older cohort’s stronger exposure to an increasingly ineffective state-led economic and social welfare system. Future research will need to address this puzzling outcome in more detail and also devote attention to it in a comparative perspective. This finding raises further doubts about the efficacy of the Lukashenka regime’s legitimation efforts vis-à-vis its traditional support base, which used to include the elderly.

What the analysis has also revealed is the important link between political ideals and social and political attitudes and behavior. Social and institutional trust links in to some extent with ideas of democracy and the market; political involvement such as voting and participation in protests as well as views on the importance of democracy strongly relate to the views and ideals people hold on democracy and the market. At the same time, low interpersonal trust may work against democratic and economic development in Belarus. This is even more worrisome given that interpersonal trust is unlikely to increase in the context of growing repression.

Our findings imply that the observed value change among Belarusians creates a dilemma for Lukashenka or a potential autocratic successor: ignoring the observed trends would mean that the state devotes even more resources to maintaining its rule through repression. This is the current approach of the Lukashenka regime, but doubts arise as to whether it is a viable strategy for maintaining stability in the medium to long term. Accommodating at least some demands for greater political participation at the expense of a more limited state provision of social welfare would, however, necessitate certain political and economic reforms that go against the logic of the Lukashenka regime. A rise in political competition could pave the way towards a less predictable political regime that comes close to what Levitsky and Way (Citation2010) call “competitive authoritarianism.” Market-friendly reforms could further damage existing patronage networks that are key for co-opting Lukashenka’s supporters within the state apparatus. Last but not least, a strong commitment to democratic ends among regime critics is conceived of as an important scope condition for avoiding authoritarian backtracking in a post-revolutionary context (Beissinger Citation2013). Although the brutal crackdown by Belarusian security forces considerably weakened the protest movement in recent months, this shared commitment in liberal attitudes poses a risk to any future autocratic regime in the country.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. See also Ralph Clem (Citation2011): “[Belarusian; Authors] citizens have agreed to be governed in an authoritarian manner in return for benefits bestowed by an economy dominated by the state.”

2. See Lü (Citation2014) and Kennedy (Citation2009) for the importance of educational systems in authoritarian settings more generally.

3. But see also Lechler and Sunde (Citation2019), who found that support for democracy increases with age but declines with expected proximity to death.

4. For more details on the ZOiS survey, see https://en.zois-berlin.de/publications/belarus-at-a-crossroads-attitudes-on-social-and-political-change.

5. The non-overlapping group included 302 respondents older than 64 years living in settlements with more than 20,000 inhabitants; 151 respondents older than 64 years living in settlements with less than 20,000 inhabitants; 905 respondents aged between 18 and 64 living in settlements with less than 20,000 inhabitants; and 63 respondents aged 16 to 17. They were included in the models separately.

6. We excluded one question on the essential characteristics of democracy – “People obey the rules” – as it did not align with our theoretical expectations and also showed no clear relationship to other questions used to generate our indices.

7. In the 2020 ZOiS survey, the following question was asked: “Do you generally trust people you meet for the first time?” In the 2018 EVS survey and the 2011 WVS surveys, people read “Most people can be trusted” with two answer options to select from, namely “most people can be trusted” or “need to be very careful.” We dichotomized these three variables and analyzed the combined data (in the main part of the paper) and provide the separate analysis in the online appendix.

8. We also analyzed the individual institutions separately, but the differences in coefficients are not of greater relevance.

9. We aggregated responses 1 to 4 into the lowest importance granted to democracy, 5 and 6 into the middle responses, and 7 to 10 into the highest importance.

10. The literature on which we base the individual-level factors is comprehensive, but see, for instance, Przeworski (Citation1991); Mishler and Rose (Citation1996), Tucker and Pop-Eleches (Citation2017), Neundorf and Soroka (Citation2018), and Lechler and Sunde (Citation2019).

11. A survey from August to September 2019 identified a desire for economic reform among more than half of Belarusians, with people being prepared to accept the negative consequences of reforms for several years (see https://thinktanks.by/project/2020/01/14/belorusy-ne-veryat-chto-mogut-povliyat-na-gosudarstvo-i-vse-menshe-polagayutsya-na-nego.html; see also Shelest Citation2020).

12. See the online appendix for the correlation of these indices across the different survey years.

13. Relatedly, a recent study by Dinas and Northmore-Ball (Citation2020) shows that authoritarian states use schools for indoctrinating certain political beliefs and attitudes that are in line with authoritarian regimes. Belarus is included in their sample.

References

- Abramson, P.R., and R. Inglehart. 1992. “Generational Replacement and Value Change in Eight West European Societies.” British Journal of Political Science 22 (2): 183–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400006335.

- Ademmer, E., J. Langbein, and T.A. Börzel. 2019. “Varieties of Limited Access Orders: The Nexus between Politics and Economics in Hybrid Regimes.” Governance 33 (1): 191–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12414.

- Almond, G.A., and S. Verba. 1963. Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Balmaceda, M. 2014. “Energy Policy in Belarus: Authoritarian Resilience, Social Contracts, and Patronage in a Post-soviet Environment.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 55 (5): 514–536. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2015.1028083.

- Beissinger, M. 2013. “The Semblance of Democratic Revolution: Coalitions in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution.” American Political Science Review 107 (3): 574–592. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000294.

- Bermeo, N. 1992. “Democracy and the Lesssons of Dictatorship.” Comparative Politics 24 (3): 273–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/422133.

- Bushina, E., and T. Ryabichenko. 2018. “Intergenerational Value Differences in Latvia and Azerbaijan.” In Changing Values and Identities in the Post-Communist World, edited by N. Lebedeva, R. Dimitrova, and J. Berry, 85–98. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Clem, R.S. 2011. “Going It Alone: Belarus as the Non-European European State.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 52 (6): 780–798. doi:https://doi.org/10.2747/1539-7216.52.6.780.

- Cook, L.J. 2007. Postcommunist Welfare States: Reform Politics in Russia and Eastern Europe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Coppedge, M., J. Gerring, D. Altman, M. Bernhard, S. Fish, A. Hicken, M. Kroening, et al. 2011. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: A New Approach.” Perspectives on Politics 9 (2): 247–267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592711000880.

- Coppedge, M., S. Lindberg, S.E. Skaaning, and J. Teorell. 2015. “Measuring High Level Democratic Principles Using V-Dem Data.” Varieties of Democracy Institute, University of Gothenburg, Working Paper 6, May.

- Dimitrova, A., H. Mazepus, D. Toshkov, T. Chulitskaya, N. Rabava, and I. Ramasheuskaya. 2020. “The Dual Role of State Capacity in Opening Socio-Political Orders: Assessment of Different Elements of State Capacity in Belarus and Ukraine.” East European Politics 37 (1): 19–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2020.1756783.

- Dinas, E., and K. Northmore-Ball. 2020. “The Ideological Shadow of Authoritarianism.” Comparative Political Studies 53 (12): 1957–1991. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019852699.

- Diuk, Nadia M. 2006. “The Triumph of Civil Society.” In Revolution in Orange, edited by A. Aslund and M. McFaul, 69–84. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment.

- Diuk, Nadia M. 2012. The Next Generation in Russia, Ukraine, and Azerbaijan: Youth, Politics, Identity, and Change. Plymouth: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Douglas, N. 2020. “From the Old Social Contract to a New Social Identity.” Centre for East European and International Studies, ZOiS Report 6/2020.

- Fritz, V. 2007. State Building: A Comparative Study of Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus and Russia. Budapest: Central European University Press.

- Haiduk, K., E. Rakova, and V. Silitski. 2009. Social Contracts in Contemporary Belarus. St. Petersburg: Nevsky Prostor.

- Hall, S.G.F. 2017. “Preventing a Colour Revolution: The Belarusian Example as an Illustration for the Kremlin?.” East European Politics 33 (2): 162–183. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2017.1301435.

- Inglehart, R., and C. Welzel. 2005. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kennedy, J.J. 2009. “Maintaining Popular Support for the Chinese Communist Party: The Influence of Education and the State-controlled Media.” Political Studies 57 (3): 517–536. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2008.00740.x.

- Kirsch, H., and C. Welzel. 2019. “Democracy Misunderstood: Authoritarian Notions of Democracy around the Globe.” Social Forces 98 (1): 59–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soy114.

- Klicperova-Baker, M., and J. Kostal. 2018. “Democratic Values in the Post-communist Region: The Incidence of Traditionalists, Sceptics, Democrats, and Radicals.” In Changing Values and Identities in the Post-Communist World, edited by N. Lebedeva, R. Dimitrova, and J. Berry, 27–51. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Klymenko, L., and S. Gherghina. 2012. “Determinants of Positive Attitudes Towards an Authoritarian Regime: The Case of Belarus.” Soviet and Post-Soviet Review 39 (2): 249–269. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/18763324-03902006.

- Krawatzek, F. 2019. “Youth in Belarus: Outlook on Life and Political Attitudes.” Centre for East European and International Studies, ZOiS Report 5/2019.

- Lechler, M., and U. Sunde. 2019. “Individual Life Horizons Influences Attitudes toward Democracy.” American Political Science Review 113 (3): 860–867. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000200.

- Levitsky, S., and L.A. Way. 2010. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lü, X. 2014. “Social Policy and Regime Legitimacy. The Effects of Education Reform in China.” American Political Science Review 108 (2): 423–437. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055414000124.

- Manaev, O., N. Manayeva, and D. Yuran. 2011. “More State than Nation: Lukashenko’s Belarus.” Journal of International Affairs 65 (1): 93–113.

- Merzlou, M. 2019. “Entfaltet der Belarussische ‘Sozial Orientierte Staat’ Eine Demokratiehemmende Wirkung? [Does the Belarusian ‘Socially Oriented State’ Unfold an Effect that Inhibits Democracy?].” Belarus-Analysen 46 (43): 2–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.31205/BA.043.01.

- Mishler, W., and R. Rose. 1996. “Trajectories of Fear and Hope: Support for Democracy in Post-Communist Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 28 (4): 553–581. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414096028004003.

- Mishler, W., and R. Rose. 2002. “Learning and Re-Learning Regime Support: The Dynamics of Post-Communist Regimes.” European Journal of Political Research 41 (1): 5–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00002.

- Neundorf, A. 2010. “Democracy in Transition. A Micro Perspective on System Change in Post-Socialist Societies.” The Journal of Politics 72 (4): 1096–1108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381610000551.

- Neundorf, A., and S. Soroka. 2018. “The Origins of Redistributive Policy Preferences: Political Socialization with and without a Welfare State.” West European Politics 41 (2): 400–427. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1388666.

- Pikulik, A. 2019. “Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine as Post-soviet Rent-Seeking Regimes.” In Stubborn Structures: Reconceptualizing Post-soviet Regimes, edited by B. Magyar, 489–506. Budapest: CEU Press.

- Przeworski, A. 1991. Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Putnam, R. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Rohrschneider, R. 1999. Learning Democracy: Democratic and Economic Values in Unified Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schwartz, S.H. 2006. “Value Orientations: Measurement, Antecedents and Consequences across Nations.” In Measuring Attitudes Cross-Nationally - Lessons from the European Social Survey, edited by R. Jowell, C. Roberts, R. Fitzgerald, and G. Eva, 169–203. London: Sage.

- Shelest, O. 2020. “Revolution in Belarus: Faktoren Und Werteorientierungen [Revolution in Belarus: Factors and Value Orientations].” Belarus-Analysen 53 (53): 2–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.31205/BA.053.01.

- Silvan, K. 2020. “From Komsomol to the Republican Youth Union: Building a Pro-presidential Mass Youth Organisation in Post-soviet Belarus.” Europe-Asia Studies 72 (8): 1305–1328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2020.1761296.

- Stiftung, Bertelsmann. 2018. BTI 2018 Country Report—Belarus. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Tucker, J., and G. Pop-Eleches. 2017. Communism’s Shadow. Historical Legacies and Contemporary Political Attitudes. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Turkina, E., and L. Surzhko-Harned. 2014. “Generational Differences in Values in Central and Eastern Europe: The Effects of Politico-Economic Transition.” Journal of Common Market Studies 52 (6): 1374–1397. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-021-00241-w.

- Way, L.A. 2005. “Authoritarian State Building and the Sources of Regime Competitiveness in the Fourth Wave: The Cases of Belarus, Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine.” World Politics 57 (2): 231–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2005.0018.

- Welzel, C. 2011. “The Asian Values Thesis Revisited: Evidence from the World Values Survey.” Japanese Journal of Political Science 12 (1): 1–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109910000277.

- Wilson, A. 2016. “Belarus: From a Social Contract to a Security Contract?” Journal of Belarusian Studies 8 (1): 78–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.30965/20526512-00801005.

- Yarashevich, V. 2014. “Political Economy of Modern Belarus: Going against Mainstream?” Europe-Asia Studies 66 (10): 1703–1734. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2014.967571.