ABSTRACT

This paper presents the results of the first-ever representative survey on the demographic and attitudinal legacies of the Armenian genocide. The data, collected in 2018, maps the varied geographical origins of the citizens of contemporary Armenia and traces their links to the genocide. Around half of contemporary Armenians descend from refugees of the genocide, while about a third had family members killed. The data also inform debates on how violence transforms societies. Respondents who lost family members during the genocide show elevated levels of ethnocentrism, and lower levels of prosocial behaviour. However, rather than victimization being associated with militarism and hawkishness, the same individuals tend to be less supportive of military solutions. Even though the genocide took place more than a century ago, its demographic and attitudinal legacies remain clearly visible in contemporary Armenia.

Introduction

Few societies have suffered from violence on a scale comparable to the Armenian experience. During the Armenian genocide of 1915–1923, an estimated 1.5 million Armenians were killed, about half of the ethnic population. The trauma of the genocide haunts Armenian society to this day. However, despite a rich historical and biographical literature on the causes, course, and consequences of the genocide, there is a dearth of quantitative research on the topic. This is even more true for scholarship that looks at the genocide and its legacy from a social science perspective – which is surprising because the Armenian case offers insights into many issues of interest to the discipline. This paper partially fills this gap by reporting the results of an original survey on the demographic, attitudinal, and behavioral legacies of the genocide. It was conducted in 2018 among a representative sample of Armenians and included both standard survey items and behavioral measures.

The first part of the paper maps the geographical origins of the cititzens of contemporary Armenia, and reports figures on the – previously unknown – share of the population descending from genocide refugees and on the share of the population who lost family members during the genocide. The second part analyzes attitudinal and behavioral correlates of historical victimization along several dimensions of interest to social scientists. These include attitudes toward various international actors, ethnocentrism, militarism, and prosocial behavior, expressed in terms of both attitudes and monetary donations to charitable organizations.

The data show that around half of contemporary Armenians trace their ancestry back to refugees from the genocide, and at least one third lost relatives in the genocide. The data also reveal lasting differences in political attitudes. Family victimization during the genocide is associated with a distinct set of political attitudes and behaviors. Individuals who lost relatives in the genocide are more ethnocentric and show lower levels of prosocial behavior. At the same time – and challenging predictions that victimization is likely to be associated with higher levels of militarism and hawkishness – the results show that the historically victimized are less supportive of military solutions.

This paper provides the first-ever quantitative assessment of some of the legacies of the genocide in contemporary Armenian society and contributes valuable data to the debate on the long-term consequences of victimization from one of the most extreme cases of mass violence in the 20th century. I proceed as follows. The first section provides a brief historical overview of the Armenian genocide. This is followed by a discussion of the empirical literature on the topic from which I derive a set of questions to be tested against the data. The remaining sections introduce the survey, present results, and conclude. Taken together, the findings speak to the lasting influence of the genocide in Armenian society, and its remarkably persistent legacy in the realm of political attitudes and behavior.

Background: the Armenian genocide and its aftermath

The Armenian genocide refers to the chain of violent expulsions, massacres, and forced starvations that the Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire suffered at the hands of Turkish and Kurdish security forces and militias between 1915 and the early 1920s (Kévorkian Citation2011). Often referred to as the first genocide of the modern era, the violence all but ended the history of Armenians in this area of the world, directly leading to the death of 1.5 million Armenians, and forcing most of the remaining population to flee to current-day Armenia (then in Tsarist Russia) or abroad (Hovannisian Citation2005). The violence of 1915 had a precedent in the Hamidian and Cilician massacres of the 1890s and 1909, during which around 200,000 individuals were murdered, and which, in popular understanding, are often counted as part of the genocide (Kévorkian Citation2011). The most severe episode of the genocide took place in 1915, in the midst of World War I and while the Ottoman Empire was under attack by France and Britain in the west and Imperial Russia in the east. This situation provided the context and part of the rationale for the violence. Armenians and other Christian minorities were considered disloyal subjects, and the fact that some Armenian men had joined the attacking Russians (and many more joined later, while the genocide was underway) was taken as proof of this claim. This notwithstanding, historians agree that the massacres, deportations, and expulsions followed a pre-mediated plan seeking and largely achieving the complete destruction of all Armenian communities in Anatolia and Eastern Anatolia, the territory of modern-day Turkey (Bloxham Citation2005; Kévorkian Citation2011; Suny Citation2015).

The signal for the genocide was the detention and eventual murder of Armenian intellectual elites in late April 1915, followed by the deportation of other notables and businessmen shortly after. The detention order was accompanied by instructions to “disarm” all Armenians. This provided the initial pretext for implementing a strategy to “exterminate all Armenian males of twelve years of age and over,” as a Turkish official bluntly told an eyewitness (Kévorkian Citation2011, 233). Over the next few months, Armenian populations throughout the Ottoman Empire were rounded up by Turkish or Kurdish military units and militias, and either dealt with on the spot or sent on death marches. During the marches, males were separated and killed, while women and children were either murdered or given or sold to local families. In some cases, villages and towns put up armed resistance, but most were eventually overwhelmed (Suny Citation2015). The main phase of the genocide was followed by a back-and-forth on the battlefield between Ottoman (later Turkish) forces, Russian Imperial (later Soviet) forces, and Armenian self-defense groups (later the nascent Armenian army), which ended in another disaster for the Armenian side. Helped by the retreat of Soviet forces and Soviet appeasement, Turkish forces conquered much of Russian Armenia, again committing large-scale massacres against the remaining civilian population (Suny Citation1993). At the end, Armenians were left with a state in the borders of current-day Armenia. However, independence was short lived (1918–1921), as the state was soon forcefully integrated into the Soviet Union and remained so until 1990. Like many former Soviet Union countries, the newly independent Armenia plunged into a deep economic crisis, aggravated by a drawn-out war with Azerbaijan over Nagorny Karabakh. While the past two decades have seen the consolidation of the Armenian state and a flourishing of grassroots democracy that culminated in the 2018 “velvet revolution,” renewed war with Azerbaijan in 2020, which resulted in the loss of control over Karabakh, poses a serious challenge to the progress made.

Theoretical expectations

Having briefly introduced the context, I now turn to the historical and social science literature to develop the expectations regarding attitudinal legacies of the genocide that will consequently be tested against the data. It is well known that violence can transform societies (Wood Citation2008). I focus on three broad categories that have been of particular interest to scholars of the region and the historical legacy of violence: attitudes toward the most important geopolitical actors in the region, the United States and Russia, and toward Armenia’s (former) enemies Turkey and Azerbaijan; exclusionary attitudes and ethnocentrism; and support for militarism versus reconciliation.

Attitudes toward other countries

Scholars working in the Caucasus region have demonstrated how conflict and fragile statehood can impact on attitudes toward international actors and geopolitical preferences (O’Loughlin, Kolossov, and Toal Citation2011, Citation2014; Toal and O’Loughlin Citation2013). Given the prominent and complex role of Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union in the history of the genocide – as an ally, betrayer, aggressor, and savior – it is particularly interesting to see if ancestors of genocide victims continue to differ in their appreciation of Russia today, or if they tend to side with Russia’s geopolitical rival in the region, the United States. Victimization is typically associated with a worsening of attitudes towards the perpetrator (Mironova and Whitt Citation2016; Hager, Krakowski, and Schaub Citation2019), and scholars have shown that such negative attitudes can be passed on between generations (Balcells Citation2012; Lupu and Peisakhin Citation2017; Hadzic, Carlson, and Tavits Citation2020). We would therefore expect harsher attitudes toward political powers associated with the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide, i.e. Turkey and – because of its close ethnic and political links to Turkey and its history of conflict with Armenia – Azerbaijan.

Exclusionary attitudes and ethnocentrism

Apart from impacting attitudes toward specific actors, the experience of violence may also lead to a general rejection of outgroups. Veteran observers of Armenian culture have linked the experience of violence to the development of ethnocentric attitudes and distrust of outsiders. For example, Hovannisian (Citation2004, 438) writes that “Armenians tend to view excessive social and cultural relations with non-Armenians as being inimical to their survival as a close-knit community,” arguing that these attitudes have been deepened by centuries of persecution. This argument mirrors scholarship in political science that sees experiences of violence as one of the main drivers of ethnocentric attitudes (LeVine and Campbell Citation1972; Kam and Kinder Citation2007). Experiences of violence, one prominent line of argument goes, induce stress and perceptions of threat, which then translate into exclusionary attitudes (Canetti-Nisim et al. Citation2009; Beber, Roessler, and Scacco Citation2014). Given the finding that trauma and stress can be passed on between generations (Felsen Citation1998), we can assume that the genocide further deepened this tendency. We would thus expect descendants of survivors to show elevated levels of ethnocentrism, in keeping with what other scholars researching post-conflict contexts have found (Mironova and Whitt Citation2016).

Militarism and attitudes toward reconciliation

Scholars have argued that experiences of violence can cause individuals to place more importance on security issues (Merolla and Zechmeister Citation2009) and may induce hawkishness and a preference for military solutions for inter-group conflict (Gadarian Citation2010; Grossman, Manekin, and Miodownik Citation2015). Similarly, empirical work on post-conflict societies in the Caucasus shows that direct experiences of violence lower willingness to forgive and prospects for reconciliation (Bakke, O’Loughlin, and Ward Citation2009). Others, however, report the opposite effect: victims of violence become “weary” and support negotiated solutions more strongly (Fabbe, Hazlett, and Sınmazdemir Citation2019; Hazlett Citation2020). The state of the literature therefore does not allow us to formulate clear-cut expectations regarding the potential effects of victimization. What is more, the cases cited differ from the one presented here in that they study contemporaneous conflict settings. It will therefore be particularly interesting to see how these tendencies play out in a case of the historical victimization of individuals’ ancestors.

Methodology

This study draws on original data collected in Armenia in the autumn and winter of 2018. As mentioned, no large-scale quantitative work had previously been undertaken on the legacies of the Armenian genocide in contemporary Armenia. Besides acquiring specific pieces of information for related works (Hakimov and Schaub Citation2021; Schaub and Hakimov Citation2021), the aim of the data collection was to recruit a representative sample of the Armenian population in order to obtain a broad and general picture of the demographic and attitudinal traces that the genocide has left in the population. To this end, the survey instrument included sections on general demographics, family origin and family victimization during the genocide, and measures of political attitudes and behavior, the detailed results of which are presented below.

The survey was implemented by a reputable local research institute with ample experience in conducting data collection in the region. While the survey and sample design were within the purview of the author, the research institute was responsible for participant recruitment and translation of the English survey text into Armenian. The institute’s staff members also provided comments and advice. Fieldwork was carried out in November and December 2018 in all 11 Armenian primary administrative divisions (marzer). Recruitment was based on a stratified random sample of electoral precincts coupled with random walks within precincts and simple random selection at the household level. The starting population was the voting-age population as per voter register, with about 2.5 million entries. The 1,959 electoral precincts used during the 2017 general elections served as the primary sampling units (PSUs). Electoral precincts rather than census tracts were used because no geographic information is available on the latter. In contrast, precinct data are accompanied by the address of the election booth, allowing us to locate the PSUs in space. To ensure a good geographic spread, nine strata were formed: one for the capital, and one each for rural and urban zones in four geographical areas (NE, NW, SE, SW) of the country. Within each stratum, I determined the number of PSUs to be sampled in accordance with the relative number of voters within them. I then randomly selected PSUs with the selection probability again set to the relative number of voters. Within each PSU selected, 12 individuals were recruited. A fixed number of people were recruited for practical reasons – to justify travel to often remote small towns or villages. The resulting imbalances – single observations can be representative for a somewhat varying number of individuals – are corrected by sampling weights that are used throughout for descriptive statistics. One PSU – a Yezidi community – had to be replaced because the community head refused to allow enumerators to work in his community. In all other cases, local authorities permitted data collection to proceed unperturbed.

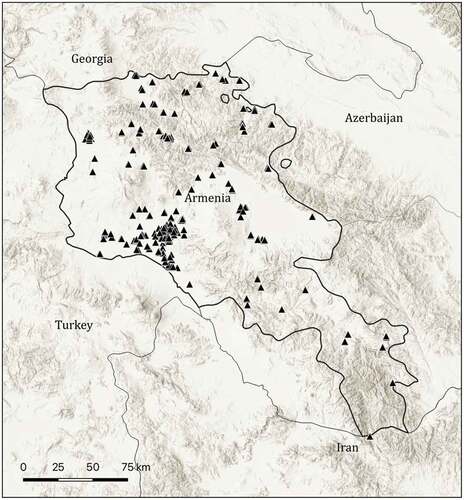

Households within PSUs were recruited by means of a random-walk protocol. Starting with a randomly chosen number of steps and direction away from the polling booths, enumerators recruited respondents in every fourth dwelling. Within-household selection was conducted by entering the identifying information of all household members aged 18 and above into the CAPI devices used for data collection, and then have the device randomly pick one household member. In the case of multi-storey buildings, this was preceded by random selection of a floor. If a household or selected household member was absent, three contact attempts were made to conduct the interview. After a failed third attempt, the house to the left of the selected household was chosen. The same procedure was followed if a household refused. In total, we made 4,325 contact attempts. Of these, 15% refused, and 24% could not be reached for practical reasons, yielding a response rate of 61%, and a final sample of n = 2,637.Footnote1 Interviews lasted an average of 21 minutes, and respondents received variable monetary compensation of between 100 and 2,000 Armenian Dram (AMD), with exact amounts depending on the performance in an incentivized quiz and on whether individuals chose to donate part of their compensation to an association (more on this below). The median compensation paid was 900 AMD, or about 2 USD. shows the approximate interview locations within Armenia.

Measurement and analysis

Population prevalence of genocide survivors

I begin the analysis by describing the origins of the contemporary Armenian population and the prevalence of descending from refugees of the genocide or having lost relatives in the genocide. This exercise provides the first-ever estimate of these quantities. This is important not least because of the difficulty of deriving such an estimate from historical figures. For example, a 1922 U.S. State Department report claimed that there were 3,004,000 Armenians in the world, of which 817,873 were refugees from Turkey, 1,200,000 were present on the territories of modern Armenia (Republic of Erivan), and the others were found in the Middle East, Europe, the Americas, and other regions of the world (US State Department Citation1961). Under the (likely unrealistic) assumption that the share of refugees was proportional, we can estimate that about 27% of the Armenian population in modern-day Armenia at the time were refugees (US State Department Citation1961). Other figures from Soviet sources are significantly higher and put this share at about half of the population (Suny Citation1993, 137). In light of these diverging estimates, the current share of the population that descends from refugees could lie anywhere between 61% and 88% – figures that again are obtainable only when making stringent assumptions.Footnote2

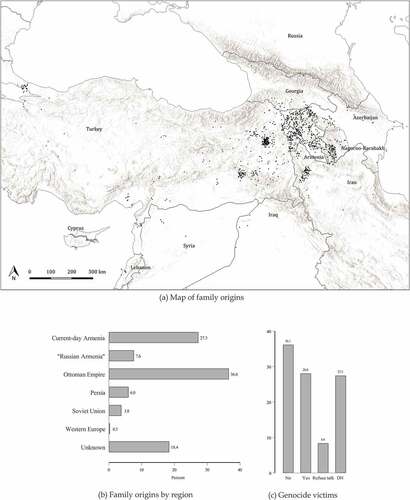

A more reliable estimate therefore requires contemporary data, which the survey presented here provides. Respondents were asked to indicate the town, village, or province where their relatives lived when the genocide started. They could indicate up to four locations, even though most respondents named only one or two.Footnote3 With the help of a research assistant, I then georeferenced respondents’ locations of origin. I classified respondents as descending from refugees of the genocide if they had at least one ancestor who hailed from the territories of current-day Turkey – the Ottoman Empire and what before the genocide was “Russian Armenia,” i.e. the areas surrounding the city of Kars. Respondents were also asked to indicate if any of their relatives were killed during the genocide, and if so, to provide an estimate of the number of relatives killed. I use this information below to explore the correlates of family victimization.

provides a map of contemporary Armenians’ family origins, and provides summary figures by region, using the most distant place of family origin where respondents named two places or more. We see that while 18% of respondents could not cite a place from which their ancestors hailed, 82% could. These figures allow for a precise population breakdown on the demographic legacies of the genocide: of the contemporary Armenian population, 27% of all respondents (and 33% of those who could name a family origin) trace all their ancestors to a location in current-day Armenia, 8% (9%) to Russian Armenia, 37% (45%) to the Ottoman Empire, 6% to Persia, 4% (4%) to the Soviet Union, and under 1% to Western Europe. This means that 45% to 54% – or about half of contemporary Armenians – hail from families who had to flee from the genocide.Footnote4 This somewhat lower estimate (as compared to those derived from historical information above) likely indicates a certain degree of endogamy among families of genocide survivors. Given these percentages, it is nevertheless not surprising that the genocide remains a central topic of political discourse in Armenia until today.

Figure 2. Known pre-genocide origins and destinies of contemporary Armenians. Note: The map in Figure 2a shows reported family origins as reported in the survey. Each location is indicated with a black marker. The map shows origins where village-, town-, or city-level information was available; the bar chart (Figure 2b) includes the full information, including cases where only province or country-level information on origins could be obtained. Percentages are based on 2,512 locations indicated by 2,156 respondents. Where respondents provided more than one location, the most distant origin is used in the calculations. 481 respondents did not indicate a family origin. (a) Map of family origins.

The question of whether individuals lost relatives during the genocide is addressed in . We see that 36% of respondents report no genocide victims in their families, 28% said that at least one relative was killed, and 28% of respondents could not answer this question. A special case is the category “refuse [to] talk.” Given the sensitive nature of asking about perished relatives, it was made explicitly clear in the survey that individuals would not need to address this question if they felt it was too painful for them to speak about these matters. As can be seen, 8% of respondents made use of this right. While it is plausible to assume that, given their emotional response, these respondents do in fact have genocide victims among the ancestors, we cannot be certain about this. I therefore estimate the share of Armenian citizens who knowingly lost relatives during the genocide to lie between 28% and 36 (28 + 8)%, about a third of the population.Footnote5

The high share of missing data and refusals constitutes a challenge for consistently estimating correlates of genocide victimization because, unless data were missing completely at random, ignoring observations for which values are missing could seriously bias results. For the analyses that follow, I therefore multiply imputed missing values. As recommended in the literature, I used chained multiple imputation to estimate missing values, using logit links for imputing binary outcomes (such as victimization) and OLS for missing continuous variables. In total, 50 imputed datasets were generated, and the statistical analysis takes into account the uncertainty introduced by the fact that the missing values are estimated rather than observed. The online appendix includes results with non-imputed values. As shown there, results are largely consistent with those presented below.

Estimating the correlates of family victimization

In order to test the hypotheses on the likely attitudinal correlates of the genocide, I use a combination of descriptive and analytic statistics. Each outcome is explored by means of bar charts showing the distribution of responses using non-missing values only. Differences between respondents with and without a family history of victimization are analyzed by means of OLS regression models drawing on the full dataset with missing values imputed. All models include the basic demographic controls gender, age, and education. In additional analyses, I include further demographic control variables such as marital status, income status, and religious observance. I also include indicators for whether a respondent has diaspora contacts in either Eastern (Russia and the former Soviet Union) or Western (the USA and Europe) countries. These latter variables are not included in the specifications because in theory, they could be influenced by the experience of my respondents’ ancestors, i.e. could constitute “channels” through which these experiences continue to shape contemporary attitudes (see the discussion in Walden and Zhukov Citation2020). Controlling for them, therefore, could bias the estimate for the effect of family victimization.

Another problem is posed by intermediate events unrelated to the event in focus, but which might have similar long-term effects.Footnote6 In the case of Armenia, one plausible intermediate event is victimization during the First Karabakh war 1988–1994, during which Armenians gained control over the Karabakh region (which they lost again during the Second Karabakh war in 2020, two years after the data for this survey were collected). According to estimates, about 6,000 Armenians lost their lives in the First Karabakh war (Yunusov cited in De Waal Citation2003, 285). It is possible that the victimization of family members during the war could have effects similar to family victimization during the genocide. To account for this possibility, I collected a variable recording whether respondents lost a relative during the war, which 19% of respondents confirmed.

I use this and the additional demographic variables to test (a) whether these variables are predicted by family victimization during the genocide, and (b) whether including these variables as controls changes my estimates for the effect of family victimization during the genocide. In line with what other scholars have noted (Henrich et al. Citation2019; Becker et al. Citation2020), descendants of genocide victims tend to be better educated and much more religiously observant.Footnote7 The analysis also shows that family victimization during the genocide is predictive of having diaspora contacts in the West. No relationship exists between family victimization during the genocide and knowing a victim of the First Karabakh war (see Figure A1 in the online appendix). Controlling for these variables does not change my estimates (see Section E of the online appendix).

Attitudinal correlates

In presenting the results, I first introduce the way the different concepts are measured, before showing overall distributions and the regression results. Attitudes toward international actors are measured by a so-called “feeling thermometer.” Respondents are asked how warm they feel toward a given country and could answer on a scale from 0 to 100, with 0 indicating “very cold,” and 100 indicating “very warm.” shows the overall distribution of answers. We can see that Russia, the traditional geopolitical patron of Armenia, is best liked, with a score of 61 on the feeling thermometer. The United States comes in a distant second with a value of only 42 points on the scale. These values stand in sharp contrast with comparable ones from neighboring Georgia, where the vast majority of respondents support integration with the West, and Russia is deeply distrusted (CISR (Center for Insights in Survey Research) Citation2018). While certainly no surprise to observers of the Caucasus, these findings once again highlight the geopolitical complexity of the region.

Figure 3. Attitudes towards geopolitical powers and neighboring countries. Notes: Bar charts showing level of warmth felt towards the indicated countries (Figure 3a); coefficient plot from a regression of the feeling thermometer measure on the indicator for having had one or more family members killed in the genocide (Figure 3b). OLS regressions. Markers are point estimates, lines 90/95% confidence intervals. Coefficients that are not statistically significant at the 10% level are shaded in grey. Missing values multiply imputed. The complete regression output can be found in Table A2 in the online appendix, and results using only non-missing values are shown in Figure A3 in the online appendix.

The degree of antipathy toward Turkey and Azerbaijan is reflected in the measurements for these two countries, which score 7 and 1 on the feeling thermometer, respectively. Indeed, 94% of respondents rated their attitudes toward Azerbaijan at 0, even before the renewed return to overt war in 2020. Do these attitudes differ significantly between individuals with genocide victims in their family vs. those without? The analysis, presented in , suggests no such differences. While values for the historically victimized are somewhat lower, these differences do not reach statistical significance.Footnote8

This does not mean that there are no meaningful attitudinal differences between those historically victimized and those without this heritage, however, as analyzed in and , which depict the results for the other outcomes discussed above. Ethnocentrism is measured with an item asking for the acceptability of non-co-ethnic immigration. Specifically, respondents were asked if they agreed with the statement “The government should allow more non-Armenian migrants to settle in Armenia.” Individuals who want to protect the purity of the Armenian ethnic group should be opposed to this measure, whereas those who – for economic, social, or humanitarian reasons – support the arrival of newcomers, should support it. Response options ranged from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” Overall, Armenians seem split on this question, with about half of respondents agreeing with the statement, and half being rather negative (parochial). Interesting differences appear when looking at individuals with a family history linked to the genocide.

Figure 4. Ethnocentrism, militarism, reconciliation, and genocide recognition. Notes: Bar charts showing the distribution of ethnocentric, militarist, and reconciliatory attitudes in the Armenian resident population, plus attitudes towards the relative priority that pushing for the international recognition of the genocide should take.

Figure 5. Family victimization and attitudes towards ethnocentrism, militarism, reconciliation, and recognition. Notes: Coefficient plots from a regression of the attitude measures on the indicator for hailing from a family with genocide victims. OLS regressions. Markers are point estimates, lines 90/95% confidence intervals. Coefficients that are not statistically significant at the 10% level are shaded in grey. Missing values multiply imputed. The complete regression output can be found in Table A3 in the online appendix, and results using only non-missing values are shown in Figure A3 in the online appendix.

For this analysis, again conducted in a regression framework, I standardize responses by deducting the overall mean, dividing by the standard deviation, and then normalizing the scale to range between 0 to 1. The regression coefficients can therefore be read as percentage differences in standard deviations of the outcomes and are comparable across different outcomes. We see that respondents with genocide victims in their families are significantly less open to the immigration of non-Armenians than those without such a family history. In other words, historical victimization appears to go along with increased parochialism, mirroring the effects of contemporary conflicts in the wider region (cf. Hager, Krakowski, and Schaub Citation2019).

Yet does this parochialism have an aggressive dimension, too? In other words, can we find elevated levels of militarism among the relatives of genocide victims? Several items in the survey, including two behavioral measures discussed below, allow me to investigate this question in some detail. A first indication comes from an item where respondents were asked how justified it would be “for Armenia to militarily attack another country to get lost territories back.”Footnote9 Responses are shown in . A majority of around 60% of Armenians tend to disagree that offensive action should be an option to regain territories, while around 40% are in favor of such an aggressive stance. Interestingly, respondents with victims in their families are less in favor of using violence to regain lost territory. Their parochialism, it seems, is not paired with aggressiveness, but is rather a sign of caution.

Do these attitudes influence how Armenians see efforts toward reconciliation and international recognition of the genocide? To answer these questions, the survey included two items, one asking for the degree to which respondents “support initiatives that seek reconciliation between Armenia and Turkey,” and another asking for the priority that the “recognition of the Armenian genocide should take in Armenia’s foreign policy agenda, as compared to, for example, the maintenance of a good partnership with the USA and the EU.” The distribution of answers is given in ). The figures show that, as of 2018 (i.e. before the 2020 war between Armenia and Azerbaijan), there were remarkably high levels of support for reconciliation, with only 15% of the population opposed to such measures, and almost 70% clearly in favor.

This pro-conciliatory stance went along with relatively low priority for international recognition of the genocide, at least when compared to other important foreign policy goals. No more than a third of the citizens of contemporary Armenia believed that recognition of the genocide should be given high or the highest priority. Remarkably, respondents with genocide victims in their family give significantly lower priority to international recognition of the genocide than those not historically victimized (). It should be highlighted that the results presented here are representative of Armenians in Armenia only. Results may look different if diaspora Armenians were included in the survey. For example, it is plausible that those whose ancestors had had to flee abroad and had lost their homeland indeterminately show more hawkish attitudes or are more keen to have the genocide recognized. I present an – albeit very indirect – test of this hypothesis in Figure A4 in the online appendix, and find some suggestive evidence in favor of the idea.Footnote10 Overall, the “weariness” argument – that victims of violence, or in this case, their descendants – are more sceptical toward the use of force, and more open toward resolution efforts, is supported by the data. Indeed, there is little to suggest that the genocide has increased hawkish and militaristic attitudes in the population. Further evidence on this point comes from the behavioral measures, to which I now turn.

Behavioral measures

In order to probe more deeply into how respondents whose families were affected by the genocide relate to political outcomes, the survey included two behavioral measures. The advantage of measuring behavior is that behavior is more robust to over-reporting and preference falsification (Silver, Anderson, and Abramson Citation1986; Jiang and Yang Citation2016); the disadvantage is that behavior is often motivated by a host of reasons, making it hard to interpret a particular action as indicative of a specific attitude. Keeping this caveat in mind, I now introduce the first behavioral measure, a donation task. As already mentioned, all respondents received monetary compensation for their participation. At the end of the interview, respondents were then asked if they were willing to donate part of the money they had earned. Half of the respondents were asked whether they would give 200 Armenian dram (0.40 USD) to a veterans association, the “Karabakh War Veterans NGO,” and the other half whether they would donate the same amount to the Hrant Dink foundation, truthfully introduced as “an NGO supporting dialogue between Armenians and Turks.”Footnote11 Both measures can be interpreted as prosocial behavior, which can be defined as “voluntary actions that are intended to help or benefit another individual or group of individuals” (Eisenberg and Mussen Citation1989).

An important literature presents results according to which victims of war act more prosocially after their victimization (for a review, see Bauer et al. Citation2016). However, contrasting evidence is accumulating that shows that victimization often goes along instead with lower, not higher, levels of prosociality (Cassar, Grosjean, and Whitt Citation2013; Hager, Krakowski, and Schaub Citation2019). What is more, it is not clear whether these effects are lasting, and are transmitted across generations. While this is clearly a possibility, as demonstrated by studies that trace elevated levels of political engagement over generations (Lupu and Peisakhin Citation2017; Rozenas and Zhukov Citation2019), there are few studies that show intergenerational effects of prosocial behavior over generations (but see Wayne and Zhukov Citation2022). The Armenian case therefore provides an important point of evidence for this debate. Besides this general point, the donation measures provide another way of probing for reconciliatory vs. militaristic stances among individuals with genocide victims in their families. The donation to the Hrant Dink foundation can be seen as active support for reconciliation efforts, whereas individuals with a militaristic mindset should be in support of veteran associations – even though purely charitable motivations may of course also explain the donation.

shows overall levels of donations, and differences between the two groups of respondents with family histories linked to the genocide, and those without. We see that no fewer than 80% of respondents donated part of their earnings when asked to do so, speaking to a high level of (in-group) prosociality present in contemporary Armenian society. An interesting pattern arises when comparing individuals with genocide victims in their families with those without. Overall, respondents who lost relatives in the genocide donate less often than those not historically victimized. This seems to apply to both types of donation even though the effects on the individual indicators fail to reach statistical significance (which is partially explained by the lower power of these analyses, which each draw on about half the sample size only). This finding challenges the idea that victimization generally increases prosociality. At least in the case of Armenia violence seems to be associated with, if anything, less prosociality, not more.

Figure 6. Behavioral measures. Notes: Bar charts showing the overall share of respondents that donated, the share that donated to the Karabakh veterans association, the share that donated to the Hrant Dink foundation, and the share of respondents with sons aged 18 or more whose sons served on the front line with Azerbaijan (Figure 6A). Coefficient plots from regressions of the propensity to donate and likelihood to serve on the indicator for having had one or more family members killed during the genocide (Figure 6B). OLS regressions. Markers are point estimates, lines 90/95% confidence intervals. Coefficients that are not statistically significant at the 10% level are shaded in grey. Missing values multiply imputed. The complete regression output can be found in Table A4 in the online appendix, and results using only non-missing values are shown in Figure A3 in the online appendix.

As a last behavioral measure, respondents were asked whether they had one or more sons above the age of 18 – a question that 47% of respondents confirmed. From 18 years on, males are required to do mandatory military service. This service is a highly contentious issue in Armenia because conscripts can be, and often are, sent to the front line with Azerbaijan where there are regular fatalities. While no one in Armenia denies that military service is necessary, the risks are also widely known. Some families therefore manage to avoid the draft for their sons altogether (by sending them to study abroad or through bribery), or to have them serve away from the front line (by lobbying military commanders or paying bribes).

Willingness to have a son serve on the front line, therefore, can be indicative of respondents’ support for the use of force and can also be interpreted as another general measure of prosociality (even though it is uncorrelated with the donation measure). We may therefore expect that those whose families were victimized during the genocide are more hesitant to send their sons to the frontline. As can be seen in , about half of respondents – 48% – with sons over the age of 18 had them serving at the frontline with Azerbaijan. The sons of the other half of respondents either served away from the frontline (39%) or did not serve at all (13%). However, unlike hypothesized, this distribution does not significantly differ between respondents with family links to the genocide as compared to those without.

Persistence

The analysis links attitudinal and behavioral patterns to events that occurred over a century ago. This raises the question as to how such legacies can persist and are transmitted. Research on these questions is ongoing, and several possible channels have been suggested, including institutional legacies and family socialization (Walden and Zhukov Citation2020). The starting assumption of this research project was that experiences are transmitted within families, and the overall results – which demonstrate clear signs of persisting effects of past family victimization – can be interpreted as suggestive evidence in support of this idea. Unfortunately, since only one person per household was interviewed, the presence or absence of intergenerational transmission could not be tested directly. Related to the issue of possible transmission channels is the question whether legacies decline over time. Empirical evidence for such decline is provided, for example, by Lupu and Peisakhin (Citation2017), who record the effects of family victimization on the political identities of descendants, but also show that these effects diminish across generations. At the same time, scholars working on long-term psychological effects of the holocaust have recorded uniformly high levels of trauma, militancy towards perpetrators, but also of prosocial attitudes across generations (Solkoff Citation1992; Canetti et al. Citation2018; Wayne and Zhukov Citation2022).

The data presented here allows for an, albeit indirect, test of the fidelity of transmission across time. For the test, I interact the measure of family victimization with the respondents’ age, and calculate the marginal effects of family victimization for different ages (). Results show that for some of the outcomes, notably ethnocentrism and donation behavior, effects are present for older respondents but are weak or absent for younger respondents, suggesting that the legacy of the genocide is slowly disappearing. For other outcomes such as militaristic attitudes and the question of recognition, no such pattern shows. Here, the effect of family victimization appears to be strongest among the middle-aged, suggesting more complex patterns of transmission.

Figure 7. Marginal effect of family victimization depending on age. Note: Effect of having had one or more family members killed in the genocide on selected outcomes (on the y-axis), by age of the respondent (on the x-axis). Marginal effect after OLS regression using non-missing values. Markers are point estimates, lines 90/95% confidence intervals. Coefficients that are not statistically significant at the 10% level are shaded in grey. Standard errors adjusted for survey design.

Conclusion

This paper presents the results of the first-ever representative survey on the demographic and attitudinal legacies of the Armenian genocide. Reliable estimates of the share of contemporary Armenians who can trace their roots to victims of the genocide have so far been lacking. The survey addresses this gap: it shows that about half of the citizens of contemporary Armenia descend from refugees of the genocide, and at least a third have victims of the genocide among their relatives. The paper then demonstrates that the genocide still influences political attitudes in contemporary Armenia.

In so doing, the research contributes evidence to several debates in the social sciences. First, scholars have argued that exposure to violence is frequently accompanied by higher levels of ethnocentrism. The data from Armenia supports this hypothesis. While there is no effect of victimization on attitudes toward Russia, the United States, or neighboring countries, individuals with genocide victims among their relatives are significantly less open toward non-Armenians, speaking to higher levels of parochialism among those whose families were victimized. Second, even though it is often asserted that experiences of violence make individuals more hawkish, the evidence from the Armenian case does not support this hypothesis. Instead, the paper provides ample evidence that historical victimization is associated with lower support for militarism, in line with the “war-weariness”’ hypothesis. Individuals from historically victimized families are no less willing to reconcile with Turkey than the rest of the population and they are clearly more opposed to using force to regain lost territories.

Third, the data also speak to debates on the legacies of violence for prosocial behavior, here measured with a donation task embedded in the survey. Having lost relatives during the genocide is associated with lower levels of donations, i.e. decreased levels of prosociality. This finding contrasts with some established research in the field, but mirrors scholarship that has found victimization to go along with a withdrawal from social interactions.

How does the legacy of the genocide continue to shape Armenian society? The data presented here point to highly ambiguous effects. On the one hand, theoretical expectations that victimization would leave the society militarized and in favor of the use of force are not borne out by the data. However, this relative pacifism, rather than a sign of conviction, appears to be a symptom of weariness and relative retreat from society. Relatives of genocide victims are less in favor of military aggression, but also less prosocial and more parochially minded. It is plausible that the return to full-out war in Karabakh in 2020, during which Armenians lost control over the region to Azerbaijan, may have reinforced or weakened some of these effects. Establishing if such interlacing legacies did indeed take hold is an important area for further research. These complexities notwithstanding, it seems clear that a century after its end, the genocide continues to cast its shadow over Armenian society.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (338 KB)Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Sona Balasanyan, Eliška Drápalová, Ella Karagulyan, Heghine Manasyan, and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback, and Rustamdjan Hakimov for cooperation during data collection. I am also indebted to the staff of CRRC Armenia for their professional implementation of the survey and their advice. Gorik Avetisyan, Lilit Babayan, and Gisela Müller provided excellent research assistance.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2022.2143116

Data availability statement

The data and code used in this study are available on Harvard's Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/IS0ADG.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In general, this response rate compares favorably with other surveys conducted in the region. This said, it is still possible that selective non-response could bias the estimates presented here. Speculating about the direction of the bias, it is plausible to assume that those who refuse are generally less prosocially inclined. Given that historical victimization is associated with lower levels of prosociality (as will be shown below), it is possible that the survey slightly underestimates the share of victimized individuals in the Armenian population.

2. Assuming initial refugee shares of 24% or 50%, perfect mixing between refugees and the settled population, and equal fertility rates, three generations later the share of individuals that have at least one refugee ancestor should be between 1 − [(1 − 0.27)3] = 0.61 (61%) and 1 − [(1 − 0.50)3] = 0.875 (87.5%), respectively.

3. 86% named one place of origin, 13% named two, and the rest three or four. Among those respondents who named an origin, 41% were able to name their ancestors’ village, town, or city of origin, another 47% could name the province, and the others reported the broader country or region.

4. The figure of 45% is obtained by adding up the absolute population shares of those who trace their ancestry to the Ottoman Empire or Russian Armenia; the figure of 54% results from adding up the population shares for those with known origins only.

5. Ignoring those who said they did not know whether relatives were killed or not, i.e. calculating shares for respondents with non-missing information only, gives an estimated population share of victimized families of between 44% (not taking into account those who refused) and 50% (counting those who refused as historically victimized).

6. If such intermediate events are correlated with the event in focus, we might erroneously attribute correlations between our event in focus and an outcome to the event in focus, while in reality the correlation is between the intermediate event and the outcome.

7. But see Lupu and Peisakhin (Citation2017), who find no evidence for increased religiosity among Crimean Tatar victims of Stalinist deportations.

8. When analyzing non-missing values only, negative and statistically significant correlations show for attitudes toward the US, Russia, and Azerbaijan (see Figure A3 in the online appendix).

9. The exact territories to which this question referred were not specified. However, since at the time of the survey, Armenians controlled most of their historical settlement areas in the east (i.e. Karabakh), it is plausible that people mainly thought of the historical Armenian settlement areas in present-day Turkey when answering this question.

10. For the test, I interact the question of whether individuals lost relatives in the genocide with a variable for whether (and how many) relatives they had living abroad. The idea is that the more contact individuals have with Armenians living in exile, the more they tend to be influenced by them. This influence might then be reflected in their own attitudes. The results provide some support for the hypothesis. The more relatives individuals have abroad, the more ethnocentric they tend to be. Conversely, the negative effect of family victimization on prioritizing the recognition of the genocide (reported in the main text) is only to be found among those who have no relatives or only one abroad. Among those with more relatives abroad, the effect is zero. No distinct patterns show for the other two indicators.

11. The amount of 200 Armenian dram constituted 22% of the average compensation the respondents received. All donations were transferred to the respective institutions upon conclusion of the fieldwork.

References

- Bakke, K.M., J. O’Loughlin, and M.D. Ward. 2009. “Reconciliation in Conflict-Affected Societies: Multilevel Modeling of Individual and Contextual Factors in the North Caucasus of Russia.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 99 (5): 1012–1021. doi:10.1080/00045600903260622.

- Balcells, L. 2012. “The Consequences of Victimization on Political Identities: Evidence from Spain.” Politics & Society 40 (3): 311–347. doi:10.1177/0032329211424721.

- Bauer, M., C. Blattman, J. Chytilova, J. Henrich, E. Miguel, and T. Mitts. 2016. “Can War Foster Cooperation?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30 (3): 249–274. doi:10.1257/jep.30.3.249.

- Beber, B., P. Roessler, and A. Scacco. 2014. “Intergroup Violence and Political Attitudes: Evidence from a Dividing Sudan.” The Journal of Politics 76 (3): 649–665. doi:10.1017/S0022381614000103.

- Becker, S.O., J. Grosfeld, P. Grosjean, N. Voigtländer, and E. Zhuravskaya. 2020. “Forced Migration and Human Capital: Evidence from Post-WWII Population Transfers.” American Economic Review 110 (5): 1430–1463. doi:10.1257/aer.20181518.

- Bloxham, D. 2005. The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Canetti, D., G. Hirschberger, C. Rapaport, J. Elad-Strenger, T. Ein-Dor, S. Rosenzveig, T. Pyszczynski, and W.E. Hobfoll. 2018. “Collective Trauma from the Lab to the Real World: The Effects of the Holocaust on Contemporary Israeli Political Cognitions.” Political Psychology 39 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1111/pops.12384.

- Canetti-Nisim, D., E. Halperin, K. Sharvit, and S.E. Hobfoll. 2009. “A New Stress-Based Model of Political Extremism: Personal Exposure to Terrorism, Psychological Distress, and Exclusionist Political Attitudes.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 53 (3): 363–389. doi:10.1177/0022002709333296.

- Cassar, A., P. Grosjean, and S. Whitt. 2013. “Legacies of Violence: Trust and Market Development.” Journal of Economic Growth 18 (3): 285–318. doi:10.1007/s10887-013-9091-3.

- CISR (Center for Insights in Survey Research). 2018. “Public Opinion Survey: Residents of Georgia.” Technical report, International Republican Institute. Accessed 23 October 2022. https://www.iri.org/wp-content/uploads/legacy/iri.org/2018-5-29_georgia_poll_presentation.pdf

- De Waal, T. 2003. Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press.

- Eisenberg, N., and P.H. Mussen. 1989. The Roots of Prosocial Behavior in Children. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fabbe, K., C. Hazlett, and T. Sınmazdemir. 2019. ““A Persuasive Peace: Syrian Refugees’ Attitudes Towards Compromise and Civil War Termination.” Journal of Peace Research 56 (1): 103–117. doi:10.1177/0022343318814114.

- Felsen, I. 1998. “Transgenerational Transmission of Effects of the Holocaust.” In International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma, edited by Y. Danieli, 43–68. Boston: Springer US, Plenum Series on Stress and Coping.

- Gadarian, S.K. 2010. “The Politics of Threat: How Terrorism News Shapes Foreign Policy Attitudes.” The Journal of Politics 72 (2): 469–483. doi:10.1017/S0022381609990910.

- Grossman, G., D. Manekin, and D. Miodownik. 2015. “The Political Legacies of Combat: Attitudes toward War and Peace among Israeli Ex-Combatants.” International Organization 69 (4): 981–1009. doi:10.1017/S002081831500020X.

- Hadzic, D., D. Carlson, and M. Tavits. 2020. “How Exposure to Violence Affects Ethnic Voting.” British Journal of Political Science 50 (1): 345–362. doi:10.1017/S0007123417000448.

- Hager, A., K. Krakowski, and M. Schaub. 2019. “Ethnic Riots and Prosocial Behavior: Evidence from Kyrgyzstan.” American Political Science Review 113 (4): 1029–1044. doi:10.1017/S000305541900042X.

- Hakimov, Rustamdjan, and Max Schaub. 2021. “Diaspora Influence and Revolution.” Unpublished manuscript, May.

- Hazlett, C. 2020. “Angry or Weary? How Violence Impacts Attitudes toward Peace among Darfurian Refugees.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64 (5): 844–870. doi:10.1177/0022002719879217.

- Henrich, J., M. Bauer, A. Cassar, J. Chytilová, and B.G. Purzycki. 2019. “War Increases Religiosity.” Nature Human Behaviour 3 (2): 129–135. doi:10.1038/s41562-018-0512-3.

- Hovannisian, R.G. 2004. The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times Vol. II. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hovannisian, R.G. 2005. “Genocide and Independence, 1914–21.” In The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity, edited by E. Herzig and M. Kurkchiyan, 89–112. Oxford: Routledge.

- Jiang, J., and D.L. Yang. 2016. “Lying or Believing? Measuring Preference Falsification from a Political Purge in China.” Comparative Political Studies 49 (5): 600–634. doi:10.1177/0010414015626450.

- Kam, C.D., and D.R. Kinder. 2007. “Terror and Ethnocentrism: Foundations of American Support for the War on Terrorism.” The Journal of Politics 69 (2): 320–338. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00534.x.

- Kévorkian, R.H. 2011. The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London: Tauris.

- LeVine, R.A., and D.T. Campbell. 1972. Ethnocentrism: Theories of Conflict, Ethnic Attitudes, and Group Behavior. New York: Wiley.

- Lupu, N., and L. Peisakhin. 2017. “The Legacy of Political Violence across Generations.” American Journal of Political Science 61 (4): 836–851. doi:10.1111/ajps.12327.

- Merolla, J.L., and E.J. Zechmeister. 2009. Democracy at Risk: How Terrorist Threats Affect the Public. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mironova, V., and W. Whitt. 2016. “Social Norms after Conflict Exposure and Victimization by Violence: Experimental Evidence from Kosovo.” British Journal of Political Science 48 (3): 749–765. doi:10.1017/S0007123416000028.

- O’Loughlin, J., V. Kolossov, and G. Toal. 2011. “Inside Abkhazia: Survey of Attitudes in a de Facto State.” Post-Soviet Affairs 27 (1): 1–36. doi:10.2747/1060-586X.27.1.1.

- O’Loughlin, J., V. Kolossov, and G. Toal. 2014. “Inside the Post-Soviet de Facto States: A Comparison of Attitudes in Abkhazia, Nagorny Karabakh, South Ossetia, and Transnistria.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 55 (5): 423–456. doi:10.1080/15387216.2015.1012644.

- Rozenas, A., and Y.M. Zhukov. 2019. “Mass Repression and Political Loyalty: Evidence from Stalin’s ‘Terror by Hunger.’.” American Political Science Review 113 (2): 569–583. doi:10.1017/S0003055419000066.

- Schaub, Max, and Rustamdjan Hakimov. 2021. “Genocide and Revolution: The Legacy of Mass Violence and Political Activism in Armenia.” Unpublished manuscript, March.

- Silver, B.D., B.A. Anderson, and P.R. Abramson. 1986. “Who Overreports Voting?” American Political Science Review 80 (2): 613–624. doi:10.2307/1958277.

- Solkoff, N. 1992. “Children of Survivors of the Nazi Holocaust: A Critical Review of the Literature.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 62 (3): 342–358. doi:10.1037/h0079348.

- Suny, R.G. 1993. Looking toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Suny, R.G. 2015. “They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else”: A History of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Toal, G., and J. O’Loughlin. 2013. “Inside South Ossetia: A Survey of Attitudes in A de Facto State.” Post-Soviet Affairs 29 (2): 136–172. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2013.780417.

- US State Department. 1961. “Approximate Number Armenians in the World, November 1922.” Washington, DC: US State Department, Technical Report.

- Walden, J., and Y.M. Zhukov. 2020. “Historical Legacies of Political Violence.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Accessed 23 October 2022. https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefour/978090228637.001.0001/acrefour-978090228637-e-1788.

- Wayne, C., and Y.M. Zhukov. 2022. “Never Again: The Holocaust and Political Legacies of Genocide.” World Politics 74 (3): 367–404. doi:10.1017/S0043887122000053.

- Wood, E.J. 2008. “The Social Processes of Civil War: The Wartime Transformation of Social Networks.” Annual Review of Political Science 11: 539–561. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.8.082103.104832.